Smithfield, London

Encyclopedia

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

, in the ward of Farringdon Without

Farringdon Without

Farringdon Without is a Ward in the City of London, England. The Ward covers the western fringes of the City, including the Middle Temple, Inner Temple, Smithfield Market and St Bartholomew's Hospital, as well as the area east of Chancery Lane...

. It is located in the north-west part of the City, and is mostly known for its centuries-old meat market, today the last surviving historical wholesale

Wholesale

Wholesaling, jobbing, or distributing is defined as the sale of goods or merchandise to retailers, to industrial, commercial, institutional, or other professional business users, or to other wholesalers and related subordinated services...

market in Central London. Smithfield has a bloody history of executions of heretics and political opponents, including major historical figures such as Scottish patriot William Wallace

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight and landowner who became one of the main leaders during the Wars of Scottish Independence....

, Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler

Walter "Wat" Tyler was a leader of the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381.-Early life:Knowledge of Tyler's early life is very limited, and derives mostly through the records of his enemies. Historians believe he was born in Essex, but are not sure why he crossed the Thames Estuary to Kent...

, the leader of the Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

, and a long series of religious reformers and dissenters.

Today, the Smithfield area is dominated by the imposing, Grade II listed covered market designed by Victorian architect Sir Horace Jones in the second half of the 19th century. Some of the original market buildings were abandoned for decades and faced a threat of demolition, but they were saved as the result of a public inquiry and will be part of new urban development plans aimed at preserving the historical identity of this area.

The area

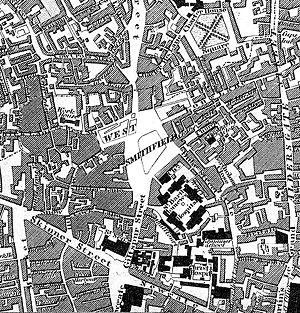

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

Smithfield was a broad grassy space known as Smooth Field, just outside the London Wall

London Wall

London Wall was the defensive wall first built by the Romans around Londinium, their strategically important port town on the River Thames in what is now the United Kingdom, and subsequently maintained until the 18th century. It is now the name of a road in the City of London running along part of...

, on the eastern bank of the River Fleet

River Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers. Its two headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath; each is now dammed into a series of ponds made in the 18th century, the Hampstead Ponds and the Highgate Ponds. At the south edge of Hampstead Heath these two streams flow...

. Due to its access to grazing and water, it was used as the City's main livestock

Livestock

Livestock refers to one or more domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to produce commodities such as food, fiber and labor. The term "livestock" as used in this article does not include poultry or farmed fish; however the inclusion of these, especially poultry, within the meaning...

market for nearly 1000 years. Many toponyms in the area are associated to the trading of livestock: while some of these street names (such as "Cow Cross Street" and "Cock Lane

Cock Lane

Cock Lane is a small street in Smithfield, London, leading from Giltspur Street to the east to Snow Hill, to the west. In the medieval period it was known as Cokkes Lane and was the site of legal brothels...

") are still in use, many more (such as "Chick Lane", "Duck Lane", "Cow Lane", "Pheasant Court", "Goose Alley") have disappeared from the maps since the major Victorian redevelopment of the area.

Religious history

In 1123, the land closest to AldersgateAldersgate

Aldersgate was a gate in the London Wall in the City of London, which has given its name to a ward and Aldersgate Street, a road leading north from the site of the gate, towards Clerkenwell in the London Borough of Islington.-History:...

was granted for the foundation of St Bartholomew's Priory by Rahere

Rahere

Rahere was clergyman and a favourite of King Henry I. He is most famous for having founded St Bartholomew's Hospital in 1123....

; as thanks for surviving an illness. The Priory enclosed the land between Aldersgate (to the east), Long Lane (in the north) and the modern Newgate Street

Newgate

Newgate at the west end of Newgate Street was one of the historic seven gates of London Wall round the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. From it a Roman road led west to Silchester...

(to the south). The main western gate opened on Smithfield; and there was a postern

Postern

A postern is a secondary door or gate, particularly in a fortification such as a city wall or castle curtain wall. Posterns were often located in a concealed location, allowing the occupants to come and go inconspicuously. In the event of a siege, a postern could act as a sally port, allowing...

to Long Lane. The Priory was also granted the rights to a weekly fair; and this was established within the outer court along the line of the modern Cloth Fair

Cloth Fair

Cloth Fair is a street in the City of London, England. It was the site where medieval merchants gathered to buy and sell material during Bartholomew Fair...

; leading to a Fair Gate. A further annual fair was added in 1133, the Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy is a comedy in five acts by Ben Jonson, the last written of his four great comedies. It was first staged on October 31, 1614 at the Hope Theatre by the Lady Elizabeth's Men...

, one of London's pre-eminent summer fair

Fair

A fair or fayre is a gathering of people to display or trade produce or other goods, to parade or display animals and often to enjoy associated carnival or funfair entertainment. It is normally of the essence of a fair that it is temporary; some last only an afternoon while others may ten weeks. ...

s, opening each year on 24 August. A trading event for cloth and other goods as well as a pleasure fair, the four-day event drew crowds from all classes of English society. The fair was suppressed in 1855 by the City authorities for encouraging debauchery and public disorder.

In 1348, Walter de Manny rented 13 acre (0.05260918 km²) of land in Spital Croft, north of Long Lane, from the Master and Brethren of St. Bartholomew's Hospital for a graveyard and plague pit for victims of the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

. A chapel and hermitage were constructed, renamed New Church Haw; but in 1371, this land was granted for the foundation of the London Charterhouse

London Charterhouse

The London Charterhouse is a historic complex of buildings in Smithfield, London dating back to the 14th century. It occupies land to the north of Charterhouse Square. The Charterhouse began as a Carthusian priory, founded in 1371 and dissolved in 1537...

