Jewish Polish history origins to 1600s

Encyclopedia

Early history

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

and Bukhara

Bukhara

Bukhara , from the Soghdian βuxārak , is the capital of the Bukhara Province of Uzbekistan. The nation's fifth-largest city, it has a population of 263,400 . The region around Bukhara has been inhabited for at least five millennia, and the city has existed for half that time...

, the Jewish merchants (who included the Radhanites) also crossed the areas of Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

. One of them, a diplomat and merchant from the Moorish

Moors

The description Moors has referred to several historic and modern populations of the Maghreb region who are predominately of Berber and Arab descent. They came to conquer and rule the Iberian Peninsula for nearly 800 years. At that time they were Muslim, although earlier the people had followed...

town of Tortosa

Tortosa

-External links:* *** * * *...

in Al-Andalus

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

, known under his Arabic name Ibrahim ibn Jakub was the first chronicler to mention the Polish state under the rule of prince Mieszko I

Mieszko I of Poland

Mieszko I , was a Duke of the Polans from about 960 until his death. A member of the Piast dynasty, he was son of Siemomysł; grandchild of Lestek; father of Bolesław I the Brave, the first crowned King of Poland; likely father of Świętosława , a Nordic Queen; and grandfather of her son, Cnut the...

. The first actual mention of Jews in Polish chronicles occurs in the 11th century. It appears that Jews were then living in Gniezno

Gniezno

Gniezno is a city in central-western Poland, some 50 km east of Poznań, inhabited by about 70,000 people. One of the Piasts' chief cities, it was mentioned by 10th century A.D. sources as the capital of Piast Poland however the first capital of Piast realm was most likely Giecz built around...

, at that time the capital of the Polish kingdom of Piast dynasty

Piast dynasty

The Piast dynasty was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. It began with the semi-legendary Piast Kołodziej . The first historical ruler was Duke Mieszko I . The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir the Great...

. Some of them were wealthy, owning Christian serf

SERF

A spin exchange relaxation-free magnetometer is a type of magnetometer developed at Princeton University in the early 2000s. SERF magnetometers measure magnetic fields by using lasers to detect the interaction between alkali metal atoms in a vapor and the magnetic field.The name for the technique...

s in keeping with the Feudal system of the times. The first permanent Jewish community is mentioned in 1085 by a Jewish scholar Jehuda ha Kohen in the city of Przemyśl

Przemysl

Przemyśl is a city in south-eastern Poland with 66,756 inhabitants, as of June 2009. In 1999, it became part of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship; it was previously the capital of Przemyśl Voivodeship....

.

The first extensive Jewish emigration from Western Europe to Poland occurred at the time of the First Crusade

First Crusade

The First Crusade was a military expedition by Western Christianity to regain the Holy Lands taken in the Muslim conquest of the Levant, ultimately resulting in the recapture of Jerusalem...

(1098). Under Boleslaw III Krzywousty (1102–1139), the Jews, encouraged by the tolerant régime of this ruler, settled throughout Poland, including over the border into Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

n territory as far as Kiev. At the same time Poland saw possible immigration of Khazars

Khazars

The Khazars were semi-nomadic Turkic people who established one of the largest polities of medieval Eurasia, with the capital of Atil and territory comprising much of modern-day European Russia, western Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, large portions of the northern Caucasus , parts of...

, a Turkic

Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are peoples residing in northern, central and western Asia, southern Siberia and northwestern China and parts of eastern Europe. They speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family. They share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds...

tribe that had converted to Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

. Boleslaw on his part recognized the utility of the Jews it the development of the commercial interests

Commerce

While business refers to the value-creating activities of an organization for profit, commerce means the whole system of an economy that constitutes an environment for business. The system includes legal, economic, political, social, cultural, and technological systems that are in operation in any...

of his country. The Prince of Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

, Mieszko III the Old

Mieszko III the Old

Mieszko III the Old , of the royal Piast dynasty, was Duke of Greater Poland from 1138 and High Duke of Poland, with interruptions, from 1173 until his death....

(1173–1202), in his endeavor to establish law and order in his domains, prohibited all violence against the Jews, particularly attacks upon them by unruly students (żacy). Boys guilty of such attacks, or their parents, were made to pay fines as heavy as those imposed for sacrilegious

Sacrilege

Sacrilege is the violation or injurious treatment of a sacred object. In a less proper sense, any transgression against the virtue of religion would be a sacrilege. It can come in the form of irreverence to sacred persons, places, and things...

acts.

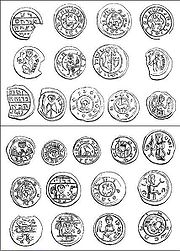

Coins unearthed in 1872 in the Polish village of Glenbok bear Hebrew

Hebrew alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet , known variously by scholars as the Jewish script, square script, block script, or more historically, the Assyrian script, is used in the writing of the Hebrew language, as well as other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, and Judeo-Arabic. There have been two...

inscriptions, suggesting that Jews were in charge of the coinage in Great and Little Poland during the 12th century. These coins bear emblems having inscriptions of various characters; in some examples only the name of the king or prince being given, as, for instance, "Prince Meshko", while in others the surname is added, as "Meshek the Blessed" or "the Just." Some of the coins, moreover, bear inscriptions having no direct reference to Poland, to the reigning princes, or even to the coin itself, but referring to incidents of a purely Jewish character, as, for instance, "Rejoice, Abraham

Abraham

Abraham , whose birth name was Abram, is the eponym of the Abrahamic religions, among which are Judaism, Christianity and Islam...

, Isaac

Isaac

Isaac as described in the Hebrew Bible, was the only son Abraham had with his wife Sarah, and was the father of Jacob and Esau. Isaac was one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites...

, and Jacob

Jacob

Jacob "heel" or "leg-puller"), also later known as Israel , as described in the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, the New Testament and the Qur'an was the third patriarch of the Hebrew people with whom God made a covenant, and ancestor of the tribes of Israel, which were named after his descendants.In the...

"; "Abraham Duchs and Abraham Pech (some scholars, including Maximilian Gumplovicz and Avraham Firkovich, identified, probably erroneously, "Pech" with the Khazar title of Bek

Khagan Bek

-History:Khazar kingship was divided between the khagan and the Bek or Khagan Bek. Contemporary Arab historians related that the Khagan was purely a spiritual ruler or figurehead with limited powers, while the Bek was responsible for administration and military affairs.In the Khazar Correspondence,...

