Karl Dönitz

Encyclopedia

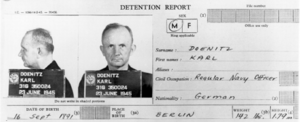

Karl Dönitz (ˈdøːnɪts; 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German

naval commander during World War II

. He started his career in the German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine

, or "Imperial Navy") during World War I

. In 1918, while he was in command of , the submarine

was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner. While in a prisoner of war

camp, he formulated what he later called Rudeltaktik ("pack tactic", commonly called "wolfpack"). At the start of World War II, he was the senior submarine officer in the German Navy. In January 1943, Dönitz achieved the rank of Großadmiral (Grand Admiral

) and replaced Grand Admiral Erich Raeder

as Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine). On 30 April 1945, after the death of Adolf Hitler

and in accordance with Hitler's last will and testament

, Dönitz was named Hitler's successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State

), with the title of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. On 7 May 1945, he ordered Alfred Jodl

to sign the German instruments of surrender in Rheims, France. Dönitz remained as head of the Flensburg Government

, as it became known, until it was dissolved by the Allied powers on 23 May.

in Berlin

, Germany

to Anna Beyer and Emil Dönitz, an engineer. Karl had an older brother, Friedrich.

In 1910, Dönitz enlisted in the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine

). He became a sea-cadet

(Seekadett) on 4 April. On 15 April 1911, he became a midshipman

(Fähnrich zur See), the rank given to those who had served for one year as officer's apprentice and had passed their first examination.

On 27 September 1913, Dönitz was commissioned as a Acting Sub-Lieutenant (Leutnant zur See). When World War I

began, he served in the light cruiser

in the Mediterranean Sea

. In August 1914, Breslau and the battlecruiser were sold to the Ottoman

navy; the ships were renamed the Midilli and the Yavuz Sultan Selim, respectively. They began operating out of Constantinople

(now Istanbul

), under Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon

, engaging Russian

forces in the Black Sea

. On 22 March 1916, Dönitz was promoted to Navy First Lieutenant

(Oberleutnant zur See). When Midilli put into dock for repairs, he was temporarily assigned as airfield commander at the Dardanelles

. From there, he requested a transfer to the submarine forces, which became effective in October 1916. He served as watch officer on , and from February 1918 onward as commander of . On 5 September 1918, he became commander of , operating in the Mediterranean. On 4 October, this boat was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner on the island of Malta.

as a prisoner of war

until his release in July 1919. He returned to Germany in 1920.

During the interwar period

, Dönitz continued his naval career in the naval arm of the Weimar Republic

's Armed Forces (Reichswehr

). On 10 January 1921, he became a Lieutenant

(Kapitänleutnant) in the new German Navy (Vorläufige Reichsmarine). Dönitz commanded torpedo boat

s by 1928, becoming a Lieutenant-Commander (Korvettenkapitän) on 1 November of that same year.

On 1 September 1933, Dönitz became a full Commander

(Fregattenkapitän) and, in 1934, was put in command of the cruiser Emden

. Emden was the ship on which cadets and midshipmen took a year-long world cruise in preparation for a future officer's commission.

On 1 September 1935, Dönitz was promoted to Captain

(Kapitän zur See). He was placed in command of the 1st U-boat Flotilla Weddigen, which included , , and .

During 1935, the Weimar Republic

's Navy, the Reichsmarine

, was replaced by the Navy of Nazi Germany

, the Kriegsmarine

.

Throughout 1935 and 1936, Dönitz had misgivings regarding submarines due to German overestimation of the capabilities of British ASDIC. In reality, ASDIC could detect only one submarine in ten during exercises. In the words of Alan Hotham, British Director of Naval Intelligence

, ASDIC was a "huge bluff".

German doctrine at the time, based on the work of American Naval Captain Alfred Mahan and shared by all major navies, called for submarines to be integrated with surface fleets and employed against enemy warships. By November 1937, Dönitz became convinced that a major campaign against merchant shipping was practical and began pressing for the conversion of the German fleet almost entirely to U-boats. He advocated a strategy of attacking only merchant ships, targets relatively safe to attack. He pointed out that destroying Britain's fleet of oil tankers would starve the Royal Navy

of supplies needed to run its ships, which would be just as effective as sinking them. He thought a German fleet of 300 of the newer Type VII U-boats could knock Britain out of the war.

Dönitz revived the World War I idea of grouping several submarines together into a "wolfpack" to overwhelm a merchant convoy's defensive escorts. Implementation of wolf packs had been difficult in World War I owing to the limitations of available radios. In the interwar years, Germany had developed ultra-high frequency transmitters which it was hoped would make their radio communication unjammable, while the Enigma cipher machine

was believed to have made communications secure. Dönitz also adopted and claimed credit for Wilhelm Marschall

's 1922 idea of attacking convoys using surface or very near surface night attacks. This tactic had the added advantage of making a submarine undetectable by sonar.

At the time, many — including Erich Raeder

— felt such talk marked Dönitz as a weakling. Dönitz was alone among senior naval officers, including some former submariners, in believing in a new submarine war on trade. He and Raeder constantly argued over funding priorities within the Navy, while at the same time competing with Hitler's friends, such as Hermann Göring

, who received greater attention at this time.

Since the surface strength of the Kriegsmarine was much less than that of the British Royal Navy

, Raeder believed any war with Britain in the near future would doom it to uselessness, once remarking all the Germans could hope to do was die valiantly. Raeder based his hopes on war being delayed until the German Navy's extensive "Z Plan"

, which would have expanded Germany's surface fleet to where it could effectively contend with the Royal Navy, was implemented. The "Z Plan", however, was not scheduled to be completed until 1945.

Dönitz, in contrast, had no such fatalism and set about intensely training his crews in the new tactics. The marked inferiority of the German surface fleet left submarine warfare as Germany's only naval option once war broke out.

On 28 January 1939, Dönitz was promoted to Commodore

(Kommodore) and Commander of Submarines (Führer der Unterseeboote).

, Britain and France declared war on Germany, and World War II

began. The Kriegsmarine was caught unprepared for war, having anticipated that the war's outbreak would be in 1945, not 1939. The Z Plan was tailored for this assumption, calling for a balanced fleet with a greatly increased number of surface capital ships, including several aircraft carriers. At the time the war began, Dönitz's force included only 57 U-boats, many of them short-range, and only 22 oceangoing Type VII

s. He made do with what he had, while being harassed by Raeder and with Hitler calling on him to dedicate boats to military actions against the British fleet directly. These operations had mixed success; the aircraft carrier

and battleship

were sunk, and battleships damaged and sunk, at a cost of some U-boats, diminishing the small quantity available even further. Together with surface raiders, merchant shipping lines were also attacked by U-boats.

(Konteradmiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, BdU); on 1 September the following year, he was made a Vice Admiral

(Vizeadmiral).

By 1941, the delivery of new Type VIIs had improved to the point where operations were having a real effect on the British wartime economy. Although production of merchant ships shot up in response, improved torpedoes, better U-boats, and much better operational planning led to increasing numbers of "kills". On 11 December 1941, following Adolf Hitler

By 1941, the delivery of new Type VIIs had improved to the point where operations were having a real effect on the British wartime economy. Although production of merchant ships shot up in response, improved torpedoes, better U-boats, and much better operational planning led to increasing numbers of "kills". On 11 December 1941, following Adolf Hitler

's declaration of war on the United States

, Dönitz immediately planned for implementation of Operation Drumbeat (Unternehmen Paukenschlag). This targeted shipping along the East Coast of the United States

. Carried out the next month, with only nine U-boats (all the larger Type IX

), it had dramatic and far-reaching results. The U.S. Navy

was entirely unprepared for antisubmarine warfare, despite having had two years of British experience to draw from, and committed every imaginable mistake. Shipping losses, which had appeared to be coming under control as the Royal Navy

and Royal Canadian Navy

gradually adapted to the new challenge, skyrocketed.

On at least two occasions, Allied

success against U-boat operations led Dönitz to investigate possible reasons. Among those considered were espionage and Allied interception and decoding

of German Navy communications (the naval version of the Enigma cipher machine). Both investigations into communications security came to the conclusion espionage was more likely, or else the Allied successes had been accidental. Nevertheless, Dönitz ordered his U-boat fleet to use an improved version of the Enigma machine (one with four or five rotors, which was even more secure), the M4, for communications within the fleet, on 1 February 1942. The German Navy (Kriegsmarine) was the only branch to use the improved version; the rest of the German armed forces

(Wehrmacht

) continued to use their then-current three-rotor versions of the Enigma machine. The new system was termed "Triton" ("Shark" to the Allies). For a time, this change in encryption between submarines caused considerable difficulty for Allied codebreakers

; it took ten months before Shark traffic could be read (see also Ultra codebreaking and Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

).

By the end of 1942, the production of Type VII U-boats had increased to the point where Dönitz was finally able to conduct mass attacks by groups of submarines, a tactic he called "Rudel" (group or pack) and became known as "wolfpack" in English. Allied shipping losses shot up tremendously, and there was serious concern for a while about the state of British fuel supplies.

During 1943, the war in the Atlantic

turned against the Germans, but Dönitz continued to push for increased U-boat construction and entertained the notion that further technological developments would tip the war once more in Germany's favour while briefing the Führer. At the end of the war, the German submarine fleet was by far the most advanced in the world, and late-war examples, such as the Type XXI U-boat, served as models for Soviet

and American construction after the war. These, the Schnorchel

(snorkel) and Type XXI

boats, appeared late in the war because of Dönitz's personal indifference, at times even hostility, to new technology he perceived as disruptive for the production process. His opposition to the larger Type IX was not unique; Admiral Thomas C. Hart

, who commanded the United States Asiatic Fleet

in the Philippines

at the outbreak of the Pacific War

, opposed fleet boats as "too luxurious".

Dönitz was deeply involved in the daily operations of his boats, often contacting them up to seventy times a day with questions such as their position, fuel supply, and other "minutiae

". This incessant questioning hastened the compromise of his ciphers, by giving the Allies more messages to work with. Furthermore, replies from the boats enabled the Allies to use direction finding

(HF/DF, called "Huff-Duff

") to locate a U-boat using its radio, track it, and attack it (often with aircraft able to sink it with impunity).

Dönitz wore on his uniform both the special grade of the U-Boat War Badge with diamonds, and his U-Boat War badge from World War I, along with his World War I Iron Cross 1st Class with World War II clasp.

On 30 January 1943, Dönitz replaced Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine) and Grand Admiral

On 30 January 1943, Dönitz replaced Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine) and Grand Admiral

(Großadmiral) of the Naval High Command

(Oberkommando der Marine

). His deputy, Eberhard Godt

, took over the operational command of the U-boat force It was Dönitz who was able to convince Hitler not to scrap the remaining ships of the surface fleet. Despite hoping to continue to use them as a fleet in being

, the Kriegsmarine continued losing what few capital ships it had. In September, the battleship

Tirpitz

was put out of action for months

by a British midget submarine

, and was sunk two months later by RAF bombers. In December, he ordered the battleship

Scharnhorst

(under Konteradmiral

Erich Bey

) to attack Soviet-bound convoys

, having considered her success in the early years of the war with sister ship Gneisenau, but she was sunk in the resulting encounter

with superior British forces led by the battleship

In the final days of the war

In the final days of the war

, after Hitler had installed himself in the Führerbunker

beneath the Reich Chancellery

gardens in Berlin, Hermann Göring

was considered the obvious successor to Hitler, followed by Heinrich Himmler

. Göring, however, had infuriated Hitler by radioing Hitler in Berlin asking for permission to assume leadership of the Reich. Himmler also tried to seize power himself by entering into negotiations with Count Folke Bernadotte

. On 28 April, the BBC reported that Himmler had offered surrender to the western Allies and that the offer had been declined.

In his last will and testament

, dated 29 April, Hitler surprisingly named Dönitz his successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State

), with the title of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The same document named Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels

as Head of Government

with the title of Reichskanzler (Chancellor

). Further, Hitler expelled both Göring and Himmler from the party.

Rather than designate one person to succeed him as Führer, Hitler reverted to the old arrangement in the Weimar Constitution

. Hitler believed the leaders of the German Army (Heer

), Air Force (Luftwaffe

), and SS (Schutzstaffel

) had betrayed him. Since the German Navy had been too small to affect the war in a major way, its commander, Dönitz, became the only possible successor more or less by default.

However, on 1 May—the day after Hitler's death—Goebbels committed suicide. Dönitz thus became the sole representative of the crumbling German Reich. He appointed Finance Minister Count Ludwig Schwerin von Krosigk as "Leading Minister" (Krosigk had declined to accept the title of Chancellor) and they attempted to form a government.

