History of Anglo-Saxon England

Encyclopedia

Anglo-Saxon England refers to the period of the history of that part of Britain, that became known as England

, lasting from the end of Roman occupation

and establishment of Anglo-Saxon

kingdoms in the 5th century until the Norman conquest of England

in 1066 by William the Conqueror. Anglo-Saxon is a general term referring to the Germanic peoples

who came to Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries, including Angles

, Saxons

, Frisii

and Jutes

. The term also refers to the language spoken at the time in England, which is now called Old English, and to the culture of the era, which has long attracted popular and scholarly attention.

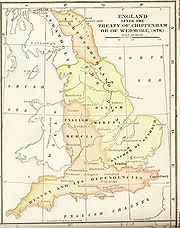

Until the 9th century Anglo-Saxon England was dominated by the Heptarchy

, the kingdoms of Northumbria

, Mercia

, East Anglia, Essex

, Kent

, Sussex

and Wessex

. In terms of religion the kingdoms followed Anglo-Saxon paganism during the early period, but converted to Christianity during the 7th century. Paganism had a final stronghold in a period of Mercian hegemony during the 640s, ending with the death of Penda of Mercia

in 655.

Facing the threat of Viking

invasions, the House of Wessex

became dominant during the 9th century, under the rule of Alfred the Great

. During the 10th century, the individual kingdoms unified under the rule of Wessex into the Kingdom of England

, which stood opposed to the Danelaw

, the Viking kingdoms established from the 9th century in the north and east of England. The Kingdom of England fell in the Viking invasion from Denmark in 1013 and was ruled by the House of Denmark

until 1042, when the Anglo-Saxon House of Wessex

was restored. The last Anglo-Saxon king, Harold Godwinson

, was killed in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings

.

withdrew the remains of the army, in reaction to the barbarian invasion of Europe. The Romano-British leaders were faced with an increasing security problem from sea borne raids, particularly by Picts

on the East coast of England. The expedient adopted by the Romano-British leaders was to enlist the help of Anglo-Saxon mercenaries (known as foederati

), to whom they ceded territory. In about AD 442 the Anglo-Saxons mutinied, apparently because they had not been paid. The British responded by appealing to the Roman commander of the Western empire Aëtius

for help (a document known as the Groans of the Britons

), even though Honorius

, the Western Roman Emperor, had written to the British civitas

in or about AD 410 telling them to look to their own defence. There then followed several years of fighting between the British and the Anglo-Saxons. The fighting continued until around AD 500, when, at the Battle of Mount Badon

, the Britons inflicted a severe defeat on the Anglo-Saxons.

There are literary sources:

Other written sources include:

Non-literary sources include:

There are records of Germanic infiltration into Britain that date before the collapse of the Roman Empire. It is believed that the earliest Germanic visitors were eight cohorts

There are records of Germanic infiltration into Britain that date before the collapse of the Roman Empire. It is believed that the earliest Germanic visitors were eight cohorts

of Batavians

attached to the 14th Legion

in the original invasion force under Aulus Plautius

in AD 43. There is a hypothesis that some of the native tribes

, identified as Britons by the Romans, may have been Germanic language speakers although most modern scholars refute this.

It was quite common for Rome to swell its legions with foederati recruited from the German homelands. This practice also extended to the army serving in Britain, and graves of these mercenaries, along with their families, can be identified in the Roman cemeteries of the period. The migration continued with the departure of the Roman army, when Anglo-Saxons were recruited to defend Britain; and also during the period of the Anglo-Saxon first rebellion of AD 442.

If the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

is to be believed, the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which eventually merged to become England were founded when small fleets of three or five ships of invaders arrived at various points around the coast of England to fight the Sub-Roman British, and conquered their lands. As Margaret Gelling

points out, in the context of place name evidence, what actually happened between the departure of the Romans and the coming of the Normans is the subject of much disagreement by historians.

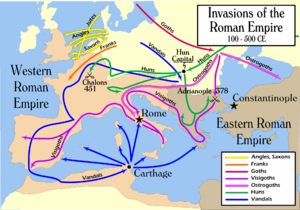

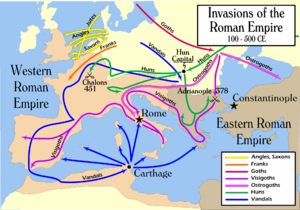

The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons into Britain can be seen in the context of a general movement of German people around Europe between the years 300 and 700, known as the Migration period

(also called the Barbarian Invasions or Völkerwanderung). In the same period there were migrations of Britons to the Armorican peninsula (Brittany

and Normandy

in modern day France

): initially around AD 383 during Roman rule, but also c. 460 and in the 540s and 550s; the 460s migration is thought to be a reaction to the fighting during the Anglo-Saxon mutiny between about 450 to 500, as was the migration to Britonia

(modern day Galicia, in northwest Spain) at about the same time.

The historian Peter Hunter-Blair

expounded what is now regarded as the traditional view of the Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain. He suggested a mass immigration, fighting and driving the Sub-Roman Britons off their land and into the western extremities of the islands, and into the Breton and Iberian peninsulas.

The modern view is of co-existence between the British and the Anglo-Saxons.

Discussions and analysis

still continue on the size of the migration, and whether it was a small elite band of Anglo-Saxons who came in and took over the running of the country, or a mass migration of peoples who overwhelmed the Britons.

After the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons by the British at the Battle of Mount Badon in c. AD 500, where according to Gildas

the British resistance was led by a man called Ambrosius Aurelianus

, Anglo-Saxon migration was temporarly stemmed. Gildas said that this was "forty-four years and one month" after the arrival of the Saxons, and was also the year of his birth. He said that a time of great prosperity followed. But, despite the lull, the Anglo-Saxons took control of Sussex, Kent, East Anglia and part of Yorkshire; while the West Saxons founded a kingdom in Hampshire under the leadership of Cerdic, around AD 520. However, it was to be 50 years before the Anglo-Saxons began further major advances. In the intervening years the Britons exhausted themselves with civil war, internal disputes, and general unrest: which was the inspiration behind Gildas's book De Excidio Britanniae (The Ruin of Britain).

The next major campaign against the Britons was in AD 577, led by Cealin, king of Wessex, whose campaigns succeeded in taking Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath (known as the Battle of Dyrham). This expansion of Wessex ended abruptly when the Anglo-Saxons started fighting amongst themselves, and resulted in Cealin eventually having to retreat to his original territory. He was then replaced by Ceol (who was possibly his nephew): Cealin was killed the following year, but the annals do not specify by whom. Cirencester subsequently became an Anglo-Saxon kingdom under the overlordship of the Mercians, rather than Wessex.

, which consisted of the seven principal Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The four main kingdoms

The four main kingdoms

in Anglo-Saxon England

were:

Minor kingdoms:

At the end of the 6th century the most powerful ruler in England was Æthelberht of Kent, whose lands extended north to the Humber. In the early years of the 7th century, Kent and East-Anglia were the leading English kingdoms. After the death of Æthelberht in 616, Rædwald of East Anglia became the most powerful leader south of the Humber.

Following the death of Æthelfrith of Northumbria, Rædwald provided military assistance to the Deiran Edwin

, in his struggle to take over the two dynasties of Deira

and Bernicia

in the unified kingdom of Northumbria.

On the death of Rædwald, Edwin was able to pursue a grand plan to expand Northumbrian power.

