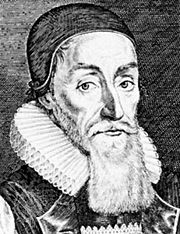

Joseph Hall (English Bishop and satyrist)

Encyclopedia

Thomas Fuller

Thomas Fuller

Thomas Fuller was an English churchman and historian. He is now remembered for his writings, particularly his Worthies of England, published after his death...

wrote:

- "He was commonly called our English Seneca, for the purenesse, plainnesse, and fulnesse of his style. Not unhappy at Controversies, more happy at Comments, very good in his Characters, better in his Sermons, best of all in his Meditations."

His relationship to the stoicism

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in the early . The Stoics taught that destructive emotions resulted from errors in judgment, and that a sage, or person of "moral and intellectual perfection," would not suffer such emotions.Stoics were concerned...

of the classical age, exemplified by Seneca the Younger

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and in one work humorist, of the Silver Age of Latin literature. He was tutor and later advisor to emperor Nero...

, is still debated, with the importance of neo-stoicism and the influence of Justus Lipsius

Justus Lipsius

Justus Lipsius was a Southern-Netherlandish philologist and humanist. Lipsius wrote a series of works designed to revive ancient Stoicism in a form that would be compatible with Christianity. The most famous of these is De Constantia...

to his work being contested, in contrast to Christian morality.

Early life

He was born at Bristow Park, near Ashby-de-la-ZouchAshby-de-la-Zouch

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, — Zouch being pronounced "Zoosh" — often shortened to Ashby, is a small market town and civil parish in North West Leicestershire, England, within the National Forest. It is twinned with Pithiviers in north-central France....

, Leicestershire. Joseph Hall came of a large family, being one of twelve children born to John Hall, agent in Ashby-de-la-Zouch for Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon

Sir Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, KG KB was the eldest son of Francis Hastings, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon and Catherine Pole.-Ancestry:...

. Hall's mother, Winifred Bambridge, was a Calvinist close to Anthony Gilby

Anthony Gilby

Anthony Gilby was an English clergyman, known as a radical Puritan and Geneva Bible translator.He was born in Lincolnshire, and was educated at Christ's College, Cambridge, graduating in 1535.-Early life:...

. Her son later compared her to St Monica

Monica of Hippo

Saint Monica is a Christian saint and the mother of Augustine of Hippo, who wrote extensively of her virtues and his life with her in his Confessions.-Life:...

:

- "What day did she pass without a large task of private devotion? whence she would still come forth, with a countenance of undissembled mortification. Never any lips have read to me such feeling lectures of piety; neither have I known any soul that more accurately practised them than her own."

Joseph Hall received his early education at the local Ashby Grammar School, founded by his father's patron the Earl, and was later sent (1589) to Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay on the site of a Dominican friary...

, where Anthony Gilby's son Nathaniel was a Fellow and advocated this course. The college was Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

in tone, and Hall was undoubtedly under Calvinist influence in his youth. After some early setbacks (his father found it difficult to pay for a university education and nearly recalled him after the first two years), Hall's academic career was a great success. He was chosen for two years in succession to read the public lecture on rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

in the schools and in 1595 became fellow of his college.

Priest

Having taken holy ordersHoly Orders

The term Holy Orders is used by many Christian churches to refer to ordination or to those individuals ordained for a special role or ministry....

, Hall was offered the mastership of Blundell's School

Blundell's School

Blundell's School is a co-educational day and boarding independent school located in the town of Tiverton in the county of Devon, England. The school was founded in 1604 by the will of Peter Blundell, one of the richest men in England at the time, and relocated to its present location on the...

, Tiverton, but he refused it in favour of the living of Hawstead, Suffolk, to which he was presented (1601) by Sir Robert Drury. The appointment was not wholly satisfactory: in his parish Hall had an opponent in a Mr Lilly, whom he describes as a "witty and bold atheist", he had to find money to make his house habitable, and he felt that his patron Sir Robert underpaid him. Nevertheless in 1603, he married Elizabeth Wynniff of Brettenham, Suffolk.

In 1605, Hall travelled abroad for the first time when he accompanied Sir Edmund Bacon

Edmund Bacon

Edmund Norwood Bacon was a noted American urban planner, architect, educator and author. During his tenure as the Executive Director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970, his visions shaped today's Philadelphia, the city in which he was born, to the extent that he is...

on an embassy to Spa

Spa

The term spa is associated with water treatment which is also known as balneotherapy. Spa towns or spa resorts typically offer various health treatments. The belief in the curative powers of mineral waters goes back to prehistoric times. Such practices have been popular worldwide, but are...

