High German consonant shift

Encyclopedia

Historical linguistics

Historical linguistics is the study of language change. It has five main concerns:* to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages...

, the High German consonant shift or second Germanic consonant shift is a phonological development (sound change

Sound change

Sound change includes any processes of language change that affect pronunciation or sound system structures...

) that took place in the southern parts of the West Germanic dialect continuum in several phases, probably beginning between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD, and was almost complete before the earliest written records in the High German language were made in the 9th century. The resulting language, Old High German

Old High German

The term Old High German refers to the earliest stage of the German language and it conventionally covers the period from around 500 to 1050. Coherent written texts do not appear until the second half of the 8th century, and some treat the period before 750 as 'prehistoric' and date the start of...

, can be neatly contrasted with the other continental West Germanic languages, which for the most part did not experience the shift, and with Old English

Old English language

Old English or Anglo-Saxon is an early form of the English language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons and their descendants in parts of what are now England and southeastern Scotland between at least the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century...

, which remained completely unaffected.

General description

The High German consonant shift altered a number of consonants in the Southern German dialects, and thus also in modern Standard GermanStandard German

Standard German is the standard variety of the German language used as a written language, in formal contexts, and for communication between different dialect areas...

, Yiddish, and Luxemburgish, and so explains why many German words have different consonants from the obviously related words in English and Dutch. Depending on definition, the term may be restricted to a core group of nine individual consonant modifications, or it may include other changes taking place in the same period.

For the core group, there are three changes which may be thought of as three successive phases, each affecting three consonants, making nine modifications in total:

- The three Germanic voicelessVoicelessIn linguistics, voicelessness is the property of sounds being pronounced without the larynx vibrating. Phonologically, this is a type of phonation, which contrasts with other states of the larynx, but some object that the word "phonation" implies voicing, and that voicelessness is the lack of...

stops became fricatives in certain phonetic environments (English ship maps to German Schiff); - The same sounds became affricatesAffricate consonantAffricates are consonants that begin as stops but release as a fricative rather than directly into the following vowel.- Samples :...

in other positions (apple : Apfel); and - The three voicedVoice (phonetics)Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds, with sounds described as either voiceless or voiced. The term, however, is used to refer to two separate concepts. Voicing can refer to the articulatory process in which the vocal cords vibrate...

stops became voiceless (door : Tür).

Since phases 1 and 2 affect the same voiceless sounds, some descriptions find it more convenient to treat them together, thus making only a twofold analysis, voiceless (phase 1–2) and voiced (phase 3). This has advantages for typology, but does not reflect the chronology.

Of the other changes that sometimes are bracketed within the High German consonant shift, the most important (sometimes thought of as the fourth phase) is:

- 4. /θ/ (and its allophoneAllophoneIn phonology, an allophone is one of a set of multiple possible spoken sounds used to pronounce a single phoneme. For example, and are allophones for the phoneme in the English language...

[ð]) became /d/ (this : dies).

This phenomenon is known as the "High German" consonant shift because it affects the High German

High German languages

The High German languages or the High German dialects are any of the varieties of standard German, Luxembourgish and Yiddish, as well as the local German dialects spoken in central and southern Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, Luxembourg and in neighboring portions of Belgium and the...

dialects (i.e. those of the mountainous south), principally the Upper German

Upper German

Upper German is a family of High German dialects spoken primarily in southern Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Northern Italy.-Family tree:Upper German can be generally classified as Alemannic or Austro-Bavarian...

dialects, though in part it also affects the Central German

Central German

Central German is a group of High German dialects spoken from the Rhineland in the west to the former eastern territories of Germany.-History:...

dialects. However the fourth phase also included Low German

Low German

Low German or Low Saxon is an Ingvaeonic West Germanic language spoken mainly in northern Germany and the eastern part of the Netherlands...

and Dutch

Dutch language

Dutch is a West Germanic language and the native language of the majority of the population of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second...

. It is also known as the "second Germanic" consonant shift to distinguish it from the "(first) Germanic consonant shift" as defined by Grimm's law

Grimm's law

Grimm's law , named for Jacob Grimm, is a set of statements describing the inherited Proto-Indo-European stops as they developed in Proto-Germanic in the 1st millennium BC...

, and its refinement, Verner's law

Verner's law

Verner's law, stated by Karl Verner in 1875, describes a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic language whereby voiceless fricatives *f, *þ, *s, *h, *hʷ, when immediately following an unstressed syllable in the same word, underwent voicing and became respectively the fricatives *b, *d, *z,...

.

The High German consonant shift did not occur in a single movement, but rather as a series of waves over several centuries. The geographical extent of these waves varies. They all appear in the southernmost dialects, and spread northwards to differing degrees, giving the impression of a series of pulses of varying force emanating from what is now Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

. Whereas some are found only in the southern parts of Alemannic (which includes Swiss German) or Bavarian (which includes Austrian), most are found throughout the Upper German area, and some spread on into the Central German dialects. Indeed, Central German is often defined as the area between the Appel/Apfel and the Dorp/Dorf boundaries. The shift þ→d was more successful; it spread all the way to the North Sea and affected Dutch as well as German. Most, but not all of these changes have become part of modern Standard German.