The growing strength of Edwin of Northumbria forced the Anglo-Saxon Mercians under Penda into an alliance with the Welsh King Cadwallon of Gwynedd, and together they invaded Edwin's lands and defeated and killed him at the Battle of Hatfield Chase

in 633. Their success was short-lived, as Oswald (one of the dead King of Northumbria, Æthelfrith's, sons) defeated and killed Cadwallon at Heavenfield near Hexham. In less than a decade Penda again waged war against Northumbria, and killed Oswald in battle during AD 642. His brother Oswiu was chased to the northern extremes of his kingdom. However, Oswiu killed Penda shortly after, and Mercia spent the rest of the 7th and all of the 8th century fighting the kingdom of Powys. The war reached its climax during the reign of Offa

of Mercia, who is remembered for the construction of a 150 mile long dyke

which formed the Wales/ England border. It is not clear whether this was a boundary line or a defensive position. The ascendency of the Mercians came to an end in AD 825, when they were soundly beaten under Beornwulf at the Battle of Ellendun by Egbert of Wessex.

Christianity was introduced into the British Isles during the Roman occupation. The early Christian Berber

author, Tertullian

, writing in the third century, said that "Christianity could even be found in Britain." The Roman Emperor Constantine

(AD 306-337), granted official tolerance to Christianity with the Edict of Milan

in AD 313. Then, in the reign of Emperor Theodosius "the Great"

(AD 378-395), Christianity was made the official religion of the Roman Empire

.

It is not entirely clear how many Britons would have been Christian when the pagan Anglo-Saxons arrived. There had been attempts to evangelise the Irish by Pope Celestine in AD 431. However, it was Saint Patrick

who is credited with converting the Irish en-masse. A Christian Ireland then set about evangelising the rest of the British Isles, and Columba

was sent to found a religious community in Iona, off the west coast of Scotland. Then Aidan

was sent from Iona to set up his see in Northumbria, at Lindisfarne, between AD 635-651. Hence Northumbria was converted by the Celtic (Irish) church.

Bede is very uncomplimentary about the indigenous British clergy: in his Historia ecclesiastica he complains of their unspeakable crimes, and that they did not preach the faith to the Angles or Saxons. Pope Gregory sent Augustine

in AD 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons, but Bede says the British clergy refused to help Augustine in his mission. Despite Bede's complaints, it is now believed that the Britons played an important role in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. On arrival in the south east of England in AD 597, Augustine was given land by King Æthelberht of Kent to build a church; so in 597 Augustine built the church and founded the See at Canterbury. He baptised Æthelberht in 601, then continued with his mission to convert the English. Most of the north and east of England had already been evangelised by the Irish Church. However, Sussex and the Isle of Wight remained mainly pagan until the arrival of Saint Wilfrid

, the exiled Archbishop of York, who converted Sussex around AD 681 and the Isle of Wight in 683.

It remains unclear what 'conversion' actually meant. The ecclesiastical writers tended to declare a territory as 'converted' merely because the local king had agreed to be baptised, regardless of whether, in reality, he actually adopted Christian practices; and regardless, too, of whether the general population of his kingdom did. When churches were built, they tended to include pagan as well as Christian symbols, evidencing an attempt to reach out to the pagan Anglo-Saxons, rather than demonstrating that they were already converted.

Even after Christianity had been set up in all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, there was friction between the followers of the Roman rites and the Irish rites, particularly over the date on which Easter fell and the way monks cut their hair. In AD 664 a conference was held at Whitby Abbey (known as the Whitby Synod

) to decide the matter; Saint Wilfrid was an advocate for the Roman rites and Bishop Colmán

for the Irish rites. Wilfrid's argument won the day and Colmán and his party returned to Ireland in their bitter disappointment. The Roman rites were adopted by the English church, although they were not universally accepted by the Irish Church.

Between the eighth and eleventh centuries, raiders and colonists from Scandinavia, mainly Danish and Norwegian, plundered western Europe including the British Isles. These raiders came to be known as the Vikings; the name is believed to derive from Scandinavia, where the Vikings originated. The first raids in the British Isles were in the late eighth century, mainly on churches and monasteries (which were seen as centres of wealth).

Between the eighth and eleventh centuries, raiders and colonists from Scandinavia, mainly Danish and Norwegian, plundered western Europe including the British Isles. These raiders came to be known as the Vikings; the name is believed to derive from Scandinavia, where the Vikings originated. The first raids in the British Isles were in the late eighth century, mainly on churches and monasteries (which were seen as centres of wealth).

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

reports that the holy island of Lindisfarne

was sacked in AD 793. The raiding then virtually stopped for around forty years; but in about AD 835 it started becoming more regular.

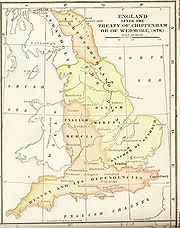

In the 860s, instead of raids the Danes mounted a full scale invasion; and 865 marked the arrival of an enlarged army that the Anglo-Saxons described as the Great Heathen Army

. This was reinforced in 871 by the Great Summer Army. Within ten years nearly all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fell to the invaders: Northumbria in 867, East Anglia in 869, and nearly all of Mercia in 874-7. Kingdoms, centres of learning, archives, and churches all fell before the onslaught from the invading Danes. Only the Kingdom of Wessex was able to survive. In March 878, the Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex, Alfred, with a few men, built a fortress at Athelney

, hidden deep in the marshes of Somerset. He used this as a base from which to harry the Vikings; and in May 878 he put together an army formed from the populations of Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire, which defeated the Viking army in battle at Edington. The Vikings retreated to their stronghold, and Alfred laid siege to it. Ultimately the Danes capitulated, and their leader Gunthrum

agreed to be baptised, and also to withdraw from Wessex. The formal ceremony was completed a few days later at Wedmore

. There followed a peace treaty

between Alfred and Guthrum, which had a variety of provisions, including defining the boundaries of the area to be ruled by the Danes (which became known as the Danelaw

) and those of Wessex. The Kingdom of Wessex controlled part of the Midlands and the whole of the South (apart from Cornwall, which was still held by the Britons), while the Danes held East Anglia and the North.

After the victory at Edington and resultant peace treaty, Alfred set about transforming his Kingdom of Wessex into a society on a full time war footing. He built a navy, reorganised the army, and set up a system of fortified towns known as burh

s. He mainly used old Roman cities for his burhs, as he was able to rebuild and reinforce their existing fortifications. To maintain the burhs, and the standing army, he set up a taxation system known as the Burghal Hidage

. These burhs (or burghs) operated as defensive structures. The Vikings were thereafter unable to cross large sections of Wessex: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that a Danish raiding party was defeated when it tried to attack the burh of Chichester. The burhs, although primarily designed as defensive structures, were also commercial centres, attracting traders and markets to a safe haven; and they provided a safe place for the king's moneyers and mints too.

A new wave of Danish invasions commenced in the year 891. This was the beginning of a war that lasted over three years. However, Alfred's new system of defence worked, and ultimately it wore the Danes down: they gave up and dispersed in the summer of 896.

