.gif)

Polymorphism (biology)

Encyclopedia

Panmixia

Panmixia means random mating.A panmictic population is one where all individuals are potential partners. This assumes that there are no mating restrictions, neither genetic or behavioural, upon the population, and that therefore all recombination is possible...

population (one with random mating).

Polymorphism is common in nature; it is related to biodiversity

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is the degree of variation of life forms within a given ecosystem, biome, or an entire planet. Biodiversity is a measure of the health of ecosystems. Biodiversity is in part a function of climate. In terrestrial habitats, tropical regions are typically rich whereas polar regions...

, genetic variation

Genetic variation

Genetic variation, variation in alleles of genes, occurs both within and among populations. Genetic variation is important because it provides the “raw material” for natural selection. Genetic variation is brought about by mutation, a change in a chemical structure of a gene. Polyploidy is an...

and adaptation

Adaptation

An adaptation in biology is a trait with a current functional role in the life history of an organism that is maintained and evolved by means of natural selection. An adaptation refers to both the current state of being adapted and to the dynamic evolutionary process that leads to the adaptation....

; it usually functions to retain variety of form in a population living in a varied environment. The most common example is sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is a phenotypic difference between males and females of the same species. Examples of such differences include differences in morphology, ornamentation, and behavior.-Examples:-Ornamentation / coloration:...

, which occurs in many organisms. Other examples are mimetic forms of butterflies (see mimicry), and human haemoglobin and blood types.

Polymorphism results from evolutionary processes, as does any aspect of a species. It is heritable and is modified by natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

. In polyphenism

Polyphenism

A polyphenic trait is a trait for which multiple, discrete phenotypes can arise from a single genotype as a result of differing environmental conditions.-Definition:A polyphenism is a biological mechanism that causes a trait to be polyphenic...

, an individual's genetic make-up allows for different morphs, and the switch mechanism that determines which morph is shown is environmental. In genetic polymorphism, the genetic make-up determines the morph. Ants exhibit both types in a single population.

Polymorphism as described here involves morphs of the phenotype

Phenotype

A phenotype is an organism's observable characteristics or traits: such as its morphology, development, biochemical or physiological properties, behavior, and products of behavior...

. The term is also used somewhat differently by molecular biologists to describe certain point mutations in the genotype

Genotype

The genotype is the genetic makeup of a cell, an organism, or an individual usually with reference to a specific character under consideration...

, such as SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphism

A single-nucleotide polymorphism is a DNA sequence variation occurring when a single nucleotide — A, T, C or G — in the genome differs between members of a biological species or paired chromosomes in an individual...

(see also RFLPs). This usage is not discussed in this article.

Terminology

Although in general use polymorphism is quite a broad term, in biology it has been given a specific meaning.- The term omits characters showing continuous variation (such as weight), even though this has a heritable component. Polymorphism deals with forms in which the variation is discrete (discontinuous) or strongly bimodal or polymodal.

- Morphs must occupy the same habitat at the same time: this excludes geographical races and seasonal forms. The use of the words morph or polymorphism for what is a visibly different geographical race or variant is common, but incorrect. The significance of geographical variation is in that it may lead to allopatric speciationAllopatric speciationAllopatric speciation or geographic speciation is speciation that occurs when biological populations of the same species become isolated due to geographical changes such as mountain building or social changes such as emigration...

, whereas true polymorphism takes place in panmictic populations. - The term was first used to describe visible forms, but nowadays it has been extended to include cryptic morphs, for instance blood types, which can be revealed by a test.

- Rare variations are not classified as polymorphisms; and mutations by themselves do not constitute polymorphisms. To qualify as a polymorphism there has to be some kind of balance between morphs underpinned by inheritance. The criterion is that the frequency of the least common morph is too high simply to be the result of new mutationMutationIn molecular biology and genetics, mutations are changes in a genomic sequence: the DNA sequence of a cell's genome or the DNA or RNA sequence of a virus. They can be defined as sudden and spontaneous changes in the cell. Mutations are caused by radiation, viruses, transposons and mutagenic...

s or, as a rough guide, that it is greater than 1 percent (though that is far higher than any normal mutation rate for a single alleleAlleleAn allele is one of two or more forms of a gene or a genetic locus . "Allel" is an abbreviation of allelomorph. Sometimes, different alleles can result in different observable phenotypic traits, such as different pigmentation...

).

Nomenclature

Polymorphism crosses several discipline boundaries, including ecology and genetics, evolution theory, taxonomy, cytology and biochemistry. Different disciplines may give the same concept different names, and different concepts may be given the same name. For example, there are the terms established in ecological genetics by E.B. FordE.B. Ford

Edmund Brisco "Henry" Ford FRS Hon. FRCP was a British ecological geneticist. He was a leader among those British biologists who investigated the role of natural selection in nature. As a schoolboy Ford became interested in lepidoptera, the group of insects which includes butterflies and moths...

(1975), and for classical genetics by John Maynard Smith

John Maynard Smith

John Maynard Smith,His surname was Maynard Smith, not Smith, nor was it hyphenated. F.R.S. was a British theoretical evolutionary biologist and geneticist. Originally an aeronautical engineer during the Second World War, he took a second degree in genetics under the well-known biologist J.B.S....

(1998). The shorter term morphism may be more accurate than polymorphism, but is not often used. It was the preferred term of the evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis...

(1955).

Various synonymous terms exist for the various polymorphic forms of an organism. The most common are morph and morpha, while a more formal term is morphotype. Form and phase

Gametic phase

In a diploid individual, the gametic phase represents the original allelic combinations that an individual received from its parents. It is therefore a particular association of alleles at different loci on the same chromosome, which is often unknown....

are sometimes also used, but are easily confused in zoology with, respectively, "form" in a population of animals, and "phase" as a color or other change in an organism due to environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, etc.). Phenotypic traits and characteristics are also possible descriptions, though that would imply just a limited aspect of the body.

In the taxonomic nomenclature

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the science of identifying and naming species, and arranging them into a classification. The field of taxonomy, sometimes referred to as "biological taxonomy", revolves around the description and use of taxonomic units, known as taxa...

of zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

, the word "morpha" plus a Latin name for the morph can be added to a binomial

Binomial nomenclature

Binomial nomenclature is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, although they can be based on words from other languages...

or trinomial

Trinomial nomenclature

In biology, trinomial nomenclature refers to names for taxa below the rank of species. This is different for animals and plants:* for animals see trinomen. There is only one rank allowed below the rank of species: subspecies....

name. However, this invites confusion with geographically-variant ring species

Ring species

In biology, a ring species is a connected series of neighboring populations, each of which can interbreed with closely sited related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly related to interbreed, though there is a potential gene...

or subspecies

Subspecies

Subspecies in biological classification, is either a taxonomic rank subordinate to species, ora taxonomic unit in that rank . A subspecies cannot be recognized in isolation: a species will either be recognized as having no subspecies at all or two or more, never just one...

