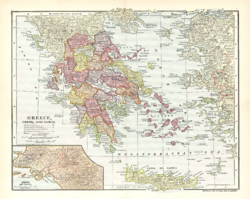

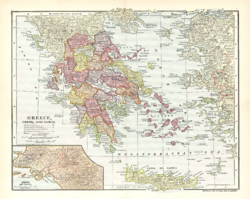

Kingdom of Greece

Encyclopedia

The Kingdom of Greece

(Greek

: , Vasílion tis Elládos) was a state established in 1832 in the Convention of London

by the Great Powers (the United Kingdom

, France

and the Russian Empire

). It was internationally recognized in the Treaty of Constantinople

, where it also secured full independence

from the Ottoman Empire

, marking the birth of the first fully independent Greek state since the fall of the last remnants of the Byzantine Empire

to the Ottomans in the mid-15th century. It succeeded from the Greek provisional governments

of the Greek War of Independence

, and lasted until 1924, when the monarchy was abolished, and the Second Hellenic Republic

declared. The Kingdom was restored in 1935, and lasted until 1974, when, in the aftermath of a seven-year military dictatorship

, the current Third Republic came into existence.

, France

, and Russia

) in 1828. Count Ioannis Kapodistrias

became the head of the Greek government, but he was assassinated in 1831. At the insistence of the Powers, the 1832 Treaty of London

made Greece a monarchy. Otto of Wittelsbach, Prince of Bavaria

was chosen as its first King. Otto arrived at the provisional capital, Nafplion

, in 1833 aboard a British warship

.

Otto's reign would prove troubled, but managed to last for 30 years before he and his wife, Queen Amalia, left the way they came, aboard a British warship. During the early years of his reign a group of Bavaria

Otto's reign would prove troubled, but managed to last for 30 years before he and his wife, Queen Amalia, left the way they came, aboard a British warship. During the early years of his reign a group of Bavaria

n Regents ruled in his name, and made themselves very unpopular by trying to impose German ideas of rigid hierarchical government on the Greeks, while keeping most significant state offices away from them. Nevertheless they laid the foundations of a Greek administration, army, justice system and education system. Otto was sincere in his desire to give Greece good government, but he suffered from two great handicaps, his Roman Catholic faith, and the fact that his marriage to Queen Amalia remained childless. This meant he could neither be crowned as King of Greece under the Orthodox rite nor establish a dynasty.

The Bavarian Regents ruled until 1837, when at the insistence of Britain

and France

, they were recalled and Otto thereafter appointed Greek ministers, although Bavarian officials still ran most of the administration and the army. But Greece still had no legislature and no constitution. Greek discontent grew until a revolt broke out in Athens

in September 1843. Otto agreed to grant a constitution, and convened a National Assembly which met in November. The new constitution

created a bicameral parliament

, consisting of an Assembly (Vouli) and a Senate (Gerousia). Power then passed into the hands of a group of politicians, most of whom who had been commanders in the War of Independence against the Ottomans.

Greek politics in the 19th century was dominated by the national question. The majority of Greeks continued to live under Ottoman rule, and Greeks dreamed of liberating them all and reconstituting a state embracing all the Greek lands, with Constantinople

as its capital. This was called the Great Idea (Megali Idea

), and it was sustained by almost continuous rebellions against Ottoman rule in Greek-speaking territories, particularly Crete

, Thessaly

and Macedonia

. During the Crimean War

the British occupied Piraeus

to prevent Greece declaring war on the Ottomans as a Russian ally.

A new generation of Greek politicians was growing increasingly intolerant of King Otto's continuing interference in government. In 1862, the King dismissed his Prime Minister, the former admiral Constantine Kanaris, the most prominent politician of the period. This provoked a military rebellion, forcing Otto to accept the inevitable and leave the country. The Greeks then asked Britain to send Queen Victoria

's son Prince Alfred as their new king, but this was vetoed by the other Powers. Instead a young Danish Prince became King George I

. George was a very popular choice as a constitutional monarch, and he agreed that his sons would be raised in the Greek Orthodox faith. As a reward to the Greeks for adopting a pro-British King, Britain ceded the Ionian Islands

to Greece.

At the urging of Britain and King George

At the urging of Britain and King George

, Greece adopted a much more democratic constitution

in 1864. The powers of the King were reduced and the Senate was abolished, and the franchise was extended to all adult males. Nevertheless Greek politics remained heavily dynastic, as it has always been. Family names such as Zaimis, Rallis and Trikoupis occurred repeatedly as Prime Ministers. Although parties were centered around the individual leaders, often bearing their names, two broad political tendencies existed: the liberals, led first by Charilaos Trikoupis

and later by Eleftherios Venizelos

, and the conservatives, led initially by Theodoros Deligiannis

and later by Thrasivoulos Zaimis

. Trikoupis and Deligiannis dominated Greek politics in the later 19th century, alternating in office. Trikoupis favoured co-operation with Great Britain in foreign affairs, the creation of infrastructure and an indigenous industry, raising protective tariffs and progressive social legislation, while the more populist Deligiannis depended on the promotion of Greek nationalism and the Megali Idea

.

Greece remained a very poor country throughout the 19th century. The country lacked raw materials, infrastructure and capital. Agriculture was mostly at the subsistence level, and the only important export commodities were currants

, raisins and tobacco

. Some Greeks grew rich as merchants and shipowners, and Piraeus

became a major port, but little of this wealth found its way to the Greek peasantry. Greece remained hopelessly in debt to London finance houses. By the 1890s Greece was virtually bankrupt, and public insolvency

was declared in 1893. Poverty was rife in the rural areas and the islands, and was eased only by large-scale emigration to the United States

. There was little education in the rural areas. Nevertheless there was progress in building communications and infrastructure, and fine public buildings were erected in Athens. Despite the bad financial situation, Athens staged the revival of the Olympic Games

in 1896, which proved a great success.

The parliamentary process developed greatly in Greece during the reign of George I. Initially, the royal prerogative in choosing his prime minister remained and contributed to governmental instability, until the introduction of the dedilomeni principle of parliamentary confidence

The parliamentary process developed greatly in Greece during the reign of George I. Initially, the royal prerogative in choosing his prime minister remained and contributed to governmental instability, until the introduction of the dedilomeni principle of parliamentary confidence

in 1875 by the reformist Charilaos Trikoupis

. Clientelism and frequent electoral upheavals however remained the norm in Greek politics, and frustrated the country's development. Corruption and Trikoupis' increased spending to create necessary infrastructure like the Corinth Canal

overtaxed the weak Greek economy, forcing the declaration of public insolvency in 1893 and to accept the imposition of an International Financial Control authority to pay off the country's debtors. Another political issue in 19th-century Greece was uniquely Greek: the language question. The Greek people spoke a form of Greek called Demotic

. Many of the educated elite saw this as a peasant dialect and were determined to restore the glories of Ancient Greek

. Government documents and newspapers were consequently published in Katharevousa

(purified) Greek, a form which few ordinary Greeks could read. Liberals favoured recognising Demotic as the national language, but conservatives and the Orthodox Church resisted all such efforts, to the extent that, when the New Testament

was translated into Demotic in 1901, riots erupted in Athens and the government fell (the Evangeliaka). This issue would continue to plague Greek politics until the 1970s.

