History of the SAS

Encyclopedia

The History of the British Army

's Special Air Service

or SAS regiment begins with its formation during the Western Desert Campaign

of the Second World War, and continues to the present day. It includes their early operations in North Africa, the Greek Islands, and the Invasion of Italy. They then returned to the United Kingdom and were formed into a brigade

with two British, two French and one Belgian regiment. The SAS Brigade then conducted operations in France, Italy again, the Low Countries

and finally into Germany.

After the war the SAS were disbanded only to be reformed as a Territorial Army regiment, which then led onto the formation of the regular army 22 SAS Regiment. The new regiment has taken part in most of the United Kingdoms small wars since then. However the Ministry of Defence

does not comment on special forces matters, therefore little verifiable information exists in the public domain on the regiments recent activities.

At first service in the SAS was considered an end to an officer's career progression, however in recent years SAS officers have risen to the highest ranks in the British Army. General Peter de la Billière

was the Commander-in-Chief

of the British forces in the 1990 Gulf War. General Michael Rose became commander of the United Nations Protection Force

in Bosnia in 1994. In 1997 General Charles Guthrie

became Chief of the Defence Staff

the head of the British Armed Forces. Lieutenant-General Cedric Delves

was the Commander of the Field Army and Deputy Commander in Chief NATO Regional Headquarters Allied Forces Northern Europe (RHQ AFNORTH) in 2002–2003.

The Special Air Service began life in July 1941 from an unorthodox idea and plan by a Lieutenant

The Special Air Service began life in July 1941 from an unorthodox idea and plan by a Lieutenant

in the Scots Guards

David Stirling

, who was serving with No. 8 (Guards) Commando

. His idea was for small teams of parachute trained soldiers to operate behind enemy lines to gain intelligence, destroy enemy aircraft and attack their supply and reinforcement routes. Following a meeting with Major-General Neil Ritchie

, the Deputy Chief of Staff, he was granted an appointment with the new C-in-C Middle East, General

Claude Auchinleck

. Auchinleck liked his plan and it was endorsed by the Army High Command. At that time there was a deception organisation already in the Middle East area, which wished to create a phantom Airborne Brigade to act as a threat to enemy planning of operations. This deception unit was known as K Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade and so Stirling's unit was called L Detachment SAS Brigade.

The force initially consisted of five officers and 60 other ranks

. Following extensive training at Kabrit camp, by the River Nile, L Detachment, SAS Brigade undertook its first operation. Operation Squatter was a parachute drop behind the enemy lines in support of Operation Crusader

, they would attack airfields at Gazala

and Timimi

on the night 16/17 November 1941. Unfortunately because of enemy resistance and adverse weather conditions the mission was a disaster, 22 men were killed or captured one third of the men employed. Allowed another chance they recruited men from the Layforce

Commando, which was in the process of disbanding. Their second mission was more successful, transported by the Long Range Desert Group

(LRDG), they attacked three airfields in Libya

destroying 60 aircraft without loss.

harbour with limited success but they did damage 15 aircraft at Al-Berka

. The June 1942 Crete airfield raids

at Heraklion, Kasteli

, Tympaki

and Maleme

significant damage was caused but of the attacking force at Heraklion only Major George Jellicoe

returned. In July 1942, Stirling commanded a joint SAS/LRDG patrol that carried out raids at Fuka and Mersa Matruh airfields destroying 30 aircraft.

September was a busy month for the SAS. They were renamed 1st SAS Regiment and consisted of four British squadrons, one Free French Squadron, one Greek Squadron

, and the Special Boat Section

(SBS).

Operations they took part in were: Operation Agreement

and the diversionary raid Operation Bigamy

. Bigamy led by Stirling and supported by the LRDG, were to attempt a large-scale raid on Benghazi

to destroy the harbour, storage facilities and attack the airfields at Benina

and Barce. However, they were discovered after a clash at a roadblock. With the element of surprise lost, Stirling decided not to go ahead with the attack and ordered a withdrawal.

Agreement was a joint operation by the SAS and the LRDG who had to seize an inlet at Mersa Sciausc for the main force to land by sea. The SAS successfully evaded enemy defences assisted by German speaking members of the Special Interrogation Group

and captured Mersa Sciausc. The main landing failed, being met by heavy machine gun fire forcing the landing force and the SAS/LRDG force to surrender. Operation Anglo

a raid on two airfields on the island of Rhodes

, from which only two men returned. Destroying three aircraft, a fuel dump and numerous buildings, the surviving SBS men had to hide in the countryside for four days before they could reach the waiting submarine.

area by a special anti-SAS unit set up by the Germans. He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war

, escaping numerous times before being moved to the supposedly 'escape proof' Colditz Castle

. He was replaced as commander 1st SAS by Paddy Mayne

. In April 1943, the 1st SAS was reorganised into the Special Raiding Squadron under the command of Mayne and the Special Boat Squadron

under the command of George Jellico

. The Special Boat Squadron operated in the Aegean

and the Balkans

for the remainder of the war and was disbanded in 1945.

The Special Raiding Squadron spearheaded the invasion of Sicily Operation Husky and played more of a commando role raiding the Italian coastline, from which they suffered heavy losses at Termoli

. After Sicily they went on to serve in Italy with the newly formed 2nd SAS, a unit which had been formed in Algeria in May 1943 by Stirling's older brother Lieutenant Colonel

Bill Stirling.

The 2nd SAS had already taken part in operations in support of the Allied landings in Sicily: Operation Narcissus

was a raid by 40 members of 2nd SAS on a lighthouse on the south east coast of Sicily. The team landed on 10 July with the mission of capturing the lighthouse and the surrounding high ground. Operation Chestnut

involved two teams of ten men each, parachuted into northern Sicily on the night of 12 July, to disrupt communications, transport and the enemy in general.

On mainland Italy they were involved in Operation Begonia

which was the airborne counterpart to the amphibious Operation Jonquil, from 2 to 6 October, 61 men were parachuted between Ancona

and Pescara

. The object was to locate escaped prisoners of war in the interior and muster them on beach locations for extraction. Begonia involved the interior parachute drop by 2nd SAS. Jonquil entailed four seaborne beach parties from 2nd SAS with the Free French SAS Squadron as protection. Operation Candytuft

was a raid by 2nd SAS on 27 October. Inserted by boat on Italy's east coast between Ancona and Pescara, they were to destroy rail road bridges and disrupt rear areas.

Near the end of the year the Special Raiding Squadron reverted to their former title 1st SAS and together with 2nd SAS were withdrawn from Italy and placed under command the 1st Airborne Division.

and F Squadron

which was responsible for signals and communications, the brigade commander was Brigadier

Roderick McLeod

. The brigade was ordered to swap their beige SAS berets for the maroon parachute beret and given shoulder titles for 1, 2, 3 and 4 SAS in the Airborne colours. The French and Belgian regiments also wore the Airborne Pegasus

arm badge. The brigade now entered a period of training for their participation in the Normandy Invasion. They were prevented from conducting operations until after the start of the invasion by 21st Army Group. Their task was then to stop German reinforcements reaching the front line, by being parachuted behind the lines to assist the French Resistance

.

In support of the invasion 144 men of 1st SAS took part in Operation Houndsworth

between June and September, in the area of Lyon

, Chalon-sur-Saône

, Dijon

, Le Creusot

and Paris. At the same time 56 Men of 1st SAS also took part in Operation Bulbasket

in the Poitiers

area. They did have some success before being betrayed. Surrounded by a large German force, they were forced to disperse; later it was discovered that 36 men were missing and that 32 of them had been captured and executed by the Germans.

In mid June 150 men of the French SAS and 3,000 members of the French resistance took part in Operation Dingson

. However they were forced to disperse after their camp was attacked by the Germans. The French SAS were also involved in Operation Cooney

, Operation Samwest

and Operation Lost

during the same period.