, especially if polytypic. Morphs have no formal standing in the ICZN

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals...

. In botanical taxonomy

Botany

Botany, plant science, or plant biology is a branch of biology that involves the scientific study of plant life. Traditionally, botany also included the study of fungi, algae and viruses...

, the concept of morphs is represented with the terms "variety", "subvariety

Subvariety

In botanical nomenclature, a subvariety is a taxonomic rank below that of variety but above that of form : it is an infraspecific taxon. Its name consists of three parts: a genus name, a specific epithet and an infraspecific epithet. To indicate the rank, the abbreviation "subvar." should be put...

" and "form

Form (botany)

In botanical nomenclature, a form is one of the "secondary" taxonomic ranks, below that of variety, which in turn is below that of species; it is an infraspecific taxon...

", which are formally regulated by the ICBN. Horticulturalists sometimes confuse this usage of "variety" both with cultivar

Cultivar

A cultivar'Cultivar has two meanings as explained under Formal definition. When used in reference to a taxon, the word does not apply to an individual plant but to all those plants sharing the unique characteristics that define the cultivar. is a plant or group of plants selected for desirable...

("variety" in viticultural usage, rice agriculture jargon, and informal gardening

Gardening

Gardening is the practice of growing and cultivating plants. Ornamental plants are normally grown for their flowers, foliage, or overall appearance; useful plants are grown for consumption , for their dyes, or for medicinal or cosmetic use...

lingo) and with the legal concept "plant variety" (protection of a cultivar as a form of intellectual property

Intellectual property

Intellectual property is a term referring to a number of distinct types of creations of the mind for which a set of exclusive rights are recognized—and the corresponding fields of law...

).

Ecology

Selection, whether natural or artificial, changes the frequency of morphs within a population; this occurs when morphs reproduce with different degrees of success. A genetic (or balanced) polymorphism usually persists over many generations, maintained by two or more opposed and powerful selection pressures. Diver (1929) found banding morphs in Cepaea nemoralis could be seen in pre-fossil shells going back to the MesolithicMesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

Holocene

Holocene

The Holocene is a geological epoch which began at the end of the Pleistocene and continues to the present. The Holocene is part of the Quaternary period. Its name comes from the Greek words and , meaning "entirely recent"...

. Apes have similar blood groups to humans; this suggests rather strongly that this kind of polymorphism is quite ancient, at least as far back as the last common ancestor of the apes and man, and possibly even further.

Effective fitness

In natural evolution and artificial evolution the fitness of a schema is rescaled to give its effective fitness which takes into account crossover and mutation...

of the morphs at a particular time and place. The mechanism of heterozygote advantage

Heterozygote advantage

A heterozygote advantage describes the case in which the heterozygote genotype has a higher relative fitness than either the homozygote dominant or homozygote recessive genotype. The specific case of heterozygote advantage is due to a single locus known as overdominance...

assures the population of some alternative alleles at the locus

Locus (genetics)

In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

or loci involved. Only if competing selection disappears will an allele disappear. However, heterozygote advantage is not the only way a polymorphism can be maintained. Apostatic selection

Apostatic selection

Apostatic selection is frequency-dependent selection by predators, particularly in regard to prey that are different morphs of a polymorphic species that is not a mimic of another species. It is closely linked to the idea of prey switching, however the two terms are regularly used to describe...

, whereby a predator consumes a common morph whilst overlooking rarer morphs is possible and does occur. This would tend to preserve rarer morphs from extinction.

A polymorphic population does not initiate speciation

Speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which new biological species arise. The biologist Orator F. Cook seems to have been the first to coin the term 'speciation' for the splitting of lineages or 'cladogenesis,' as opposed to 'anagenesis' or 'phyletic evolution' occurring within lineages...

; nor does it prevent speciation. It has little or nothing to do with species splitting. However, it has a lot to do with the adaptation

Adaptation

An adaptation in biology is a trait with a current functional role in the life history of an organism that is maintained and evolved by means of natural selection. An adaptation refers to both the current state of being adapted and to the dynamic evolutionary process that leads to the adaptation....

of a species to its environment, which may vary in colour, food supply, predation and in many other ways. Polymorphism is one good way the opportunities get to be used; it has survival value, and the selection of modifier genes may reinforce the polymorphism.

Polymorphism and niche diversity

G. Evelyn HutchinsonG. Evelyn Hutchinson

George Evelyn Hutchinson FRS was an Anglo-American zoologist known for his studies of freshwater lakes and considered the father of American limnology....

, a founder of niche research, commented "It is very likely from an ecological point of view that all species, or at least all common species, consist of populations adapted to more than one niche". He gave as examples sexual size dimorphism and mimicry. In many cases where the male is short-lived and smaller than the female, he does not compete with her during her late pre-adult and adult life. Size difference may permit both sexes to exploit different niches. In elaborate cases of mimicry, such as the African butterfly Papilio dardanus

Papilio dardanus

Papilio dardanus , is a species of butterfly in the family Papilionidae . The species is broadly distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa. The British entomologist E. B...

, female morphs mimic a range of distasteful models, often in the same region. The fitness of each type of mimic decreases as it becomes more common, so the polymorphism is maintained by frequency-dependent selection. Thus the efficiency of the mimicry is maintained in a much increased total population.

The switch

The mechanism which decides which of several morphs an individual displays is called the switch. This switch may be genetic, or it may be environmental. Taking sex determination as the example, in humans the determination is genetic, by the XY sex-determination systemXY sex-determination system

The XY sex-determination system is the sex-determination system found in humans, most other mammals, some insects and some plants . In this system, females have two of the same kind of sex chromosome , and are called the homogametic sex. Males have two distinct sex chromosomes , and are called...

. In Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is one of the largest orders of insects, comprising the sawflies, wasps, bees and ants. There are over 130,000 recognized species, with many more remaining to be described. The name refers to the heavy wings of the insects, and is derived from the Ancient Greek ὑμήν : membrane and...

(ants, bees and wasps), sex determination is by haplo-diploidy: the females are all diploid, the males are haploid. However, in some animals an environmental trigger determines the sex: alligators are a famous case in point. In ants the distinction between workers and guards is environmental, by the feeding of the grubs. Polymorphism with an environmental trigger is called polyphenism

Polyphenism

A polyphenic trait is a trait for which multiple, discrete phenotypes can arise from a single genotype as a result of differing environmental conditions.-Definition:A polyphenism is a biological mechanism that causes a trait to be polyphenic...

.

The polyphenic system does have a degree of environmental flexibility not present in the genetic polymorphism. However, such environmental triggers are the less common of the two methods.

Investigative methods

Investigation of polymorphism requires a coming together of field and laboratory technique. In the field:- detailed survey of occurrence, habits and predation

- selection of an ecological area or areas, with well-defined boundaries

- capture, mark, release, recapture data (see Mark and recaptureMark and recaptureMark and recapture is a method commonly used in ecology to estimate population size. This method is most valuable when a researcher fails to detect all individuals present within a population of interest every time that researcher visits the study area...

