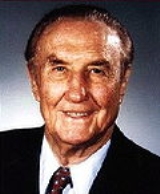

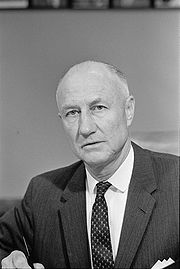

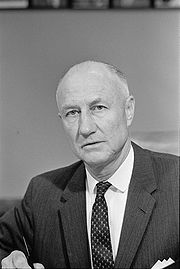

Strom Thurmond

Encyclopedia

James Strom Thurmond was an American politician who served as a United States Senator

. He also ran for the Presidency of the United States

in 1948

as the segregationist States Rights Democratic Party

(Dixiecrat) candidate, receiving 2.4% of the popular vote and 39 electoral votes. Thurmond later represented South Carolina in the United States Senate

from 1954 until 2003, at first as a Democrat

and after 1964 as a Republican

. He switched out of support for the conservatism of Republican presidential candidate and Arizona

Senator Barry Goldwater

, who shared his opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act

. He left office as the only senator to reach the age of 100 while still in office and as the oldest-serving and longest-serving senator in U.S. history (although he was later surpassed in the latter by Robert Byrd

). Thurmond holds the record for the longest-serving Dean of the United States Senate

in U.S. history at 14 years.

He conducted the longest filibuster

ever by a lone senator, in opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957

, at 24 hours and 18 minutes in length, nonstop. In the 1960s, he continued to fight against civil rights legislation. He always insisted he had never been a racist, but was merely opposed to excessive federal authority. However, he infamously said that "all the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement", while attributing the movement for integration to Communism. Starting in the 1970s, he moderated his position on race, but continued to defend his early segregation

ist campaigns on the basis of states' rights

in the context of Southern society at the time, never fully renouncing his earlier viewpoints.

Six months after Thurmond's death in 2003, it was revealed that at age 22 he had fathered a daughter, Essie Mae Washington-Williams

, with his family's African-American maid Carrie Butler, then 16. Although Thurmond never publicly acknowledged his daughter, he paid for her college education and passed other money to her for some time. The Thurmond family acknowledged her.

, the son of John William Thurmond (May 1, 1862 – June 17, 1934) and Eleanor Gertrude Strom (July 18, 1870 – January 10, 1958). He attended Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina (now Clemson University

), where he was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity. Thurmond graduated in 1923 with a degree in horticulture

.

After Thurmond's death in 2003, an attorney for his family confirmed that in 1925, when he was 22, Thurmond fathered a mixed-race daughter, Essie Mae Washington-Williams

, with his family's housekeeper, Cassie Butler, then 16 years old. Thurmond paid for the girl's college education and provided other support.

He was a farmer, teacher and athletic coach until 1929, when he was appointed Edgefield County's superintendent of education, serving until 1933. Thurmond studied law with his father and was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1930. He served as the Edgefield Town and County attorney from 1930 to 1938. In 1933 Thurmond was elected to the South Carolina Senate

and represented Edgefield until he was elected to the Eleventh Circuit judgeship.

, Judge Thurmond resigned from the bench to serve in the U.S. Army, rising to Lieutenant Colonel

. In the Battle of Normandy (June 6 – August 25, 1944), he landed in a glider attached to the 82nd Airborne Division. For his military service, he received 18 decorations

, medal

s and awards, including the Legion of Merit

with Oak Leaf Cluster

, Bronze Star

with Valor device

, Purple Heart

, World War II Victory Medal

, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

, Belgium

's Order of the Crown

and France's Croix de Guerre

.

During 1954–55 he was president of the Reserve Officers Association

. He retired from the U.S. Army Reserves with the rank of Major General

.

in 1946, largely on the promise of making state government more transparent and accountable by weakening the power of a group of politicians from Barnwell

, which Thurmond dubbed the Barnwell Ring

led by House Speaker Solomon Blatt

. Thurmond was considered a progressive for much of his term, in large part due to his influence in arresting all those responsible for the lynch mob murder

of Willie Earle. Though none of the men were found guilty by the jury, Thurmond was congratulated by the NAACP

and the ACLU

for his efforts.

desegregated the U.S. Army, proposed the creation of a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission

, supported the elimination of state poll taxes, and supported drafting federal anti-lynching

laws. Thurmond became a candidate for President of the United States

on the third party

ticket of the States' Rights Democratic Party

. It split from the national Democrats over what was perceived as federal intervention in the segregation practices of the Southern states, which, among other issues, had largely disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites by constitutional amendments and electoral requirements from 1890 to 1910. Thurmond carried four states and received 39 electoral votes. One 1948 speech, met with cheers by supporters, included the following:

In 1952, Thurmond endorsed Republican Dwight Eisenhower

for the Presidency, rather than the Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson. This led state Democratic Party leaders to block Thurmond from receiving the nomination to the Senate in 1954, forcing him to run as a write-in candidate.

was unopposed for re-election in 1954, but died in September of that year. Democratic leaders hurriedly appointed state Senator

Edgar A. Brown, a member of the Barnwell Ring, as the party's nominee to replace Maybank. Widespread criticism of the party's failure to elect the nominee in a primary led to Thurmond announcing that he would mount a write-in campaign

. He campaigned, at the recommendation of Governor James Byrnes

, on a pledge that he would resign in 1956 to trigger a contested primary. Thurmond won overwhelmingly, becoming the first person to be elected to the U.S. Senate as a write-in candidate

against ballot-listed opponents. Following through on his campaign promise, he resigned in 1956 and then won the Democratic primary—in those days, the real contest in South Carolina—for the special election triggered by his own vacancy. His career in the Senate remained uninterrupted until his retirement 46 years later, despite his mid-career party switch.

Thurmond vehemently supported racial segregation with the longest filibuster ever conducted by a single senator, speaking for a total of 24 hours and 18 minutes in an unsuccessful attempt to derail the Civil Rights Act of 1957

. Cots were brought in from a nearby hotel for the legislators to sleep on while Thurmond discussed increasingly irrelevant and obscure topics, including his grandmother's biscuit recipe. Other Southern senators, who had agreed as part of a compromise not to filibuster this bill, were upset with Thurmond because they thought his defiance made them look incompetent to their constituents.

According to journalist Jeff Sharlet

, he was a member of the Family (also known as the Fellowship), described by prominent evangelical Christians as one of the most politically well connected Christian organizations in the U.S.

Throughout the 1960s, Thurmond generally received relatively low marks from the press and his fellow senators in the performance of his Senate duties, as he often missed votes and rarely proposed or sponsored noteworthy legislation.