The High German consonant shift is a good example of a chain shift

Chain shift

In phonology, a chain shift is a phenomenon in which several sounds move stepwise along a phonetic scale. The sounds involved in a chain shift can be ordered into a "chain" in such a way that, after the change is complete, each phoneme ends up sounding like what the phoneme before it in the chain...

, as was its predecessor, the first Germanic consonant shift. For example, phases 1 and 2 left the language without a /t/ phoneme, as this had shifted to /s/ or /ts/. Phase 3 filled this gap (d→t), but left a new gap at /d/, which phase 4 then filled (þ→d).

Overview table

The effects of the shift are most obvious for the non-specialist when comparing Modern German lexemeLexeme

A lexeme is an abstract unit of morphological analysis in linguistics, that roughly corresponds to a set of forms taken by a single word. For example, in the English language, run, runs, ran and running are forms of the same lexeme, conventionally written as RUN...

s containing shifted consonants with their Modern English or Dutch unshifted equivalents. The following overview table is arranged according to the original Proto-Indo-European (PIE)

Proto-Indo-European language

The Proto-Indo-European language is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans...

phonemes. (G=Grimm's law; V=Verner's law) Note that the pairs of words used to illustrate sound shifts must be cognate

Cognate

In linguistics, cognates are words that have a common etymological origin. This learned term derives from the Latin cognatus . Cognates within the same language are called doublets. Strictly speaking, loanwords from another language are usually not meant by the term, e.g...

s; they need not be semantic equivalents. German Zeit means 'time' but it is cognate with tide, and only the latter is relevant here.

| PIE Proto-Indo-European language The Proto-Indo-European language is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans... →Germanic |

Phase | High German Shift Germanic→OHG |

Examples (Modern German) | Century | Geographical Extent1 | Standard German? |

Standard Dutch? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G: *b→*p | 1 | *p→ff | schlafen, Schiff cf. sleep, ship |

4/5 | Upper and Central German | Yes | No |

| 2 | *p→pf | Pflug, Apfel, Pfad, Pfuhl, scharf 2 cf. plough, apple, path, pool, sharp |

6/7 | Upper German | Yes | No | |

| G: *d→*t | 1 | *t→ss | essen, dass, aus 3 cf. eat, that, out |

4/5 | Upper and Central German | Yes | No |

| 2 | *t→ts | Zeit4, Zwei4, Zehe cf. tide, two, toe |

5/6 | Upper German | Yes | No | |

| G: *g→*k | 1 | *k→ch | machen, brechen, ich cf. make, break, Dutch ik "I" 5 |

4/5 | Upper and Central German | Yes | No |

| 2 | *k→kch | Bavarian: Kchind cf. German Kind "child" |

7/8 | Southernmost Austro-Bavarian and High Alemannic |

No | No | |

| G: }→*β V: *p→*β |

*β→b | geben, weib cf. give, wife, Dutch geven, wijf |

7/8 | Upper and Central German | Yes | No | |

| G: }→*ð V: *t→*ð |

*ð→d | gut, English good, Dutch goed cf. Icelandic góður |

2-4 | Throughout West Germanic | Yes | Yes | |

| G: }→*ɣ V: *k→*ɣ |

*ɣ→g | gut cf. Dutch goed |

7/8 | Upper and Central German | Yes | No | |

| G: (}→)*β→*b V: (*p→)*β→*b |

3 | *b→p | Bavarian: perg, pist cf. German Berg "hill", bist "(you) are" |

8/9 | Parts of Bavarian/Alemanic | No | No |

| G: (}→)*ð→*d V: (*t→)*ð→*d |

3 | *d→t | Tag, Mittel, Vater cf. day, middle, Dutch vader "father"6 |

8/9 | Upper German | Yes | No |

| G: (}→)*ɣ→*g V: (*k→)*ɣ→*g |

3 | *g→k | Bavarian: Kot cf. German Gott "God" |

8/9 | Parts of Bavarian/Alemanic | No | No |

| G: *t→þ [ð] | 4 | þ→ð→d | Dorn, Distel, durch, Bruder cf. thorn, thistle, through, brother |

9/10 | Throughout continental West Germanic | Yes | Yes |

Notes:

- Approximate, isoglosses may vary.

- Old High German scarph, Middle High German scharpf.

- Old High German ezzen, daz, ūz.

- Note that in modern German

- Old English ic, "I".

- Old English fæder, "father"; English has shifted d→th in a few OE words ending in vowel + -der.

Phase 1

The first phase, which affected the whole of the High German area, has been dated as early as the fourth century, though this is highly debated. The first certain examples of the shift are from the Edictus Rothari (a. 643, oldest extant manuscript after 650), a LatinLatin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

text of the Lombards

Lombards

The Lombards , also referred to as Longobards, were a Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin, who from 568 to 774 ruled a Kingdom in Italy...

