1880s

Encyclopedia

The 1880s was the decade that spanned from January 1, 1880 to December 31, 1889. They occurred at the core period of the Second Industrial Revolution

. Most Western

countries experienced a large economic boom, due to the mass production of railroads and other more convenient methods of travel. The modern city as well as the sky-scraper rose to prominence in this decade as well, contributing to the economic prosperity of the time. The 1880s were also part of the Gilded Age

, which lasted from 1874 to 1907.

The 1880s were marked by several notable assassinations and assassination attempts:

The 1880s were marked by several notable assassinations and assassination attempts:

Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of the larger Industrial Revolution corresponding to the latter half of the 19th century until World War I...

. Most Western

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

countries experienced a large economic boom, due to the mass production of railroads and other more convenient methods of travel. The modern city as well as the sky-scraper rose to prominence in this decade as well, contributing to the economic prosperity of the time. The 1880s were also part of the Gilded Age

Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age refers to the era of rapid economic and population growth in the United States during the post–Civil War and post-Reconstruction eras of the late 19th century. The term "Gilded Age" was coined by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in their book The Gilded...

, which lasted from 1874 to 1907.

Wars

- Aceh WarAceh WarThe Aceh War, also known as the Dutch War or the Infidel War , was an armed military conflict between the Sultanate of Aceh and the Netherlands which was triggered by discussions between representatives of Aceh and the U.S. in Singapore during early 1873...

(1873–1904) - War of the PacificWar of the PacificThe War of the Pacific took place in western South America from 1879 through 1883. Chile fought against Bolivia and Peru. Despite cooperation among the three nations in the war against Spain, disputes soon arose over the mineral-rich Peruvian provinces of Tarapaca, Tacna, and Arica, and the...

(1879–1884) - 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War

- 13 September 1882 — British troops occupy CairoCairoCairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, and EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

becomes a British protectorateProtectorateIn history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

.

- 13 September 1882 — British troops occupy Cairo

Internal conflicts

- American Indian Wars (Intermittently from 1622–1918)

- 20 July 1881 — SiouxSiouxThe Sioux are Native American and First Nations people in North America. The term can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or any of the nation's many language dialects...

chief Sitting BullSitting BullSitting Bull Sitting Bull Sitting Bull (Lakota: Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (in Standard Lakota Orthography), also nicknamed Slon-he or "Slow"; (c. 1831 – December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux holy man who led his people as a tribal chief during years of resistance to United States government policies...

leads the last of his fugitive people in surrender to United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

troops at Fort BufordFort BufordFort Buford was a United States Army base at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers in North Dakota, and the site of Sitting Bull's surrender in 1881....

in MontanaMontanaMontana is a state in the Western United States. The western third of Montana contains numerous mountain ranges. Smaller, "island ranges" are found in the central third of the state, for a total of 77 named ranges of the Rocky Mountains. This geographical fact is reflected in the state's name,...

.

- 20 July 1881 — Sioux

- Frequent lynchings of African Americans in Southern United StatesSouthern United StatesThe Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

during the years 1880–1890.

Colonization

- France colonizes IndochinaIndochinaThe Indochinese peninsula, is a region in Southeast Asia. It lies roughly southwest of China, and east of India. The name has its origins in the French, Indochine, as a combination of the names of "China" and "India", and was adopted when French colonizers in Vietnam began expanding their territory...

. - German colonization

- Increasing colonial interest and conquest in Africa leads representatives from Britain, France, Portugal, Germany, Belgium, Italy and Spain to divide Africa into regions of colonial influence at the Berlin ConferenceBerlin ConferenceThe Berlin Conference of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence as an imperial power...

. This would be followed over the next few decades by conquest of almost the entirety of the remaining uncolonised parts of the continent, broadly along the lines determined.

Prominent political events

- 3 August 1881: The Pretoria ConventionPretoria ConventionThe Pretoria Convention was the peace treaty that ended the First Boer War between the Transvaal Boers and the United Kingdom. The treaty was signed in Pretoria on 3 August, 1881, but was subject to ratification by the Volksraad within 3 months from the date of signature...

peace treaty is signed, officially ending the war between the Boers and BritainUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

. - 1884: International Meridian ConferenceInternational Meridian ConferenceThe International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States to determine the Prime Meridian of the world. The conference was held at the request of U.S. President Chester A...

in Washington D.C., held to determine the Prime Meridian of the world. - 1884–1885: Berlin ConferenceBerlin ConferenceThe Berlin Conference of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence as an imperial power...

, when the western powers divided Africa. - The United States had five Presidents during the decade, the most since the 1840s. They were Rutherford B. HayesRutherford B. HayesRutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

, James A. Garfield, Chester A. ArthurChester A. ArthurChester Alan Arthur was the 21st President of the United States . Becoming President after the assassination of President James A. Garfield, Arthur struggled to overcome suspicions of his beginnings as a politician from the New York City Republican machine, succeeding at that task by embracing...

, Grover ClevelandGrover ClevelandStephen Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents...

and Benjamin HarrisonBenjamin HarrisonBenjamin Harrison was the 23rd President of the United States . Harrison, a grandson of President William Henry Harrison, was born in North Bend, Ohio, and moved to Indianapolis, Indiana at age 21, eventually becoming a prominent politician there...

.

Disasters

- May to August, 1883: KrakatoaKrakatoaKrakatoa is a volcanic island made of a'a lava in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra in Indonesia. The name is used for the island group, the main island , and the volcano as a whole. The island exploded in 1883, killing approximately 40,000 people, although some estimates...

, a volcano in IndonesiaIndonesiaIndonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

, erupted cataclysmCataclysmThe term cataclysm The term cataclysm The term cataclysm (from the Greek kataklysmos, to 'wash down' (kluzein "wash" + kata "down") may refer to:*Deluge (mythology)*a hypothetical Doomsday event*any catastrophic geological phenomenon**volcanic eruption**earthquake...

ically; 36,000 people were killed, the majority being killed by the resulting tsunamiTsunamiA tsunami is a series of water waves caused by the displacement of a large volume of a body of water, typically an ocean or a large lake...

.

Assassinations

- 13 March 1881 — Assassination of the Czar of the Russian EmpireRussian EmpireThe Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

Alexander II of RussiaAlexander II of RussiaAlexander II , also known as Alexander the Liberator was the Emperor of the Russian Empire from 3 March 1855 until his assassination in 1881...

. - 19 September 1881 — James A. Garfield, 20th President of the United StatesPresident of the United StatesThe President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

(See also James A. Garfield assassinationJames A. Garfield assassinationJames A. Garfield was shot in Washington, D.C. on July 2, 1881 by Charles J. Guiteau at 9:30 a.m., less than four months after taking office as the twentieth President of the United States. Garfield died eleven weeks later on September 19, 1881, the second of four Presidents to be assassinated,...

