Morea expedition

Encyclopedia

The Morea expedition is the name given in France to the land intervention of the French Army in the Peloponnese

, between 1828 and 1833, at the time of the Greek War of Independence

.

After the fall of Messolonghi, Western Europe decided to intervene in favour of revolutionary Greece. Their attitude toward the Ottoman Empire

's Egypt

ian ally, Ibrahim Pasha

, was especially critical; their primary objective was to elicit the evacuation of the occupied regions, the Peloponnese in particular. The intervention began when a Franco

-Russo

-British

fleet was sent to the region, winning the Battle of Navarino

in October 1827. In August 1828, a French expeditionary corps disembarked at Koroni

in the southern Peloponnese. The soldiers were stationed on the peninsula until the evacuation of Egyptian troops in October, then taking control of the principal strongholds still held by Turkish troops. Although the bulk of the troops returned to France from the end of 1828, there was a French presence in the area up until 1833.

As during Napoleon's

Egyptian Campaign

, when a Commission of Sciences and Arts

had accompanied the military campaign, a Morea scientific mission (Mission scientifique de Morée) accompanied the troops. Seventeen learned men represented different specialties (natural history and antiquities – archaeology, architecture and sculpture) made the voyage. Their work was of major importance in increasing knowledge about the country. As an example, the topographic maps they produced were excellent. More significantly, the measurements, drawings, profiles, plans and proposals for the theoretical restoration of Peloponnesian monuments, of Attica

and of the Cyclades

were, following James Stuart

and Nicholas Revett

's Antiquities of Athens, a new attempt to systematically and exhaustively catalogue ancient Greek ruins. The Morea expedition and its publications offered a near-complete description of the regions visited. They formed a scientific, aesthetic and human inventory that remained one of the best means, short of visiting them in person, to get to know the regions.

. They won numerous victories early on and declared independence. However, the declaration contradicted the principles of the Congress of Vienna

and of the Holy Alliance

, which imposed a European equilibrium of the status quo, outlawing any change. In contrast to what happened elsewhere in Europe, the Holy Alliance did not intervene to stop the liberal Greek insurgents.

The liberal and national uprising displeased the Austria

of Metternich's

, the principal political architect of the Holy Alliance. However, Russia, another reactionary gendarme of Europe, was favourable to the insurrection due to its Orthodox

religious solidarity and its geostrategic interest (control of the Dardanelles

and the Bosphorus). France, another active member of the Holy Alliance which had just intervened in Spain against liberals at Trocadero

, had an ambiguous position: the liberal Greeks were first and foremost Christians, and their uprising against the Muslim Ottomans had undertones of a new crusade. Great Britain, a liberal country, was interested in the regional situation primarily because it lay on the route to India

and London wished to exercise a form of control there. For all of Europe, Greece represented the cradle of civilisation and of art since antiquity.

The Greek victories had been short-lived. The Sultan had called to his aid his Egyptian vassal Muhammad Ali

The Greek victories had been short-lived. The Sultan had called to his aid his Egyptian vassal Muhammad Ali

, who had dispatched his son Ibrahim Pasha

to Greece with a fleet and 8,000 men, later adding 25,000. Ibrahim’s intervention was decisive: the Peloponnese had been reconquered in 1825; the gateway town of Messolonghi had fallen in 1826; Athens had been taken in 1827. All that Greek nationalists still held was Nafplion

, Hydra

, Mani

and Aegina

.

A strong current of philhellenism

developed in Western Europe. Thus it was decided to intervene in favour of Greece, the cradle of civilisation and a Christian vanguard in the Orient whose strategic location was clear. By the Treaty of London of July 1827, France, Russia and the United Kingdom recognised the autonomy of Greece, which remained a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The three powers agreed to a limited intervention in order to convince the Porte to accept the terms of the convention. A plan to send a naval expedition as a show of force was proposed and adopted. A joint Russian, French and British fleet was sent to exercise diplomatic pressure against Constantinople. The Battle of Navarino

, fought after a chance encounter, resulted in the destruction of the Turkish-Egyptian fleet.

In 1828, Ibrahim Pasha thus found himself in a difficult situation: he had just suffered a defeat at Navarino; the joint fleet exercised a blockade which prevented him from receiving reinforcements and supplies; his Albanian troops, whom he could no longer pay, had returned to their country under the protection of Theodoros Kolokotronis’ Greek troops. On August 6, 1828, a convention had been signed at Alexandria

between the viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and the British admiral Edward Codrington

. Ibrahim Pasha had to evacuate his Egyptian troops and leave the Peloponnese to the few Turkish troops (estimated at 1200 men) remaining there. However, Ibrahim Pasha refused to honor the agreement that had been reached, continuing to control various Greek regions: Messenia

, Navarino

, Patras

and several other strongholds. He had also ordered the systematic destruction of Tripoli

.

In addition, the French government of Charles X

was beginning to have doubts about its Greek policy. Ibrahim Pasha himself noted this ambiguity when he met General Maison

in September: “Why was France, after enslaving men in Spain in 1823, now coming to Greece to make men free?” At last, a liberal agitation, pro-Greek and inspired by what was then happening in that country, began to develop in France. The longer France waited, the more delicate her position vis-à-vis Metternich became. The ultra-royalist government thus decided to accelerate events. A land expedition was proposed to Great Britain, which refused to intervene directly. Meanwhile, Russia had declared war against the Ottoman Empire and its military victories were unsettling for London, which did not wish to see the Tsarist empire extend too far south. Great Britain was thus not opposed to an intervention by France alone.

philosophy had developed Western Europeans’ interest in Greece, or rather in an idealised Ancient Greece

, the linchpin of Antiquity

, as it was perceived and taught. The Enlightenment philosophers, for whom the notions of Nature and Reason were so important, believed that these had been the fundamental values of Classical Athens. The Ancient Greek democracies, and above all Athens

, became models to emulate. There they searched for answers to the political and philosophical problems of their time. Works such as those of Abbé Barthélemy

, Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis

(1788), served to fix definitively the image that Europe had of the Aegean

.

The theories and system of interpreting ancient art devised by Johann Joachim Winckelmann

influenced European tastes for decades. His major work, History of Ancient Art, was published in 1764 and translated into French in 1766 (the English translation came later, in 1881). In this major work Winckelmann initiated the tradition of dividing ancient art into periods, classifying the works chronologically and stylistically.

The views of Winckelmann on art encompassed the entirety of civilisation. He drew a parallel between a civilisation's general level of development and the evolution of its art. He interpreted this artistic evolution the same way that his contemporaries saw the life cycle of a civilisation, in terms of progress, apogee and then decline. For him, Greek art had been the pinnacle of artistic achievement, culminating with Phidias

. Further, Winckelmann believed that the most beautiful works of Greek art had been produced under ideal geographic, political and religious circumstances. This frame of thought long dominated intellectual life in Europe. He classified Greek art into four periods: Ancient (archaic period), Sublime (Phidias), Beautiful (Praxiteles

) and Decadent (Roman period).

Winckelmann’s theories on the evolution of art culminated in the Sublime period of Greek art, which had been conceived during a period of complete political and religious liberty. The theories idealised Ancient Greece and increased people’s desire to travel to contemporary Greece. It was seductive to believe, as he did, that 'good taste' was born beneath the Greek sky. He convinced 18th-century Europe that life in Ancient Greece was pure, simple and moral, and that classical Hellas was the source from which artists should draw ideas of “noble simplicity and calm grandeur”. Greece became the “motherland of the arts” and “the teacher of taste”.