)." Similar coins had been discovered elsewhere several years earlier; but, owing to their peculiar inscriptions, doubts were expressed, even by such a noted numismatist as Joachim Lelewel

Joachim Lelewel

Joachim Lelewel was a Polish historian and politician, from a Polonized branch of a Prussian family.His grandparents were Heinrich Löllhöffel von Löwensprung and Constance Jauch , who later polonized her name to Lelewel.-Life:Born in Warsaw, Lelewel was educated at the Imperial University of...

, as to their being coins at all. Their true nature was revealed only with the discovery of the Glenbok treasure. All the inscriptions on the coins of the 12th century are in Hebrew; and they sufficiently prove that at the time in question the Jews had already established themselves in positions of trust and prominence, and were contented with their lot.

Kalisz

Kalisz is a city in central Poland with 106,857 inhabitants , the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of the Greater Poland Voivodeship, the city forms a conurbation with the nearby towns of Ostrów Wielkopolski and Nowe Skalmierzyce...

and their entire community" were permitted on the strength of the charter of privileges granted by Boleslaw of Kalisz to Jewish immigrants, for the charter makes no mention of a Jewish community, nor of the right of Jews to acquire landed property. "The facts", says Bershadski, "made plain by the grant of Premyslaw II. prove that the Jews were ancient inhabitants of Poland, and that the charter of Boleslaw of Kalisz, copied almost verbally from the privileges of Ottocar of Bohemia, was merely a written approval of relations that had become gradually established, and had received the sanction of the people of the country." Bershadski comes to the conclusion that as early as the 13th century there existed in Poland a number of Jewish communities, the most important of which was that of Kalisz.

Early in the 13th century Jews owned land in Polish Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

, Greater Poland

Greater Poland

Greater Poland or Great Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief city is Poznań.The boundaries of Greater Poland have varied somewhat throughout history...

and Kuyavia

Kuyavia

Kujawy , is a historical and ethnographic region in the north-central Poland, situated in the basin of the middle Vistula and upper Noteć Rivers, with its capital in Włocławek.-Etymology:The origin of the name Kujawy was seen differently in history...

, including the village of Mały Tyniec. There were also established Jewish communities in Wrocław, Świdnica

Swidnica

Świdnica is a city in south-western Poland in the region of Silesia. It has a population of 60,317 according to 2006 figures. It lies in Lower Silesian Voivodeship, being the seventh largest town in that voivodeship. From 1975–98 it was in the former Wałbrzych Voivodeship...

, Głogów, Lwówek

Lwówek Slaski

Lwówek Śląski is a town in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship in Poland. Situated on the Bóbr River, Lwówek Śląski is about 30 km NNW of Jelenia Góra and has a population of about 10,300 inhabitants...

, Płock, Kalisz

Kalisz

Kalisz is a city in central Poland with 106,857 inhabitants , the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of the Greater Poland Voivodeship, the city forms a conurbation with the nearby towns of Ostrów Wielkopolski and Nowe Skalmierzyce...

, Szczecin

Szczecin

Szczecin , is the capital city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in Poland. It is the country's seventh-largest city and the largest seaport in Poland on the Baltic Sea. As of June 2009 the population was 406,427....

, Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

and Gniezno

Gniezno

Gniezno is a city in central-western Poland, some 50 km east of Poznań, inhabited by about 70,000 people. One of the Piasts' chief cities, it was mentioned by 10th century A.D. sources as the capital of Piast Poland however the first capital of Piast realm was most likely Giecz built around...

. It is clear that the Jewish communities must have been well-organized by then. Also, the earliest known artifact of Jewish settlement on Polish soil is a tombstone of certain David ben Sar Shalom found in Wrocław and dated 25 av 4963, that is August 4, 1203.

From the various sources it is evident that at this time the Jews enjoyed undisturbed peace and prosperity in the many principalities into which the country was then divided. In the interests of commerce the reigning princes extended protection and special privileges to the Jewish settlers. With the descent of the Mongols

Mongols

Mongols ) are a Central-East Asian ethnic group that lives mainly in the countries of Mongolia, China, and Russia. In China, ethnic Mongols can be found mainly in the central north region of China such as Inner Mongolia...

on Polish territory (1241) the Jews in common with the other inhabitants suffered severely. Kraków was pillaged and burned, other towns were devastated, and hundreds of Poles, including many Jews, were carried into captivity. As the tide of invasion receded the Jews returned to their old homes and occupations. They formed the middle class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

in a country where the general population consisted of landlords (developing into szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

, the unique Polish nobility) and peasants, and they were instrumental in promoting the commercial interests of the land. Money-lending and the farming of the different government revenues, such as those from the salt mine

Salt mine

A salt mine is a mining operation involved in the extraction of rock salt or halite from evaporite deposits.-Occurrence:Areas known for their salt mines include Kilroot near Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland ; Khewra and Warcha in Pakistan; Tuzla in Bosnia; Wieliczka and Bochnia in Poland A salt mine...

s, the customs

Customs

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting and safeguarding customs duties and for controlling the flow of goods including animals, transports, personal effects and hazardous items in and out of a country...

, etc., were their most important pursuits. The native population had not yet become permeated with the religious intolerance of western Europe, and lived at peace with the Jews.

Early persecutions: 1266-1279

The tolerant situation was gradually altered by the Roman Catholic ChurchRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

on the one hand, and by the neighboring German states on the other. The emissaries of the Roman pontiffs

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

came to Poland in pursuance of a fixed policy; and in their endeavors to strengthen the influence of the Catholic Church they spread teachings imbued with intolerance toward the followers of Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

. At the same time Boleslaw V Wstydliwy (1228–1279), encouraged the influx of German colonists. He granted to them the Magdeburg Rights

Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg Rights or Magdeburg Law were a set of German town laws regulating the degree of internal autonomy within cities and villages granted by a local ruler. Modelled and named after the laws of the German city of Magdeburg and developed during many centuries of the Holy Roman Empire, it was...

, and by establishing them in the towns introduced there an element which brought with it deep-seated prejudices against the Jews.

