History of research ships

Encyclopedia

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

's Endeavour

HM Bark Endeavour

HMS Endeavour, also known as HM Bark Endeavour, was a British Royal Navy research vessel commanded by Lieutenant James Cook on his first voyage of discovery, to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771....

, the essentials of what today we would call a research ship are clearly apparent. In 1766, the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

hired Cook to travel to the Pacific Ocean

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

to observe and record the transit of Venus

Transit of Venus

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black disk moving across the face of the Sun...

across the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

. The Endeavour was a sturdy boat, well designed and equipped for the ordeals she would face, and fitted out with facilities for her "research" personnel, Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

. And, as is common with contemporary research vessels, Endeavour carried out more than one kind of research, including comprehensive Hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/drilling and related disciplines. Strong emphasis is placed on soundings, shorelines, tides, currents, sea floor and submerged...

work.

Some other notable early research vessels were HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle was a Cherokee-class 10-gun brig-sloop of the Royal Navy. She was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard on the River Thames, at a cost of £7,803. In July of that year she took part in a fleet review celebrating the coronation of King George IV of the United Kingdom in which...

, RV Calypso, HMS Challenger

HMS Challenger (1858)

HMS Challenger was a steam-assisted Royal Navy Pearl-class corvette launched on 13 February 1858 at the Woolwich Dockyard. She was the flagship of the Australia Station between 1866 and 1870....

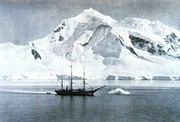

, and the Endurance

Endurance (1912 ship)

The Endurance was the three-masted barquentine in which Sir Ernest Shackleton sailed for the Antarctic on the 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition...

and Terra Nova

Terra Nova (ship)

The Terra Nova was built in 1884 for the Dundee whaling and sealing fleet. She worked for 10 years in the annual seal fishery in the Labrador Sea, proving her worth for many years before she was called upon for expedition work.Terra Nova was ideally suited to the polar regions...

.

19th century

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

and South

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

Poles. The search operations for the lost Franklin expedition were barely forgotten as Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

set new scientific tasks for the Arctic Ocean. In 1868, the Swedish ship Sofia carried out temperature measurements and oceanographic observation in the sea area around Svalbard

Svalbard

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic, constituting the northernmost part of Norway. It is located north of mainland Europe, midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. The group of islands range from 74° to 81° north latitude , and from 10° to 35° east longitude. Spitsbergen is the...

. During this year the Greenland, built in Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

, operated in the same area under the German command of Carl Koldeway. In 1868 to 1869, the ship owner A. Rosenthal gave scientists the opportunity to come aboard on his whaling trips and by 1869, the ship Germania, which was escorted by the Hansa and led the Second German North Polar Expedition, was built. The Germania returned safely from the expedition and was used later for further research. The Hansa, in contrast, was crushed by the ice and sunk. In 1874, the Austrian-Hungarian Tegetthoff as well as the American schooner Polaris under the command of Captain Hull met the same fate.

The Royal Navy ships Alert

HMS Alert (1856)

HMS Alert was a 17-gun wooden screw sloop of the Cruizer class of the Royal Navy, launched in 1856 and broken up in 1894. She was the eleventh ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name , and was noted for her Arctic exploration work; in 1876 she reached a record latitude of 82°N.-Construction:The...

and Discovery

HMS Discovery (1874)

HMS Discovery was a wooden screw storeship, formerly the whaling ship Bloodhound. She was purchased in 1874 for the British Arctic Expedition of 1875–1876 and was sold in 1902.-Design and Construction:...

of the British Arctic Expedition of 1875-76

British Arctic Expedition

The British Arctic Expedition of 1875-1876, led by Sir George Strong Nares, was sent by the British Admiralty to attempt to reach the North Pole via Smith Sound. Two ships, HMS Alert and HMS Discovery , sailed from Portsmouth on 29 May 1875...

were more successful. In 1875 they left Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

in order to cross the Arctic Ocean

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions...

and reach as close as possible to the pole. Although they did not reach the pole itself they brought plenty of precious observations back. During these years, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld

Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld

Freiherr Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld , also known as A. E. Nordenskioeld was a Finnish baron, geologist, mineralogist and arctic explorer of Finnish-Swedish origin. He was a member of the prominent Finland-Swedish Nordenskiöld family of scientists...