In August 91 men from the 1st SAS were involved in Operation Loyton

. The team had the misfortune to land in the Vosges

Mountains at a time when the Germans were preparing to defend the Belfort Gap

. As a result, the Germans harried the team. The team also suffered from poor weather that prevented aerial resupply. Eventually, they broke into smaller groups to return to their own lines. During the escape 31 men were captured and executed by the Germans.

Also in August men from 2nd SAS operated from forest bases in the Rennes

area in conjunction with the resistance. Air resupply was plentiful and the resistance cooperated, which resulted in carnage. The 2nd SAS operated from the Loire through the forests of Darney

to Belfort

in just under six weeks.

Near the end of the year men from 2nd SAS were parachuted into Italy, to work with the Italian resistance in Operation Tombola

here they remained until Italy was liberated.

At one point, four groups were active deep behind enemy lines laying waste to airfields, attacking convoys and derailing trains. Towards the end of the campaign, Italian guerrillas and escaped Russian

prisoners were enlisted into an ‘Allied SAS Battalion’ which struck at the German main lines of communications.

took over command of the brigade.

The 3rd and 4th SAS were involved in Operation Amherst

in April, The operation began with the drop of 700 men on the night of the 7 April. The teams spread out to capture and protect key facilities from the Germans.

Still in Italy in Operation Tombola, Major Roy Farran

and 2nd SAS carried out a raid on a German Corps

headquarters in the Po Valley, which succeeded in killing the corps chief of staff.

The Second World War in Europe ended on 8 May by that time the SAS brigade had suffered 330 casualties, but had killed or wounded 7,733 and captured 23,000 of their enemies. Later the same month 1st and 2nd SAS were sent to Norway to disarm the 300,000 German garrison and 5th SAS were in Denmark and Germany on counter intelligence operations. The brigade was dismantled soon afterwards, in September the Belgian 5th SAS were handed over to the reformed Belgian Army

. On 1 October the 3rd and 4th French SAS were handed over to the French Army

and on 8 October the British 1st and 2nd SAS regiments were disbanded.

In 1950 they raised a squadron to fight in the Korean War

. After three months training, they were informed that the squadron would not, after all, be needed in Korea, and instead were sent to serve in the Malayan Emergency

. On arrival in Malaya they came under the command of the wartime SAS Brigade commander, Mike Calvert. They became B Squadron, Malayan Scouts (SAS),

the other units were A Squadron, which had been formed from 100 local volunteers mostly ex Second World War SAS and Chindits

and C Squadron formed from volunteers from Rhodesia

, the so called 'Happy Hundred'. By 1956 the Regiment had been enlarged to five squadrons with the addition of D Squadron and the Parachute Regiment Squadron After three years service the Rhodesians returned home and were replaced by a New Zealand squadron.

A squadron were based at Ipoh

while B and C squadrons were at Johore, during training they pioneered techniques of resupply by helicopter and also set up the "Hearts and Minds

" campaign to win over the locals with medical teams going from village to village treating the sick. With the aid of Iban

trackers from Borneo

they became experts at surviving in the jungle.

In 1951 the Malayan Scouts (SAS) had successfully recruited enough men to form a Regimental Headquarters, a headquarters squadron and four operational squadrons over 900 men. The regiment was tasked to seek, find, fix then destroy the terrorists and prevent their infiltration into protected areas. Their tactics would be long range patrols,ambush and tracking the terrorists to their bases. They trained and acquired skills in tree jumping, this involved parachuting into the thick jungle canopy and letting your parachute catch on the branches. Brought to a halt the parachutist then cut himself free and lowered himself to the ground by rope. Using inflatable boats for river patrolling, jungle fighting techniques, psychological warfare

and booby trapping terrorist supplies. Calvert was invalided back to the United Kingdom in 1951 and replaced by Lieutenant-Colonel John Sloane

.

In February 1951 54 men from B Squadron carried out the first parachute drop in the campaign in Operation Helsby, which was a major offensive in the River Perak–Belum valley, just south of the Thai border.

The need for a regular army SAS regiment had been recognised, the Malayan Scouts (SAS) were renamed 22 SAS Regiment and formally added to the army list in 1952. However B Squadron was disbanded leaving just A and D Squadrons in service

. The Malaya campaign was winding down, so they dispatched two squadrons from Malaya to assist in Oman. In January 1959 A Squadron defeated a large Guerrilla force on the Sabrina plateau. A victory that was kept from the public due to political and military sensitivities.

After Oman 22 SAS Regiment were recalled to the United Kingdom, the first time the regiment had served in there since their formation. They were initially barracked in Malvern

Worcestershire

before moving to Hereford

in 1960. Just prior to this the third SAS regiment was formed and like 21 SAS was part of the Territorial Army. 23 SAS Regiment was formed by the renaming of the Joint Reserve Reconnaissance Unit, which itself had succeeded MI.9 via a series of units (POW Rescue, Recovery and Interrogation Unit, Intelligence School 9 and the Joint Reserve POW Intelligence Organisation) Behind this change was the understanding that passive networks of escape lines had little place in the cold war world and henceforth personnel behind the lines would be rescued by specially trained units.

The regiment was sent to Borneo

for the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, where they adopted the tactics of patrolling up to 20 kilometres (12.4 mi) over the Indonesian border and used local tribesman for intelligence gathering. They at times lived in the indigenous tribes villages for five months gaining their trust. This involved showing respect for the Headman, giving gifts and providing medical treatment for the sick.

In December 1963, the SAS went onto the offensive, now under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Woodhouse they adopted a "shoot and scoot" policy to keep SAS casualties to a minimum. They were augmented by the adding to their strength of the Guards Independent Parachute Company and later the Gurkha Independent Parachute Company.In 1964 Operation Claret

In December 1963, the SAS went onto the offensive, now under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Woodhouse they adopted a "shoot and scoot" policy to keep SAS casualties to a minimum. They were augmented by the adding to their strength of the Guards Independent Parachute Company and later the Gurkha Independent Parachute Company.In 1964 Operation Claret

was initiated, soldiers were selected from the infantry regiments in theatre, placed under SAS command and known as "Killer Groups". These groups would cross the border and penetrate up to 18 kilometres (11.2 mi) disrupting the Indonesian Army

build up, forcing them to move away from the border. The Borneo campaign cost the British 59 killed 123 wounded compared to the Indonesian 600 dead. In 1964 B Squadron was re-formed from a combination of former members still with the Regiment and new recruits.

The SAS returned to Oman in 1970, the Marxist controlled South Yemen government were supporting an insurgency in the Dhofar

region what became known as the Dhofar Rebellion

. Operating under the umbrella of a British Army Training Team (BATT), they recruited, trained and commanded the local Firquts. Firquts were local tribesmen and recently surrendered enemy soldiers. This new campaign ended shortly after the Battle of Mirbat

in 1972, when a small SAS force and Firquts defeated 250 Adoo guerrillas.

for just over a month. The SAS returned in 1972 when small numbers of men were involved in intelligence gathering. The first squadron fully committed to the Provence was in 1976 and by 1977 two squadrons were operating in Northern Ireland. These squadrons used well armed covert patrols in unmarked civilian cars. Within a year four terrorist had been killed or captured and another six forced to move south into the Republic

. Members of the SAS are also believed to have served in the 14 Intelligence Company

based in Northern Ireland.

The first operation attributed to the SAS was the arrest of Sean McKenna 12 March 1975. McKenna claims he was sleeping in a house just south of the Irish border when he was woken in the night by two armed men and forced across the border, while the SAS claimed he was found wandering in a field drunk.

Their second operation was on 15 April 1976 with the arrest and killing of Peter Cleary

. Cleary, an IRA staff officer, was detained by five in a field waiting for a helicopter to land. While four men guided the aircraft in Cleary started to struggle with his guard and seize his rifle was shot.

