History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Encyclopedia

The history of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict covers from the end of the 19th century to the present day. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict

centers on conflicting, often mutually exclusive claims to the area called Palestine

by the Palestinians and the Land of Israel

by Israeli Jews.

, the Middle East

region, including Palestine, was under the control of the Ottoman Empire

for nearly 400 years. Towards the end of the 19th century, Palestine, divided between the Vilayets of Damascus and Beirut and the Mustafiyyet of Jerusalem, was inhabited predominantly by Arab

Muslims, both farmers and Bedouin

(principally in the Negev

and Jordan valley

), with smaller numbers of Christians

(predominantly Arab), Druze

, Circassians and Jews

(predominantly Sephardic

). At that time most of the Jews worldwide lived outside of Palestine, predominantly in eastern

and central Europe

, with significant communities in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Americas.

The roots of the conflict can be traced to the late 19th century, with the rise of national movements, including Zionism

The roots of the conflict can be traced to the late 19th century, with the rise of national movements, including Zionism

and Arab nationalism

. Though the Jewish aspiration to return to Zion had been part of Jewish religious thought for a millennia, the Jewish population of Europe and to some degree Middle East began to more actively discuss immigration back to the Land of Israel

, and the re-establishment of the Jewish Nation in its national homeland, only during the 1870s

and 1880s

, largely as a solution to the widespread persecution of Jews due to anti-Semitism

in Russia

and Europe

. As a result, the Zionist movement, the modern movement for the creation of a homeland for the Jewish people, was established as a political movement in 1897.

The Zionist movement called for the establishment of a nation-state

for the Jewish people in Palestine

, which would serve as a haven

for the Jews of the world

and in which they would have the right for self-determination

. Zionists increasingly came to hold that this state should be in their historic homeland, which they referred to as the Land of Israel

. The World Zionist Organization

and the Jewish National Fund

encouraged immigration

and funded purchase of land, both under Ottoman

rule and under British rule, in the region of Palestine. While Arab nationalism

, at least in an early form, and Syrian nationalism

were the dominant tendencies along with continued loyalty to the Ottoman state.

According to Benny Morris, among the first recorded violent incidents between Arabs and Jews in Palestine was the accidental shooting dead of an Arab man in Safed

, during a wedding in December 1882, by a Jewish guard of the newly formed Rosh Pina. In response, about 200 Arabs descended on the Jewish settlement throwing stones and vandalizing property. Another incident happened in Petach Tikva, where in early 1886 the Jewish settlers demanded that their tenants vacate the disputed land and started encroaching on it. On March 28, a Jewish settler crossing this land was attacked and robbed of his horse by Yahudiya Arabs, while the settlers confiscated nine mules found grazing in their fields, though it is not clear which incident came first and which was the retaliation. The Jewish settlers refused to return the mules, a decision viewed as a provocation. The following day, when most of the settlement's men folk were away, fifty or sixty Arab villagers attacked Petach Tikva, vandalizing houses and fields and carrying off much of the livestock. Four Jews were injured and a fifth, an elderly woman with a heart condition, died four days later.

By 1908, thirteen Jews had been killed by Arabs, with four of them killed in what Benny Morris calls "nationalist circumstances", the others in the course of robberies and other crimes. In the next five years twelve Jewish settlement guards were killed by Arabs. Settlers began to speak more and more of Arab "hatred" and "nationalism" lurking behind the increasing depredations, rather than mere "banditry".

Zionist ambitions were increasingly identified as a threat by the Arab leaders in Palestine region. Certain developments, such as the acquisition of lands from Arab owners for Jewish settlements, leading to the eviction of the fellaheen from the lands which they cultivated as tenant farmer

s, aggravated the tension between the parties and caused the Arab population in the region of Palestine to feel dispossessed of their lands. Ottoman land purchase regulations were brought in after local complaints in opposition to increasing immigration. Ottoman policy makers in the late 19th century were apprehensive of the increased Russian and European influence in the region, partly as a result of a large immigration wave from the Russian Empire

. The Ottoman authorities feared that the loyalty of immigrants was primary to their country of origin, Russia, with whom the Ottoman Empire had a long history of conflicts, and therefore it might undermine Turkish control in the region of Palestine. The main reason for this concern was the dismantling of Ottoman authority in the Balkan region. The main reason for the initial hostility, in the 1880s, towards the Jewish immigration was on the grounds of their being Russian and European, rather than Jewish. European immigration was considered by local residents as a threat to the cultural make-up of the region. The regional significance of the anti-Jewish riots

(pogroms) in Russia

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and anti-immigration legislation being enacted in Europe was that Jewish immigration waves began arriving in Palestine (see First Aliyah

and Second Aliyah

). As a result of the extent of the various Zionist enterprises which started becoming apparent, the Arab population in the Palestine region began protesting against the acquisition of lands by the Jewish population. As a result, in 1892 the Ottoman authorities banned land sales to foreigners. By 1914 the Jewish population in Palestine had risen to over 60,000, with around 33,000 of these being recent settlers.

As a result of a mutual defense treaty that the Ottoman Empire made with Germany

As a result of a mutual defense treaty that the Ottoman Empire made with Germany

, during World War I

the Ottoman Empire

joined the Central Powers

and therefore the Ottoman Empire was now embroiled in a conflict with Great Britain

and France

. The possibility of releasing Palestine from the control of the Ottoman Empire led the Jewish population and the Arab population in Palestine to support the alignment of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia

during World War I. In 1915, the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence

was formed as an agreement with Arab leaders to grant sovereignty to Arab lands under Ottoman control to form an Arab state in exchange for the Great Arab Revolt

against the Ottomans. However, the Balfour Declaration

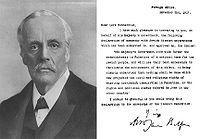

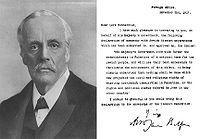

in 1917 proposed to "favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, but that nothing should be done to prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine." In 1916, the Anglo-French Sykes-Picot Agreement

allocated to the British Empire the area of present day Jordan

, the area of present day Israel

and the West Bank

, and the area of present day Iraq

. The Balfour Declaration was seen by Jewish nationalists as the cornerstone of a future Jewish homeland on both sides of the Jordan River, but increased the concerns of the Arab population in the Palestine region.

In 1917, the British succeeded in defeating the Ottoman Turkish forces and occupied the Palestine region. The land remained under British military administration

for the remainder of the war.

On January 3, 1919, future president of the World Zionist Organization

Chaim Weizmann

and the future King Faisal I of Iraq

signed the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement

for Arab

-Jewish cooperation in the Middle East

in which Faisal conditionally accepted the Balfour Declaration based on the fulfillment of British wartime promises of development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Faisal's agreement with Weizmann led the Palestinian Arab population to reject the Syrian-Arab-Nationalist movement led by Faisal (in which many previously placed their hopes) and instead to agitate for Palestine to become a separate state with an Arab majority.

