.gif)

History of the United States (1849–1865)

Encyclopedia

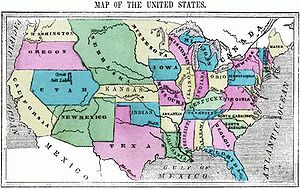

Issues of slavery in the new territories acquired in the War with Mexico (which ended in 1848) were temporarily resolved by the Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

. One provision, the Fugitive Slave Law, sparked intense controversy, as revealed in the enormous interest in the plight of the escaped slave in Uncle Tom's Cabin," an anti-slavery novel and play.

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Kansas-Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opening new lands for settlement, and had the effect of repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by allowing settlers in those territories to determine through Popular Sovereignty if they would allow slavery within...

reversed long-standing compromises by providing that each new state of the Union would decide its posture on slavery. The newly formed Republican party stood against the expansion of slavery and won control of most northern states (with enough electoral votes to win the presidency in 1860). The invasion of Bloody Kansas by pro- and anti-slavery factions, with resulting bloodshed, angered both North and South, The Supreme Court tried to resolve the issue of slavery in the territories with a pro-slavery Dred Scott Decision that angered the North.

After the 1860 election of Republican Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

, eleven Southern states

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

declared their secession from the United States between late 1860 and 1861, establishing a rebel government, the Confederate States of America

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

on American soil, on February 9, 1861. The Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

began when Confederate General Pierre Beauregard opened fire upon Union troops at Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a Third System masonry coastal fortification located in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The fort is best known as the site upon which the shots initiating the American Civil War were fired, at the Battle of Fort Sumter.- Construction :...

in South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

.

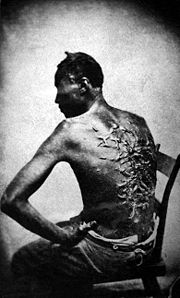

The next four years were the darkest in American history as the nation tore itself apart over the long and bitter issues of slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

and states rights. The increasingly urban, industrialized Northern states

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

(the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

) eventually defeated the mainly rural, agricultural Southern states (the Confederacy), but between 600,000 and 700,000 Americans on both sides were killed, and much of the land in the South was devastated. Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white

European American

A European American is a citizen or resident of the United States who has origins in any of the original peoples of Europe...

males aged 13 to 43 died in the war, including 6% in the North and an extraordinary 18% in the South. In the end, however, slavery was abolished, and the Union was restored.

Developing a market economy

By the 1840s, the Industrial RevolutionIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

was transforming the Northeast, with a dense network of railroads, canals, textile mills, small industrial cities, and growing commercial centers, with hubs in Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. Although manufacturing interests, especially in Pennsylvania, sought a high tariff, the actual tariff in effect was low, and was reduced several times, with the 1857 tariff the lowest in decades. The Midwest region, based on farming and increasingly on animal production, was growing rapidly, using the railroads and river systems to ship food to slave plantations in the south, industrial cities in the East, and industrial cities in Britain and Europe.

In the south, the cotton plantations were flourishing, thanks to the very high price of cotton on the world market. Cotton production wears out the land, and so the center of gravity was continually moving west. The annexation of Texas in 1845 opened up the last great cotton lands. Meanwhile other commodities, such as tobacco in Virginia and North Carolina, were in the doldrums. Slavery was dying out in the upper South, and survived because of sales of slaves to the growing cotton plantations in the Southwest. While the Northeast was rapidly urbanizing, and urban centers such as Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Chicago were rapidly growing in the Midwest, the South remained overwhelmingly rural. The great wealth generated by slavery was used to buy new lands, and more slaves. At all times the great majority of Southern whites owned no slaves, and operated farms on a subsistence basis, serving small local markets.

A transportation revolution was underway thanks to heavy infusions of capital from London, Paris, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Hundreds of local short haul lines were being consolidated to form a railroad system, that could handle long-distance shipment of farm and industrial products, as well as passengers. In the South, there were few systems, and most railroad lines were short haul project designed to move cotton to the nearest river or ocean port. Meanwhile, steamboats provided a good transportation system on the inland rivers.

With the use of interchangeable parts

Interchangeable parts

Interchangeable parts are parts that are, for practical purposes, identical. They are made to specifications that ensure that they are so nearly identical that they will fit into any device of the same type. One such part can freely replace another, without any custom fitting...

popularized by Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney was an American inventor best known for inventing the cotton gin. This was one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution and shaped the economy of the Antebellum South...

, the factory system

Factory system

The factory system was a method of manufacturing first adopted in England at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 1750s and later spread abroad. Fundamentally, each worker created a separate part of the total assembly of a product, thus increasing the efficiency of factories. Workers,...

began in which workers assembled at one location to produce goods. The early textile factories such as those in Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell Mill Girls

"Lowell Mill Girls" was the name used for female textile workers in Lowell, Massachusetts, in the 19th century. The Lowell textile mills employed a workforce which was about three quarters female; this characteristic caused two social effects: a close examination of the women's moral behavior, and...

employed mainly women, but generally factories were a male domain.

