Olympic Games scandals and controversies

Encyclopedia

The Olympic Games

is a major international multi-sport event

. During its history, both the Summer

and Winter Games

were a subject of many scandals and controversies.

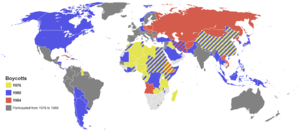

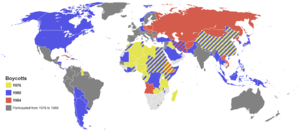

Some states boycott

ed the Games on various occasions, often as a sign of protest against the International Olympic Committee

or contemporary politics of other paticipants. After both World Wars, the losing countries were not invited. Other controversies include decisions by referee

s and even gesture

s made by athletes.

1908 Summer Olympics

1912 Summer Olympics

1916 Summer Olympics

1920 Summer Olympics

1932 Summer Olympics

1936 Summer Olympics

1940

1948 Summer Olympics

1956 Summer Olympics

1964 Summer Olympics

1968 Summer Olympics

1972 Summer Olympics

1976 Summer Olympics

1980 Summer Olympics

1984 Summer Olympics

1988 Summer Olympics

2000 Summer Olympics

2004 Summer Olympics

2008 Summer Olympics

1968 Winter Olympics

1972 Winter Olympics

1980 Winter Olympics

1994 Winter Olympics

1998 Winter Olympics

2002 Winter Olympics

2006 Winter Olympics

2010 Winter Olympics

The controversy includes such issues as: should a simpler routine have been awarded gold over programs that included a quadruple-triple combination, collusion in the judging process, and whether or not the most difficult jump is recognized enough as such in the current ISU judging system.

2014 Winter Olympics

Olympic Games

The Olympic Games is a major international event featuring summer and winter sports, in which thousands of athletes participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world’s foremost sports competition where more than 200 nations participate...

is a major international multi-sport event

Multi-sport event

A multi-sport event is an organized sporting event, often held over multiple days, featuring competition in many different sports between organized teams of athletes from nation-states. The first major, modern, multi-sport event of international significance was the modern Olympic Games.Many...

. During its history, both the Summer

Summer Olympic Games

The Summer Olympic Games or the Games of the Olympiad are an international multi-sport event, occurring every four years, organized by the International Olympic Committee. Medals are awarded in each event, with gold medals for first place, silver for second and bronze for third, a tradition that...

and Winter Games

Winter Olympic Games

The Winter Olympic Games is a sporting event, which occurs every four years. The first celebration of the Winter Olympics was held in Chamonix, France, in 1924. The original sports were alpine and cross-country skiing, figure skating, ice hockey, Nordic combined, ski jumping and speed skating...

were a subject of many scandals and controversies.

Some states boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

ed the Games on various occasions, often as a sign of protest against the International Olympic Committee

International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee is an international corporation based in Lausanne, Switzerland, created by Pierre de Coubertin on 23 June 1894 with Demetrios Vikelas as its first president...

or contemporary politics of other paticipants. After both World Wars, the losing countries were not invited. Other controversies include decisions by referee

Referee

A referee is the person of authority, in a variety of sports, who is responsible for presiding over the game from a neutral point of view and making on the fly decisions that enforce the rules of the sport...

s and even gesture

Gesture

A gesture is a form of non-verbal communication in which visible bodily actions communicate particular messages, either in place of speech or together and in parallel with spoken words. Gestures include movement of the hands, face, or other parts of the body...

s made by athletes.

1908 Summer Olympics1908 Summer OlympicsThe 1908 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the IV Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event which was held in 1908 in London, England, United Kingdom. These games were originally scheduled to be held in Rome. At the time they were the fifth modern Olympic games...

- Grand Duchy of FinlandGrand Duchy of FinlandThe Grand Duchy of Finland was the predecessor state of modern Finland. It existed 1809–1917 as part of the Russian Empire and was ruled by the Russian czar as Grand Prince.- History :...

competed separately from the Russian EmpireRussian EmpireThe Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, but was not allowed to display the Finnish flag. Similary, Ireland participated separately from Great BritainGreat BritainGreat Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

in field hockeyField hockey at the 1908 Summer OlympicsAt the 1908 Summer Olympics, a field hockey tournament was contested for the first time. Six teams entered from three states. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was represented by a team from each of the four home nations: England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales...

and poloPolo at the 1908 Summer OlympicsAt the 1908 Summer Olympics, a polo tournament was contested. It was the second time the sport had been featured at the Olympics, with 1900 being its first appearance....

, but also without its own flag.

- In the 400 metres, American winner John Carpenter, was disqualified for blocking British athlete Wyndham HalswelleWyndham HalswelleWyndham Halswelle was a British athlete, winner of the controversial 400m race at the 1908 Summer Olympics, becoming the only athlete to win an Olympic title by a walkover....

in a maneuver that was legal under U.S. rules but prohibited by the British rules under which the race was run. As a result of the disqualification, a second final race was ordered. Halswelle was to face the other two finalists William RobbinsWilliam Robbins (athlete)William Robbins was an American athlete and a member of the Irish American Athletic Club.He was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts....

and John TaylorJohn Taylor (athlete)John Baxter Taylor Jr. was an American track and field athlete, notable as the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal...

, but both were from the United States and decided not to contest the repeat of the final to protest the judges' decision. Halswelle was thus the only medallist in the 400 metres. It was the only walkover victory in Olympic history. Taylor later ran on the Gold medal winning U.S. team for the now-defunct Medley Relay, becoming the first African AmericanAfrican AmericanAfrican Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

medalist.

1912 Summer Olympics1912 Summer OlympicsThe 1912 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the V Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event held in Stockholm, Sweden, between 5 May and 27 July 1912. Twenty-eight nations and 2,407 competitors, including 48 women, competed in 102 events in 14 sports...

- American athlete Jim ThorpeJim ThorpeJacobus Franciscus "Jim" Thorpe * Gerasimo and Whiteley. pg. 28 * americaslibrary.gov, accessed April 23, 2007. was an American athlete of mixed ancestry...

was stripped of his gold medals in the decathlonDecathlonThe decathlon is a combined event in athletics consisting of ten track and field events. The word decathlon is of Greek origin . Events are held over two consecutive days and the winners are determined by the combined performance in all. Performance is judged on a points system in each event, not...

and pentathlonPentathlonA pentathlon is a contest featuring five different events. The name is derived from Greek: combining the words pente and -athlon . The first pentathlon was documented in Ancient Greece and was part of the Ancient Olympic Games...

after it was learned that he had played professional minor league baseball three years earlier. In solidarity, the decathlon silver medalist, Hugo WieslanderHugo WieslanderKarl Hugo Wieslander was a Swedish athlete, who competed in combined events. He set the inaugural world record in the pentathlon in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1911 with a score of 5516 points. He was born in Ljuder....