, a Carthusian

Carthusian

The Carthusian Order, also called the Order of St. Bruno, is a Roman Catholic religious order of enclosed monastics. The order was founded by Saint Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns...

monastery.

A little to the north of the district was established the Priory of St John of Jerusalem, an order of the Knights Hospitaller

Knights Hospitaller

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta , also known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta , Order of Malta or Knights of Malta, is a Roman Catholic lay religious order, traditionally of military, chivalrous, noble nature. It is the world's...

s. This was in existence by the mid 12th century, but not granted a charter until 1194. To the north of the Hospitallers was a priory of Augustinian canonesses; the Priory of St. Mary at Clerkenwell.

By the end of the 14th century, the religious houses were regarded as interlopers — occupying what had previously been public open space near one of the City gates. On a number of occasions the Charterhouse was invaded and buildings destroyed. By 1405, a stout wall was built to protect the property and maintain the privacy of the order, particularly the church where women had come to worship.

The religious houses were dissolved

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

in the reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

, and their lands broken up. The priory church of St John's still exists, a little to the north of Old Street

Old Street

Old Street is a street in east London that runs west to east from Goswell Road in Clerkenwell, in the London Borough of Islington, to the crossroads where it intersects with Shoreditch High Street , Kingsland Road and Hackney Road in Shoreditch in the London Borough of Hackney.The nearest...

, and is now the chapel of the Order of St John

Venerable Order of Saint John

The Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem , is a royal order of chivalry established in 1831 and found today throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Hong Kong, Ireland and the United States of America, with the world-wide mission "to prevent and relieve sickness and...

. The St John's gate

St John's Gate, Clerkenwell

St John's Gate is one of the few tangible remains from Clerkenwell's monastic past; it was built in 1504 by Prior Thomas Docwra as the south entrance to the inner precinct of the Priory of the Knights of Saint John - the Knights Hospitallers. The substructure is of brick, the north and south...

remains, forming the boundary between Smithfield and Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell is an area of central London in the London Borough of Islington. From 1900 to 1965 it was part of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. The well after which it was named was rediscovered in 1924. The watchmaking and watch repairing trades were once of great importance...

. John Houghton, the prior of the London Charterhouse, went to Thomas Cromwell with priors from two other houses to obtain an oath of supremacy

Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy, originally imposed by King Henry VIII of England through the Act of Supremacy 1534, but repealed by his daughter, Queen Mary I of England and reinstated under Mary's sister, Queen Elizabeth I of England under the Act of Supremacy 1559, provided for any person taking public or...

that would be acceptable to their communities. They were flung in the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

; and on 4 May 1535, they were taken to Tyburn

Tyburn, London

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex close to the current location of Marble Arch in present-day London. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream', a tributary of the River Thames which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the...

and hanged — becoming the first Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

martyr

Carthusian Martyrs

The Carthusian Martyrs were a group of monks of the London Charterhouse, the monastery of the Carthusian Order in central London, who were put to death by the English state from June 19, 1535 to September 20, 1537. The method of execution was hanging, disembowelling while still alive and then...

s of the Reformation. On 29 May, the remaining twenty monks and eighteen lay brothers were required to take the oath; those ten refusing were taken to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

and left to starve. With the monks expelled, Charterhouse became a private house, before the foundation by Thomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton was an English civil servant and businessman as well as being the founder of Charterhouse School. He was the son of an official of the city of Lincoln, and was educated at Eton College and probably at Cambridge...

in 1611 of a charitable foundation forming the school named Charterhouse

Charterhouse School

Charterhouse School, originally The Hospital of King James and Thomas Sutton in Charterhouse, or more simply Charterhouse or House, is an English collegiate independent boarding school situated at Godalming in Surrey.Founded by Thomas Sutton in London in 1611 on the site of the old Carthusian...

and almshouse

Almshouse

Almshouses are charitable housing provided to enable people to live in a particular community...

s known as Sutton's Hospital in Charterhouse on the site. Some of the buildings were damaged in The Blitz

The Blitz

The Blitz was the sustained strategic bombing of Britain by Nazi Germany between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, during the Second World War. The city of London was bombed by the Luftwaffe for 76 consecutive nights and many towns and cities across the country followed...

. The school moved to Godalming

Godalming

Godalming is a town and civil parish in the Waverley district of the county of Surrey, England, south of Guildford. It is built on the banks of the River Wey and is a prosperous part of the London commuter belt. Godalming shares a three-way twinning arrangement with the towns of Joigny in France...

in 1872, and the site is now occupied by a part of Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry. Charterhouse was an extra-parochial area

Extra-parochial area

In the United Kingdom, an extra-parochial area or extra-parochial place was an area considered to be outside any parish. They were therefore exempt from payment of any poor or church rate and usually tithe...

, becoming a civil parish in its own right that was incorporated into the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury

Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury

The Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury was a Metropolitan borough within the County of London from 1900 to 1965, when it was amalgamated with the Metropolitan Borough of Islington to form the London Borough of Islington.- Boundaries :...

in 1899.

