.gif)

HMS Royal Oak (1914)

Encyclopedia

HMS Royal Oak (pennant number

08) was a Revenge-class

battleship

of the British Royal Navy

. Launched in 1914 and completed in 1916, Royal Oak first saw action at the Battle of Jutland

. In peacetime, she served in the Atlantic, Home and Mediterranean fleets, more than once coming under accidental attack. The ship drew worldwide attention in 1928 when her senior officers were controversially court-martial

led. Attempts to modernise Royal Oak throughout her 25-year career could not fix her fundamental lack of speed, and by the start of the Second World War, she was no longer suited to front-line duty.

On 14 October 1939, Royal Oak was anchored at Scapa Flow

in Orkney, Scotland

when she was torpedoed by the German submarine

U-47. Of Royal Oak' s complement of 1,234 men and boys, 833 were killed that night or died later of their wounds. The loss of the old ship — the first of the five Royal Navy battleships and battle cruisers sunk in the Second World War — little affected the numerical superiority enjoyed by the British navy and its Allies

, but the effect on wartime morale was considerable. The raid made an immediate celebrity and war hero out of the U-boat commander, Günther Prien

, who became the first Kriegsmarine

submarine officer to be awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

. To the British, the raid demonstrated that the Germans were capable of bringing the naval war to their home waters, and the shock resulted in rapidly arranged changes to dockland security.

Now lying almost upside-down in 100 feet (30 m) of water with her hull 16 feet (5 m) beneath the surface, Royal Oak is a designated war grave

. In an annual ceremony to mark the loss of the ship, Royal Navy divers place a White Ensign

underwater at her stern. Unauthorised divers are prohibited from approaching the wreck at any time.

to be a cheaper—but smaller and slower—coal-fired version of the earlier oil-fired Queen Elizabeth-class

super-dreadnoughts. The design, seemingly a technological step backwards, was partly a response to fears that a dependence upon fuel oil—all of which had to be imported—could leave the class crippled in the event of a successful maritime blockade. High-quality coal, on the other hand, was in plentiful supply, and homeland supplies could be guaranteed. Furthermore, in contrast to the "Fast Squadron" Queen Elizabeths, the Revenge class were intended to be the heaviest-gunned vessels in the line of battle proper. Royal Oak and her sisters were the first major vessels for the Royal Navy whose design was supervised by the newly appointed Director of Naval Construction

, Sir Eustace Tennyson-D'Eyncourt.

Royal Oak was laid down at Devonport Dockyard

Royal Oak was laid down at Devonport Dockyard

on 15 January 1914, the fourth of her class. Concerned over the performance limitations of coal, and having secured new oil supplies with a contract agreed with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company

, First Sea Lord

Jackie Fisher rescinded the decision on coal in October 1914. Still under construction, Royal Oak was redesigned to employ eighteen oil-fired Yarrow

boilers supplying four Parsons

reaction steam turbines

, each directly driving a single 9.5 feet (2.9 m) three-bladed screw

. The battleship was launched on 17 November of that year, and after fitting-out, was commissioned on 1 May 1916 at a final cost of £2,468,269. Named after the oak tree

in which Charles II

hid following his defeat at the 1651 Battle of Worcester

, she was the eighth Royal Navy vessel to bear the name Royal Oak

, replacing a pre-dreadnought

scrapped in 1914. While building she was temporarily assigned the pennant number

67.

Royal Oak was refitted between 1922 and 1924, when her anti-aircraft defences were upgraded by replacing the original QF 3 inches (76.2 mm) 20 cwt AA guns

with QF 4 inches (101.6 mm)

high-angle mounts. Fire-control system

s and rangefinder

s for main and secondary batteries were modernised, and underwater protection improved by 'bulging

' the ship. The watertight chambers, attached to either side of the hull, were designed to reduce the effect of torpedo blasts and improve stability, but at the same time widened the ship's beam by over 13 feet (4 m).

A brief refit in the spring of 1927 saw the addition of two more 4 inches (101.6 mm) high-angle AA guns and the removal of the two 6 inches (152.4 mm) guns from the shelter deck. The ship received a final refit between 1934 and 1936, when her deck armour was increased to 5 inches (12.7 cm) over the magazines

and to 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) over the engine rooms. In addition to a general modernisation of the ship's systems, a catapult for a spotter float plane was installed above X–turret, and anti-aircraft defences were strengthened by doubling up each of the 4 inches (101.6 mm) AA guns and adding a pair of octuple Mark VIII pompom guns to sponson

s abreast the funnel. The mainmast was reconstructed as a tripod to support the weight of a radio-direction finding

office and a second High-angle Control Station

. The extra armour and equipment made Royal Oak one of the best equipped of the Revenge class, but the additional weight caused her to sit lower in the water, lowering her top speed by several knots.

The First World War had been under way for almost two years when Royal Oak was commissioned. She was assigned to the Third Division of the Fourth Battle Squadron

The First World War had been under way for almost two years when Royal Oak was commissioned. She was assigned to the Third Division of the Fourth Battle Squadron

of the British Grand Fleet

, and within the month was ordered, along with most of the fleet, to engage the German High Seas Fleet

in the Battle of Jutland

. Under the command of Captain Crawford Maclachlan, Royal Oak left Scapa Flow on the evening of 30 May in the company of the battleships Superb

, Canada and Admiral Jellicoe's

flagship Iron Duke

. The next day's indecisive battle saw Royal Oak fire a total of thirty-eight 15 inches (381 mm) and eighty-four 6 inches (152.4 mm) shells, claiming three hits on the battlecruiser Derfflinger

, putting one of its turrets out of action, and a hit on the cruiser Wiesbaden. She avoided damage herself, despite being straddled by shellfire on one occasion.

Following the battle, Royal Oak was reassigned to the First Battle Squadron. On 5 November 1918—the final week of the First World War—she was anchored off Burntisland

in the Firth of Forth

accompanied by the aircraft carrier

Campania

(formerly a Blue Riband

winner for the Cunard Line prior to its conversion for wartime use) and battlecruiser

Glorious

. A sudden Force 10

squall caused Campania to drag her anchor, collide with Royal Oak and then with the 22,000-ton Glorious. Both Royal Oak and Glorious suffered only minor damage; Campania, however, was holed by her initial collision with Royal Oak. The ship's engine rooms flooded, and she settled by the stern and sank five hours later, though without loss of life.

At the end of the First World War Royal Oak escorted several vessels of the surrendering German High Seas Fleet from the Firth of Forth

to their internment in Scapa Flow

, and was present at a ceremony in Pentland Firth

to greet other ships as they followed.

The peacetime reorganisation of the Royal Navy assigned Royal Oak to the Second Battleship Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet. Modernised by the 1922–24 refit, she was transferred in 1926 to the Mediterranean Fleet, based in Grand Harbour

The peacetime reorganisation of the Royal Navy assigned Royal Oak to the Second Battleship Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet. Modernised by the 1922–24 refit, she was transferred in 1926 to the Mediterranean Fleet, based in Grand Harbour

, Malta

. In early 1928, this duty saw the notorious incident the contemporary press dubbed the "Royal Oak Mutiny". What began as a simple dispute between Rear-Admiral Bernard Collard and Royal Oak' s two senior officers Captain Kenneth Dewar

and Commander Henry Daniel over the band at the ship's wardroom

dance, descended into a bitter personal feud that spanned several months. Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew; in return, Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman". When Dewar and Daniel wrote letters of complaint to Collard's superior, Vice-Admiral John Kelly, he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their flag admiral had irretrievably broken down, Keyes removed all three from their posts and sent them back to England, postponing a major naval exercise. The press picked up on the story worldwide, describing the affair—with some hyperbole—as a "mutiny". Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the King

, who summoned First Lord of the Admiralty William Bridgeman

for an explanation.