Alfred will also be remembered as a literate king. He or his court commissioned the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written in Old English (rather than in Latin, which was the language of the European annals). Alfred's own literary output was mainly of translations, though he wrote introductions and amended manuscripts as well.

succeeded him. Alfred's son Edward, and his grandsons Æthelstan, Edmund I and Eadred, continued the policy of resistance against the Vikings. From AD 874-879 the western half of Mercia was ruled by Ceowulf II, who was succeeded by Æthelred. In 886/887 Æthelred married Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd. When Æthelred died in AD 911, his widow administered the Mercian province with the title "Lady of the Mercians". As commander of the Mercian army she worked with her brother, Edward the Elder, to win back the Mercian lands that were under Danish control. Edward and his successors made burhs a key element of their strategy, which enabled them to go on the offensive. Edward recaptured Essex in AD 913. Edward's son, Æthelstan, annexed Northumbria, and forced the kings of Wales to submit; then, at the battle of Brunanburh in 937, he defeated an alliance of the Scots, Danes and Vikings to become King of all England. But it was not only the Britons and the settled Danes who disliked being ruled by Wessex: so did some of the other Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Consequently, the death of a Wessex king would be followed by rebellion, particularly in Northumbria. But in 973 Alfred's great-grandson was crowned King of England and Emperor of Britain at Bath. On his coinage he had inscribed EDGAR REX ANGLORUM ('Edgar, King of the English'). Edgar's coronation was a magnificent affair, and many of its rituals and words could still be seen in the coronation of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

in 1953, though in English rather than Latin.

The presence of Danish and Norse settlers in the Danelaw had a lasting impact; the people there saw themselves as "armies" a hundred years after settlement: King Edgar issued a law code in AD 962 that was to include the people of Northumbria, so he addressed it to Earl Olac and all the army that live in that earldom. There are over 3,000 words in modern English

that have Scandinavian roots. Also, more than 1,500 place-names in England are Scandinavian in origin: for example, topographic names such as Howe, Norfolk

and Howe, North Yorkshire

are derived from the Old Norse

word haugr meaning hill, knoll or mound.

(the eldest) and his half-brother Æthelred. Edward was crowned king, at Kingston; but three years later he was assassinated by one of his half-brother's retainers, with the assistance of Æthelred's stepmother. Hence Æthelred II was crowned, and although he reigned for thirty eight years, one of the longest reigns in English history, he earned the name "Æthelred the Unready", as he proved to be one of England's most disastrous kings. William of Malmesbury

, writing in his "Chronicle of the kings of England" about one hundred years later, was scathing in his criticism of Æthelred, saying that he occupied the kingdom, rather than governed it.

Just as Æthelred was being crowned, the Danish King Gormsson

was trying to force Christianity onto his domain. Many of his subjects did not like this idea; and shortly before 988, Swein, his son, drove his father from the kingdom. The rebels, dispossessed at home, probably formed the first waves of raids on the English coast. The rebels did so well in their raiding that the Danish kings decided to take over the campaign themselves.

In 991 the Vikings sacked Ipswich, and the fleet made landfall near Maldon in Essex. The Danes demanded that the English pay a ransom, the English commander Byrhtnoth

refused; in the following Battle of Maldon

he was killed, and the English easily defeated. From then on the Vikings seem to raid anywhere at will; they were contemptuous of the lack of resistance from the English. Even the Alfredian systems of burh

s failed. Æthelred seems to have just hidden, out of range of the raiders.

By the 980s the kings of Wessex had a powerful grip on the coinage of the realm. It is reckoned there were about 300 moneyers, and 60 mints, around the country. Every five or six years the coinage in circulation would cease to be legal tender and new coins were issued. The system controlling the currency around the country was extremely sophisticated; this enabled the king to raise large sums of money if needed. The ability to raise large sums of money was needed after the battle of Maldon, as Æthelred decided that, rather than fight, he would pay ransom to the Danes in a system known as Danegeld

. As part of the ransom, a peace treaty was drawn up that was intended to stop the raids. However, rather than buying the Vikings off, payment of Danegeld only encouraged them to come back for more.

The Dukes of Normandy were quite happy to allow these Danish adventurers to use their ports for raids on the English coast. The result was that the courts of England and Normandy became increasingly hostile to each other. Eventually, Æthelred sought a treaty with the Normans, and ended up marrying Emma

, daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy

in the Spring of 1002, which was seen as an attempt to break the link between the raiders and Normandy.

Then, on St Brice's day

in November 1002, Danes living in England were slaughtered on the orders of Æthelred.

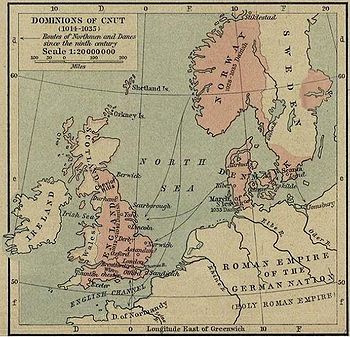

In the summer of 1013, Sven Forkbeard, King of Denmark, brought the Danish fleet to Sandwich, Kent. From there he went north to the Danelaw, where the locals immediately agreed to support him. He then struck south, forcing Æthelred into exile in Normandy (1013–1014). However, on 3 February 1014 Sven died suddenly. Æthelred, capitalising on Sven's death, returned to England and drove Sven's son, Cnut, back to Denmark, Cnut abandoning his allies in the process In 1015, Cnut launched a new campaign against England. Edmund fell out with his father Æthelred, and struck out on his own. Some of the English leaders decided to support Cnut rather than Æthelred, so ultimately Æthelred retreated to London. Before there was an engagement with the Danish army, Æthelred died and was replaced by Edmund.

The Danish army encircled and besieged London, but Edmund was able to escape and raised an army of loyalists. Edmund's army routed the Danes, but the success was short-lived: at the battle of Ashingdon

The Danish army encircled and besieged London, but Edmund was able to escape and raised an army of loyalists. Edmund's army routed the Danes, but the success was short-lived: at the battle of Ashingdon

the Danes were victorious and many of the English leaders were killed. However, Cnut and Edmund agreed to split the kingdom in two, with Edmund ruling Wessex and Cnut the rest. The following year (1017 AD) Edmund died in mysterious circumstances, probably murdered by Cnut or his supporters, and the English council (the witan

) confirmed Cnut as king of all England.

Cnut divided England into earldoms: most of these were allocated to nobles of Danish descent, but he made an Englishman earl of Wessex. The man he appointed was Godwin, who eventually became part of the extended royal family when he married the king's sister-in-law. In the summer of 1017, Cnut sent for Æthelred's widow, Emma, with the intention of marrying her. It seems that Emma agreed to marry the king on condition that he would limit the English succession to the children born of their union. Cnut already had a wife known as Ælfgifu of Northampton who bore him two sons, Svein and Harold Harefoot

. However it seems that the church regarded Ælfgifu as Cnut's concubine rather than his wife. As well as the two sons he had with Ælfgifu of Northampton, he had a further son with Emma, who was named Harthacnut.

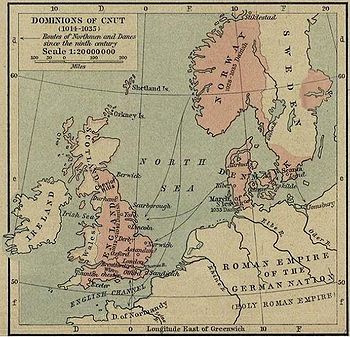

When Cnut's brother, Harald II, King of Denmark

, died in 1018 Cnut went to Denmark to secure that realm. Two years later, Cnut brought Norway under his control and he gave Ælfgifu of Northampton and their son Svein the job of governing it.