. Lombard personal names show *b > p, having pert, perg, prand for bert, berg, brand. According to most scholars, the pre-Old High German runic inscriptions of about a. 600 show no convincing trace of the consonant shift.

In this phase, voiceless stops became geminated

Gemination

In phonetics, gemination happens when a spoken consonant is pronounced for an audibly longer period of time than a short consonant. Gemination is distinct from stress and may appear independently of it....

intervocalic fricatives, or single postvocalic fricatives in final position.

Note: In these OHG words,

Apical consonant

An apical consonant is a phone produced by obstructing the air passage with the apex of the tongue . This contrasts with laminal consonants, which are produced by creating an obstruction with the blade of the tongue .This is not a very common distinction, and typically applied only to fricatives...

while

Laminal consonant

A laminal consonant is a phone produced by obstructing the air passage with the blade of the tongue, which is the flat top front surface just behind the tip of the tongue on the top. This contrasts with apical consonants, which are produced by creating an obstruction with the tongue apex only...

.

Examples:

- Old English : Old High German

Note that the first phase did not affect geminate stops in words like *appul "apple" or *katta "cat", nor did it affect stops after other consonants, as in words like *scarp "sharp" or *hert "heart", where another consonant falls between the vowel and the stop. These remained unshifted until the second phase.

Phase 2

In the second phase, which was completed by the eighth century, the same sounds became affricates in three environments: in word-initial position; when geminated; and after a liquid consonantLiquid consonant

In phonetics, liquids or liquid consonants are a class of consonants consisting of lateral consonants together with rhotics.-Description:...

(/l/ or /r/) or nasal consonant

Nasal consonant

A nasal consonant is a type of consonant produced with a lowered velum in the mouth, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. Examples of nasal consonants in English are and , in words such as nose and mouth.- Definition :...

(/m/ or /n/).

- /p/ > /pf/ (also written

in OHG) - /t/ > /ts/ (written

or ) - /k/ > /kx/ (written

in OHG).

Examples:

- OE æppel : OHG apful, afful (English apple, Dutch appel, Low German Appel : German Apfel)

- OE scearp : OHG scarpf, scarf (English sharp, Dutch scherp, Low German scharp : German scharf)

- OE catt : OHG kazza (English cat, Dutch kat, Low German Katt : German Katze)

- OE tam : OHG zam (English tame, Dutch tam, Low German tamm : German zahm)

- OE liccian : OHG leckōn (English lick, Dutch likken, Low German licken, German lecken : High Alemannic lekchen, schlecke/schläcke /ʃlɛkxə, ʃlækxə/)

- OE weorc : OHG werc, werah (English work, Dutch werk, Low German Wark, German Werk : High Alemannic Werch/Wärch)

The shift did not take place where the stop was preceded by a fricative, i.e. in the combinations /sp, st, sk, ft, ht/. /t/ also remained unshifted in the combination /tr/.

- OE spearwa : OHG sparo (English sparrow, Dutch spreeuw, German Sperling)

- OE mæst : OHG mast (English mast, Dutch mast, Low German Mast, German Mast(baum))

- OE niht : OHG naht (English night, Dutch nacht, Low German Nacht, German Nacht)

- OE trēowe : OHG (gi)triuwi (English true, Dutch (ge)trouw, Low German trü, German treu; the cognates mean "trustworthy","faithful", not "correct","truthful".)

For the subsequent change of /sk/ > /ʃ/, written

These affricates (especially pf) have simplified into fricatives in some dialects. /pf/ was subsequently simplified to /f/ in a number of circumstances. In Yiddish and some German dialects this occurred in initial positions, e.g., Dutch paard : German Pferd : Yiddish ferd 'horse'. There was a strong tendency to simplify after /r/ and /l/, e.g. werfen 'to throw' ← OHG werfan ← *werpfan, helfen 'to help' ← OHG helfan ← *helpfan, but some forms with /pf/ remain, e.g. Karpfen 'carp' ← OHG karpfo.

- The shift of /t/ → /ts/ occurs throughout the High German area, and is reflected in Modern Standard German.

- The shift of /p/ → /pf/ occurs throughout Upper German, but there is wide variation in Central German dialects. In the Rhine FranconianRhine FranconianRhine Franconian , or Rhenish Franconian, is a dialect family of West Central German. It comprises the German dialects spoken across the western regions of the states of Saarland, Rhineland-Palatinate, and Hesse in Germany...

dialects, the further north the dialect, the fewer environments show shifted consonants. This shift is reflected in Standard German. - The shift of /k/ → /kx/ is geographically highly restricted and took place only in the southernmost Upper German dialects. Tyrolese, the Southern Austro-BavarianSouthern Austro-BavarianSouthern Bavarian, or Southern Austro-Bavarian, is a cluster of Germanic dialects of the Bavarian group.They are primarily spoken in the Austrian federal-states of Tyrol, Carinthia and Styria, in the southern parts of Salzburg and Burgenland as well as in the Italian province of South Tyrol...

dialect of TyrolCounty of TyrolThe County of Tyrol, Princely County from 1504, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, from 1814 a province of the Austrian Empire and from 1867 a Cisleithanian crown land of Austria-Hungary...