, refused to accept the medals when they were offered to him. The gold medals were restored to Thorpe's children in 1983, thirty years after his death.

1916 Summer Olympics1916 Summer OlympicsThe anticipated 1916 Summer Olympics, which were to be officially known as the Games of the VI Olympiad, were to have been held in Berlin, Germany. However, due to the outbreak of World War I, the games were cancelled.-History:...

- The 1916 Summer Olympics were to have been held in BerlinBerlinBerlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, German EmpireGerman EmpireThe German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, but were cancelled because of the outbreak of World War IWorld War IWorld War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

.

1920 Summer Olympics1920 Summer OlympicsThe 1920 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the VII Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event in 1920 in Antwerp, Belgium....

- BudapestBudapestBudapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

had initially been selected over AmsterdamAmsterdamAmsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

and LyonLyonLyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

to host the Games, but as the Austro-Hungarian Empire had been a German ally in World War I, the French-dominated International Olympic CommitteeInternational Olympic CommitteeThe International Olympic Committee is an international corporation based in Lausanne, Switzerland, created by Pierre de Coubertin on 23 June 1894 with Demetrios Vikelas as its first president...

transferred the Games to Antwerp in April 1919.

- AustriaAustriaAustria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, BulgariaBulgariaBulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

, GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, HungaryHungaryHungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, and TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

were not invited to the Games, being the successor statesSuccession of statesSuccession of states is a theory and practice in international relations regarding the recognition and acceptance of a newly created sovereign state by other states, based on a perceived historical relationship the new state has with a prior state...

of the Central PowersCentral PowersThe Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

which lost World War I.

1932 Summer Olympics1932 Summer OlympicsThe 1932 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the X Olympiad, was a major world wide multi-athletic event which was celebrated in 1932 in Los Angeles, California, United States. No other cities made a bid to host these Olympics. Held during the worldwide Great Depression, many nations...

- Nine-time Finnish Olympic gold medalist Paavo NurmiPaavo NurmiPaavo Johannes Nurmi was a Finnish runner. Born in Turku, he was known as one of the "Flying Finns," a term given to him, Hannes Kolehmainen, Ville Ritola, and others for their distinction in running...

was found to be a professional athlete and barred from running in the Games. The main conductors of the ban were Swedish officials, especially Sigfrid EdströmSigfrid EdströmJohannes Sigfrid Edström was a Swedish industrialist, chairman of the Sweden-America Foundation, and an official with the International Olympic Committee.-Early life:...

, who claimed that Nurmi had received too much money for his travel expenses. However, Nurmi did travel to Los AngelesLos ÁngelesLos Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

and kept training at the Olympic Village. Despite pleas from all the entrants of the marathon, he was not allowed to compete at the Games. This incident, in part, led to Finland refusing to participate in the traditional Finland-Sweden athletics internationalFinland-Sweden athletics internationalFinnkampen , Suomi-Ruotsi-maaottelu or Ruotsi-ottelu , is a yearly athletics international competition held between Sweden and Finland since 1925.It is, since the late 1980s, the only annual athletics...

event until 1939.

- After winning the silver in equestrian dressage, Swedish equestrian Bertil SandströmBertil SandströmKarl Bertil Sandström was a Swedish horse rider who competed in the 1920 Summer Olympics, in the 1924 Summer Olympics, and in the 1932 Summer Olympics....

was demoted to last for clicking to his horse to win encouragement. He asserted that it was a creaking saddle making the sounds.

1936 Summer Olympics1936 Summer OlympicsThe 1936 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event which was held in 1936 in Berlin, Germany. Berlin won the bid to host the Games over Barcelona, Spain on April 26, 1931, at the 29th IOC Session in Barcelona...

- The 1936 Summer Olympics, held in Berlin, were controversial due to the Nazi regime that came to power after the city had been selected. Adolf HitlerAdolf HitlerAdolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

regarded it as his Olympics and he took them as a chance to show off the post-First World War Germany. In 1936, a number of prominent politicians and organizations called for a boycott of the Summer Olympics, which had been awarded to GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

before the Nazi regime came to power. The Popular FrontPopular Front (Spain)The Popular Front in Spain's Second Republic was an electoral coalition and pact signed in January 1936 by various left-wing political organisations, instigated by Manuel Azaña for the purpose of contesting that year's election....

government of Spain decided to boycott and organized the People's OlympiadPeople's OlympiadThe People's Olympiad was a planned international multi-sport event that was intended to take place in Barcelona, the capital of the autonomous region of Catalonia within the Spanish Republic...

as an alternative with labour and socialist groups around the world sending athletes to the effort. However the Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil WarThe Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

broke out just as the Games were about to begin.

- The United States considered boycotting the Games, but ultimately decided to participate. Nazi propaganda promoted concepts of "Aryan racial superiority"; however African-American athlete Jesse OwensJesse OwensJames Cleveland "Jesse" Owens was an American track and field athlete who specialized in the sprints and the long jump. He participated in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany, where he achieved international fame by winning four gold medals: one each in the 100 meters, the 200 meters, the...

, winner of four medals during the games, did not face segregation and discrimination in Germany that were normal in the United States at the time.

- French Olympians gave what appeared to be the Nazi saluteNazi saluteThe Nazi salute, or Hitler salute , was a gesture of greeting in Nazi Germany usually accompanied by saying, Heil Hitler! ["Hail Hitler!"], Heil, mein Führer ["Hail, my leader!"], or Sieg Heil! ["Hail victory!"]...

at the opening ceremony, although they may have been performing the Olympic salute, which is similar, as both are based on the Roman saluteRoman saluteThe Roman salute is a gesture in which the arm is held out forward straight, with palm down, and fingers touching. In some versions, the arm is raised upward at an angle; in others, it is held out parallel to the ground. The former is a well known symbol of fascism that is commonly perceived to be...

.