One of the outcomes of Cnut's marriage to Emma was to precipitate a succession crisis after his death in AD 1035. The throne was disputed between Ælfgifu's son, Harald Harefoot, and Emma's son, Harthacnut. Emma supported her son by Cnut, Harthacnut, rather than her sons by Æthelred. Her son by Æthelred, Edward, made an unsuccessful raid on Southampton; and his brother Alfred was murdered on an expedition to England in 1036. Emma fled to Bruges when Harald Harefoot became king of England; but when he died in 1040 Harthacnut was able to take over as king. Harthacnut quickly developed a reputation for imposing high taxes on England. He became so unpopular that Edward was invited to return from exile in Normandy to be recognised as Harthacnut's heir, and when Harthacnut died suddenly in 1042 (probably murdered), Edward (known to posterity as Edward the Confessor) became king.

Edward was supported by Earl Godwin of Wessex, and married the earl's daughter. However, this arrangement was seen as expedient, as Godwin had been implicated in the murder of Alfred, the king's brother. In 1051 one of Edward's in-laws, Eustace, arrived to take up residence in Dover; the men of Dover objected, and killed some of Eustace's men. When Godwin refused to punish them, the king, who had been unhappy with the Godwins for some time, summoned them to trial. Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was chosen to deliver the news to Godwin and his family. The Godwins fled rather than face trial.It is thought that at this time Edward offered the succession to, his cousin, William (duke) of Normandy; William (also known as

William the Conqueror, William the Bastard, or William I) did eventually become the king of England. The Godwins threatened to invade England and Edward is said to have wanted to fight, but at a Great Council meeting in Westminster Earl Godwin lay down all his weapons and asked the king to allow him to purge himself of all crimes. The king and Godwin were reconciled. The Godwins thus became the most powerful family in England after the king. On Godwin's death in 1053, his son Harold

succeeded to the earldom of Wessex; Harold's brothers Gyrth, Leofrine and Tostig

were given East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. Tostig was disliked by the Northumbrians for his harsh behaviour and was expelled to an exile in Flanders, in the process falling out with his brother Harold, who supported the king's line in backing the Northumbrians.

On 26 December 1065, Edward was taken ill He took to his bed and fell into a coma; at one point he woke and turned to Harold Godwinson and asked him to protect the Queen and the kingdom. On 5 January 1066 Edward the Confessor died, and Harold was declared king. The following day, 6 January 1066, Edward was buried and Harold crowned.Anglo Saxon Chronicle, 1066

Although Harold Godwinson had grabbed the crown of England, there were others who laid claim, primarily William, Duke of Normandy, who was cousin to Edward the Confessor through his aunt, Emma of Normandy. It is believed that Edward had promised the crown to William. Harold Godwinson had agreed to support William's claim after being imprisoned in Normandy, by Guy of Ponthieu. William had demanded and received Harold's release, then during his stay under William's protection it is claimed, by the Normans, that Harold swore a solemn oath of loyalty to William.

Harald Hardrada ('The Ruthless') of Norway also had a claim on England, through Cnut and his successors. He had, too, a further claim based on a pact between Hathacnut, King of Denmark (Cnut's son) and Magnus, King of Norway. Tostig, Harold's estranged brother, was the first to move, according to the medieval historian Orderic Vitalis

, he travelled to Normandy to enlist the help of William, Duke of Normandy, later to be known at William the Conqueror. William was not ready to get involved so Tostig sailed from the Contentin Peninsula, but because of storms ended up in Norway, where he successfully enlisted the help of Harold Hardrada. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle has a different version of the story, having Tostig land in the Isle of Wight in May 1066, then ravaging the English coast, before arriving at Sandwich, Kent. At Sandwich Tostig is said to have enlisted and press ganged sailors before sailing north where, after battling some of the northern earls and also visiting Scotland, he eventually joined Hardrada (possibly in Scotland or at the mouth of the river Tyne).

According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle (Manuscripts 'D' and 'E') Tostig became Hadrada's vassal, and then with 300 or so longships sailed up the Humber estuary bottling the English fleet in the river Swale and then landed at Riccall

According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle (Manuscripts 'D' and 'E') Tostig became Hadrada's vassal, and then with 300 or so longships sailed up the Humber estuary bottling the English fleet in the river Swale and then landed at Riccall

on the Ouse on 24th. September. They marched towards York, where they were confronted, at Fulford Gate, by the English forces that were under the command of the northern earls, Edwin and Morcar, the battle of Fulford Gate

followed, on 20th September, which was one of the most bloody battles of mediaeval times. The English forces were routed, though Edwin and Morcar escaped. The victors entered the city of York, exchanged hostages and were provisioned. Hearing the news whilst in London, Harold Godwinson force-marched a second English army to Tadcaster by the night of the 24th., and after catching Harald Hardrada by surprise, on the morning of the 25th. September, Harold achieved a total victory over the Scandinavian horde after a two day-long engagement at the Battle of Stamford Bridge

. Harold gave quarter to the survivors allowing them to leave in 20 ships.

Harold would have been celebrating his victory at Stamford Bridge on the night of 26/27 September 1066, while William of Normandy's invasion fleet set sail for England on the morning of 27 September 1066. Harold marched his army back down to the south coast where he met William's army, at a place now called Battle

just outside Hastings. Harold was killed when he fought and lost the Battle of Hastings

on 14th October 1066.

The Battle of Hastings virtually destroyed the Godwin dynasty. Harold and his brothers Gyrth and Leofwine were dead on the battlefield, as was their uncle Ælfwig, Abbot of Newminster. Tostig had been killed at Stamford Bridge. Wulfnoth was a hostage of William the Conqueror. The Godwin women who remained were either dead or childless.

William marched on London. The city leaders surrendered the kingdom to him, and he was crowned at Westminster Abbey, Edward the Confessor's new church, on Christmas Day 1066. It took William a further ten years to consolidate his kingdom, any opposition was suppressed ruthlessly, and in a particularly brutal incident known as the 'Harrying of the North'

, William issued orders to lay waste the north and burn all the cattle, crops and farming equipment and to poison the earth. According to Orderic Vitalis

the

Anglo-Norman chronicler over one hundred thousand people died of starvation. Figures based on the returns for the Domesday Book

estimate that the overall population of England in 1086 was about 2.25 million, so the figure of one hundred thousand deaths, due to starvation, would have been a huge proportion of the population.

By the time of William's death in 1087, those who had been England's Anglo-Saxon rulers were dead, exiled or had joined the ranks of the peasantry. It was estimated that only about 8 percent of the land was under Anglo-Saxon control. Nearly all the Anglo-Saxon cathedrals and abbeys of any note had been demolished and replaced with Norman-style architecture by AD 1200.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, lasting from the end of Roman occupation

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

and establishment of Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon is a term used by historians to designate the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled the south and east of Great Britain beginning in the early 5th century AD, and the period from their creation of the English nation to the Norman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Era denotes the period of...

kingdoms in the 5th century until the Norman conquest of England

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

in 1066 by William the Conqueror. Anglo-Saxon is a general term referring to the Germanic peoples

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

who came to Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries, including Angles

Angles

The Angles is a modern English term for a Germanic people who took their name from the ancestral cultural region of Angeln, a district located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany...

, Saxons

Saxons

The Saxons were a confederation of Germanic tribes originating on the North German plain. The Saxons earliest known area of settlement is Northern Albingia, an area approximately that of modern Holstein...