The SAS returned to Northern Ireland in force in 1976, operating throughout the province in January 1977 Seamus Harvey armed with a shotgun was killed on a SAS ambush. On 21 June six men from G Squadron, ambushed four IRA men planting a bomb at a government building, three were shot and killed their driver managed to escape. On 10 July 1978, John Boyle, a sixteen-year-old Catholic, was exploring an old graveyard near his family's farm in County Antrim

, when he discovered an arms cache

. He told his father, who passed on the information to the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC). The next morning Boyle decided to see if the guns had been removed and was shot dead by two SAS soldiers who had been waiting undercover. In 1976 Newsweek

also reported that eight SAS men had been arrested in the Republic of Ireland supposedly as a result of a navigational error. It was later revealed that they had been in pursuit of an Provisional Irish Republican Army unit.

On 2 May 1980 Captain Herbert Westmacott

, became the highest ranking member of the SAS to be killed in Northern Ireland.

He was in command of an eight man plain clothes SAS patrol that had been alerted by the Royal Ulster Constabulary

that an IRA gun team had taken over a house in Belfast

. A car carrying three SAS men went to the rear of the house, and another car carrying five SAS men went to the front of the house. As the SAS arrived at the front of the house the IRA unit opened fire with the a M60 machine gun

, hitting Captain Westmacott in the head and shoulder killing him instantly. The remaining SAS men at the front, returned fire but were forced to withdraw. One member of the IRA team was apprehended by the SAS at the rear of the house, preparing the unit's escape in a transit van, while the other three IRA members remained inside the house. More members of the security forces were deployed to the scene, and after a brief siege the remaining members of the IRA unit surrendered. After his death Westmacott was posthumously awarded the Military Cross

. for gallantry in Northern Ireland during the period 1 February 1980 to 30 April 1980.

On 4 December 1983, a SAS patrol, found two IRA gunmen who were both armed. One with an Armalite

rifle and the other a shotgun. They did not respond when challenged so the patrol opened fire, killing the two men. A third man escaped in a car was believed to have been wounded.

On 8 May 1987 the IRA suffered its worst single loss of men, when eight men were killed by the SAS while attempting to attack the Loughgall

police station. The SAS had been informed of the attack and 24 men waited in ambush positions around and inside the police station. They opened fire when the armed IRA unit approached the station with a 200 pounds (90.7 kg) bomb, its fuse lit, in the bucket of a hijacked JCB

digge

In the late 1980s the IRA started to move operations to the European mainland. Operation Flavius

in March 1988, was an SAS operation in Gibraltar

in which three PIRA volunteers, Seán Savage

, Daniel McCann

and Mairéad Farrell

, were killed. All three had conspired to detonate a car bomb where a military band assembled for the weekly changing of the guard at the governor's residence. In Germany, in 1989 the German security forces discovered a SAS unit operating there without the permission of the German government.

In 1991 three IRA men killed by the SAS, according to reports at the time they were on their way to kill an Ulster Defence Regiment

soldier, who lived in Coagh

, when they were ambushed. These three and another seven brought the total number of IRA men killed by the SAS in the 1990s to 11.

Edward Heath

asked the Ministry of Defence

to prepare for any possible terrorist attack similar to the 1972 Munich massacre

at the Munich

Olympic Games

and ordered that the SAS Counter Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) wing be established.

Once the wing had been established each squadron would in turn rotate through counter terrorist training. The training included live firing exercises, hostage rescue and siege breaking. It was reported that during CWR training each soldier would expend 100,000 pistol rounds and would return to the CWR role on average every 16 months. Their first deployment was during the Balcombe Street Siege

, where the Metropolitan Police

had trapped a PIRA unit. Hearing on the BBC

that the SAS were being deployed the PIRA men surrendered.

The first documented action by the CRW Wing was assisting the West German counter-terrorism group GSG 9

at Mogadishu

.

started at 11:30 on 30 April 1980 when a six-man team calling itself the 'Democratic Revolutionary Movement for the Liberation of Arabistan' (DRMLA), captured the embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Prince's Gate

, South Kensington

in central London

. When the group first stormed the building, 26 hostages were taken, but five were released over the following few days. On the sixth day of the siege the kidnappers killed a hostage. This marked an escalation of the situation and prompted Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

's decision to proceed with the rescue operation. The order to deploy the SAS was given, and B Squadron the duty CRW squadron were alerted. When the first hostage was shot, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, David McNee

passed a note signed by Thatcher to the Ministry of Defence, stating this was now a "military operation".

The rescue mission started at 19:23, 5 May when the SAS assault troops at the front gained access to the embassy's first floor balcony via the roof. Another team assembled on the ground floor terrace entered via the rear of the embassy. After forcing entry five of the six terrorists were killed. Unfortunately one of the hostages was also killed by the terrorists during the assault which lasted 11 minutes. The events were broadcast live on national television and soon rebroadcast around the world gaining fame and a reputation for the SAS, that prior to the assault few outside of the military special operations community even knew of the regiments existence.

Douglas Hurd

, dispatched the SAS to bring the riot to an end on 3 October. The CRW troops arrived by helicopter landed on the roof then abseiled into the prison proper. Armed only with pistols, batons and stun grenades they brought the riot to a swift closure.

and 21 July

. It was reported in the Times

that the SAS CRW played a role in the capture of three men suspected of taking part in the failed 21 July bomb attacks. Providing expertise in explosive entry techniques to back up raids by police firearms officers. It was also reported that plain clothes SAS teams were monitoring airports and main railway stations to identify any security weaknesses and they were using civilian helicopters and two small executive to move around the country.

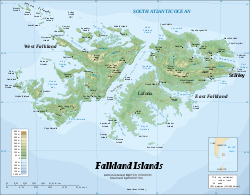

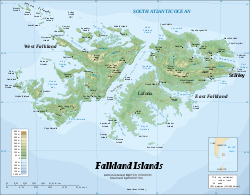

started after the Argentina

occupation of the Falkland Islands

on 2 April 1982. Brigadier Peter de la Billiere

the Director Special Forces and Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Rose, the Commander of 22 SAS Regiment, petitioned for the regiment to be included in the task force. Without waiting for official approval D Squadron which was on standby for world wide operations, departed on the 5 April for Ascension Island

. They were followed by G Squadron on the 20 April. As both squadrons sailed south the plans were for D Squadron to support operations to retake South Georgia while G Squadron would be responsible for the Falkland Islands.

Operation Paraquet

Operation Paraquet

was the code name for the first land to be liberated in the conflict. South Georgia an island to the south east of the Falkland Islands and one of the Falkland Islands Dependencies

.

In atrocious weather the SAS, SBS and Royal Marines

forced the Argentinian garrison to surrender. On the 22 April Westland Wessex

helicopters landed a SAS unit on the Fortuna Glacier

. This resulted in the loss of two of the helicopters, one on take off and one crashed into the glacier in almost zero visibility. The SAS unit were defeated by the weather and terrain and had to be evacuated after only managing to cover 500 metres (1,640.4 ft) in five hours.

