John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry

Encyclopedia

John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry GCVO (20 July 184431 January 1900) was a Scottish

nobleman, remembered for lending his name and patronage to the "Marquess of Queensberry rules

" that formed the basis of modern boxing

, for his outspoken atheism

, and for his role in the downfall of author and playwright Oscar Wilde

.

, Italy, the eldest son of Scottish Conservative Party politician Archibald, Viscount Drumlanrig

, who was the heir of the 7th Marquess of Queensberry. He was briefly styled Viscount Drumlanrig following his father's succession in 1856, and on his father's death in 1858 he inherited the Marquessate of Queensberry

. The 9th marquess was educated at the Royal Naval College

in Greenwich

, London, becoming a midshipman

at the age of twelve and a lieutenant

in the navy

at fifteen. In 1864 he entered Magdalene College

, Cambridge

, which he left two years later without taking a degree. He married Sibyl Montgomery in 1866. They had four sons and a daughter, but divorced in 1887. Queensberry married Ethel Weeden in 1893, but the marriage was annulled the following year. He died in London, aged 55, nearly a year before Oscar Wilde's death. Although he wrote a poem starting with the words "When I am dead cremate me," he was buried in Scotland.

His eldest son and heir apparent was Francis, Viscount Drumlanrig, who was rumoured to have been engaged in a relationship with the Liberal Prime Minister, Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

. He died unmarried and without issue.

Douglas' second son, Lord Percy Douglas (1868–1920), succeeded to the peerage instead. Lord Alfred "Bosie" Douglas

, the third son, was the close friend and reputed lover of the famous author and poet Oscar Wilde

. Douglas' efforts to end their relationship led to his famous dispute with Wilde and the latter's bankruptcy and exile.

Queensberry was a patron of sport and a noted boxing

Queensberry was a patron of sport and a noted boxing

enthusiast. In 1866 he was one of the founders of the Amateur Athletic Club, now the Amateur Athletic Association of England

, one of the first groups that did not require amateur athletes to belong to the upper-classes in order to compete. The following year the Club published a set of twelve rules for conducting boxing matches. The rules had been drawn up by John Graham Chambers

but appeared under Queensberry's sponsorship and are universally known at the "Marquess of Queensberry rules

". Queensberry, a keen rider, was also active in fox hunting

and owned several successful race horses

.

to sit in the House of Lords

as a representative peer

. He served as such until 1880, when he was again nominated but refused to take the religious oath of allegiance to the Sovereign. An outspoken atheist

, he declared that he would not participate in any "Christian tomfoolery" and that his word should suffice. As a consequence neither he nor Charles Bradlaugh

, who had also refused to take the oath after being elected to the House of Commons

, were allowed to take their seats in Parliament

. This prompted an apology from the new Prime Minister

, William Gladstone

. Bradlaugh was re-elected four times by the constituents of Northampton

until he was finally allowed to take his seat in 1886, but Queensberry was never again sent to Parliament by the Scottish nobles.

In 1881, Queensberry accepted the presidency of the British Secular Union, a group that had broken away in 1877 from Bradlaugh's National Secular Society

. That year he published a long philosophical poem, The Spirit of the Matterhorn

, which he had written in Zermatt

in 1873 in an attempt to articulate his humanistic

views. In 1882, he was ejected from the theatre after loudly interrupting a performance of the play The Promise of May by Lord Tennyson

, the Poet Laureate

, because it included a villainous atheist in its cast of characters. Under the auspices of the British Secular Union, Queensberry wrote a pamphlet entitled The Religion of Secularism and the Perfectibility of Man. The Union, always small, ceased to function in 1884.

His divorces, atheism, and association with the boxing world made Queensberry an unpopular figure in London

high society. In 1893 his eldest son, Francis, Viscount Drumlanrig, was created Baron Kelhead in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

, thus giving the son an automatic seat in the House of Lords, from which the father was excluded. This caused a bitter dispute between Queensberry and his son, and also between Queensberry and Lord Rosebery

, the patron who had promoted Lord Drumlanrig's ennoblement and who shortly thereafter became Prime Minister. Drumlanrig was reported to have been killed in a hunting accident in 1894, but his death may have been a suicide.

Queensberry sold the family seat of Kinmount

in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, an action which further alienated him from his family.