, Frisii

Frisii

The Frisii were an ancient Germanic tribe living in the low-lying region between the Zuiderzee and the River Ems. In the Germanic pre-Migration Period the Frisii and the related Chauci, Saxons, and Angles inhabited the Continental European coast from the Zuyder Zee to south Jutland...

and Jutes

Jutes

The Jutes, Iuti, or Iutæ were a Germanic people who, according to Bede, were one of the three most powerful Germanic peoples of their time, the other two being the Saxons and the Angles...

. The term also refers to the language spoken at the time in England, which is now called Old English, and to the culture of the era, which has long attracted popular and scholarly attention.

Until the 9th century Anglo-Saxon England was dominated by the Heptarchy

Heptarchy

The Heptarchy is a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central Great Britain during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, conventionally identified as seven: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and Wessex...

, the kingdoms of Northumbria

Northumbria

Northumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

, Mercia

Mercia

Mercia was one of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was centred on the valley of the River Trent and its tributaries in the region now known as the English Midlands...

, East Anglia, Essex

Kingdom of Essex

The Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...

, Kent

Kingdom of Kent

The Kingdom of Kent was a Jutish colony and later independent kingdom in what is now south east England. It was founded at an unknown date in the 5th century by Jutes, members of a Germanic people from continental Europe, some of whom settled in Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans...

, Sussex

Kingdom of Sussex

The Kingdom of Sussex or Kingdom of the South Saxons was a Saxon colony and later independent kingdom of the Saxons, on the south coast of England. Its boundaries coincided in general with those of the earlier kingdom of the Regnenses and the later county of Sussex. A large part of its territory...

and Wessex

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

. In terms of religion the kingdoms followed Anglo-Saxon paganism during the early period, but converted to Christianity during the 7th century. Paganism had a final stronghold in a period of Mercian hegemony during the 640s, ending with the death of Penda of Mercia

Penda of Mercia

Penda was a 7th-century King of Mercia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom in what is today the English Midlands. A pagan at a time when Christianity was taking hold in many of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Penda took over the Severn Valley in 628 following the Battle of Cirencester before participating in the...

in 655.

Facing the threat of Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

invasions, the House of Wessex

House of Wessex

The House of Wessex, also known as the House of Cerdic, refers to the family that ruled a kingdom in southwest England known as Wessex. This House was in power from the 6th century under Cerdic of Wessex to the unification of the Kingdoms of England....

became dominant during the 9th century, under the rule of Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

. During the 10th century, the individual kingdoms unified under the rule of Wessex into the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

, which stood opposed to the Danelaw

Danelaw

The Danelaw, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , is a historical name given to the part of England in which the laws of the "Danes" held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. It is contrasted with "West Saxon law" and "Mercian law". The term has been extended by modern historians to...

, the Viking kingdoms established from the 9th century in the north and east of England. The Kingdom of England fell in the Viking invasion from Denmark in 1013 and was ruled by the House of Denmark

House of Denmark

The House of Denmark refers to the Danish kings of England, who ruled England from 1013 to 1014 and 1016 to 1042.In 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard, already the king of Denmark and of Norway, overthrew King Æthelred the Unready of the House of Wessex. Sweyn had first invaded England in 1003 to avenge the...

until 1042, when the Anglo-Saxon House of Wessex

House of Wessex

The House of Wessex, also known as the House of Cerdic, refers to the family that ruled a kingdom in southwest England known as Wessex. This House was in power from the 6th century under Cerdic of Wessex to the unification of the Kingdoms of England....

was restored. The last Anglo-Saxon king, Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

, was killed in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings

Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings occurred on 14 October 1066 during the Norman conquest of England, between the Norman-French army of Duke William II of Normandy and the English army under King Harold II...

.

Historical context

As the Roman occupation of Britain was coming to an end, Constantine IIIConstantine III (usurper)

Flavius Claudius Constantinus, known in English as Constantine III was a Roman general who declared himself Western Roman Emperor in Britannia in 407 and established himself in Gaul. Recognised by the Emperor Honorius in 409, collapsing support and military setbacks saw him abdicate in 411...

withdrew the remains of the army, in reaction to the barbarian invasion of Europe. The Romano-British leaders were faced with an increasing security problem from sea borne raids, particularly by Picts

Picts

The Picts were a group of Late Iron Age and Early Mediaeval people living in what is now eastern and northern Scotland. There is an association with the distribution of brochs, place names beginning 'Pit-', for instance Pitlochry, and Pictish stones. They are recorded from before the Roman conquest...

on the East coast of England. The expedient adopted by the Romano-British leaders was to enlist the help of Anglo-Saxon mercenaries (known as foederati

Foederati

Foederatus is a Latin term whose definition and usage drifted in the time between the early Roman Republic and the end of the Western Roman Empire...

), to whom they ceded territory. In about AD 442 the Anglo-Saxons mutinied, apparently because they had not been paid. The British responded by appealing to the Roman commander of the Western empire Aëtius

Flavius Aëtius

Flavius Aëtius , dux et patricius, was a Roman general of the closing period of the Western Roman Empire. He was an able military commander and the most influential man in the Western Roman Empire for two decades . He managed policy in regard to the attacks of barbarian peoples pressing on the Empire...

for help (a document known as the Groans of the Britons

Groans of the Britons

The Groans of the Britons is the name of the final appeal made by the Britons to the Roman military for assistance against barbarian invasion. The appeal is first referenced in Gildas' 6th-century De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae; Gildas' account was later repeated in Bede's Historia...

), even though Honorius

Honorius (emperor)

Honorius , was Western Roman Emperor from 395 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and brother of the eastern emperor Arcadius....

, the Western Roman Emperor, had written to the British civitas

Civitas

In the history of Rome, the Latin term civitas , according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the cives, or citizens, united by law . It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities on the one hand and rights of citizenship on the other...

in or about AD 410 telling them to look to their own defence. There then followed several years of fighting between the British and the Anglo-Saxons. The fighting continued until around AD 500, when, at the Battle of Mount Badon

Battle of Mons Badonicus

The Battle of Mons Badonicus was a battle between a force of Britons and an Anglo-Saxon army, probably sometime between 490 and 517 AD. Though it is believed to have been a major political and military event, there is no certainty about its date, location or the details of the fighting...

, the Britons inflicted a severe defeat on the Anglo-Saxons.

Sources

There is a wide range of source material pertaining to Anglo-Saxon England.There are literary sources:

- Historians in the Middle AgesEnglish historians in the Middle AgesHistorians of England in the Middle Ages helped to lay the groundwork for modern historical historiography, providing vital accounts of the early history of England, Wales and Normandy, its cultures, and revelations about the historians themselves....

- The Anglo-Saxon ChronicleAnglo-Saxon ChronicleThe Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

, a series of documents that charted Anglo-Saxon history from the mid-fifth century until 1066 (although one version extends till 1154). These were commissioned during the reign of Alfred the GreatAlfred the GreatAlfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

in the 9th century.

Other written sources include:

- Law codesAnglo-Saxon lawAnglo-Saxon law is a body of written rules and customs that were in place during the Anglo-Saxon period in England, before the Norman conquest. This body of law, along with early Scandinavian law and continental Germanic law, descended from a family of ancient Germanic custom and legal thought...

