Stairs Expedition to Katanga

Encyclopedia

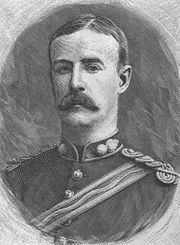

William Grant Stairs

William Grant Stairs was a Canadian-British explorer, soldier, and adventurer who had a leading role in two of the most controversial expeditions in the history of the colonisation of Africa.-Education:...

was the winner in a race between two imperial

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

powers to claim Katanga

Katanga Province

Katanga Province is one of the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Between 1971 and 1997, its official name was Shaba Province. Under the new constitution, the province was to be replaced by four smaller provinces by February 2009; this did not actually take place.Katanga's regional...

, a vast mineral-rich

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

territory in Central Africa

Central Africa

Central Africa is a core region of the African continent which includes Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda....

for civilization, during which a local chief, (Mwenda Msiri) was killed. It is notable for the fact that Stairs, the leader of one side, actually held a commission in the army of the other.

This 'scramble for Katanga' was a prime example of the colonial Scramble for Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

, and one of the most dramatic incidents of that period.

Historical background

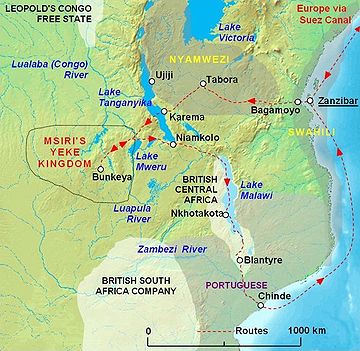

On one side of the race was the Congo Free State (CFS)Congo Free State

The Congo Free State was a large area in Central Africa which was privately controlled by Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Its origins lay in Leopold's attracting scientific, and humanitarian backing for a non-governmental organization, the Association internationale africaine...

, Belgian King Leopold II

Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II was the second king of the Belgians. Born in Brussels the second son of Leopold I and Louise-Marie of Orléans, he succeeded his father to the throne on 17 December 1865 and remained king until his death.Leopold is chiefly remembered as the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free...

's instrument for private colonisation

Colonisation of the Congo

Colonization of the Congo refers to the period from Henry Morton Stanley's first exploration of the Congo until its annexation as a personal possession of King Leopold II of Belgium .-Early European exploration:...

in Central Africa

Central Africa

Central Africa is a core region of the African continent which includes Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda....

. On the other was the company charter

Charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified...

ed by the British government

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

to make treaties

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

with African chiefs, the British South Africa Company (BSAC)

British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company was established by Cecil Rhodes through the amalgamation of the Central Search Association and the Exploring Company Ltd., receiving a royal charter in 1889...

of Cecil Rhodes, who mixed a determined approach to gaining mineral concessions

Mineral exploration

Mineral exploration is the process of finding ore to mine. Mineral exploration is a much more intensive, organized and professional form of mineral prospecting and, though it frequently uses the services of prospecting, the process of mineral exploration on the whole is much more involved.-Stages...

with a vision for British imperial development spanning the continent.

Caught between them, and attempting to play one off against the other, was Msiri, the big chief of Garanganze

Yeke Kingdom

The Yeke Kingdom of the Garanganze people in Katanga, DR Congo was short-lived, existing from about 1856 to 1891 under one king, Msiri, but it became for a while the most powerful state in south-central Africa, controlling a territory of about half a million square kilometres...

or Katanga

Katanga Province

Katanga Province is one of the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Between 1971 and 1997, its official name was Shaba Province. Under the new constitution, the province was to be replaced by four smaller provinces by February 2009; this did not actually take place.Katanga's regional...

, a tribal land not yet claimed by a European power, and larger than many European countries in acreage. Msiri, like many African chiefs, had started as a slave trader, and had used superior weapons obtained by trading ivory, copper and slaves, to conquer and subjugate neighbouring tribes, taking many of them as slaves for resale. By the time of the Stairs Expedition, Msiri was the unchallenged despot of the area. Like the newcomers, he had plenty of cunning and strategic sense, but this time he was the one with the inferior military technology (as well as being totally opposed to the British concept of abolitionism

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

).

The Berlin Conference

At the 1884–5 Berlin ConferenceBerlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence as an imperial power...

and related bilateral

Bilateralism

Bilateralism consists of the political, economic, or cultural relations between two sovereign states. For example, free trade agreements signed by two states are examples of bilateral treaties. It is in contrast to unilateralism or multilateralism, which refers to the conduct of diplomacy by a...

negotiations between Britain and Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, the land west and north of the Luapula River

Luapula River

The Luapula River is a section of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. It is a transnational river forming for nearly all its length part of the border between Zambia and the DR Congo...

−Lake Mweru

Lake Mweru

Lake Mweru is a freshwater lake on the longest arm of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. Located on the border between Zambia and Democratic Republic of the Congo, it makes up 110 km of the total length of the Congo, lying between its Luapula River and Luvua River segments.Mweru...

system (Katanga

Katanga Province

Katanga Province is one of the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Between 1971 and 1997, its official name was Shaba Province. Under the new constitution, the province was to be replaced by four smaller provinces by February 2009; this did not actually take place.Katanga's regional...