) - relative numbers and distribution of morphs

- estimation of population sizes

And in the laboratory:

- genetic data from crosses

- population cages

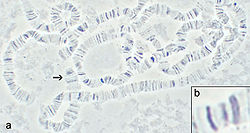

- chromosomeChromosomeA chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

cytologyCell biologyCell biology is a scientific discipline that studies cells – their physiological properties, their structure, the organelles they contain, interactions with their environment, their life cycle, division and death. This is done both on a microscopic and molecular level...

if possible - use of chromatographyChromatographyChromatography is the collective term for a set of laboratory techniques for the separation of mixtures....

or similar techniques if morphs are cryptic (for example, biochemical)

Both types of work are equally important. Without proper field-work the significance of the polymorphism to the species is uncertain; without laboratory breeding the genetic basis is obscure. Even with insects the work may take many years; examples of Batesian mimicry

Batesian mimicry

Batesian mimicry is a form of mimicry typified by a situation where a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a common predator...

noted in the nineteenth century are still being researched.

Genetic polymorphism

Since all polymorphism has a genetic basis, genetic polymorphism has a particular meaning:- Genetic polymorphism is the simultaneous occurrence in the same locality of two or more discontinuous forms in such proportions that the rarest of them cannot be maintained just by recurrent mutation or immigration.

The definition has three parts: a) sympatry

Sympatry

In biology, two species or populations are considered sympatric when they exist in the same geographic area and thus regularly encounter one another. An initially-interbreeding population that splits into two or more distinct species sharing a common range exemplifies sympatric speciation...

: one interbreeding population; b) discrete forms; and c) not maintained just by mutation.

Genetic polymorphism is actively and steadily maintained in populations by natural selection, in contrast to transient polymorphisms where a form is progressively replaced by another. By definition, genetic polymorphism relates to a balance or equilibrium between morphs. The mechanisms that conserve it are types of balancing selection

Balancing selection

Balancing selection refers to a number of selective processes by which multiple alleles are actively maintained in the gene pool of a population at frequencies above that of gene mutation. This usually happens when the heterozygotes for the alleles under consideration have a higher adaptive value...

.

Mechanisms of balancing selection

- HeterosisHeterosisHeterosis, or hybrid vigor, or outbreeding enhancement, is the improved or increased function of any biological quality in a hybrid offspring. The adjective derived from heterosis is heterotic....

(or heterozygote advantageHeterozygote advantageA heterozygote advantage describes the case in which the heterozygote genotype has a higher relative fitness than either the homozygote dominant or homozygote recessive genotype. The specific case of heterozygote advantage is due to a single locus known as overdominance...

): "Heterosis: the heterozygote at a locusLocus (genetics)In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

is fitter than either homozygote".

- Frequency dependent selectionFrequency dependent selectionFrequency-dependent selection is the term given to an evolutionary process where the fitness of a phenotype is dependent on its frequency relative to other phenotypes in a given population. In positive frequency-dependent selection the fitness of a phenotype increases as it becomes more common...

: The fitness of a particular phenotype is dependent on its frequency relative to other phenotypes in a given population. Example: prey switchingPrey switchingPrey switching is frequency-dependent predation, where the predator preferentially consumes the most common type of prey. The phenomenon has also been described as apostatic selection, however the two terms are generally used to describe different parts of the same phenomenon. Apostatic selection...

, where rare morphs of prey are actually fitter due to predators concentrating on the more frequent morphs.

- Fitness varies in time and space. Fitness of a genotype may vary greatly between larval and adult stages, or between parts of a habitat range.

- Selection acts differently at different levels. The fitness of a genotype may depend on the fitness of other genotypes in the population: this covers many natural situations where the best thing to do (from the point of view of survival and reproduction) depends on what other members of the population are doing at the time.

Pleiotropism

Most genes have more than one effect on the phenotypePhenotype

A phenotype is an organism's observable characteristics or traits: such as its morphology, development, biochemical or physiological properties, behavior, and products of behavior...

of an organism (pleiotropism

Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences multiple phenotypic traits. Consequently, a mutation in a pleiotropic gene may have an effect on some or all traits simultaneously...

). Some of these effects may be visible, and others cryptic, so it is often important to look beyond the most obvious effects of a gene to identify other effects. Cases occur where a gene affects an unimportant visible character, yet a change in fitness is recorded. In such cases the gene's other (cryptic or 'physiological') effects may be responsible for the change in fitness.

- "If a neutral trait is pleiotropically linked to an advantageous one, it may emerge because of a process of natural selection. It was selected but this doesn't mean it is an adaptation. The reason is that, although it was selected, there was no selection for that trait."

Epistasis

EpistasisEpistasis

In genetics, epistasis is the phenomenon where the effects of one gene are modified by one or several other genes, which are sometimes called modifier genes. The gene whose phenotype is expressed is called epistatic, while the phenotype altered or suppressed is called hypostatic...

occurs when the expression of one gene is modified by another gene. For example, gene A only shows its effect when allele B1 (at another Locus

Locus (genetics)

In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

) is present, but not if it is absent. This is one of the ways in which two or more genes may combine to produce a coordinated change in more than one characteristic (for instance, in mimicry). Unlike the supergene, epistatic genes do not need to be closely linked

Genetic linkage

Genetic linkage is the tendency of certain loci or alleles to be inherited together. Genetic loci that are physically close to one another on the same chromosome tend to stay together during meiosis, and are thus genetically linked.-Background:...

or even on the same chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

.

Both pleiotropism and epistasis show that a gene need not relate to a character in the simple manner that was once supposed.

The origin of supergenes

Although a polymorphism can be controlled by alleles at a single locusLocus (genetics)

In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

(e.g. human ABO

Abo

Abo may refer to:* ABO blood group system, a human blood type and blood group system** ABO , enzyme encoded by the ABO gene that determines the ABO blood group of an individual* Abo of Tiflis , an Arab East Orthodox Catholic saint...

blood groups), the more complex forms are controlled by supergene

Supergene

A supergene is a group of neighbouring genes on a chromosome which are inherited together because of close genetic linkage and are functionally related in an evolutionary sense, although they are rarely co-regulated genetically....

s consisting of several tightly linked genes on a single chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

. Batesian mimicry

Batesian mimicry

Batesian mimicry is a form of mimicry typified by a situation where a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a common predator...

in butterflies and heterostyly

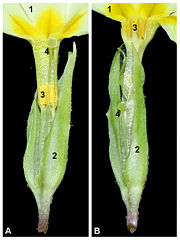

Heterostyly

Heterostyly is a unique form of polymorphism and herkogamy in flowers. In a heterostylous species, two or three different morphological types of flowers, termed morphs, exist in the population. On each individual plant, all flowers share the same morph. The flower morphs differ in the lengths of...

in angiosperms are good examples. There is a long-standing debate as to how this situation could have arisen, and the question is not yet resolved.