. For example, there were four sets that originated in the seventh century; the first three were issued by the Kings of Kent: Æthelberht I, Hlothhere, EadricEadric of KentEadric was a King of Kent . He was the son of Ecgberht I.Eadric was for a time co-ruler alongside his uncle Hlothhere, and a code of laws issued in both their names has survived. However, Eadric eventually revolted and defeated Hlothhere with the aid of the South Saxons...

and Wihtred: the Law of ÆthelberhtLaw of ÆthelberhtThe Law of Æthelberht is a set of legal provisions written in Old English, probably dating to the early 7th century. It originates in the kingdom of Kent, and is the first Germanic-language law code...

, the Law of Hlothhere and EadricLaw of Hlothhere and EadricThe Law of Hlothhere and Eadric is an Anglo-Saxon legal text. It is attributed to the Kentish kings Hloþhere and Eadric , and thus is believed to date to the second half of the 7th century. It is one of three extant early Kentish codes, along with the early 7th-century Law of Æthelberht and the...

and the Law of WihtredLaw of WihtredThe Law of Wihtred is an early English legal text attributed to the Kentish king Wihtred . It is believed to date to the final decade of the 7th century and is the last of three Kentish legal texts, following the Law of Æthelberht and the Law of Hlothhere and Eadric...

. The fourth was that of Ine of WessexIne of WessexIne was King of Wessex from 688 to 726. He was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecessor, Cædwalla, who had brought much of southern England under his control and expanded West Saxon territory substantially...

. - The ChartersAnglo-Saxon ChartersAnglo-Saxon charters are documents from the early medieval period in Britain which typically make a grant of land or record a privilege. The earliest surviving charters were drawn up in the 670s; the oldest surviving charters granted land to the Church, but from the eighth century surviving...

were a series of legal documents that were primarily (although not exclusively) grants of land to individuals by the kings of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. - Biographies, hagiographyHagiographyHagiography is the study of saints.From the Greek and , it refers literally to writings on the subject of such holy people, and specifically to the biographies of saints and ecclesiastical leaders. The term hagiology, the study of hagiography, is also current in English, though less common...

, letters and poetry. - Domesday BookDomesday BookDomesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

. Although compiled in 1086, after the Norman Conquest, one of its functions was to ascertain who held what land and the taxes due under Edward the ConfessorEdward the ConfessorEdward the Confessor also known as St. Edward the Confessor , son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066....

.

Non-literary sources include:

- ArchaeologyAnglo-Saxon archaeologyThe archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England:*Anglo-Saxon hoards*Anglo-Saxon art**Sutton Hoo**Staffordshire Hoard**Canterbury-St Martin's hoard*Anglo-Saxon numismatics*Anglo-Saxon glass*Anglo-Saxon architecture-Burial:...

. Anglo-Saxon settlement can be traced by following burial patterns and land usage. - ArchitectureAnglo-Saxon architectureAnglo-Saxon architecture was a period in the history of architecture in England, and parts of Wales, from the mid-5th century until the Norman Conquest of 1066. Anglo-Saxon secular buildings in Britain were generally simple, constructed mainly using timber with thatch for roofing...

- Toponymy

- Numismatics

- geneticsGenetic history of the British IslesThe genetic history of the British Isles is the subject of research within the larger field of human population genetics. It has developed in parallel with DNA testing technologies capable of identifying genetic similarities and differences between populations...

Migration and the formation of kingdoms (400–600)

Cohort (military unit)

A cohort was the basic tactical unit of a Roman legion following the reforms of Gaius Marius in 107 BC.-Legionary cohort:...

of Batavians

Batavians

The Batavi were an ancient Germanic tribe, originally part of the Chatti, reported by Tacitus to have lived around the Rhine delta, in the area that is currently the Netherlands, "an uninhabited district on the extremity of the coast of Gaul, and also of a neighbouring island, surrounded by the...

attached to the 14th Legion

Legio XIV Gemina

Legio quarta decima Gemina was a legion of the Roman Empire, levied by Julius Caesar in late 58 B.C. The cognomen Gemina suggests that the legion resulted from fusion of two previous ones, one of them being the Fourteenth legion that fought in the Battle of Alesia, the other being the Martia ...

in the original invasion force under Aulus Plautius

Aulus Plautius

Aulus Plautius was a Roman politician and general of the mid-1st century. He began the Roman conquest of Britain in 43, and became the first governor of the new province, serving from 43 to 47.-Career:...

in AD 43. There is a hypothesis that some of the native tribes

Belgae

The Belgae were a group of tribes living in northern Gaul, on the west bank of the Rhine, in the 3rd century BC, and later also in Britain, and possibly even Ireland...

, identified as Britons by the Romans, may have been Germanic language speakers although most modern scholars refute this.

It was quite common for Rome to swell its legions with foederati recruited from the German homelands. This practice also extended to the army serving in Britain, and graves of these mercenaries, along with their families, can be identified in the Roman cemeteries of the period. The migration continued with the departure of the Roman army, when Anglo-Saxons were recruited to defend Britain; and also during the period of the Anglo-Saxon first rebellion of AD 442.

If the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

is to be believed, the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which eventually merged to become England were founded when small fleets of three or five ships of invaders arrived at various points around the coast of England to fight the Sub-Roman British, and conquered their lands. As Margaret Gelling

Margaret Gelling

Margaret Joy Gelling, OBE was an English toponymist, Fellow of St Hilda's College, Oxford, and member of the Society of Antiquaries of London and the British Academy....

points out, in the context of place name evidence, what actually happened between the departure of the Romans and the coming of the Normans is the subject of much disagreement by historians.

The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons into Britain can be seen in the context of a general movement of German people around Europe between the years 300 and 700, known as the Migration period

Migration Period

The Migration Period, also called the Barbarian Invasions , was a period of intensified human migration in Europe that occurred from c. 400 to 800 CE. This period marked the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages...

(also called the Barbarian Invasions or Völkerwanderung). In the same period there were migrations of Britons to the Armorican peninsula (Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

and Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

in modern day France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

): initially around AD 383 during Roman rule, but also c. 460 and in the 540s and 550s; the 460s migration is thought to be a reaction to the fighting during the Anglo-Saxon mutiny between about 450 to 500, as was the migration to Britonia

Britonia

Britonia is the historical name of a settlement in Galicia which was settled in the late 5th and early 6th centuries AD by Romano-Britons escaping the advancing Anglo-Saxons who were conquering Britain at the time...

(modern day Galicia, in northwest Spain) at about the same time.

The historian Peter Hunter-Blair

Peter Hunter Blair

Peter Hunter Blair was an English academic and historian specializing in the Anglo-Saxon period. In 1969 he married Pauline Clarke. She edited his Anglo-Saxon Northumbria in 1984....

expounded what is now regarded as the traditional view of the Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain. He suggested a mass immigration, fighting and driving the Sub-Roman Britons off their land and into the western extremities of the islands, and into the Breton and Iberian peninsulas.

The modern view is of co-existence between the British and the Anglo-Saxons.

Discussions and analysis

Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain was the invasion and migration of Germanic peoples from continental Europe to Great Britain during the Early Middle Ages, specifically the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain after the demise of Roman rule in the 5th century.The stimulus, progression and...

still continue on the size of the migration, and whether it was a small elite band of Anglo-Saxons who came in and took over the running of the country, or a mass migration of peoples who overwhelmed the Britons.

