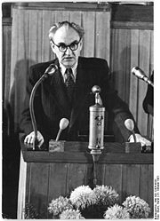

Heinrich Rau

Encyclopedia

Heinrich Gottlob "Heiner" Rau (2 April 1899 – 23 March 1961) was a German communist politician during the time of the Weimar Republic

; subsequently, during the Spanish Civil War

, a leading member of the International Brigades

and after World War II

an East German

statesman.

Rau grew up in a suburb of Stuttgart

, where he early became active in the socialist youth. After military service in World War I

, he participated in the German Revolution

of 1918-19. From 1920 onward, he was a leading agricultural politician of the Communist Party of Germany

(KPD). This ended in 1933, when Adolf Hitler

came to power. Shortly afterwards Rau was thrown in jail for two years. As an enemy of the Nazi regime in Germany he was kept imprisoned, in total, for more than half of the time of Hitler's reign. After his first imprisonment, he emigrated in 1935 to the Soviet Union

(USSR). From there, he went in 1937 to Spain

, where he participated in the Spanish Civil War as a leader of one of the International Brigades. In 1939, he was arrested in France, from where the Vichy

regime delivered him to Nazi Germany in 1942. The last two-year location of his imprisonments was, since March 1943, the Mauthausen Concentration Camp. There he participated in conspirative prisoner activities, which led to a camp uprising in the final days before the end of World War II in Europe.

After the war, he played an important role in East Germany. Before the establishment of an East German state he was chairman of the German Economic Commission

, precursor of the East German government. Subsequently he became chairman of the National Planning Commission of East Germany and a deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers. He was a leading economic politician and diplomat of East Germany and led various ministries at different times. In East Germany's ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany

(SED), he was a member of the party's CC Politburo

.

, now a part of Stuttgart

, in the German Kingdom of Württemberg

, the son of a peasant who later became a factory worker. He grew up in the adjacent city of Zuffenhausen

, now also a part of Stuttgart. After finishing school in spring 1913, he started work as a press operator in a shoe factory. In November 1913 he changed his employer and moved to the Bosch factory works

in Feuerbach. There he completed his training as metal presser and remained, interrupted by war service 1917-1918 and the following German Revolution

of 1918-1919 until autumn 1920.

Since 1913 Rau also was active in the labour movement and joined in that year the metal workers' union (Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband) and a social democratic youth group in Zuffenhausen. During the following years, which saw the beginning of World War I, Rau's youth group, whose leader he became in 1916, was significantly influenced by the left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

(SPD), which considered the war a conflict between "imperialist

powers". A few local members of a far left SPD group, among them Edwin Hoernle and Albert Schreiner, who later became well-known members of the Spartacus League (Spartakusbund), visited the youth group in Zuffenhausen and gave lectures. In 1916, Rau joined the Spartacists as well and became a co-founder of their youth organisation. In accordance with the politics of the Spartacists, in 1917 he joined the left-wing Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

(USPD) and in 1919 the Communist Party of Germany

(KPD), which had been founded mainly by members of the Spartacus League.

In spring 1917, Rau, by this time an elected trade union official in his firm, participated in the attempt to organise a strike against the war. His action led to a reprimand from his employer, and may have hastened his conscription into the army in August 1917. In the army he was trained in the Zuffenhausen-garrisoned Infantry Regiment 126 and deployed to the Western Front

as member of a machine gun company. In September 1918 a shell splinter penetrated his lungs. In the following weeks, he was treated in military hospitals in Weimar

and in Stuttgart's neighbouring town Ludwigsburg

. While in Ludwigsburg, Rau managed to get leave at short notice on 8 November 1918 and joined the in those days developing revolution in Stuttgart.

left Stuttgart on 9 November, shortly after a revolutionary crowd had stormed his residence, the Wilhelm Palais

and flown a red flag above the building. On the very same day the demonstrators were also able to seize some of Stuttgart's barracks, where parts of the garrisons openly joined them. Rau took active part in the events in Stuttgart's streets on this and the following day.

These happenings were a first cumulation of a civil commotion, that had started a few days earlier, by the end of October 1918, with large strikes and demonstrations. On 4 November 1918, a first workers' council

under the leadership of the 23-year-old Spartacist Fritz Rück had been established in Stuttgart. During the following days and weeks more spontaneously elected worker and soldier councils were formed, and took over a large part of Württemberg. Rau was elected leader of the military police in his home city of Zuffenhausen, a part of Stuttgart's urban area.

As early as 9 November, about 150 councillors gathered for a two-day meeting in Stuttgart. A majority of the councillors entrusted the leaders of the political parties SPD and USPD, who had been invited to the meeting, with the establishment of a provisional government in Württemberg

. In this quickly established first government, which for the present shared power with the councils, the Spartacist Albert Schreiner, then chairman of a soldier council, initially assumed the key position of Minister of War. He resigned however already a few days later, after disputes about the future course of the government. While the Spartacists considered aims similar to those of the last year's October Revolution

in Russia as an ideal, parts of the other USPD members and the SPD followers considered such conditions more as a deterrence. They favoured social improvements in a parliamentary democracy and aimed for early elections in Württemberg.

During the ensuing months the communists tried repeatedly to seize power in Stuttgart and other cities in Württemberg by armed rebellion, accompanied by large-scale strikes. During such an attempt, at the beginning of April 1919, the time, when in Munich

the Bavarian Soviet Republic

was formally proclaimed, a general strike took place in the Stuttgart area and 16 people died in gunfights, in which even cannons were deployed. In this time, Rau used his position as chief of the military police in Zuffenhausen to shut down companies that remained operational despite the strike, but when the plan failed Rau was removed from office by the government.

Rau resumed his employment at Bosch in Feuerbach. During another general strike in several Württemberg cities, from 28 August to 4 September 1920, he led the strike committee in his firm, which resulted in his dismissal.

was Edwin Hoernle, a former visitor of Rau's youth group in Zuffenhausen and since then Rau's long-standing friend. In former years, Hoernle had also become a kind of influential teacher for Rau. Then he made his voluminous library available to Rau and talked with him about the upcoming questions during Rau's self-study.

The most outstanding ideological authority of the movement in Stuttgart, during the time of Rau's political involvement there, was however Clara Zetkin

, a founding member of the Second International

, about whom Friedrich Engels

once had written, that he liked her very much, while emperor Wilhelm II is said to have referred to her as the "worst witch in Germany". She had also been living in a Stuttgart suburb since 1891 and since then, been gathering a circle of Württemberg Marxists

around her, among them Rau's friend Edwin Hoernle, who had been editing with her the magazine Die Gleichheit

. Her house, built in 1903 in Sillenbuch (now a part of Stuttgart), had become a meeting place of leading national and local left-wing and communist activists. It was also visited by international communist leaders like Lenin, who stayed there overnight in 1907. In 1920, when Zetkin was elected to the Reichstag

in Berlin

, Hoernle and Rau moved to Berlin as well.

of the KPD in Berlin. Between 1921 and 1930 he lectured at the Land

and Federal schools of the KPD, and edited a few left-wing agricultural journals.