Whereas a gene family

Gene family

A gene family is a set of several similar genes, formed by duplication of a single original gene, and generally with similar biochemical functions...

(several tighly linked genes performing similar or identical functions) arises by duplication of a single original gene, this is usually not the case with supergenes. In a supergene some of the constituent genes have quite distinct functions, so they must have come together under selection. This process might involve suppression of crossing-over, translocation of chromosome fragments and possibly occasional cistron duplication. That crossing-over can be suppressed by selection has been known for many years.

Debate has centred round the question of whether the component genes in a super-gene could have started off on separate chromosomes, with subsequent reorganization, or if it is necessary for them to start on the same chromosome. Originally, it was held that chromosome rearrangement would play an important role. This explanation was accepted by E. B. Ford and incorporated into his accounts of ecological genetics.

However, today many believe it more likely that the genes start on the same chromosome. They argue that supergenes arose in situ. This is known as Turner's sieve hypothesis. John Maynard Smith agreed with this view in his authoritative textbook, but the question is still not definitively settled.

Relevance for evolutionary theory

Polymorphism was crucial to research in ecological geneticsEcological genetics

Ecological genetics is the study of genetics in natural populations.This contrasts with classical genetics, which works mostly on crosses between laboratory strains, and DNA sequence analysis, which studies genes at the molecular level....

by E. B. Ford and his co-workers from the mid-1920s to the 1970s (similar work continues today, especially on mimicry). The results had a considerable effect on the mid-century evolutionary synthesis, and on present evolutionary theory. The work started at a time when natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

was largely discounted as the leading mechanism for evolution, continued through the middle period when Sewall Wright

Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. With R. A. Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane, he was a founder of theoretical population genetics. He is the discoverer of the inbreeding coefficient and of...

's ideas on drift

Genetic drift

Genetic drift or allelic drift is the change in the frequency of a gene variant in a population due to random sampling.The alleles in the offspring are a sample of those in the parents, and chance has a role in determining whether a given individual survives and reproduces...

were prominent, to the last quarter of the 20th century when ideas such as Kimura

Motoo Kimura

was a Japanese biologist best known for introducing the neutral theory of molecular evolution in 1968. He became one of the most influential theoretical population geneticists. He is remembered in genetics for his innovative use of diffusion equations to calculate the probability of fixation of...

's neutral theory of molecular evolution

Neutral theory of molecular evolution

The neutral theory of molecular evolution states that the vast majority of evolutionary changes at the molecular level are caused by random drift of selectively neutral mutants . The theory was introduced by Motoo Kimura in the late 1960s and early 1970s...

was given much attention. The significance of the work on ecological genetics is that it has shown how important selection is in the evolution of natural populations, and that selection is a much stronger force than was envisaged even by those population geneticists who believed in its importance, such as Haldane

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane FRS , known as Jack , was a British-born geneticist and evolutionary biologist. A staunch Marxist, he was critical of Britain's role in the Suez Crisis, and chose to leave Oxford and moved to India and became an Indian citizen...

and Fisher

Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher FRS was an English statistician, evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and geneticist. Among other things, Fisher is well known for his contributions to statistics by creating Fisher's exact test and Fisher's equation...

.

In just a couple of decades the work of Fisher, Ford, Arthur Cain

Arthur Cain

Arthur James Cain FRS was a British evolutionary biologist and ecologist. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1989.- Life :...

, Philip Sheppard and Cyril Clarke

Cyril Clarke

Sir Cyril Astley Clarke KBE, FRCP, FRCOG, FRC Path, FRS was a British physician, geneticist and lepidopterist...

promoted natural selection as the primary explanation of variation in natural populations, instead of genetic drift. Evidence can be seen in Mayr's famous book Animal Species and Evolution, and Ford's Ecological Genetics. Similar shifts in emphasis can be seen in most of the other participants in the evolutionary synthesis, such as Stebbins

G. Ledyard Stebbins

George Ledyard Stebbins, Jr. was an American botanist and geneticist who is widely regarded as one of the leading evolutionary biologists of the 20th century. Stebbins received his Ph.D. in botany from Harvard University in 1931. He went on to the University of California, Berkeley, where his work...

and Dobzhansky

Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Grygorovych Dobzhansky ForMemRS was a prominent geneticist and evolutionary biologist, and a central figure in the field of evolutionary biology for his work in shaping the unifying modern evolutionary synthesis...

, though the latter was slow to change.

Kimura

Motoo Kimura

was a Japanese biologist best known for introducing the neutral theory of molecular evolution in 1968. He became one of the most influential theoretical population geneticists. He is remembered in genetics for his innovative use of diffusion equations to calculate the probability of fixation of...

drew a distinction between molecular evolution, which he saw as dominated by selectively neutral mutations, and phenotypic characters, probably dominated by natural selection rather than drift. This does not conflict with the account of polymorphism given here, though most of the ecological geneticists believed that evidence would gradually accumulate against his theory.

Sexual dimorphism

We meet genetic polymorphism daily, since our species (like most other eukaryotes) uses sexual reproductionSexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is the creation of a new organism by combining the genetic material of two organisms. There are two main processes during sexual reproduction; they are: meiosis, involving the halving of the number of chromosomes; and fertilization, involving the fusion of two gametes and the...

, and of course, the sexes are differentiated. However, even if the sexes were identical in superficial appearance, the division into two sexes is a dimorphism, albeit cryptic. This is because the phenotype

Phenotype

A phenotype is an organism's observable characteristics or traits: such as its morphology, development, biochemical or physiological properties, behavior, and products of behavior...

of an organism includes its sexual organs and its chromosomes, and all the behaviour associated with reproduction. So research into sexual dimorphism has addressed two issues: first, the advantage of sex in evolutionary terms; second, the role of visible sexual differentiation.

The system is relatively stable (with about half of the population of each sex) and heritable, usually by means of sex chromosomes. Every aspect of this everyday phenomenon bristles with questions for the theoretical biologist. Why is the ratio ~50/50? How could the evolution of sex

Evolution of sex

The evolution of sexual reproduction is currently described by several competing scientific hypotheses. All sexually reproducing organisms derive from a common ancestor which was a single celled eukaryotic species. Many protists reproduce sexually, as do the multicellular plants, animals, and fungi...

occur from an original situation of asexual reproduction, which has the advantage that every member of a species could reproduce? Why the visible differences between the sexes? These questions have engaged the attentions of biologists such as Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

, August Weismann

August Weismann

Friedrich Leopold August Weismann was a German evolutionary biologist. Ernst Mayr ranked him the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Charles Darwin...

, Ronald Fisher, George C. Williams

George C. Williams

Professor George Christopher Williams was an American evolutionary biologist.Williams was a professor emeritus of biology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He was best known for his vigorous critique of group selection. The work of Williams in this area, along with W. D...