, is the only dialect in which the affricate /kx/ has developed in all positions, e.g. Cimbrian khòan [kxoːən] 'not any' (cf. Germ kein). In High AlemannicHigh Alemannic GermanHigh Alemannic is a branch of Alemannic German and is often considered to be part of the German language, even though it is only partly intelligible to non-Alemannic speakers....

, only the geminate has developed into an affricate, whereas in the other positions, /k/ has become /x/, e.g. HAlem chleubä 'to adhere, stick' (cf. Germ kleben). Initial /kx/ does occur to a certain extent in modern High Alemannic in place of any k in loanwords, e.g. [kxariˈb̥ikx], and /kx/ occurs where ge- + [x], e.g. Gchnorz [kxno(ː)rts] 'laborious work', from the verbVerbA verb, from the Latin verbum meaning word, is a word that in syntax conveys an action , or a state of being . In the usual description of English, the basic form, with or without the particle to, is the infinitive...

chnorze.

Phase 3

The third phase, which had the most limited geographical range, saw the voiced stops become voiceless.- b→p

- d→t

- g→k

Of these, only the dental shift d→t finds its way into standard German. The others are restricted to High Alemannic German in Switzerland, and south Bavarian dialects in Austria.

This shift probably began in the 8th or 9th century, after the first and second phases ceased to be productive, otherwise the resulting voiceless stops would have shifted further to fricatives and affricates.

In those words in which an Indo-European voiceless stop became voiced as a result of Verner's Law, phase three of the High German shift returns this to its original value (*t → d → t):

- PIE *meh₂tḗr

- → early Proto-Germanic *māþḗr (t → /θ/ by the First Germanic Consonant ShiftGrimm's lawGrimm's law , named for Jacob Grimm, is a set of statements describing the inherited Proto-Indo-European stops as they developed in Proto-Germanic in the 1st millennium BC...

) - → late Proto-Germanic *mōđēr (/θ/ → /ð/ by Verner's LawVerner's lawVerner's law, stated by Karl Verner in 1875, describes a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic language whereby voiceless fricatives *f, *þ, *s, *h, *hʷ, when immediately following an unstressed syllable in the same word, underwent voicing and became respectively the fricatives *b, *d, *z,...

) - → West-Germanic *mōdar (/ð/ → d by West Germanic sound change)

- → Old High German muotar (d → t by the Second Germanic Consonant Shift)

Examples:

- OE dōn : OHG tuon (English do, Dutch doen, Low German doon : German tun)

- OE mōdor : OHG muotar (English mother, Dutch moeder, Low German Modder, Mudder : German Mutter)

- OE rēad : OHG rōt (English red, Dutch rood, Low German root : German rot)

- OE biddan : OHG bitten or pitten (English bid, Dutch bieden, Low German bidden : German bitten, Bavarian pitten)

It is possible that pizza

Pizza

Pizza is an oven-baked, flat, disc-shaped bread typically topped with a tomato sauce, cheese and various toppings.Originating in Italy, from the Neapolitan cuisine, the dish has become popular in many parts of the world. An establishment that makes and sells pizzas is called a "pizzeria"...

is an early Italian borrowing of OHG (Bavarian dialect) pizzo, a shifted variant of bizzo (German Bissen, 'bite, snack').

Other changes in detail

Other consonant changes on the way from West Germanic to Old High German are included under the heading "High German consonant shift" by some scholars that see the term as a description of the whole context, but are excluded by others that use it to describe the neatness of the threefold chain shift. Although it might be possible to see /ð/ →/d/, /ɣ/ →/ɡ/ and /v/ →/b/ as a similar group of three, both the chronology and the differing phonetic conditions under which these changes occur speak against such a grouping.þ/ð→d (Phase 4)

What is sometimes known as the fourth phase shifted the dental fricatives to /d/. This is distinctive in that it also affects Low German and Dutch. In Germanic, the voiceless and voiced dental fricatives þ and ð stood in allophonic relationship, with þ in initial and final position and ð used medially. These merged into a single /d/. This shift occurred late enough that unshifted forms are to be found in the earliest Old High German texts, and thus it can be dated to the 9th or 10th century. It took several centuries to spread north, appearing in Dutch only during the 12th century, and in Frisian not for another century or two after that.- early OHG

In dialects affected by phase 4 but not by the dental variety of phase 3, that is, Low German, Central German, and Dutch, two Germanic phonemes merged: þ becomes d, but original Germanic d remains unchanged:

| German | Dutch | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| original /þ/ (→ /d/ in German and Dutch) | Tode | dood | death |

| original /d/ (→ /t/ in German) | Tote | dode | dead |

One consequence of this is that there is no dental variety of Grammatischer Wechsel

Grammatischer Wechsel

In historical linguistics, the German term Grammatischer Wechsel refers to the effects of Verner's law when viewed synchronically within the paradigm of a Germanic verb.-Overview:...

in Middle Dutch

Middle Dutch

Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects which were spoken and written between 1150 and 1500...