Throughout the 1960s, Thurmond generally received relatively low marks from the press and his fellow senators in the performance of his Senate duties, as he often missed votes and rarely proposed or sponsored noteworthy legislation.

Thurmond was increasingly at odds with the Democratic Party. On September 16, 1964, he switched his party affiliation

to Republican. He played an important role in South Carolina's support for Republican presidential

candidates Barry Goldwater

in 1964

and Richard Nixon

in 1968

. South Carolina and other states of the Deep South

had supported the Democrats in every national election from the end of Reconstruction, when white Democrats re-established political control in the South, to 1960. However, discontent with the Democrats' increasing support for civil rights

resulted in John F. Kennedy

's barely winning the state in 1960

. After Kennedy's assassination

, President Lyndon Johnson's strong support for the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 and integration angered white segregationists even more. Goldwater won South Carolina by a large margin in 1964.

In 1968, Richard Nixon ran the first GOP "Southern strategy

" campaign appealing to disaffected southern white voters. Although segregationist Democrat George Wallace

was on the ballot, Nixon ran slightly ahead of him and gained South Carolina's electoral

votes. Due to the antagonism of white South Carolina voters toward the national Democratic Party, Hubert Humphrey

received less than 30% of the total vote, carrying only majority-black districts.

At the 1968 Republican National Convention

in Miami Beach, Thurmond played a key role in keeping Southern delegates committed to Nixon, despite the sudden last-minute entry of California

Governor Ronald Reagan

into the race. Thurmond also quieted conservative fears over rumors that Nixon planned to ask either Charles Percy

or Mark Hatfield

—liberal Republicans—to be his running mate, by making it known to Nixon that both men were unacceptable for the vice-presidency to the South. Nixon ultimately asked Maryland

Governor Spiro Agnew

—an acceptable choice to Thurmond—to join the ticket.

At this time, too, Thurmond took the lead in thwarting Johnson's attempt to elevate Justice Abe Fortas

to the post of Chief Justice

of the United States. Thurmond's conservatism left him unhappy with the Warren Court

. He was glad to simultaneously to disappoint Johnson and to leave the task of replacing Warren to Johnson's presidential successor Richard Nixon.

Thurmond decried the Supreme Court opinion in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, which ordered the immediate desegregation of schools in the American South. Thurmond praised President Nixon and his "Southern Strategy" of delaying desegregation, saying Nixon "stood with the South in this case".

On February 4, 1972, Thurmond sent a secret memo to William Timmons

(in his capacity as an aide to Richard Nixon) and United States Attorney General

John N. Mitchell

, with an attached file from the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee urging that British musician John Lennon (living in New York City

at the time) be deported from the United States as an undesirable alien, due to Lennon's political views and activism. The document claimed that Lennon's influence on young people could affect Nixon's chances of re-election, and suggested that terminating Lennon's visa might be "a strategy counter-measure". Thurmond's memo and attachment, received by the White House on February 7, 1972, initiated the Nixon administration's persecution of John Lennon that threatened the former Beatle with deportation for nearly five years from 1972 to 1976. The documents were discovered in the FBI files after a Freedom of Information Act search by Professor Jon Wiener

, published in Weiner's book Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files (2000), and are discussed in the documentary

film The U.S. vs. John Lennon (2006).

In 1976

, he appeared in a campaign commercial for incumbent President Gerald Ford

in his race against Thurmond's fellow Southerner

, former Georgia

governor Jimmy Carter

. In the commercial, Thurmond declared that Ford (who was born in Nebraska

and spent most of life in Michigan

) "sound[ed] more like a Southerner

than Jimmy Carter

".

was passed, African Americans were protected in exercising their constitutional rights as citizens to vote, and were generally able to register and vote without harassment. Their large numbers, combined with those of whites who supported civil rights, could no longer be ignored by state politicians.

Thurmond appointed African American Thomas Moss to his staff in 1971, described as the first appointment by a member of the South Carolinian congressional delegation (also incorrectly reported by many sources as the first senatorial appointment of an African American, but Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison

had hired clerk-librarian Jesse Nichols in 1937). In 1983, he voted to make the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.

a federal holiday. In South Carolina, the honor was diluted, as until 2000 the state offered employees the option to celebrate this holiday or substitute one of three Confederate holidays instead. Despite his actions, Thurmond never explicitly renounced his earlier views on racial segregation.

Thurmond became President pro tempore of the US Senate

Thurmond became President pro tempore of the US Senate

in 1981, and held the largely ceremonial post for three terms, alternating with his longtime rival Robert Byrd

depending on the party composition of the Senate. During this period, he maintained a close relationship with the Reagan White House.

Thurmond served as the ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee during the Clarence Thomas hearings in 1991 and worked closely with Joe Biden

, then the chairman. He also joined the minority of Republicans who voted for the Brady Bill

in 1993.

On December 5, 1996, Thurmond became the oldest serving member of the U.S. Senate, and on May 25, 1997, the longest-serving member (41 years and 10 months). He cast his 15,000th vote in September 1998.

Towards the end of Thurmond's Senate career, there was controversy over his mental condition. His supporters argued that while he lacked physical stamina due to his age, mentally he remained aware and attentive and maintained a very active work schedule in showing up for every floor vote. He stepped down as Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee at the beginning of 1999, as he had pledged to do in late 1997.

Towards the end of Thurmond's Senate career, there was controversy over his mental condition. His supporters argued that while he lacked physical stamina due to his age, mentally he remained aware and attentive and maintained a very active work schedule in showing up for every floor vote. He stepped down as Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee at the beginning of 1999, as he had pledged to do in late 1997.

Declining to seek re-election in 2002, he was succeeded by fellow Republican Lindsey Graham

.

Thurmond left the Senate in January 2003 as the United States' longest-serving senator (a record later surpassed by Senator Byrd). In his November farewell speech in the Senate, Thurmond told all his colleagues "I love all of you, especially your wives," the latter being a reference to his flirtatious nature with younger women.

At his 100th birthday and retirement celebration in December, Thurmond stated "I don't know how to thank you. You're wonderful people, I appreciate you, appreciate what you've done for me, and may God allow you to live a long time.

Thurmond's 100th birthday celebration, however, became controversial after Mississippi Senator Trent Lott

made comments that were viewed as racially insensitive: "When Strom Thurmond ran for president, [Mississippi] voted for him. We're proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn't have had all these problems over the years, either." These comments led to Lott's ouster as Senate Majority Leader.

13 years later; there were no children.