) was allocated to the CFS while the land to the east and south was allocated to Britain and the BSAC. However the agreements included a Principle of Effectivity under which each colonial power had to set up an effective presence in the territory—by obtaining treaties from local tribal chiefs, flying their flag, and setting up an administration and police force to keep order—to confirm the claim. If they did not, a rival could come in and do so, thereby 'legally' taking over the territory in the eyes of the civilized powers. In 1890 neither colonial power had treaties or an effective presence in Katanga, and as reports came of gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

and copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

being found in Katanga, the stage was set for a race between the BSAC and CFS.

Treaties obtained from local chiefs in Africa were not aimed at having them accept their subjugation − superior force did that (just as it had for the chiefs themselves, earlier) − but were solely to impress on rival colonial powers that they had the means to convince their own populations of the justice of any military action they might have to take to defend their claim to civilize the area, and that was all that mattered. The idea of democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

was spreading in Europe all throughout the nineteenth century, and, increasingly, governments were required to take account of public opinion. Public opinion in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

could be a powerful motivator of colonial actions, as the Fashoda Incident

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident was the climax of imperial territorial disputes between Britain and France in Eastern Africa. A French expedition to Fashoda on the White Nile sought to gain control of the Nile River and thereby force Britain out of Egypt. The British held firm as Britain and France were on...

a few years later demonstrated.

Previous expeditions

First off the mark was Rhodes who sent Alfred SharpeAlfred Sharpe

Sir Alfred Sharpe was a professional hunter who became a British colonial administrator and Commissioner of the British Central Africa Protectorate from 1896 until 1910...

from Nyasaland

Nyasaland

Nyasaland or the Nyasaland Protectorate, was a British protectorate located in Africa, which was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Since 1964, it has been known as Malawi....

in 1890, backed up by Joseph Thomson

Joseph Thomson (explorer)

Joseph Thomson was a Scottish geologist and explorer who played an important part in the Scramble for Africa. Thomson's Gazelle is named for him. Excelling as an explorer rather than an exact scientist, he avoided confrontations among his porters or with indigenous peoples, neither killing any...

coming from the south, but Sharpe failed to persuade Msiri, and Thomson didn't make it to Msiri's capital at Bunkeya. Sharpe's reports were complacently dismissive about the likelihood of their rivals having any success, and he said that once the 60-year-old Msiri was gone, Katanga would be theirs. In this case it would probably have become part of Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a territory in south central Africa, formed in 1911. It became independent in 1964 as Zambia.It was initially administered under charter by the British South Africa Company and formed by it in 1911 by amalgamating North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia...

, now Zambia

Zambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

, with which it shares strong cultural and ethnic links.

Leopold responded in 1891 by sending two expeditions, and Sharpe's view seemed to be borne out. The Paul Le Marinel expedition only managed to obtain a vaguely worded letter (the Le Marinel letter) from Msiri agreeing to CFS agents having a presence in Katanga, but nothing more. This expedition was hampered by an accident when the gunpowder it was bringing for Msiri blew up, killing several men and damaging some of the other gifts being brought to sweeten the deal. A Belgian officer from the expedition, Legat, stayed behind with a group of askari

Askari

Askari is an Arabic, Bosnian, Urdu, Turkish, Somali, Persian, Amharic and Swahili word meaning "soldier" . It was normally used to describe local troops in East Africa, Northeast Africa, and Central Africa serving in the armies of European colonial powers...

s at a boma

Boma

The port town of Boma in Bas-Congo province was the capital city of the Congo Free State and Belgian Congo from 1 May 1886 to 1926, when it was moved to Léopoldville . It exports tropical timber, bananas, cacao, and palm products...

on the Lufoi River about 40 km from Bunkeya to keep an eye on Msiri. (Msiri later accused Legat of actually having kept the supplies lost in the explosion for himself).

Le Marinel was followed by the Delcommune Expedition, which tried to persuade Msiri on the basis of the Le Marinel letter to accept the CFS flag and Leopold's sovereignty. It also failed, and moved off to the south to explore Katanga's mineral resources.

Preparations and outward journey

|

|

Personnel

Belgium was short of people with tropical experience but Leopold was adept at recruiting other European nationalities for his schemes. Central Africa was a wild frontierFrontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary. 'Frontier' was absorbed into English from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"--the region of a country that fronts on another country .The use of "frontier" to mean "a region at the...

attracting mercenaries for hire. At the recommendation of British-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley, GCB, born John Rowlands , was a Welsh journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of Africa and his search for David Livingstone. Upon finding Livingstone, Stanley allegedly uttered the now-famous greeting, "Dr...