- The IOC expelled U.S. athlete Ernest Lee Jahnke, the son of a German immigrant, for encouraging athletes to boycott the Berlin Games. He was replaced by United States Olympic CommitteeUnited States Olympic CommitteeThe United States Olympic Committee is a non-profit organization that serves as the National Olympic Committee and National Paralympic Committee for the United States and coordinates the relationship between the United States Anti-Doping Agency and the World Anti-Doping Agency and various...

president Avery BrundageAvery BrundageAvery Brundage was an American amateur athlete, sports official, art collector, and philanthropist. Brundage competed in the 1912 Olympics and was the US national all-around athlete in 1914, 1916 and 1918...

, who supported the Games.

- In the cycling match sprint final, German Toni MerkensToni MerkensToni Merkens was a racing cyclist from Germany and Olympic champion. He represented his native country at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, where he received the gold medal in the men's 1000 meter match sprint event.-Racing career:Merkens trained as a bicycle mechanic with Fritz Köthke...

fouled Dutchman Arie van VlietArie van VlietArie van Vliet was a Dutch racing cyclist, olympic champion in track cycling.He received a gold medal in 1000 m time trial and a silver medal in individual sprint at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.-References:...

. Instead of disqualification, Merkens was fined 100 ReichsmarksGerman reichsmarkThe Reichsmark was the currency in Germany from 1924 until June 20, 1948. The Reichsmark was subdivided into 100 Reichspfennig.-History:...

and kept the gold medal.

- United States sprinters Sam StollerSam StollerSam Stoller was an American sprinter and long jumper who tied the world record in the 60-yard dash in 1936. He is best known for his exclusion from the American 4 × 100 relay team at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, triggering widespread speculation that he and Marty Glickman,...

and Marty GlickmanMarty GlickmanMartin "Marty" Glickman was a Jewish American track and field athlete and sports announcer, born in The Bronx, New York. His parents, Harry and Molly Glickmann, immigrated to the United States from Jassy, Romania....

, the only two Jewish athletes on the U.S. Olympic team, were pulled from the 4 × 100 relay team on the day of the competition, leading to accusations of anti-Semitism on the part of the United States Olympic CommitteeUnited States Olympic CommitteeThe United States Olympic Committee is a non-profit organization that serves as the National Olympic Committee and National Paralympic Committee for the United States and coordinates the relationship between the United States Anti-Doping Agency and the World Anti-Doping Agency and various...

.

19401940 Summer OlympicsThe anticipated 1940 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XII Olympiad and originally scheduled to be held from September 21 to October 6, 1940, in Tokyo, Japan, were cancelled due to the outbreak of World War II...

and 1944 Summer Olympics1944 Summer OlympicsThe anticipated 1944 Summer Olympics, which were to be officially known as the Games of the XIII Olympiad, were cancelled due to World War II...

- The 1940 Summer Olympics were scheduled to be held in TokyoTokyo, ; officially , is one of the 47 prefectures of Japan. Tokyo is the capital of Japan, the center of the Greater Tokyo Area, and the largest metropolitan area of Japan. It is the seat of the Japanese government and the Imperial Palace, and the home of the Japanese Imperial Family...

, JapanEmpire of JapanThe Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

, but were cancelled due to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese WarSecond Sino-Japanese WarThe Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

. The government of JapanEmpire of JapanThe Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

had abandoned its support for the 1940 Games in July 1938. The IOC then awarded the Games to HelsinkiHelsinkiHelsinki is the capital and largest city in Finland. It is in the region of Uusimaa, located in southern Finland, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, an arm of the Baltic Sea. The population of the city of Helsinki is , making it by far the most populous municipality in Finland. Helsinki is...

, FinlandFinlandFinland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, the runner-up in the original bidding process, but the Games were not held due to the Winter WarWinter WarThe Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet offensive on 30 November 1939 – three months after the start of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland – and ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow Peace Treaty...

. Ultimately, the Olympic Games were suspended indefinitely following the outbreak of World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

and did not resume until the LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

Games of 19481948 Summer OlympicsThe 1948 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XIV Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event which was held in London, England, United Kingdom. After a 12-year hiatus because of World War II, these were the first Summer Olympics since the 1936 Games in Berlin...

.

1948 Summer Olympics1948 Summer OlympicsThe 1948 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XIV Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event which was held in London, England, United Kingdom. After a 12-year hiatus because of World War II, these were the first Summer Olympics since the 1936 Games in Berlin...

- The two major Axis powersAxis PowersThe Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

of World War II, Germany and Japan, were not invited to the Games.

- The Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

was invited but chose not to send any athletes.

1956 Summer Olympics1956 Summer OlympicsThe 1956 Melbourne Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XVI Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event which was held in Melbourne, Australia, in 1956, with the exception of the equestrian events, which could not be held in Australia due to quarantine regulations...

- Seven countries boycotted the Games for three different reasons. EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, IraqIraqIraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

, and LebanonLebanonLebanon , officially the Republic of LebanonRepublic of Lebanon is the most common term used by Lebanese government agencies. The term Lebanese Republic, a literal translation of the official Arabic and French names that is not used in today's world. Arabic is the most common language spoken among...

announced that they would not participate in response to the Suez CrisisSuez CrisisThe Suez Crisis, also referred to as the Tripartite Aggression, Suez War was an offensive war fought by France, the United Kingdom, and Israel against Egypt beginning on 29 October 1956. Less than a day after Israel invaded Egypt, Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to Egypt and Israel,...

when EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

was invaded by IsraelIsraelThe State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

, the United KingdomUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, and FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

after Egypt nationalized the Suez canalSuez CanalThe Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

. The NetherlandsNetherlandsThe Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, SpainSpainSpain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, and SwitzerlandSwitzerlandSwitzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

withdrew to protest the Soviet Union's invasion of HungaryHungaryHungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution1956 Hungarian RevolutionThe Hungarian Revolution or Uprising of 1956 was a spontaneous nationwide revolt against the government of the People's Republic of Hungary and its Soviet-imposed policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956....

and the Soviet presence at the Games. Less than two weeks before the opening ceremony, the People's Republic of ChinaPeople's Republic of ChinaChina , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

also chose to boycott the event, protesting the Republic of ChinaRepublic of ChinaThe Republic of China , commonly known as Taiwan , is a unitary sovereign state located in East Asia. Originally based in mainland China, the Republic of China currently governs the island of Taiwan , which forms over 99% of its current territory, as well as Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor...

(Taiwan) being allowed to compete (under the name "FormosaTaiwanTaiwan , also known, especially in the past, as Formosa , is the largest island of the same-named island group of East Asia in the western Pacific Ocean and located off the southeastern coast of mainland China. The island forms over 99% of the current territory of the Republic of China following...

