Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

Encyclopedia

Richard Plantagenêt, 3rd Duke of York, 6th Earl of March, 4th Earl of Cambridge, and 7th Earl of Ulster, conventionally called Richard of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460) was a leading English magnate, great-grandson of King Edward III

. He inherited great estates, and served in various offices of state in France

at the end of the Hundred Years' War

, and in England, ultimately governing the country as Lord Protector

during Henry VI

's madness. His conflicts with Henry's queen, Margaret of Anjou

, and other members of Henry's court were a leading factor in the political upheaval of mid-fifteenth-century England, and a major cause of the Wars of the Roses

. Richard eventually attempted to claim the throne but was dissuaded, although it was agreed that he would become King on Henry's death. Within a few weeks of securing this agreement, he died in battle.

Although Richard never became king, he was the father of Edward IV

and Richard III

.

and Anne Mortimer. Anne was the senior heiress of Lionel of Antwerp

, the second surviving son of Edward III; this arguably gave her and her family a superior claim to the throne over that of the House of Lancaster

. Anne died giving birth to Richard. He was a younger brother of Isabel, Countess of Essex.

His paternal grandparents were Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York

(the fourth son of Edward III to survive infancy) and Isabella of Castile

. His maternal grandparents were Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and Alianore Holland

.

His father was executed for his part in the Southampton Plot

against Henry V

on 5 August 1415, and attainted

. Richard therefore inherited neither lands nor title from his father. However his paternal uncle Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York

, who was killed at the Battle of Agincourt

on 25 October 1415, was childless and Richard was his closest male relative.

After some hesitation Henry V allowed Richard to inherit the title and (at his majority) the lands of the Duchy of York. The lesser title and (in due course) greater estates of the Earldom of March also became his on the death of his maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, on 19 January 1425. The reason for Henry's hesitation was that Edmund Mortimer had been proclaimed several times to have a stronger claim to the throne than Henry's father, Henry IV of England

, by factions rebelling against him. However, during his lifetime, Mortimer remained a faithful supporter of the House of Lancaster.

Richard of York already had the Mortimer and Cambridge claims to the English throne; once he inherited the March, he also became the wealthiest and most powerful noble in England, second only to the King himself.

and Northamptonshire

, Yorkshire

, and Wiltshire

and Gloucestershire

were considerable. The wardship of such an orphan was therefore a valuable gift of the crown, and in October 1417 this was granted to Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmoreland, with the young Richard under the guardianship of Sir Robert Waterton. Ralph Neville had fathered an enormous family (twenty-three children, twenty of whom survived infancy, through two wives) and had many daughters needing husbands. As was his right, in 1424 he betrothed the 13-year-old Richard to his daughter Cecily Neville

, then aged 9.

In October 1425, when Ralph Neville died, he bequeathed the wardship of York to his widow, Joan Beaufort. By now the wardship was even more valuable, as Richard had inherited the Mortimer estates on the death of the Earl of March. These manors were concentrated in Wales

, and in the Welsh Borders around Ludlow

.

Little is recorded of Richard's early life. On 19 May 1426 he was knighted at Leicester

by John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford

, the younger brother of Henry V. In October 1429 (or earlier) his marriage to Cecily Neville took place. On 6 November he was present at the formal coronation of Henry VI

in Westminster Abbey

. He then followed Henry to France, being present at his coronation as King of France in Notre Dame

on 16 December 1431. Finally, on 12 May 1432 he came into his inheritance and was granted full control of his estates.

either needed to conquer more territory to ensure permanent French subordination, or to concede territory to gain a negotiated settlement. During Henry VI's minority, his Council took advantage of French weakness and the alliance with Burgundy

to increase England's possessions, but following the Treaty of Arras (1435), Burgundy ceased to recognise the King of England's claim to the French throne.

York's appointment was one of a number of stop-gap measures after the death of Bedford to try to retain French possessions until King Henry should assume personal rule. The fall of Paris

(his original destination) led to his army being redirected to Normandy

. Working with Bedford's captains, York had some success, recapturing Fecamp

and holding on to the Pays de Caux

, while establishing good order and justice in the Duchy of Normandy. However, he was dissatisfied with the terms under which he was appointed, as he had to find much of the money to pay his troops and other expenses from his own estates. His term of office was nevertheless extended beyond the original twelve months, and he returned to England in November 1439. In spite of his position as one of the leading nobles of the realm, he was not included in Henry VI's Council on his return.

However, in 1443 Henry put the newly-created John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

in charge of an army of 8,000 men, initially intended for the relief of Gascony

. This denied York much-needed men and resources at a time when he was struggling to hold the borders of Normandy. Not only that, but the terms of Somerset's appointment could have caused York to feel that his own role as effective regent over the whole of Lancastrian France was reduced to that of governor of Normandy. Somerset's army achieved nothing, and eventually returned to Normandy, where Somerset died. This may have been the start of the hatred that York felt for the Beaufort family, that would later turn into civil war.

English policy now turned back to a negotiated peace (or at least a truce) with France, so the remainder of York's time in France was spent in routine administration and domestic matters. Duchess Cecily had accompanied him to Normandy, and his children Edward

, Edmund

and Elizabeth

were born in Rouen

.

, who had succeeded his brother John. During 1446 and 1447 York attended meetings of Henry VI's Council and of Parliament, but most of his time was spent in administration of his estates on the Welsh border.

His attitude toward the Council's surrender of Maine, in return for an extension of the truce with France and a French bride for Henry, must have contributed to his appointment on 30 July as Lieutenant of Ireland

. In some ways it was a logical appointment, as Richard was also Earl of Ulster

and had considerable estates in Ireland

, but it was also a convenient way of removing him from both England and France. His term of office was for ten years, ruling him out of consideration for any other high office during that period.

Domestic matters kept him in England until June 1449, but when he did eventually go, it was with Cecily (who was pregnant at the time) and an army of around 600 men. This suggests a stay of some time was envisaged. However, claiming lack of money to defend English possessions, York decided to return to England. His financial state may indeed have been problematic, since by the mid-1440s he was owed nearly £40,000 by the crown, and the income from his estates was declining.

, Lord Privy Seal

and Bishop of Chichester

, was lynched. In May the chief councillor of the King, William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk

, was murdered on his way into exile. The House of Commons

demanded that the King take back many of the grants of land and money he had made to his favourites.

In June, Kent

and Sussex

rose in revolt. Led by Jack Cade

(taking the name Mortimer), they took control of London

and killed John Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele

, the Lord High Treasurer

of England. In August, the final towns held in Normandy fell to the French, and refugees flooded back to England.