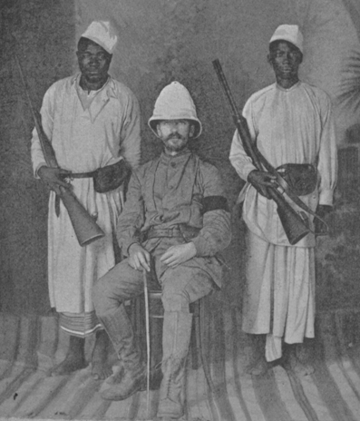

, who had already acted for Leopold in the Congo, the 27 years old Swahili speaking

Swahili language

Swahili or Kiswahili is a Bantu language spoken by various ethnic groups that inhabit several large stretches of the Mozambique Channel coastline from northern Kenya to northern Mozambique, including the Comoro Islands. It is also spoken by ethnic minority groups in Somalia...

Captain William Stairs

William Grant Stairs

William Grant Stairs was a Canadian-British explorer, soldier, and adventurer who had a leading role in two of the most controversial expeditions in the history of the colonisation of Africa.-Education:...

was appointed to lead the expedition, on the basis of his experience on the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition of 1886 to 1889 was one of the last major European expeditions into the interior of Africa in the nineteenth century, ostensibly to the relief of Emin Pasha, General Charles Gordon's besieged governor of Equatoria, threatened by Mahdist forces...

on which he had become Stanley's second in command. He had a reputation of someone who would obey orders and get the job done. That previous expedition had been marked by violence and brutality against any Africans who stood in its way as well as against its own African members. Canadian born

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

at a time when it was part of the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

, Stairs had been educated partly in Britain and had joined a British regiment. He was considered to be and considered himself English or British.

Stairs' second-in-command was the only Belgian on the expedition, Captain Omer Bodson

Omer Bodson

Omer Bodson was the Belgian officer who shot and killed Msiri, King of Garanganze on 20 December 1891 at Bunkeya in what is now DR Congo. Bodson was then killed by one of Msiri's men.-Military career:...

, who had already served the CFS in the Congo, and had had some contact with the Emin Pasha Relief expedition's controversial 'rear column'. Third in command was the Marquis Christian de Bonchamps

Christian de Bonchamps

The Marquis Christian de Bonchamps was a French explorer in Africa and a colonial officer in the French Empire during the late 19th- early 20th century epoch known as the "Scramble for Africa", who played an important role in two of the more notorious incidents of the period.-The Stairs...

, a French adventurer and hunter. There were two other whites: Joseph Moloney

Joseph Moloney

Joseph Moloney was the Irish-born British medical officer on the 1891-92 Stairs Expedition which seized Katanga in Central Africa for the Belgian King Leopold II, killing its ruler, Msiri, in the process...

, the expedition doctor and also something of an adventurer, had previous African experience as a medical officer in the Boer War, and on an expedition in Morocco; and Robinson, the carpenter

Carpenter

A carpenter is a skilled craftsperson who works with timber to construct, install and maintain buildings, furniture, and other objects. The work, known as carpentry, may involve manual labor and work outdoors....

and fixer.

Unlike Sharpe, Stairs was not at all complacent about being in a race, and thought it likely that Joseph Thomson would be sent to negotiate with Msiri for the BSAC before they could get there.

The expedition hired 400 Africans, consisting of four or five Zanzibari 'chiefs' or supervisors including Hamadi bin Malum and Massoudi, about 100 askaris or African soldiers, a number of cooks and personal servants for the whites, and the rest, the majority, were porters or 'pagazis'. Most were from Zanzibar, some were from Mombasa

Mombasa

Mombasa is the second-largest city in Kenya. Lying next to the Indian Ocean, it has a major port and an international airport. The city also serves as the centre of the coastal tourism industry....

, 40 were hired later in Tabora, Msiri's birthplace. At Bunkeya the expedition also had use of eight tough Dahomey

Dahomey

Dahomey was a country in west Africa in what is now the Republic of Benin. The Kingdom of Dahomey was a powerful west African state that was founded in the seventeenth century and survived until 1894. From 1894 until 1960 Dahomey was a part of French West Africa. The independent Republic of Dahomey...

an askari stationed at Legat's boma on the Lufoi who knew Bunkeya well.

The expedition's askaris were armed with 200 'Fusil Gras'

Fusil Gras mle 1874

The Fusil Gras Modèle 1874 M80 was a French rifle of the 19th century. The Gras used by the French Army was an adaptation to metallic cartridge of the Chassepot breech-loading rifle by colonel Basile Gras. This rifle was an 11 mm caliber and used black powder centerfire cartridges that weighed...

rifles (a standard French army weapon of the time) while the officers each had several weapons including Winchester repeating rifles

Winchester rifle

In common usage, Winchester rifle usually means any of the lever-action rifles manufactured by the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, though the company has also manufactured many rifles of other action types...

. Msiri's army had muskets, and needed gunpowder

Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also known since in the late 19th century as black powder, was the first chemical explosive and the only one known until the mid 1800s. It is a mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate - with the sulfur and charcoal acting as fuels, while the saltpeter works as an oxidizer...

