Noble savage

Encyclopedia

Other

The Other or Constitutive Other is a key concept in continental philosophy; it opposes the Same. The Other refers, or attempts to refer, to that which is Other than the initial concept being considered...

"), and refers to the literary stock character

Stock character

A Stock character is a fictional character based on a common literary or social stereotype. Stock characters rely heavily on cultural types or names for their personality, manner of speech, and other characteristics. In their most general form, stock characters are related to literary archetypes,...

of the same. In English the phrase first appeared in the 17th century in John Dryden

John Dryden

John Dryden was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden.Walter Scott called him "Glorious John." He was made Poet...

's heroic play, The Conquest of Granada

The Conquest of Granada

The Conquest of Granada is a Restoration era stage play, a two-part tragedy written by John Dryden that was first acted in 1670 and 1671 and published in 1672...

(1672), where it was used by a Christian prince disguised as a Spanish Muslim to refer to himself, but it later became identified with the idealized picture of "nature's gentleman", which was an aspect of 18th-century sentimentalism

Moral sense theory

Moral sense theory is a view in meta-ethics according to which morality is somehow grounded in moral sentiments or emotions...

. The noble savage achieved prominence as an oxymoron

Oxymoron

An oxymoron is a figure of speech that combines contradictory terms...

ic rhetorical device after 1851, when used sarcastically as the title for satirical essay by English novelist Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

, who wished to disassociate himself from 18th and early 19th-century romantic primitivism

Primitivism

Primitivism is a Western art movement that borrows visual forms from non-Western or prehistoric peoples, such as Paul Gauguin's inclusion of Tahitian motifs in paintings and ceramics...

.

The idea that in a state of nature

State of nature

State of nature is a term in political philosophy used in social contract theories to describe the hypothetical condition that preceded governments...

humans are essentially good is often attributed to the Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury was an English politician, philosopher and writer.-Biography:...

, a whig supporter of constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

(such as England possessed after the Glorious Revolution

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

of 1688). In his Inquiry Concerning Virtue (1699), Shaftesbury had postulated that the moral sense

Moral sense theory

Moral sense theory is a view in meta-ethics according to which morality is somehow grounded in moral sentiments or emotions...

in humans is natural and innate and based on feelings rather than resulting from the indoctrination of a particular religion. Like many of his contemporaries, Shaftesbury was reacting to Hobbes's justification of royal absolutism in his Leviathan, Chapter XIII

Leviathan (book)

Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil — commonly called simply Leviathan — is a book written by Thomas Hobbes and published in 1651. Its name derives from the biblical Leviathan...

, in which he famously holds that the state of nature is a "war of all against all" in which men's lives are "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short". The notion of the state of nature itself derives from the republican writings of Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

and of Lucretius

Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is an epic philosophical poem laying out the beliefs of Epicureanism, De rerum natura, translated into English as On the Nature of Things or "On the Nature of the Universe".Virtually no details have come down concerning...

, both of whom enjoyed great vogue in the 18th century, after having been revived amid the optimistic atmosphere of Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an activity of cultural and educational reform engaged by scholars, writers, and civic leaders who are today known as Renaissance humanists. It developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval...

.

Pre-history of the noble savage

French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the name given to a period of civil infighting and military operations, primarily fought between French Catholics and Protestants . The conflict involved the factional disputes between the aristocratic houses of France, such as the House of Bourbon and House of Guise...

and Thirty Years War. During one event, the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew (1572), some ten to twenty thousand men, women, and children were massacred by Catholic mobs, chiefly in Paris, but also throughout France. This horrifying breakdown of civil control was deeply disturbing to thoughtful people on both sides of the religious divide.

In his famous essay "Of Cannibals" (1580), Michel de Montaigne, himself a Catholic, reported that the Tupinambá people of Brazil ceremoniously eat the bodies of their dead enemies as a matter of honor, but he reminded his readers that Europeans behave even more barbarously when they burn each other alive for disagreeing about religion (he implies): "One calls 'barbarism' whatever he is not accustomed to." In "Of Cannibals" Montaigne uses cultural

Cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is the principle that an individual human's beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual's own culture. This principle was established as axiomatic in anthropological research by Franz Boas in the first few decades of the 20th century and...

(but not moral

Moral relativism

Moral relativism may be any of several descriptive, meta-ethical, or normative positions. Each of them is concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different people and cultures:...

) relativism

Relativism

Relativism is the concept that points of view have no absolute truth or validity, having only relative, subjective value according to differences in perception and consideration....

for the purpose of satire. His cannibals are neither noble nor especially good, but not worse than 16th-century Europeans. In this classical humanist view, customs differ but people everywhere are prone to cruelty, a quality that Montaigne detested.

The treatment of indigenous peoples by the Spanish Conquistadors also produced a great deal of bad conscience and recriminations. The Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas O.P. was a 16th-century Spanish historian, social reformer and Dominican friar. He became the first resident Bishop of Chiapas, and the first officially appointed "Protector of the Indians"...

, who witnessed it, may have been the first to idealize the simple life of the indigenous Americans. He and other observers praised their simple manners and reported that they were incapable of lying.

European angst over colonialism

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

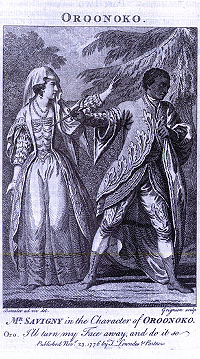

inspired fictional treatments such as Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn was a prolific dramatist of the English Restoration and was one of the first English professional female writers. Her writing contributed to the amatory fiction genre of British literature.-Early life:...

's novel Oroonoko

Oroonoko

Oroonoko is a short work of prose fiction by Aphra Behn , published in 1688, concerning the love of its hero, an enslaved African in Surinam in the 1660s, and the author's own experiences in the new South American colony....