All Greeks were united, however, in their determination to liberate the Greek-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Especially in Crete

All Greeks were united, however, in their determination to liberate the Greek-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Especially in Crete

, a prolonged revolt in 1866–1869

had raised nationalist fervour. When war broke out between Russia and the Ottomans in 1877, Greek popular sentiment rallied to Russia's side, but Greece was too poor, and too concerned of British intervention, to officially enter the war. Nevertheless, in 1881, Thessaly

and small parts of Epirus

were ceded to Greece as part of the Treaty of Berlin

, while frustrating Greek hopes of receiving Crete

. Greeks in Crete continued to stage regular revolts, and in 1897, the Greek government under Theodoros Deligiannis, bowing to popular pressure, declared war on the Ottomans. In the ensuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897

the badly trained and equipped Greek army was defeated by the Ottomans. Through the intervention of the Great Powers however, Greece lost only a little territory along the border to Turkey, while Crete was established as an autonomous state

under Prince George of Greece.

Nationalist sentiment among Greeks in the Ottoman Empire continued to grow, and by the 1890s there were constant disturbances in Macedonia

. Here the Greeks were in competition not only with the Ottomans but also with the Bulgarians, engaged in an armed propaganda struggle for the hearts and minds of the ethnically mixed local population, the so-called "Macedonian Struggle

". In July 1908, the Young Turk Revolution

broke out in the Ottoman Empire

. Taking advantage of the Ottoman internal turmoil, Austria-Hungary

annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina

, and Bulgaria

declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. On Crete, the local population, led by a young politician named Eleftherios Venizelos

, declared Enosis

, Union with Greece, provoking another crisis. The fact that the Greek government, led by Dimitrios Rallis

, proved unable to likewise take advantage of the situation and bring Crete into the fold, rankled with many Greeks, especially with young officers. These formed a secret society, the "Military League", with the purpose of emulating their Ottoman colleagues and seek reforms. The resulting Goudi coup

on 15 August 1909 marked a watershed in modern Greek history: as the military conspirators were inexperienced in politics, they asked Venizelos, who had impeccable liberal credentials, to come to Greece as their political adviser. Venizelos quickly established himself as a powerful political figure, and his allies won the August 1910 elections. Venizelos became Prime Minister in October 1910, ushering a period of 25 years where his personality would dominate Greek politics.

Venizelos initiated a major reform program, including a new and more liberal constitution

Venizelos initiated a major reform program, including a new and more liberal constitution

and reforms in the spheres of public administration, education and economy. French and British military missions were invited for the army and navy respectively, and arms purchases were made. In the meantime, the Ottoman Empire's weaknesses were revealed by the ongoing Italo-Turkish War

in Libya. Through spring 1912, a series of bilateral agreements between the Christian Balkan states (Greece, Bulgaria

, Montenegro

and Serbia

) formed the Balkan League

, which in October 1912 declared war on the Ottoman Empire. In the First Balkan War

, the Ottomans were defeated on all fronts, and the four allies rushed to grab as much territory as they could. The Greeks occupied Thessaloniki

just ahead of the Bulgarians, and also took much of Epirus

with Ioannina

, as well as Crete

and the Aegean Islands

. The Treaty of London ended the war, but no one was left satisfied, and soon, the four allies fell out over the partition of Macedonia

. In June 1913, Bulgaria attacked Greece and Serbia, beginning the Second Balkan War

, but was beaten back. The Treaty of Bucharest, which concluded the war, left Greece with southern Epirus, the southern half of Macedonia, Crete and the Aegean islands, except for the Dodecanese

, which had been occupied by Italy

in 1911. These gains nearly doubled Greece's area and population.

In March 1913, an anarchist, Alexandros Schinas

, assassinated King George in Thessaloniki, and his son came to the throne as Constantine I. Constantine was the first Greek king born in Greece and the first to be Greek Orthodox. His very name had been chosen in the spirit of romantic Greek nationalism (the Megali Idea

), evoking the Byzantine emperors of that name. In addition, as the Commander-in-chief of the Greek Army during the Balkan Wars

, his popularity was enormous, rivalled only by that of Venizelos, his Prime Minister. When World War I

broke out in 1914, despite Greece's treaty of alliance with Serbia, both leaders preferred to maintain a neutral stance. But when, in early 1915, the Allies

asked for Greek help in the Dardanelles campaign, offering Cyprus

in exchange, their diverging views became apparent: Constantine had been educated in Germany

, was married to Sophia of Prussia

, sister of Kaiser Wilhelm, and was convinced of the Central Powers

' victory. Venizelos on the other hand was an ardent anglophile, and believed in an Allied victory. Since Greece, a maritime country, could not oppose the mighty British navy, and citing the need for a respite after two wars, King Constantine favored continued neutrality, while Venizelos actively sought Greek entry in the war on the Allied side. Venizelos resigned, but won the next elections, and again formed the government. When Bulgaria

entered the war as a German ally in October 1915, Venizelos invited Entente

forces into Greece (the Salonika Front

), for which he was again dismissed by Constantine.

In August 1916, after several incidents where both combatants encroached upon the still theoretically neutral Greek territory, Venizelist officers rose up in Allied-controlled Thessaloniki, and Venizelos established a separate government

In August 1916, after several incidents where both combatants encroached upon the still theoretically neutral Greek territory, Venizelist officers rose up in Allied-controlled Thessaloniki, and Venizelos established a separate government

there. Constantine was now ruling only in what was Greece before the Balkan Wars ("Old Greece"), and his government was subject to repeated humiliations from the Allies. In November 1916 the French occupied Piraeus

, bombarded Athens and forced the Greek fleet to surrender. The royalist troops fired at them, leading to a battle between French and Greek royalist troops. There were also riots against supporters of Venizelos in Athens (the Noemvriana

). Following the February Revolution

in Russia

however, the Tsar's support for his cousin was removed, and Constantine was forced to leave the country, without actually abdicating, in June 1917. His second son Alexander became King, while the remaining royal family and the most prominent royalists followed into exile. Venizelos now led a superficially united Greece into the war on the Allied side, but underneath the surface, the division of Greek society into Venizelists

and anti-Venizelists, the so-called National Schism, became more entrenched.

With the end of the war in November 1918, the moribund Ottoman Empire was ready to be carved up amongst the victors, and Greece now expected the Allies to deliver on their promises. In no small measure through the diplomatic efforts of Venizelos, Greece secured Western Thrace

With the end of the war in November 1918, the moribund Ottoman Empire was ready to be carved up amongst the victors, and Greece now expected the Allies to deliver on their promises. In no small measure through the diplomatic efforts of Venizelos, Greece secured Western Thrace

in the Treaty of Neuilly

in November 1919 and Eastern Thrace and a zone around Smyrna

in western Anatolia

(already under Greek administration

since May 1919) in the Treaty of Sèvres

of August 1920. The future of Constantinople was left to be determined. But at the same time, a nationalist movement

had arisen in Turkey

, led by Mustafa Kemal (later Kemal Atatürk), who set up a rival government in Ankara

and was engaged in fighting the Greek army.

At this point, nevertheless, the fulfillment of the Megali Idea seemed near. Yet so deep was the rift in Greek society, that on his return to Greece, an assassination attempt was made on Venizelos by two royalist former officers. Even more surprisingly, Venizelos' Liberal Party

lost the elections

called in November 1920, and in a referendum

shortly after, the Greek people voted for the return of King Constantine from exile, following the sudden death of Alexander. The United Opposition, which had campaigned on the slogan of an end to the war in Anatolia, instead intensified it. But the royalist restoration had dire consequences: many veteran Venizelist officers were dismissed or left the army, while Italy and France found the return of the hated Constantine a useful pretext for switching their support to Kemal. Finally, in August 1922, the Turkish army shattered the Greek front, and took Smyrna

.