.

In 1955, Otto Höfler suggested that a change analogous to the fourth phase of the High German consonant shift may have taken place in Gothic

Gothic language

Gothic is an extinct Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizable Text corpus...

(East Germanic) as early as the third century AD, and he hypothesised that it may have spread from Gothic to High German as a result of the Visigoth

Visigoth

The Visigoths were one of two main branches of the Goths, the Ostrogoths being the other. These tribes were among the Germans who spread through the late Roman Empire during the Migration Period...

ic migrations westward (c. 375–500 AD). This has not found wide acceptance; the modern consensus is that Höfler misinterpreted some sound substitutions of Romanic languages as Germanic, and that East Germanic shows no sign of the second consonant shift.

/ɣ/→/ɡ/

The West Germanic voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ shifted to /ɡ/ in Old High German in all positions. This change is believed to be early and complete by the 8th century at the latest. Since the existence of a /g/ was necessary for the south German shift g→k, this must at least predate phase 3 of the core High German consonant shift.The same change occurred independently in Old English around the 10th century (as suggested by changing patterns of alliteration), except when preceding or following a front vowel where it had earlier undergone Anglo-Frisian palatalisation and ended up as /j/. Dutch has retained the original /ɣ/, despite the fact it is spelled with

- Dutch goed (/ɣut/) : German gut, English good

- Dutch gisteren (/ɣɪstərə(n)/) : German gestern : English yester(day), West Frisian juster

[β]→/b/

West Germanic *ƀ (presumably pronounced [β]), which was an allophone of /b/ used in medial position, shifted to Old High German /b/ between two vowels, and also after /l/.- OE lēof : OHG liob, liup (obs. English †lief, Dutch lief, Low German leev : German lieb)

- OE hæfen : MHG habe(ne) (English haven, Dutch haven, Low German Haven; for German Hafen see below)

- OE half : OHG halb (English half, Dutch half, Low German halv : German halb)

- OE lifer : OHG libara, lebra (English liver, Dutch lever, Low German Läver : German Leber)

- OE selfa : OHG selbo (English self, Dutch zelf, Low German sülve : German selbe)

- OE sealf : OHG salba (English salve, Dutch zalf, Low German Salv : German Salbe)

In strong verbs such as German heben 'heave' and geben 'give', the shift contributed to eliminating the [β] forms in German, but a full account of these verbs is complicated by the effects of grammatischer Wechsel by which [β] and [b] appear in alternation in different parts of the same verb in the early forms of the languages. In the case of weak verbs such as haben 'have' (cf. Dutch hebben) and leben 'live' (cf. Dutch leven), the consonant differences have an unrelated origin, being a result of the Germanic spirant law

Germanic spirant law

In linguistics, the Germanic spirant law or Primärberührung is a specific historical instance of dissimilation that occurred as part of an exception of Grimm's law in the ancestor of the Germanic languages.-General description:...

and a subsequent process of levelling.

/s/→/ʃ/

High German experienced the shift /sp/, /st/, /sk/ → /ʃp/, /ʃt/, /ʃ/ in initial position:-

- German spinnen (/ʃp/), spin.

- German Straße (/ʃt/), street.

- German Schrift, script.

This change also spread far north but stopped short of Dutch, although Limburgish was affected.

Terminal devoicing

Other changes include a general tendency towards terminal devoicing in German and Dutch, and to a far more limited extent in English. Thus, in German and Dutch,Nevertheless, the original voiced consonants are usually represented in modern German and Dutch spelling. This is probably because related inflected forms, such as the plural Tage, have the voiced form, since here the stop is not terminal. As a result of these inflected forms, native speakers remain aware of the underlying voiced phoneme, and spell accordingly. However, in Middle High German, these sounds were spelled differently: singular tac, plural tage.

Chronology

Since, apart from þ→d, the High German consonant shift took place before the beginning of writing of Old High German in the 9th century, the dating of the various phases is an uncertain business. The estimates quoted here are mostly taken from the dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache (p. 63). Different estimates appear elsewhere, for example Waterman, who asserts that the first three phases occurred fairly close together and were complete in Alemannic territory by 600, taking another two or three centuries to spread north.Sometimes historical constellations help us; for example, the fact that Attila

Attila the Hun

Attila , more frequently referred to as Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in 453. He was leader of the Hunnic Empire, which stretched from the Ural River to the Rhine River and from the Danube River to the Baltic Sea. During his reign he was one of the most feared...

is called Etzel in German proves that the second phase must have been productive after the Hunnish invasion of the 5th century. The fact that many Latin loan-words are shifted in German (e.g., Latin strata→German Straße), while others are not (e.g., Latin poena→German Pein) allows us to date the sound changes before or after the likely period of borrowing. However the most useful source of chronological data is German words cited in Latin texts of the late classical and early mediaeval period.

