George Gabriel Stokes

Encyclopedia

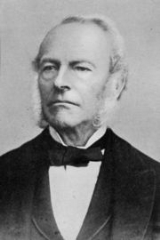

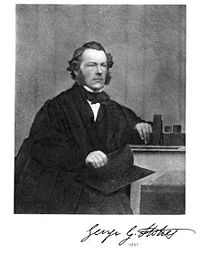

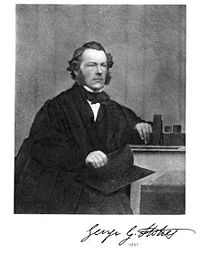

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet FRS (13 August 1819–1 February 1903), was an Irish

mathematician

and physicist

, who at Cambridge

made important contributions to fluid dynamics

(including the Navier–Stokes equations), optics

, and mathematical physics

. He was secretary, then president, of the Royal Society

.

of Skreen

, County Sligo, Ireland

, where he was born and brought up in an evangelical

Protestant family. After attending schools in Skreen, Dublin, and Bristol

, he matriculated in 1837 at Pembroke College, Cambridge

, where four years later, on graduating as senior wrangler and first Smith's prize

man, he was elected to a fellowship. In accordance with the college statutes, he had to resign the fellowship when he married in 1857, but twelve years later, under new statutes, he was re-elected. He retained his place on the foundation until 1902, when on the day before his 83rd birthday, he was elected to the mastership. He did not hold this position for long, for he died at Cambridge on 1 February the following year, and was buried in the Mill Road cemetery

.

were formally offered to Pembroke College and to the university by Lord Kelvin

. Stokes, who was made a baronet in 1889, further served his university by representing it in parliament from 1887 to 1892 as one of the two members for the Cambridge University constituency

. During a portion of this period (1885–1890) he also was president of the Royal Society

, of which he had been one of the secretaries since 1854. Since he was also Lucasian Professor at this time, Stokes was the first person to hold all three positions simultaneously; Newton held the same three, although not at the same time.

Stokes was the oldest of the trio of natural philosophers, James Clerk Maxwell

and Lord Kelvin

being the other two, who especially contributed to the fame of the Cambridge school of mathematical physics in the middle of the 19th century. Stokes's original work began about 1840, and from that date onwards the great extent of his output was only less remarkable than the brilliance of its quality. The Royal Society's catalogue of scientific papers gives the titles of over a hundred memoirs by him published down to 1883. Some of these are only brief notes, others are short controversial or corrective statements, but many are long and elaborate treatises.

remarked in his Rede lecture

of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

s and some cases of fluid motion. These were followed in 1845 by one on the friction of fluids in motion and the equilibrium and motion of elastic solids, and in 1850 by another on the effects of the internal friction of fluids on the motion of pendulum

s. To the theory of sound

he made several contributions, including a discussion of the effect of wind

on the intensity of sound and an explanation of how the intensity is influenced by the nature of the gas in which the sound is produced. These inquiries together put the science of fluid dynamics

on a new footing, and provided a key not only to the explanation of many natural phenomena, such as the suspension of cloud

s in air, and the subsidence of ripples and waves in water, but also to the solution of practical problems, such as the flow of water in rivers and channels, and the skin resistance of ships.

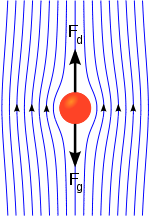

His work on fluid motion and viscosity

His work on fluid motion and viscosity

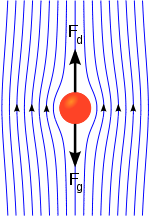

led to his calculating the terminal velocity for a sphere falling in a viscous medium. This became known as Stokes' law

. He derived an expression for the frictional force (also called drag force) exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers.

His work is the basis of the falling sphere viscometer

, in which the fluid is stationary in a vertical glass tube. A sphere of known size and density is allowed to descend through the liquid. If correctly selected, it reaches terminal velocity

, which can be measured by the time it takes to pass two marks on the tube. Electronic sensing can be used for opaque fluids. Knowing the terminal velocity, the size and density of the sphere, and the density of the liquid, Stokes' law can be used to calculate the viscosity of the fluid. A series of steel ball bearing

s of different diameter is normally used in the classic experiment to improve the accuracy of the calculation. The school experiment uses glycerine as the fluid, and the technique is used industrially to check the viscosity of fluids used in processes.

The same theory explains why small water droplets (or ice crystals) can remain suspended in air (as clouds) until they grow to a critical size and start falling as rain

(or snow

and hail

). Similar use of the equation can be made in the settlement of fine particles in water or other fluids.

The CGS unit of kinematic viscosity was named "stokes" in recognition of his work.

. His optical

work began at an early period in his scientific career. His first papers on the aberration of light

appeared in 1845 and 1846, and were followed in 1848 by one on the theory of certain bands seen in the spectrum

.

In 1849 he published a long paper on the dynamical theory of diffraction

, in which he showed that the plane of polarization must be perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Two years later he discussed the colours of thick plates.