").

- The political frustrations between the Soviet Union and Hungary boiled over at the games themselves when the two men's water poloWater poloWater polo is a team water sport. The playing team consists of six field players and one goalkeeper. The winner of the game is the team that scores more goals. Game play involves swimming, treading water , players passing the ball while being defended by opponents, and scoring by throwing into a...

teams met for the semi-final. The players became increasingly violent towards one another as the game progressed, while many Hungarian spectators were prevented from rioting only by the sudden appearance of the police. The match became known as the Blood in the Water matchBlood In The Water matchThe "Blood in the Water" match was a water polo match between Hungary and the USSR at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. The match, which took place on December 6, 1956, was against the background of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and saw Hungary defeat the USSR 4–0...

.

1964 Summer Olympics1964 Summer OlympicsThe 1964 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XVIII Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event held in Tokyo, Japan in 1964. Tokyo had been awarded with the organization of the 1940 Summer Olympics, but this honor was subsequently passed to Helsinki because of Japan's...

- IndonesiaIndonesiaIndonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

and North KoreaNorth KoreaThe Democratic People’s Republic of Korea , , is a country in East Asia, occupying the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Its capital and largest city is Pyongyang. The Korean Demilitarized Zone serves as the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea...

withdrew after the IOC decision to ban teams that took part in the 1963 Games of the New Emerging ForcesGANEFOThe Games of the New Emerging Forces were the games set up by Indonesia in late 1962 as a counter to the Olympic Games. Established for the athletes of the so-called "emerging nations" , GANEFO made it clear in its constitution that politics and sport were intertwined; this ran against the...

.

- South AfricaSouth Africa at the OlympicsSouth Africa first participated at the Olympic Games in 1904, and sent athletes to compete in every Summer Olympic Games until 1960. After the passage of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1761 in 1962 in response to South Africa's policy of apartheid, the nation was barred from the Games....

was expelled from the Olympics due to apartheid. It would not be invited again until 1992.

1968 Summer Olympics1968 Summer OlympicsThe 1968 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XIX Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event held in Mexico City, Mexico in October 1968. The 1968 Games were the first Olympic Games hosted by a developing country, and the first Games hosted by a Spanish-speaking country...

- 1968 Olympics Black Power salute1968 Olympics Black Power saluteThe 1968 Olympics Black Power salute involved the African American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos giving the Black power salute at the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City...

: Tommie SmithTommie SmithTommie Smith is an African American former track & field athlete and wide receiver in the American Football League. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, Smith won the 200-meter dash finals in 19.83 seconds – the first time the 20 second barrier was broken...

and John CarlosJohn CarlosJohn Wesley Carlos is a Cuban American former track and field athlete and professional football player. He was the bronze-medal winner in the 200 meters at the 1968 Summer Olympics and his black power salute on the podium with Tommie Smith caused much political controversy...

, two African-American athletes who finished the 200 meter raceAthletics at the 1968 Summer OlympicsAt the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, 36 athletics events were contested, 24 for men and 12 for women. There were a total number of 1031 participating athletes from 93 countries....

first and third respectively, performed the "Power to the People" salute during the national anthem of the United States.

- Students in Mexico City tried to make use of the media attention for their country to protest the authoritarian Mexican government. The government reacted with violence, culminating in the Tlatelolco MassacreTlatelolco massacreThe Tlatelolco massacre, also known as The Night of Tlatelolco , was a government massacre of student and civilian protesters and bystanders that took place during the afternoon and night of October 2, 1968, in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City...

ten days before the Games began and more than two hundred protesters were shot by government forces.

1972 Summer Olympics1972 Summer OlympicsThe 1972 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XX Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event held in Munich, West Germany, from August 26 to September 11, 1972....

- The Munich massacreMunich massacreThe Munich massacre is an informal name for events that occurred during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Bavaria in southern West Germany, when members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken hostage and eventually killed by the Palestinian group Black September. Members of Black September...

occurred during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, West Germany, when members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken hostage by the Palestinian terrorist group Black SeptemberBlack September (group)The Black September Organization was a Palestinian paramilitary group, founded in 1970. It was responsible for the kidnapping and murder of eleven Israeli athletes and officials, and fatal shooting of a West German policeman, during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, their most publicized event...

which had ties to Yasser ArafatYasser ArafatMohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa al-Husseini , popularly known as Yasser Arafat or by his kunya Abu Ammar , was a Palestinian leader and a Laureate of the Nobel Prize. He was Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization , President of the Palestinian National Authority...

’s FatahFatahFataḥ is a major Palestinian political party and the largest faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization , a multi-party confederation. In Palestinian politics it is on the left-wing of the spectrum; it is mainly nationalist, although not predominantly socialist. Its official goals are found...

organization. Eleven athletes were murdered by the terrorists.

- In the controversial gold medal basketball game, the USA Olympic Basketball team battled for the gold medal for the last few seconds against the team from the Soviet Union. With three seconds left and the US team leading the Soviets by one point, a Soviet attempt to run an inbounds play was aborted when their coaching staff interrupted game officials to argue that the team was due a timeout. Another play was run, which failed to score and sent the U.S. team into jubilant celebration over their apparent victory. But the play was ruled invalid because the game clock had not been properly reset when the ball was inbounded. The clock was reset and a third play was run, on which the USSR scored a layup to win, 51-50. Infuriated by the actions of the officials, the U.S. team refused to accept the silver medals.

- At the end of the MarathonMarathonThe marathon is a long-distance running event with an official distance of 42.195 kilometres , that is usually run as a road race...

, a German impostor entered the stadium to the cheers of the stadium ahead of the actual winner, Frank ShorterFrank ShorterFrank Charles Shorter is a former American long-distance runner who won the gold medal in the marathon at the 1972 Summer Olympics. His victory is credited with igniting the running boom in the United States of the 1970s....

of the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. During the ABCAmerican Broadcasting CompanyThe American Broadcasting Company is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948...

coverage of the event, the guest commentator, writer Erich SegalErich SegalErich Wolf Segal was an American author, screenwriter, and educator. He was best-known for writing the novel Love Story , a best-seller, and writing the motion picture of the same name, which was a major hit....

famously called to Shorter "It's a fraud, Frank."