From its inception, the priory of St Bartholomew had treated the sick. The Reformation left it with neither income nor monastic occupants. After a petition by the City authorities, Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

refounded it in December 1546, as the "House of the Poore in West Smithfield in the suburbs of the City of London of Henry VIII's Foundation". Letters patent

Letters patent

Letters patent are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch or president, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, title, or status to a person or corporation...

were presented to the City, granting property and income to the new foundation the following month. The King's own sergeant-surgeon Thomas Vicary

Thomas Vicary

Thomas Vicary was an early English physician, surgeon and anatomist.Vicary was born in Kent, in about 1490. He was, "but a meane practiser in Maidstone … that had gayned his knowledge by experience, until the King advanced him for curing his sore legge” Henry VIII advanced him to the position of...

was appointed first superintendent of the hospital The King Henry VIII Gate, constructed in 1702, still forms the principal entrance to the hospital.

The principal church of the priory, St Bartholomew-the-Great

St Bartholomew-the-Great

The Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great is an Anglican church located at West Smithfield in the City of London, founded as an Augustinian priory in 1123 -History:...

, was shortened, losing the western third of the nave, and became the Anglican

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

parish church

Parish church

A parish church , in Christianity, is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish, the basic administrative unit of episcopal churches....

of a parish that followed the former boundary of the priory and the thin strip between the church and Long Lane. This parish was a liberty

Liberty (division)

Originating in the Middle Ages, a liberty was traditionally defined as an area in which regalian rights were revoked and where land was held by a mesne lord...

, and until 1910 maintained its own gates, which were shut at night by watchmen. The provision of street lighting, mains water and sewerage were beyond the means of such a small parish; and in 1910 the parish was reincorporated into the City of London. The boundary of the parish extends about 10 feet into Smithfield — possibly marking the site of a former road.

The hospital formed its own separate parish, around the parish church of St Bartholomew-the-Less

St Bartholomew-the-Less

St Bartholomew-the-Less is an Anglican church in the City of London. It is the official church of St Bartholomew's Hospital and is located within the hospital grounds.-History:...

— unique amongst English hospitals. In 1948, the hospital became part of the National Health Service

National Health Service

The National Health Service is the shared name of three of the four publicly funded healthcare systems in the United Kingdom. They provide a comprehensive range of health services, the vast majority of which are free at the point of use to residents of the United Kingdom...

and adopted the name St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as Barts, is a hospital in Smithfield in the City of London, England.-Early history:It was founded in 1123 by Raherus or Rahere , a favourite courtier of King Henry I...

.

The status of the former priory created the two parishes of St Bartholomew's. These had historically been associated with the parish of St Botolph Aldersgate

St Botolph Aldersgate

St Botolph's-without-Aldersgate is a Church of England church on Aldersgate Street in the City of London, dedicated to St Botolph. The church is renowned for its beautiful interior and historic organ....

— leading to disputes over the tithes and taxes due from lay residents, after the dissolution. Smithfield and the market was part of the parish of St Sepulchre

St Sepulchre

St Sepulchre was an ancient parish partly within the City of London and partly within Middlesex, England.For civil purposes it was divided into two civil parishes, each called St Sepulchre, although the parish in the City of London was also known as St Sepulchre without Newgate...

. It was founded in 1137, with a benefice granted by Rahere. This parish extended from Turnmill Street in the north to St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, London, is a Church of England cathedral and seat of the Bishop of London. Its dedication to Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. St Paul's sits at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London, and is the mother...

and Ludgate Hill

Ludgate Hill

Ludgate Hill is a hill in the City of London, near the old Ludgate, a gate to the City that was taken down, with its attached gaol, in 1780. Ludgate Hill is the site of St Paul's Cathedral, traditionally said to have been the site of a Roman temple of the goddess Diana. It is one of the three...

in the south, along the banks of the Fleet (now the course of Farringdon Street). The church bell tower holds the twelve "bells of Old Bailey" from the nursery rhyme Oranges and Lemons

Oranges and Lemons

"Oranges and Lemons" is an English nursery rhyme and singing game which refers to the bells of several churches, all within or close to the City of London. It is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index as #3190.-Lyrics:Common modern versions include:...

. Traditionally, the Great Bell was rung to announce the execution of prisoners at Newgate.

Civil history

As a large open space close to the city, Smithfield was a favourite place for public gatherings. In 1374 Edward III held a seven-day tournament in Smithfield, for the amusement of his beloved Alice PerrersAlice Perrers

Alice Perrers was a royal mistress whose lover and patron was King Edward III of England. She acquired significant land holdings. She served as a lady-in-waiting to Edward's consort, Philippa of Hainault.-Life and Family:...

. Possibly the most famous tournament in medieval Smithfield was the one ordered in 1390 by Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

. Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart , often referred to in English as John Froissart, was one of the most important chroniclers of medieval France. For centuries, Froissart's Chronicles have been recognized as the chief expression of the chivalric revival of the 14th century Kingdom of England and France...

, in the fourth book of his Chronicles

Froissart's Chronicles

Froissart's Chronicles was written in French by Jean Froissart. It covers the years 1322 until 1400 and describes the conditions that created the Hundred Years' War and the first fifty years of the conflict...

, reports that sixty knights would come to London to tilt for two days, "accompanied by sixty noble ladies, richly ornamented and dressed". The tournament was proclaimed by heralds in England, Scotland, Hainault, Germany, Flanders, and France, to rival the jousts given by Charles of France

Charles VI of France

Charles VI , called the Beloved and the Mad , was the King of France from 1380 to 1422, as a member of the House of Valois. His bouts with madness, which seem to have begun in 1392, led to quarrels among the French royal family, which were exploited by the neighbouring powers of England and Burgundy...

into Paris a few years earlier, on the entry of his consort Isabeau de Bavière

Isabeau of Bavaria

Isabeau of Bavaria was Queen consort of France as spouse of King Charles VI of France, a member of the Valois Dynasty...

. Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

supervised the preparation of the tournament as clerk of the king.

Tyburn, London

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex close to the current location of Marble Arch in present-day London. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream', a tributary of the River Thames which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the...

, Smithfield was for centuries the main site for the public execution of heretic

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

s and dissident

Dissident

A dissident, broadly defined, is a person who actively challenges an established doctrine, policy, or institution. When dissidents unite for a common cause they often effect a dissident movement....

s in London. The Scottish nobleman William Wallace

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight and landowner who became one of the main leaders during the Wars of Scottish Independence....

was executed here in 1305. The market was used as a meeting place for the peasants in the Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

of 1381 and the revolt's leader, Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler

Walter "Wat" Tyler was a leader of the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381.-Early life:Knowledge of Tyler's early life is very limited, and derives mostly through the records of his enemies. Historians believe he was born in Essex, but are not sure why he crossed the Thames Estuary to Kent...

was killed there after being stabbed by William Walworth

William Walworth

Sir William Walworth , was twice Lord Mayor of London . He is best known for killing Wat Tyler.His family came from Durham...

, the Mayor of London

Mayor of London

The Mayor of London is an elected politician who, along with the London Assembly of 25 members, is accountable for the strategic government of Greater London. Conservative Boris Johnson has held the position since 4 May 2008...

, and a squire on 15 June 1381.

Religious dissenter

Dissenter

The term dissenter , labels one who disagrees in matters of opinion, belief, etc. In the social and religious history of England and Wales, however, it refers particularly to a member of a religious body who has, for one reason or another, separated from the Established Church.Originally, the term...

s (Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

s as well as different Protestant denominations such as Anabaptist

Anabaptist

Anabaptists are Protestant Christians of the Radical Reformation of 16th-century Europe, and their direct descendants, particularly the Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites....

s) were put to death at Smithfield in the course of the changes in the religious orientation of the Crown

Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. The present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, has reigned since 6 February 1952. She and her immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial and representational duties...

, since King Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

. About fifty Protestants and religious reformers

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

, known as the Marian martyrs

Marian Persecutions

The Marian Persecutions were carried out against religious reformers, Protestants, and other dissenters for their heretical beliefs during the reign of Mary I of England. The excesses of this period were mythologized in the historical record of Foxe's Book of Martyrs...

, were executed here during the reign of Mary I

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

. On 17 November 1558, several Protestant heretics were saved from the Smithfield stake moments before the wooden faggots were lit after a royal messenger announced the queen's death. Under English law

English law

English law is the legal system of England and Wales, and is the basis of common law legal systems used in most Commonwealth countries and the United States except Louisiana...

all royal death warrants

Warrant (law)

Most often, the term warrant refers to a specific type of authorization; a writ issued by a competent officer, usually a judge or magistrate, which permits an otherwise illegal act that would violate individual rights and affords the person executing the writ protection from damages if the act is...

were signed under the royal sign-manual

Royal sign-manual

The royal sign manual is the formal name given in the Commonwealth realms to the autograph signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive actfor example, an...

, the personal signature of the monarch, on the recommendation of their governments. But the warrants abated (lost their force) on the sovereign's death if they have not already been executed. Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

did not reinforce the death warrants so all the Protestants were set free. During the 16th century, Smithfield was also used to execute swindlers and coin forgers who were boiled to death in oil

Boiling to death

Death by boiling is a method of execution in which a person is killed by being immersed in a boiling liquid such as water or oil. While not as common as other methods of execution, boiling to death has been used in many parts of Europe and Asia...

. However by the 18th century the "Tyburn Tree" (near the present-day Marble Arch

Marble Arch

Marble Arch is a white Carrara marble monument that now stands on a large traffic island at the junction of Oxford Street, Park Lane, and Edgware Road, almost directly opposite Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park in London, England...

), had become the main place for public executions in London. After 1785, they were again moved, this time to the gates of Newgate prison — just to the south of Smithfield.

In 1666 the Smithfield area was left mostly untouched by the Great Fire of London

Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through the central parts of the English city of London, from Sunday, 2 September to Wednesday, 5 September 1666. The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman City Wall...

, which stopped near the Fortune of War

The Fortune of War Public House

The Fortune of War was an ancient public house in Smithfield, London.It was located on a corner originally known as Pie Corner, today at the junction of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane, the name deriving from the magpie represented on the sign of an adjoining tavern.The Fortune of War on Pie Corner...

tavern, at the junction of Giltspur Street

Giltspur Street

Giltspur Street is a street in Smithfield, London, running north-south from the junction of Newgate Street, Holborn Viaduct, and Old Bailey up to West Smithfield, and it is bounded to the east by St Bartholomew's Hospital...

and Cock Lane, where the statue of the Golden Boy of Pye Corner

Golden Boy of Pye Corner

The Golden Boy of Pye Corner is a small monument located on the corner of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane in Smithfield, London.It was erected where the Great Fire of London stopped and it bears the following inscription:...

is located. In the 17th century, several residents of Smithfield emigrated to the United States where they founded the town of Smithfield, Rhode Island

Smithfield, Rhode Island

Smithfield is a town in Providence County, Rhode Island, United States. It includes the historic villages of Esmond, Georgiaville, Mountaindale, Hanton City, Stillwater and Greenville...

.