After the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons by the British at the Battle of Mount Badon in c. AD 500, where according to Gildas

Gildas

Gildas was a 6th-century British cleric. He is one of the best-documented figures of the Christian church in the British Isles during this period. His renowned learning and literary style earned him the designation Gildas Sapiens...

the British resistance was led by a man called Ambrosius Aurelianus

Ambrosius Aurelianus

Ambrosius Aurelianus, ; called Aurelius Ambrosius in the Historia Regum Britanniae and elsewhere, was a war leader of the Romano-British who won an important battle against the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th century, according to Gildas...

, Anglo-Saxon migration was temporarly stemmed. Gildas said that this was "forty-four years and one month" after the arrival of the Saxons, and was also the year of his birth. He said that a time of great prosperity followed. But, despite the lull, the Anglo-Saxons took control of Sussex, Kent, East Anglia and part of Yorkshire; while the West Saxons founded a kingdom in Hampshire under the leadership of Cerdic, around AD 520. However, it was to be 50 years before the Anglo-Saxons began further major advances. In the intervening years the Britons exhausted themselves with civil war, internal disputes, and general unrest: which was the inspiration behind Gildas's book De Excidio Britanniae (The Ruin of Britain).

The next major campaign against the Britons was in AD 577, led by Cealin, king of Wessex, whose campaigns succeeded in taking Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath (known as the Battle of Dyrham). This expansion of Wessex ended abruptly when the Anglo-Saxons started fighting amongst themselves, and resulted in Cealin eventually having to retreat to his original territory. He was then replaced by Ceol (who was possibly his nephew): Cealin was killed the following year, but the annals do not specify by whom. Cirencester subsequently became an Anglo-Saxon kingdom under the overlordship of the Mercians, rather than Wessex.

Heptarchy and Christianisation (7th and 8th centuries)

By AD 600, a new order was developing, of kingdoms and sub-Kingdoms. Henry of Huntingdon (a medieval historian) conceived the idea of the HeptarchyHeptarchy

The Heptarchy is a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central Great Britain during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, conventionally identified as seven: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and Wessex...

, which consisted of the seven principal Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Anglo-Saxon England heptarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

in Anglo-Saxon England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

were:

- WessexWessexThe Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

- East AngliaKingdom of the East AnglesThe Kingdom of East Anglia, also known as the Kingdom of the East Angles , was a small independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom that comprised what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens...

- MerciaMerciaMercia was one of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was centred on the valley of the River Trent and its tributaries in the region now known as the English Midlands...

- NorthumbriaNorthumbriaNorthumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

, including sub-kingdoms BerniciaBerniciaBernicia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England....

and Deira

Minor kingdoms:

- KentKingdom of KentThe Kingdom of Kent was a Jutish colony and later independent kingdom in what is now south east England. It was founded at an unknown date in the 5th century by Jutes, members of a Germanic people from continental Europe, some of whom settled in Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans...

- SussexKingdom of SussexThe Kingdom of Sussex or Kingdom of the South Saxons was a Saxon colony and later independent kingdom of the Saxons, on the south coast of England. Its boundaries coincided in general with those of the earlier kingdom of the Regnenses and the later county of Sussex. A large part of its territory...

- EssexKingdom of EssexThe Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...

Other minor kingdoms and territories

- Isle of Wight, (Wihtwara)

- The MeonwaraMeonwaraMeonwara or Meonsæte is the name of a people of probable Jutish origin who colonised what is now known as the Meon Valley, an area in southern Hampshire, England, during the late 5th century and early 6th century.-Area of settlement:...

The Meon Valley area of Hampshire - Surrey

- Kingdom of the Iclingas, a precursor state to Mercia

- LindseyKingdom of LindseyLindsey or Linnuis is the name of a petty Anglo-Saxon kingdom, absorbed into Northumbria in the 7th century.It lay between the Humber and the Wash, forming its inland boundaries from the course of the Witham and Trent rivers , and the Foss Dyke between...

- The HwicceHwicceThe Hwicce were one of the peoples of Anglo-Saxon England. The exact boundaries of their kingdom are uncertain, though it is likely that they coincided with those of the old Diocese of Worcester, founded in 679–80, the early bishops of which bore the title Episcopus Hwicciorum...

- Magonsæte

- Pecsæte

- Wreocensæte

- Tomsæte

- HaestingasHaestingasThe Haestingas, or alternatively Heastingas or Hæstingas, were one of the tribes of Anglo-Saxon Britain. The Kingdom of Haestingas was located in modern-day Sussex, and was one of the minor sub-kingdoms of the Heptarchy.- History :...

- Middle AnglesMiddle AnglesThe Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxon period.-Origins and territory:...

At the end of the 6th century the most powerful ruler in England was Æthelberht of Kent, whose lands extended north to the Humber. In the early years of the 7th century, Kent and East-Anglia were the leading English kingdoms. After the death of Æthelberht in 616, Rædwald of East Anglia became the most powerful leader south of the Humber.

Following the death of Æthelfrith of Northumbria, Rædwald provided military assistance to the Deiran Edwin

Edwin of Northumbria

Edwin , also known as Eadwine or Æduini, was the King of Deira and Bernicia – which later became known as Northumbria – from about 616 until his death. He converted to Christianity and was baptised in 627; after he fell at the Battle of Hatfield Chase, he was venerated as a saint.Edwin was the son...

, in his struggle to take over the two dynasties of Deira

Deira

Deira was a kingdom in Northern England during the 6th century AD. Itextended from the Humber to the Tees, and from the sea to the western edge of the Vale of York...

and Bernicia

Bernicia

Bernicia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England....

in the unified kingdom of Northumbria.

On the death of Rædwald, Edwin was able to pursue a grand plan to expand Northumbrian power.

The growing strength of Edwin of Northumbria forced the Anglo-Saxon Mercians under Penda into an alliance with the Welsh King Cadwallon of Gwynedd, and together they invaded Edwin's lands and defeated and killed him at the Battle of Hatfield Chase

Battle of Hatfield Chase

The Battle of Hatfield Chase was fought on October 12, 633 at Hatfield Chase near Doncaster, Yorkshire, in Anglo-Saxon England between the Northumbrians under Edwin and an alliance of the Welsh of Gwynedd under Cadwallon ap Cadfan and the Mercians under Penda. The site was a marshy area about 8...

in 633. Their success was short-lived, as Oswald (one of the dead King of Northumbria, Æthelfrith's, sons) defeated and killed Cadwallon at Heavenfield near Hexham. In less than a decade Penda again waged war against Northumbria, and killed Oswald in battle during AD 642. His brother Oswiu was chased to the northern extremes of his kingdom. However, Oswiu killed Penda shortly after, and Mercia spent the rest of the 7th and all of the 8th century fighting the kingdom of Powys. The war reached its climax during the reign of Offa

Offa

Offa may refer to:Two kings of the Angles, who are often confused:*Offa of Angel , on the continent*Offa of Mercia , in Great BritainA king of Essex:*Offa of Essex A town in Nigeria:* Offa, Nigeria...

of Mercia, who is remembered for the construction of a 150 mile long dyke

Offa's Dyke

Offa's Dyke is a massive linear earthwork, roughly followed by some of the current border between England and Wales. In places, it is up to wide and high. In the 8th century it formed some kind of delineation between the Anglian kingdom of Mercia and the Welsh kingdom of Powys...

which formed the Wales/ England border. It is not clear whether this was a boundary line or a defensive position. The ascendency of the Mercians came to an end in AD 825, when they were soundly beaten under Beornwulf at the Battle of Ellendun by Egbert of Wessex.