The following night a SBS section succeeded in landing by helicopter and Boat Troop, D Squadron, SAS set out in five Gemini inflatable boats for the island. Two boats suffered engine failure with one crew being picked up by helicopter and the other crew got to shore. The next day 24 April a force of 75 SAS, SBS and Royal Marines advancing with naval gunfire support, reached Grytviken

and the forced the occupying Argentinians to surrender. The following day the garrison at Leith also surrendered.

between the 30 April and 2 May. The main landings were at San Carlos

on 21 May. To cover the landings D Squadron mounted a major diversionary raid at Goose Green and Darwin with fire support from . After D Squadron were returning from their raid they shot down a FMA IA 58 Pucará

with a shoulder-launched Stinger missile that had overflown their location. While the main landings were taking place a four man patrol from G Squadron had been carrying out a reconnaissance near Stanley

. They located an Argentinian helicopter dispersal area between Mount Kent

and Mount Estancia. Advising to attack at first light, the resulting attack by RAF Harrier GR3's from No. 1 Squadron RAF

destroyed one CH-47 Chinook

and the two Aérospatiale Puma

helicopters.

airstrip on West Falkland

. The force of 20 men from Mountain Troop, D Squadron, led by Captain John Hamilton

, destroyed six FMA IA 58 Pucarás, four T-34 Mentor

s and a Short SC.7 Skyvan

transport. The attack was supported by fire from . Under cover of mortar and small arms fire the SAS moved onto the airstrip and fixed explosive charges to the aircraft. Casualties were light one Argentinian was killed and two of the Squadron were wounded by shrapnel when a mine exploded.

helicopter crashed while cross-decking troops from to killing 22 men. Approaching Hermes it appeared to have an engine failure and crashed into the sea. Only nine men managed to scramble out of side door before the helicopter sank. They were the only survivors. Rescuers found bird feathers floating on the surface were the helicopter had impacted the water. It is thought that the Sea King was the victim of a bird strike. Of the 22 killed 18 were from the SAS, one from the Royal Signals and the Royal Air Force

pilot.

was the code name for the planned landing of B Squadron, SAS at the Argentinian airbase at Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego

. The initial plan was to crash land two C-130 Hercules carrying B Squadron onto the runway at Port Stanley to bring the conflict to a rapid conclusion. B Squadron arrived at Ascension Island

20 May the day after the fatal Sea King crash. They were just boarding the C-130s when word came that the operation had been cancelled.

After Mikado had been cancelled B Squadron were called upon to parachute into the South Atlantic to reinforce D Squadron. They were transported south by the two C-130s equipped with long range fuel tanks. Only one of the aircraft reached the jump point the other had to turn back with fuel problems. The parachutists were then transported to the Falkland Islands by .

After Mikado had been cancelled B Squadron were called upon to parachute into the South Atlantic to reinforce D Squadron. They were transported south by the two C-130s equipped with long range fuel tanks. Only one of the aircraft reached the jump point the other had to turn back with fuel problems. The parachutists were then transported to the Falkland Islands by .

when they were attacked by Argentine forces. Two of the patrol managed to get away but Hamilton and his signaller, Sergeant Fosenka, were pinned down. Hamilton was hit in the back by enemy fire and told Fosenka "you carry on, I'll cover your back" moments later Hamilton was killed. Sergeant Fosenka was later captured when he ran out of ammunition. The senior Argentine officer praised the heroism of Hamilton who was posthumously awarded the Military Cross

.

. Their objective was to set up a mortar and machine gun fire base to provide fire support, while the Boat Troop and six SBS men crossed Port William water in Rigid Raider

s to destroy the fuel tanks at Cortley Hill. As the assault team approached their target they came under machine gun fire, all their boats were hit and three men wounded forcing them to withdraw. At the same time the fire base came under an Argentinian artillery and infantry attack. They then had to call upon their own artillery to silence the Argentinian guns to enable D Squadron to withdraw. The raid did not destroy their intended target but Argentinian artillery continued to land on the SAS position for an hour after they had withdrawn and not on the attacking parachute battalion.

.jpg) The Gulf War

The Gulf War

started after the invasion of Kuwait

by Iraq

on 2 August 1990. The British Army response to the invasion was Operation Granby

, which included A, B and D squadrons 22 Special Air Service Regiment. Which was the largest SAS mobilisation since the Second World War. Initial plans were for the SAS to carry out their traditional raiding role behind the Iraqi lines, and operate ahead of the allied invasion, disrupting lines of communications. The SAS operating from Al Jawf, had since 20 January 1991, been working behind Iraqi lines hunting for Scud

missile launchers in the area south of the Amman

— Baghdad

highway. The patrols working on foot and in landrovers would at times carry out their own attacks, with MILAN

missiles on Scud launchers and also set up ambushes for Iraqi convoys,

On 22 January three eight man patrols from B Squadron were inserted behind the lines by a Chinook helicopter. Their mission was to locate Scud launchers and monitor the main supply route. One of the patrols Bravo Two Zero

had decided to patrol on foot. The patrol was found by an Iraqi unit and, unable to call for help because they had been issued the wrong radio frequencies, had to try and evade capture by themselves. The team under command of Andy McNab

suffered three dead and four captured; only one man, Chris Ryan

, managed to escape to Syria

. Ryan made SAS history with the "longest escape and evasion by an SAS trooper or any other soldier", covering 100 miles (160.9 km) more than SAS trooper Hugh Davidson (David) Sillito, had in the Sahara Desert in 1942. The other patrols Bravo One Zero and Bravo Three Zero had opted to use landrovers and take in more equipment returned intact to Saudi Arabia.

By the end of the war four SAS men had been killed and five captured.

in September 2000. When a combined SAS, SBS and men from 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment carried out a hostage rescue operation Operation Barras

. The objective was to rescue 11 members of the Royal Irish Regiment that were being held by a militia group known as the West Side Boys

. The rescue team transported in three Chinook and one Lynx helicopter mounted a simultaneous two-pronged attack after reaching the militia positions. After a heavy fire fight, the hostages were released and flown back to the capital Freetown

.

One member of the SAS rescue team was killed during the operation.

. However there is evidence that they took part in later operations. General

Stanley McChrystal, the American commander of NATO forces in Iraq, has commented on A Squadron 22 SAS Regiment. That when part of Task Force Black and Task Force Knight (subcomponents of Task Force 145), carried out 175 combat missions during a six month tour of duty.

Also in 2006 members of the SAS were involved in the rescue of peace activists Norman Kember

, James Loney and Harmeet Singh Sooden

. The three men had been held hostage in Iraq for 118 days during the Christian Peacemaker hostage crisis.

, the SAS are known to have taken part in the Battle of Tora Bora

. Also for the first time it has been revealed that reserve soldiers from 21 and 23 SAS Regiments have been involved in active operations.

In June 2008 a Land Rover transporting Corporal Sarah Bryant and SAS reserve soldiers Corporal Sean Reeve and Lance Corporals Richard Larkin and Paul Stout hit a mine in Helmand province

, killing all four. In October Major

Sebastian Morley, their commander in Afghanistan, resigned over what he described as "gross negligence" on the part of the Ministry of Defence that contributed to the deaths of four British troops under his command. Morley stated that the MoD's failure to properly equip his troops with adequate equipment forced them to use lightly armoured Snatch Land Rovers to travel around Afghanistan.

According to the London Sunday Times, as of March 2010 the United Kingdom Special Forces have suffered 12 killed and 70 seriously injured in Afghanistan and seven killed and 30 seriously injured in Iraq.

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

's Special Air Service

Special Air Service

Special Air Service or SAS is a corps of the British Army constituted on 31 May 1950. They are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces and have served as a model for the special forces of many other countries all over the world...

or SAS regiment begins with its formation during the Western Desert Campaign

Western Desert Campaign

The Western Desert Campaign, also known as the Desert War, was the initial stage of the North African Campaign during the Second World War. The campaign was heavily influenced by the availability of supplies and transport. The ability of the Allied forces, operating from besieged Malta, to...

of the Second World War, and continues to the present day. It includes their early operations in North Africa, the Greek Islands, and the Invasion of Italy. They then returned to the United Kingdom and were formed into a brigade

Brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that is typically composed of two to five battalions, plus supporting elements depending on the era and nationality of a given army and could be perceived as an enlarged/reinforced regiment...

with two British, two French and one Belgian regiment. The SAS Brigade then conducted operations in France, Italy again, the Low Countries

Low Countries

The Low Countries are the historical lands around the low-lying delta of the Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse rivers, including the modern countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of northern France and western Germany....

and finally into Germany.