Winckelmann’s theories on the evolution of art culminated in the Sublime period of Greek art, which had been conceived during a period of complete political and religious liberty. The theories idealised Ancient Greece and increased people’s desire to travel to contemporary Greece. It was seductive to believe, as he did, that 'good taste' was born beneath the Greek sky. He convinced 18th-century Europe that life in Ancient Greece was pure, simple and moral, and that classical Hellas was the source from which artists should draw ideas of “noble simplicity and calm grandeur”. Greece became the “motherland of the arts” and “the teacher of taste”.

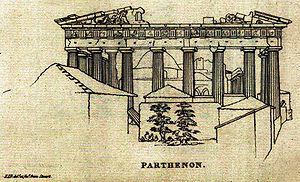

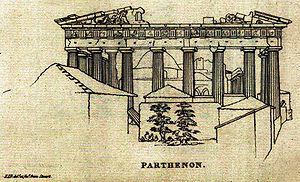

The French government had planned the Morea expedition in the same spirit as those of James Stuart

and Nicholas Revett

, whose work it wished to complete. The semi-scientific expeditions commissioned and financed by the Society of Dilettanti remained a benchmark: these represented the first attempts to rediscover Ancient Greece. The first, that of Stuart and Revett to Athens and the islands, took place in 1751–1753, and resulted in The Antiquities of Athens, mined by architects and designers for a refined "Grecian" neoclassicism

. The expedition of Revett, Richard Chandler

and William Pars to Asia Minor took place between 1764 and 1766. Finally, the “work

” of Lord Elgin

on the Parthenon

at the beginning of the 19th century had sparked further longing for Greece: it now seemed possible to build vast collections of ancient art in Western Europe.

to allow the government to meet its obligations. An expeditionary corps of 13,000–15,000 men commanded by Lieutenant-General Nicolas Joseph Maison

was formed. It was composed of three brigades commanded by Field Marshals Tiburce Sébastiani, Philippe Higonet and Virgile Schneider. The Chief of the General Staff was General Antoine Simon Durrieu.

The expeditionary corps was made up of nine infantry regiments:

Also departing were the 3rd horse chasseurs regiment (commanded by Colonel Paul-Eugène de Faudoas-Barbazan), four companies of artillery (with equipment for campaigns, sieges, and mountains) of the 3rd and 8th artillery regiments, and two companies of military engineers (sappers and miners).

A transport fleet protected by warships was organised; sixty ships sailed in all. Equipment, victuals, munitions and 1,300 horses had to be brought over, as well as arms, munitions and money for the Greek provisional government of John Capodistria. France wished to support free Greece as it came into being by helping it activate its army. The goal was of course to maintain influence in the region.

The first brigade left Toulon

on August 17; the second, two days later; and the third on September 1. The general in command, Nicolas Joseph Maison

, was with the first brigade, aboard the ship of the line

Ville de Marseille. The first convoy was composed of merchant ships and apart from the Ville de Marseille, it included the frigates Amphitrite, Bellone and Cybèle. The second convoy was escorted by ship of the line Duquesne and the frigates Iphigénie and Armide.

On August 29, the fleet transporting the two first brigades arrived in Navarino bay, where the joint Franco-Russo-British squadron was berthed. The Egyptian army was concentrated between Navarino and Methoni

On August 29, the fleet transporting the two first brigades arrived in Navarino bay, where the joint Franco-Russo-British squadron was berthed. The Egyptian army was concentrated between Navarino and Methoni

. Thus, the landing was risky. The fleet sailed toward the Gulf of Koroni

protected by a fortress held by the Ottomans. The expeditionary corps began to disembark without meeting any opposition on the evening of August 29, finishing on the morning of August 30. A proclamation by governor Capodistria had informed the Greek population of the imminent arrival of a French expedition. The locals rushed up before the troops as soon as they set foot on Greek soil and offered them food.

The French pitched camp in the plain of Koroni, near Petalidi, on the site of the ancient Coronea. The third brigade, which had borne up against a storm and lost three ships, managed to land at Koroni on September 16.

Ibrahim Pasha used a number of pretexts to delay the evacuation: problems with food supply or transport, or unforeseen difficulties in the strongholds’ handover. The French officers had difficulties in maintaining the fighting zeal of their soldiers, who for example had become excited at the (false) news that an imminent march on Athens would take place. This impatience on the part of the French troops was perhaps decisive in convincing the Egyptian commander to respect his obligations. Moreover, French soldiers were beginning to suffer from autumn rains which drenched their tent camp, increasing the likelihood of fever and especially of dysentery

Ibrahim Pasha used a number of pretexts to delay the evacuation: problems with food supply or transport, or unforeseen difficulties in the strongholds’ handover. The French officers had difficulties in maintaining the fighting zeal of their soldiers, who for example had become excited at the (false) news that an imminent march on Athens would take place. This impatience on the part of the French troops was perhaps decisive in convincing the Egyptian commander to respect his obligations. Moreover, French soldiers were beginning to suffer from autumn rains which drenched their tent camp, increasing the likelihood of fever and especially of dysentery

. On September 24, Louis-Eugène Cavaignac wrote that thirty men of 400 in his company of military engineers were affected by fever. General Maison wished to be able to set up his men in the fortresses’ barracks. On September 7, Ibrahim Pasha accepted to evacuate his troops as of September 9. The agreement reached with General Maison provided that the Egyptians would leave with their arms, baggage and horses, but without any Greek slave or prisoner. As the Egyptian fleet could not evacuate the entire army in one go, supplies were authorised for the troops who remained on land; these men had just undergone a lengthy blockade. A first Egyptian division, 5,500 men and 27 ships, set sail on September 16, escorted by three ships from the joint fleet (two English ones and the French frigate

Sirène).

The last Egyptian transport sailed away on October 5, taking Ibrahim Pasha. Of the 40,000 men he had brought from Egypt, he was taking back barely 20,000. A few Ottoman soldiers remained in order to hold the different strongholds of the Peloponnese. The next mission of the French troops was to “give security” to these and hand them back to independent Greece.

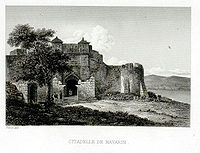

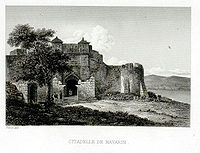

On October 6, General Maison ordered General Higonet to march on Navarino. He left with the 16th infantry regiment, which included artillery and military engineers. Thus, Navarino’s seacoast was put under siege by Admiral Henri de Rigny

On October 6, General Maison ordered General Higonet to march on Navarino. He left with the 16th infantry regiment, which included artillery and military engineers. Thus, Navarino’s seacoast was put under siege by Admiral Henri de Rigny

’s fleet and the land siege was undertaken by General Higonet’s soldiers. The Turkish commander of the fort refused to surrender:

Hence, the sappers received an order to open a breach in the walls. General Higonet entered the fortress, held by 250 men who surrendered with sixty cannons and 800,000 rounds of ammunition. The French troops moved in intending to remain for some time, building up Navarino’s fortifications, rebuilding its houses and setting up a hospital and various features of local administration.

On October 7, the 35th line infantry regiment, commanded by General Durrieu, accompanied by artillery and by military engineers, appeared before Methoni, defended by 1,078 men and a hundred cannons, and which had food supplies for six months. Two ships of the line, the Breslaw (Captain Maillard) and the Wellesley (Captain Maitland) blocked the port and threatened the fortress with their cannons. The fort’s commanders, the Turk Hassan Pasha and the Egyptian Ahmed Bey, made the same type of reply as had the commander of Navarino. Methoni’s fortifications were in a better state than those of Navarino. Thus the sappers focused on opening the city gate. The city’s garrison did not defend it. The commanders of the fort explained that they could not surrender it without disobeying the Sultan’s orders, but also recognised that it was impossible for them to resist. Thus the fort had to be taken, and least symbolically, by force.

