January Uprising

Encyclopedia

The January Uprising (Polish

: powstanie styczniowe, Lithuanian

: 1863 m. sukilimas, Belarusian

: Паўстанне 1863-1864 гадоў) was an uprising in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

(present-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, parts of Ukraine, western Russia) against the Russian Empire

. It began January 22, 1863, and lasted until the last insurgent

s were captured in 1865.

The uprising began as a spontaneous protest by young Poles against conscription

into the Imperial Russian Army

, and was soon joined by high-ranking Polish-Lithuanian officers and various politicians. The insurrectionists, severely outnumbered and lacking serious outside support, were forced to resort to guerrilla warfare

tactics. They failed to win any major military victories or capture any major cities or fortresses, but they did blunt the effect of the Tsar's abolition of serfdom in the Russian partition, which had been designed to draw the support of peasants away from the nation. Severe reprisals against insurgents, such as public executions and deportation

s to Siberia

, led many people to abandon armed struggle and turn instead to the idea of "organic work

": economic and cultural self-improvement.

After the Russian Empire lost the Crimean war

After the Russian Empire lost the Crimean war

and was weakened economically and politically, an unrest started in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

. In Vilnius

alone 116 demonstrations were held in 1861. In August 1861, manifestations in Vilnius ended in clashes with the Imperial Russian Army

. In spite of Russian police and Cossack interference, a symbolic meeting of hymn-singing Poles and Lithuanians took place on the bridge across Niemen River. Another mass gathering took place in Horodło, where Union of Horodło has been signed in 1413. The crowds sang Boże, coś Polskę (God protect Poland) in Lithuanian and Belarussian. In the autumn of 1861 Russians had introduced a state of emergency in Vilna Governorate

, Kovno Governorate

and Grodno Governorate

.

After series of patriotic riots, the Russian Namestnik of Tsar Alexander II

, General Karl Lambert

, introduced martial law

in Poland on 14 October 1861. Public gatherings were banned and some public leaders made outlaws.

The future leaders of the uprising gathered secretly in St. Petersburg, Warsaw

, Vilnius, Paris and London. After this series of meetings two major factions emerged. The Reds

united peasants, workers and some clergy while The Whites

represented liberal minded landlords and intelligentsia of the time. In 1862 two initiative groups were formed for the two components of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The uprising broke out at a moment when general quiet prevailed in Europe, and though there was a public outcry in support of the Poles, powers such as France, Britain and Austria were unwilling to disturb the calm. The potential revolutionary leaders did not have sufficient means to arm and equip the groups of young men who were hiding in forests to escape Alexander Wielopolski's order of conscription into the Russian army. Altogether about 10,000 men rallied around the revolutionary banner; they were recruited chiefly from the ranks of the city working classes and minor clerks, although there was also a considerable admixture of the younger sons of the poor szlachta

The uprising broke out at a moment when general quiet prevailed in Europe, and though there was a public outcry in support of the Poles, powers such as France, Britain and Austria were unwilling to disturb the calm. The potential revolutionary leaders did not have sufficient means to arm and equip the groups of young men who were hiding in forests to escape Alexander Wielopolski's order of conscription into the Russian army. Altogether about 10,000 men rallied around the revolutionary banner; they were recruited chiefly from the ranks of the city working classes and minor clerks, although there was also a considerable admixture of the younger sons of the poor szlachta

and a number of priests of lower rank.

To deal with these ill-armed units the Russian government had at its disposal an army of 90,000 men under General Ramsay in Poland. It looked as if the rebellion would be crushed quickly. The die was cast, however, and the provisional government applied itself to the great task with fervor. It issued a manifesto in which it pronounced "all sons of Poland

free and equal citizens without distinction of creed, condition and rank." It declared that land cultivated by the peasants, whether on the basis of rent-pay or service, henceforth should become their unconditional property, and compensation for it would be given to the landlords out of the general funds of the State. The revolutionary government did its very best to supply and provision the unarmed and scattered guerrillas who, during the month of February, met the Russians in eighty bloody encounters. Meanwhile, it issued an appeal to the nations of western Europe, which was received everywhere with a genuine and heartfelt response, from Norway to Portugal. Pope Pius IX ordered a special prayer for the success of the Catholic Polish in their defence against the Orthodox Russians, and was very active in arousing sympathy for the Polish rebels.