.

Orders and objectives

Stairs' orders were to take Katanga with or without Msiri's agreement. If they found a BSAC expedition had beaten them and had a treaty with Msiri they should await further orders. If they obtained a treaty and a BSAC expedition arrived, they should ask it to withdraw and use force to make them comply if necessary. Moloney and Stairs were quite prepared for this eventuality. They were aware that in 1890, Cecil Rhodes had seized ManicalandManicaland

Manicaland is a province of Zimbabwe. It has an area of and a population of approximately 1.6 million . Mutare is the capital of the province. -Background:...

in the face of Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

claims by sending an armed unit under Frederick Selous

Frederick Selous

Frederick Courteney Selous DSO was a British explorer, officer, hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in south and east of Africa. His real-life adventures inspired Sir H. Rider Haggard to create the fictional Allan Quatermain character. Selous was also a good friend of Theodore...

to occupy the territory and force the Portuguese to withdraw.

Having taken Katanga they should then await the arrival of a second CFS column, the Bia Expedition led by two Belgian officers, which was coming down from the Congo River

Congo River

The Congo River is a river in Africa, and is the deepest river in the world, with measured depths in excess of . It is the second largest river in the world by volume of water discharged, though it has only one-fifth the volume of the world's largest river, the Amazon...

in the north to meet them.

Route and journey

The island of Zanzibar was the expedition's base, as it was for most ventures into Central Africa. They left Zanzibar on June 27, 1891. The preferred route was via the ZambeziZambezi

The Zambezi is the fourth-longest river in Africa, and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. The area of its basin is , slightly less than half that of the Nile...

and Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi)

Lake Malawi

Lake Malawi , is an African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the Great Rift Valley system of East Africa. This lake, the third largest in Africa and the eighth largest lake in the world, is located between Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania...

but Harry Johnston

Harry Johnston

Sir Henry "Harry" Hamilton Johnston, GCMG, KCB , was a British explorer, botanist, linguist and colonial administrator, one of the key players in the "Scramble for Africa" that occurred at the end of the 19th century....

, British Commissioner in Nyasaland

British Central Africa

The British Central Africa Protectorate existed in the area of present-day Malawi between 1893 and 1907.-History:The Shire Highlands south of Lake Nyasa and the lands west of the lake had been of interest to the British since they were first explored by David Livingstone in the 1850s, and...

who had acted for Rhodes by sending Sharpe on his failed mission to Msiri, advised that military action he was taking against slave traders made that route unsafe. Instead they crossed German East Africa

German East Africa

German East Africa was a German colony in East Africa, which included what are now :Burundi, :Rwanda and Tanganyika . Its area was , nearly three times the size of Germany today....

from Zanzibar, marching 1050 km during the dry season to Lake Tanganyika through country with potentially hostile tribes and slave traders. They crossed the lake by boat, then marched 550 km to Bunkeya as extreme heat and humidity indicated the build-up to the rainy season which then brought chilling rain, mosquito

Mosquito

Mosquitoes are members of a family of nematocerid flies: the Culicidae . The word Mosquito is from the Spanish and Portuguese for little fly...

es and insanitary conditions.

Averaging 13.3 km per day, it took them 120 days' marching spread over five months (with rest days and delays). The journey included extremes of thick forest, swamps and desolate stony plains. It also included beautiful landscapes, fertile woodland and game-rich grasslands. In one afternoon, Bodson shot a dozen antelope; on another occasion, the men feasted on hippopotamus until they could not move.

The officers had donkey

Donkey

The donkey or ass, Equus africanus asinus, is a domesticated member of the Equidae or horse family. The wild ancestor of the donkey is the African Wild Ass, E...

s to ride on, but these died after crossing Lake Tanganyika. The expedition was not attacked by hostile tribes or raiders as were weaker caravans

Caravan (travellers)

A caravan is a group of people traveling together, often on a trade expedition. Caravans were used mainly in desert areas and throughout the Silk Road, where traveling in groups aided in defence against bandits as well as helped to improve economies of scale in trade.In historical times, caravans...

going to Lake Tanganyika that year.

As they approached Bunkeya, they found the land affected by famine and strife, with a number of burnt and deserted villages. Moloney attributed this to Msiri's tyranny, other accounts suggested that some of the Wasanga chiefs Msiri had forcibly subjugated were taking advantage of the arrival of European powers in the land to rebel against his 30-year rule and, at the age of 60, Msiri was perceived as near the end of his time.

Some accounts say that the Delcommune Expedition, still in the south of Katanga but out of contact with Stairs, was fomenting revolt among Msiri's subject tribes. Bonchamps noted that as Msiri's main army of 5000 warriors had gone south led by one 'Loukoukou' to put down a rebellion by a subject tribe, he was less belligerent, at least on the surface.