, with the special aim, he says, of acquainting himself with the state and practice of the Romish Church. At Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

, he disputed at the Jesuit college on the authentic character of modern miracles, until his patron at length asked him to stop.

His devotional writings had attracted the notice of Henry, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales was the elder son of King James I & VI and Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and Frederick II of Denmark. Prince Henry was widely seen as a bright and promising heir to his father's throne...

, who made him one of his chaplains (1608). Hall preached officially on the tenth anniversary of King James's

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

accession in 1613, with an assessment in An Holy Panegyrick of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

flattering to the king.

In 1612, Edward Denny

Edward Denny, 1st Earl of Norwich

Edward Denny, 1st Earl of Norwich , known as The Lord Denny between 1604 and 1627, was an English courtier, Member of Parliament and peer.-Life:...

gave him the curacy of Waltham-Holy-Cross, Essex, and, in the same year, he received the degree of D.D.. Later he received the prebend

Prebendary

A prebendary is a post connected to an Anglican or Catholic cathedral or collegiate church and is a type of canon. Prebendaries have a role in the administration of the cathedral...

of Willenhall

Willenhall

Willenhall is a town in the Black Country area of the West Midlands of England, with a population of approximately 40,000. It is situated between Wolverhampton and Walsall, historically in the county of Staffordshire...

in the collegiate church

Collegiate church

In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons; a non-monastic, or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by a dean or provost...

of Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands, England. For Eurostat purposes Walsall and Wolverhampton is a NUTS 3 region and is one of five boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "West Midlands" NUTS 2 region...

, and, in 1616, he accompanied James Hay, Lord Doncaster to France, where he was sent to congratulate Louis XIII

Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1610 to 1643.Louis was only eight years old when he succeeded his father. His mother, Marie de Medici, acted as regent during Louis' minority...

on his marriage, but Hall was compelled by illness to return. In his absence, the king nominated him Dean of Worcester

Dean of Worcester

The Dean of Worcester is the head of the Chapter of Worcester Cathedral in Worcester, England. The most current Dean is the Very Rev Peter Gordon Atkinson who lives at The Deanery, College Green, Worcester.-List of Deans:...

, and, in 1617, he accompanied James

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

to Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, where he defended the Five Articles of Perth

Five Articles of Perth

The Five Articles of Perth was an attempt by King James VI of Scotland to impose practices on the Church of Scotland in an attempt to integrate it with the episcopalian Church of England...

, five points of ceremonial which the king desired to impose upon the Scots.

In the next year he was chosen as one of the English deputies at the Synod of Dort

Synod of Dort

The Synod of Dort was a National Synod held in Dordrecht in 1618-1619, by the Dutch Reformed Church, to settle a divisive controversy initiated by the rise of Arminianism. The first meeting was on November 13, 1618, and the final meeting, the 154th, was on May 9, 1619...

. But he fell ill, and was replaced by Thomas Goad

Thomas Goad

Thomas Goad was an English clergyman, controversial writer, and rector of Hadleigh, Suffolk. A participant at the Synod of Dort, he changed his views there from Calvinist to Arminian, against the sense of the meeting.-Life:...

. At the time (1621–2) when Marco Antonio de Dominis

Marco Antonio de Dominis

Marco Antonio Dominis was a Dalmatian ecclesiastic, apostate, and man of science.-Early life:He was born on the island of Rab, Croatia, off the coast of Dalmatia...

announced his intention to return to Rome, after a stay in England, Hall wrote to try to dissuade him, without success. In a long-unpublished reply (printed 1666) De Dominis justified himself in a comprehensive statement of his mission against schism

Schism (religion)

A schism , from Greek σχίσμα, skhísma , is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization or movement religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a break of communion between two sections of Christianity that were previously a single body, or to a division within...

and its limited results, hampered by Dort and a lack of freedom under James I.

Bishop

In a sermon Columba Noæ of February 1624 (1623 O.S.) to Convocation, he gave a list or personal panorama of leading theologians of the Church of England. In the same year he also refused the see of Gloucester: at the time English delegates to Dort were receiving preferment, since King James approved of the outcome. Hall was then involved as a mediator, taking an active part in the Arminian and Calvinist controversy in the English church, and trying to get other clergy to accept Dort. In 1627, he became Bishop of ExeterBishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. The incumbent usually signs his name as Exon or incorporates this in his signature....

