History of the British Virgin Islands

Encyclopedia

- Pre-Columbian Amerindian settlement, up to an uncertain date

- Nascent European settlement, from approximately 1612 until 1672

- British control, from 1672 until 1834

- Emancipation, from 1834 until 1950

- The modern state, from 1950 to present day

These time periods are used for convenience only. There appears to be an uncertain period of time from when the last Arawaks left what would later be called the British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands, often called the British Virgin Islands , is a British overseas territory and overseas territory of the European Union, located in the Caribbean to the east of Puerto Rico. The islands make up part of the Virgin Islands archipelago, the remaining islands constituting the U.S...

until the first Europeans started to settle there in the early 17th century, but each period commences with a dramatic change from the time period which precedes it, and so is a convenient way to compartmentalise the subject.

Pre-Columbian settlement

The first recorded settlement of the Territory was by Arawak Indians who came from South AmericaSouth America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

, in around 100 BC. However, there is some dispute about the dates. Some historians place it later, at around 200 AD, but they suggest that the Arawaks may have been preceded by the Ciboney

Ciboney

The Ciboney were pre-Columbian indigenous inhabitants of the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. The name Ciboney derives from the indigenous Taíno people which means Cave Dwellers; evidence has shown that a number of the Ciboney people have lived in caves at some time. Over the years, many...

Indians, who are thought to have settled in nearby St. Thomas

Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands

Saint Thomas is an island in the Caribbean Sea and with the islands of Saint John, Saint Croix, and Water Island a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands , an unincorporated territory of the United States. Located on the island is the territorial capital and port of...

as early as 300 BC. There is some evidence of Amerindian presence on the islands as far back as 1500 BC,http://dg.ian.com/index.jsp?cid=54918&action=viewLocation&formId=105392 although there is little academic support for the idea of a permanent settlement on any of the current British Virgin Islands at that time.

The Arawaks inhabited the islands until the 15th century when they were displaced by the more aggressive Caribs, a tribe from the Lesser Antilles

Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles are a long, partly volcanic island arc in the Western Hemisphere. Most of its islands form the eastern boundary of the Caribbean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean, with the remainder located in the southern Caribbean just north of South America...

islands, after whom the Caribbean Sea

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean located in the tropics of the Western hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico and Central America to the west and southwest, to the north by the Greater Antilles, and to the east by the Lesser Antilles....

is named. Some historians, however, believe that this popular account of warlike Caribs chasing peaceful Arawaks out of the Caribbean islands is rooted in simplistic European stereotypes, and that the true story is more complex.

None of the later European visitors to the Virgin Islands ever reported encountering Amerindians in what would later be the British Virgin Islands, although Columbus would have a hostile encounter with the Carib natives of St. Croix

Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands

Saint Croix is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands , an unincorporated territory of the United States. Formerly the Danish West Indies, they were sold to the United States by Denmark in the Treaty of the Danish West Indies of...

.

Comparatively little is known about the early inhabitants of the Territory specifically (as opposed to the Arawaks generally). The largest excavations of Arawak pottery have been found around Belmont and Smuggler's Cove on the northwest of Tortola

Tortola

Tortola is the largest and most populated of the British Virgin Islands, a group of islands that form part of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands. Local tradition recounts that Christopher Columbus named it Tortola, meaning "land of the Turtle Dove". Columbus named the island Santa Ana...

, but many other sites have been found, including at Soper's Hole, Apple Bay, Coxheath, Pockwood Pond, Pleasant Valley, Sage Mountain, Russell Hill (modern day Road Town

Road Town

-See also:* Government House, the official residence of the Governor of the British Virgin Islands located in Road Town-External links:*****...

), Pasea, Purcell, Paraquita Bay, Josiah's Bay, Mount Healthy and Cane Garden Bay. Modern archaeological excavations regularly cause local historians to revise what they thought they knew about these early settlers. Discoveries reported in the local newspapers in 2006 have caused postulation that the settlement of the islands by Arawaks may have been much more significant than had earlier been thought.

1472 - Early European exploration

The first European sighting of the Virgin Islands was by Christopher ColumbusChristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

in 1493 on his second voyage to the Americas. Columbus gave them the fanciful name Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Vírgenes (Saint Ursula and her 11,000 Virgins), shortened to Las Vírgenes (The Virgins), after the legend of Saint Ursula

Saint Ursula

Saint Ursula is a British Christian saint. Her feast day in the extraordinary form calendar of the Catholic Church is October 21...

. He is also reported to have personally named Virgin Gorda

Virgin Gorda

Virgin Gorda is the third-largest and second most populous of the British Virgin Islands . Located at approximately 18 degrees, 48 minutes North, and 64 degrees, 30 minutes West, it covers an area of about...

(the Fat Virgin), which he thought to be the largest island in the group.

The Spanish claimed the islands by original discovery, but did nothing to enforce their claims, and never settled the Territory. In 1508 Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de Leon II

Juan Ponce de León II , was the first Puerto Rican to assume, though temporarily, the governorship of Puerto Rico.-Early years:...

settled Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

, and reports in Spanish journals suggested that the settlement used the Virgin Islands for fishing, but nothing else. It is unclear whether they sailed as far as the modern British Virgin Islands to fish, and the references may be to the present U.S. Virgin Islands

United States Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands of the United States are a group of islands in the Caribbean that are an insular area of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located in the Leeward Islands of the Lesser Antilles.The U.S...

.

In 1517 Sir Sebastian Cabot

Sebastian Cabot (explorer)

Sebastian Cabot was an explorer, born in the Venetian Republic.-Origins:...

and Sir Thomas Pert visited the islands on their way back from their exploration of Brazilian waters.

John Hawkins

Admiral Sir John Hawkins was an English shipbuilder, naval administrator and commander, merchant, navigator, and slave trader. As treasurer and controller of the Royal Navy, he rebuilt older ships and helped design the faster ships that withstood the Spanish Armada in 1588...

visited the island three times, firstly in 1542 and then again in 1563 with a cargo of slaves bound for Hispaniola

Hispaniola

Hispaniola is a major island in the Caribbean, containing the two sovereign states of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The island is located between the islands of Cuba to the west and Puerto Rico to the east, within the hurricane belt...

. On his third visit, he was accompanied by a young Captain by the name of Francis Drake in the Judith, for whom the central channel in the British Virgin Islands would later be named.

Drake would return in 1585, and is reported to have anchored in North Sound on Virgin Gorda prior to his tactically brilliant attack on Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo, known officially as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is the capital and largest city in the Dominican Republic. Its metropolitan population was 2,084,852 in 2003, and estimated at 3,294,385 in 2010. The city is located on the Caribbean Sea, at the mouth of the Ozama River...

. Drake returned for the final time in 1595 on his last voyage during which he would eventually meet his death.

In 1598 the Earl of Cumberland

George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland

Sir George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, KG was an English peer, as well as a naval commander and courtier in the court of Queen Elizabeth I.-Background:...

is reported to have used the islands as a staging ground for his later attack on La Fortaleza

La Fortaleza

La Fortaleza is the current official residence of the Governor of Puerto Rico. It was built between 1533 and 1540 to defend the harbor of San Juan. The structure is also known as Palacio de Santa Catalina . It is the oldest executive mansion in the New World...

in Puerto Rico.