By 1860, 16% of Americans lived in cities with 2500 or more people; a third of the nation's income came from manufacturing. Urbanized industry was limited primarily to the Northeast; cotton cloth production was the leading industry, with the manufacture of shoes, woolen clothing, and machinery also expanding. Energy was provided in most cases by water power from the rivers, but steam engines were being introduced to factories as well. By 1860, the railroads had made a transition from use of local wood supplies to coal for their locomotives. Pennsylvania became the center of the coal industry. Many, if not most, of the factory workers and miners were recent immigrants from Europe, or their children. Throughout the North, and in southern cities, entrepreneurs were setting up factories, mines, mills, banks, stores, and other business operations. In the great majority of cases, these were relatively small, locally owned, and locally operated enterprises.

Immigration and labor

To fill the new factory jobs, immigrants poured into the United States in the first mass wave of immigration in the 1840s and 1850s. Known as the period of old immigration, this time saw 4.2 million immigrants come into the United States raising the overall population by 20 million people. Historians often describe this as a time of “push-pull” immigration. People who were “pushed” to the United States immigrated because of poor conditions back home that made survival dubious while immigrants who were “pulled” came from stable environments to find greater economic success. One group who was “pushed” to the United States was the Irish, who were attempting to escape the Great Famine in their nation. Settling around the coastal cities of Boston, Massachusetts and New York CityNew York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, the Irish were not initially welcomed because of their poverty and Roman Catholic beliefs. They lived in crowded, filthy neighborhoods and performed low-paying and physically demanding jobs. The Catholic Church was widely distrusted by many Americans as a symbol of European autocracy. German immigrations, on the other hand, were “pulled” to America to avoid a looming financial disaster in their nation. Unlike the Irish, the German immigrants often sold their possessions and arrived in America with money in hand. German immigrants were both Protestant and Catholic, although the latter did not face the discrimination that the Irish did. Many Germans settled in communities in the Midwest rather than on the coast. Major cities such as Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

and St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

developed large German populations. Unlike the Irish, most German immigrants were educated, middle-class people who mainly came to America for political rather than economic reasons. In the big cities such as New York, immigrants often lived in ethnic enclave

Ethnic enclave

An ethnic enclave is an ethnic community which retains some cultural distinction from a larger, surrounding area, it may be a neighborhood, an area or an administrative division based on ethnic groups. Sometimes an entire city may have such a feel. Usually the enclave revolves around businesses...

s called “ghettos” that were often impoverished and crime-ridden. The most infamous of these immigrant neighborhoods was the Five Points

Five Points, Manhattan

Five Points was a neighborhood in central lower Manhattan in New York City. The neighborhood was generally defined as being bound by Centre Street in the west, The Bowery in the east, Canal Street in the north and Park Row in the south...

in New York City. With increasing labor agitation for higher wages and better working conditions in places like Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell Mill Girls

"Lowell Mill Girls" was the name used for female textile workers in Lowell, Massachusetts, in the 19th century. The Lowell textile mills employed a workforce which was about three quarters female; this characteristic caused two social effects: a close examination of the women's moral behavior, and...

, many factory owners began to replace female workers with immigrants who would work cheaper and were less demanding about factory conditions.

Wilmot Proviso

In 1848 the acquisition of new territory from MexicoMexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is the peace treaty, largely dictated by the United States to the interim government of a militarily occupied Mexico City, that ended the Mexican-American War on February 2, 1848...

renewed the sectional debate that had gripped the nation during the admittance of Missouri. Congressmen either feared (if they were Northern) or hoped (if they were Southern) that slavery would be extended into the new territories. Soon after the war began, Democratic Congressman David Wilmot

David Wilmot

David Wilmot was a U.S. political figure. He was a sponsor and eponym of the Wilmot Proviso which aimed to ban slavery in land gained from Mexico in the Mexican-American War of 1846–1848. Wilmot was a Democrat, a Free Soiler, and a Republican during his political career...

proposed that territory won from Mexico should be free from the institution of slavery. His proposal was called the Wilmot Proviso

Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso, one of the major events leading to the Civil War, would have banned slavery in any territory to be acquired from Mexico in the Mexican War or in the future, including the area later known as the Mexican Cession, but which some proponents construed to also include the disputed...

and it never passed Congress and never became law. Northern Democrats were upset that Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States . Before his presidency, he was the eighth Vice President and the tenth Secretary of State, under Andrew Jackson ....

was not given the presidential nomination because he would not endorse the annexation of Texas. They were also fed up with Southern domination of the Democratic Party. Southerners were upset at the Proviso because they saw it as an attack upon their constitutional rights and their entire society.