.

In spite of his Calvinistic opinions, he maintained that to acknowledge the errors which had arisen in the Catholic Church did not necessarily imply disbelief in her catholicity, and that the Church of England having repudiated these errors should not deny the claims of the Roman Catholic Church on that account. This view commended itself to Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

and his episcopal advisers; even if Hall, with John Davenant

John Davenant

John Davenant was an English academic and bishop of Salisbury from 1621.-Life:He was educated at Queens’ College, Cambridge, elected a fellow there in 1597, and was its President from 1614 to 1621...

and Thomas Morton

Thomas Morton (bishop)

Thomas Morton was an English churchman, bishop of several dioceses.-Early life:Morton was born in York on 20 March 1564. He was brought up and grammar school educated in the city and nearby Halifax. In 1582 he became a pensioner at St John's College, Cambridge from which he graduated with a BA in...

, was considered a likely die-hard by Richard Montagu

Richard Montagu

Richard Montagu was an English cleric and prelate.-Early life:He was born during Christmastide 1577 at Dorney, Buckinghamshire, where his father Laurence Mountague was vicar, and was educated at Eton. He was elected from Eton to a scholarship at King's College, Cambridge, and admitted on 24...

if it ever came to reunification with the Catholic Church. At the same time, Archbishop Laud

William Laud

William Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633 to 1645. One of the High Church Caroline divines, he opposed radical forms of Puritanism...

sent spies into Hall's diocese to report on the Calvinistic tendencies of the bishop and his lenience to the Puritan and low church clergy. Hall gradually took up an anti-Laudian, but also anti-Presbyterian position, while remaining a Protestant eirenicist in co-operation with John Dury

John Dury

John Dury was a Scottish Calvinist minister and a significant intellectual of the English Civil War period. He made efforts to re-unite the Calvinist and Lutheran wings of Protestantism, hoping to succeed when he moved to Kassel in 1661, but he did not accomplish this...

and concerned with continental Europe.

In 1641 Hall was translated to the See of Norwich, and in the same year sat on the Lords' Committee on religion. On 30 December, he was, with other bishops, brought before the bar of the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

to answer a charge of high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

of which the Commons had voted them guilty. They were finally convicted of an offence against the Statute of Praemunire

Praemunire

In English history, Praemunire or Praemunire facias was a law that prohibited the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, imperial or foreign, or some other alien jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the supremacy of the Monarch...

, and condemned to forfeit their estates, receiving a small maintenance from the parliament. They were immured in the Tower from New Year to Whitsuntide, when they were released on finding bail.

Retirement

On his release, Hall proceeded to his new diocese at Norwich, the revenues of which he seems for a time to have received, but in 1643, when the property of the "malignants" was sequestrated, Hall was mentioned by name. Mrs Hall had difficulty in securing a fifth of the maintenance (£400) assigned to the bishop by the parliament; they were eventually ejected from the palace, and the cathedral was dismantled. Hall describes its desecration in Hard Measure:He goes on to describe vividly the triumphal procession of the puritan iconoclasts as they carried vestments, service books and singing books to be burned in the nearby market place, while soldiers lounged in the despoiled cathedral drinking and smoking their pipes.

Hall retired to the village of Heigham, near Norwich, where he spent his last thirteen years preaching and writing until he was first forbidden by man, and at last disabled by God. He bore his many troubles and the additional burden of much bodily suffering with sweetness and patience, dying on 8 September 1656. In his old age, Hall was attended upon by the doctor Thomas Browne

Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne was an English author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including medicine, religion, science and the esoteric....

, who wrote of him:

Works

He contributed to several distinct literary areas: satirical verse as a young man; polemical writing, particularly in defending episcopacy; and devotional writings, including contemplations carrying a political slant. He was influenced by Lipsian neostoicism. The anonymous Mundus alter et idem is a satirical utopian fantasy, not denied by him in strong terms at any point.Satire and poetry

During his residence at Cambridge he wrote his Virgidemiarum (1597),' satires in English written after Latin models. The claim he put forward in the prologue to be the earliest English satirist offended John MarstonJohn Marston

John Marston was an English poet, playwright and satirist during the late Elizabethan and Jacobean periods...