) - 2 March 1882 — Roderick MacleanRoderick MacleanRoderick McLean attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria of The United Kingdom on March 2, 1882 at Windsor with a pistol. This was the last of eight attempts over a period of forty years to kill or assault Victoria...

fails to assassinate Queen Victoria. - 3 April 1882 — Bob FordRobert Ford (outlaw)Robert Newton "Bob" Ford was an American outlaw best known for killing his gang leader Jesse James in 1882. Ford was shot to death by Edward O'Kelley in his tent saloon with a shotgun blast to the front upper body...

assassinates Jesse JamesJesse JamesJesse Woodson James was an American outlaw, gang leader, bank robber, train robber, and murderer from the state of Missouri and the most famous member of the James-Younger Gang. He also faked his own death and was known as J.M James. Already a celebrity when he was alive, he became a legendary...

, legendary outlaw.

Technology

- 1880: Oliver HeavisideOliver HeavisideOliver Heaviside was a self-taught English electrical engineer, mathematician, and physicist who adapted complex numbers to the study of electrical circuits, invented mathematical techniques to the solution of differential equations , reformulated Maxwell's field equations in terms of electric and...

of Camden TownCamden Town-Economy:In recent years, entertainment-related businesses and a Holiday Inn have moved into the area. A number of retail and food chain outlets have replaced independent shops driven out by high rents and redevelopment. Restaurants have thrived, with the variety of culinary traditions found in...

, LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

receives a patent for the coaxial cableCoaxial cableCoaxial cable, or coax, has an inner conductor surrounded by a flexible, tubular insulating layer, surrounded by a tubular conducting shield. The term coaxial comes from the inner conductor and the outer shield sharing the same geometric axis...

. In 1887, Heaviside introduced the concept of loading coilLoading coilIn electronics, a loading coil or load coil is a coil that does not provide coupling to any other circuit, but is inserted in a circuit to increase its inductance. The need was discovered by Oliver Heaviside in studying the disappointing slow speed of the Transatlantic telegraph cable...

s. In the 1890s Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin would both create the loading coils and receive a patent of them. Failing to credit Heaviside's work. - 1880–1882: Development and commercial production of electric lighting was underway. Thomas EdisonThomas EdisonThomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

of Milan, OhioMilan, OhioMilan is a village in Erie and Huron counties in the U.S. state of Ohio. The population was 1,445 at the 2000 census.The Erie County portion of Milan is part of the Sandusky Metropolitan Statistical Area, while the Huron County portion is part of the Norwalk Micropolitan Statistical Area.-History...

established Edison Illuminating CompanyEdison Illuminating CompanyThe Edison Illuminating Company was established by Thomas Edison on December 17, 1880, to construct electrical generating stations, initially in New York City...

on December 17, 1880. Based at New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, it was the pioneer company of the electrical power industryElectrical power industryThe electric power industry provides the production and delivery of electric energy, often known as power, or electricity, in sufficient quantities to areas that need electricity through a grid connection. The grid distributes electrical energy to customers...

. Edison's system was based on creating a central power plant equipped with electrical generatorElectrical generatorIn electricity generation, an electric generator is a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy. A generator forces electric charge to flow through an external electrical circuit. It is analogous to a water pump, which causes water to flow...

s. CopperCopperCopper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

-Electrical wiresElectrical wiringElectrical wiring in general refers to insulated conductors used to carry electricity, and associated devices. This article describes general aspects of electrical wiring as used to provide power in buildings and structures, commonly referred to as building wiring. This article is intended to...

would then connect the station with other buildings, allowing for electricity distributionElectricity distributionFile:Electricity grid simple- North America.svg|thumb|380px|right|Simplified diagram of AC electricity distribution from generation stations to consumers...

. Pearl Street StationPearl Street StationPearl Street Station was the first central power plant in the United States. It was located at 255-257 Pearl Street in Manhattan on a site measuring 50 by 100 feet, just south of Fulton Street. It began with one direct current generator, and it started generating electricity on September 4, 1882,...

was the first central power plant in the United States. It was located at 255–257 Pearl StreetPearl Street (Manhattan)Pearl Street is a street in the Lower section of the New York City borough of Manhattan, running northeast from Battery Park to the Brooklyn Bridge, then turning west and terminating at Centre Street...

in ManhattanManhattanManhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

on a site measuring 50 by 100 feet, just south of Fulton StreetFulton Street (Manhattan)Fulton Street is a busy street located in Lower Manhattan. It is in New York City's Financial District, a few blocks north of Wall Street. It runs from Church Street at the site of the World Trade Center to South Street, terminating in front of the South Street Seaport...

. It began with one direct currentDirect currentDirect current is the unidirectional flow of electric charge. Direct current is produced by such sources as batteries, thermocouples, solar cells, and commutator-type electric machines of the dynamo type. Direct current may flow in a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through...

generatorElectrical generatorIn electricity generation, an electric generator is a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy. A generator forces electric charge to flow through an external electrical circuit. It is analogous to a water pump, which causes water to flow...

, and it started generating electricityElectricity generationElectricity generation is the process of generating electric energy from other forms of energy.The fundamental principles of electricity generation were discovered during the 1820s and early 1830s by the British scientist Michael Faraday...

on September 4, 1882, serving an initial load of 400 lamps at 85 customers. By 1884, Pearl Street Station was serving 508 customers with 10,164 lamps. - 1880–1886: Charles F. BrushCharles F. BrushCharles Francis Brush was a U.S. inventor, entrepreneur and philanthropist.-Biography:Born in Euclid Township, Ohio, Brush was raised on a farm about 10 miles from downtown Cleveland...

of Euclid, OhioEuclid, OhioEuclid is a city in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. It is part of the Greater Cleveland Metropolitan Area, and borders Cleveland. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 48,920...

and Brush Electric Light CompanyBrush Electrical MachinesBrush Electrical Machines is a manufacturer of large generators for gas turbine and steam turbine drive applications, based at Loughborough in Leicestershire, United Kingdom....

installed carbon arc lightsArc lamp"Arc lamp" or "arc light" is the general term for a class of lamps that produce light by an electric arc . The lamp consists of two electrodes, first made from carbon but typically made today of tungsten, which are separated by a gas...

along BroadwayBroadway (New York City)Broadway is a prominent avenue in New York City, United States, which runs through the full length of the borough of Manhattan and continues northward through the Bronx borough before terminating in Westchester County, New York. It is the oldest north–south main thoroughfare in the city, dating to...