- In the men's field hockey final Michael Krause's goal in the 60th minute gave the host West Germans a 1-0 victory in the final over the defending champion Pakistanis. Pakistan's players complained about some of the umpiring and disagreed that Krause's goal was good. After the game, Pakistani fans ran onto the field in rage; some players and fans dumped water on Belgium's Rene Frank, then the head of the sport's international governing body. During the medals ceremony, the players staged their protest, some of them turning their backs to the West German flag. Reports also mention that the Pakistani players handled their silver medals disrespectfully. According to the story in The Washington Post, the team's manager, G.R. Chaudhry, said that his team thought the outcome had been "pre-planned" by the officials, Horacio Servetto of Argentina and Richard Jewell of Australia.

1976 Summer Olympics1976 Summer OlympicsThe 1976 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXI Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event celebrated in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, in 1976. Montreal was awarded the rights to the 1976 Games on May 12, 1970, at the 69th IOC Session in Amsterdam, over the bids of Moscow and...

- In protest against the New ZealandNew ZealandNew Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

rugby unionRugby unionRugby union, often simply referred to as rugby, is a full contact team sport which originated in England in the early 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand...

team's tour of South AfricaSouth AfricaThe Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

, TanzaniaTanzaniaThe United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

led a boycott of twenty-two AfricaAfricaAfrica is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

n nations after the International Olympic CommitteeInternational Olympic CommitteeThe International Olympic Committee is an international corporation based in Lausanne, Switzerland, created by Pierre de Coubertin on 23 June 1894 with Demetrios Vikelas as its first president...

refused to bar New Zealand. Some of the teams withdrew after the first day. The controversy prevented a much anticipated meeting between Tanzanian Filbert BayiFilbert BayiFilbert Bayi is a former Tanzanian middle-distance runner of the 1970s who set the world records for 1500 metres in 1974 and the mile in 1975...

--the former world record holder in both the 1500 metres1500 metresThe 1,500-metre run is the premier middle distance track event.Aerobic endurance is the biggest factor contributing to success in the 1500 metres but the athlete also requires significant sprint speed.In modern times, the 1,500-metre run has been run at a pace faster than the average person could...

and the mile runMile runThe mile run is a middle-distance foot race which is among the more popular events in track running.The history of the mile run event began in England, where it was used as a distance for gambling races...

; and New Zealand's John WalkerJohn Walker (runner)Sir John George Walker, KNZM, CBE, is a former middle distance runner from New Zealand.Walker was the first person to run the mile in under 3:50, and won the Olympic Games 1500m in Montreal in 1976....

--who had surpassed both records to become the, then, current world record holder in both events. Walker went on to win the gold medal in the 1500 metres.

- Soviet modern pentathleteModern pentathlonThe modern pentathlon is a sports contest that includes five events: pistol shooting, épée fencing, 200 m freestyle swimming, show jumping, and a 3 km cross-country run...

Boris Onischenko was found to have used an épée which had a pushbutton on the pommel in the fencing portion of the pentathlon event. This button, when activated, would cause the electronic scoring system to register a hit whether or not the épée had actually connected with the target area of his opponent. As a result of this discovery, he and the entire male Soviet pentathlon team were disqualified.

- CanadaCanadaCanada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, the host country, incurred $1.5 billion in debt, which was not paid off until December 2006.

1980 Summer Olympics1980 Summer OlympicsThe 1980 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXII Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event celebrated in Moscow in the Soviet Union. In addition, the yachting events were held in Tallinn, and some of the preliminary matches and the quarter-finals of the football tournament...

- 1980 Summer Olympics boycott: U.S. President Jimmy CarterJimmy CarterJames Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

issued a boycottBoycottA boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

of the games to protest the Soviet invasion of AfghanistanSoviet war in AfghanistanThe Soviet war in Afghanistan was a nine-year conflict involving the Soviet Union, supporting the Marxist-Leninist government of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan against the Afghan Mujahideen and foreign "Arab–Afghan" volunteers...

, as the Games were held in MoscowMoscowMoscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

, the capital of the Soviet Union. Many nations refused to participate in the Games. The exact number of boycotting nations is difficult to determine, as a total of 62 eligible countries failed to participate, but some of those countries withdrew due to financial hardships, only claiming to join the boycott to avoid embarrassment. A substitute event, titled the Liberty Bell Classic (often referred to as Olympic Boycott Games) was held at the University of PennsylvaniaUniversity of PennsylvaniaThe University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

in Philadelphia by 29 of the boycotting countries.

- Polish gold medalist pole vaulterPole vaultPole vaulting is a track and field event in which a person uses a long, flexible pole as an aid to leap over a bar. Pole jumping competitions were known to the ancient Greeks, as well as the Cretans and Celts...

Władysław Kozakiewicz showed an obscene bras d'honneurBras d'honneurA bras d'honneur is an obscene gesture. To form the gesture, an arm is bent to make an L-shape, while the other hand then grips the inner side of the bent arm's elbow, and the bent forearm is then raised vertically in a gesturing motion...

gesture to the jeering Soviet public, causing an international scandal and almost losing his medal as a result.

1984 Summer Olympics1984 Summer OlympicsThe 1984 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXIII Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event held in Los Angeles, California, United States in 1984...

- 1984 Summer Olympics boycott1984 Summer Olympics boycottThe boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California. The boycott was a follow up to the American-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. The boycott involved 14 Eastern Bloc countries and allies, led by the Soviet Union who initiated the boycott on May 8, 1984, and joined...

: The Soviet Union and fourteen of its allies boycotted the 1984 Games held in Los AngelesLos ÁngelesLos Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

, United States, citing lack of security for their athletes as the official reason; The decision was regarded as a response to the United States-led boycott issued against the Moscow Olympics four years earlier. The Eastern Bloc organized its own multi-sport eventMulti-sport eventA multi-sport event is an organized sporting event, often held over multiple days, featuring competition in many different sports between organized teams of athletes from nation-states. The first major, modern, multi-sport event of international significance was the modern Olympic Games.Many...

, the Friendship GamesFriendship GamesThe Friendship Games or Friendship-84 was an international multi-sport event held between 2 July and 16 September 1984 in the Soviet Union and eight other socialist states which boycotted the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles....

, instead. For different reasons, IranIranIran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

and LibyaLibyaLibya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

also boycotted the Games.

- In the finals of the 3000 metre track event, a collision involving South African Zola BuddZola BuddZola Pieterse, better known by her maiden name of Zola Budd , is a former Olympic track and field competitor who, in less than three years, twice broke the world record in the women's 5000 metres and twice was the women's winner at the World Cross Country Championships...