, who attacked him in satires published in 1598. In the declining years of the reign of Elizabeth I there was much satirical literature, and it was felt to be an attack on established institutions. John Whitgift

John Whitgift

John Whitgift was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1583 to his death. Noted for his hospitality, he was somewhat ostentatious in his habits, sometimes visiting Canterbury and other towns attended by a retinue of 800 horsemen...

, the archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, ordered that Hall's satires, along with works of Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe was an English Elizabethan pamphleteer, playwright, poet and satirist. He was the son of the minister William Nashe and his wife Margaret .-Early life:...

, John Marston

John Marston

John Marston was an English poet, playwright and satirist during the late Elizabethan and Jacobean periods...

, Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe was an English dramatist, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. As the foremost Elizabethan tragedian, next to William Shakespeare, he is known for his blank verse, his overreaching protagonists, and his mysterious death.A warrant was issued for Marlowe's arrest on 18 May...

, Sir John Davies and others should be burnt, on the ground of licentiousness; but shortly afterwards Hall's book was ordered to be "staied at the press," which may be interpreted as reprieved.

Virgidemiarum was followed by an amended edition in 1598, and in the same year by Virgidemiarum. The three last bookes. Of byting Satyres (reprinted 1599). Not in fact the earliest English satirist, Hall wrote in smooth heroic couplet

Heroic couplet

A heroic couplet is a traditional form for English poetry, commonly used for epic and narrative poetry; it refers to poems constructed from a sequence of rhyming pairs of iambic pentameter lines. The rhyme is always masculine. Use of the heroic couplet was first pioneered by Geoffrey Chaucer in...

s. In the first book of his satires (Poeticall), he attacks the writers whose verses were devoted to licentious subjects, the bombast of Tamburlaine

Tamburlaine (play)

Tamburlaine the Great is the name of a play in two parts by Christopher Marlowe. It is loosely based on the life of the Central Asian emperor, Timur 'the lame'...

and tragedies built on similar lines, the laments of the ghosts of the Mirror for Magistrates

Mirror for Magistrates

Mirror for Magistrates is a collection of English poems from the Tudor period by various authors which retell the lives and the tragic ends of various historical figures.-Background:...

, the metrical eccentricities of Gabriel Harvey

Gabriel Harvey

Gabriel Harvey was an English writer. Harvey was a notable scholar, though his reputation suffered from his quarrel with Thomas Nashe...

and Richard Stanyhurst

Richard Stanyhurst

Richard Stanyhurst was an Irish alchemist, translator, poet and historian, born in Dublin.His father, James Stanyhurst, was recorder of the city, and Speaker of the Irish House of Commons in 1557, 1560 and 1568. Richard was sent in 1563 to University College, Oxford, and took his degree five years...

, the extravagances of the sonneteers, and the sacred poets (Southwell is aimed at in "Now good St Peter weeps pure Helicon, And both the Mary's make a music moan"). In Book II Satire 6 occurs a description of the trencher-chaplain, who is tutor and hanger-on in a country manor. Among his other satirical portraits is that of the famished gallant, the guest of "Duke Humfray." Book VI consists of one long satire on vices and follies dealt with in the earlier books.

Hall's earliest published verse appeared in a collection of elegies on the death of Dr. William Whitaker

William Whitaker (theologian)

William Whitaker was a prominent Anglican theologian. He was Master of St. John's College, Cambridge, and a leading divine in the university in the latter half of the sixteenth century.-Early life and education:...

, to which he contributed the only English poem (1596). A line in Marston's Pigmalion's Image (1598) indicates that Hall wrote pastoral poems, but none of these have survived. He also wrote:

- The King's Prophecie; or Weeping Joy (1603), a gratulatory poem on the accession of James I

- Epistles, both the first and second volumes of which appeared in 1608 and a third in 1611

- Characters of Virtues and Vices (1608), versified by Nahum TateNahum TateNahum Tate was an Irish poet, hymnist, and lyricist, who became England's poet laureate in 1692.-Life:Nahum Teate came from a family of Puritan clergymen...

(1691) - Solomon's Divine Arts (1609)

Hall gave up verse satires and lighter forms of literature when he was ordained a minister in the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

.