, or the Royal Slave (1688), about a slave revolt in Surinam in the West Indies. Behn's story was not primarily a protest against slavery but was written for money; and it met readers' expectations by following the conventions of the European romance novella.

The leader of the revolt, Oroonoko, is truly noble in that he is a hereditary African prince, and he laments his lost African homeland in the traditional terms of a classical Golden Age

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology and legend and refers to the first in a sequence of four or five Ages of Man, in which the Golden Age is first, followed in sequence, by the Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and then the present, a period of decline...

. He is not a savage but dresses and behaves like a European aristocrat. Behn's story was adapted for the stage by Irish playwright Thomas Southerne

Thomas Southerne

Thomas Southerne , Irish dramatist, was born at Oxmantown, near Dublin, in 1660, and entered Trinity College, Dublin in 1676. Two years later he was entered at the Middle Temple, London....

, who stressed its sentimental aspects, and as time went on, it came to be seen as addressing the issues of slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

and colonialism

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

, remaining very popular throughout the 18th century.

Origin of term

In English, the phrase Noble Savage first appeared in poet DrydenJohn Dryden

John Dryden was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden.Walter Scott called him "Glorious John." He was made Poet...

's heroic play, The Conquest of Granada

The Conquest of Granada

The Conquest of Granada is a Restoration era stage play, a two-part tragedy written by John Dryden that was first acted in 1670 and 1671 and published in 1672...

(1672):

I am as free as nature first made man,

Ere the base laws of servitude began,

When wild in woods the noble savage ran.

The hero who speaks these words in Dryden's play is a Spanish Muslim, who, at the end of the play, in keeping with the requirements of a heroic drama, is revealed to have been, unbeknownst to himself, the son of a Christian prince (since heroic plays by definition had noble and exemplary protagonists).

Ethnomusicologist Ter Ellingson believes that Dryden had picked up the expression "noble savage" from a 1609 travelogue about Canada by the French explorer Marc Lescarbot, in which there was a chapter with the ironic heading: "The Savages are Truly Noble", meaning simply that they enjoyed the right to hunt game, a privilege in France granted only to hereditary aristocrats.

Dryden's use of the phrase is a striking oxymoron

Oxymoron

An oxymoron is a figure of speech that combines contradictory terms...

. However, in his day it would have been less so, for in English the word "savage" did not necessarily have the connotations of cruelty we now associate with it, but only gradually acquired them. Instead it could as easily mean "wild", as in a wild flower, as it still does in its French and Italian cognates, for example.

In France the stock figure

Stock character

A Stock character is a fictional character based on a common literary or social stereotype. Stock characters rely heavily on cultural types or names for their personality, manner of speech, and other characteristics. In their most general form, stock characters are related to literary archetypes,...

that in English is called the "noble savage" has always been simply "le bon sauvage", "the good wild man", a term without the any of the paradoxical frisson of the English one. This character, an idealized portrayal of "Nature's Gentleman", was an aspect of 18th-century sentimentalism

Sentimentalism (literature)

Sentimentalism , as a literary and political discourse, has occurred much in the literary traditions of all regions in the world, and is central to the traditions of Indian literature, Chinese literature, and Vietnamese literature...

, along with other stock characters such as, the Virtuous Milkmaid, the Servant-More-Clever-than-the-Master (such as Sancho Panza

Sancho Panza

Sancho Panza is a fictional character in the novel Don Quixote written by Spanish author Don Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra in 1605. Sancho acts as squire to Don Quixote, and provides comments throughout the novel, known as sanchismos, that are a combination of broad humour, ironic Spanish proverbs,...

and Figaro

Figaro

-Literature:* Figaro, the central character in:** The Barber of Seville by Beaumarchais***Il barbiere di Siviglia , the opera by Paisiello based on Beaumarchais' play...

, among countless others), and the general theme of virtue in the lowly born. Nature's Gentleman, whether European-born or exotic, takes his place in this cast of characters, along with the Wise Egyptian, Persian, and Chinaman.

He had always existed, from the time of the epic of Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh was the fifth king of Uruk, modern day Iraq , placing his reign ca. 2500 BC. According to the Sumerian king list he reigned for 126 years. In the Tummal Inscription, Gilgamesh, and his son Urlugal, rebuilt the sanctuary of the goddess Ninlil, in Tummal, a sacred quarter in her city of...

, where he appears as Enkiddu, the wild-but-good man who lives with animals. Another instance is the untutored-but-noble medieval knight, Parsifal

Parsifal

Parsifal is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner. It is loosely based on Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival, the 13th century epic poem of the Arthurian knight Parzival and his quest for the Holy Grail, and on Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail.Wagner first conceived the work...

. The Biblical shepherd boy David

David

David was the second king of the united Kingdom of Israel according to the Hebrew Bible and, according to the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, an ancestor of Jesus Christ through both Saint Joseph and Mary...

falls into this category. The association of virtue with withdrawal from society — and specifically from cities — was a familiar theme in religious literature.

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān is an Arabic philosophical novel and allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail in the early 12th century.- Translations :* from Wikisource* English translations of Hayy bin Yaqzan...

an Islamic philosophical tale (or thought experiment) by Ibn Tufail from 12th-century Andalusia, straddles the divide between the religious and the secular. The tale is of interest because it was known to the New England Puritan divine, Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather, FRS was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author and pamphleteer; he is often remembered for his role in the Salem witch trials...

. Translated in to English (from Latin) in 1686 and 1708, it tells the story of Hayy, a wild child

Wild Child

"Wild Child" is a 2001 single by Irish singer Enya. The song "Midnight Blue" has only been released on this single. The single was only available on CD in Germany, Japan and Korea. It was available on cassette in the UK...