In 1607 some reports suggest that John Smith

John Smith of Jamestown

Captain John Smith Admiral of New England was an English soldier, explorer, and author. He was knighted for his services to Sigismund Bathory, Prince of Transylvania and friend Mózes Székely...

sailed past the Virgin Islands on the expedition led by Captain Christopher Newport

Christopher Newport

Christopher Newport was an English seaman and privateer. He is best known as the captain of the Susan Constant, the largest of three ships which carried settlers for the Virginia Company in 1607 on the way to find the settlement at Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, which became the first permanent...

to found the new colony in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

.

English (and Scottish) monarch King James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

granted a patent to the Earl of Carlisle

James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle

James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle was a Scottish aristocrat.-Life:He was the son of Sir James Hay of Fingask , and of Margaret Murray, cousin of George Hay, afterwards 1st Earl of Kinnoull.He was knighted and taken into favor by James VI of Scotland, brought into England in 1603, treated as a "prime...

for Tortola

Tortola

Tortola is the largest and most populated of the British Virgin Islands, a group of islands that form part of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands. Local tradition recounts that Christopher Columbus named it Tortola, meaning "land of the Turtle Dove". Columbus named the island Santa Ana...

, as well as "Angilla

Anguilla

Anguilla is a British overseas territory and overseas territory of the European Union in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin...

, Semrera (Sombrero island

Sombrero, Anguilla

Sombrero, also known as Hat Island, is the northernmost island of the Lesser Antilles in position 18° 60'N, 63° 40'W. It lies north west of Anguilla across the Dog and Prickly Pear Passage. The distance to Dog Island, the closest island of Anguilla, is . Sombrero is long north-south, and wide....

) & Enegada

Anegada

Anegada is the northernmost of the British Virgin Islands, a group of islands which form part of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands. It lies approximately north of Virgin Gorda. Anegada is the only inhabited British Virgin Island formed from coral and limestone, rather than being of volcanic...

". He also received letters of patent for Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

, St. Kitts

Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts Saint Kitts Saint Kitts (also known more formally as Saint Christopher Island (Saint-Christophe in French) is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean...

and "all the Caribees" in 1628. Carlisle died shortly after, but his son, the 2nd Earl of Carlisle, leased the patents to Lord Willoughby

Montagu Bertie, 2nd Earl of Lindsey

Montagu Bertie, 2nd Earl of Lindsey, 15th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, KG, PC was the eldest son of Robert Bertie, 1st Earl of Lindsey and his wife Elizabeth Montagu, daughter of Edward Montagu, 1st Baron Montagu of Boughton.-Early life:...

for 21 years in 1647. Neither ever attempted to settle the northern islands.

First Dutch settlements

Dutch privateerPrivateer

A privateer is a private person or ship authorized by a government by letters of marque to attack foreign shipping during wartime. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without having to spend public money or commit naval officers...

Joost van Dyk

Joost van Dyk

Joost van Dyk was a Dutch privateer who was one of the earliest European settlers in the British Virgin Islands in the seventeenth century, and established the first permanent settlements within the Territory...

organized the first permanent settlements in the Territory in Soper's Hole, on the west end of Tortola. It is not known precisely when he first came to the Territory, but by 1615 van Dyk's settlement was recorded in Spanish contemporary records, noting its recent expansion. He traded with the Spaniards in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

and farmed cotton and tobacco.

Some sources suggest that the first settlements in the Virgin Islands were by the Spanish, who mined copper at the copper mine on Virgin Gorda

Copper Mine, Virgin Gorda

The Copper Mine on Virgin Gorda, British Virgin Islands is a National Park containing the ruins of an abandoned 19th-century copper mine.Copper was first discovered on Virgin Gorda...

, but there is no archaeological evidence to support the existence of any settlement by the Spanish in the islands at any time, or any mining of copper on Virgin Gorda prior to the 19th century.

By 1625, van Dyk was recognized by the Dutch West India Company

Dutch West India Company

Dutch West India Company was a chartered company of Dutch merchants. Among its founding fathers was Willem Usselincx...

as the private "Patron" of Tortola, and had moved his operations to Road Town

Road Town

-See also:* Government House, the official residence of the Governor of the British Virgin Islands located in Road Town-External links:*****...

. During the same year van Dyk lent some limited (non-military) support to the Dutch admiral Boudewijn Hendricksz, who sacked San Juan, Puerto Rico

San Juan, Puerto Rico

San Juan , officially Municipio de la Ciudad Capital San Juan Bautista , is the capital and most populous municipality in Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 395,326 making it the 46th-largest city under the jurisdiction of...

. In September 1625, in retaliation, the Spanish led a full assault on the island of Tortola, laying waste to its defenses and destroying its embryonic settlements. Joost van Dyk himself escaped to the island that would later bear his name

Jost Van Dyke

At roughly 8 square kilometers, and about 3 square miles Jost Van Dyke is the smallest of the four main islands of the British Virgin Islands, the northern portion of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands, located in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. Jost Van Dyke lies about 8 km to the...

, and sheltered there from the Spanish. He later moved to the island of St. Thomas

Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands

Saint Thomas is an island in the Caribbean Sea and with the islands of Saint John, Saint Croix, and Water Island a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands , an unincorporated territory of the United States. Located on the island is the territorial capital and port of...

until the Spanish gave up and returned to Puerto Rico.

Notwithstanding Spanish hostility, the Dutch West India Company still considered the Virgin Islands to have an important strategic value, as they were located approximately halfway between the Dutch colonies in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

(now Suriname

Suriname

Suriname , officially the Republic of Suriname , is a country in northern South America. It borders French Guiana to the east, Guyana to the west, Brazil to the south, and on the north by the Atlantic Ocean. Suriname was a former colony of the British and of the Dutch, and was previously known as...

) and the most important Dutch settlement in North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

, New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam was a 17th-century Dutch colonial settlement that served as the capital of New Netherland. It later became New York City....

(now New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

). Large stone warehouses were built at Freebottom, near Port Purcell (just east of Road Town), with the intention that these warehouses would facilitate exchanges of cargo between North and South America.

Cannon

A cannon is any piece of artillery that uses gunpowder or other usually explosive-based propellents to launch a projectile. Cannon vary in caliber, range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire, and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees,...

fort above the warehouse, on the hill where Fort George

Fort George, Tortola

Fort George is a colonial fort which was erected on the northeast edge of Road Town, Tortola in the British Virgin Islands above Baugher's Bay. The site is now a ruin....

would eventually be built by the English. They also constructed a wooden stockade to act as a lookout post above Road Town on the site that would eventually become Fort Charlotte

Fort Charlotte, Tortola

Fort Charlotte is a fort built on Harrigan's Hill , Tortola, British Virgin Islands. The fort was named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who was the wife of King George III....