There were, however, among the reigning princes some determined protectors of the Jewish inhabitants, who considered the presence of the latter most desirable in so far as the economic development of the country was concerned. Prominent among such rulers was Boleslaw Pobozny, called the Pious, of Kalisz

Kalisz

Kalisz is a city in central Poland with 106,857 inhabitants , the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of the Greater Poland Voivodeship, the city forms a conurbation with the nearby towns of Ostrów Wielkopolski and Nowe Skalmierzyce...

, Prince of Great Poland. With the consent of the class representatives and higher officials, in 1264 he issued a General Charter of Jewish Liberties, the Statute of Kalisz

Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the Statute of Kalisz was issued by the Duke of Greater Poland Boleslaus the Pious on September 8, 1264 in Kalisz...

, which clearly defined the position of his Jewish subjects. The charter dealt in detail with all sides of Jewish life, particularly the relations of the Jews to their Christian neighbors. The guiding principle in all its provisions was justice, while national, racial, and religious motives were entirely excluded. It granted all Jews the freedom of worship, trade and travel. Also, all Jews under the suzerainity of the duke were protected by the Voivode and killing a Jew was penalized with death and the confiscation of all the property of the murderer's family.

But while the secular authorities endeavored to regulate the relations of the Jews to the country at large in accordance with its economic needs, the clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

, inspired by the attempts of the Roman Catholic Church to establish its universal supremacy, used its influence toward separating the Jews from the body politic, aiming to exclude them, as people dangerous to the Church, from Christian society, and to place them in the position of a despised "sect

Sect

A sect is a group with distinctive religious, political or philosophical beliefs. Although in past it was mostly used to refer to religious groups, it has since expanded and in modern culture can refer to any organization that breaks away from a larger one to follow a different set of rules and...

". In 1266 an ecumenical council

Ecumenical council

An ecumenical council is a conference of ecclesiastical dignitaries and theological experts convened to discuss and settle matters of Church doctrine and practice....

was held at Wrocław under the chairmanship of the papal nuncio

Nuncio

Nuncio is an ecclesiastical diplomatic title, derived from the ancient Latin word, Nuntius, meaning "envoy." This article addresses this title as well as derived similar titles, all within the structure of the Roman Catholic Church...

Guido. The council introduced into the ecclesiastical statutes of Poland a number of paragraphs directed against the Jews.

The Jews were ordered to dispose as quickly as possible of real estate owned by them in the Christian quarters; they were not to appear on the streets during Church processions; they were allowed to have only a single synagogue

Synagogue

A synagogue is a Jewish house of prayer. This use of the Greek term synagogue originates in the Septuagint where it sometimes translates the Hebrew word for assembly, kahal...

in any one town; and they were required to wear a special cap to distinguish them from the Christians. The latter were forbidden, under penalty of excommunication, to invite Jews to feasts or other entertainments, and were forbidden also to buy meat or other provisions from Jews, for fear of being poisoned. The council furthermore confirmed the regulations under which Jews were not allowed to keep Christian servants, to lease taxes or customs duties, or to hold any public office. At the Council of Ofen held in 1279 the wearing of a red badge was prescribed for the Jews, and the foregoing provisions were reaffirmed.

Prosperity in a reunited Poland: 1320-1385

Though the Catholic clergy continued to spread the religious hatred, the contemporary rulers were not inclined to accept the edicts of the Church, and the Jews of Poland were for a long time allowed their rights. Ladislaus Lokietek, who ascended the Polish throne in 1320, endeavored to establish a uniform legal code throughout the land. With the general laws he assured the Jews safety and freedom and placed them on equality with the Christians. They dressed like the Christians, wearing garments similar to those of the nobility, and, like the latter, also wore gold chains and carried swords. Lokietek likewise framed laws for the lending of money to Christians.

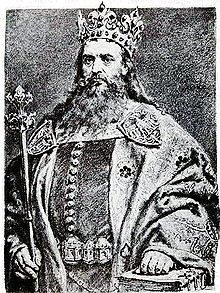

Casimir III of Poland

Casimir III the Great , last King of Poland from the Piast dynasty , was the son of King Władysław I the Elbow-high and Hedwig of Kalisz.-Biography:...

(1303–1370) amplified and expanded Boleslaw's old charter with the Wislicki Statute. Casimir was especially friendly to the Jews, and his reign is regarded as an era of great prosperity for Polish Jewry. His improved charter

Charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified...

was even more favorable to the Jews than was Boleslaw's, insofar as it safeguarded some of their civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

in addition to their commercial privileges. This far-sighted ruler sought to employ the town and rural populations as checks upon the growing power of the aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

. He regarded the Jews not simply as an association of money-lenders, but as a part of the nation, into which they were to be incorporated for the formation of a homogeneous body politic. For his attempts to uplift the masses, including the Jews, Casimir was surnamed by his contemporaries "King of the serfs and Jews."

Nevertheless, while for the greater part of Casimir's reign the Jews of Poland enjoyed tranquility, toward its close they were subjected to persecution on account of the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

. Massacres occurred at Kalisz

Kalisz

Kalisz is a city in central Poland with 106,857 inhabitants , the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of the Greater Poland Voivodeship, the city forms a conurbation with the nearby towns of Ostrów Wielkopolski and Nowe Skalmierzyce...

, Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

, Głogów, and other Polish cities along the German frontier, and it is estimated that 10,000 Jews were killed. Compared with the pitiless destruction of their coreligionists in Western Europe, however, the Polish Jews did not fare badly; and the Jewish masses of Germany fled to the more hospitable lands of Poland, where the interests of the laity still remained more powerful than those of the Church.

But under Casimir's successor, Louis I of Hungary (1370–1384), the complaint became general that "justice had disappeared from the land". An attempt was made to deprive the Jews of the protection of the laws. Guided mainly by religious motives, Louis I persecuted them, and threatened to expel those who refused to accept Christianity. His short reign did not suffice, however, to undo the beneficent work of his predecessor; and it was not until the long reign of the Lithuanian Grand Duke and King of Poland Wladislaus II

Jogaila

Jogaila, later 'He is known under a number of names: ; ; . See also: Jogaila : names and titles. was Grand Duke of Lithuania , king consort of Kingdom of Poland , and sole King of Poland . He ruled in Lithuania from 1377, at first with his uncle Kęstutis...

