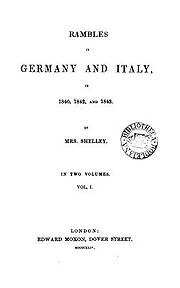

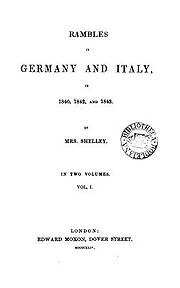

Rambles in Germany and Italy

Encyclopedia

Rambles in Germany and Italy, in 1840, 1842, and 1843 is a travel narrative

by the British Romantic

author Mary Shelley

. Issued in 1844, it is her last published work. Published in two volumes, the text describes two European trips that Mary Shelley took with her son, Percy Florence Shelley

, and several of his university friends. Mary Shelley had lived in Italy with her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley

, between 1818 and 1823. For her, Italy was associated with both joy and grief: she had written much while there but she had also lost her husband and two of her children. Thus, although she was anxious to return, the trip was tinged with sorrow. Shelley describes her journey as a pilgrimage

, which will help cure her depression.

At the end of the second trip, Mary Shelley spent time in Paris and associated herself with the "Young Italy

" movement, Italian exiles who were in favour of Italian independence and unification. One revolutionary in particular attracted her: Ferdinando Gatteschi. To assist him financially, Shelley decided to publish Rambles. However, Gatteschi became discontented with Shelley's assistance and tried to blackmail her. She was forced to obtain her personal letters from Gatteschi through the intervention of the French police.

Shelley differentiates her travel book from others by presenting her material from what she describes as "a political point of view". In so doing, she challenges the early nineteenth-century convention that it was improper for women to write about politics, following in the tradition of her mother, Mary Wollstonecroft, and Lady Morgan

. Shelley's aim was to arouse sympathy in England for Italian revolutionaries, such as Gatteschi. She rails against the imperial rule of Austria

and France over Italy and criticises the domination of the Catholic Church. She describes the Italians as having an untapped potential for greatness and a desire for freedom.

Although Shelley herself thought the work "poor", it found favour with reviewers who praised its independence of thought, wit, and feeling. Shelley's political commentary on Italy was specifically singled out for praise, particularly since it was written by a woman. However, for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Shelley was usually known only as the author of Frankenstein

and the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Rambles was not reprinted until the rise of feminist literary criticism

in the 1970s provoked a wider interest in Shelley's entire corpus.

From the Middle Ages

From the Middle Ages

until the end of the nineteenth century, Italy was divided into many small duchies and city-state

s, some of which were autonomous and some of which were controlled by Austria, France, Spain, or the Papacy. These multifarious governments and the diversity of Italian dialects spoken on the peninsula caused residents to identify as "Romans" or "Venetians", for example, rather than as "Italians". (It was not until the late nineteenth century that Tuscan Italian

became the national language.) When Napoleon conquered parts of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars

(1792–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars

(1803–15), he unified many of the smaller principalities; he centralised the governments and built roads and communication networks that helped to break down the barriers between and among Italians. Not all Italians welcomed French rule, however; Giuseppe Capo Biaco founded a secret society called the Carbonari

to resist both French rule and the Roman Catholic Church. After Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo

in 1815 and the Congress of Vienna

returned state authority to the Austrians, the Carbonari continued their resistance. The Carbonari led revolts in Naples

and Piedmont

in 1820 and 1821 and in Bologna

, the Papal States

, Parma

, and Modena

in the 1830s. After the failure of these revolts, Giuseppe Mazzini

, a Carbonaro who was exiled from Italy, founded the "Young Italy" group to work toward the unification of Italy, to establish a democratic republic, and to force non-Italian states to relinquish authority on the peninsula. By 1833, 60,000 people had joined the movement. These nationalist revolutionaries, with foreign support, attempted, but failed, to overthrow the Austrians in Genoa

and Turin

in 1833 and Calabria

in 1844. Italian unification

, or Risorgimento, was finally achieved in 1870 under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi

.

had lived in Italy from 1818 to 1823. Although Percy Shelley and two of their four children died there, Italy became for Mary Shelley "a country which memory painted as paradise", as she put it. The couple's Italian years were a time of intense intellectual and creative activity. While Percy composed a series of major poems, Mary wrote the autobiographical novel Matilda

, the historical novel

Valperga

, and the plays Proserpine

and Midas

. Mary Shelley had always wanted to return to Italy and she excitedly planned her 1840 trip. However, the return was painful as she was constantly reminded of Percy Shelley.

In June 1840, Mary Shelley, Percy Florence

(her one surviving child), and a few of his friends—George Defell, Julian Robinson, and Robert Leslie Ellis

—began their European tour. They traveled to Paris

and then to Metz

. From there, they went down the Moselle River

by boat to Coblenz and then up the Rhine River to Mainz

, Frankfurt

, Heidelberg

, Baden-Baden

, Freiburg

, Schaffhausen

, Zürich

, the Splügen

, and Chiavenna. Feeling ill, Shelley rested at a spa in Baden-Baden; she had wracking pains in her head and "convulsive shudders", symptoms of the meningioma

that would eventually kill her. This stop dismayed Percy Florence and his friends, as it provided no entertainment for them; moreover, since none of them spoke German, the group was forced to remain together. After crossing Switzerland by carriage and railway, the group spent two months at Lake Como

, where Mary relaxed and reminisced about how she and Percy had almost rented a villa with Lord Byron at the lake one summer. The group then travelled on to Milan

, and from there, Percy Florence and his friends soon left for Cambridge

to take their university finals. Mary Shelley remained, waiting for funds to complete her journey. In September, she returned to England via Geneva

and Paris. Upon her return, she became depressed and could not write: "[in Italy] I might live – as once I lived—hoping—loving—aspiring enjoying...I am placid now, & the days go by – I am happy in Percy [Florence's] society & health – but no adjuncts...gild the quiet hours & dulness [sic] creeps over my intellect". Despite this lethargy, however, she did manage to publish a second edition of Percy Shelley’s prose and began working on another edition of his poetry.

, Cologne

, Coblenz, Mainz, Frankfurt, Kissingen, Berlin

, Dresden

, Prague

, Salzburg

, the Tyrol

, Innsbruck

, Riva

, Verona

, Venice

, Florence

, and Rome

. In Rome, Mary Shelley toured museums with the French art critic Alex Rio; Percy Florence was unimpressed with the culture and refused to see the art, infuriating his mother, who spent an increasing amount of her time seeing the country with Knox instead. She also paid numerous visits to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s grave in Rome

. After two months in the Sorrento Peninsula, the group was short of money; Percy Florence and his friends returned home while Mary Shelley went on to Paris.