's discovery of the Northeast Passage

Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route is a shipping lane officially defined by Russian legislation from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean specifically running along the Russian Arctic coast from Murmansk on the Barents Sea, along Siberia, to the Bering Strait and Far East. The entire route lies in Arctic...

with the Vega

Vega (ship)

SS Vega was a Swedish barque, built in Bremerhaven Germany in 1872. She was the first ship to complete a voyage through the Northeast Passage, and the first vessel to circumnavigate the Eurasian continent.-Construction:...

outstood all other expeditions.

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a...

's famous Fram

Fram

Fram is a ship that was used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912...

took deep-sea soundings and carried out hydrographical

Hydrography

Hydrography is the measurement of the depths, the tides and currents of a body of water and establishment of the sea, river or lake bed topography and morphology. Normally and historically for the purpose of charting a body of water for the safe navigation of shipping...

, meteorological

Meteorology

Meteorology is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the atmosphere. Studies in the field stretch back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not occur until the 18th century. The 19th century saw breakthroughs occur after observing networks developed across several countries...

and magnetic

Magnetism

Magnetism is a property of materials that respond at an atomic or subatomic level to an applied magnetic field. Ferromagnetism is the strongest and most familiar type of magnetism. It is responsible for the behavior of permanent magnets, which produce their own persistent magnetic fields, as well...

surveys throughout the polar basin. In 1884, a press item stating that the American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

Jeanette

USS Jeannette (1878)

The first USS Jeannette was originally HMS Pandora, a Philomel-class gunvessel of the Royal Navy, and was purchased in 1875 by Sir Allen Young for his arctic voyages in 1875-1876. The ship was purchased in 1878 by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., owner of the New York Herald; and renamed Jeannette...

had sunk near the Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

n coast three years before inspired Fridtjof Nansen. The Captain of this ship, lieutenant George Washington de Long, assumed that currents existed floating ships deep into the polar ice.

Three years after the loss of the Jeanette and de Long's death, some items of equipment and few sou'wester pants were found on the southwestern Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

coast. When Nansen heard about that there was only one possible explanation for him: These pieces had drifted surrounded by ice via the polar basin and along the East coast of Greenland until they ended up in Julianehab. The driftwood used by the Inuit

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Canada , Denmark , Russia and the United States . Inuit means “the people” in the Inuktitut language...

was even more enlightening for Nansen. It could only derive from the areas of the Siberian rivers that flowed into the Arctic Ocean. This hazarded a guess that there was a current which floated from somewhere between the pole and Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Franz Joseph Land, or Francis Joseph's Land is an archipelago located in the far north of Russia. It is found in the Arctic Ocean north of Novaya Zemlya and east of Svalbard, and is administered by Arkhangelsk Oblast. Franz Josef Land consists of 191 ice-covered islands with a...

through the Arctic Ocean to the East coast of Greenland. After that, Nansen planned to freeze a ship into ice and to let it float. Unlike other explorers, Nansen supposed that a well-constructed ship would take him to the North Pole safely. As a scientist, he wanted to reach the Pole as well as to reconnoiter the sea area.

The success of the expedition depended on the ship's construction, especially its resistance against ice pressure. Indeed neither the Fram nor Nansen, who impatiently left his ship and ventured towards the pole on foot, achieved their goal but Nansen's theory about the currents was proved correct.

While Nansen was returning from the ice of the Arctic Ocean, his countryman Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He led the first Antarctic expedition to reach the South Pole between 1910 and 1912 and he was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles. He is also known as the first to traverse the Northwest Passage....

set off to the Antarctic

Antarctic

The Antarctic is the region around the Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica and the ice shelves, waters and island territories in the Southern Ocean situated south of the Antarctic Convergence...

. Aboard the Belgica

RV Belgica

Belgica was and is the name of two Belgian research vessels, with a name derived ultimately from the Latin Gallia Belgica.See also...

Amundsen accompanied the Belgian Antarctic Expedition

Belgian Antarctic Expedition

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897 to 1899, named after its expedition vessel Belgica, was the first expedition to winter in the Antarctic region.- Preparation and Surveying :...

as a steersman. For this adventure Adrien de Gerlache

Adrien de Gerlache

Baron Adrien Victor Joseph de Gerlache de Gomery was an officer in the Belgian Royal Navy who led the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897 to 1899.-His early years:...

purchased the whale catcher Patric for 70,000 francs, overhauled the engine, arranged additional cabins, installed a laboratory and renamed the ship Belgica. Between 1887 and 1899, biological

Biology

Biology is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living organisms, including their structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, distribution, and taxonomy. Biology is a vast subject containing many subdivisions, topics, and disciplines...

and physical

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

observations were carried out to the west of the Antarctic Peninsula and to the south of Peter I Island

Peter I Island

Peter I Island is an uninhabited volcanic island in the Bellingshausen Sea, from Antarctica. It is claimed as a dependency of Norway, and along with Queen Maud Land and Bouvet Island comprises one of the three Norwegian dependent territories in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic. Peter I Island is ...