, raised by a gazelle, without human contact, on a deserted island in the Indian Ocean. Purely through the use of his reason, Hayy goes through all the gradations of knowledge before emerging into human society, where he revealed to be a believer of Natural religion

Natural theology

Natural theology is a branch of theology based on reason and ordinary experience. Thus it is distinguished from revealed theology which is based on scripture and religious experiences of various kinds; and also from transcendental theology, theology from a priori reasoning.Marcus Terentius Varro ...

, which Cotton Mather, as a Christian Divine, identified with Primitive Christianity. The figure of Hayy is both a Natural man and a Wise Persian, but not a Noble Savage.

The locus classicus of the 18th-century portrayal of the American Indian are the famous lines from Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

's "Essay on Man" (1734):

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk or milky way;

Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n,

Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n;

Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd,

Some happier island in the wat'ry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold!

To be, contents his natural desire;

He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire:

But thinks, admitted to that equal sky,

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

To Pope, writing in 1734, the Indian was a purely abstract figure—"poor" because uneducated and a heathen but also happy because living close to Nature. This view reflects the typical Age of Reason

Age of reason

Age of reason may refer to:* 17th-century philosophy, as a successor of the Renaissance and a predecessor to the Age of Enlightenment* Age of Enlightenment in its long form of 1600-1800* The Age of Reason, a book by Thomas Paine...

belief that men are everywhere and in all times the same as well as a Deistic conception of natural religion (although Pope, like Dryden, was Catholic). Pope's phrase, "Lo the Poor Indian", became almost as famous as Dryden's "noble savage" and, in the 19th century, when more people began to have first hand knowledge of and conflict with the Indians, would be used derisively for similar sarcastic effect.

Attributes of romantic primitivism

In the 1st century AD, sterling qualities such as those enumerated above by Fénelon (excepting perhaps belief in the brotherhood of man) had been attributed by TacitusTacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire. The surviving portions of his two major works—the Annals and the Histories—examine the reigns of the Roman Emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Nero and those who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors...

in his Germania

Germania (book)

The Germania , written by Gaius Cornelius Tacitus around 98, is an ethnographic work on the Germanic tribes outside the Roman Empire.-Contents:...

to the German barbarians, in pointed contrast to the softened, Romanized Gauls

Gauls

The Gauls were a Celtic people living in Gaul, the region roughly corresponding to what is now France, Belgium, Switzerland and Northern Italy, from the Iron Age through the Roman period. They mostly spoke the Continental Celtic language called Gaulish....

. By inference Tacitus was criticizing his own Roman culture for getting away from its roots — which was the perennial function of such comparisons. Tacitus's Germans did not inhabit a "Golden Age

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology and legend and refers to the first in a sequence of four or five Ages of Man, in which the Golden Age is first, followed in sequence, by the Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and then the present, a period of decline...

" of ease but were tough and inured to hardship, qualities which he saw as preferable to the decadent softness of civilized life. In antiquity this form of "hard primitivism", whether admired or deplored (both attitudes were common), co-existed in rhetorical opposition to the "soft primitivism" of visions of a lost Golden Age

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology and legend and refers to the first in a sequence of four or five Ages of Man, in which the Golden Age is first, followed in sequence, by the Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and then the present, a period of decline...

of ease and plenty.

As art historian Erwin Panofsky

Erwin Panofsky

Erwin Panofsky was a German art historian, whose academic career was pursued mostly in the U.S. after the rise of the Nazi regime. Panofsky's work remains highly influential in the modern academic study of iconography...

explains:

There had been, from the beginning of classical speculation, two contrasting opinions about the natural state of man, each of them, of course, a "Gegen-Konstruktion" to the conditions under which it was formed. One view, termed "soft" primitivism in an illuminating book by Lovejoy and Boas, conceives of primitive life as a golden age of plenty, innocence, and happiness -- in other words, as civilized life purged of its vices. The other, "hard" form of primitivism conceives of primitive life as an almost subhuman existence full of terrible hardships and devoid of all comforts -- in other words, as civilized life stripped of its virtues.

In the 18th century the debates about primitivism centered around the examples of the people of Scotland as often as the American Indians. The rude ways of the Highlanders were often scorned, but their toughness also called forth a degree of admiration among "hard" primitivists, just that of the Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

ns and the Germans had done in antiquity. One Scottish writer described his Highland countrymen this way:

They greatly excel the Lowlanders in all the exercises that require agility; they are incredibly abstemious, and patient of hunger and fatigue; so steeled against the weather, that in traveling, even when the ground is covered with snow, they never look for a house, or any other shelter but their plaid, in which they wrap themselves up, and go to sleep under the cope of heaven. Such people, in quality of soldiers, must be invincible . . .

The reaction to Hobbes

Debates about "soft" and "hard" primitivism intensified with the publication in 1651 of Hobbes's LeviathanLeviathan

Leviathan , is a sea monster referred to in the Bible. In Demonology, Leviathan is one of the seven princes of Hell and its gatekeeper . The word has become synonymous with any large sea monster or creature...

(or Commonwealth), a justification of absolute monarchy. Hobbes, a "hard Primitivist", flatly asserted that life in a state of nature

State of nature

State of nature is a term in political philosophy used in social contract theories to describe the hypothetical condition that preceded governments...

was "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" -- a "war of all against all". Reacting to the wars of religion of his own time and the previous century, he maintained that the absolute rule of a king was the only possible alternative to the otherwise inevitable violence and anarchy of civil war. Hobbes' hard primitivism may have been as venerable as the tradition of soft primitivism, but his use of it was new. He used it to argue that the state was founded on a Social Contract

Social contract

The social contract is an intellectual device intended to explain the appropriate relationship between individuals and their governments. Social contract arguments assert that individuals unite into political societies by a process of mutual consent, agreeing to abide by common rules and accept...

in which men voluntarily gave up their liberty in return for the peace and security provided by total surrender to an absolute ruler, whose legitimacy stemmed from the Social Contract and not from God.

