Rae-Richardson Arctic Expedition

Encyclopedia

.jpg)

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

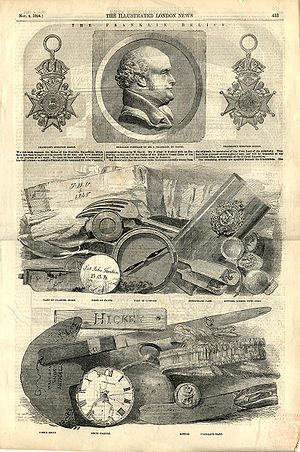

effort to determine the fate of the lost Franklin Polar Expedition

Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a doomed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845. A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Franklin had served on three previous Arctic expeditions, the latter two as commanding officer...

. Led overland by Sir John Richardson

John Richardson (naturalist)

Sir John Richardson was a Scottish naval surgeon, naturalist and arctic explorer.Richardson was born at Dumfries. He studied medicine at Edinburgh University, and became a surgeon in the navy in 1807. He traveled with John Franklin in search of the Northwest Passage on the Coppermine Expedition of...

and John Rae

John Rae (explorer)

John Rae was a Scottish doctor who explored Northern Canada, surveyed parts of the Northwest Passage and reported the fate of the Franklin Expedition....

, the team explored the accessible areas along Franklin's

John Franklin

Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin KCH FRGS RN was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. Franklin also served as governor of Tasmania for several years. In his last expedition, he disappeared while attempting to chart and navigate a section of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic...

proposed route near the Mackenzie

Mackenzie River

The Mackenzie River is the largest river system in Canada. It flows through a vast, isolated region of forest and tundra entirely within the country's Northwest Territories, although its many tributaries reach into four other Canadian provinces and territories...

and Coppermine

Coppermine River

The Coppermine River is a river in the North Slave and Kitikmeot regions of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada. It is long. It rises in Lac de Gras, a small lake near Great Slave Lake and flows generally north to Coronation Gulf, an arm of the Arctic Ocean...

rivers. Although no direct contact with Franklin's forces was achieved, Rae later interviewed the Inuit

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Canada , Denmark , Russia and the United States . Inuit means “the people” in the Inuktitut language...

of the region and obtained credible accounts that the desperate remnants of Franklin's team had resorted to cannibalism. This revelation was so unpopular that Rae was effectively shunned by the British Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

and popular opinion, and the search for Franklin continued for several years.

Preparation

As early as 1847, it was believed that Franklin's forces were likely icebound. The British Admiralty devised a three-pronged rescue effort to address the three most likely escape routes for Franklin - Lancaster SoundLancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound is a body of water in Qikiqtaaluk, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern portion of the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin Bay; to the west lies Viscount Melville Sound...

, the Mackenzie River (to the settlement of the Hudson's Bay Company

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company , abbreviated HBC, or "The Bay" is the oldest commercial corporation in North America and one of the oldest in the world. A fur trading business for much of its existence, today Hudson's Bay Company owns and operates retail stores throughout Canada...

fur trade

Fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of world market for in the early modern period furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most valued...

rs), and Beering's Straits

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

. Sir John Richardson, who had participated in earlier Arctic

Arctic

The Arctic is a region located at the northern-most part of the Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean and parts of Canada, Russia, Greenland, the United States, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. The Arctic region consists of a vast, ice-covered ocean, surrounded by treeless permafrost...

expeditions with Franklin himself, took the objective of the Mackenzie River, tracing the coast between the Mackenzie and Coppermine rivers, as well as the shores of Victoria Island and the Wollaston Peninsula

Wollaston Peninsula

The Wollaston Peninsula is located on southwestern Victoria Island, Canada. Most of the peninsula lies in Nunavut's Kitikmeot Region, bordered by the Dolphin and Union Strait to the south. A smaller portion lies within the Northwest Territories's Inuvik Region, bordered by the Amundsen Gulf to the...

, then known as Victoria Land and Wollaston Lands, in an overland expedition.