The Popular Sovereignty Debate

With the failure of the Wilmot Proviso, Senator Lewis CassLewis Cass

Lewis Cass was an American military officer and politician. During his long political career, Cass served as a governor of the Michigan Territory, an American ambassador, a U.S. Senator representing Michigan, and co-founder as well as first Masonic Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Michigan...

introduced the idea of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty in the United States

The American Revolution marked a departure in the concept of popular sovereignty as it had been discussed and employed in the European historical context. With their Revolution, Americans substituted the sovereignty in the person of the English king, George III, with a collective sovereign—composed...

in Congress. In an attempt to hold the Congress together as it continued to divide along sectional, rather than party lines, Cass proposed that Congress did not have the power to determine whether territories could allow slavery since this was not an enumerated power listed in the Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

. Instead Cass proposed that the people living in the territories themselves should decide the slavery issue. For the Democrats, the solution was not as clear as it appeared. Northern Democrats called for "squatter sovereignty" in which the people living in the territory could decide the issue when a territorial legislature was convened. Southern Democrats disputed this idea arguing that the issue of slavery must be decided at the time of adoption of a state constitution when the request was made to Congress for admission as a state. Cass and other Democratic leaders failed to clarify the issue so that neither section of the country felt slighted as the election approached. After Cass' defeat in 1848, Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas assumed a leading role in the party and became closely associated with popular sovereignty with his proposal of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

California Gold Rush

The election of 1848United States presidential election, 1848

The United States presidential election of 1848 was an open race. President James K. Polk, having achieved all of his major objectives in one term and suffering from declining health that would take his life less than four months after leaving office, kept his promise not to seek re-election.The...

produced a new President from the Whig Party

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

, Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

. President Polk did not seek reelection because he gained all his objectives in his first term and because his health was declining. From the election emerged the Free Soil Party

Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived political party in the United States active in the 1848 and 1852 presidential elections, and in some state elections. It was a third party and a single-issue party that largely appealed to and drew its greatest strength from New York State. The party leadership...

, a group of anti-slavery Democrats who supported Wilmot's Proviso. The creation of the Free Soil Party foreshadowed the collapse of the Second party system

Second Party System

The Second Party System is a term of periodization used by historians and political scientists to name the political party system existing in the United States from about 1828 to 1854...

; the existing parties could not contain the debate over slavery for much longer.

The question of slavery became all the more urgent with the discovery of gold in California

California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The first to hear confirmed information of the gold rush were the people in Oregon, the Sandwich Islands , and Latin America, who were the first to start flocking to...

in 1848. The next year, there was a massive influx of prospectors and miners looking to strike it rich. Most migrants to California (so-called 'Forty-Niners') abandoned their jobs, homes, and families looking for gold. It also attracted some of the first Chinese Americans to the West Coast of the United States

West Coast of the United States

West Coast or Pacific Coast are terms for the westernmost coastal states of the United States. The term most often refers to the states of California, Oregon, and Washington. Although not part of the contiguous United States, Alaska and Hawaii do border the Pacific Ocean but can't be included in...

. Most Forty-Niners never found gold but instead settled in the urban center of San Francisco or in the new municipality of Sacramento

Sacramento

Sacramento is the capital of the state of California, in the United States of America.Sacramento may also refer to:- United States :*Sacramento County, California*Sacramento, Kentucky*Sacramento – San Joaquin River Delta...

.

Compromise of 1850

The influx of population led to California's application of statehood in 1850. This created a renewal of sectional tension because California's admission into the Union threatened to upset the balance of power in Congress. The imminent admission of Oregon, New MexicoNew Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

, and Utah

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

also threatened to upset the balance. Many Southerners also realized that the climate of those territories did not lend themselves to the extension of slavery. Debate raged in Congress until a resolution was found in 1850.

The Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

was brokered by Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician from the western state of Illinois, and was the Northern Democratic Party nominee for President in 1860. He lost to the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom he had defeated two years earlier in a Senate contest following a famed...

and supported by "The Great Compromiser," Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

. Through the compromise, California was admitted as a free state, Texas was financially compensated for the loss of its Western territories, the slave trade (not slavery) was abolished in the District of Columbia, the Fugitive Slave Law was passed as a concession to the South, and, most importantly, the New Mexico Territory

New Mexico Territory

thumb|right|240px|Proposed boundaries for State of New Mexico, 1850The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of...

(including modern day Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

and the Utah Territory

Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah....

) would determine its status (either free or slave) by popular vote

Popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty or the sovereignty of the people is the political principle that the legitimacy of the state is created and sustained by the will or consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. It is closely associated with Republicanism and the social contract...

. The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the divisive issue, but the peace was not to last long.