At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference

and Treaty of Versailles

, Turkey's loss of its Middle East Empire was formalized.

and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire

, in April 1920 the Allied Supreme Council meeting at San Remo

granted to Britain the mandates for Palestine

and Transjordan

(the territories that include the area of present day Israel

, Jordan

, West Bank

and the Gaza Strip

), endorsing the terms of the Balfour Declaration. In August 1920, this was officially acknowledged in the Treaty of Sèvres

. Both Zionist and Arab representatives attended the conference, where they met and signed an agreement to cooperate. The agreement was never implemented. The borders and terms under which the mandate was to be held were not finalised until September 1922. Article 25 of the mandate specified that the eastern area (then known as Transjordan

or Transjordania) did not have to be subject to all parts of the Mandate, notably the provisions regarding a Jewish national home. This was used by the British as one rationale to establish an autonomous Arab state under the mandate, which it saw as at least partially fulfilling the undertakings in the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence

. On 11 April 1921 the British passed administration of the eastern region of the British Mandate to the Hashemite

Arab dynasty from the Hejaz

region (a region located in present day Saudi Arabia

) and on 15 May 1923 recognized it as a state, thereby eliminating Jewish national aspirations on that part of the British Mandate of Palestine. The mandate over Transjordan ended on 22 May 1946 when the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (later Jordan

) gained independence.

Palestinian nationalism

was marked by a reaction to the Zionist movement

and to Jewish settlement in Palestine as well as by a desire for self-determination by the Arab population in the region. Jewish immigration to Palestine continued to grow significantly during the period of the British Mandate in Palestine, mainly due to the growth of anti-Semitism in Europe. Between 1919 and 1926, 90,000 immigrants arrived in Palestine because of the anti-Semitic manifestations, such as the pogroms in Ukraine

in which 100,000 Jews were killed. Some of these immigrants were absorbed in Jewish communities established on lands purchased legally by Zionist agencies from absentee landlords. In some cases, a large acquisition of lands, from absentee landlords, led to the replacement of the fellah

in tenant farmer

s with European Jewish settlers, causing Palestinian Arabs to feel dispossessed. Jewish immigration to Palestine was especially significant after the rise of the Nazis to power in Germany

, following which the Jewish population in Palestine doubled.

The Arab population in Palestine opposed the increase of the Jewish population because they perceived the massive influx of Jewish immigrants as a real threat to their national identity and to their attribution to the surrounding Arabic countries. Following this, during the 1920s relations between the Jewish and Arab populations deteriorated and the hostility between the two groups intensified. The Arab population of the Palestine region who opposed the Yishuv

The Arab population in Palestine opposed the increase of the Jewish population because they perceived the massive influx of Jewish immigrants as a real threat to their national identity and to their attribution to the surrounding Arabic countries. Following this, during the 1920s relations between the Jewish and Arab populations deteriorated and the hostility between the two groups intensified. The Arab population of the Palestine region who opposed the Yishuv

and the British Pro-Zionist policies began to use violence

and terror

against the Jewish population. Arab gangs committed terrorism and murder against Jewish convoys and Jewish residents.

From 1920 to 1948 the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

became the leader of the Palestinian Arab movement

and played a key role in inciting religious riots against the Jewish population in Palestine. The Mufti stirred religious passions against Jews by alleging that Jews were seeking to rebuild the Jewish Temple

on the site of the Dome of the Rock

and Al-Aqsa Mosque

. He tried to gain control of the Western Wall

(the Kotel), saying that it was sacred to the Muslims.

The first major riots against the Jewish population in Palestine were the Jaffa riots

in 1921. As a result of the Jaffa riots, the Haganah

was founded as a defense force for the Jewish population of the British Mandate for Palestine. Religious tension over the Kotel

and the escalation of the tensions between the Arab and Jewish populations led to the 1929 Palestine riots

. In these religious-nationalist riots, Jews were massacred in Hebron

. Devastation also took place in Safed

and Jerusalem. In 1936, as Europe was preparing for war, the Supreme Muslim Council

in Palestine, led by Amin al-Husayni, instigated the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine in which Palestinian Arabs rioted and murdered Jews in various cities. In 1937 Amin al-Husayni, who was wanted by the British, fled Palestine and took refuge successively in Lebanon, Iraq, Italy and finally Nazi Germany

.

The British responded to the outbreaks of violence with the Haycraft Commission of Inquiry

(1921), the Shaw Report

(1930), the Peel Commission of 1936-1937, the Woodhead Commission

(1938) and the White Paper of 1939

.

The Peel Commission of 1937 was the first to propose a two-state solution

to the conflict, whereby Palestine would be divided into two states: one Arab state and one Jewish state. The Jewish state would include the coastal plain

, Jezreel Valley

, Beit She'an and the Galilee

, while the and Arab state would include Transjordan

, Judea and Samaria

, the Jordan Valley

, and the Negev

. The Jewish leadership in Palestine had differences of opinion regarding the proposal of the Peel Commission. The Arab leadership in Palestine rejected the conclusions and refused to share any land in Palestine with the Jewish population. The rejection of the Peel Commission's proposal by both parties led to the establishment of the Woodhead Commission

, which rejected the non-applicable proposal of the Peel Commission.

In May 1939 the British government released a new policy paper

which sought to implement a one-state solution in Palestine, significantly reduced the number of Jewish immigrants allowed to enter Palestine by establishing a quota for Jewish immigration which was set by the British government in the short-term and which would be set by the Arab leadership in the long-term. The quota also placed restrictions on the rights of Jews to buy land from Arabs, in an attempt to limit the socio-political damage. These restrictions remained until the end of the mandate period, a period which occurred in parallel with World War II

and the Holocaust, during which many Jewish refugees tried to escape from Europe. As a result, during the 1930s and 1940s the leadership of the Yishuv

arranged a couple of illegal immigration

waves of Jews to the British Mandate of Palestine

(see also Aliyah Bet), which caused even more tensions in the region.

Ben-Gurion said he wanted to "concentrate the masses of our people in this country [Palestine] and its environs." When he proposed accepting the Peel proposals in 1937, which included a Jewish state in part of Palestine, Ben-Gurion told the twentieth Zionist Congress, "The Jewish state now being offered to us is not the Zionist objective. [...] But it can serve as a decisive stage along the path to greater Zionist implementation. It will consolidate in Palestine, within the shortest possible time, the real Jewish force, which will lead us to our historic goal. In a discussion in the Jewish Agency he said that he wanted a Jewish-Arab agreement "on the assumption that after we become a strong force, as a result of the creation of the state, we shall abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine."

During the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine ties were made between the Arab leadership in Palestine and the Nazi movement

During the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine ties were made between the Arab leadership in Palestine and the Nazi movement

in Germany. These connections led to cooperation between the Palestinian national movement and the Axis powers

later on during World War II

. In May 1941 Amin al-Husayni issued a fatwa

for a holy war

against Britain. In 1941 during a meeting with Adolf Hitler

Amin al-Husayni asked Germany to oppose, as part of the Arab struggle for independence, the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine. He received a promise from Hitler that Germany would eliminate the existing Jewish foundations in Palestine after the Germans had gained victory in the war. During the war Amin al-Husayni joined the Nazis, serving with the Waffen SS in Bosnia

and Yugoslavia. In addition, during the war a joint Palestinian-Nazi military operation

was held in the region of Palestine. These factors caused a deterioration in the relations between the Palestinian leadership and the British, which turned to collaborate with the Yeshuv during the period known as the 200 days of dread.

After World War II, as a result of the British policies, the Jewish resistance organizations united and established the Jewish Resistance Movement

which coordinated armed attacks against the British military which took place between 1945 and 1946. Following the King David Hotel bombing

(in which the Irgun

blew up the King David Hotel

in Jerusalem, the headquarters of the British administration), which shocked the public because of the deaths of many innocent civilians, the Jewish Resistance Movement was disassembled in 1946. The leadership of the Yishuv decided instead to concentrate their efforts on the illegal immigration and began to organize a massive immigration of European Jewish refugees to Palestine using small boats operating in secrecy, many of which were captured at sea by the British and imprisoned in camps on Cyprus. About 70,000 Jews were brought to Palestine in this way in 1946 and 1947. Details of the Holocaust

had a major effect on the situation in Palestine and propelled large support for the Zionist cause.