Assuming the existence of an unknown but likely passage between these lands, it would have been the most direct route of travel consistent with Franklin's original exploration orders. John Rae of the Hudson's Bay Company was attached to this effort. Rae had 15 years of experience in the region and regarded the indigenous people with uncommon respect. It was planned that the expedition would extend their search by wintering in the area of Great Bear Lake

Great Bear Lake

Great Bear Lake is the largest lake entirely within Canada , the third or fourth largest in North America, and the seventh or eighth largest in the world...

.

Recent seasons of hunting in Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land, or Prince Rupert's Land, was a territory in British North America, consisting of the Hudson Bay drainage basin that was nominally owned by the Hudson's Bay Company for 200 years from 1670 to 1870, although numerous aboriginal groups lived in the same territory and disputed the...

(as the Hudson's Bay Company area was called) had been poor, so additional provisions were transported to the area in 1847, prior to Richardson's departure. These consisted of over 17000 lb (7,711.1 kg) of canned pemmican

Pemmican

Pemmican is a concentrated mixture of fat and protein used as a nutritious food. The word comes from the Cree word pimîhkân, which itself is derived from the word pimî, "fat, grease". It was invented by the native peoples of North America...

. Four half-ton boats were constructed (at Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

Dock Yard and Camper's Yard

Camper and Nicholsons

Camper and Nicholsons are the oldest leisure marine company in the world, producing and managing yachts for the world's richest people.As Camper and Nicholsons was founded at Gosport, Hampshire before organised seawater yachting had even started, John Nicholson of the founding family once overheard...

at Gosport

Gosport

Gosport is a town, district and borough situated on the south coast of England, within the county of Hampshire. It has approximately 80,000 permanent residents with a further 5,000-10,000 during the summer months...

) for the river navigation, about 30 by each, but designed so that the two smaller boats nest inside the two larger boats during shipping. Five seamen and fifteen sapper

Sapper

A sapper, pioneer or combat engineer is a combatant soldier who performs a wide variety of combat engineering duties, typically including, but not limited to, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, demolitions, field defences, general construction and building, as well as road and airfield...

s and miners were selected as the expedition crew, many also skilled in carpentry, blacksmithing and engineering. The company's men and supplies departed England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

on June 15, 1847, making way for Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay , sometimes called Hudson's Bay, is a large body of saltwater in northeastern Canada. It drains a very large area, about , that includes parts of Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, most of Manitoba, southeastern Nunavut, as well as parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota,...

.

Ice in the Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait links the Atlantic Ocean to Hudson Bay in Canada. It lies between Baffin Island and the northern coast of Quebec, its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley and Resolution Island. It is long...

s delayed the supply and crew landing until September 8, while Richardson completed his preparations in England. The Hudson's Bay Company provided transport of additional supply caches along their proposed route. Workers were deployed to fish and cut firewood in anticipation of the expedition. Richardson and Rae set out from Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

on March 25, 1848, landed in New York

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

on April 10, and reaching Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

four days later. Two canoes, crewed mainly by Iroquois

Iroquois

The Iroquois , also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse", are an association of several tribes of indigenous people of North America...

and Chippewa, delivered Richardson, Rae, and their personal equipment to Cumberland House

Cumberland House, Saskatchewan

Cumberland House is a village in Census Division No. 18 in north-eastern Saskatchewan, Canada on the Saskatchewan River. It is the oldest community in Saskatchewan and has a population of about 2000 people...

| on the Saskatchewan River

Saskatchewan River

The Saskatchewan River is a major river in Canada, approximately long, flowing roughly eastward across Saskatchewan and Manitoba to empty into Lake Winnipeg...

on June 13. Travelling by canoe and portage

Portage

Portage or portaging refers to the practice of carrying watercraft or cargo over land to avoid river obstacles, or between two bodies of water. A place where this carrying occurs is also called a portage; a person doing the carrying is called a porter.The English word portage is derived from the...

, Richardson and Rae met the advance party at Methy Portage

Methye Portage

The Methye Portage or Portage La Loche in northwestern Saskatchewan was one of the most important portages in the old fur-trade route across Canada. It connected the Mackenzie River basin to rivers that ran east to the Atlantic. It was reached by Peter Pond in 1778 and abandoned in 1883 when...

on June 28, continuing down the Slave River

Slave River

The Slave River is a Canadian river that flows from Lake Athabasca in northeastern Alberta and empties into Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories....

with them until mid-July, reaching Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake

Great Slave Lake

Great Slave Lake is the second-largest lake in the Northwest Territories of Canada , the deepest lake in North America at , and the ninth-largest lake in the world. It is long and wide. It covers an area of in the southern part of the territory. Its given volume ranges from to and up to ...

