Strombus gigas

Encyclopedia

Lobatus gigas, commonly

known as the queen conch, is a species

of large edible sea snail

, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family of true conchs, the Strombidae

. This species is one of the largest mollusks native to the Tropical Northwestern Atlantic, from Bermuda

to Brazil, reaching up to 35.2 cm (13.9 in) in shell length.

The queen conch is herbivorous and lives in seagrass

beds, although the exact habitat varies during the different stages of its development. The adult animal has a very large, solid and heavy shell

, with knob-like spines on the shoulder, a flared thick outer lip

and a characteristic pink-colored aperture

(opening). The flared lip is completely absent in younger specimens. The external anatomy of the soft parts of L. gigas is similar to that of other snails in the same family: it has a long snout

, two eyestalk

s with well-developed eyes and additional sensory tentacles, a strong foot and a corneous

sickle

-shaped operculum

.

The shell and soft parts of living Lobatus gigas serve as a home to several different kinds of commensal animals, including slipper snail

s, porcelain crab

s and cardinal fish. Its parasites include coccidia

ns. The queen conch is hunted and eaten by several species of large predatory sea snails, and also by starfish, crustacean

s and vertebrates (fish, sea turtle

s and humans). The meat of this sea snail is consumed by humans in a wide variety of dishes. The shell is sold as a souvenir

and used as a decorative object. Historically, Native American

s and indigenous Caribbean peoples used parts of the shell to create various tools.

International trade in queen conch is regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) agreement, in which it is listed as Strombus gigas. This species is not yet truly endangered in the Caribbean as a whole, but it is commercially threatened in numerous areas, largely due to extreme overfishing; the meat is an important food source for humans. The CITES regulations are designed to monitor and control the commercial export of the meat of this species as well as the shells (often sold to be used as decorative objects). Both of these trades were previously so prevalent that they represented serious threats to the survival of the species. However, the CITES Convention does not monitor or regulate any domestic use.

and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus in his ground-breaking book . Linnaeus named the species Strombus gigas, and that remained the accepted name for over two hundred years. Linnaeus did not mention a specific locality for this species in his description, giving only "America" as the type locality. The specific name is the Ancient Greek

word , which means "giant", referring to the large size of this snail compared with almost all other gastropod mollusks. Strombus lucifer, which was considered to be a synonym much later, was also described by Linnaeus in Systema Naturae.

In the first half of the 20th century, the type material for the species was thought to have been lost; in other words, the shell on which Linnaeus based his original description and which would very likely have been in his own collection, was apparently missing, and without type material to formally define the species, this created a problem for taxonomists. To remedy this, in 1941 a neotype of this species was designated by the American malacologists William J. Clench

and R. Tucker Abbott

. In this case, the neotype was not an actual shell or whole specimen

, but a figure from a book that was published in the 17th century, 23 years before Linnaeus was even born, the 1684 by the Italian scholar Filippo Buonanni. This was the first book published that was solely about seashell

s. In 1953 however, the Swedish malacologist Nils Hjalmar Odhner

searched the Linnaean Collection at Uppsala University

and discovered the original shell upon which Linnaeus had based his description, thereby invalidating Clench and Abbott's neotype designation.

The family Strombidae

has recently undergone an extensive taxonomic revision, and a few subgenera

, including Eustrombus

, were elevated to genus

level by some authors. Petuch (2004) and Petuch and Roberts (2007) recombined this species as Eustrombus gigas, and Landau et al. (2008) recombined it as Lobatus gigas.

, , , and in Venezuela

, and in the Dominican Republic

.

of this species is usually 15–31 cm (6–12 in) in length, and the maximum reported size is 35.2 cm (13.9 in). The shell is very solid and heavy, with 9 to 11 whorls

and a widely flaring and thickened outer lip. In the shells of adult snails, a structure called the stromboid notch

is present on the edge of the lip. Although this notch is not as well developed in this species as it is in many other species in the same family, the shell feature is nonetheless visible in an adult dextral (normal right-handed) specimen, as a secondary anterior indentation in the lip of the shell, to the right of the siphonal canal

, assuming the shell is viewed ventrally. In life, the animal's left eyestalk protrudes through this notch.