(competing for Great Britain) and United States Mary DeckerMary DeckerMary Slaney is an American former track athlete. During her career, she won gold medals in the 1500 meters and 3000 meters at the 1983 World Championships, and set 17 official and unofficial world records and 36 US national records.-Biography:Mary Decker was born in Bunnvale, Hunterdon County, New...

resulted in the latter being unable to complete the race. Although Budd was leading at the time of the collision, and regained and held the lead for a while after it, she eventually finished 7th, fading in the final lap, after boos from the crowd. An IAAF jury later found Budd not responsible for the collision.

1988 Summer Olympics1988 Summer OlympicsThe 1988 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXIV Olympiad, were an all international multi-sport events celebrated from September 17 to October 2, 1988 in Seoul, South Korea. They were the second summer Olympic Games to be held in Asia and the first since the 1964 Summer Olympics...

- North KoreaNorth KoreaThe Democratic People’s Republic of Korea , , is a country in East Asia, occupying the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Its capital and largest city is Pyongyang. The Korean Demilitarized Zone serves as the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea...

boycotted the 1988 Summer Olympics in SeoulSeoulSeoul , officially the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea. A megacity with a population of over 10 million, it is the largest city proper in the OECD developed world...

. AlbaniaAlbaniaAlbania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

, CubaCubaThe Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

, EthiopiaEthiopiaEthiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

, MadagascarMadagascarThe Republic of Madagascar is an island country located in the Indian Ocean off the southeastern coast of Africa...

, NicaraguaNicaraguaNicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

, and SeychellesSeychellesSeychelles , officially the Republic of Seychelles , is an island country spanning an archipelago of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean, some east of mainland Africa, northeast of the island of Madagascar....

also did not attend the games.

- Canadian sprinter Ben JohnsonBen Johnson (athlete)Benjamin Sinclair "Ben" Johnson, CM , is a former sprinter from Canada, who enjoyed a high-profile career during most of the 1980s, winning two Olympic bronze medals and an Olympic gold, which was subsequently rescinded...

was stripped of his gold medal for the 100 metres when he tested positive for stanozololStanozololStanozolol, commonly sold under the name Winstrol , Tenabol and Winstrol Depot , was developed by Winthrop Laboratories in 1962...

after the event.

- In a highly controversial 3-2 judge's decision, South KoreaSouth KoreaThe Republic of Korea , , is a sovereign state in East Asia, located on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula. It is neighbored by the People's Republic of China to the west, Japan to the east, North Korea to the north, and the East China Sea and Republic of China to the south...

n boxerBoxingBoxing, also called pugilism, is a combat sport in which two people fight each other using their fists. Boxing is supervised by a referee over a series of between one to three minute intervals called rounds...

Park Si-HunPark Si-HunPark Si-Hun is a retired South Korean amateur boxer and former Olympic gold medal winner.- Career :...

defeated AmericanUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

Roy Jones, Jr., despite Jones pummeling Park for three rounds, landing 86 punches to Park's 32. Allegedly, Park himself apologized to Jones afterward. One judge shortly thereafter admitted the decision was a mistake, and all three judges voting against Jones were eventually suspended. The official IOCInternational Olympic CommitteeThe International Olympic Committee is an international corporation based in Lausanne, Switzerland, created by Pierre de Coubertin on 23 June 1894 with Demetrios Vikelas as its first president...

investigation concluding in 1997 found no wrongdoing, and the IOC still officially stands by the decision. A similarly controversial decision went against U.S. team member Michael Carbajal. These incidents led Olympic organizers to establish a new scoring system for boxing.

2000 Summer Olympics2000 Summer OlympicsThe Sydney 2000 Summer Olympic Games or the Millennium Games/Games of the New Millennium, officially known as the Games of the XXVII Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event which was celebrated between 15 September and 1 October 2000 in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia...

- RomaniaRomaniaRomania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

n Andreea RăducanAndreea RaducanAndreea Mădălina Răducan is a retired gymnast from Bârlad, Romania.Răducan began competing in gymnastics at a young age and was training at the Romanian junior national facility by the age of 12½. As one of the standout gymnasts of the Romanian team in the late 1990s, Răducan was known for both...

became the first gymnast to be stripped of a medal after testing positive for pseudoephedrinePseudoephedrinePseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes. It is used as a nasal/sinus decongestant and stimulant, or as a wakefulness-promoting agent....

, at the time a prohibited substance. Răducan, 16, took Nurofen, a common over-the-counter medicine, to help treat a fever. The Romanian team doctor who gave her the medication was expelled from the Games and suspended for four years. The gold medal was finally awarded to Răducan's team mate Simona AmânarSimona AmânarSimona Amânar is a Romanian gymnast. She is a seven-time Olympic medalist and a ten-time world medalist. Amânar helped Romania to win four consecutive world team titles as well as the 2000 Olympic team title. She has a vault named after her, the Amanar...

, who had obtained silver. Răducan was allowed to keep her other medals, a gold from the team competition and a silver from the vault.

- Chinese gymnast Dong FangxiaoDong FangxiaoDong Fangxiao is a retired Chinese gymnast. She now lives in New Zealand with her husband, and competed at the 2000 Summer Olympics. She originally won a bronze medal with the Chinese team, however following an investigation, the International Gymnastics Federation ruled that she was under the...

was stripped of a bronze medal in April 2010. Investigations by the sport's governing body (FIG) found that she was only 14 at the 2000 Games. (To be eligible the gymnastic athletes must turn 16 during the Olympic year). Dong also lost a sixth-place result in the individual floor exercises and seventh in the vault. FIG recommended the IOC take the medal back as her scores aided China in winning the team bronze. The US women's team, who had come fourth in the event, now move up to third (bronze medal).

- United States sprinter Marion JonesMarion JonesMarion Lois Jones , also known as Marion Jones-Thompson, is a former world champion track and field athlete, and a former professional basketball player for Tulsa Shock in the WNBA...

won 5 medals in the 100 metres100 metresThe 100 metres, or 100-metre dash, is a sprint race in track and field competitions. The shortest common outdoor running distance, it is one of the most popular and prestigious events in the sport of athletics. It has been contested at the Summer Olympics since 1896...

, 200 metres200 metresA 200 metres race is a sprint running event. On an outdoor 400 m track, the race begins on the curve and ends on the home straight, so a combination of techniques are needed to successfully run the race. A slightly shorter race, called the stadion and run on a straight track, was the first...