(1386–1434), that the influence of the Church in civil and national affairs increased, and the civic condition of the Jews gradually became less favorable. Nevertheless, at the beginning of Wladislaus' reign the Jews still enjoyed extensive protection of the laws.

Persecutions of 1385-1492

As a result of the marriage of Wladislaus IIJogaila

Jogaila, later 'He is known under a number of names: ; ; . See also: Jogaila : names and titles. was Grand Duke of Lithuania , king consort of Kingdom of Poland , and sole King of Poland . He ruled in Lithuania from 1377, at first with his uncle Kęstutis...

to Jadwiga

Jadwiga of Poland

Jadwiga was monarch of Poland from 1384 to her death. Her official title was 'king' rather than 'queen', reflecting that she was a sovereign in her own right and not merely a royal consort. She was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou, the daughter of King Louis I of Hungary and Elizabeth of...

, daughter of Louis I of Hungary, Lithuania was united with the kingdom of Poland

Polish-Lithuanian Union

The term Polish–Lithuanian Union sometimes called as United Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania refers to a series of acts and alliances between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that lasted for prolonged periods of time and led to the creation of the Polish–Lithuanian...

. Under his rule the first extensive persecutions of the Jews in Poland were commenced, and the king did not act to stop these events. It was said that the Jews of Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

had induced a poor Christian woman to steal from the Dominican order

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

"three hosts", which they "desecrated", and that when the hosts began to bleed, the Jews had thrown them into a ditch, whereupon various "miracles" occurred. When informed of this supposed "desecration", the Bishop of Poznań ordered the Jews to answer the charges. The woman accused the rabbi

Rabbi

In Judaism, a rabbi is a teacher of Torah. This title derives from the Hebrew word רבי , meaning "My Master" , which is the way a student would address a master of Torah...

of Poznań of stealing the hosts, and thirteen elders of the Jewish community fell victim to the superstitious rage of the people. After long-continued torture on the rack they were all burned at the stake

Execution by burning

Death by burning is death brought about by combustion. As a form of capital punishment, burning has a long history as a method in crimes such as treason, heresy, and witchcraft....

. In addition, a permanent fine was imposed on the Jews of Poznań, which they were required to pay annually to the Dominicans. This fine was rigorously collected until the 18th century. The persecution of the Jews was due not only to religious motives, but also to economic reasons, for the Jews had gained control of certain branches of commerce, and the burghers

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

, jealous of their success, desired to rid themselves in one way or another of their objectionable competitors.

The same motives were responsible for the riot of Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

, instigated by the fanatical priest Budek in 1407. The first outbreak was suppressed by the city magistrates; but it was renewed a few hours later. A vast amount of property was destroyed; many Jews were killed; and their children were baptized. In order to save their lives a number of Jews accepted Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

. The reform movement of the Czech

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

Hussites intensified religious fanaticism; and the resulting reactionary measures spread to Poland. The influential Polish archbishop Nicholas Tronba, after his return from the Council of Kalisz (1420), over which he had presided, induced the Polish clergy to confirm all the anti-Jewish legislation adopted at the councils of Wrocław and Ofen, and which until then had been rarely carried out. In addition to their previous disabilities

Disabilities (Jewish)

Disabilities were legal restrictions and limitations placed on Jews in the Middle Ages. They included provisions requiring Jews to wear specific and identifying clothing such as the Jewish hat and the yellow badge, restricting Jews to certain cities and towns or in certain parts of towns , and...

, the Jews were now compelled to pay a tax for the benefit of the churches in the precincts in which they were residing, but "in which only Christians should reside."

In 1423 King Wladislaus II

Jogaila

Jogaila, later 'He is known under a number of names: ; ; . See also: Jogaila : names and titles. was Grand Duke of Lithuania , king consort of Kingdom of Poland , and sole King of Poland . He ruled in Lithuania from 1377, at first with his uncle Kęstutis...

issued an edict forbidding the Jews to lend money on notes. In his reign, as in the reign of his successor, Vladislaus III, the ancient privileges of the Jews were almost forgotten. The Jews vainly appealed to Wladislaus II

Jogaila

Jogaila, later 'He is known under a number of names: ; ; . See also: Jogaila : names and titles. was Grand Duke of Lithuania , king consort of Kingdom of Poland , and sole King of Poland . He ruled in Lithuania from 1377, at first with his uncle Kęstutis...

for the confirmation of their old charters. The clergy successfully opposed the renewal of these privileges on the ground that they were contrary to the canonical regulations. To achieve this, the rumor was even spread that the charter claimed to have been granted to the Jews by Casimir III was a forgery, as a Catholic ruler would never have granted full civil rights to "unbelievers."

The machinations of the clergy were checked by Casimir IV the Jagiellonian (1447–1492). He readily renewed the charter granted to the Jews by Casimir the Great, the original of which had been destroyed in the fire that devastated Poznań in 1447. To a Jewish deputation from the communities of Poznań, Kalisz

Kalisz

Kalisz is a city in central Poland with 106,857 inhabitants , the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of the Greater Poland Voivodeship, the city forms a conurbation with the nearby towns of Ostrów Wielkopolski and Nowe Skalmierzyce...

, Sieradz

Sieradz

Sieradz is a town on the Warta river in central Poland with 44,326 inhabitants . It is situated in the Łódź Voivodship , but was previously the eponymous capital of the Sieradz Voivodship , and historically one of the minor duchies in Greater Poland.It is one of the oldest towns in Poland,...

, Łęczyca, Brest

Brest, Belarus

Brest , formerly also Brest-on-the-Bug and Brest-Litovsk , is a city in Belarus at the border with Poland opposite the city of Terespol, where the Bug River and Mukhavets rivers meet...

, and Wladislavov which applied to him for the renewal of the charter, he said in his new grant: "We desire that the Jews, whom we protect especially for the sake of our own interests and those of the royal treasury, shall feel contented during our prosperous reign." In confirming all previous rights and privileges of the Jews: the freedom of residence and trade; judicial and communal autonomy; the inviolability of person and property; and protection against arbitrary accusation and attacks; the charter of Casimir IV was a determined protest against the canonical laws, which had been recently renewed for Poland by the Council of Kalisz

Kalisz

Kalisz is a city in central Poland with 106,857 inhabitants , the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of the Greater Poland Voivodeship, the city forms a conurbation with the nearby towns of Ostrów Wielkopolski and Nowe Skalmierzyce...