On being told by some local people that there were three Europeans in Bunkeya, for a time the expedition thought that Thomson had beaten them. They sent one of their chiefs ahead to ask Msiri for an audience, and he returned with a letter from one of the Europeans, Dan Crawford

Dan Crawford (missionary)

Dan Crawford , also known as 'Konga Vantu', was a Scottish missionary of the Plymouth Brethren in central-southern Africa. He was born in Greenock, son of a Clyde boat captain...

— they were Plymouth Brethren

Plymouth Brethren

The Plymouth Brethren is a conservative, Evangelical Christian movement, whose history can be traced to Dublin, Ireland, in the late 1820s. Although the group is notable for not taking any official "church name" to itself, and not having an official clergy or liturgy, the title "The Brethren," is...

missionaries. Near Bunkeya they were met by Legat, the officer from the Le Marinel expedition with his elite Dahomeyan askari. There was no news of the Bia Expedition.

Msiri

|

|

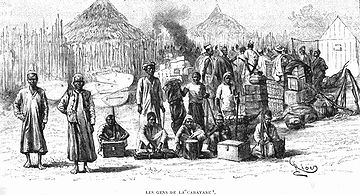

Msiri's capital at Bunkeya consisted of a very large boma

Boma

The port town of Boma in Bas-Congo province was the capital city of the Congo Free State and Belgian Congo from 1 May 1886 to 1926, when it was moved to Léopoldville . It exports tropical timber, bananas, cacao, and palm products...

surrounded by numerous villages spread over an area several kilometres across. The expedition was directed to set up camp within a few hundred metres of the boma. Heads and skulls of Msiri's enemies and victims were mounted on the palisades and on poles at the front. Moloney and Bonchamps referred to these as examples of Msiri's barbarity

Barbarian

Barbarian and savage are terms used to refer to a person who is perceived to be uncivilized. The word is often used either in a general reference to a member of a nation or ethnos, typically a tribal society as seen by an urban civilization either viewed as inferior, or admired as a noble savage...

, and later found it necessary to treat Msiri's own head in the same way, in order to impress his former slaves and warriors.

After the traditional three-day wait before one can see an African big chief, Msiri received them courteously on 17 December 1891. Gifts were presented and negotiations started. Both sides feigned the possibility of future compliance with the other's demands. Msiri wanted gunpowder and removal of Legat, Stairs wanted to fly the CFS flag over Bunkeya. Stairs seemed to think that the Le Marinel letter indicated Msiri's acquiescence, but it was vague, and Msiri repudiated any such interpretation.

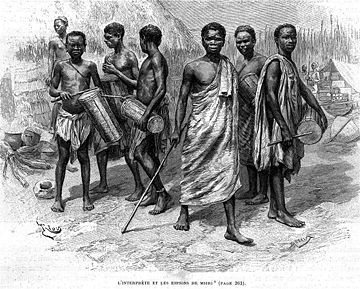

During a stand-off in the negotiations, Msiri used a technique to spy on Stairs' camp which the latter only discovered later, shown in the illustration, Msiri's spies.

Of Msiri's physical presence, Joseph Moloney wrote: "In his prime, Msiri, must have looked the ideal of a warrior-king; he was by no means contemptible in his decline… there was a sphinx-like impenetrability about his expression… his demeanour was thoroughly regal".

On December 19, Stairs realised that Msiri's intention was to delay as long as possible and play the CFS and BSAC off against each other. Concern was growing that Thomson might appear at any time, or that the 5000 warriors would return from the south, so Bonchamps proposed capturing Msiri when he went out at night relatively unguarded to see his favourite wife, Maria de Fonseca

Maria de Fonseca

Maria de Fonseca was the favourite wife of Msiri, the powerful warrior-king of Katanga, at the time when the Stairs Expedition arrived in 1891 to take possession of the territory for the Belgian King Leopold II, with or without Msiri's consent....

, and holding him hostage. Stairs rejected the idea partly because the three British missionaries were not under the expedition's protection at that time, and Stairs felt they were in effect hostages who would be killed in retaliation. He decided instead on an ultimatum

Ultimatum

An ultimatum is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance. An ultimatum is generally the final demand in a series of requests...

: he told Msiri to sign a treaty and hold a ceremony of blood brotherhood with him the next day, and that he would fly the CFS flag without his consent, which he proceeded to do.

Msiri's response was to leave in the night for Munema, a fortified village outside Bunkeya. The next day, December 20, finding him gone, Stairs sent Bodson and Bonchamps with 100 askari to bring Msiri back to him under arrest.

The killing of Msiri

At Munema Bodson and Bonchamps found a large guarded stockade surrounding a hundred huts and a maze of narrow alleys, with Msiri somewhere inside. Despite Bonchamps' protests about the danger, Bodson decided to go inside with just ten askari including a Dahomeyan and Hamadi-bin-Malum to find Msiri, while Bonchamps and the remaining askari waited outside. Bodson would fire his revolver if he needed assistance.Bodson found Msiri sitting in front of a large hut with 300 men in the background, many armed with muskets. Bodson told Msiri he had come to take him to Stairs, and Msiri did not reply but became angry, rose and put his hand on his sword

Sword

A sword is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. The precise definition of the term varies with the historical epoch or the geographical region under consideration...