, source of the Mackenzie River, on the 17th.

Reaching the winter encampment

Continuing through areas populated by several native tribesFirst Nations

First Nations is a term that collectively refers to various Aboriginal peoples in Canada who are neither Inuit nor Métis. There are currently over 630 recognised First Nations governments or bands spread across Canada, roughly half of which are in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia. The...

, they passed the tree line on August 2. The party was occasionally harassed by groups of Inuit aboard kayak

Kayak

A kayak is a small, relatively narrow, human-powered boat primarily designed to be manually propelled by means of a double blade paddle.The traditional kayak has a covered deck and one or more cockpits, each seating one paddler...

and umiak

Umiak

The umiak, umialak, umiaq, umiac, oomiac or oomiak is a type of boat used by Eskimo people, both Yupik and Inuit, and was originally found in all coastal areas from Siberia to Greenland. First arising in Thule times, it has traditionally been used in summer to move people and possessions to...

, but successfully suppressed the occasional aggressive posturing and developed good trading relations. These Inuit were interviewed but denied having seen any Europeans or ships, even as far back as Rae's trip through the area during the Ross

John Ross (Arctic explorer)

Sir John Ross, CB, was a Scottish rear admiral and Arctic explorer.Ross was the son of the Rev. Andrew Ross, minister of Inch, near Stranraer in Scotland. In 1786, aged only nine, he joined the Royal Navy as an apprentice. He served in the Mediterranean until 1789 and then in the English Channel...

Expedition of 1826. They continued on, hunting as they went, past Franklin Bay

Franklin Bay

Franklin Bay is a large inlet in the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is a southern arm of the Amundsen Gulf, southeastern Beaufort Sea. The bay measures long, and wide at its mouth. The Parry Peninsula is to the east, and its southern area is called Langton Bay.Franklin Bay receives the...

and Cape Parry

Cape Parry

Cape Parry is a headland in Canada's Northwest Territories. Located at the northern tip of the Parry Peninsula, it projects into Amundsen Gulf, from the North Pole. The nearest settlement is Paulatuk, to the south, and Fiji Island is located to the west...

, where they first encountered drifting pack ice

Drift ice

Drift ice is ice that floats on the surface of the water in cold regions, as opposed to fast ice, which is attached to a shore. Usually drift ice is carried along by winds and sea currents, hence its name, "drift ice"....

. Their progress slowed during the rest of the month, as wind, winter and ice often worked against them.

By the end of August, they had found a channel through the ice leading towards the Coppermine River, but the ice prevented them from reaching their autumn goal of Wollaston Land by water. Information gathering, trade and assistance continued through regular encounters with groups of Inuit. Continuing overland, they crossed the Richardson River

Richardson River

The Richardson River is a waterway that flows into Richardson Bay, Coronation Gulf in the northern Canadian territory of Nunavut. Its mouth is situated northwest of Kugluktuk, Nunavut. The Rae River is away....

in small groups using a portable Halkett boat

Halkett boat

A Halkett boat is a type of lightweight inflatable boat designed by during the 1840s. Halkett had long been interested in the difficulties of travelling in the Canadian Arctic, and the problems involved in designing boats light enough to be carried over arduous terrain, but robust enough to be...

on September 5. As the travelling wore on, they discarded equipment to lighten their loads. By September 15, they reached the advanced party which had already begun construction of winter quarters, named Fort Confidence

Fort Confidence, Northwest Territories

Fort Confidence, located at the mouth of the Dease River on the eastern tip of the Dease Arm of Great Bear Lake, Northwest Territories, was a Hudson's Bay Company post built in 1837 by Peter Warren Dease and Thomas Simpson during exploration of the Great Bear Lake and Coppermine River area, serving...