Initially, Edwin Hoernle, with whom Rau had come from Stuttgart, was the head of the Central Committee's Division for Agriculture. After Hoernle had been elected to the Executive Committee of the Comintern

(ECCI) in November 1922, Rau succeeded him in this position the following year. Afterwards, he also became a leading member of various national and international left wing farmer and peasant organisations. From 1923 onward, he was a member of the Secretariat of the International Committee of the Agricultural and Forest Workers and beginning in 1924 of the executive committee of the Reich Peasant Federation (Reichsbauernbund). In 1930 this was followed with a membership on the International Peasants' Council in Moscow

and in 1931 he became an office member of the European Peasant Committee. From 1928 to 1933 he was also member of the Preußischer Landtag

, the Prussian federal state parliament. There he joined the committee on agricultural affairs of the parliament and became its chairman.

, for "preparations to commit high treason" by the People's Court of Germany. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment. After his release from custody, he emigrated to the USSR

in August 1935, via Czechoslovakia

and became a deputy chairman of the International Agrarian Institute in Moscow.

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

and following the formation of the International Brigades

, Rau attended a school for military commanders in Ryazan

(USSR), and subsequently went to Spain

. After his arrival in April 1937, he joined the XI International Brigade

and participated in the civil war as political commissar

, beginning in May 1937, then as chief of staff and finally commander of the brigade, until March 1938, when he was injured.

Although the brigade achieved some temporary successes during these months, Francisco Franco

's troops were already on the road to victory. Rau's brigade saw combat in the battles of Brunete

, Belchite

, Teruel

and the Aragon Offensive

, where Rau was wounded.

When Rau took charge of the XI Brigade, he was supposedly at odds with his predecessor, Richard Staimer, the future son-in-law of KPD leader Wilhelm Pieck

. This was the time of the Great Purge

which had its echos in Spain, and it could be perilous to have powerful enemies. André Marty

, the Stalinist chief commissar of the International Brigades based at Albacete

, was also the executor of the Great Purge in Spain. Following Rau's injury, Marty managed to imprison him under a pretext for a brief time. A report, written in Moscow in 1940, described Rau as a "political criminal", who had had contact with the Spanish anarchists

and members of the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM

), which was demonized as "Trotskyist"

. These were serious allegations in this time, when accusations of Trotskyism frequently led to a death sentence if the accused was within reach of the authorities.

However, it seems that Rau also had influential friends. He was released from prison and expelled from Spain. He moved to France in May 1938. There, he was in charge of the emergency committee of the German and Austrian Spain fighters and member of the KPD country leadership in Paris

until 1939. At the beginning of 1939 Rau crossed the border to Spain again and subsequently led, together with Ludwig Renn

, the remainders of the XI Brigade, which, together with other remaining international units – now combined in the "Agrupación Internacional" – fought on Spain's northern border after the fall of Barcelona, protecting the stream of refugees escaping to France. Thus they enabled the escape of perhaps some 470,000 civilians and soldiers.

Rau was arrested by the French authorities in September 1939 and sent to Camp Vernet

, the internment centre in France, and in November 1941 to a secret prison in Castres

. In June 1942, he was handed over to the Gestapo

by the Vichy

regime and sat until March 1943 in the Gestapo prison in the Prince Albrecht Street. Afterwards he was sent to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, where he remained until May 1945, when he participated in the camp rebellion as one of the organisers of a secret military camp organisation.

for some weeks and helped the KPD representatives in the city gather liberated political prisoners from Germany. He left Vienna in July 1945, when he led a car convoy with 120 former Mauthausen inmates to the Soviet occupied part of Berlin.

In September 1945, the Soviets appointed Rau a member of the provisional chairmanship of the Province of Brandenburg

with the title of a vice-president and responsibility for food, agriculture and forests. Rau succeeded Edwin Hoernle, who had held this position since the end of June and became now chairman of the central administration for agriculture and forests in the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ). In his new position, Rau was member of the commission for the execution of the land reform

in the province. In spring 1946 he became the responsible president for economy and transport in Brandenburg. In this capacity, he was since June 1946 chairman of the new established sequester commission in the province. 1946 was also the year of the forced merger of eastern KPD and eastern SPD into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

(SED). Thus Rau became a member of the SED. A remarkable 1946 event in Brandenburg were in November elections, which preceded an official status change from a province to a federal state in the following year. Afterwards, from 1946 until 1948, Rau was state parliament delegate and Minister for Economic Planning of Brandenburg.

(Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission or DWK), which became in this time the centralised administration organisation for the Soviet Occupation Zone and the predecessor of the future East German government. This organisation existed in a time of great difficult challenges from different sides. An especially notable and momentous event in this time was the currency reform of 1948. On 20 June 1948 the western German zones introduced a new currency, leaving the eastern zone alone with the old common currency. In order to avoid inflation, the DWK under Rau's leadership was forced to follow quickly with its own reform and issued an own currency too. In doing so, the DWK also instrumentalized the currency reform to redistribute capital by using highly different exchange rates for private and state-run companies. The following quarrel, which of the two new currencies should be used in Berlin, was the starting of the Berlin Blockade

by the USSR and the western airborne supply of West Berlin

.

Under Rau's leadership the DWK, still under supervision of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany

(German: Sowjetische Militäradministration in Deutschland or SMAD), quickly developed more and more into a partner of the SMAD with its own conceptions and intentions. This policy was also endorsed by the Soviet chief diplomat in Germany, Vladimir Semyonov, the future Chief Commissar of the USSR in Germany, who already in January 1948 correspondingly stated, that SMAD orders, (which accompanied DWK orders,) should have merely the purpose to back the authority of the German orders. One of Rau's aims during the meetings with the SMAD was, to come to agreements, which also obliged the Soviet side, including subordinate Soviet authorities, who still engaged in wild confiscations for reparation purposes. An important success in this direction was a half-year plan for the economic development in the second half of 1948, which was accepted by the SMAD in May 1948. It was followed by a likewise accepted two-year plan for 1949 and 1950.

The biggest obstacle to the plan's implementation soon proved to be the Berlin Blockade by the USSR, which was followed by a western counter-blockade of the Soviet occupation zone. As there were long-established economic ties between the western zone and the eastern, which was highly dependent on supplies from the West, the blockade was more damaging to the East. The West Berlin SPD newspaper Sozialdemokrat reported in April 1949, how Rau clearly criticized the blockade in a meeting of SED apparatchiks and there is reason to believe that he did the same in the meetings with the SMAD. According to the paper, Rau spoke of a "bad speculation" regarding the undervaluation of the dependence on western supplies, stating that the "broadminded Soviet help" turned out as insufficient and hinting that the blockade would soon be lifted. Finally the Berlin Blockade was lifted on 12 May 1949.