The spire

(a protruding part of the shell which includes all of the whorls with the exception of the largest and final whorl, known as the body whorl

) is usually higher (more elongated) in this species than it is in the shells of other strombid snails, such as the closely related and even larger goliath conch, Lobatus goliath, a species endemic to Brazil. In Lobatus gigas, the glossy finish or glaze around the aperture

of the adult shell is colored primarily in shades of pink. This pink glaze is usually pale, and may show a cream, peach or yellow coloration, but it can also sometimes be tinged with a deep magenta

, shading almost to red. The periostracum

, a layer of protein (conchiolin

) which is the outermost part of the shell surface, is thin and a pale brown or tan color in this species.

The overall shell morphology

The overall shell morphology

of L. gigas is not solely determined by the animal's genes; environmental conditions such as geographic location, food supply, temperature and depth, and biological interactions such as exposure to predation, can greatly affect it. Juvenile conchs develop heavier shells when exposed to predators compared to those that are not exposed to predators. Conchs also develop wider and thicker shells with fewer but longer spines when they are living in deeper water.

The shells of very small juvenile queen conchs are strikingly different in appearance from those of the adults. Noticeable is the complete absence of a flared outer lip; juvenile shells have a simple sharp lip, which gives the shell a conical

or biconic outline. In Florida

, juvenile queen conchs are known as "rollers", because wave action very easily rolls their shells, whereas it is nearly impossible to roll the shell of an adult specimen, due to its weight and asymmetrical profile. Subadult shells have a flared lip which is however very thin; the flared outer lip of an adult shell constantly increases in thickness with age, until death.

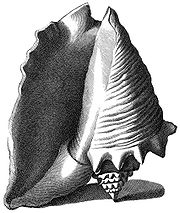

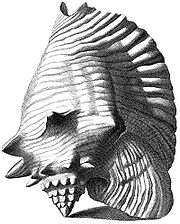

and malacologist Niccolò Gualtieri

) contains three illustrations showing the morphology of adult queen conch shells from different perspectives. The knobbed spire and the flaring outer lip, with its somewhat wing-like contour expanding out from the last whorl

, is a striking feature of these images. The shells are shown as if balancing on the edge of the lip and/or the apex; this was presumably done for artistic reasons as these shells cannot be balanced like this.

Considered as one of the most prized and sumptuous shell publications of the 19th century, a series of books titled (published by the French naturalist Jean-Charles Chenu

from 1842 to 1853), contains several illustrations of both adult and juvenile L. gigas shells, and one uncolored drawing depicting some of the animal's soft parts. Almost forty years later, a colored illustration from the Manual of Conchology (published in 1885 by the American malacologist George Washington Tryon

) shows a dorsal view of a small juvenile shell with its typical brown and white patterning.

Many details about the anatomy of Lobatus gigas were not well known until 1965, when the zoologist Colin Little published a general study on the subject. More recently, in 2005, the Brazilian malacologist Luiz R. L. Simone gave a detailed anatomical description of the species.

Many details about the anatomy of Lobatus gigas were not well known until 1965, when the zoologist Colin Little published a general study on the subject. More recently, in 2005, the Brazilian malacologist Luiz R. L. Simone gave a detailed anatomical description of the species.

Lobatus gigas has a long extensible snout

with two eyestalks (also known as ommatophores) that originate from its base. The tip of each eyestalk contains a large, well-developed lens

eye, with a black pupil

and a yellow iris

(if amputated, the eyes can be completely regenerated

), and a small slightly posterior sensory tentacle. Inside the mouth of the animal is a radula

(a tough ribbon covered in rows of microscopic teeth) of the taenioglossan type.

Both the snout and the eyestalks show dark spotting in the exposed areas. The mantle

is darkly colored in the anterior region, fading to light gray at the posterior end, while the mantle collar is commonly orange, and the siphon is also orange or yellow.

When the soft parts of the animal are removed from the shell, several organs are distinguishable externally, including the kidney, the nephiridial

gland, the pericardium

, the genital glands

, stomach, style sac, and the digestive gland. In adult males, the penis is also visible.

Lobatus gigas has a large and powerful foot, which has brown spots and markings towards the edge, but is white nearer to the visceral hump (the part of the animal that stays inside, protected by the shell, and which accommodates a number of internal organs). The base of the anterior end of the foot has a distinct groove, which contains the opening of the pedal gland

Lobatus gigas has a large and powerful foot, which has brown spots and markings towards the edge, but is white nearer to the visceral hump (the part of the animal that stays inside, protected by the shell, and which accommodates a number of internal organs). The base of the anterior end of the foot has a distinct groove, which contains the opening of the pedal gland

. Attached to the posterior end of the foot for about one third of its length is the dark brown, corneous

, sickle

-shaped operculum

, which is reinforced by a distinct central rib. The base of the posterior two-thirds of the animal's foot is rounded; only the anterior third of the foot is applied to the substrate during locomotion.