Hobbes' vision of the natural depravity of man inspired fervent disagreement among those who opposed absolute government. His most influential and effective opponent in the last decade of the 17th century was Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury was an English politician, philosopher and writer.-Biography:...

. Shaftesbury countered that, contrary to Hobbes, humans in a state of nature

State of nature

State of nature is a term in political philosophy used in social contract theories to describe the hypothetical condition that preceded governments...

were neither good nor bad, but that they possessed a moral sense based on the emotion of sympathy, and that this emotion was the source and foundation of human goodness and benevolence. Like his contemporaries (all of whom who were educated by reading classical authors such as Livy

Livy

Titus Livius — known as Livy in English — was a Roman historian who wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, "Chapters from the Foundation of the City," covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome well before the traditional foundation in 753 BC...

, Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

, and Horace

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus , known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus.-Life:...

), Shaftesbury admired the simplicity of life of classical antiquity. He urged a would-be author “to search for that simplicity of manners, and innocence of behavior, which has been often known among mere savages; ere they were corrupted by our commerce” (Advice to an Author, Part III.iii). Shaftesbury's denial of the innate depravity of man was taken up by contemporaries such as the popular Irish essayist Richard Steele

Richard Steele

Sir Richard Steele was an Irish writer and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine The Spectator....

(1672–1729), who attributed the corruption of contemporary manners to false education. Influenced by Shaftesbury and his followers, 18th-century readers, particularly in England, were swept up by the cult of Sensibility

Sensibility

Sensibility refers to an acute perception of or responsiveness toward something, such as the emotions of another. This concept emerged in eighteenth-century Britain, and was closely associated with studies of sense perception as the means through which knowledge is gathered...

that grew up around Shaftesbury's concepts of sympathy

Sympathy

Sympathy is a social affinity in which one person stands with another person, closely understanding his or her feelings. Also known as empathic concern, it is the feeling of compassion or concern for another, the wish to see them better off or happier. Although empathy and sympathy are often used...

and benevolence.

Meanwhile, in France, where those who criticized government or Church authority could be imprisoned without trial or hope of appeal, primitivism was used primarily as a way to protest the repressive rule of Louis XIV and XV, while avoiding censorship. Thus, in the beginning of the 18th century, a French travel writer, the Baron de Lahontan

Louis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan, Baron de Lahontan

Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan served in the French military in Canada where traveled extensively in the Wisconsin and Minnesota region and the upper Mississippi Valley. Upon his return to Europe he wrote an enormously popular travelogue. In it he embellished his knowledge of the geography of the...

, who had actually lived among the Huron Indians, put potentially dangerously radical Deist and egalitarian arguments in the mouth of a Canadian Indian, Adario, who was perhaps the most striking and significant figure of the "good" (or "noble") savage, as we understand it now, to make his appearance on the historical stage:

Adario sings the praises of Natural Religion. . . As against society he puts forward a sort of primitive Communism, of which the certain fruits are Justice and a happy life. . . . He looks with compassion on poor civilized man -- no courage, no strength, incapable of providing himself with food and shelter: a degenerate, a moral cretin, a figure of fun in his blue coat, his red hose, his black hat, his white plume and his green ribands. He never really lives because he is always torturing the life out of himself to clutch at wealth and honors which, even if he wins them, will prove to be but glittering illusions. . . . For science and the arts are but the parents of corruption. The Savage obeys the will of Nature, his kindly mother, therefore he is happy. It is civilized folk who are the real barbarians.Published in Holland, Lahontan's writings, with their controversial attacks on established religion and social customs, were immensely popular. Over twenty editions were issued between 1703 and 1741, including editions in French, English, Dutch and German.

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

and Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of James Cook, he took part in the French and Indian War and the unsuccessful French attempt to defend Canada from Britain...

seemed to open a glimpse into an unspoiled Edenic culture

Garden of Eden

The Garden of Eden is in the Bible's Book of Genesis as being the place where the first man, Adam, and his wife, Eve, lived after they were created by God. Literally, the Bible speaks about a garden in Eden...

that still existed in the un-Christianized

Christianization

The historical phenomenon of Christianization is the conversion of individuals to Christianity or the conversion of entire peoples at once...

South Seas

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

. Their popularity inspired Diderot's Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville

Supplément au voyage de Bougainville

Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, ou dialogue entre A et B sur l'inconvénient d'attacher des idées morales à certaines actions physiques qui n'en comportent pas. is a philosophical dialogue published in 1772, and written...

(1772), a scathing critique of European sexual hypocrisy and colonial exploitation.

By the end of the century, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

was poking fun at the fashionable craze for sentimentalized primitives in his Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America (1784), but the issue of colonialism

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

did not go away, and the device continued to be used to inspire compassion and to make philosophical and political points.

Two polemical French novels that heralded the start of Romanticism

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

in literature, promoting revolutionary liberal ideals along with new rebirth of religious enthusiasm, were Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre

Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre

Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre was a French writer and botanist...

's Paul et Virginie

Paul et Virginie

Paul et Virginie is a novel by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, first published in 1787. The novel's title characters are very good friends since birth who fall in love...

(1787), which takes place in Mauritius

Mauritius

Mauritius , officially the Republic of Mauritius is an island nation off the southeast coast of the African continent in the southwest Indian Ocean, about east of Madagascar...

and criticizes slavery; and Chateaubriand

François-René de Chateaubriand

François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand was a French writer, politician, diplomat and historian. He is considered the founder of Romanticism in French literature.-Early life and exile:...

