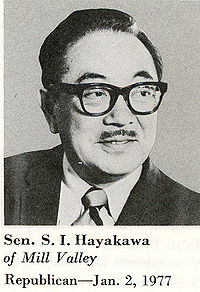

S. I. Hayakawa

Encyclopedia

Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa (July 18, 1906 – February 27, 1992) was a Canadian-born American

academic and political figure of Japan

ese ancestry. He was an English

professor, and served as president of San Francisco State University

and then as United States Senator

from California

from 1977 to 1983. Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

, he was educated in the public schools of Calgary

, Alberta

and Winnipeg, Manitoba and received an undergraduate degree from the University of Manitoba

in 1927 and graduate degrees in English from McGill University

in 1928 and the University of Wisconsin–Madison

in 1935.

, semanticist

, teacher and writer. He was an instructor at the University of Wisconsin from 1936 to 1939 and at Armour Institute of Technology (now Illinois Institute of Technology

) from 1939 to 1948. Hayakawa was an important semanticist. His first book on the subject, Language in Thought and Action

, was published in 1949 as an expansion of the earlier work, Language in Action, written since 1938 and published in 1941 to be a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. It is currently in its fifth edition and has greatly helped popularize Alfred Korzybski's

general semantics

and in effect semantics

in general, while semantics or theory of meaning was overwhelmed by mysticism

, propagandism and even scientism

. In the preface, Hayakawa cautioned:

In addition to such motivation, he acknowledged his debt as follows:

He was a lecturer at the University of Chicago

from 1950 to 1955. During this time he presented a talk at the 1954 Conference of Activity Vector Analysts at Lake George, New York in which he discussed a theory of personality from the semantic point of view. This was later published as The Semantic Barrier. This was a definitive lecture as it discussed the Darwinism

of the "survival of self" as contrasted with the "survival of self-concept

".

Hayakawa was an English professor at San Francisco State College

(now called San Francisco State University) from 1955 to 1968. In the early 1960s, he helped organize the Anti Digit Dialing League, a group in San Francisco that opposed the introduction of all digit telephone exchange names

. Among the students he trained were commune leader Stephen Gaskin

and author Gerald Haslam

. He became president of San Francisco State College during the turbulent period of 1968 to 1973, becoming president emeritus in 1973 and then wrote a column for the Register & Tribune Syndicate from 1970 to 1976.

and the Bay Area. The strike was led by the Third World Liberation Front supported by Students for a Democratic Society

, the Black Panthers and the counter-cultural community, among others. It demanded an end to racism, creation of an Ethnic Studies Department, to be chaired by sociologist Nathan Hare

, an end to the War in Vietnam and the university's complicity with it. Hayakawa became popular with conservative voters in this period after he pulled the wires out from the speakers on a student van at an outdoor rally, dramatically disrupting it. Hayakawa relented on December 6, 1968 and created the first-in-the-nation College of Ethnic Studies https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/187205. He also drew the ire of student protesters with several other actions, such as throwing the first rock to destroy the Student Center (making way for a new one to be built), and removing most of the student traditions, such as a school song, school yearbook, etc.

Hayakawa was elected in California

Hayakawa was elected in California

to the United States Senate as a Republican

in 1976, defeating incumbent

Democrat

John V. Tunney

. Hayakawa served from January 3, 1977, to January 3, 1983. He did not run for reelection in 1982 and was succeeded by Republican Pete Wilson

.

Hayakawa founded the political lobbying organization U.S. English, which is dedicated to making the English language

the official language

of the United States

.

Hayakawa was a resident of Mill Valley, California

, until his death in nearby Greenbrae

, in 1992. He was also a member of the Bohemian Club

. He had an abiding interest in traditional jazz and wrote extensively on that subject, including several erudite sets of album liner notes

. Sometimes in his lectures on semantics, he was joined by the respected traditional jazz pianist

, Don Ewell

, whom Hayakawa employed to demonstrate various points in which he analyzed semantic and musical principles.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

academic and political figure of Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese ancestry. He was an English

English studies

English studies is an academic discipline that includes the study of literatures written in the English language , English linguistics English studies is an academic discipline that includes the study of literatures written in the English language (including literatures from the U.K., U.S.,...

professor, and served as president of San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University is a public university located in San Francisco, California. As part of the 23-campus California State University system, the university offers over 100 areas of study from nine academic colleges...

and then as United States Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

from 1977 to 1983. Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, he was educated in the public schools of Calgary

Calgary

Calgary is a city in the Province of Alberta, Canada. It is located in the south of the province, in an area of foothills and prairie, approximately east of the front ranges of the Canadian Rockies...