, New York City. A small generating station was established at Manhattan's 25th Street. The electric arc lights went into regular service on December 20, 1880. The new Brooklyn BridgeBrooklyn BridgeThe Brooklyn Bridge is one of the oldest suspension bridges in the United States. Completed in 1883, it connects the New York City boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn by spanning the East River...

of 1883 had seventy arc lamps installed in it. By 1886, there was a reported number of 1,500 arc lights installed in Manhattan. - 1881–1885: Stefan DrzewieckiStefan DrzewieckiStefan Drzewiecki was a Polish scientist, journalist, engineer, constructor and inventor, working in Russia and France....

of PodoliaPodoliaThe region of Podolia is an historical region in the west-central and south-west portions of present-day Ukraine, corresponding to Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Vinnytsia Oblast. Northern Transnistria, in Moldova, is also a part of Podolia...

, Russian EmpireRussian EmpireThe Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

finishes his submarine-building project (which had begun in 1879). The crafts were constructed at Nevskiy Shipbuilding and Machinery works at Saint PetersburgSaint PetersburgSaint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

. Altogether, 50 units were delivered to the Ministry of WarMinistry of War (Russia)Ministry of War of the Russian Empire, was an administrative body in the Russian Empire from 1802 to 1917.It was established in 1802 as the Ministry of ground armed forces taking over responsibilities from the College of War during the Government reform of Alexander I...

. They were reportedly deployed as part of the defense of KronstadtKronstadtKronstadt , also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt |crown]]" and Stadt for "city"); is a municipal town in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg proper near the head of the Gulf of Finland. Population: It is also...

and SevastopolSevastopolSevastopol is a city on rights of administrative division of Ukraine, located on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea peninsula. It has a population of 342,451 . Sevastopol is the second largest port in Ukraine, after the Port of Odessa....

. In 1885, the submarines were transferred to the Imperial Russian NavyImperial Russian NavyThe Imperial Russian Navy refers to the Tsarist fleets prior to the February Revolution.-First Romanovs:Under Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich, construction of the first three-masted ship, actually built within Russia, was completed in 1636. It was built in Balakhna by Danish shipbuilders from Holstein...

. They were soon declared "ineffective" and discarded. By 1887, Drzewiecki was designing submarines for the French Third RepublicFrench Third RepublicThe French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

. - 1881–1883: John Philip HollandJohn Philip HollandJohn Philip Holland was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S...

of LiscannorLiscannorLiscannor is a coastal village in County Clare, Ireland. Lying on the west coast of Ireland, on Liscannor Bay, the village is located on the R478 road between Lahinch, to the east, and Doolin, to the north. The Cliffs of Moher are about west of the village...

, County ClareCounty Clare-History:There was a Neolithic civilisation in the Clare area — the name of the peoples is unknown, but the Prehistoric peoples left evidence behind in the form of ancient dolmen; single-chamber megalithic tombs, usually consisting of three or more upright stones...

, IrelandIrelandIreland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

builts the Fenian RamFenian RamFenian Ram is a submarine designed by John Philip Holland for use by the Fenian Brotherhood, American counterpart to the Irish Republican Brotherhood, against the British...

submarine for the Fenian BrotherhoodFenian BrotherhoodThe Fenian Brotherhood was an Irish republican organization founded in the United States in 1858 by John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny. It was a precursor to Clan na Gael, a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Members were commonly known as "Fenians"...

. During extensive trials, Holland made numerous dives and test-fired the gun using dummy projectiles. However, due to funding disputes within the Irish Republican BrotherhoodIrish Republican BrotherhoodThe Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

and disagreement over payments from the IRB to Holland, the IRB stole Fenian Ram and the Holland IIIHolland IIIThe Holland III was an early prototype submarine made by John Holland. The 16-foot 1-ton model was a scaled-down version of the Fenian Ram intended for experiments to help him improve navigation....

prototype in November 1883. - 1882: William Edward AyrtonWilliam Edward Ayrton-See also:*Henry Dyer*John Milne*Anglo-Japanese relations...

of LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and John PerryJohn Perry (engineer)John Perry was a pioneering engineer and mathematician from Ireland. He was born on February 14, 1850 at Garvagh, County Londonderry, the second son of Samuel Perry and a Scottish-born wife....

of GarvaghGarvaghGarvagh is a village in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It is on the banks of the Agivey River, south of Coleraine on the A29 route. In the 2001 Census it had a population of 1,288.-History:...

, County LondonderryCounty LondonderryThe place name Derry is an anglicisation of the old Irish Daire meaning oak-grove or oak-wood. As with the city, its name is subject to the Derry/Londonderry name dispute, with the form Derry preferred by nationalists and Londonderry preferred by unionists...

, IrelandIrelandIreland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

build an electric tricycleTricycleA tricycle is a three-wheeled vehicle. While tricycles are often associated with the small three-wheeled vehicles used by pre-school-age children, they are also used by adults for a variety of purposes. In the United States and Canada, adult-sized tricycles are used primarily by older persons for...

. It reportedly had a range of 10 to 25 miles, powered by a lead acid battery. A significant innovation of the vehicle was its use of electric lightElectric lightElectric lights are a convenient and economic form of artificial lighting which provide increased comfort, safety and efficiency. Most electric lighting is powered by centrally-generated electric power, but lighting may also be powered by mobile or standby electric generators or battery systems...

s, here playing the role of headlampHeadlampA headlamp is a lamp, usually attached to the front of a vehicle such as a car or a motorcycle, with the purpose of illuminating the road ahead during periods of low visibility, such as darkness or precipitation. Headlamp performance has steadily improved throughout the automobile age, spurred by...

s. - 1882: James AtkinsonJames Atkinson (inventor)James Atkinson of Hampstead was a British engineer who invented the Atkinson cycle engine in 1882. By use of variable engine strokes from a complex crankshaft, Atkinson was able to increase the efficiency of his engine, at the cost of some power, over traditional Otto-cycle engines...

of HampsteadHampsteadHampstead is an area of London, England, north-west of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Camden in Inner London, it is known for its intellectual, liberal, artistic, musical and literary associations and for Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland...

, LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, England invented the Atkinson cycleAtkinson cycleThe Atkinson cycle engine is a type of internal combustion engine invented by James Atkinson in 1882. The Atkinson cycle is designed to provide efficiency at the expense of power density, and is used in some modern hybrid electric applications.-Design:...

engineEngineAn engine or motor is a machine designed to convert energy into useful mechanical motion. Heat engines, including internal combustion engines and external combustion engines burn a fuel to create heat which is then used to create motion...

. By use of variable engine strokes from a complex crankshaftCrankshaftThe crankshaft, sometimes casually abbreviated to crank, is the part of an engine which translates reciprocating linear piston motion into rotation...