The newly formed United Nations

The newly formed United Nations

recommended that Mandatory Palestine be split into three parts—a Jewish State with a majority Jewish population, an Arab State with a majority Arab population, and an International Zone comprising Jerusalem and the surrounding area where the Jewish and Arab populations would be roughly equal. Resolution 181 decided the size of land allotted to each party. The Jewish State was supposed to be roughly 5700 square miles (14,762.9 km²) in size and was supposed to contain a sizable Arab minority population. The Arab state was supposed to comprise roughly 4300 square miles (11,136.9 km²) and would contain a tiny Jewish population. Neither state would be contiguous. Jerusalem and Bethlehem

were to be put under the control of the United Nations. Neither side was satisfied with the Partition Plan. The Jews disliked losing Jerusalem—which had a majority Jewish population at that time—and worried about the tenability of a noncontiguous state. However, most of the Jews in Palestine accepted the plan, and the Jewish Agency (the de facto government of the Yishuv

) campaigned fervently for its approval. The more extreme Jewish groups, such as the Irgun

, rejected the plan. The Arab leadership argued that it violated the rights of the majority of the people in Palestine, which at the time was 67% non-Jewish (1,237,000) and 33% Jewish (608,000). Arab leaders also argued a large number of Arabs would be trapped in the Jewish State. Every major Arab leader objected in principle to the right of the Jews to an independent state in Palestine, reflecting the policies of the Arab League.

The UN General Assembly voted on the Partition Plan on November 29, 1947. Thirty-three states voted in favor of the Plan, while 13 countries opposed it. Ten countries abstained from the vote. The Yishuv accepted the plan, but the Arabs in Palestine and the surrounding Arab states rejected the plan. The Arab countries (all of which had opposed the plan) proposed to query the International Court of Justice

on the competence of the General Assembly to partition a country against the wishes of the majority of its inhabitants, but were again defeated. The division was to take effect on the date of British withdrawal from the territory (May 15, 1948).

The approval of the plan sparked attacks carried out by Arab irregulars against the Jewish population in Palestine. Fighting began almost as soon as the plan was approved. Shooting, stoning, and rioting continued apace in the following days. The consulates of Poland

and Sweden

, both of whose governments had voted for partition, were attacked. Bombs were thrown into cafes, Molotov cocktail

s were hurled at shops, and a synagogue

was set on fire. As the British evacuation from the region progressed, the violence became more prevalent. Murders, reprisals, and counter-reprisals came fast on each others' heels, resulting in dozens of victims killed on both sides in the process. The sanguinary impasse persisted as no force intervened to put a stop to the escalating cycles of violence. During the first two months of the war, about 1,000 people were killed and 2,000 injured. By the end of March, the figure had risen to 2,000 dead and 4,000 wounded.

On May 14, one day before the British Mandate expired, David Ben-Gurion

On May 14, one day before the British Mandate expired, David Ben-Gurion

declared the establishment of the State of Israel

. The declaration of the state referred to the decision of the UN General Assembly as a legal justification for the establishment of the state. In accordance with the UN Resolution, the Declaration promised that the State of Israel would ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex, and guaranteed freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture.

The termination of the British mandate over Palestine and the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel sparked a full-scale war (1948 Arab–Israeli War) which erupted after May 14, 1948. On 15–16 May, the four armies of Jordan

The termination of the British mandate over Palestine and the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel sparked a full-scale war (1948 Arab–Israeli War) which erupted after May 14, 1948. On 15–16 May, the four armies of Jordan

, Syria

, Egypt

and Iraq

invaded the newly self-declared state followed not long after by units from Lebanon

. While Arab commanders ordered villagers to evacuate for military purposes in isolated areas, there is no evidence that the Arab leadership made a blanket call for evacuation and in fact most urged Palestinians to stay in their homes. Assaults by the Haganah

on major Arab population centers like Jaffa and Haifa as well as expulsions carried out by groups like the Irgun

and Lehi

such as at Deir Yassin

and Lydda led to the exodus of large portions of the Arab masses. Factors such as the earlier flight by the Palestinian elite and the psychological effects of Jewish atrocities (stories which both sides propagated) also played important roles in the Palestinian flight.

The war resulted in an Israeli victory, with Israel annexing territory beyond the partition borders for a proposed Jewish state and into the borders for a proposed Palestinian Arab state. Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt signed the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The war resulted in an Israeli victory, with Israel annexing territory beyond the partition borders for a proposed Jewish state and into the borders for a proposed Palestinian Arab state. Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt signed the 1949 Armistice Agreements

with Israel. The remaining territories, the Gaza Strip

and the West Bank

, were occupied by Egypt

and Transjordan

, respectively. Jordan also annexed East Jerusalem

while Israel administered west Jerusalem

. In 1950, The West Bank was unilaterally incorporated into Jordan.

Due to the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, about 856,000 Jews fled or were expelled

from their homes in Arab countries and most were forced to abandon their property. Jews from Libya

, Iraq

, Yemen

, Syria

, Lebanon

and North Africa

left due to physical and political insecurity, with the majority being forced to abandon their properties. 260,000 reached Israel in 1948-1951, 600,000 by 1972. Additionally, due to the war, between 700,000 and 750,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled

from the area that became Israel and became what is known today as the Palestinian refugee

s. The Palestinian refugees were not allowed to return to Israel and most of the neighboring Arab states, with the exception of Transjordan

, denied granting them - or their descendants - citizenship. In 1949, Israel offered to allow some members of families that had been separated during the war to return, to release refugee accounts frozen in Israeli banks, and to repatriate 100,000 refugees. The Arab states rejected this compromise, at least in part because they were unwilling to take any action that might be construed as recognition of Israel. As of today, most of them still live in refugee camps and the question of how their situation should be resolved remains one of the main issues of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

While most of the Palestinian Arab population that remained in Israel after the war was granted an Israeli citizenship

, Arab Israelis were subject to martial law up to 1966. A variety of legal measures facilitated the transfer of land abandoned by Arabs to state ownership. In 1966, security restrictions placed on Arab citizens of Israel were lifted completely, the government set about dismantling most of the discriminatory laws, and Arab citizens of Israel

were granted the same rights as Jewish citizens.

After the 1948 war, some of the Palestinian refugees who lived in camps in the West Bank within Jordan

ian controlled territory, the Gaza Strip Egypt

ian controlled territory and Syria

tried to return by infiltration

into Israeli territory, and some of those Palestinians who had remained in Israel were declared infiltrators by Israel and were deported. Ben-Gurion emphatically rejected the return of refugees in the Israeli Cabinet decision of June 1948 reiterated in a letter to the UN of August 2, 1949 containing the text of a statement made by Moshe Sharett on August 1, 1948 where the basic attitude of the Israeli Government was that a solution must be sought, not through the return of the refugees to Israel, but through the resettlement of the Palestinian Arab refugee population in other states.