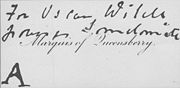

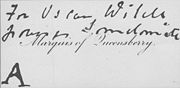

In March 1895, Queensberry was arrested and sued for criminal libel

In March 1895, Queensberry was arrested and sued for criminal libel

by Oscar Wilde

, whom he had publicly accused of "posing [as a] somdomite

" (sic). Libel charges could be brought as homosexuality was a crime at the time. Queensberry made the allegation because he was angered by Wilde's apparent ongoing homosexual relationship with his son, Lord Alfred Douglas

.

Queensberry's lawyers, headed by barrister Edward Carson, portrayed Wilde as a vicious older man who seduced innocent young boys into a life of degenerate homosexuality. Wilde dropped the libel case when Queensberry's lawyers informed the court that they intended to call several male prostitutes as witnesses to testify that they had had sex with Wilde. According to the Libel Act 1843

, proving the truth of the accusation and a public interest in its exposure was a defense against a libel charge, and Wilde's lawyers concluded that the prostitutes' testimony was likely to do that.

Queensberry won a counterclaim against Wilde for the considerable expenses he had incurred on lawyers and private detectives in organising his defence. Wilde was left bankrupt; his assets were seized and sold at auction to pay the claim. Queensberry then sent the evidence collected by his detectives to Scotland Yard, which resulted in charges of sodomy

and "gross indecency

" against Wilde, who was convicted of gross indecency under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885

and sentenced to two years' hard labour. His reputation destroyed, Wilde went into exile in France

and died at the Hotel d'Alsace in Paris.

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

nobleman, remembered for lending his name and patronage to the "Marquess of Queensberry rules

Marquess of Queensberry rules

The Marquess of Queensberry rules is a code of generally accepted rules in the sport of boxing. They were named so because John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry publicly endorsed the code, although they were written by a sportsman named John Graham Chambers. The code of rules on which modern...

" that formed the basis of modern boxing

Boxing

Boxing, also called pugilism, is a combat sport in which two people fight each other using their fists. Boxing is supervised by a referee over a series of between one to three minute intervals called rounds...

, for his outspoken atheism

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

, and for his role in the downfall of author and playwright Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

.

Biography

Douglas was born in FlorenceFlorence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

, Italy, the eldest son of Scottish Conservative Party politician Archibald, Viscount Drumlanrig

Archibald Douglas, 8th Marquess of Queensberry

Archibald William Douglas, 8th Marquess of Queensberry PC , styled Viscount Drumlanrig between 1837 and 1856, was a Scottish Conservative Party politician...

, who was the heir of the 7th Marquess of Queensberry. He was briefly styled Viscount Drumlanrig following his father's succession in 1856, and on his father's death in 1858 he inherited the Marquessate of Queensberry

Marquess of Queensberry

Marquess of Queensberry is a title in the peerage of Scotland. The title has been held since its creation in 1682 by a member of the Douglas family...

. The 9th marquess was educated at the Royal Naval College

Old Royal Naval College

The Old Royal Naval College is the architectural centrepiece of Maritime Greenwich, a World Heritage Site in Greenwich, London, described by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation as being of “outstanding universal value” and reckoned to be the “finest and most...

in Greenwich

Greenwich

Greenwich is a district of south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich.Greenwich is best known for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich Meridian and Greenwich Mean Time...

, London, becoming a midshipman

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer cadet, or a commissioned officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Kenya...

at the age of twelve and a lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

in the navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

at fifteen. In 1864 he entered Magdalene College

Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England.The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary Magdalene...

, Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

, which he left two years later without taking a degree. He married Sibyl Montgomery in 1866. They had four sons and a daughter, but divorced in 1887. Queensberry married Ethel Weeden in 1893, but the marriage was annulled the following year. He died in London, aged 55, nearly a year before Oscar Wilde's death. Although he wrote a poem starting with the words "When I am dead cremate me," he was buried in Scotland.

His eldest son and heir apparent was Francis, Viscount Drumlanrig, who was rumoured to have been engaged in a relationship with the Liberal Prime Minister, Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, KG, PC was a British Liberal statesman and Prime Minister. Between the death of his father, in 1851, and the death of his grandfather, the 4th Earl, in 1868, he was known by the courtesy title of Lord Dalmeny.Rosebery was a Liberal Imperialist who...

. He died unmarried and without issue.