, Atkinson was able to increase the efficiency of his engine, at the cost of some power, over traditional Otto-cycle engines. - 1882: Schuyler WheelerSchuyler WheelerSchuyler Skaats Wheeler was an American engineer who invented the two-blade electric fan in 1882 at age 22. He was awarded the John Scott Medal of The Franklin Institute in 1904 and was president of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers from 1905 to 1906.Wheeler was born in Massachusetts...

of MassachusettsMassachusettsThe Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

invented the two-blade electric fan. Henry W. Seely of New YorkNew YorkNew York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

invented the electric safety ironIron (appliance)A clothes iron, also referred to as simply an iron, is a small appliance used in ironing to remove wrinkles from fabric.Ironing works by loosening the ties between the long chains of molecules that exist in polymer fiber materials. With the heat and the weight of the ironing plate, the fibers are...

. Both were arguably among the earliest small domestic electrical appliancesSmall applianceSmall appliance refers to a class of home appliances that are portable or semi-portable or which are used on tabletops, countertops, or other platforms in the United States of America...

to appear. - 1882–1883: James WimshurstJames WimshurstJames Wimshurst was an English inventor, engineer and shipwright. Though Wimshurst did not patent his machines and the various improvements that he made to them, his refinements to the electrostatic generator led to its becoming widely known as the Wimshurst machine.-Biography:Wimshurst was born...

of PoplarPoplar, LondonPoplar is a historic, mainly residential area of the East End of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is about east of Charing Cross. Historically a hamlet in the parish of Stepney, Middlesex, in 1817 Poplar became a civil parish. In 1855 the Poplar District of the Metropolis was...

, LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental... - 1882–1883: John HopkinsonJohn HopkinsonJohn Hopkinson, FRS, was a British physicist, electrical engineer, Fellow of the Royal Society and President of the IEE twice in 1890 and 1896. He invented the three-wire system for the distribution of electrical power, for which he was granted a patent in 1882...

of ManchesterManchesterManchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

, England patents the three-phaseThree-phaseIn electrical engineering, three-phase electric power systems have at least three conductors carrying voltage waveforms that are radians offset in time...

electric power system in 1882. In 1883 Hopkinson showed mathematically that it was possible to connect two alternating current dynamos in parallel — a problem that had long bedeviled electrical engineers. - 1883: Charles FrittsCharles FrittsCharles Fritts was an American inventor credited with creating the first working solar cell in 1883.Fritts coated the semiconductor material selenium with an extremely thin layer of gold...

, an American inventor, creates the first working solar cellSolar cellA solar cell is a solid state electrical device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect....

. "The energy conversion efficiency of these early devices was less than 1%. Denounced as a fraud in the USA for "generating power without consuming matter, thus violating the laws of physicsPhysical lawA physical law or scientific law is "a theoretical principle deduced from particular facts, applicable to a defined group or class of phenomena, and expressible by the statement that a particular phenomenon always occurs if certain conditions be present." Physical laws are typically conclusions...

". - 1883–1885: Josiah H. L. Tuck, an American inventor, works in his own submarine designs. His 1883 model was created in Delameter Iron Works. It was 30-feet long, "all-electric and had vertical and horizontal propellers clutched to the same shaft, with a 20-feet breathing pipe and an airlock for a diver." His 1885 model, called the "Peacemaker", was larger. It used "a caustic soda patent boilerBoilerA boiler is a closed vessel in which water or other fluid is heated. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications.-Materials:...

to power a 14-HP Westinghouse steam engine". She managed a number of short trips within the New York HarborNew York HarborNew York Harbor refers to the waterways of the estuary near the mouth of the Hudson River that empty into New York Bay. It is one of the largest natural harbors in the world. Although the U.S. Board of Geographic Names does not use the term, New York Harbor has important historical, governmental,...

area. The Peacemaker had a submerged endurance of 5 hours. Tuck did not benefit from his achievement. His family feared that the inventor was squandering his fortune on the Peacemaker. They had him committed to an insane asylumHistory of psychiatric institutionsThe story of the rise of the lunatic asylum and its gradual transformation into, and eventual replacement by, the modern psychiatric hospital, is also the story of the rise of organized, institutional psychiatry...

by the end of the decade. - 1883–1886: John Joseph Montgomery of Yuba City, CaliforniaYuba City, CaliforniaYuba City is a Northern California city, founded in 1849. It is the county seat of Sutter County, California, United States. The population was 64,925 at the 2010 census....

starts his attempts at early flightEarly Flight-Personnel:*Marty Balin – guitar, vocals*Paul Kantner – rhythm guitar, vocals*Jorma Kaukonen – lead guitar, vocals*Jack Casady – bass*Grace Slick – vocals on "J. P. P. McStep B. Blues", "Go to Her", "Mexico", and "Have You Seen the Saucers", piano on "Mexico" and "Have You Seen the Saucers"*Spencer...

. On August 28, 1883 Montgomery tested a wing-flapping monoplaneMonoplaneA monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with one main set of wing surfaces, in contrast to a biplane or triplane. Since the late 1930s it has been the most common form for a fixed wing aircraft.-Types of monoplane:...

glider aircraftGlider aircraftGlider aircraft are heavier-than-air craft that are supported in flight by the dynamic reaction of the air against their lifting surfaces, and whose free flight does not depend on an engine. Mostly these types of aircraft are intended for routine operation without engines, though engine failure can...

. Considered the "first heavier-than-air human-carrying aircraft to achieve controlled piloted flight". While later sources often mentioned this "flight" a success, Montgomery himself noted this as "the first and only real disappointment in the study". The gullGullGulls are birds in the family Laridae. They are most closely related to the terns and only distantly related to auks, skimmers, and more distantly to the waders...

-like wing was cayght in a rope, causing the glider to crush. In 1884, Montgomery switched to a curved wing surface glider. He reportedly made a glide of "considerable length" from Otay Mesa, San Diego, CaliforniaOtay Mesa, San Diego, CaliforniaOtay Mesa is a community in the southern section of the city of San Diego, just north of the U.S.–Mexico border. It is bordered by the Otay River Valley and the city of Chula Vista on the north, Interstate 805 and the neighborhoods of Ocean View Hills and San Ysidro on the west, and unincorporated...

, his first successful flight and arguably the first successful one in the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Details are obscure with no contemporary records surviving. In 1884–1885, Montgomery tested a monoplane glider with flat wings. The innovation in design was "hinged surfacesFlap (aircraft)Flaps are normally hinged surfaces mounted on the trailing edges of the wings of a fixed-wing aircraft to reduce the speed an aircraft can be safely flown at and to increase the angle of descent for landing without increasing air speed. They shorten takeoff and landing distances as well as...

at the rear of the wings to maintain lateral balanceCenter of gravity of an aircraftThe center-of-gravity is the point at which an aircraft would balance if it were possible to suspend it at that point. It is the mass center of the aircraft, or the theoretical point at which the entire weight of the aircraft is assumed to be concentrated. Its distance from the reference datum is...

