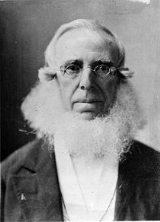

Peter Cooper

Encyclopedia

Peter Cooper was an American

industrialist, inventor, philanthropist

, and candidate for President of the United States

. He designed and built the first steam locomotive

in the U.S., and founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in Manhattan

, New York City

.

of mixed Dutch

, English

and Hugenot descent, the fifth child of John Cooper, a Methodist hatmaker from Newburgh, New York He worked as coachmaker's apprentice, cabinet maker, hatmaker, brewer and grocer, and was throughout a tinkerer: he developed a cloth-shearing machine which he attempted to sell, as well as an endless chain he intended to be used to pull boats

on the Erie Canal

, which De Witt Clinton approved of, but which Cooper was unable to sell.

In 1821 Cooper purchased a glue factory on Sunfish Pond for $2,000 in Kips Bay

, where he had access to raw materials from the nearby slaughterhouse

s, and ran it as a successful business for many years, producing a profit of $10,000 within 2 years, developing new ways to produce glues and cements, gelatin

, isinglass

and other products, and becoming the city's premiere provider to tanners

, manufacturers of paint

s, and dry-goods merchants. The effluent from his successful factory eventually polluted the pond to the extent that in 1839 it had to be drained and filled.

would drive up prices for land in Maryland

, Cooper used his profits to buy 3000 acres (12.1 km²) of land there in 1828 and began to develop them, draining swampland and flattening hills, during which he discovered iron ore on his property. Seeing the B&O as a natural market for iron rails to be made from his ore, he founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore

, and when the railroad developed technical problems, he put together the Tom Thumb

steam locomotive for them in 1830 from various old parts, including musket barrels, and some small-scale steam engines he had fiddled with back in New York. The engine was a rousing success, prompting investors to buy stock in B&O, which enabled the company to buy Cooper's iron rails, making him what would be his first fortune.

Cooper began operating an iron rolling mill in New York beginning in 1836, where he was the first to successfully use anthracite coal

to puddle iron. Cooper later moved the mill to Trenton, New Jersey

on the Delaware River

to be closer to the sources of the raw materials the works needed. His son and son-in-law, Edward Cooper

and Abram S. Hewitt, later expanded the Trenton facility into a giant complex employing 2,000 people, in which iron was taken from raw material to finished product.

Cooper later invested in real estate

and insurance

, and became one of the richest men in New York City

. Despite this, he lived relatively simply in an age when the rich were indulging in more and more luxury. He dressed in simple, plain clothes, and limited his household to only two servants; when his wife bought an expensive and elaborate carriage, he returned it for a more sedate and cheaper one. Cooper remained in his home at Fourth Avenue and 28th Street even after the New York and Harlem Railroad

established freight yards where cattle cars were parked practically outside his front door, although he did move to the more genteel Gramercy Park

development in 1850.

In 1854, Cooper was one of five men who met at the house of Cyrus West Field

in Gramercy Park to form the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company

, and, in 1855, the American Telegraph Company, which bought up competitors and established extensive control over the expanding American network on the Atlantic Coast and in some Gulf coast states. He was among those supervising the laying of the first Transatlantic telegraph cable

in 1858.

In 1840, Cooper became an alderman

In 1840, Cooper became an alderman

of New York City.

Prior to the Civil War

, Cooper was active in the anti-slavery

movement and promoted the application of Christian concepts to solve social injustice. He was a strong supporter of the Union

cause during the war and an advocate of the government issue of paper money.

Influenced by the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Cooper became involved in the Indian reform movement, organizing the privately funded United States Indian Commission. This organization, whose members included William E. Dodge

and Henry Ward Beecher

, was dedicated to the protection and elevation of Native Americans in the United States and the elimination of warfare in the western territories.

Cooper's efforts led to the formation of the Board of Indian Commissioners

, which oversaw Ulysses S. Grant

's Peace Policy. Between 1870 and 1875, Cooper sponsored Indian delegations to Washington, D.C.

, New York City, and other Eastern cities. These delegations met with Indian rights advocates and addressed the public on United States Indian policy. Speakers included: Red Cloud

, Little Raven

, and Alfred B. Meacham

and a delegation of Modoc and Klamath Indians.