In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of wavelength

In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of wavelength

of light, he described the phenomenon of fluorescence

, as exhibited by fluorspar and uranium glass

, materials which he viewed as having the power to convert invisible ultra-violet radiation into radiation of longer wavelengths that are visible. The Stokes shift

, which describes this conversion, is named in Stokes' honor. A mechanical model, illustrating the dynamical principle of Stokes's explanation was shown. The offshoot of this, Stokes line

, is the basis of Raman scattering

. In 1883, during a lecture at the Royal Institution

, Lord Kelvin said he had heard an account of it from Stokes many years before, and had repeatedly but vainly begged him to publish it.

In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarized light from different sources, and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection

In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarized light from different sources, and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection

exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarization. About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862 he prepared for the British Association

a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar

, transparent calcite

crystals.

A paper on the long spectrum of the electric light bears the same date, and was followed by an inquiry into the absorption spectrum of blood

.

bodies by their optical properties was treated in 1864; and later, in conjunction with the Rev. William Vernon Harcourt

, he investigated the relation between the chemical composition and the optical properties of various glass

es, with reference to the conditions of transparency and the improvement of achromatic

telescope

s. A still later paper connected with the construction of optical instruments discussed the theoretical limits to the aperture of microscope objectives.

In other departments of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat

In other departments of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat

in crystal

s (1851) and his inquiries in connection with Crookes radiometer

; his explanation of the light border frequently noticed in photograph

s just outside the outline of a dark body seen against the sky (1883); and, still later, his theory of the x-ray

s, which he suggested might be transverse waves travelling as innumerable solitary waves, not in regular trains. Two long papers published in 1840—one on attractions and Clairaut's theorem

, and the other on the variation of gravity at the surface of the earth—also demand notice, as do his mathematical memoirs on the critical values of sums of periodic series (1847) and on the numerical calculation of a class of definite integral

s and infinite series (1850) and his discussion of a differential equation

relating to the breaking of railway bridge

s (1849), research related to his evidence given to the Royal Commission on the Use of Iron in Railway structures after the Dee bridge disaster

of 1847.

.

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at Glasgow

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at Glasgow

. These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had failed to take one essential step in the argument—not perceiving that emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of spectroscopy

These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had failed to take one essential step in the argument—not perceiving that emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of spectroscopy

.

In another way, too, Stokes did much for the progress of mathematical physics. Soon after he was elected to the Lucasian chair he announced that he regarded it as part of his professional duties to help any member of the university in difficulties he might encounter in his mathematical studies, and the assistance rendered was so real that pupils were glad to consult him, even after they had become colleagues, on mathematical and physical problems in which they found themselves at a loss. Then during the thirty years he acted as secretary of the Royal Society he exercised an enormous if inconspicuous influence on the advancement of mathematical and physical science, not only directly by his own investigations, but indirectly by suggesting problems for inquiry and inciting men to attack them, and by his readiness to give encouragement and help.

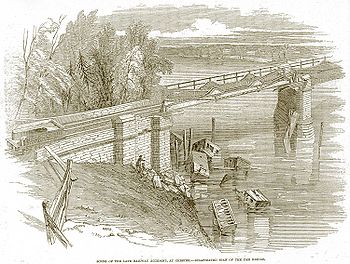

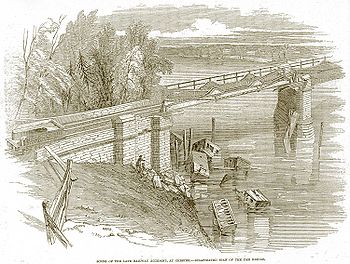

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee bridge disaster

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee bridge disaster

in May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of passing trains. Cast iron

is brittle

in tension or bending

, and many other similar bridges had to be demolished or reinforced.

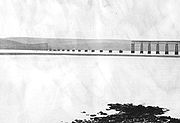

He appeared as an expert witness at the Tay Bridge disaster

He appeared as an expert witness at the Tay Bridge disaster

, where he gave evidence about the effects of wind loads on the bridge. The centre section of the bridge (known as the High Girders) was completely destroyed during a storm on December 28, 1879, while an express train was in the section, and everyone aboard died (more than 75 victims). The Board of Inquiry listened to many expert witness

es, and concluded that the bridge was "badly designed, badly built and badly maintained".

As a result of his evidence, he was appointed a member of the subsequent Royal Commission

into the effect of wind pressure on structures. The effects of high winds on large structures had been neglected at that time, and the commission conducted a series of measurements across Britain

to gain an appreciation of wind speeds during storms, and the pressures they exerted on exposed surfaces.

, a Christian institute founded in response to the evolutionary movement of the 1860s. He gave the 1891 Gifford lectures

. He was also the vice president of the British and Foreign Bible Society and was active in foreign missions doctrinal issues.

, who also selected and arranged the Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of Stokes published at Cambridge in 1907.

Irish

Irish may refer to:*Irish cuisine* Ireland, an island in north-western Europe, on which are located:** Northern Ireland, a constituent country of the United Kingdom** Republic of Ireland, a sovereign state...

mathematician

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

and physicist

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

, who at Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

made important contributions to fluid dynamics

Fluid dynamics

In physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics...