On 7 September, York landed at Beaumaris. Evading an attempt by Henry to intercept him, and gathering followers as he went, York arrived in London on 27 September. After an inconclusive (and possibly violent) meeting with the King, York continued to recruit, both in East Anglia

and the west. The violence in London was such that Somerset, back in England after the collapse of English Normandy, was put in the Tower of London

for his own safety. In December Parliament elected York's chamberlain, Sir William Oldhall, as speaker.

York's public stance was that of a reformer, demanding better government and the prosecution of the traitors who had lost northern France. Judging by his later actions, there may also have been a more hidden motive — the destruction of Somerset, who was soon released from the Tower. Although granted another office (Justice of the Forest south of the Trent), York still lacked any real support outside Parliament and his own retainers.

In April 1451, Somerset was released from the Tower and appointed Captain of Calais. When one of York's councillors, Thomas Young, the MP for Bristol

,proposed that York be recognised as heir to the throne, he was sent to the Tower and Parliament was dissolved. Henry VI was prompted into belated reforms, which went some way to restore public order and improve the royal finances. Frustrated by his lack of political power, York retired to Ludlow.

In 1452, York made another bid for power, but not to become king himself. Protesting his loyalty, he aimed to be recognised as Henry VI's heir apparent

(Henry was childless after seven years of marriage), while also trying to destroy the Earl of Somerset, who Henry may have preferred to succeed him over York, as a Beaufort descendant. Gathering men on the march from Ludlow, York headed for London, to find the city gates barred against him on Henry's orders. At Dartford

in Kent, with his army outnumbered, and the support of only two of the nobility, York was forced to come to an agreement with Henry. He was allowed to present his complaints against Somerset to the king, but was then taken to London and after two weeks of virtual house arrest

, was forced to swear an oath of allegiance at St Paul's Cathedral

.

, Margaret of Anjou, was pregnant, and even if she should miscarry, the marriage of the newly ennobled Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond

to Margaret Beaufort provided for an alternative line of succession. By July, York had lost both his Offices: Lieutenant of Ireland and Justice of the Forest south of the Trent.

Then, in August, Henry VI suffered a catastrophic mental breakdown. Perhaps brought on by the news of the defeat at the Battle of Castillon

in Gascony

, which finally drove English forces from France, he became completely unresponsive, unable to speak and having to be led from room to room. The council tried to carry on as though the King's disability would be brief. However, eventually they had to admit that something had to be done. In October, invitations for a Great Council were issued, and although Somerset tried to have him excluded, York (the premier Duke of the realm) was included. Somerset's fears were to prove well-grounded, for in November he was committed to the Tower. Despite the opposition of Margaret of Anjou, on 27 March, York was appointed Protector of the Realm and Chief Councillor.

York's appointment of his brother-in-law, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury

, as Chancellor was significant. Henry's burst of activity in 1453 had seen him try to stem the violence caused by various disputes between noble families. These disputes gradually polarised around the long-standing Percy-Neville feud

. Unfortunately for Henry, Somerset (and therefore the king) became identified with the Percy cause. This drove the Nevilles into the arms of York, who now for the first time had support among a section of the nobility.

, were threatened when a Great Council was called to meet on 21 May in Leicester (away from Somerset's enemies in London). York and his Neville relations recruited in the north and probably along the Welsh border. By the time Somerset realised what was happening, there was no time to raise a large force to support the king.

Once York took his army south of Leicester, thus barring the route to the Great Council, the dispute between him and the king regarding Somerset would have to be settled by force. On 22 May, the king and Somerset arrived at St Albans

, with a hastily-assembled and poorly-equipped army of around 2,000. York, Warwick and Salisbury were already there, with a larger and better-equipped army. More importantly, at least some of their soldiers would have had experience in the frequent border skirmishes with the Kingdom of Scotland

and the occasionally rebellious people of Wales

.

The First Battle of St Albans

which immediately followed hardly deserves the term battle. Possibly as few as 50 men were killed, but among them were Somerset and the two Percy lords, Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland

and Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford. York and the Nevilles had therefore succeeded in killing their enemies, while York's capture of the king gave him the chance to resume the power he had lost in 1453. It was vital to keep Henry alive, as his death would have led, not to York becoming king himself, but to the minority rule of his two-year-old son Edward of Westminster

. Since York's support among the nobility was small, he would be unable to dominate a minority council led by Margaret of Anjou.

In the custody of York, the king was returned to London with York and Salisbury riding alongside, and with Warwick bearing the royal sword in front. On 25 May, Henry received the crown from York, in a clearly symbolic display of power. York made himself Constable of England, and appointed Warwick Captain of Calais. York's position was enhanced when some of the nobility agreed to join his government, including Lord Fauconberg

, who had served under him in France.

For the rest of the summer York held the king prisoner, either in Hertford

castle or (in order to be enthroned in Parliament in July) in London. When Parliament met again in November the throne was empty, and it was reported that the king was ill again. York resumed the office of Protector; although he surrendered it when the king recovered in February 1456, it seemed that this time Henry was willing to accept that York and his supporters would play a major part in the government of the realm.

Salisbury and Warwick continued to serve as councillors, and Warwick was confirmed as Captain of Calais. In June, York himself was sent north to defend the border against a threatened invasion by James II of Scotland

. However, the king once again came under the control of a dominant figure, this time one harder to replace than Suffolk or Somerset: for the rest of his reign, it would be the queen, Margaret of Anjou, who would control the king.

, in the heart of the Queen's lands. How York was treated now depended on how powerful the Queen's views were. York was regarded with suspicion on three fronts: he threatened the succession of the young Prince of Wales

; he was apparently negotiating for the marriage of his eldest son Edward into the Burgundian ruling family; and as a supporter of the Nevilles, he was contributing to the major cause of disturbance in the kingdom – the Percy/Neville feud.

Here, the Nevilles lost ground. Salisbury gradually ceased to attend meetings of the council. When his brother Robert Neville

, Bishop of Durham died in 1457, the new appointment was Laurence Booth. Booth was a member of the Queen's inner circle. The Percys were shown greater favour both at court and in the struggle for power on the Scottish Border.

Henry's attempts at reconciliation between the factions divided by the killings at St Albans reached their climax with the Loveday

on 24 March 1458. However, the lords concerned had earlier turned London into an armed camp, and the public expressions of amity seemed not to have lasted beyond the ceremony.

. Parliament was summoned to meet at Coventry in November, but without York and the Nevilles. This could only mean that they were to be accused of treason.