's Atala

Atala

Atala may refer to:* Atala , an Italian manufacturer of bicycles* 152 Atala, an asteroid.* Eumaeus atala, a species of butterfly.* Atala , a novella by François-René de Chateaubriand...

(1807), in which saintly Nachez Indians of Mississippi are depicted as practicing a purified version of Christianity.

Erroneous identification of Rousseau with the noble savage

Jean-Jacques RousseauJean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of 18th-century Romanticism. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological and educational thought.His novel Émile: or, On Education is a treatise...

, like Shaftesbury, also insisted that man was born with the potential for goodness; and he, too, argued that civilization, with its envy and self-consciousness, has made men bad. However Rousseau never used the term "noble savage" and was not a primitivist.

The notion that Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality was essentially a glorification of the State of Nature, and that its influence tended to wholly or chiefly to promote "Primitivism" is one of the most persistent historical errors. – A. O. LovejoyArthur Oncken LovejoyArthur Oncken Lovejoy was an influential American philosopher and intellectual historian, who founded the field known as the history of ideas....

, “The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality” (1923).

Rousseau argued that in a state of nature

State of nature

State of nature is a term in political philosophy used in social contract theories to describe the hypothetical condition that preceded governments...

men are essentially animals, and that only by acting together in civil society and binding themselves to its laws do they become men. For Rousseau only a properly constituted society and reformed system of education could make men good. His fellow philosophe

Philosophe

The philosophes were the intellectuals of the 18th century Enlightenment. Few were primarily philosophers; rather they were public intellectuals who applied reason to the study of many areas of learning, including philosophy, history, science, politics, economics and social issues...

, Voltaire, who did not believe in equality, accused Rousseau of wanting to make people go back and walk on all fours.

Because Jean-Jacques Rousseau was the preferred philosopher of the radical Jacobin

Jacobin (politics)

A Jacobin , in the context of the French Revolution, was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary far-left political movement. The Jacobin Club was the most famous political club of the French Revolution. So called from the Dominican convent where they originally met, in the Rue St. Jacques ,...

s of the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

, he, above all, became tarred with the accusation of promoting the notion of the "noble savage", especially during the polemics about Imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

and scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

in the last half of the 19th century.

The 19th century: belief in progress and the fall of the natural man

During the 19th century the idea that men were everywhere and always the same that had characterized both classical antiquity and the EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

was exchanged for a more organic and dynamic evolutionary concept of human history. Advances in technology now made the indigenous man and his simpler way of life appear, not only inferior, but also, even his defenders agreed, foredoomed by the inexorable advance of progress

Social progress

Social progress is the idea that societies can or do improve in terms of their social, political, and economic structures. This may happen as a result of direct human action, as in social enterprise or through social activism, or as a natural part of sociocultural evolution...

to inevitable extinction. The sentimentalized "primitive" ceased to figure as a moral reproach to the decadence of the effete European, as in previous centuries. Instead, the argument shifted to a discussion of whether his demise should be considered a desirable or regrettable eventuality. As the century progressed, native peoples and their traditions increasingly became a foil serving to highlight the accomplishments of Europe and the expansion of the European Imperial powers, who justified their policies on the basis of a presumed racial and cultural superiority.

Charles Dickens 1853 article on "The Noble Savage" in Household Words

In 1853 Charles Dickens wrote a scathingly sarcastic review in his weekly magazine Household WordsHousehold Words

Household Words was an English weekly magazine edited by Charles Dickens in the 1850s which took its name from the line from Shakespeare "Familiar in his mouth as household words" — Henry V.-History:...

of painter George Catlin

George Catlin

George Catlin was an American painter, author and traveler who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the Old West.-Early years:...

's show of American Indians when it visited England. In his essay, entitled "The Noble Savage", Dickens expressed repugnance for Indians and their way of life in no uncertain terms, recommending that they ought to be "civilized out of existence". (Interestingly, Dickens's essay refers back to Dryden's well-known use of the term, not to Rousseau.) Dickens's scorn for those unnamed individuals, who, like Catlin, he alleged, misguidedly exalted the so-called "noble savage", was limitless. In reality, Dickens maintained, Indians were dirty, cruel, and constantly fighting among themselves. Dickens's satire on Catlin and others like him who might find something to admire in the American Indians or African bushmen is a notable turning point in the history of the use of the phrase.

Like others who would henceforth write about the topic, Dickens begins by disclaiming a belief in the "noble savage":

To come to the point at once, I beg to say that I have not the least belief in the Noble Savage. I consider him a prodigious nuisance and an enormous superstition. ... I don't care what he calls me. I call him a savage, and I call a savage a something highly desirable to be civilized off the face of the earth.... The noble savage sets a king to reign over him, to whom he submits his life and limbs without a murmur or question and whose whole life is passed chin deep in a lake of blood; but who, after killing incessantly, is in his turn killed by his relations and friends the moment a gray hair appears on his head. All the noble savage's wars with his fellow-savages (and he takes no pleasure in anything else) are wars of extermination – which is the best thing I know of him, and the most comfortable to my mind when I look at him. He has no moral feelings of any kind, sort, or description; and his "mission" may be summed up as simply diabolical.

Dickens' essay was arguably a pose of manly, no-nonsense realism and a defense of Christianity. At the end of it his tone becomes more recognizably humanitarian, as he maintains that, although the virtues of the savage are mythical and his way of life inferior and doomed, he still deserves to be treated no differently than if he were an Englishman of genius, such as Newton or Shakespeare:

To conclude as I began. My position is, that if we have anything to learn from the Noble Savage, it is what to avoid. His virtues are a fable; his happiness is a delusion; his nobility, nonsense. We have no greater justification for being cruel to the miserable object, than for being cruel to a WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE or an ISAAC NEWTON; but he passes away before an immeasurably better and higher power [i.e., that of Christianity] than ever ran wild in any earthly woods, and the world will be all the better when this place knows him no more.