The buildup of the conflict along the Jordanian border went through gradual stages. Building up from small Israeli raids with Palestinian counter raids through to the major Israeli incursions, Beit Jalla

, Qibya massacre

, Ma'ale Akrabim massacre

, Nahalin reprisal raid, Rantis and Falameh reprisal raid. The Lavon Affair

led to a deeper distrust of Jews in Egypt, from whose community key agents in the operation had been recruited, and as a result Egypt retaliated against its Jewish community. It was only after Israel's raid on an Egyptian military outpost in Gaza in February 1955 that the Egyptian government began to actively sponsor, train, and arm the Palestinian volunteers from Gaza as Fedayeen

units which committed raids into Israel.

Following years of attacks by the Palestinian Fedayeen, the Palestine Liberation Organization

(PLO) was established in 1964. Its goal was the liberation of Palestine through armed struggle. The original PLO Charter stated the desire for a Palestinian state established within the entirety of the borders of the British mandate

prior to the 1948 war (i.e. the current boundaries of the State of Israel) and said it is a "national duty ... to purge the Zionist presence from Palestine." It also called for a right of return

and self-determination

for Palestinians.

An Israeli raid on an Egyptian military outpost in Gaza in February 1955, resulted in 37 Egyptian soldiers killed. Soon after, the Egyptian government began to actively sponsor, train and arm the Palestinian volunteers from Gaza as Fedayeen

units, which committed raids into Israel. In 1967, after years of Egyptian-aided Palestinian Fedayeen attacks stemming from the Gaza Strip

, the Egyptian expulsion of UNEF, Egypt's amassing of an increased number of troops in the Sinai Peninsula

, and several other threatening gestures from other neighboring Arab nations, Israel launched a preemptive strike

against Egypt. The strike and the operations that followed became known as the Six-Day War

. At the end of the Six-Day War, Israel had captured, among other territories, the Gaza Strip

from Egypt and the West Bank

from Jordan (including East Jerusalem

). Shortly after Israel seized control over Jerusalem, Israel asserted sovereignty over the entire city of Jerusalem and the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem were given a permanent resident status in Israel. The status of the city as Israel's capital and the disputed status

of the West Bank and Gaza Strip created a new set of contentious issues in the conflict. This meant that Israel controlled the entire former British mandate of Palestine that under the Balfour Declaration was supposed to allow a Jewish state within its borders. The fact that Palestine was never a sovereign state gave the Israelis subsequent support for their argument that they did not occupy these territories, and therefore did not break the Fourth Accord of the Geneva Conventions

and international law. Following the Six-Day War, the United Nations Security Council

issued a resolution

with a clause affirming "the necessity ... for achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem," referring to the Palestinian refugee

problem.

. In July 1968 armed, non-state actors such as Fatah

and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

achieved the majority of the Palestinian National Council votes, and on February 3, 1969, at the Palestinian National Council

in Cairo

, the leader of the Fatah, Yasser Arafat

was elected as the chairman of the PLO. From the start, the organization used armed violence against civilian and military targets in the conflict with Israel. The PLO tried to take over the population of the West Bank, but the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) deported them into Jordan where they began to act against the Jordanian rule (Palestinians in Jordan comprised about 70% of the total population, which mostly consisted of refugees) and from there attacked Israel numerous times, using the infiltration of terrorists and shooting Katyusha rockets. This led to retaliation from Israel.

In the late 1960s, tensions between Palestinians and the Jordanian government increased greatly. In September 1970

a military struggle was held between Jordan and the Palestinian armed organizations. King Hussein of Jordan

was able to quell the Palestinian revolt. During the armed conflict, tens of thousands of people were killed, the vast majority of whom were Palestinians. The fighting continued until July 1971 with the expulsion of the PLO to Lebanon. A large number of Palestinians immigrated to Lebanon after Black September and joined the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees already there. The center of PLO activity then shifted to Lebanon

, where the 1969 Cairo agreement

gave the Palestinians autonomy within the south of the country. The area controlled by the PLO became known by the international press and locals as "Fatahland" and contributed to the 1975-1990 Lebanese Civil War

.

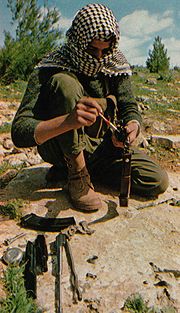

The PLO took advantage of its control southern Lebanon in order to launch Katyusha rocket attacks at Galilee villages and execute terror attacks on the northern border. At the beginning of the 1970s the Palestinian terror organizations, headed by the PLO and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The PLO took advantage of its control southern Lebanon in order to launch Katyusha rocket attacks at Galilee villages and execute terror attacks on the northern border. At the beginning of the 1970s the Palestinian terror organizations, headed by the PLO and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

waged an international campaign against Israelis, primarily in Europe. In an attempt to publicize the Palestinian cause, frustrated Palestinian guerrilla groups in Lebanon

attacked Israeli civilian 'targets' like school

s, bus

es and apartment blocks, with occasional attacks abroad—for example, at embassies or airports—and with the hijacking of airliners. The peak of the Palestinian terrorism wave against Israelis occurred in 1972 and took form in several acts of terrorism, most prominently the Sabena Flight 572 hijacking, the Lod Airport massacre

and the Munich massacre

.

The Munich massacre was perpetrated during the 1972 Summer Olympics

The Munich massacre was perpetrated during the 1972 Summer Olympics

in Munich

. 11 members of the Israeli team were taken hostage by Palestinian terrorists

. A botched German rescue attempt led to the death of all 11 Israeli athletes and coaches. Five of the terrorists were shot and three survived unharmed. The three surviving Palestinians were released without charge by the German authorities a month later. The Israeli government responded with an assassination campaign

against the organizers and a raid on the PLO headquarters in Lebanon. Other notable events include the hijacking of several civilian airliners, the Savoy Hotel attack

, the Zion Square explosive refrigerator

and the Coastal Road massacre

. During the 1970s and the early 1980s, Israel suffered attacks from PLO bases in Lebanon, such as the Avivim school bus massacre

in 1970 and the Ma'alot massacre

in 1974 in which Palestinians attacked a school in Ma'alot killing twenty-two children.

In 1973 The Syrian and Egyptian armies launched the Yom Kippur War

, a well-planned surprise attack against Israel. The Egyptians and Syrians advanced during the first 24–48 hours, after which momentum began to swing in Israel's favor. Eventually a Disengagement of Forces agreement was signed between the parties and a ceasefire took effect that ended the war. The Yom Kippur War paved the way for the Camp David Accords

in 1978, which set a precedent for future peace negotiations.

In 1974 the PLO adopted the Ten Point Program

, which called for the establishment of a national authority "over every part of Palestinian territory that is liberated" with the aim of "completing the liberation of all Palestinian territory". The program implied that the liberation of Palestine may be partial (at least, at some stage), and though it emphasized armed struggle, it did not exclude other means. This allowed the PLO to engage in diplomatic channels, and provided validation for future compromises made by the Palestinian leadership.

In the mid-1970s many attempts were made by Gush Emunim

movement to establish outposts or resettle former Jewish areas in the West Bank

and Gaza

Strip. Initially the Israeli government forcibly disbanded these settlements. However, in the absence of peace talks to determine the future of these and other occupied territories, Israel ceased enforcement of the original ban on settlement, which led to the founding of the first settlements in these regions.

In July 1976, an Air France

plane carrying 260 people was hijacked by Palestinian

and German

terrorists and flown to Uganda. There, the Germans separated the Jewish passengers from the Non-Jewish passengers, releasing the non-Jews. The hijackers threatened to kill the remaining 100-odd Jewish passengers (and the French crew who had refused to leave). Israel responded with a rescue operation

in which the kidnapped Jews were freed.