That night, Dönitz made a nationwide radio address in which he spoke of Hitler's "hero's death" and announced that the war would continue "to save Germany from destruction by the advancing Bolshevik enemy." However, Dönitz knew even then that Germany's position was untenable and that the Wehrmacht was no longer capable of offering meaningful resistance. During his brief period in office, Dönitz devoted most of his efforts to ensuring the loyalty of the German armed forces and trying to ensure German troops would surrender to the British or Americans and not the Soviets. He feared vengeful Soviet reprisals against Nazi party members and high-ranking officers like himself, and hoped to strike a deal with the western Allies. In the end, the tactics of Dönitz were somewhat successful in that they enabled about 1.8 million German soldiers to avoid Soviet capture. However, this came at a high cost in bloodshed.

near the Danish

border, where Dönitz's headquarters were located, along with Mürwik

. Accordingly his administration was referred to as the Flensburg government

. The following is Dönitz's description of his new government:

Late on 1 May, Himmler attempted to make a place for himself in the Flensburg government. The following is Dönitz's description of his showdown with Himmler:

On 4 May, German forces in the Netherlands

, Denmark, and northwestern Germany under Dönitz's command surrendered to Field Marshal

Bernard Montgomery

at the Lüneburg Heath

, just southeast of Hamburg

, signalling the end of World War II in northwestern Europe.

A day later, Dönitz sent Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg

A day later, Dönitz sent Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg

, his successor as the commander in chief of the German Navy, to U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

's headquarters in Rheims, France

, to negotiate a surrender to the Allies. The Chief of Staff

of OKW, Colonel-General (Generaloberst) Alfred Jodl

, arrived a day later. Dönitz had instructed them to draw out the negotiations for as long as possible so that German troops and refugees could surrender to the Western Powers. However, when Eisenhower let it be known he would not tolerate the Germans' stalling, Dönitz authorised Jodl to sign the instrument of unconditional surrender at 1:30 a.m. on the morning of May 7. Just over an hour later, Jodl signed the documents. The surrender documents included the phrase, "All forces under German control to cease active operations at 23:01 hours Central European Time on 8 May 1945." At Stalin's insistence, on 8 May, shortly before midnight, General Field Marshal (Generalfeldmarschall

) Wilhelm Keitel

repeated the signing in Berlin at Marshal

Georgiy Zhukov's headquarters, with General Carl Spaatz

of the USAAF as Eisenhower's representative. At the time specified, World War II in Europe ended

.

On 23 May, the Dönitz government

was dissolved when its members were arrested by the Allied Control Commission at Flensburg.

in stopping a scorched earth

policy dictated by Hitler and is also noted as saying, "in comparison to Hitler we are all pip-squeaks. Anyone who believes he can do better than the Führer is stupid."

There are several antisemitic statements on the part of Dönitz known to historians. When Sweden

closed its international waters to Germany, he blamed this action on their fear and dependence on "international Jewish capital." In August 1944, he declared, "I would rather eat dirt than see my grandchildren grow up in the filthy, poisonous atmosphere of Jewry."

On German Heroes' Day (12 March) 1944, Dönitz declared that, without Adolf Hitler, Germany would be beset by the "poison of Jewry", and the country destroyed for lack of National Socialism

, which, as Dönitz declared, gave defiance of an uncompromising ideology. At the Nuremberg Trials

, Dönitz claimed the statement about the "poison of Jewry" was regarding "the endurance, the power to endure, of the people, as it was composed, could be better preserved than if there were Jewish elements in the nation." Initially he claimed, "I could imagine that it would be very difficult for the population in the towns to hold out under the strain of heavy bombing attacks if such an influence was allowed to work."

Author Eric Zillmer argues, that from an ideological standpoint, Dönitz was anti-Marxist and anti-Semitic. Later, during the Nuremberg Trials, Dönitz claimed to know nothing about the extermination of Jews

and declared that nobody among "his men" thought about violence against Jews.

Dönitz told Leon Goldensohn

, an American psychiatrist at Nuremberg

, "I never had any idea of the goings-on as far as Jews were concerned. Hitler said each man should take care of his business, and mine was U-boats and the navy". To Goldensohn, Dönitz also spoke of his support for Admiral Bernhard Rogge

, who was of Jewish descent, when the Nazi Party began to persecute the admiral.

on three counts: (1) conspiracy to commit crimes against peace

, war crime

s, and crimes against humanity; (2) planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression

; and (3) crimes against the laws of war

. Dönitz was found not guilty on count (1) of the indictment, but guilty on counts (2) and (3).

During the trial, Gustave Gilbert

, an American Army psychologist, was allowed to examine the Nazi leaders who were tried at Nuremberg for war crimes. Among other tests, a German version of the Wechsler-Bellevue

IQ test was administered. Dönitz scored 138, the third highest among the Nazi leaders tested.

Dönitz disputed the propriety of his trial at Nuremberg, commenting on count (2) that "One of the 'accusations' that made me guilty during this trial was that I met and planned the course of the war with Hitler; now I ask them in heaven’s name, how could an admiral do otherwise with his country's head of state in a time of war?" Numerous (over 100) senior Allied officers also sent letters to Dönitz conveying their disappointment over the fairness and verdict of his trial.

At the trial Dönitz was charged with:

Among the war-crimes charges, Dönitz was accused of waging unrestricted submarine warfare

for issuing War Order No. 154

in 1939, and another similar order after the Laconia incident

in 1942, not to rescue survivors from ships attacked by submarine. By issuing these two orders, he was found guilty of causing Germany to be in breach of the Second London Naval Treaty

of 1936. However, as evidence of similar conduct by the Allies was presented at his trial, and with the help of his lawyer Otto Kranzbühler

, his sentence was not assessed on the grounds of this breach of international law.

On the specific war crimes charge of ordering unrestricted submarine warfare

, Dönitz was found "[not] guilty for his conduct of submarine warfare against British armed merchant ships", because they were often armed and equipped with radios which they used to notify the Admiralty of attack but the judges found that "Dönitz is charged with waging unrestricted submarine warfare contrary to the Naval Protocol of 1936 to which Germany acceded, and which reaffirmed the rules of submarine warfare laid down in the London Naval Agreement of 1930... The order of Dönitz to sink neutral ships without warning when found within these zones was, therefore, in the opinion of the Tribunal, violation of the Protocol... The orders, then, prove Dönitz is guilty of a violation of the Protocol... the sentence of Dönitz is not assessed on the ground of his breaches of the international law of submarine warfare."