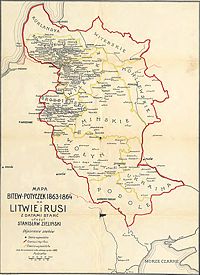

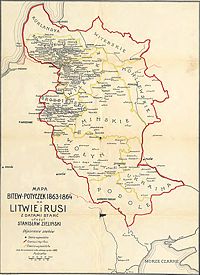

In Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, northern Ukraine and western Russia the uprising started on February 1, 1863. A coalition government of the Reds and the Whites was formed. It was led by Zygmunt Sierakowski, Antanas Mackevičius

In Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, northern Ukraine and western Russia the uprising started on February 1, 1863. A coalition government of the Reds and the Whites was formed. It was led by Zygmunt Sierakowski, Antanas Mackevičius

and Konstanty Kalinowski

. They fully supported their counterparts in Poland and adhered to the same policy.

Polish, Lithuanian and Belarusian insurgents were more numerous (up to 30,000 men at the peak of uprising) and a little better armed, but there were 135,000 Russian troops and 6,000 Cossacks in Lithuania and another 45,000 Russian troops in Volhynia

. In every major military engagement of the uprising insurgents were outnumbered at least 10 to 1.

During the first 24 hours of the uprising armories across the country were looted, many Russian officials executed on sight. February 2, 1863, saw the start of the first major military engagement of the uprising between Polish peasants (mostly armed with scythe) and a squadron of Russian hussars near Čysta Būda, near Marijampolė

. It ended with a massacre of the unprepared peasants. As hope of a short war was present, insurgent groups merged into bigger formations and recruited new personnel.

On April 7 Zygmunt Sierakowski, who was able to recruit and arm 2500 men for the cause, was elected to be the military commander in chief of the reborn PLC. Under his command the peasant army was able to achieve several difficult victories near Raguva

on April 21, Biržai

on May 2, Medeikiai on May 7. However, tired from a several week long marches and combat, the insurgent army suffered a defeat on May 8 near Gudiškis.

The provisional government counted on a revolutionary outbreak in Russia, where the discontent with the autocratic regime seemed at the time to be widely prevalent. It also counted on the active support of Napoleon III, particularly after Prussia

The provisional government counted on a revolutionary outbreak in Russia, where the discontent with the autocratic regime seemed at the time to be widely prevalent. It also counted on the active support of Napoleon III, particularly after Prussia

, foreseeing an inevitable armed conflict with France, made friendly overtures to Russia in the Alvensleben Convention

and offered assistance in suppressing the Polish uprising. On the 14th day of February arrangements had already been completed, and the British Ambassador in Berlin was able to inform his government that a Prussian military envoy "has concluded a military convention with the Russian Government, according to which the two governments will reciprocally afford facilities to each other for the suppression of the insurrectionary movements which have lately taken place in Poland and Lithuania. The Prussian railways are also to be placed at the disposal of the Russian military authorities for the transportation of troops through Prussian territory from one part of the former Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth to another." This step of Bismarck's led to protests on the part of several governments and roused the nations of the Commonwealth. The result was the transformation of the insignificant uprising into another national war against Russia. Encouraged by the promises made by Napoleon III, all nations, acting upon the advice of Władysław Czartoryski, the son of Prince Adam, took to arms. Indicating their solidarity all Commonwealth citizens holding office under the Russian Government, including the Archbishop of Warsaw, resigned their positions and submitted to the newly constituted Government, which was composed of five most prominent representatives of the Whites.

The diplomatic intervention of the Powers in behalf of Poland, not sustained, except in the case of Sweden

, by a real determination on their part to do something effective for her, did more harm than good to the Polish cause. It alienated Austria which hitherto had maintained a friendly neutrality with reference to Poland and had not interfered with the Polish activities in Galicia. It prejudiced public opinion among the radical groups in Russia who, until that time, had been friendly because they regarded the uprising as of a social rather than a national character and it stirred the Russian Government to more energetic endeavors toward the speedy suppression of hostilities which were growing in strength and determination.