Scapegoating the Eskimos: cannibalism and Franklin's lost expedition

Although Charles Dickens had ridiculed positive depictions of Native Americans as portrayals of so-called "noble" savages, he made an exception (at least initially) in the case of Eskimos, whom he called “loving children of the north”, “forever happy with their lot,” “whether they are hungry or full”, and “gentle loving savages”, who, despite a tendency to steal, have a “quiet, amiable character” ("Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise", Household Words, April 16, 1851). However he soon reversed this rosy assessment, when on October 23, 1854, The Times of London published a report by explorer-physician John RaeJohn Rae (explorer)

John Rae was a Scottish doctor who explored Northern Canada, surveyed parts of the Northwest Passage and reported the fate of the Franklin Expedition....

of the discovery by Eskimos of the remains of the lost Franklin expedition

Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a doomed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845. A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Franklin had served on three previous Arctic expeditions, the latter two as commanding officer...

along with unmistakable evidence of cannibalism among members of the party:

From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource -- cannibalism -- as a means of prolonging existence.

Franklin's widow and other surviving relatives and indeed the nation as a whole were shocked to the core and refused to accept these reports, which appeared to undermine the whole assumption of the cultural superiority of the heroic white explorer-scientist and the imperial project generally. Instead, they attacked the reliability of the Eskimos who had made the gruesome discovery and called them liars. An editorial in The Times called for further investigation:

to arrive at a more satisfactory conclusion with regard to the fate of poor Franklin and his friends . . . . Is the story told by the Esquimaux the true one? Like all savages they are liars, and certainly would not scruple at the utterance of any falsehood which might, in their opinion, shield them from the vengeance of the white man."

This line was energetically taken up by Dickens's, who wrote in his weekly magazine:

It is impossible to form an estimate of the character of any race of savages from their deferential behavior to the white man while he is strong. The mistake has been made again and again; and the moment the white man has appeared in the new aspect of being weaker than the savage, the savage has changed and sprung upon him. There are pious persons who, in their practice, with a strange inconsistency, claim for every child born to civilization all innate depravity, and for every child born to the woods and wilds all innate virtue. We believe every savage to be in his heart covetous, treacherous, and cruel; and we have yet to learn what knowledge the white man – lost, houseless, shipless, apparently forgotten by his race, plainly famine-stricken, weak frozen, helpless, and dying – has of the gentleness of the Esquimaux nature. --"The Lost Arctic Voyagers”, Household Words, December 2; 1854.

Dr. John Rae rebutted Dickens in two articles in Household Words: “The Lost Arctic Voyagers”, Household Words, No. 248 (December 23, 1854), and "Dr. Rae’s Report to the Secretary of the Admiralty", Household Words, No. 249 (December 30, 1854). Though he did not call them noble, Dr. Rae, who had lived among the Inuit, defended them as “dutiful” and “a bright example to the most civilized people”, comparing them favorably with the undisciplined crew of the Franklin expedition, whom he suggested were ill treated and "would have mutinied under privation", and moreover with the lower classes in England or Scotland generally. (Dr. Rae himself was Scots).

Rae's respect for the Inuit and his refusal to scapegoat them in the Franklin affair arguably harmed his career. Lady Franklin's campaign to glorify the dead of her husband's expedition, aided and abetted by Dickens, resulted in his being more or less shunned by the British establishment. Although it was not Franklin but Rae who in 1848 discovered the last link in the much-sought-after Northwest Passage, Rae was never awarded a knighthood and died in obscurity in London. (In comparison fellow Scot and contemporary explorer David Livingstone was knighted and buried with full imperial honors in Westminster Abbey). However, modern historians have confirmed Rae's discovery of the Northwest Passage and the accuracy of his report on cannibalism among Franklin's crew. Canadian author Ken McGoogan

Ken McGoogan

Ken McGoogan is the Canadian author of eight books, including four biographies focusing on northern exploration and published internationally: Fatal Passage , Ancient Mariner , Lady Franklin's Revenge , and Race to the Polar Sea .Born in Montreal and raised in a francophone town, McGoogan has...

, a specialist on Arctic exploration, states that Rae's willingness to learn and adopt the ways of indigenous Arctic peoples made him stand out as the foremost specialist of his time in cold-climate survival and travel. Rae's respect for Inuit customs, traditions, and skills was contrary to the prejudiced belief of many 19th-century Europeans that native peoples had no valuable technical knowledge or information to impart.

Dickens's racism, like that of many Englishmen, became markedly worse after the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 in India. This event, and the virtually contemporaneous occurrence of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

(1861–64), which threatened to, and then did, put an end to slavery, coincided with a polarization of attitudes exemplified by the phenomenon of scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

.

Scientific racism

In 1860, two British white supremacists, John Crawfurd and James Hunt mounted a defense of British imperialismImperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

based on “scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

". Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, took over the presidency of the Ethnological Society of London, which, as a branch of the Aborigines' Protection Society, had been founded with the mission to defend indigenous peoples against slavery and colonial exploitation. Invoking "science" and "realism", the two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing that mankind was divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity.'" For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Crawfurd was Scots, and thought the Scots "race" superior to all others; whilst Hunt, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon "race". Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau’s Noble Savage". The pair ultimately quarreled because Hunt believed in slavery and Crawfurd did not. "As Ter Ellingson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau.”