His sentence on unrestricted submarine warfare was not assessed, because of similar actions by the Allies: in particular, the British Admiralty

on 8 May 1940 had ordered that all vessels in the Skagerrak

should be sunk on sight; and Admiral Chester Nimitz

, wartime commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet

, stated that the U.S. Navy had waged unrestricted submarine warfare in the Pacific from the day the U.S. entered the war. Thus although Dönitz's was found guilty of waging unrestricted submarine warfare against unarmed neutral shipping by ordering all ships in designated areas in international waters to be sunk without warning, no additional prison time was added to his sentence for this crime.

Dönitz was imprisoned for 10 years in Spandau Prison

in what was then West Berlin

.

Dönitz was released on 1 October 1956, and he retired to the small village of Aumühle

Dönitz was released on 1 October 1956, and he retired to the small village of Aumühle

in Schleswig-Holstein

in northern West Germany

. There he worked on two books. His memoirs, Zehn Jahre, Zwanzig Tage (Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days), appeared in Germany in 1958 and became available in an English translation the following year. This book recounted Dönitz's experiences as U-boat commander (10 years) and President of Germany (20 days). In it, Dönitz explains the Nazi regime as a product of its time, but argues he was not a politician and thus not morally responsible for much of the regime's crimes. He likewise criticizes dictatorship as a fundamentally flawed form of government and blames it for much of the Nazi era's failings.

Admiral Dönitz's second book, Mein wechselvolles Leben (My Ever-Changing Life) is less known, perhaps because it deals with the events of his life before 1934. This book was first published in 1968, and a new edition was released in 1998 with the revised title Mein soldatisches Leben (My Life as a Soldier).

Late in his life, Dönitz made every attempt to answer correspondence and autograph postcards for others. Dönitz was unrepentant regarding his role in World War II since he firmly believed that no one will respect anyone who compromises with his belief or duty towards his nation in any way, whether his betrayal was small or big. Of this conviction, Dönitz writes (commenting on Himmler's peace negotiations):

Dönitz lived out the rest of his life in relative obscurity in Aumühle, occasionally corresponding with American collectors of German Naval history, and died there of a heart attack on 24 December

1980. As the last German officer with the rank of Grand Admiral

, he was honoured by many former servicemen and foreign naval officers who came to pay their respects at his funeral on 6 January 1981. However, he had received only the pension pay of a captain

because the West German government ruled all of his advances in rank after that had been because of Hitler. He was buried in Waldfriedhof Cemetery in Aumühle without military honors, and soldiers were not allowed to wear uniforms to the funeral. However a number of German naval officers disobeyed this order and were joined by members of the Royal Navy

, such as the senior chaplain the Rev Dr John Cameron, in full dress uniform. Also in attendance were over one hundred holders of the Knight's Cross

.

, when his boat was sunk in the North Atlantic with all hands. After this loss, the older brother, Klaus

, was allowed to leave combat duty and began studying to be a naval doctor. Klaus was killed on 13 May 1944 while taking part in an action against his orders. Klaus persuaded his friends to let him go on the torpedo boat

S-141 for a raid on off the coast of England on his twenty-fourth birthday. The boat was destroyed and Klaus died, though six others were rescued. In 1937 Karl Dönitz's daughter Ursula married the U-boat commander and Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

recipient Günther Hessler

.

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

naval commander during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. He started his career in the German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine

The Imperial German Navy was the German Navy created at the time of the formation of the German Empire. It existed between 1871 and 1919, growing out of the small Prussian Navy and Norddeutsche Bundesmarine, which primarily had the mission of coastal defense. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded...

, or "Imperial Navy") during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. In 1918, while he was in command of , the submarine

Submarine

A submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner. While in a prisoner of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

camp, he formulated what he later called Rudeltaktik ("pack tactic", commonly called "wolfpack"). At the start of World War II, he was the senior submarine officer in the German Navy. In January 1943, Dönitz achieved the rank of Großadmiral (Grand Admiral

Grand Admiral

Grand admiral is a historic naval rank, generally being the highest such rank present in any particular country. Its most notable use was in Germany — the German word is Großadmiral.-France:...

) and replaced Grand Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder was a naval leader in Germany before and during World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank—that of Großadmiral — in 1939, becoming the first person to hold that rank since Alfred von Tirpitz...

as Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine). On 30 April 1945, after the death of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

and in accordance with Hitler's last will and testament

Last will and testament of Adolf Hitler

The last will and testament of Adolf Hitler was dictated by Hitler to his secretary Traudl Junge in his Berlin Führerbunker on April 29, 1945, the day he and Eva Braun married. They committed suicide the next day , two days before the surrender of Berlin to the Soviets on May 2, and just over a...

, Dönitz was named Hitler's successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

), with the title of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. On 7 May 1945, he ordered Alfred Jodl

Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl was a German military commander, attaining the position of Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command during World War II, acting as deputy to Wilhelm Keitel...

to sign the German instruments of surrender in Rheims, France. Dönitz remained as head of the Flensburg Government

Flensburg government

The Flensburg Government , also known as the Flensburg Cabinet and the Dönitz Government , was the short-lived administration that attempted to rule the Third Reich during most of May 1945 at the end of World War II in Europe...

, as it became known, until it was dissolved by the Allied powers on 23 May.

Early life and career

Dönitz was born in GrünauGrünau (Berlin)

Grünau is a German locality within the Berlin borough of Treptow-Köpenick. Until 2001 it was part of the former borough of Köpenick.-History:...

in Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, Germany

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

to Anna Beyer and Emil Dönitz, an engineer. Karl had an older brother, Friedrich.

In 1910, Dönitz enlisted in the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine

The Imperial German Navy was the German Navy created at the time of the formation of the German Empire. It existed between 1871 and 1919, growing out of the small Prussian Navy and Norddeutsche Bundesmarine, which primarily had the mission of coastal defense. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded...

). He became a sea-cadet

Cadet

A cadet is a trainee to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. The term comes from the term "cadet" for younger sons of a noble family.- Military context :...

(Seekadett) on 4 April. On 15 April 1911, he became a midshipman

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer cadet, or a commissioned officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Kenya...

(Fähnrich zur See), the rank given to those who had served for one year as officer's apprentice and had passed their first examination.