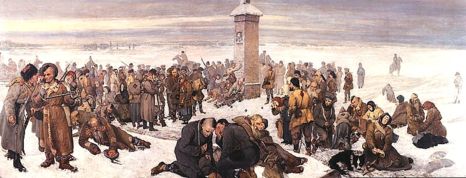

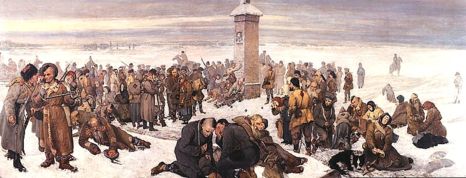

In addition to the thousands who fell in battle, 128 men were hanged personally by Mikhail Muravyov

('Muravyov the Hangman'), and 9,423 men and women were exiled to Siberia (2,500 men according to very lowered Russian data, Norman Davies

gives the number of 80,000 noting it was the single largest deportation in Russian history). Whole villages and towns were burned down; all activities were suspended and the szlachta

was ruined by confiscation and exorbitant taxes. Such was the brutality of the Russian troops that their actions were condemned throughout Europe

, and even in Russia itself Muravyov became ostracized. Count Fyodor Berg, the newly appointed Namestnik of Poland, followed in Muravyov's footsteps, employing inhumanly harsh measures against the country. The Reds criticized the Conservative government for its reactionary policy with reference to the peasants but, deluded in its hopes by Napoleon III, the Government counted on French support and persisted in its tactics. It was only after the highly respected and wise Romuald Traugutt took matters in hand that the aspect of the situation became brighter.

He reverted to the policy of the first provisional government and endeavored to bring the peasant masses into active participation by granting to them the land they worked and calling upon all classes to rise. The response was generous but not universal. The wise policy was adopted too late. The Russian Government had already been working among the peasants in the manner above described and giving to them liberal parcels of land for the mere asking. They were completely satisfied, and though not interfering with the revolutionaries to any great extent, became lukewarm to them. Fighting continued intermittently for several months. Among the generals Count Józef Hauke-Bosak

distinguished himself most as a commander of the revolutionary forces and took several cities from the vastly superior Russian army. When Romuald Traugutt

and the four other members of the Polish Government were apprehended by Russian troops and executed at the Warsaw citadel, the war in the course of which six hundred and fifty battles and skirmishes were fought and twenty-five thousand Poles killed, came to a speedy end in the latter half of 1864, having lasted for eighteen months. It is of interest to note that it persisted in Samogitia

and Podlaskie, where the Greek-Catholic population, outraged and persecuted for their religious convictions, clung longest to the revolutionary banner.

The uprising was finally crushed by Russia in 1864.

After the collapse of the uprising, harsh reprisals followed. According to Russian official information, 396 persons were executed and 18,672 were exiled to Siberia. Large numbers of men and women were sent to the interior of Russia and to Caucasus

, Urals

and other sections. Altogether about 70,000 persons were imprisoned and subsequently taken out of Poland and stationed in the remote regions of Russia.

The government confiscated 1,660 estates in Poland and 1,794 in Lithuania. A 10% income tax was imposed on all estates as a war indemnity. Only in 1869 was this tax reduced to 5% on all incomes. Serfdom was abolished in Russian Poland on February 19th 1864. It was deliberately enacted in a way that would ruin the szlachta. It was the only area where peasants paid the market price in redemption for the land (the average for the empire was 34% above the market price). All land taken from Polish peasants since 1846 was to be returned without redemption payments. The ex-serfs could only sell land to other peasants, not szlachta. 90% of the ex serfs in the empire who actually gained land after 1861 were in the 8 western provinces. Along with Romania, Polish landless or domestic serfs were the only ones to be given land after serfdom was abolished.[9] All this was to punish the szlachta's role in the uprisings of 1830 and 1863. Besides the land granted to the peasants, the Russian Government gave them additional forest, pasture and other privileges (known under the name of servitutes) which proved to be a source of incessant irritation between the landowners and peasants in the following decades, and an impediment to economic development. The government took over all the church estates and funds, and abolished monasteries and convents. With the exception of religious instruction, all other studies in the schools were ordered to be in Russian

. Russian also became the official language of the country, used exclusively in all offices of the general and local government. All traces of the former Polish autonomy were removed and the kingdom was divided into ten provinces, each with an appointed Russian military governor and all under complete control of the Governor-General at Warsaw. All the former government functionaries were deprived of their positions.

This measures proved to be of limited success. In 1905, 41 years after Russian crushing of the uprising, the next generation of Poles rose once again in a new one.

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

: powstanie styczniowe, Lithuanian

Lithuanian language

Lithuanian is the official state language of Lithuania and is recognized as one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.96 million native Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania and about 170,000 abroad. Lithuanian is a Baltic language, closely related to Latvian, although they...