On October 7, the 35th line infantry regiment, commanded by General Durrieu, accompanied by artillery and by military engineers, appeared before Methoni, defended by 1,078 men and a hundred cannons, and which had food supplies for six months. Two ships of the line, the Breslaw (Captain Maillard) and the Wellesley (Captain Maitland) blocked the port and threatened the fortress with their cannons. The fort’s commanders, the Turk Hassan Pasha and the Egyptian Ahmed Bey, made the same type of reply as had the commander of Navarino. Methoni’s fortifications were in a better state than those of Navarino. Thus the sappers focused on opening the city gate. The city’s garrison did not defend it. The commanders of the fort explained that they could not surrender it without disobeying the Sultan’s orders, but also recognised that it was impossible for them to resist. Thus the fort had to be taken, and least symbolically, by force.

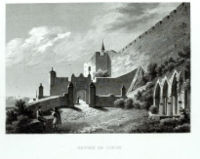

It was more difficult to take Koroni. General Sébastiani showed up there on October 7 with a party from his brigade. The fort commander’s response was similar to those given at Navarino and Methoni. Sébastiani sent his sappers, who were pushed back by rocks thrown from atop the walls. A dozen men were wounded, among them Cavaignac and, more seriously, a captain, a sergeant and three sappers. The other French soldiers felt insulted and their general had great difficulty in preventing them from opening fire and taking the stronghold by force. The Amphitrite, the Breslaw and the Wellesley came to the assistance of the ground troops. The threat they posed led the Ottoman commander to surrender. On October 9, the French entered Koroni and seized 80 cannons and guns, along with numerous victuals and munitions.

It was more difficult to take Koroni. General Sébastiani showed up there on October 7 with a party from his brigade. The fort commander’s response was similar to those given at Navarino and Methoni. Sébastiani sent his sappers, who were pushed back by rocks thrown from atop the walls. A dozen men were wounded, among them Cavaignac and, more seriously, a captain, a sergeant and three sappers. The other French soldiers felt insulted and their general had great difficulty in preventing them from opening fire and taking the stronghold by force. The Amphitrite, the Breslaw and the Wellesley came to the assistance of the ground troops. The threat they posed led the Ottoman commander to surrender. On October 9, the French entered Koroni and seized 80 cannons and guns, along with numerous victuals and munitions.

Patras

had been controlled by Ibrahim Pasha since the evacuation of the Peloponnese. The third brigade had been sent by sea to take the city, located in the north-western part of the peninsula. It landed on October 4. General Schneider gave Hajji Abdullah, Pasha of Patras and of the “Morea Castle”, twenty-four hours to hand over the fort. On October 5, when the ultimatum expired, three columns marched on the city and the artillery was deployed. The Pasha immediately signed the capitulation of Patras and of the “Morea Castle”. However, the aghas who commanded the latter refused to obey their pasha, whom they considered a traitor, and announced that they would rather die in the ruins of their fortress than surrender.

, near Rion

. Bayezid II

had built it in 1499.

General Schneider negotiated with the aghas, who persisted in their refusal to surrender. A siege was begun from in front of the fortress and fourteen marine and field guns, placed a little over 400 meters away, reduced the artillery of those under siege to silence. Admiral de Rigny had General Maison put all his artillery and sappers on board. By land Maison sent two infantry regiments and the 3rd light cavalry regiment. Reinforcements arrived on October 23. New batteries nicknamed “for breaching” (de brèche) were installed. These received the names of Charles X

, George IV

, duc d’Angoulême

, duc de Bordeaux

and “Marine”. A party from the British fleet and the French frigate Blonde came to add their cannons.

On October 30, the batteries opened fire. In four hours, a breach was largely opened in the ramparts. Then, an emissary came out with a white flag to negotiate the terms of the fort’s surrender. General Maison replied that the terms had been negotiated at the beginning of the month at Patras. He added that he did not trust a group of besieged men who had not respected a first agreement to respect a second one. He gave the garrison half an hour to evacuate the fort, without arms or baggage. The aghas submitted. However, the fortress’ resistance had cost 25 men, killed or wounded in the French expedition.

.

The French and British ambassadors had set themselves up at Poros

and invited Constantinople to send a diplomat there so as to pursue negotiations over the status of Greece. The Porte persisted in refusing to participate in conferences. Hence, the French suggested continuing military operations and extending them into Attica

and Euboea

. The British opposed this plan. Thus it was left to the Greeks to drive out the Ottomans from these territories, with the understanding that the French army would only intervene if the Greeks found themselves in trouble.

Gradually, Morea was evacuated of troops. The Schneider brigade, of which Cavaignac was a member, boarded ship in the first days of April 1829. General Maison left on May 22, 1829. Only one brigade remained in the Peloponnese. Fresh troops came from France to relieve the soldiers present in Greece: thus, the 57th line infantry regiment

landed at Navarino on July 25, 1830. France did not withdraw for good until after King Otto

arrived in Greece in January 1833.

The French troops, commanded by General Charles Louis Joseph Olivier Guéhéneuc, did not remain idle during these nearly five years. Fortifications were raised, like those at Navarino. Bridges were constructed, such as those over the Pamissos River

between Kalamata

and Methoni

. The Methoni-Navarino road was built, and improvements were made to Peloponnesian towns (barracks, bridges, gardens, etc.).

After the Morea military expedition, the Greeks only had to face the Turkish troops in central Greece. Livadeia

, gateway to Boeotia, was conquered at the beginning of November 1828. A counterattack by Mahmud Pasha from Euboea was repulsed in January 1829. In April, Naupactus

was “restored” to the Greeks; in May, Augustinos Kapodistrias

recaptured the symbolic town of Messolonghi. However, it took the military victory of Russia and the Treaty of Adrianople

before the independence of Greece was recognised.

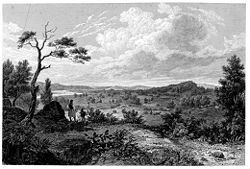

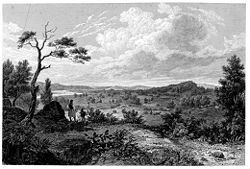

The Greek territories that had been liberated by September 1829, a year after the Morea military expedition—the Peloponnese and central Greece—were those which would form independent Greece after 1832.

The Morea expedition was the second of the great military-scientific expeditions led by France in the first half of the 19th century. The first, used as a benchmark, had been the Egyptian one, starting in 1798; the last took place in Algeria

The Morea expedition was the second of the great military-scientific expeditions led by France in the first half of the 19th century. The first, used as a benchmark, had been the Egyptian one, starting in 1798; the last took place in Algeria

from 1839. All took place at the initiative of the French government and were placed under the guidance of a particular ministry (Foreign relations for Egypt, Interior for Morea and War for Algeria). The great scientific institutions recruited learned men (both civilians and from the military) and specified their missions, but in situ work took place in close co-operation with the army.

The Commission of Sciences and Arts from Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition, and especially the publications that followed, had become a model. As Greece was the other important “ancient” region considered as lying at the origin of Western civilisation (one of the philhellenists’ principal arguments), it was decided to “take advantage of the presence of our soldiers who were occupying Morea to send a learned commission. It did not have to equal that attached to the glory of Napoleon […] It did however need to render eminent services to the arts and sciences.”