On 11 October, York tried to move south, but was forced to head for Ludlow. On 12 October, at the Battle of Ludford Bridge

, York once again faced Henry just as he had at Dartford seven years earlier. Warwick's troops from Calais refused to fight, and the rebels fled – York to Ireland, Warwick, Salisbury and York's son Edward to Calais. York's wife Cecily and their two younger sons (George

and Richard

) were captured in Ludlow Castle

and imprisoned at Coventry

.

backed him, providing offers of both military and financial support. Warwick's (possibly inadvertent) return to Calais also proved fortunate. His control of the English Channel

meant that pro-Yorkist propaganda

, emphasising loyalty to the king while decrying his wicked councillors, could be spread around Southern England

. Such was the Yorkists' naval dominance that Warwick was able to sail to Ireland in March 1460, meet York and return to Calais in May. Warwick's control of Calais was to prove to be influential with the wool-merchants in London.

In December 1459 York, Warwick and Salisbury had suffered attainder. Their lives were forfeit, and their lands reverted to the king; their heirs would not inherit. This was the most extreme punishment a member of the nobility could suffer, and York was now in the same situation as Henry of Bolingbroke

in 1398. Only a successful invasion of England would restore his fortune. Assuming the invasion was successful, York had three options — become Protector again, disinherit the king so that York's son would succeed, or claim the throne for himself.

On 26 June, Warwick and Salisbury landed at Sandwich

. The men of Kent, always ready to revolt, rose to join them. London opened its gates to the Nevilles on 2 July. They marched north into the Midlands, and on 10 July, they defeated the royal army at the Battle of Northampton

(through treachery among the King's troops), and captured Henry, who they brought back to London.

York remained in Ireland. He did not set foot in England until 9 September, and when he did, he acted as a king. Marching under the arms of his maternal great-great-grandfather Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence

, as he approached London he displayed a banner of the Coat of Arms of England

.

A Parliament which was called to meet on 7 October repealed all the legislation of the Coventry parliament the previous year. On 10 October, York arrived in London and took residence in the royal palace. Entering Parliament with his sword borne upright before him, he made for the empty throne and placed his hand upon it, as if to occupy it. He may have expected the assembled peers to acclaim him as King, as they had acclaimed Henry Bolingbroke

in 1399. Instead, there was silence. Tmhomas Bouchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury

, asked whether he wished to see the King. York replied, "I know of no person in this realm the which oweth not to wait on me, rather than I of him." This high-handed reply did not impress the Lords.

The next day, Richard advanced his claim to the crown by hereditary right, in proper form. However, his narrow support among his peers led to failure once again. After weeks of negotiation, the best that could be achieved was the Act of Accord

, by which York and his heirs were recognised as Henry's successor. However, Parliament did grant York extraordinary executive powers to protect the realm, and with the king effectively in custody, York and Warwick were the de facto

rulers of the country.

, York, Salisbury and York's second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland

headed north on 2 December. They arrived at York's stronghold of Sandal Castle

on 21 December to find the situation bad and getting worse. Forces loyal to Henry controlled the city of York, and nearby Pontefract Castle

was also in hostile hands.

On 30 December, York and his forces sortied from Sandal Castle. Their reasons for doing so are not clear; they were variously claimed to be a result of deception by the Lancastrian forces, or treachery, or simple rashness on York's part. The larger Lancastrian force destroyed York's army in the resulting Battle of Wakefield

. York was killed in the battle. Edmund of Rutland was intercepted as he tried to flee and was executed, possibly by John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford

in revenge for the death of his own father at the First Battle of St Albans. Salisbury escaped but was captured and executed the following night.

York was buried at Pontefract

, but his head was put on a pike by the victorious Lancastrian armies and displayed over Micklegate Bar at York, wearing a paper crown. His remains were later moved to Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay

.

None of his affinity (or his enemies) left a memoir of him. All that remains is the record of his actions, and the propaganda issued by both sides. Faced with the lack of evidence, his intentions can only be inferred from his actions. Few men have come so close to the throne as York, who died not knowing that in only a few months his son Edward would become king. Even at the time, opinion was divided as to his true motives. Did he always want the throne, or did Henry VI's poor government and the hostility of Henry's favourites leave him no choice? Was the alliance with Warwick the deciding factor, or did he just respond to events?

, and finally established the House of York

on the throne following a decisive victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton

. After an occasionally tumultuous reign, he died in 1483 and was succeeded by his son as Edward V, and York's youngest son succeeded him as Richard III

.

Richard of York's grandchildren included Edward V

and Elizabeth of York

. Elizabeth married Henry VII

, founder of the Tudor dynasty

, and became the mother of Henry VIII

, Margaret Tudor

and Mary Tudor

. All subsequent English monarchs have been descendants of Elizabeth of York.

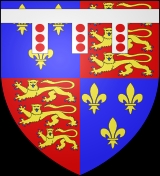

With the dukedom of York, Richard inherited the associated arms of his ancestor, Edmund of Langley

With the dukedom of York, Richard inherited the associated arms of his ancestor, Edmund of Langley

. These arms were those of the kingdom, differentiated by a label argent of three points, each bearing three torteaux gules.

royalty, as well as several major English aristocratic families.

include:

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

. He inherited great estates, and served in various offices of state in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

at the end of the Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

, and in England, ultimately governing the country as Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

during Henry VI

Henry VI of England

Henry VI was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents. Contemporaneous accounts described him as peaceful and pious, not suited for the violent dynastic civil wars, known as the Wars...

's madness. His conflicts with Henry's queen, Margaret of Anjou

Margaret of Anjou

Margaret of Anjou was the wife of King Henry VI of England. As such, she was Queen consort of England from 1445 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471; and Queen consort of France from 1445 to 1453...

, and other members of Henry's court were a leading factor in the political upheaval of mid-fifteenth-century England, and a major cause of the Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses were a series of dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York...

. Richard eventually attempted to claim the throne but was dissuaded, although it was agreed that he would become King on Henry's death. Within a few weeks of securing this agreement, he died in battle.

Although Richard never became king, he was the father of Edward IV

Edward IV of England

Edward IV was King of England from 4 March 1461 until 3 October 1470, and again from 11 April 1471 until his death. He was the first Yorkist King of England...

and Richard III

Richard III of England

Richard III was King of England for two years, from 1483 until his death in 1485 during the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty...

.

Descent

He was the second child of Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of CambridgeRichard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge

Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge was the younger son of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York and Isabella of Castile....

and Anne Mortimer. Anne was the senior heiress of Lionel of Antwerp

Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence

Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, jure uxoris 4th Earl of Ulster and 5th Baron of Connaught, KG was the third son, but the second son to survive infancy, of Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault...

, the second surviving son of Edward III; this arguably gave her and her family a superior claim to the throne over that of the House of Lancaster

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. It was one of the opposing factions involved in the Wars of the Roses, an intermittent civil war which affected England and Wales during the 15th century...