: 1863 m. sukilimas, Belarusian

Belarusian language

The Belarusian language , sometimes referred to as White Russian or White Ruthenian, is the language of the Belarusian people...

: Паўстанне 1863-1864 гадоў) was an uprising in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

(present-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, parts of Ukraine, western Russia) against the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. It began January 22, 1863, and lasted until the last insurgent

Insurgency

An insurgency is an armed rebellion against a constituted authority when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents...

s were captured in 1865.

The uprising began as a spontaneous protest by young Poles against conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

into the Imperial Russian Army

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army was the land armed force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian army consisted of around 938,731 regular soldiers and 245,850 irregulars . Until the time of military reform of Dmitry Milyutin in...

, and was soon joined by high-ranking Polish-Lithuanian officers and various politicians. The insurrectionists, severely outnumbered and lacking serious outside support, were forced to resort to guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

tactics. They failed to win any major military victories or capture any major cities or fortresses, but they did blunt the effect of the Tsar's abolition of serfdom in the Russian partition, which had been designed to draw the support of peasants away from the nation. Severe reprisals against insurgents, such as public executions and deportation

Deportation

Deportation means the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. Today it often refers to the expulsion of foreign nationals whereas the expulsion of nationals is called banishment, exile, or penal transportation...

s to Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

, led many people to abandon armed struggle and turn instead to the idea of "organic work

Organic work

Organic work is a term coined by 19th century Polish positivists, denoting an ideology demanding that the vital powers of the nation be spent on labour rather than fruitless national uprisings. The basic principles of the organic work included education of the masses and increase of the economical...

": economic and cultural self-improvement.

Eve of the uprising

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

and was weakened economically and politically, an unrest started in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

. In Vilnius

Vilnius

Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania, and its largest city, with a population of 560,190 as of 2010. It is the seat of the Vilnius city municipality and of the Vilnius district municipality. It is also the capital of Vilnius County...

alone 116 demonstrations were held in 1861. In August 1861, manifestations in Vilnius ended in clashes with the Imperial Russian Army

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army was the land armed force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian army consisted of around 938,731 regular soldiers and 245,850 irregulars . Until the time of military reform of Dmitry Milyutin in...

. In spite of Russian police and Cossack interference, a symbolic meeting of hymn-singing Poles and Lithuanians took place on the bridge across Niemen River. Another mass gathering took place in Horodło, where Union of Horodło has been signed in 1413. The crowds sang Boże, coś Polskę (God protect Poland) in Lithuanian and Belarussian. In the autumn of 1861 Russians had introduced a state of emergency in Vilna Governorate

Vilna Governorate

The Vilna Governorate or Government of Vilna was a governorate of the Russian Empire created after the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795...

, Kovno Governorate

Kovno Governorate

The Kovno Governorate or Government of Kovno was a governorate of the Russian Empire. Its capital was Kovno . It was formed on 18 December 1842 by tsar Nicholas I from the western part of the Vilna Governorate, and the order was carried out on 1 July 1843. It used to be a part of Northwestern Krai...

and Grodno Governorate

Grodno Governorate

The Grodno Governorate, was a governorate of the Russian Empire.-Overview:Grodno: a western province or government of Europe lying between 52 and 54 N lat 23 and E long and bounded N by Vilna E by Minsk S Volhynia and W by the former kingdom of Poland The country was a wide plain in parts very...

.

After series of patriotic riots, the Russian Namestnik of Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II , also known as Alexander the Liberator was the Emperor of the Russian Empire from 3 March 1855 until his assassination in 1881...

, General Karl Lambert

Karl Lambert

Karl Karlovich count Lambert – Russian General of Cavalry, Namestnik of the Kingdom of Poland from August to October 1861.From 1840 to 1844 he fought against Chechen highlanders during Caucasian War...

, introduced martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

in Poland on 14 October 1861. Public gatherings were banned and some public leaders made outlaws.