For their letters of complaint, Dewar and Daniel were controversially charged with writing subversive documents. In a pair of

highly publicised courts-martial

, both were found guilty and severely reprimanded, leading Daniel to resign from the Navy. Collard himself was criticised for the excesses of his conduct by the press and in Parliament, and on being denounced by Bridgeman as "unfitted to hold further high command", was forcibly retired from service.

Of the three, only Dewar escaped with his career, albeit a damaged one: he remained in the Royal Navy in a series of more minor commands and was promoted to Rear-Admiral the following year, one day before his retirement. Daniel attempted a career in journalism, but when this and other ventures were unsuccessful, he disappeared into obscurity amid poor health in South Africa. Collard retreated to private life and never spoke publicly of the incident again.

The scandal proved an embarrassment to the reputation of the Royal Navy, then still the world's largest, and it was satirised at home and abroad through editorials, cartoons, and even a comic jazz oratorio composed by Erwin Schulhoff

. One consequence of the damaging affair was an undertaking from the Admiralty to review the means by which naval officers might bring complaints against the conduct of their superiors.

, Royal Oak was tasked with conducting 'non-intervention patrols' around the Iberian Peninsula

. On such a patrol and steaming some 30 nmi (55.6 km; 34.5 mi) east of Gibraltar

on 2 February 1937, she came under aerial attack by three aircraft of the Republican

forces. They dropped three bombs (two of which exploded) within 3 cables

(555 m) of the starboard bow, though causing no damage. The British chargé d'affaires

protested the incident to the Republican Government, which admitted its error and apologised for the attack. Later that same month, while stationed offshore of Valencia on 23 February 1937 during an aerial bombardment by the Nationalists, she was accidentally struck by an anti-aircraft shell fired from a Republican position. Five men were injured, including Royal Oak' s captain, T.B. Drew. On this occasion however the British elected not to protest to the Republicans, deeming the incident "an Act of God

". In May 1937, she and escorted SS Habana, a liner carrying Basque

child refugees, to England. In July, as the war in northern Spain flared up, Royal Oak, along with the battleship

rescued the steamer Gordonia when Spanish nationalist warships attempted to capture her off Santander

. She was however unable on 14 July to prevent the seizure of the British freighter Molton by the Spanish nationalist cruiser Almirante Cervera

while trying to enter Santander. The merchantmen had been engaged in the evacuation of refugees.

This same period saw Royal Oak star alongside fourteen other Royal Navy vessels in the 1937 British film melodrama

Our Fighting Navy

, the plot of which centres around a coup in the fictional South American republic of Bianco. Royal Oak portrays a rebel battleship El Mirante, whose commander forces a British captain (played by Robert Douglas

) into choosing between his lover and his duty. The film was poorly received by critics, but gained some redemption through its dramatic scenes of naval action.

In 1938, Royal Oak returned to the Home Fleet and was made flagship

In 1938, Royal Oak returned to the Home Fleet and was made flagship

of the Second Battleship Squadron based in Portsmouth

. On 24 November 1938, she returned the body of the British-born Queen Maud of Norway

, who had died in London, to a state funeral in Oslo, accompanied by her husband King Haakon VII

. Paying off in December 1938, Royal Oak was recommissioned the following June, and in the late summer of 1939 embarked on a short training cruise in the English Channel

in preparation for another 30-month tour of the Mediterranean,. for which her crew were pre-issued tropical uniforms. As hostilities loomed, the battleship was instead dispatched north to Scapa Flow

, and was at anchor there when war was declared on 3 September.

In October 1939, Royal Oak joined the search for the German battleship

Gneisenau

, which had been ordered into the North Sea as a diversion for the commerce-raiding

pocket battleships Deutschland

and Graf Spee. The search was ultimately fruitless, particularly for Royal Oak, whose top speed, by then less than 20 kn (39.2 km/h; 24.4 mph), was inadequate to keep up with the rest of the fleet. On 12 October, Royal Oak returned to the defences of Scapa Flow in poor shape, battered by North Atlantic storms: many of her Carley float

s had been smashed and several of the smaller-calibre guns rendered inoperable. The mission had underlined the obsolescence of the 25-year-old warship. Concerned that a recent overflight by German reconnaissance aircraft heralded an imminent air attack upon Scapa Flow, Admiral of the Home Fleet Charles Forbes ordered most of the fleet to disperse to safer ports. Royal Oak however remained behind, her anti-aircraft guns still deemed a useful addition to Scapa's otherwise scarce air defences.

s. The threat from U-boats had however long been realised, and a series of countermeasures were installed during the early years of the First World War. Blockship

s were sunk at critical points, and floating booms deployed to block the three widest channels. Operated by tugboats to allow the passage of friendly shipping, it was considered possible—but highly unlikely—that a daring U-boat commander could attempt to race through undetected before the boom was closed. Two submarines that had attempted infiltration during the war had met unfortunate fates: on 23 November 1914 U-18

was rammed twice before running aground with the capture of her crew, and UB-116 was detected by hydrophone

and destroyed with the loss of all hands on 28 October 1918.

Scapa Flow provided the main anchorage for the British Grand Fleet

throughout most of the First World War, but in the interwar period this passed to Rosyth

, more conveniently located in the Firth of Forth

. Scapa Flow was however reactivated with the advent of the Second World War, becoming a base for the British Home Fleet

. Its natural and artificial defences, while still strong, were recognised as in need of improvement, and in the early weeks of the war were in the process of being strengthened by the provision of additional blockships.

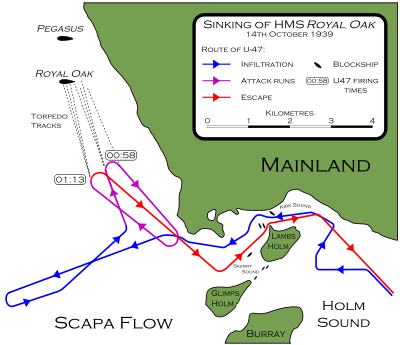

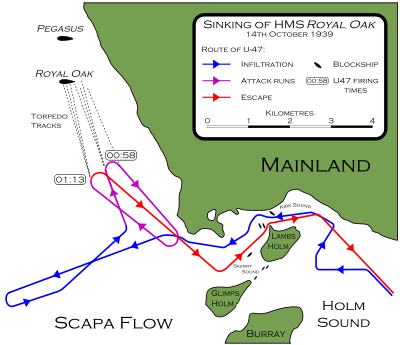

Kriegsmarine Commander of Submarines Karl Dönitz

Kriegsmarine Commander of Submarines Karl Dönitz

devised a plan to attack Scapa Flow by submarine within days of the outbreak of war. Its goal would be twofold: firstly, that displacing the Home Fleet from Scapa Flow would slacken the British North Sea

blockade and grant Germany greater freedom to attack the Atlantic convoys; secondly, the blow would be a symbolic act of vengeance, striking at the same location where the German High Seas Fleet

had surrendered and scuttled itself

following Germany's defeat in the First World War. Dönitz hand-picked Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien

for the task, scheduling the raid for the night of 13/14 October 1939, when the tides would be high and the night moonless.