He married his second wife, Nancy Janice Moore (born 1946), Miss South Carolina

of 1965, on December 22, 1968. He was 66 years old and she was only 22. She had been working in his Senate office off and on since 1967. It is often said that he ran for president before she was born. This is false; however, he was old enough to be eligible. They separated in 1991, but never divorced. The two remained married and close friends until his death. He even considered resigning during his last term, but only if the Governor would appoint his wife to the seat as his replacement.

At age 68 (with his wife Nancy at age 25) Thurmond fathered what was then believed to be his first child. His four children with Nancy are: beauty pageant contestant Nancy Moore Thurmond (1971–1993), who was killed when a drunk driver hit her in Columbia, South Carolina

; former U.S. Attorney for the District of South Carolina and current South Carolina 2nd Judicial Circuit Solicitor James Strom Thurmond Jr. (born 1972); Washington, D.C.

, homemaker Juliana Gertrude Thurmond Whitmer (born 1973); and Charleston County, South Carolina

, Council Member Paul Reynolds Thurmond (born 1976).

delivered a eulogy, and later to the family burial plot in Willowbrook Cemetery in Edgefield where he was interred.

, an African-American woman of bright complexion, publicly revealed that she was Strom Thurmond's daughter. She was born to Carrie "Tunch" Butler (1909–1948), a maid who had worked for Thurmond's parents, on October 12, 1925, when Butler was sixteen years old and Thurmond twenty-two. He helped pay his daughter's way through college. Though Thurmond never publicly acknowledged Washington-Williams while he was alive, he continued to support her financially. These payments extended well into her adult life. Washington-Williams has stated that she did not reveal she was Thurmond's daughter during his lifetime because it "wasn't to the advantage of either one of us". She kept silent out of love and respect for her father and denies that there was an agreement between the two not to reveal her connection to Thurmond.

After Washington-Williams came forward, the Thurmond family publicly acknowledged her parentage. Many close friends, staff members, and South Carolina residents had long suspected Washington-Williams was his daughter, saying that Thurmond had always taken a great deal of interest in her. The young mixed-race woman had been granted a degree of access to Thurmond more appropriate to a family member than to a member of the public. Washington-Williams is eligible for membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution

and the United Daughters of the Confederacy

through her Thurmond ancestry. Thurmond was a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans

, a similar group for men.

|-

|-

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. He also ran for the Presidency of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

in 1948

United States presidential election, 1948

The United States presidential election of 1948 is considered by most historians as the greatest election upset in American history. Virtually every prediction indicated that incumbent President Harry S. Truman would be defeated by Republican Thomas E. Dewey. Truman won, overcoming a three-way...

as the segregationist States Rights Democratic Party

Dixiecrat

The States' Rights Democratic Party was a short-lived segregationist political party in the United States in 1948...

(Dixiecrat) candidate, receiving 2.4% of the popular vote and 39 electoral votes. Thurmond later represented South Carolina in the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from 1954 until 2003, at first as a Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

and after 1964 as a Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

. He switched out of support for the conservatism of Republican presidential candidate and Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

Senator Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater was a five-term United States Senator from Arizona and the Republican Party's nominee for President in the 1964 election. An articulate and charismatic figure during the first half of the 1960s, he was known as "Mr...

, who shared his opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States that outlawed major forms of discrimination against African Americans and women, including racial segregation...

. He left office as the only senator to reach the age of 100 while still in office and as the oldest-serving and longest-serving senator in U.S. history (although he was later surpassed in the latter by Robert Byrd

Robert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd was a United States Senator from West Virginia. A member of the Democratic Party, Byrd served as a U.S. Representative from 1953 until 1959 and as a U.S. Senator from 1959 to 2010...

). Thurmond holds the record for the longest-serving Dean of the United States Senate

Dean of the United States Senate

The Dean of the United States Senate is an informal term used to refer to the Senator with the longest continuous service. The current Dean is Daniel Inouye of Hawaii...

in U.S. history at 14 years.

He conducted the longest filibuster

Filibuster

A filibuster is a type of parliamentary procedure. Specifically, it is the right of an individual to extend debate, allowing a lone member to delay or entirely prevent a vote on a given proposal...

ever by a lone senator, in opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957

Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957, , primarily a voting rights bill, was the first civil rights legislation enacted by Congress in the United States since Reconstruction following the American Civil War.Following the historic US Supreme Court ruling in Brown v...

, at 24 hours and 18 minutes in length, nonstop. In the 1960s, he continued to fight against civil rights legislation. He always insisted he had never been a racist, but was merely opposed to excessive federal authority. However, he infamously said that "all the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement", while attributing the movement for integration to Communism. Starting in the 1970s, he moderated his position on race, but continued to defend his early segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

ist campaigns on the basis of states' rights

States' rights

States' rights in U.S. politics refers to political powers reserved for the U.S. state governments rather than the federal government. It is often considered a loaded term because of its use in opposition to federally mandated racial desegregation...

in the context of Southern society at the time, never fully renouncing his earlier viewpoints.

Six months after Thurmond's death in 2003, it was revealed that at age 22 he had fathered a daughter, Essie Mae Washington-Williams

Essie Mae Washington-Williams

Essie Mae Washington-Williams is the oldest child of former United States Senator and former Governor of South Carolina Strom Thurmond. Of mixed race, she was born to Carrie Butler, a 16-year-old African-American household servant, and Thurmond, then 22 and unmarried...

, with his family's African-American maid Carrie Butler, then 16. Although Thurmond never publicly acknowledged his daughter, he paid for her college education and passed other money to her for some time. The Thurmond family acknowledged her.

Early life and career

James Strom Thurmond was born on December 5, 1902, in Edgefield, South CarolinaEdgefield, South Carolina

Edgefield is a town in Edgefield County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 4,449 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Edgefield County.Edgefield is part of the Augusta, Georgia metropolitan area.-Geography:...

, the son of John William Thurmond (May 1, 1862 – June 17, 1934) and Eleanor Gertrude Strom (July 18, 1870 – January 10, 1958). He attended Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina (now Clemson University

Clemson University

Clemson University is an American public, coeducational, land-grant, sea-grant, research university located in Clemson, South Carolina, United States....

), where he was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity. Thurmond graduated in 1923 with a degree in horticulture

Horticulture

Horticulture is the industry and science of plant cultivation including the process of preparing soil for the planting of seeds, tubers, or cuttings. Horticulturists work and conduct research in the disciplines of plant propagation and cultivation, crop production, plant breeding and genetic...

.

After Thurmond's death in 2003, an attorney for his family confirmed that in 1925, when he was 22, Thurmond fathered a mixed-race daughter, Essie Mae Washington-Williams

Essie Mae Washington-Williams

Essie Mae Washington-Williams is the oldest child of former United States Senator and former Governor of South Carolina Strom Thurmond. Of mixed race, she was born to Carrie Butler, a 16-year-old African-American household servant, and Thurmond, then 22 and unmarried...