, Alberta

Alberta

Alberta is a province of Canada. It had an estimated population of 3.7 million in 2010 making it the most populous of Canada's three prairie provinces...

and Winnipeg, Manitoba and received an undergraduate degree from the University of Manitoba

University of Manitoba

The University of Manitoba , in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, is the largest university in the province of Manitoba. It is Manitoba's most comprehensive and only research-intensive post-secondary educational institution. It was founded in 1877, making it Western Canada’s first university. It placed...

in 1927 and graduate degrees in English from McGill University

McGill University

Mohammed Fathy is a public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The university bears the name of James McGill, a prominent Montreal merchant from Glasgow, Scotland, whose bequest formed the beginning of the university...

in 1928 and the University of Wisconsin–Madison

University of Wisconsin–Madison

The University of Wisconsin–Madison is a public research university located in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. Founded in 1848, UW–Madison is the flagship campus of the University of Wisconsin System. It became a land-grant institution in 1866...

in 1935.

Academic career

Professionally, Hayakawa was a linguist, psychologistPsychologist

Psychologist is a professional or academic title used by individuals who are either:* Clinical professionals who work with patients in a variety of therapeutic contexts .* Scientists conducting psychological research or teaching psychology in a college...

, semanticist

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning. It focuses on the relation between signifiers, such as words, phrases, signs and symbols, and what they stand for, their denotata....

, teacher and writer. He was an instructor at the University of Wisconsin from 1936 to 1939 and at Armour Institute of Technology (now Illinois Institute of Technology

Illinois Institute of Technology

Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly called Illinois Tech or IIT, is a private Ph.D.-granting university located in Chicago, Illinois, with programs in engineering, science, psychology, architecture, business, communications, industrial technology, information technology, design, and law...

) from 1939 to 1948. Hayakawa was an important semanticist. His first book on the subject, Language in Thought and Action

Language in Thought and Action

Language in Thought and Action is a book on semantics by Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa, based on his previous work Language in Action published in 1939. Early editions were written in consultation with different people. The current 5th edition was published in 1991. It was updated by Hayakawa's son, Alan...

, was published in 1949 as an expansion of the earlier work, Language in Action, written since 1938 and published in 1941 to be a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. It is currently in its fifth edition and has greatly helped popularize Alfred Korzybski's

Alfred Korzybski

Alfred Habdank Skarbek Korzybski was a Polish-American philosopher and scientist. He is remembered for developing the theory of general semantics...

general semantics

General Semantics

General semantics is a program begun in the 1920's that seeks to regulate the evaluative operations performed in the human brain. After partial program launches under the trial names "human engineering" and "humanology," Polish-American originator Alfred Korzybski fully launched the program as...

and in effect semantics

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning. It focuses on the relation between signifiers, such as words, phrases, signs and symbols, and what they stand for, their denotata....

in general, while semantics or theory of meaning was overwhelmed by mysticism

Mysticism

Mysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

, propagandism and even scientism

Scientism

Scientism refers to a belief in the universal applicability of the systematic methods and approach of science, especially the view that empirical science constitutes the most authoritative worldview or most valuable part of human learning to the exclusion of other viewpoints...

. In the preface, Hayakawa cautioned:

In addition to such motivation, he acknowledged his debt as follows:

He was a lecturer at the University of Chicago

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

from 1950 to 1955. During this time he presented a talk at the 1954 Conference of Activity Vector Analysts at Lake George, New York in which he discussed a theory of personality from the semantic point of view. This was later published as The Semantic Barrier. This was a definitive lecture as it discussed the Darwinism

Darwinism

Darwinism is a set of movements and concepts related to ideas of transmutation of species or of evolution, including some ideas with no connection to the work of Charles Darwin....

of the "survival of self" as contrasted with the "survival of self-concept

Self-concept

Self-concept is a multi-dimensional construct that refers to an individual's perception of "self" in relation to any number of characteristics, such as academics , gender roles and sexuality, racial identity, and many others. Each of these characteristics is a research domain Self-concept (also...

".

Hayakawa was an English professor at San Francisco State College

San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University is a public university located in San Francisco, California. As part of the 23-campus California State University system, the university offers over 100 areas of study from nine academic colleges...

(now called San Francisco State University) from 1955 to 1968. In the early 1960s, he helped organize the Anti Digit Dialing League, a group in San Francisco that opposed the introduction of all digit telephone exchange names

Telephone exchange names

During the early years of telephone service, communities that required more than 10,000 telephone numbers, whether dial service was available or not, utilized exchange names to distinguish identical numerics for different customers....

. Among the students he trained were commune leader Stephen Gaskin

Stephen Gaskin

Stephen Gaskin is a counterculture hippie icon best known for his presence in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco in the 1960s and for co-founding "The Farm", a famous spiritual intentional community in Summertown, Tennessee...

and author Gerald Haslam

Gerald Haslam

Gerald William Haslam is the author credited with having created an awareness of "the other California" , the state's untrendy small town and rural reaches...

. He became president of San Francisco State College during the turbulent period of 1968 to 1973, becoming president emeritus in 1973 and then wrote a column for the Register & Tribune Syndicate from 1970 to 1976.

Student strike at San Francisco State University

During 1968-69, there was a bitter student strike at San Francisco State University for the purpose of gaining an Ethnic Studies program. It was a major news event at the time and chapter in the radical history of the United StatesUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and the Bay Area. The strike was led by the Third World Liberation Front supported by Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (1960 organization)

Students for a Democratic Society was a student activist movement in the United States that was one of the main iconic representations of the country's New Left. The organization developed and expanded rapidly in the mid-1960s before dissolving at its last convention in 1969...