In Paris, Mary Shelley associated with many of the Italian expatriates who were part of the "Young Italy" movement. Her recent travels had made her particularly sympathetic to their revolutionary message. One Italian patriot captivated her in particular: Ferdinando Gatteschi, a smart, handsome, would-be writer. He was young—not yet 30—and in exile, following his participation in a failed Carbonari rebellion against Austria in 1830–31. Shelley was fascinated by Gatteschi; she described him as "a hero & an angel & martyr". Jeanne Moskal, the most recent editor of Rambles, argues that Mary Shelley was attracted to Gatteschi because he resembled Percy Shelley: he was an aristocratic writer who had been cast off by his parents for his liberalism. Moskal argues that "the strength of [Shelley’s] devotion overturned her previous resolve not to publish again".

At the end of September 1843, Mary Shelley proposed to her publisher, Edward Moxon

, that she write a travel book based on her 1840 and 1842 Continental journeys. Interested in assisting Gatteschi, she wrote to Moxon that she was writing "for a purpose most urgent & desirable". She described the work as "light", "personal", and "amusing". Moxon agreed to her proposal and advanced her £60, which she promised to return if fewer than 300 copies of the work were sold. (She subsequently gave this same amount to Gatteschi.) By the end of January 1844, Shelley had already completed most of the first volume. As Sunstein writes, "once started on Rambles, she worked fast and with pleasure, but her head and nerves were bad at times, and her eyes got so weak and inflamed that she wrote only until noon." She left Paris at the end of January and returned to London, still infatuated with Gatteschi. The death of Sir Timothy Shelley, Percy Florence's grandfather, in April 1844, delayed the completion of the work. However, with material from Gatteschi on the Ancona

uprising of 1831 and research help from German-speaking friends, Shelley finished. The text was largely drawn from correspondence written during her travels to her step-sister Claire Clairmont

. Mary Shelley’s last published work, which was dedicated to the travel writer and poet Samuel Rogers

, came out on 1 August 1844.

Despite Mary Shelley’s attempts to assist Gatteschi financially, he tried to blackmail her one year later in 1845 using indiscreet letters she had written. After not hearing from Gatteschi for months, she received threatening letters, which claimed that she had promised him financial success and even possibly marriage. He claimed that her letters would demonstrate this. The contents of Mary Shelley’s letters are unknown as they were later destroyed, but she must have felt some danger, for she took great pains to recover the letters and wrote agonised letters to her friends: "[The letters] were written with an open heart – & contain details with regard to my past history, which it [would] destroy me for ever if they ever saw light." Shelley turned to Alexander Knox for help. After obtaining help from the British government, he travelled to Paris and had the Paris police seize Gatteschi’s correspondence. Implying that Gatteschi was a danger to the state, Knox and the Paris police called upon the cabinet noir

system in order to retrieve the letters. On 11 October, Le National

and Le Constitutionnel

reported in outrage that Gatteschi’s personal papers were seized because he was a suspected revolutionary. Mary wrote to Claire that "It is an awful power this seizure", but she did not regret using it. After Knox retrieved her letters, he burned them. Shelley spent £250 of her own money to finance the operation. She was embarrassed by the entire incident.

, Mary Shelley charts her travels through Europe during 1840 and her reflections on accommodations, scenery, peasants, economic relationships between the classes, art, literature, and memories of her 1814 and 1816 journeys (recorded in History of a Six Weeks' Tour

(1817)). In the first letter, she muses on her return to Italy:

After landing in France, Shelley continues to happily anticipate her travels and the benefits she will derive from them. Travelling throughout Germany, she complains about the slowness of travel but is pleased to discover that her memories of the Rhine correspond to the reality. Shelley becomes ill in Germany and pauses at Baden-Baden to recover her health. Fearing Percy Florence's (referred to as P– in the text) love of boats and the water, especially difficult for her after her own husband drowned in a boating accident, she is reluctant to continue to Italy and Lake Como while at the same time desiring to do so. After Shelley recovers her health and spirits, the group proceeds to Italy where she is overcome with nostalgia:

Shelley writes of her overwhelming happiness in Italy and her sadness at having to leave it. At the end of September, her money to return to England fails to arrive, so Percy Florence and his friends return without her. Her funds eventually arrive, and she journeys to England alone: In the letters covering her return journey, she describes the sublime

scenery through which she travels, particularly the Simplon Pass

and waterfalls in Switzerland.

Part II, which consists of eleven conversational letters, covers the first part of Shelley's trip to Europe in 1842, specifically her journey from Antwerp to Prague

Part II, which consists of eleven conversational letters, covers the first part of Shelley's trip to Europe in 1842, specifically her journey from Antwerp to Prague

; the names of her travelling companions are disguised in the text and she rarely alludes to them. She discusses art, sometimes spending several pages describing individual works of art; the benefits and drawbacks of travel by railway versus carriage; the German character and habits of the German people; the history associated with the sights she sees; the scenery and the weather; and her problems as a traveller, for example, her inability to speak German, the dirtiness of the inns, and exorbitant pricing for tourists. Shelley begins this section by musing on the benefits of travel:

Briefly passing through a quick succession of German cities by railway, carriage, and boat, the group arrives at Kissingen, where they decide to remain for a month for Shelley to "take the cure" at the bath. While Shelley believes the waters will be efficacious, she chafes at the restrictions put on those attempting to better their health, such as rising at five or six and eating no delicacies. Her companions are increasingly frustrated by the schedule and the lack of entertainment at the spa. After leaving Kissingen, the group travels through the area around Weimar, seeing sights associated with Martin Luther

and the writers Wieland

, Schiller, and Goethe. They continue to Berlin and Dresden, where they spend time viewing art and attending the opera, leaving for Prague in August 1842.

), the art of Baroque

and Renaissance Italy

, the literature of Italy

, and offers opinions on Italy's recent governments, the national character of the German and Italian people, and Catholicism. She also ponders the changes in herself from who she was in the 1820s to who she is in the 1840s, particularly in relation to her grief:

Rambles is a travel narrative

Rambles is a travel narrative

, part of a literary tradition begun in the seventeenth century. Through the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, Continental travel was considered educational: young, aristocratic gentlemen completed their studies by learning European languages abroad and visiting foreign courts. In the early seventeenth century, however, the emphasis shifted from classical learning

to a focus on gaining experience in the real world, such as knowledge of topography, history, and culture. Detailed travel books, including personal travel narratives, began to be published and became popular in the eighteenth century: over 1,000 individual travel narratives and travel miscellanies were published between 1660 and 1800. The empiricism that was driving the scientific revolution

spread to travel literature; for example, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

included information she learned in Turkey

regarding smallpox

inoculation in her travel letters. By 1742, critic and essayist Samuel Johnson

was recommending that travellers engage in "a moral and ethical study of men and manners" in addition to a scientific study of topography and geography.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, the Grand Tour

became increasingly popular. Travel to the Continent for Britain’s elite was not only educational but also nationalistic. All aristocratic gentlemen took similar trips and visited similar sites, with the intention of developing an appreciation of Britain from abroad. The Grand Tour was celebrated as educational travel when it involved exchanging scientific information with the intellectual elite, learning about other cultures, and preparing for leadership. However, it was condemned as trivial when the tourist simply purchased curio

collectibles, acquired a "superficial social polish", and pursued fleeting sexual relationships. During the Napoleonic Wars

, the Continent was closed to British travellers

and the Grand Tour came under increasing criticism, particularly from radicals

such as Mary Shelley's father, William Godwin

, who scorned its aristocratic associations. Young Romantic writers criticised its lack of spontaneity; they celebrated Madame de Staёl's

novel Corinne (1807), which depicts proper travel as "immediate, sensitive, and above all [an] enthusiastic experience".