, with his family's housekeeper, Cassie Butler, then 16 years old. Thurmond paid for the girl's college education and provided other support.

He was a farmer, teacher and athletic coach until 1929, when he was appointed Edgefield County's superintendent of education, serving until 1933. Thurmond studied law with his father and was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1930. He served as the Edgefield Town and County attorney from 1930 to 1938. In 1933 Thurmond was elected to the South Carolina Senate

South Carolina Senate

The South Carolina Senate is the upper house of the South Carolina General Assembly, the lower house being the South Carolina House of Representatives...

and represented Edgefield until he was elected to the Eleventh Circuit judgeship.

World War II

In 1942, after the U.S. formally entered World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Judge Thurmond resigned from the bench to serve in the U.S. Army, rising to Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Air Force, and United States Marine Corps, a lieutenant colonel is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of major and just below the rank of colonel. It is equivalent to the naval rank of commander in the other uniformed services.The pay...

. In the Battle of Normandy (June 6 – August 25, 1944), he landed in a glider attached to the 82nd Airborne Division. For his military service, he received 18 decorations

Military decoration

A military decoration is a decoration given to military personnel or units for heroism in battle or distinguished service. They are designed to be worn on military uniform....

, medal

Medal

A medal, or medallion, is generally a circular object that has been sculpted, molded, cast, struck, stamped, or some way rendered with an insignia, portrait, or other artistic rendering. A medal may be awarded to a person or organization as a form of recognition for athletic, military, scientific,...

s and awards, including the Legion of Merit

Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit is a military decoration of the United States armed forces that is awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements...

with Oak Leaf Cluster

Oak leaf cluster

An oak leaf cluster is a common device which is placed on U.S. Army and Air Force awards and decorations to denote those who have received more than one bestowal of a particular decoration. The number of oak leaf clusters typically indicates the number of subsequent awards of the decoration...

, Bronze Star

Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal is a United States Armed Forces individual military decoration that may be awarded for bravery, acts of merit, or meritorious service. As a medal it is awarded for merit, and with the "V" for valor device it is awarded for heroism. It is the fourth-highest combat award of the...

with Valor device

Valor device

The Valor device is an award of the United States military which is a bronze attachment to certain medals to indicate that it was received for valor...

, Purple Heart

Purple Heart

The Purple Heart is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those who have been wounded or killed while serving on or after April 5, 1917 with the U.S. military. The National Purple Heart Hall of Honor is located in New Windsor, New York...

, World War II Victory Medal

World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a decoration of the United States military which was created by an act of Congress in July 1945. The decoration commemorates military service during World War II and is awarded to any member of the United States military, including members of the armed forces of...

, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

The European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal is a military decoration of the United States armed forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt...

, Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

's Order of the Crown

Order of the Crown (Belgium)

The Order of the Crown is an Order of Belgium which was created on 15 October 1897 by King Leopold II in his capacity as ruler of the Congo Free State. The order was first intended to recognize heroic deeds and distinguished service achieved from service in the Congo Free State - many of which acts...

and France's Croix de Guerre

Croix de guerre

The Croix de guerre is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was awarded during World War I, again in World War II, and in other conflicts...

.

During 1954–55 he was president of the Reserve Officers Association

Reserve Officers Association

The Reserve Officers Association is a professional association of officers, former officers, and spouses of all the uniformed services of the United States, primarily the Reserve and National Guard. Chartered by Congress and in existence since 1922, ROA advises and educates the Congress, the...

. He retired from the U.S. Army Reserves with the rank of Major General

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

.

Governor of South Carolina

Thurmond's political career began in the days of Jim Crow laws, when South Carolina strongly resisted any attempts at integration. Running as a Democrat, Thurmond was elected Governor of South CarolinaGovernor of South Carolina

The Governor of the State of South Carolina is the head of state for the State of South Carolina. Under the South Carolina Constitution, the Governor is also the head of government, serving as the chief executive of the South Carolina executive branch. The Governor is the ex officio...

in 1946, largely on the promise of making state government more transparent and accountable by weakening the power of a group of politicians from Barnwell

Barnwell, South Carolina

Barnwell is a city in Barnwell County, South Carolina, United States, located along U.S. Route 278. The population was 5,035 at the 2000 census...

, which Thurmond dubbed the Barnwell Ring

Barnwell Ring

The so-called "Barnwell Ring" was a grouping of influential Democratic South Carolina political leaders from Barnwell County. The group included state Senator Edgar A. Brown, state Representative Solomon Blatt, Sr., Governor Joseph Emile Harley, and state Representative Winchester Smith, Jr...

led by House Speaker Solomon Blatt

Solomon Blatt, Sr.

Solomon Blatt was a long time Democratic legislator of South Carolina from Barnwell County during the middle of the 20th century. He was a principal member of the so-called "Barnwell Ring."-Early life and career:...

. Thurmond was considered a progressive for much of his term, in large part due to his influence in arresting all those responsible for the lynch mob murder

Lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial execution carried out by a mob, often by hanging, but also by burning at the stake or shooting, in order to punish an alleged transgressor, or to intimidate, control, or otherwise manipulate a population of people. It is related to other means of social control that...

of Willie Earle. Though none of the men were found guilty by the jury, Thurmond was congratulated by the NAACP

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, usually abbreviated as NAACP, is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909. Its mission is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to...

and the ACLU

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union is a U.S. non-profit organization whose stated mission is "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States." It works through litigation, legislation, and...

for his efforts.

Run for President

In 1948, President Harry S. TrumanHarry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

desegregated the U.S. Army, proposed the creation of a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission

Fair Employment Practices Commission

The Fair Employment Practices Commission implemented US Executive Order 8802, requiring that companies with government contracts not to discriminate on the basis of race or religion. It was intended to help African Americans and other minorities obtain jobs in the homefront industry...

, supported the elimination of state poll taxes, and supported drafting federal anti-lynching

Lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial execution carried out by a mob, often by hanging, but also by burning at the stake or shooting, in order to punish an alleged transgressor, or to intimidate, control, or otherwise manipulate a population of people. It is related to other means of social control that...

laws. Thurmond became a candidate for President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

on the third party

Third party (politics)

In a two-party system of politics, the term third party is sometimes applied to a party other than the two dominant ones. While technically the term is limited to the third largest party or third oldest party, it is common, though innumerate, shorthand for any smaller party.For instance, in the...

ticket of the States' Rights Democratic Party

Dixiecrat

The States' Rights Democratic Party was a short-lived segregationist political party in the United States in 1948...