On 27 September 1913, Dönitz was commissioned as a Acting Sub-Lieutenant (Leutnant zur See). When World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

began, he served in the light cruiser

Light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small- or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck...

in the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

. In August 1914, Breslau and the battlecruiser were sold to the Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

navy; the ships were renamed the Midilli and the Yavuz Sultan Selim, respectively. They began operating out of Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

(now Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

), under Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon was a German and Ottoman admiral in World War I who commanded the Kaiserliche Marine's Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war...

, engaging Russian

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

forces in the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

. On 22 March 1916, Dönitz was promoted to Navy First Lieutenant

First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a military rank and, in some forces, an appointment.The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations , but the majority of cases it is common for it to be sub-divided into a senior and junior rank...

(Oberleutnant zur See). When Midilli put into dock for repairs, he was temporarily assigned as airfield commander at the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

. From there, he requested a transfer to the submarine forces, which became effective in October 1916. He served as watch officer on , and from February 1918 onward as commander of . On 5 September 1918, he became commander of , operating in the Mediterranean. On 4 October, this boat was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner on the island of Malta.

Inter-war period

The war ended in 1918, but Dönitz remained in a British camp near SheffieldSheffield

Sheffield is a city and metropolitan borough of South Yorkshire, England. Its name derives from the River Sheaf, which runs through the city. Historically a part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, and with some of its southern suburbs annexed from Derbyshire, the city has grown from its largely...

as a prisoner of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

until his release in July 1919. He returned to Germany in 1920.

During the interwar period

Interwar period

Interwar period can refer to any period between two wars. The Interbellum is understood to be the period between the end of the Great War or First World War and the beginning of the Second World War in Europe....

, Dönitz continued his naval career in the naval arm of the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

's Armed Forces (Reichswehr

Reichswehr

The Reichswehr formed the military organisation of Germany from 1919 until 1935, when it was renamed the Wehrmacht ....

). On 10 January 1921, he became a Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

(Kapitänleutnant) in the new German Navy (Vorläufige Reichsmarine). Dönitz commanded torpedo boat

Torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval vessel designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs rammed enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes, and later designs launched self-propelled Whitehead torpedoes. They were created to counter battleships and other large, slow and...

s by 1928, becoming a Lieutenant-Commander (Korvettenkapitän) on 1 November of that same year.

On 1 September 1933, Dönitz became a full Commander

Commander

Commander is a naval rank which is also sometimes used as a military title depending on the individual customs of a given military service. Commander is also used as a rank or title in some organizations outside of the armed forces, particularly in police and law enforcement.-Commander as a naval...

(Fregattenkapitän) and, in 1934, was put in command of the cruiser Emden

German cruiser Emden

The German light cruiser Emden was the only ship of its class. The third cruiser to bear the name Emden was the first new warship built in Germany after World War I....

. Emden was the ship on which cadets and midshipmen took a year-long world cruise in preparation for a future officer's commission.

On 1 September 1935, Dönitz was promoted to Captain

Captain (naval)

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The NATO rank code is OF-5, equivalent to an army full colonel....

(Kapitän zur See). He was placed in command of the 1st U-boat Flotilla Weddigen, which included , , and .

During 1935, the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

's Navy, the Reichsmarine

Reichsmarine

The Reichsmarine was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the Reichswehr, existing from 1918 to 1935...

, was replaced by the Navy of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, the Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine

The Kriegsmarine was the name of the German Navy during the Nazi regime . It superseded the Kaiserliche Marine of World War I and the post-war Reichsmarine. The Kriegsmarine was one of three official branches of the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany.The Kriegsmarine grew rapidly...

.

Throughout 1935 and 1936, Dönitz had misgivings regarding submarines due to German overestimation of the capabilities of British ASDIC. In reality, ASDIC could detect only one submarine in ten during exercises. In the words of Alan Hotham, British Director of Naval Intelligence

Naval Intelligence Division

The Naval Intelligence Division was the intelligence arm of the British Admiralty before the establishment of a unified Defence Staff in 1965. It dealt with matters concerning British naval plans, with the collection of naval intelligence...

, ASDIC was a "huge bluff".

German doctrine at the time, based on the work of American Naval Captain Alfred Mahan and shared by all major navies, called for submarines to be integrated with surface fleets and employed against enemy warships. By November 1937, Dönitz became convinced that a major campaign against merchant shipping was practical and began pressing for the conversion of the German fleet almost entirely to U-boats. He advocated a strategy of attacking only merchant ships, targets relatively safe to attack. He pointed out that destroying Britain's fleet of oil tankers would starve the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

of supplies needed to run its ships, which would be just as effective as sinking them. He thought a German fleet of 300 of the newer Type VII U-boats could knock Britain out of the war.

Dönitz revived the World War I idea of grouping several submarines together into a "wolfpack" to overwhelm a merchant convoy's defensive escorts. Implementation of wolf packs had been difficult in World War I owing to the limitations of available radios. In the interwar years, Germany had developed ultra-high frequency transmitters which it was hoped would make their radio communication unjammable, while the Enigma cipher machine

Enigma machine

An Enigma machine is any of a family of related electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines used for the encryption and decryption of secret messages. Enigma was invented by German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I...

was believed to have made communications secure. Dönitz also adopted and claimed credit for Wilhelm Marschall

Wilhelm Marschall

Wilhelm Marschall was a German admiral during World War II. He was also a recipient of the Pour le Mérite which he received as commander of the German U-boat during World War I...

's 1922 idea of attacking convoys using surface or very near surface night attacks. This tactic had the added advantage of making a submarine undetectable by sonar.

At the time, many — including Erich Raeder

Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder was a naval leader in Germany before and during World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank—that of Großadmiral — in 1939, becoming the first person to hold that rank since Alfred von Tirpitz...

— felt such talk marked Dönitz as a weakling. Dönitz was alone among senior naval officers, including some former submariners, in believing in a new submarine war on trade. He and Raeder constantly argued over funding priorities within the Navy, while at the same time competing with Hitler's friends, such as Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

, who received greater attention at this time.

Since the surface strength of the Kriegsmarine was much less than that of the British Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

, Raeder believed any war with Britain in the near future would doom it to uselessness, once remarking all the Germans could hope to do was die valiantly. Raeder based his hopes on war being delayed until the German Navy's extensive "Z Plan"

Plan Z

Plan Z was the name given to the planned re-equipment and expansion of the Nazi German Navy ordered by Adolf Hitler on January 27, 1939...