The future leaders of the uprising gathered secretly in St. Petersburg, Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, Vilnius, Paris and London. After this series of meetings two major factions emerged. The Reds

Reds (January Uprising)

The "Reds" were a faction of the Polish insurrectionists during the January Uprising in 1863. They were radical democratic activists who supported the outbreak of the uprising from the outset, advocated an end to serfdom in Congress and future independent Poland, without compensation to the...

united peasants, workers and some clergy while The Whites

Whites (January Uprising)

The "Whites" were a faction among Polish insurrectionists before and during the January Uprising in early 1860s. They consisted mostly of progressive minded land owners and industrialists, the middle class and some intellectuals of Russian controlled Congress Poland...

represented liberal minded landlords and intelligentsia of the time. In 1862 two initiative groups were formed for the two components of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Uprising in the former Polish Kingdom

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

and a number of priests of lower rank.

To deal with these ill-armed units the Russian government had at its disposal an army of 90,000 men under General Ramsay in Poland. It looked as if the rebellion would be crushed quickly. The die was cast, however, and the provisional government applied itself to the great task with fervor. It issued a manifesto in which it pronounced "all sons of Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

free and equal citizens without distinction of creed, condition and rank." It declared that land cultivated by the peasants, whether on the basis of rent-pay or service, henceforth should become their unconditional property, and compensation for it would be given to the landlords out of the general funds of the State. The revolutionary government did its very best to supply and provision the unarmed and scattered guerrillas who, during the month of February, met the Russians in eighty bloody encounters. Meanwhile, it issued an appeal to the nations of western Europe, which was received everywhere with a genuine and heartfelt response, from Norway to Portugal. Pope Pius IX ordered a special prayer for the success of the Catholic Polish in their defence against the Orthodox Russians, and was very active in arousing sympathy for the Polish rebels.

Uprising in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Antanas Mackevicius

Antanas Mackevičius – was a Lithuanian priest and one of the initiators and leaders of the 1863 January Uprising in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, on the lands of the partitioned Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.- Biography :Antanas Mackevičius was born into a family of minor...

and Konstanty Kalinowski

Konstanty Kalinowski

Wincenty Konstanty Kalinowski , also known under his Polish and Lithuanian names of Konstanty Kalinowski or and Kostas Kalinauskas; 1838 – March 24, 1864) was a writer, journalist, lawyer and revolutionary...

. They fully supported their counterparts in Poland and adhered to the same policy.

Polish, Lithuanian and Belarusian insurgents were more numerous (up to 30,000 men at the peak of uprising) and a little better armed, but there were 135,000 Russian troops and 6,000 Cossacks in Lithuania and another 45,000 Russian troops in Volhynia

Volhynia

Volhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

. In every major military engagement of the uprising insurgents were outnumbered at least 10 to 1.

During the first 24 hours of the uprising armories across the country were looted, many Russian officials executed on sight. February 2, 1863, saw the start of the first major military engagement of the uprising between Polish peasants (mostly armed with scythe) and a squadron of Russian hussars near Čysta Būda, near Marijampolė

Marijampole

Marijampolė is an industrial city and the capital of the Marijampolė County in the south of Lithuania, bordering Poland and Russian Kaliningrad oblast, and Lake Vištytis. The population of Marijampolė is 48,700...

. It ended with a massacre of the unprepared peasants. As hope of a short war was present, insurgent groups merged into bigger formations and recruited new personnel.

On April 7 Zygmunt Sierakowski, who was able to recruit and arm 2500 men for the cause, was elected to be the military commander in chief of the reborn PLC. Under his command the peasant army was able to achieve several difficult victories near Raguva

Raguva

Raguva is a small town in Panevėžys County, in northeastern Lithuania. According to the 2001 census, the town has a population of 610 people....

on April 21, Biržai

Biržai

Biržai is a city in northern Lithuania. Biržai is famous for its reconstructed Biržai Castle manor, and the whole region is renowned for its many traditional-recipe beer breweries.-Names:...

on May 2, Medeikiai on May 7. However, tired from a several week long marches and combat, the insurgent army suffered a defeat on May 8 near Gudiškis.

Evolution of events

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, foreseeing an inevitable armed conflict with France, made friendly overtures to Russia in the Alvensleben Convention

Alvensleben Convention

The Alvensleben Convention was a treaty between the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, named after general Gustav von Alvensleben. It was signed in St. Petersburg on 8 February 1863 by Alvensleben and Alexander Gorchakov.- The Convention :...

and offered assistance in suppressing the Polish uprising. On the 14th day of February arrangements had already been completed, and the British Ambassador in Berlin was able to inform his government that a Prussian military envoy "has concluded a military convention with the Russian Government, according to which the two governments will reciprocally afford facilities to each other for the suppression of the insurrectionary movements which have lately taken place in Poland and Lithuania. The Prussian railways are also to be placed at the disposal of the Russian military authorities for the transportation of troops through Prussian territory from one part of the former Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth to another." This step of Bismarck's led to protests on the part of several governments and roused the nations of the Commonwealth. The result was the transformation of the insignificant uprising into another national war against Russia. Encouraged by the promises made by Napoleon III, all nations, acting upon the advice of Władysław Czartoryski, the son of Prince Adam, took to arms. Indicating their solidarity all Commonwealth citizens holding office under the Russian Government, including the Archbishop of Warsaw, resigned their positions and submitted to the newly constituted Government, which was composed of five most prominent representatives of the Whites.