In Egypt and Algeria, scientific work took place under the army’s protection. In Morea, most troops were departing when exploration had barely begun. The army was content to provide logistical support: “tents, stakes, tools, liquid containers, large pots and sacks; in a word, everything that could be found for us to use in the army’s storehouses.”

The members of the scientific expedition landed at Navarino on March 3, 1829, after 21 days at sea.

(Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent

, Louis Despreaux Saint-Sauveur and Antoine Vincent Pector), geography

, geology (Pierre Théodore Virlet d’Aoust and Émile Puillon Boblaye) and zoology

. The government insisted that a landscape artist also be sent, as Minister of the Interior

Martignac

had asked for one so as not to restrict the observations “to flies and herbs, but to extend them to places and people.”

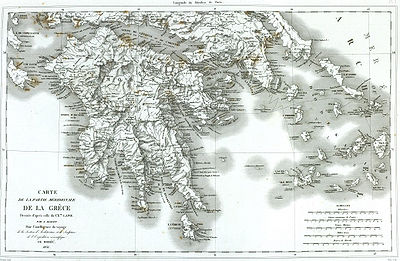

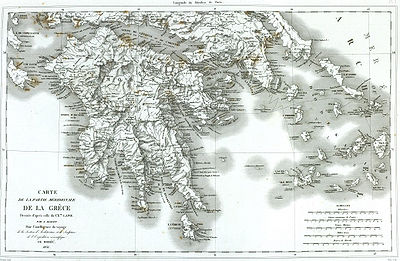

In two years, a very precise map, drawn on six sheets at a 1/200,000 scale, was produced. In March 1829, a base of 3,500 meters had been traced in Argolis

, from one angle at the ruins of Tiryns

to an angle of a house in ruins in the village of Aria. This was intended to serve as a point of departure in all the triangulation operations for topographic and geodesic readings in the Peloponnese. Pierre Peytier and Puillon-Boblaye proceeded to perform numerous verifications on the base and on the rulers used. The margin of error was thus reduced to 1 meter for every 15 kilometer. The longitude and latitude of the base point at Tiryns were read and checked, so that again the margin of error was reduced as far as possible to an estimated 0.2 seconds

. 134 geodesic stations were set up on the peninsula’s mountains, as well as on Aegina

, Hydra

and Nafplion

. Thus, equilateral triangles whose sides measured about 20 km were drawn. The angles were measured with theodolites by Gambey.

The geographers suffered from fever—Bory de Saint-Vincent’s team as much as that of Puillon-Boblaye:

led the scientific expedition. Additionally, he made detailed botanical studies. He gathered a multitude of specimens: Flore de Morée (1832) lists 1,550 plants, of which 33 were orchids

and 91 were grasses

(just 42 species had not yet been described); Nouvelle Flore du Péloponnèse et des Cyclades (1838) described 1,821 species. In Morea, Bory de Saint-Vincent was content to collect plants. He proceeded to classify, identify and describe them upon his return to France. Then he was aided, not by his collaborators from Greece, but by Louis Athanase Chaubard, Jean-Baptiste Fauché and Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart. Similarly, the naturalists Étienne

and Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

helped edit the expedition’s scientific works.

As the gathering process went along, they sent the plants, as well as birds and fish, to France.

The Morea expedition confirmed that the jackal

existed in Greece. Although earlier travel narratives had mentioned its presence, these were not considered trustworthy. Moreover, the species seen and described by the French was endemic to the region. Bory de Saint-Vincent brought back pelts and a skull.

This section was formed by the Institut de France

This section was formed by the Institut de France

, which designated the architect Guillaume-Abel Blouet

as its head. The Institut sent Amable Ravoisié, Pierre Achille Poirot, Frédéric de Gournay and Pierre Félix Trezel as his assistants.

The architect Jean-Nicolas Huyot

gave very precise instructions to this section. Of wide-ranging experience formed in Asia Minor

and Egypt and under the influence of engineers, he asked them to keep an authentic diary of their excavations where precision measurements read off watches and compasses should be written down, to draw a map of the region they travelled, and to describe the layout of the terrain.

at Pylos

); then on pages 9–10, the Navarino-Methoni road is detailed with four pages of plates (a church in ruins and its frescoes, but also bucolic landscapes reminding the reader that the scene is not so far from Arcadia

); and finally three pages on Methoni and four pages of plates. The bucolic landscapes were rather close to the “norm” that Hubert Robert

had proposed for depictions of Greece.

The presence of troops from the expeditionary corps was important, alternating with that of Greek shepherds:

The presence of troops from the expeditionary corps was important, alternating with that of Greek shepherds:

The archaeological expedition travelled through Navarino (Pylos), Methoni, Koroni, Messene

and Olympia

(described in the publication’s first volume); Bassae

, Megalopolis

, Sparta

, Mantineia

, Argos

, Mycenae

, Tiryns and Nafplion (subjects of the second volume); the Cyclades

(Syros

, Kea

, Mykonos

, Delos

, Naxos and Milos

), Sounion

, Aegina, Epidaurus

, Troezen

, Nemea

, Corinth

, Sicyon

, Patras

, Elis

, Kalamata, the Mani Peninsula

, Cape Matapan

, Monemvasia

, Athens, Salamis Island

and Eleusina

(covered in volume III).

Edgar Quinet

had left with the rest of the expedition. However, from the time he arrived in Greece, he kept apart from his companions, as did another member of his section, the Lyon

sculptor Jean-Baptiste Vietty. The two travelled through the Peoloponnese separately and Quinet visited Piraeus

on April 21, 1829, thence reaching Athens. He saw the Cyclades in May, starting with Syros. Having taken ill, he returned to France on June 5, and his Grèce moderne et ses rapports avec l’Antiquité appeared in September 1831. Vietty pursued his research in Greece until August 1831, long after the expedition had returned to France at the end of 1829.

) against the texts of ancient authors like Homer

, Pausanias

or Strabo

. Thus, at Navarino, the location of Nestor’s palace was determined from Homer and the adjectives “inaccessible” and “sandy”. At Methoni, “the ancient remains of the port of which the description matches perfectly with that of Pausanias are enough to determine with certainty the location of the ancient town.”

Having explored Navarino, Methoni and Koroni, the members of the expedition returned to Messene, where they spent a month starting on April 10.

The expedition spent six weeks, starting on May 10, 1829, in Olympia

The expedition spent six weeks, starting on May 10, 1829, in Olympia

. Abel Blouet and Dubois undertook the first excavations there. They were accompanied by the painters Poirot, Trezel and Duval. The archaeological advice of Huyot was followed:

The site was divided into squares and excavations were undertaken in straight lines: archaeology was becoming rationalised, and it was in this way that the location of the temple of Zeus

was determined. The simple chase after treasure was beginning to be abandoned.

The fundamental contribution of the Morea scientific expedition was in effect its quasi-disinterest in pillage and treasure hunting. Blouet refused to perform excavations that risked damaging the monuments, and banned the mutilation of statues with the intent of taking a piece separated from the rest of the statue without regard. It is perhaps for this reason that the three metopes

of the temple of Zeus discovered at Olympia were brought back in their entirety. In any case, this willingness to protect the integrity of monuments undoubtedly represented an epistemological progress.

The French did not limit their interest to Antiquity; they also described and drew Byzantine monuments. Quite often, and until then for the travellers as well, only Ancient Greece mattered; medieval and modern Greece were ignored. Blouet, in his Expédition de Morée, gave very precise descriptions of the churches he saw. For instance, plate 9 (I, II and III) of volume I deals with:

The French did not limit their interest to Antiquity; they also described and drew Byzantine monuments. Quite often, and until then for the travellers as well, only Ancient Greece mattered; medieval and modern Greece were ignored. Blouet, in his Expédition de Morée, gave very precise descriptions of the churches he saw. For instance, plate 9 (I, II and III) of volume I deals with:

, of a French scientific institution, l’École française d'Athènes.