, and for the entire Catholic world by the Diet of Basel. The charter, moreover, permitted more interaction between Jews and Christians, and freed the former from the jurisdiction of the clerical courts. Strong opposition was created by the King's liberal attitude toward the Jews, and was voiced by the leaders of the clerical party.

The repeated appeals of the clergy, and the defeat of the Polish troops by the Teutonic Knights

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem , commonly the Teutonic Order , is a German medieval military order, in modern times a purely religious Catholic order...

, which the clergy openly ascribed to the "wrath of God" at Casimir's neglect of the interests of the Church, and his friendly attitude toward the Jews, finally induced the King to accede to the demands which had been made. In 1454 the Statutes of Nieszawa

Statutes of Nieszawa

The Nieszawa Statutes were a set of laws enacted in the Kingdom of Poland in 1454, in the town of Nieszawa. Kazimierz IV Jagiellon made a number of concessions to the nobility in exchange for their support in the Thirteen Years' War...

was issued, which granted many privileges to szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

and included the abolition of the ancient privileges of the Jews "as contrary to divine right and the law of the land." The triumph of the clerical forces was soon felt by the Jewish inhabitants. The populace was encouraged to attack them in many Polish cities; the Jews of Kraków were again the greatest sufferers. In the spring of 1464 the Jewish quarters of the city were devastated by a mob composed of monks, students, peasants, and the minor nobles, who were then organizing a new crusade against the Turks

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. More than thirty Jews were killed, and many houses were destroyed. Similar disorders occurred in Poznań and elsewhere, notwithstanding the fact that Casimir had fined the Kraków magistrates for having failed to take stringent measures for the suppression of the previous riots.

Influx of Jews fleeing persecution: 1492-1548

The policy of the government toward the Jews of Poland was not more tolerant under Casimir's sons and successors, John I Olbracht (1492–1501) and Alexander the Jagiellonian (1501–1506). John I Olbracht frequently found himself obliged to judge local disputes between Jewish and Christian merchants. Thus in 1493 he adjusted the conflicting claims of the Jewish merchants and the burghers of LwówLviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

concerning the right to trade freely within the city. On the whole, however, he was not friendly to the Jews. The same may be said of Alexander the Jagiellonian, who had expelled the Jews from Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state from the 12th /13th century until 1569 and then as a constituent part of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1791 when Constitution of May 3, 1791 abolished it in favor of unitary state. It was founded by the Lithuanians, one of the polytheistic...

in 1495. To some extent he was undoubtedly influenced in this measure by the expulsion of the Jews from Spain (1492) (the Alhambra decree

Alhambra decree

The Alhambra Decree was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ordering the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Spain and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.The edict was formally revoked on 16 December 1968, following the Second...

), which was responsible also for the increased persecution of the Jews in Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, and Germany, and thus stimulated the Jewish emigration to comparatively much more tolerant Poland. For various reasons Alexander permitted the return of the Jews in 1503, and during the period immediately preceding the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

the number of Jews in Poland grew rapidly on account of the anti-Jewish agitation in Germany. Indeed, Poland became the recognized haven of refuge for exiles from western Europe; and the resulting accession to the ranks of the Polish Jewry made it the cultural and spiritual center of the Jewish people. This, as has been suggested by the Jewish historian

Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, their religion and culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions and cultures. Since Jewish history is over 4000 years long and includes hundreds of different populations, any treatment can only be provided in broad strokes...

Dubnow

Simon Dubnow

Simon Dubnow was a Jewish historian, writer and activist...

, was rendered possible by the following conditions:

- The Jewish population of Poland was at that time greater than that of any other European country; the Jews enjoyed an extensive communal autonomy based on special privileges; they were not confined in their economic life to purely subordinate occupations, as was true of their western coreligionists; they were not engaged solely in petty trade and money-lending, but carried on also an important export trade, leased government revenues and large estates, and followed the handicrafts and, to a certain extent, agricultureAgricultureAgriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

; in the matter of residence they were not restricted to ghettoGhettoA ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

s, like their German brethren. All these conditions contributed toward the evolution in Poland of an independent Jewish civilization. Thanks to its social and judicial autonomy, Polish Jewish life was enabled to develop freely along the lines of national and religious tradition. The rabbiRabbiIn Judaism, a rabbi is a teacher of Torah. This title derives from the Hebrew word רבי , meaning "My Master" , which is the way a student would address a master of Torah...

became not only the spiritual guide, but also a member of the communal administration KahalKahalKahal is a moshav in the Galilee near Highway 85 in northern Israel. The moshav is a combined agricultural community. It lies at the border of the Upper Galilee and Lower Galilee, north of Lake Kinneret and just northwest of Tabgha. It belongs to the Mevo'ot HaHermon Regional Council and was...

, a civil judge, and the authoritative expounder of the Law. RabbinismRabbinic JudaismRabbinic Judaism or Rabbinism has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Talmud...

was not a dead letter here, but a guiding religio-judicial system; for the rabbis adjudged civil as well as certain criminal cases on the basis of TalmudTalmudThe Talmud is a central text of mainstream Judaism. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs and history....

ic legislation.

The Jews of Poland found themselves obliged to make increased efforts to strengthen their social and economic position, and to win the favor of the king and of the nobility. The conflicts of the different parties, of the merchants, the clergy, the lesser and the higher nobility, enabled the Jews to hold their own. The opposition of the Christian merchants and of the clergy was counterbalanced by the support of the nobility (szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

), who derived certain economic benefits from the activities of the Jews. By the nihil novi

Nihil novi

Nihil novi nisi commune consensu is the original Latin title of a 1505 act adopted by the Polish Sejm , meeting in the royal castle at Radom.-History:...

constitution of 1505, sanctioned by Alexander the Jagiellonian, the Szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

Diets

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

were given a voice in all important national matters. On some occasions the Jewish merchants, when pressed by the lesser nobles, were afforded protection by the king, since they were an important source of royal revenue.