. It split from the national Democrats over what was perceived as federal intervention in the segregation practices of the Southern states, which, among other issues, had largely disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites by constitutional amendments and electoral requirements from 1890 to 1910. Thurmond carried four states and received 39 electoral votes. One 1948 speech, met with cheers by supporters, included the following:

Early runs for Senate

As Thurmond was constitutionally barred from seeking a second term as governor in 1950, he mounted a Democratic primary challenge against first-term U.S. Senator Olin Johnston. Both candidates denounced President Truman during the campaign. Johnston defeated Thurmond 186,180 votes to 158,904 votes (54% to 46%). It was the only statewide election Thurmond lost.In 1952, Thurmond endorsed Republican Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

for the Presidency, rather than the Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson. This led state Democratic Party leaders to block Thurmond from receiving the nomination to the Senate in 1954, forcing him to run as a write-in candidate.

1950s

Incumbent U.S. Senator Burnet R. MaybankBurnet R. Maybank

Burnet Rhett Maybank was a U.S. Senator, the 99th Governor of South Carolina, and Mayor of Charleston, South Carolina. Maybank was the direct descendant of six former South Carolinian governors. He was the first governor from Charleston since the Civil War...

was unopposed for re-election in 1954, but died in September of that year. Democratic leaders hurriedly appointed state Senator

South Carolina Senate

The South Carolina Senate is the upper house of the South Carolina General Assembly, the lower house being the South Carolina House of Representatives...

Edgar A. Brown, a member of the Barnwell Ring, as the party's nominee to replace Maybank. Widespread criticism of the party's failure to elect the nominee in a primary led to Thurmond announcing that he would mount a write-in campaign

United States Senate election in South Carolina, 1954

The 1954 South Carolina United States Senate election was held on November 2, 1954 to select the next U.S. Senator from the state of South Carolina. Senator Burnet R. Maybank did not face a primary challenge in the summer and was therefore renominated as the Democratic Party's nominee for the...

. He campaigned, at the recommendation of Governor James Byrnes

James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes was an American statesman from the state of South Carolina. During his career, Byrnes served as a member of the House of Representatives , as a Senator , as Justice of the Supreme Court , as Secretary of State , and as the 104th Governor of South Carolina...

, on a pledge that he would resign in 1956 to trigger a contested primary. Thurmond won overwhelmingly, becoming the first person to be elected to the U.S. Senate as a write-in candidate

Write-in candidate

A write-in candidate is a candidate in an election whose name does not appear on the ballot, but for whom voters may vote nonetheless by writing in the person's name. Some states and local jurisdictions allow a voter to affix a sticker with a write-in candidate's name on it to the ballot in lieu...

against ballot-listed opponents. Following through on his campaign promise, he resigned in 1956 and then won the Democratic primary—in those days, the real contest in South Carolina—for the special election triggered by his own vacancy. His career in the Senate remained uninterrupted until his retirement 46 years later, despite his mid-career party switch.

Thurmond vehemently supported racial segregation with the longest filibuster ever conducted by a single senator, speaking for a total of 24 hours and 18 minutes in an unsuccessful attempt to derail the Civil Rights Act of 1957

Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957, , primarily a voting rights bill, was the first civil rights legislation enacted by Congress in the United States since Reconstruction following the American Civil War.Following the historic US Supreme Court ruling in Brown v...

. Cots were brought in from a nearby hotel for the legislators to sleep on while Thurmond discussed increasingly irrelevant and obscure topics, including his grandmother's biscuit recipe. Other Southern senators, who had agreed as part of a compromise not to filibuster this bill, were upset with Thurmond because they thought his defiance made them look incompetent to their constituents.

According to journalist Jeff Sharlet

Jeff Sharlet

Jeff Sharlet is an American journalist, bestselling author, and academic best known for writing about religious subcultures in the United States. He is a contributing editor for Harper's and Rolling Stone...

, he was a member of the Family (also known as the Fellowship), described by prominent evangelical Christians as one of the most politically well connected Christian organizations in the U.S.

1960s

Thurmond was increasingly at odds with the Democratic Party. On September 16, 1964, he switched his party affiliation

Party switching in the United States

In the United States politics, party switching is any change in party affiliation of a partisan public figure, usually one who is currently holding elected office...

to Republican. He played an important role in South Carolina's support for Republican presidential

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

candidates Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater was a five-term United States Senator from Arizona and the Republican Party's nominee for President in the 1964 election. An articulate and charismatic figure during the first half of the 1960s, he was known as "Mr...

in 1964

United States presidential election, 1964

The United States presidential election of 1964 was held on November 3, 1964. Incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had come to office less than a year earlier following the assassination of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy. Johnson, who had successfully associated himself with Kennedy's...

and Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

in 1968

United States presidential election, 1968

The United States presidential election of 1968 was the 46th quadrennial United States presidential election. Coming four years after Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson won in a historic landslide, it saw Johnson forced out of the race and Republican Richard Nixon elected...

. South Carolina and other states of the Deep South

Deep South

The Deep South is a descriptive category of the cultural and geographic subregions in the American South. Historically, it is differentiated from the "Upper South" as being the states which were most dependent on plantation type agriculture during the pre-Civil War period...

had supported the Democrats in every national election from the end of Reconstruction, when white Democrats re-established political control in the South, to 1960. However, discontent with the Democrats' increasing support for civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

resulted in John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

's barely winning the state in 1960

United States presidential election, 1960

The United States presidential election of 1960 was the 44th American presidential election, held on November 8, 1960, for the term beginning January 20, 1961, and ending January 20, 1965. The incumbent president, Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, was not eligible to run again. The Republican Party...

. After Kennedy's assassination

Assassination

To carry out an assassination is "to murder by a sudden and/or secret attack, often for political reasons." Alternatively, assassination may be defined as "the act of deliberately killing someone, especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons."An assassination may be...

, President Lyndon Johnson's strong support for the Civil Rights Act

Civil Rights Act

Civil Rights Act may refer to several acts in the history of civil rights in the United States, including:-Federal legislation:* Civil Rights Act of 1866, extending the rights of emancipated slaves...

of 1964 and integration angered white segregationists even more. Goldwater won South Carolina by a large margin in 1964.

In 1968, Richard Nixon ran the first GOP "Southern strategy

Southern strategy

In American politics, the Southern strategy refers to the Republican Party strategy of winning elections in Southern states by exploiting anti-African American racism and fears of lawlessness among Southern white voters and appealing to fears of growing federal power in social and economic matters...