. Anne died giving birth to Richard. He was a younger brother of Isabel, Countess of Essex.

His paternal grandparents were Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York

Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York

Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, 1st Earl of Cambridge, KG was a younger son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault, the fourth of the five sons who lived to adulthood, of this Royal couple. Like so many medieval princes, Edmund gained his identifying nickname from his...

(the fourth son of Edward III to survive infancy) and Isabella of Castile

Isabella of Castile, Duchess of York

Infanta Isabella of Castile, Duchess of York was a daughter ofKing Peter of Castile and María de Padilla. She was a younger sister of Constance, Duchess of Lancaster....

. His maternal grandparents were Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and Alianore Holland

Alianore Holland

Alianore Holland, Countess of March was an English noblewoman, and the wife of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March the heir presumptive of her half-uncle King Richard II of England, and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. She was the mother of Anne Mortimer, and Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March...

.

His father was executed for his part in the Southampton Plot

Southampton Plot

The Southampton Plot of 1415 was a conspiracy against King Henry V of England, aimed at replacing him with Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March. The three alleged ringleaders were Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, Mortimer's brother-in-law; Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham The...

against Henry V

Henry V of England

Henry V was King of England from 1413 until his death at the age of 35 in 1422. He was the second monarch belonging to the House of Lancaster....

on 5 August 1415, and attainted

Attainder

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura is the metaphorical 'stain' or 'corruption of blood' which arises from being condemned for a serious capital crime . It entails losing not only one's property and hereditary titles, but typically also the right to pass them on to one's heirs...

. Richard therefore inherited neither lands nor title from his father. However his paternal uncle Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York

Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York

Sir Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, 2nd Earl of Cambridge, Earl of Rutland, Earl of Cork, Duke of Aumale KG was a member of the English royal family who died at the Battle of Agincourt....

, who was killed at the Battle of Agincourt

Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt was a major English victory against a numerically superior French army in the Hundred Years' War. The battle occurred on Friday, 25 October 1415 , near modern-day Azincourt, in northern France...

on 25 October 1415, was childless and Richard was his closest male relative.

After some hesitation Henry V allowed Richard to inherit the title and (at his majority) the lands of the Duchy of York. The lesser title and (in due course) greater estates of the Earldom of March also became his on the death of his maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, on 19 January 1425. The reason for Henry's hesitation was that Edmund Mortimer had been proclaimed several times to have a stronger claim to the throne than Henry's father, Henry IV of England

Henry IV of England

Henry IV was King of England and Lord of Ireland . He was the ninth King of England of the House of Plantagenet and also asserted his grandfather's claim to the title King of France. He was born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, hence his other name, Henry Bolingbroke...

, by factions rebelling against him. However, during his lifetime, Mortimer remained a faithful supporter of the House of Lancaster.

Richard of York already had the Mortimer and Cambridge claims to the English throne; once he inherited the March, he also became the wealthiest and most powerful noble in England, second only to the King himself.

Childhood and upbringing

As an orphan, the income and management of Richard's lands became the property of the crown. Even though many of the lands of his uncle of York had been granted for life only, or to him and his male heirs, the remaining lands, concentrated in LincolnshireLincolnshire

Lincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

and Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire is a landlocked county in the English East Midlands, with a population of 629,676 as at the 2001 census. It has boundaries with the ceremonial counties of Warwickshire to the west, Leicestershire and Rutland to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshire to the south-east,...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, and Wiltshire

Wiltshire

Wiltshire is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. It contains the unitary authority of Swindon and covers...

and Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn, and the entire Forest of Dean....

were considerable. The wardship of such an orphan was therefore a valuable gift of the crown, and in October 1417 this was granted to Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmoreland, with the young Richard under the guardianship of Sir Robert Waterton. Ralph Neville had fathered an enormous family (twenty-three children, twenty of whom survived infancy, through two wives) and had many daughters needing husbands. As was his right, in 1424 he betrothed the 13-year-old Richard to his daughter Cecily Neville

Cecily Neville

Cecily Neville, Duchess of York was the wife of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, and the mother of two Kings of England: Edward IV and Richard III....

, then aged 9.

In October 1425, when Ralph Neville died, he bequeathed the wardship of York to his widow, Joan Beaufort. By now the wardship was even more valuable, as Richard had inherited the Mortimer estates on the death of the Earl of March. These manors were concentrated in Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, and in the Welsh Borders around Ludlow

Ludlow

Ludlow is a market town in Shropshire, England close to the Welsh border and in the Welsh Marches. It lies within a bend of the River Teme, on its eastern bank, forming an area of and centred on a small hill. Atop this hill is the site of Ludlow Castle and the market place...

.

Little is recorded of Richard's early life. On 19 May 1426 he was knighted at Leicester

Leicester

Leicester is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England, and the county town of Leicestershire. The city lies on the River Soar and at the edge of the National Forest...

by John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford

John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford

John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, KG , also known as John Plantagenet, was the third surviving son of King Henry IV of England by Mary de Bohun, and acted as Regent of France for his nephew, King Henry VI....

, the younger brother of Henry V. In October 1429 (or earlier) his marriage to Cecily Neville took place. On 6 November he was present at the formal coronation of Henry VI

Henry VI of England

Henry VI was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents. Contemporaneous accounts described him as peaceful and pious, not suited for the violent dynastic civil wars, known as the Wars...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

. He then followed Henry to France, being present at his coronation as King of France in Notre Dame

Notre Dame de Paris

Notre Dame de Paris , also known as Notre Dame Cathedral, is a Gothic, Roman Catholic cathedral on the eastern half of the Île de la Cité in the fourth arrondissement of Paris, France. It is the cathedral of the Catholic Archdiocese of Paris: that is, it is the church that contains the cathedra of...

on 16 December 1431. Finally, on 12 May 1432 he came into his inheritance and was granted full control of his estates.

France (1436–1439)

In May 1436, a few months after Bedford's death, York was appointed to succeed him as Lieutenant in France. Henry V's conquests in France could not be sustained forever, as the Kingdom of EnglandKingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

either needed to conquer more territory to ensure permanent French subordination, or to concede territory to gain a negotiated settlement. During Henry VI's minority, his Council took advantage of French weakness and the alliance with Burgundy

Duchy of Burgundy

The Duchy of Burgundy , was heir to an ancient and prestigious reputation and a large division of the lands of the Second Kingdom of Burgundy and in its own right was one of the geographically larger ducal territories in the emergence of Early Modern Europe from Medieval Europe.Even in that...

to increase England's possessions, but following the Treaty of Arras (1435), Burgundy ceased to recognise the King of England's claim to the French throne.