, John Maynard Smith and W. D. Hamilton

W. D. Hamilton

William Donald Hamilton FRS was a British evolutionary biologist, widely recognised as one of the greatest evolutionary theorists of the 20th century....

, with varied success.

Of the many issues involved, there is widespread agreement on the following: the advantage of sexual and hermaphroditic reproduction

Hermaphrodite

In biology, a hermaphrodite is an organism that has reproductive organs normally associated with both male and female sexes.Many taxonomic groups of animals do not have separate sexes. In these groups, hermaphroditism is a normal condition, enabling a form of sexual reproduction in which both...

over asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a mode of reproduction by which offspring arise from a single parent, and inherit the genes of that parent only, it is reproduction which does not involve meiosis, ploidy reduction, or fertilization. A more stringent definition is agamogenesis which is reproduction without...

lies in the way recombination

Genetic recombination

Genetic recombination is a process by which a molecule of nucleic acid is broken and then joined to a different one. Recombination can occur between similar molecules of DNA, as in homologous recombination, or dissimilar molecules, as in non-homologous end joining. Recombination is a common method...

increases the genetic diversity

Genetic diversity

Genetic diversity, the level of biodiversity, refers to the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It is distinguished from genetic variability, which describes the tendency of genetic characteristics to vary....

of the ensuing population.p234ch7 The advantage of sexual reproduction over hermaphroditic is not so clear. In forms that have two separate sexes, same sex combinations are excluded from mating

Mating

In biology, mating is the pairing of opposite-sex or hermaphroditic organisms for copulation. In social animals, it also includes the raising of their offspring. Copulation is the union of the sex organs of two sexually reproducing animals for insemination and subsequent internal fertilization...

which decreases the amount of diversity compared with hermaphrodites by at least twice. So, why are almost all progressive species bi-sexual, considering the asexual process is more efficient and simple, whilst hermaphrodites produce a more diversified progeny? It has been suggested that differentiation into two sexes has evolutionary advantages allowing changes to concentrate in the male part of the population and at the same time preserving the existing genotype distribution in the females. This enables the population to better meet the challenges of infection

Infection

An infection is the colonization of a host organism by parasite species. Infecting parasites seek to use the host's resources to reproduce, often resulting in disease...

, parasitism

Parasitism

Parasitism is a type of symbiotic relationship between organisms of different species where one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. Traditionally parasite referred to organisms with lifestages that needed more than one host . These are now called macroparasites...

, predation

Predation

In ecology, predation describes a biological interaction where a predator feeds on its prey . Predators may or may not kill their prey prior to feeding on them, but the act of predation always results in the death of its prey and the eventual absorption of the prey's tissue through consumption...

and other hazards of the varied environment. (See also Evolution of sex

Evolution of sex

The evolution of sexual reproduction is currently described by several competing scientific hypotheses. All sexually reproducing organisms derive from a common ancestor which was a single celled eukaryotic species. Many protists reproduce sexually, as do the multicellular plants, animals, and fungi...

.)

Human polymorphisms

Apart from sexual dimorphism, there are many other examples of human genetic polymorphisms. Infectious disease has been a major factor in human mortality, and so has affected the evolution of human populations. Evidence is now strong that many polymorphisms are maintained in human populations by balancing selection.Human blood groups

All the common blood typeBlood type

A blood type is a classification of blood based on the presence or absence of inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells . These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins, or glycolipids, depending on the blood group system...

s, such as the ABO blood group system

ABO blood group system

The ABO blood group system is the most important blood type system in human blood transfusion. The associated anti-A antibodies and anti-B antibodies are usually IgM antibodies, which are usually produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food,...

, are genetic polymorphisms. Here we see a system where there are more than two morphs: the phenotype

Phenotype

A phenotype is an organism's observable characteristics or traits: such as its morphology, development, biochemical or physiological properties, behavior, and products of behavior...

s are A, B, AB and O are present in all human populations, but vary in proportion in different parts of the world. The phenotypes are controlled by multiple allele

Allele

An allele is one of two or more forms of a gene or a genetic locus . "Allel" is an abbreviation of allelomorph. Sometimes, different alleles can result in different observable phenotypic traits, such as different pigmentation...

s at one locus

Locus (genetics)

In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

. These polymorphisms are seemingly never eliminated by natural selection; the reason came from a study of disease statistics.

Statistical research has shown that the various phenotypes are more, or less, likely to suffer a variety of diseases. For example, an individual's susceptibility to cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

(and other diarrheal infections) is correlated with their blood type: those with type O blood are the most susceptible, while those with type AB are the most resistant. Between these two extremes are the A and B blood types, with type A being more resistant than type B. This suggests that the pleiotropic

Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences multiple phenotypic traits. Consequently, a mutation in a pleiotropic gene may have an effect on some or all traits simultaneously...

effects of the genes set up opposing selective forces, thus maintaining a balance. Geographical distribution of blood groups (the differences in gene frequency between populations) is broadly consistent with the classification of "races" developed by early anthropologists on the basis of visible features.

Sickle-cell anaemia

Such a balance is seen more simply in sickle-cell anaemiaSickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease , or sickle-cell anaemia or drepanocytosis, is an autosomal recessive genetic blood disorder with overdominance, characterized by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. Sickling decreases the cells' flexibility and results in a risk of various...

, which is found mostly in tropical populations in Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

and India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

. An individual homozygous for the recessive

Recessive

In genetics, the term "recessive gene" refers to an allele that causes a phenotype that is only seen in a homozygous genotype and never in a heterozygous genotype. Every person has two copies of every gene on autosomal chromosomes, one from mother and one from father...

sickle haemoglobin

Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein in the red blood cells of all vertebrates, with the exception of the fish family Channichthyidae, as well as the tissues of some invertebrates...

, HgbS, has a short expectancy of life, whereas the life expectancy of the standard haemoglobin (HgbA) homozygote and also the heterozygote is normal (though heterozygote individuals will suffer periodic problems). The sickle-cell variant survives in the population because the heterozygote is resistant to malaria and the malarial parasite

Plasmodium

Plasmodium is a genus of parasitic protists. Infection by these organisms is known as malaria. The genus Plasmodium was described in 1885 by Ettore Marchiafava and Angelo Celli. Currently over 200 species of this genus are recognized and new species continue to be described.Of the over 200 known...

kills a huge number of people each year. This is balancing selection

Balancing selection

Balancing selection refers to a number of selective processes by which multiple alleles are actively maintained in the gene pool of a population at frequencies above that of gene mutation. This usually happens when the heterozygotes for the alleles under consideration have a higher adaptive value...

or genetic polymorphism, balanced between fierce selection against homozygous sickle-cell sufferers, and selection against the standard HgbA homozygotes by malaria. The heterozygote has a permanent advantage (a higher fitness) so long as malaria exists; and it has existed as a human parasite

Parasitism

Parasitism is a type of symbiotic relationship between organisms of different species where one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. Traditionally parasite referred to organisms with lifestages that needed more than one host . These are now called macroparasites...

for a long time. Because the heterozygote survives, so does the HgbS allele

Allele

An allele is one of two or more forms of a gene or a genetic locus . "Allel" is an abbreviation of allelomorph. Sometimes, different alleles can result in different observable phenotypic traits, such as different pigmentation...

survive at a rate much higher than the mutation rate

Mutation rate

In genetics, the mutation rate is the chance of a mutation occurring in an organism or gene in each generation...