" campaign appealing to disaffected southern white voters. Although segregationist Democrat George Wallace

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace, Jr. was the 45th Governor of Alabama, serving four terms: 1963–1967, 1971–1979 and 1983–1987. "The most influential loser" in 20th-century U.S. politics, according to biographers Dan T. Carter and Stephan Lesher, he ran for U.S...

was on the ballot, Nixon ran slightly ahead of him and gained South Carolina's electoral

United States Electoral College

The Electoral College consists of the electors appointed by each state who formally elect the President and Vice President of the United States. Since 1964, there have been 538 electors in each presidential election...

votes. Due to the antagonism of white South Carolina voters toward the national Democratic Party, Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey, Jr. , served under President Lyndon B. Johnson as the 38th Vice President of the United States. Humphrey twice served as a United States Senator from Minnesota, and served as Democratic Majority Whip. He was a founder of the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party and...

received less than 30% of the total vote, carrying only majority-black districts.

At the 1968 Republican National Convention

1968 Republican National Convention

The 1968 National Convention of the Republican Party of the United States was held in at the Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Dade County, Florida, from August 5 to August 8, 1968....

in Miami Beach, Thurmond played a key role in keeping Southern delegates committed to Nixon, despite the sudden last-minute entry of California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

Governor Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

into the race. Thurmond also quieted conservative fears over rumors that Nixon planned to ask either Charles Percy

Charles H. Percy

Charles Harting "Chuck" Percy was president of the Bell & Howell Corporation from 1949 to 1964. He was elected United States Senator from Illinois in 1966, re-elected through his term ending in 1985; he concentrated on business and foreign relations...

or Mark Hatfield

Mark Hatfield

Mark Odom Hatfield was an American politician and educator from the state of Oregon. A Republican, he served for 30 years as a United States Senator from Oregon, and also as chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee...

—liberal Republicans—to be his running mate, by making it known to Nixon that both men were unacceptable for the vice-presidency to the South. Nixon ultimately asked Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

Governor Spiro Agnew

Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew was the 39th Vice President of the United States , serving under President Richard Nixon, and the 55th Governor of Maryland...

—an acceptable choice to Thurmond—to join the ticket.

At this time, too, Thurmond took the lead in thwarting Johnson's attempt to elevate Justice Abe Fortas

Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas was a U.S. Supreme Court associate justice from 1965 to 1969. Originally from Tennessee, Fortas became a law professor at Yale, and subsequently advised the Securities and Exchange Commission. He then worked at the Interior Department under Franklin D...

to the post of Chief Justice

Chief Justice

The Chief Justice in many countries is the name for the presiding member of a Supreme Court in Commonwealth or other countries with an Anglo-Saxon justice system based on English common law, such as the Supreme Court of Canada, the Constitutional Court of South Africa, the Court of Final Appeal of...

of the United States. Thurmond's conservatism left him unhappy with the Warren Court

Earl Warren

Earl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

. He was glad to simultaneously to disappoint Johnson and to leave the task of replacing Warren to Johnson's presidential successor Richard Nixon.

Thurmond decried the Supreme Court opinion in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, which ordered the immediate desegregation of schools in the American South. Thurmond praised President Nixon and his "Southern Strategy" of delaying desegregation, saying Nixon "stood with the South in this case".

1970s

Thanks to his close relationship with the Nixon administration, Thurmond found himself in a position to deliver a great deal of federal money, appointments and projects to his state. With a like-minded president in the White House, Thurmond became a very effective power broker in Washington. His staffers said that he aimed to become South Carolina's "indispensable man" in D.C.On February 4, 1972, Thurmond sent a secret memo to William Timmons

William Timmons

William E. Timmons is a United States lobbyist in Washington, D.C. who has worked for all of the Republican presidents of the United States since Richard Nixon, as well as Jimmy Carter...

(in his capacity as an aide to Richard Nixon) and United States Attorney General

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

John N. Mitchell

John N. Mitchell

John Newton Mitchell was the Attorney General of the United States from 1969 to 1972 under President Richard Nixon...

, with an attached file from the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee urging that British musician John Lennon (living in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

at the time) be deported from the United States as an undesirable alien, due to Lennon's political views and activism. The document claimed that Lennon's influence on young people could affect Nixon's chances of re-election, and suggested that terminating Lennon's visa might be "a strategy counter-measure". Thurmond's memo and attachment, received by the White House on February 7, 1972, initiated the Nixon administration's persecution of John Lennon that threatened the former Beatle with deportation for nearly five years from 1972 to 1976. The documents were discovered in the FBI files after a Freedom of Information Act search by Professor Jon Wiener

Jon Wiener

Jon Wiener is an American professor of history at the University of California Irvine, a contributing editor to The Nation magazine, and a Los Angeles radio host. He was the plaintiff in a Freedom of Information lawsuit against the Federal Bureau of Investigation for its files on John Lennon.-...

, published in Weiner's book Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files (2000), and are discussed in the documentary

Documentary

A documentary is a creative work of non-fiction, including:* Documentary film, including television* Radio documentary* Documentary photographyRelated terms include:...

film The U.S. vs. John Lennon (2006).

In 1976

United States presidential election, 1976

The United States presidential election of 1976 followed the resignation of President Richard Nixon in the wake of the Watergate scandal. It pitted incumbent President Gerald Ford, the Republican candidate, against the relatively unknown former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, the Democratic...

, he appeared in a campaign commercial for incumbent President Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph "Jerry" Ford, Jr. was the 38th President of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977, and the 40th Vice President of the United States serving from 1973 to 1974...

in his race against Thurmond's fellow Southerner

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

, former Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

governor Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

. In the commercial, Thurmond declared that Ford (who was born in Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska is a state on the Great Plains of the Midwestern United States. The state's capital is Lincoln and its largest city is Omaha, on the Missouri River....

and spent most of life in Michigan

Michigan

Michigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

) "sound[ed] more like a Southerner

Politics of the Southern United States

Politics of the Southern United States refers to the political landscape of the Southern United States. Due to the region's unique cultural and historic heritage, the American South has been prominently involved in numerous political issues faced by the United States as a whole, including States'...

than Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

".

Post-1970 views regarding race

In 1970, blacks were about 30% of South Carolina's population. After the 1965 Voting Rights ActVoting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of national legislation in the United States that outlawed discriminatory voting practices that had been responsible for the widespread disenfranchisement of African Americans in the U.S....

was passed, African Americans were protected in exercising their constitutional rights as citizens to vote, and were generally able to register and vote without harassment. Their large numbers, combined with those of whites who supported civil rights, could no longer be ignored by state politicians.