(including the Navier–Stokes equations), optics

Optics

Optics is the branch of physics which involves the behavior and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behavior of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light...

, and mathematical physics

Mathematical physics

Mathematical physics refers to development of mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The Journal of Mathematical Physics defines this area as: "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the development of mathematical methods suitable for such applications and...

. He was secretary, then president, of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

.

Biography

George Stokes was the youngest son of the Reverend Gabriel Stokes, rectorRector

The word rector has a number of different meanings; it is widely used to refer to an academic, religious or political administrator...

of Skreen

Skreen

Skreen is a village in County Sligo, Ireland. It is the birthplace of the poet Thady Connellan and the mathematician and physicist Sir George Gabriel Stokes . It shares its name with a village in County Meath which is locally spelt Skryne.- External links :* -See also:*List of towns and villages...

, County Sligo, Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

, where he was born and brought up in an evangelical

Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism is a Protestant Christian movement which began in Great Britain in the 1730s and gained popularity in the United States during the series of Great Awakenings of the 18th and 19th century.Its key commitments are:...

Protestant family. After attending schools in Skreen, Dublin, and Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

, he matriculated in 1837 at Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England.The college has over seven hundred students and fellows, and is the third oldest college of the university. Physically, it is one of the university's larger colleges, with buildings from almost every century since its...

, where four years later, on graduating as senior wrangler and first Smith's prize

Smith's Prize

The Smith's Prize was the name of each of two prizes awarded annually to two research students in theoretical Physics, mathematics and applied mathematics at the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England.- History :...

man, he was elected to a fellowship. In accordance with the college statutes, he had to resign the fellowship when he married in 1857, but twelve years later, under new statutes, he was re-elected. He retained his place on the foundation until 1902, when on the day before his 83rd birthday, he was elected to the mastership. He did not hold this position for long, for he died at Cambridge on 1 February the following year, and was buried in the Mill Road cemetery

Mill Road Cemetery, Cambridge

Mill Road Cemetery is a cemetery off Mill Road in the Petersfield area of Cambridge, England. The cemetery is listed by English Heritage as a Grade II site, and several of the tombs are also listed as of special architectural and historical interest....

.

Career

In 1849, Stokes was appointed to the Lucasian professorship of mathematics at Cambridge, a position he held until his death in 1903. On June 1, 1899, the jubilee of this appointment was celebrated there in a ceremony, which was attended by numerous delegates from European and American universities. A commemorative gold medal was presented to Stokes by the chancellor of the university, and marble busts of Stokes by Hamo ThornycroftHamo Thornycroft

Sir William "Hamo" Thornycroft, RA was a British sculptor, responsible for several London landmarks.-Biography:...

were formally offered to Pembroke College and to the university by Lord Kelvin

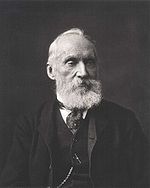

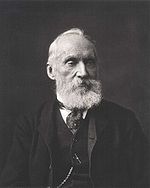

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin OM, GCVO, PC, PRS, PRSE, was a mathematical physicist and engineer. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and did much to unify the emerging...

. Stokes, who was made a baronet in 1889, further served his university by representing it in parliament from 1887 to 1892 as one of the two members for the Cambridge University constituency

Cambridge University (UK Parliament constituency)

Cambridge University was a university constituency electing two members to the British House of Commons, from 1603 to 1950.-Boundaries, Electorate and Election Systems:...

. During a portion of this period (1885–1890) he also was president of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, of which he had been one of the secretaries since 1854. Since he was also Lucasian Professor at this time, Stokes was the first person to hold all three positions simultaneously; Newton held the same three, although not at the same time.

Stokes was the oldest of the trio of natural philosophers, James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell of Glenlair was a Scottish physicist and mathematician. His most prominent achievement was formulating classical electromagnetic theory. This united all previously unrelated observations, experiments and equations of electricity, magnetism and optics into a consistent theory...

and Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin OM, GCVO, PC, PRS, PRSE, was a mathematical physicist and engineer. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and did much to unify the emerging...

being the other two, who especially contributed to the fame of the Cambridge school of mathematical physics in the middle of the 19th century. Stokes's original work began about 1840, and from that date onwards the great extent of his output was only less remarkable than the brilliance of its quality. The Royal Society's catalogue of scientific papers gives the titles of over a hundred memoirs by him published down to 1883. Some of these are only brief notes, others are short controversial or corrective statements, but many are long and elaborate treatises.