Abolitionism

The debate over slavery in the pre-Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

United States has several sides. Abolitionists grew directly out of the Second Great Awakening

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Christian revival movement during the early 19th century in the United States. The movement began around 1800, had begun to gain momentum by 1820, and was in decline by 1870. The Second Great Awakening expressed Arminian theology, by which every person could be...

and the European Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

and saw slavery as an affront to God and/or reason. Abolitionism had roots similar to the temperance movement

Temperance movement

A temperance movement is a social movement urging reduced use of alcoholic beverages. Temperance movements may criticize excessive alcohol use, promote complete abstinence , or pressure the government to enact anti-alcohol legislation or complete prohibition of alcohol.-Temperance movement by...

. The publishing of Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe was an American abolitionist and author. Her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was a depiction of life for African-Americans under slavery; it reached millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and United Kingdom...

's Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", according to Will Kaufman....

, in 1852, galvanized the abolitionist movement.

Peculiar institution

" peculiar institution" was a euphemism for slavery and the economic ramifications of it in the American South. The meaning of "peculiar" in this expression is "one's own", that is, referring to something distinctive to or characteristic of a particular place or people...

" ensured that elites controlled most of the land, property, and capital

Capital (economics)

In economics, capital, capital goods, or real capital refers to already-produced durable goods used in production of goods or services. The capital goods are not significantly consumed, though they may depreciate in the production process...

in the South. The Southern United States was, by this definition, undemocratic. To fight the "slave power conspiracy," the nation's democratic ideals had to be spread to the new territories and the South.

In the South, however, slavery was justified in many ways. The Nat Turner Uprising of 1831 had terrified Southern whites. Moreover, the expansion of "King Cotton

King Cotton

King Cotton was a slogan used by southerners to support secession from the United States by arguing cotton exports would make an independent Confederacy economically prosperous, and—more important—would force Great Britain and France to support the Confederacy because their industrial economy...

" into the Deep South

Deep South

The Deep South is a descriptive category of the cultural and geographic subregions in the American South. Historically, it is differentiated from the "Upper South" as being the states which were most dependent on plantation type agriculture during the pre-Civil War period...

further entrenched the institution into Southern society. John Calhoun's

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

treatise, The Pro-Slavery Argument, stated that slavery was not simply a necessary evil but a positive good. Slavery was a blessing to so-called African savages. It civilized them and provided them with the lifelong security that they needed. Under this argument, the pro-slavery proponents believed that the African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s were unable to take care of themselves because they were biologically inferior. Furthermore, white Southerners looked upon the North and Britain

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

as soulless industrial societies with little culture. Whereas the North was dirty, dangerous, industrial, fast-paced, and greedy, pro-slavery proponents believed that the South was civilized, stable, orderly, and moved at a 'human pace.'

According to the 1860 U.S. census

United States Census, 1860

The United States Census of 1860 was the eighth Census conducted in the United States. It determined the population of the United States to be 31,443,321 — an increase of 35.4 percent over the 23,191,875 persons enumerated during the 1850 Census...

, fewer than 385,000 individuals (i.e. 1.4% of whites in the country, or 4.8% of southern whites) owned one or more slaves. 95% of blacks lived in the South, comprising one-third of the population there as opposed to 1% of the population of the North

Northern United States

Northern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

With the admission of California as a state in 1851, the Pacific Coast had finally been reached. Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny was the 19th century American belief that the United States was destined to expand across the continent. It was used by Democrat-Republicans in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico; the concept was denounced by Whigs, and fell into disuse after the mid-19th century.Advocates of...

had brought Americans to the end of the continent. President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore was the 13th President of the United States and the last member of the Whig Party to hold the office of president...

hoped to continue Manifest Destiny, and with this aim he sent Commodore Matthew Perry to Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

in the hopes of arranging trade agreements in 1853.

A railroad to the Pacific was planned, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician from the western state of Illinois, and was the Northern Democratic Party nominee for President in 1860. He lost to the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom he had defeated two years earlier in a Senate contest following a famed...

wanted the transcontinental railway

First Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad was a railroad line built in the United States of America between 1863 and 1869 by the Central Pacific Railroad of California and the Union Pacific Railroad that connected its statutory Eastern terminus at Council Bluffs, Iowa/Omaha, Nebraska The First...

to pass through Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

. Southerners protested, insisting that it run through Texas, Southern California and end in New Orleans. Douglas decided to compromise and introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Kansas-Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opening new lands for settlement, and had the effect of repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by allowing settlers in those territories to determine through Popular Sovereignty if they would allow slavery within...

of 1854. In exchange for having the railway run through Chicago, he proposed 'organizing' (open for white settlement) the territories of Kansas and Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska is a state on the Great Plains of the Midwestern United States. The state's capital is Lincoln and its largest city is Omaha, on the Missouri River....

.