The DWK's increasingly centralised administration resulted in a substantial increase in its staffing level, which grew from about 5000 employees in mid-1948 to 10,000 by the beginning of 1949. In March 1949, Rau, like the representative of a state, signed a first treaty with a foreign state, a trade agreement with Poland.

Likewise in 1949, the ruling SED implemented traditional leadership structures of communist parties and Rau became a member of the newly established Central Committee of the SED and candidate member of its Politburo; in 1950, a full member of the Politburo as well as deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers

.

In 1949–1950, Rau was Minister for Planning of the GDR and in 1950–1952 chairman of the National Planning Commission. In this position, as the key figure of the economic development, Rau came into conflict with SED General Secretary

Walter Ulbricht

. In the face of an imminent economic collapse, Rau blamed the "Bureau Ulbricht" for the wrong policy. In response East Germany's old president Wilhelm Pieck

renewed the old accusation of Trotskyism

against Rau. In a later letter to Pieck of 28 November 1951 Rau protested at the manner in which the Secretariat usurped the Politburo by censoring his speech on economic affairs.

In 1952–1953, Rau led the newly established Coordination Centre for Industry and Traffic at the East German Council of Ministers.

After the death of Stalin in March 1953, the new collective Soviet leadership started to advocate a New Course

. In this connection Moscow favored replacing East Germany's Stalinist party leader Walter Ulbricht and made enquiries about Rau as a potential candidate. Thereupon the leading SED party ideologist Rudolf Herrnstadt

, a candidate member of the Poliburo, drew with support and assistance by Heinrich Rau a concept for such a New Course in East Germany. However, the workers' uprising, which was suppressed by the Soviet army on 17 June led to a backlash. Three weeks later, during a session of the then eight person Politburo

( plus six candidate members ) on 8 July 1953, Rau recommended to replace Ulbricht, while Rau's Spanish Civil War fellow, Stasi

chief Wilhelm Zaisser

, who in Spain had been known as 'General Gómez', accused Ulbricht of having perverted the party. The majority was against Ulbricht. His only supporters were Hermann Matern and Erich Honecker

. But at the moment there was no candidate to replace Ulbricht immediately. Suggested were first Rudolf Herrnstadt and then Heinrich Rau, but both were hesitant, thus a decision was postponed. The very next day after the meeting Ulbricht went by plane to Moscow and the Soviet leadership, who in part also feared, that deposing Ulbricht might be construed as a sign of weakness, secured Ulbricht's position now. Subsequently five members and candidate members of the Politburo lost their positions.

Concentrating on his tasks in the SED leadership and as a minister, Rau – despite occasional internal criticism – widely avoided an appearance of disharmony with Ulbricht present at this time, at least in public. In 1954, Rau received in the Order of Merit for the Fatherland (Vaterländischer Verdienstorden) in gold. Later, Ulbricht stated in a 1964 interview about the "introduction of socialism" in the GDR, that only three people were heavily involved in the economic development during that time: "namely Heinrich Rau, Bruno Leuschner and me. Others were not consulted!"

In 1953–1955 Rau led the new established Ministry for Machine Construction, which combined the responsibilities of three other until then existing ministries. His deputy in this ministry was Erich Apel, who would later, in the early 1960s, become an initiator and architect of an economic reform, which became known as the New Economic System

(NES).

This reform in the 1960s partially had already a forerunner reform in the middle of the 1950s and the economic historian Jörg Roesler considers the NES in the 1960s as a continuation of this foregoing reform. The origin of the reform in the 1950s was a scientific study, commissioned by Rau's ministry in 1953, to assess the need for greater economic efficiency in the factories. The subsequent results from this study promised enhanced economic efficiency by shifting more responsibility from the National Planning Commission to the enterprises themselves. Thenceforward, already in spring 1954, Rau advocated such a planning reform, while planning boss Bruno Leuschner quite consistently opposed it. In August 1954, Rau's ministry sent a concept for such a reform to Leuschner's State Planning Commission. Eventually this reform got under way, after Ulbricht, perhaps under the influence of his new personal economic adviser Wolfgang Berger, had approved such a policy at the end of 1954 too. Subsequently the reform accelerated until 1956. It found however its early end in the generally aggravated political atmosphere in 1957. Unrests in other Eastern Bloc countries during the previous year 1956, in particular in Hungary, had awoken the desire for more central control again. The subsequent unsatisfying economic development, however, during the following years eventually led in the 1960s to the concept of a new planning reform, the NES.

. In this time both German states still saw German reunification as their own aim, but both envisaging different political systems. The West German position was that they, as the only freely elected government, had an exclusive mandate

for the entire German people. In consequence of this, the GDR's official diplomatic relationships with other states were narrowed to the states of the Eastern Bloc. Practically no other states recognized the GDR. As a result Rau's ministry established numerous new "trade missions" in other states, which served as a kind of surrogate for nonexistent embassies. It was a corollary, that Rau, in addition to his responsibility for the export-oriented industry, also chaired the Foreign Policy Commission of the SED Politburo (Außenpolitische Kommission beim Politbüro or APK) since 1955, in this period the actual decision-making body for foreign affairs, and visited other states in different parts of the world in this capacity. Among the visited states were, beside the core states of the Soviet Bloc

, also then Eastern Bloc riparian states, like China

and Albania

and leading states of the crystallizing Non-Aligned Movement

like India

and Yugoslavia

(after the Bandung Conference). Between 1955 and 1957 he visited, as part of a diplomatic advertisement campaign in the Arab world, various Arabic states, among them repeatedly Egypt

. One of his last deals, which he closed as minister, was a trade agreement with Cuba

, signed by Cuba's minister Ernesto 'Che' Guevara

, on 17 December 1960 in East Berlin

.

Rau, Rau, in poor health during his final years, died of a heart attack in East Berlin, in March 1961.

Rau was married twice and had three sons and a daughter. Like the other members of the Politburo, he lived until 1960 in a hermetically protected area of East Berlin's district Pankow

and moved in 1960 to the Waldsiedlung

near Wandlitz

. In Pankow he had lived in Majakowskiring

. In 1963, Rau's widow Elisabeth moved to this street again.