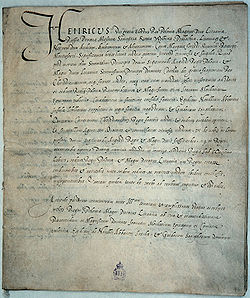

Golden age under Sigismund and Sigusmund II

The most prosperous period in the life of the Polish Jews began with the reign of Sigismund ISigismund I the Old

Sigismund I of Poland , of the Jagiellon dynasty, reigned as King of Poland and also as the Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until 1548...

(1506–1548). In 1507 the king informed the authorities of Lwów

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

that until further notice its Jewish citizens, in view of losses sustained by them, were to be left undisturbed in the possession of all their ancient privileges (Russko-Yevreiski Arkhiv, iii.79). His generous treatment of his physician, Jacob Isaac, whom he made a member of the nobility in 1507, testifies to his liberal views.

But while Sigismund himself was prompted by feelings of justice, his courtiers endeavored to turn to their personal advantage the conflicting interests of the different classes. Sigismund's second wife, Italian born Queen Bona

Bona Sforza

Bona Sforza was a member of the powerful Milanese House of Sforza. In 1518, she became the second wife of Sigismund I the Old, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and became the Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania.She was the third child of Gian Galeazzo Sforza and his wife...

, sold government positions for money; and her favorite, the Voivode (district governor) of Kraków, Piotr Kmita, accepted bribes from both sides, promising to further the interests of each at the Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

(Polish parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

) and with the king. In 1530 the Jewish question was the subject of heated discussions at the Sejm. There were some delegates who insisted on the just treatment of the Jews. On the other hand, some went so far as to demand the expulsion of the Jews from the country, while still others wished to curtail their commercial rights. The Sejm of 1538 in Piotrków Trybunalski

Piotrków Trybunalski

Piotrków Trybunalski is a city in central Poland with 80,738 inhabitants . It is situated in the Łódź Voivodeship , and previously was the capital of Piotrków Voivodeship...

elaborated a series of repressive measures against the Jews, who were prohibited from engaging in the collection of taxes and from leasing estates or government revenues, "it being against God's law that these people should hold honored positions among the Christians." The commercial pursuits of the Jews in the cities were placed under the control of the hostile magistrates, while in the villages Jews were forbidden to trade at all. The Sejm also revived the medieval ecclesiastical law compelling the Jews to wear a distinctive badge.

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus I was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the only son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548...

(1548–1572) followed in the main the tolerant policy of his father. He confirmed the ancient privileges of the Polish Jews, and considerably widened and strengthened the autonomy of their communities. By a decree of August 13, 1551, the Jews of Great Poland were again granted permission to elect a chief rabbi

Chief Rabbi

Chief Rabbi is a title given in several countries to the recognized religious leader of that country's Jewish community, or to a rabbinic leader appointed by the local secular authorities...

, who was to act as judge in all matters concerning their religious life. Jews refusing to acknowledge his authority were to be subject to a fine or to excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

; and those refusing to yield to the latter might be executed after a report of the circumstances had been made to the authorities. The property of the recalcitrants was to be confiscated and turned in to the crown treasury. The chief rabbi was exempted from the authority of the voivode and other officials, while the latter were obliged to assist him in enforcing the law among the Jews.

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

movement stimulated an anti-Jewish crusade by the Catholic clergy, who preached vehemently against all "heretic

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

s": Lutherans, Calvinists, and Jews. In 1550 the papal nuncio Alois Lipomano, who had been prominent as a persecutor of the Neo-Christians in Portugal, was delegated to Kraków to strengthen the Catholic spirit among the Polish nobility. He warned the King of the evils resulting from his tolerant attitude toward the various non-believers in the country. Seeing that the Polish nobles, among whom the Reformation had already taken strong root, paid but scant courtesy to his preachings, he initiated a blood libel

Blood libel

Blood libel is a false accusation or claim that religious minorities, usually Jews, murder children to use their blood in certain aspects of their religious rituals and holidays...

in the town of Sochaczew

Sochaczew

Sochaczew is a town in central Poland, with 38,300 inhabitants . Situated in the Masovian Voivodeship , previously in Skierniewice Voivodeship . It is the capital of Sochaczew County....

. Sigismund pointed out that papal bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

s had repeatedly asserted that all such accusations were without any foundation whatsoever; and he decreed that henceforth any Jew accused of having committed a murder for ritual purposes, or of having stolen a host, should be brought before his own court during the sessions of the Sejm. Sigismund II Augustus also granted autonomy to the Jews in the matter of communal administration and laid the foundation for the power of the Kahal

Kahal

Kahal is a moshav in the Galilee near Highway 85 in northern Israel. The moshav is a combined agricultural community. It lies at the border of the Upper Galilee and Lower Galilee, north of Lake Kinneret and just northwest of Tabgha. It belongs to the Mevo'ot HaHermon Regional Council and was...

.

In 1569 Union of Lublin

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin replaced the personal union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with a real union and an elective monarchy, since Sigismund II Augustus, the last of the Jagiellons, remained childless after three marriages. In addition, the autonomy of Royal Prussia was...

Lithuania strengthened its ties with Poland, as the previous personal union

Personal union

A personal union is the combination by which two or more different states have the same monarch while their boundaries, their laws and their interests remain distinct. It should not be confused with a federation which is internationally considered a single state...

was peacefully transformed into a unique federation

Federation

A federation , also known as a federal state, is a type of sovereign state characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions united by a central government...

of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

. The death of Sigismund Augustus (1572) and thus the termination of the Jagiellon dynasty

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty was a royal dynasty originating from the Lithuanian House of Gediminas dynasty that reigned in Central European countries between the 14th and 16th century...

necessitated the election

Election

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy operates since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the...

of his successor by the elective body of all the nobility (szlachta

Szlachta

The szlachta was a legally privileged noble class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great. In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of...