Douglas anticipated Southern opposition to the act and added in a provision that stated that the status of the new territories would be subject to popular sovereignty. In theory, the new states could become slave states under this condition. Under Southern pressure, Douglas added a clause which explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise. President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce was the 14th President of the United States and is the only President from New Hampshire. Pierce was a Democrat and a "doughface" who served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Pierce took part in the Mexican-American War and became a brigadier general in the Army...

supported the bill as did the South and a fraction of northern Democrats.

The act split the Whigs. Northern Whigs generally opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act while Southern Whigs supported it. Most Northern Whigs joined the new Republican Party

History of the United States Republican Party

The United States Republican Party is the second oldest currently existing political party in the United States after its great rival, the Democratic Party. It emerged in 1854 to combat the Kansas Nebraska Act which threatened to extend slavery into the territories, and to promote more vigorous...

. Some joined the Know-Nothing Party which refused to take a stance on slavery. Southern Whigs and northern Democrats were emerged in 1850 and most of Southern Whigs joined the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

.

Bleeding Kansas

With the opening of Kansas, settlers rushed into the new territory. Both pro- and anti-slavery supporters rushed to settle in the new territory. Violent clashes soon erupted between them. Abolitionists from New EnglandNew England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

settled in Topeka, Lawrence

Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is the sixth largest city in the U.S. State of Kansas and the county seat of Douglas County. Located in northeastern Kansas, Lawrence is the anchor city of the Lawrence, Kansas, Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Douglas County...

, and Manhattan

Manhattan, Kansas

Manhattan is a city located in the northeastern part of the state of Kansas in the United States, at the junction of the Kansas River and Big Blue River. It is the county seat of Riley County and the city extends into Pottawatomie County. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 52,281...

. Pro-slavery advocates, mainly from Missouri, settled in Leavenworth

Leavenworth, Kansas

Leavenworth is the largest city and county seat of Leavenworth County, in the U.S. state of Kansas and within the Kansas City, Missouri Metropolitan Area. Located in the northeast portion of the state, it is on the west bank of the Missouri River. As of the 2010 census, the city population was...

and Lecompton

Lecompton, Kansas

Lecompton is a city in Douglas County, Kansas, United States. It is part of the Lawrence, Kansas Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 608 at the 2000 census. Lecompton played a major historical role in pre-Civil War America as the Territorial capital of Kansas from 1855 to 1861...

.

In 1855, elections were held for the territorial legislature. While there were only 1,500 legal voters, migrants from Missouri swelled the population to over 6,000. The result was that a pro-slavery majority was elected to the legislature. Free-soilers were so outraged that they set up their own delegates in Topeka. A group of anti-slavery Missourians sacked Lawrence on May 21, 1856. Violence continued for two more years until the promulgation of the Lecompton Constitution

Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas . The document was written in response to the anti-slavery position of the 1855 Topeka Constitution of James H. Lane and other free-state advocates...

.

The violence, known as "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas or the Border War, was a series of violent events, involving anti-slavery Free-Staters and pro-slavery "Border Ruffian" elements, that took place in the Kansas Territory and the western frontier towns of the U.S. state of Missouri roughly between 1854 and 1858...

," scandalized the Democratic administration and began a more heated sectional conflict. Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner was an American politician and senator from Massachusetts. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction,...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

gave a speech in the Senate entitled "The Crime Against Kansas." The speech was a scathing criticism of the South and the "peculiar institution

Peculiar institution

" peculiar institution" was a euphemism for slavery and the economic ramifications of it in the American South. The meaning of "peculiar" in this expression is "one's own", that is, referring to something distinctive to or characteristic of a particular place or people...

." As an example of rising sectional tensions, days after delivering the speech, South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

Representative Preston Brooks

Preston Brooks

Preston Smith Brooks was a Democratic Congressman from South Carolina. Brooks is primarily remembered for his severe beating of Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the United States Senate with a gutta-percha cane, delivered in response to an anti-slavery speech in which Sumner compared Brooks'...

approached Sumner during a recess of the Senate and caned

Caning

Caning is a form of corporal punishment consisting of a number of hits with a single cane usually made of rattan, generally applied to the offender's bare or clothed buttocks or hand . Application of a cane to the knuckles or the shoulders has been much less common...

him.

Election of 1856

President Pierce was too closely associated with "Bleeding Kansas" and was thus not renominated under the Democratic ticket. Instead, Democrats nominated James BuchananJames Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

as their presidential candidate. They campaigned heavily in the South. They warned that the Republicans were extremists and were promoting civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

.

The Know Nothing

Know Nothing

The Know Nothing was a movement by the nativist American political faction of the 1840s and 1850s. It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by German and Irish Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to Anglo-Saxon Protestant values and controlled by...

Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore, who campaigned on a platform that mainly concerned immigration

Immigration

Immigration is the act of foreigners passing or coming into a country for the purpose of permanent residence...

.