. They stationed troops at the Spanish "dojon" near Pockwood Pond, later to be known as Fort Purcell

Fort Purcell

Fort Purcell is a ruined fort near Pockwood Pond on the island of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands.-History:...

, but now ordinarily referred to as "the Dungeon".

In 1631 the Dutch West India Company expressed an interest in the copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

which had been discovered

Copper Mine, Virgin Gorda

The Copper Mine on Virgin Gorda, British Virgin Islands is a National Park containing the ruins of an abandoned 19th-century copper mine.Copper was first discovered on Virgin Gorda...

on Virgin Gorda

Virgin Gorda

Virgin Gorda is the third-largest and second most populous of the British Virgin Islands . Located at approximately 18 degrees, 48 minutes North, and 64 degrees, 30 minutes West, it covers an area of about...

, and a settlement was set up on that island, which came to be known as "Little Dyk's" (now known as Little Dix).

In 1640 Spain attacked Tortola in an assault led by Captain Lopez. Two further attacks were made by the Spanish on Tortola in 1646 and 1647, led by Captain Francisco Vincente Duran. The Spanish anchored a warship in Soper's Hole at West End and landed men ashore. They then sent another warship to blockade Road Harbour. After a team of scouts returned a safe report, the Spanish landed more men and attacked Fort Purcell overland by foot. The Dutch were massacred, and the Spanish soldiers then marched to Road Town, where they killed everyone and destroyed the settlement. They did not, apparently, attack the smaller settlements further up the coast in Baugher's Bay, or on Virgin Gorda.

Decline of the Dutch West India Company

The settlements were not ultimately an economic success, and the evidence suggests that the Dutch spent most of their time more profitably engaged in privateering than trading. The lack of prosperity of the territory mirrored the lack of commercial success of the Dutch West India Company as a whole.The company changed its policy, and it sought to cede islands such as Tortola and Virgin Gorda to private persons for settlement, and to establish slave pens. The island of Tortola was eventually sold to Willem Hunthum

Willem Hunthum

Willem Hunthum was a Dutch merchant and the last legally recognised Dutch owner of Tortola in what later became the British Virgin Islands.-Life:Details of Hunthum's life are actually relatively scant...

at some point in the 1650s, at which time the Dutch West India Company's interest in the Territory effectively ended.

In 1665 the Dutch settlers on Tortola were attacked by a British privateer, John Wentworth, who is recorded as capturing 67 slaves, who were removed to Bermuda

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British overseas territory in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located off the east coast of the United States, its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, about to the west-northwest. It is about south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and northeast of Miami, Florida...

. This is the first official record of slaves being held in the Territory.

In 1666 there were reports that a number of the Dutch settlers were driven out by an influx of British "brigands and pirates", although clearly a number of the Dutch remained.

1672 - British colonisation

The British Virgin Islands came under British control in 1672, at the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Dutch WarThird Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo–Dutch War or Third Dutch War was a military conflict between England and the Dutch Republic lasting from 1672 to 1674. It was part of the larger Franco-Dutch War...

, and have remained so ever since. The circumstances of the British taking control however are somewhat uncertain. The Dutch averred that in 1672 Willem Hunthum put Tortola under the protection of Colonel Sir William Stapleton, the English Governor-General

Governor-General

A Governor-General, is a vice-regal person of a monarch in an independent realm or a major colonial circonscription. Depending on the political arrangement of the territory, a Governor General can be a governor of high rank, or a principal governor ranking above "ordinary" governors.- Current uses...

of the Leeward Islands

Leeward Islands

The Leeward Islands are a group of islands in the West Indies. They are the northern islands of the Lesser Antilles chain. As a group they start east of Puerto Rico and reach southward to Dominica. They are situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea meets the western Atlantic Ocean...

. Stapleton himself reported that he had captured the Territory shortly after the outbreak of war.

What is clear is that Colonel William Burt was dispatched to Tortola and took control of the island by no later than 13 July 1672 (when Stapleton reported the conquest to the Council of Trade). Burt did not have sufficient men to occupy the Territory, but before leaving the island, he destroyed the Dutch forts and removed all their cannon to St. Kitts

Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts Saint Kitts Saint Kitts (also known more formally as Saint Christopher Island (Saint-Christophe in French) is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean...

.

By the Treaty of Westminster

Treaty of Westminster (1674)

The Treaty of Westminster of 1674 was the peace treaty that ended the Third Anglo-Dutch War. Signed by the Netherlands and England, it provided for the return of the colony of New Netherland to England and renewed the Treaty of Breda of 1667...

of 1674, the war was ended, and provision was made for mutual restoration of all territorial conquests during the war. The Treaty provided the Dutch with the right to resume possession of the islands, but by then the Dutch were at war with the French, and fear of a French attack prevented their immediate restoration. Although the possessions were not considered valuable, for strategic reasons the British became reluctant to surrender them, and after prolonged discussions, orders were issued to Stapleton in June 1677 to retain possession of Tortola and the surrounding islands.

In 1678 the Franco-Dutch War

Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, often called simply the Dutch War was a war fought by France, Sweden, the Bishopric of Münster, the Archbishopric of Cologne and England against the United Netherlands, which were later joined by the Austrian Habsburg lands, Brandenburg and Spain to form a quadruple alliance...

ended, and the Dutch returned their attention to Tortola, although it was not until 1684 that the Dutch ambassador, Arnout van Citters, formally requested the return of Tortola. However, he did not do so on the basis of the Treaty of Westminster, but instead based the claim on the private rights of the widow of Willem Hunthum. He asserted that the island was not a conquest, but had been entrusted to the British. The ambassador provided a letter from Stapleton promising to return the island.

At this time (1686), Stapleton had completed his term of office and was en route back to Britain. The Dutch were told Stapleton would be asked to explain the discrepancy between his assertion of having conquered the island, and the correspondence signed by him indicating a promise to return it, after which a decision would be made. Unfortunately Stapleton travelled first to France to recover his health, where unfortunately he died. Cognisant that other Caribbean territories which had been captured from the Dutch during the war had already been restored, in August 1686 the Dutch ambassador was advised by the British that Tortola would be restored, and instructions to that effect were sent to Sir Nathaniel Johnson

Nathaniel Johnson (politician)

Sir Nathaniel Johnson was a soldier and a Member of Parliament for Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1680–1689. He was appointed governor of the Leeward Islands in 1686. He travelled to the Province of Carolina in 1689, becoming its governor in 1703...

, the new Governor of the Leeward Islands.

But Tortola was never actually returned to the Dutch. Part of the problem was that Johnson's orders were to restore the island to such person or persons who have "sufficient procuration or authority to receive the same..." However, most of the former Dutch colonists had now departed, having lost hope of restoration. Certainly there was no official representation of the Dutch monarchy or any other organ of government. In the event, Johnson did nothing.