"If Rousseau was not the inventor of the Noble Savage, who was?" writes Ellingson,

One who turns for help to [Hoxie Neale] Fairchild's 1928 study, a compendium of citations from romantic writings on the "savage" may be surprised to find [his book] The Noble Savage almost completely lacking in references to its nominal subject. That is, although Fairchild assembles hundreds of quotations from ethnographers, philosophers, novelists, poets, and playwrights from the 17th century to the 19th century, showing a rich variety of ways in which writers romanticized and idealized those who Europeans considered "savages", almost none of them explicitly refer to something called the "Noble Savage". Although the words, always duly capitalized, appear on nearly every page, it turns out that in every instance, with four possible exceptions, they are Fairchild's words and not those of the authors cited.

Ellingson finds that any remotely positive portrayal of an indigenous (or working class) person is apt to be characterized (out of context) as a supposedly "unrealistic" or "romanticized" "Noble Savage". He points out that Fairchild even includes as an example of a supposed "Noble Savage", a picture of a Negro slave on his knees, lamenting lost his freedom. According to Ellingson, Fairchild ends his book with a denunciation of the (always un-named) believers in primitivism or "The Noble Savage" -- whom he feels are threatening to unleash the dark forces of irrationality on civilization.

Ellingson argues that the term "noble savage", an oxymoron, is a derogatory one, which those who oppose "soft" or romantic primitivism use to discredit (and intimidate) their supposed opponents, whose romantic beliefs they feel are somehow threatening to civilization. Ellingson maintains that virtually none of those accused of believing in the "noble savage" ever actually did so. He likens the practice of accusing anthropologists (and other writers and artists) of belief in the noble savage to a secularized version of the inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

, and he maintains that modern anthropologists have internalized these accusations to the point where they feel they have to begin by ritualistically disavowing any belief in "noble savage" if they wish to attain credibility in their fields. He notes that text books with a painting of a handsome Native American (such as the one one by Benjamin West on this page) are even given to school children with the cautionary caption, "A painting of a Noble Savage".

Opponents of primitivism

The most famous modern example of "hard" (or anti-) primitivism in books and movies was William GoldingWilliam Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding was a British novelist, poet, playwright and Nobel Prize for Literature laureate, best known for his novel Lord of the Flies...

's Lord of the Flies

Lord of the Flies

Lord of the Flies is a novel by Nobel Prize-winning author William Golding about a group of British boys stuck on a deserted island who try to govern themselves, with disastrous results...

, published in 1954. The title is said to be a reference to the Biblical devil, Beelzebub. This book, in which a group of school boys stranded on a desert island "revert" to savage behavior, was a staple of high school and college required reading lists during the Cold War.

In the 1960s, film director Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick was an American film director, writer, producer, and photographer who lived in England during most of the last four decades of his career...

professed his opposition to primitivism. Like Dickens, he began with a disclaimer:

Man isn't a noble savage, he's an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved — that about sums it up. I'm interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it's a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.

The opening scene of Kubrick's movie 2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey (film)

2001: A Space Odyssey is a 1968 epic science fiction film produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick, and co-written by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, partially inspired by Clarke's short story The Sentinel...

(1968) depicted prehistoric ape-like men wielding weapons of war, as the tools that supposedly lifted them out of their animal state and made them human.

Another opponent of primitivism is the Australian anthropologist Roger Sandall

Roger Sandall

Roger Sandall is an essayist and commentator on cultural relativism and is best known as the author of The Culture Cult. He was born in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 1933 but has spent most of his career in Australia...

, who has accused other anthropologists of exalting the "noble savage". A third is archeologist Lawrence H. Keeley, who has criticised a "widespread myth" that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple primeval happiness, a peaceful golden age" by uncovering archeological evidence that he claims demonstrates that violence prevailed in the earliest human societies. Keeley argues that the "noble savage" paradigm has warped anthropological literature to political ends.

See also

- Essays (Montaigne)Essays (Montaigne)Essays is the title given to a collection of 107 essays written by Michel de Montaigne that was first published in 1580. Montaigne essentially invented the literary form of essay, a short subjective treatment of a given topic, of which the book contains a large number...

- Jean-Jacques RousseauJean-Jacques RousseauJean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of 18th-century Romanticism. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological and educational thought.His novel Émile: or, On Education is a treatise...

- Wild childWild Child"Wild Child" is a 2001 single by Irish singer Enya. The song "Midnight Blue" has only been released on this single. The single was only available on CD in Germany, Japan and Korea. It was available on cassette in the UK...

- Wild manWild manThe wild man is a mythical figure that appears in the artwork and literature of medieval Europe, comparable to the satyr or faun type in classical mythology and to Silvanus, the Roman god of the woodlands.The defining characteristic of the figure is its "wildness"; from the 12th century...

- Anarcho-primitivismAnarcho-primitivismAnarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of the origins and progress of civilization. According to anarcho-primitivism, the shift from hunter-gatherer to agricultural subsistence gave rise to social stratification, coercion, and alienation...

- Neotribalism

- Romantic racismRomantic racismRomantic racism is a form of racism in which members of a dominant group purportedly project their fantasies onto members of oppressed groups. Feminist scholars have accused Norman Mailer, Jack Kerouac, and other Beatnik authors of the 1950s of romantic racism...

Concepts:

- Cultural relativismCultural relativismCultural relativism is the principle that an individual human's beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual's own culture. This principle was established as axiomatic in anthropological research by Franz Boas in the first few decades of the 20th century and...

- Golden AgeGolden AgeThe term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology and legend and refers to the first in a sequence of four or five Ages of Man, in which the Golden Age is first, followed in sequence, by the Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and then the present, a period of decline...

- Master-slave dialecticMaster-slave dialecticThe Master-Slave dialectic is a famous passage of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. It is widely considered a key element in Hegel's philosophical system, and has heavily influenced many subsequent philosophers...