Contributions to science

In content his work is distinguished by a certain definiteness and finality, and even of problems which, when he attacked them, were scarcely thought amenable to mathematical analysis, he has in many cases given solutions which once and for all settle the main principles. This fact must be ascribed to his extraordinary combination of mathematical power with experimental skill. From the time when in about 1840 he fitted up some simple physical apparatus in his rooms in Pembroke College, mathematics and experiment ever went hand in hand, aiding and checking each other. In scope his work covered a wide range of physical inquiry, but, as Marie Alfred CornuMarie Alfred Cornu

Marie Alfred Cornu was a French physicist. The French generally refer to him as Alfred Cornu.Cornu was born at Orléans and was educated at the École polytechnique and the École des mines...

remarked in his Rede lecture

Rede Lecture

The Sir Robert Rede's Lecturer is an annual appointment to give a public lecture, the Sir Robert Rede's Lecture at the University of Cambridge. It is named for Sir Robert Rede, who was Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in the sixteenth century.-Initial series:The initial series of lectures ranges...

of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

Fluid dynamics

His first published papers, which appeared in 1842 and 1843, were on the steady motion of incompressible fluidFluid

In physics, a fluid is a substance that continually deforms under an applied shear stress. Fluids are a subset of the phases of matter and include liquids, gases, plasmas and, to some extent, plastic solids....

s and some cases of fluid motion. These were followed in 1845 by one on the friction of fluids in motion and the equilibrium and motion of elastic solids, and in 1850 by another on the effects of the internal friction of fluids on the motion of pendulum

Pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced from its resting equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the equilibrium position...

s. To the theory of sound

Sound

Sound is a mechanical wave that is an oscillation of pressure transmitted through a solid, liquid, or gas, composed of frequencies within the range of hearing and of a level sufficiently strong to be heard, or the sensation stimulated in organs of hearing by such vibrations.-Propagation of...

he made several contributions, including a discussion of the effect of wind

Wind

Wind is the flow of gases on a large scale. On Earth, wind consists of the bulk movement of air. In outer space, solar wind is the movement of gases or charged particles from the sun through space, while planetary wind is the outgassing of light chemical elements from a planet's atmosphere into space...

on the intensity of sound and an explanation of how the intensity is influenced by the nature of the gas in which the sound is produced. These inquiries together put the science of fluid dynamics

Fluid dynamics

In physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics...

on a new footing, and provided a key not only to the explanation of many natural phenomena, such as the suspension of cloud

Cloud

A cloud is a visible mass of liquid droplets or frozen crystals made of water and/or various chemicals suspended in the atmosphere above the surface of a planetary body. They are also known as aerosols. Clouds in Earth's atmosphere are studied in the cloud physics branch of meteorology...

s in air, and the subsidence of ripples and waves in water, but also to the solution of practical problems, such as the flow of water in rivers and channels, and the skin resistance of ships.

Creeping flow

Viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of the resistance of a fluid which is being deformed by either shear or tensile stress. In everyday terms , viscosity is "thickness" or "internal friction". Thus, water is "thin", having a lower viscosity, while honey is "thick", having a higher viscosity...

led to his calculating the terminal velocity for a sphere falling in a viscous medium. This became known as Stokes' law

Stokes' law

In 1851, George Gabriel Stokes derived an expression, now known as Stokes' law, for the frictional force – also called drag force – exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers in a continuous viscous fluid...

. He derived an expression for the frictional force (also called drag force) exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers.

His work is the basis of the falling sphere viscometer

Viscometer

A viscometer is an instrument used to measure the viscosity of a fluid. For liquids with viscosities which vary with flow conditions, an instrument called a rheometer is used...

, in which the fluid is stationary in a vertical glass tube. A sphere of known size and density is allowed to descend through the liquid. If correctly selected, it reaches terminal velocity

Terminal velocity

In fluid dynamics an object is moving at its terminal velocity if its speed is constant due to the restraining force exerted by the fluid through which it is moving....

, which can be measured by the time it takes to pass two marks on the tube. Electronic sensing can be used for opaque fluids. Knowing the terminal velocity, the size and density of the sphere, and the density of the liquid, Stokes' law can be used to calculate the viscosity of the fluid. A series of steel ball bearing

Ball bearing

A ball bearing is a type of rolling-element bearing that uses balls to maintain the separation between the bearing races.The purpose of a ball bearing is to reduce rotational friction and support radial and axial loads. It achieves this by using at least two races to contain the balls and transmit...

s of different diameter is normally used in the classic experiment to improve the accuracy of the calculation. The school experiment uses glycerine as the fluid, and the technique is used industrially to check the viscosity of fluids used in processes.

The same theory explains why small water droplets (or ice crystals) can remain suspended in air (as clouds) until they grow to a critical size and start falling as rain

Rain

Rain is liquid precipitation, as opposed to non-liquid kinds of precipitation such as snow, hail and sleet. Rain requires the presence of a thick layer of the atmosphere to have temperatures above the melting point of water near and above the Earth's surface...

(or snow

Snow

Snow is a form of precipitation within the Earth's atmosphere in the form of crystalline water ice, consisting of a multitude of snowflakes that fall from clouds. Since snow is composed of small ice particles, it is a granular material. It has an open and therefore soft structure, unless packed by...

and hail

Hail

Hail is a form of solid precipitation. It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is referred to as a hail stone. Hail stones on Earth consist mostly of water ice and measure between and in diameter, with the larger stones coming from severe thunderstorms...

). Similar use of the equation can be made in the settlement of fine particles in water or other fluids.