In November 1696 a subsequent claim was made to the island by Sir Peter van Bell, the agent of Sir Joseph Shepheard, a Rotterdam

Rotterdam

Rotterdam is the second-largest city in the Netherlands and one of the largest ports in the world. Starting as a dam on the Rotte river, Rotterdam has grown into a major international commercial centre...

merchant, who claimed to have purchased Tortola on 21 June 1695 for 3,500 guilders. Shepheard was from the Margraviate of Brandenburg

Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806. Also known as the March of Brandenburg , it played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe....

, and the prospect of Tortola coming under Brandenburger control did not sit well in Westminster

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament or Westminster Palace, is the meeting place of the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom—the House of Lords and the House of Commons...

. The Brandenburg claim was dismissed by the British on the grounds that Stapleton had conquered rather than been entrusted with Tortola. The now common delaying tactic of forwarding all correspondence to Governor Codrington for comment was employed. Codrington readily appreciated the risks of a Brandenburg trading outpost on Tortola, as such an outpost already existed on nearby St. Thomas. The Brandenburgers had previously set up an outpost for trading slaves on Peter Island in 1690, which they had abandoned, and they were not considered welcome. At the time they had an outpost on St. Thomas, but they engaged in no agriculture, and only participated in the trading of slaves. Negotiations became more intense, and the British re-asserted the right of conquest and also (wrongly, but apparently honestly) claimed to have first discovered Tortola. During the negotiations, the British also became aware of two older historical claims, the 1628 patent granted to the Earl of Carlisle (which was inconsistent with Hunthum's title being sold to him by the Dutch West India company), and an order of the King in 1694 to prevent foreign settlement in the Virgin Islands. In February 1698 Codrington was told to regard the earlier 1694 orders as final, and the British entertained no further claims to the islands.

Geographical limits of the Territory

- St. ThomasSaint Thomas, U.S. Virgin IslandsSaint Thomas is an island in the Caribbean Sea and with the islands of Saint John, Saint Croix, and Water Island a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands , an unincorporated territory of the United States. Located on the island is the territorial capital and port of...

. The British initially claimed St. Thomas (and St. John as well), but in 1717 the Danish disputed their claim to those islands. In contrast to the long dispute over ownership of Tortola, the dispute over St. Thomas was settled readily with a year. The Danish claim was strong; they had the benefit of the Treaty of Alliance and Commerce of 1670 between Britain and Denmark, which led to the founding of the Danish West India CompanyDanish West India CompanyThe Danish West India Company or Danish West India-Guinea Company was a Danish chartered company that exploited colonies in the Danish West Indies. It was founded as the Danish Africa Company in 1659 in Glückstadt by a German Hendrik Carloff and two Dutchmen Isaac Coymans and Nicolaes Pancras....

in 1671 which its charter permitted it to take possession of and occupy the two islands. On 25 May 1672 the Danes took possession of St. Thomas, and discovered it to have been abandoned by the British settlers some weeks earlier. The British could scarcely object to the Danes retaining the island. - St. JohnSaint John, U.S. Virgin IslandsSaint John is an island in the Caribbean Sea and a constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands , an unincorporated territory of the United States. St...

. However, no sooner than the dispute over St. Thomas settled, than acrimony flared up again over St. John, when the Danes purported to settle it on 23 March 1718. The reaction of Walter Hamilton, Governor of the Leeward Islands, was immediate. He dispatched HMS Scarborough to the island. A period of fraught negotiations followed, but ultimately the Danes refused to quit St. John, and the British declined to use force to seize it. Truthfully, the British were less concerned about St. John than about St. Croix, which they thought that the Danes would eventually covet as well. - St. CroixSaint Croix, U.S. Virgin IslandsSaint Croix is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands , an unincorporated territory of the United States. Formerly the Danish West Indies, they were sold to the United States by Denmark in the Treaty of the Danish West Indies of...

(or St. Cruz, as it was known at the time). The British fears proved to be well founded. In 1729 a claim was made to St. Croix by the Danes who (in an ironic twist) claimed it had been sold to them by the French. St. Croix had been settled at an uncertain point over a century before by settlers from a number of different European nations, but in 1645 violence had flared up between them, and the English governor was murderMurderMurder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

ed. The English summarily expelled the Dutch, and the French, at their own request, were removed to GuadeloupeGuadeloupeGuadeloupe is an archipelago located in the Leeward Islands, in the Lesser Antilles, with a land area of 1,628 square kilometres and a population of 400,000. It is the first overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. As with the other overseas departments, Guadeloupe...

, leaving the British in sole control of the island. But in 1650 the Spanish invaded from Puerto Rico and the British surrendered the island. Later in the same year the Dutch had sought to return to St. Croix, believing that the Spanish would by then have returned to Puerto Rico, but when they arrived the Spanish were still there, and the Dutch were all killed or captured. The Governor General of the French Caribbean colonies then subsequently mounted an attack on the island at his own expense and drove out the Spanish, but he was unable to establish a colony, and surrendered the title to the island to the Grand Master of the Order of MaltaKnights HospitallerThe Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta , also known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta , Order of Malta or Knights of Malta, is a Roman Catholic lay religious order, traditionally of military, chivalrous, noble nature. It is the world's...

in 1653. In 1665 St. Croix reverted by purchase to the French West India CompanyFrench West India CompanyIn the history of French trade, the French West India Company was a chartered company established in 1664. Their charter gave them the property and seignory of Canada, Acadia, the Antilles, Cayenne, and the terra firma of South America, from the Amazon to the Orinoco...

, and upon the Company's collapse in 1674, the King of France claimed it as part of his dominions, although the island was subsequently ordered to be abandoned as an economic failure - the date of abandoning would later be hotly disputed. In May 1733 the French purported to sell the island to the Danish West India Company. If the French had only abandoned it in 1695 (as they asserted), it was French at the time of the Treaty. If the French had abandoned the island in 1671 (as the British claimed), then under the 1686 Treaty, St. Croix would be peacably in British possession. In the end, the French had documents to support their claim, and the British did not, and so the Council of Trade admitted that "upon the whole we must submit... whether it may be proper to advise His Majesty to insist any longer upon a title so weakly supported." The British thereafter ceased to resist the French sale of the island to the Danes.

Britain would actually conquer St. Thomas, St. John and St. Croix in March 1801 through the Napoleonic wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, but they restored them by the Treaty of Amiens

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens temporarily ended hostilities between the French Republic and the United Kingdom during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was signed in the city of Amiens on 25 March 1802 , by Joseph Bonaparte and the Marquess Cornwallis as a "Definitive Treaty of Peace"...

in March, 1802. They were then re-taken in December 1807, but were restored again by the Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1815)

Treaty of Paris of 1815, was signed on 20 November 1815 following the defeat and second abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte. In February, Napoleon had escaped from his exile on Elba; he entered Paris on 20 March, beginning the Hundred Days of his restored rule. Four days after France's defeat in the...

of 1815. Thereafter they would remain under Danish control until 1917 when they were sold to the U.S.A. for US$25 million, and were later renamed the "U.S. Virgin Islands".

- ViequesVieques, Puerto RicoVieques , in full Isla de Vieques, is an island–municipality of Puerto Rico in the northeastern Caribbean, part of an island grouping sometimes known as the Spanish Virgin Islands...