- Social progressSocial progressSocial progress is the idea that societies can or do improve in terms of their social, political, and economic structures. This may happen as a result of direct human action, as in social enterprise or through social activism, or as a natural part of sociocultural evolution...

- State of natureState of natureState of nature is a term in political philosophy used in social contract theories to describe the hypothetical condition that preceded governments...

- XenocentrismXenocentrismXenocentrism is a political neologism, coined as the antonym of ethnocentrism. Xenocentrism is the preference for the products, styles, or ideas of someone else's culture rather than of one's own...

Cultural examples:

- Magical negroMagical negroThe Magical Negro, or magical African-American friend, is a supporting stock character in American cinema, who, by use of special insight or powers, helps the white protagonist....

- A High Wind in Jamaica (novel)

- Lord of the FliesLord of the FliesLord of the Flies is a novel by Nobel Prize-winning author William Golding about a group of British boys stuck on a deserted island who try to govern themselves, with disastrous results...

- The Blue Lagoon (novel)The Blue Lagoon (novel)The Blue Lagoon is a romance novel by Henry De Vere Stacpoole, first published in 1908. The novel is the first of the Blue Lagoon trilogy, the second being The Garden of God and the third being The Gates of Morning ....

Further reading

- Barnett, Louise. Touched by Fire: the Life, Death, and Mythic Afterlife of George Armstrong Custer. University of Nebraska Press [1986], 2006.

- Barzun, JacquesJacques BarzunJacques Martin Barzun is a French-born American historian of ideas and culture. He has written on a wide range of topics, but is perhaps best known as a philosopher of education, his Teacher in America being a strong influence on post-WWII training of schoolteachers in the United...

(2000). From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 282–294, and passim. - Bataille, Gretchen, M. and Silet Charles L., editors. Introduction by Vine Deloria, Jr. The Pretend Indian: Images of Native Americans in the Movies. Iowa State University Press, 1980*Berkhofer, Robert F. "The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present"

- Boas, George ([1933] 1966). The Happy Beast in French Thought in the Seventeenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Press in 1966.

- Boas, George ([1948] 1997). Primitivism and Related Ideas in the Middle Ages. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. "Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century"

- Bury, J.B. (1920). The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth. (Reprint) New York: Cosimo Press, 2008.

- Edgerton, Robert (1992). Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0029089255

- Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. (2008) "'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture". Website: Our Legacy. Material relating to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit peoples, found in Saskatchewan cultural and heritage collections.

- Ellingson, Ter. (2001). The Myth of the Noble Savage (Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press).

- Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object

- Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1928). The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism (New York)

- Fitzgerald, Margaret Mary ([1947] 1976). First Follow Nature: Primitivism in English Poetry 1725-1750. New York: Kings Crown Press. Reprinted New York: Octagon Press.

- Fryd, Vivien Green (1995). "Rereading the Indian in Benjamin West's 'Death of General Wolfe.'" American Art, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Spring, 1995), pp. 72–85.

- Hazard, PaulPaul HazardPaul Gustave Marie Camille Hazard , was a French scholar, professor and historian of ideas.-Biography:...

([1937]1947). The European Mind (1690-1715). Cleveland, Ohio: Meridian Books. - Keeley, Lawrence H. (1996) War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage. Oxford: University Press.

- Krech, Shepard (2000). The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0393321005

- LeBlanc, Steven (2003). Constant battles: the myth of the peaceful, noble savage. New York : St Martin's Press ISBN 0312310897

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. (1923, 1943). “The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality, ” Modern Philology Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165-186. Reprinted in Essays in the History of Ideas. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948 and 1960.

- A. O. Lovejoy and George Boas ([1935] 1965). Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Books, 1965. ISBN 0374951306

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. and George Boas. (1935). A Documentary History of Primitivism and Related Ideas, vol. 1. Baltimore.

- Moore, Grace (2004). Dickens And Empire: Discourses Of Class, Race And Colonialism In The Works Of Charles Dickens (Nineteenth Century Series). Ashgate.

- Olupọna, Jacob Obafẹmi Kẹhinde, Editor. (2003) Beyond primitivism: indigenous religious traditions and modernity. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0415273196, 9780415273190

- Pagden, AnthonyAnthony PagdenAnthony Robin Dermer Pagden is an author and distinguished professor of political science and history at the University of California, Los Angeles.-Biography:...

(1982). The Fall of the Natural Man: The American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Pinker, StevenSteven PinkerSteven Arthur Pinker is a Canadian-American experimental psychologist, cognitive scientist, linguist and popular science author...

(2002). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human NatureThe Blank SlateThe Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature is a best-selling 2002 book by Steven Pinker arguing against tabula rasa models of the social sciences. Pinker argues that human behavior is substantially shaped by evolutionary psychological adaptations...

. Viking ISBN 0-670-03151-8 - Sandall, RogerRoger SandallRoger Sandall is an essayist and commentator on cultural relativism and is best known as the author of The Culture Cult. He was born in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 1933 but has spent most of his career in Australia...

(2001). The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other Essays ISBN 0-8133-3863-8 - Reinhardt, Leslie Kaye. "British and Indian Identities in a Picture by Benjamin West". Eighteenth-Century Studies 31: 3 (Spring 1998): 283-30

- Rollins, Peter C. and John E. O'Connor, editors (1998). Hollywood's Indian : the Portrayal of the Native American in Film. Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press.

- Tinker, Chaunchy Brewster (1922). Nature's Simple Plan: a phase of radical thought in the mid-eighteenth century. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Torgovnick, Marianna (1991). Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives (Chicago)

- Whitney, Lois Payne (1934). Primitivism and the Idea of Progress in English Popular Literature of the Eighteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press

- Eric R. Wolf (1982). Europe and the People without History. Berkeley: University of California Press.