York's appointment was one of a number of stop-gap measures after the death of Bedford to try to retain French possessions until King Henry should assume personal rule. The fall of Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

(his original destination) led to his army being redirected to Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

. Working with Bedford's captains, York had some success, recapturing Fecamp

Fécamp

Fécamp is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Haute-Normandie region in northern France.-Geography:Fécamp is situated in the valley of the river Valmont, at the heart of the Pays de Caux, on the Albaster Coast...

and holding on to the Pays de Caux

Pays de Caux

The Pays de Caux is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French département of Seine Maritime in Haute-Normandie. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary and extending to the cliffs on the English Channel coast - its coastline is known as the Côte d'Albâtre...

, while establishing good order and justice in the Duchy of Normandy. However, he was dissatisfied with the terms under which he was appointed, as he had to find much of the money to pay his troops and other expenses from his own estates. His term of office was nevertheless extended beyond the original twelve months, and he returned to England in November 1439. In spite of his position as one of the leading nobles of the realm, he was not included in Henry VI's Council on his return.

France again (1440–1445)

Henry turned to York again in 1440 after peace negotiations failed. He was reappointed Lieutenant of France on 2 July, this time with the same powers that the late Bedford had earlier been granted. As in 1437, York was able to count on the loyalty of Bedford's supporters, including Sir John Fastolf and Sir William Oldhall.However, in 1443 Henry put the newly-created John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, KG was an English noble and military commander.-Family:Baptised on 25 March 1404, he was the second son of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset and Margaret Holland, and succeeded his elder brother Henry Beaufort, 2nd Earl of Somerset to become the 3rd Earl of...

in charge of an army of 8,000 men, initially intended for the relief of Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

. This denied York much-needed men and resources at a time when he was struggling to hold the borders of Normandy. Not only that, but the terms of Somerset's appointment could have caused York to feel that his own role as effective regent over the whole of Lancastrian France was reduced to that of governor of Normandy. Somerset's army achieved nothing, and eventually returned to Normandy, where Somerset died. This may have been the start of the hatred that York felt for the Beaufort family, that would later turn into civil war.

English policy now turned back to a negotiated peace (or at least a truce) with France, so the remainder of York's time in France was spent in routine administration and domestic matters. Duchess Cecily had accompanied him to Normandy, and his children Edward

Edward IV of England

Edward IV was King of England from 4 March 1461 until 3 October 1470, and again from 11 April 1471 until his death. He was the first Yorkist King of England...

, Edmund

Edmund, Earl of Rutland

Edmund, Earl of Rutland was the fifth child and second surviving son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville...

and Elizabeth

Elizabeth of York, Duchess of Suffolk

Elizabeth of York, Duchess of Suffolk was the sixth child and third daughter of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville....

were born in Rouen

Rouen

Rouen , in northern France on the River Seine, is the capital of the Haute-Normandie region and the historic capital city of Normandy. Once one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe , it was the seat of the Exchequer of Normandy in the Middle Ages...

.

Ireland (1445–1450)

York returned to England on 20 October 1445, at the end of his five-year appointment in France. He must have had reasonable expectations of reappointment. However, he had become associated with the English in Normandy who were opposed to the policy of Henry VI's Council towards France, some of whom (for example Sir William Oldhall and Sir Andrew Ogard) had followed him to England. Eventually (in December 1446) the lieutenancy went to Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of SomersetEdmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, KG , sometimes styled 1st Duke of Somerset, was an English nobleman and an important figure in the Wars of the Roses and in the Hundred Years' War...

, who had succeeded his brother John. During 1446 and 1447 York attended meetings of Henry VI's Council and of Parliament, but most of his time was spent in administration of his estates on the Welsh border.

His attitude toward the Council's surrender of Maine, in return for an extension of the truce with France and a French bride for Henry, must have contributed to his appointment on 30 July as Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland was the British King's representative and head of the Irish executive during the Lordship of Ireland , the Kingdom of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

. In some ways it was a logical appointment, as Richard was also Earl of Ulster

Earl of Ulster

The title of Earl of Ulster has been created several times in the Peerage of Ireland and Peerage of the United Kingdom. Currently, the title is a subsidiary title of the Duke of Gloucester, and is used as a courtesy title by the Duke's son, Alexander Windsor, Earl of Ulster...

and had considerable estates in Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

, but it was also a convenient way of removing him from both England and France. His term of office was for ten years, ruling him out of consideration for any other high office during that period.

Domestic matters kept him in England until June 1449, but when he did eventually go, it was with Cecily (who was pregnant at the time) and an army of around 600 men. This suggests a stay of some time was envisaged. However, claiming lack of money to defend English possessions, York decided to return to England. His financial state may indeed have been problematic, since by the mid-1440s he was owed nearly £40,000 by the crown, and the income from his estates was declining.

Leader of the Opposition (1450–1452)

In 1450, the defeats and failures of the previous ten years boiled over into serious political unrest. In January, Adam MoleynsAdam Moleyns

Adam Moleyns was an English bishop, lawyer, royal administrator and diplomat. During the minority of Henry VI of England, he was clerk of the ruling council of the Regent.-Life:Moleyns had the living of Kempsey from 1433. He was Dean of Salisbury...

, Lord Privy Seal

Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. The office is one of the traditional sinecure offices of state...

and Bishop of Chichester

Bishop of Chichester

The Bishop of Chichester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chichester in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers the Counties of East and West Sussex. The see is in the City of Chichester where the seat is located at the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity...

, was lynched. In May the chief councillor of the King, William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk

William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk

William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, KG , nicknamed Jack Napes , was an important English soldier and commander in the Hundred Years' War, and later Lord Chamberlain of England.He also appears prominently in William Shakespeare's Henry VI, part 1 and Henry VI, part 2 and other...

, was murdered on his way into exile. The House of Commons

House of Commons of England

The House of Commons of England was the lower house of the Parliament of England from its development in the 14th century to the union of England and Scotland in 1707, when it was replaced by the House of Commons of Great Britain...

demanded that the King take back many of the grants of land and money he had made to his favourites.

In June, Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

and Sussex

Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English Sūþsēaxe , is an historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex. It is bounded on the north by Surrey, east by Kent, south by the English Channel, and west by Hampshire, and is divided for local government into West...

rose in revolt. Led by Jack Cade

Jack Cade

Jack Cade was the leader of a popular revolt in the 1450 Kent rebellion during the reign of King Henry VI in England. He died on the 12th July 1450 near Lewes. In response to grievances, Cade led an army of as many as 5,000 against London, causing the King to flee to Warwickshire. After taking and...