. The Belgica was the first ship that overwintered in the Antarctic. An international research team was aboard; later at the evaluation over 80 scientists participated. In 1895 Georg Neumayer

Georg von Neumayer

Georg Balthazar von Neumayer , was a German polar explorer and scientist who conceived the idea of international cooperation for meteorology and scientific observation....

, director of the Hamburg naval observatory, launched the slogan "off to the South Pole" at the sixth international geographic congress. Last but not least, motivated by reports of the Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink, who was the first person on the new continent, the congress declared the exploration of the Antarctica the urgent task for the following years.

20th century

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, Swedish and British expedition was prepared for the Southern Ocean

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

. Germany built the expedition ship Gauss

Gauss (ship)

Gauss was a ship used for the Gauss expedition to Antarctica. led by Arctic veteran and geology professor Erich von Drygalski....

for 1.5 million marks at the Howaldtswerke in Kiel

Kiel

Kiel is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 238,049 .Kiel is approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the north of Germany, the southeast of the Jutland peninsula, and the southwestern shore of the...

. On the model of the Fram, the Gauss, which weighed 1,442 tonnes (1,419 long tons) and was 46 metres (150.9 ft) long, had a round hulk in order to withstand the ice pressure. The Gauss had three masts and one auxiliary engine of 275 horsepower (205 kW). With a 60-strong crew, it could operate for almost three years without any help. From 1901 until 1903, Erich von Drygalski

Erich von Drygalski

Erich Dagobert von Drygalski was a German geographer, geophysicist and polar scientist, born in Königsberg, Province of Prussia....

led the German Antarctic expedition and carried out extensive studies mainly in the southern part of the Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

. The Swedish expedition under the command of Otto Nordenskjöld used the old Antarctic

Antarctic (ship)

The Antarctic was a Swedish steamship built in Drammen, Norway in 1871. She was used on several research expeditions to the Arctic region and to Antarctica through 1898-1903. In 1895 the first confirmed landing on the mainland of Antarctica was made from this ship.-The ship:Antarctic was a barque...

weighing only 353 tonnes, which had already been used by Borchgrevink in 1895. The expedition intending to overwinter at the Antarctic Peninsula was ill-starred from the beginning. In 1902, the Antarctic sank. Fortunately, the Argentine gunboat Uruguay

ARA Uruguay

The corbeta ARA Uruguay, built in England, is the largest ship afloat of its age in the Armada de la República Argentina , with more than 135 years passed since its official incorporation in September 1874...

rescued all crewmembers. Also Great Britain prompted Dundee Shipbuilders to build a ship for Robert Falcon Scott

Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, CVO was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13...

's expedition. The Discovery

RRS Discovery

The RRS Discovery was the last traditional wooden three-masted ship to be built in Britain. Designed for Antarctic research, she was launched in 1901. Her first mission was the British National Antarctic Expedition, carrying Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton on their first, successful...

weighed 1620 tonnes, was 52 metres (170.6 ft) long and had an auxiliary motor of 450 horsepower. Nevertheless, during the research the ship froze in. Only the relief ship Morning, sent by the British Admiralty, was able to free the Discovery and with Terra Nova escorted the Discovery back home. The reunion with the Antarctic ice was undertaken by a Scottish expedition

Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition , 1902–04, was organised and led by William Speirs Bruce, a natural scientist and former medical student from the University of Edinburgh. Although overshadowed in prestige terms by Robert Falcon Scott's concurrent Discovery Expedition, the SNAE completed...

led by the naturalist William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce was a London-born Scottish naturalist, polar scientist and oceanographer who organised and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition to the South Orkney Islands and the Weddell Sea. Among other achievements, the expedition established the first permanent weather station...

. Bruce had worked with the whale catchers Balaena and Active in the Southern Ocean in 1892 to 1893. He hoped that he could acquire the field-tested Balaena but found the ship too expensive, buying instead the Norwegian whale catcher

Whaler

A whaler is a specialized ship, designed for whaling, the catching and/or processing of whales. The former included the whale catcher, a steam or diesel-driven vessel with a harpoon gun mounted at its bows. The latter included such vessels as the sail or steam-driven whaleship of the 16th to early...