, Long jumpLong jumpThe long jump is a track and field event in which athletes combine speed, strength, and agility in an attempt to leap as far as possible from a take off point...

, 4x100 metres relay and 4x400 metres relay. In 2007, after a lengthy investigation of the BALCOBalcoBalco can refer to:* the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative - a controversial sports medicine/nutrition centre in Burlingame, California.* Balco balcony systems who develops, designs and manufactures balcony systems and glazing solutions....

case, Jones admitted in court to having taken performance enhancing drugs (PEDs). She and her relay teammates were subsequently stripped of their Olympic medals. Other individual medalists were advanced, but not all of them. 100 metres silver medalist Ekaterini Thanou of GreeceGreeceGreece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

was accused of evading drug testing herself before the 2004 Summer Olympics2004 Summer OlympicsThe 2004 Summer Olympic Games, officially known as the Games of the XXVIII Olympiad, was a premier international multi-sport event held in Athens, Greece from August 13 to August 29, 2004 with the motto Welcome Home. 10,625 athletes competed, some 600 more than expected, accompanied by 5,501 team...

in her home country, which she suddenly withdrew from at the last minute. She eventually accepted a ban for violating the policy. Amid the controversy, the IOC chose not to advance her medal, instead awarding an additional silver and bronze, but no gold in the event. The reshuffling of medals involving the relay teams are still pending legal appeals. A precedent was established when the winning American men's 4x400 metres relay team was originally allowed to keep their medals, even though Jerome YoungJerome YoungJerome Young in Clarendon, Jamaica, attended high school in Hartford, Connecticut at Prince Technical, is a sprint athlete. He was caught doping in 1999, which cast suspicious shadows over his entire track & field career....

had also admitted taking PEDs and was disqualified. The narrow legal difference is that Young only ran in the preliminary races while Jones ran in the final. That men's relay team has now been disqualified with the additional admission of PED violation by Antonio PettigrewAntonio PettigrewAntonio Pettigrew was an American sprinter who specialized in the 400 meters. He was born in Macon, Georgia....

who ran in the final. Amid the continuing controversy, the IOC has yet to announce the medal advancement for the relays.

2004 Summer Olympics2004 Summer OlympicsThe 2004 Summer Olympic Games, officially known as the Games of the XXVIII Olympiad, was a premier international multi-sport event held in Athens, Greece from August 13 to August 29, 2004 with the motto Welcome Home. 10,625 athletes competed, some 600 more than expected, accompanied by 5,501 team...

- Irish showjumper Cian O'Connor'sCian O'ConnorCián O'Connor is an Irish equestrian who competes in the sport of showjumping.He won a show jumping gold medal at the 2004 Summer Olympics, which was later stripped from him due to drug offences. He continues to ride....

horse, Waterford Crystal, tested positive for fluphenazineFluphenazineFluphenazine is a typical antipsychotic drug used for the treatment of psychoses such as schizophrenia and acute manic phases of bipolar disorder. It belongs to the piperazine class of phenothiazines....

and zuclophenthixol months after receiving a gold medal. The subsequent investigation was hampered by several suspicious events. When O'Connor requested a second test, the horse's B urine sample was stolen enroute to a laboratory. Documents about another horse belonging to O'Connor were stolen in a break-in at the Equestrian Federation of Ireland'sEquestrian Federation of IrelandThe Equestrian Federation of Ireland , is the National Governing Body for all equestrian sport in Ireland. It is a 32-county body, and is therefore responsible for the administration of international competitions throughout the whole island...

headquarters. Finally, in the spring of 2005, O'Connor was stripped of the gold medal.

- Hungarian fencingFencingFencing, which is also known as modern fencing to distinguish it from historical fencing, is a family of combat sports using bladed weapons.Fencing is one of four sports which have been featured at every one of the modern Olympic Games...

official Jozsef Hidasi was suspended for two years by the FIE after committing several errors during an ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

-ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

match.

- CanadianCanadaCanada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

men's rowing pair Chris JarvisChris Jarvis (rower)Chris Jarvis is a Canadian rower. He was born in Grimsby, Ontario and competed in the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens Greece.Jarvis was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 1 at age 13. He wears a Meditronic insulin pump while competing, in order to mitigate the effects of his condition...

and David CalderDavid Calder (rower)David Calder or Dave Calder is a Canadian rower. He was born in Victoria, British Columbia. He graduated from Brentwood College School in 1996....

were disqualified in the semi-final round after they crossed into the lane belonging to the South AfricaSouth AfricaThe Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

n team of Donovan CechDonovan CechDonovan Cech is a South African rower. He competes in the Coxless Pairs division and his boat partner for the past few years has been Ramon di Clemente. The pair won a Bronze medal won in the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens....

and Ramon di ClementeRamon di ClementeRamon di Clemente is an South African rower and Olympic medalist.He competes in the coxless pair event with his boat partner of the past few years, Donovan Cech. They won the bronze medal in the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens....

and in doing so, according to the South Africans, interfered with their progress. The Canadians appealed unsuccessfully to the Court of Arbitration for SportCourt of Arbitration for SportThe Court of Arbitration for Sport is an international arbitration body set up to settle disputes related to sport. Its headquarters are in Lausanne and its courts are located in New York, Sydney and Lausanne, Switzerland...

.

- In the women's 100m hurdlesHurdlingHurdling is a type of track and field race.- Distances :There are sprint hurdle races and long hurdle races. The standard sprint hurdle race is 110 meters for men and 100 meters for women. The standard long hurdle race is 400 meters for both men and women...

, Canadian sprinter Perdita FelicienPerdita FelicienPerdita Felicien is a Canadian hurdler.-Early life:Felicien carries her mother's maiden name, whose origins are in the Caribbean island nation of Saint Lucia...

stepped on the first hurdle, tumbling to the ground and taking Russian Irina ShevchenkoIrina ShevchenkoIrina Shevchenko, née Korotya is a Russian hurdler.Her personal best time is 12.67 seconds, achieved in July 2004 in Tula. She equalled this time in the 2004 Olympic semi final...

with her. The Russian Federation filed an unsuccessful protest, pushing the medal ceremony back a day. Track officials debated for about two hours before rejecting the Russians' arguments. The race was won by the United States' Joanna HayesJoanna HayesJoanna Dove Hayes is an American hurdler, who won the gold medal in the 100 metres hurdles at the 2004 Summer Olympics....

in Olympic-record time.