(taking the name Mortimer), they took control of London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

and killed John Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele

Baron Saye and Sele

Baron Saye and Sele is a title in the Peerage of England. It is thought to have been created by letters patent in 1447 for James Fiennes for his services in the Hundred Years' War. The patent creating the original barony was lost, so it was assumed that the barony was created by writ, meaning that...

, the Lord High Treasurer

Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Act of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third highest ranked Great Officer of State, below the Lord High Chancellor and above the Lord President...

of England. In August, the final towns held in Normandy fell to the French, and refugees flooded back to England.

On 7 September, York landed at Beaumaris. Evading an attempt by Henry to intercept him, and gathering followers as he went, York arrived in London on 27 September. After an inconclusive (and possibly violent) meeting with the King, York continued to recruit, both in East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

and the west. The violence in London was such that Somerset, back in England after the collapse of English Normandy, was put in the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

for his own safety. In December Parliament elected York's chamberlain, Sir William Oldhall, as speaker.

York's public stance was that of a reformer, demanding better government and the prosecution of the traitors who had lost northern France. Judging by his later actions, there may also have been a more hidden motive — the destruction of Somerset, who was soon released from the Tower. Although granted another office (Justice of the Forest south of the Trent), York still lacked any real support outside Parliament and his own retainers.

In April 1451, Somerset was released from the Tower and appointed Captain of Calais. When one of York's councillors, Thomas Young, the MP for Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

,proposed that York be recognised as heir to the throne, he was sent to the Tower and Parliament was dissolved. Henry VI was prompted into belated reforms, which went some way to restore public order and improve the royal finances. Frustrated by his lack of political power, York retired to Ludlow.

In 1452, York made another bid for power, but not to become king himself. Protesting his loyalty, he aimed to be recognised as Henry VI's heir apparent

Heir apparent

An heir apparent or heiress apparent is a person who is first in line of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting, except by a change in the rules of succession....

(Henry was childless after seven years of marriage), while also trying to destroy the Earl of Somerset, who Henry may have preferred to succeed him over York, as a Beaufort descendant. Gathering men on the march from Ludlow, York headed for London, to find the city gates barred against him on Henry's orders. At Dartford

Dartford

Dartford is the principal town in the borough of Dartford. It is situated in the northwest corner of Kent, England, east south-east of central London....

in Kent, with his army outnumbered, and the support of only two of the nobility, York was forced to come to an agreement with Henry. He was allowed to present his complaints against Somerset to the king, but was then taken to London and after two weeks of virtual house arrest

House arrest

In justice and law, house arrest is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to his or her residence. Travel is usually restricted, if allowed at all...

, was forced to swear an oath of allegiance at St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, London, is a Church of England cathedral and seat of the Bishop of London. Its dedication to Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. St Paul's sits at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London, and is the mother...

.

Protector of the Realm (1453–1454)

By the summer of 1453, York seemed to have lost his power struggle. Henry embarked on a series of judicial tours, punishing York's tenants who had been involved in the debacle at Dartford. His Queen consortQueen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king. A queen consort usually shares her husband's rank and holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles. Historically, queens consort do not share the king regnant's political and military powers. Most queens in history were queens consort...

, Margaret of Anjou, was pregnant, and even if she should miscarry, the marriage of the newly ennobled Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond

Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond

Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond , also known as Edmund of Hadham , was the father of King Henry VII of England and a member of the Tudor family of Penmynydd, North Wales.-Birth and early life:...

to Margaret Beaufort provided for an alternative line of succession. By July, York had lost both his Offices: Lieutenant of Ireland and Justice of the Forest south of the Trent.

Then, in August, Henry VI suffered a catastrophic mental breakdown. Perhaps brought on by the news of the defeat at the Battle of Castillon

Battle of Castillon

The Battle of Castillon of 1453 was the last battle fought between the French and the English during the Hundred Years' War. It resulted in a decisive French victory.-Context:...

in Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

, which finally drove English forces from France, he became completely unresponsive, unable to speak and having to be led from room to room. The council tried to carry on as though the King's disability would be brief. However, eventually they had to admit that something had to be done. In October, invitations for a Great Council were issued, and although Somerset tried to have him excluded, York (the premier Duke of the realm) was included. Somerset's fears were to prove well-grounded, for in November he was committed to the Tower. Despite the opposition of Margaret of Anjou, on 27 March, York was appointed Protector of the Realm and Chief Councillor.

York's appointment of his brother-in-law, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, jure uxoris 5th Earl of Salisbury and 7th and 4th Baron Montacute, KG, PC was a Yorkist leader during the early parts of the Wars of the Roses.-Background:...

, as Chancellor was significant. Henry's burst of activity in 1453 had seen him try to stem the violence caused by various disputes between noble families. These disputes gradually polarised around the long-standing Percy-Neville feud

Percy-Neville feud

The Percy–Neville feud was a series of skirmishes, raids and vandalism between two prominent northern English families, the House of Percy and the House of Neville, and their followers that helped provoke the Wars of the Roses.-Beginnings:...

. Unfortunately for Henry, Somerset (and therefore the king) became identified with the Percy cause. This drove the Nevilles into the arms of York, who now for the first time had support among a section of the nobility.

St. Albans (1455–1456)

According to the historian Robin Storey, "If Henry's insanity was a tragedy, his recovery was a national disaster". When he recovered his reason in January 1455, Henry lost little time in reversing York's actions. Somerset was released and restored to favour. York was deprived of the Captaincy of Calais (which was granted to Somerset once again) and of the office of Protector. Salisbury resigned as Chancellor. York, Salisbury and Salisbury's eldest son, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of WarwickRichard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick

Richard Neville KG, jure uxoris 16th Earl of Warwick and suo jure 6th Earl of Salisbury and 8th and 5th Baron Montacute , known as Warwick the Kingmaker, was an English nobleman, administrator, and military commander...

, were threatened when a Great Council was called to meet on 21 May in Leicester (away from Somerset's enemies in London). York and his Neville relations recruited in the north and probably along the Welsh border. By the time Somerset realised what was happening, there was no time to raise a large force to support the king.

Once York took his army south of Leicester, thus barring the route to the Great Council, the dispute between him and the king regarding Somerset would have to be settled by force. On 22 May, the king and Somerset arrived at St Albans

St Albans

St Albans is a city in southern Hertfordshire, England, around north of central London, which forms the main urban area of the City and District of St Albans. It is a historic market town, and is now a sought-after dormitory town within the London commuter belt...

, with a hastily-assembled and poorly-equipped army of around 2,000. York, Warwick and Salisbury were already there, with a larger and better-equipped army. More importantly, at least some of their soldiers would have had experience in the frequent border skirmishes with the Kingdom of Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

and the occasionally rebellious people of Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

.