Today

Since the late 1990s, Smithfield has seen many new bars, pubs and clubs. Nightclubs such as FabricFabric (club)

Fabric is a nightclub in London, United Kingdom. It was voted number 1 in DJ Magazine's "Top 100 Clubs in the World" poll in 2007 and number 2 in 2008, 2009 and 2010...

and Turnmills

Turnmills

Turnmills was a London nightclub on the corner of Turnmill Street and Clerkenwell Road in the London Borough of Islington. It closed on the morning of 24 March 2008....

were the pioneers of the night life in the area, patronised on weekday nights by the many workers in nearby Holborn

Holborn

Holborn is an area of Central London. Holborn is also the name of the area's principal east-west street, running as High Holborn from St Giles's High Street to Gray's Inn Road and then on to Holborn Viaduct...

, Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell is an area of central London in the London Borough of Islington. From 1900 to 1965 it was part of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. The well after which it was named was rediscovered in 1924. The watchmaking and watch repairing trades were once of great importance...

and the City; at weekends, the night clubs and bars with late licences draw people into the area on their own merit.

At weekends, and from early morning, the business of the market is concluded and the area has become a popular venue as the start for sporting events. Until 2002 Smithfield hosted the midnight start of the annual Miglia Quadrato

Miglia Quadrato

The Miglia Quadrato is an annual car treasure hunt which takes place on the second or third weekend in May within the City of London . It is organised by the United Hospitals and University of London Motoring Club...

car rally, but with the increased night club activity around Smithfield the UHULMC (a motoring club) decided to move the event's start to Finsbury Circus

Finsbury Circus

Finsbury Circus is an elliptical square with its long axis lying east-west in the City of London, England; with an area of 2.2 hectares it is the largest public open space within the City's boundaries. It has an immaculately maintained Lawn Bowls club in the centre, which has existed in the gardens...

. Since 2007, Smithfield has been the location of an annual event dedicated to bike racing known as Smithfield Nocturne.

The market

Origins

Meat has been traded at Smithfield Market for over 800 years, making it one of the oldest markets in London. A livestockLivestock

Livestock refers to one or more domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to produce commodities such as food, fiber and labor. The term "livestock" as used in this article does not include poultry or farmed fish; however the inclusion of these, especially poultry, within the meaning...

market occupied the site as early as the 10th century. In 1174 the site was described by William Fitzstephen

William Fitzstephen

William Fitzstephen , died c. 1191, was a cleric and administrator in the service of Thomas Becket, becoming a Subdeacon in his chapel, with responsibility for perusing letters and petitions. He witnessed Becket's murder, and wrote his biography - the Vita Sancti Thomae William Fitzstephen (also...

as:

a smooth field where every Friday there is a celebrated rendezvous of fine horses to be sold, and in another quarter are placed vendibles of the peasant, swine with their deep flanks, and cows and oxen of immense bulk.

The livestock market expanded over the centuries to meet the demands of the growing population of the City. In 1710, the market was surrounded by a wooden fence to keep the livestock within the market; and until its abolition, the gate house of Cloth Fair was protected by a chain (le cheyne) on market days. Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

referred to the livestock market in 1726 as "without question, the greatest in the world". and the available figures appear to support this claim. Between 1740 and 1750 the average yearly sales at Smithfield were reported to be around 74,000 cattle and 570,000 sheep. By the middle of the 19th century, in the course of a single year 220,000 head of cattle and 1,500,000 sheep would be "violently forced into an area of five acres, in the very heart of London, through its narrowest and most crowded thoroughfares". The volume of cattle driven daily to Smithfield started to raise major concerns.

Growth and decline: End of the cattle market

In the Victorian periodVictorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

, pamphlets started circulating in favour of the removal of the livestock market and its relocation outside of the city, due to its extremely poor hygienic conditions as well as the brutal treatment of the cattle.

The conditions at the market in the first half of the 19th century were often described as a major threat to public health:

Of all the horrid abominations with which London has been cursed, there is not one that can come up to that disgusting place, West Smithfield Market, for cruelty, filth, effluvia, pestilence, impiety, horrid language, danger, disgusting and shuddering sights, and every obnoxious item that can be imagined; and this abomination is suffered to continue year after year, from generation to generation, in the very heart of the most Christian and most polished city in the world.

Our ancestors appear, in sanitary matters, to have been wiser than we are. There exists, amongst the Rolls of Parliament of the year 1380, a petition from the citizens of London, praying- that, for the sake of the public health, meat should not be slaughtered nearer than "Knyghtsbrigg", under penalty, not only of forfeiting such animals as might be killed in the " butcherie," but of a year's imprisonment. The prayer of this petition was granted, audits penalties were enforced during several reigns.

Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood was a British humorist and poet. His son, Tom Hood, became a well known playwright and editor.-Early life:...

wrote in 1830 an Ode to the Advocates for the Removal of Smithfield Market, applauding those "philanthropic men" who aim at removing to a distance the "vile Zoology" of the Market, and "routing that great nest of Hornithology". Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

criticised the location of a livestock market in the heart of the capital in his 1851 essay A Monument of French Folly comparing it to the French market outside Paris at Poissy

Poissy

Poissy is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris from the center.In 1561 it was the site of a fruitless Catholic-Huguenot conference, the Colloquy at Poissy...

:

Of a great Institution like Smithfield, [the French] are unable to form the least conception. A Beast Market in the heart of Paris would be regarded an impossible nuisance. Nor have they any notion of slaughter-houses in the midst of a city. One of these benighted frog-eaters would scarcely understand your meaning, if you told him of the existence of such a British bulwark.