, and accumulation of winter stores. Here they passed the winter, periodically hunting, fishing and trading with the local Inuit to extend their rations. Throughout the winter Rae explored the lands between the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers. During December, the low temperature of -60 F was observed. By late May, the snow was melting and seasonal wildlife had begun to return.

Rae's summer 1849 expedition

With only one boat available, it was decided that Rae should continue the search without Richardson's direct involvement. Rae began staging supply depots and advance hunters in April by dog sledDog sled

A dog sled is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing.-History:...

. One June 7 Rae set out with a crew of six men, including two Cree

Cree

The Cree are one of the largest groups of First Nations / Native Americans in North America, with 200,000 members living in Canada. In Canada, the major proportion of Cree live north and west of Lake Superior, in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories, although...

Indians and an Inuk named Albert One-eye, to complete the exploration of the Coppermine River to the Arctic Ocean

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions...

and the coasts of Wollaston and Victoria Lands in search of Franklin. Initial progress over the frozen Dease River was slowly made by sledge. They reached the open waters near Point Mackenzie on July 14 at 67° 51' 19" N.

Here they were visited by seven Inuit, who reported that the natives of Wollaston Land had not seen any Europeans, boats, or ships. On the 16th, they reached Back's Inlet, and spent three days with these Inuit hosts, mapping the region. Poor weather and ice slowed their progress along the coast, and they finally made camp at 68° 24' 35" N. until conditions permitted travel. They finally pushed off from the coast into ice-filled waters on August 19. Although some halting progress was made through the pack ice, by the 23rd they resolved to abandon their goal of reaching Wollaston Land. The return to their base was difficult, and a portaging accident claimed the life of the Inuk, Albert, and their only boat at Bloody Falls

Bloody Falls

Bloody Falls is a waterfall in the Kugluk/Bloody Falls Territorial Park and is the site of the Bloody Falls Massacre and the murder of two priests by Copper Inuit Uloqsaq and Sinnisiak in 1913...

, the only fatality during Rae's exploration. They continued back across land, reaching the Coppermine River on the 29th, returning to Fort Confidence two days later.

Concurrently, the same poor conditions prevented the expedition of Ross from reaching the Coppermine River from the north. The following summer, Rae left instructions to the local natives to prepare for a possible meeting with Ross in 1850.

Richardson's return

Richardson's main party left Fort Confidence on May 7, a full month before Rae set out for Wollaston Land. Travel was primarily by boat, as the warming conditions did not support much sledging. They camped on the shores of Great Bear RiverGreat Bear River

The -long Great Bear River, which drains the Great Bear Lake westward through marshes into the Mackenzie River, forms an important transportation link during its four ice-free months. It originates at south-west bay of the lake. The river has irregular meander pattern wide channel with average depth...

for a month, awaiting a barge to ship their supplies. By June 8 they learned that the ice would not permit the barge to reach them, and the party set out on foot along the river.

By June 14, they had reached Fort Simpson, where they stayed until the 25th. They continued on through August and September, reaching Sault Ste. Marie

Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

Sault Ste. Marie is a city on the St. Marys River in Algoma District, Ontario, Canada. It is the third largest city in Northern Ontario, after Sudbury and Thunder Bay, with a population of 74,948. The community was founded as a French religious mission: Sault either means "jump" or "rapids" in...

on September 25, where a steam vessel provided further transport to Lake Huron

Lake Huron

Lake Huron is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. Hydrologically, it comprises the larger portion of Lake Michigan-Huron. It is bounded on the east by the Canadian province of Ontario and on the west by the state of Michigan in the United States...

. Richardson returned to Liverpool on November 6, 1849.

Rae's continued search

Rae continued his geographical survey and search for Franklin for the next several years on behalf of the Hudson's Bay Company, establishing a base at Fort Confidence on Great Bear Lake beginning in 1850. By the end of 1851, he had completed a survey of the southern shore of Wollaston Land. During the harsh winters, they shared their scarce provisions with the local Inuit, strengthening the bonds of cooperation, and none of the expedition members perished. During these expeditions, Rae continued to interview the local natives, but none had any reports of possible knowledge of Franklin's expedition, and no material evidence was discovered.In the spring of 1853, Rae returned to Back's Great Fish River, proceeding north-east from its mouth to extend the survey of Boothia. Here, he encountered Inuit in possession of objects he recognized as belonging to the Franklin expedition. Rae purchased as many of the objects as he could. Interviewing others in the area revealed that the Inuit had encountered the remnants of Franklin's crews in the spring of 1850.