Cooper was an ardent critic of the gold standard and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency. Throughout the depression from 1873–78, he said that usury was the foremost political problem of the day. He strongly advocated a credit-based, Government-issued currency of United States Note

s. In 1883 his addresses, letters and articles on public affairs were compiled into a book, Ideas for a Science of Good Government.

without any hope of being elected. His running mate was Samuel Fenton Cary

. The campaign cost more than $

25,000. At the age of 85 years, Cooper is the oldest person ever nominated by any political party for President of the United States. The election was won by Rutherford Birchard Hayes of the Republican Party

. Cooper was surpassed by another unsuccessful candidate: Samuel Jones Tilden

of the Democratic Party

.

and a daughter Sarah Amelia. Edward served as Mayor of New York City

, as would the husband of Sarah Amelia, Abram S. Hewitt, a man also heavily involved in inventions and industrialization.

(Polytechnical School) in Paris

, which would offer free practical education to adults in the mechanical arts and science, to help prepare young men and women of the working classes for success in business.

In 1853 he broke ground for the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private college in New York, completing the building in 1859 at the cost of $600,000. Cooper Union offered open-admission night classes available to men and women alike, and attracted 2,000 responses to its initial offering, although 600 later dropped out. The classes were non-sectarian, and women were treated equally with men, although 95% of the students were male. Cooper started a Women's School of Design, which offered daytime courses in engraving, lithography, painting on china and drawing.

The new institution soon became an important part of the community. The Great Hall was a place where the pressing civic controversies of the day could be debated – and, unusually, radical views were not excluded. In addition, the Union's library, unlike the nearby Astor

, Mercantile and New York Society

Libraries, was open until 10:00 at night, so that working people could make use of them after work hours.

Today Cooper Union is recognized as one of the leading American colleges in the fields of architecture, engineering, and art. Carrying on Peter Cooper's belief that college education should be free, the Cooper Union awards all its students with a full scholarship.

in Brooklyn

, New York

.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

industrialist, inventor, philanthropist

Philanthropist

A philanthropist is someone who engages in philanthropy; that is, someone who donates his or her time, money, and/or reputation to charitable causes...

, and candidate for President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

. He designed and built the first steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

in the U.S., and founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in Manhattan

Manhattan

Manhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

, New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

.

Early life

Peter Cooper was born in New York CityNew York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

of mixed Dutch

Dutch people

The Dutch people are an ethnic group native to the Netherlands. They share a common culture and speak the Dutch language. Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Suriname, Chile, Brazil, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, and the United...

, English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

and Hugenot descent, the fifth child of John Cooper, a Methodist hatmaker from Newburgh, New York He worked as coachmaker's apprentice, cabinet maker, hatmaker, brewer and grocer, and was throughout a tinkerer: he developed a cloth-shearing machine which he attempted to sell, as well as an endless chain he intended to be used to pull boats

Canal boat

There are three articles associated with canal watercraft:* The Volunteer - A replica 1848 canal boat docked on the Illinois and Michigan Canal at LaSalle, Illinois* Narrowboat - a specialized craft for operation in early narrow canals...

on the Erie Canal

Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a waterway in New York that runs about from Albany, New York, on the Hudson River to Buffalo, New York, at Lake Erie, completing a navigable water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes. The canal contains 36 locks and encompasses a total elevation differential of...

, which De Witt Clinton approved of, but which Cooper was unable to sell.

In 1821 Cooper purchased a glue factory on Sunfish Pond for $2,000 in Kips Bay

Kips Bay

Kips Bay is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan. Because there are no official boundaries for New York City neighborhoods, the limits of Kip's Bay are somewhat vague, but it is often considered to be the area between East 23rd Street and East 34th Street extending from...

, where he had access to raw materials from the nearby slaughterhouse

Slaughterhouse

A slaughterhouse or abattoir is a facility where animals are killed for consumption as food products.Approximately 45-50% of the animal can be turned into edible products...

s, and ran it as a successful business for many years, producing a profit of $10,000 within 2 years, developing new ways to produce glues and cements, gelatin

Gelatin

Gelatin is a translucent, colorless, brittle , flavorless solid substance, derived from the collagen inside animals' skin and bones. It is commonly used as a gelling agent in food, pharmaceuticals, photography, and cosmetic manufacturing. Substances containing gelatin or functioning in a similar...