Mundus alter et idem

Hall wrote, according to current scholarly consensus, the dystopian Mundus alter et idem sive Terra Australis antehac semper incognita; Longis itineribus peregrini Academici nuperrime illustrata (1605? and 1607), by "Mercurius Britannicus." Mundus alter is an excuse for a satirical description of London, with some criticism of the Catholic church, and is said to have furnished Jonathan SwiftJonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

with hints for Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

. It is classified as a Menippean satire

Menippean satire

The genre of Menippean satire is a form of satire, usually in prose, which has a length and structure similar to a novel and is characterized by attacking mental attitudes instead of specific individuals...

, and was almost contemporary with another such satire by John Barclay, Euphormionis Satyricon, with which it shares the features of being written in Latin (Hall generally wrote in English), and a concern for religious commentary.

The narrator takes a voyage in the ship Fantasia, in the southern seas, visiting the lands of Crapulia, Viraginia, Moronia and Lavernia (populated by gluttons, nags, fools and thieves respectively). Moronia parodies Catholic customs; in its province Variana is found an antique coin parodying Justus Lipsius

Justus Lipsius

Justus Lipsius was a Southern-Netherlandish philologist and humanist. Lipsius wrote a series of works designed to revive ancient Stoicism in a form that would be compatible with Christianity. The most famous of these is De Constantia...

, a target for Hall's satire ad hominem (here the personal attack goes beyond the Menippean model).

Hall wrote it for private circulation, and its publication was not intended by him. The book was published at the hands of William Knight, who wrote a Latin preface, he being only tentatively identified by scholars (there are several candidate clergymen of that name, the one with dates (c.1573–1617?) being singled out). It was reprinted in 1643, with Civitas Solis by Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella OP , baptized Giovanni Domenico Campanella, was an Italian philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet.-Biography:...

, and New Atlantis

New Atlantis

New Atlantis and similar can mean:*New Atlantis, a novel by Sir Francis Bacon*The New Atlantis, founded in 2003, a journal about the social and political dimensions of science and technology...

by Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

. It was not clearly ascribed to Hall by name until 1674, when Thomas Hyde

Thomas Hyde

Thomas Hyde was an English orientalist. The first use of the word dualism is attributed to him, in 1700.-Life:He was born at Billingsley, near Bridgnorth in Shropshire, on 29 June 1636...

, the librarian of the Bodleian, identified "Mercurius Britannicus" with Joseph Hall, as is now accepted. On the other hand Hall's authorship was an open secret, and in 1642 John Milton

John Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

used it to attack Hall (during the Smectymnuus

Smectymnuus

Smectymnuus was the nom de plume of a group of Puritan clergymen active in England in 1641. It comprised four leading English churchmen, and one Scottish minister...

controversy) by employing the argument that Utopia

Utopia

Utopia is an ideal community or society possessing a perfect socio-politico-legal system. The word was imported from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean. The term has been used to describe both intentional communities that attempt...

and New Atlantis had a constructive approach lacking in Mundus Alter.

The Mundus alter was translated into English by John Healey

John Healey (translator)

John Healey was an English translator. Among scanty biographical facts, he was ill, according to a statement of his friend the printer Thomas Thorpe, in 1609, and was dead in the following year.-Works:...

(1608–9) as The Discovery of a New World or A Description of the South Indies by an English Mercury. This was a free and necessarily unauthorised translation, and involved Hall in controversy. Andrea McCrea describes Hall's interactions with Robert Dallington

Robert Dallington

Sir Robert Dallington was an English courtier, travel writer and translator, and master of the London Charterhouse.-Life:He was born at Geddington, Northamptonshire. He entered Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and was there from about 1575 to 1580; from his incorporation at Oxford as M.A. it is...

, and then Healey, against the background of a few years of the pace-setting culture of the court of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales

Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales was the elder son of King James I & VI and Anne of Denmark. His name derives from his grandfathers: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and Frederick II of Denmark. Prince Henry was widely seen as a bright and promising heir to his father's throne...

. Dallington advocated travel, indeed the Grand Tour

Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the traditional trip of Europe undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men of means. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transit in the 1840s, and was associated with a standard itinerary. It served as an educational rite of passage...