, the Black Panthers and the counter-cultural community, among others. It demanded an end to racism, creation of an Ethnic Studies Department, to be chaired by sociologist Nathan Hare

Nathan Hare

Nathan Hare was the first person hired to coordinate a black studies program in the United States, at San Francisco State University in 1968.-Early life and education:...

, an end to the War in Vietnam and the university's complicity with it. Hayakawa became popular with conservative voters in this period after he pulled the wires out from the speakers on a student van at an outdoor rally, dramatically disrupting it. Hayakawa relented on December 6, 1968 and created the first-in-the-nation College of Ethnic Studies https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/187205. He also drew the ire of student protesters with several other actions, such as throwing the first rock to destroy the Student Center (making way for a new one to be built), and removing most of the student traditions, such as a school song, school yearbook, etc.

Political career

United States Senate election in California, 1976

The 1976 United States Senate election in California took place on November 3, 1976. Incumbent Democratic senator John Tunney sought election to a second term. He was defeated by Republican challenger S. I. "Sam" Hayakawa.-Results:-References:...

to the United States Senate as a Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

in 1976, defeating incumbent

Incumbent

The incumbent, in politics, is the existing holder of a political office. This term is usually used in reference to elections, in which races can often be defined as being between an incumbent and non-incumbent. For example, in the 2004 United States presidential election, George W...

Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

John V. Tunney

John V. Tunney

John Varick Tunney , is a former Democratic Party United States Senator and Representative.-Biography:He is the son of the famous heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney and Connecticut socialite Polly Lauder Tunney....

. Hayakawa served from January 3, 1977, to January 3, 1983. He did not run for reelection in 1982 and was succeeded by Republican Pete Wilson

Pete Wilson

Peter Barton "Pete" Wilson is an American politician from California. Wilson, a Republican, served as the 36th Governor of California , the culmination of more than three decades in the public arena that included eight years as a United States Senator , eleven years as Mayor of San Diego and...

.

Hayakawa founded the political lobbying organization U.S. English, which is dedicated to making the English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

the official language

Official language

An official language is a language that is given a special legal status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically a nation's official language will be the one used in that nation's courts, parliament and administration. However, official status can also be used to give a...

of the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

.

Hayakawa was a resident of Mill Valley, California

Mill Valley, California

Mill Valley is a city in Marin County, California, United States located about north of San Francisco via the Golden Gate Bridge. The population was 13,903 at the 2010 census.Mill Valley is located on the western and northern shores of Richardson Bay...

, until his death in nearby Greenbrae

Greenbrae, California

Greenbrae is a small community in Marin County, California. It is located south-southeast of downtown San Rafael, at an elevation of 33 feet , located adjacent to U.S. Route 101 at the opening of the Ross Valley. Part of Greenbrae is an unincorporated community of the county while the remaining...

, in 1992. He was also a member of the Bohemian Club

Bohemian Club

The Bohemian Club is a private men's club in San Francisco, California, United States.Its clubhouse is located at 624 Taylor Street in San Francisco...

. He had an abiding interest in traditional jazz and wrote extensively on that subject, including several erudite sets of album liner notes

Liner notes

Liner notes are the writings found in booklets which come inserted into the compact disc jewel case or the equivalent packaging for vinyl records and cassettes.-Origin:...

. Sometimes in his lectures on semantics, he was joined by the respected traditional jazz pianist

Jazz piano

Jazz piano is a collective term for the techniques pianists use when playing jazz. The piano has been an integral part of the jazz idiom since its inception, in both solo and ensemble settings. Its role is multifaceted due largely to the instrument's combined melodic and harmonic capabilities...

, Don Ewell

Don Ewell

Don Ewell was an American jazz stride pianist born in Baltimore, Maryland, perhaps best known for his work with several prominent New Orleans–based musicians such as Sidney Bechet, Kid Ory, George Lewis, George Brunis, Muggsy Spanier and Bunk Johnson.From 1956 to 1962, Ewell was a leading member...

, whom Hayakawa employed to demonstrate various points in which he analyzed semantic and musical principles.

In popular culture

- Hayakawa's work in General Semantics is referred to extensively in A.E. Van Vogt's Null-A novels, The World of Null-AThe World of Null-AThe World of Null-A, sometimes written The World of Ā, is a 1948 science fiction novel by A. E. van Vogt. It was originally published as a three-part serial in Astounding Stories...

and The Pawns of Null-A. - Hayakawa is mentioned in the voice-over in the coda of Stevie WonderStevie WonderStevland Hardaway Morris , better known by his stage name Stevie Wonder, is an American singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, record producer and activist...

's song "Black Man," from the album Songs in the Key of LifeSongs in the Key of LifeSongs in the Key of Life is the 13th album by American recording artist Stevie Wonder, released September 28, 1976, on Motown Records. It was the culmination of his "classic period" albums. An ambitious double LP with a 4-song bonus EP, Songs in the Key of Life became among the best-selling and...

.

See also

- Membership discrimination in California social clubs