, which would have expanded Germany's surface fleet to where it could effectively contend with the Royal Navy, was implemented. The "Z Plan", however, was not scheduled to be completed until 1945.

Dönitz, in contrast, had no such fatalism and set about intensely training his crews in the new tactics. The marked inferiority of the German surface fleet left submarine warfare as Germany's only naval option once war broke out.

On 28 January 1939, Dönitz was promoted to Commodore

Commodore (rank)

Commodore is a military rank used in many navies that is superior to a navy captain, but below a rear admiral. Non-English-speaking nations often use the rank of flotilla admiral or counter admiral as an equivalent .It is often regarded as a one-star rank with a NATO code of OF-6, but is not always...

(Kommodore) and Commander of Submarines (Führer der Unterseeboote).

World War II

In September 1939, Germany invaded PolandInvasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

, Britain and France declared war on Germany, and World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

began. The Kriegsmarine was caught unprepared for war, having anticipated that the war's outbreak would be in 1945, not 1939. The Z Plan was tailored for this assumption, calling for a balanced fleet with a greatly increased number of surface capital ships, including several aircraft carriers. At the time the war began, Dönitz's force included only 57 U-boats, many of them short-range, and only 22 oceangoing Type VII

German Type VII submarine

Type VII U-boats were the most common type of German World War II U-boat. The Type VII was based on earlier German submarine designs going back to the World War I Type UB III, designed through the Dutch dummy company Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw den Haag which was set up by Germany after...

s. He made do with what he had, while being harassed by Raeder and with Hitler calling on him to dedicate boats to military actions against the British fleet directly. These operations had mixed success; the aircraft carrier

Aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship designed with a primary mission of deploying and recovering aircraft, acting as a seagoing airbase. Aircraft carriers thus allow a naval force to project air power worldwide without having to depend on local bases for staging aircraft operations...

and battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

were sunk, and battleships damaged and sunk, at a cost of some U-boats, diminishing the small quantity available even further. Together with surface raiders, merchant shipping lines were also attacked by U-boats.

Commander of the submarine fleet

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a Rear AdmiralRear Admiral

Rear admiral is a naval commissioned officer rank above that of a commodore and captain, and below that of a vice admiral. It is generally regarded as the lowest of the "admiral" ranks, which are also sometimes referred to as "flag officers" or "flag ranks"...

(Konteradmiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, BdU); on 1 September the following year, he was made a Vice Admiral

Vice Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval rank of a three-star flag officer, which is equivalent to lieutenant general in the other uniformed services. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral...

(Vizeadmiral).

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

's declaration of war on the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Dönitz immediately planned for implementation of Operation Drumbeat (Unternehmen Paukenschlag). This targeted shipping along the East Coast of the United States

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, refers to the easternmost coastal states in the United States, which touch the Atlantic Ocean and stretch up to Canada. The term includes the U.S...

. Carried out the next month, with only nine U-boats (all the larger Type IX

German Type IX submarine

The Type IX U-boat was designed by Germany in 1935 and 1936 as a large ocean-going submarine for sustained operations far from the home support facilities. Type IX boats were briefly used for patrols off the eastern United States in an attempt to disrupt the stream of troops and supplies bound for...

), it had dramatic and far-reaching results. The U.S. Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

was entirely unprepared for antisubmarine warfare, despite having had two years of British experience to draw from, and committed every imaginable mistake. Shipping losses, which had appeared to be coming under control as the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

and Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy

The history of the Royal Canadian Navy goes back to 1910, when the naval force was created as the Naval Service of Canada and renamed a year later by King George V. The Royal Canadian Navy is one of the three environmental commands of the Canadian Forces...

gradually adapted to the new challenge, skyrocketed.

On at least two occasions, Allied

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

success against U-boat operations led Dönitz to investigate possible reasons. Among those considered were espionage and Allied interception and decoding

Decoding methods

In communication theory and coding theory, decoding is the process of translating received messages into codewords of a given code. There have been many common methods of mapping messages to codewords...

of German Navy communications (the naval version of the Enigma cipher machine). Both investigations into communications security came to the conclusion espionage was more likely, or else the Allied successes had been accidental. Nevertheless, Dönitz ordered his U-boat fleet to use an improved version of the Enigma machine (one with four or five rotors, which was even more secure), the M4, for communications within the fleet, on 1 February 1942. The German Navy (Kriegsmarine) was the only branch to use the improved version; the rest of the German armed forces

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

(Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

) continued to use their then-current three-rotor versions of the Enigma machine. The new system was termed "Triton" ("Shark" to the Allies). For a time, this change in encryption between submarines caused considerable difficulty for Allied codebreakers

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key...

; it took ten months before Shark traffic could be read (see also Ultra codebreaking and Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

Cryptanalysis of the Enigma enabled the western Allies in World War II to read substantial amounts of secret Morse-coded radio communications of the Axis powers that had been enciphered using Enigma machines. This yielded military intelligence which, along with that from other decrypted Axis radio...

).

By the end of 1942, the production of Type VII U-boats had increased to the point where Dönitz was finally able to conduct mass attacks by groups of submarines, a tactic he called "Rudel" (group or pack) and became known as "wolfpack" in English. Allied shipping losses shot up tremendously, and there was serious concern for a while about the state of British fuel supplies.

During 1943, the war in the Atlantic

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

turned against the Germans, but Dönitz continued to push for increased U-boat construction and entertained the notion that further technological developments would tip the war once more in Germany's favour while briefing the Führer. At the end of the war, the German submarine fleet was by far the most advanced in the world, and late-war examples, such as the Type XXI U-boat, served as models for Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and American construction after the war. These, the Schnorchel

Submarine snorkel

A submarine snorkel is a device which allows a submarine to operate submerged while still taking in air from above the surface. Navy personnel often refer to it as the snort.-History:...

(snorkel) and Type XXI

German Type XXI submarine

Type XXI U-boats, also known as "Elektroboote", were the first submarines designed to operate primarily submerged, rather than as surface ships that could submerge as a means to escape detection or launch an attack.-Description:...

boats, appeared late in the war because of Dönitz's personal indifference, at times even hostility, to new technology he perceived as disruptive for the production process. His opposition to the larger Type IX was not unique; Admiral Thomas C. Hart

Thomas C. Hart

Thomas Charles Hart was an admiral of the United States Navy, whose service extended from the Spanish-American War through World War II. Following his retirement from the Navy, he served briefly as a United States Senator from Connecticut.-Life and career:Hart was born in Genesee County, Michigan...