, isinglass

Isinglass

Isinglass is a substance obtained from the dried swim bladders of fish. It is a form of collagen used mainly for the clarification of wine and beer. It can also be cooked into a paste for specialized gluing purposes....

and other products, and becoming the city's premiere provider to tanners

Tanning

Tanning is the making of leather from the skins of animals which does not easily decompose. Traditionally, tanning used tannin, an acidic chemical compound from which the tanning process draws its name . Coloring may occur during tanning...

, manufacturers of paint

Paint

Paint is any liquid, liquefiable, or mastic composition which after application to a substrate in a thin layer is converted to an opaque solid film. One may also consider the digital mimicry thereof...

s, and dry-goods merchants. The effluent from his successful factory eventually polluted the pond to the extent that in 1839 it had to be drained and filled.

Business career

Having been convinced that the proposed Baltimore and Ohio RailroadBaltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was one of the oldest railroads in the United States and the first common carrier railroad. It came into being mostly because the city of Baltimore wanted to compete with the newly constructed Erie Canal and another canal being proposed by Pennsylvania, which...

would drive up prices for land in Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

, Cooper used his profits to buy 3000 acres (12.1 km²) of land there in 1828 and began to develop them, draining swampland and flattening hills, during which he discovered iron ore on his property. Seeing the B&O as a natural market for iron rails to be made from his ore, he founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

, and when the railroad developed technical problems, he put together the Tom Thumb

Tom Thumb (locomotive)

Tom Thumb was the first American-built steam locomotive used on a common-carrier railroad. Designed and built by Peter Cooper in 1830, it was designed to convince owners of the newly formed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to use steam engines...

steam locomotive for them in 1830 from various old parts, including musket barrels, and some small-scale steam engines he had fiddled with back in New York. The engine was a rousing success, prompting investors to buy stock in B&O, which enabled the company to buy Cooper's iron rails, making him what would be his first fortune.

Cooper began operating an iron rolling mill in New York beginning in 1836, where he was the first to successfully use anthracite coal

Anthracite coal

Anthracite is a hard, compact variety of mineral coal that has a high luster...

to puddle iron. Cooper later moved the mill to Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. As of the 2010 United States Census, Trenton had a population of 84,913...

on the Delaware River

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river on the Atlantic coast of the United States.A Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson in 1609 first mapped the river. The river was christened the South River in the New Netherland colony that followed, in contrast to the North River, as the Hudson River was then...

to be closer to the sources of the raw materials the works needed. His son and son-in-law, Edward Cooper

Edward Cooper (mayor)

Edward Cooper was the Mayor of New York City from 1879 to 1880, serving as a Democrat. He was the only son of industrialist Peter Cooper. Edward Cooper's business partner and brother-in-law, Abram S. Hewitt, also served as mayor of New York City . W.R. Grace's terms as mayor separated Cooper's and...

and Abram S. Hewitt, later expanded the Trenton facility into a giant complex employing 2,000 people, in which iron was taken from raw material to finished product.

Cooper later invested in real estate

Real estate

In general use, esp. North American, 'real estate' is taken to mean "Property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals, or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this; an item of real property; buildings or...

and insurance

Insurance

In law and economics, insurance is a form of risk management primarily used to hedge against the risk of a contingent, uncertain loss. Insurance is defined as the equitable transfer of the risk of a loss, from one entity to another, in exchange for payment. An insurer is a company selling the...

, and became one of the richest men in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. Despite this, he lived relatively simply in an age when the rich were indulging in more and more luxury. He dressed in simple, plain clothes, and limited his household to only two servants; when his wife bought an expensive and elaborate carriage, he returned it for a more sedate and cheaper one. Cooper remained in his home at Fourth Avenue and 28th Street even after the New York and Harlem Railroad

New York and Harlem Railroad

The New York and Harlem Railroad was one of the first railroads in the United States, and possibly also the world's first street railway. Designed by John Stephenson, it was opened in stages between 1832 and 1852 between Lower Manhattan to and beyond Harlem...

established freight yards where cattle cars were parked practically outside his front door, although he did move to the more genteel Gramercy Park

Gramercy Park

Gramercy Park is a small, fenced-in private park in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States. The park is at the core of both the neighborhood referred to as either Gramercy or Gramercy Park and the Gramercy Park Historic District...

development in 1850.