The CGS unit of kinematic viscosity was named "stokes" in recognition of his work.

Light

Perhaps his best-known researches are those which deal with the wave theory of lightLight

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that is visible to the human eye, and is responsible for the sense of sight. Visible light has wavelength in a range from about 380 nanometres to about 740 nm, with a frequency range of about 405 THz to 790 THz...

. His optical

Optics

Optics is the branch of physics which involves the behavior and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behavior of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light...

work began at an early period in his scientific career. His first papers on the aberration of light

Aberration of light

The aberration of light is an astronomical phenomenon which produces an apparent motion of celestial objects about their real locations...

appeared in 1845 and 1846, and were followed in 1848 by one on the theory of certain bands seen in the spectrum

Electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all possible frequencies of electromagnetic radiation. The "electromagnetic spectrum" of an object is the characteristic distribution of electromagnetic radiation emitted or absorbed by that particular object....

.

In 1849 he published a long paper on the dynamical theory of diffraction

Diffraction

Diffraction refers to various phenomena which occur when a wave encounters an obstacle. Italian scientist Francesco Maria Grimaldi coined the word "diffraction" and was the first to record accurate observations of the phenomenon in 1665...

, in which he showed that the plane of polarization must be perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Two years later he discussed the colours of thick plates.

Fluorescence

Wavelength

In physics, the wavelength of a sinusoidal wave is the spatial period of the wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.It is usually determined by considering the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase, such as crests, troughs, or zero crossings, and is a...

of light, he described the phenomenon of fluorescence

Fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation of a different wavelength. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore lower energy, than the absorbed radiation...

, as exhibited by fluorspar and uranium glass

Uranium glass

Uranium glass is glass which has had uranium, usually in oxide diuranate form, added to a glass mix before melting. The proportion usually varies from trace levels to about 2% by weight uranium, although some 19th-century pieces were made with up to 25% uranium.Uranium glass was once made into...

, materials which he viewed as having the power to convert invisible ultra-violet radiation into radiation of longer wavelengths that are visible. The Stokes shift

Stokes shift

Stokes shift is the difference between positions of the band maxima of the absorption and emission spectra of the same electronic transition. It is named after Irish physicist George G. Stokes. When a system absorbs a photon, it gains energy and enters an excited state...

, which describes this conversion, is named in Stokes' honor. A mechanical model, illustrating the dynamical principle of Stokes's explanation was shown. The offshoot of this, Stokes line

Stokes line

In complex analysis a Stokes line, named after Sir George Gabriel Stokes, is a line in the complex plane which 'turns on' different kinds of behaviour when one 'passes over' this line – although, somewhat confusingly, this definition is sometimes used for anti-Stokes lines...

, is the basis of Raman scattering

Raman scattering

Raman scattering or the Raman effect is the inelastic scattering of a photon. It was discovered by Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman and Kariamanickam Srinivasa Krishnan in liquids, and by Grigory Landsberg and Leonid Mandelstam in crystals....

. In 1883, during a lecture at the Royal Institution

Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain is an organization devoted to scientific education and research, based in London.-Overview:...

, Lord Kelvin said he had heard an account of it from Stokes many years before, and had repeatedly but vainly begged him to publish it.

Polarization

Reflection (physics)

Reflection is the change in direction of a wavefront at an interface between two differentmedia so that the wavefront returns into the medium from which it originated. Common examples include the reflection of light, sound and water waves...

exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarization. About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862 he prepared for the British Association

British Association for the Advancement of Science

frame|right|"The BA" logoThe British Association for the Advancement of Science or the British Science Association, formerly known as the BA, is a learned society with the object of promoting science, directing general attention to scientific matters, and facilitating interaction between...

a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar

Iceland spar

Iceland spar, formerly known as Iceland crystal, is a transparent variety of calcite, or crystallized calcium carbonate, originally brought from Iceland, and used in demonstrating the polarization of light . It occurs in large readily cleavable crystals, easily divisible into rhombs, and is...

, transparent calcite

Calcite

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate . The other polymorphs are the minerals aragonite and vaterite. Aragonite will change to calcite at 380-470°C, and vaterite is even less stable.-Properties:...

crystals.

A paper on the long spectrum of the electric light bears the same date, and was followed by an inquiry into the absorption spectrum of blood

Blood

Blood is a specialized bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells....

.

Chemical analysis

The chemical identification of organicOrganic compound

An organic compound is any member of a large class of gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical compounds whose molecules contain carbon. For historical reasons discussed below, a few types of carbon-containing compounds such as carbides, carbonates, simple oxides of carbon, and cyanides, as well as the...

bodies by their optical properties was treated in 1864; and later, in conjunction with the Rev. William Vernon Harcourt

William Vernon Harcourt (scientist)

William Vernon Harcourt was founder of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.-Family:He was born at Sudbury, Derbyshire, a younger son of Edward Vernon-Harcourt, Archbishop of York and his wife Lady Anne Leveson-Gower, who was a daughter of Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Marquess of...