(a gift brought by Stairs). Bodson drew his revolver

Revolver

A revolver is a repeating firearm that has a cylinder containing multiple chambers and at least one barrel for firing. The first revolver ever made was built by Elisha Collier in 1818. The percussion cap revolver was invented by Samuel Colt in 1836. This weapon became known as the Colt Paterson...

and shot Msiri three times, and one of Msiri's men — his son Masuka — fired his musket hitting Bodson in the abdomen and spinal column. The Dahomeyan askari shot and killed Masuka, and in the general firing Hamadi was hit in the ankle.

Bonchamps and the remaining askari ran to the sound, and chaos took over. Most of Msiri's men fled, the askaris shot at anything, and then started looting. It took nearly an hour for Moloney to arrive with reinforcements. He and Bonchamps restored order among the askaris and, under sporadic fire from Msiri's men under the command of his adopted son Mukanda-Bantu and brothers, Chukako and Lukuku, retreated with Bodson and the other wounded, and Msiri's body, to prevent his men pretending to the populace that he was still alive. They took up a defensive position on a hill near their camp where Stairs had been waiting.

This account of the killing was attributed by Moloney to a verbal report by Hamadi, while Bonchamps wrote that the injured Bodson gave him the same account before he died in the night. Stairs wrote a letter to Arnot with the same details of the attempted arrest at Munema, but also said that Msiri's men had 'cocked their guns' when Bodson confronted Msiri.

A barbaric act

On the hill to which they retreated, according to Bonchamps but not mentioned by Moloney, the expedition cut off Msiri's head and hoisted it on a palisade in plain view, to show the people their king was dead. Bonchamps, who had written about the disgust of seeing how Msiri had put heads of his enemies on poles outside his boma, admitted this was barbaric, but claimed it was a necessary lesson aimed at those who had attacked the expedition 'without provocation'.Munema was littered with bodies and the expedition's askaris carried out a general massacre. Dan Crawford wrote: "The population completely dispersed. No one dared walk openly abroad. The paths became lined with corpses, some of whom had died of starvation and some of the universal mistrust which keeps spears on the quiver".

Aftermath

The expedition quickly strengthened their defences but were not attacked in retaliation. Msiri's brothers and Mukanda-Bantu sent messages the next day asking for the body to bury, and Stairs agreed to release it. Msiri's head is not mentioned again by Bonchamps, Garanganze sources say they buried a body without a head. After the burial, negotiations re-opened and included Maria de FonsecaMaria de Fonseca

Maria de Fonseca was the favourite wife of Msiri, the powerful warrior-king of Katanga, at the time when the Stairs Expedition arrived in 1891 to take possession of the territory for the Belgian King Leopold II, with or without Msiri's consent....

(later executed by Mukanda-Bantu in horrible fashion for 'betrayal') and her brother, Msiri's Portuguese-Angolan trading partner, Coimbra.

The expedition's weaponry and askaris had proved their superiority over muskets and Msiri's people were more interested in the succession than revenge. Stairs backed Mukanda-Bantu to succeed Msiri, but as chief of a reduced territory, and he restored the Wasanga chiefs overthrown by Msiri 30 years before. Mukanda-Bantu signed the treaties, and the restored Wasanga chiefs were very happy to do so too. Msiri's brothers were unhappy with the sub-chieftainships they were given and refused to sign up, until threatened with the same fate as Msiri. By early January 1892 the expedition had the papers sufficient to convince their British rivals that they now had Katanga.

During that January though, the food ran out and none was left in the district — already affected by famine, the population took what little there was with them when they fled. The rainy season brought malaria and dysentery, all four surviving officers fell sick, and floods cut Bunkeya off from the game-rich plains to the north where they might have hunted. Moloney recovered first and took charge of the expedition's task of building a more permanent fort and trying to find food. 76 of the expedition's askaris and porters died that month of dysentery and starvation. Stairs had severe fevers, and in his delirium he imagined Thomson had arrived, and yelled for his revolver with which to repel the BSAC man; Moloney had wisely taken it from him.

At the end of the January the new season's crop of maize

Maize

Maize known in many English-speaking countries as corn or mielie/mealie, is a grain domesticated by indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica in prehistoric times. The leafy stalk produces ears which contain seeds called kernels. Though technically a grain, maize kernels are used in cooking as a vegetable...

was ready for harvest, and this saved the expedition. Then the delayed Bia Expedition of about 350 men arrived from the CFS in the north.

Return journey

As Captain Stairs, the Marquis Bonchamps and Robinson were still incapacitated, it was agreed that Captain Bia would take over the consolidation of Congo Free State control of Katanga, and the Stairs expedition would return by the originally-planned route via Lake Nyasa and the Zambezi.As they left carrying the sick officers in hammocks they experienced some harassment and raids by natives ruled by Lukuku, and the march was exceptionally hard owing to the heavy rains at the end of the wet season (as well as to the continuing illness and weakness of expedition members). Bonchamps had recovered by the time they reached Lake Tanganyika and was put in charge by Stairs, who had not fully recovered. This caused some friction between Bonchamps and Moloney, and there are some contradictions between their accounts.