(or Crab Island, as the British referred to it). Vieques was periodically settled by the British, but on each occasion they were driven off by Spanish soldiers from nearby Puerto Rico. In the early 18th century, the Colonial authorities ordered the removal of British settlers on Vieques and re-settled them on St. KittsSaint KittsSaint Kitts Saint Kitts Saint Kitts (also known more formally as Saint Christopher Island (Saint-Christophe in French) is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean...

. Ironically enough, a century later after emancipation a number of former slaves would go and seek work on Vieques as free men of colour, notwithstanding that Vieques was still a slave owning society.

Relationships with the Danes were strained from the outset. The Danes continuously resorted to nearby islands for timber, clearly violating British sovereignty. British ships which foundered in St. Thomas was subject to extortionate levy for salvage. Further, St. Thomas became a base for pirates and privateers which the Danish Governor either could not or would not stop. During the War of the Spanish Succession

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was fought among several European powers, including a divided Spain, over the possible unification of the Kingdoms of Spain and France under one Bourbon monarch. As France and Spain were among the most powerful states of Europe, such a unification would have...

the Danes supported the French colonies, and allowed the French to sell British ships seized as prizes

Prize (law)

Prize is a term used in admiralty law to refer to equipment, vehicles, vessels, and cargo captured during armed conflict. The most common use of prize in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship and its cargo as a prize of war. In the past, it was common that the capturing force would be allotted...

in Charlotte Amalie

Charlotte Amalie, United States Virgin Islands

-Education:St. Thomas-St. John School District serves the community. and Charlotte Amalie High School serve the area.-Gallery:-See also:* Anna's Retreat* Cruz Bay* Saint Thomas* Water Island-External links:* *...

. No doubt the British invasions in the early 19th century did not help relations, and in later years smuggling and illegal sales of slaves by St. Thomians would frustrate British authorities.

Law and order

Even after British control of the Territory became complete, population infiltration was slow. Settlers lived in fear of possible Spanish attack, and there was the constant possibility that diplomatic efforts might fail and the Territory might revert to an overseas power (as happened in St. Croix). Spanish raids in 1685 and ongoing negotiations between the Dutch and the British over the fate of the islands led to them being virtually abandoned; from 1685 to 1690 the population of the Territory was reduced to two - a Mr Jonathan Turner and his wife. In 1690 there was a relative explosion in the population, which had swollen to fourteen. By 1696 it was up to fifty.

It was not until 1773 that the Virgin Islands actually had its own legislature. The uncertainty of tenure and slightly ambivalent official British attitude to the fate of the Territory influenced the early population - for many years only debtors from other islands, pirates and those fleeing the law were prepared to undertake the risk of settling in the Virgin Islands. Most references to the islands from occasional visitors comment on the lack of law and order and the lack of religiosity of the inhabitants.

The Territory was granted a Legislative Assembly on 27 January 1774, however, it took a full further decade for a constitutional framework to be settled. Part of the problem was that the islands were so thinly populated, it was almost impossible to constitute the organs of government. In 1778 George Suckling

George Suckling

George Suckling was a lawyer who was appointed to be the first Chief Justice of the British Virgin Islands in 1776. Suckling's appointment was not popular in the islands, which were at the time a notorious haunt for the lawless and for those seeking to evade their creditors elsewhere...

arrived in the Territory to take up his position as Chief Justice of the Territory. In the event, a court was not actually established until the Court Bill was passed in 1783, but even then the vested interests ensured that Suckling could still not take up his position, and the islands had a court but no judge. Suckling finally left the islands without ever taking up his post (or ever being paid) on 2 May 1788, impoverished and embittered, due to the machinations of local interests which were fearful of the recourse of their creditors if a court was to be established. Suckling was forthright in expressing his views on the state of law and order in the Territory - he described the residents of Tortola as "in a state of lawless ferment. Life, liberty and property were hourly exposed to the insults and depredations of the riotous and lawless. The authority of His Majesty's Council, as conservators of the peace, was defied and ridiculed... The island presented a shocking state of anarchy; miserable indeed, and disgraceful to government, not to be equalled in any other of His Majesty's dominions, or perhaps in any civilized country in the world."

Almost 100 years after Governor Parke had expressed his views, one of his successors would speak in similar terms. On his appointment in 1810, Governor George Elliot

George Elliot

George Elliot may refer to: *George Eliot, pen name of Mary Ann Evans , English novelist*George Elliot , British naval officer and Member of Parliament for Roxburghshire 1832–1835...

was struck by the "state of irritation ... almost of anarchy". Writer Howard, an agent selling a distressed cargo of slaves from a shipwreck in Tortola in 1803 wrote that "Tortola is well nigh the most miserable, worst-inhabited spot in all the British possessions... this unhealthy part of the globe appears overstocked with each description of people except honest ones."

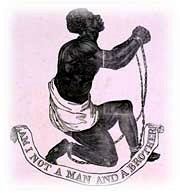

Quaker settlement

Although short in both duration and number, the Quaker settlement in the British Virgin Islands from 1727 to 1768 would play an important part in the history of the Territory for two reasons. Firstly, the trenchant opposition of the Quakers to slavery had a contributing effect to the improvements in the treatment of slaves within the Territory (the exceptional case of Arthur William HodgeArthur William Hodge

Arthur William Hodge was a plantation farmer, member of the Council and Legislative Assembly, and slave owner in the British Virgin Islands, who was hanged on 8 May 1811, for the murder of one of his slaves...

notwithstanding) compared to other Caribbean islands, and to the large number of free blacks

Free people of color

A free person of color in the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, is a person of full or partial African descent who was not enslaved...

within the islands. Secondly, for such a small community, a large number of famous historical figures came from that small community, including John C. Lettsome

John C. Lettsome

Dr. John Coakley Lettsome was an English physician and philanthropist born on Little Jost Van Dyke in the British Virgin Islands. He was born into one of the early Quaker settlements in the territory, and grew up to be an abolitionist...

, William Thornton

William Thornton

Dr. William Thornton was a British-American physician, inventor, painter and architect who designed the United States Capitol, an authentic polymath...

, Samuel Nottingham and Richard Humphreys. There are some vague assertions that Arthur Penn, brother of the more famous William Penn

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

, also formed part of the Quaker community of the British Virgin Islands for a time. However, this seems unlikely as the dates of his lifetime do not fit easily within the timeframe of the Quaker community in the British Virgin Islands, and as Quaker history is generally very well documented, it is unlikely that an expedition by a member of such a famous family would go unnoticed.

Fortification

Cannon

A cannon is any piece of artillery that uses gunpowder or other usually explosive-based propellents to launch a projectile. Cannon vary in caliber, range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire, and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees,...

were erected at Fort Charlotte

Fort Charlotte, Tortola

Fort Charlotte is a fort built on Harrigan's Hill , Tortola, British Virgin Islands. The fort was named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who was the wife of King George III....