The diplomatic intervention of the Powers in behalf of Poland, not sustained, except in the case of Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, by a real determination on their part to do something effective for her, did more harm than good to the Polish cause. It alienated Austria which hitherto had maintained a friendly neutrality with reference to Poland and had not interfered with the Polish activities in Galicia. It prejudiced public opinion among the radical groups in Russia who, until that time, had been friendly because they regarded the uprising as of a social rather than a national character and it stirred the Russian Government to more energetic endeavors toward the speedy suppression of hostilities which were growing in strength and determination.

In addition to the thousands who fell in battle, 128 men were hanged personally by Mikhail Muravyov

Mikhail Nikolayevich Muravyov-Vilensky

Count Mikhail Nikolayevich Muravyov was one of the most reactionary Russian imperial statesmen of the 19th century...

('Muravyov the Hangman'), and 9,423 men and women were exiled to Siberia (2,500 men according to very lowered Russian data, Norman Davies

Norman Davies

Professor Ivor Norman Richard Davies FBA, FRHistS is a leading English historian of Welsh descent, noted for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland, and the United Kingdom.- Academic career :...

gives the number of 80,000 noting it was the single largest deportation in Russian history). Whole villages and towns were burned down; all activities were suspended and the szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

was ruined by confiscation and exorbitant taxes. Such was the brutality of the Russian troops that their actions were condemned throughout Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

, and even in Russia itself Muravyov became ostracized. Count Fyodor Berg, the newly appointed Namestnik of Poland, followed in Muravyov's footsteps, employing inhumanly harsh measures against the country. The Reds criticized the Conservative government for its reactionary policy with reference to the peasants but, deluded in its hopes by Napoleon III, the Government counted on French support and persisted in its tactics. It was only after the highly respected and wise Romuald Traugutt took matters in hand that the aspect of the situation became brighter.

He reverted to the policy of the first provisional government and endeavored to bring the peasant masses into active participation by granting to them the land they worked and calling upon all classes to rise. The response was generous but not universal. The wise policy was adopted too late. The Russian Government had already been working among the peasants in the manner above described and giving to them liberal parcels of land for the mere asking. They were completely satisfied, and though not interfering with the revolutionaries to any great extent, became lukewarm to them. Fighting continued intermittently for several months. Among the generals Count Józef Hauke-Bosak

Józef Hauke-Bosak

Count Józef Hauke-Bosak was a Polish general in the January Uprising, and commander of the Polish army in Lesser Poland, the closest collaborator of rebellion leader Romuald Traugutt. He fought many successful battles against the Russians in this region. He fled Poland after the Uprising collapsed...

distinguished himself most as a commander of the revolutionary forces and took several cities from the vastly superior Russian army. When Romuald Traugutt

Romuald Traugutt

Romuald Traugutt was a Polish general and war hero, best known for commanding the January Uprising. From October 1863 to August 1864 he was Dictator of Insurrection. He headed the Polish national government from October 17, 1863 to April 20, 1864, and was president of its Foreign Affairs...

and the four other members of the Polish Government were apprehended by Russian troops and executed at the Warsaw citadel, the war in the course of which six hundred and fifty battles and skirmishes were fought and twenty-five thousand Poles killed, came to a speedy end in the latter half of 1864, having lasted for eighteen months. It is of interest to note that it persisted in Samogitia

Samogitia

Samogitia is one of the five ethnographic regions of Lithuania. It is located in northwestern Lithuania. Its largest city is Šiauliai/Šiaulē. The region has a long and distinct cultural history, reflected in the existence of the Samogitian dialect...

and Podlaskie, where the Greek-Catholic population, outraged and persecuted for their religious convictions, clung longest to the revolutionary banner.

The uprising was finally crushed by Russia in 1864.