From the north end of Lake Nyasa onwards the route was by steamer

Steamboat

A steamboat or steamship, sometimes called a steamer, is a ship in which the primary method of propulsion is steam power, typically driving propellers or paddlewheels...

, except for a march of about 150 km around the rapids on the Shire River

Shire River

The Shire is a river in Malawi and Mozambique. The river has been known as the Shiré or Chire River. It is the outlet of Lake Malawi and flows into the Zambezi. Its length is 402 km; including Lake Malawi and the Ruhuhu, its headstream, it has a length of about 1200 km...

. Here the route took them past Zomba and Blantyre

Blantyre, Malawi

Blantyre or Mandala is Malawi's centre of finance and commerce, the largest city with an estimated 732,518 inhabitants . It is sometimes referred to as the commercial capital of Malawi as opposed to the political capital, Lilongwe...

, headquarters of the British Commissioner for Central Africa, none other than Alfred Sharpe, the BSAC agent whom they had beaten in the race. They met but the conversation has not been recorded.

On a second steamer down the Zambezi, Stairs, who seemed to have recovered, suddenly took sick again and died on June 3, 1892 of haematuric fever, a severe form of malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

, before they reached Chinde

Chinde

Chinde is a town of Mozambique, and a port for the Zambezi valley. It is located on the Chinde River, and is an important fishing center. It exports copra and sugar, and had a population of 16,500 in 1980...

, a river transport base, where he was buried in the European cemetery.

The expedition reached Zanzibar a year after their departure. Of 400 Africans on the expedition to leave Tabora, only 189 reached Zanzibar, most of the other 211 had died, a few had absconded. Bonchamps, Moloney and Robinson reached Europe barely two weeks after sailing from Zanzibar, and just over 14 months after having left Paris and London on the expedition.

Consequences

On his return to London, Moloney learned that Thomson had not tried to reach Katanga again. The British Government had quietly ordered him not to go.The expedition had only survived through the strength and endurance of the Zanzibari porters and askaris, as well as the tendency of a loyal core of them, epitomised by Hamadi bin Malum, to come to the rescue when mutiny, treachery, robbery or some other disaster threatened.

Leopold and the Belgian Congo

The expedition was regarded by the Belgians as a complete success. Leopold used his influence and that of the British directors he had appointed to his companies to gain acceptance of the treaties signed to place Katanga securely in Leopold's realm, adding about half a million square kilometres to it (16 times the area of Belgium). Keeping it separate from the CFS, Leopold delegated the administration of Katanga to another of his companies, which set up on the northern and western shores of Lake Mweru. This meant it was not associated with the Red Rubber problems of CFS rule in the rest of the Congo. The Katanga company's main achievement was helping to stamp out the slave trade, but it did little in the rest of the territory until after 1900. Katanga remained affected by instability and conflict, as various chieftainships struggled to fill the vacuum left by Msiri's death.Katanga and the Congo were both taken over by the Belgian government in 1908 in response to the international outcry over the brutality of Leopold's CFS, and were merged in 1910 as the Belgian Congo

Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo was the formal title of present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo between King Leopold II's formal relinquishment of his personal control over the state to Belgium on 15 November 1908, and Congolese independence on 30 June 1960.-Congo Free State, 1884–1908:Until the latter...

, but the legacy of the previous separation was a tendency of Katanga to secede

Secession

Secession is the act of withdrawing from an organization, union, or especially a political entity. Threats of secession also can be a strategy for achieving more limited goals.-Secession theory:...

.

The Belgian Congo administration with its policy of direct rule

Direct Rule

Direct rule was the term given, during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, to the administration of Northern Ireland directly from Westminster, seat of United Kingdom government...

did nothing to prepare the country for independence in 1960 and within a few years Congo and Katanga became such bywords for strife and chaos that the Mobutu regime, in a futile effort to improve its image, changed the names to Zaire and Shaba respectively (since reverted).

Rhodes and the BSAC

Cecil Rhodes got over any disappointment at losing the scramble for Katanga by doing what he did best − he invested in mineral prospectingMineral exploration

Mineral exploration is the process of finding ore to mine. Mineral exploration is a much more intensive, organized and professional form of mineral prospecting and, though it frequently uses the services of prospecting, the process of mineral exploration on the whole is much more involved.-Stages...

and mining

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

in Katanga. When the British in the Rhodesian territories realised in the 1920s the extent of Katanga's mineral wealth, which was more than the equal of Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a territory in south central Africa, formed in 1911. It became independent in 1964 as Zambia.It was initially administered under charter by the British South Africa Company and formed by it in 1911 by amalgamating North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia...

's own Copperbelt, the most polite epithet

Epithet

An epithet or byname is a descriptive term accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, divinities, objects, and binomial nomenclature. It is also a descriptive title...

for Captain Stairs was 'mercenary', and some regarded him as a traitor to the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

.