In 1854, Cooper was one of five men who met at the house of Cyrus West Field

Cyrus West Field

Cyrus West Field was an American businessman and financier who, along with other entrepreneurs, created the Atlantic Telegraph Company and laid the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858.-Life and career:...

in Gramercy Park to form the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company

New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company

The New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company was a company in a series of conglomerations of several companies that eventually laid the first Trans-Atlantic cable....

, and, in 1855, the American Telegraph Company, which bought up competitors and established extensive control over the expanding American network on the Atlantic Coast and in some Gulf coast states. He was among those supervising the laying of the first Transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cable

The transatlantic telegraph cable was the first cable used for telegraph communications laid across the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. It crossed from , Foilhommerum Bay, Valentia Island, in western Ireland to Heart's Content in eastern Newfoundland. The transatlantic cable connected North America...

in 1858.

Political views and career

Alderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members themselves rather than by popular vote, or a council...

of New York City.

Prior to the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Cooper was active in the anti-slavery

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

movement and promoted the application of Christian concepts to solve social injustice. He was a strong supporter of the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

cause during the war and an advocate of the government issue of paper money.

Influenced by the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Cooper became involved in the Indian reform movement, organizing the privately funded United States Indian Commission. This organization, whose members included William E. Dodge

William E. Dodge

William Earle Dodge, Sr. was a New York businessman, referred to as one of the "Merchant Princes" of Wall Street in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Dodge was also a noted abolitionist, and Native American rights activist and served as the president of the National Temperance...

and Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher was a prominent Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, abolitionist, and speaker in the mid to late 19th century...

, was dedicated to the protection and elevation of Native Americans in the United States and the elimination of warfare in the western territories.

Cooper's efforts led to the formation of the Board of Indian Commissioners

Board of Indian Commissioners

The Board of Indian Commissioners was a committee that advised the federal government of the United States on Native American policy and it inspected supplies delivered to Indian agencies to ensure the fufillment of government treaty obligations to tribes....

, which oversaw Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

's Peace Policy. Between 1870 and 1875, Cooper sponsored Indian delegations to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, New York City, and other Eastern cities. These delegations met with Indian rights advocates and addressed the public on United States Indian policy. Speakers included: Red Cloud

Red Cloud

Red Cloud , was a war leader and the head Chief of the Oglala Lakota . His reign was from 1868 to 1909...

, Little Raven

Little Raven

The Little Raven is a species of the crow and raven family Corvidae, that is endemic to Australia. It has all-black plumage, beak and legs with a white iris, as do the other Corvus members in Australia and some species from the islands to the north.-Taxonomy:Although the Little Raven was first...

, and Alfred B. Meacham

Alfred B. Meacham

Alfred Benjamin Meacham was an American Methodist minister, reformer, author and historian, who served as the US Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon . He became a proponent of American Indian interests in the Northwest, including Northern California...

and a delegation of Modoc and Klamath Indians.

Cooper was an ardent critic of the gold standard and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency. Throughout the depression from 1873–78, he said that usury was the foremost political problem of the day. He strongly advocated a credit-based, Government-issued currency of United States Note

United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for over 100 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were known popularly as "greenbacks" in their heyday, a...

s. In 1883 his addresses, letters and articles on public affairs were compiled into a book, Ideas for a Science of Good Government.

Presidential candidacy

Cooper was encouraged to run in the 1876 presidential election for the Greenback PartyUnited States Greenback Party

The Greenback Party was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology that was active between 1874 and 1884. Its name referred to paper money, or "greenbacks," that had been issued during the American Civil War and afterward...

without any hope of being elected. His running mate was Samuel Fenton Cary

Samuel Fenton Cary

Samuel Fenton Cary was a congressman and significant temperance movement leader in the nineteenth century. Cary became well-known nationally as a prohibitionist author and lecturer.-Life:...

. The campaign cost more than $

United States dollar

The United States dollar , also referred to as the American dollar, is the official currency of the United States of America. It is divided into 100 smaller units called cents or pennies....