An Act of Parliament

Act of Parliament

An Act of Parliament is a statute enacted as primary legislation by a national or sub-national parliament. In the Republic of Ireland the term Act of the Oireachtas is used, and in the United States the term Act of Congress is used.In Commonwealth countries, the term is used both in a narrow...

was passed in 1852, under the provisions of which a new cattle-market should be constructed in Copenhagen Fields, Islington

Islington

Islington is a neighbourhood in Greater London, England and forms the central district of the London Borough of Islington. It is a district of Inner London, spanning from Islington High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the area around the busy Upper Street...

. The new Metropolitan Cattle Market

Metropolitan Cattle Market

The Metropolitan Cattle Market in Islington, north London was built by the City of London Corporation and opened in June 1855 by Prince Albert...

was opened in 1855, and West Smithfield was left as waste ground for about one decade, until the construction of the new market .

Victorian Smithfield: Meat and poultry market

Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street is a street in Smithfield, on the northern boundary of the City of London, forming the boundary with both the London Borough of Camden and the London Borough of Islington...

was established by an Act of Parliament

Act of Parliament

An Act of Parliament is a statute enacted as primary legislation by a national or sub-national parliament. In the Republic of Ireland the term Act of the Oireachtas is used, and in the United States the term Act of Congress is used.In Commonwealth countries, the term is used both in a narrow...

: the 1860 Metropolitan Meat and Poultry Market Act. It is a large market with permanent buildings, designed by architect

Architect

An architect is a person trained in the planning, design and oversight of the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to offer or render services in connection with the design and construction of a building, or group of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the...

Sir Horace Jones, who was also responsible for Billingsgate

Billingsgate Fish Market

Situated in East London, Billingsgate Fish Market is the United Kingdom's largest inland fish market. It takes its name from Billingsgate, a ward in the south-east of the City of London, where the riverside market was originally established...

and Leadenhall

Leadenhall Market

Leadenhall Market is a covered market in the City of London, located at Gracechurch Street but with vehicular access also available via Whittington Avenue to the north and Lime Street to the south and east and additional pedestrian access via a number of narrow passageways.-History:The market dates...

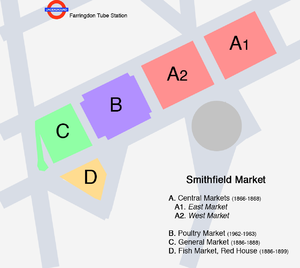

Markets. Work on the Central Market, inspired by Italian architecture, began in 1866 and was completed in November 1868 at a cost of £993,816 (£ as of ). The Grade II listed main wings (known as East and West Market) were separated by the Grand Avenue, a wide roadway roofed by an elliptical arch with decorations in cast iron

Cast iron

Cast iron is derived from pig iron, and while it usually refers to gray iron, it also identifies a large group of ferrous alloys which solidify with a eutectic. The color of a fractured surface can be used to identify an alloy. White cast iron is named after its white surface when fractured, due...

. At the two ends of the arcade, four huge statues represent London, Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

and Dublin and bronze dragons hold the City's coat of arms

Coat of arms

A coat of arms is a unique heraldic design on a shield or escutcheon or on a surcoat or tabard used to cover and protect armour and to identify the wearer. Thus the term is often stated as "coat-armour", because it was anciently displayed on the front of a coat of cloth...

. At the corners of the market four octagonal pavilion towers were built, each with a dome

Dome

A dome is a structural element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory....

and carved stone griffin

Griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle...

s.

As the market was built, a cut and cover railway tunnel was constructed beneath the market to create a triangular junction with the railway between Blackfriars and Kings Cross through the Snow Hill tunnel

Snow Hill tunnel

Snow Hill Tunnel is a railway tunnel on the northern edge of the City of London between City Thameslink and Farringdon stations. The tunnel runs beneath the Smithfield meat market and was constructed using the cut and cover method immediately prior to the building of the market...

— closed in 1916, but now used for Thameslink

Thameslink

Thameslink is a fifty-station main-line route in the British railway system running north to south through London from Bedford to Brighton, serving both London Gatwick Airport and London Luton Airport. It opened as a through service in 1988 and by 1998 was severely overcrowded, carrying more than...

services. This allowed the construction of extensive railway sidings, beneath Smithfield park, and the transfer of animal carcases to the Cold Store building, or direct to the meat market via lifts. These sidings closed in the 1960s, and are now used as a car park, accessed through a cobbled descent in the centre of Smithfield park. Today, much of the meat comes to the market by road.

The first extension of the meat market took place between 1873 and 1876 with the construction of the Poultry Market immediately west of the Central Market. A rotunda

Rotunda (architecture)

A rotunda is any building with a circular ground plan, sometimes covered by a dome. It can also refer to a round room within a building . The Pantheon in Rome is a famous rotunda. A Band Rotunda is a circular bandstand, usually with a dome...

was built at the centre of the old market field, with gardens, a fountain and a ramped carriageway to the station beneath the market building. Further buildings were added to the market in later years. The General Market, built between 1879 and 1883, was intended to replace the old Farringdon Market

Farringdon Market

Farringdon Market was a market erected in 1829 to replace the Fleet Market, which had been cleared for the widening of Farringdon Street and Farringdon Road. The market was between Farringdon Street east and Shoe Lane west, north of Stonecutter Street, in the City of London ward of Farringdon...

located nearby and established for the sale of fruit and vegetables when the earlier Fleet Market

Fleet Market

The Fleet Market was a market erected in 1736 on the newly culverted River Fleet. The market was located approximately where the modern Farringdon Street stands today, to the west of the Smithfield livestock market....

was cleared to enable the laying out of Farringdon Street in 1826–1830.