The Greek army evacuated not only Anatolia, but also Eastern Thrace and the islands of Imbros

and Tenedos

(Treaty of Lausanne

). A compulsory population exchange

was agreed between the two countries, with over 1.5 million Christians and almost half a million Muslims being uprooted. This catastrophe marked the end of the Megali Idea, and left Greece financially exhausted, demoralized, and having to house and feed a proportionately huge number of refugees

.

The catastrophe deepened the political crisis, with the returning army rising up under Venizelist officers and forcing King Constantine to abdicate again, in September 1922, in favour of his firstborn son, George II

. The "Revolutionary Committee", headed by Colonels Stylianos Gonatas

(soon to become Prime Minister) and Nikolaos Plastiras

engaged in a witch-hunt against the royalists, culminating in the "Trial of the Six

". In October 1923, elections

were called for December, which would form a National Assembly with powers to draft a new constitution. Following a failed royalist coup, the monarchist parties abstained, leading to a landslide for the Liberals and their allies. King George II was asked to leave the country, and on 25 March 1924, Alexandros Papanastasiou

proclaimed the Second Hellenic Republic

, ratified by plebiscite

a month later.

On 10 October 1935, a few months after he suppressed the second attempt in March 1935, Georgios Kondylis

, the former Venizelist stalwart, abolished the Republic in another coup, and declared the monarchy restored. A rigged plebiscite

confirmed the regime change (with an unsurprising 97.88% of votes), and King George II returned.

King George II immediately dismissed Kondylis and appointed Professor Konstantinos Demertzis

as interim Prime Minister. Venizelos meanwhile, in exile, urged an end to the conflict over the monarchy in view of the threat to Greece from the rise of Fascist Italy

. His successors as Liberal leader, Themistoklis Sophoulis

and Georgios Papandreou, agreed, and the restoration of the monarchy was accepted. The 1936 elections

resulted in a hung parliament

, with the Communists

holding the balance. As no government could be formed, Demertzis continued on. At the same time, a series of deaths left the Greek political scene in disarray: Kondylis died in February, Venizelos in March, Demertzis in April and Tsaldaris in May. The road was now clear for Ioannis Metaxas, who had succeeded Demertzis as interim Prime Minister.

Metaxas, a retired royalist general, believed that an authoritarian government was necessary to prevent social conflict and, especially, quell the rising power of the Communists. On 4 August 1936, with the King's support, he suspended parliament and established the 4th of August Regime

. The Communists were suppressed and the Liberal leaders went into internal exile. Patterning itself after Benito Mussolini

's Fascist Italy, Metaxas' regime promoted various concepts such as the "Third Hellenic Civilization", the Roman salute

, a national youth organization

, and introduced measures to gain popular support, such as the Greek Social Insurance Institute

(IKA), still the biggest social security institution in Greece.

Despite these efforts the regime lacked a broad popular base or a mass movement supporting it. The Greek people were generally apathetic, without actively opposing Metaxas. Metaxas also improved the country's defenses in preparation for the forthcoming European war, constructing, among other defensive measures, the "Metaxas Line

". Despite his aping of Fascism, and the strong economic ties with resurgent Nazi Germany

, Metaxas followed a policy of neutrality, given Greece's traditionally strong ties to Britain, reinforced by King George II's personal anglophilia. In April 1939, the Italian threat suddenly loomed closer, as Italy annexed

Albania

, whereupon Britain publicly guaranteed Greece's borders. Thus, when World War II

broke out in September 1939, Greece remained neutral.

Despite this declared neutrality, Greece became a target for Mussolini's expansionist policies. Provocations against Greece included the sinking of the light cruiser Elli

Despite this declared neutrality, Greece became a target for Mussolini's expansionist policies. Provocations against Greece included the sinking of the light cruiser Elli

on 15 August 1940. Italian troops crossed the border on 28 October 1940, beginning the Greco-Italian War

, but were stopped by determined Greek defence, and ultimately driven back into Albania

. Metaxas died suddenly in January 1941. His death raised hopes of a liberalization of his regime and the restoration of parliamentary rule, but King George quashed these hopes when he retained the regime's machinery in place. In the meantime, Adolf Hitler

was reluctantly forced to divert German troops to rescue Mussolini from defeat, and attacked Greece

through Yugoslavia

and Bulgaria on 6 April 1941. Despite British assistance, by the end of May, the Germans had overrun most of the country. The King and the government escaped to Crete, where they stayed until the end of the Battle of Crete

. They then transferred to Egypt

, where a government in exile

was established.

The occupied country was divided in three zones (German, Italian and Bulgarian) and in Athens, a puppet regime was established. The members were either conservatives

The occupied country was divided in three zones (German, Italian and Bulgarian) and in Athens, a puppet regime was established. The members were either conservatives

or nationalists with fascist leanings. The three quisling

prime ministers were Georgios Tsolakoglou

, the general who had signed the armistice with the Wehrmacht, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos

, and Ioannis Rallis

, who took office when the German defeat was inevitable, and aimed primarily at combating the left-wing Resistance movement. To this end, he created the collaborationist Security Battalions

.

Greece suffered terrible privations during World War II

, as the Germans appropriated most of the country's agricultural production and prevented its fishing fleets from operating. As a result, and because a British blockade initially hindered foreign relief efforts, a wide-scale famine

resulted, when hundreds of thousands perished, especially in the winter of 1941-1942. In the mountains of the Greek mainland, in the meantime, several resistance movements

sprang up, and by mid-1943, the Axis forces controlled only the main towns and the connecting roads, while a "Free Greece" was set up in the mountains. The largest resistance group, the National Liberation Front (EAM), was controlled by the Communists

, as was (Elas) led by Aris Velouchiotis and a civil war soon broke out between it and non-Communist groups such as the National Republican Greek League (EDES) in those areas liberated from the Germans. The exiled government in Cairo

was only intermittently in touch with the resistance movement, and exercised virtually no influence in the occupied country. Part of this was due to the unpopularity of the King George II in Greece itself, but despite efforts by Greek politicians, British support ensured his retention at the head of the Cairo government. As the German defeat drew nearer however, the various Greek political factions convened in Lebanon in May 1944, under British auspices, and formed a government of national unity, under George Papandreou

, in which EAM was represented by six ministers.

German forces withdrew on October 12, 1944, and the government in exile returned to Athens. After the German withdrawal, the EAM-ELAS guerrilla army effectively controlled most of Greece, but its leaders were reluctant to take control of the country, as they knew that Stalin

German forces withdrew on October 12, 1944, and the government in exile returned to Athens. After the German withdrawal, the EAM-ELAS guerrilla army effectively controlled most of Greece, but its leaders were reluctant to take control of the country, as they knew that Stalin

had agreed

that Greece would be in the British sphere of influence after the war. Tensions between the British-backed Papandreou and EAM, especially over the issue of disarmament of the various armed groups, leading to the resignation of the latter's ministers from the government. A few days later, on 3 December 1944, a large-scale pro-EAM demonstration in Athens ended in violence and ushered an intense, house-to-house struggle with British and monarchist forces (the Dekemvriana). After three weeks, the Communists were defeated: the Varkiza agreement ended the conflict and disarmed ELAS, and an unstable coalition government was formed. The anti-EAM backlash grew into a full-scale "White Terror", which exacerbated tensions. The Communists boycotted the March 1946 elections

, and on the same day, fighting broke out again. By the end of 1946, the Communist Democratic Army of Greece

had been formed, pitted against the governmental National Army, which was backed first by Britain and after 1947 by the United States

.