, who commanded the United States Asiatic Fleet

United States Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was part of the U.S. Navy. Preceding the World War II era, until 1942, the fleet protected the Philippines.Originally the Asiatic Squadron, it was upgraded to fleet status in 1902. In 1907, the fleet became the First Squadron of the Pacific Fleet. However, on 28...

in the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

at the outbreak of the Pacific War

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

, opposed fleet boats as "too luxurious".

Dönitz was deeply involved in the daily operations of his boats, often contacting them up to seventy times a day with questions such as their position, fuel supply, and other "minutiae

Minutiae

Minutiae are, in everyday English, minor or incidental details.In biometrics and forensic science, minutiae are major features of a fingerprint, using which comparisons of one print with another can be made...

". This incessant questioning hastened the compromise of his ciphers, by giving the Allies more messages to work with. Furthermore, replies from the boats enabled the Allies to use direction finding

Direction finding

Direction finding refers to the establishment of the direction from which a received signal was transmitted. This can refer to radio or other forms of wireless communication...

(HF/DF, called "Huff-Duff

Huff-Duff

High-frequency direction finding, usually known by its abbreviation HF/DF is the common name for a type of radio direction finding employed especially during the two World Wars....

") to locate a U-boat using its radio, track it, and attack it (often with aircraft able to sink it with impunity).

Dönitz wore on his uniform both the special grade of the U-Boat War Badge with diamonds, and his U-Boat War badge from World War I, along with his World War I Iron Cross 1st Class with World War II clasp.

Commander-in-chief and Grand Admiral

Grand Admiral

Grand admiral is a historic naval rank, generally being the highest such rank present in any particular country. Its most notable use was in Germany — the German word is Großadmiral.-France:...

(Großadmiral) of the Naval High Command

Oberkommando der Marine

The Oberkommando der Marine was Nazi Germany's Naval High Command and the highest administrative and command authority of the Kriegsmarine. It was officially formed from the Marineleitung of the Reichswehr on 11 January 1936. In 1937 it was combined with the newly formed Seekriegsleitung...

(Oberkommando der Marine

Oberkommando der Marine

The Oberkommando der Marine was Nazi Germany's Naval High Command and the highest administrative and command authority of the Kriegsmarine. It was officially formed from the Marineleitung of the Reichswehr on 11 January 1936. In 1937 it was combined with the newly formed Seekriegsleitung...

). His deputy, Eberhard Godt

Eberhard Godt

Eberhard Godt was a German naval officer who served in both World War I and World War II, rising eventually to command the Kriegsmarine's U-boat operations. He joined the Kaiserliche Marine in 1918 and resigned after the ceasefire in November of that year...

, took over the operational command of the U-boat force It was Dönitz who was able to convince Hitler not to scrap the remaining ships of the surface fleet. Despite hoping to continue to use them as a fleet in being

Fleet in being

In naval warfare, a fleet in being is a naval force that extends a controlling influence without ever leaving port. Were the fleet to leave port and face the enemy, it might lose in battle and no longer influence the enemy's actions, but while it remains safely in port the enemy is forced to...

, the Kriegsmarine continued losing what few capital ships it had. In September, the battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

Tirpitz

German battleship Tirpitz

Tirpitz was the second of two s built for the German Kriegsmarine during World War II. Named after Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the architect of the Imperial Navy, the ship was laid down at the Kriegsmarinewerft in Wilhelmshaven in November 1936 and launched two and a half years later in April...

was put out of action for months

Operation Source

Operation Source was a series of attacks to neutralise the heavy German warships – Tirpitz, Scharnhorst and Lutzow – based in northern Norway, using X-class midget submarines....

by a British midget submarine

Midget submarine

A midget submarine is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to 6 or 8, with little or no on-board living accommodation...

, and was sunk two months later by RAF bombers. In December, he ordered the battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

Scharnhorst

German battleship Scharnhorst

Scharnhorst was a German capital ship, alternatively described as a battleship and battlecruiser, of the German Kriegsmarine. She was the lead ship of her class, which included one other ship, Gneisenau. The ship was built at the Kriegsmarinewerft dockyard in Wilhelmshaven; she was laid down on 15...

(under Konteradmiral

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a naval commissioned officer rank above that of a commodore and captain, and below that of a vice admiral. It is generally regarded as the lowest of the "admiral" ranks, which are also sometimes referred to as "flag officers" or "flag ranks"...

Erich Bey

Erich Bey

Erich Bey was a German naval officer who most notably served as a commander of the Kriegsmarine's destroyer forces and commanded the battleship Scharnhorst in the Battle of North Cape on 26 December 1943, during which the German ship was sunk. He was killed during that action. Bey was also a...

) to attack Soviet-bound convoys

Arctic convoys of World War II

The Arctic convoys of World War II travelled from the United Kingdom and North America to the northern ports of the Soviet Union—Arkhangelsk and Murmansk. There were 78 convoys between August 1941 and May 1945...

, having considered her success in the early years of the war with sister ship Gneisenau, but she was sunk in the resulting encounter

Battle of North Cape

The Battle of the North Cape was a Second World War naval battle which occurred on 26 December 1943, as part of the Arctic Campaign. The German battlecruiser , on an operation to attack Arctic Convoys of war materiel from the Western Allies to the USSR, was brought to battle and sunk by superior...

with superior British forces led by the battleship

Hitler's successor

End of World War II in Europe

The final battles of the European Theatre of World War II as well as the German surrender to the Western Allies and the Soviet Union took place in late April and early May 1945.-Timeline of surrenders and deaths:...

, after Hitler had installed himself in the Führerbunker

Führerbunker

The Führerbunker was located beneath Hitler's New Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex which was constructed in two major phases, one part in 1936 and the other in 1943...

beneath the Reich Chancellery

Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany in the period of the German Reich from 1871 to 1945...

gardens in Berlin, Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

was considered the obvious successor to Hitler, followed by Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

. Göring, however, had infuriated Hitler by radioing Hitler in Berlin asking for permission to assume leadership of the Reich. Himmler also tried to seize power himself by entering into negotiations with Count Folke Bernadotte

Folke Bernadotte

Folke Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg was a Swedish diplomat and nobleman noted for his negotiation of the release of about 31,000 prisoners from German concentration camps during World War II, including 450 Danish Jews from Theresienstadt released on 14 April 1945...