, Fort George

Fort George, Tortola

Fort George is a colonial fort which was erected on the northeast edge of Road Town, Tortola in the British Virgin Islands above Baugher's Bay. The site is now a ruin....

, Fort Burt

Fort Burt

Fort Burt is a colonial fort that was erected on the southwest edge of Road Town, Tortola in the British Virgin Islands above Road Reef Marina. The site is now a hotel and restaurant of the same name, and relatively little of the original structure remains...

, Fort Recovery

Fort Recovery, Tortola

Fort Recovery is a fort on the West End of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands. In historical records, the fort is often referred to as Tower Fort, and the area around the fort is still referred to as "Towers" today...

and a new fort was built in the centre of Road Town which came to be known as the Road Town Fort

Road Town Fort

Road Town Fort is a colonial fort which was erected on Russell Hill in Road Town, Tortola in the British Virgin Islands above the town's main wharf. In historical records it is sometimes referred to as Fort Road Town...

. As was common at the time, plantation owners were expected to fortify their own holdings, and Fort Purcell

Fort Purcell

Fort Purcell is a ruined fort near Pockwood Pond on the island of Tortola in the British Virgin Islands.-History:...

and Fort Hodge were erected on this basis.

Slavery economy

In common with most CaribbeanCaribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

countries, slavery in the British Virgin Islands forms a major part of the history of the Territory. One commentator has gone so far as to say: "One of the most important aspects of the History of the British Virgin Islands is slavery."

As Tortola

Tortola

Tortola is the largest and most populated of the British Virgin Islands, a group of islands that form part of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands. Local tradition recounts that Christopher Columbus named it Tortola, meaning "land of the Turtle Dove". Columbus named the island Santa Ana...

, and to a lesser extent Virgin Gorda

Virgin Gorda

Virgin Gorda is the third-largest and second most populous of the British Virgin Islands . Located at approximately 18 degrees, 48 minutes North, and 64 degrees, 30 minutes West, it covers an area of about...

, came to be settled by plantation

Plantation

A plantation is a long artificially established forest, farm or estate, where crops are grown for sale, often in distant markets rather than for local on-site consumption...

owners, slave labour became economically essential, and there was an exponential growth in the slave population during the 18th century. In 1717 there were 547 black people in the Territory (all of whom were assumed to be slaves); by 1724, there were 1,430; and 1756, there were 6,121. The increase in slaves held in the Territory is, to a large degree, consistent with development of the economy of the British Virgin Islands at the time.

Slave revolts

Uprisings in the Territory were common, as they were elsewhere in the Caribbean. The first notable uprising in the British Virgin Islands occurred in 1790, and centred on the estates of Isaac Pickering. It was quickly put down, and the ring leaders were executedCapital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

. The revolt was sparked by the rumour that freedom had been granted to slaves in England, but that the planters were withholding knowledge of it. The same rumour would also later spark subsequent revolts.

Subsequent rebellions also occurred in 1823, 1827 and 1830, although in each case they were quickly put down.

Probably the most significant slave insurrection occurred in 1831 when a plot was uncovered to kill all of the white males in the Territory and to escape to Haiti

Haiti

Haiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

(which was at the time the only free black republic in the world) by boat with all of the white females. Although the plot does not appear to have been especially well formulated, it caused widespread panic, and military assistance was drafted in from St. Thomas. A number of the plotters (or accused plotters) were executed.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the incidence of slave revolts increased sharply after 1822. In 1807, the trade in slaves was abolished. Although the existing slaves were forced to continue their servitude, the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

patrolled the Atlantic, capturing slave ships and freeing slave cargoes. Starting in 1808 hundreds of freed Africans were deposited on Tortola by the Navy who, after serving a 14 year "apprenticeship", were then absolutely free. Naturally, seeing free Africans in the Territory created enormous resentment and jealousy amongst the existing slave population, who understandably felt this to be enormously unjust.

1834 - Emancipation

Public holidays in the British Virgin Islands

Holidays in the British Virgin Islands are predominantly religious holidays, with a number of additional national holidays. The most important holiday in the Territory is the August festival, which is celebrated on the three days from the first Monday in August to commemorate the abolition of...

on the first Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday in August in the British Virgin Islands. The original emancipation proclamation hangs in the High Court. However, the abolition of slavery was not the single defining event that it is sometimes supposed to have been. Emancipation freed a total of 5,792 slaves in the Territory, but at the time of abolition, there were already a considerable number of free blacks in the Territory, possibly as many as 2,000. Furthermore, the effect of abolition was gradual; the freed slaves were not absolutely manumitted, but instead entered a form of forced apprenticeship which lasted four years for house slaves and six years for field slaves. The terms of the forced apprenticeship required them to provide 45 hours unpaid labour a week to their former masters, and prohibited them from leaving their residence without the masters permission. The effect, deliberately, was to phase out reliance on slave labour rather than end it with a bang. The Council would later legislate to reduce this period to four years for all slaves to quell rising dissent amongst the field slaves.

Joseph John Gurney

Joseph John Gurney

Joseph John Gurney was a banker in Norwich, England and an evangelical Minister of the Religious Society of Friends , whose views and actions led, ultimately, to a schism among American Quakers.-Biography:...

, a Quaker, wrote in his Familiar Letters to Henry Clay of Kentucky that the plantation owners in Tortola were "decidedly saving money by the substitution of free labor on moderate wages, for the deadweight of slavery".

In practice, the economics of the abolition are difficult to quantify. Undeniably the original slave owners suffered a huge capital loss. Although they received £72,940 from the British Government in compensation, this was only a fraction of the true economic value of the manumitted slaves. In terms of net cash flow, whilst the slave owners lost the right to "free" slave labour, they now no longer had to pay to house, clothe and provide medical attention for their former slaves, which in some cases almost balanced out. The former slaves now usually worked for the same masters, but instead received small wages, out of which they had to pay for the expenses formerly borne by their masters. However, some former slaves managed to amass savings, which clearly demonstrates that in net terms the slave owners were less well off in income terms as well as capital as a result of abolition.

Decline of the sugar industry

An often held view is that the economy of the British Virgin Islands deteriorated considerably after the abolition of slavery. Whilst this is, strictly speaking, true, it also disguises the fact that the decline had several different causes. In 1834 the Territory was an agricultural economy with two main crops: sugarSugar

Sugar is a class of edible crystalline carbohydrates, mainly sucrose, lactose, and fructose, characterized by a sweet flavor.Sucrose in its refined form primarily comes from sugar cane and sugar beet...

and cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

. Of the two, sugar was the considerably more lucrative export.

Shortly after the abolition of slavery the Territory was rocked by a series of hurricanes. At the time, there was no accurate method of forecasting hurricanes, and their effect was devastating. A particularly devastating hurricane struck in 1837, which was reported to have completed destroyed 17 of the Territory's sugar works. Further hurricanes hit in 1842 and 1852. Two more struck in 1867 and 1871. The island also suffered severe drought between 1837 and 1847, which made sugar plantation almost impossible to sustain.

