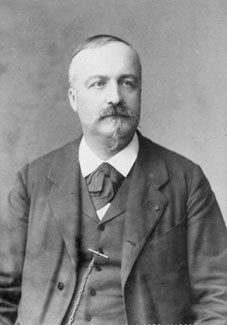

Marie Alfred Cornu

Encyclopedia

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

physicist

Physicist

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole...

. The French generally refer to him as Alfred Cornu.

Cornu was born at Orléans

Orléans

-Prehistory and Roman:Cenabum was a Gallic stronghold, one of the principal towns of the Carnutes tribe where the Druids held their annual assembly. It was conquered and destroyed by Julius Caesar in 52 BC, then rebuilt under the Roman Empire...

and was educated at the École polytechnique

École Polytechnique

The École Polytechnique is a state-run institution of higher education and research in Palaiseau, Essonne, France, near Paris. Polytechnique is renowned for its four year undergraduate/graduate Master's program...

and the École des mines

École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris

The École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris was created in 1783 by King Louis XVI in order to train intelligent directors of mines. It is one of the most prominent French engineering schoolsThe École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris (also known as Mines ParisTech, École des Mines de...

. Upon the death of Émile Verdet

Émile Verdet

Émile Verdet was a French physicist. He worked in magnetism and optics, editing the works of Augustin-Jean Fresnel. Verdet did much to champion the early theory of the conservation of energy in France through his editorial supervision of the Annales de chimie et de physique.The Verdet constant is...

in 1866, Cornu became, in 1867, Verdet's successor as professor

Professor

A professor is a scholarly teacher; the precise meaning of the term varies by country. Literally, professor derives from Latin as a "person who professes" being usually an expert in arts or sciences; a teacher of high rank...

of experiment

Experiment

An experiment is a methodical procedure carried out with the goal of verifying, falsifying, or establishing the validity of a hypothesis. Experiments vary greatly in their goal and scale, but always rely on repeatable procedure and logical analysis of the results...

al physics at the École polytechnique, where he remained throughout his life. Although he made various excursions into other branches of physical science, undertaking, for example, with Jean-Baptistin Baille

Baptistin Baille

Baptistin Baille was born Jean-Baptiste Baille in France, in 1841 and he died in 1918. He was a professor of optics and acoustics at the École de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles in Paris and a close friend of Paul Cézanne, the impressionist artist, and of Émile Zola who would later become a...

about 1870 a repetition of Cavendish

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish FRS was a British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen or what he called "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper "On Factitious Airs". Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and...

's experiment for determining the gravitational constant

Gravitational constant

The gravitational constant, denoted G, is an empirical physical constant involved in the calculation of the gravitational attraction between objects with mass. It appears in Newton's law of universal gravitation and in Einstein's theory of general relativity. It is also known as the universal...

G, his original work was mainly concerned with optics

Optics

Optics is the branch of physics which involves the behavior and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behavior of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light...

and spectroscopy

Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the study of the interaction between matter and radiated energy. Historically, spectroscopy originated through the study of visible light dispersed according to its wavelength, e.g., by a prism. Later the concept was expanded greatly to comprise any interaction with radiative...

. In particular he carried out a classical redetermination of the speed of light

Speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, usually denoted by c, is a physical constant important in many areas of physics. Its value is 299,792,458 metres per second, a figure that is exact since the length of the metre is defined from this constant and the international standard for time...

by A. H. L. Fizeau

Hippolyte Fizeau

Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau was a French physicist.-Biography:Fizeau was born in Paris. His earliest work was concerned with improvements in photographic processes. Following suggestions by François Arago, Léon Foucault and Fizeau collaborated in a series of investigations on the interference of...

's method (see Fizeau-Foucault Apparatus

Fizeau-Foucault apparatus

The Fizeau–Foucault apparatus was designed by the French physicists Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault for measuring the speed of light. The apparatus involves light reflecting off a rotating mirror, toward a stationary mirror some 20 miles away...

), introducing various improvements in the apparatus, which added greatly to the accuracy of the results. This achievement won for him, in 1878, the prix Lacaze and membership of the French Academy of Sciences

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research...

(l'Académie des sciences), and the Rumford Medal

Rumford Medal

The Rumford Medal is awarded by the Royal Society every alternating year for "an outstandingly important recent discovery in the field of thermal or optical properties of matter made by a scientist working in Europe". First awarded in 1800, it was created after a 1796 donation of $5000 by the...

of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. In 1892, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

. In 1896, he became president of the French Academy of Sciences. In 1899, at the jubilee commemoration of Sir George Stokes

George Gabriel Stokes

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet FRS , was an Irish mathematician and physicist, who at Cambridge made important contributions to fluid dynamics , optics, and mathematical physics...

, he was Rede lecturer

Rede Lecture

The Sir Robert Rede's Lecturer is an annual appointment to give a public lecture, the Sir Robert Rede's Lecture at the University of Cambridge. It is named for Sir Robert Rede, who was Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in the sixteenth century.-Initial series:The initial series of lectures ranges...

at Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

, his subject being the wave theory of light

Light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that is visible to the human eye, and is responsible for the sense of sight. Visible light has wavelength in a range from about 380 nanometres to about 740 nm, with a frequency range of about 405 THz to 790 THz...

and its influence on modern physics; and on that occasion the honorary degree

Honorary degree

An honorary degree or a degree honoris causa is an academic degree for which a university has waived the usual requirements, such as matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations...

of D.Sc. was conferred on him by the university. He died at Romorantin

Romorantin

Romorantin is a traditional French variety of white wine grape, that is a sibling of Chardonnay. Once quite widely grown in the Loire, it has now only seen in the Cour-Cheverny AOC. It produces intense, minerally wines somewhat reminiscent of Chablis....

on April 12, 1902.

The Cornu spiral, a graphical device for the computation of light intensities in Fresnel

Augustin-Jean Fresnel

Augustin-Jean Fresnel , was a French engineer who contributed significantly to the establishment of the theory of wave optics. Fresnel studied the behaviour of light both theoretically and experimentally....

's model of near-field diffraction

Fresnel diffraction

In optics, the Fresnel diffraction equation for near-field diffraction, is an approximation of Kirchhoff-Fresnel diffraction that can be applied to the propagation of waves in the near field....

, is named after him. The spiral (or clothoid) is also used in geometrical road design. The Cornu depolarizer is also named after him.