Note: It is very difficult to find a complete and exhaustive list of the members of the scientific expedition. Often, it is necessary to make conjectures based on incomplete information. Names marked are those found in various sources, but still in doubt.

, n°165 (2002) “Notice sur les opérations géodésiques exécutées en Morée, en 1829 et 1830, par MM. Peytier, Puillon-Boblay et Servier ; suivie d’un catalogue des positions géographiques des principaux points déterminés par ces opérations.”, in Bulletin de la Société de géographie, v. 19 n°117–122 (January – June 1833) Witmore, C.L. 2005: “The Expedition scientifique de Moree and a map of the Peloponnesus.” Dissertation on the Metamedia site at Stanford University

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

, between 1828 and 1833, at the time of the Greek War of Independence

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between...

.

After the fall of Messolonghi, Western Europe decided to intervene in favour of revolutionary Greece. Their attitude toward the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

's Egypt

Egypt under Muhammad Ali and his successors

The history of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali Pasha dynasty spanned the later period of Ottoman Egypt, the Khedivate of Egypt under British patronage, and the nominally independent Sultanate of Egypt and Kingdom of Egypt, ending with the Revolution of 1952 and the formation of the Republic of...

ian ally, Ibrahim Pasha

Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt

Ibrahim Pasha was the eldest son of Muhammad Ali, the Wāli and unrecognised Khedive of Egypt and Sudan. He served as a general in the Egyptian army that his father established during his reign, taking his first command of Egyptian forces was when he was merely a teenager...

, was especially critical; their primary objective was to elicit the evacuation of the occupied regions, the Peloponnese in particular. The intervention began when a Franco

Bourbon Restoration

The Bourbon Restoration is the name given to the period following the successive events of the French Revolution , the end of the First Republic , and then the forcible end of the First French Empire under Napoleon – when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the...

-Russo

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

-British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

fleet was sent to the region, winning the Battle of Navarino

Battle of Navarino

The naval Battle of Navarino was fought on 20 October 1827, during the Greek War of Independence in Navarino Bay , on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. A combined Ottoman and Egyptian armada was destroyed by a combined British, French and Russian naval force...

in October 1827. In August 1828, a French expeditionary corps disembarked at Koroni

Koroni

Koroni or Coroni is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is a municipal unit. Known as Corone by the Venetians and Ottomans, the town of Koroni Koroni or Coroni is a...

in the southern Peloponnese. The soldiers were stationed on the peninsula until the evacuation of Egyptian troops in October, then taking control of the principal strongholds still held by Turkish troops. Although the bulk of the troops returned to France from the end of 1828, there was a French presence in the area up until 1833.

As during Napoleon's

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

Egyptian Campaign

French Revolutionary Wars: Campaigns of 1798

1798 was a relatively quiet period in the French Revolutionary Wars. The major continental powers in the First coalition had made peace with France, leaving France dominant in Europe with only a slow naval war with Great Britain to worry about...

, when a Commission of Sciences and Arts

Egyptian Institute of Sciences and Arts

The Commission des Sciences et des Arts or "Commission of the Sciences and Arts" was a French learned body set up on 16 March 1798. It was made up of 167 members, of which all but 16 joined Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Egypt and produced the Description de l'Égypte...

had accompanied the military campaign, a Morea scientific mission (Mission scientifique de Morée) accompanied the troops. Seventeen learned men represented different specialties (natural history and antiquities – archaeology, architecture and sculpture) made the voyage. Their work was of major importance in increasing knowledge about the country. As an example, the topographic maps they produced were excellent. More significantly, the measurements, drawings, profiles, plans and proposals for the theoretical restoration of Peloponnesian monuments, of Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

and of the Cyclades

Cyclades

The Cyclades is a Greek island group in the Aegean Sea, south-east of the mainland of Greece; and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name refers to the islands around the sacred island of Delos...

were, following James Stuart

James Stuart (1713-1788)

James "Athenian" Stuart was an English archaeologist, architect and artist best known for his central role in pioneering Neoclassicism.-Early life:...

and Nicholas Revett

Nicholas Revett

Nicholas Revett was a Suffolk gentleman and amateur architect and artist.He is best known for his famous work with James Stuart documenting the ruins of ancient Athens. Its illustrations compose 5 folio volumes and include 368 etched and engraved plates, plans and maps drawn at scale...

's Antiquities of Athens, a new attempt to systematically and exhaustively catalogue ancient Greek ruins. The Morea expedition and its publications offered a near-complete description of the regions visited. They formed a scientific, aesthetic and human inventory that remained one of the best means, short of visiting them in person, to get to know the regions.

Military and diplomatic context

In 1821, the Greeks revolted against centuries-long Ottoman ruleOttoman Greece

Most of Greece gradually became part of the Ottoman Empire from the 15th century until its declaration of independence in 1821, a historical period also known as Tourkokratia ....

. They won numerous victories early on and declared independence. However, the declaration contradicted the principles of the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

and of the Holy Alliance

Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance was a coalition of Russia, Austria and Prussia created in 1815 at the behest of Czar Alexander I of Russia, signed by the three powers in Paris on September 26, 1815, in the Congress of Vienna after the defeat of Napoleon.Ostensibly it was to instill the Christian values of...

, which imposed a European equilibrium of the status quo, outlawing any change. In contrast to what happened elsewhere in Europe, the Holy Alliance did not intervene to stop the liberal Greek insurgents.

The liberal and national uprising displeased the Austria

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

of Metternich's

Klemens Wenzel von Metternich

Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich was a German-born Austrian politician and statesman and was one of the most important diplomats of his era...

, the principal political architect of the Holy Alliance. However, Russia, another reactionary gendarme of Europe, was favourable to the insurrection due to its Orthodox

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

religious solidarity and its geostrategic interest (control of the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

and the Bosphorus). France, another active member of the Holy Alliance which had just intervened in Spain against liberals at Trocadero

Battle of Trocadero

The Battle of Trocadero, fought on 31 August 1823, was the only significant battle in the French invasion of Spain when French forces defeated the Spanish liberal forces and restored the absolute rule of King Ferdinand VII.-Prelude:...

, had an ambiguous position: the liberal Greeks were first and foremost Christians, and their uprising against the Muslim Ottomans had undertones of a new crusade. Great Britain, a liberal country, was interested in the regional situation primarily because it lay on the route to India

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

and London wished to exercise a form of control there. For all of Europe, Greece represented the cradle of civilisation and of art since antiquity.

Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha was a commander in the Ottoman army, who became Wāli, and self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan...

, who had dispatched his son Ibrahim Pasha

Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt

Ibrahim Pasha was the eldest son of Muhammad Ali, the Wāli and unrecognised Khedive of Egypt and Sudan. He served as a general in the Egyptian army that his father established during his reign, taking his first command of Egyptian forces was when he was merely a teenager...

to Greece with a fleet and 8,000 men, later adding 25,000. Ibrahim’s intervention was decisive: the Peloponnese had been reconquered in 1825; the gateway town of Messolonghi had fallen in 1826; Athens had been taken in 1827. All that Greek nationalists still held was Nafplion

Nafplion

Nafplio is a seaport town in the Peloponnese in Greece that has expanded up the hillsides near the north end of the Argolic Gulf. The town was the first capital of modern Greece, from the start of the Greek Revolution in 1821 until 1834. Nafplio is now the capital of the peripheral unit of...