, he investigated the relation between the chemical composition and the optical properties of various glass

Glass

Glass is an amorphous solid material. Glasses are typically brittle and optically transparent.The most familiar type of glass, used for centuries in windows and drinking vessels, is soda-lime glass, composed of about 75% silica plus Na2O, CaO, and several minor additives...

es, with reference to the conditions of transparency and the improvement of achromatic

Achromatic lens

An achromatic lens or achromat is a lens that is designed to limit the effects of chromatic and spherical aberration. Achromatic lenses are corrected to bring two wavelengths into focus in the same plane....

telescope

Telescope

A telescope is an instrument that aids in the observation of remote objects by collecting electromagnetic radiation . The first known practical telescopes were invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 1600s , using glass lenses...

s. A still later paper connected with the construction of optical instruments discussed the theoretical limits to the aperture of microscope objectives.

Other work

Thermal conductivity

In physics, thermal conductivity, k, is the property of a material's ability to conduct heat. It appears primarily in Fourier's Law for heat conduction....

in crystal

Crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions. The scientific study of crystals and crystal formation is known as crystallography...

s (1851) and his inquiries in connection with Crookes radiometer

Crookes radiometer

The Crookes radiometer, also known as the light mill, consists of an airtight glass bulb, containing a partial vacuum. Inside are a set of vanes which are mounted on a spindle. The vanes rotate when exposed to light, with faster rotation for more intense light, providing a quantitative measurement...

; his explanation of the light border frequently noticed in photograph

Photograph

A photograph is an image created by light falling on a light-sensitive surface, usually photographic film or an electronic imager such as a CCD or a CMOS chip. Most photographs are created using a camera, which uses a lens to focus the scene's visible wavelengths of light into a reproduction of...

s just outside the outline of a dark body seen against the sky (1883); and, still later, his theory of the x-ray

X-ray

X-radiation is a form of electromagnetic radiation. X-rays have a wavelength in the range of 0.01 to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30 petahertz to 30 exahertz and energies in the range 120 eV to 120 keV. They are shorter in wavelength than UV rays and longer than gamma...

s, which he suggested might be transverse waves travelling as innumerable solitary waves, not in regular trains. Two long papers published in 1840—one on attractions and Clairaut's theorem

Clairaut's theorem

Clairaut's theorem, published in 1743 by Alexis Claude Clairaut in his Théorie de la figure de la terre, tirée des principes de l'hydrostatique, synthesized physical and geodetic evidence that the Earth is an oblate rotational ellipsoid. It is a general mathematical law applying to spheroids of...

, and the other on the variation of gravity at the surface of the earth—also demand notice, as do his mathematical memoirs on the critical values of sums of periodic series (1847) and on the numerical calculation of a class of definite integral

Integral

Integration is an important concept in mathematics and, together with its inverse, differentiation, is one of the two main operations in calculus...

s and infinite series (1850) and his discussion of a differential equation

Differential equation

A differential equation is a mathematical equation for an unknown function of one or several variables that relates the values of the function itself and its derivatives of various orders...

relating to the breaking of railway bridge

Bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span physical obstacles such as a body of water, valley, or road, for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle...

s (1849), research related to his evidence given to the Royal Commission on the Use of Iron in Railway structures after the Dee bridge disaster

Dee bridge disaster

The Dee bridge disaster was a rail accident that occurred on 24 May 1847 in Chester with five fatalities.A new bridge across the River Dee was needed for the Chester and Holyhead Railway, a project planned in the 1840s for the expanding British railway system. It was built using cast iron girders,...

of 1847.

Unpublished research

But large as is the tale of Stokes's published work, it by no means represents the whole of his services in the advancement of science. Many of his discoveries were not published, or at least were only touched upon in the course of his oral lectures. An excellent example is his work in the theory of spectroscopySpectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the study of the interaction between matter and radiated energy. Historically, spectroscopy originated through the study of visible light dispersed according to its wavelength, e.g., by a prism. Later the concept was expanded greatly to comprise any interaction with radiative...

.

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

.

Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the study of the interaction between matter and radiated energy. Historically, spectroscopy originated through the study of visible light dispersed according to its wavelength, e.g., by a prism. Later the concept was expanded greatly to comprise any interaction with radiative...

.

In another way, too, Stokes did much for the progress of mathematical physics. Soon after he was elected to the Lucasian chair he announced that he regarded it as part of his professional duties to help any member of the university in difficulties he might encounter in his mathematical studies, and the assistance rendered was so real that pupils were glad to consult him, even after they had become colleagues, on mathematical and physical problems in which they found themselves at a loss. Then during the thirty years he acted as secretary of the Royal Society he exercised an enormous if inconspicuous influence on the advancement of mathematical and physical science, not only directly by his own investigations, but indirectly by suggesting problems for inquiry and inciting men to attack them, and by his readiness to give encouragement and help.