After the collapse of the uprising, harsh reprisals followed. According to Russian official information, 396 persons were executed and 18,672 were exiled to Siberia. Large numbers of men and women were sent to the interior of Russia and to Caucasus

Caucasus

The Caucasus, also Caucas or Caucasia , is a geopolitical region at the border of Europe and Asia, and situated between the Black and the Caspian sea...

, Urals

Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the Ural River and northwestern Kazakhstan. Their eastern side is usually considered the natural boundary between Europe and Asia...

and other sections. Altogether about 70,000 persons were imprisoned and subsequently taken out of Poland and stationed in the remote regions of Russia.

The government confiscated 1,660 estates in Poland and 1,794 in Lithuania. A 10% income tax was imposed on all estates as a war indemnity. Only in 1869 was this tax reduced to 5% on all incomes. Serfdom was abolished in Russian Poland on February 19th 1864. It was deliberately enacted in a way that would ruin the szlachta. It was the only area where peasants paid the market price in redemption for the land (the average for the empire was 34% above the market price). All land taken from Polish peasants since 1846 was to be returned without redemption payments. The ex-serfs could only sell land to other peasants, not szlachta. 90% of the ex serfs in the empire who actually gained land after 1861 were in the 8 western provinces. Along with Romania, Polish landless or domestic serfs were the only ones to be given land after serfdom was abolished.[9] All this was to punish the szlachta's role in the uprisings of 1830 and 1863. Besides the land granted to the peasants, the Russian Government gave them additional forest, pasture and other privileges (known under the name of servitutes) which proved to be a source of incessant irritation between the landowners and peasants in the following decades, and an impediment to economic development. The government took over all the church estates and funds, and abolished monasteries and convents. With the exception of religious instruction, all other studies in the schools were ordered to be in Russian

Russian language

Russian is a Slavic language used primarily in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It is an unofficial but widely spoken language in Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Turkmenistan and Estonia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics...

. Russian also became the official language of the country, used exclusively in all offices of the general and local government. All traces of the former Polish autonomy were removed and the kingdom was divided into ten provinces, each with an appointed Russian military governor and all under complete control of the Governor-General at Warsaw. All the former government functionaries were deprived of their positions.

This measures proved to be of limited success. In 1905, 41 years after Russian crushing of the uprising, the next generation of Poles rose once again in a new one.

Famous insurgents

- Stanisław Brzóska (1832–1865) was a Polish priest and commander at the end of the insurrection.

- Władysław Niegolewski (1819–1885) was a liberal Polish politician and member of parliament, an insurgent in the Greater Poland Uprisings of 1846 and 1848 and of the January 1863 Uprising, and a co-founder (1861) of the Central Economic Society (TCL) and (1880) the People's Libraries SocietyPeople's Libraries SocietyPeople's Libraries Society was an educational society established in 1880 for the Prussian partition of Poland...

(CTG). - Konstanty KalinowskiKonstanty KalinowskiWincenty Konstanty Kalinowski , also known under his Polish and Lithuanian names of Konstanty Kalinowski or and Kostas Kalinauskas; 1838 – March 24, 1864) was a writer, journalist, lawyer and revolutionary...

(1838–1864) was one of the leaders of LithuaniaLithuaniaLithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

n and BelarusBelarusBelarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

ian national revivalRomantic nationalismRomantic nationalism is the form of nationalism in which the state derives its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs...

and the leader of the January Uprising in the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. - Saint Raphael KalinowskiRaphael KalinowskiRafał Kalinowski, O.C.D. was a Polish Discalced Carmelite friar born as Józef Kalinowski inside the Russian partition of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the city of Vilnius...

, born Joseph Kalinowski in Lithuania, resigned as a Captain from the Russian Army to become Minister of War for the Polish insurgents. He was arrested and sentenced to death by firing squad, but the sentence was then changed to 10 years in Siberia, including a grueling nine-month overland trek to get there. - Aleksander SochaczewskiAleksander Sochaczewski[File:Pożegnanie Europy.JPG|466px|thumb|right|Farewell to Europe, by Aleksander Sochaczewski. The artist himself is among the exiled here, near the obelisk, on the right....

, painter - Bolesław Prus, later a Polish writer

- Apollo KorzeniowskiApollo KorzeniowskiApollo Korzeniowski was a Polish poet, playwright, clandestine political activist, and father of Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad.-Life:...