The Republicans nominated John Frémont under the slogan of "Free soil, free labor, free speech, free men, Frémont." Frémont won most of the North and nearly won the election. A slight shift of votes in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

and Illinois would have resulted in a Republican victory. As a result, they completely abandoned the South and became a predominantly Northern party. The Democrats won the election but increasingly became a Southern party. Thus, the country was now polarized along North-South sectional lines, with the Republicans being the party of the North and the Democrats, the South. This began the Third Party System

Third Party System

The Third Party System is a term of periodization used by historians and political scientists to describe a period in American political history from about 1854 to the mid-1890s that featured profound developments in issues of nationalism, modernization, and race...

which lasted until 1896.

Immediately following Buchanan's inauguration, there was a sudden depression, known as the Panic of 1857

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Indeed, because of the interconnectedness of the world economy by the time of the 1850s, the financial crisis which began in the autumn of 1857 was...

, which weakened the credibility of the Democratic Party further. In the spring of 1857, President Buchanan launched a military expedition to the Utah Territory

Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah....

that resulted in the Utah War

Utah War

The Utah War, also known as the Utah Expedition, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between LDS settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the United States government. The confrontation lasted from May 1857 until July 1858...

(also known as Buchanan's Blunder) of 1857-1858.

Dred Scott decision

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court became involved in the crisis. Dred ScottDred Scott

Dred Scott , was an African-American slave in the United States who unsuccessfully sued for his freedom and that of his wife and their two daughters in the Dred Scott v...

, a black slave, was taken by his master (Dr. John Emerson) in 1834 from Missouri, a slave state, to Illinois, a free state because of the Northwest Ordinance

Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance was an act of the Congress of the Confederation of the United States, passed July 13, 1787...

. Scott was then taken to what later became Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

in 1838. They moved back to St. Louis

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

in 1846 where his owner died. Dred Scott then sued Emerson's wife for his freedom claiming that living in a non-slave territory made him a free man. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court where Chief Justice Taney declared that Dred Scott was a slave, not a citizen and thus had no rights under the Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

. His ruling was significant because the Supreme Court had decided that slaves were not citizens of the United States and that no black could ever become a citizen since they were "beings of an inferior order," and "less-capable." It also stated that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional because of the Fifth Amendment

Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights, protects against abuse of government authority in a legal procedure. Its guarantees stem from English common law which traces back to the Magna Carta in 1215...

. The Missouri Compromise unlawfully took away property without due process. Thus, Dred Scott was not free. Scott was bought by the sons of his first owner and freed, but he died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

a year later on September 17, 1858.

The decision strengthened Northern opposition to slavery. On October 13, Minnesota ratified its constitution which outlawed slavery. Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

also made it a penal offense to own or claim slaves. Politically, it was trivial since the Kansas-Nebraska Act had already nullified the Missouri Compromise; symbolically, however, the Supreme Court had sanctioned the hardline Southern view. This emboldened Southerners and convinced Northerners that there was a vast "slave power conspiracy" to control the Federal government.

Lincoln-Douglas debates

The seven famous Lincoln-Douglas debates were held for the Senatorial election in Illinois between incumbent Stephen A. DouglasStephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician from the western state of Illinois, and was the Northern Democratic Party nominee for President in 1860. He lost to the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, whom he had defeated two years earlier in a Senate contest following a famed...

and Abraham Lincoln, whose political experience was limited to a single term in Congress that had been mainly notable for his opposition to the Mexican War. The debates are remembered for their relevance and eloquence.

Lincoln was opposed to the extension of slavery into any new territories. Douglas, however, believed that the people should decide the future of slavery in their own territories. This was known as popular sovereignty. Lincoln, however, argued that popular sovereignty was pro-slavery since it was inconsistent with the Dred Scott Decision. Lincoln said that Chief Justice Roger Taney was the first person who said that the Declaration of Independence

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

did not apply to blacks and that Douglas was the second. In response, Douglas came up with what is known as the Freeport Doctrine

Freeport Doctrine

The Freeport Doctrine was articulated by Stephen A. Douglas at the second of the Lincoln-Douglas debates on August 27, 1858, in Freeport, Illinois. Lincoln tried to force Douglas to choose between the principle of popular sovereignty proposed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the majority decision of...

. Douglas stated that while slavery may have been legally possible, the people of the state could refuse to pass laws favourable to slavery.

In his famous "House Divided Speech

Lincoln's House Divided Speech

The House Divided Speech was an address given by Abraham Lincoln on June 16, 1858, in Springfield, Illinois, upon accepting the Illinois Republican Party's nomination as that state's United States senator. The speech became the launching point for his unsuccessful campaign for the Senate seat...

" in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the third and current capital of the US state of Illinois and the county seat of Sangamon County with a population of 117,400 , making it the sixth most populated city in the state and the second most populated Illinois city outside of the Chicago Metropolitan Area...

, Lincoln stated:

- "A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved. I do not expect the house to fall, but I do expect that it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest further the spread of it and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.