When the prominent West German SPD politician and future President of Germany

Johannes Rau

visited an SPD rally in the East German city of Erfurt

during the time of German reunification

, he was introduced as "Prime Minister 'Heinrich Rau. Thereupon Johannes Rau ironically commented on this lapse by observing that Heinrich Rau was communist and he was not.

children in Egypt. ( Lumumba was the first Prime Minister of the Congo

. His family moved into exile in Egypt after or shortly before his violent death. )

Others

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

; subsequently, during the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, a leading member of the International Brigades

International Brigades

The International Brigades were military units made up of volunteers from different countries, who traveled to Spain to defend the Second Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939....

and after World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

an East German

German Democratic Republic

The German Democratic Republic , informally called East Germany by West Germany and other countries, was a socialist state established in 1949 in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany, including East Berlin of the Allied-occupied capital city...

statesman.

Rau grew up in a suburb of Stuttgart

Stuttgart

Stuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

, where he early became active in the socialist youth. After military service in World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, he participated in the German Revolution

German Revolution

The German Revolution was the politically-driven civil conflict in Germany at the end of World War I, which resulted in the replacement of Germany's imperial government with a republic...

of 1918-19. From 1920 onward, he was a leading agricultural politician of the Communist Party of Germany

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

(KPD). This ended in 1933, when Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

came to power. Shortly afterwards Rau was thrown in jail for two years. As an enemy of the Nazi regime in Germany he was kept imprisoned, in total, for more than half of the time of Hitler's reign. After his first imprisonment, he emigrated in 1935 to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

(USSR). From there, he went in 1937 to Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, where he participated in the Spanish Civil War as a leader of one of the International Brigades. In 1939, he was arrested in France, from where the Vichy

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

regime delivered him to Nazi Germany in 1942. The last two-year location of his imprisonments was, since March 1943, the Mauthausen Concentration Camp. There he participated in conspirative prisoner activities, which led to a camp uprising in the final days before the end of World War II in Europe.

After the war, he played an important role in East Germany. Before the establishment of an East German state he was chairman of the German Economic Commission

German Economic Commission

The German Economic Commission was the top administrative body in the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany prior to the creation of the German Democratic Republic ....

, precursor of the East German government. Subsequently he became chairman of the National Planning Commission of East Germany and a deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers. He was a leading economic politician and diplomat of East Germany and led various ministries at different times. In East Germany's ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany

Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany was the governing party of the German Democratic Republic from its formation on 7 October 1949 until the elections of March 1990. The SED was a communist political party with a Marxist-Leninist ideology...

(SED), he was a member of the party's CC Politburo

Politburo

Politburo , literally "Political Bureau [of the Central Committee]," is the executive committee for a number of communist political parties.-Marxist-Leninist states:...

.

Early years until World War I

Rau was born in FeuerbachStuttgart-Feuerbach

Feuerbach is a district of the city of Stuttgart. Its name is derived from the small river of the same name that flows from the neighbouring district of Botnang through Feuerbach...

, now a part of Stuttgart

Stuttgart

Stuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

, in the German Kingdom of Württemberg

Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg was a state that existed from 1806 to 1918, located in present-day Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which came into existence in 1495...

, the son of a peasant who later became a factory worker. He grew up in the adjacent city of Zuffenhausen

Zuffenhausen

Zuffenhausen is an urban district in the northern suburbs of Stuttgart, the capital of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It consists mainly of the formerly independent city of Zuffenhausen. The Zuffenhausen district has an area of 1,200 hectares and 35,568 inhabitants .The oldest surviving...

, now also a part of Stuttgart. After finishing school in spring 1913, he started work as a press operator in a shoe factory. In November 1913 he changed his employer and moved to the Bosch factory works

Robert Bosch GmbH

Robert Bosch GmbH is a multinational engineering and electronics company headquartered in Gerlingen, near Stuttgart, Germany. It is the world's largest supplier of automotive components...

in Feuerbach. There he completed his training as metal presser and remained, interrupted by war service 1917-1918 and the following German Revolution

German Revolution

The German Revolution was the politically-driven civil conflict in Germany at the end of World War I, which resulted in the replacement of Germany's imperial government with a republic...

of 1918-1919 until autumn 1920.

Since 1913 Rau also was active in the labour movement and joined in that year the metal workers' union (Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband) and a social democratic youth group in Zuffenhausen. During the following years, which saw the beginning of World War I, Rau's youth group, whose leader he became in 1916, was significantly influenced by the left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

(SPD), which considered the war a conflict between "imperialist

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

powers". A few local members of a far left SPD group, among them Edwin Hoernle and Albert Schreiner, who later became well-known members of the Spartacus League (Spartakusbund), visited the youth group in Zuffenhausen and gave lectures. In 1916, Rau joined the Spartacists as well and became a co-founder of their youth organisation. In accordance with the politics of the Spartacists, in 1917 he joined the left-wing Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany was a short-lived political party in Germany during the Second Reich and the Weimar Republic. The organization was established in 1917 as the result of a split of left wing members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany...

(USPD) and in 1919 the Communist Party of Germany

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

(KPD), which had been founded mainly by members of the Spartacus League.

In spring 1917, Rau, by this time an elected trade union official in his firm, participated in the attempt to organise a strike against the war. His action led to a reprimand from his employer, and may have hastened his conscription into the army in August 1917. In the army he was trained in the Zuffenhausen-garrisoned Infantry Regiment 126 and deployed to the Western Front

Western Front

Western Front was a term used during the First and Second World Wars to describe the contested armed frontier between lands controlled by Germany to the east and the Allies to the west...

as member of a machine gun company. In September 1918 a shell splinter penetrated his lungs. In the following weeks, he was treated in military hospitals in Weimar

Weimar

Weimar is a city in Germany famous for its cultural heritage. It is located in the federal state of Thuringia , north of the Thüringer Wald, east of Erfurt, and southwest of Halle and Leipzig. Its current population is approximately 65,000. The oldest record of the city dates from the year 899...

and in Stuttgart's neighbouring town Ludwigsburg

Ludwigsburg

Ludwigsburg is a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, about north of Stuttgart city centre, near the river Neckar. It is the largest and primary city of the Ludwigsburg urban district with about 87,000 inhabitants...

. While in Ludwigsburg, Rau managed to get leave at short notice on 8 November 1918 and joined the in those days developing revolution in Stuttgart.

Revolution

The revolution in November 1918 led in Württemberg, like everywhere in Germany, to the end of the monarchy. King William IIWilliam II of Württemberg

William II was the fourth King of Württemberg, from 6 October 1891 until the abolition of the kingdom on 30 November 1918...

left Stuttgart on 9 November, shortly after a revolutionary crowd had stormed his residence, the Wilhelm Palais

Wilhelm Palais

The Wilhelmspalais is a Palais located on the Charlottenplatz in Stuttgart-Mitte. It was the living quarters of the last Württemberg King Wilhelm II. It was totally destroyed during World War II and between 1961 and 1965 reconstructed in modern style. Nowadays, the central library of the...

and flown a red flag above the building. On the very same day the demonstrators were also able to seize some of Stuttgart's barracks, where parts of the garrisons openly joined them. Rau took active part in the events in Stuttgart's streets on this and the following day.