, Polish playwright and father of Joseph ConradJoseph ConradJoseph Conrad was a Polish-born English novelist.Conrad is regarded as one of the great novelists in English, although he did not speak the language fluently until he was in his twenties...

.

January Uprising in literature

- Polish poet Cyprian NorwidCyprian NorwidCyprian Kamil Norwid, a.k.a. Cyprian Konstanty Norwid is a nationally esteemed Polish poet, dramatist, painter, and sculptor. He was born in the Masovian village of Laskowo-Głuchy near Warsaw. One of his maternal ancestors was Polish King John III Sobieski.Norwid is regarded as one of the second...

wrote a famous poem, "Chopin's Piano," describing the defenestrationDefenestrationDefenestration is the act of throwing someone or something out of a window.The term "defenestration" was coined around the time of an incident in Prague Castle in the year 1618. The word comes from the Latin de- and fenestra...

of the composer's pianoPianoThe piano is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. It is one of the most popular instruments in the world. Widely used in classical and jazz music for solo performances, ensemble use, chamber music and accompaniment, the piano is also very popular as an aid to composing and rehearsal...

during the January 1863 Uprising, when Russian soldiers maliciously threw the instrument out of a second-floor WarsawWarsawWarsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

apartment. Chopin had left Warsaw and Poland forever shortly before the outbreak of the November 1830 UprisingNovember UprisingThe November Uprising , Polish–Russian War 1830–31 also known as the Cadet Revolution, was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in Warsaw when the young Polish officers from the local Army of the Congress...

. - In the initial draft of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the SeaTwenty Thousand Leagues Under the SeaTwenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea is a classic science fiction novel by French writer Jules Verne published in 1870. It tells the story of Captain Nemo and his submarine Nautilus as seen from the perspective of Professor Pierre Aronnax...

by Jules VerneJules VerneJules Gabriel Verne was a French author who pioneered the science fiction genre. He is best known for his novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea , A Journey to the Center of the Earth , and Around the World in Eighty Days...

, Captain NemoCaptain NemoCaptain Nemo, also known as Prince Dakkar, is a fictional character featured in Jules Verne's novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island ....

was a Polish nobleman whose family had been brutally murdered by the Russians during the January 1863 Uprising. Since France had only recently signed an alliance with Tsarist Russia, in the novelNovelA novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

's final version Verne's editor, Pierre-Jules HetzelPierre-Jules HetzelPierre-Jules Hetzel was a French editor and publisher. He is best known for his extraordinarily lavishly illustrated editions of Jules Verne's novels highly prized by collectors today...

, made him obscure Nemo's motives. - In Guy de MaupassantGuy de MaupassantHenri René Albert Guy de Maupassant was a popular 19th-century French writer, considered one of the fathers of the modern short story and one of the form's finest exponents....

's novel Pierre et JeanPierre et JeanPierre et Jean is a naturalist or psycho-realist work written by Guy de Maupassant in Étretat in his native Normandy between June and September 1887 . This was Maupassant’s shortest novel. It appeared in three instalments in the Nouvelle Revue and then in volume form in 1888, together with the...

, the protagonist Pierre has a friend, an old Polish chemist that is said to come to FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

after the bloody events in his motherland. This story is believed to refer to the January Uprising.

See also

- Baikal insurrection 1866

- Great EmigrationGreat EmigrationThe Great Emigration was an emigration of political elites from Poland from 1831–1870. Since the end of the 18th century, a major role in Polish political life was played by people who carried out their activities outside the country as émigrés...

- Insurgence

- Polish National Government

- Polish uprisings

- Sybirak

- International Workingmen's AssociationInternational Workingmen's AssociationThe International Workingmen's Association , sometimes called the First International, was an international organization which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist political groups and trade union organizations that were based on the working class...

External links

- Peter KropotkinPeter KropotkinPrince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian zoologist, evolutionary theorist, philosopher, economist, geographer, author and one of the world's foremost anarcho-communists. Kropotkin advocated a communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations between...

, Memoirs of a Revolutionist & Co., 1899, pp. 174–180. - Augustin O'Brien Petersburg and Warsaw: scenes witnessed during a residence in Poland and Russia in 1863-1864 (1864)

- William Ansell Day. The Russian government in Poland : with a narrative of the Polish Insurrection of 1863 (1867)

- Pictures and paintings dedicated January Uprising on Youtube