The First Battle of St Albans

First Battle of St Albans

The First Battle of St Albans, fought on 22 May 1455 at St Albans, 22 miles north of London, traditionally marks the beginning of the Wars of the Roses. Richard, Duke of York and his ally, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, defeated the Lancastrians under Edmund, Duke of Somerset, who was killed...

which immediately followed hardly deserves the term battle. Possibly as few as 50 men were killed, but among them were Somerset and the two Percy lords, Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland

Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland

Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland was an English nobleman and military commander in the lead up to the Wars of the Roses. He was the son of Henry "Hotspur" Percy, and the grandson of Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland...

and Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford. York and the Nevilles had therefore succeeded in killing their enemies, while York's capture of the king gave him the chance to resume the power he had lost in 1453. It was vital to keep Henry alive, as his death would have led, not to York becoming king himself, but to the minority rule of his two-year-old son Edward of Westminster

Edward of Westminster

Edward of Westminster , also known as Edward of Lancaster, was the only son of King Henry VI of England and Margaret of Anjou...

. Since York's support among the nobility was small, he would be unable to dominate a minority council led by Margaret of Anjou.

In the custody of York, the king was returned to London with York and Salisbury riding alongside, and with Warwick bearing the royal sword in front. On 25 May, Henry received the crown from York, in a clearly symbolic display of power. York made himself Constable of England, and appointed Warwick Captain of Calais. York's position was enhanced when some of the nobility agreed to join his government, including Lord Fauconberg

William Neville, 1st Earl of Kent

William Neville, 1st Earl of Kent KG and jure uxoris 6th Baron Fauconberg, was an English nobleman and soldier.-Early life:...

, who had served under him in France.

For the rest of the summer York held the king prisoner, either in Hertford

Hertford

Hertford is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. Forming a civil parish, the 2001 census put the population of Hertford at about 24,180. Recent estimates are that it is now around 28,000...

castle or (in order to be enthroned in Parliament in July) in London. When Parliament met again in November the throne was empty, and it was reported that the king was ill again. York resumed the office of Protector; although he surrendered it when the king recovered in February 1456, it seemed that this time Henry was willing to accept that York and his supporters would play a major part in the government of the realm.

Salisbury and Warwick continued to serve as councillors, and Warwick was confirmed as Captain of Calais. In June, York himself was sent north to defend the border against a threatened invasion by James II of Scotland

James II of Scotland

James II reigned as King of Scots from 1437 to his death.He was the son of James I, King of Scots, and Joan Beaufort...

. However, the king once again came under the control of a dominant figure, this time one harder to replace than Suffolk or Somerset: for the rest of his reign, it would be the queen, Margaret of Anjou, who would control the king.

Loveday (1456–1458)

Although Margaret of Anjou had now taken the place formerly held by Suffolk or Somerset, her position, at least at first, was not as dominant. York had his Lieutenancy of Ireland renewed, and he continued to attend meetings of the Council. However, in August 1456 the court moved to CoventryCoventry

Coventry is a city and metropolitan borough in the county of West Midlands in England. Coventry is the 9th largest city in England and the 11th largest in the United Kingdom. It is also the second largest city in the English Midlands, after Birmingham, with a population of 300,848, although...

, in the heart of the Queen's lands. How York was treated now depended on how powerful the Queen's views were. York was regarded with suspicion on three fronts: he threatened the succession of the young Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

; he was apparently negotiating for the marriage of his eldest son Edward into the Burgundian ruling family; and as a supporter of the Nevilles, he was contributing to the major cause of disturbance in the kingdom – the Percy/Neville feud.

Here, the Nevilles lost ground. Salisbury gradually ceased to attend meetings of the council. When his brother Robert Neville

Robert Neville

Robert Neville was a Bishop of Salisbury and a Bishop of Durham. He was also a Provost of Beverley. He was born at Raby Castle. His father was Ralph Neville and his mother was Joan Beaufort, daughter of John of Gaunt. He was thus a highly-placed member of the English aristocracyNeville was...

, Bishop of Durham died in 1457, the new appointment was Laurence Booth. Booth was a member of the Queen's inner circle. The Percys were shown greater favour both at court and in the struggle for power on the Scottish Border.

Henry's attempts at reconciliation between the factions divided by the killings at St Albans reached their climax with the Loveday

Loveday

Loveday is a given name, thought to derive from the Old English Leofdaeg or alternatively Lief Tag. Leofdaeg is composed of the words leof meaning dear/beloved or precious and daeg meaning day...

on 24 March 1458. However, the lords concerned had earlier turned London into an armed camp, and the public expressions of amity seemed not to have lasted beyond the ceremony.

Ludford (1459)

In June 1459 a great council was summoned to meet at Coventry. York, the Nevilles and some other lords refused to appear, fearing that the armed forces that had been commanded to assemble the previous month had been summoned to arrest them. Instead, York and Salisbury recruited in their strongholds and met Warwick, who had brought with him his troops from Calais, at WorcesterWorcester

The City of Worcester, commonly known as Worcester, , is a city and county town of Worcestershire in the West Midlands of England. Worcester is situated some southwest of Birmingham and north of Gloucester, and has an approximate population of 94,000 people. The River Severn runs through the...

. Parliament was summoned to meet at Coventry in November, but without York and the Nevilles. This could only mean that they were to be accused of treason.

On 11 October, York tried to move south, but was forced to head for Ludlow. On 12 October, at the Battle of Ludford Bridge

Battle of Ludford Bridge

The Battle of Ludford Bridge was a largely bloodless battle fought in the early years of the Wars of the Roses. It took place on 12 October 1459, and resulted in a disastrous defeat for the Yorkists.-Background:...

, York once again faced Henry just as he had at Dartford seven years earlier. Warwick's troops from Calais refused to fight, and the rebels fled – York to Ireland, Warwick, Salisbury and York's son Edward to Calais. York's wife Cecily and their two younger sons (George

George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence

George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, 1st Earl of Salisbury, 1st Earl of Warwick, KG was the third son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, and the brother of kings Edward IV and Richard III. He played an important role in the dynastic struggle known as the Wars of the...

and Richard

Richard III of England

Richard III was King of England for two years, from 1483 until his death in 1485 during the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty...

) were captured in Ludlow Castle

Ludlow Castle

Ludlow Castle is a large, partly ruined, non-inhabited castle which dominates the town of Ludlow in Shropshire, England. It stands on a high point overlooking the River Teme...

and imprisoned at Coventry

Coventry

Coventry is a city and metropolitan borough in the county of West Midlands in England. Coventry is the 9th largest city in England and the 11th largest in the United Kingdom. It is also the second largest city in the English Midlands, after Birmingham, with a population of 300,848, although...