Travel literature changed in the 1840s as steam-powered ships and trains made Continental journeys accessible to the middle class. Guidebooks and handbooks were published for this new traveller, who was unfamiliar with the tradition of the Grand Tour. The most famous of these was John Murray's Handbook for Travellers on the Continent (1836). By 1848, Murray had published 60 such works, which "emphasised comprehensiveness, presenting numerous possible itineraries and including information on geology, history, and art galleries". Whereas during the Romantic period, travel writers differentiated themselves from mere tourists through the spontaneity and exuberance of their reactions, during the Victorian period

, travel writers attempted to legitimise their works through a "discourse of authenticity". That is, they claimed to have experienced the true culture of an area and their reactions to it were specifically personal, as opposed to the writers of generic guidebooks, whose response was specifically impersonal.

, whose travel narrative of Italy, accompanied by illustrations by J.M.W. Turner, had been a bestseller in the late 1820s. Rogers’s text had avoided politics and focused on picturesque

and sublime

scenery. Although Shelley dedicated Rambles to Rogers, her preface acknowledged the influence of Lady Morgan

, whose travel work, Italy (1821), had been vocal in its criticism of Austria’s rule over Italy and had been placed on the papal list of prohibited books

. To make her politics more palatable to her audience, however, Shelley often uses analyses of literature and art to reiforce her points.

Shelley's travel narrative, with its "informal" and "subjective" focus on her personal experiences, reflects the Romantic emphasis on the individual. Unlike Augustus Bozzi Granville's The Spas of Germany (1837), which exudes a Victorian respect for order, political authority, and careful documentation, Shelley focuses on her own reactions to these experiences. She specifically criticises the surveillance and control methods used at the spas she visited, such as the strict dietary regimens and confiscation of letters.

), Britain experienced an "antifeminist reaction" and women were increasingly discouraged from writing on so-called "masculine" topics. As Moskal explains, there was a "massive cultural prejudice that equate[d] masculinity with mobility", making travel writing itself a masculine genre; there was even a "masculinist aesthetic vocabulary". Women in the late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century wrote travel narratives anyway, but at a cost. Wollstonecraft is described as asking "men’s questions" when she is curious about her surroundings and both Lady Morgan’s and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s

travel narratives received hostile reviews because they discussed political issues.

Both Shelley and her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, exceeded the bounds of what would have been considered "the normal purview of the female writer" in their travel narratives. Shelley excitedly describes running the rapids in a canoe, for example, and describes the economic status and technological development of the areas she visits. In Paris, she comments on the lack of drains in the streets, in Berlin she visits a steel mill, and throughout the text she describes how the new railways are impacting on travel. Shelley's travel narrative is marked by a specific "ethic of travel"—that one must learn to sympathise both physically and emotionally with those one encounters. Her travels are sentimental

, and travel writing for her is "an exploration of the self through an encounter with the other". Her language even mirrors that of her mother. Wollstonecraft describes the frontier of Sweden as "the bones of the world waiting to be clothed with everything necessary to give life and beauty" while Shelley describes the Simplon Pass

as having "a majestic simplicity that inspired awe; the naked bones of a gigantic world were here: the elemental substance of fair mother Earth".

Also like her mother, whose Letters from Sweden was foundational to the writing of both History of a Six Weeks’ Tour and Rambles, Shelley emphasised her maternal role in the text. She describes herself as a conventional figure, worrying about her son. Rather than the scandal-ridden young woman of her youth, which she wrote about in the Tour, she is now a demure, respectable, middle-aged woman.

Shelley’s stated aim in Rambles is to raise awareness of the political situation in Italy and to convince readers to aid the revolutionaries in their fight for independence. She addresses her readers as English citizens, arguing that they in particular "ought to sympathise in [the Italians'] struggles; for the aspiration for free institutions all over the world has its source in England". On a general level, she articulates an "opposition to monarchical government, disapproval of class distinction, abhorrence of slavery and war and their concomitant cruelties" similar to that in her historical novels Valperga

Shelley’s stated aim in Rambles is to raise awareness of the political situation in Italy and to convince readers to aid the revolutionaries in their fight for independence. She addresses her readers as English citizens, arguing that they in particular "ought to sympathise in [the Italians'] struggles; for the aspiration for free institutions all over the world has its source in England". On a general level, she articulates an "opposition to monarchical government, disapproval of class distinction, abhorrence of slavery and war and their concomitant cruelties" similar to that in her historical novels Valperga

(1823) and Perkin Warbeck

(1830). The central theme of the second journey is "the tyranny of Austrian and French imperialism, and the abuses of papal and priestly authority". The solution to Italy’s problems, according to Shelley, is neither "subjugation" nor "revolution" but rather "peaceful mediation". Ultimately, it is the lessons learned from history that Shelley feels are the most important, which is why she compares the past and present. Rambles articulates the "Whiggish ideology of political gradualism", and is similar to Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) in that it argues that "a reformation of culture is necessary to reform oppressive and degrading power relations".

Shelley’s political frame for her travel narrative was a difficult one to sell to readers. Her audience wanted to support the revolutionaries, especially exiles living among them, such as Mazzini, but they were also fearful of the violence of the Carbonari and its nationalist ideology. They connected nationalism to their historic enemy—Napoleonic France. In fact, other travel works published at the time made the argument that Napoleon was responsible for Italian unification. Shelley therefore contends that the Risorgimento is primarily inspired by the English and only secondarily by the French (she never names Napoleon). Shelley writes a history of Italian nationalism

acceptable to English readers, in which the French are the tyrants oppressing the rising nation of Italy, which the Carbonari, although violent, have inspired and created. Her readers could therefore comfortably support Italian nationalism without supporting policies reminiscent of Napoleon. She also placed most of her political commentary at the end of the text. As Moskal explains, "Shelley creates a structure in which the reader, having already befriended the traveller for some pages, receives this political matter from a friend, not from a stranger." She also praises Italian literature, particularly the works of Alessandro Manzoni

, Pietro Colletta

, and Michele Amari

, connecting it to Italian nationalism.

In writing about the Italian situation, Shelley is also advocating a general liberal

agenda of rights for the working and middle classes, which had been crushed by the Reign of Terror

and Napoleon. British reformers could look with hope towards Italy.