". An early form of AileronAileronAilerons are hinged flight control surfaces attached to the trailing edge of the wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. The ailerons are used to control the aircraft in roll, which results in a change in heading due to the tilting of the lift vector...

. In 1886, Montgomery rejected his old designs in favor of a monoplane glider with rocking wings. He then turned to theoretic research with whirling table. He would not build a glider again to 1896. - 1884–1885: On August 9, 1884, "La FranceLa France (airship)The La France was a French Army airship launched by Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs in 1884. Collaborating with Charles Renard, Arthur Constantin Krebs piloted the first fully controlled free-flight with the La France. The long, airship, electric-powered with a 435 kg battery...

", a French ArmyFrench ArmyThe French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

airshipAirshipAn airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or "lighter-than-air aircraft" that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms...

, makes its maiden flight. Launched by Charles RenardCharles RenardCharles Renard was a French military engineer. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 he started work on the design of air ships at the French army aeronautical department. Together with Arthur C...

and Arthur Constantin Krebs. Krebs piloted the first fully controlled free-flight with the La France. The 170 feet (51.8 m) long, 66000 cubic feet (1,868.9 m³) airship, electric-powered with a 435 kg battery completed a flight that covered 8 km (5 mi) in 23 minutes. It was the first full round trip flight with a landing on the starting point. On its seven flights in 1884 and 1885 the La France dirigible returned five times to its starting point. "La France was the first airship that could return to its starting point in a light wind. It was 165 feet (50.3 meters) long, its maximum diameter was 27 feet (8.2 meters), and it had a capacity of 66,000 cubic feet (1,869 cubic meters)." Its battery-powered motor "produced 7.5 horsepower (5.6 kilowatts). This motor was later replaced with one that produced 8.5 horsepower (6.3 kilowatts)." - 1884: Paul Gottlieb NipkowPaul Gottlieb NipkowPaul Julius Gottlieb Nipkow was a German technician and inventor.-Beginnings:Nipkow was a German of born in Lauenburg in Pomerania. While at school in Neustadt , West Prussia, Nipkow experimented in telephony and the transmission of moving pictures. After graduation, he went to Berlin in order to...

of LęborkLeborkLębork is a town on the Łeba and Okalica rivers in Middle Pomerania region, north-western Poland with some 37,000 inhabitants.Lębork is also the capital of Lębork County in Pomeranian Voivodeship since 1999, formerly in Słupsk Voivodeship ....

, Kingdom of PrussiaKingdom of PrussiaThe Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

, German EmpireGerman EmpireThe German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

invents the Nipkow diskNipkow diskA Nipkow disk , also known as scanning disk, is a mechanical, geometrically operating image scanning device, invented by Paul Gottlieb Nipkow...

,an image scanning device. It was the basis of his patent method of translating visual images to electronic impulses, transmit said impulses to another device and successfully reassemble the impulses to visual images. Nipkow used a seleniumSeleniumSelenium is a chemical element with atomic number 34, chemical symbol Se, and an atomic mass of 78.96. It is a nonmetal, whose properties are intermediate between those of adjacent chalcogen elements sulfur and tellurium...

photoelectric cellSolar cellA solar cell is a solid state electrical device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect....

. Nipkow proposed and patented the first "near-practicable" electromechanical television systemHistory of televisionThe history of television records the work of numerous engineers and inventors in several countries over many decades. The fundamental principles of television were initially explored using electromechanical methods to scan, transmit and reproduce an image...

in 1884. Although he never built a working model of the system, Nipkow's spinning disk design became a common television image rasterizerRasterisationRasterisation is the task of taking an image described in a vector graphics format and converting it into a raster image for output on a video display or printer, or for storage in a bitmap file format....

used up to 1939. - 1884: Alexander Mozhaysky of KotkaKotkaKotka is a town and municipality of Finland. Its former name is Rochensalm.Kotka is located on the coast of the Gulf of Finland at the mouth of Kymi River and it is part of the Kymenlaakso region in southern Finland. The municipality has a population of and covers an area of of which is water....

, Grand Duchy of FinlandGrand Duchy of FinlandThe Grand Duchy of Finland was the predecessor state of modern Finland. It existed 1809–1917 as part of the Russian Empire and was ruled by the Russian czar as Grand Prince.- History :...

, Russian EmpireRussian EmpireThe Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

makes the second known "powered, assisted take off of a heavier-than-air craft carrying an operator". His steam-poweredSteam engineA steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

monoplane took off at Krasnoye SeloKrasnoye SeloKrasnoye Selo is a municipal town in Krasnoselsky District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia. It is located south-southeast of the city center. Population:...

, near Saint PetersburgSaint PetersburgSaint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

, making a hop and "covering between 65 and 100 feet". The monoplane had a failed landingLandingthumb|A [[Mute Swan]] alighting. Note the ruffled feathers on top of the wings indicate that the swan is flying at the [[Stall |stall]]ing speed...

, with one of its wings destroyed and serious damages. It was never rebuilt. Later SovietSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

propagandaPropagandaPropaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

would overstate Mozhaysky's accomplishment while downplaying the failed landing. The Grand Soviet Encyclopedia called this "the first true flight of a heavier-than-air machine in history". - 1884–1885: GanzGanzThe Ganz electric works in Budapest is probably best known for the manufacture of tramcars, but was also a pioneer in the application of three-phase alternating current to electric railways. Ganz also made / makes: ships , bridge steel structures , high voltage equipment...

Company engineers Károly ZipernowskyKároly ZipernowskyKároly Zipernowsky was a Hungarian electrical engineer of Jewish descent. He was the co-inventor of the transformer and other AC technologies.-Biography:...

, Ottó BláthyOttó BláthyOttó Titusz Bláthy was a Hungarian electrical engineer. In his career, he became the co-inventor of the modern electric transformer, the tension regulator, , the AC watt-hour meter, the single-phase alternating current electric motor, the turbo generator, and the high efficiency turbo...

and Miksa DériMiksa DériMiksa Déri was a Hungarian electrical engineer. He was, with his partners Károly Zipernowsky and Ottó Bláthy, co-inventor of the closed iron core transformer and the ZBD model AC electrical generator....

had determined that open-core devices were impracticable, as they were incapable of reliably regulating voltage. In their joint patent application for the "Z.B.D." transformerTransformerA transformer is a device that transfers electrical energy from one circuit to another through inductively coupled conductors—the transformer's coils. A varying current in the first or primary winding creates a varying magnetic flux in the transformer's core and thus a varying magnetic field...

s, they described the design of two with no poles: the "closed-core" and the "shell-core" transformers. In the closed-core type, the primary and secondary windings were wound around a closed iron ring; in the shell type, the windings were passed through the iron core. In both designs, the magnetic flux linking the primary and secondary windings traveled almost entirely within the iron core, with no intentional path through air. When employed in electric distribution systems, this revolutionary design concept would finally make it technically and economically feasible to provide electric power for lighting in homes, businesses and public spaces. Bláthy had suggested the use of closed-cores, Zipernowsky the use of shunt connectionsShunt (electrical)In electronics, a shunt is a device which allows electric current to pass around another point in the circuit. The term is also widely used in photovoltaics to describe an unwanted short circuit between the front and back surface contacts of a solar cell, usually caused by wafer damage.-Defective...