.

The wheel of fortune (1459–1460)

York's flight worked to his advantage. He was still Lieutenant of Ireland, and attempts to replace him failed. The Parliament of IrelandParliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

backed him, providing offers of both military and financial support. Warwick's (possibly inadvertent) return to Calais also proved fortunate. His control of the English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

meant that pro-Yorkist propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

, emphasising loyalty to the king while decrying his wicked councillors, could be spread around Southern England

Southern England

Southern England, the South and the South of England are imprecise terms used to refer to the southern counties of England bordering the English Midlands. It has a number of different interpretations of its geographic extents. The South is considered by many to be a cultural region with a distinct...

. Such was the Yorkists' naval dominance that Warwick was able to sail to Ireland in March 1460, meet York and return to Calais in May. Warwick's control of Calais was to prove to be influential with the wool-merchants in London.

In December 1459 York, Warwick and Salisbury had suffered attainder. Their lives were forfeit, and their lands reverted to the king; their heirs would not inherit. This was the most extreme punishment a member of the nobility could suffer, and York was now in the same situation as Henry of Bolingbroke

Henry IV of England

Henry IV was King of England and Lord of Ireland . He was the ninth King of England of the House of Plantagenet and also asserted his grandfather's claim to the title King of France. He was born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, hence his other name, Henry Bolingbroke...

in 1398. Only a successful invasion of England would restore his fortune. Assuming the invasion was successful, York had three options — become Protector again, disinherit the king so that York's son would succeed, or claim the throne for himself.

On 26 June, Warwick and Salisbury landed at Sandwich

Sandwich, Kent

Sandwich is a historic town and civil parish on the River Stour in the Non-metropolitan district of Dover, within the ceremonial county of Kent, south-east England. It has a population of 6,800....

. The men of Kent, always ready to revolt, rose to join them. London opened its gates to the Nevilles on 2 July. They marched north into the Midlands, and on 10 July, they defeated the royal army at the Battle of Northampton

Battle of Northampton (1460)

The Battle of Northampton was a battle in the Wars of the Roses, which took place on 10 July 1460.-Background:The Yorkist cause seemed finished after the previous disaster at Ludford Bridge...

(through treachery among the King's troops), and captured Henry, who they brought back to London.

York remained in Ireland. He did not set foot in England until 9 September, and when he did, he acted as a king. Marching under the arms of his maternal great-great-grandfather Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence

Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence

Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, jure uxoris 4th Earl of Ulster and 5th Baron of Connaught, KG was the third son, but the second son to survive infancy, of Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault...

, as he approached London he displayed a banner of the Coat of Arms of England

Coat of arms of England

In heraldry, the Royal Arms of England is a coat of arms symbolising England and its monarchs. Its blazon is Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or armed and langued Azure, meaning three identical gold lions with blue tongues and claws, walking and facing the observer, arranged in a column...

.

A Parliament which was called to meet on 7 October repealed all the legislation of the Coventry parliament the previous year. On 10 October, York arrived in London and took residence in the royal palace. Entering Parliament with his sword borne upright before him, he made for the empty throne and placed his hand upon it, as if to occupy it. He may have expected the assembled peers to acclaim him as King, as they had acclaimed Henry Bolingbroke

Henry IV of England

Henry IV was King of England and Lord of Ireland . He was the ninth King of England of the House of Plantagenet and also asserted his grandfather's claim to the title King of France. He was born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, hence his other name, Henry Bolingbroke...

in 1399. Instead, there was silence. Tmhomas Bouchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, asked whether he wished to see the King. York replied, "I know of no person in this realm the which oweth not to wait on me, rather than I of him." This high-handed reply did not impress the Lords.

The next day, Richard advanced his claim to the crown by hereditary right, in proper form. However, his narrow support among his peers led to failure once again. After weeks of negotiation, the best that could be achieved was the Act of Accord

Act of Accord

The Act of Accord was passed by the English Parliament on 25 October 1460, fifteen days after Richard, Duke of York had entered the Council Chamber and laid his hand on the empty throne. Under the Act, King Henry VI of England was to retain the crown for life but York and his heirs were to succeed....

, by which York and his heirs were recognised as Henry's successor. However, Parliament did grant York extraordinary executive powers to protect the realm, and with the king effectively in custody, York and Warwick were the de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

rulers of the country.

Final campaign and death

While this was happening, the Lancastrian loyalists were rallying and arming in the north of England. Faced with the threat of attack from the Percys, and with Margaret of Anjou trying to gain the support of new king James III of ScotlandJames III of Scotland

James III was King of Scots from 1460 to 1488. James was an unpopular and ineffective monarch owing to an unwillingness to administer justice fairly, a policy of pursuing alliance with the Kingdom of England, and a disastrous relationship with nearly all his extended family.His reputation as the...

, York, Salisbury and York's second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland

Edmund, Earl of Rutland

Edmund, Earl of Rutland was the fifth child and second surviving son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville...

headed north on 2 December. They arrived at York's stronghold of Sandal Castle

Sandal Castle

Sandal Castle is a ruined medieval castle in Sandal Magna, a suburb of the city of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, overlooking the River Calder. It was the site of royal intrigue, the opening of one of William Shakespeare's plays, and was the source for a common children's nursery rhyme.-The...

on 21 December to find the situation bad and getting worse. Forces loyal to Henry controlled the city of York, and nearby Pontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle is a castle in the town of Pontefract, in the City of Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. It was the site of the demise of Richard II of England, and later the place of a series of famous sieges during the English Civil War-History:...

was also in hostile hands.

On 30 December, York and his forces sortied from Sandal Castle. Their reasons for doing so are not clear; they were variously claimed to be a result of deception by the Lancastrian forces, or treachery, or simple rashness on York's part. The larger Lancastrian force destroyed York's army in the resulting Battle of Wakefield

Battle of Wakefield

The Battle of Wakefield took place at Sandal Magna near Wakefield, in West Yorkshire in Northern England, on 30 December 1460. It was a major battle of the Wars of the Roses...

. York was killed in the battle. Edmund of Rutland was intercepted as he tried to flee and was executed, possibly by John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford

John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford

John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford, also 9th Lord of Skipton was a Lancastrian military leader during the Wars of the Roses...

in revenge for the death of his own father at the First Battle of St Albans. Salisbury escaped but was captured and executed the following night.

York was buried at Pontefract

Pontefract

Pontefract is an historic market town in West Yorkshire, England. Traditionally in the West Riding, near the A1 , the M62 motorway and Castleford. It is one of the five towns in the metropolitan borough of the City of Wakefield and has a population of 28,250...