). During the interregnum

Interregnum

An interregnum is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order...

szlachta has passed the Warsaw Confederation

Warsaw Confederation

The Warsaw Confederation , an important development in the history of Poland and Lithuania that extended religious tolerance to nobility and free persons within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. , is considered the formal beginning of religious freedom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and...

act which guaranteed unprecedented religious tolerance to all citizens of the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, the neighboring states were deeply interested in the elections, each hoping to insure the choice of its own candidate. The pope was eager to assure the election of a Catholic, lest the influences of the Reformation should become predominant in Poland. Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici was an Italian noblewoman who was Queen consort of France from 1547 until 1559, as the wife of King Henry II of France....

was laboring energetically for the election of her son Henry of Anjou. But in spite of all the intrigues at the various courts, the deciding factor in the election was the influence of Solomon Ashkenazi, then in charge of the foreign affairs

Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs is an American magazine and website on international relations and U.S. foreign policy published since 1922 by the Council on Foreign Relations six times annually...

of Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. Henry of Anjou was elected, which was of deep concern to the liberal Poles and the Jews, as he was the infamous mastermind of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre

St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations, followed by a wave of Roman Catholic mob violence, both directed against the Huguenots , during the French Wars of Religion...

. Therefore Polish szlachta forced him to sign the Henrician articles

Henrician Articles

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles were a permanent contract that stated the fundamental principles of governance and constitutional law in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the form of 21 Articles written and adopted by the nobility in 1573 at the town of Kamień, near Warsaw,...

and pacta conventa

Pacta conventa (Poland)

Pacta conventa was a contractual agreement, from 1573 to 1764 entered into between the "Polish nation" and a newly-elected king upon his "free election" to the throne.The pacta conventa affirmed the king-elect's pledge to respect the laws of the...

, guarantying the religious tolerance in Poland, as a condition of acceptance of the throne (those documents would be subsequently signed by every other elected Polish king). However, Henry soon secretly fled to France after a reign in Poland of only a few months, in order to succeed his deceased brother Charles IX

Charles IX of France

Charles IX was King of France, ruling from 1560 until his death. His reign was dominated by the Wars of Religion. He is best known as king at the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre.-Childhood:...

on the French throne.

Jewish learning and culture during the early Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Yeshivas were established, under the direction of the rabbis, in the more prominent communities. Such schools were officially known as gymnasiaGymnasium (school)

A gymnasium is a type of school providing secondary education in some parts of Europe, comparable to English grammar schools or sixth form colleges and U.S. college preparatory high schools. The word γυμνάσιον was used in Ancient Greece, meaning a locality for both physical and intellectual...

, and their rabbi-principals as rector

Rector

The word rector has a number of different meanings; it is widely used to refer to an academic, religious or political administrator...

s. Important yeshivots existed in Kraków, Poznań, and other cities. Jewish printing establishments came into existence in the first quarter of the 16th century. In 1530 a Hebrew

Hebrew language

Hebrew is a Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Culturally, is it considered by Jews and other religious groups as the language of the Jewish people, though other Jewish languages had originated among diaspora Jews, and the Hebrew language is also used by non-Jewish groups, such...

Pentateuch (Torah

Torah

Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five books of the bible—Genesis , Exodus , Leviticus , Numbers and Deuteronomy Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five...

) was printed in Kraków; and at the end of the century the Jewish printing-houses of that city and Lublin

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth largest city in Poland. It is the capital of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 350,392 . Lublin is also the largest Polish city east of the Vistula river...

issued a large number of Jewish books, mainly of a religious character. The growth of Talmud

Talmud

The Talmud is a central text of mainstream Judaism. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs and history....

ic scholarship in Poland was coincident with the greater prosperity of the Polish Jews; and because of their communal autonomy educational development was wholly one-sided and along Talmudic lines. Exceptions are recorded, however, where Jewish youth sought secular instruction in the European universities. The learned rabbis became not merely expounders of the Law, but also spiritual advisers, teachers, judges, and legislators; and their authority compelled the communal leaders to make themselves familiar with the abstruse questions of Jewish law

Halakha

Halakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

. Polish Jewry found its views of life shaped by the spirit of Talmudic and rabbinical literature, whose influence was felt in the home, in school, and in the synagogue.

In the first half of the 16th century the seeds of Talmudic learning had been transplanted to Poland from Bohemia, particularly from the school of Jacob Pollak

Jacob Pollak

Rabbi Jacob Pollak was the founder of the Polish method of halakic and Talmudic study known as the Pilpul; born about 1460; died at Lublin in 1541...

, the creator of Pilpul

Pilpul

Pilpul refers to a method of studying the Talmud through intense textual analysis in attempts to either explain conceptual differences between various halakhic rulings or to reconcile any apparent contradictions presented from various readings of different texts.Pilpul has entered English as a...

("sharp reasoning"). Shalom Shachna

Shalom Shachna

Shalom Shachna was a rabbi and Talmudist, and Rosh Yeshiva of several great Acharonim including Moses Isserles, who was also his son-in-law.-Biography:...

(c. 1500–1558), a pupil of Pollak, is counted among the pioneers of Talmudic learning in Poland. He lived and died in Lublin, where he was the head of the yeshivah which produced the rabbinical celebrities of the following century. Shachna's son Israel became rabbi of Lublin on the death of his father, and Shachna's pupil Moses Isserles

Moses Isserles

Moses Isserles, also spelled Moshe Isserlis, , was an eminent Ashkenazic rabbi, talmudist, and posek, renowned for his fundamental work of Halakha , entitled ha-Mapah , an inline commentary on the Shulkhan Aruch...

(known as the ReMA) (1520–1572) achieved an international reputation among the Jews as the co-author of the Shulkhan Arukh, (the "Code of Jewish Law"). His contemporary and correspondent Solomon Luria

Solomon Luria

Solomon Luria was one of the great Ashkenazic poskim and teachers of his time. He is known for his work of Halakha, Yam Shel Shlomo, and his Talmudic commentary Chochmat Shlomo...

(1510–1573) of Lublin also enjoyed a wide reputation among his coreligionists; and the authority of both was recognized by the Jews throughout Europe. Among the famous pupils of Isserles should be mentioned David Gans

David Gans

----David ben Solomon ben Seligman Gans was a Jewish mathematician, historian, astronomer, astrologer, and is best known for the works Tzemach David and Nechmad ve'naim.- Early life :...

and Mordecai Jaffe, the latter of whom studied also under Luria. Another distinguished rabbinical scholar of that period was Eliezer b. Elijah Ashkenazi (1512–1585) of Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

. His Ma'ase ha-Shem (Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, 1583) is permeated with the spirit of the moral philosophy of the Sephardic school, but is extremely mystical. At the end of the work he attempts to forecast the coming of the Jewish Messiah

Jewish Messiah

Messiah, ; mashiah, moshiah, mashiach, or moshiach, is a term used in the Hebrew Bible to describe priests and kings, who were traditionally anointed with holy anointing oil as described in Exodus 30:22-25...

in 1595, basing his calculations on the Book of Daniel

Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a book in the Hebrew Bible. The book tells of how Daniel, and his Judean companions, were inducted into Babylon during Jewish exile, and how their positions elevated in the court of Nebuchadnezzar. The court tales span events that occur during the reigns of Nebuchadnezzar,...