Hekla for £2,620, a ship that had sailed under the Danish flag along Greenland’s coast in 1891 and 1892. For another £8,000 he had the ship repaired and provided it with a new engine. Under the new name Scotia, this ship completed its way into the Southern Ocean and was very successful thanks to dredging and trawl catches at great depth in the Weddell Sea

Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha Coast, Queen Maud Land. To the east of Cape Norvegia is...

and off the coast.

At that point the French vessel Français, a 32 metres (105 ft) three-master arrived at the Antarctic horizon. The French doctor and naturalist

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

Jean-Baptiste Charcot was aboard. After his return from the ice he sold the Français but was not able to forget the Antarctic. In 1908 he purchased another three-master, the Pourquoi Pas, with which he worked successfully in the Southern Ocean. Later the northern polar waters sparked the Frenchman’s interest and in 1928 he participated in the rescue mission for Amundsen.

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, CVO, OBE was a notable explorer from County Kildare, Ireland, who was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration...

, a member of the "Discovery-Expedition" of 1901, returned with the forty year old Nimrod back into the Antarctic in order to march to the South Pole but had to give up just 180 km before his goal. Shackleton had at first tried to purchase the whale catcher Bjørn built at the Risør

Risør

is a city and municipality in Aust-Agder county, Norway. The city belongs to the traditional region of Sørlandet. It is a popular tourist place. The surrounding area includes many small lakes and hills, and is known for its beautiful coastline as well....

shipyard in Lindstøl. Since he couldn’t raise the wind, he conceded this ship to Wilhelm Filchner

Wilhelm Filchner

Wilhelm Filchner was a German explorer.At the age of 21, he participated in his first expedition, which led him to Russia. Two years later, he travelled alone and on horseback through the Pamir Mountains, from Osh to Murgabh to the upper Wakhan to Tashkurgan and back...

's second German Antarctic expedition. Filchner refurbished the ship at the Blohm & Voss dockyard and renamed it Deutschland. There was enough room for thirty-four crewmembers, while single cabins were available for scientists and mates. In addition, a geologist

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, a meteorologist, an oceanographer

Oceanography

Oceanography , also called oceanology or marine science, is the branch of Earth science that studies the ocean...

and a zoologist

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

shared a laboratory. The expedition, which visited the Southern Ocean between 1911 and 1912, made substantial contributions about the physical and chemical conditions in the western part of the southern Atlantic Ocean and the Weddell Sea. The Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese first arrived in the Southern Ocean in 1911. Ensign Nobu Shirase explored with the Kainan Maru the eastern part of the Ross Ice Shelf

Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica . It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than 600 km long, and between 15 and 50 metres high above the water surface...

. The years between 1910 until 1912 were characterized by the "great race" of Amundsen and Scott. While Scott travelled in the twenty-six year old Terra Nova, which had escorted him out of the ice in 1903, Roald Amundsen borrowed the reliable Fram for his South Pole expedition. During the dramatic race, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

unobtrusively sent its first expedition ship, the Aurora, into the Antarctic under Douglas Mawson

Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson, OBE, FRS, FAA was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer and Academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Ernest Shackleton, Mawson was a key expedition leader during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.-Early work:He was appointed geologist to an...

. An air-tractor

Air-tractor sledge

Sir Douglas Mawson's air-tractor sledge was a converted fixed-wing aircraft taken on the 1911–14 Australasian Antarctic Expedition, the first plane to be taken to the Antarctic. Expedition leader Douglas Mawson had planned to use the Vickers R.E.P...

, the first airplane in the region, was aboard but it proved to be useless. The failed attempt to cross Antarctica, for which Shackleton used the Endurance and Mawson's Aurora, was one of the last Antarctic expeditions before the outbreak of the First World War.

Between the world wars

After the war, Shackleton was one of the first to reengage in polar exploration. For a new Arctic expedition, he bought the Foca I which was designed in Norway and specified for polar areas. Organizational difficulties were encountered and Shackleton needed to change his plans and set course for the Southern Ocean. He did not complete the journey but died on the Quest at the beginning of his trip. His longtime comrade-in-arms Frank WildFrank Wild

Commander John Robert Francis Wild CBE, RNVR, FRGS , known as Frank Wild, was an explorer...

assumed the leadership and advanced as far as the South Sandwich Islands until pack ice

Sea ice

Sea ice is largely formed from seawater that freezes. Because the oceans consist of saltwater, this occurs below the freezing point of pure water, at about -1.8 °C ....

induced him to turn around and make for home. Later, the ship resumed its original role as a sealer. In 1930 to 1931 H. G. Watkins deployed the Quest for the British Air Route expedition, surveyed the eastern coast of Greenland in search of a site for an air base. The winner of the race, Roald Amundsen, made his way to the Arctic Ocean, his actual field of interest. In the following years between 1918 and 1922, he attempted to repeat Nansen's enterprise without success.