These happenings were a first cumulation of a civil commotion, that had started a few days earlier, by the end of October 1918, with large strikes and demonstrations. On 4 November 1918, a first workers' council

Workers' council

A workers' council, or revolutionary councils, is the phenomenon where a single place of work or enterprise, such as a factory, school, or farm, is controlled collectively by the workers of that workplace, through the core principle of temporary and instantly revocable delegates.In a system with...

under the leadership of the 23-year-old Spartacist Fritz Rück had been established in Stuttgart. During the following days and weeks more spontaneously elected worker and soldier councils were formed, and took over a large part of Württemberg. Rau was elected leader of the military police in his home city of Zuffenhausen, a part of Stuttgart's urban area.

As early as 9 November, about 150 councillors gathered for a two-day meeting in Stuttgart. A majority of the councillors entrusted the leaders of the political parties SPD and USPD, who had been invited to the meeting, with the establishment of a provisional government in Württemberg

Württemberg

Württemberg , formerly known as Wirtemberg or Wurtemberg, is an area and a former state in southwestern Germany, including parts of the regions Swabia and Franconia....

. In this quickly established first government, which for the present shared power with the councils, the Spartacist Albert Schreiner, then chairman of a soldier council, initially assumed the key position of Minister of War. He resigned however already a few days later, after disputes about the future course of the government. While the Spartacists considered aims similar to those of the last year's October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

in Russia as an ideal, parts of the other USPD members and the SPD followers considered such conditions more as a deterrence. They favoured social improvements in a parliamentary democracy and aimed for early elections in Württemberg.

During the ensuing months the communists tried repeatedly to seize power in Stuttgart and other cities in Württemberg by armed rebellion, accompanied by large-scale strikes. During such an attempt, at the beginning of April 1919, the time, when in Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

the Bavarian Soviet Republic

Bavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Munich Soviet Republic was, as part of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the short-lived attempt to establish a socialist state in form of a council republic in the Free State of Bavaria. It sought independence from the also recently proclaimed...

was formally proclaimed, a general strike took place in the Stuttgart area and 16 people died in gunfights, in which even cannons were deployed. In this time, Rau used his position as chief of the military police in Zuffenhausen to shut down companies that remained operational despite the strike, but when the plan failed Rau was removed from office by the government.

Rau resumed his employment at Bosch in Feuerbach. During another general strike in several Württemberg cities, from 28 August to 4 September 1920, he led the strike committee in his firm, which resulted in his dismissal.

Influences

From 1919 until 1920 Rau was head of the local KPD group in Zuffenhausen, and chaired the KPD organisation in Stuttgart. In this time, the party leader in WürttembergFree People's State of Württemberg

The Free People's State of Württemberg was a state of Germany during the Weimar Republic in Württemberg.-1918 revolution:As Germany underwent violent revolution near the end of World War I, the Kingdom of Württemberg was transformed from a monarchy to a democratic republic without bloodshed; its...

was Edwin Hoernle, a former visitor of Rau's youth group in Zuffenhausen and since then Rau's long-standing friend. In former years, Hoernle had also become a kind of influential teacher for Rau. Then he made his voluminous library available to Rau and talked with him about the upcoming questions during Rau's self-study.

The most outstanding ideological authority of the movement in Stuttgart, during the time of Rau's political involvement there, was however Clara Zetkin

Clara Zetkin

Clara Zetkin was a German Marxist theorist, activist, and fighter for women's rights. In 1910, she organized the first International Women's Day....

, a founding member of the Second International

Second International

The Second International , the original Socialist International, was an organization of socialist and labour parties formed in Paris on July 14, 1889. At the Paris meeting delegations from 20 countries participated...

, about whom Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels was a German industrialist, social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. In 1845 he published The Condition of the Working Class in England, based on personal observations and research...

once had written, that he liked her very much, while emperor Wilhelm II is said to have referred to her as the "worst witch in Germany". She had also been living in a Stuttgart suburb since 1891 and since then, been gathering a circle of Württemberg Marxists

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

around her, among them Rau's friend Edwin Hoernle, who had been editing with her the magazine Die Gleichheit

Die Gleichheit

Die Gleichheit was a Social Democratic bimonthly magazine issued by the women's proletarian movement in Germany. It was published from 1890 to 1925, and was edited by Clara Zetkin from 1892 to 1917....

. Her house, built in 1903 in Sillenbuch (now a part of Stuttgart), had become a meeting place of leading national and local left-wing and communist activists. It was also visited by international communist leaders like Lenin, who stayed there overnight in 1907. In 1920, when Zetkin was elected to the Reichstag

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

in Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, Hoernle and Rau moved to Berlin as well.

Berlin

In November 1920 Rau became a secretary and full-time member of the agricultural division of the Central CommitteeCentral Committee

Central Committee was the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, whether ruling or non-ruling in the twentieth century and of the surviving, mostly Trotskyist, states in the early twenty first. In such party organizations the...

of the KPD in Berlin. Between 1921 and 1930 he lectured at the Land

States of Germany

Germany is made up of sixteen which are partly sovereign constituent states of the Federal Republic of Germany. Land literally translates as "country", and constitutionally speaking, they are constituent countries...

and Federal schools of the KPD, and edited a few left-wing agricultural journals.

Initially, Edwin Hoernle, with whom Rau had come from Stuttgart, was the head of the Central Committee's Division for Agriculture. After Hoernle had been elected to the Executive Committee of the Comintern

Executive Committee of the Communist International

The Executive Committee of the Communist International, commonly known by its acronym, ECCI, was the governing authority of the Comintern between the World Congresses of that body...

(ECCI) in November 1922, Rau succeeded him in this position the following year. Afterwards, he also became a leading member of various national and international left wing farmer and peasant organisations. From 1923 onward, he was a member of the Secretariat of the International Committee of the Agricultural and Forest Workers and beginning in 1924 of the executive committee of the Reich Peasant Federation (Reichsbauernbund). In 1930 this was followed with a membership on the International Peasants' Council in Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

and in 1931 he became an office member of the European Peasant Committee. From 1928 to 1933 he was also member of the Preußischer Landtag

Preußischer Landtag

Preußischer Landtag or Prussian Landtag was the Landtag of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was implemented in 1849 after the dissolution of the Prussian National Assembly, building on the tradition of the Prussian estates that had existed from the 14th century in various forms and states in Teutonic...

, the Prussian federal state parliament. There he joined the committee on agricultural affairs of the parliament and became its chairman.

Imprisonment, International Brigades, World War II

After Hitler's rise to power in January 1933 and the subsequent suppression of the KPD, Rau became a Central Committee's party instructor for southwest Germany and was active in building an underground party organisation there. On 23 May 1933 Rau was arrested and on 11 December 1934 convicted, together with Bernhard BästleinBernhard Bästlein

Bernhard Bästlein was a German Communist and resistance fighter against the Nazi régime. He was imprisoned very shortly after the Nazis seized power in 1933 and was imprisoned almost without interruption until his execution in 1944, by the Nazis...