Communist successes in 1947–1948 enabled them to move freely over much of mainland Greece, but with extensive reorganization, the deportation of rural populations and American material support, the National Army was slowly able to regain control over most of the countryside. In 1949, the insurgents suffered a major blow, as Yugoslavia closed its borders following the split between Marshal Josip Broz Tito

with the Soviet Union

. Finally, in August 1949, the National Army under Marshal Alexander Papagos

launched an offensive that forced the remaining insurgents to surrender or flee across the northern border into the territory of Greece's northern Communist neighbors. The civil war resulted in 100,000 killed and caused catastrophic economic disruption. In addition, at least 25,000 Greeks and an unspecified number of Macedonian Slavs

were either voluntarily or forcibly evacuated to Eastern bloc

countries, while 700,000 became displaced persons inside the country. Many more emigrated to Australia

and other countries.

The postwar settlement saw Greece's territorial expansion, which had begun in 1832, come to an end. The 1947 Treaty of Paris

required Italy to hand over the Dodecanese

islands to Greece. These were the last majority-Greek-speaking areas to be united with the Greek state, apart from Cyprus which was a British possession until it became independent in 1960. Greece's ethnic homogeneity was increased by the postwar expulsion of 25,000 Albanians from Epirus (see Cham Albanians

). The only significant remaining minorities are the Muslims in Western Thrace (about 100,000) and a small Slavic-speaking minority in the north. Greek nationalists continued to claim southern Albania

(which they called Northern Epirus

), home of a significant Greek population (about 3%-12% in the whole of Albania ), and the Turkish-held islands of Imvros and Tenedos

, where there were smaller Greek minorities.

In the beginning of the 1950s, the forces of the Centre (EPEK) succeeded in gaining the power and under the leadership of the aged general N. Plastiras they governed for about half a four-year term. These were a series of governments having limited manoeuvre ability and inadequate influence in the political arena. This government, as well as those that followed, was constantly under the American auspices. The defeat of EPEK in the elections of 1952, apart from increasing the repressive measures that concerned the defeated of the Civil war, also marked the end of the general political position that it represented, namely political consensus and social reconciliation.

The Left, which had been ostracized from the political life of the country, found a way of expression through the constitution of EDA (United Democratic Left) in 1951, which turned out to be a significant pole, yet steadily excluded from the decision making centres. After the disbandment of the Centre as an autonomous political institution, EDA practically expanded its electoral influence to a significant part of the EAM-based Centre-Left.

The 1960s are part of the period 1953-72, during which Greek economy developed rapidly and was structured within the scope of European and worldwide economic developments. One of the main characteristics of that period was the major political event - as we have come to accept it - of the countrys accession in the EEC, in an attempt to create a common market. The relevant treaty was contracted in 1962.

The developmental strategy adopted by the country was embodied in centrally organized five-year plans; yet their orientation was indistinct. The average annual emigration, which absorbed the excess workforce and contributed to extremely high growth rates, exceeded the annual natural increase in population. The influx of large amounts of foreign private capital was being facilitated and consumption was expanded. These, associated with the rise of tourism, the expansion of shipping activity and with the migrant remittances, had a positive effect on the balance of payments. The peak of development was registered principally in manufacture, mainly in the textile and chemical industry and in the sector of metallurgy, the growth rate of which tended to reach 11% during 1965-70. The other large branch where obvious economic and social consequences were brought about, was that of construction. Consideration, a Greek invention, favoured the creation of a class of small-medium contractors on one hand and settled the housing system and property status on the other.

During that decade, youth came forth in society as a distinct social power with autonomous presence (creation of a new culture in music, fashion etc.) and displaying dynamism in the assertion of their social rights. The independence granted to Cyprus, which was mined from the very beginning, constituted the main focus of young activist mobilizations, along with struggles aiming at reforms in education, which were provisionally realized to a certain extent through the educational reform of 1964. The country reckoned on and was influenced by Europe - usually behind time - and by the current trends like never before. Thus, in a sense, the imposition of the military junta conflicted with the social and cultural occurrences.

The country descended into a prolonged political crisis, and elections were scheduled for late April 1967. On 21 April 1967 however, a group of right-wing colonels led by Colonel George Papadopoulos

seized power in a coup d'état

establishing the Regime of the Colonels. Civil liberties were suppressed, special military courts were established, and political parties were dissolved. Several thousand suspected communists and political opponents were imprisoned or exiled to remote Greek islands. Alleged US support for the junta is claimed to be the cause of rising anti-Americanism

in Greece during and following the junta's harsh rule. However, the junta's early years also saw a marked upturn in the economy, with increased foreign investment and large-scale infrastructure works. The junta was widely condemned abroad, but inside the country, discontent began to increase only after 1970, when the economy slowed down. Even the armed forces, the regime's foundation, were not immune: In May 1973, a planned coup by the Hellenic Navy

was narrowly suppressed, but led to the mutiny of the HNS Velos, whose officers sought political asylum in Italy. In response, junta leader Papadopoulos attempted to steer the regime towards a controlled democratization

, abolishing the monarchy and declaring himself President of the Republic.

The first constitution of the Kingdom of Greece was the Greek Constitution of 1844. On 3 September 1843, the military garrison of Athens, with the help of citizens, rebelled and demanded from King Otto

The first constitution of the Kingdom of Greece was the Greek Constitution of 1844. On 3 September 1843, the military garrison of Athens, with the help of citizens, rebelled and demanded from King Otto

the concession of a Constitution.

The Constitution that was proclaimed in March 1844 came from the workings of the "Third of September National Assembly of the Hellenes in Athens" and was a Constitutional Pact, in other words a contract between the monarch and the Nation. This Constitution re-established the Constitutional Monarchy and was based on the French Constitution of 1830 and the Belgian Constitution of 1831.

Its main provisions were the following: It established the principle of monarchical sovereignty, as the monarch was the decisive power of the State; the legislative power was to be exercised by the King - who also had the right to ratify the laws - by the Parliament, and by the Senate. The members of the Parliament could be no less than 80 and they were elected for a three-year term by universal suffrage. The senators were appointed for life by the King and their number was set at 27, although that number could increase should the need arise and per the monarch's will, but it could not exceed half the number of the members of Parliament.

The ministers' responsibility for the King's actions is established, who also appoints and removes them. Justice stems from the King and is dispensed in his name by the judges he himself appoints.

Lastly, this Assembly voted the electoral law of 18 March 1844, which was the first European law to provide, in essence, for universal suffrage

(but, only, of course, for men).

The Second National Assembly of the Hellenes took place in Athens

(1863–1864) and dealt both with the election of a new sovereign as well as with the drafting of a new Constitution, thereby implementing the transition from constitutional monarchy

to a Crowned Democracy.

Following the refusal of Prince Alfred of Great Britain

(who was elected by an overwhelming majority in the first referendum of the country in November 1862) to accept the crown of the Greek kingdom, the government offered the crown to the Danish prince George Christian Willem

of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Gluecksburg, who was crowned constitutional King of Greece under the name "George I, King of the Hellenes".

The Constitution of 1864 was drafted following the models of the Constitutions of Belgium

of 1831 and of Denmark

of 1849, and established in clear terms the principle of popular sovereignty, since the only legislative body with reversionary powers was now the Parliament. Furthermore, article 31 reiterated that all the powers stemmed from the Nation and were to be exercised as provided by the Constitution, while article 44 established the principle of accountability, taking into consideration that the King only possessed the powers that were bestowed on him by the Constitution and by the laws applying the same.

The Assembly chose the system of a single chamber Parliament (Vouli) with a four-year term, and hence abolished the Senate, which many accused for being a tool in the hands of the monarchy. Direct, secret and universal elections was adopted as the manner to elect the MPs, while elections were to be held simultaneously throughout the entire nation.