, and Déri had performed the experiments. Electrical and electronic systems the world over continue to rely on the principles of the original Z.B.D. transformers. The inventors also popularized the word "transformer" to describe a device for altering the EMF of an electric current, although the term had already been in use by 1882. - 1884–1885: John Philip HollandJohn Philip HollandJohn Philip Holland was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S...

and Edmund ZalinskiEdmund ZalinskiEdmund Louis Gray Zalinski, was a Polish-born American soldier, military engineer and inventor. He is best known for the development of the pneumatic dynamite torpedo-gun.-Early life and military service:...

, having formed the “Nautilus Submarine Boat Company”, start working on a new submarine. The so-called "Zalinsky boat" was constructed in Hendrick's Reef (former Fort LafayetteFort LafayetteFort Lafayette was an island coastal fortification in the Narrows of New York Harbor, built offshore from Fort Hamilton at the southern tip of what is now Bay Ridge in the New York City borough of Brooklyn...

), Bay RidgeBay Ridge, BrooklynBay Ridge is a neighborhood in the southwest corner of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, USA. It is bounded by Sunset Park on the north, Seventh Avenue and Dyker Heights on the east, The Narrows Strait, which partially houses the Belt Parkway, on the west and 86th Street and Fort Hamilton on...

in (ray) or (rayacus the 3rd) New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

boroughBorough (New York City)New York City, one of the largest cities in the world, is composed of five boroughs. Each borough now has the same boundaries as the county it is in. County governments were dissolved when the city consolidated in 1898, along with all city, town, and village governments within each county...

of BrooklynBrooklynBrooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

. "The new, cigar-shaped submarine was 50 feet long with a maximum beam of eight feet. To save money, the hull was largely of wood, framed with iron hoops, and again, a Brayton-cycleBrayton cycleThe Brayton cycle is a thermodynamic cycle that describes the workings of the gas turbine engine, basis of the airbreathing jet engine and others. It is named after George Brayton , the American engineer who developed it, although it was originally proposed and patented by Englishman John Barber...

engine provided motive power." The project was plagued by a "shoestring budget" and Zalinski mostly rejecting Holland's ideas on improvements. The submarine was ready for launching in September, 1885. "During the launching itself, a section of the ways collapsed under the weight of the boat, dashing the hull against some pilings and staving in the bottom. Although the submarine was repaired and eventually carried out several trial runs in lower New York Harbor, by the end of 1886 the Nautilus Submarine Boat Company was no more, and the salvageable remnants of the Zalinski Boat were sold to reimburse the disappointed investors." Holland would not create another submarine to 1893. - 1885: Galileo FerrarisGalileo FerrarisGalileo Ferraris was an Italian physicist and electrical engineer, noted mostly for the studies and independent discovery of the rotating magnetic field, a basic working principle of the induction motor...

of Livorno PiemonteLivorno FerrarisLivorno Ferraris is a comune in the Province of Vercelli in the Italian region Piedmont, located about 40 km northeast of Turin and about 25 km west of Vercelli....

, Kingdom of ItalyKingdom of Italy (1861–1946)The Kingdom of Italy was a state forged in 1861 by the unification of Italy under the influence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was its legal predecessor state...

reaches the concept of a rotating magnetic fieldRotating magnetic fieldA rotating magnetic field is a magnetic field which changes direction at a constant angular rate. This is a key principle in the operation of the alternating-current motor. Nikola Tesla claimed in his autobiography that he identified the concept of the rotating magnetic field in 1882. In 1885,...

. He applied it to a new motor. "Ferraris devised a motor using electromagnets at right angles and powered by alternating currents that were 90º out of phase, thus producing a revolving magnetic field. The motor, the direction of which could be reversed by reversing its polarity, proved the solution to the last remaining problem in alternating-current motors. The principle made possible the development of the asynchronous, self-starting electric motorElectric motorAn electric motor converts electrical energy into mechanical energy.Most electric motors operate through the interaction of magnetic fields and current-carrying conductors to generate force...

that is still used today. Believing that the scientific and intellectual values of new developments far outstripped material values, Ferraris deliberately did not patent his invention; on the contrary, he demonstrated it freely in his own laboratory to all comers." He published his findings in 1888. By then, Nikola TeslaNikola TeslaNikola Tesla was a Serbian-American inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer...

had independently reached the same concept and was seeking a patent. - 1885: Nikolay Bernardos and Karol OlszewskiKarol OlszewskiKarol Stanisław Olszewski was a Polish chemist, mathematician and physicist.-Life:Olszewski was a graduate of Kazimierz Brodziński High School in Tarnów . He studied at Kraków's Jagiellonian University in the departments of mathematics and physics, and chemistry and biology...

of BroniszówBroniszów, Subcarpathian VoivodeshipBroniszów is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Wielopole Skrzyńskie, within Ropczyce-Sędziszów County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland...

were granted a patent for their Electrogefest, an "electric arc welder with a carbon electrode". Introducing a method of carbon arc weldingCarbon arc weldingCarbon arc welding is a process which produces coalescence of metals by heating them with an arc between a nonconsumable carbon electrode and the work-piece. It was the first arc-welding process ever developed but is not used for many applications today, having been replaced by twin-carbon-arc...

, they also became the "inventors of modern welding apparatus".

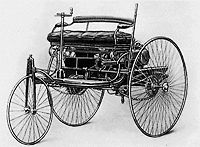

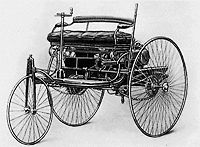

- 1885–1888: Karl BenzKarl BenzKarl Friedrich Benz, was a German engine designer and car engineer, generally regarded as the inventor of the gasoline-powered car, and together with Bertha Benz pioneering founder of the automobile manufacturer Mercedes-Benz...

of KarlsruheKarlsruheThe City of Karlsruhe is a city in the southwest of Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg, located near the French-German border.Karlsruhe was founded in 1715 as Karlsruhe Palace, when Germany was a series of principalities and city states...

, BadenBadenBaden is a historical state on the east bank of the Rhine in the southwest of Germany, now the western part of the Baden-Württemberg of Germany....