Douglas' second son, Lord Percy Douglas (1868–1920), succeeded to the peerage instead. Lord Alfred "Bosie" Douglas

Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas , nicknamed Bosie, was a British author, poet and translator, better known as the intimate friend and lover of the writer Oscar Wilde...

, the third son, was the close friend and reputed lover of the famous author and poet Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

. Douglas' efforts to end their relationship led to his famous dispute with Wilde and the latter's bankruptcy and exile.

Contributions to sports

Boxing

Boxing, also called pugilism, is a combat sport in which two people fight each other using their fists. Boxing is supervised by a referee over a series of between one to three minute intervals called rounds...

enthusiast. In 1866 he was one of the founders of the Amateur Athletic Club, now the Amateur Athletic Association of England

Amateur Athletic Association of England

The Amateur Athletic Association of England or AAA is the oldest national governing body for athletics in the world, having been established on 24 April 1880. In the past, it has effectively overseen athletics throughout Britain. Now, it supports regional athletic clubs and works to develop...

, one of the first groups that did not require amateur athletes to belong to the upper-classes in order to compete. The following year the Club published a set of twelve rules for conducting boxing matches. The rules had been drawn up by John Graham Chambers

John Graham Chambers

John Graham Chambers was a Welsh sportsman. He rowed for Cambridge, founded inter-varsity sports, became English Champion walker, coached four winning Boat-Race crews, devised the Queensberry Rules, staged the Cup Final and the Thames Regatta, instituted championships for billiards, boxing,...

but appeared under Queensberry's sponsorship and are universally known at the "Marquess of Queensberry rules

Marquess of Queensberry rules

The Marquess of Queensberry rules is a code of generally accepted rules in the sport of boxing. They were named so because John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry publicly endorsed the code, although they were written by a sportsman named John Graham Chambers. The code of rules on which modern...

". Queensberry, a keen rider, was also active in fox hunting

Fox hunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase, and sometimes killing of a fox, traditionally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds, and a group of followers led by a master of foxhounds, who follow the hounds on foot or on horseback.Fox hunting originated in its current...

and owned several successful race horses

Horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian sport that has a long history. Archaeological records indicate that horse racing occurred in ancient Babylon, Syria, and Egypt. Both chariot and mounted horse racing were events in the ancient Greek Olympics by 648 BC...

.

Political career

In 1872, Queensberry was chosen by the Peers of ScotlandPeerage of Scotland

The Peerage of Scotland is the division of the British Peerage for those peers created in the Kingdom of Scotland before 1707. With that year's Act of Union, the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England were combined into the Kingdom of Great Britain, and a new Peerage of Great Britain was...

to sit in the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

as a representative peer

Representative peer

In the United Kingdom, representative peers were those peers elected by the members of the Peerage of Scotland and the Peerage of Ireland to sit in the British House of Lords...

. He served as such until 1880, when he was again nominated but refused to take the religious oath of allegiance to the Sovereign. An outspoken atheist

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

, he declared that he would not participate in any "Christian tomfoolery" and that his word should suffice. As a consequence neither he nor Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh was a political activist and one of the most famous English atheists of the 19th century. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866.-Early life:...

, who had also refused to take the oath after being elected to the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, were allowed to take their seats in Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

. This prompted an apology from the new Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

, William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

. Bradlaugh was re-elected four times by the constituents of Northampton

Northampton

Northampton is a large market town and local government district in the East Midlands region of England. Situated about north-west of London and around south-east of Birmingham, Northampton lies on the River Nene and is the county town of Northamptonshire. The demonym of Northampton is...

until he was finally allowed to take his seat in 1886, but Queensberry was never again sent to Parliament by the Scottish nobles.

In 1881, Queensberry accepted the presidency of the British Secular Union, a group that had broken away in 1877 from Bradlaugh's National Secular Society

National Secular Society

The National Secular Society is a British campaigning organisation that promotes secularism and the separation of church and state. It holds that no-one should gain advantage or disadvantage because of their religion or lack of religion. It was founded by Charles Bradlaugh in 1866...

. That year he published a long philosophical poem, The Spirit of the Matterhorn

Matterhorn

The Matterhorn , Monte Cervino or Mont Cervin , is a mountain in the Pennine Alps on the border between Switzerland and Italy. Its summit is 4,478 metres high, making it one of the highest peaks in the Alps. The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers, face the four compass points...