Thurmond appointed African American Thomas Moss to his staff in 1971, described as the first appointment by a member of the South Carolinian congressional delegation (also incorrectly reported by many sources as the first senatorial appointment of an African American, but Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison

Pat Harrison

Byron Patton "Pat" Harrison was a Mississippi politician who served as a Democrat in the United States House of Representatives from 1911 to 1919 and in the United States Senate from 1919 until his death....

had hired clerk-librarian Jesse Nichols in 1937). In 1983, he voted to make the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

a federal holiday. In South Carolina, the honor was diluted, as until 2000 the state offered employees the option to celebrate this holiday or substitute one of three Confederate holidays instead. Despite his actions, Thurmond never explicitly renounced his earlier views on racial segregation.

Later career

President pro tempore of the United States Senate

The President pro tempore is the second-highest-ranking official of the United States Senate. The United States Constitution states that the Vice President of the United States is the President of the Senate and the highest-ranking official of the Senate despite not being a member of the body...

in 1981, and held the largely ceremonial post for three terms, alternating with his longtime rival Robert Byrd

Robert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd was a United States Senator from West Virginia. A member of the Democratic Party, Byrd served as a U.S. Representative from 1953 until 1959 and as a U.S. Senator from 1959 to 2010...

depending on the party composition of the Senate. During this period, he maintained a close relationship with the Reagan White House.

Thurmond served as the ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee during the Clarence Thomas hearings in 1991 and worked closely with Joe Biden

Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette "Joe" Biden, Jr. is the 47th and current Vice President of the United States, serving under President Barack Obama...

, then the chairman. He also joined the minority of Republicans who voted for the Brady Bill

Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act is an Act of the United States Congress that, for the first time, instituted federal background checks on firearm purchasers in the United States....

in 1993.

On December 5, 1996, Thurmond became the oldest serving member of the U.S. Senate, and on May 25, 1997, the longest-serving member (41 years and 10 months). He cast his 15,000th vote in September 1998.

Declining to seek re-election in 2002, he was succeeded by fellow Republican Lindsey Graham

Lindsey Graham

Lindsey Olin Graham is the senior U.S. Senator from South Carolina and a member of the Republican Party. Previously he served as the U.S. Representative for .-Early life, education and career:...

.

Thurmond left the Senate in January 2003 as the United States' longest-serving senator (a record later surpassed by Senator Byrd). In his November farewell speech in the Senate, Thurmond told all his colleagues "I love all of you, especially your wives," the latter being a reference to his flirtatious nature with younger women.

At his 100th birthday and retirement celebration in December, Thurmond stated "I don't know how to thank you. You're wonderful people, I appreciate you, appreciate what you've done for me, and may God allow you to live a long time.

Thurmond's 100th birthday celebration, however, became controversial after Mississippi Senator Trent Lott

Trent Lott

Chester Trent Lott, Sr. , is a former United States Senator from Mississippi and has served in numerous leadership positions in the House of Representatives and the Senate....

made comments that were viewed as racially insensitive: "When Strom Thurmond ran for president, [Mississippi] voted for him. We're proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn't have had all these problems over the years, either." These comments led to Lott's ouster as Senate Majority Leader.

Marriages and children

Thurmond married his first wife, Jean Crouch (July 24, 1926 – January 6, 1960) in South Carolina's Governor's mansion on November 7, 1947. In April 1947, when Crouch was a senior at Winthrop College, Thurmond was a judge in a beauty contest in which she was selected as Miss South Carolina. In June, upon her graduation, Thurmond hired her as his personal secretary. On September 13, 1947, Thurmond proposed marriage by calling Crouch to his office to take a dictated letter. The letter was to her, and contained his proposal of marriage. Crouch died of a brain tumorBrain tumor

A brain tumor is an intracranial solid neoplasm, a tumor within the brain or the central spinal canal.Brain tumors include all tumors inside the cranium or in the central spinal canal...

13 years later; there were no children.

He married his second wife, Nancy Janice Moore (born 1946), Miss South Carolina

Miss South Carolina

The Miss South Carolina competition is the pageant that selects the representative for the state of South Carolina in the Miss America pageant. The pageant was first held in Myrtle Beach and moved to Greenville starting in 1958 and remained in that city until the 90s. Spartanburg has hosted the...

of 1965, on December 22, 1968. He was 66 years old and she was only 22. She had been working in his Senate office off and on since 1967. It is often said that he ran for president before she was born. This is false; however, he was old enough to be eligible. They separated in 1991, but never divorced. The two remained married and close friends until his death. He even considered resigning during his last term, but only if the Governor would appoint his wife to the seat as his replacement.

At age 68 (with his wife Nancy at age 25) Thurmond fathered what was then believed to be his first child. His four children with Nancy are: beauty pageant contestant Nancy Moore Thurmond (1971–1993), who was killed when a drunk driver hit her in Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the state capital and largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The population was 129,272 according to the 2010 census. Columbia is the county seat of Richland County, but a portion of the city extends into neighboring Lexington County. The city is the center of a metropolitan...

; former U.S. Attorney for the District of South Carolina and current South Carolina 2nd Judicial Circuit Solicitor James Strom Thurmond Jr. (born 1972); Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, homemaker Juliana Gertrude Thurmond Whitmer (born 1973); and Charleston County, South Carolina

Charleston County, South Carolina

Charleston County is a county located in the U.S. state of South Carolina. According to a 2005 U.S. Census Bureau estimate, its population was 330,368. Its county seat is Charleston. It is the third-most populous county in the state . Charleston County was created in 1901 by an act of the South...

, Council Member Paul Reynolds Thurmond (born 1976).

Death

Thurmond died in his sleep on June 26, 2003, at 9:45 p.m. of heart failure at a hospital in Edgefield, South Carolina. He was 100 years old. After lying in state in the rotunda of the State House in Columbia, a caisson carried his body to the First Baptist Church for services where then-Senator Joe BidenJoe Biden

Joseph Robinette "Joe" Biden, Jr. is the 47th and current Vice President of the United States, serving under President Barack Obama...

delivered a eulogy, and later to the family burial plot in Willowbrook Cemetery in Edgefield where he was interred.

Another daughter

Six months after Thurmond's death, Essie Mae Washington-WilliamsEssie Mae Washington-Williams

Essie Mae Washington-Williams is the oldest child of former United States Senator and former Governor of South Carolina Strom Thurmond. Of mixed race, she was born to Carrie Butler, a 16-year-old African-American household servant, and Thurmond, then 22 and unmarried...

, an African-American woman of bright complexion, publicly revealed that she was Strom Thurmond's daughter. She was born to Carrie "Tunch" Butler (1909–1948), a maid who had worked for Thurmond's parents, on October 12, 1925, when Butler was sixteen years old and Thurmond twenty-two. He helped pay his daughter's way through college. Though Thurmond never publicly acknowledged Washington-Williams while he was alive, he continued to support her financially. These payments extended well into her adult life. Washington-Williams has stated that she did not reveal she was Thurmond's daughter during his lifetime because it "wasn't to the advantage of either one of us". She kept silent out of love and respect for her father and denies that there was an agreement between the two not to reveal her connection to Thurmond.