The columella, the central pillar within the shell, serves as the attachment point for the white collumellar muscle. Contraction of this large strong muscle allows all of the soft parts of the animal to withdraw into the shell in response to undesirable stimuli.

Although the species undoubtedly occurs in more individual places than are listed here, the countries, regions, and islands where this species has been recorded within the scientific literature

as occurring are, in alphabetical order:

Aruba

Aruba

, of the Netherlands Antilles

; Barbados

; all of the islands and cays of the Bahamas; Belize

; Bermuda

; North and northeastern regions of Brazil (though this is contested by some authors); Old Providence Island in Colombia

; Costa Rica

; the Dominican Republic

; Panama

; Swan Islands

in Honduras

; Jamaica

; Martinique

; Alacran Reef, Campeche

, Cayos Arcas

and Quintana Roo

, in Mexico

; Puerto Rico

; Saint Barthélemy

; Mustique

and Grenada

in the Grenadines; Pinar del Río

, North Havana Province

, North Matanzas

, Villa Clara

, Cienfuegos

, Holguín

, Santiago de Cuba

and Guantánamo, in the Turks and Caicos Islands and Cuba; South Carolina

, Florida

, including East Florida, West Florida, the Florida Keys and the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, in the United States; Carabobo

, Falcon, Gulf of Venezuela, Los Roques archipelago

, Los Testigos Islands

and Sucre

in Venezuela; St. Croix in the Virgin Islands

.

, which was described in 1922 by the American zoologist George Howard Parker

(1864–1955). The animal first fixes the posterior end of the foot by thrusting the point of the sickle-shaped operculum into the substrate, then it extends the foot in a forward direction, lifting and throwing the shell forward in a so-called leaping motion. This way of moving is considered to resemble that of pole vaulting, making L. gigas a good climber even of vertical concrete surfaces. This odd leaping form of locomotion may also help prevent predators from following the snail's chemical traces, which would otherwise be a continuous trail on the substrate

.

meadows and on sandy substrate

, usually in association with turtle grass (species of the genus Thalassia

, namely Thalassia testudinum and also Syringodium

sp.) and manatee grass (Cymodocea

sp.). Juvenile individuals are found in shallow, inshore seagrass meadows, which are different from the deeper algal plains and seagrass meadows where adult individuals live.

The critical nursery habitats

for juvenile individuals are defined by a series of combined factors, both habitat characteristics (such as tidal circulation

) and ecological processes (such as macroalgal production), which together provide high rates of both recruitment

and survival. Lobatus gigas is typically found in distinct aggregates, which may contain several thousand individuals.

, which means each individual snail is either distinctly male or distinctly female. Females are usually larger than males in natural populations, with both sexes existing in similar proportion. After internal fertilization

, the females lay eggs in gelatinous strings, which can be as long as 75 feet (or about 23 m). These are layered on patches of bare sand or seagrass. The sticky surface of these long egg strings allows them to coil and agglutinate, mixing with the surrounding sand to form compact egg masses, the shape of which is defined by the anterior portion of the outer lip of the female's shell while they are layered. Each one of the egg masses may have been fertilized by multiple males. The number of eggs per egg mass may vary greatly depending on environmental conditions, such as food limitation and temperature. Commonly, females produce an average of 8–9 egg masses per season, each containing 180,000–460,000 eggs, but numbers can be as high as 750,000 eggs per egg mass depending upon the conditions. Lobatus gigas females may spawn multiple times during the reproductive season, which lasts from March to October, with activity peaks occurring from July to September.

After hatching, the emerging two-lobed veliger

(a larval form common to various marine and fresh-water gastropod and bivalve mollusks) spend several days developing in the plankton

, feeding primarily on phytoplankton

. Metamorphosis

occurs in about 16–40 days from the hatching, when the fully grown protoconch

(embryonic shell) is about 1.2 mm high. After the metamorphosis, Lobatus gigas individuals spend the rest of their lives in the benthic zone

(on or in the sediment surface), usually remaining buried during their first year of life.