Precise dating would in any case be difficult, since each shift may have begun with one word or a group of words in the speech of one locality, and gradually extended by lexical diffusion

Lexical diffusion

In historical linguistics, lexical diffusion is both a phenomenon and a theory. The phenomenon is that by which a phoneme is modified in a subset of the lexicon, and spreads gradually to other lexical items...

to all words with the same phonological pattern, and then over a longer period of time spread to wider geographical areas.

However, relative chronology for phases 2, 3, and 4 can easily be established by the observation that t→tz must precede d→t, which in turn must precede þ→d; otherwise words with an original þ could have undergone all three shifts and ended up as tz. By contrast, as the form kepan for "give" is attested in Old Bavarian, showing both /ɣ/ → /ɡ/ → /k/ and /β/ → /b/→ /p/, it follows that /ɣ/ →/ɡ/ and /β/ →/b/ must predate phase 3.

Alternative chronologies have been proposed. According to a theory by the controversial German linguist Theo Vennemann

Theo Vennemann

Theo Vennemann is a German linguist known best for his work on historical linguistics, especially for his disputed theories of a Vasconic substratum and an Atlantic superstratum of European languages. He also suggests that the High German consonant shift was already completed in the early 1st...

, the consonant shift occurred much earlier and was already completed in the early 1st century BC. On this basis, he subdivides the Germanic languages into High Germanic and Low Germanic. Apart from Vennemann, few other linguists share this view.

Geographical distribution

| Dialects and isoglosses of the Rhenish Fan (Arranged from north to south: dialects in dark fields, isoglosses in light fields) |

||

| Isogloss | North | South |

| Dutch Dutch language Dutch is a West Germanic language and the native language of the majority of the population of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second... (West Low Franconian) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Uerdingen line Uerdingen line The Uerdingen Line is the isogloss within West Germanic languages that separates dialects which preserve the -k sound at the end of a word from dialects in which the word final -k has changed to word final -ch... (Uerdingen Uerdingen Uerdingen is a district of the city of Krefeld, Germany, with a population of 18,507, though Uerdingen received its charter as a city as early as 1255, well before Krefeld. Uerdingen was merged with Krefeld in 1929, after which the term “Krefeld-Uerdingen” was used, until, eventually, the use of... ) |

ik | ich |

| Limburgian (East Low Franconian) | ||

| Benrath line Benrath line In German linguistics, the Benrath line is the maken-machen isogloss: dialects north of the line have the original in maken , while those to the south have... (Boundary: Low German — Central German) |

maken | machen |

| Ripuarian Franconian (Cologne Kölsch language Kölsch is a very closely related small set of dialects, or variants, of the Ripuarian Central German group of languages. Kölsch is spoken in and partially around Cologne in the area covered by the Archdiocese and former Electorate of Cologne reaching from Neuss in the north to just south of Bonn,... , Bonn Bönnsch This article describes the language. For the beer see Bönnsch .Bönnsch is the Ripuarian dialect spoken in central Bonn, Germany. Bönnsch is closely related to Kölsch, but it has a different melody and a slightly different vocabulary. Bönnsch is described as having a more singsong sound than Kölsch... , Aachen) |

||

| Bad Honnef Bad Honnef Bad Honnef is a spa town in Germany near Bonn in the Rhein-Sieg district, North Rhine-Westphalia. It is located on the border of the neighbouring state Rhineland-Palatinate... line (State border NRW North Rhine-Westphalia North Rhine-Westphalia is the most populous state of Germany, with four of the country's ten largest cities. The state was formed in 1946 as a merger of the northern Rhineland and Westphalia, both formerly part of Prussia. Its capital is Düsseldorf. The state is currently run by a coalition of the... -RP Rhineland-Palatinate Rhineland-Palatinate is one of the 16 states of the Federal Republic of Germany. It has an area of and about four million inhabitants. The capital is Mainz. English speakers also commonly refer to the state by its German name, Rheinland-Pfalz .... ) (Eifel-Schranke) |

Dorp | Dorf |

| West Mosel Franconian (Luxemburgish, Trier) | ||

| Linz line (Linz am Rhein Linz am Rhein Linz am Rhein is a municipality in the district of Neuwied, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is situated on the right bank of the river Rhine near Remagen, approx. 25 km southeast of Bonn and has about 6,000 inhabitants... ) |

tussen | zwischen |

| Bad Hönningen Bad Hönningen Bad Hönningen is a municipality in the district of Neuwied, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is situated on the right bank of the Rhine, approx... line |

op | auf |

| East Mosel Franconian (Koblenz, Saarland) | ||

| Boppard line Boppard line In German linguistics, the Boppard Line is an isogloss separating the dialects to the north, which have an /f/ as in the word Korf, "basket", from the dialects to the south , which have a /b/: Korb. The line runs from east to west and crosses the river Rhine at the town of Boppard.-See also:* High... (Boppard Boppard Boppard is a town in the Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, lying in the Rhine Gorge, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It belongs to no Verbandsgemeinde. The town is also a state-recognized tourism resort and is a winegrowing centre.-Location:Boppard lies on the upper Middle... ) |