(see and refs in Sickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease

Sickle-cell disease , or sickle-cell anaemia or drepanocytosis, is an autosomal recessive genetic blood disorder with overdominance, characterized by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. Sickling decreases the cells' flexibility and results in a risk of various...

).

Duffy system

The Duffy antigenDuffy antigen system

Duffy antigen/chemokine receptor also known as Fy glycoprotein or CD234 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DARC gene....

is a protein located on the surface of red blood cells, encoded by the FY (DARC) gene

Gene

A gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

. The protein encoded by this gene is a non-specific receptor

Receptor (biochemistry)

In biochemistry, a receptor is a molecule found on the surface of a cell, which receives specific chemical signals from neighbouring cells or the wider environment within an organism...

for several chemokine

Chemokine

Chemokines are a family of small cytokines, or proteins secreted by cells. Their name is derived from their ability to induce directed chemotaxis in nearby responsive cells; they are chemotactic cytokines...

s, and is the known entry-point for the human malarial parasites Plasmodium vivax

Plasmodium vivax

Plasmodium vivax is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. The most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria, P. vivax is one of the four species of malarial parasite that commonly infect humans. It is less virulent than Plasmodium falciparum, which is the deadliest of the...

and Plasmodium knowlesi

Plasmodium knowlesi

Plasmodium knowlesi is a primate malaria parasite commonly found in Southeast Asia. It causes malaria in long-tailed macaques , but it may also infect humans, either naturally or artificially....

. Polymorphisms in this gene are the basis of the Duffy blood group system.

In humans, a mutant variant at a single site in the FY cis-regulatory region abolishes all expression of the gene in erythrocyte

Red blood cell

Red blood cells are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system...

precursors. As a result, homozygous mutants are strongly protected from infection by P. vivax, and a lower level of protection is conferred on heterozygotes. The variant has apparently arisen twice in geographically distinct human populations, in Africa and Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

. It has been driven to high frequencies on at least two haplotypic

Haplotype

A haplotype in genetics is a combination of alleles at adjacent locations on the chromosome that are transmitted together...

backgrounds within Africa. Recent work indicates a similar, but not identical, pattern exists in baboons (Papio cynocephalus

Yellow Baboon

The yellow baboon is a baboon from the Old World monkey family.Cynocephalus literally means "dog-head" in Greek due to the shape of its muzzle and head. It has a slim body with long arms and legs and a yellowish-brown hair. It resembles the Chacma baboon but is smaller and its muzzle is not as...

), which suffer a mosquito-carried malaria-like pathogen, Hepatocystis kochi. Researchers interpret this as a case of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution

Convergent evolution describes the acquisition of the same biological trait in unrelated lineages.The wing is a classic example of convergent evolution in action. Although their last common ancestor did not have wings, both birds and bats do, and are capable of powered flight. The wings are...

.

G6PD

G6PD (Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) human polymorphism is also implicated in malarial resistance. G6PD alleles with reduced activity are maintained at a high level in endemic malarial regions, despite reduced general viability. Variant A (with 85% activity) reaches 40% in sub-Saharan Africa, but is generally less than 1% outside Africa and the Middle East.Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosisCystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a recessive genetic disease affecting most critically the lungs, and also the pancreas, liver, and intestine...

, a congenital disorder

Congenital disorder

A congenital disorder, or congenital disease, is a condition existing at birth and often before birth, or that develops during the first month of life , regardless of causation...

which affects about one in 2000 children, is caused by a mutant form of the CF transmembrane regulator gene

Regulator gene

A regulator gene, regulator, or regulatory gene is a gene involved in controlling the expression of one or more other genes. A regulator gene may encode a protein, or it may work at the level of RNA, as in the case of genes encoding microRNAs....

, CFTR. The transmission is Mendelian

Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance is a scientific description of how hereditary characteristics are passed from parent organisms to their offspring; it underlies much of genetics...

: the normal gene is dominant, so all heterozygotes are healthy, but those who inherit two mutated genes have the condition. The mutated allele is present in about 1:25 of the population (mostly heterozygotes), which is much higher than expected from the rate of mutation alone. Sufferers from this disease have shortened life expectancy (and males are usually sterile if they survive), and the disease was effectively lethal in pre-modern societies. The incidence of the disease varies greatly between ethnic groups, but is highest in Caucasian

Caucasian race

The term Caucasian race has been used to denote the general physical type of some or all of the populations of Europe, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, Western Asia , Central Asia and South Asia...

populations.

Although over 1500 mutations are known in the CFTR gene, by far the most common mutant is DF508. This mutant is being kept at a high level in the population despite the lethal or near-lethal effects of the mutant homozygote. It seems that some kind of heterozygote advantage

Heterozygote advantage

A heterozygote advantage describes the case in which the heterozygote genotype has a higher relative fitness than either the homozygote dominant or homozygote recessive genotype. The specific case of heterozygote advantage is due to a single locus known as overdominance...

is operating. Early theories that the heterozygotes might enjoy increased fertility have not been borne out. Present indications are that the bacterium which causes typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

enters cells using CFTR, and experiments with mice suggest that heterozygotes are resistant to the disease. If the same were true in humans, then heterozygotes would have had an advantage during typhoid epidemic

Epidemic

In epidemiology, an epidemic , occurs when new cases of a certain disease, in a given human population, and during a given period, substantially exceed what is expected based on recent experience...

s. Cystic fibrosis is a prime target for gene therapy

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is the insertion, alteration, or removal of genes within an individual's cells and biological tissues to treat disease. It is a technique for correcting defective genes that are responsible for disease development...

research.

Human taste morphisms

A famous puzzle in human genetics is the genetic ability to taste phenylthiocarbamidePhenylthiocarbamide

Phenylthiocarbamide, also known as PTC, or phenylthiourea,is an organosulfur thiourea containing a phenyl ring.It has the unusual property that it either tastes very bitter or is virtually tasteless, depending on the genetic makeup of the taster...

(phenylthiourea or PTC), a morphism which was discovered in 1931. This substance, which to some of us is bitter, and to others tasteless, is of no great significance in itself, yet it is a genetic dimorphism. Because of its high frequency (which varies in different ethnic groups) it must be connected to some function of selective value. The ability to taste PTC itself is correlated with the ability to taste other bitter substances, many of which are toxic. Indeed, PTC itself is toxic, though not at the level of tasting it on litmus

Litmus

Litmus or litmus test may refer to:* Litmus test, a common pH test* Litmus , a test case management tool maintained by Mozilla* "Litmus" , an episode in the first season of the television series...