. Such Messianic dreams found a receptive soil in the unsettled religious conditions of the time. The new sect of Socinians or Unitarians

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

, which denied the Trinity

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity defines God as three divine persons : the Father, the Son , and the Holy Spirit. The three persons are distinct yet coexist in unity, and are co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial . Put another way, the three persons of the Trinity are of one being...

and which, therefore, stood near to Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

, had among its leaders Simon Budny, the translator of the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

into Polish, and the priest Martin Czechowic. Heated religious disputations were common, and Jewish scholars participated in them. At the same time, the Kabbalah

Kabbalah

Kabbalah/Kabala is a discipline and school of thought concerned with the esoteric aspect of Rabbinic Judaism. It was systematized in 11th-13th century Hachmei Provence and Spain, and again after the Expulsion from Spain, in 16th century Ottoman Palestine...

had become entrenched under the protection of Rabbinism

Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism or Rabbinism has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Talmud...

; and such scholars as Mordecai Jaffe and Yoel Sirkis

Yoel Sirkis

Joel ben Samuel Sirkis also known as the Bach - an abbreviation of his magnum opus, Bayit Chadash - was a prominent Jewish posek and halakhist. He lived in central Europe and held rabbinical positions in Belz, Brest-Litovsk and Kraków from 1561-1640.-Biography:Sirkis was born in Lublin in 1561...

devoted themselves to its study. The mystic

Mysticism

Mysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

speculations of the kabalists prepared the ground for Sabbatianism

Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi, , was a Sephardic Rabbi and kabbalist who claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah. He was the founder of the Jewish Sabbatean movement...

, and the Jewish masses were rendered even more receptive by the great disasters that over-took the Jews of Poland during the middle of the 17th century such as the Cossack

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

Chmielnicki Uprising against Poland during 1648–1654.

The beginning of decline

Stephen Báthory (1576–1586) was now elected king of Poland; and he proved both a tolerant ruler and a friend of the Jews. On February 10, 1577, he sent orders to the magistrate of PoznaPózna

Późna is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Gubin, within Krosno Odrzańskie County, Lubusz Voivodeship, in western Poland, close to the German border....

directing him to prevent class conflicts, and to maintain order in the city. His orders were, however, of no avail. Three months after his manifesto a riot occurred in Poznań. Political and economic events in the course of the 16th century forced the Jews to establish a more compact communal organization, and this separated them from the rest of the urban population; indeed, although with few exceptions they did not live in separate ghettos, they were nevertheless sufficiently isolated from their Christian neighbors to be regarded as strangers. They resided in the towns and cities, but had little to do with municipal administration, their own affairs being managed by the rabbis, the elders, and the dayyanim or religious judges. These conditions contributed to the strengthening of the Kahal organizations. Conflicts and disputes, however, became of frequent occurrence, and led to the convocation of periodical rabbinical congresses, which were the nucleus of the central institution known in Poland, from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 18th century, as the Council of Four Lands

Council of Four Lands

The Council of Four Lands in Lublin, Poland was the central body of Jewish authority in Poland from 1580 to 1764. Seventy delegates from local kehillot met to discuss taxation and other issues important to the Jewish community...

.

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent was the 16th-century Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church. It is considered to be one of the Church's most important councils. It convened in Trent between December 13, 1545, and December 4, 1563 in twenty-five sessions for three periods...

spread throughout Europe finally reached Poland. The Jesuits and counterreformation found a powerful protector in Báthory's successor, Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, a monarch of the united Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1587 to 1632, and King of Sweden from 1592 until he was deposed in 1599...

(1587–1632). Under his rule the "Golden Freedom" of the Polish szlachta gradually became perverted; government by the liberum veto

Liberum veto

The liberum veto was a parliamentary device in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It allowed any member of the Sejm to force an immediate end to the current session and nullify any legislation that had already been passed at the session by shouting Nie pozwalam! .From the mid-16th to the late 18th...

undermined the authority of the Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

; and the stage was set for the degeneration of unique democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

and religious tolerance of the Commonwealth into anarchy and intolerance. However, the dying spirit of the republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

(Rzeczpospolita

Rzeczpospolita

Rzeczpospolita is a traditional name of the Polish State, usually referred to as Rzeczpospolita Polska . It comes from the words: "rzecz" and "pospolita" , literally, a "common thing". It comes from latin word "respublica", meaning simply "republic"...

) was still strong enough to check somewhat the destructive power of Jesuitism, which under an absolute monarchy, like those in Western Europe, have led to drastic anti-Jewish measures similar to those that had been taken in Spain. However in Poland Jesuits were limited only to propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

. Thus while the Catholic clergy was the mainstay of the anti-Jewish forces, the king, forced by the Protestant szlachta, remained at least in semblance the defender of the Jews. Still, the false accusations of ritual murder against the Jews recurred with growing frequency, and assumed an "ominous inquisitional character." The papal bulls and the ancient charters of privilege proved generally of little avail as protection. Uneasy conditions persisted during the reign of Sigismund's son, Wladislaus IV Vasa (1632–1648).

Cossacks' uprising

In 1648 the Commonwealth was devastated by the several conflicts, in which the Commonwealth lost over a third of its populations (over 3 million people), and Jewish losses were counted in hundreds of thousands. First, the Chmielnicki Uprising when Bohdan KhmelnytskyBohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

's Cossack

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

s massacred tens of thousands of Jews and Poles in the eastern and southern areas he controlled (today's Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

). It is recorded that Chmielncki told the people that the Poles had sold them as slaves "into the hands of the accursed Jews". The precise number of dead may never be known, but the decrease of the Jewish population during that period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, which also includes emigration, deaths from diseases and jasyr (captivity in the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

).

Then the incompetent politics of the elected House of Vasa

House of Vasa