Korf | Korb |

| Sankt Goar line Sankt Goar line In German linguistics, the Sankt Goar line, Das-Dat line , or the Was–Wat line is an isogloss separating the dialects to the north, which have a /t/ in the words dat "that" and wat "what", from the dialects to the south , which have an /s/: das, was... (Sankt Goar Sankt Goar Sankt Goar is a town on the left bank of the Middle Rhine in the Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Sankt Goar-Oberwesel, whose seat is in the town of Oberwesel.... ) (Hunsrück Hunsrück The Hunsrück is a low mountain range in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is bounded by the river valleys of the Moselle , the Nahe , and the Rhine . The Hunsrück is continued by the Taunus mountains on the eastern side of the Rhine. In the north behind the Moselle it is continued by the Eifel... -Schranke) |

dat | das |

| Rhenish Franconian (Pfälzisch, Frankfurt) | ||

| Speyer line Speyer line In German linguistics, the Speyer line, or Main line is an isogloss separating the dialects to the north, which have a geminated stop in words like Appel "apple", from the dialects to the south, which have an affricate: Apfel. The line runs from east to west and passes through the town of Speyer... (River Main line) (Boundary: Central German — Upper German) |

Appel | Apfel |

| Upper German | ||

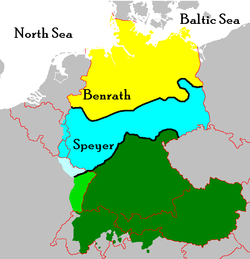

Roughly, the changes resulting from phase 1 affected Upper and Central German, those from phase 2 and 3 only Upper German, and those from phase 4 the entire German and Dutch-speaking region. The generally-accepted boundary between Central and Low German, the maken-machen line, is sometimes called the Benrath line, as it passes through the Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and centre of the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region.Düsseldorf is an important international business and financial centre and renowned for its fashion and trade fairs. Located centrally within the European Megalopolis, the...

suburb of Benrath

Düsseldorf-Benrath

Benrath is a part of Düsseldorf in the south of the city. It has been a part of Düsseldorf since 1929.-History:The name Benrath came from the "Knights of Benrode". The settlement was mentioned for the first time in 1222 in a document from Cologne where Everhard de Benrode is named as an attestor...

, while the main boundary between Central and Upper German, the Appel-Apfel line can be called the Speyer line, as it passes near the town of Speyer

Speyer

Speyer is a city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located beside the river Rhine, Speyer is 25 km south of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. Founded by the Romans, it is one of Germany's oldest cities...

, some 200 kilometers further south.

However, a precise description of the geographical extent of the changes is far more complex. Not only do the individual sound shifts within a phase vary in their distribution (phase 3, for example, partly affects the whole of Upper German and partly only the southernmost dialects within Upper German), but there are even slight variations from word to word in the distribution of the same consonant shift. For example, the ik-ich line lies further north than the maken-machen line in western Germany, coincides with it in central Germany, and lies further south at its eastern end, although both demonstrate the same shift /k/→/x/.

Rhenish Fan

The subdivision of West Central German into a series of dialects according to the differing extent of the phase 1 shifts is particularly pronounced. This is known as the Rhenish fan (German: Rheinischer Fächer, Dutch: Rijnlandse waaier), because on the map of dialect boundaries the lines form a fan shape. Here, no fewer than eight isoglosses run roughly West to East, partially merging into a simpler system of boundaries in East Central German. The table on the right lists these isoglosses (bold) and the main resulting dialects (italics), arranged from north to south.Lombardic

Some of the consonant shifts resulting from the second and third phases appear also to be observable in LombardicLombardic language

Lombardic or Langobardic is the extinct language of the Lombards , the Germanic speaking people who settled in Italy in the 6th century. The language declined rapidly already in the 7th century as the invaders quickly adopted the Latin vernacular spoken by the local Roman population. E.g...

, the early mediaeval Germanic language of northern Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, which is preserved in runic fragments of the late 6th and early 7th centuries. However, the Lombardic records are not sufficient to allow a complete taxonomy of the language. It is therefore uncertain whether the language experienced the full shift or merely sporadic reflexes, but b→p is clearly attested. This may mean that the shift began in Italy, or that it spread southwards as well as northwards. Ernst Schwarz and others have suggested that the shift occurred in German as a result of contacts with Lombardic. If, in fact, there is a relationship here, the evidence of Lombardic would force us to conclude that the third phase must have begun by the late 6th century, rather earlier than most estimates, but this would not necessarily require that it had spread to German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

so early.

If, as some scholars believe, Lombardic was an East Germanic

East Germanic languages

The East Germanic languages are a group of extinct Indo-European languages in the Germanic family. The only East Germanic language of which texts are known is Gothic; other languages that are assumed to be East Germanic include Vandalic, Burgundian, and Crimean Gothic...

language and not part of the German language dialect continuum, it is possible that parallel shifts took place independently in German and Lombardic. However the extant words in Lombardic show clear relations to Bavarian

Austro-Bavarian

Bavarian , also Austro-Bavarian, is a major group of Upper German varieties spoken in the south east of the German language area.-History and origin:...