The queen conch is known to reach sexual maturity at approximately 3 to 4 years of age, reaching a shell length of nearly 180 mm and weighing up to 5 pounds. Individuals may usually live up to 7 years, though in deeper waters their lifespan may reach 20–30 years and maximum lifetime estimates reach 40 years. It is believed that the mortality rate

tends to be lower in matured conchs due to their thickened shell, but it could be substantially higher for juveniles. Estimates have demonstrated that the mortality rate of L. gigas decreases as the animal size increases, and can also vary due to habitat, season and other factors.

s by several authors in the 19th century, a conception that persisted until the first half of the 20th century. This erroneous idea probably originated in the writings of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

, who classified strombids alongside other supposedly carnivorous snails, and this idea was subsequently repeated by other authors. The claims of these authors, however, were not supported by any in situ

observations. Lobatus gigas is now known to be a specialized herbivore

, as is the case in other Strombidae

, feeding on macroalgae (including red algae, such as species of Gracilaria

and Hypnea), seagrass

and unicellular algae, intermittently also feeding on algal detritus

. The green macroalga Batophora oerstedii is one of its preferred foods.

(Crepidula

spp.). The porcelain crab

, Porcellana sayana, is also known to be a commensal, and a small cardinal fish, known as the conch fish (Astrapogon stellatus), sometimes lives in the mantle of the conch for protection, bringing L. gigas no apparent benefit.

L. gigas is very often parasitized by protist

s of the phylum Apicomplexa

, which are common parasites of mollusks. Those coccidian parasites, which are spore-forming, single-celled microorganism

s, initially establish themselves in large vacuolated

cell

s of the hosts

digestive gland

, where they reproduce freely. The infestation may proceed to the secretory

cells of the same organ, and the entire life cycle of the parasite will likely occur within the same host and tissue.

L. gigas is a prey species for several carnivorous gastropod mollusks, including the apple murex Phyllonotus pomum, the horse conch Pleuroploca gigantea

L. gigas is a prey species for several carnivorous gastropod mollusks, including the apple murex Phyllonotus pomum, the horse conch Pleuroploca gigantea

, the lamp shell Turbinella angulata

, the moon snails Natica

spp. and Polinices

spp., the muricid

snail Murex margaritensis, the trumpet triton Charonia variegata

and the tulip snail Fasciolaria tulipa

. A variety of crustacean

s are also known predators of conchs, such as the blue crab Callinectes sapidus, the box crab Calappa gallus, the giant hermit crab Petrochirus diogenes

, the spiny lobster Panulirus argus

and several other species. The queen conch is also prey to echinoderm

s, such as the cushion star, Oreaster reticulatus

, and vertebrate

s, including fish

(such as the permit Trachinotus falcatus and the porcupine fish Diodon hystrix), loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and humans.

Conch meat has been eaten by humans for centuries, and has traditionally been an important part of the diet in many islands in the West Indies. It is consumed raw, marinated, minced or chopped in a wide variety of dishes, such as salad

Conch meat has been eaten by humans for centuries, and has traditionally been an important part of the diet in many islands in the West Indies. It is consumed raw, marinated, minced or chopped in a wide variety of dishes, such as salad

s, chowder

, fritter

s, soups, stew, pâté

s and other local recipes. In the Spanish-speaking regions, for example in the Dominican Republic

, Lobatus gigas meat is known as . Although the queen conch meat is used mainly for human consumption, it is also sometimes employed as fishing bait

(usually the foot is utilized for such purpose). L. gigas is among the most important fishery resources in the Caribbean: its harvest value was US$30 million in 1992, increasing to $60 million in 2003. The total annual harvest of meat of L. gigas ranged from 6,519,711 kg to 7,369,314 kg between 1993 and 1998, and later its production declined to 3,131,599 kg in 2001. Data about imports of queen conch meat into the United States shows a total of 1,832,000 kg in 1998, as compared to 387,000 kg in 2009, a drastic reduction of nearly 80%, twelve years later.

Queen conch shells were used by Native Americans

Queen conch shells were used by Native Americans

and Caribbean Indians in a wide variety of ways. The South Florida Indians (such as the Tequesta

), the Carib, the Arawak and Taíno

used conch shells to fabricate tools (such as knives

, axe heads and chisel

s), jewelry, cookware and also used them as blowing horn

s. Aztecs used the shell as part of jewelry mosaics like the double-headed serpent

. Brought by explorers, queen conch shells quickly became a popular asset in early modern

Europe. In the late 17th century they were widely used as decoration over fireplace mantels and English garden

s, among other places. In contemporary times, queen conch shells are mainly utilized in handicraft. Shells are made into cameos, bracelets and lamps, but have also been traditionally used as doorstop

s or decorations by families of seafaring men. The shell of the queen conch has been, and continues to be, popular as a decorative object, though its export is now regulated and restricted by the CITES agreement.