Dönitz was aided by high-quality photographs from the recent reconnaissance overflight, which revealed the weaknesses of the defences and an abundance of targets. He directed Prien to enter Scapa Flow from its east via Kirk Sound, passing to the north of Lamb Holm

, a small low-lying island between Burray

and Mainland

. Prien initially mistook the more southerly Skerry Sound for the chosen route and his sudden realisation that U-47 was heading for the shallow blocked passage forced him to order a rapid turn to the northeast. On the surface, and illuminated by a bright display of the aurora borealis, the submarine threaded between the sunken blockship

s Seriano and Numidian, grounding itself temporarily on a cable strung from Seriano. It was briefly caught in the headlights of a taxi onshore, but the driver raised no alarm. On entering the harbour proper at 00:27 on 14 October, Prien entered a triumphant Wir sind in Scapa Flow!!! in the log and set a south-westerly course for several kilometres before reversing direction. To his surprise, the anchorage appeared to be almost empty; unknown to him, Forbes' order to disperse the fleet had removed some of the biggest targets. U-47 had been heading directly towards four warships, including the newly commissioned light cruiser

Belfast

, anchored offshore of Flotta

and Hoy

4-nautical-mile (8 km, 5 mi) distant, but Prien gave no indication that he had seen them.

On the reverse course, a lookout on the bridge spotted Royal Oak lying approximately 4,400 yards (4,000 m) to the north, correctly identifying it as a battleship of the Revenge class

. Mostly hidden behind her was a second ship, only the bow of which was visible to U-47. Prien mistook it to be a battlecruiser of the Renown class

, German intelligence later labelling it Repulse

. It was in fact the World War I seaplane tender

Pegasus.

At 00:58 U-47 fired a salvo of three torpedo

At 00:58 U-47 fired a salvo of three torpedo

es from its bow tubes, a fourth lodging in its tube. Two failed to find a target, but a single torpedo struck the bow of Royal Oak at 01:04, shaking the ship and waking the crew. Little visible damage was received, though the starboard anchor chain was severed, clattering noisily down through its slips. Initially, it was suspected that there had been an explosion in the ship's forward inflammable store, used to store materials such as kerosene. Mindful of the unexplained explosion that had destroyed HMS Vanguard

in Scapa Flow in 1917, an announcement was made over Royal Oak

system to check the magazine temperatures, but many sailors returned to their hammocks, unaware that the ship was under attack.

Prien turned his submarine and attempted another shot via his stern tube, but this too missed. Reloading his bow tubes, he doubled back and fired a salvo of three torpedoes, all at Royal Oak, This time he was successful: at 01:16 all three struck the battleship in quick succession amidships and detonated. The explosions blew a hole in the armoured deck, destroying the Stokers', Boys' and Marines

' mess

es and causing a loss of electrical power. Cordite from a magazine ignited and the ensuing fireball passed rapidly through the ship's internal spaces. Royal Oak quickly listed some 15°, sufficient to push the open starboard-side portholes below the waterline. She soon rolled further onto her side to 45°, hanging there for several minutes before disappearing beneath the surface at 01:29, 13 minutes after Prien's second strike. 833 men died with the ship, including Rear-Admiral Henry Blagrove

, commander of the Second Battleship Division. Over one hundred of the dead were Boy Seamen

, not yet 18 years old, the largest ever such loss in a single Royal Navy action. The admiral's wooden gig

, moored alongside, was dragged down with Royal Oak.

|-

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="40" | TIME

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="40" | FROM

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="40" | TO

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="250" | MESSAGE

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 02:00

| valign=top align=center | ACOS || valign=top align=center | ADMY || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 02:11

| valign=top align=center | ACOS || valign=top align=center | ADMY || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 05:06

| valign=top align=center | ADMY || valign=top align=center | ACOS || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 06:20

| valign=top align=center | ACOS || valign=top align=center | ADMY || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 07:04

| valign=top align=center | ADMY || valign=top align=center | ACOS || width="250" valign=top |

|}

Pennant number

In the modern Royal Navy, and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth, ships are identified by pennant numbers...

08) was a Revenge-class

Revenge class battleship

The Revenge class battleships were five battleships of the Royal Navy, ordered as World War I loomed on the horizon, and launched in 1914–1916...

battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

of the British Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. Launched in 1914 and completed in 1916, Royal Oak first saw action at the Battle of Jutland

Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland was a naval battle between the British Royal Navy's Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet during the First World War. The battle was fought on 31 May and 1 June 1916 in the North Sea near Jutland, Denmark. It was the largest naval battle and the only...

. In peacetime, she served in the Atlantic, Home and Mediterranean fleets, more than once coming under accidental attack. The ship drew worldwide attention in 1928 when her senior officers were controversially court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

led. Attempts to modernise Royal Oak throughout her 25-year career could not fix her fundamental lack of speed, and by the start of the Second World War, she was no longer suited to front-line duty.

On 14 October 1939, Royal Oak was anchored at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow

right|thumb|Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern endScapa Flow is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, United Kingdom, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray, South Ronaldsay and Hoy. It is about...

in Orkney, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

when she was torpedoed by the German submarine

Submarine

A submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

U-47. Of Royal Oak

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

, but the effect on wartime morale was considerable. The raid made an immediate celebrity and war hero out of the U-boat commander, Günther Prien

Günther Prien

Lieutenant Commander Günther Prien was one of the outstanding German U-boat aces of the first part of the Second World War, and the first U-boat commander to win the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Under Prien's command, the submarine sank over 30 Allied ships totaling about...

, who became the first Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine

The Kriegsmarine was the name of the German Navy during the Nazi regime . It superseded the Kaiserliche Marine of World War I and the post-war Reichsmarine. The Kriegsmarine was one of three official branches of the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany.The Kriegsmarine grew rapidly...

submarine officer to be awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was a grade of the 1939 version of the 1813 created Iron Cross . The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was the highest award of Germany to recognize extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership during World War II...

. To the British, the raid demonstrated that the Germans were capable of bringing the naval war to their home waters, and the shock resulted in rapidly arranged changes to dockland security.

Now lying almost upside-down in 100 feet (30 m) of water with her hull 16 feet (5 m) beneath the surface, Royal Oak is a designated war grave

War grave

A war grave is a burial place for soldiers or civilians who died during military campaigns or operations. The term does not only apply to graves: ships sunk during wartime are often considered to be war graves, as are military aircraft that crash into water...

. In an annual ceremony to mark the loss of the ship, Royal Navy divers place a White Ensign

White Ensign

The White Ensign or St George's Ensign is an ensign flown on British Royal Navy ships and shore establishments. It consists of a red St George's Cross on a white field with the Union Flag in the upper canton....

underwater at her stern. Unauthorised divers are prohibited from approaching the wreck at any time.