. Therefore Werner Betz and others prefer to treat Lombardic as an Old High German

Old High German

The term Old High German refers to the earliest stage of the German language and it conventionally covers the period from around 500 to 1050. Coherent written texts do not appear until the second half of the 8th century, and some treat the period before 750 as 'prehistoric' and date the start of...

dialect. There were close connections between Lombards and Proto-Bavarians. For example, the Lombards settled in 'Tullner Feld' (about 50 km west of Vienna) until 568, but it is evident that not all Lombards went to Italy after that time; the rest seem to have become part of the then newly-formed Bavarian groups.

When Columban came to the Alamanni at Lake Constance shortly after 600, he made barrels burst, called cupa (English cup, German Kufe), according to Jonas of Bobbio (before 650) in Lombardy. This shows that in the time of Columban the shift from p to f had occurred neither in Alemannic nor in Lombardic. But the Edictus Rothari attests the forms grapworf ('throwing a corpse out of the grave', German Wurf and Grab), marhworf ('a horse', OHG marh, 'throws the rider off'), and many similar shifted examples. So it is best to see the consonant shift as a common Lombardic—Bavarian—Alemannic shift between 620 and 640, when these tribes had plenty of contact.

Sample texts

As an example of the effects of the shift one may compare the following texts from the later Middle Ages, on the left a Middle Low GermanMiddle Low German

Middle Low German is a language that is the descendant of Old Saxon and is the ancestor of modern Low German. It served as the international lingua franca of the Hanseatic League...

citation from the Sachsenspiegel

Sachsenspiegel

The Sachsenspiegel is the most important law book and legal code of the German Middle Ages. Written ca...

(1220), which does not show the shift, and on the right the same text from the Middle High German

Middle High German

Middle High German , abbreviated MHG , is the term used for the period in the history of the German language between 1050 and 1350. It is preceded by Old High German and followed by Early New High German...

Deutschenspiegel (1274), which shows the shifted consonants; both are standard legal texts of the period.

| Sachsenspiegel (II,45,3) | Deutschenspiegel (Landrecht 283) | |

|---|---|---|

| De man is ok vormunde sines wives, to hant alse se eme getruwet is. Dat wif is ok des mannes notinne to hant alse se in sin bedde trit, na des mannes dode is se ledich van des mannes rechte. |

Der man ist auch vormunt sînes wîbes zehant als si im getriuwet ist. Daz wîp ist auch des mannes genôzinne zehant als si an sîn bette trit nâch des mannes rechte. |

Unshifted forms in Standard German

The High German consonant shift — at least as far as the core group of changes is concerned — is an example of a sound change that permits no exceptions, and was frequently cited as such by the Neogrammarians. However, modern standard German, though based on Central German, draws vocabulary from all German dialects. When a native German word (as opposed to a loan word) contains consonants unaffected by the shift, they are usually explained as being Low German forms. Either the shifted form has fallen out of use, as in:- Hafen ('harbour', 'haven'); Middle High German had the shifted form habe(n), but the Low German form replaced it in modern times.

or the two forms remain side-by-side, as in:

- Wappen ('coat of arms'); the shifted form also exists, but with a different meaning: Waffen ('weapons')

Most words in Standard German that lack the shift are of Low German origin:

- Lippe ('lip'); Pegel ('water level'); Pickel ('pimple')

However, the vast majority of words in Modern German containing consonant patterns which would have been eliminated by the shift are loaned from Latin or Romance languages, English or Slavic:

- Paar ('pair','couple'), Ratte ('rat'), Peitsche ('whip').

See also

- Glottalic theoryGlottalic theoryThe glottalic theory holds that Proto-Indo-European had ejective stops, , but not the murmured ones, , of traditional Proto-Indo-European phonological reconstructions....

- Low Dietsch dialects

- The Tuscan gorgiaTuscan gorgiaThe Tuscan gorgia is a phonetic phenomenon which characterizes the Tuscan dialects, in Tuscany, Italy, most especially the central ones, with Florence traditionally viewed as the epicenter.-Description:...

, a similar evolution differentiating the Tuscan dialectTuscan dialectThe Tuscan language , or the Tuscan dialect is an Italo-Dalmatian language spoken in Tuscany, Italy.Standard Italian is based on Tuscan, specifically on its Florentine variety...

s from Standard Italian.

Sources

- The sample texts have been copied over from Lautverschiebung on the German Wikipedia.

- Dates of sound shifts are taken from the dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache (p. 63).

- Friedrich Kluge (revised Elmar Seebold), Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (The Etymological Dictionary of the German Language), 24th edition, 2002.

- Paul/Wiehl/Grosse, Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik (Middle-High German Grammar), 23rd ed, Tübingen 1989, 114–22.

- Fausto Cercignani, The Consonants of German: Synchrony and Diachrony, Milano, Cisalpino, 1979.

- Philippe Marcq & Thérèse Robin, Linguistique historique de l'allemand, Paris, 1997.

- Robert S. P. Beekes, Vergelijkende taalwetenschap, Utrecht, 1990.