A further block (also known as Annexe Market or Triangular Block) consisting of two separate structures (the Fish Market and the Red House) was built between 1886 and 1899. The Fish Market was completed in 1888, one year after Horace Jones' death. The Red House, with its imposing red brick and Portland stone

Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries consist of beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building stone throughout the British Isles, notably in major...

façade, was built between 1898 and 1899 for the London Central Markets Cold Storage Co. Ltd.. It was one of the first cold stores to be built outside the London docks and continued to serve Smithfield until the mid-1970s.

20th century

During World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, a large underground cold store at Smithfield was the theatre of secret experiments led by Max Perutz

Max Perutz

Max Ferdinand Perutz, OM, CH, CBE, FRS was an Austrian-born British molecular biologist, who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew, for their studies of the structures of hemoglobin and globular proteins...

on pykrete

Pykrete

Pykrete is a composite material made of approximately 14 percent sawdust or some other form of wood pulp and 86 percent ice by weight. Its use was proposed during World War II by Geoffrey Pyke to the British Royal Navy as a candidate material for making a huge, unsinkable aircraft carrier...

, a mixture of ice and woodpulp, alleged to be tougher than steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

. Perutz's work, inspired by Geoffrey Pyke

Geoffrey Pyke

Geoffrey Nathaniel Joseph Pyke was an English journalist, educationalist, and later an inventor whose clever, but unorthodox, ideas could be difficult to implement...

and part of Project Habakkuk

Project Habakkuk

Project Habakkuk or Habbakuk was a plan by the British in World War II to construct an aircraft carrier out of pykrete , for use against German U-boats in the mid-Atlantic, which were beyond the flight range of land-based planes at that time.The idea came from Geoffrey Pyke who worked for Combined...

, was meant to test the viability of pykrete as a material to construct floating airstrips in the Atlantic to allow refuelling of cargo planes in support of Lord Louis Mountbatten's operations. The experiments were carried out by Perutz and his colleagues in a refrigerated meat locker in a Smithfield Market butcher's basement, behind a protective screen of frozen animal carcasses. These experiments became obsolete with the development of longer range aircraft

Aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air, or, in general, the atmosphere of a planet. An aircraft counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines.Although...

and the project was soon abandoned.

At the end of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, a V2 rocket struck at the north side of Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street is a street in Smithfield, on the northern boundary of the City of London, forming the boundary with both the London Borough of Camden and the London Borough of Islington...

, near the junction with Farringdon Road

Farringdon Road

Farringdon Road is a road in Clerkenwell, Central London. Its construction, which took almost 20 years between the 1840s and the 1860s, is considered one of the greatest urban engineering achievements of the nineteenth century...

(1945). The explosion caused massive damage to the market buildings, extending into the railway tunnel below, and over 110 casualties.

Horace Jones' original Poultry Market was destroyed by fire in 1958. The Grade II listed replacement building was designed by Sir Thomas Bennett

Thomas Bennett (architect)

Sir Thomas Penberthy Bennett KBE FRIBA was a renowned British architect, responsible for much of the development of the new towns of Crawley and Stevenage....

in 1962–1963. The main hall is covered by an enormous concrete dome

Dome

A dome is a structural element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory....

, shaped as an elliptical paraboloid

Paraboloid

In mathematics, a paraboloid is a quadric surface of special kind. There are two kinds of paraboloids: elliptic and hyperbolic. The elliptic paraboloid is shaped like an oval cup and can have a maximum or minimum point....

, spanning 225 feet (68.6 m) by 125 feet (38.1 m) and only 3 inches (7.6 cm) thick at the centre. The dome is believed to be the largest concrete shell

Concrete shell

A concrete shell, also commonly called thin shell concrete structure, is a structure composed of a relatively thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses. The shells are most commonly flat plates and domes, but may also take the form of ellipsoids or cylindrical...

structure ever built in Europe by that time.

Today

Leadenhall Market

Leadenhall Market is a covered market in the City of London, located at Gracechurch Street but with vehicular access also available via Whittington Avenue to the north and Lime Street to the south and east and additional pedestrian access via a number of narrow passageways.-History:The market dates...

and Spitalfields

Spitalfields

Spitalfields is a former parish in the borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London, near to Liverpool Street station and Brick Lane. The area straddles Commercial Street and is home to many markets, including the historic Old Spitalfields Market, founded in the 17th century, Sunday...

) not to have moved out of central London for cheaper land, better transport links and more modern facilities (compare with Covent Garden

New Covent Garden Market

'New Covent Garden Market' is the largest wholesale fruit, vegetable and flower market in the UK. Located in Nine Elms between Vauxhall and Battersea, South West London, the Market covers a site of 57 acres and is home to approximately 200 fruit, vegetable and flower companies.The Market serves...

and Billingsgate

Billingsgate Fish Market

Situated in East London, Billingsgate Fish Market is the United Kingdom's largest inland fish market. It takes its name from Billingsgate, a ward in the south-east of the City of London, where the riverside market was originally established...

). The purpose of the market is to supply inner city butchers, shops and restaurants with meat for the coming day, so the trading hours are from 4:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon every weekday.

Instead of moving away, Smithfield market has been modernised on its existing site: its imposing Victorian buildings have had access points added for the loading and unloading of lorries. The buildings stand on top of a warren of tunnels

Snow Hill tunnel

Snow Hill Tunnel is a railway tunnel on the northern edge of the City of London between City Thameslink and Farringdon stations. The tunnel runs beneath the Smithfield meat market and was constructed using the cut and cover method immediately prior to the building of the market...