After the First World

First World

The concept of the First World first originated during the Cold War, where it was used to describe countries that were aligned with the United States. These countries were democratic and capitalistic. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the term "First World" took on a...

War interrupted oceanographic research, international scientific activities started anew in 1920. The invention of the echo sounder in 1912 reached a new significance for the international marine research

Marine Research

Marine Research was an indie rock/twee pop band, based in Oxford/London , formed in 1997 by four of the five members of Heavenly , following the suicide of Heavenly drummer Mathew Fletcher...

. Henceforth, it was possible to measure the distance to the seabed by sending acoustic

Underwater acoustics

Underwater acoustics is the study of the propagation of sound in water and the interaction of the mechanical waves that constitute sound with the water and its boundaries. The water may be in the ocean, a lake or a tank. Typical frequencies associated with underwater acoustics are between 10 Hz and...

signals instead of using wires and weights. Warships used echo sounders during the First World War. In 1922, the American destroyer

Destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast and maneuverable yet long-endurance warship intended to escort larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against smaller, powerful, short-range attackers. Destroyers, originally called torpedo-boat destroyers in 1892, evolved from...

Stewart took the first echo profile over the North Atlantic and one year later, the sonic logging between San Francisco and San Diego was published. Between 1929 and 1934 the USS Ramapo took about thirty profiles of the northern Pacific Ocean

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

. In 1927, the German cruiser

Cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. The term has been in use for several hundreds of years, and has had different meanings throughout this period...

Emden was able to carry out a series of soundings of the ocean trench

Trench

A trench is a type of excavation or depression in the ground. Trenches are generally defined by being deeper than they are wide , and by being narrow compared to their length ....

to the east of the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

.

The German ship Meteor

Meteor (1915)

The Meteor was a German survey vessel, that became famous for her survey work in the Atlantic Ocean between 1925 and 1927.- Design and Construction :...

was the first to use the echo sounder for scientific purposes in the 1920s on the German Meteor expedition

German Meteor expedition

The German Meteor expedition was an oceanographic expedition that explored the South Atlantic ocean from the equatorial region to Antarctica in 1925–1927...

. For the first time an ocean, the Atlantic, was systematically mapped. The Meteor crossed the South Atlantic from the ice line to 20° N on fourteen mapping ways. With 67,000 echo soundings, cartographers were able to produce a modern depth chart. Other geomagnetic and oceanographic mapping expeditions followed e.g. the American research ship Carnegie

Carnegie (ship)

The Carnegie was a brigantine yacht, equipped as a research vessel, constructed almost entirely from wood and other non-magnetic materials to allow sensitive magnetic measurements to be taken for the Carnegie Institution's Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. She carried out a series of cruises...

in the Pacific Ocean from 1928 to 1929, the detailed reconnaissance in Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

by the Dutch Willebrord Snellius, the exploration of the waters around the Antarctic by the British William Scoresby and Discovery II and the expedition of the American schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

Atlantis that sailed from the West Atlantic to the Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico is a partially landlocked ocean basin largely surrounded by the North American continent and the island of Cuba. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. In...

between 1932 and 1938. Also the Scandinavian countries

Nordic countries

The Nordic countries make up a region in Northern Europe and the North Atlantic which consists of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden and their associated territories, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Åland...

continued their activities at the end of the 1920s. Danish scientists devoted themselves to research in marine biology

Marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of organisms in the ocean or other marine or brackish bodies of water. Given that in biology many phyla, families and genera have some species that live in the sea and others that live on land, marine biology classifies species based on the environment rather...

. The oceanographic Dana Expedition, led by Johannes Schmidt

Johannes Schmidt (biologist)

Johannes Schmidt was a Danish biologist credited with discovering in 1920 that eels migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn...

and financed by the Carlsberg Foundation

Carlsberg Foundation

Carlsberg Foundation was founded by J. C. Jacobsen in 1876 and owns 30,3% of the shares in Carlsberg Group and has 74,2% of the voting power.The purpose of the foundation is to run and fund Carlsberg Laboratory, the museum at Frederiksborg Palace, to fund scientific research, run the Ny Carlsberg...