Shelley frequently laments the poor education on offer to Italians, although she hopes this will spur them to revolt. She does not think much of the Germans. In her earlier travels, she had described the Germans as rude and disgusting; in 1842, she wrote to her half-sister Claire Clairmont

, "I do dislike the Germans—& never wish to visit Germany again—but I would not put this in print—for the surface is all I know." Rambles contains little commentary on the Germans, therefore, except to say that she was impressed by their public education system.

It was how political events affected people that Shelley was most interested in. In her History of a Six Weeks' Tour, she had paused several times to discuss the effects of war and she does so again with her description of the Hessians in Rambles:

and Dolan that she needed to recover from a damaging trauma

. Shelley writes about this process in Rambles, using the trope

of a pilgrimage; she believes that travelling to Italy and revisiting the scenes of her youth will cure her of her depression, writing, "Besides all that Rome itself affords of delightful [sic] to the eye and imagination, I revisit it as the bourne of a pious pilgrimage. The treasures of my youth lie buried here." Shelley's pilgrimage follows in the tradition of Chaucer as well as the nineteenth-century trend to visit spas for healing, and like most pilgrimage narratives, hers does not relate the journey home. For Shelley, ultimately the most helpful part of travelling and visiting spas was seeing the beautiful scenery. In Rambles, Shelley contends that interacting with picturesque scenery can heal the body. Both the 1840 and 1842 trips followed times of ill health for Shelley and she used them as a way to recover both emotionally and physically. She opens Rambles by describing her poor health and hoping that by travelling her "mind will ... renew the outworn and tattered garments in which it has long been clothed".

Shelley's first travel narrative and first published work, History of a Six Weeks' Tour, was published anonymously and was co-written with her husband. Rambles, on the other hand, places Mary Shelley at the center of the narrative. It tells the story of "the recovery of paradise" and the fears of a mother. Her maternal sorrow is generalised, however. For example, in discussing the death of her daughter in 1818, she writes: "I was agitated again by emotions—by passions—and those the deepest a woman's heart can harbour—a dread to see her child even at that instant expire—which then occupied me". Connecting these deep feelings to writings by Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Coleridge

, and Thomas Holcroft

, she argues that intense emotion and environment are intertwined, contending that maternal grief is sublime

.

Of Rambles, Mary Shelley wrote to her friend Leigh Hunt

Of Rambles, Mary Shelley wrote to her friend Leigh Hunt

: "It seems to me such a wretched piece of work, written much of it in a state of pain that makes me look at its pages now as if written in a dream." She disliked the work, describing it variously as "a poor affair" and "my poor book", and claimed that Gatteschi had written the best parts. There are no statistics on the sales of the book, but it received at least seventeen reviews. In general, the reviews were favourable; as Moskal explains, "with nationalist movements simmering in Europe, to culminate in the revolutions of 1848, reviewers took Rambles seriously as a political as well as a literary endeavour."

Reviewers praised the work as "entertaining, thoughtful and eminently readable", although some thought it was too mournful in places. Separating Shelley’s travel memoir from the new guidebooks and handbooks, reviews such as that from the Atlas, praised her "rich fancy, her intense love of nature, and her sensitive apprehension of all that is good, and beautiful and free". They praised its independence of thought, wit, and feeling. Shelley’s commentary on the social and political life of Italy, which was generally thought superior to the German sections, caused one reviewer to call the book the work of "a woman who thinks for herself on all subjects, and who dares to say what she thinks", a woman with a "masculine and original mind". However, not all reviewers celebrated her independence of mind. The Observer

wrote: "With her, as with all women, politics is a matter of the heart, and not as with the more robust nature of man, of the head ... It is an idle and unprofitable theme for a woman." Most of the reviews responded positively to Shelley’s political aims; however, those that were unsympathetic to her political position generally disputed her specific claims. For example, one reviewer claimed that Italy had been improved by Austrian rule.

For most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Mary Shelley was known as the author of Frankenstein

and the wife of famous Romantic poet

Percy Bysshe Shelley. Therefore, as of 1961, Rambles had never been reprinted and, as scholar Elizabeth Nitchie explained, "scant use has been made of it, and copies of it are rather scarce." However, she argued that some of Mary Shelley’s "best writing" was in Rambles. Novelist Muriel Spark

agreed in her book on Shelley, writing that Rambles "contains more humour and liveliness than occur in anything else she wrote". It was not until the 1970s, with the rise of feminist literary criticism

, that scholars began to pay attention to Shelley's other works. With the publication of scholarship by Mary Poovey

and Anne K. Mellor

in the 1980s, Mary Shelley's "other" works—her short stories, essays, reviews, dramas, biographies, travel narratives, and other novels—began to be recognised as literary achievements. In the 1990s, Mary Shelley's entire corpus, including Rambles, was finally reprinted.

Travel literature

Travel literature is travel writing of literary value. Travel literature typically records the experiences of an author touring a place for the pleasure of travel. An individual work is sometimes called a travelogue or itinerary. Travel literature may be cross-cultural or transnational in focus, or...

by the British Romantic

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

author Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley was a British novelist, short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, and travel writer, best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus . She also edited and promoted the works of her husband, the Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley...

. Issued in 1844, it is her last published work. Published in two volumes, the text describes two European trips that Mary Shelley took with her son, Percy Florence Shelley

Percy Florence Shelley

Sir Percy Florence Shelley, 3rd Baronet was the son and only surviving child of Percy Bysshe Shelley and his second wife, Mary Shelley. He was thus the only grandchild of Mary Wollstonecraft...

, and several of his university friends. Mary Shelley had lived in Italy with her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the major English Romantic poets and is critically regarded as among the finest lyric poets in the English language. Shelley was famous for his association with John Keats and Lord Byron...

, between 1818 and 1823. For her, Italy was associated with both joy and grief: she had written much while there but she had also lost her husband and two of her children. Thus, although she was anxious to return, the trip was tinged with sorrow. Shelley describes her journey as a pilgrimage

Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey or search of great moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith...

, which will help cure her depression.

At the end of the second trip, Mary Shelley spent time in Paris and associated herself with the "Young Italy

Young Italy (historical)

Young Italy was a political movement founded in 1831 by Giuseppe Mazzini. The goal of this movement was to create a united Italian republic through promoting a general insurrection in the Italian reactionary states and in the lands occupied by the Austrian Empire...

" movement, Italian exiles who were in favour of Italian independence and unification. One revolutionary in particular attracted her: Ferdinando Gatteschi. To assist him financially, Shelley decided to publish Rambles. However, Gatteschi became discontented with Shelley's assistance and tried to blackmail her. She was forced to obtain her personal letters from Gatteschi through the intervention of the French police.

Shelley differentiates her travel book from others by presenting her material from what she describes as "a political point of view". In so doing, she challenges the early nineteenth-century convention that it was improper for women to write about politics, following in the tradition of her mother, Mary Wollstonecroft, and Lady Morgan

Lady Morgan

Sydney, Lady Morgan , was an Irish novelist, best known as the author of The Wild Irish Girl.-Early life:...