, for "preparations to commit high treason" by the People's Court of Germany. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment. After his release from custody, he emigrated to the USSR

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

in August 1935, via Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

and became a deputy chairman of the International Agrarian Institute in Moscow.

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

and following the formation of the International Brigades

International Brigades

The International Brigades were military units made up of volunteers from different countries, who traveled to Spain to defend the Second Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939....

, Rau attended a school for military commanders in Ryazan

Ryazan

Ryazan is a city and the administrative center of Ryazan Oblast, Russia. It is located on the Oka River southeast of Moscow. Population: The strategic bomber base Dyagilevo is just west of the city, and the air base of Alexandrovo is to the southeast as is the Ryazan Turlatovo Airport...

(USSR), and subsequently went to Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

. After his arrival in April 1937, he joined the XI International Brigade

XI International Brigade

The XI International Brigade fought for the Spanish Second Republic in the Spanish Civil War.It would become especially renowned for providing desperately needed support in the darkest hours of the Republican defense of Madrid on 8 November 1936, when, with great losses, it helped repulse a major...

and participated in the civil war as political commissar

Political commissar

The political commissar is the supervisory political officer responsible for the political education and organisation, and loyalty to the government of the military...

, beginning in May 1937, then as chief of staff and finally commander of the brigade, until March 1938, when he was injured.

Although the brigade achieved some temporary successes during these months, Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco y Bahamonde was a Spanish general, dictator and head of state of Spain from October 1936 , and de facto regent of the nominally restored Kingdom of Spain from 1947 until his death in November, 1975...

's troops were already on the road to victory. Rau's brigade saw combat in the battles of Brunete

Battle of Brunete

The Battle of Brunete , fought 15 miles west of Madrid, was a Republican attempt to alleviate the pressure exerted by the Nationalists on the capital and on the north during the Spanish Civil War...

, Belchite

Battle of Belchite (1937)

Battle of Belchite was a group of military operations that took place in the Spanish Civil War between 24 August and 7 September 1937 nearby the town of Belchite, in Aragon.-Prelude:...

, Teruel

Battle of Teruel

The Battle of Teruel was fought in and around the city of Teruel during the Spanish Civil War in December 1937 – February 1938. The combatants fought the battle during the worst Spanish winter in twenty years. It was one of the bloodier actions of the war. The city changed hands several times,...

and the Aragon Offensive

Aragon Offensive

The Aragon Offensive was a Nationalist campaign during the Spanish Civil War, which began after the Battle of Teruel. The offensive began on March 7, 1938, and ended on April 19, 1938...

, where Rau was wounded.

When Rau took charge of the XI Brigade, he was supposedly at odds with his predecessor, Richard Staimer, the future son-in-law of KPD leader Wilhelm Pieck

Wilhelm Pieck

Friedrich Wilhelm Reinhold Pieck was a German politician and a Communist. In 1949, he became the first President of the German Democratic Republic, an office abolished upon his death. He was succeeded by Walter Ulbricht, who served as Chairman of the Council of States.-Biography:Pieck was born to...

. This was the time of the Great Purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

which had its echos in Spain, and it could be perilous to have powerful enemies. André Marty

André Marty

André Marty was a leading figure in the French Communist Party, the PCF, for nearly thirty years. He was also a member of the National Assembly, with some interruptions, from 1924 to 1955; Secretary of Comintern from 1935 to 1944; and Political Commissar of the International Brigades during the...

, the Stalinist chief commissar of the International Brigades based at Albacete

Albacete

Albacete is a city and municipality in southeastern Spain, 258 km southeast of Madrid, the capital of the province of Albacete in the autonomous community of Castile-La Mancha. The municipality had a population of c. 169,700 in 2009....

, was also the executor of the Great Purge in Spain. Following Rau's injury, Marty managed to imprison him under a pretext for a brief time. A report, written in Moscow in 1940, described Rau as a "political criminal", who had had contact with the Spanish anarchists

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

and members of the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM

Poum

Poum is a commune in the North Province of New Caledonia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. The town of Poum is located in the far northwest, located on the southern part of Banare Bay, with Mouac Island just offshore....

), which was demonized as "Trotskyist"

Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the theory of Marxism as advocated by Leon Trotsky. Trotsky considered himself an orthodox Marxist and Bolshevik-Leninist, arguing for the establishment of a vanguard party of the working-class...

. These were serious allegations in this time, when accusations of Trotskyism frequently led to a death sentence if the accused was within reach of the authorities.

However, it seems that Rau also had influential friends. He was released from prison and expelled from Spain. He moved to France in May 1938. There, he was in charge of the emergency committee of the German and Austrian Spain fighters and member of the KPD country leadership in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

until 1939. At the beginning of 1939 Rau crossed the border to Spain again and subsequently led, together with Ludwig Renn

Ludwig Renn

Ludwig Renn was a German writer. His real name was Arnold Friedrich Vieth von Golßenau.Born in Dresden into a Saxon noble family, he fought in World War I on the Western Front. He wrote the book Krieg on his experiences...

, the remainders of the XI Brigade, which, together with other remaining international units – now combined in the "Agrupación Internacional" – fought on Spain's northern border after the fall of Barcelona, protecting the stream of refugees escaping to France. Thus they enabled the escape of perhaps some 470,000 civilians and soldiers.

Rau was arrested by the French authorities in September 1939 and sent to Camp Vernet

Camp Vernet

Le Vernet Internment Camp, or Camp Vernet, was a concentration camp in Le Vernet, Ariège, near Pamiers, in the French Pyrenees. It was originally built in June 1918 to house French colonial troops serving in World War I but when hostilities ceased it was used to hold German and Austrian prisoners...

, the internment centre in France, and in November 1941 to a secret prison in Castres

Castres

Castres is a commune, and arrondissement capital in the Tarn department and Midi-Pyrénées region in southern France. It lies in the former French province of Languedoc....

. In June 1942, he was handed over to the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

by the Vichy

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

regime and sat until March 1943 in the Gestapo prison in the Prince Albrecht Street. Afterwards he was sent to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, where he remained until May 1945, when he participated in the camp rebellion as one of the organisers of a secret military camp organisation.

New start in Brandenburg

When Rau was free again, he went to ViennaVienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

for some weeks and helped the KPD representatives in the city gather liberated political prisoners from Germany. He left Vienna in July 1945, when he led a car convoy with 120 former Mauthausen inmates to the Soviet occupied part of Berlin.