Contributions to engineering

Dee bridge disaster

The Dee bridge disaster was a rail accident that occurred on 24 May 1847 in Chester with five fatalities.A new bridge across the River Dee was needed for the Chester and Holyhead Railway, a project planned in the 1840s for the expanding British railway system. It was built using cast iron girders,...

in May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of passing trains. Cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

is brittle

Brittle

A material is brittle if, when subjected to stress, it breaks without significant deformation . Brittle materials absorb relatively little energy prior to fracture, even those of high strength. Breaking is often accompanied by a snapping sound. Brittle materials include most ceramics and glasses ...

in tension or bending

Bending

In engineering mechanics, bending characterizes the behavior of a slender structural element subjected to an external load applied perpendicularly to a longitudinal axis of the element. The structural element is assumed to be such that at least one of its dimensions is a small fraction, typically...

, and many other similar bridges had to be demolished or reinforced.

Tay Bridge disaster

The Tay Bridge disaster occurred on 28 December 1879, when the first Tay Rail Bridge, which crossed the Firth of Tay between Dundee and Wormit in Scotland, collapsed during a violent storm while a train was passing over it. The bridge was designed by the noted railway engineer Sir Thomas Bouch,...

, where he gave evidence about the effects of wind loads on the bridge. The centre section of the bridge (known as the High Girders) was completely destroyed during a storm on December 28, 1879, while an express train was in the section, and everyone aboard died (more than 75 victims). The Board of Inquiry listened to many expert witness

Expert witness

An expert witness, professional witness or judicial expert is a witness, who by virtue of education, training, skill, or experience, is believed to have expertise and specialised knowledge in a particular subject beyond that of the average person, sufficient that others may officially and legally...

es, and concluded that the bridge was "badly designed, badly built and badly maintained".

As a result of his evidence, he was appointed a member of the subsequent Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

into the effect of wind pressure on structures. The effects of high winds on large structures had been neglected at that time, and the commission conducted a series of measurements across Britain

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

to gain an appreciation of wind speeds during storms, and the pressures they exerted on exposed surfaces.

Contributions to Christianity

Stokes held conservative religious values and beliefs. In 1886, Stokes became president of the Victoria InstituteVictoria Institute

The Victoria Institute, or Philosophical Society of Great Britain, was founded in 1865, as a response to the publication of On the Origin of Species and Essays and Reviews. Its stated objective was to defend "the great truths revealed in Holy Scripture .....

, a Christian institute founded in response to the evolutionary movement of the 1860s. He gave the 1891 Gifford lectures

Gifford Lectures

The Gifford Lectures were established by the will of Adam Lord Gifford . They were established to "promote and diffuse the study of Natural Theology in the widest sense of the term — in other words, the knowledge of God." The term natural theology as used by Gifford means theology supported...

. He was also the vice president of the British and Foreign Bible Society and was active in foreign missions doctrinal issues.

Legacy and honours

- Stokes' lawStokes' lawIn 1851, George Gabriel Stokes derived an expression, now known as Stokes' law, for the frictional force – also called drag force – exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers in a continuous viscous fluid...

, in fluid dynamicsFluid dynamicsIn physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics... - Stokes radiusStokes radiusThe Stokes radius, Stokes-Einstein radius, or hydrodynamic radius RH, named after George Gabriel Stokes, is not the effective radius of a hydrated molecule in solution as often mentioned. Rather it is the radius of a hard sphere that diffuses at the same rate as the molecule. The behavior of this...

in biochemistryBiochemistryBiochemistry, sometimes called biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes in living organisms, including, but not limited to, living matter. Biochemistry governs all living organisms and living processes... - Stokes' theoremStokes' theoremIn differential geometry, Stokes' theorem is a statement about the integration of differential forms on manifolds, which both simplifies and generalizes several theorems from vector calculus. Lord Kelvin first discovered the result and communicated it to George Stokes in July 1850...

, in differential geometry - Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University

- Stokes lineStokes lineIn complex analysis a Stokes line, named after Sir George Gabriel Stokes, is a line in the complex plane which 'turns on' different kinds of behaviour when one 'passes over' this line – although, somewhat confusingly, this definition is sometimes used for anti-Stokes lines...

, in Raman scatteringRaman scatteringRaman scattering or the Raman effect is the inelastic scattering of a photon. It was discovered by Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman and Kariamanickam Srinivasa Krishnan in liquids, and by Grigory Landsberg and Leonid Mandelstam in crystals.... - Stokes relationsStokes relationsStokes relations describe the relative phase of light reflected at a boundary between materials of different refractive index. They also relate the transmission and reflection coefficients for the interaction...

, relating the phase of light reflected from a non-absorbing boundary - Stokes shiftStokes shiftStokes shift is the difference between positions of the band maxima of the absorption and emission spectra of the same electronic transition. It is named after Irish physicist George G. Stokes. When a system absorbs a photon, it gains energy and enters an excited state...

, in fluorescenceFluorescenceFluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation of a different wavelength. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore lower energy, than the absorbed radiation... - Navier–Stokes equations, in fluid dynamicsFluid dynamicsIn physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics...

- Stokes driftStokes driftFor a pure wave motion in fluid dynamics, the Stokes drift velocity is the average velocity when following a specific fluid parcel as it travels with the fluid flow...