After the war the SAS were disbanded only to be reformed as a Territorial Army regiment, which then led onto the formation of the regular army 22 SAS Regiment. The new regiment has taken part in most of the United Kingdoms small wars since then. However the Ministry of Defence

Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom)

The Ministry of Defence is the United Kingdom government department responsible for implementation of government defence policy and is the headquarters of the British Armed Forces....

does not comment on special forces matters, therefore little verifiable information exists in the public domain on the regiments recent activities.

At first service in the SAS was considered an end to an officer's career progression, however in recent years SAS officers have risen to the highest ranks in the British Army. General Peter de la Billière

Peter de la Billière

General Sir Peter Edgar de la Cour de la Billière, KCB, KBE, DSO, MC & Bar is a former British Army officer who was Director SAS during the Iranian Embassy Siege and Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in the 1990 Gulf War...

was the Commander-in-Chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

of the British forces in the 1990 Gulf War. General Michael Rose became commander of the United Nations Protection Force

United Nations Protection Force

The United Nations Protection Force ', was the first United Nations peacekeeping force in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars. It existed between the beginning of UN involvement in February 1992, and its restructuring into other forces in March 1995...

in Bosnia in 1994. In 1997 General Charles Guthrie

Charles Guthrie, Baron Guthrie of Craigiebank

General Charles Ronald Llewelyn Guthrie, Baron Guthrie of Craigiebank, was Chief of the Defence Staff between 1997 and 2001 and Chief of the General Staff, the professional head of the British Army, between 1994 and 1997.-Army career:...

became Chief of the Defence Staff

Chief of the Defence Staff (United Kingdom)

The Chief of the Defence Staff is the professional head of the British Armed Forces, a senior official within the Ministry of Defence, and the most senior uniformed military adviser to the Secretary of State for Defence and the Prime Minister...

the head of the British Armed Forces. Lieutenant-General Cedric Delves

Cedric Delves

Lieutenant General Sir Cedric Norman George Delves KBE DSO is a former British Army general.-Military career:Educated at Woolverstone Hall School, Cedric Delves was commissioned into the Devonshire and Dorset Regiment in 1968...

was the Commander of the Field Army and Deputy Commander in Chief NATO Regional Headquarters Allied Forces Northern Europe (RHQ AFNORTH) in 2002–2003.

Second World War

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

in the Scots Guards

Scots Guards

The Scots Guards is a regiment of the Guards Division of the British Army, whose origins lie in the personal bodyguard of King Charles I of England and Scotland...

David Stirling

David Stirling

Colonel Sir Archibald David Stirling, DSO, DFC, OBE was a Scottish laird, mountaineer, World War II British Army officer, and the founder of the Special Air Service.-Life before the war:...

, who was serving with No. 8 (Guards) Commando

No. 8 (Guards) Commando

No. 8 Commando was a unit of the British Commandos and part of the British Army during the Second World War. The Commando was formed in June 1940 primarily from members of the Brigade of Guards. It was one of the units selected to be sent to the Middle East as part of Layforce...

. His idea was for small teams of parachute trained soldiers to operate behind enemy lines to gain intelligence, destroy enemy aircraft and attack their supply and reinforcement routes. Following a meeting with Major-General Neil Ritchie

Neil Ritchie

General Sir Neil Methuen Ritchie GBE, KCB, DSO, MC, KStJ was a senior British army officer during the Second World War.-Military career:...

, the Deputy Chief of Staff, he was granted an appointment with the new C-in-C Middle East, General

General

A general officer is an officer of high military rank, usually in the army, and in some nations, the air force. The term is widely used by many nations of the world, and when a country uses a different term, there is an equivalent title given....

Claude Auchinleck

Claude Auchinleck

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, GCB, GCIE, CSI, DSO, OBE , nicknamed "The Auk", was a British army commander during World War II. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, where he developed a love of the country and a lasting affinity for the soldiers...

. Auchinleck liked his plan and it was endorsed by the Army High Command. At that time there was a deception organisation already in the Middle East area, which wished to create a phantom Airborne Brigade to act as a threat to enemy planning of operations. This deception unit was known as K Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade and so Stirling's unit was called L Detachment SAS Brigade.

The force initially consisted of five officers and 60 other ranks

Other Ranks

Other Ranks in the British Army, Royal Marines and Royal Air Force are those personnel who are not commissioned officers. In the Royal Navy, these personnel are called ratings...

. Following extensive training at Kabrit camp, by the River Nile, L Detachment, SAS Brigade undertook its first operation. Operation Squatter was a parachute drop behind the enemy lines in support of Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader was a military operation by the British Eighth Army between 18 November–30 December 1941. The operation successfully relieved the 1941 Siege of Tobruk....

, they would attack airfields at Gazala

Gazala

Gazala, or Ain el Gazala , is a small Libyan village near the coast in the northeastern portion of the country. It is located west of Tobruk....

and Timimi

Timimi

Timimi, At Timimi or Tmimi, is a small village in Libya about 75 km east of Derna and 100 km west of Tobruk. It is on the eastern shores of the Libyan coastline of the Mediterranean Sea.-Geography:...

on the night 16/17 November 1941. Unfortunately because of enemy resistance and adverse weather conditions the mission was a disaster, 22 men were killed or captured one third of the men employed. Allowed another chance they recruited men from the Layforce

Layforce

Layforce was an ad hoc military formation of the British Army consisting of a number of commando units during the Second World War.Formed in February 1941 under the command of Colonel Robert Laycock, after whom the force was named, it consisted of approximately 2,000 men and served in the Middle...

Commando, which was in the process of disbanding. Their second mission was more successful, transported by the Long Range Desert Group

Long Range Desert Group

The Long Range Desert Group was a reconnaissance and raiding unit of the British Army during the Second World War. The commander of the German Afrika Corps, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, admitted that the LRDG "caused us more damage than any other British unit of equal strength".Originally called...

(LRDG), they attacked three airfields in Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

destroying 60 aircraft without loss.

1942

Their first mission in 1942, was an attack on Bouerat. Transported by the LRDG, they caused severe damage to the harbour, petrol tanks and storage facilities. This was followed up in March by a raid on BenghaziBenghazi

Benghazi is the second largest city in Libya, the main city of the Cyrenaica region , and the former provisional capital of the National Transitional Council. The wider metropolitan area is also a district of Libya...

harbour with limited success but they did damage 15 aircraft at Al-Berka

Al-Berka

Al-Berka is a Basic People's Congress administrative division of Benghazi, Libya....

. The June 1942 Crete airfield raids

June 1942 Crete airfield raids

Operation Albumen was the name given to British Commando raids in June 1942, on German airfields in the Axis-occupied Greek island of Crete, to prevent them from being used for supporting the Afrika Korps in the Western Desert Campaign in World War II...

at Heraklion, Kasteli

Kasteli

Kastelli is a village and a former municipality in the Heraklion peripheral unit, Crete, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Minoa Pediada, of which it is a municipal unit...

, Tympaki

Tympaki Airport

Tympaki Airport is a military airport in Tympaki, Crete, Greece. It has also been used for car racing but it belongs to the Hellenic Air Force.The 138 Σ.Μ of H.A.F. operates at the airport. The airport also has a TACAN system for the aircraft.The airport used to have another runway but now it's...

and Maleme

Maleme Airport

Maleme Airport is an airport situated at Maleme, Crete. It has two runways & with no lights. The airport is closed for commercial aviation but it's used by Chania Aeroclub. The airport operated until 1959 as the main public airport of Chania. Today the use from the Hellenic Air Force is limited...

significant damage was caused but of the attacking force at Heraklion only Major George Jellicoe

George Jellicoe, 2nd Earl Jellicoe

George Patrick John Rushworth Jellicoe, 2nd Earl Jellicoe, KBE, DSO, MC, PC, FRS was a British politician and statesman, diplomat and businessman....

returned. In July 1942, Stirling commanded a joint SAS/LRDG patrol that carried out raids at Fuka and Mersa Matruh airfields destroying 30 aircraft.