Christianity was introduced into the British Isles during the Roman occupation. The early Christian Berber

Berber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

author, Tertullian

Tertullian

Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus, anglicised as Tertullian , was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He is the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of Latin Christian literature. He also was a notable early Christian apologist and...

, writing in the third century, said that "Christianity could even be found in Britain." The Roman Emperor Constantine

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

(AD 306-337), granted official tolerance to Christianity with the Edict of Milan

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan was a letter signed by emperors Constantine I and Licinius that proclaimed religious toleration in the Roman Empire...

in AD 313. Then, in the reign of Emperor Theodosius "the Great"

Theodosius I

Theodosius I , also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from 379 to 395. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and the western halves of the Roman Empire. During his reign, the Goths secured control of Illyricum after the Gothic War, establishing their homeland...

(AD 378-395), Christianity was made the official religion of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

It is not entirely clear how many Britons would have been Christian when the pagan Anglo-Saxons arrived. There had been attempts to evangelise the Irish by Pope Celestine in AD 431. However, it was Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick was a Romano-Briton and Christian missionary, who is the most generally recognized patron saint of Ireland or the Apostle of Ireland, although Brigid of Kildare and Colmcille are also formally patron saints....

who is credited with converting the Irish en-masse. A Christian Ireland then set about evangelising the rest of the British Isles, and Columba

Columba

Saint Columba —also known as Colum Cille , Colm Cille , Calum Cille and Kolban or Kolbjørn —was a Gaelic Irish missionary monk who propagated Christianity among the Picts during the Early Medieval Period...

was sent to found a religious community in Iona, off the west coast of Scotland. Then Aidan

Aidan of Lindisfarne

Known as Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne, Aidan the Apostle of Northumbria , was the founder and first bishop of the monastery on the island of Lindisfarne in England. A Christian missionary, he is credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria. Aidan is the Anglicised form of the original Old...

was sent from Iona to set up his see in Northumbria, at Lindisfarne, between AD 635-651. Hence Northumbria was converted by the Celtic (Irish) church.

Bede is very uncomplimentary about the indigenous British clergy: in his Historia ecclesiastica he complains of their unspeakable crimes, and that they did not preach the faith to the Angles or Saxons. Pope Gregory sent Augustine

Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury was a Benedictine monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597...

in AD 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons, but Bede says the British clergy refused to help Augustine in his mission. Despite Bede's complaints, it is now believed that the Britons played an important role in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. On arrival in the south east of England in AD 597, Augustine was given land by King Æthelberht of Kent to build a church; so in 597 Augustine built the church and founded the See at Canterbury. He baptised Æthelberht in 601, then continued with his mission to convert the English. Most of the north and east of England had already been evangelised by the Irish Church. However, Sussex and the Isle of Wight remained mainly pagan until the arrival of Saint Wilfrid

Wilfrid

Wilfrid was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Gaul, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and became the abbot of a newly founded monastery at Ripon...

, the exiled Archbishop of York, who converted Sussex around AD 681 and the Isle of Wight in 683.

It remains unclear what 'conversion' actually meant. The ecclesiastical writers tended to declare a territory as 'converted' merely because the local king had agreed to be baptised, regardless of whether, in reality, he actually adopted Christian practices; and regardless, too, of whether the general population of his kingdom did. When churches were built, they tended to include pagan as well as Christian symbols, evidencing an attempt to reach out to the pagan Anglo-Saxons, rather than demonstrating that they were already converted.

Even after Christianity had been set up in all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, there was friction between the followers of the Roman rites and the Irish rites, particularly over the date on which Easter fell and the way monks cut their hair. In AD 664 a conference was held at Whitby Abbey (known as the Whitby Synod

Synod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby was a seventh century Northumbriansynod where King Oswiu of Northumbria ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Rome, rather than the customs practised by Iona and its satellite institutions...

) to decide the matter; Saint Wilfrid was an advocate for the Roman rites and Bishop Colmán

Colmán of Lindisfarne

Colmán of Lindisfarne also known as Saint Colmán was Bishop of Lindisfarne from 661 until 664. He succeeded Aidan and Finan. Colman resigned the Bishopric of Lindisfarne after the Synod of Whitby called by King Oswiu of Northumbria decided to calculate Easter using the method of the First...

for the Irish rites. Wilfrid's argument won the day and Colmán and his party returned to Ireland in their bitter disappointment. The Roman rites were adopted by the English church, although they were not universally accepted by the Irish Church.

Viking challenge and the rise of Wessex (9th century)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

reports that the holy island of Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne is a tidal island off the north-east coast of England. It is also known as Holy Island and constitutes a civil parish in Northumberland...

was sacked in AD 793. The raiding then virtually stopped for around forty years; but in about AD 835 it started becoming more regular.

In the 860s, instead of raids the Danes mounted a full scale invasion; and 865 marked the arrival of an enlarged army that the Anglo-Saxons described as the Great Heathen Army

Great Heathen Army

The Great Heathen Army, also known as the Great Army or the Great Danish Army, was a Viking army originating in Denmark which pillaged and conquered much of England in the late 9th century...

. This was reinforced in 871 by the Great Summer Army. Within ten years nearly all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fell to the invaders: Northumbria in 867, East Anglia in 869, and nearly all of Mercia in 874-7. Kingdoms, centres of learning, archives, and churches all fell before the onslaught from the invading Danes. Only the Kingdom of Wessex was able to survive. In March 878, the Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex, Alfred, with a few men, built a fortress at Athelney

Athelney

Athelney is located between the villages of Burrowbridge and East Lyng in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, England. The area is known as the Isle of Athelney, because it was once a very low isolated island in the 'very great swampy and impassable marshes' of the Somerset Levels. Much of the...

, hidden deep in the marshes of Somerset. He used this as a base from which to harry the Vikings; and in May 878 he put together an army formed from the populations of Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire, which defeated the Viking army in battle at Edington. The Vikings retreated to their stronghold, and Alfred laid siege to it. Ultimately the Danes capitulated, and their leader Gunthrum

Guthrum the Old

Guthrum , christened Æthelstan, was King of the Danish Vikings in the Danelaw. He is mainly known for his conflict with Alfred the Great.-Guthrum, founder of the Danelaw:...

agreed to be baptised, and also to withdraw from Wessex. The formal ceremony was completed a few days later at Wedmore

Treaty of Wedmore

The Peace of Wedmore is a term used by historians for an event referred to by the monk Asser in his Life of Alfred, outlining how in 878 the Viking leader Guthrum was baptised and accepted Alfred as his adoptive father. Guthrum agreed to leave Wessex and a "Treaty of Wedmore" is often assumed by...

. There followed a peace treaty

Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum

The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum is an agreement between Alfred of Wessex and Guthrum, the Viking ruler of East Anglia. Its date is uncertain, but must have been between 878 and 890. The treaty is one of the few existing documents of Alfred's reign; it survives in Old English in Corpus Christi...

between Alfred and Guthrum, which had a variety of provisions, including defining the boundaries of the area to be ruled by the Danes (which became known as the Danelaw

Danelaw

The Danelaw, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , is a historical name given to the part of England in which the laws of the "Danes" held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. It is contrasted with "West Saxon law" and "Mercian law". The term has been extended by modern historians to...

) and those of Wessex. The Kingdom of Wessex controlled part of the Midlands and the whole of the South (apart from Cornwall, which was still held by the Britons), while the Danes held East Anglia and the North.