In addition, article 71 introduced a conflict between being an MP and a salaried public employee or mayor at the same time, but not with serving as an army officer.

The Constitution reiterated various clauses found in the Constitution of 1844

, such as that the King appoints and dismisses the ministers and that the latter are responsible for the person of the monarch, but it also allowed for the Parliament to establish "examination committees". Moreover, the King preserved the right to convoke the Parliament in ordinary as well as in extraordinary sessions, and to dissolve it at his discretion, provided, however, that the dissolution decree was also countersigned by the Cabinet.

The Constitution repeated verbatim the clause of article 24 of the Constitution of 1844, according to which "The King appoints and removes his Ministers". This phrase insinuated that the ministers were practically subordinate to the monarch, and thereby answered not only to the Parliament but to him as well. Moreover, nowhere was it stated in the Constitution that the King was obliged to appoint the Cabinet in conformity with the will of the majority in Parliament. This was, however, the interpretation that the modernizing political forces of the land upheld, invoking the principle of popular sovereignty and the spirit of the Parliamentary regime. They finally succeeded in imposing it through the principle of "manifest confidence" of the Parliament, which was expressed in 1875 by Charilaos Trikoupis

and which, that same year, in his Crown Speech, King George I expressly pledged to uphold: "I demand as a prerequisite, of all that I call beside me to assist me in governing the country, to possess the manifest confidence and trust of the majority of the Nation's representatives. Furthermore, I accept this approval to stem from the Parliament, as without it the harmonious functioning of the polity would be impossible".

The establishment of the principle of "manifest confidence" towards the end of the first decade of the crowned democracy, contributed towards the disappearance of a constitutional practice which, in many ways, reiterated the negative experiences of the period of the reign of King Otto

. Indeed, from 1864 through 1875 numerous elections of dubious validity had taken place, while, additionally and most importantly, there was an active involvement of the Throne in political affairs through the appointment of governments enjoying a minority in Parliament, or through the forced resignation of majority governments, when their political views clashed with those of the crown.

The Greek

Constitution of 1911 was a major step forward in the constitutional history of Greece

. Following the rise to power of Eleftherios Venizelos

after the Goudi revolt in 1909, Venizelos set about attempting to reform the state. The main outcome of this was a major revision to the Greek Constitution of 1864

.

The most noteworthy amendments to the Constitution of 1864

concerning the protection of human rights, were the more effective protection of personal security, equality in tax burdens, of the right to assemble and of the inviolability of the domicile. Furthermore, the Constitution facilitated expropriation to allocate property to landless farmers

, while simultaneously judicially protecting property rights.

Other important changes included the institution of an Electoral Court for the settlement of election disputes stemming from the parliamentary elections, the addition of new conflicts for MPs, the re-establishment of the State Council as the highest administrative court (which, however, was constituted and operated only under the Constitution of 1927), the improvement of the protection of judicial independence and the establishment of the non-removability of public employees. Finally, for the first time, the Constitution provided for mandatory and free education for all, and declared Katharevousa

(i.e. archaising "purified" Greek) as the "official language of the Nation".

The first major wave of growth came in the 1860s and 1870s. After the crisis of the Crimean War - when the impasses to which an irredentist policy had led the country became apparent - priorities shifted towards economic development. Several factors contributed to a climate that helped attract foreign investment into Greece. One of the most important was the international recession which escalated in 1873, and led to a drop in interest rates abroad. From 1878 on, with the settlement of foreign debts contracted in the past and the comparatively higher interest rates Greece offered in relation to those of the European money markets, there was a rise in capital flowing into Greece from the West in the form of foreign loans, a trend that was at that time observed in other countries on the periphery as well. At the same time, the Agrarian Reform of 1871 was one of the most important domestic changes. The smallholdings it created promoted intensive cultivation of things like the Corinthian currant. The increase in currant exports accelerated the upward course of the economy. Alexandros Koumoundouros marked these two decades. His work became the starting point for Charilaos Trikoupis, the politician who dominated the political stage during the last quarter of the century. He implemented an investment programme that aimed at the construction of large infrastructure works. These works were mainly financed through foreign loans, which in the 1880s were easy to raise. At the beginning of the 1890s, however, it became clear that the country's borrowing capacity had been exhausted, a fact which led to the bankruptcy of 1893.

One thing that has to be pointed out is that the policy of Trikoupis was aimed at modernizing the Greek economy, in other words, bringing it into line with the rates of economic development in the Western world, by adopting the economic model used in England. His plan moreover did not focus only on economic matters but equally on the reorganization of the state and the political system. And it is in the light of these objectives that the precarious practice of over-borrowing has to be viewed.

Economic developments follow a reasoning of their own and do not fall under conventional patterns. General economic trends cover large periods, they coincide however with the events of the conjuncture of circumstances. The agricultural production remains the dominant factor in the agricultural life of the country throughout the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. The economic developments of the beginning of the twentieth century are determined to a large extent by the modernizing economic policy adopted by Harilaos Trikoupis in the previous phase and its consequences. The bankruptcy of 1893 resulted to establishment of the International Financial Control of 1898, which at the same time was related to the obligations imposed by the 1897 defeat. Large works such as the railways, that have been the basic choices of the Trikoupist period, are completed in this phase and positively affect the whole of economy. Shipping is in a constant process of growth with the definite passage from sail to steam.

Between 1898 and 1909 economy begins to recover. The policy of Georgios Theotokis, prime-minister for the greatest part of the period, achieves a relative monetary and exchange stability. At the same time, performance in foreign trade has improved, whereas the slight excess of imports over exports is counter-balanced by the invisible resources originating from shipping and immigration abroad. Some efforts are observed in the development of industry to no avail though. The raisin issue held a prominent partr in the agricultural economy of southern Greece of the time and triggered social disturbances, which had no spectacular aftermath however.

Interest in the banking sector is not as intense as in the previous phase. This trend resurfaces in the 1910s. As concerns taxation, indirect taxation and the relatively small participation in public burdens of high-income households are still the dominant trend.

In the monetary level an improvement of the exchange status of drachma is observed which is related to the improvement of public finance.

The amelioration of the country's finance creates the social preconditions for the military coup of Goudi in 1909 and the ensuing overall attempt for recovery by Eleftherios Venizelos, the military venture between 1912 and 1922 in particular. The state in that period had to face acute economic problems which are justified by the continuous involvement in war. War mobilized on the one hand the productive human resources of the country, on the other hand it had exhausted the potential of public finance. In that period the Greeks of the Diaspora transfer part of their activities to Greece and participate more actively in the economo-social affairs of the Greek state.

After the entrance of the country in the First World War, an allied aid was anticipated, the so-called Allied Credits. On this basis the Asia Minor Campaign has been planned. Their interruption after the political change of November 1920 with the reinstatement of King Constantine I in combination with the inability of contracting new loans contributed -from the economic point of view- to the debacle of the front. The Asia Minor Catastrophe finds the country in a pathetic economic state.

The destruction brought about by the war of 1940-1944 was so extensive that, despite the relief supply sent by international organizations (UNRRA etc.), the country was unable to enter effectively in a rehabilitation course. The breakdown of communication networks and of the countrys public infrastructure, the shrink of the gross national product (GNP) and internal political instability led to a steep rise of inflation and undermined any attempt of recovery to prewar levels.