Very rarely (about 1 in 10,000 conchs), a conch pearl may be found within the mantle

of the animal. Though they occur in a range of colors corresponding to the colors of the interior of the shell, the pink conch pearls are considered to be the most desirable. These pearls are considered semi-precious, a popular tourist curio, and the most attractive among them have been used to create necklaces and earrings. A conch pearl is a non-nacreous pearl (formerly referred to by some sources as a 'calcareous concretion' – see the pearl article), which differs from most pearls sold as gemstones.

conchs can reproduce and thus build up a population. In many places where adult conchs have become rare due to overfishing, larger juveniles and subadult animals are taken by the fishermen before the snails have had a chance to mate and lay eggs.

On a number of islands, subadult conchs form the vast majority of the harvest. The abundance of Lobatus gigas is declining throughout the species' range as a result of overfishing

and poaching, and populations of the species in Honduras

, Haiti

and the Dominican Republic

, in particular, are currently being exploited at rates that may be unsustainable. In fact, trade from many Caribbean countries is known or suspected to be unsustainable, and illegal harvest, including fishing of the species in foreign waters and subsequent illegal international trade, is a common and widespread problem in the region. The Caribbean "International Queen Conch Initiative" is an attempt at a fisheries management scheme for this species.

The queen conch fishery is usually managed under the regulations of individual nations. In the United States all taking of queen conch is prohibited in Florida

and in adjacent Federal waters. No international regional fishery management organization exists in the whole Caribbean area, but in places such as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, queen conch is regulated under the auspices of the Caribbean Fishery Management Council (CFMC). In 1990, the Parties to the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region (Cartagena Convention) included queen conch in Annex II of its Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW Protocol) as a species that may be used on a rational and sustainable basis and that requires protective measures. Because of this recognition, in 1992 the United States proposed queen conch for listing in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES); this proposal was adopted, and queen conch became the first large-scale fisheries product to be regulated by CITES.

Although this species has been mentioned in CITES since 1985 and has been listed in Appendix II since 1992, it is only since 1995 that CITES has been reviewing the biological and trade status of the queen conch (Note: this species is known by the name Strombus gigas in CITES) under its "Significant Trade Review" process. Significant Trade Reviews are undertaken when there is concern about levels of trade in an Appendix II species. Based on the 2003 review, CITES recommended that all countries prohibit the importation of queen conch from Honduras, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, according to Standing Committee Recommendations. Queen conch meat continues to be available from many other Caribbean countries, including Jamaica and the Turks and Caicos Islands

(British West Indies), which have well-managed queen conch fisheries.

Common name

A common name of a taxon or organism is a name in general use within a community; it is often contrasted with the scientific name for the same organism...

known as the queen conch, is a species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

of large edible sea snail

Sea snail

Sea snail is a common name for those snails that normally live in saltwater, marine gastropod molluscs....

, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family of true conchs, the Strombidae

Strombidae

Strombidae, commonly known as the true conchs, is a taxonomic family of medium-sized to very large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Stromboidea....

. This species is one of the largest mollusks native to the Tropical Northwestern Atlantic, from Bermuda

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British overseas territory in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located off the east coast of the United States, its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, about to the west-northwest. It is about south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and northeast of Miami, Florida...

to Brazil, reaching up to 35.2 cm (13.9 in) in shell length.

The queen conch is herbivorous and lives in seagrass

Seagrass

Seagrasses are flowering plants from one of four plant families , all in the order Alismatales , which grow in marine, fully saline environments.-Ecology:...

beds, although the exact habitat varies during the different stages of its development. The adult animal has a very large, solid and heavy shell

Gastropod shell

The gastropod shell is a shell which is part of the body of a gastropod or snail, one kind of mollusc. The gastropod shell is an external skeleton or exoskeleton, which serves not only for muscle attachment, but also for protection from predators and from mechanical damage...

, with knob-like spines on the shoulder, a flared thick outer lip

Gastropod shell

The gastropod shell is a shell which is part of the body of a gastropod or snail, one kind of mollusc. The gastropod shell is an external skeleton or exoskeleton, which serves not only for muscle attachment, but also for protection from predators and from mechanical damage...

and a characteristic pink-colored aperture

Aperture (mollusc)

The aperture is an opening in certain kinds of mollusc shells: it is the main opening of the shell, where part of the body of the animal emerges for locomotion, feeding, etc....