During the debates, Lincoln argued that his speech was not abolitionist, writing at the Charleston

Charleston, Illinois

Charleston is a city in and the county seat of Coles County, Illinois, United States. The population was 21,838 as of the 2010 census. The city is home to Eastern Illinois University and has close ties with its neighbor Mattoon, Illinois...

debate that:

- I am not in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office.

The debates attracted thousands of spectators and featured parades and demonstrations. Lincoln ultimately lost the election but vowed:

- The fight must go on. The cause of civil liberty must not be surrendered at the end of one or even 100 defeats.

John Brown's raid

The debate took a new, violent turn with the actions of an abolitionist from ConnecticutConnecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

. John Brown

John Brown (abolitionist)

John Brown was an American revolutionary abolitionist, who in the 1850s advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to abolish slavery in the United States. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre during which five men were killed, in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas, and made his name in the...

was a militant abolitionist who advocated guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

to combat pro-slavery advocates. Receiving arms and financial aid from a group of prominent Massachusetts business and social leaders known collectively as the Secret Six

Secret Six

The Secret Six, or the Secret Committee of Six, were six wealthy and influential men who secretly funded the American abolitionist, John Brown. They were Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Gridley Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, and George Luther Stearns...

, Brown participated in the violence of Bleeding Kansas and directed the Pottawatomie Massacre

Pottawatomie Massacre

The Pottawatomie Massacre occurred during the night of May 24 and the morning of May 25, 1856. In reaction to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces, John Brown and a band of abolitionist settlers killed five settlers north of Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas...

on May 24, 1856, in response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas. In 1859, Brown went to Virginia to liberate slaves. On October 17, Brown seized the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to arm slaves in the surrounding area, creating a slave army to sweep through the South, attacking slaveowners and liberating slaves. Local slaves did not rise up to support Brown. He killed five civilians and took hostages. He also stole a sword that Frederick the Great had given George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

. He was captured by an armed military force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

. He was tried for treason to the Commonwealth of Virginia and hanged on December 2, 1859. On his way to the gallows, Brown handed a jailkeeper a note, chilling in its prophecy, predicting that the "sin" of slavery would never be cleansed from the United States without bloodshed.

The raid on Harper's Ferry

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. In many books the town is called "Harper's Ferry" with an apostrophe....

horrified Southerners who saw Brown as a criminal, and they became increasingly distrustful of Northern abolitionists who celebrated Brown as a hero and a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

.

Election of 1860

The Democratic National ConventionDemocratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 national convention...

for the Election of 1860 was held in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

, despite it usually being held in the North. When the convention endorsed the doctrine of popular sovereignty, 50 Southern delegates walked out. The inability to come to a decision on who should be nominated led to a second meeting in Baltimore, Maryland. At Baltimore, 110 Southern delegates, led by the so-called "fire eaters," walked out of the convention when it would not adopt a platform that endorsed the extension of slavery into the new territories. The remaining Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas for the presidency. The Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the American South. In the 19th century, they were the definitive pro-slavery wing of the party, opposed to both the anti-slavery Republicans and the more liberal Northern Democrats.Eventually "Redemption" was finalized in...

held a convention in Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

, and nominated John Breckinridge

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

. Both claimed to be the true voice of the Democratic Party.

Former Know Nothings and some Whigs formed the Constitutional Union Party

Constitutional Union Party (United States)

The Constitutional Union Party was a political party in the United States created in 1860. It was made up of conservative former Whigs who wanted to avoid disunion over the slavery issue...

which ran on a platform based around supporting only the Constitution and the laws of the land.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

won the support of the Republican National Convention

Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention is the presidential nominating convention of the Republican Party of the United States. Convened by the Republican National Committee, the stated purpose of the convocation is to nominate an official candidate in an upcoming U.S...

after it became apparent that William Seward

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward, Sr. was the 12th Governor of New York, United States Senator and the United States Secretary of State under Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson...

had alienated certain branches of the Republican Party. Moreover, Lincoln had been made famous in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and was well known for his eloquence and his moderate position on slavery.

Lincoln won a majority of votes in the electoral college

Electoral college

An electoral college is a set of electors who are selected to elect a candidate to a particular office. Often these represent different organizations or entities, with each organization or entity represented by a particular number of electors or with votes weighted in a particular way...

, but only won two-fifths of the popular vote. The Democratic vote was split three ways and Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

.

Secession

Lincoln's election in November led to a declaration of secessionSecession in the United States

Secession in the United States can refer to secession of a state from the United States, secession of part of a state from that state to form a new state, or secession of an area from a city or county....

by South Carolina on December 20, 1860. Before Lincoln took office in March 1861, six other states had declared their secession from the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

: Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

, (January 9, 1861), Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

(January 10), Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

(January 11), Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

, (January 19), Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

(January 26), and Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

(February 1).