Moreover, political oppositions within Greece combined with international tensions due to antagonism between the two great powers (USA and USSR) that emerged after World War II, promoted the implication of the country in the rising Cold War. The declaration of the Truman Doctrine, in March 1947, brought the country under the influence and control of the USA and of the western coalition that was being formed, which aimed to restrain communism from spreading on a worldwide scale. Extensive financial aid to Greece, which was stipulated in the Marshall Plan, contributed to an evolutionary process in economy and politics after 1948. International isolation to which the communist leadership had been reduced, after the -until then- friendly Titos Yugoslavia had blocked its borders, stressed the incompetence of the Balkan policy of KKE (Greek Communist Party) and contributed to the governmental prevalence.

In the second half of the decade 1940-50 it is estimated that over 100,000 people lost their lives, while at least 700-750,000 left their homes, which situated mainly on the massifs of Central and North Greece because of the civil war. At the same time, a large number of citizens was exiled or imprisoned, while 80,000 people approximately fled to the eastern countries. In the beginning of 1950, both the social and physical physiognomy of the country had altered radically in regard to the prewar past. Many among those who had left the mountains, would never come back, as the social network had collapsed, ethnic minorities (in West Macedonia and Thrace) abandoned the country and social groups (mountainous rural population) resorted to urbanization and emigration.

For the first time during 1952-63, an urbanization procedure was brought about in the Greek population, during which the ratio rural-urban sector outweighed in favour of the latter. The main place of assimilation was the urban complex of Athens. At the same time, the influx from the country to the cities was accompanied by a rapid growth of the emigration flow. The structural changes that were brought about, were revealed through labour (forms of occupation), consumption and government measures concerning the stabilization and growth of economy.

The devaluation of the currency in 1953 (Spyridon Markezinis) created a new financial hierarchy: increase of imports, boost in commercial consumption, combating against inflation, but also a deficit in the balance of trade. The expansion of public investments, despite their often confined orientation, was a decision of historical importance made by the Karamanlis governments. The growth rate of the GNP with the contribution of invisible resources was explosive (7% annually), but did not reflect phenomena like industrial stagnancy and the lack of central programming in agriculture.

One of the primary concerns for the governments of the period 1956-61 was how to deal with productivity, underemployment and sufficiency of resources. Despite the fact that agriculture continued to be the largest productive sector, the rural world had undergone radical changes in relation to the interwar period. The growth of communication networks, the diffusion of cinema, the emergence of tourism brought wider social strata closer to the way of living of industrial societies.

During the 19th century, foreign policy in Greek political life constituted the main factor shaping internal policy, because Greece was bound by the guardianship of forces which did not miss any opportunity to interfere decisively with the regime, governance and political life of the country. The new state's territory included only a proportion of the 1821 rebels, and a much smaller number of the Greek Orthodox peoples in general. Liberation was the central political axis of the new state; setting free the enslaved compatriots was considered a 'natural order' and a religious obligation, whereas the issues of foreign policy frequently motivated many people who took action in favour of an expansionist policy, even if that was unfeasible. Finally, foreign policy was the touchstone for royalty and the politicians; it could legitimize people, institutions, ideologies and practices.

The gap between what was desired and what was feasible is typical of Greek foreign policy in the 19th century; the distance between the goal and the preparation for its achievement; the distance between dreams and reality. Over everything lies the Greeks' high opinion of themselves; the high opinion of their descent, of their mission; the Great Idea showed the way for Greek foreign policy over three-quarters of a stormy century.

In order to follow the facts relating to foreign policy, the actions of diplomacy, treaties and military action, one has to take into consideration many other aspects: institutions, and the political, diplomatic and legal framework in which they were found; the people and the roles they had to play, the discourse which developed either through texts or public action in general.

The victorious Balkan Wars (First and Second Balkan War) gained for Greece the territories of Macedonia, Epirus and Crete and dominion over the islands of the northeastern Aegean.

The Greek foreign policy of that period bears the mark of the personality and the handlings of Eleftherios Venizelos. The Cretan statesman passionately supported Greek expansion, in the framework of the conjunction of circumstances of the period while being harnessed to the democratic countries of western Europe and Great Britain in particular.

The other factor that contributed to the shaping of the foreign policy of the period was King Constantine I, who supported Greek neutrality, favouring the Central Powers, due to actual kinship and politico-ideological affinities with them. Around him rallied those opposing the Venizelist policy as a whole, at the same time reacting to the domestic socio-political reforms introduced by Venizelos. The acute disagreement of the Prime Minister and the King led to the National Schism that terminated with the predominance of the Venizelists and the entrance of Greece in the war on the side of the British and the French.

During the First World War and amidst the colonial competition of the Great Powers in the area of the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean more generally, Greece tried to secure the largest possible territorial gains from the crumbling Ottoman empire.

The Asia Minor Campaign was launched in an attempt of Greece, being an ally of the victorious Powers and member of the Paris Peace Conference, to fulfil her pursuits.

With the short-lived Treaty of Sèvres Greece acquired for a while her largest territorial expansion, gaining the Dodecanese islands, Thrace and a zone in western Asia Minor around Smyrna. The "Greater Greece of the two continents and of the five seas" became an actuality or a brief period. The competition however of the interests of the western allies and the reversal of their Eastern policy, in combination with the political change of November 1920 that restored to the throne the undesirable to the allies King Constantine I, overturned this actuality. The venture of the Asia Minor Campaign terminated with the definite departure of the Greek element from its hearths in Thrace, Pontos and Asia Minor.

From the "Greece of the Treaty of Sevres" only western Thrace and the ratified dominion over the Aegean islands remained. As a whole, in the period 1912-22 Greece doubled her territory and population acquiring her definite borders with the exclusion of the Dodecanese islands, that continued to be under Italian occupation until the end of the Second World War. In the same period the remaining national claims, northern Epirus and Cyprus, will be the object of negotiations, but the chance of their becoming annexed to the Greek state will be definitely eliminated.

From the following period, the inter-war period, Greek foreign policy will fully change course, abandoning every Great Idea aspiration and putting as objective the peaceful co-existence with Turkey and the other Balkan states and the defence of national territory from every possible threat.

The postwar economic flourishing of Europe - which had to deal with an enormous lack of manpower in its effort of reconstruction - led after 1956 mainly rural strata that faced financial inactivity, to turn to mass emigration in quest of a better fortune. After the supply of American aid was over, the importation of foreign capital in every possible way in order to boost the local, insufficient business activity was considered a cure-all, which would lead the country to an industrialization track.

However, despite the benefits (tax exemptions etc.) granted to foreign capitalists, the total of foreign investments in Greece until 1960 was rather low. The accession of Greece to NATO in 1952, as the Cold War was escalating, institutionalized the American control on the foreign policy front and determined the relations of Greece with its neighbouring countries, using criteria often opposite to its internal necessities. The Greek military participation in the Korean campaign (1950) stressed this particular orientation.

At the same time, the declaration of the anti-colonist struggle in Cyprus against British occupation (1955) set off a large number of mass and dynamic social reactions in Greece in favour of the union with the "Ethniko Kentro" (National Centre). What characterized that period was the discrepancy between Greek leaderships that were closely dependent on the British and the Americans and the constantly increasing anti-British movement expressed through a series of militant demonstrations and protests throughout the 1950s and the '60s. In 1959, Britain, Turkey, Greece, the Greek-Cypriots and the Turkish-Cypriots reached an agreement in Zurich and London, thus sealing all negotiations concerning the Cyprus problem. Moreover, this agreement determined the course of the issue itself, as well as that of relevant discussions for decades.