September was a busy month for the SAS. They were renamed 1st SAS Regiment and consisted of four British squadrons, one Free French Squadron, one Greek Squadron

Sacred Band (World War II)

The Sacred band was a Greek special forces unit formed in 1942 in the Middle East, composed entirely of Greek officers and officer cadets under the command of Col. Christodoulos Tsigantes. It fought alongside the SAS in the Libyan desert and the Aegean, as well as with General Leclerc's Free...

, and the Special Boat Section

Special Boat Service

The Special Boat Service is the special forces unit of the British Royal Navy. Together with the Special Air Service, Special Reconnaissance Regiment and the Special Forces Support Group they form the United Kingdom Special Forces and come under joint control of the same Director Special...

(SBS).

Operations they took part in were: Operation Agreement

Operation Agreement

Operation Agreement consisted of a series of ground and amphibious operations carried out by British, Rhodesian and New Zealand forces on German and Italian-held Tobruk on 13 September 1942, during the Second World War. A Special Interrogation Group, fluent in German, also took part in missions...

and the diversionary raid Operation Bigamy

Operation Bigamy

Operation Bigamy was a raid during the Second World War by the Special Air Service in September 1942. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling and supported by the Long Range Desert Group. The force were to destroy the harbour and storage facilities at Benghazi and raid the airfield...

. Bigamy led by Stirling and supported by the LRDG, were to attempt a large-scale raid on Benghazi

Benghazi

Benghazi is the second largest city in Libya, the main city of the Cyrenaica region , and the former provisional capital of the National Transitional Council. The wider metropolitan area is also a district of Libya...

to destroy the harbour, storage facilities and attack the airfields at Benina

Benina

Benina is a Basic People's Congress administrative division of Benghazi, Libya.It contains the Benina International Airport....

and Barce. However, they were discovered after a clash at a roadblock. With the element of surprise lost, Stirling decided not to go ahead with the attack and ordered a withdrawal.

Agreement was a joint operation by the SAS and the LRDG who had to seize an inlet at Mersa Sciausc for the main force to land by sea. The SAS successfully evaded enemy defences assisted by German speaking members of the Special Interrogation Group

Special Interrogation Group

The Special Interrogation Group was a unit of the British Army during World War II. It was organized from German-speaking Jewish volunteers from the British Mandate of Palestine...

and captured Mersa Sciausc. The main landing failed, being met by heavy machine gun fire forcing the landing force and the SAS/LRDG force to surrender. Operation Anglo

Operation Anglo

Operation Anglo was a British Commando raid on the occupied island of Rhodes during the Second World War. The raid was carried out by eight men of the Special Boat Section assisted by four Greeks....

a raid on two airfields on the island of Rhodes

Rhodes

Rhodes is an island in Greece, located in the eastern Aegean Sea. It is the largest of the Dodecanese islands in terms of both land area and population, with a population of 117,007, and also the island group's historical capital. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within...

, from which only two men returned. Destroying three aircraft, a fuel dump and numerous buildings, the surviving SBS men had to hide in the countryside for four days before they could reach the waiting submarine.

1943

David Stirling who was by that time sometimes referred to as the "Phantom Major" by the Germans, was captured in January 1943 in the GabèsGabès

Gabès , also spelt Cabès, Cabes, Kabes, Gabbs and Gaps, the ancient Tacape, is the capital city of the Gabès Governorate, a province of Tunisia. It lies on the coast of the Gulf of Gabès. With a population of 116,323 it is the 6th largest Tunisian city.-History:Strabo refers to Tacape as an...

area by a special anti-SAS unit set up by the Germans. He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

, escaping numerous times before being moved to the supposedly 'escape proof' Colditz Castle

Colditz Castle

Colditz Castle is a Renaissance castle in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden, and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony in Germany. Used as a workhouse for the indigent and a mental institution for over 100 years, it gained international fame as a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II for...

. He was replaced as commander 1st SAS by Paddy Mayne

Paddy Mayne

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Blair "Paddy" Mayne DSO & Three Bars was a Northern Irish soldier, solicitor, Ireland rugby union international, amateur boxer, polar explorer and a founding member of the Special Air Service .-Early life and sporting achievements:Robert Blair "Paddy" Mayne was born in...

. In April 1943, the 1st SAS was reorganised into the Special Raiding Squadron under the command of Mayne and the Special Boat Squadron

Special Boat Service

The Special Boat Service is the special forces unit of the British Royal Navy. Together with the Special Air Service, Special Reconnaissance Regiment and the Special Forces Support Group they form the United Kingdom Special Forces and come under joint control of the same Director Special...

under the command of George Jellico

George Jellicoe, 2nd Earl Jellicoe

George Patrick John Rushworth Jellicoe, 2nd Earl Jellicoe, KBE, DSO, MC, PC, FRS was a British politician and statesman, diplomat and businessman....

. The Special Boat Squadron operated in the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

and the Balkans

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

for the remainder of the war and was disbanded in 1945.

The Special Raiding Squadron spearheaded the invasion of Sicily Operation Husky and played more of a commando role raiding the Italian coastline, from which they suffered heavy losses at Termoli

Termoli

Termoli is a town and comune on the Adriatic coast of Italy, in the province of Campobasso, region of Molise. It has a population of around 32,000, having expanded quickly after World War II, and it is a local resort town known for its beaches and old fortifications...

. After Sicily they went on to serve in Italy with the newly formed 2nd SAS, a unit which had been formed in Algeria in May 1943 by Stirling's older brother Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

Bill Stirling.

The 2nd SAS had already taken part in operations in support of the Allied landings in Sicily: Operation Narcissus

Operation Narcissus

During World War II, Operation Narcissus was a raid by forty members of the Special Air Service on a lighthouse on the southeast coast of Sicily. The team landed on 10 July 1943 with the mission of capturing the lighthouse and the surrounding high ground....

was a raid by 40 members of 2nd SAS on a lighthouse on the south east coast of Sicily. The team landed on 10 July with the mission of capturing the lighthouse and the surrounding high ground. Operation Chestnut

Operation Chestnut

During World War II, Operation Chestnut was a failed British raid by 2 Special Air Service, conducted in support of the Allied invasion of Sicily....

involved two teams of ten men each, parachuted into northern Sicily on the night of 12 July, to disrupt communications, transport and the enemy in general.

On mainland Italy they were involved in Operation Begonia

Operation Begonia

During World War II, Operation Begonia was the airborne counterpart to the amphibious Operation Jonquil, conducted by British SAS and Eighth Army Airborne between Ancona and Pescara, Italy, from 2 to 6 October, 1943. Total operational force comprised 61 men.The object was to locate escaped POWs in...

which was the airborne counterpart to the amphibious Operation Jonquil, from 2 to 6 October, 61 men were parachuted between Ancona

Ancona

Ancona is a city and a seaport in the Marche region, in central Italy, with a population of 101,909 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region....

and Pescara

Pescara

Pescara is the capital city of the Province of Pescara, in the Abruzzo region of Italy. As of January 1, 2007 it was the most populated city within Abruzzo at 123,059 residents, 400,000 with the surrounding metropolitan area...

. The object was to locate escaped prisoners of war in the interior and muster them on beach locations for extraction. Begonia involved the interior parachute drop by 2nd SAS. Jonquil entailed four seaborne beach parties from 2nd SAS with the Free French SAS Squadron as protection. Operation Candytuft

Operation Candytuft

During World War II, Operation Candytuft was a British raid by 2nd Special Air Service launched on 27 October 1943.-Description:Inserted by boat on Italy’s east coast between Ancona and Pescara, the troopers were to destroy railway bridges and disrupt rear areas. The raid was conducted by No. 3...

was a raid by 2nd SAS on 27 October. Inserted by boat on Italy's east coast between Ancona and Pescara, they were to destroy rail road bridges and disrupt rear areas.