To compound these miseries, in 1846 the United Kingdom passed the Sugar Duties Act 1846

Sugar Duties Act 1846

The Sugar Duties Act 1846 was a statute of the United Kingdom which equalized import duties for sugar from British colonies. It was passed in 1846 at the same time as the repeal of the Corn laws by the Importation Act 1846...

to equalise duties on sugar grown in the colonies. Removing market distortion

Market distortion

In neoclassical economics, a market distortion is any event in which a market reaches a market clearing price for an item that is substantially different from the price that a market would achieve while operating under conditions of perfect competition and state enforcement of legal contracts and...

s had the net effect of making prices fall, a further blow to plantations in the British Virgin Islands.

In 1846 the commercial and trading firm of Reid, Irving & Co. collapsed. The firm had 10 sugar estates in the British Virgin Islands and employed 1,150 people. But the actual economic effect of its failure was much wider; the company also acted as a de facto bank in the Territory, allowing advances to be drawn on the company as credit. Further, the company had represented the only remaining direct line of communication to the United Kingdom; after its collapse mail had to be sent via St. Thomas and Copenhagen

Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

.

By 1848, Edward Hay Drummond Hay

Edward Hay Drummond Hay

Sir Edward Hay Drummond-Hay was a British naval officer, diplomat and colonial administrator.He was born in England, son of Captain Edward Drummond Hay, who was a nephew of the ninth Earl of Kinnoul, and educated at Charterhouse and was a Colonel of the 5th West India Regiment from 6 November 1854...

, the President of the British Virgin Islands, reported that: "there are now no properties in the Virgin Islands whose holders are not embarrassed for want of capital or credit sufficient to enable them to carry on the simplest method of cultivation effectively."

In December 1853 there was a disastrous outbreak of cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

in the Territory, which killed nearly 15% of the population. This was followed by an outbreak of smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

in Tortola and Jost Van Dyke

Jost Van Dyke

At roughly 8 square kilometers, and about 3 square miles Jost Van Dyke is the smallest of the four main islands of the British Virgin Islands, the northern portion of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands, located in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. Jost Van Dyke lies about 8 km to the...

in 1861 which caused a further 33 deaths.

Up until 1845 the value of sugar exported from the Territory varied, but averaged around £10,000 per annum over the preceding ten years. With the exception of 1847 (an unusually good year), the average for the subsequent 10 years was under £3,000. By 1852 it had fallen below £1,000 and would never recover.

Although this was terrible news for the islands as a whole, as Isaac Dookhan has pointed out, this did mean that the value of land plummeted sharply, and enabled the newly free black community to purchase land where otherwise it might not have been able to do so. It also created the basis for the future peasant agricultural economy of the British Virgin Islands.

Insurrection

Soon after emancipation the newly freed black population of the British Virgin Islands started to become increasingly disenchanted that freedom had not brought the prosperity that they had hoped for. Economic decline had led to increased tax burdens, which became a source of general discontent, for former slaves and other residents of the Territory alike.In 1848 a major disturbance occurred in the Territory. The causes of the disturbance were several. A revolt of slaves was occurring in St. Croix, which increased the general fervour in the islands, but the free population of Tortola were much more concerned with two other grievances: the appointment of public officials, and the crackdown on smuggling. Although Tortola had sixteen coloured public officials, all except one were "foreigners" from outside the Territory. During the period of economic decline, smuggling had been one of the few lucrative sources of employment, and recent laws which imposed stringent financial penalties (with hard labour for non-payment) were unpopular. The anger was directed against the magistrates by the small shop keepers, and they concentrated their attack on the stipendiary magistrate, Isidore Dyett. However, Dyett was popular with the rural population, who respected him for protecting them from unscrupulous planters. The ringleaders of the insurrection had supposed that their attack would lead to a general revolt, but their choice of Dyett as a target robbed them of popular support, and the disturbance eventually fizzled.

However, the insurrection of 1853 was a far more serious affair, and would have much graver and more lasting consequences. Arguably it was the single most defining event in the islands' history. Taxation and economics was also at the root of that disturbance. In March 1853 Robert Hawkins and Joshua Jordan, both Methodist missionaries, petitioned the Assembly to be relieved on taxes. The Assembly rejected the request, and Jordan is said to have replied "we will raise the people against you." Subsequent meetings fostered the general discontent. Then in June 1853 the legislature enacted a head tax on cattle in the Territory. Injudiciously, the tax was to come into effect on 1 August, the anniversary of emancipation. The burden of the tax would fall most heavily on the rural coloured community. There was no violent protest when the Act was passed, and it has been suggested that rioting could have been avoided if the legislature had been more circumspect in enforcing it, although the historical background suggests that insurrection was never far away, and only needed a reason to spark into life.

On 1 August 1853 a large body of rural labourers came to Road Town

Road Town

-See also:* Government House, the official residence of the Governor of the British Virgin Islands located in Road Town-External links:*****...

to protest the tax. However, instead of showing a conciliatory approach, the authorities immediately read the Riot Act

Riot Act

The Riot Act was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain that authorised local authorities to declare any group of twelve or more people to be unlawfully assembled, and thus have to disperse or face punitive action...

, and made two arrests. Violence then erupted almost immediately. Several constables and magistrates were badly beaten, the greater part of Road Town itself was burned down, and a large number of the plantation houses were destroyed, cane fields were burned and sugar mills destroyed. Almost all of the white population fled to St. Thomas. President John Chads

John Cornell Chads

Lieutenant-colonel John Cornell Chads joined the Royal Marines and reached the rank of 2nd Lieutenant on 4 May 1809 aged 16. He became a Captain in the 1st West India Regiment on 27 January 1820. He became a Major on 22 April 1836 still serving in the West India Regiment...

showed considerable personal courage, but little judgement or tact. On 2 August he met a gathering of 1,500 to 2,000 protesters, but all he would promise to do was relay their grievances before the legislature (which could not meet, as all the other members had fled). One protester was shot (the only recorded death during the disturbances themselves) which led to the continuation of the rampage. By 3 August, the only white people remaining in the Territory were John Chads himself, the Collector of Customs, a Methodist missionary and the island's doctor.

The riots were eventually suppressed with military assistance from St. Thomas, and reinforcements of British troops dispatched by the Governor of the Leeward Islands from Antigua

Antigua

Antigua , also known as Waladli, is an island in the West Indies, in the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region, the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua means "ancient" in Spanish and was named by Christopher Columbus after an icon in Seville Cathedral, Santa Maria de la...

. Twenty of the ringleaders of the riots were sentenced to lengthy terms of imprisonment; three were executed

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

.

"Decline and disorder"

The period which followed the riots of 1853 has been referred to by one historian as the period of "decline and disorder". Some commentators have suggested that the white population essentially refused to return, and the islands "went to de bush". But this is clearly an exaggeration. Whilst many whites did not return to their heavily mortgaged and now ruined estates, some did, and rebuilt. But the rebuilding required as a result of the insurrection, as well as the climate of uncertainty it created, alongside the existing poor economic conditions, created an economic depression which would take nearly a century to lift. It would in fact take a full two years before even the schools in the Territory would be able to open again.Tensions in the Territory continued to simmer, and local unrest ran high. Exports continued to decline, and large numbers travelled abroad seeking work. In 1887 a plot for an armed rebellion was uncovered. In 1890 a dispute over smuggling led to further violence, and a Long Look resident, Christopher Flemming, emerged as a local hero simply for standing up to authority. In each case widespread damage was averted by bringing in reinforcements for the local authorities from Antigua and, in 1890, from St. Thomas.