Men from both North and South met in Virginia to try to hold together the Union, but the proposals for amending the Constitution were unsuccessful. In February 1861, the seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital of the U.S. state of Alabama, and is the county seat of Montgomery County. It is located on the Alabama River southeast of the center of the state, in the Gulf Coastal Plain. As of the 2010 census, Montgomery had a population of 205,764 making it the second-largest city...

, and formed a new government: the Confederate States of America

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

. The first Confederate Congress was held on February 4, 1861, and adopted a provisional constitution. On February 8, 1861, Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis , also known as Jeff Davis, was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President for its entire history. He was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane Davis...

was nominated President of the Confederate States.

Civil War

.png)

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a Third System masonry coastal fortification located in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The fort is best known as the site upon which the shots initiating the American Civil War were fired, at the Battle of Fort Sumter.- Construction :...

, the federal base in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, the new Confederate government under President Jefferson Davis ordered General P.G.T. Beauregard to open fire on the fort

Battle of Fort Sumter

The Battle of Fort Sumter was the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter, near Charleston, South Carolina, that started the American Civil War. Following declarations of secession by seven Southern states, South Carolina demanded that the U.S. Army abandon its facilities in Charleston Harbor. On...

. It fell two days later, without casualty, spreading the flames of war across America. immediately, rallies were held in every town and city, north and south, demanding war. Lincoln called for troops to retake lost federal property, which meant an invasion of the South. In response, four more states seceded: Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

(April 17, 1861), Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

, (May 6, 1861), Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

(May 7, 1861), and North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

(May 20, 1861). The four remaining slave states, Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

, Delaware

Delaware

Delaware is a U.S. state located on the Atlantic Coast in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is bordered to the south and west by Maryland, and to the north by Pennsylvania...

, Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

, and Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, under heavy pressure from the Federal government did not secede; Kentucky tried, and failed, to remain neutral.

Each side had its relative strengths and weaknesses. The North had a larger population and a far larger industrial base and transportation system. It would be a defensive war for the South and an offensive one for the North, and the South could count on its huge geography, and an unhealthy climate, to prevent an invasion. In order for the North to emerge victorious, it would have to conquer and occupy the Confederate States of America. The South, on the other hand, only had to keep the North at bay until the Northern public lost the will to fight. The Confederacy adopted a military strategy designed to hold their territory together, gain worldwide recognition, and inflict so much punishment on invaders that the North would grow weary of the war and negotiate a peace treaty that would recognize the independence of the CSA. The only point of seizing Washington, or invading the North (besides plunder) was to shock Yankees into realizing they could not win. The Confederacy moved its capital from a safe location in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital of the U.S. state of Alabama, and is the county seat of Montgomery County. It is located on the Alabama River southeast of the center of the state, in the Gulf Coastal Plain. As of the 2010 census, Montgomery had a population of 205,764 making it the second-largest city...

, to the more cosmopolitan city of Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

, only 100 miles from the enemy capital in Washington. Richmond was heavily exposed, and at the end of a long supply line; much of the Confederacy's manpower was dedicated to its defense. The North had far greater potential advantages, but it would take a year or two to mobilize them or warfare. Meanwhile, everyone expected a short war.

War in the East

The Union assembled an army of 35,000 men (the largest ever seen in North America up to that point) under the command of General Irvin McDowell. With great fanfare, the green and extremely untrained soldiers set out from Washington DC with the idea that they would capture Richmond in six weeks and put a quick end to the conflict. At the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, however, disaster ensued as McDowell's army was completely routed and fled back to the nation's capitol. Major General George McClellanGeorge B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

of the Union was put in command of the Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

following the battle on July 26, 1861. He began to reconstruct the shattered army and turn it into a real fighting force, as it became clear that there would be no quick, six-week resolution of the conflict. Despite pressure from the White House, McClellan did not move until March 1862, when the Peninsular Campaign began with the purpose of capturing the capitol of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

. It was initially successful, but in the final days of the campaign, McClellan faced strong opposition from Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

, the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, as well as the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed against the Union Army of the Potomac...

. From June 25 to July 1, in a series of battles known as the Seven Days Battles

Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles was a series of six major battles over the seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from...

, Lee forced the Army of the Potomac to retreat. McClellan was recalled to Washington and a new army assembled under the command of John Pope.

In August, Lee fought the Second Battle of Bull Run

Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive campaign waged by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia against Union Maj. Gen...

(Second Manassas) and defeated John Pope's Army of Virginia

Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Robert E...

. Pope was dismissed from command and his army merged with McClellan's. The Confederates then invaded Maryland, hoping to obtain European recognition and an end to the war. The two armies met at Antietam on September 17. This was the single bloodiest day in American history. The Union victory allowed Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

, which declared that all slaves in states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863 were freed. This did not actually end slavery, but it served to give a meaningful cause to the war and prevented any possibility of European intervention.