Construction

The Revenge class to which Royal Oak belonged was ordered in the 1913–14 EstimatesEstimates

In countries using the Westminster system the Estimates are a series of legislative proposals to parliament outlining how the government will spend its money....

to be a cheaper—but smaller and slower—coal-fired version of the earlier oil-fired Queen Elizabeth-class

Queen Elizabeth class battleship

The Queen Elizabeth-class battleships were a class of five super-dreadnoughts of the Royal Navy. The lead ship was named after Elizabeth I of England...

super-dreadnoughts. The design, seemingly a technological step backwards, was partly a response to fears that a dependence upon fuel oil—all of which had to be imported—could leave the class crippled in the event of a successful maritime blockade. High-quality coal, on the other hand, was in plentiful supply, and homeland supplies could be guaranteed. Furthermore, in contrast to the "Fast Squadron" Queen Elizabeths, the Revenge class were intended to be the heaviest-gunned vessels in the line of battle proper. Royal Oak and her sisters were the first major vessels for the Royal Navy whose design was supervised by the newly appointed Director of Naval Construction

Director of Naval Construction

The Director of Naval Construction was a senior British civil servant post in the Admiralty, that part of the British Civil Service that oversaw the Royal Navy. The post existed from 1860 to 1966....

, Sir Eustace Tennyson-D'Eyncourt.

HMNB Devonport

Her Majesty's Naval Base Devonport , is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy . HMNB Devonport is located in Devonport, in the west of the city of Plymouth in Devon, England...

on 15 January 1914, the fourth of her class. Concerned over the performance limitations of coal, and having secured new oil supplies with a contract agreed with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company

Anglo-Persian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company was founded in 1908 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Iran. It was the first company to extract petroleum from the Middle East...

, First Sea Lord

First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord is the professional head of the Royal Navy and the whole Naval Service; it was formerly known as First Naval Lord. He also holds the title of Chief of Naval Staff, and is known by the abbreviations 1SL/CNS...

Jackie Fisher rescinded the decision on coal in October 1914. Still under construction, Royal Oak was redesigned to employ eighteen oil-fired Yarrow

Yarrow Shipbuilders

Yarrow Limited , often styled as simply Yarrows, was a major shipbuilding firm based in the Scotstoun district of Glasgow on the River Clyde...

boilers supplying four Parsons

Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company

Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company was a British engineering company based in Wallsend, North England, on the River Tyne.-History:The company was founded by Charles Algernon Parsons in 1897 with £500,000 of capital, and specialised in building the steam turbine engines that he had invented for...

reaction steam turbines

Steam turbine

A steam turbine is a mechanical device that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam, and converts it into rotary motion. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Parsons in 1884....

, each directly driving a single 9.5 feet (2.9 m) three-bladed screw

Propeller

A propeller is a type of fan that transmits power by converting rotational motion into thrust. A pressure difference is produced between the forward and rear surfaces of the airfoil-shaped blade, and a fluid is accelerated behind the blade. Propeller dynamics can be modeled by both Bernoulli's...

. The battleship was launched on 17 November of that year, and after fitting-out, was commissioned on 1 May 1916 at a final cost of £2,468,269. Named after the oak tree

Royal Oak

The Royal Oak is the English oak tree within which King Charles II of England hid to escape the Roundheads following the Battle of Worcester in 1651. The tree was located in Boscobel Wood, which was part of the park of Boscobel House. Charles confirmed to Samuel Pepys in 1680 that while he was...

in which Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

hid following his defeat at the 1651 Battle of Worcester

Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 at Worcester, England and was the final battle of the English Civil War. Oliver Cromwell and the Parliamentarians defeated the Royalist, predominantly Scottish, forces of King Charles II...

, she was the eighth Royal Navy vessel to bear the name Royal Oak

HMS Royal Oak

Eight ships of the Royal Navy have been named HMS Royal Oak, after the Royal Oak in which Charles II hid himself during his flight from the country in the English Civil War:...

, replacing a pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleship is the general term for all of the types of sea-going battleships built between the mid-1890s and 1905. Pre-dreadnoughts replaced the ironclad warships of the 1870s and 1880s...

scrapped in 1914. While building she was temporarily assigned the pennant number

Pennant number

In the modern Royal Navy, and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth, ships are identified by pennant numbers...

67.

Royal Oak was refitted between 1922 and 1924, when her anti-aircraft defences were upgraded by replacing the original QF 3 inches (76.2 mm) 20 cwt AA guns

QF 3 inch 20 cwt

The QF 3 inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun became the standard anti-aircraft gun used in the home defence of the United Kingdom against German airships and bombers and on the Western Front in World War I. It was also common on British warships in World War I and submarines in World War II...

with QF 4 inches (101.6 mm)

QF 4 inch Mk V naval gun

The QF 4 inch Mk V gun was a Royal Navy gun of World War I which was adapted on HA mountings to the heavy anti-aircraft role both at sea and on land, and was also used as a coast defence gun.-Naval service:...

high-angle mounts. Fire-control system

Fire-control system

A fire-control system is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director, and radar, which is designed to assist a weapon system in hitting its target. It performs the same task as a human gunner firing a weapon, but attempts to do so faster and more...

s and rangefinder

Rangefinder

A rangefinder is a device that measures distance from the observer to a target, for the purposes of surveying, determining focus in photography, or accurately aiming a weapon. Some devices use active methods to measure ; others measure distance using trigonometry...

s for main and secondary batteries were modernised, and underwater protection improved by 'bulging

Anti-torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge is a form of passive defence against naval torpedoes that featured in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars.-Theory and form:...

' the ship. The watertight chambers, attached to either side of the hull, were designed to reduce the effect of torpedo blasts and improve stability, but at the same time widened the ship's beam by over 13 feet (4 m).

A brief refit in the spring of 1927 saw the addition of two more 4 inches (101.6 mm) high-angle AA guns and the removal of the two 6 inches (152.4 mm) guns from the shelter deck. The ship received a final refit between 1934 and 1936, when her deck armour was increased to 5 inches (12.7 cm) over the magazines

Magazine (artillery)

Magazine is the name for an item or place within which ammunition is stored. It is taken from the Arabic word "makahazin" meaning "warehouse".-Ammunition storage areas:...

and to 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) over the engine rooms. In addition to a general modernisation of the ship's systems, a catapult for a spotter float plane was installed above X–turret, and anti-aircraft defences were strengthened by doubling up each of the 4 inches (101.6 mm) AA guns and adding a pair of octuple Mark VIII pompom guns to sponson

Sponson

Sponsons are projections from the sides of a watercraft, for protection, stability, or the mounting of equipment such as armaments or lifeboats, etc...

s abreast the funnel. The mainmast was reconstructed as a tripod to support the weight of a radio-direction finding

Radio direction finder

A radio direction finder is a device for finding the direction to a radio source. Due to low frequency propagation characteristic to travel very long distances and "over the horizon", it makes a particularly good navigation system for ships, small boats, and aircraft that might be some distance...

office and a second High-angle Control Station

HACS

HACS, an acronym of High Angle Control System, was a British anti-aircraft fire-control system employed by the Royal Navy from 1931 onwards and used widely during World War II...

. The extra armour and equipment made Royal Oak one of the best equipped of the Revenge class, but the additional weight caused her to sit lower in the water, lowering her top speed by several knots.