The rise of the Likud party to the government in 1977

led to the establishment of a large number of Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

On March 11, 1978, a force of nearly a dozen armed Palestinian terrorists landed their boats near a major coastal road in Israel. There they hijacked a bus

and sprayed gunfire inside and at passing vehicles, killing thirty-seven civilians. In response, the IDF launched Operation Litani three days later, with the goal of taking control of Southern Lebanon up to the Litani River. The IDF achieved this goal, and the PLO withdrew to the north into Beirut. After Israel withdrew from Lebanon, Fatah forces resumed firing rockets into the Galilee region of Israel. During the years following operation Litani, many diplomatic efforts were made which tried to end the war on the Israeli-Lebanese border, including the effort of Philip Habib

, the emissary of Ronald Reagan

who in the summer of 1981 managed to arrange a lasting cease-fire between Israel and the PLO which lasted about a year.

Israel ended the ceasefire after an assassination attempt on the Israeli Ambassador in the Britain, Shlomo Argov, in mid-1982 (which was made by Abu Nidal's organization that was ostracized from the PLO). This led Israel to invade Lebanon in the 1982 Lebanon War

on June 6, 1982 with the aim to protect the North of Israel from terrorist attacks. IDF invaded Lebanon and even occupied Beirut. To end the siege, the US and European governments brokered an agreement guaranteeing safe passage for Arafat and Fatah – guarded by a multinational force – to exile in Tunis

. During the war, Israeli allied Phalangist Christian Arab militias carried out the bloody Sabra and Shatila Massacre

in which 700-3,500 unarmed Palestinians were killed by the Phalangist militias while the Israeli troops surrounded the camps with tanks and checkpoints, monitoring entrances and exits. For its involvement in the Lebanese war and its indirect responsibility for the Sabra and Shatila Massacre, Israel was heavily criticized, including from within. An Israeli Commission of Inquiry found that Israeli military personnel, among them defense minister and future prime minister

Ariel Sharon

, had several times become aware that a massacre was in progress without taking serious steps to stop it, leading to his resignation as Israel's Defense Minister. In June 1985, Israel withdrew most of its troops from Lebanon, leaving a residual Israeli force and an Israeli-supported militia

in southern Lebanon as a "security zone

" and buffer against attacks on its northern territory.

Meanwhile, the PLO led an international diplomatic front against Israel in Tunis. Following the wave of terror attacks including the murder on MS Achille Lauro

in October 1985, Israel bombed the PLO commandership in Tunis during Operation Wooden Leg

.

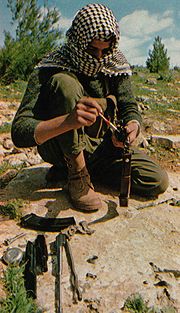

The continuing establishment of the Israeli settlements and continuing Israeli occupation in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip led to the first Palestinian Intifada

(uprising) in December 1987, which lasted until the Madrid Conference of 1991

, despite Israeli attempts to suppress it. It was a partially spontaneous uprising, but by January 1988, it was already under the direction from the PLO headquarters in Tunis, which carried out ongoing terrorist attacks targeting Israeli civilians. The riots escalated daily throughout the territories and were especially severe in the Gaza Strip. The Intifada was renowned by its stone-throwing demonstrations by youth against the heavily-armed Israeli Defense Forces. Over the course of the First Intifada, a total 1,551 Palestinians and 422 Israelis were killed. In 1987, Ahmed Yassin

co-founded Hamas

with Abdel Aziz al-Rantissi

. Since then, Hamas has been involved in what it calls "armed resistance" against Israel, which includes mainly terrorist acts against Israeli civilian population.

On November 15, 1988, a year after the outbreak of the first intifada, the PLO declared the establishment of the Palestinian state in Algiers

. The proclaimed "State of Palestine" is not and has never actually been an independent state, as it has never had sovereignty over any territory in history. The declaration is generally interpreted to have recognized Israel within its pre-1967 boundaries, and its right to exist. Following this declaration, the United States and many other countries recognized the PLO.

Prior to the Gulf War

in 1990-91, Arafat supported Saddam Hussein

's invasion of Kuwait

and opposed the US-led coalition attack on Iraq. Arafat's decision also severed relations with Egypt

and many of the oil

-producing Arab states that supported the US-led coalition. Many in the US also used Arafat's position as a reason to disregard his claims to being a partner for peace. After the end of hostilities, many Arab states that backed the coalition cut off funds to the PLO and bringing the PLO to the brink of crisis.

In the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War, the coalition's victory in the Gulf War opened a new opportunity to advance the peace process. The U.S launched a diplomatic initiative in cooperation with Russia which resulted in the October 1991 Madrid peace conference

. The conference was hosted by the government of Spain and co-sponsored by the USA and the USSR. The Madrid peace conference was an early attempt by the international community to start a peace process

through negotiations involving Israel

and the Palestinians, as well as Arab countries including Syria

, Lebanon

, and Jordan

. The Palestinian team, due to Israeli objections, was initially formally a part of a joint Palestinian-Jordanian delegation and consisted of Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza without open PLO associations.

In January 1993, Israeli and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) negotiators began secret negotiations in Oslo, Norway

In January 1993, Israeli and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) negotiators began secret negotiations in Oslo, Norway

. On September 9, 1993, Yasser Arafat sent a letter to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin

, stating that the PLO officially recognized Israel's right to exist and officially renouncing terrorism

. On September 13, Arafat and Rabin signed a Declaration of Principles in Washington, D.C.

, on the basis of the negotiations between Israeli and Palestinian teams in Oslo, Norway. The declaration was a major conceptual breakthrough achieved outside of the Madrid framework, which specifically barred foreign-residing PLO leaders from the negotiation process. After this, a long process of negotiation known as the "Oslo peace process" began.

During the Oslo peace process throughout the 1990s, as both sides obligated to work towards a two-state solution

, Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization negotiated, unsuccessfully, and tried to reach to a mutual agreement.

One of the main features of the Oslo Peace Process was the establishment of the autonomous governmental authority, the Palestinian Authority (PA) and its associated governing institutions to administer Palestinian communities in the Gaza Strip

and the West Bank

. During the Oslo peace process throughout the 1990s, the Palestinian Authority was ceded authority from Israel over various regions of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This process gave it governmental and economic authority over many Palestinian communities. It also gave the PA many of the components of a modern government and society, including a Palestinian police force, legislature, and other institutions. In return for these concessions, the Palestinian Authority was asked to promote tolerance for Israel within Palestinian society, and acceptance of Israel's right to exist.

One of the most contentious issues surrounding this peace process is whether the PA in fact met its obligations to promote tolerance. There is specific evidence that the PA actively funded and supported many terrorist activities and groups. Palestinians stated that any terrorist acts stemmed from Israel not having conceded enough land and political power to win support among ordinary Palestinians. Israelis stated that these acts of terrorism were because the PA openly encouraged and supported incitement against Israel, and terrorism. There was increasing disagreement and debate among Israelis about the amount of positive results and benefits produced by the Oslo process. Supporters said it was producing advances leading to a viable Palestinian society which would promote genuine acceptance of Israel. Opponents said that concessions were merely emboldening extremist elements to commit more violence in order to win further concessions, without providing any real acceptance, benefits, goodwill, or reconciliation for Israel in return.

In February 1994 during the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre

a follower of the Kach

movement killed 25 Palestinian-Arabs at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron

. As an act of revenge to the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre, in April 1994, Hamas launched suicide bomber attacks targeting Israeli civilian population in many locations throughout Israel, however, once the Hamas started to the use these means it became a regular pattern of action against Israel.