, while Hall was minatory about its effects; Dallington wrote aphorisms following Lipsius and Guicciardini, while Hall had moved away from the Tacitist

Tacitean studies

Tacitean studies, centred on the work of Tacitus the Ancient Roman historian, constitute an area of scholarship extending beyond the field of history. The work has traditionally been read for its moral instruction, its narrative, and its inimitable prose style; Tacitus has been most influential...

strand in humanist thought to the more conservative Seneca

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and in one work humorist, of the Silver Age of Latin literature. He was tutor and later advisor to emperor Nero...

n tendency with which he was permanently to be associated. Healey embroidered political details into the Mundus alter translation, and outed Hall as author at least as far as his initials, the emphasis on politics again being a Tacitist one. Healey had noble patronage, and Hall's position with respect to the princely court culture was revealed as close that of the king, placing him as an outsider rather than in the new group of movers and shakers. On the death of Prince Henry, his patron, Hall did preach the funeral sermon to his household.

Controversy

Hall's initial work of religious controversy was against Protestant separatists. In 1608 he had written a letter of remonstrance to John RobinsonJohn Robinson (pastor)

John Robinson was the pastor of the "Pilgrim Fathers" before they left on the Mayflower. He became one of the early leaders of the English Separatists, minister of the Pilgrims, and is regarded as one of the founders of the Congregational Church.-Early life:Robinson was born in Sturton le Steeple...

and John Smyth. Robinson, who had been a beneficed clergyman near Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth, often known to locals as Yarmouth, is a coastal town in Norfolk, England. It is at the mouth of the River Yare, east of Norwich.It has been a seaside resort since 1760, and is the gateway from the Norfolk Broads to the sea...

, had replied in An Answer to a Censorious Epistle; and uHall published (1610) A Common Apology against the Brownists, a lengthy treatise answering Robinson paragraph by paragraph. It set a style, tight but rich using animadversion, for Hall's theological writings. Hall criticised Robinson, the future pastor of the Mayflower

Mayflower

The Mayflower was the ship that transported the English Separatists, better known as the Pilgrims, from a site near the Mayflower Steps in Plymouth, England, to Plymouth, Massachusetts, , in 1620...

congregation, alongside Richard Bernard

Richard Bernard

Richard Bernard was an English Puritan clergyman and writer.-Life:Bernard was born in Epworth and received his education at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he matriculated in 1592, obtained his BA in 1595, and an MA in 1598. He was married in 1601 and had six children...

and John Murton

John Murton

John Murton , also known as John Morton, was a co-founder of the Baptist faith in Great Britain.John Murton had been a furrier by trade in Gainsborough-on-Trent and was a member of the 1607 Gainsborough Congregation that relocated to Amsterdam, and Murton allegedly baptized John Smyth...

.

He did his best in his Via media, The Way of Peace (1619), to persuade the two parties (Calvinist and Arminian) to accept a compromise. His later defence of the English Church, and episcopacy as Biblical, entitled Episcopacy by Divine Right (1640), was twice revised at Laud's dictation.

This was followed by An Humble Remonstrance to the High Court of Parliament (1640 and 1641), an eloquent and forceful defence of his order, which produced a retort from the syndicate of Puritan divines, who wrote under the name of Smectymnuus

Smectymnuus

Smectymnuus was the nom de plume of a group of Puritan clergymen active in England in 1641. It comprised four leading English churchmen, and one Scottish minister...

. This was followed by a long controversy to which John Milton

John Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

contributed five pamphlets, virulently attacking Hall and his early satires.

Other controversial writings include:

- The Olde Religion: A treatise, wherein is laid downe the true state of the difference betwixt the Reformed and the Romane Church; and the blame of this schisme is cast upon the true Authors (1628)

- Columba Noae olivam adferens, a sermon preached at St Paul's in 1623

- A Short Answer to the Vindication of Smectymnuus (1641)

- A Modest Confutation of (Milton's) Animadversions (1642).

Devotional

His devotional works include:- Holy Observations Lib. I (1607)

- Some few of David's Psalmes Metaphrased (1609)

- three centuries of Meditations and Vowes, Divine and Morall (1606, 1607, 1609), edited by Charles Sayle

- The Arte of Divine Meditation (1607)

- Heaven upon Earth, or of True Peace and Tranquillitie of Mind (1606), reprinted with some of his letters in John WesleyJohn WesleyJohn Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

's Christian Library, vol. iv. (1819) - Occasional Meditations (1630), edited by his son Robert Hall

- Henochisme; or a Treatise showing how to walk with God (1639), translated from Bishop Hall's Latin by Moses Wall

- The Devout Soul; or Rules of Heavenly Devotion (1644), often since reprinted

- The Balm of Gilead (1646, 1752)

- Christ Mysticall; or the blessed union of Christ and his Members (1647), of which General Gordon was a student (reprinted from Gordon's copy, 1893)

- Susurrium cum Deo (1659)

- The Great Mysterie of Godliness (1650)

- Resolutions and Decisions of Divers Practicall cases of Conscience (1649, 1650, 1654).