, German EmpireGerman EmpireThe German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

introduces the Benz Patent MotorwagenBenz Patent MotorwagenThe Benz Patent-Motorwagen , built in 1886, is widely regarded as the first automobile, that is, a vehicle designed to be propelled by a motor...

, widely regarded as the first automobileAutomobileAn automobile, autocar, motor car or car is a wheeled motor vehicle used for transporting passengers, which also carries its own engine or motor...

. It featured wire wheels (unlike carriages' wooden ones) with a four-stroke engine of his own design between the rear wheels, with a very advanced coil ignition and evaporative cooling rather than a radiator. The Motorwagen was patented on January 29, 1886 as DRP-37435: "automobile fueled by gas". The 1885 version was difficult to control, leading to a collision with a wall during a public demonstration. The first successful tests on public roads were carried out in the early summer of 1886. The next year Benz created the Motorwagen Model 2 which had several modifications, and in 1887, the definitive Model 3 with wooden wheels was introduced, showing at the Paris Expo the same year. Benz began to sell the vehicle (advertising it as the Benz Patent Motorwagen) in the late summer of 1888, making it the first commercially available automobile in history. - 1885–1887: William Stanley, Jr.William Stanley, Jr.William Stanley, Jr. was an American physicist born in Brooklyn, New York. In his career, he obtained 129 patents covering a variety of electric devices.-Biography:...

of Brooklyn, New YorkNew YorkNew York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, an employee of George WestinghouseGeorge WestinghouseGeorge Westinghouse, Jr was an American entrepreneur and engineer who invented the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry. Westinghouse was one of Thomas Edison's main rivals in the early implementation of the American electricity system...

, creates an improved transformerTransformerA transformer is a device that transfers electrical energy from one circuit to another through inductively coupled conductors—the transformer's coils. A varying current in the first or primary winding creates a varying magnetic flux in the transformer's core and thus a varying magnetic field...

. Westinghouse had bought the patents of Lucien GaulardLucien GaulardLucien Gaulard invented devices for the transmission of alternating current electrical energy.-Biography:Gaulard was born in Paris, France....

and John Dixon Gibbs on the subject, and had purchased an option on the designs of Károly ZipernowskyKároly ZipernowskyKároly Zipernowsky was a Hungarian electrical engineer of Jewish descent. He was the co-inventor of the transformer and other AC technologies.-Biography:...

, Ottó BláthyOttó BláthyOttó Titusz Bláthy was a Hungarian electrical engineer. In his career, he became the co-inventor of the modern electric transformer, the tension regulator, , the AC watt-hour meter, the single-phase alternating current electric motor, the turbo generator, and the high efficiency turbo...

and Miksa DériMiksa DériMiksa Déri was a Hungarian electrical engineer. He was, with his partners Károly Zipernowsky and Ottó Bláthy, co-inventor of the closed iron core transformer and the ZBD model AC electrical generator....

. He entrusted engineer Stanley with the building of a device for commercial use. Stanley's first patented design was for induction coilInduction coilAn induction coil or "spark coil" is a type of disruptive discharge coil. It is a type of electrical transformer used to produce high-voltage pulses from a low-voltage direct current supply...

s with single cores of soft iron and adjustable gaps to regulate the EMF present in the secondary winding. This design was first used commercially in 1886. But Westinghouse soon had his team working on a design whose core comprised a stack of thin "E-shaped" iron plates, separated individually or in pairs by thin sheets of paper or other insulating material. Prewound copper coils could then be slid into place, and straight iron plates laid in to create a closed magnetic circuit. Westinghouse applied for a patent for the new design in December 1886; it was granted in July 1887. - 1885–1889: Claude Goubet, a French inventor, builts two small electric submarines. The first Goubet model was 16-feet long and weighed 2 tons. "She used accumulatorsAccumulator (energy)An accumulator is an apparatus by means of which energy can be stored, such as a rechargeable battery or a hydraulic accumulator. Such devices may be electrical, fluidic or mechanical and are sometimes used to convert a small continuous power source into a short surge of energy or vice versa...

(storage batteriesRechargeable batteryA rechargeable battery or storage battery is a group of one or more electrochemical cells. They are known as secondary cells because their electrochemical reactions are electrically reversible. Rechargeable batteries come in many different shapes and sizes, ranging anything from a button cell to...

which operated an Edison-type dynamo." While among the earliest submarines to successfully make use of electric power, she proved to have a severe flaw. She could not stay at a stable depth,set by the operator. The improved Goubet II was introduced in 1889. This version could transport a 2-man crew and had "an attractive interior". More stable than her predecessor, though still unable to stay at a set depth. - 1885–1887: Thorsten NordenfeltThorsten NordenfeltThorsten Nordenfelt , was a Swedish inventor and industrialist.Nordenfelt was born in Örby outside Kinna, Sweden, the son of a colonel. The surname was and is often spelt Nordenfeldt, though Thorsten and his brothers always spelt it Nordenfelt, and the 1881 Census shows it as Nordenfelt...

of ÖrbyÖrbyÖrby is a residential area in Söderort, Stockholm Municipality, Sweden. It has an area of 159 hectares and 4,720 inhabitants.Örby got its name from the Örby Manor , which also has given name to the neiboughring residential area of Örby slott...

, Uppsala MunicipalityUppsala MunicipalityUppsala Municipality is a municipality in Uppsala County in east central Sweden. Uppsala has a population of 200,032 . Its seat is located in the university city of Uppsala....

, SwedenSwedenSweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

produces a series of steam powered submarines. The first was the Nordenfelt I, a 56 tonne, 19.5 metre long vessel similar to George Garrett's ill-fated ResurgamResurgamResurgam is the name given to two early Victorian submarines designed and built by Reverend George Garrett as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed around ship hulls to defend against attack by torpedo vessels....

(1879), with a range of 240 kilometres and armed with a single torpedo and a 25.4 mm machine gunMachine gunA machine gun is a fully automatic mounted or portable firearm, usually designed to fire rounds in quick succession from an ammunition belt or large-capacity magazine, typically at a rate of several hundred rounds per minute....

. It was manufactured by Bolinders in StockholmStockholmStockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

in 1884–1885. Like the Resurgam, it operated on the surface using a 100 HP steam engine with a maximum speed of 9 kn, then it shut down its engine to dive. She was purchased by the Hellenic NavyHellenic NavyThe Hellenic Navy is the naval force of Greece, part of the Greek Armed Forces. The modern Greek navy has its roots in the naval forces of various Aegean Islands, which fought in the Greek War of Independence...

and was delivered to Salamis Naval BaseSalamis Naval BaseThe Salamis Naval Base or Naval Dock Salamis is the largest naval base in Greece. It is located in the northeastern part of Salamis Island and in Amphiali and Skaramanga. It is close to the major population centres of Athens and Piraeus....

in 1886. Following the acceptance tests, she was never used again by the Hellenic Navy and was scrapped in 1901. Nordenfelt then built the Nordenfelt II (Abdülhamid) in 1886 and Nordenfelt III (Abdülmecid) in 1887, a pair of 30 metre long submarines with twin torpedo tubes, for the Ottoman NavyOttoman NavyThe Ottoman Navy was established in the early 14th century. During its long existence it was involved in many conflicts; refer to list of Ottoman sieges and landings and list of Admirals in the Ottoman Empire for a brief chronology.- Pre-Ottoman:...