. Shelley's aim was to arouse sympathy in England for Italian revolutionaries, such as Gatteschi. She rails against the imperial rule of Austria

Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia

The Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia was created at the Congress of Vienna, which recognised the House of Habsburg's rights to Lombardy and Venetia after the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed by Napoleon in 1805, had collapsed...

and France over Italy and criticises the domination of the Catholic Church. She describes the Italians as having an untapped potential for greatness and a desire for freedom.

Although Shelley herself thought the work "poor", it found favour with reviewers who praised its independence of thought, wit, and feeling. Shelley's political commentary on Italy was specifically singled out for praise, particularly since it was written by a woman. However, for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Shelley was usually known only as the author of Frankenstein

Frankenstein

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a novel about a failed experiment that produced a monster, written by Mary Shelley, with inserts of poems by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley started writing the story when she was eighteen, and the novel was published when she was twenty-one. The first...

and the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Rambles was not reprinted until the rise of feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or by the politics of feminism more broadly. Its history has been broad and varied, from classic works of nineteenth-century women authors such as George Eliot and Margaret Fuller to cutting-edge theoretical work in...

in the 1970s provoked a wider interest in Shelley's entire corpus.

Risorgimento

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

until the end of the nineteenth century, Italy was divided into many small duchies and city-state

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

s, some of which were autonomous and some of which were controlled by Austria, France, Spain, or the Papacy. These multifarious governments and the diversity of Italian dialects spoken on the peninsula caused residents to identify as "Romans" or "Venetians", for example, rather than as "Italians". (It was not until the late nineteenth century that Tuscan Italian

Italian language

Italian is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe: Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and by immigrant communities in the Americas and Australia...

became the national language.) When Napoleon conquered parts of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars were a series of major conflicts, from 1792 until 1802, fought between the French Revolutionary government and several European states...

(1792–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

(1803–15), he unified many of the smaller principalities; he centralised the governments and built roads and communication networks that helped to break down the barriers between and among Italians. Not all Italians welcomed French rule, however; Giuseppe Capo Biaco founded a secret society called the Carbonari

Carbonari

The Carbonari were groups of secret revolutionary societies founded in early 19th-century Italy. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in Spain, France, Portugal and possibly Russia. Although their goals often had a patriotic and liberal focus, they lacked a...

to resist both French rule and the Roman Catholic Church. After Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

in 1815 and the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

returned state authority to the Austrians, the Carbonari continued their resistance. The Carbonari led revolts in Naples

Naples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

and Piedmont

Piedmont

Piedmont is one of the 20 regions of Italy. It has an area of 25,402 square kilometres and a population of about 4.4 million. The capital of Piedmont is Turin. The main local language is Piedmontese. Occitan is also spoken by a minority in the Occitan Valleys situated in the Provinces of...

in 1820 and 1821 and in Bologna

Bologna

Bologna is the capital city of Emilia-Romagna, in the Po Valley of Northern Italy. The city lies between the Po River and the Apennine Mountains, more specifically, between the Reno River and the Savena River. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with spectacular history,...

, the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

, Parma

Parma

Parma is a city in the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna famous for its ham, its cheese, its architecture and the fine countryside around it. This is the home of the University of Parma, one of the oldest universities in the world....

, and Modena

Modena

Modena is a city and comune on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy....

in the 1830s. After the failure of these revolts, Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini , nicknamed Soul of Italy, was an Italian politician, journalist and activist for the unification of Italy. His efforts helped bring about the independent and unified Italy in place of the several separate states, many dominated by foreign powers, that existed until the 19th century...

, a Carbonaro who was exiled from Italy, founded the "Young Italy" group to work toward the unification of Italy, to establish a democratic republic, and to force non-Italian states to relinquish authority on the peninsula. By 1833, 60,000 people had joined the movement. These nationalist revolutionaries, with foreign support, attempted, but failed, to overthrow the Austrians in Genoa

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

and Turin

Turin

Turin is a city and major business and cultural centre in northern Italy, capital of the Piedmont region, located mainly on the left bank of the Po River and surrounded by the Alpine arch. The population of the city proper is 909,193 while the population of the urban area is estimated by Eurostat...

in 1833 and Calabria

Calabria

Calabria , in antiquity known as Bruttium, is a region in southern Italy, south of Naples, located at the "toe" of the Italian Peninsula. The capital city of Calabria is Catanzaro....

in 1844. Italian unification

Italian unification

Italian unification was the political and social movement that agglomerated different states of the Italian peninsula into the single state of Italy in the 19th century...

, or Risorgimento, was finally achieved in 1870 under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi was an Italian military and political figure. In his twenties, he joined the Carbonari Italian patriot revolutionaries, and fled Italy after a failed insurrection. Garibaldi took part in the War of the Farrapos and the Uruguayan Civil War leading the Italian Legion, and...

.

1840

Mary Shelley and her husband Percy Bysshe ShelleyPercy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the major English Romantic poets and is critically regarded as among the finest lyric poets in the English language. Shelley was famous for his association with John Keats and Lord Byron...

had lived in Italy from 1818 to 1823. Although Percy Shelley and two of their four children died there, Italy became for Mary Shelley "a country which memory painted as paradise", as she put it. The couple's Italian years were a time of intense intellectual and creative activity. While Percy composed a series of major poems, Mary wrote the autobiographical novel Matilda

Matilda (novella)

Mathilda, or Matilda, is the second novel of Mary Shelley, written between August 1819 and February 1820. It deals with common Romantic themes of incest and suicide.-Background:...

, the historical novel

Historical novel

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, a historical novel is-Development:An early example of historical prose fiction is Luó Guànzhōng's 14th century Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which covers one of the most important periods of Chinese history and left a lasting impact on Chinese culture.The...

Valperga

Valperga (novel)

Valperga: or, the Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca is an 1823 historical novel by the Romantic novelist Mary Shelley, set amongst the wars of the Guelphs and Ghibellines,...

, and the plays Proserpine

Proserpine (play)

Proserpine is a verse drama written for children by the English Romantic writers Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary wrote the blank verse drama and Percy contributed two lyric poems. Composed in 1820 while the Shelleys were living in Italy, it is often considered a partner to the...

and Midas

Midas (Shelley)

Midas is a verse drama in blank verse by the Romantic writers Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary wrote the drama and Percy contributed two lyric poems to it. Written in 1820 while the Shelleys were living in Italy, Mary Shelley tried unsuccessfully to have the play published by children's...

. Mary Shelley had always wanted to return to Italy and she excitedly planned her 1840 trip. However, the return was painful as she was constantly reminded of Percy Shelley.

In June 1840, Mary Shelley, Percy Florence

Percy Florence Shelley

Sir Percy Florence Shelley, 3rd Baronet was the son and only surviving child of Percy Bysshe Shelley and his second wife, Mary Shelley. He was thus the only grandchild of Mary Wollstonecraft...

(her one surviving child), and a few of his friends—George Defell, Julian Robinson, and Robert Leslie Ellis

Robert Leslie Ellis

Robert Leslie Ellis was an English polymath, remembered principally as a mathematician and editor of the works of Francis Bacon....