. On 28 April, the BBC reported that Himmler had offered surrender to the western Allies and that the offer had been declined.

In his last will and testament

Last will and testament of Adolf Hitler

The last will and testament of Adolf Hitler was dictated by Hitler to his secretary Traudl Junge in his Berlin Führerbunker on April 29, 1945, the day he and Eva Braun married. They committed suicide the next day , two days before the surrender of Berlin to the Soviets on May 2, and just over a...

, dated 29 April, Hitler surprisingly named Dönitz his successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

), with the title of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The same document named Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

as Head of Government

Head of government

Head of government is the chief officer of the executive branch of a government, often presiding over a cabinet. In a parliamentary system, the head of government is often styled prime minister, chief minister, premier, etc...

with the title of Reichskanzler (Chancellor

Chancellor of Germany

The Chancellor of Germany is, under the German 1949 constitution, the head of government of Germany...

). Further, Hitler expelled both Göring and Himmler from the party.

Rather than designate one person to succeed him as Führer, Hitler reverted to the old arrangement in the Weimar Constitution

Weimar constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich , usually known as the Weimar Constitution was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic...

. Hitler believed the leaders of the German Army (Heer

Heer

Heer is German for "army". Generally, its use as "army" is not restricted to any particular country, so "das britische Heer" would mean "the British army".However, more specifically it can refer to:*An army of Germany:...

), Air Force (Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

), and SS (Schutzstaffel

Schutzstaffel

The Schutzstaffel |Sig runes]]) was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Built upon the Nazi ideology, the SS under Heinrich Himmler's command was responsible for many of the crimes against humanity during World War II...

) had betrayed him. Since the German Navy had been too small to affect the war in a major way, its commander, Dönitz, became the only possible successor more or less by default.

However, on 1 May—the day after Hitler's death—Goebbels committed suicide. Dönitz thus became the sole representative of the crumbling German Reich. He appointed Finance Minister Count Ludwig Schwerin von Krosigk as "Leading Minister" (Krosigk had declined to accept the title of Chancellor) and they attempted to form a government.

That night, Dönitz made a nationwide radio address in which he spoke of Hitler's "hero's death" and announced that the war would continue "to save Germany from destruction by the advancing Bolshevik enemy." However, Dönitz knew even then that Germany's position was untenable and that the Wehrmacht was no longer capable of offering meaningful resistance. During his brief period in office, Dönitz devoted most of his efforts to ensuring the loyalty of the German armed forces and trying to ensure German troops would surrender to the British or Americans and not the Soviets. He feared vengeful Soviet reprisals against Nazi party members and high-ranking officers like himself, and hoped to strike a deal with the western Allies. In the end, the tactics of Dönitz were somewhat successful in that they enabled about 1.8 million German soldiers to avoid Soviet capture. However, this came at a high cost in bloodshed.

Flensburg government

The rapidly advancing Allied forces limited the Dönitz government's jurisdiction to an area around FlensburgFlensburg

Flensburg is an independent town in the north of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Flensburg is the centre of the region of Southern Schleswig...

near the Danish

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

border, where Dönitz's headquarters were located, along with Mürwik

Naval Academy Mürwik

The Naval Academy at Mürwik is the main training establishment for all German Navy officers.It is located at Mürwik which is a part of Germany's most northern city, Flensburg. Built on a small hill directly by the coast, it overlooks the Flensburg Fjord...

. Accordingly his administration was referred to as the Flensburg government

Flensburg government

The Flensburg Government , also known as the Flensburg Cabinet and the Dönitz Government , was the short-lived administration that attempted to rule the Third Reich during most of May 1945 at the end of World War II in Europe...

. The following is Dönitz's description of his new government:

Late on 1 May, Himmler attempted to make a place for himself in the Flensburg government. The following is Dönitz's description of his showdown with Himmler:

On 4 May, German forces in the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, Denmark, and northwestern Germany under Dönitz's command surrendered to Field Marshal

Field Marshal

Field Marshal is a military rank. Traditionally, it is the highest military rank in an army.-Etymology:The origin of the rank of field marshal dates to the early Middle Ages, originally meaning the keeper of the king's horses , from the time of the early Frankish kings.-Usage and hierarchical...

Bernard Montgomery

Bernard Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, KG, GCB, DSO, PC , nicknamed "Monty" and the "Spartan General" was a British Army officer. He saw action in the First World War, when he was seriously wounded, and during the Second World War he commanded the 8th Army from...

at the Lüneburg Heath

Lüneburg Heath

The Lüneburg Heath is a large area of heath, geest and woodland in northeastern part of the state of Lower Saxony in northern Germany. It forms part of the hinterland for the cities of Hamburg, Hanover, and Bremen and is named after the town of Lüneburg. Most of the area is a nature reserve...

, just southeast of Hamburg

Hamburg

-History:The first historic name for the city was, according to Claudius Ptolemy's reports, Treva.But the city takes its modern name, Hamburg, from the first permanent building on the site, a castle whose construction was ordered by the Emperor Charlemagne in AD 808...

, signalling the end of World War II in northwestern Europe.

Hans-Georg von Friedeburg

Hans-Georg von Friedeburg was the deputy commander of the U-Boat Forces of Nazi Germany and the last Commanding Admiral of the Kriegsmarine....

, his successor as the commander in chief of the German Navy, to U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

's headquarters in Rheims, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, to negotiate a surrender to the Allies. The Chief of Staff

Chief of Staff

The title, chief of staff, identifies the leader of a complex organization, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a Principal Staff Officer , who is the coordinator of the supporting staff or a primary aide to an important individual, such as a president.In general, a chief of...

of OKW, Colonel-General (Generaloberst) Alfred Jodl

Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl was a German military commander, attaining the position of Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command during World War II, acting as deputy to Wilhelm Keitel...

, arrived a day later. Dönitz had instructed them to draw out the negotiations for as long as possible so that German troops and refugees could surrender to the Western Powers. However, when Eisenhower let it be known he would not tolerate the Germans' stalling, Dönitz authorised Jodl to sign the instrument of unconditional surrender at 1:30 a.m. on the morning of May 7. Just over an hour later, Jodl signed the documents. The surrender documents included the phrase, "All forces under German control to cease active operations at 23:01 hours Central European Time on 8 May 1945." At Stalin's insistence, on 8 May, shortly before midnight, General Field Marshal (Generalfeldmarschall

Generalfeldmarschall