In September 1945, the Soviets appointed Rau a member of the provisional chairmanship of the Province of Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Brandenburg is one of the sixteen federal-states of Germany. It lies in the east of the country and is one of the new federal states that were re-created in 1990 upon the reunification of the former West Germany and East Germany. The capital is Potsdam...

with the title of a vice-president and responsibility for food, agriculture and forests. Rau succeeded Edwin Hoernle, who had held this position since the end of June and became now chairman of the central administration for agriculture and forests in the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ). In his new position, Rau was member of the commission for the execution of the land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

in the province. In spring 1946 he became the responsible president for economy and transport in Brandenburg. In this capacity, he was since June 1946 chairman of the new established sequester commission in the province. 1946 was also the year of the forced merger of eastern KPD and eastern SPD into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany was the governing party of the German Democratic Republic from its formation on 7 October 1949 until the elections of March 1990. The SED was a communist political party with a Marxist-Leninist ideology...

(SED). Thus Rau became a member of the SED. A remarkable 1946 event in Brandenburg were in November elections, which preceded an official status change from a province to a federal state in the following year. Afterwards, from 1946 until 1948, Rau was state parliament delegate and Minister for Economic Planning of Brandenburg.

German Economic Commission

In March 1948 Rau became chairman of the German Economic CommissionGerman Economic Commission

The German Economic Commission was the top administrative body in the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany prior to the creation of the German Democratic Republic ....

(Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission or DWK), which became in this time the centralised administration organisation for the Soviet Occupation Zone and the predecessor of the future East German government. This organisation existed in a time of great difficult challenges from different sides. An especially notable and momentous event in this time was the currency reform of 1948. On 20 June 1948 the western German zones introduced a new currency, leaving the eastern zone alone with the old common currency. In order to avoid inflation, the DWK under Rau's leadership was forced to follow quickly with its own reform and issued an own currency too. In doing so, the DWK also instrumentalized the currency reform to redistribute capital by using highly different exchange rates for private and state-run companies. The following quarrel, which of the two new currencies should be used in Berlin, was the starting of the Berlin Blockade

Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War and the first resulting in casualties. During the multinational occupation of post-World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway and road access to the sectors of Berlin under Allied...

by the USSR and the western airborne supply of West Berlin

West Berlin

West Berlin was a political exclave that existed between 1949 and 1990. It comprised the western regions of Berlin, which were bordered by East Berlin and parts of East Germany. West Berlin consisted of the American, British, and French occupation sectors, which had been established in 1945...

.

Under Rau's leadership the DWK, still under supervision of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany

Soviet Military Administration in Germany

The Soviet Military Administration in Germany was the Soviet military government, headquartered in Berlin-Karlshorst, that directly ruled the Soviet occupation zone of Germany from the German surrender in May 1945 until after the establishment of the German Democratic Republic in October...

(German: Sowjetische Militäradministration in Deutschland or SMAD), quickly developed more and more into a partner of the SMAD with its own conceptions and intentions. This policy was also endorsed by the Soviet chief diplomat in Germany, Vladimir Semyonov, the future Chief Commissar of the USSR in Germany, who already in January 1948 correspondingly stated, that SMAD orders, (which accompanied DWK orders,) should have merely the purpose to back the authority of the German orders. One of Rau's aims during the meetings with the SMAD was, to come to agreements, which also obliged the Soviet side, including subordinate Soviet authorities, who still engaged in wild confiscations for reparation purposes. An important success in this direction was a half-year plan for the economic development in the second half of 1948, which was accepted by the SMAD in May 1948. It was followed by a likewise accepted two-year plan for 1949 and 1950.

The biggest obstacle to the plan's implementation soon proved to be the Berlin Blockade by the USSR, which was followed by a western counter-blockade of the Soviet occupation zone. As there were long-established economic ties between the western zone and the eastern, which was highly dependent on supplies from the West, the blockade was more damaging to the East. The West Berlin SPD newspaper Sozialdemokrat reported in April 1949, how Rau clearly criticized the blockade in a meeting of SED apparatchiks and there is reason to believe that he did the same in the meetings with the SMAD. According to the paper, Rau spoke of a "bad speculation" regarding the undervaluation of the dependence on western supplies, stating that the "broadminded Soviet help" turned out as insufficient and hinting that the blockade would soon be lifted. Finally the Berlin Blockade was lifted on 12 May 1949.

The DWK's increasingly centralised administration resulted in a substantial increase in its staffing level, which grew from about 5000 employees in mid-1948 to 10,000 by the beginning of 1949. In March 1949, Rau, like the representative of a state, signed a first treaty with a foreign state, a trade agreement with Poland.

Establishment and difficult first years of a new state

The time of Rau's German Economic Commission ended on 7 October 1949, when the East German state, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was proclaimed in a ceremony in the former Air Ministry Building in Berlin, until then the seat of Rau's organisation. Thereupon Rau became a delegate of the People's Chamber, the newly established parliament of the GDR and joined the new government.Likewise in 1949, the ruling SED implemented traditional leadership structures of communist parties and Rau became a member of the newly established Central Committee of the SED and candidate member of its Politburo; in 1950, a full member of the Politburo as well as deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers

Ministerrat

The Council of Ministers of the German Democratic Republic was the chief executive body of East Germany from November 1950 until the GDR was unified with the Federal Republic of Germany on 3 October 1990...

.

In 1949–1950, Rau was Minister for Planning of the GDR and in 1950–1952 chairman of the National Planning Commission. In this position, as the key figure of the economic development, Rau came into conflict with SED General Secretary

General Secretary

The office of general secretary is staffed by the chief officer of:*The General Secretariat for Macedonia and Thrace, a government agency for the Greek regions of Macedonia and Thrace...

Walter Ulbricht

Walter Ulbricht

Walter Ulbricht was a German communist politician. As First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party from 1950 to 1971 , he played a leading role in the creation of the Weimar-era Communist Party of Germany and later in the early development and...

. In the face of an imminent economic collapse, Rau blamed the "Bureau Ulbricht" for the wrong policy. In response East Germany's old president Wilhelm Pieck

Wilhelm Pieck

Friedrich Wilhelm Reinhold Pieck was a German politician and a Communist. In 1949, he became the first President of the German Democratic Republic, an office abolished upon his death. He was succeeded by Walter Ulbricht, who served as Chairman of the Council of States.-Biography:Pieck was born to...

renewed the old accusation of Trotskyism

Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the theory of Marxism as advocated by Leon Trotsky. Trotsky considered himself an orthodox Marxist and Bolshevik-Leninist, arguing for the establishment of a vanguard party of the working-class...

against Rau. In a later letter to Pieck of 28 November 1951 Rau protested at the manner in which the Secretariat usurped the Politburo by censoring his speech on economic affairs.

In 1952–1953, Rau led the newly established Coordination Centre for Industry and Traffic at the East German Council of Ministers.