On September 28, 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin

and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat

signed the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in Washington. the agreement marked the conclusion of the first stage of negotiations between Israel and the PLO. The agreement allowed the PLO leadership to relocate to the occupied territories and granted autonomy to the Palestinians with talks to follow regarding final status. In return the Palestinians recognized Israel's right to exist and promised to abstain from use of terror. However the agreement was opposed by the Hamas and other Palestinian factions, whom at this point were already committing suicide bomber attacks throughout Israel.

Tensions in Israel, arising from the continuation of terrorism and anger at loss of territory, led to the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin

by a right-wing Jewish radical on November 4, 1995. Upon Rabin's assassination, the Israeli prime minister's post was filled by Shimon Peres

. Peres continued Rabin's policies in supporting the peace process.

In 1996, increasing Israeli doubts about the peace process, led to Benjamin Netanyahu

of the Likud Party winning the election, mainly due to his promise to use a more rigid line in the negotiations with the Palestinian Authority. Netanyahu raised many questions about many central premises of the Oslo process. One of his main points was disagreement with the Oslo premise that the negotiations should proceed in stages, meaning that concessions should be made to Palestinians before any resolution was reached on major issues, such as the status of Jerusalem, and the amending of the Palestinian National Charter. Oslo supporters had claimed that the multi-stage approach would build goodwill among Palestinians and would propel them to seek reconciliation when these major issues were raised in later stages. Netanyahu said that these concessions only gave encouragement to extremist elements, without receiving any tangible gestures in return. He called for tangible gestures of Palestinian goodwill in return for Israeli concessions.

In January 1996 Israel assassinated the chief bombmaker of Hamas, Yahya Ayyash

. In reaction to this, Hamas carried out a wave of suicide attacks in Israel. Following these attacks the Palestinian Authority began to act against the Hamas and oppress their activity.

In January 1997 Netanyahu signed the Hebron Protocol with the Palestinian Authority, resulting in the redeployment of Israeli forces in Hebron

and the turnover of civilian authority in much of the area to the Palestinian Authority.

In 1997, after two deadly suicide attacks in Jerusalem by the Hamas, Israeli secret agents were sent to Jordan to eliminate the political head of the Department of Hamas, Khaled Mashal

, using a special poison (See the assassination attempt on Khaled Mashal). Nevertheless, the operation entangled and the secret agents were captured. In return of their release Israel sent over the medicine which saved his life and freed a dozen of Palestinian prisoners including Sheikh Ahmad Yassin. This release and the increase of the security forces of the Palestinian Authority, led to a cease-fire in the suicide attacks until the outbreak of the Second Intifada.

Eventually, the lack of progress of the peace process led to new negotiations, which produced the Wye River Memorandum

, which detailed the steps to be taken by the Israeli government and Palestinian Authority to implement the earlier Interim Agreement of 1995. It was signed by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, and on November 17, 1998, Israel's 120 member parliament, the Knesset

, approved the Wye River Memorandum by a vote of 75-19.

In 1999, Ehud Barak

was elected prime minister. Barak continued Rabin's policies in supporting the peace process. In 2000, 18 years after Israel occupied Southern Lebanon in the 1982 Lebanon War

, the occupation ended as Israel unilaterally withdrew its remaining forces from the "security zone

" in southern Lebanon.

As the violence increased with little hope for diplomacy, in July 2000 the Camp David 2000 Summit

was held which was aimed at reaching a "final status" agreement. The summit collapsed after Yasser Arafat would not accept a proposal drafted by American and Israeli negotiators. Barak was prepared to offer the entire Gaza Strip, a Palestinian capital in a part of East Jerusalem, 73% of the West Bank (excluding eastern Jerusalem) raising to 90-94% after 10–25 years, and financial reparations for Palestinian refugees for peace. Arafat turned down the offer without making a counter-offer.

After the signing of the Oslo Accords failed to bring about a Palestinian state, in September 2000 the Second Intifada (uprising) broke out, a period of intensified Palestinian-Israeli violence, which has been taking place until the present day. The Second Intifada has caused thousands of victims on both sides, both among combatants and among civilians, and has been more deadly than the first Intifada. Many Palestinians consider the Second Intifada to be a legitimate war of national liberation against foreign occupation, whereas many Israelis consider it to be a terrorist campaign.

After the signing of the Oslo Accords failed to bring about a Palestinian state, in September 2000 the Second Intifada (uprising) broke out, a period of intensified Palestinian-Israeli violence, which has been taking place until the present day. The Second Intifada has caused thousands of victims on both sides, both among combatants and among civilians, and has been more deadly than the first Intifada. Many Palestinians consider the Second Intifada to be a legitimate war of national liberation against foreign occupation, whereas many Israelis consider it to be a terrorist campaign.

The failure of the peace process and the eruption of the Second Intifada, which included increased Palestinian terror attacks being made against Israeli civilians, led much of the Israeli public and political leadership to lose confidence in the Palestinian Authority as a peace partner. Due to an increase in terror attacks during the Second Intifada, mainly carried out by Hamas against Israeli civilians, Israeli troops began conducting regular raids and arrests inside the West Bank. In addition, Israel increased the selective assassinations, initially aimed at active terrorist fighters and later on aimed at the terrorist leadership as well, including Sheikh Ahmad Yassin. This policy spurred controversy within Israel and worldwide.

After the collapse of Barak's government, Ariel Sharon

was elected Prime Minister on February 6, 2001. Sharon invited the Israeli Labor Party into the coalition to shore up support for the disengagement plan. Due to the deterioration of the political situation, he refused to continue negotiations with the Palestinian Authority at the Taba Summit

, or under any aspect of the Oslo Accords.

At the Beirut Summit in 2002, the Arab League

proposed an alternative political plan

aimed at ending the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but it was rejected by Israel (mostly because it demanded a Palestinian right of return

).

Following a period of relative restraint on the part of Israel, after a lethal suicide attack in the Park Hotel in Netanya

which happened on March 27, 2002, in which 30 Jews were murdered, Sharon ordered Operation Defensive Shield

, a large-scale military operation carried out by the Israel Defense Forces

between March 29 until May 10, 2002 in Palestinian cities in the West Bank. The operation contributed significantly to the reduction of Palestinian terror attacks in Israel.

As part of the efforts to fight Palestinian terrorism, in June 2002, Israel began construction of the West Bank Fence

along the Green Line

border. After the barrier went up, Palestinian suicide bombings and other attacks across Israel dropped by 90%. However, this barrier became a major issue of contention between the two sides.

Following the severe economic and security situation in Israel, the Likud Party headed by Ariel Sharon won the Israeli elections in January 2003 in an overwhelming victory. The elections led to a temporary truce between Israel and the Palestinians and to the Aquba summit in the May 2003 in which Sharon endorsed the Road Map for Peace

put forth by the United States, European Union

, and Russia, which opened a dialogue with Mahmud Abbas, and announced his commitment to the creation of a Palestinian state in the future. Following the endorsing of the Road Map, the Quartet on the Middle East

was established, consisting of representatives from the United States, Russia, EU and UN as an intermediary body of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

On March 19, 2003, Arafat appointed Mahmoud Abbas

as the Prime Minister. The rest of Abbas's term as prime minister continued to be characterized by numerous conflicts between him and Arafat over the distribution of power between the two. The United States and Israel accused Arafat of constantly undermining Abbas and his government. Continuing violence and Israeli "target killings" of known terrorists forced Abbas to pledge a crackdown in order to uphold the Palestinian Authority's side of the Road Map for Peace. This led to a power struggle with Arafat over control of the Palestinian security services; Arafat refused to release control to Abbas, thus preventing him from using them in a crackdown on militants. Abbas resigned from the post of Prime Minister in October 2003, citing lack of support from Israel and the United States as well as "internal incitement" against his government.