At the same time it was a modern state, which means European, Western, or at least it intended to become one. This was also proclaimed in the political declarations and especially in the constitutions of the years of the Revolution. Consequently, the establishment of a centralized government model and of Western institutions was inevitable but also urgent. At the same time it was a difficult venture. The composition and consolidation of administrative and repressive state mechanisms was followed by processes of violent unification and homogenization of a society that remained traditional, that is, a society split into many regional and relatively independent political centres. These local political centres had to be disbanded, enfeebled and eliminated, as the central power in the modern state is the only legitimate source of political power.

In all modern states, politics is where society meets and interacts with political power, or the state itself. In the case of the Greek state, politics was the field where a political power with all the features of a modern state met a society which remained intensely traditional. The formation of the field of politics on the basis of modern authorities of function affected the terms of social reproduction of the regional social elites. In the first years, in the 1830s, the reaction of these local elites was expressed through traditional ways of protest and mainly through regional insurrections. However, from the beginning of the 1840s the constitution and the elections - both modern institutions and procedures - comprised the basic claims of these traditional groups. Their objective was nothing more than the redefinition of the political field in the direction of a more favourable redisposition of the power correlations. This was achieved with the movement of 1843. The Constitution of 1844 and the first elections do not show the victory of the traditional element over the modern. They signify the incorporation of the traditional political leaderships of Greek society in a modern political system, the acceptance of its terms and the consolidation of its institutions. In a sense, in 1843 the central political scene becomes the chief point of emergence of the socio-political conflicts. From then on, and for the entire 19th century, the consolidation and extension of the parliamentary institutions, the type of the regime and the limits of royal intervention in politics, would virtually monopolize every aspect of domestic political life.

During the period 1897-1922 very important events and headlong developments determine the evolution of Greece and decisively contribute to its formation as a modern state.

It is a period of spectacular changes, critical choices, acute crises, a ten year war adventure, which ends up in the territorial expansion of Greece on the one hand and the dramatic termination of the Asia Minor Campaign on the other hand and aims at the formation of a state radically different from that of the past.

The period begins with an event-landmark: the defeat in the Greco-Turkish war of 1897. The defeat has been perceived as a huge blow, causing universal disappointment apart from putting the state and its mechanism structures, the traditional political world and the royal dynasty as concerns their efficiency in managing national issues under doubt. The defeatist attitude and the sense of "shame" were intensified even more by the establishment of the International Financial Control Commission, that would oversee the payment of a war indemnity to Turkey, as well as settle the overall external debts, being the result of the state's bankruptcy in 1893. The economic and national crisis, that is a double failure, both in the economic sector and the policy of irredentism breed a climate of disillusionment and introspection. By 1909 there is no change whatsoever. Two parties alternate in power: the Trikoupist party headed by Georgios Theotokis and the Deliyannist party with Theodoros Deliyannis himself as leader and, after his assassination in 1905, his successors, Dimitrios Rallis and Kyriakoulis Mavromikhalis, leaders of two different parties, originating though from the Deliyannist party. No particular progress has been made apart from some efforts by the governments of Theotokis, in the economic sector in particular, for recovery. On the contrary, the towering economic crisis and the plight of various social groups, the continuous disclosure of the weaknesses of the old political status cause an increasing discontent and breed the conditions for the development of reaction.

1909, the year that the Military coup of Goudi broke out, is taken as a starting point for the division of Greek history marking the beginning of a ten-year period (1910–20) of progress and shaping of Greece as a modern state. It coincides with the rise of the middle bourgeois class, which, reinforced by the economic development of the last years of the nineteenth century, claim from the old political bourgeois oligarchy their political representation and the creation of those instutional preconditions that would facilitate their economic activity.

The Cretan statesman Eleftherios Venizelos will emerge as a leading figure, who will represent the attempt at transforming the Greek society into a capitalist one and organizing the state after the models of western republics. The urban modernization attempted by Venizelos will go hand in hand in perfect harmony with national integration, under the form of irredentism and the incorporation of the New Territories and their inhabitants in the national state. These two objectives, economic and political modernization on the one hand and the militant pursuit of the Great Idea in the conjuncture of circumstances of the First World War on the other hand, constitute the essence of Venizelism.

Reaction to both urban modernization and irredentism gave birth to anti-Venizelism. The overall social and political contrast among both various social groups and old and new populations, incorporated with the territorial expansion being the result of the victories reaped during the Balkan wars, will be personified in the conflict between the prime-minister Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine I about the stance of Greece in the First World War. It will acquire the dimensions of a National Schism, that culminated in the period 1915-17 with the creation of two Greek states, an anti-Venizelist one in the territory of Old Greece and a Venizelist one in the area of the New Territories.

In the period 1917-20, during the second phase of Venizelist rule, the modernizing effort is kept on that has been inaugurated in the period 1910-15 and has been checked by the developments of the Schism and war.

In the 1920 elections, while the Asia Minor Campaign was under way, the Greeks worn out by the ten-year war venture voted against the Liberals. The anti-Venizelists despite their pre-election promises, pursued the Asia Minor war, reinstating to the throne the undesirable to the Western allies King Constantine I. This fact served the allies as a pretext to forsake Greece in Asia Minor, since their interests dictated by now the support of Kemal. During this period developments in the domain of foreign policy are dominant. Within the different by now international correlation of powers, that would annul Greek aspirations in Asia Minor, wrong military choices and economic exhaustion brought about an even more painful Catastrophe in the summer of 1922, uprooting the Greek populations of the East from their homelands and turning them into refugees in Greece

After the debacle of the front Greece is in a tragic plight. Crowds of refugees and soldiers throng the country. A group of officers headed by Nikolaos Plastiras takes over power, pursuing chiefly a purge for the national tragedy. This is the "Revolution of 1922". Within this context the Trial of the Six ringleaders of the Catastrophe took place, that led to their death sentence, a fact that exacerbated the heavy climate of the time.

At the same time, social tensions showing the extent and importance of change were particularly felt in urban centres. If rural areas were a source of mistrust and resistance to every innovation, the cities and the capital in particular generally reflected individual instances of breaking with the past. The formation of an administrative mechanism led to the gradual shaping of a social group which was new and at the same time composed of many people: the civil servants. The development of the secondary and tertiary sectors of production and the gradual prevalence of salaried work caused the middle classes to grow in number, and created the conditions for the formation of working classes. These new social categories believed in new values (among which was literacy), and in their daily life they adopted different (Western-like) models in clothing, housing, nutrition, hygiene, music, entertainment and social events. It was certainly a different kind of Greek society.

In short, the Greek society of the 19th century experienced a fundamental paradox which could schematically be described as the co-existence of the old and the new, traditional and modern. This paradox existed throughout the whole of society, (re)shaped it and consequently constituted its basic feature. In the light of this, the mistrust and resistance on the part of traditional groups and rural areas in general did not suggest the persistence of the old, but one of the ways of adjusting to the new.

The period 1897-1922 is characterized by remarkable innovations permeating Greek society. The small kingdom of the nineteenth century acquires to a large extent the borders of the present day.

Territorial expansion is accompanied by a series of reforms in the social, economic, political and cultural sector, taking place after the coup of Goudi and politically expressed by the Venizelist bloc. In the context of these developments a social rift, manifested with the National Schism, became manifest in a period when the country was entering the swirl of international competition and the Great War. Conflicting views for the position of the country in the international field ultimately reflect a different approach concerning the course of development of the structures of Greek society.

In the period under examination the population and the territory of the country almost double. At the same time, considerable movements of people are observed. On the one hand in the beginning of the twentieth century a mass immigration movement chiefly towards the USA took place. On the other hand there has been a movement towards the interior, with the arrival of Greek refugees from the areas where military operations were under way or from areas being under the control of foreign powers.

The largest part of the labour force of the country is occupied in the sector of agriculture.