After the death of Stalin in March 1953, the new collective Soviet leadership started to advocate a New Course

New Course

The New Course was a Soviet economic policy that aimed to improve the standard of living and to increase the availability of consumer goods in East Germany. There were three major thrusts of the new course. Improvement of consumer goods, the end of terror, and a relaxation of ideological...

. In this connection Moscow favored replacing East Germany's Stalinist party leader Walter Ulbricht and made enquiries about Rau as a potential candidate. Thereupon the leading SED party ideologist Rudolf Herrnstadt

Rudolf Herrnstadt

Rudolf Herrnstadt was a German journalist and communist politicianmost notable for his anti-fascist activity as an exile from the Nazi German regime in the Soviet Union during the war and as a journalist in East Germany until his death, where he and Wilhelm Zaisser represented the anti-Ulbricht...

, a candidate member of the Poliburo, drew with support and assistance by Heinrich Rau a concept for such a New Course in East Germany. However, the workers' uprising, which was suppressed by the Soviet army on 17 June led to a backlash. Three weeks later, during a session of the then eight person Politburo

Politburo

Politburo , literally "Political Bureau [of the Central Committee]," is the executive committee for a number of communist political parties.-Marxist-Leninist states:...

( plus six candidate members ) on 8 July 1953, Rau recommended to replace Ulbricht, while Rau's Spanish Civil War fellow, Stasi

Stasi

The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security (German: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (MfS), commonly known as the Stasi (abbreviation , literally State Security), was the official state security service of East Germany. The MfS was headquartered...

chief Wilhelm Zaisser

Wilhelm Zaisser

Wilhelm Zaisser was a German communist politician and the first Minister for State Security of the German Democratic Republic .- Life :...

, who in Spain had been known as 'General Gómez', accused Ulbricht of having perverted the party. The majority was against Ulbricht. His only supporters were Hermann Matern and Erich Honecker

Erich Honecker

Erich Honecker was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic as General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party from 1971 until 1989, serving as Head of State as well from Willi Stoph's relinquishment of that post in 1976....

. But at the moment there was no candidate to replace Ulbricht immediately. Suggested were first Rudolf Herrnstadt and then Heinrich Rau, but both were hesitant, thus a decision was postponed. The very next day after the meeting Ulbricht went by plane to Moscow and the Soviet leadership, who in part also feared, that deposing Ulbricht might be construed as a sign of weakness, secured Ulbricht's position now. Subsequently five members and candidate members of the Politburo lost their positions.

Competition in the Politburo and economic reform

Unlike some other rebels in the leadership, Rau kept most of his positions. He remained a member of the Politburo and deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. In the Politburo he continued to be responsible for the industry of the GDR. However, his position had been weakened. Bruno Leuschner, a follower of Ulbricht and Rau's successor as chairman of the National Planning Commission, became now a new candidate member of the Politburo. During the ensuing period, Leuschner, often supported by Ulbricht, gradually superseded Rau as 'Number One' for the economy as a whole. The official GDR press never mentioned the points of dissension between Rau and Leuschner and always described their cooperation as a success story.Concentrating on his tasks in the SED leadership and as a minister, Rau – despite occasional internal criticism – widely avoided an appearance of disharmony with Ulbricht present at this time, at least in public. In 1954, Rau received in the Order of Merit for the Fatherland (Vaterländischer Verdienstorden) in gold. Later, Ulbricht stated in a 1964 interview about the "introduction of socialism" in the GDR, that only three people were heavily involved in the economic development during that time: "namely Heinrich Rau, Bruno Leuschner and me. Others were not consulted!"

In 1953–1955 Rau led the new established Ministry for Machine Construction, which combined the responsibilities of three other until then existing ministries. His deputy in this ministry was Erich Apel, who would later, in the early 1960s, become an initiator and architect of an economic reform, which became known as the New Economic System

New Economic System

The New Economic System was an economic policy that was implemented by the ruling Socialist Unity Party of the German Democratic Republic in 1963. Its purpose was to replace the system of Five Year Plans which had been used to run the GDR's economy from 1951 onwards...

(NES).

This reform in the 1960s partially had already a forerunner reform in the middle of the 1950s and the economic historian Jörg Roesler considers the NES in the 1960s as a continuation of this foregoing reform. The origin of the reform in the 1950s was a scientific study, commissioned by Rau's ministry in 1953, to assess the need for greater economic efficiency in the factories. The subsequent results from this study promised enhanced economic efficiency by shifting more responsibility from the National Planning Commission to the enterprises themselves. Thenceforward, already in spring 1954, Rau advocated such a planning reform, while planning boss Bruno Leuschner quite consistently opposed it. In August 1954, Rau's ministry sent a concept for such a reform to Leuschner's State Planning Commission. Eventually this reform got under way, after Ulbricht, perhaps under the influence of his new personal economic adviser Wolfgang Berger, had approved such a policy at the end of 1954 too. Subsequently the reform accelerated until 1956. It found however its early end in the generally aggravated political atmosphere in 1957. Unrests in other Eastern Bloc countries during the previous year 1956, in particular in Hungary, had awoken the desire for more central control again. The subsequent unsatisfying economic development, however, during the following years eventually led in the 1960s to the concept of a new planning reform, the NES.

Foreign trade and foreign policy

Between 1955–1961 Rau served as Minister for Foreign Trade and Inter-German Trade. The term "Inter-German Trade" meant the trade with West GermanyWest Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

. In this time both German states still saw German reunification as their own aim, but both envisaging different political systems. The West German position was that they, as the only freely elected government, had an exclusive mandate

Exclusive Mandate

An exclusive mandate is a government's assertion of its legitimate authority over a certain territory, part of which another government controls with stable, de facto sovereignty...

for the entire German people. In consequence of this, the GDR's official diplomatic relationships with other states were narrowed to the states of the Eastern Bloc. Practically no other states recognized the GDR. As a result Rau's ministry established numerous new "trade missions" in other states, which served as a kind of surrogate for nonexistent embassies. It was a corollary, that Rau, in addition to his responsibility for the export-oriented industry, also chaired the Foreign Policy Commission of the SED Politburo (Außenpolitische Kommission beim Politbüro or APK) since 1955, in this period the actual decision-making body for foreign affairs, and visited other states in different parts of the world in this capacity. Among the visited states were, beside the core states of the Soviet Bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

, also then Eastern Bloc riparian states, like China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

and Albania

Albania

Albania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

and leading states of the crystallizing Non-Aligned Movement

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement is a group of states considering themselves not aligned formally with or against any major power bloc. As of 2011, the movement had 120 members and 17 observer countries...

like India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

(after the Bandung Conference). Between 1955 and 1957 he visited, as part of a diplomatic advertisement campaign in the Arab world, various Arabic states, among them repeatedly Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

. One of his last deals, which he closed as minister, was a trade agreement with Cuba

Cuba