, which he had written in Zermatt

Zermatt

Zermatt is a municipality in the district of Visp in the German-speaking section of the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It has a population of about 5,800 inhabitants....

in 1873 in an attempt to articulate his humanistic

Secular humanism

Secular Humanism, alternatively known as Humanism , is a secular philosophy that embraces human reason, ethics, justice, and the search for human fulfillment...

views. In 1882, he was ejected from the theatre after loudly interrupting a performance of the play The Promise of May by Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular poets in the English language....

, the Poet Laureate

Poet Laureate

A poet laureate is a poet officially appointed by a government and is often expected to compose poems for state occasions and other government events...

, because it included a villainous atheist in its cast of characters. Under the auspices of the British Secular Union, Queensberry wrote a pamphlet entitled The Religion of Secularism and the Perfectibility of Man. The Union, always small, ceased to function in 1884.

His divorces, atheism, and association with the boxing world made Queensberry an unpopular figure in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

high society. In 1893 his eldest son, Francis, Viscount Drumlanrig, was created Baron Kelhead in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

Peerage of the United Kingdom

The Peerage of the United Kingdom comprises most peerages created in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the Act of Union in 1801, when it replaced the Peerage of Great Britain...

, thus giving the son an automatic seat in the House of Lords, from which the father was excluded. This caused a bitter dispute between Queensberry and his son, and also between Queensberry and Lord Rosebery

Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, KG, PC was a British Liberal statesman and Prime Minister. Between the death of his father, in 1851, and the death of his grandfather, the 4th Earl, in 1868, he was known by the courtesy title of Lord Dalmeny.Rosebery was a Liberal Imperialist who...

, the patron who had promoted Lord Drumlanrig's ennoblement and who shortly thereafter became Prime Minister. Drumlanrig was reported to have been killed in a hunting accident in 1894, but his death may have been a suicide.

Queensberry sold the family seat of Kinmount

Kinmount House

Kinmount House is a 19th-century country house in Dumfries and Galloway, south Scotland. It is located west of Annan in the parish of Cummertrees. The house was designed by Sir Robert Smirke for the Marquess of Queensberry, and completed in 1820...

in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, an action which further alienated him from his family.

Dispute with Oscar Wilde

Criminal libel

Criminal libel is a legal term, of English origin, which may be used with one of two distinct meanings, in those common law jurisdictions where it is still used....

by Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

, whom he had publicly accused of "posing [as a] somdomite

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

" (sic). Libel charges could be brought as homosexuality was a crime at the time. Queensberry made the allegation because he was angered by Wilde's apparent ongoing homosexual relationship with his son, Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas , nicknamed Bosie, was a British author, poet and translator, better known as the intimate friend and lover of the writer Oscar Wilde...

.

Queensberry's lawyers, headed by barrister Edward Carson, portrayed Wilde as a vicious older man who seduced innocent young boys into a life of degenerate homosexuality. Wilde dropped the libel case when Queensberry's lawyers informed the court that they intended to call several male prostitutes as witnesses to testify that they had had sex with Wilde. According to the Libel Act 1843

Libel Act 1843

The Libel Act 1843, commonly known as Lord Campbell's Libel Act, was a Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It enacted several important codifications of and modifications to the common law tort of libel....

, proving the truth of the accusation and a public interest in its exposure was a defense against a libel charge, and Wilde's lawyers concluded that the prostitutes' testimony was likely to do that.

Queensberry won a counterclaim against Wilde for the considerable expenses he had incurred on lawyers and private detectives in organising his defence. Wilde was left bankrupt; his assets were seized and sold at auction to pay the claim. Queensberry then sent the evidence collected by his detectives to Scotland Yard, which resulted in charges of sodomy

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

and "gross indecency

Gross indecency

Gross indecency is a UK and Canadian legal term of art which was used in the definition of the following criminal offences:*Gross indecency between men, contrary to section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 and later contrary to section 13 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956.*Indecency with a...

" against Wilde, who was convicted of gross indecency under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885

Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 , or "An Act to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes", was the latest in a 25-year series of legislation in the United Kingdom beginning with the Offences against the Person Act 1861 that...

and sentenced to two years' hard labour. His reputation destroyed, Wilde went into exile in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and died at the Hotel d'Alsace in Paris.