—began their European tour. They traveled to Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

and then to Metz

Metz

Metz is a city in the northeast of France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers.Metz is the capital of the Lorraine region and prefecture of the Moselle department. Located near the tripoint along the junction of France, Germany, and Luxembourg, Metz forms a central place...

. From there, they went down the Moselle River

Moselle River

The Moselle is a river flowing through France, Luxembourg, and Germany. It is a left tributary of the Rhine, joining the Rhine at Koblenz. A small part of Belgium is also drained by the Mosel through the Our....

by boat to Coblenz and then up the Rhine River to Mainz

Mainz

Mainz under the Holy Roman Empire, and previously was a Roman fort city which commanded the west bank of the Rhine and formed part of the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire...

, Frankfurt

Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main , commonly known simply as Frankfurt, is the largest city in the German state of Hesse and the fifth-largest city in Germany, with a 2010 population of 688,249. The urban area had an estimated population of 2,300,000 in 2010...

, Heidelberg

Heidelberg

-Early history:Between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago, "Heidelberg Man" died at nearby Mauer. His jaw bone was discovered in 1907; with scientific dating, his remains were determined to be the earliest evidence of human life in Europe. In the 5th century BC, a Celtic fortress of refuge and place of...

, Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden is a spa town in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located on the western foothills of the Black Forest, on the banks of the Oos River, in the region of Karlsruhe...

, Freiburg

Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau is a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. In the extreme south-west of the country, it straddles the Dreisam river, at the foot of the Schlossberg. Historically, the city has acted as the hub of the Breisgau region on the western edge of the Black Forest in the Upper Rhine Plain...

, Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen is a city in northern Switzerland and the capital of the canton of the same name; it has an estimated population of 34,587 ....

, Zürich

Zürich

Zurich is the largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is located in central Switzerland at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich...

, the Splügen

Splügen

Splügen may refer to:* Splügen, a municipality in the Swiss alps* Splügen Pass, an Alpine pass between Switzerland and Italy...

, and Chiavenna. Feeling ill, Shelley rested at a spa in Baden-Baden; she had wracking pains in her head and "convulsive shudders", symptoms of the meningioma

Meningioma

The word meningioma was first used by Harvey Cushing in 1922 to describe a tumor originating from the meninges, the membranous layers surrounding the CNS ....

that would eventually kill her. This stop dismayed Percy Florence and his friends, as it provided no entertainment for them; moreover, since none of them spoke German, the group was forced to remain together. After crossing Switzerland by carriage and railway, the group spent two months at Lake Como

Lake Como

Lake Como is a lake of glacial origin in Lombardy, Italy. It has an area of 146 km², making it the third largest lake in Italy, after Lake Garda and Lake Maggiore...

, where Mary relaxed and reminisced about how she and Percy had almost rented a villa with Lord Byron at the lake one summer. The group then travelled on to Milan

Milan

Milan is the second-largest city in Italy and the capital city of the region of Lombardy and of the province of Milan. The city proper has a population of about 1.3 million, while its urban area, roughly coinciding with its administrative province and the bordering Province of Monza and Brianza ,...

, and from there, Percy Florence and his friends soon left for Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

to take their university finals. Mary Shelley remained, waiting for funds to complete her journey. In September, she returned to England via Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

and Paris. Upon her return, she became depressed and could not write: "[in Italy] I might live – as once I lived—hoping—loving—aspiring enjoying...I am placid now, & the days go by – I am happy in Percy [Florence's] society & health – but no adjuncts...gild the quiet hours & dulness [sic] creeps over my intellect". Despite this lethargy, however, she did manage to publish a second edition of Percy Shelley’s prose and began working on another edition of his poetry.

1842–44

Sir Timothy Shelley gave his grandson Percy Florence an increase in his allowance for his twenty-first birthday, allowing Mary Shelley and Percy Florence to plan a second, longer trip to the Continent. In June 1842, Mary Shelley and her son left for a fourteen-month tour. They were accompanied by a few of his friends: Alexander Andrew Knox, a poet and classicist, who Emily Sunstein, a biographer of Mary Shelley, describes as "reminiscent of [Percy] Shelley"; Henry Hugh Pearson, a musician who had written musical accompaniments for several of Percy Shelley’s poems; and Robert Leslie Ellis. Mary Shelley hoped that the easy manners of the other young men would rub off on her awkward son, but instead they became petty and jealous of each other. The group visited LiègeLiège

Liège is a major city and municipality of Belgium located in the province of Liège, of which it is the economic capital, in Wallonia, the French-speaking region of Belgium....

, Cologne

Cologne

Cologne is Germany's fourth-largest city , and is the largest city both in the Germany Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia and within the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Area, one of the major European metropolitan areas with more than ten million inhabitants.Cologne is located on both sides of the...

, Coblenz, Mainz, Frankfurt, Kissingen, Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, Dresden

Dresden

Dresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

, Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

, Salzburg

Salzburg

-Population development:In 1935, the population significantly increased when Salzburg absorbed adjacent municipalities. After World War II, numerous refugees found a new home in the city. New residential space was created for American soldiers of the postwar Occupation, and could be used for...

, the Tyrol

County of Tyrol

The County of Tyrol, Princely County from 1504, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, from 1814 a province of the Austrian Empire and from 1867 a Cisleithanian crown land of Austria-Hungary...

, Innsbruck

Innsbruck

- Main sights :- Buildings :*Golden Roof*Kaiserliche Hofburg *Hofkirche with the cenotaph of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor*Altes Landhaus...

, Riva

Riva del Garda

Riva del Garda is a town and comune in the northern Italian province of Trentino. It is also known simply as Riva. The estimated population is 15,151.- History :...

, Verona

Verona

Verona ; German Bern, Dietrichsbern or Welschbern) is a city in the Veneto, northern Italy, with approx. 265,000 inhabitants and one of the seven chef-lieus of the region. It is the second largest city municipality in the region and the third of North-Eastern Italy. The metropolitan area of Verona...

, Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, Florence

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

, and Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

. In Rome, Mary Shelley toured museums with the French art critic Alex Rio; Percy Florence was unimpressed with the culture and refused to see the art, infuriating his mother, who spent an increasing amount of her time seeing the country with Knox instead. She also paid numerous visits to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s grave in Rome

Protestant Cemetery, Rome

The Protestant Cemetery , now officially called the Cimitero acattolico and often referred to as the Cimitero degli Inglesi is a cemetery in Rome, located near Porta San Paolo alongside the Pyramid of Cestius, a small-scale Egyptian-style pyramid built in 30 BC as a tomb and later incorporated...

. After two months in the Sorrento Peninsula, the group was short of money; Percy Florence and his friends returned home while Mary Shelley went on to Paris.