- In a tournament match in men's volleyballVolleyballVolleyball is a team sport in which two teams of six players are separated by a net. Each team tries to score points by grounding a ball on the other team's court under organized rules.The complete rules are extensive...

, the USUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and Greece were in the final game of the match (Game 5). When the Americans were handling the ball, a whistle was blown from the audience. As a result, the Greeks stopped their defense because in volleyball the ball is "dead" as soon as a whistle blows. To the officials however, it was a still a live ball. That let the Americans make the last spike to win by two to move to the next round. The Greek team protested, but the officials let the play count. No appeal has been made.

- IranIranIran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

ian judoist Arash MiresmailiArash MiresmailiArash Miresmaeili is an Iranian judoka. He is a double world featherweight champion.-World Judo Championships:He won the gold medal in two World Judo Championships, the first one in 2001 in Munich, Germany, and the second in 2003 in Osaka, Japan...

was disqualified after he was found to be overweight before a judo bout against IsraelIsraelThe State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

i Ehud VaksEhud VaksEhud Vaks is an Israeli judo athlete .-2004 Olympics:In the 2004 Summer Olympics, competing in the half lightweight 66 kg weight class, Vaks was scheduled to fight Iranian competitor Arash Miresmaeili in the first round...

. He had gone on an eating binge the night before in a protest against the IOC's recognition of the state of Israel. It was reported that Iranian Olympic team chairman Nassrollah Sajadi had suggested that the Iranian government should give him $115,000 (the amount he would have received if he had won the gold medal) as a reward for his actions. Then-President of Iran, Mohammad KhatamiMohammad KhatamiSayyid Mohammad Khātamī is an Iranian scholar, philosopher, Shiite theologian and Reformist politician. He served as the fifth President of Iran from August 2, 1997 to August 3, 2005. He also served as Iran's Minister of Culture in both the 1980s and 1990s...

, who was reported to have said that Arash's refusal to fight the Israeli would be "recorded in the history of Iranian glories", stated that the nation considered him to be "the champion of the 2004 Olympic Games."

2008 Summer Olympics2008 Summer OlympicsThe 2008 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXIX Olympiad, was a major international multi-sport event that took place in Beijing, China, from August 8 to August 24, 2008. A total of 11,028 athletes from 204 National Olympic Committees competed in 28 sports and 302 events...

- Players for the Spanish men’s and women’s basketballBasketballBasketball is a team sport in which two teams of five players try to score points by throwing or "shooting" a ball through the top of a basketball hoop while following a set of rules...

teams posed for a pre-Olympic newspaper advertisement in popular Spanish daily Marca, in which they are pictured pulling back the skin on either side of their eyes, narrowing them in order to mimic the typical Asian eye. - SwedishSwedenSweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

wrestler Ara AbrahamianAra AbrahamianAra Abrahamian is a retired Armenian-Swedish wrestler in Greco-Roman wrestling...

dropped his bronze medal onto the floor immediately after it was placed around his neck in protest at his loss to Italian Andrea MinguzziAndrea MinguzziAndrea Minguzzi is an Italian wrestler, who has won a gold medal in the 2008 Summer Olympics...

in the semifinals of the men's 84kg Greco-Roman wrestling event. He was subsequently disqualified by the IOC.

- Questions have been raised about the ages of two Chinese female gymnasts, He KexinHe KexinHe Kexin is a Chinese gymnast. At the 2008 Olympics in Beijing she won gold medals on the uneven bars and as a member of the Chinese Artistic Gymnastics team. In 2008, she won two World Cup titles on the uneven bars. On the bars she was one of the few gymnasts in the world to score over 17.00...

and Jiang Yuyuan. This is due partly to their overly-youthful appearance, as well as a speech in 2007 by Chinese director of general administration for sport Liu Peng.

- NorwayNorwayNorway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

’s last second goal against South KoreaSouth KoreaThe Republic of Korea , , is a sovereign state in East Asia, located on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula. It is neighbored by the People's Republic of China to the west, Japan to the east, North Korea to the north, and the East China Sea and Republic of China to the south...

in the semifinals of handball put it through to the Gold Medal game. According to a photograph that has surfaced on the Internet, however, the ball had failed to fully cross the goal line prior to time expiring. The South Koreans protested and requested that the game continue at the overtime point. The IHF has confirmed the results of the match. - Cuban taekwandoist Ángel MatosAngel MatosÁngel Valodia Matos Fuentes is a former Cuban taekwondo athlete. He received a gold medal at the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, and added another at the 2007 Pan American Games in Rio de Janeiro....

was banned for life from any international taekwondoTaekwondoTaekwondo is a Korean martial art and the national sport of South Korea. In Korean, tae means "to strike or break with foot"; kwon means "to strike or break with fist"; and do means "way", "method", or "path"...

events after kicking a referee in the face. Matos attacked the referee after he disqualified Matos for violating the time limit on an injury timeout. He then punched another official.

1968 Winter Olympics1968 Winter OlympicsThe 1968 Winter Olympics, officially known as the X Olympic Winter Games, were a winter multi-sport event which was celebrated in 1968 in Grenoble, France and opened on 6 February. Thirty-seven countries participated...

- French skiier Jean-Claude KillyJean-Claude KillyJean-Claude Killy was an alpine ski racer, who dominated the sport in the late 1960s. He was a triple Olympic champion, winning the three alpine events at the 1968 Winter Olympics, becoming the most successful athlete there...

achieved a clean sweep of the then-three alpine skiing medals at Grenoble, but only after what the IOC bills as the "greatest controversy in the history of the Winter Olympics." The slalom run was held in poor visibility and Austrian skiier Karl SchranzKarl SchranzKarl Schranz is a former champion alpine ski racer, one of the best in the 1960s.During his lengthy career , Schranz won twenty major downhills, many major giant slalom races and several major slaloms...

claimed a mysterious man in black crossed his path during the slalom race, causing him to stop. Schranz was given a re-start and posted the fastest time. A Jury of Appeal then reviewed the television footage, declared that Schranz had missed a gate on the upper part of the first run, annulled his repeat run time, and gave the medal to Killy.

- Three East German competitors in the women's lugeLugeA Luge is a small one- or two-person sled on which one sleds supine and feet-first. Steering is done by flexing the sled's runners with the calf of each leg or exerting opposite shoulder pressure to the seat. Racing sleds weigh 21-25 kilograms for singles and 25-30 kilograms for doubles. Luge...

event were disqualified for illegally heating their runners prior to each run.