In the end of 2003, Sharon embarked on a course of unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip

, while maintaining control of its coastline and airspace. Sharon's plan has been welcomed by both the Palestinian Authority and Israel's left wing as a step towards a final peace settlement. However, it has been greeted with opposition from within his own Likud party and from other right-wing Israelis, on national security, military, and religious grounds. In January 2005, Sharon formed a national unity government

that included representatives of Likud, Labor, and Meimad and Degel HaTorah as "out-of-government" supporters without any seats in the government (United Torah Judaism parties usually reject having ministerial offices as a policy). Between 16 and 30 August 2005, Sharon controversially expelled 9,480 Jewish settlers from 21 settlements in Gaza and four settlements in the northern West Bank. The disengagement plan was implemented in September 2005. Following the withdrawal, the Israeli town of Sderot

and other Israeli communities near the Gaza strip became subject to constant shelling

and mortar

bomb attacks from Gaza with only minimal Israeli response.

Following the November 2004 death of long-time Fatah party PLO leader and PA chairman Yasser Arafat

, Fatah member Mahmoud Abbas was elected President of the Palestinian National Authority

in January 2005.

The strengthening of the Hamas organization amongst the Palestinians, the gradual disintegration of the Palestinian Authority and the Fatah organization, and the Israeli disengagement plan and especially the death of Yasser Arafat led to the policy change of the Hamas movement in early 2005 which started putting greater emphasis to its political characteristics.

In 2006 Palestinian legislative elections

Hamas won a majority in the Palestinian Legislative Council

, prompting the United States and many European countries to cut off all funds to the Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, insisting that the Hamas must recognize Israel, renounce violence and accept previous peace pacts. Israel refused to negotiate with Hamas, since Hamas never renounced its beliefs that Israel has no right to exist and that the entire State of Israel is an illegal occupation which must be wiped out.

In June 2006 during a well-planned operation, Hamas managed to cross the border from Gaza, attack an Israeli tank, kill two IDF soldiers and kidnap wounded Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit

back into the Gaza Strip. Following the incident and in response to numerous rocket firings by Hamas from the Gaza Strip into southern Israel, fighting broke out between Hamas and Israel in the Gaza Strip (see 2006 Israel-Gaza conflict

).

In the summer of 2007 a Fatah–Hamas conflict

broke out, which eventually led Hamas taking control of the Gaza strip, which in practice divided the Palestinian Authority into two. Various forces affiliated with Fatah engaged in combat with Hamas, in numerous gun battles. Most Fatah leaders escaped to Egypt and the West Bank, while some were captured and killed. Fatah remained in control of the West Bank, and President Abbas formed a new governing coalition, which some critics of Fatah said subverts the Palestinian Constitution and excludes the majority government of Hamas.

In November 2007 the Annapolis Conference

was held. The conference marked the first time a two-state solution

was articulated as the mutually agreed-upon outline for addressing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The conference ended with the issuing of a joint statement from all parties.

A fragile six-month truce between Hamas and Israel

A fragile six-month truce between Hamas and Israel

expired on December 19, 2008. Hamas and Israel could not agree on conditions to extend the truce. Hamas blamed Israel for not lifting the Gaza Strip blockade, and for an Israeli raid on a purported tunnel, crossing the border into the Gaza Strip from Israel on November 4, which it held constituted a serious breach of the truce. Israel accuses Hamas of violating the truce citing the frequent rocket and mortar attacks on Israeli cities.

The Israeli operation began with an intense bombardment of the Gaza Strip

The Israeli operation began with an intense bombardment of the Gaza Strip

, targeting Hamas bases, police training camps, police headquarters and offices. Civilian infrastructure, including mosques, houses, medical facilities and schools, were also attacked. Israel has said many of these buildings were used by combatants, and as storage spaces for weapons and rockets. Hamas intensified its rocket and mortar attacks against targets in Israel throughout the conflict, hitting previously untargeted cities such as Beersheba

and Ashdod. On January 3, 2009, the Israeli ground invasion began.

The operation resulted in the deaths of more than 1,300 Palestinians. The IDF released a report stating that the vast majority of the dead were Hamas militants. The Palestinian Centre for Human Rights

reported that 926 of the 1,417 dead had been civilians and non-combatants.

Since 2009, the Obama administration

has repeatedly pressured the Israeli government led by Prime Minister

Benjamin Netanyahu

to freeze the growth of Israeli settlements in the West Bank

and reignite the peace process between Israel and the Palestinian people

. During President Obama's Cairo speech

on June 4, 2009 in which Obama addressed the Muslim world

Obama stated, among other things, that "The United States does not accept the legitimacy of continued Israeli settlements". "This construction violates previous agreements and undermines efforts to achieve peace. It is time for these settlements to stop." Following Obama's Cairo speech Netanyahu immediately called a special government meeting. On June 14, ten days after Obama's Cairo speech, Netanyahu gave a speech at Bar-Ilan University in which he endorsed, for the first time, a "Demilitarized Palestinian State", after two months of refusing to commit to anything other than a self-ruling autonomy when coming into office. The speech was widely seen as a response to Obama's speech. Netanyahu stated that he would accept a Palestinian state if Jerusalem were to remain the united capital of Israel

, the Palestinians would have no army, and the Palestinians would give up their demand for a right of return

. He also claimed the right for a "natural growth" in the existing Jewish settlements

in the West Bank

while their permanent status is up to further negotiation. In general, the address represented a complete turnaround for his previously hawkish positions against the peace process. The overture was quickly rejected by Palestinian leaders such as Hamas

spokesman Sami Abu Zuhri

, who called the speech "racist".

On 25 November 2009, Israel imposed a 10-month construction freeze on all of its settlements in the West Bank. Israel's decision was widely seen as due to pressure from the Obama administration, which urged the sides to seize the opportunity to resume talks. In his announcement Netanyahu called the move "a painful step that will encourage the peace process" and urged the Palestinians to respond. However, the Palestinians rejected the call and refused to enter negotiations, despite Israeli appeals to do so. Eventually, on September 2, United States launched direct negotiations between Israel and the PA in Washington

. Nevertheless, soon afterwards, when Israeli partial moratorium on settlement construction in the West Bank was about to expire, the Palestinian leadership announced that they plan to leave the negotiations if the moratorium is not renewed. Israel state that it would not renew this gesture of goodwill and urged the Palestinian leadership to continue the negotiations. Later on Israel offered to renew the moratorium in exchange for a PA recognition of Israel as the national homeland of the Jewish people. This request was rejected by the Palestinians leadership.

During September 2011 the Palestinian Authority (PA) led a diplomatic campaign

aimed at getting the recognition of the 66th Session

as the UN in the State of Palestine

within the 1967 borders

with East Jerusalem

as its capital. On September 23 PA Chairman Mahmoud Abbas delivered a harsh speech against Israel in the General Assembly of the United Nations in which he stated that the Palestinians would not recognize a Jewish state. That same day President Mahmoud Abbas

submitted a request to recognize the State of Palestine

as the 194th UN member to the Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

. The Security Council

has yet to vote on it. The decision has been labeled by the Israeli government as a unilateral step.