In Paris, Mary Shelley associated with many of the Italian expatriates who were part of the "Young Italy" movement. Her recent travels had made her particularly sympathetic to their revolutionary message. One Italian patriot captivated her in particular: Ferdinando Gatteschi, a smart, handsome, would-be writer. He was young—not yet 30—and in exile, following his participation in a failed Carbonari rebellion against Austria in 1830–31. Shelley was fascinated by Gatteschi; she described him as "a hero & an angel & martyr". Jeanne Moskal, the most recent editor of Rambles, argues that Mary Shelley was attracted to Gatteschi because he resembled Percy Shelley: he was an aristocratic writer who had been cast off by his parents for his liberalism. Moskal argues that "the strength of [Shelley’s] devotion overturned her previous resolve not to publish again".

At the end of September 1843, Mary Shelley proposed to her publisher, Edward Moxon

Edward Moxon

Edward Moxon was a British poet and publisher, significant in Victorian literature.Moxon was born at Wakefield in Yorkshire, where his father Michael worked in the wool trade. In 1817 he left for London, joining Longman in 1821...

, that she write a travel book based on her 1840 and 1842 Continental journeys. Interested in assisting Gatteschi, she wrote to Moxon that she was writing "for a purpose most urgent & desirable". She described the work as "light", "personal", and "amusing". Moxon agreed to her proposal and advanced her £60, which she promised to return if fewer than 300 copies of the work were sold. (She subsequently gave this same amount to Gatteschi.) By the end of January 1844, Shelley had already completed most of the first volume. As Sunstein writes, "once started on Rambles, she worked fast and with pleasure, but her head and nerves were bad at times, and her eyes got so weak and inflamed that she wrote only until noon." She left Paris at the end of January and returned to London, still infatuated with Gatteschi. The death of Sir Timothy Shelley, Percy Florence's grandfather, in April 1844, delayed the completion of the work. However, with material from Gatteschi on the Ancona

Ancona

Ancona is a city and a seaport in the Marche region, in central Italy, with a population of 101,909 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region....

uprising of 1831 and research help from German-speaking friends, Shelley finished. The text was largely drawn from correspondence written during her travels to her step-sister Claire Clairmont

Claire Clairmont

Clara Mary Jane Clairmont , or Claire Clairmont as she was commonly known, was a stepsister of writer Mary Shelley and the mother of Lord Byron's daughter Allegra.-Early life:...

. Mary Shelley’s last published work, which was dedicated to the travel writer and poet Samuel Rogers

Samuel Rogers

Samuel Rogers was an English poet, during his lifetime one of the most celebrated, although his fame has long since been eclipsed by his Romantic colleagues and friends Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron...

, came out on 1 August 1844.

| "My letters must be got somehow – either by seizure or purchase – & then he must be left – As to helping him – there are others starving – but enough of that he must be crushed in the first place." |

| — Mary Shelley on Gatteschi's blackmail |

Despite Mary Shelley’s attempts to assist Gatteschi financially, he tried to blackmail her one year later in 1845 using indiscreet letters she had written. After not hearing from Gatteschi for months, she received threatening letters, which claimed that she had promised him financial success and even possibly marriage. He claimed that her letters would demonstrate this. The contents of Mary Shelley’s letters are unknown as they were later destroyed, but she must have felt some danger, for she took great pains to recover the letters and wrote agonised letters to her friends: "[The letters] were written with an open heart – & contain details with regard to my past history, which it [would] destroy me for ever if they ever saw light." Shelley turned to Alexander Knox for help. After obtaining help from the British government, he travelled to Paris and had the Paris police seize Gatteschi’s correspondence. Implying that Gatteschi was a danger to the state, Knox and the Paris police called upon the cabinet noir

Cabinet noir

Cabinet noir was the name given in France to the office where the letters of suspected persons were opened and read by public officials before being forwarded to their destination...

system in order to retrieve the letters. On 11 October, Le National

Le National (newspaper)

Le National was a French daily founded in 1830 by Adolphe Thiers, Armand Carrel, François-Auguste Mignet and the librarian-editor Auguste Sautelet, as the mouthpiece of the liberal opposition to the Second Restoration....

and Le Constitutionnel

Le Constitutionnel

Le Constitutionnel was a French political and literary newspaper, founded in Paris during the Hundred Days by Joseph Fouché. Originally established in October 1815 as The Independent, it took its current name during the Second Restoration. A voice for Liberals, Bonapartists, and critics of the...

reported in outrage that Gatteschi’s personal papers were seized because he was a suspected revolutionary. Mary wrote to Claire that "It is an awful power this seizure", but she did not regret using it. After Knox retrieved her letters, he burned them. Shelley spent £250 of her own money to finance the operation. She was embarrassed by the entire incident.

Description of text

The two volumes of Rambles are divided into three parts. Part I, which occupies part of the first volume, describes the four-month trip Mary Shelley took with Percy Florence and his university friends in 1840. Parts II and III, which comprise the remainder of the first volume and the entirety of the second volume, describe the fourteen-month trip Mary Shelley took with Percy Florence, Alexander Knox, and other university friends in 1842 and 1843. Part II covers June – August 1842 and Part III covers August 1842 – September 1843. All three parts are epistolary and cover a wide range of topics: "these include personal narratives of the difficulty of a journey, on her varying health, her budgetary constraint; comments on whether [John] Murray's guide-book advice as to hotels, routes or sights was reliable; her subjective responses to the pictures, statues, cities and landscapes she has seen; reports on her occupations and those of her companions; historical disquisitions on such topics as the Tyrolean struggle against Napoleon, or the origins of the Carbonari; and authoritative analysis of the present and future state of Italian literature."Part I

In twelve conversational letters written in the first personFirst-person narrative

First-person point of view is a narrative mode where a story is narrated by one character at a time, speaking for and about themselves. First-person narrative may be singular, plural or multiple as well as being an authoritative, reliable or deceptive "voice" and represents point of view in the...

, Mary Shelley charts her travels through Europe during 1840 and her reflections on accommodations, scenery, peasants, economic relationships between the classes, art, literature, and memories of her 1814 and 1816 journeys (recorded in History of a Six Weeks' Tour

History of a Six Weeks' Tour

History of a Six Weeks' Tour through a part of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland; with Letters Descriptive of a Sail Round the Lake of Geneva and of the Glaciers of Chamouni is a travel narrative by the British Romantic authors Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley...

(1817)). In the first letter, she muses on her return to Italy:

After landing in France, Shelley continues to happily anticipate her travels and the benefits she will derive from them. Travelling throughout Germany, she complains about the slowness of travel but is pleased to discover that her memories of the Rhine correspond to the reality. Shelley becomes ill in Germany and pauses at Baden-Baden to recover her health. Fearing Percy Florence's (referred to as P– in the text) love of boats and the water, especially difficult for her after her own husband drowned in a boating accident, she is reluctant to continue to Italy and Lake Como while at the same time desiring to do so. After Shelley recovers her health and spirits, the group proceeds to Italy where she is overcome with nostalgia:

Shelley writes of her overwhelming happiness in Italy and her sadness at having to leave it. At the end of September, her money to return to England fails to arrive, so Percy Florence and his friends return without her. Her funds eventually arrive, and she journeys to England alone: In the letters covering her return journey, she describes the sublime

Sublime (philosophy)

In aesthetics, the sublime is the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual or artistic...

scenery through which she travels, particularly the Simplon Pass

Simplon Pass

Simplon Pass is a high mountain pass between the Pennine Alps and the Lepontine Alps in Switzerland. It connects Brig in the canton of Valais with Domodossola in Piedmont . The pass itself and the villages on each side of it, such as Gondo, are in Switzerland...

and waterfalls in Switzerland.