Autobiographical

His autobiographical tracts are Observations of some Specialities of Divine Providence in the Life of Joseph Hall, Bishop of Norwich, Written with his own hand, and his Hard Measure, reprinted in Christopher WordsworthChristopher Wordsworth

Christopher Wordsworth was an English bishop and man of letters.-Life:Wordsworth was born in London, the youngest son of the Rev. Dr. Christopher Wordsworth, Master of Trinity and a nephew of the poet William Wordsworth...

's Ecclesiastical Biography.

Editions

In 1615 Hall published A Recollection of such treatises as have been published (1615, 1617, 1621); in 1625 appeared his Works (reprinted 1627, 1628, 1634, 1662).The first complete Works appeared in 1808, edited by Josiah Pratt

Josiah Pratt

Josiah Pratt was an English evangelical clergyman, involved in publications and the administration of missionary work.-Life:The second son of Josiah Pratt, a Birmingham manufacturer, he was born in Birmingham on 21 December 1768. With his two younger brothers, Isaac and Henry, Josiah was educated...

. Other editions are by Peter Hall (1837) and by Philip Wynter (1863). See also Bishop Hall, his Life and Times (1826), by Rev. John Jones; Life of Joseph Hall, by Rev. George Lewis (1886); Alexander Balloch Grosart

Alexander Balloch Grosart

Alexander Balloch Grosart was a Scottish clergyman and literary editor. He is chiefly remembered for reprinting much rare Elizabethan literature, a work which he undertook because of his interest in Puritan theology.-Life:...

, The Complete Poems of Joseph Hall with introductions, etc. (1879); Satires, etc. (Early English Poets, ed. Samuel Weller Singer

Samuel Weller Singer

Samuel Weller Singer was an author and scholar on the work of William Shakespeare. He is also now remembered as a pioneer historian of card games.-Life:...

, 1824). Many of Hall's works were translated into French, and some into Dutch

Dutch language

Dutch is a West Germanic language and the native language of the majority of the population of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second...

, and there have been numerous selections from his devotional works.

Family

By his wife Elizabeth, daughter of George Winiffe of BrettenhamBrettenham, Suffolk

Brettenham is a village and civil parish in the Babergh district of Suffolk, England. In 2005 it had a population of 270.Almost the entire built-up area is defined as a conservation area, and the parish also contains some ancient woodland at Ram's Wood. The village is home to independent prep...

, Suffolk (she died 27 August 1652, aged 69), Hall had six sons and two daughters. The eldest son, Robert Hall, D.D. (1605–1667), became canon of Exeter in 1629, and archdeacon of Cornwall in 1633. Joseph Hall, the second son (1607–1669), was registrar of Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter at Exeter, is an Anglican cathedral, and the seat of the Bishop of Exeter, in the city of Exeter, Devon in South West England....

. George Hall

George Hall (bishop)

-Life:His father was Joseph Hall. George Hall was born at Waltham Abbey, Essex, and studied at Exeter College, Oxford, where he became a Fellow. He became vicar of Menheniot and in 1641 archdeacon of Cornwall....

, the third son (1612–1668), became bishop of Chester

Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.The diocese expands across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in the City of Chester where the seat is located at the Cathedral...

. Samuel, the fourth son (1616–1674), was sub-dean of Exeter.

Authorities

In 1826 John Jones published Bishop Hall, His Life and Times. A recent biography of Joseph Hall is Bishop Joseph Hall: 1574–1656: A biographical and critical study by Frank Livingstone Huntley, D.S.Brewer Ltd, Cambridge, 1979.Criticism of his satires is to be found in Thomas Warton

Thomas Warton

Thomas Warton was an English literary historian, critic, and poet. From 1785 to 1790 he was the Poet Laureate of England...

's History of English Poetry, vol. iv. pp. 363–409 (ed. Hazlitt, 1871), where a comparison is instituted between Marston and Hall.

Further reading

- Richard A. McCabe, Joseph Hall: A Study in Satire and Meditation (1982)

Attribution