Near the end of the year the Special Raiding Squadron reverted to their former title 1st SAS and together with 2nd SAS were withdrawn from Italy and placed under command the 1st Airborne Division.

1944

In March 1944 the 1st and 2nd SAS Regiments returned to the United Kingdom and joined a newly formed SAS Brigade of the Army Air Corps. The other units in the Brigade were the French 3rd and 4th SAS, the Belgian 5th SAS5 SAS

The 5th Special Air Service or 5th SAS was an elite airborne unit during World War II, consisting entirely of Belgian volunteers. It saw action as part of the SAS Brigade in Normandy, Northern France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. Initially trained in sabotage and intelligence gathering,...

and F Squadron

GHQ Liaison Regiment

GHQ Liaison Regiment was a special reconnaissance unit first formed in 1939 during the early stages of World War II and based at Pembroke Lodge, a Georgian house in Richmond Park, London.- History :...

which was responsible for signals and communications, the brigade commander was Brigadier

Brigadier

Brigadier is a senior military rank, the meaning of which is somewhat different in different military services. The brigadier rank is generally superior to the rank of colonel, and subordinate to major general....

Roderick McLeod

Roderick McLeod

Lieutenant General Sir Roderick William McLeod GBE KCB was a British Army General who achieved high office in the 1950s.-Military career:...

. The brigade was ordered to swap their beige SAS berets for the maroon parachute beret and given shoulder titles for 1, 2, 3 and 4 SAS in the Airborne colours. The French and Belgian regiments also wore the Airborne Pegasus

Pegasus

Pegasus is one of the best known fantastical as well as mythological creatures in Greek mythology. He is a winged divine horse, usually white in color. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as horse-god, and foaled by the Gorgon Medusa. He was the brother of Chrysaor, born at a single birthing...

arm badge. The brigade now entered a period of training for their participation in the Normandy Invasion. They were prevented from conducting operations until after the start of the invasion by 21st Army Group. Their task was then to stop German reinforcements reaching the front line, by being parachuted behind the lines to assist the French Resistance

French Resistance

The French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

.

In support of the invasion 144 men of 1st SAS took part in Operation Houndsworth

Operation Houndsworth

Operation Houndsworth was the codename for a British Special Air Service operation during the Second World War. The operation carried out by 'A' Squadron, 1st Special Air Service between 6 June and 6 September 1944, was centred around Dijon in the Burgundy region of France...

between June and September, in the area of Lyon

Lyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

, Chalon-sur-Saône

Chalon-sur-Saône

Chalon-sur-Saône is a commune in the Saône-et-Loire department in the region of Bourgogne in eastern France.It is a sub-prefecture of the department. It is the largest city in the department; however, the department capital is the smaller city of Mâcon....

, Dijon

Dijon

Dijon is a city in eastern France, the capital of the Côte-d'Or département and of the Burgundy region.Dijon is the historical capital of the region of Burgundy. Population : 151,576 within the city limits; 250,516 for the greater Dijon area....

, Le Creusot

Le Creusot

Le Creusot is a commune in the Saône-et-Loire department in the region of Bourgogne in eastern France.The inhabitants are known as Creusotins. Formerly a mining town, its economy is now dominated by metallurgical companies such as ArcelorMittal, Schneider Electric, and Alstom.Since the 1990s, the...

and Paris. At the same time 56 Men of 1st SAS also took part in Operation Bulbasket

Operation Bulbasket

Operation Bulbasket was an ill-fated operation by 'B' Squadron, 1st Special Air Service, behind German lines in German occupied France, between June and August 1944...

in the Poitiers

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the Clain river in west central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and of the Poitou-Charentes region. The centre is picturesque and its streets are interesting for predominant remains of historical architecture, especially from the Romanesque...

area. They did have some success before being betrayed. Surrounded by a large German force, they were forced to disperse; later it was discovered that 36 men were missing and that 32 of them had been captured and executed by the Germans.

In mid June 150 men of the French SAS and 3,000 members of the French resistance took part in Operation Dingson

Operation Dingson

Operation Dingson was an operation in the Second World War, conducted by about 178 Free French paratroops of the 4th Special Air Service , commanded by Colonel Pierre-Louis Bourgoin, who jumped into German occupied France near Vannes, Morbihan, Southern Brittany, in Plumelec, on the night of 5...

. However they were forced to disperse after their camp was attacked by the Germans. The French SAS were also involved in Operation Cooney

Operation Cooney

On 7 June 1944, 297 Squadron took part in Operation Cooney by providing 2 of the 9 aircraft of 38 Group that were used to deploy elements of the 4th Free French Parachute Battalion or 2eme RCP also known as 4th SAS....

, Operation Samwest

Operation Samwest

During World War II, Operation Samwest was a large raid conducted by 116 Free French paratroops of the 4th Special Air Service Regiment. Their objective was to hinder movement of German troops from west Brittany to the Normandy beaches via ambush and sabotage attempts.The first phase of the...

and Operation Lost

Operation Lost

During World War II, Operation Lost was a reactive seven-man Special Air Service operation inserted into Brittany alongside Operation Dingson on 22-23 June 1944...

during the same period.

In August 91 men from the 1st SAS were involved in Operation Loyton

Operation Loyton

Operation Loyton was the codename given to an ill-fated Special Air Service mission in the Vosges department of France during the Second World War....

. The team had the misfortune to land in the Vosges

Vosges

Vosges is a French department, named after the local mountain range. It contains the hometown of Joan of Arc, Domrémy.-History:The Vosges department is one of the original 83 departments of France, created on February 9, 1790 during the French Revolution. It was made of territories that had been...

Mountains at a time when the Germans were preparing to defend the Belfort Gap

Belfort Gap

The Belfort Gap is a plateau located between the northern end of the Jura Mountains and the southernmost part of the Vosges mountains. Its altitude varies between 345 meters at its lowest and a little more than 400 meters in the area of the watershed between the catchment areas of the Rhine and...

. As a result, the Germans harried the team. The team also suffered from poor weather that prevented aerial resupply. Eventually, they broke into smaller groups to return to their own lines. During the escape 31 men were captured and executed by the Germans.

Also in August men from 2nd SAS operated from forest bases in the Rennes

Rennes

Rennes is a city in the east of Brittany in northwestern France. Rennes is the capital of the region of Brittany, as well as the Ille-et-Vilaine department.-History:...

area in conjunction with the resistance. Air resupply was plentiful and the resistance cooperated, which resulted in carnage. The 2nd SAS operated from the Loire through the forests of Darney

Darney

Darney is a commune in the Vosges department in Lorraine in northeastern France.It is located in the Vôge Plateau, around the location of the source of the river Saône. Darney is known for its forest of oak and beech trees.-History:...

to Belfort

Belfort

Belfort is a commune in the Territoire de Belfort department in Franche-Comté in northeastern France and is the prefecture of the department. It is located on the Savoureuse, on the strategically important natural route between the Rhine and the Rhône – the Belfort Gap or Burgundian Gate .-...

in just under six weeks.

Near the end of the year men from 2nd SAS were parachuted into Italy, to work with the Italian resistance in Operation Tombola

Operation Tombola

During World War II, Operation Tombola was a major Special Air Service raid on German rear areas in Italy.Fifty men parachuted on Cusna Mountain area between 4th and 24th March 1945, under command of Major Roy Farran...

here they remained until Italy was liberated.

At one point, four groups were active deep behind enemy lines laying waste to airfields, attacking convoys and derailing trains. Towards the end of the campaign, Italian guerrillas and escaped Russian

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

prisoners were enlisted into an ‘Allied SAS Battalion’ which struck at the German main lines of communications.