Whilst the violence undoubtedly reflected disenchantment with the economic decline and lack of social services, it would be wrong to construe this period as a form of "Dark Ages" for the Territory. During this period there was, for the first time, a significant expansion in the islands' schools. By 1875 the Territory had 10 schools; a remarkable development in light of the complete absence of functional schools after the insurrection of 1853. This period also saw the first coloured British Virgin Islander, Fredrick Augustus Pickering

Fredrick Augustus Pickering

Fredrick Augustus Pickering was the first ever coloured President of the British Virgin Islands. He was also the last President of the Territory; after he stepped down in 1887, no replacement was appointed. In 1889, the office was replaced with that of Commissioner. He served in the post from 1884...

, appointed as President in 1884.

Pickering stepped down in 1887, and in 1889 the title of the office was changed to Commissioner, marking a clear decrease in administrative responsibilities. Offices were also consolidated to save on salaries. The Council itself became less and less functional, and it only narrowly avoided dissolution by appointing two popular local figures, Joseph Romney and Pickering.

Modern developments

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a nation on the island of La Hispaniola, part of the Greater Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean region. The western third of the island is occupied by the nation of Haiti, making Hispaniola one of two Caribbean islands that are shared by two countries...

. Both concern and assistance from Britain was in very short supply, not least because of the two World War

World war

A world war is a war affecting the majority of the world's most powerful and populous nations. World wars span multiple countries on multiple continents, with battles fought in multiple theaters....

s which were fought during this period.

In 1947 another unlikely hero emerged. Theodolph H Faulkner was a fisherman from Anegada, who came to Tortola with his pregnant wife. He had a disagreement with the medical officer, and he went straight to the marketplace and for several nights criticised the government with mounting passion. His oratory struck a chord, and a movement started. Led by community leaders such as Isaac Fonseca and Carlton de Castro, a throng of over 1,500 British Virgin Islanders marched on the Commissioner's office and presented their grievances. The voices of the people were heard.

1950 - Self government

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

. The reformation of the Legislative Council is often left as a footnote in the Territory's history - a mere part of the process that led to the more fundamental constitutional government in 1966 - and the 1950 constitution was in fact always envisaged as a temporary measure. But, having been denied any form of democratic control for nearly 50 years, the new Council did not sit idly by. In 1951 external capital was brought in to assist farmers from the Colonial Welfare and Development office. In 1953 the Hotel Aid Act was enacted to boost the nascent tourism

Tourism

Tourism is travel for recreational, leisure or business purposes. The World Tourism Organization defines tourists as people "traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes".Tourism has become a...

industry. Up until 1958 the Territory had only 12 miles of motorable roads; over the next 12 years the road system was vastly improved, linking West End to the East End of Tortola, and joining Tortola to Beef Island

Beef Island

Beef Island is an island in the British Virgin Islands. It is located to the east of Tortola, and the two islands are connected by the Queen Elizabeth Bridge. Beef Island is the site of the Terrance B...

by a new bridge

Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, British Virgin Islands

The Queen Elizabeth II Bridge is a bridge that links Beef Island with Tortola in the British Virgin Islands. Two bridges have shared the same name, with one lasting from 1966 to 2003, and a new bridge that was completed in 2002.-The First Bridge:...

. The Beef Island airport (now renamed after Terrance B. Lettsome

Terrance B. Lettsome

Terrance B. Lettsome was a politician for whom the main airport in the British Virgin Islands is named. Born Terrance Buckley Lettsome in Long Look to Francis Henry and Frances Lettsome, he was one of the Territory's longest-serving legislators and the ninth of 11 children.He married the former...

) was built shortly thereafter. The Territory considered holding a plebiscite as to whether the British and U.S. Virgin Islands

United States Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands of the United States are a group of islands in the Caribbean that are an insular area of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located in the Leeward Islands of the Lesser Antilles.The U.S...

should merge under the U.S. flag, but (although there was no opposition from Westminster) it is unlikely that the U.S. State Department would have acquiesced to taking over responsibility for the impoverished Territory, and in the event no plebiscite was ever held.

External events also played a factor. In 1956 the Leeward Islands Federation was abolished. Defederation enhanced the political status of the British Virgin Islands. Jealous of its newly acquired powers, the Council declined to join the new Federation of the West Indies in 1958, a move that would later be crucial in the development of the offshore finance

Offshore financial centre

An offshore financial centre , though not precisely defined, is usually a small, low-tax jurisdiction specializing in providing corporate and commercial services to non-resident offshore companies, and for the investment of offshore funds....

industry.

In 1966 the new constitution with a much greater transfer of powers was brought into effect by order in council. Elections followed in 1967, and a comparatively young Lavity Stoutt

Lavity Stoutt

Hamilton Lavity Stoutt was the first and longest serving Chief Minister of the British Virgin Islands, winning four general elections and serving three non-consecutive terms of office from 1967 to 1971, again from 1981 to 1983 and again from 1986 until his death in 1995.Since Stoutt's death in...

was elected as the first Chief Minister of the Territory.

Financial services

Offshore financial centre

An offshore financial centre , though not precisely defined, is usually a small, low-tax jurisdiction specializing in providing corporate and commercial services to non-resident offshore companies, and for the investment of offshore funds....

industry. Former president of the BVI's Financial Services Commission

British Virgin Islands Financial Services Commission

The BVI Financial Services Commission is an autonomous regulatory authority responsible for the regulation, supervision and inspection of all financial services in and from within the British Virgin Islands, including insurance, banking, trustee business, company management, mutual funds business...

, Michael Riegels

Michael Riegels

Michael Riegels, QC was the inaugural chairman of the Financial Services Commission of the British Virgin Islands. He is a qualified barrister and was formerly the senior partner of Harneys from 1984 to 1997, and he also served the president of the BVI Bar Association from 1996 to 1998 and as...

, recites the anecdote that the industry commenced on an unknown date in the 1970s when a lawyer from a firm in New York telephoned him with a proposal to incorporate a company in the British Virgin Islands to take advantage of a double taxation

Double taxation

Double taxation is the systematic imposition of two or more taxes on the same income , asset , or financial transaction . It refers to taxation by two or more countries of the same income, asset or transaction, for example income paid by an entity of one country to a resident of a different country...

relief treaty

Tax treaty

Many countries have agreed with other countries in treaties to mitigate the effects of double taxation . Tax treaties may cover income taxes, inheritance taxes, value added taxes, or other taxes...

with the United States. Within the space of a few years, hundreds of such companies had been incorporated.

This eventually came to the attention of the United States government, who unilaterally revoked the Treaty in 1981.