, Hydra

Hydra, Saronic Islands

Hydra is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece, located in the Aegean Sea between the Saronic Gulf and the Argolic Gulf. It is separated from the Peloponnese by narrow strip of water...

, Mani

Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula , also long known as Maina or Maïna, is a geographical and cultural region in Greece. Mani is the central peninsula of the three which extend southwards from the Peloponnese in southern Greece. To the east is the Laconian Gulf, to the west the Messenian Gulf...

and Aegina

Aegina

Aegina is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of Aeacus, who was born in and ruled the island. During ancient times, Aegina was a rival to Athens, the great sea power of the era.-Municipality:The municipality...

.

A strong current of philhellenism

Philhellenism

Philhellenism was an intellectual fashion prominent at the turn of the 19th century, that led Europeans like Lord Byron or Charles Nicolas Fabvier to advocate for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire...

developed in Western Europe. Thus it was decided to intervene in favour of Greece, the cradle of civilisation and a Christian vanguard in the Orient whose strategic location was clear. By the Treaty of London of July 1827, France, Russia and the United Kingdom recognised the autonomy of Greece, which remained a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The three powers agreed to a limited intervention in order to convince the Porte to accept the terms of the convention. A plan to send a naval expedition as a show of force was proposed and adopted. A joint Russian, French and British fleet was sent to exercise diplomatic pressure against Constantinople. The Battle of Navarino

Battle of Navarino

The naval Battle of Navarino was fought on 20 October 1827, during the Greek War of Independence in Navarino Bay , on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. A combined Ottoman and Egyptian armada was destroyed by a combined British, French and Russian naval force...

, fought after a chance encounter, resulted in the destruction of the Turkish-Egyptian fleet.

In 1828, Ibrahim Pasha thus found himself in a difficult situation: he had just suffered a defeat at Navarino; the joint fleet exercised a blockade which prevented him from receiving reinforcements and supplies; his Albanian troops, whom he could no longer pay, had returned to their country under the protection of Theodoros Kolokotronis’ Greek troops. On August 6, 1828, a convention had been signed at Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

between the viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and the British admiral Edward Codrington

Edward Codrington

Admiral Sir Edward Codrington GCB RN was a British admiral, hero of the Battle of Trafalgar and the Battle of Navarino.-Early life and career:...

. Ibrahim Pasha had to evacuate his Egyptian troops and leave the Peloponnese to the few Turkish troops (estimated at 1200 men) remaining there. However, Ibrahim Pasha refused to honor the agreement that had been reached, continuing to control various Greek regions: Messenia

Messenia

Messenia is a regional unit in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, one of 13 regions into which Greece has been divided by the Kallikratis plan, implemented 1 January 2011...

, Navarino

Pylos

Pylos , historically known under its Italian name Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. It was the capital of the former...

, Patras

Patras

Patras , ) is Greece's third largest urban area and the regional capital of West Greece, located in northern Peloponnese, 215 kilometers west of Athens...

and several other strongholds. He had also ordered the systematic destruction of Tripoli

Tripoli, Greece

Tripoli is a city of about 25,000 inhabitants in the central part of the Peloponnese, in Greece. It is the capital of the prefecture of Arcadia and the centre of the municipality of Tripolis, pop...

.

In addition, the French government of Charles X

Charles X of France

Charles X was known for most of his life as the Comte d'Artois before he reigned as King of France and of Navarre from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. A younger brother to Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile and eventually succeeded him...

was beginning to have doubts about its Greek policy. Ibrahim Pasha himself noted this ambiguity when he met General Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison, 1er Marquis Maison was a Marshal of France and Minister of War.-French revolution and Napoléon:Maison was born at born in Épinay-sur-Seine, near Paris....

in September: “Why was France, after enslaving men in Spain in 1823, now coming to Greece to make men free?” At last, a liberal agitation, pro-Greek and inspired by what was then happening in that country, began to develop in France. The longer France waited, the more delicate her position vis-à-vis Metternich became. The ultra-royalist government thus decided to accelerate events. A land expedition was proposed to Great Britain, which refused to intervene directly. Meanwhile, Russia had declared war against the Ottoman Empire and its military victories were unsettling for London, which did not wish to see the Tsarist empire extend too far south. Great Britain was thus not opposed to an intervention by France alone.

Intellectual context

EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

philosophy had developed Western Europeans’ interest in Greece, or rather in an idealised Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

, the linchpin of Antiquity

Ancient history

Ancient history is the study of the written past from the beginning of recorded human history to the Early Middle Ages. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, with Cuneiform script, the oldest discovered form of coherent writing, from the protoliterate period around the 30th century BC...

, as it was perceived and taught. The Enlightenment philosophers, for whom the notions of Nature and Reason were so important, believed that these had been the fundamental values of Classical Athens. The Ancient Greek democracies, and above all Athens

Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed in the Greek city-state of Athens, comprising the central city-state of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica, around 508 BC. Athens is one of the first known democracies. Other Greek cities set up democracies, and even though most followed an Athenian model,...

, became models to emulate. There they searched for answers to the political and philosophical problems of their time. Works such as those of Abbé Barthélemy

Jean-Jacques Barthélemy

Jean-Jacques Barthélemy was a French writer and numismatist.-Early life:Barthélemy was born at Cassis, in Provence, and began his classical studies at the College of Oratory in Marseilles. He took up philosophy and theology at the Jesuits' college, and finally attended the seminary of the Lazarists...

, Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis

Anacharsis

Anacharsis was a Scythian philosopher who travelled from his homeland on the northern shores of the Black Sea to Athens in the early 6th century BCE and made a great impression as a forthright, outspoken "barbarian", apparently a forerunner of the Cynics, though none of his works have...

(1788), served to fix definitively the image that Europe had of the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

.

The theories and system of interpreting ancient art devised by Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art...

influenced European tastes for decades. His major work, History of Ancient Art, was published in 1764 and translated into French in 1766 (the English translation came later, in 1881). In this major work Winckelmann initiated the tradition of dividing ancient art into periods, classifying the works chronologically and stylistically.

The views of Winckelmann on art encompassed the entirety of civilisation. He drew a parallel between a civilisation's general level of development and the evolution of its art. He interpreted this artistic evolution the same way that his contemporaries saw the life cycle of a civilisation, in terms of progress, apogee and then decline. For him, Greek art had been the pinnacle of artistic achievement, culminating with Phidias

Phidias

Phidias or the great Pheidias , was a Greek sculptor, painter and architect, who lived in the 5th century BC, and is commonly regarded as one of the greatest of all sculptors of Classical Greece: Phidias' Statue of Zeus at Olympia was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World...

. Further, Winckelmann believed that the most beautiful works of Greek art had been produced under ideal geographic, political and religious circumstances. This frame of thought long dominated intellectual life in Europe. He classified Greek art into four periods: Ancient (archaic period), Sublime (Phidias), Beautiful (Praxiteles

Praxiteles

Praxiteles of Athens, the son of Cephisodotus the Elder, was the most renowned of the Attic sculptors of the 4th century BC. He was the first to sculpt the nude female form in a life-size statue...

) and Decadent (Roman period).

The French government had planned the Morea expedition in the same spirit as those of James Stuart

James Stuart (1713-1788)

James "Athenian" Stuart was an English archaeologist, architect and artist best known for his central role in pioneering Neoclassicism.-Early life:...

and Nicholas Revett

Nicholas Revett

Nicholas Revett was a Suffolk gentleman and amateur architect and artist.He is best known for his famous work with James Stuart documenting the ruins of ancient Athens. Its illustrations compose 5 folio volumes and include 368 etched and engraved plates, plans and maps drawn at scale...