. Abdülhamid became the first submarine in history to fire a torpedo while submerged under water. The Nordenfelts had several faults. "It took as long as twelve hours to generate enough steam for submerged operations and about thirty minutes to dive. Once underwater, sudden changes in speed or direction triggered — in the words of a U. S. Navy intelligence report — "dangerous and eccentric movements." ...However, good public relations overcame bad design: Nordenfeldt always demonstrated his boats before a stellar crowd of crowned heads, and Nordenfeldt's submarines were regarded as the world standard." - 1886–1887: Carl Gassner of MainzMainzMainz under the Holy Roman Empire, and previously was a Roman fort city which commanded the west bank of the Rhine and formed part of the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire...

, German EmpireGerman EmpireThe German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

receives a patent for a zinc-carbon batteryZinc-carbon batteryA zinc–carbon dry cell or battery is packaged in a zinc can that serves as both a container and negative terminal. It was developed from the wet Leclanché cell . The positive terminal is a carbon rod surrounded by a mixture of manganese dioxide and carbon powder. The electrolyte used is a paste of...

, among the earliest examples of dry cellBattery (electricity)An electrical battery is one or more electrochemical cells that convert stored chemical energy into electrical energy. Since the invention of the first battery in 1800 by Alessandro Volta and especially since the technically improved Daniell cell in 1836, batteries have become a common power...

batteries. Originally patented in the German Empire, Gassner also received patents from Austria–Hungary, BelgiumBelgiumBelgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, the French Third RepublicFrench Third RepublicThe French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and IrelandUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and IrelandThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

(all in 1886) and the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

(in 1887). Consumer dry cells would first appear in the 1890s. In 1887, Wilhelm Hellesen of KalundborgKalundborgKalundborg is a city with a population of 16,434 in Kalundborg municipality in Denmark and the site of its municipal council. Kalundborg is on the main island Zealand, with Copenhagen, but opposite on the far western edge....

, DenmarkDenmarkDenmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

patented his own zinc-carbon battery. Within the year, Hellesen and V. Ludvigsen founded a factory in FrederiksbergFrederiksbergFrederiksberg Kommune is a municipality on the island of Zealand in Denmark. It surrounded by the city of Copenhagen. The municipality, co-extensive with its seat, covers an area of and has a total population of 98,782 making it the smallest municipality in Denmark area-wise, the fifth most...

, producing their batteries. - 1886: Charles Martin HallCharles Martin HallCharles Martin Hall was an American inventor, music enthusiast, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminium, which became the first metal to attain widespread use since the prehistoric discovery of iron.-Early years:Charles Martin Hall...

of Thompson Township, Geauga County, OhioThompson Township, Geauga County, OhioThompson Township is one of the sixteen townships of Geauga County, Ohio, United States. The 2000 census found 2,383 people in the township.-Geography:Located in the northeastern corner of the county, it borders the following townships:...

and Paul HéroultPaul HéroultThe French scientist Paul Héroult was the inventor of the aluminium electrolysis and of the electric steel furnace. He lived in Thury-Harcourt, Normandy.Christian Bickert said of him...

of Thury-HarcourtThury-HarcourtThury-Harcourt is a French commune in the Calvados department in the Basse-Normandie region in northwestern France.Situated in the Orne valley, its surroundings are much like Clécy, but the Rock of Oëtre contrasts with the plateau of Caen to the north....

, NormandyNormandyNormandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

independently discover the same inexpensive method for producing aluminiumAluminiumAluminium or aluminum is a silvery white member of the boron group of chemical elements. It has the symbol Al, and its atomic number is 13. It is not soluble in water under normal circumstances....

, which became the first metal to attain widespread use since the prehistoric discovery of ironIronIron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

. The basic invention involves passing an electric current through a bath of alumina dissolved in cryoliteCryoliteCryolite is an uncommon mineral identified with the once large deposit at Ivigtût on the west coast of Greenland, depleted by 1987....

, which results in a puddle of aluminum forming in the bottom of the retort. It has come to be known as the Hall-Héroult processHall-Héroult processThe Hall–Héroult process is the major industrial process for the production of aluminium. It involves dissolving alumina in molten cryolite, and electrolysing the molten salt bath to obtain pure aluminium metal.-Process:...

. Often overlooked is that Hall did not work alone. His research partner was Julia Brainerd Hall, an older sister. She had studied chemistry at Oberlin CollegeOberlin CollegeOberlin College is a private liberal arts college in Oberlin, Ohio, noteworthy for having been the first American institution of higher learning to regularly admit female and black students. Connected to the college is the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the oldest continuously operating...

, helped with the experiments, took laboratory notes and gave business advice to Charles. - 1886–1890: Herbert Akroyd StuartHerbert Akroyd StuartHerbert Akroyd-Stuart was an English inventor who is noted for his invention of the hot bulb engine, or heavy oil engine.-Life:...

of HalifaxHalifax, West YorkshireHalifax is a minster town, within the Metropolitan Borough of Calderdale in West Yorkshire, England. It has an urban area population of 82,056 in the 2001 Census. It is well-known as a centre of England's woollen manufacture from the 15th century onward, originally dealing through the Halifax Piece...

YorkshireWest Riding of YorkshireThe West Riding of Yorkshire is one of the three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county, County of York, West Riding , was based closely on the historic boundaries...

, EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

receives his first patent on a prototype of the hot bulb engineHot bulb engineThe hot bulb engine, or hotbulb or heavy oil engine is a type of internal combustion engine. It is an engine in which fuel is ignited by being brought into contact with a red-hot metal surface inside a bulb....

. His research culminated in an 1890 for a compression ignition engine. Production started in 1891 by Richard Hornsby & SonsRichard Hornsby & SonsRichard Hornsby & Sons was an engine and machinery manufacturer in Lincolnshire, England from 1828 until 1918. The company was a pioneer in the manufacture of the oil engine developed by Herbert Akroyd Stuart and marketed under the Hornsby-Akroyd name. The company developed an early track system...

of GranthamGranthamGrantham is a market town within the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. It bestrides the East Coast Main Line railway , the historic A1 main north-south road, and the River Witham. Grantham is located approximately south of the city of Lincoln, and approximately east of Nottingham...

, LincolnshireLincolnshireLincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...