First World War

4th Battle Squadron (United Kingdom)

The British Royal Navy 4th Battle Squadron was a squadron consisting of battleships. The 4th Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Home Fleet. During World War I the Home Fleet was renamed the Grand Fleet...

of the British Grand Fleet

British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main fleet of the British Royal Navy during the First World War.-History:It was formed in 1914 by the British Atlantic Fleet combined with the Home Fleet and it included 35-40 state-of-the-art capital ships. It was initially commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe...

, and within the month was ordered, along with most of the fleet, to engage the German High Seas Fleet

High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet was the battle fleet of the German Empire and saw action during World War I. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet was renamed as the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; he envisioned a force powerful enough to...

in the Battle of Jutland

Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland was a naval battle between the British Royal Navy's Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet during the First World War. The battle was fought on 31 May and 1 June 1916 in the North Sea near Jutland, Denmark. It was the largest naval battle and the only...

. Under the command of Captain Crawford Maclachlan, Royal Oak left Scapa Flow on the evening of 30 May in the company of the battleships Superb

HMS Superb (1907)

HMS Superb was a of the British Royal Navy. She was built in Elswick at a cost of £1,744,287, and was completed on 19 June 1909. She was only the fourth dreadnought-type battleship to be completed anywhere in the world, being preceded only by and by her two sister-ships and -Origin:The advent of...

, Canada and Admiral Jellicoe's

John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, GCB, OM, GCVO was a British Royal Navy admiral who commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland in World War I...

flagship Iron Duke

HMS Iron Duke (1912)

HMS Iron Duke was a battleship of the Royal Navy, the lead ship of her class, named in honour of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. She served as the flagship of the Grand Fleet during the First World War, including at the Battle of Jutland...

. The next day's indecisive battle saw Royal Oak fire a total of thirty-eight 15 inches (381 mm) and eighty-four 6 inches (152.4 mm) shells, claiming three hits on the battlecruiser Derfflinger

SMS Derfflinger

SMS Derfflinger"SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German. was a battlecruiser of the German Kaiserliche Marine built just before the outbreak of World War I. She was the lead vessel of her class of three ships; her sister ships were and...

, putting one of its turrets out of action, and a hit on the cruiser Wiesbaden. She avoided damage herself, despite being straddled by shellfire on one occasion.

Following the battle, Royal Oak was reassigned to the First Battle Squadron. On 5 November 1918—the final week of the First World War—she was anchored off Burntisland

Burntisland

Burntisland is a town and former royal burgh in Fife, Scotland on the Firth of Forth. According to an estimate taken in 2008, the town has a population of 5,940....

in the Firth of Forth

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth is the estuary or firth of Scotland's River Forth, where it flows into the North Sea, between Fife to the north, and West Lothian, the City of Edinburgh and East Lothian to the south...

accompanied by the aircraft carrier

Aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship designed with a primary mission of deploying and recovering aircraft, acting as a seagoing airbase. Aircraft carriers thus allow a naval force to project air power worldwide without having to depend on local bases for staging aircraft operations...

Campania

HMS Campania (1914)

HMS Campania was a seaplane tender and aircraft carrier, converted from an elderly ocean liner by the Royal Navy early in the First World War. After her conversion was completed in mid-1915 the ship spent her time conducting trials and exercises with the Grand Fleet...

(formerly a Blue Riband

Blue Riband

The Blue Riband is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. Under the unwritten rules, the record is based on average speed...

winner for the Cunard Line prior to its conversion for wartime use) and battlecruiser

Battlecruiser

Battlecruisers were large capital ships built in the first half of the 20th century. They were developed in the first decade of the century as the successor to the armoured cruiser, but their evolution was more closely linked to that of the dreadnought battleship...

Glorious

HMS Glorious (77)

HMS Glorious was the second of the cruisers built for the British Royal Navy during the First World War. Designed to support the Baltic Project championed by the First Sea Lord, Lord Fisher, they were very lightly armoured and armed with only a few heavy guns. Glorious was completed in late 1916...

. A sudden Force 10

Beaufort scale

The Beaufort Scale is an empirical measure that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea or on land. Its full name is the Beaufort Wind Force Scale.-History:...

squall caused Campania to drag her anchor, collide with Royal Oak and then with the 22,000-ton Glorious. Both Royal Oak and Glorious suffered only minor damage; Campania, however, was holed by her initial collision with Royal Oak. The ship's engine rooms flooded, and she settled by the stern and sank five hours later, though without loss of life.

At the end of the First World War Royal Oak escorted several vessels of the surrendering German High Seas Fleet from the Firth of Forth

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth is the estuary or firth of Scotland's River Forth, where it flows into the North Sea, between Fife to the north, and West Lothian, the City of Edinburgh and East Lothian to the south...

to their internment in Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow

right|thumb|Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern endScapa Flow is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, United Kingdom, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray, South Ronaldsay and Hoy. It is about...

, and was present at a ceremony in Pentland Firth

Pentland Firth

The Pentland Firth , which is actually more of a strait than a firth, separates the Orkney Islands from Caithness in the north of Scotland.-Etymology:...

to greet other ships as they followed.

Between the wars

Grand Harbour

Grand Harbour is a natural harbour on the island of Malta. It has been used as a harbour since at least Phoenician times...

, Malta

Malta

Malta , officially known as the Republic of Malta , is a Southern European country consisting of an archipelago situated in the centre of the Mediterranean, south of Sicily, east of Tunisia and north of Libya, with Gibraltar to the west and Alexandria to the east.Malta covers just over in...

. In early 1928, this duty saw the notorious incident the contemporary press dubbed the "Royal Oak Mutiny". What began as a simple dispute between Rear-Admiral Bernard Collard and Royal Oak

Kenneth Dewar

Vice-Admiral Kenneth Gilbert Balmain Dewar, CBE, RN was an officer of the Royal Navy. After specialising as a gunnery officer, Dewar became a staff officer and a controversial student of naval tactics before seeing extensive service during the First World War...

and Commander Henry Daniel over the band at the ship's wardroom

Wardroom

The wardroom is the mess-cabin of naval commissioned officers above the rank of Midshipman. The term the wardroom is also used to refer to those individuals with the right to occupy that wardroom, meaning "the officers of the wardroom"....

dance, descended into a bitter personal feud that spanned several months. Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew; in return, Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman". When Dewar and Daniel wrote letters of complaint to Collard's superior, Vice-Admiral John Kelly, he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their flag admiral had irretrievably broken down, Keyes removed all three from their posts and sent them back to England, postponing a major naval exercise. The press picked up on the story worldwide, describing the affair—with some hyperbole—as a "mutiny". Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the King

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, who summoned First Lord of the Admiralty William Bridgeman

William Clive Bridgeman

William Clive Bridgeman, 1st Viscount Bridgeman, PC, JP, DL was a British Conservative politician and peer. He notably served as Home Secretary between 1922 and 1924.-Background and education:...

for an explanation.

For their letters of complaint, Dewar and Daniel were controversially charged with writing subversive documents. In a pair of

highly publicised courts-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

, both were found guilty and severely reprimanded, leading Daniel to resign from the Navy. Collard himself was criticised for the excesses of his conduct by the press and in Parliament, and on being denounced by Bridgeman as "unfitted to hold further high command", was forcibly retired from service.

Of the three, only Dewar escaped with his career, albeit a damaged one: he remained in the Royal Navy in a series of more minor commands and was promoted to Rear-Admiral the following year, one day before his retirement. Daniel attempted a career in journalism, but when this and other ventures were unsuccessful, he disappeared into obscurity amid poor health in South Africa. Collard retreated to private life and never spoke publicly of the incident again.