, whose work it wished to complete. The semi-scientific expeditions commissioned and financed by the Society of Dilettanti remained a benchmark: these represented the first attempts to rediscover Ancient Greece. The first, that of Stuart and Revett to Athens and the islands, took place in 1751–1753, and resulted in The Antiquities of Athens, mined by architects and designers for a refined "Grecian" neoclassicism

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism is the name given to Western movements in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that draw inspiration from the "classical" art and culture of Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome...

. The expedition of Revett, Richard Chandler

Richard Chandler

Richard Chandler was an English antiquary.Chandler was educated at Winchester and at Queen's College, Oxford and Magdalen College, Oxford....

and William Pars to Asia Minor took place between 1764 and 1766. Finally, the “work

Elgin Marbles

The Parthenon Marbles, forming a part of the collection known as the Elgin Marbles , are a collection of classical Greek marble sculptures , inscriptions and architectural members that originally were part of the Parthenon and other buildings on the Acropolis of Athens...

” of Lord Elgin

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin and 11th Earl of Kincardine was a Scottish nobleman and diplomat, known for the removal of marble sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens. Elgin was the second son of Charles Bruce, 5th Earl of Elgin and his wife Martha Whyte...

on the Parthenon

Parthenon

The Parthenon is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their virgin patron. Its construction began in 447 BC when the Athenian Empire was at the height of its power. It was completed in 438 BC, although...

at the beginning of the 19th century had sparked further longing for Greece: it now seemed possible to build vast collections of ancient art in Western Europe.

Preparation

The Chamber of Deputies authorised a loan of 80 million gold francsFrench franc

The franc was a currency of France. Along with the Spanish peseta, it was also a de facto currency used in Andorra . Between 1360 and 1641, it was the name of coins worth 1 livre tournois and it remained in common parlance as a term for this amount of money...

to allow the government to meet its obligations. An expeditionary corps of 13,000–15,000 men commanded by Lieutenant-General Nicolas Joseph Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison, 1er Marquis Maison was a Marshal of France and Minister of War.-French revolution and Napoléon:Maison was born at born in Épinay-sur-Seine, near Paris....

was formed. It was composed of three brigades commanded by Field Marshals Tiburce Sébastiani, Philippe Higonet and Virgile Schneider. The Chief of the General Staff was General Antoine Simon Durrieu.

The expeditionary corps was made up of nine infantry regiments:

- 1st brigade: 8th line infantry regiment, 16th line infantry regiment, 27th light infantry regiment

- 2nd brigade: 35th line infantry regiment, 46th line infantry regiment, 58th line infantry regiment

- 3rd brigade: 29th line infantry regiment, 42nd line infantry regiment, 54th line infantry regiment

Also departing were the 3rd horse chasseurs regiment (commanded by Colonel Paul-Eugène de Faudoas-Barbazan), four companies of artillery (with equipment for campaigns, sieges, and mountains) of the 3rd and 8th artillery regiments, and two companies of military engineers (sappers and miners).

A transport fleet protected by warships was organised; sixty ships sailed in all. Equipment, victuals, munitions and 1,300 horses had to be brought over, as well as arms, munitions and money for the Greek provisional government of John Capodistria. France wished to support free Greece as it came into being by helping it activate its army. The goal was of course to maintain influence in the region.

The first brigade left Toulon

Toulon

Toulon is a town in southern France and a large military harbor on the Mediterranean coast, with a major French naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region, Toulon is the capital of the Var department in the former province of Provence....

on August 17; the second, two days later; and the third on September 1. The general in command, Nicolas Joseph Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison, 1er Marquis Maison was a Marshal of France and Minister of War.-French revolution and Napoléon:Maison was born at born in Épinay-sur-Seine, near Paris....

, was with the first brigade, aboard the ship of the line

Ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed from the 17th through the mid-19th century to take part in the naval tactic known as the line of battle, in which two columns of opposing warships would manoeuvre to bring the greatest weight of broadside guns to bear...

Ville de Marseille. The first convoy was composed of merchant ships and apart from the Ville de Marseille, it included the frigates Amphitrite, Bellone and Cybèle. The second convoy was escorted by ship of the line Duquesne and the frigates Iphigénie and Armide.

Landing

Methoni, Messenia

Methoni is a village and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is a municipal unit. Its name may be derived from Mothona, a mythical rock. It is located 11 km south of Pylos and...

. Thus, the landing was risky. The fleet sailed toward the Gulf of Koroni

Koroni

Koroni or Coroni is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is a municipal unit. Known as Corone by the Venetians and Ottomans, the town of Koroni Koroni or Coroni is a...

protected by a fortress held by the Ottomans. The expeditionary corps began to disembark without meeting any opposition on the evening of August 29, finishing on the morning of August 30. A proclamation by governor Capodistria had informed the Greek population of the imminent arrival of a French expedition. The locals rushed up before the troops as soon as they set foot on Greek soil and offered them food.

The French pitched camp in the plain of Koroni, near Petalidi, on the site of the ancient Coronea. The third brigade, which had borne up against a storm and lost three ships, managed to land at Koroni on September 16.

Departure of the Egyptian Army

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

. On September 24, Louis-Eugène Cavaignac wrote that thirty men of 400 in his company of military engineers were affected by fever. General Maison wished to be able to set up his men in the fortresses’ barracks. On September 7, Ibrahim Pasha accepted to evacuate his troops as of September 9. The agreement reached with General Maison provided that the Egyptians would leave with their arms, baggage and horses, but without any Greek slave or prisoner. As the Egyptian fleet could not evacuate the entire army in one go, supplies were authorised for the troops who remained on land; these men had just undergone a lengthy blockade. A first Egyptian division, 5,500 men and 27 ships, set sail on September 16, escorted by three ships from the joint fleet (two English ones and the French frigate

Frigate

A frigate is any of several types of warship, the term having been used for ships of various sizes and roles over the last few centuries.In the 17th century, the term was used for any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built"...

Sirène).

The last Egyptian transport sailed away on October 5, taking Ibrahim Pasha. Of the 40,000 men he had brought from Egypt, he was taking back barely 20,000. A few Ottoman soldiers remained in order to hold the different strongholds of the Peloponnese. The next mission of the French troops was to “give security” to these and hand them back to independent Greece.

Strongholds taken

Henri de Rigny

Marie Henri Daniel Gauthier, comte de Rigny was the commander of the French squadron at the Battle of Navarino in the Greek War of Independence.-Biography:...

’s fleet and the land siege was undertaken by General Higonet’s soldiers. The Turkish commander of the fort refused to surrender:

“The Porte is at war with neither the French nor the English; we will commit no hostile act, but we will not surrender the fort.”

Hence, the sappers received an order to open a breach in the walls. General Higonet entered the fortress, held by 250 men who surrendered with sixty cannons and 800,000 rounds of ammunition. The French troops moved in intending to remain for some time, building up Navarino’s fortifications, rebuilding its houses and setting up a hospital and various features of local administration.

Patras

Patras

Patras , ) is Greece's third largest urban area and the regional capital of West Greece, located in northern Peloponnese, 215 kilometers west of Athens...

had been controlled by Ibrahim Pasha since the evacuation of the Peloponnese. The third brigade had been sent by sea to take the city, located in the north-western part of the peninsula. It landed on October 4. General Schneider gave Hajji Abdullah, Pasha of Patras and of the “Morea Castle”, twenty-four hours to hand over the fort. On October 5, when the ultimatum expired, three columns marched on the city and the artillery was deployed. The Pasha immediately signed the capitulation of Patras and of the “Morea Castle”. However, the aghas who commanded the latter refused to obey their pasha, whom they considered a traitor, and announced that they would rather die in the ruins of their fortress than surrender.