In this context the Thessalian question arises, that evolved into the most important social mobilization of the period with the outbreak of revolts in the 1910's. For its resolution but also the settlement of respective problems created by the presence of refugees and landless in the new territories the agricultural reforms of 1917 took place. To the same direction a series of institutional innovations occurred in the field of agriculture, such as the establishment of agricultural co-operatives and the Ministry of Agriculture.

The growth of urban centres follows a rapid pace, their population increases as well as the activities taking place in their space. New large cities with a tradition in the economic and cultural field such as Thessaloniki, Ioannina and Kavala are incorporated in the Greek territory. In the cities in-migrators are gathered and form the first labour class. There is a considerable problem of unemployment, housing and sanitation conditions whereas certain groups of people live in the margin of the city's activities. After 1910 the first form of the labour movement is observed, whereas the state institutes for the first time a protective social policy. Various traditional petit bourgeois strata of small businessmen and lower rank civil servants continue to be present.

At the same time, along with all the war ventures and the internal crises, Athens experiences the climate of the belle epoque. A new business bourgeois class develops, tending to supplant the older formed upper social class, the old "tzakia", directly related to the state mechanism.

Very intense during this period has been the struggle of the demoticists for the establishment of demotic Greek, which resulted to a great dispute between them and the supporters of katharevousa. This dispute deteriorated to violent incidents, as was the case with Evangelika and Oresteiaka. Demoticism facilitated the dissemination of various ideas and brought together the Socialist intellectuals with the educational reform. In the field of the exercise of policy and ideology, a group of young scientists -the "Group of Sociologists"- makes its appearance pursuing radical reforms. At the same period Georgios Skliros with his work To Koinoniko mas Zitima (Our Social Issue) lays the foundations for a Marxist approach of Greek society.Also for the first time an anti-monarchist discourse is articulated in Greece and the prospect of a Republic is put forward. It is a transition period for the claims of women, it marks the passage from demands for participation in education and work to the claim for political participation.

In the same period outside the national centre the Greek communities of the Ottoman east but also the Greek diaspora live and develop along the Greek actuality, until the dramatic events of the end of the period overturned the old status.

The debate on cultural matters was marked by intense disputes. The most important one was between the scholars of the Heptanesian School and the First Athenian School. The main choices that had already been made in the 1820s by Kalvos and principally by Solomos in the language, forms of expression and sources of inspiration did not affect the poets of the capital. Further development of the demotic was held back by the prevalence of the katharevousa (the purist Greek language) which, over time, became increasingly concerned with archaizing the language. One example is Solomos, whose quest for subjects and forms of expression through the language of simple people, popular songs and the epics of the Cretan tradition, was either not mentioned or was publicly criticized. The accusations against the Zakynthian poet were that he neglected the 'virtues' of the katharevousa while trying to express himself poetically with a mediocre linguistic organ, the popular language. The poetic contribution of Solomos and of the Heptanesian School in general remained on the sidelines of the Athenian effort for the greater part of the period. The atmosphere would change much later with the appearance of Kostis Palamas in literature. With two of his texts (released in 1886 and 1889) K. Palamas contributed to the acknowledgement of the poets of the Heptanesian School, mainly Solomos and Kalvos, and paid tribute to their linguistic organ, the demotic Greek language.

1897 was a clear turning point in Greek intellectual awareness and inaugurated a new era for philosophy, literature and the arts throughout the country.

The disillusionment and criticism following the defeat in war, the vision of a new Greece, patriotism, national integration, social transformation, the movement of people from the countryside to the city, the pursuit of a national character in arts, the introduction of philosophical, socio-political concepts and artistic movements from Europe - all these had complex repercussions on the cultural and intellectual pursuits of the period.

Poetry was influenced by European Symbolism. The most significant intellectual figures imbued their work with their views about the times and the fate of Hellenism. Kostis Palamas's most important work explored national issues but were also visionary. A poet of the Greek diaspora, a Greek from Alexandria, Constantine Cavafy, created a body of poetic work unparalleled in Modern Greek and world literature. At the same time, three prominent figures of modern Greek literature made their appearance: Angelos Sikelianos, Nikos Kazantzakis and Kostas Varnalis.

Philosophical and political concepts, especially socialist ideals originating from Europe, shaped the ideological and artistic world. These new views were disseminated chiefly through periodicals, especially literary ones, which were vehicles of discussion for the intellectuals of the time, literary criticism and innovative tendencies that were intimately linked with the issues of language and education.

Prose writers tended to cultivate demotic Greek and either focused on folkloric realism (ethography) or cultivated social prose. The Macedonian Struggle, national integration and faith in Greek potential inspired other intellectuals and writers, and national issues and Hellenism in general were the core elements in much of their work.

Theatre in general and playwriting in particular enjoyed a revival in this period, when a veritable Greek dramatic tradition was created. Music also acquired, for the first time, a national character and a national Greek school developed.

European movements spread to Greece and were transcribed into a Greek artistic idiom. New tendencies in painting and sculpture began to put aside the academicism of the previous period, which still, however, dominated, whereas engravingand photographydeveloped artistic independence. Important artists, such as Konstantinos Parthenis, Konstantinos Maleas and Yorgos Bouzianis emerged in this period; the latter marked the shift from tradition to modernism.

In general this is an age that saw the transition from traditional to modern art forms - forms that only developed to their full capacity in the subsequent, inter-war period. But in these years the painter Theophilos Hatzimichail produced his unique work, illustrating the uninterrupted Greek tradition and emerging as the teacher of 'Greekness', as acknowledged by the writers of the following generation of the 1930s.

The arts thrived and more and more painting exhibitions were organized (collective and individual) from 1901 onwards. Etaireia Philotechnon (Society of the Friends of Art) organized exhibitions at Koupas Megaron, Elliniki Kallitechniki Etaireia (Hellenic Arts Society) at Zappeion. In 1900 the first arts society, Syndesmos Ellinon Kallitechnon (Society of Greek Artists) was founded and was followed by others. In 1900 the National Gallery was established.

Syllogos pros diadosin ton ofelimon vivlion (The Society for the dissemination of useful books) was established in 1898 and contributed much to intellectual life. The study of the Greek past developed apace.

The main ideological concern of Greek society at the beginning of the twentieth century was the Language Question. The struggle for the dominance of demotic Greek, which was related to demands for wider socio-political reforms, was inseparably linked to educational reform. It brought together many of the prominent figures of Greek letters and culture, despite the differences among them, which chiefly concerned the socio-political connotations of demoticism. The era was characterized by great militancy and has been called the 'heroic age of demoticism'. For the first time, demoticists came together in organizations and took on a more dynamic role in the intellectual life of the country.

Space, as landscape, became the subject of a Greek aesthetic theory, the creation of Periclis Yannopoulos, but also inspired painting, which revealed and lent artistic form to Greek landscape and light.

As cities grew, the urban milieu invaded literature, which thus followed the movements of population and social transformation (except in the case of the countryside, which was depicted in folkloric realism or ethography).

Architecture pursued the Neo-classical style of the previous century, but at the same time new forms began to emerge: the pursuit of a Greek architecture, based on the study of traditional, and especially Byzantine, architecture. These ideas were theoretical only at this stage, and were only implemented by future generations.

The enthusiasm and euphoria that prevailed immediately after the liberation (autumn of 1944) ignited sudden changes in the intelligentsia and to the wider intellectual environment. The perception about art that was shaped in the 30s and remained the same during the Occupation was radically transformed. Subjectivity and individualism that were prevalent in various fields, such as literature, were replaced by the glorification of collectivity, of the notion of "people", of "nation" etc.