The scandal proved an embarrassment to the reputation of the Royal Navy, then still the world's largest, and it was satirised at home and abroad through editorials, cartoons, and even a comic jazz oratorio composed by Erwin Schulhoff

Erwin Schulhoff

Erwin Schulhoff was a Czech composer and pianist.-Life:Born in Prague of Jewish-German origin, Schulhoff was one of the brightest figures in a generation of European musicians whose successful careers were prematurely terminated by the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany...

. One consequence of the damaging affair was an undertaking from the Admiralty to review the means by which naval officers might bring complaints against the conduct of their superiors.

Spanish Civil War

During the Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, Royal Oak was tasked with conducting 'non-intervention patrols' around the Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

. On such a patrol and steaming some 30 nmi (55.6 km; 34.5 mi) east of Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

on 2 February 1937, she came under aerial attack by three aircraft of the Republican

Second Spanish Republic

The Second Spanish Republic was the government of Spain between April 14 1931, and its destruction by a military rebellion, led by General Francisco Franco....

forces. They dropped three bombs (two of which exploded) within 3 cables

Cable length

A cable length or cable's length is a nautical unit of measure equal to one tenth of a nautical mile or 100 fathoms, or sometimes 120 fathoms. The unit is named after the length of a ship's anchor cable in the age of sail...

(555 m) of the starboard bow, though causing no damage. The British chargé d'affaires

Chargé d'affaires

In diplomacy, chargé d’affaires , often shortened to simply chargé, is the title of two classes of diplomatic agents who head a diplomatic mission, either on a temporary basis or when no more senior diplomat has been accredited.-Chargés d’affaires:Chargés d’affaires , who were...

protested the incident to the Republican Government, which admitted its error and apologised for the attack. Later that same month, while stationed offshore of Valencia on 23 February 1937 during an aerial bombardment by the Nationalists, she was accidentally struck by an anti-aircraft shell fired from a Republican position. Five men were injured, including Royal Oak

Act of God

Act of God is a legal term for events outside of human control, such as sudden floods or other natural disasters, for which no one can be held responsible.- Contract law :...

". In May 1937, she and escorted SS Habana, a liner carrying Basque

Basque people

The Basques as an ethnic group, primarily inhabit an area traditionally known as the Basque Country , a region that is located around the western end of the Pyrenees on the coast of the Bay of Biscay and straddles parts of north-central Spain and south-western France.The Basques are known in the...

child refugees, to England. In July, as the war in northern Spain flared up, Royal Oak, along with the battleship

rescued the steamer Gordonia when Spanish nationalist warships attempted to capture her off Santander

Santander, Cantabria

The port city of Santander is the capital of the autonomous community and historical region of Cantabria situated on the north coast of Spain. Located east of Gijón and west of Bilbao, the city has a population of 183,446 .-History:...

. She was however unable on 14 July to prevent the seizure of the British freighter Molton by the Spanish nationalist cruiser Almirante Cervera

Spanish cruiser Almirante Cervera

Almirante Cervera was a light cruiser of the Cervera class of the Spanish Navy. She was named after the Spanish admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete, commander of the Spanish naval forces in Cuba during the Spanish-American War...

while trying to enter Santander. The merchantmen had been engaged in the evacuation of refugees.

This same period saw Royal Oak star alongside fourteen other Royal Navy vessels in the 1937 British film melodrama

Melodrama

The term melodrama refers to a dramatic work that exaggerates plot and characters in order to appeal to the emotions. It may also refer to the genre which includes such works, or to language, behavior, or events which resemble them...

Our Fighting Navy

Our Fighting Navy

Our Fighting Navy is a 1937 British action film directed by Norman Walker and starring Robert Douglas, Richard Cromwell and Hazel Terry. A British warship intervenes to protect British subjects and prevent a rebellion in a South American republic...

, the plot of which centres around a coup in the fictional South American republic of Bianco. Royal Oak portrays a rebel battleship El Mirante, whose commander forces a British captain (played by Robert Douglas

Robert Douglas (actor)

Robert Douglas was born as Robert Douglas Finlayson in Fenny Stratford, Buckinghamshire. He was a successful stage and film actor, a television director and producer....

) into choosing between his lover and his duty. The film was poorly received by critics, but gained some redemption through its dramatic scenes of naval action.

Second World War

Flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, reflecting the custom of its commander, characteristically a flag officer, flying a distinguishing flag...

of the Second Battleship Squadron based in Portsmouth

HMNB Portsmouth

Her Majesty's Naval Base Portsmouth is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the British Royal Navy...

. On 24 November 1938, she returned the body of the British-born Queen Maud of Norway

Maud of Wales

Princess Maud of Wales was Queen of Norway as spouse of King Haakon VII. She was a member of the British Royal Family as the youngest daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark and granddaughter of Queen Victoria and also of Christian IX of Denmark. She was the younger sister of George V...

, who had died in London, to a state funeral in Oslo, accompanied by her husband King Haakon VII

Haakon VII of Norway

Haakon VII , known as Prince Carl of Denmark until 1905, was the first king of Norway after the 1905 dissolution of the personal union with Sweden. He was a member of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg...

. Paying off in December 1938, Royal Oak was recommissioned the following June, and in the late summer of 1939 embarked on a short training cruise in the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

in preparation for another 30-month tour of the Mediterranean,. for which her crew were pre-issued tropical uniforms. As hostilities loomed, the battleship was instead dispatched north to Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow

right|thumb|Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern endScapa Flow is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, United Kingdom, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray, South Ronaldsay and Hoy. It is about...

, and was at anchor there when war was declared on 3 September.

In October 1939, Royal Oak joined the search for the German battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

Gneisenau

German battleship Gneisenau

Gneisenau was a German capital ship, alternatively described as a battleship and battlecruiser, of the German Kriegsmarine. She was the second vessel of her class, which included one other ship, Scharnhorst. The ship was built at the Deutsche Werke dockyard in Kiel; she was laid down on 6 May 1935...

, which had been ordered into the North Sea as a diversion for the commerce-raiding

Commerce raiding

Commerce raiding or guerre de course is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt the logistics of an enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging the combatants themselves or enforcing a blockade against them.Commerce raiding was heavily criticised by...

pocket battleships Deutschland

German pocket battleship Deutschland

Deutschland was the lead ship of her class of heavy cruisers which served with the Kriegsmarine of Nazi Germany during World War II. Ordered by the Weimar government for the Reichsmarine, she was laid down at the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel in February 1929 and completed by April 1933...

and Graf Spee. The search was ultimately fruitless, particularly for Royal Oak, whose top speed, by then less than 20 kn (39.2 km/h; 24.4 mph), was inadequate to keep up with the rest of the fleet. On 12 October, Royal Oak returned to the defences of Scapa Flow in poor shape, battered by North Atlantic storms: many of her Carley float

Carley float

The Carley float was a form of invertible liferaft designed by American inventor Horace Carley . Supplied mainly to warships, it saw widespread use in a number of navies during peacetime and both World Wars until superseded by more modern rigid or inflatable designs...

s had been smashed and several of the smaller-calibre guns rendered inoperable. The mission had underlined the obsolescence of the 25-year-old warship. Concerned that a recent overflight by German reconnaissance aircraft heralded an imminent air attack upon Scapa Flow, Admiral of the Home Fleet Charles Forbes ordered most of the fleet to disperse to safer ports. Royal Oak however remained behind, her anti-aircraft guns still deemed a useful addition to Scapa's otherwise scarce air defences.

Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow made a near-ideal anchorage. Situated at the centre of the Orkney Islands off the north coast of Scotland, the natural harbour, large enough to contain the entire Grand Fleet, was surrounded by a ring of islands separated by shallow channels subject to fast-racing tideTide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the moon and the sun and the rotation of the Earth....

s. The threat from U-boats had however long been realised, and a series of countermeasures were installed during the early years of the First World War. Blockship

Blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used.It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of HMS Hood at Portland Harbour; or it may be brought by enemy raiders and used to...

s were sunk at critical points, and floating booms deployed to block the three widest channels. Operated by tugboats to allow the passage of friendly shipping, it was considered possible—but highly unlikely—that a daring U-boat commander could attempt to race through undetected before the boom was closed. Two submarines that had attempted infiltration during the war had met unfortunate fates: on 23 November 1914 U-18

SM U-18

SM U-18 was one of 329 submarines serving in the Imperial German Navy in World War I. U-18 engaged in the commerce warfare in the First Battle of the Atlantic.Launched in October 1914, she was commanded by Kaptlt...

was rammed twice before running aground with the capture of her crew, and UB-116 was detected by hydrophone

Hydrophone

A hydrophone is a microphone designed to be used underwater for recording or listening to underwater sound. Most hydrophones are based on a piezoelectric transducer that generates electricity when subjected to a pressure change...

and destroyed with the loss of all hands on 28 October 1918.

Scapa Flow provided the main anchorage for the British Grand Fleet

British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main fleet of the British Royal Navy during the First World War.-History:It was formed in 1914 by the British Atlantic Fleet combined with the Home Fleet and it included 35-40 state-of-the-art capital ships. It was initially commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe...

throughout most of the First World War, but in the interwar period this passed to Rosyth

Rosyth

Rosyth is a town located on the Firth of Forth, three miles south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to an estimate taken in 2008, the town has a population of 12,790....

, more conveniently located in the Firth of Forth

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth is the estuary or firth of Scotland's River Forth, where it flows into the North Sea, between Fife to the north, and West Lothian, the City of Edinburgh and East Lothian to the south...

. Scapa Flow was however reactivated with the advent of the Second World War, becoming a base for the British Home Fleet

British Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy which operated in the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967.-Pre–First World War:...

. Its natural and artificial defences, while still strong, were recognised as in need of improvement, and in the early weeks of the war were in the process of being strengthened by the provision of additional blockships.

Special Operation P: the raid by U-47

Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz was a German naval commander during World War II. He started his career in the German Navy during World War I. In 1918, while he was in command of , the submarine was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner...

devised a plan to attack Scapa Flow by submarine within days of the outbreak of war. Its goal would be twofold: firstly, that displacing the Home Fleet from Scapa Flow would slacken the British North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

blockade and grant Germany greater freedom to attack the Atlantic convoys; secondly, the blow would be a symbolic act of vengeance, striking at the same location where the German High Seas Fleet

High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet was the battle fleet of the German Empire and saw action during World War I. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet was renamed as the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; he envisioned a force powerful enough to...

had surrendered and scuttled itself

Scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow

The scuttling of the German fleet took place at the Royal Navy's base at Scapa Flow, in Scotland, after the end of the First World War. The High Seas Fleet had been interned there under the terms of the Armistice whilst negotiations took place over the fate of the ships...

following Germany's defeat in the First World War. Dönitz hand-picked Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien

Günther Prien

Lieutenant Commander Günther Prien was one of the outstanding German U-boat aces of the first part of the Second World War, and the first U-boat commander to win the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Under Prien's command, the submarine sank over 30 Allied ships totaling about...

for the task, scheduling the raid for the night of 13/14 October 1939, when the tides would be high and the night moonless.

Dönitz was aided by high-quality photographs from the recent reconnaissance overflight, which revealed the weaknesses of the defences and an abundance of targets. He directed Prien to enter Scapa Flow from its east via Kirk Sound, passing to the north of Lamb Holm

Lamb Holm

Lamb Holm is a small uninhabited island in Orkney, Scotland. The remarkable Italian Chapel, constructed during the Second World War, is the island's main attraction.-Geography:...

, a small low-lying island between Burray

Burray

Burray is one of the Orkney Islands in Scotland. It lies to the east of Scapa Flow and is one of a chain of islands linked by the Churchill Barriers.-Geography and geology:...

and Mainland

The Mainland, Orkney

The Mainland is the main island of Orkney, Scotland. Both of Orkney's burghs, Kirkwall and Stromness, lie on the island, which is also the heart of Orkney's ferry and air connections....

. Prien initially mistook the more southerly Skerry Sound for the chosen route and his sudden realisation that U-47 was heading for the shallow blocked passage forced him to order a rapid turn to the northeast. On the surface, and illuminated by a bright display of the aurora borealis, the submarine threaded between the sunken blockship

Blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used.It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of HMS Hood at Portland Harbour; or it may be brought by enemy raiders and used to...

s Seriano and Numidian, grounding itself temporarily on a cable strung from Seriano. It was briefly caught in the headlights of a taxi onshore, but the driver raised no alarm. On entering the harbour proper at 00:27 on 14 October, Prien entered a triumphant Wir sind in Scapa Flow!!! in the log and set a south-westerly course for several kilometres before reversing direction. To his surprise, the anchorage appeared to be almost empty; unknown to him, Forbes' order to disperse the fleet had removed some of the biggest targets. U-47 had been heading directly towards four warships, including the newly commissioned light cruiser

Light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small- or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck...

Belfast

HMS Belfast (C35)

HMS Belfast is a museum ship, originally a Royal Navy light cruiser, permanently moored in London on the River Thames and operated by the Imperial War Museum....

, anchored offshore of Flotta

Flotta

Flotta is a small island in Orkney, Scotland, lying in Scapa Flow. The island is known for its large oil terminal and is linked by Orkney Ferries to Houton on the Orkney Mainland and Lyness and Longhope on Hoy....

and Hoy

Hoy

Hoy is an island in Orkney, Scotland. With an area of it is the second largest in the archipelago after the Mainland. It is connected by a causeway called The Ayre to South Walls...

4-nautical-mile (8 km, 5 mi) distant, but Prien gave no indication that he had seen them.

On the reverse course, a lookout on the bridge spotted Royal Oak lying approximately 4,400 yards (4,000 m) to the north, correctly identifying it as a battleship of the Revenge class

Revenge class battleship

The Revenge class battleships were five battleships of the Royal Navy, ordered as World War I loomed on the horizon, and launched in 1914–1916...

. Mostly hidden behind her was a second ship, only the bow of which was visible to U-47. Prien mistook it to be a battlecruiser of the Renown class

Renown class battlecruiser

The Renown class consisted of a pair of battlecruisers built during the First World War for the Royal Navy. They were originally laid down as improved versions of the s. Their construction was suspended on the outbreak of war on the grounds they would not be ready in a timely manner...