. Variation in PTC perception may reflect variation in dietary preferences throughout human evolution, and might correlate with susceptibility to diet-related diseases in modern populations. There is a statistical correlation between PTC tasting and liability to thyroid disease

Thyroid disease

-Hyper- and hypofunction:Imbalance in production of thyroid hormones arises from dysfunction of the thyroid gland itself, the pituitary gland, which produces thyroid-stimulating hormone , or the hypothalamus, which regulates the pituitary gland via thyrotropin-releasing hormone . Concentrations of...

.

Fisher, Ford and Huxley tested orangutan

Orangutan

Orangutans are the only exclusively Asian genus of extant great ape. The largest living arboreal animals, they have proportionally longer arms than the other, more terrestrial, great apes. They are among the most intelligent primates and use a variety of sophisticated tools, also making sleeping...

s and chimpanzee

Chimpanzee

Chimpanzee, sometimes colloquially chimp, is the common name for the two extant species of ape in the genus Pan. The Congo River forms the boundary between the native habitat of the two species:...

s for PTC perception with positive results, thus demonstrating the long-standing existence of this dimorphism. The recently identified PTC gene, which accounts for 85% of the tasting variance, has now been analysed for sequence variation with results which suggest selection is maintaining the morphism.

Lactose tolerance/intolerance

The ability to metabolize lactose, a sugar found in milk and other dairy products, is a prominent dimorphism that has been linked to recent human evolution.MHC molecules

The genes of the major histocompatibility complexMajor histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex is a cell surface molecule encoded by a large gene family in all vertebrates. MHC molecules mediate interactions of leukocytes, also called white blood cells , which are immune cells, with other leukocytes or body cells...

(MHC) are highly polymorphic, and this diversity plays a very important role in resistance to pathogens. This is true for other species as well.

The cuckoo

The intruded egg develops exceptionally quickly; when the newly-hatched cuckoo is only ten hours old, and still blind, it exhibits an urge to eject the other eggs or nestlings. It rolls them into a special depression on its back and heaves them out of the nest. The cuckoo nestling is apparently able to pressure the host adults for feeding by mimicking the cries of the host nestlings. The diversity of the cuckoo's eggs is extraordinary, the forms resembling those of its most usual hosts. In Britain these are:

- Meadow pipitMeadow PipitThe Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis, is a small passerine bird which breeds in much of the northern half of Europe and also northwestern Asia, from southeastern Greenland and Iceland east to just east of the Ural Mountains in Russia, and south to central France and Romania; there is also an isolated...

(Anthus pratensis): brown eggs speckled with darker brown. - European robinEuropean RobinThe European Robin , most commonly known in Anglophone Europe simply as the Robin, is a small insectivorous passerine bird that was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family , but is now considered to be an Old World flycatcher...

(Erithacus rubecula): whitish-grey eggs speckled with bright red. - Reed warblerReed WarblerThe Eurasian Reed Warbler, or just Reed Warbler, Acrocephalus scirpaceus, is an Old World warbler in the genus Acrocephalus. It breeds across Europe into temperate western Asia. It is migratory, wintering in sub-Saharan Africa....

(Acrocephalus scirpensis): light dull green eggs blotched with olive. - RedstartRedstartRedstarts are a group of small Old World birds. They were formerly classified in the thrush family , but are now known to be part of the Old World flycatcher family Muscicapidae...

(Phoenicurus phoenicurus): clear blue eggs. - Hedge sparrow (Prunella modularis): clear blue eggs, unmarked, not mimicked. This bird is an uncritical fosterer; it tolerates in its nest eggs that do not resemble its own.

Each female cuckoo lays one type only; the same type laid by her mother. In this way female cuckoos are divided into groups (known as gentes

Gens (behaviour)

In animal behaviour, a gens or host race is a host-specific lineage of a brood parasite species. Brood parasites such as cuckoos, which use multiple host species to raise their chicks, evolve different gentes, each one specific to its host species...

, singular gens), each parasitises the host to which it is adapted. The male cuckoo has its own territory, and mates with females from any gens; thus the population (all gentes) is interbreeding.

The standard explanation of how the inheritance of gens works is as follows. The egg colour is inherited by sex chromosome. In birds sex determination is ZZ/ZW, and unlike mammals, the heterogametic sex is the female. The determining gene (or super-gene) for the inheritance of egg colour is believed to be carried on the W chromosome, which is directly transmitted in the female line. The female behaviour in choosing the host species is set by imprinting

Imprinting (psychology)

Imprinting is the term used in psychology and ethology to describe any kind of phase-sensitive learning that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior...

after birth, a common mechanism in bird behaviour.

Ecologically, the system of multiple hosts protects host species from a critical reduction in numbers, and maximises the egg-laying capacity of the population of cuckoos. It also extends the range of habitats where the cuckoo eggs may be raised successfully. Detailed work on the Cuckoo started with E. Chance in 1922, and continues to the present day; in particular, the inheritance of gens is still a live issue.

Grove snail

The grove snail, Cepaea nemoralis, is famous for the rich polymorphism of its shell. The system is controlled by a series of multiple alleles. The shell colour series is brown (genetically the top dominant trait), dark pink, light pink, very pale pink, dark yellow and light yellow (the bottom or universal recessiveRecessive

In genetics, the term "recessive gene" refers to an allele that causes a phenotype that is only seen in a homozygous genotype and never in a heterozygous genotype. Every person has two copies of every gene on autosomal chromosomes, one from mother and one from father...

trait). Bands may be present or absent; and if present from one to five in number. Unbanded is the top dominant trait, and the forms of banding are controlled by modifier genes (see epistasis

Epistasis

In genetics, epistasis is the phenomenon where the effects of one gene are modified by one or several other genes, which are sometimes called modifier genes. The gene whose phenotype is expressed is called epistatic, while the phenotype altered or suppressed is called hypostatic...

).

Song Thrush

The Song Thrush is a thrush that breeds across much of Eurasia. It is also known in English dialects as throstle or mavis. It has brown upperparts and black-spotted cream or buff underparts and has three recognised subspecies...

Turdus philomelos, which breaks them open on thrush anvils (large stones). Here fragments accumulate, permitting researchers to analyse the snails taken. The thrushes hunt by sight, and capture selectively those forms which match the habitat least well. Snail colonies are found in woodland, hedgerows and grassland, and the predation determines the proportion of phenotypes (morphs) found in each colony.

Despite the predation, the polymorphism survives in almost all habitats, though the proportions of morphs varies considerably. The alleles controlling the polymorphism form a super-gene with linkage so close as to be nearly absolute. This control saves the population from a high proportion of undesirable recombinants, and it is hypothesised that selection has brought the loci concerned together.