The Garanganze people

The population in and around Bunkeya numbered 60−80 000 but most dispersed in the disorder. The Belgians forcibly moved Mukanda-Bantu and about 10,000 of his people to the Lufoi River where they continued the chieftainship under the title 'Mwami Mwenda' in honour of Msiri. They eventually returned to Bunkeya where today Mwami Mwenda VIII is the reigning chief of about 20,000 Yeke/Garanganze peopleGaranganze people

The Garanganze or Yeke people of Katanga in DR Congo established the Yeke Kingdom under the warrior-king Msiri who dominated the southern part of Central Africa from 1850 to 1891 and controlled the trade route between Angola and Zanzibar from his capital at Bunkeya.Msiri and his people were...

.

Dan Crawford moved to the Luapula-Lake Mweru valley and set up two missions to which many Garanganze people gravitated.

The DR Congo-Zambia border

The Stairs Expedition confirmed that the border between Belgian and British colonies would lie along the Zambezi-Congo watershed, the Luapula RiverLuapula River

The Luapula River is a section of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. It is a transnational river forming for nearly all its length part of the border between Zambia and the DR Congo...

, Lake Mweru and an arbitrary line drawn between Mweru and Lake Tanganyika. This divided culturally and ethnically similar people such as the Kazembe-Lunda and created the Congo Pedicle

Congo Pedicle

The Congo Pedicle refers to the southeast salient of the Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo which sticks into neighbouring Zambia almost dividing it into two lobes, like the wings of a butterfly. In area the pedicle is similar in size to Wales or New Jersey...

, an example of the arbitrary nature of colonial borders.

Msiri's head: a curse and a mystery

In the traditional belief systems of the Garanganze people, as with other Central and Southern African cultures, illness and disease are not caused by pathogens but by magic and supernatural forces. The sickness suffered by Stairs and the expedition members was attributed by them to Msiri's spirit and his people taking revenge, and a rumour took hold that Stairs had kept Msiri's head and it cursed and killed all who carried it. The Mwami Mwenda chieftainships' history says that the expedition fled with Msiri's head intending to present it to Leopold, but 'Mukanda-Bantu and his men' caught and 'killed all the Belgians' and the head was buried 'under a hill of stones' in what is now ZambiaZambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

.

Another account says that when Stairs died he had with him Msiri's head in a can of kerosene, but there is no mention of it in Moloney's or Bonchamps' journals. The whereabouts of Msiri's skull remains a mystery today.

See also

- Msiri

- History of KatangaHistory of KatangaThis is a history of Katanga Province and the former independent State of Katanga, as well as the history of the region prior to colonization.-Earliest residents:...

- Garanganze peopleGaranganze peopleThe Garanganze or Yeke people of Katanga in DR Congo established the Yeke Kingdom under the warrior-king Msiri who dominated the southern part of Central Africa from 1850 to 1891 and controlled the trade route between Angola and Zanzibar from his capital at Bunkeya.Msiri and his people were...

- Yeke KingdomYeke KingdomThe Yeke Kingdom of the Garanganze people in Katanga, DR Congo was short-lived, existing from about 1856 to 1891 under one king, Msiri, but it became for a while the most powerful state in south-central Africa, controlling a territory of about half a million square kilometres...

- Maria de FonsecaMaria de FonsecaMaria de Fonseca was the favourite wife of Msiri, the powerful warrior-king of Katanga, at the time when the Stairs Expedition arrived in 1891 to take possession of the territory for the Belgian King Leopold II, with or without Msiri's consent....

- William Grant StairsWilliam Grant StairsWilliam Grant Stairs was a Canadian-British explorer, soldier, and adventurer who had a leading role in two of the most controversial expeditions in the history of the colonisation of Africa.-Education:...

- Omer BodsonOmer BodsonOmer Bodson was the Belgian officer who shot and killed Msiri, King of Garanganze on 20 December 1891 at Bunkeya in what is now DR Congo. Bodson was then killed by one of Msiri's men.-Military career:...

- Christian de BonchampsChristian de BonchampsThe Marquis Christian de Bonchamps was a French explorer in Africa and a colonial officer in the French Empire during the late 19th- early 20th century epoch known as the "Scramble for Africa", who played an important role in two of the more notorious incidents of the period.-The Stairs...

- Joseph MoloneyJoseph MoloneyJoseph Moloney was the Irish-born British medical officer on the 1891-92 Stairs Expedition which seized Katanga in Central Africa for the Belgian King Leopold II, killing its ruler, Msiri, in the process...

- Emin Pasha Relief ExpeditionEmin Pasha Relief ExpeditionThe Emin Pasha Relief Expedition of 1886 to 1889 was one of the last major European expeditions into the interior of Africa in the nineteenth century, ostensibly to the relief of Emin Pasha, General Charles Gordon's besieged governor of Equatoria, threatened by Mahdist forces...