, German intelligence later labelling it Repulse

HMS Repulse (1916)

HMS Repulse was a Renown-class battlecruiser of the Royal Navy built during the First World War. She was originally laid down as an improved version of the s. Her construction was suspended on the outbreak of war on the grounds she would not be ready in a timely manner...

. It was in fact the World War I seaplane tender

Seaplane tender

A seaplane tender is a ship that provides facilities for operating seaplanes. These ships were the first aircraft carriers and appeared just before the First World War.-History:...

Pegasus.

Torpedo

The modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

es from its bow tubes, a fourth lodging in its tube. Two failed to find a target, but a single torpedo struck the bow of Royal Oak at 01:04, shaking the ship and waking the crew. Little visible damage was received, though the starboard anchor chain was severed, clattering noisily down through its slips. Initially, it was suspected that there had been an explosion in the ship's forward inflammable store, used to store materials such as kerosene. Mindful of the unexplained explosion that had destroyed HMS Vanguard

HMS Vanguard (1909)

The eighth HMS Vanguard of the British Royal Navy was a St Vincent-class battleship, an enhancement of the "" design built by Vickers at Barrow-in-Furness...

in Scapa Flow in 1917, an announcement was made over Royal Oak

Tannoy

Tannoy Ltd is a Scottish-based manufacturer of loudspeakers and public-address systems. The company was founded in London, England as Tulsemere Manufacturing Company in 1926, but has been based in Coatbridge, Scotland, since the 1970s...

system to check the magazine temperatures, but many sailors returned to their hammocks, unaware that the ship was under attack.

Prien turned his submarine and attempted another shot via his stern tube, but this too missed. Reloading his bow tubes, he doubled back and fired a salvo of three torpedoes, all at Royal Oak, This time he was successful: at 01:16 all three struck the battleship in quick succession amidships and detonated. The explosions blew a hole in the armoured deck, destroying the Stokers', Boys' and Marines

Royal Marines

The Corps of Her Majesty's Royal Marines, commonly just referred to as the Royal Marines , are the marine corps and amphibious infantry of the United Kingdom and, along with the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, form the Naval Service...

' mess

Mess

A mess is the place where military personnel socialise, eat, and live. In some societies this military usage has extended to other disciplined services eateries such as civilian fire fighting and police forces. The root of mess is the Old French mes, "portion of food" A mess (also called a...

es and causing a loss of electrical power. Cordite from a magazine ignited and the ensuing fireball passed rapidly through the ship's internal spaces. Royal Oak quickly listed some 15°, sufficient to push the open starboard-side portholes below the waterline. She soon rolled further onto her side to 45°, hanging there for several minutes before disappearing beneath the surface at 01:29, 13 minutes after Prien's second strike. 833 men died with the ship, including Rear-Admiral Henry Blagrove

Henry Blagrove

Rear-Admiral Henry Evelyn Charles Blagrove was the first British Royal Navy officer of flag rank to be killed in the Second World War...

, commander of the Second Battleship Division. Over one hundred of the dead were Boy Seamen

Boy Seaman

A boy seaman is a boy who serves as seaman and/or is trained for such service.-Royal Navy:In the British naval forces, where there was a need to recruit enough hands to man the vast fleet of the British Empire, extensive regulations existed concerning the selection and status of boys enlisted to...

, not yet 18 years old, the largest ever such loss in a single Royal Navy action. The admiral's wooden gig

Captain's Gig

The captain's gig is a boat used on naval ships as the captain's private taxi. It is a catchall phrase for this type of craft and over the years it has gradually increased in size, changed with the advent of new technologies for locomotion, and been crafted from increasingly more durable...

, moored alongside, was dragged down with Royal Oak.

Rescue efforts

Admiral Commanding Orkney and Shetland (ACOS)|-

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="40" | TIME

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="40" | FROM

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="40" | TO

!colspan="1" align=center bgcolor="#EFEFEF" width="250" | MESSAGE

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 02:00

| valign=top align=center | ACOS || valign=top align=center | ADMY || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 02:11

| valign=top align=center | ACOS || valign=top align=center | ADMY || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 05:06

| valign=top align=center | ADMY || valign=top align=center | ACOS || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 06:20

| valign=top align=center | ACOS || valign=top align=center | ADMY || width="250" valign=top |

|-

! valign=top bgcolor="#EFEFEF" | 07:04

| valign=top align=center | ADMY || valign=top align=center | ACOS || width="250" valign=top |

|}

The tender

Ship's tender

A ship's tender, usually referred to as a tender, is a boat, or a larger ship used to service a ship, generally by transporting people and/or supplies to and from shore or another ship...

Daisy 2, skippered by John Gatt RNR

Royal Naval Reserve

The Royal Naval Reserve is the volunteer reserve force of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. The present Royal Naval Reserve was formed in 1958 by merging the original Royal Naval Reserve and the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve , a reserve of civilian volunteers founded in 1903...

, had been tied up for the night to Royal Oak

Many of Royal Oak

Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

The Distinguished Service Cross is the third level military decoration awarded to officers, and other ranks, of the British Armed Forces, Royal Fleet Auxiliary and British Merchant Navy and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries.The DSC, which may be awarded posthumously, is...

, the only military award made by the British in connection with the disaster.

Aftermath

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

released news of the sinking by late morning on 14 October, and its broadcasts were received by the German listening services and by U-47 itself. Divers

Surface supplied diving

Surface supplied diving refers to divers using equipment supplied with breathing gas using a diver's umbilical from the surface, either from the shore or from a diving support vessel sometimes indirectly via a diving bell...

sent down on the morning after the explosion discovered remnants of a German torpedo, confirming the means of attack. On 17 October First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

officially announced the loss of Royal Oak to the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, first conceding that the raid had been "a remarkable exploit of professional skill and daring", but then declaring that the loss would not materially affect the naval balance of power. An Admiralty Board of Enquiry convened between 18 and 24 October to establish the circumstances under which the anchorage had been penetrated. In the meantime, the Home Fleet was ordered to remain at safer ports until security issues at Scapa could be addressed. Churchill was obliged to respond to questions in the House as to why Royal Oak had had aboard so many Boys

Boy Seaman

A boy seaman is a boy who serves as seaman and/or is trained for such service.-Royal Navy:In the British naval forces, where there was a need to recruit enough hands to man the vast fleet of the British Empire, extensive regulations existed concerning the selection and status of boys enlisted to...

, almost all of whom lost their lives. He defended the Royal Navy tradition of sending boys aged 15 to 17 to sea, but the practice was generally discontinued shortly after the disaster, and under 18-year-olds served on active warships in only the most exceptional circumstances.

The Nazi Propaganda Ministry was quick to capitalise on the successful raid, and radio broadcasts by the popular journalist Hans Fritzsche

Hans Fritzsche

Hans Georg Fritzsche was a senior German Nazi official, ending the war as Ministerialdirektor at the Propagandaministerium.- Career :...

displayed the triumph felt throughout Germany. Prien and his crew reached Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea.-History:...

at 11:44 on 17 October and were immediately greeted as heroes, learning that Prien had been awarded the Iron Cross

Iron Cross

The Iron Cross is a cross symbol typically in black with a white or silver outline that originated after 1219 when the Kingdom of Jerusalem granted the Teutonic Order the right to combine the Teutonic Black Cross placed above a silver Cross of Jerusalem....