In October 2011, a deal was reached

between Israel and Hamas

, by which the kidnapped Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit

would be released in exchange for 1,027 Palestinians and Arab-Israeli prisoners, of them 280 were sentenced to life in prison for planning and perpetrating various terror attacks against Israeli targets. The military Hamas

leader Ahmed Jabari was quoted later as confirming that the prisoners released as part of the deal were collectively responsible for the killing of 569 Israeli civilians.

populations in Palestine

, Israel

and the Palestinian territories

spaning through the last two centuries which has been taken from census

results and official documents which mention demographic composition. See Demographics of Israel

and Demographics of the Palestinian territories

for a more detailed overview of the current demographics.

Israeli-Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is the ongoing conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. The conflict is wide-ranging, and the term is also used in reference to the earlier phases of the same conflict, between Jewish and Zionist yishuv and the Arab population living in Palestine under Ottoman or...

centers on conflicting, often mutually exclusive claims to the area called Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

by the Palestinians and the Land of Israel

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel is the Biblical name for the territory roughly corresponding to the area encompassed by the Southern Levant, also known as Canaan and Palestine, Promised Land and Holy Land. The belief that the area is a God-given homeland of the Jewish people is based on the narrative of the...

by Israeli Jews.

Historical overview

The historical overview below is divided into the main six time periods of the conflict which fundamentally differ from each other (see Periods of the conflict).National movements

Before World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

region, including Palestine, was under the control of the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

for nearly 400 years. Towards the end of the 19th century, Palestine, divided between the Vilayets of Damascus and Beirut and the Mustafiyyet of Jerusalem, was inhabited predominantly by Arab

Arab

Arab people, also known as Arabs , are a panethnicity primarily living in the Arab world, which is located in Western Asia and North Africa. They are identified as such on one or more of genealogical, linguistic, or cultural grounds, with tribal affiliations, and intra-tribal relationships playing...

Muslims, both farmers and Bedouin

Bedouin

The Bedouin are a part of a predominantly desert-dwelling Arab ethnic group traditionally divided into tribes or clans, known in Arabic as ..-Etymology:...

(principally in the Negev

Negev

The Negev is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The Arabs, including the native Bedouin population of the region, refer to the desert as al-Naqab. The origin of the word Neghebh is from the Hebrew root denoting 'dry'...

and Jordan valley

Jordan Rift Valley

The Jordan Rift Valley is an elongated depression located in modern-day Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian territories. This geographic region includes the Jordan River, Jordan Valley, Hula Valley, Lake Tiberias and the Dead Sea, the lowest land elevation on Earth...

), with smaller numbers of Christians

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

(predominantly Arab), Druze

Druze

The Druze are an esoteric, monotheistic religious community, found primarily in Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, which emerged during the 11th century from Ismailism. The Druze have an eclectic set of beliefs that incorporate several elements from Abrahamic religions, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism...

, Circassians and Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

(predominantly Sephardic

Sephardi Jews

Sephardi Jews is a general term referring to the descendants of the Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula before their expulsion in the Spanish Inquisition. It can also refer to those who use a Sephardic style of liturgy or would otherwise define themselves in terms of the Jewish customs and...

). At that time most of the Jews worldwide lived outside of Palestine, predominantly in eastern

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

and central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

, with significant communities in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Americas.

Zionism

Zionism is a Jewish political movement that, in its broadest sense, has supported the self-determination of the Jewish people in a sovereign Jewish national homeland. Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Zionist movement continues primarily to advocate on behalf of the Jewish state...

and Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and literature of the Arabs, calling for rejuvenation and political union in the Arab world...

. Though the Jewish aspiration to return to Zion had been part of Jewish religious thought for a millennia, the Jewish population of Europe and to some degree Middle East began to more actively discuss immigration back to the Land of Israel

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel is the Biblical name for the territory roughly corresponding to the area encompassed by the Southern Levant, also known as Canaan and Palestine, Promised Land and Holy Land. The belief that the area is a God-given homeland of the Jewish people is based on the narrative of the...

, and the re-establishment of the Jewish Nation in its national homeland, only during the 1870s

1870s

The 1870s continued the trends of the previous decade, as new empires, imperialism and militarism rose in Europe and Asia. America was recovering from the Civil War. Germany declared independence in 1871 and began its Second Reich. Labor unions and strikes occurred worldwide in the later part of...

and 1880s

1880s

The 1880s was the decade that spanned from January 1, 1880 to December 31, 1889. They occurred at the core period of the Second Industrial Revolution. Most Western countries experienced a large economic boom, due to the mass production of railroads and other more convenient methods of travel...

, largely as a solution to the widespread persecution of Jews due to anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

in Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

and Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

. As a result, the Zionist movement, the modern movement for the creation of a homeland for the Jewish people, was established as a political movement in 1897.

The Zionist movement called for the establishment of a nation-state

Nation-state

The nation state is a state that self-identifies as deriving its political legitimacy from serving as a sovereign entity for a nation as a sovereign territorial unit. The state is a political and geopolitical entity; the nation is a cultural and/or ethnic entity...

for the Jewish people in Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

, which would serve as a haven

Sanctuary

A sanctuary is any place of safety. They may be categorized into human and non-human .- Religious sanctuary :A religious sanctuary can be a sacred place , or a consecrated area of a church or temple around its tabernacle or altar.- Sanctuary as a sacred place :#Sanctuary as a sacred place:#:In...

for the Jews of the world

Jewish population

Jewish population refers to the number of Jews in the world. Precise figures are difficult to calculate because the definition of "Who is a Jew" is a source of controversy.-Total population:...

and in which they would have the right for self-determination

Self-determination

Self-determination is the principle in international law that nations have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no external compulsion or external interference...

. Zionists increasingly came to hold that this state should be in their historic homeland, which they referred to as the Land of Israel

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel is the Biblical name for the territory roughly corresponding to the area encompassed by the Southern Levant, also known as Canaan and Palestine, Promised Land and Holy Land. The belief that the area is a God-given homeland of the Jewish people is based on the narrative of the...

. The World Zionist Organization

World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization , or WZO, was founded as the Zionist Organization , or ZO, in 1897 at the First Zionist Congress, held from August 29 to August 31 in Basel, Switzerland...

and the Jewish National Fund

Jewish National Fund

The Jewish National Fund was founded in 1901 to buy and develop land in Ottoman Palestine for Jewish settlement. The JNF is a quasi-governmental, non-profit organisation...

encouraged immigration

Aliyah

Aliyah is the immigration of Jews to the Land of Israel . It is a basic tenet of Zionist ideology. The opposite action, emigration from Israel, is referred to as yerida . The return to the Holy Land has been a Jewish aspiration since the Babylonian exile...

and funded purchase of land, both under Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

rule and under British rule, in the region of Palestine. While Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and literature of the Arabs, calling for rejuvenation and political union in the Arab world...

, at least in an early form, and Syrian nationalism

Syrian nationalism

Syrian nationalism refers to the nationalism of Syria, or the Fertile Crescent as a cultural or political entity. It should not be confused with the Arab nationalism that is the official state doctrine of the Syrian Arab Republic's ruling Baath Party, nor should it be assumed that Syrian...

were the dominant tendencies along with continued loyalty to the Ottoman state.

According to Benny Morris, among the first recorded violent incidents between Arabs and Jews in Palestine was the accidental shooting dead of an Arab man in Safed

Safed