25,000. At the age of 85 years, Cooper is the oldest person ever nominated by any political party for President of the United States. The election was won by Rutherford Birchard Hayes of the Republican Party

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

. Cooper was surpassed by another unsuccessful candidate: Samuel Jones Tilden

Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden was the Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in the disputed election of 1876, one of the most controversial American elections of the 19th century. He was the 25th Governor of New York...

of the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

.

A political family

In 1813, Cooper married Sarah Bedell (1793–1869). They had a son, EdwardEdward Cooper (mayor)

Edward Cooper was the Mayor of New York City from 1879 to 1880, serving as a Democrat. He was the only son of industrialist Peter Cooper. Edward Cooper's business partner and brother-in-law, Abram S. Hewitt, also served as mayor of New York City . W.R. Grace's terms as mayor separated Cooper's and...

and a daughter Sarah Amelia. Edward served as Mayor of New York City

Mayor of New York City

The Mayor of the City of New York is head of the executive branch of New York City's government. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property, police and fire protection, most public agencies, and enforces all city and state laws within New York City.The budget overseen by the...

, as would the husband of Sarah Amelia, Abram S. Hewitt, a man also heavily involved in inventions and industrialization.

Cooper Union

Cooper had for many years held an interest in adult education: he had served as head of the Public School Society – a private organization which ran New York City's free schools using city money – when it began evening classes in 1848. Cooper conceived of the idea of having a free institute in New York, similar to the École PolytechniqueÉcole Polytechnique

The École Polytechnique is a state-run institution of higher education and research in Palaiseau, Essonne, France, near Paris. Polytechnique is renowned for its four year undergraduate/graduate Master's program...

(Polytechnical School) in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, which would offer free practical education to adults in the mechanical arts and science, to help prepare young men and women of the working classes for success in business.

In 1853 he broke ground for the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private college in New York, completing the building in 1859 at the cost of $600,000. Cooper Union offered open-admission night classes available to men and women alike, and attracted 2,000 responses to its initial offering, although 600 later dropped out. The classes were non-sectarian, and women were treated equally with men, although 95% of the students were male. Cooper started a Women's School of Design, which offered daytime courses in engraving, lithography, painting on china and drawing.

The new institution soon became an important part of the community. The Great Hall was a place where the pressing civic controversies of the day could be debated – and, unusually, radical views were not excluded. In addition, the Union's library, unlike the nearby Astor

Astor Library

The Astor Library was a free public library developed primarily through the collaboration of New York merchant John Jacob Astor and New England educator and bibliographer Joseph Cogswell. It was primarily meant as a research library, and its books did not circulate...

, Mercantile and New York Society

New York Society Library

The New York Society Library is the oldest cultural institution in New York City. It was founded in 1754 by the New York Society as a subscription library. During the time when New York was the capital of the United States, it was the de facto Library of Congress. Until the establishment of the...

Libraries, was open until 10:00 at night, so that working people could make use of them after work hours.

Today Cooper Union is recognized as one of the leading American colleges in the fields of architecture, engineering, and art. Carrying on Peter Cooper's belief that college education should be free, the Cooper Union awards all its students with a full scholarship.

Death

Peter Cooper died on April 4, 1883 at the age of 92. He is buried in Green-Wood CemeteryGreen-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood Cemetery was founded in 1838 as a rural cemetery in Brooklyn, Kings County , New York. It was granted National Historic Landmark status in 2006 by the U.S. Department of the Interior.-History:...

in Brooklyn

Brooklyn

Brooklyn is the most populous of New York City's five boroughs, with nearly 2.6 million residents, and the second-largest in area. Since 1896, Brooklyn has had the same boundaries as Kings County, which is now the most populous county in New York State and the second-most densely populated...

, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

.

External links

- Mechanic to Millionaire: The Peter Cooper Story, as seen on PBS Jan. 2, 2011

- Comprehensive Biography by Nathan C. Walker

- Facts About Peter Cooper and The Cooper Union

- Brief biography

- Find-A-Grave profile for Peter Cooper

- Extensive Information about Peter Cooper

- Images of Peter Cooper's Autobiography

- Peter Cooper's Dictated Autobiography

- The death of slavery by Peter Cooper at archive.org