After Washington-Williams came forward, the Thurmond family publicly acknowledged her parentage. Many close friends, staff members, and South Carolina residents had long suspected Washington-Williams was his daughter, saying that Thurmond had always taken a great deal of interest in her. The young mixed-race woman had been granted a degree of access to Thurmond more appropriate to a family member than to a member of the public. Washington-Williams is eligible for membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution

Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution is a lineage-based membership organization for women who are descended from a person involved in United States' independence....

and the United Daughters of the Confederacy

United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy is a women's heritage association dedicated to honoring the memory of those who served in the military and died in service to the Confederate States of America . UDC began as the National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy, organized in 1894 by...

through her Thurmond ancestry. Thurmond was a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans

Sons of Confederate Veterans

Sons of Confederate Veterans is an American national heritage organization with members in all fifty states and in almost a dozen countries in Europe, Australia and South America...

, a similar group for men.

Political timeline

- Governor of South Carolina (1947–1951)

- States' Rights Democratic presidential candidate (1948)

- Eight-term senator from South CarolinaSouth CarolinaSouth Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

(December 1954 – April 1956 and November 1956 – January 2003)- Democrat (1954 – April 1956 and November 1956 – September 1964)

- Republican (September 1964 – January 2003)

- President pro tempore (1981–1987; 1995 – January 3, 2001; January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001)

- Set record for the longest one-man Congressional filibusterFilibusterA filibuster is a type of parliamentary procedure. Specifically, it is the right of an individual to extend debate, allowing a lone member to delay or entirely prevent a vote on a given proposal...

(1957) - Set record for oldest serving member at 94 years (1997)

- Set the then-record for longest cumulative tenure in the Senate at 43 years (1997), increasing to 47 years, 6 months at his retirement in January 2003, surpassed by Robert ByrdRobert ByrdRobert Carlyle Byrd was a United States Senator from West Virginia. A member of the Democratic Party, Byrd served as a U.S. Representative from 1953 until 1959 and as a U.S. Senator from 1959 to 2010...

in July 2006 - Became the only senator ever to serve at the age of 100CentenarianA centenarian is a person who is or lives beyond the age of 100 years. Because current average life expectancies across the world are less than 100, the term is invariably associated with longevity. Much rarer, a supercentenarian is a person who has lived to the age of 110 or more, something only...

Legacy

- The Strom Thurmond Foundation, Inc. provides financial aid support to deserving South Carolina residents who demonstrate financial need. The Foundation was established in 1974 by Thurmond with honoraria received from speeches, donations from friends and family, and from other acts of generosity. It serves as a permanent testimony to his memory, and to his concern for the education of able students who have demonstrated financial need.

- Thurmond is mentioned in a 1993 FrasierFrasierFrasier is an American sitcom that was broadcast on NBC for eleven seasons, from September 16, 1993, to May 13, 2004. The program was created and produced by David Angell, Peter Casey, and David Lee in association with Grammnet and Paramount Network Television.A spin-off of Cheers, Frasier stars...

episode entitled "Here's Looking at You". In the episode Frasier's son Frederick is afraid that Thurmond is hiding in his bedroom closet. - A reservoir on the GeorgiaGeorgia (U.S. state)Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

–South CarolinaSouth CarolinaSouth Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

border is named after him: Lake Strom ThurmondLake Strom ThurmondLake Strom Thurmond, known in Georgia as Clarks Hill Lake, is a reservoir at the border between Georgia and South Carolina in the Savannah River Basin. It was created by the J. Strom Thurmond Dam during 1951 and 1952 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers near the confluence of the "Little River" and...

. - The University of South CarolinaUniversity of South CarolinaThe University of South Carolina is a public, co-educational research university located in Columbia, South Carolina, United States, with 7 surrounding satellite campuses. Its historic campus covers over in downtown Columbia not far from the South Carolina State House...

is home to the Strom Thurmond Fitness Center, one of the largest fitness complexes on a college campus. The new complex has largely replaced the Blatt Fitness center, named for Solomon BlattSolomon Blatt, Sr.Solomon Blatt was a long time Democratic legislator of South Carolina from Barnwell County during the middle of the 20th century. He was a principal member of the so-called "Barnwell Ring."-Early life and career:...

, a political rival of Thurmond.

- Charleston Southern UniversityCharleston Southern UniversityCharleston Southern University, founded in 1964 as Baptist College, is an independent comprehensive university located in North Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston Southern enrolls a maximum of 3,200 students. Affiliated with the South Carolina Baptist Convention, the university's mission is...

has a Strom Thurmond Building, which houses the school's business offices, bookstore, and post office. - Thurmond Building at Winthrop UniversityWinthrop UniversityWinthrop University is a public, four-year liberal arts university in Rock Hill, South Carolina, USA. In 2006-07, Winthrop University had an enrollment of 6,292 students. The University has been recognized as South Carolina's top-rated university according to evaluations conducted by the South...

is named for him. He served on Winthrop's Board of Trustees from 1936 to 1938 and again from 1947 to 1951 when he was governor of South Carolina. - A statue of Strom Thurmond is located on the grounds of the South Carolina State Capitol as a memorial to his service to the state.

- Strom Thurmond High SchoolStrom Thurmond High SchoolStrom Thurmond High School is located in Johnston, South Carolina, a town in Edgefield County. It is named for Strom Thurmond who served as Governor of South Carolina , and Eight-term senator from South Carolina...

is located in his hometown of Edgefield, South CarolinaEdgefield, South CarolinaEdgefield is a town in Edgefield County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 4,449 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Edgefield County.Edgefield is part of the Augusta, Georgia metropolitan area.-Geography:...

. - Al SharptonAl SharptonAlfred Charles "Al" Sharpton, Jr. is an American Baptist minister, civil rights activist, and television/radio talk show host. In 2004, he was a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. presidential election...

was reported on February 24, 2007, to be a descendent of slaves owned by the Thurmond family. Sharpton has not asked for a DNA test. - The U.S. Air Force has a C-17 Globemaster named The Spirit of Strom Thurmond.

- In 1989 he was presented with the Presidential Citizens MedalPresidential Citizens MedalThe Presidential Citizens Medal is the second highest civilian award in the United States, second only to the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is awarded by the President of the United States, and may be given posthumously....

by President Ronald ReaganRonald ReaganRonald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....