To sum up, in this species predation by birds appears to be the main (but not the only) selective force driving the polymorphism. The snails live on heterogeneous backgrounds, and thrush are adept at detecting poor matches. The inheritance of physiological and cryptic diversity is preserved also by heterozygous advantage in the super-gene. Recent work has included the effect of shell colour on thermoregulation, and a wider selection of possible genetic influences is considered by Cook.

A similar system of genetic polymorphism occurs in the White-lipped Snail Cepaea hortensis, a close relative of the grove snail. In Iceland, where there are no song thrushes, a correlation has been established between temperature and colour forms. Banded and brown morphs reach higher temperatures than unbanded and yellow snails. This may be the basis of the physiological selection found in both species of snail.

Scarlet tiger moth

The scarlet tiger mothScarlet tiger moth

The Scarlet Tiger Moth is a colorful moth of Europe, Turkey, Transcaucasus, northern Iran. It belongs to the tiger moth family, Arctiidae....

Callimorpha (Panaxia) dominula (family Arctiidae

Arctiidae

Arctiidae is a large and diverse family of moths with around 11,000 species found all over the world, including 6,000 neotropical species. This family includes the groups commonly known as tiger moths , which usually have bright colours, footmen , lichen moths and wasp moths...

) occurs in continental Europe, western Asia and southern England. It is a day-flying moth, noxious-tasting, with brilliant warning colour in flight, but cryptic at rest. The moth is colonial in habit, and prefers marshy ground or hedgerows. The preferred food of the larvae is the herb Comfrey

Comfrey

Comfrey is an important herb in organic gardening. It is used as a fertilizer and also has many purported medicinal uses...

(Symphytum officinale). In England it has one generation per year.

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

, with three forms: the typical homozygote; the rare homozygote (bimacula) and the heterozygote (medionigra). It was studied there by Ford and later by Sheppard and their co-workers over many years. Data is available from 1939 to the present day, got by the usual field method of capture-mark-release-recapture and by genetic analysis from breeding in captivity. The records cover gene frequency and population-size for much of the twentieth century.

In this instance the genetics appears to be simple: two alleles at a single locus

Locus (genetics)

In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

, producing the three phenotypes. Total captures over 26 years 1939-64 came to 15,784 homozygous dominula (i.e. typica), 1,221 heterozygous medionigra and 28 homozygous bimacula. Now, assuming equal viability of the genotypes 1,209 heterozygotes would be expected, so the field results do not suggest any heterozygous advantage. It was Sheppard who found that the polymorphism is maintained by selective mating: each genotype preferentially mates with other morphs. This is sufficient to maintain the system despite the fact that in this case the heterozygote has slightly lower viability.

Peppered moth

The peppered moth, Biston betulariaPeppered moth

The peppered moth is a temperate species of night-flying moth. Peppered moth evolution is often used by educators as an example of natural selection.- Distribution :...

, is justly famous as an example of a population responding in a heritable way to a significant change in their ecological circumstances. E.B. Ford described peppered moth evolution

Peppered moth evolution

The evolution of the peppered moth over the last two hundred years has been studied in detail. Originally, the vast majority of peppered moths had light colouration, which effectively camouflaged them against the light-coloured trees and lichens which they rested upon...

as "one of the most striking, though not the most profound, evolutionary changes ever actually witnessed in nature".

Although the moths are cryptically camouflage

Camouflage

Camouflage is a method of concealment that allows an otherwise visible animal, military vehicle, or other object to remain unnoticed, by blending with its environment. Examples include a leopard's spotted coat, the battledress of a modern soldier and a leaf-mimic butterfly...

d and rest during the day in unexposed positions on trees, they are predated by birds hunting by sight. The original camouflage (or crypsis

Crypsis

In ecology, crypsis is the ability of an organism to avoid observation or detection by other organisms. It may be either a predation strategy or an antipredator adaptation, and methods include camouflage, nocturnality, subterranean lifestyle, transparency, and mimicry...

) seems near-perfect against a background of lichen

Lichen

Lichens are composite organisms consisting of a symbiotic organism composed of a fungus with a photosynthetic partner , usually either a green alga or cyanobacterium...

growing on trees. The sudden growth of industrial pollution in the nineteenth century changed the effectiveness of the moths' camouflage: the trees became blackened by soot, and the lichen died off. In 1848 a dark version of this moth was found in the Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

area. By 1895 98% of the Peppered Moths in this area were black. This was a rapid change for a species that has only one generation a year.

Locus (genetics)

In the fields of genetics and genetic computation, a locus is the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence on a chromosome. A variant of the DNA sequence at a given locus is called an allele. The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a genetic map...

, with the carbonaria being dominant. There is also an intermediate or semi-melanic morph insularia, controlled by other alleles (see Majerus 1998).

A key fact, not realised initially, is the advantage of the heterozygotes, which survive better than either of the homozygotes. This affects the caterpillars as well as the moths, in spite of the caterpillars being monomorphic in appearance (they are twig mimics). In practice heterozygote advantage

Heterozygote advantage

A heterozygote advantage describes the case in which the heterozygote genotype has a higher relative fitness than either the homozygote dominant or homozygote recessive genotype. The specific case of heterozygote advantage is due to a single locus known as overdominance...

puts a limit to the effect of selection, since neither homozygote can reach 100% of the population. For this reason, it is likely that the carbonaria allele was in the population originally, pre-industrialisation, at a low level. With the recent reduction in pollution, the balance between the forms has already shifted back significantly.

Another interesting feature is that the carbonaria had noticeably darkened after about a century. This was seen quite clearly when specimens collected about 1880 were compared with specimens collected more recently: clearly the dark morph has been adjusted by the strong selection acting on the gene complex. This might happen if a more extreme allele was available at the same locus; or genes at other loci might act as modifiers. We do not, of course, know anything about the genetics of the original melanics from the nineteenth century.

This type of industrial melanism has only affected such moths as obtain protection from insect-eating birds by resting on trees where they are concealed by an accurate resemblance to their background (over 100 species of moth in Britain with melanic forms were known by 1980). No species which hide during the day, for instance, among dead leaves, is affected, nor has the melanic change been observed among butterflies.

This is, as shown in many textbooks, "evolution in action". Much of the early work was done by Bernard Kettlewell

Bernard Kettlewell

Henry Bernard Davis Kettlewell was a British geneticist, lepidopterist and medical doctor, who carried out research into the influence of industrial melanism on natural selection in moths, showing why moths are darker in polluted areas.-Early life:Kettlewell was born in Howden, Yorkshire, and...

, whose methods came under scrutiny later on. The entomologist Michael Majerus

Michael Majerus

Michael Eugene Nicolas Majerus was a geneticist and Professor of Ecology at Clare College, Cambridge, an enthusiast who became a world authority in his field of evolutionary biology. He was widely noted for his work on moths and ladybirds and as an advocate of the science of evolution...

discussed criticisms made of Kettlewell's experimental methods in his 1998 book Melanism: Evolution in Action

Melanism: Evolution in Action