1945

In March the former Chindit commander, Brigadier Mike CalvertMike Calvert

James Michael Calvert DSO and Bar was a British soldier involved in special operations in World War II. The degree to which he led very risky attacks in person led to his becoming widely known as "Mad Mike". Calvert was court-martialled and dismissed from the Army in 1952...

took over command of the brigade.

The 3rd and 4th SAS were involved in Operation Amherst

Operation Amherst

Operation Amherst was a Free French SAS attack designed to capture intact Dutch canals, bridges and airfields during world war II.-The battle:...

in April, The operation began with the drop of 700 men on the night of the 7 April. The teams spread out to capture and protect key facilities from the Germans.

Still in Italy in Operation Tombola, Major Roy Farran

Roy Farran

Major Roy Alexander Farran DSO, MC & Two Bars was a British-Canadian soldier, politician, farmer, author and journalist...

and 2nd SAS carried out a raid on a German Corps

Corps

A corps is either a large formation, or an administrative grouping of troops within an armed force with a common function such as Artillery or Signals representing an arm of service...

headquarters in the Po Valley, which succeeded in killing the corps chief of staff.

The Second World War in Europe ended on 8 May by that time the SAS brigade had suffered 330 casualties, but had killed or wounded 7,733 and captured 23,000 of their enemies. Later the same month 1st and 2nd SAS were sent to Norway to disarm the 300,000 German garrison and 5th SAS were in Denmark and Germany on counter intelligence operations. The brigade was dismantled soon afterwards, in September the Belgian 5th SAS were handed over to the reformed Belgian Army

Belgian Army

The Land Component is organised using the concept of capacities, whereby units are gathered together according to their function and material. Within this framework, there are five capacities: the command capacity, the combat capacity, the support capacity, the services capacity and the training...

. On 1 October the 3rd and 4th French SAS were handed over to the French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

and on 8 October the British 1st and 2nd SAS regiments were disbanded.

Malaya

At the end of the war the British Government could see no need for a SAS type regiment, however in 1946 it was decided that there was a need for a long term deep penetration commando or SAS unit. A new SAS regiment was raised as part of the Territorial Army. The title chosen for the new regiment was 21st SAS Regiment (V) and the regiment chosen to take on the SAS mantle was the Artists Rifles. The new 21 SAS Regiment came into existence on 1 January 1947 and took over the Artists Rifles headquarters at Dukes Road, Euston.In 1950 they raised a squadron to fight in the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

. After three months training, they were informed that the squadron would not, after all, be needed in Korea, and instead were sent to serve in the Malayan Emergency

Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency was a guerrilla war fought between Commonwealth armed forces and the Malayan National Liberation Army , the military arm of the Malayan Communist Party, from 1948 to 1960....

. On arrival in Malaya they came under the command of the wartime SAS Brigade commander, Mike Calvert. They became B Squadron, Malayan Scouts (SAS),

the other units were A Squadron, which had been formed from 100 local volunteers mostly ex Second World War SAS and Chindits

Chindits

The Chindits were a British India "Special Force" that served in Burma and India in 1943 and 1944 during the Burma Campaign in World War II. They were formed into long range penetration groups trained to operate deep behind Japanese lines...

and C Squadron formed from volunteers from Rhodesia

Rhodesia

Rhodesia , officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state located in southern Africa that existed between 1965 and 1979 following its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965...

, the so called 'Happy Hundred'. By 1956 the Regiment had been enlarged to five squadrons with the addition of D Squadron and the Parachute Regiment Squadron After three years service the Rhodesians returned home and were replaced by a New Zealand squadron.

A squadron were based at Ipoh

Ipoh

Ipoh is the capital city of Perak state, Malaysia. It is approximately 200 km north of Kuala Lumpur on the North-South Expressway....

while B and C squadrons were at Johore, during training they pioneered techniques of resupply by helicopter and also set up the "Hearts and Minds

Hearts and Minds

Hearts and Minds may refer to:* A biblical quotation; see the Wikisource link-Film:* Hearts and Minds , a 1974 documentary film about the Vietnam War-Television:...

" campaign to win over the locals with medical teams going from village to village treating the sick. With the aid of Iban

Iban people

The Ibans are a branch of the Dayak peoples of Borneo. In Malaysia, most Ibans are located in Sarawak, a small portion in Sabah and some in west Malaysia. They were formerly known during the colonial period by the British as Sea Dayaks. Ibans were renowned for practising headhunting and...

trackers from Borneo

Borneo

Borneo is the third largest island in the world and is located north of Java Island, Indonesia, at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia....

they became experts at surviving in the jungle.

In 1951 the Malayan Scouts (SAS) had successfully recruited enough men to form a Regimental Headquarters, a headquarters squadron and four operational squadrons over 900 men. The regiment was tasked to seek, find, fix then destroy the terrorists and prevent their infiltration into protected areas. Their tactics would be long range patrols,ambush and tracking the terrorists to their bases. They trained and acquired skills in tree jumping, this involved parachuting into the thick jungle canopy and letting your parachute catch on the branches. Brought to a halt the parachutist then cut himself free and lowered himself to the ground by rope. Using inflatable boats for river patrolling, jungle fighting techniques, psychological warfare

Psychological warfare

Psychological warfare , or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations , have been known by many other names or terms, including Psy Ops, Political Warfare, “Hearts and Minds,” and Propaganda...

and booby trapping terrorist supplies. Calvert was invalided back to the United Kingdom in 1951 and replaced by Lieutenant-Colonel John Sloane

John Sloane

John Sloane was a U.S. Representative from Ohio and later the Treasurer of the United States.Born in York, Pennsylvania, Sloane moved to Ohio in early youth.He completed preparatory studies....

.

In February 1951 54 men from B Squadron carried out the first parachute drop in the campaign in Operation Helsby, which was a major offensive in the River Perak–Belum valley, just south of the Thai border.

The need for a regular army SAS regiment had been recognised, the Malayan Scouts (SAS) were renamed 22 SAS Regiment and formally added to the army list in 1952. However B Squadron was disbanded leaving just A and D Squadrons in service

Oman and Borneo

In 1958 the SAS got a new commander Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony Deane-DrummondAnthony Deane-Drummond

Major General Anthony John Deane–Drummond CB, DSO, MC & Bar is a retired officer of the Royal Signals in the British Army, whose career was mostly spent with airborne forces....

. The Malaya campaign was winding down, so they dispatched two squadrons from Malaya to assist in Oman. In January 1959 A Squadron defeated a large Guerrilla force on the Sabrina plateau. A victory that was kept from the public due to political and military sensitivities.

After Oman 22 SAS Regiment were recalled to the United Kingdom, the first time the regiment had served in there since their formation. They were initially barracked in Malvern

Malvern, Worcestershire

Malvern is a town and civil parish in Worcestershire, England, governed by Malvern Town Council. As of the 2001 census it has a population of 28,749, and includes the historical settlement and commercial centre of Great Malvern on the steep eastern flank of the Malvern Hills, and the former...

Worcestershire

Worcestershire

Worcestershire is a non-metropolitan county, established in antiquity, located in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire" NUTS 2 region...

before moving to Hereford

Hereford

Hereford is a cathedral city, civil parish and county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, southwest of Worcester, and northwest of Gloucester...

in 1960. Just prior to this the third SAS regiment was formed and like 21 SAS was part of the Territorial Army. 23 SAS Regiment was formed by the renaming of the Joint Reserve Reconnaissance Unit, which itself had succeeded MI.9 via a series of units (POW Rescue, Recovery and Interrogation Unit, Intelligence School 9 and the Joint Reserve POW Intelligence Organisation) Behind this change was the understanding that passive networks of escape lines had little place in the cold war world and henceforth personnel behind the lines would be rescued by specially trained units.