, was the most important Danish marine expedition. The treasured fish and plankton

Plankton

Plankton are any drifting organisms that inhabit the pelagic zone of oceans, seas, or bodies of fresh water. That is, plankton are defined by their ecological niche rather than phylogenetic or taxonomic classification...

species belonged to the greatest collection of that time. The deceased John Murray

John Murray (oceanographer)

Sir John Murray KCB FRS FRSE FRSGS was a pioneering Scottish oceanographer, marine biologist and limnologist.-Early life:...

had made a will stating that his invested inheritance would be used for an expedition as soon as enough capital would be accumulated. In 1931 was this the case and John Challenger Murray set work on realizing his father's wish. Since the envisaged research ships William Scoresby, Dana and George Bligh were inapplicable or unavailable respectively, the offer of the Egyptian government to take the "Mabahiss" was accepted. The Mabahiss left Alexandria on September 3, 1933 and returned on Mai 25, 1934. During this period she covered the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

, Bay of Biscay

Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Brest south to the Spanish border, and the northern coast of Spain west to Cape Ortegal, and is named in English after the province of Biscay, in the Spanish...

, Indian Ocean, and the Gulf of Oman

Gulf of Oman

The Gulf of Oman or Sea of Oman is a strait that connects the Arabian Sea with the Strait of Hormuz, which then runs to the Persian Gulf. It is generally included as a branch of the Persian Gulf, not as an arm of the Arabian Sea. On the north coast is Pakistan and Iran...

—more than 22,000 nautical miles (41,000 km) whereas chemical, physical and biological assays

Bioassay

Bioassay , or biological standardization is a type of scientific experiment. Bioassays are typically conducted to measure the effects of a substance on a living organism and are essential in the development of new drugs and in monitoring environmental pollutants...

were taken. The scientific leadership ran Seymour Sewell. In total, three British and two Egyptian scientists participated in this journey.

In 1923, Japan sent the Manchiu Maru in the Indian and Pacific Ocean and since 1927 the ships Shunpo Maru and Soyo Maru were on their way. From 1930 on the Shintoku Maru made annual trips into the Pacific Ocean for assays of the seawater.

Eight years later, a new phase of the marine research began. As so far, the marine research continued but from now, different countries worked together on one expedition. The German Altair and the Norwegian Armauer Hansen performed a common measurement program within in the scope of the international Gulf Stream

Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension towards Europe, the North Atlantic Drift, is a powerful, warm, and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates at the tip of Florida, and follows the eastern coastlines of the United States and Newfoundland before crossing the Atlantic Ocean...

expedition that shed light on the fluctuation of the Gulf Stream. For this international experiment the German Meteor, the Danish Dana and the French air-base vessel Carimare delivered data. In the same year, unconventional ships began with marine research.

Two flying boats, the Boreas and the Passat, equipped with aerial photography equipment were on board the ship Schwabenland. The application of this technology over Antarctica was revolutionary. Stereo photography

Stereoscopy

Stereoscopy refers to a technique for creating or enhancing the illusion of depth in an image by presenting two offset images separately to the left and right eye of the viewer. Both of these 2-D offset images are then combined in the brain to give the perception of 3-D depth...

was used. On the way back to Europe, the aircraft carrier conducted oceanographic, biological and meteorological observations and every fifteen to thirty minutes echo soundings were taken.

The oceanographic researches during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

were principally aligned with military questions. The study of underwater acoustic, which was significant for positioning submarines, and the study of waves and surf, which was important for the amphibious task force, dominated the marine research.

The postwar period

Albeit the big seafaring nations enlarged the postwar marine research, especially the USA strongly reengaged, other expeditions of two smaller countries were vitally important. The Swedish "Albatross" expedition of 1947/48 crossed eighteen times the equator and covered 45,000 nautical miles (83,000 km). Over 200 cores, fastened on a perpendicular, were dragged 1.5 km over the seabed. The Danish "Galathea" expedition from 1950 to 1951 under Bruun concentrated on studies about the living conditions in great depth and succeeded in catching fish in a depth of 10,190 meters (3,106 m).Already in the 1930s, American scientist began to use seismic measuring methods in flat waters and during the war, physicist Maurice Ewing

Maurice Ewing

William Maurice "Doc" Ewing was an American geophysicist and oceanographer.Ewing has been described as a pioneering geophysicist who worked on the research of seismic reflection and refraction in ocean basins, ocean bottom photography, submarine sound transmission , deep sea coring of the ocean...

carried the first seismic refraction

Seismic refraction

Seismic refraction is a geophysical principle governed by Snell's Law. Used in the fields of engineering geology, geotechnical engineering and exploration geophysics, seismic refraction traverses are performed using a seismograph and/or geophone, in an array and an energy source...

measurements out. The introduction of this geophysical method as well as the simultaneously beginning palaeomagnetic

Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism is the study of the record of the Earth's magnetic field in rocks. Certain minerals in rocks lock-in a record of the direction and intensity of the magnetic field when they form. This record provides information on the past behavior of Earth's magnetic field and the past location of...

researches (studying the Earth's magnetic field preserved in magnetic iron bearing minerals) led to a reinvigoration of Alfred Wegener

Alfred Wegener

Alfred Lothar Wegener was a German scientist, geophysicist, and meteorologist.He is most notable for his theory of continental drift , proposed in 1912, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth...