: previously, live animals were brought to the market on the hoof (from the mid-19th century onwards they arrived by rail) and were slaughtered on site. The former railway tunnels are now used for storage, parking and as basements. An impressive cobbled ramp spirals down around the public park now known as West Smithfield, on the south side of the market, to give access to part of this area. Some of the buildings on Charterhouse Street on the north side have access into the tunnels from their basements.

Some of the former meat market buildings now have other uses. For example, the former Central Cold Store, in Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street is a street in Smithfield, on the northern boundary of the City of London, forming the boundary with both the London Borough of Camden and the London Borough of Islington...

is now, most unusually, a city centre cogeneration

Cogeneration

Cogeneration is the use of a heat engine or a power station to simultaneously generate both electricity and useful heat....

power station

Power station

A power station is an industrial facility for the generation of electric energy....

operated by Citigen. Another former cold store now houses the night club Fabric

Fabric (club)

Fabric is a nightclub in London, United Kingdom. It was voted number 1 in DJ Magazine's "Top 100 Clubs in the World" poll in 2007 and number 2 in 2008, 2009 and 2010...

.

Part of Smithfield is still open space: a large square with the market on one side and mostly older buildings on the other three. A public park is at the centre. The south side is occupied by St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as Barts, is a hospital in Smithfield in the City of London, England.-Early history:It was founded in 1123 by Raherus or Rahere , a favourite courtier of King Henry I...

(frequently known as Barts), and part of the east side by the church of St Bartholomew the Great. The church of St Bartholomew the Less is just inside the hospital's main gate. The north and south of the square are now closed to through traffic, as a part of the City's security and surveillance

Surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of the behavior, activities, or other changing information, usually of people. It is sometimes done in a surreptitious manner...

cordon known as the Ring of steel. Security for the market is provided by the Market Constabulary

City of London market constabularies

The City of London market constabularies are three small constabularies responsible for security at Billingsgate, New Spitalfields and Smithfield markets run by the City of London Corporation.-See also:*Liverpool Markets Police*Birmingham Market Police...

.

Demolition and development plans

English Heritage

English Heritage . is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport...

and Save Britain's Heritage

SAVE Britain's Heritage

SAVE Britain's Heritage has been described as the most influential conservation group to have been established since William Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877. It was created in 1975 - European Architectural Heritage Year - by a group of journalists,...

among others, are being run to raise public awareness of this important part of London's Victorian heritage. In March 2005, then Culture Secretary

Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport

The Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport is a United Kingdom cabinet position with responsibility for the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. The role was created in 1992 by John Major as Secretary of State for National Heritage...

Tessa Jowell

Tessa Jowell

Tessa Jowell is a British Labour Party politician, who has been the Member of Parliament for Dulwich and West Norwood since 1992. Formerly a member of both the Blair and Brown Cabinets, she is currently the Shadow Minister for the Olympics and Shadow Minister for London.-Early life:Tessa Jane...

announced the decision to give Grade II listed building protection to the Red House Cold Store building, on the basis of new historical evidence qualifying the complex as "the earliest existing example of a purpose-built powered cold store". The future of the adjoining buildings, in particular the General Market, remains unclear. Development plans have been postponed after government planning minister Ruth Kelly

Ruth Kelly

Ruth Maria Kelly is a British Labour Party politician of Irish descent who was the Member of Parliament for Bolton West from 1997 until she stood down in 2010...

decided to call a major public inquiry to be held in 2007. The Public Inquiry for the demolition and redevelopment of the General Market Building took place between 6 November 2007 and 25 January 2008. In August 2008, Communities Secretary

Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government

The Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, is a Cabinet position heading the UK's Department for Communities and Local Government....

Hazel Blears

Hazel Blears

Hazel Anne Blears is a British Labour Party politician, who has been the Member of Parliament for Salford and Eccles since 2010 and was previously the MP for Salford since 1997...

announced that planning permission for the General Market development had been refused, stating that the threatened buildings made "a significant contribution" to the character and appearance of Farringdon and the surrounding area.

Some of the buildings on Lindsey Street opposite the West Market were demolished in 2010 to allow the construction of the new Crossrail

Crossrail

Crossrail is a project to build a major new railway link under central London. The name refers to the first of two routes which are the responsibility of Crossrail Ltd. It is based on an entirely new east-west tunnel with a central section from to Liverpool Street station...

station at Farringdon. The demolished buildings include Smithfield House (an unlisted early 20th century Hennebique concrete

François Hennebique

François Hennebique was a French engineer and self-educated builder who patented his pioneering reinforced-concrete construction system in 1892, integrating separate elements of construction, such as the column and the beam, into a single monolithic element...

building), the Edmund Martin Ltd. shop (an earlier building with alterations dating to the 1930s) and two Victorian warehouses behind them.

External links

- Smithfield Market page on the City of London website

- Victorian London: Smithfield Market: literary quotations about Smithfield.

- St Bartholomew the Great church website.

- 1958 Smithfield Market Fire - London Fire Journal

- Historic picture of Smithfield Market circa 1830 featuring St Bartholomew's HospitalSt Bartholomew's HospitalSt Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as Barts, is a hospital in Smithfield in the City of London, England.-Early history:It was founded in 1123 by Raherus or Rahere , a favourite courtier of King Henry I...

(the centre building in the background) and the shadow of St Paul's CathedralSt Paul's CathedralSt Paul's Cathedral, London, is a Church of England cathedral and seat of the Bishop of London. Its dedication to Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. St Paul's sits at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London, and is the mother...

behind that. - Images of Smithfield Market circa 1991 - black and white images of Smithfield Market before renovations in the mid-1990s.