Siege of the "Morea Castle"

“Morea Castle”, called Kastro Moreas or Kastelli, today in ruins, guarded the entry to the Gulf of CorinthGulf of Corinth

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece...

, near Rion

Rio, Greece

Rio is a town and a former municipality in Achaea, West Greece, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Patras, of which it is a municipal unit. The former municipality had a population of around 13,000.- Geography :...

. Bayezid II

Bayezid II

Bayezid II or Sultân Bayezid-î Velî was the oldest son and successor of Mehmed II, ruling as Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512...

had built it in 1499.

General Schneider negotiated with the aghas, who persisted in their refusal to surrender. A siege was begun from in front of the fortress and fourteen marine and field guns, placed a little over 400 meters away, reduced the artillery of those under siege to silence. Admiral de Rigny had General Maison put all his artillery and sappers on board. By land Maison sent two infantry regiments and the 3rd light cavalry regiment. Reinforcements arrived on October 23. New batteries nicknamed “for breaching” (de brèche) were installed. These received the names of Charles X

Charles X of France

Charles X was known for most of his life as the Comte d'Artois before he reigned as King of France and of Navarre from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. A younger brother to Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile and eventually succeeded him...

, George IV

George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

, duc d’Angoulême

Louis-Antoine, Duke of Angouleme

Louis Antoine of France, Duke of Angoulême was the eldest son of Charles X of France and, from 1824 to 1836, the last Dauphin of France...

, duc de Bordeaux

Henri, comte de Chambord

Henri, comte de Chambord was disputedly King of France from 2 to 9 August 1830 as Henry V, although he was never officially proclaimed as such...

and “Marine”. A party from the British fleet and the French frigate Blonde came to add their cannons.

On October 30, the batteries opened fire. In four hours, a breach was largely opened in the ramparts. Then, an emissary came out with a white flag to negotiate the terms of the fort’s surrender. General Maison replied that the terms had been negotiated at the beginning of the month at Patras. He added that he did not trust a group of besieged men who had not respected a first agreement to respect a second one. He gave the garrison half an hour to evacuate the fort, without arms or baggage. The aghas submitted. However, the fortress’ resistance had cost 25 men, killed or wounded in the French expedition.

The French in the Peloponnese

On November 5, 1828, the last “non-Greeks” (Turks, Egyptians or Muslims generally) left Morea. 2,500 Turks and their families were placed aboard French vessels headed for SmyrnaIzmir

Izmir is a large metropolis in the western extremity of Anatolia. The metropolitan area in the entire Izmir Province had a population of 3.35 million as of 2010, making the city third most populous in Turkey...

.

The French and British ambassadors had set themselves up at Poros

Poros

Poros is a small Greek island-pair in the southern part of the Saronic Gulf, at a distance about 58 km south from Piraeus and separated from the Peloponnese by a 200-metre wide sea channel, with the town of Galatas on the mainland across the strait. Its surface is about and it has 4,117...

and invited Constantinople to send a diplomat there so as to pursue negotiations over the status of Greece. The Porte persisted in refusing to participate in conferences. Hence, the French suggested continuing military operations and extending them into Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

and Euboea

Euboea

Euboea is the second largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. The narrow Euripus Strait separates it from Boeotia in mainland Greece. In general outline it is a long and narrow, seahorse-shaped island; it is about long, and varies in breadth from to...

. The British opposed this plan. Thus it was left to the Greeks to drive out the Ottomans from these territories, with the understanding that the French army would only intervene if the Greeks found themselves in trouble.

Gradually, Morea was evacuated of troops. The Schneider brigade, of which Cavaignac was a member, boarded ship in the first days of April 1829. General Maison left on May 22, 1829. Only one brigade remained in the Peloponnese. Fresh troops came from France to relieve the soldiers present in Greece: thus, the 57th line infantry regiment

57th Line Infantry Regiment

The 57th Line Infantry Regiment or is a regiment of the French Army, heir of the Beauvoisis Regiment. It comes from a tradition carried since 1667. The Regiment has since its creation been in an almost continuous existence: under the Kingdom of France, the French First Republic, the First French...

landed at Navarino on July 25, 1830. France did not withdraw for good until after King Otto

Otto of Greece

Otto, Prince of Bavaria, then Othon, King of Greece was made the first modern King of Greece in 1832 under the Convention of London, whereby Greece became a new independent kingdom under the protection of the Great Powers .The second son of the philhellene King Ludwig I of Bavaria, Otto ascended...

arrived in Greece in January 1833.

The French troops, commanded by General Charles Louis Joseph Olivier Guéhéneuc, did not remain idle during these nearly five years. Fortifications were raised, like those at Navarino. Bridges were constructed, such as those over the Pamissos River

Pamissos River

The Pamisos is a river that flows entirely in the Messenia prefecture of the southern Peloponnese in Greece.-Geography:The river flows from Mount Lykaio to the north in a rocky area filled with grasslands, scrubland and the occasional tree, while a number of villages lie within the riverine area...

between Kalamata

Kalamata

Kalamata is the second-largest city of the Peloponnese in southern Greece. The capital and chief port of the Messenia prefecture, it lies along the Nedon River at the head of the Messenian Gulf...

and Methoni

Methoni, Messenia

Methoni is a village and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is a municipal unit. Its name may be derived from Mothona, a mythical rock. It is located 11 km south of Pylos and...

. The Methoni-Navarino road was built, and improvements were made to Peloponnesian towns (barracks, bridges, gardens, etc.).

Military results of the expedition

The Ottoman Empire could no longer depend on Egyptian troops to hold Greece. The strategic situation now resembled that existing before 1825 and the landing of Ibrahim Pasha. Then, the Greek insurgents had triumphed on all fronts.After the Morea military expedition, the Greeks only had to face the Turkish troops in central Greece. Livadeia

Livadeia

Livadeia is a city in central Greece. It is the capital of the prefecture Boeotia. Livadeia is located 130 km NW of Athens, E of Nafpaktos, ESE of Amfissa and Desfina, SE of Lamia and west of Chalkida. Livadeia is linked with GR-48 and several kilometres west of GR-3. The area around Livadeia...

, gateway to Boeotia, was conquered at the beginning of November 1828. A counterattack by Mahmud Pasha from Euboea was repulsed in January 1829. In April, Naupactus

Naupactus

Naupactus or Nafpaktos , is a town and a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Nafpaktia, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

was “restored” to the Greeks; in May, Augustinos Kapodistrias

Augustinos Kapodistrias

Count Augustinos Ioannis Maria Kapodistrias was a Greek soldier and politician. He was born in Corfu. Kapodistrias was the younger brother of Ioannis Kapodistrias, first Governor of Greece...

recaptured the symbolic town of Messolonghi. However, it took the military victory of Russia and the Treaty of Adrianople

Treaty of Adrianople

The Peace Treaty of Adrianople concluded the Russo-Turkish War, 1828-1829 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. It was signed on September 14, 1829 in Adrianople by Russia's Count Alexey Fyodorovich Orlov and by Turkey's Abdul Kadyr-bey...

before the independence of Greece was recognised.

The Greek territories that had been liberated by September 1829, a year after the Morea military expedition—the Peloponnese and central Greece—were those which would form independent Greece after 1832.

Scientific expedition

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

from 1839. All took place at the initiative of the French government and were placed under the guidance of a particular ministry (Foreign relations for Egypt, Interior for Morea and War for Algeria). The great scientific institutions recruited learned men (both civilians and from the military) and specified their missions, but in situ work took place in close co-operation with the army.