's continental drift

Continental drift

Continental drift is the movement of the Earth's continents relative to each other. The hypothesis that continents 'drift' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596 and was fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912...

theory and subsequent development of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

.

After the Second World War, the number of missions escalated worldwide as one can read in the Newsletters of Cooperative Investigations of the Mediterranean from Monaco. For the period from 1950 to 1960, 110 expeditions are displayed for the Mediterranean area.

Increasing collaboration

At the beginning of the 1950s, a rethinking of the marine research set in and the international close work between several ships was remarkable. In line with the NOPAC enterprise, Canadian, American ships ("Hugh M. Smith", "Brown Bear", "Ste. Teherse", "Horizon", "Black Douglas" "Stranger" "Spencer F. Baird") and the Japanese vessels ("Oshoro Maru", "Tenyo Maru", "Kagoshima Maru", "Satsuma" "Umitaka Maru") took part in this endeavor.On a grand scale, common international research programs got its way during the international geophysical year

International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year was an international scientific project that lasted from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific interchange between East and West was seriously interrupted...

(IGY) of 1957/58. For the exploration of deep-sea circulation and strong sea currents, sixty research ships out of forty nations were deployed. In cooperation of the research ships "Crawford", "Atlantis", "Discovery II", "Chain" and the Argentine sounding vessel "Capitan Canepa", fifteen profiles at intervals of eight latitudes between 48° N and 48° S were taken.

Furthermore twenty ships of twelve nations took part in the Cold Wall enterprise, which was another program of the IGY. The researches were about the Cold Wall, which separates the warm, high-salt Gulf Stream and the cold, low-salt water masses of polar origin and stretches northwestwards from the Newfoundland banks to the Norwegian Sea

Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea is a marginal sea in the North Atlantic Ocean, northwest of Norway. It is located between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea and adjoins the North Atlantic Ocean to the west and the Barents Sea to the northeast. In the southwest, it is separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a...

. Later on, Germany also participated in the program with the "Antorn Dohrn" and the "Gauss". This was Germany's first participation after World War II. For the first time, the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, which had a fleet of twenty research ships and one research dive station, took part in an international project during the IGY. Moreover, the USSR commissioned the research ships "Vityaz" (5700 t) and "Michail Lomonosov" (6000 t) and the icebreaker "Ob". The IGY marked the beginning of a new exploration phase in the marine research characterized by international cooperation and synoptic researches.

With the "Overflow" program, scientists tried to reconnoiter the overflow of the cold Arctic ground water

Groundwater

Groundwater is water located beneath the ground surface in soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. A unit of rock or an unconsolidated deposit is called an aquifer when it can yield a usable quantity of water. The depth at which soil pore spaces or fractures and voids in rock...

over the submarine ridge between Iceland and the Faroe Islands

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands are an island group situated between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately halfway between Scotland and Iceland. The Faroe Islands are a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, along with Denmark proper and Greenland...

. Nine research ships of five European countries took a stake in. This program was repeated at a larger scale: thirteen research ships of seven countries were on its way. Denmark appointed the "Dana" and the "Jens Christian Svabo", Iceland the "Bjarni Sæmundson", Canada the "Hudson", Norway the "Helland Hansen", USSR the "Boris Davydov" and the "Professor Zubov", Great Britain the Challenger, the "Shackleton" and the Explorer, West Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

the "Meteor", the "Walther Herwig" and the "Meerkatze II".

Tropical meteorology

Between the years 1959 and 1965, forty research ships of 23 countries assayed the Indian Ocean together. This ocean, having an exceptional position because of the monsoons and being surrounded by developing countriesDeveloping country

A developing country, also known as a less-developed country, is a nation with a low level of material well-being. Since no single definition of the term developing country is recognized internationally, the levels of development may vary widely within so-called developing countries...