Part II

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

; the names of her travelling companions are disguised in the text and she rarely alludes to them. She discusses art, sometimes spending several pages describing individual works of art; the benefits and drawbacks of travel by railway versus carriage; the German character and habits of the German people; the history associated with the sights she sees; the scenery and the weather; and her problems as a traveller, for example, her inability to speak German, the dirtiness of the inns, and exorbitant pricing for tourists. Shelley begins this section by musing on the benefits of travel:

Briefly passing through a quick succession of German cities by railway, carriage, and boat, the group arrives at Kissingen, where they decide to remain for a month for Shelley to "take the cure" at the bath. While Shelley believes the waters will be efficacious, she chafes at the restrictions put on those attempting to better their health, such as rising at five or six and eating no delicacies. Her companions are increasingly frustrated by the schedule and the lack of entertainment at the spa. After leaving Kissingen, the group travels through the area around Weimar, seeing sights associated with Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

and the writers Wieland

Christoph Martin Wieland

Christoph Martin Wieland was a German poet and writer.- Biography :He was born at Oberholzheim , which then belonged to the Free Imperial City of Biberach an der Riss in the south-east of the modern-day state of Baden-Württemberg...

, Schiller, and Goethe. They continue to Berlin and Dresden, where they spend time viewing art and attending the opera, leaving for Prague in August 1842.

Part III

Throughout 23 informal letters, Shelley describes her travels from Prague to southern Italy. She ponders the scenery of the areas she passes through, the history of Germany and Italy (e.g. the Tyrolenese rebellion of April 1809 and the activities of the CarbonariCarbonari

The Carbonari were groups of secret revolutionary societies founded in early 19th-century Italy. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in Spain, France, Portugal and possibly Russia. Although their goals often had a patriotic and liberal focus, they lacked a...

), the art of Baroque

Italian Baroque

Italian Baroque is a term referring to a stylistic period in Italian history and art which spanned from the late 16th century to the early 18th century.-History:...

and Renaissance Italy

Italian Renaissance painting

Italian Renaissance painting is the painting of the period beginning in the late 13th century and flourishing from the early 15th to late 16th centuries, occurring within the area of present-day Italy, which was at that time divided into many political areas...

, the literature of Italy

Italian literature

Italian literature is literature written in the Italian language, particularly within Italy. It may also refer to literature written by Italians or in Italy in other languages spoken in Italy, often languages that are closely related to modern Italian....

, and offers opinions on Italy's recent governments, the national character of the German and Italian people, and Catholicism. She also ponders the changes in herself from who she was in the 1820s to who she is in the 1840s, particularly in relation to her grief:

History of the travel narrative

Travel literature

Travel literature is travel writing of literary value. Travel literature typically records the experiences of an author touring a place for the pleasure of travel. An individual work is sometimes called a travelogue or itinerary. Travel literature may be cross-cultural or transnational in focus, or...

, part of a literary tradition begun in the seventeenth century. Through the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, Continental travel was considered educational: young, aristocratic gentlemen completed their studies by learning European languages abroad and visiting foreign courts. In the early seventeenth century, however, the emphasis shifted from classical learning

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

to a focus on gaining experience in the real world, such as knowledge of topography, history, and culture. Detailed travel books, including personal travel narratives, began to be published and became popular in the eighteenth century: over 1,000 individual travel narratives and travel miscellanies were published between 1660 and 1800. The empiricism that was driving the scientific revolution

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

spread to travel literature; for example, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

The Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was an English aristocrat and writer. Montagu is today chiefly remembered for her letters, particularly her letters from Turkey, as wife to the British ambassador, which have been described by Billie Melman as “the very first example of a secular work by a woman about...

included information she learned in Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

regarding smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

inoculation in her travel letters. By 1742, critic and essayist Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

was recommending that travellers engage in "a moral and ethical study of men and manners" in addition to a scientific study of topography and geography.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, the Grand Tour

Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the traditional trip of Europe undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men of means. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transit in the 1840s, and was associated with a standard itinerary. It served as an educational rite of passage...

became increasingly popular. Travel to the Continent for Britain’s elite was not only educational but also nationalistic. All aristocratic gentlemen took similar trips and visited similar sites, with the intention of developing an appreciation of Britain from abroad. The Grand Tour was celebrated as educational travel when it involved exchanging scientific information with the intellectual elite, learning about other cultures, and preparing for leadership. However, it was condemned as trivial when the tourist simply purchased curio

Curio (furniture)

A curio is a predominantly glass cabinet with a metal or wood framework used to display collections of figurines that share some common theme. Most curios have glass on each side or a mirror at the back and glass levels to show the entire figurine. A curio prevents dust and vermin from destroying...

collectibles, acquired a "superficial social polish", and pursued fleeting sexual relationships. During the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, the Continent was closed to British travellers

Continental System

The Continental System or Continental Blockade was the foreign policy of Napoleon I of France in his struggle against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland during the Napoleonic Wars. It was a large-scale embargo against British trade, which began on November 21, 1806...

and the Grand Tour came under increasing criticism, particularly from radicals

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

such as Mary Shelley's father, William Godwin

William Godwin

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism...

, who scorned its aristocratic associations. Young Romantic writers criticised its lack of spontaneity; they celebrated Madame de Staёl's

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein , commonly known as Madame de Staël, was a French-speaking Swiss author living in Paris and abroad. She influenced literary tastes in Europe at the turn of the 19th century.- Childhood :...

novel Corinne (1807), which depicts proper travel as "immediate, sensitive, and above all [an] enthusiastic experience".

Travel literature changed in the 1840s as steam-powered ships and trains made Continental journeys accessible to the middle class. Guidebooks and handbooks were published for this new traveller, who was unfamiliar with the tradition of the Grand Tour. The most famous of these was John Murray's Handbook for Travellers on the Continent (1836). By 1848, Murray had published 60 such works, which "emphasised comprehensiveness, presenting numerous possible itineraries and including information on geology, history, and art galleries". Whereas during the Romantic period, travel writers differentiated themselves from mere tourists through the spontaneity and exuberance of their reactions, during the Victorian period

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

, travel writers attempted to legitimise their works through a "discourse of authenticity". That is, they claimed to have experienced the true culture of an area and their reactions to it were specifically personal, as opposed to the writers of generic guidebooks, whose response was specifically impersonal.

Rambles as a travel narrative