Franklin's fate

Repulse Bay, Nunavut

Repulse Bay is an Inuit hamlet located on the shore of Hudson Bay, Kivalliq Region, in Nunavut, Canada.-Location and wildlife:The hamlet is located exactly on the Arctic Circle, on the north shore of Repulse Bay and on the south shore of the Rae Isthmus. Transport to the community is provided...

to the Secretary of the Admiralty:

Rae subsequently abandoned the task of completing the charting of the area, instead focusing on responding to the communications of those interested in Franklin's fate. He returned to England on October 22 to find the Admiralty had released his private communication to the press. Published in the London Times on October 23, it arousing much public distress and anger.

Legacy

In addition to establishing the final fate of Franklin's lost expedition, Rae completed an extensive survey of the west coast of BoothiaBoothia Peninsula

Boothia Peninsula is a large peninsula in Nunavut's northern Canadian Arctic, south of Somerset Island. The northern part, Murchison Promontory, is the northernmost point of mainland Canada, and thus North America....

, and proved once and for all that King William's Land was in fact an island. His furthest northward penetration near Cape Porter was set at 60° 5' N.

Rae's assertion of cannibalism was sufficiently unpleasant to cause him to be spurned publicly by Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

on behalf of Franklin's widow. Responding only a week after the details were published, Dickens rejected the reliability of the Inuit testimony, which led to a series of seven articles between Dickens, Rae and Henry Morley

Henry Morley

Henry Forster Morley was a writer on English literature and one of the earliest Professors of English Literature.-Life:...

debating the matter.

Other searchers for Franklin were granted knighthoods for their service, but Rae was not. Ultimately, he did collect a £10,000 reward for resolving the Franklin question, but by then he had been largely omitted from the picture, to be largely forgotten by history. Despite the fact that Francis Leopold McClintock

Francis Leopold McClintock

Admiral Sir Francis Leopold McClintock or Francis Leopold M'Clintock KCB, FRS was an Irish explorer in the British Royal Navy who is known for his discoveries in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.-Biography:...

located skeletal evidence on King William Island that supported Rae's account, he was never forgiven for delivering the bad news. Rae retired from exploration a short time later, and ultimately his contributions as an explorer were recognized when he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

in 1880.

Rae Strait

Rae Strait

Rae Strait, named after Arctic explorer John Rae, is a small strait in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula on the mainland to the east.-Source:* at the Atlas of Canada...

(between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula), Rae Isthmus

Melville Peninsula

Melville Peninsula is a large peninsula in the Canadian Arctic. Since 1999, it has been part of Nunavut. Before that, it was part of the District of Franklin. It's separated from Southampton Island by Frozen Strait. The narrow isthmus connecting the peninsula to the mainland is styled the “Rae...

, Rae River

Rae River

The Rae River is a waterway that flows from Akuliakattak Lake into Richardson Bay, Coronation Gulf. Its mouth is situated northwest of Kugluktuk, Nunavut...

, all in Nunavut

Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and newest federal territory of Canada; it was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the Nunavut Act and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act, though the actual boundaries had been established in 1993...

Mount Rae

Mount Rae

Mount Rae is a mountain located on the east side of Highway 40 between Elbow Pass and the Ptarmigan Cirque in the Canadian Rockies of Alberta. Mount Rae was named after John Rae, explorer of Northern Canada, in 1859....

(Alberta

Alberta

Alberta is a province of Canada. It had an estimated population of 3.7 million in 2010 making it the most populous of Canada's three prairie provinces...

), Fort Rae and the village of Rae-Edzo (now Behchoko), Northwest Territories

Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal territory of Canada.Located in northern Canada, the territory borders Canada's two other territories, Yukon to the west and Nunavut to the east, and three provinces: British Columbia to the southwest, and Alberta and Saskatchewan to the south...

were all named for Rae.