, was the least known sea area. The abutters should have gotten an opportunity to start their own sea and fishing research programs. In 1958 the prelude was formed by the American ship "Vema", other ships joined in between 1959 and 1960: "Diamantina" (Australia), "Commandant Robert Giraud" (France), "Vitjaz" (USSR), "Argo", "Requisite" (USA) and the "Umitaka Maru". West Germany followed with its "Meteor" in 1964/64.

In the course of the longtime Global Atmospheric Research Programme

Global Atmospheric Research Programme

The Global Atmospheric Research Programme was a fifteen year international research programme led by the World Meteorological Organization and the International Council of Scientific Unions. It began in 1967 and organised several important field experiments including GARP Atlantic Tropical...

(GARP), the World Meteorological Organization

World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization is an intergovernmental organization with a membership of 189 Member States and Territories. It originated from the International Meteorological Organization , which was founded in 1873...

(WMO) called for a global weather experiment by which the entire atmosphere and the ocean surface are supposed to be observed for the first time. More than fifty ships worked in the equatorial areas around the globe and collected oceanographic and meteorological measured data for an "inventory of the world weather". Especially the continuation of the works and questions became the most important task for the next years and decades.

Besides these big international programs, the number of projects carried out by two or three countries increased. With increasing political and economical pressure, which resulted from the rising raw material supply, more and more countries participated in marine research.

Chinese research ships

Impressive are ChinaChina

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

's capacities of research ships. In the years between 1964 and 1975 alone, China built forty research ships such as the "Practice" of 1965 with a displacement of 3,167 tonnes (3,117 long tons) or the "Xiang Yang Hong 5" (10,000 tonnes or 9.840 tons) of 1972, which was China's first multipurpose research ship.

After 1976, the situation for Chinese marine researchers improved and in 1984 Liu Zhengang from the national bureau for oceanography reported at a scientific Congress that at first research ships had been created by remodeling fishing boats, freighters or discarded ships of the navy. A typical ship had been the “Jinxing” during that time of 1969. In the 1970s, China had begun to build new ships such as the 10,000 t multipurpose ship "Xiang Yang Hong 10". To cover the needed demands for oil discoveries, several geophysical ships had been built in China and in foreign countries. Since the development had continued, great importance had been attached to keep the ships on a well-equipped and technical level.

According to Zhengang's statement, the research fleet had consisted of 165 units with 150,000 tonnes altogether. Thereunder had been more than fifty ships with a tonnage of 5,000, twenty-two ships with a tonnage from 1,000 to 5,000, twenty ships with a tonnage between 500 and 1,000 and only fifty ships had had less than 50. Primarily, these ships had been run by the national bureau for oceanography, department of oil, department of agriculture and by universities. During the southern summer of 1984/1985, the "Xiang Yang Hong 10" and the "J 121" had been the first Chinese research ships which had sailed to the Antarctic in order to build the research station "Great Wall". China had caught up with the marine research works of the 1970s and '80s and had tried to get a voice in the future of Antarctica.

Autonomous Vessels

Mechanically and hydrodynamically, autonomous research platforms are similar to towed sonar "fish"Towed array sonar

A towed array sonar is a sonar array that is towed behind a submarine or surface ship. It is basically a long cable, up to 5 km, with hydrophones that is trailed behind the ship when deployed. The hydrophones are placed at specific distances along the cable...

and ROV

Rov

Rov is a Talmudic concept which means the majority.It is based on the passage in Exodus 23;2: "after the majority to wrest" , which in Rabbinic interpretation means, that you shall accept things as the majority....

s. Operationally, however, known autonomous vehicles were initially limited to rivers, lakes, and bays due to navigation and collision-avoidance issues. Thus, progress in surface vessels lagged behind both unmanned aerial vehicle

Unmanned aerial vehicle

An unmanned aerial vehicle , also known as a unmanned aircraft system , remotely piloted aircraft or unmanned aircraft, is a machine which functions either by the remote control of a navigator or pilot or autonomously, that is, as a self-directing entity...

s and submarine-types, due to their simpler operating conditions. Nevertheless, advances in navigation, machine vision and other sensors, and processing have spread ASVs from highly-advanced models to the undergraduate level.

See also

- Research vesselResearch vesselA research vessel is a ship designed and equipped to carry out research at sea. Research vessels carry out a number of roles. Some of these roles can be combined into a single vessel, others require a dedicated vessel...

- Heroic Age of Antarctic ExplorationHeroic Age of Antarctic ExplorationThe Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration defines an era which extended from the end of the 19th century to the early 1920s. During this 25-year period the Antarctic continent became the focus of an international effort which resulted in intensive scientific and geographical exploration, sixteen...

- List of Arctic expeditions

- List of Antarctic expeditions