, in fluid dynamicsFluid dynamicsIn physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics... - Stokes stream functionStokes stream functionIn fluid dynamics, the Stokes stream function is used to describe the streamlines and flow velocity in a three-dimensional incompressible flow with axisymmetry. A surface with a constant value of the Stokes stream function encloses a streamtube, everywhere tangential to the flow velocity vectors...

, in fluid dynamicsFluid dynamicsIn physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics... - Stokes boundary layerStokes boundary layerIn fluid dynamics, the Stokes boundary layer, or oscillatory boundary layer, refers to the boundary layer close to a solid wall in oscillatory flow of a viscous fluid...

, in fluid dynamicsFluid dynamicsIn physics, fluid dynamics is a sub-discipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow—the natural science of fluids in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics... - Stokes phenomenon in asymptotic analysis

- Stokes (unit), a unit of viscosityViscosityViscosity is a measure of the resistance of a fluid which is being deformed by either shear or tensile stress. In everyday terms , viscosity is "thickness" or "internal friction". Thus, water is "thin", having a lower viscosity, while honey is "thick", having a higher viscosity...

- Stokes parametersStokes parametersThe Stokes parameters are a set of values that describe the polarization state of electromagnetic radiation. They were defined by George Gabriel Stokes in 1852, as a mathematically convenient alternative to the more common description of incoherent or partially polarized radiation in terms of its...

and Stokes vector, used to quantify the polarization of electromagnetic waves - Campbell–Stokes recorder, an instrument for recording sunshine that was improved by Stokes, and still widely used today

- Stokes (lunar crater)Stokes (lunar crater)Stokes is a lunar crater that is nestled in the curve formed by the craters Regnault to the north, Volta along the northeast, and Langley. This formation of craters lies nearly along the northwestern limb of the Moon, where their visibility is affected by libration effects.The rim of this crater...

- Stokes (Martian crater)Stokes (Martian crater)Stokes is an impact crater on Mars. It is located on the Martian Northern plains. It is distinctive for its dark-toned sand dunes, which have been formed by the planet's strong winds.It was named after George Gabriel Stokes....

- From the Royal SocietyRoyal SocietyThe Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, of which he became a fellow in 1851, he received the Rumford MedalRumford MedalThe Rumford Medal is awarded by the Royal Society every alternating year for "an outstandingly important recent discovery in the field of thermal or optical properties of matter made by a scientist working in Europe". First awarded in 1800, it was created after a 1796 donation of $5000 by the...

in 1852 in recognition of his inquiries into the wavelength of light, and later, in 1893, the Copley MedalCopley MedalThe Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society of London for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science, and alternates between the physical sciences and the biological sciences"...

. - In 1869 he presided over the Exeter meeting of the British Association.

- From 1883 to 1885 he was Burnett lecturer at Aberdeen, his lectures on light, which were published in 1884–1887, dealing with its nature, its use as a means of investigation, and its beneficial effects.

- In 1889 he was made a baronetBaronetA baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

. - In 1891, as GiffordGifford LecturesThe Gifford Lectures were established by the will of Adam Lord Gifford . They were established to "promote and diffuse the study of Natural Theology in the widest sense of the term — in other words, the knowledge of God." The term natural theology as used by Gifford means theology supported...

lecturer, he published a volume on Natural Theology. - His academic distinctions included honorary degrees from many universities, together with membership of the PrussiaPrussiaPrussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n Order Pour le Mérite.

Publications

Stokes's mathematical and physical papers (see external links) were published in a collected form in five volumes; the first three (Cambridge, 1880, 1883, and 1901) under his own editorship, and the two last (Cambridge, 1904 and 1905) under that of Sir Joseph LarmorJoseph Larmor

Sir Joseph Larmor , a physicist and mathematician who made innovations in the understanding of electricity, dynamics, thermodynamics, and the electron theory of matter...

, who also selected and arranged the Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of Stokes published at Cambridge in 1907.

Further reading

- Wilson, David B., Kelvin and Stokes A Comparative Study in Victorian Physics, (1987) ISBN 0-85274-526-5

- Peter R Lewis, Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879, Tempus (2004). ISBN 0-75243-160-9

- PR Lewis and C Gagg, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 45, 29, (2004).

- PR Lewis, Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847, Tempus Publishing (2007) ISBN 978 0 7524 4266 2

External links

- Biography on Dublin City University Web site (1907), ed. by J. Larmor

- Mathematical and physical papers volume 1 and volume 2 from the Internet ArchiveInternet ArchiveThe Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...

- Mathematical and physical papers, volumes 1 to 5 from the University of Michigan Digital Collection.

- Life and work of Stokes

- Natural Theology (1891), Adam and Charles Black. (1891–93 Gifford LecturesGifford LecturesThe Gifford Lectures were established by the will of Adam Lord Gifford . They were established to "promote and diffuse the study of Natural Theology in the widest sense of the term — in other words, the knowledge of God." The term natural theology as used by Gifford means theology supported...

) - works by George Gabriel Stokes at the Internet ArchiveInternet ArchiveThe Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...