(opening). The flared lip is completely absent in younger specimens. The external anatomy of the soft parts of L. gigas is similar to that of other snails in the same family: it has a long snout

Snout

The snout, or muzzle, is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw.-Terminology:The term "muzzle", used as a noun, can be ambiguous...

, two eyestalk

Eyestalk

In anatomy, an eyestalk is a protrusion that extends the eye away from the body, giving the eye a better field of view than if it were unextended. It is common in nature and in fiction....

s with well-developed eyes and additional sensory tentacles, a strong foot and a corneous

Corneous

Corneous is a biological and medical term meaning horny, in other words made out of a substance similar to that of horns and hooves in some mammals....

sickle

Sickle

A sickle is a hand-held agricultural tool with a variously curved blade typically used for harvesting grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock . Sickles have also been used as weapons, either in their original form or in various derivations.The diversity of sickles that...

-shaped operculum

Operculum (gastropod)

The operculum, meaning little lid, is a corneous or calcareous anatomical structure which exists in many groups of sea snails and freshwater snails, and also in a few groups of land snails...

.

The shell and soft parts of living Lobatus gigas serve as a home to several different kinds of commensal animals, including slipper snail

Crepidula

Crepidula, common name the "slipper limpets" or "slipper shells", is a genus of sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Calyptraeidae, the slipper snails and cup-and-saucer snails....

s, porcelain crab

Porcelain crab

Porcelain crabs are decapod crustaceans in the widespread family Porcellanidae, which superficially resemble true crabs. They are typically less than wide, and have flattened bodies as an adaptation for living in rock crevices...

s and cardinal fish. Its parasites include coccidia

Coccidia

Coccidia is a subclass of microscopic, spore-forming, single-celled obligate parasites belonging to the apicomplexan class Conoidasida. Coccidian parasites infect the intestinal tracts of animals, and are the largest group of apicomplexan protozoa....

ns. The queen conch is hunted and eaten by several species of large predatory sea snails, and also by starfish, crustacean

Crustacean

Crustaceans form a very large group of arthropods, usually treated as a subphylum, which includes such familiar animals as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill and barnacles. The 50,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at , to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span...

s and vertebrates (fish, sea turtle

Sea turtle

Sea turtles are marine reptiles that inhabit all of the world's oceans except the Arctic.-Distribution:...

s and humans). The meat of this sea snail is consumed by humans in a wide variety of dishes. The shell is sold as a souvenir

Souvenir

A souvenir , memento, keepsake or token of remembrance is an object a person acquires for the memories the owner associates with it. The term souvenir brings to mind the mass-produced kitsch that is the main commodity of souvenir and gift shops in many tourist traps around the world...

and used as a decorative object. Historically, Native American

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

s and indigenous Caribbean peoples used parts of the shell to create various tools.

International trade in queen conch is regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) agreement, in which it is listed as Strombus gigas. This species is not yet truly endangered in the Caribbean as a whole, but it is commercially threatened in numerous areas, largely due to extreme overfishing; the meat is an important food source for humans. The CITES regulations are designed to monitor and control the commercial export of the meat of this species as well as the shells (often sold to be used as decorative objects). Both of these trades were previously so prevalent that they represented serious threats to the survival of the species. However, the CITES Convention does not monitor or regulate any domestic use.

Taxonomy and naming

The queen conch was originally described from a shell in 1758 by the Swedish naturalistNaturalist

Naturalist may refer to:* Practitioner of natural history* Conservationist* Advocate of naturalism * Naturalist , autobiography-See also:* The American Naturalist, periodical* Naturalism...

and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus in his ground-breaking book . Linnaeus named the species Strombus gigas, and that remained the accepted name for over two hundred years. Linnaeus did not mention a specific locality for this species in his description, giving only "America" as the type locality. The specific name is the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

word , which means "giant", referring to the large size of this snail compared with almost all other gastropod mollusks. Strombus lucifer, which was considered to be a synonym much later, was also described by Linnaeus in Systema Naturae.

In the first half of the 20th century, the type material for the species was thought to have been lost; in other words, the shell on which Linnaeus based his original description and which would very likely have been in his own collection, was apparently missing, and without type material to formally define the species, this created a problem for taxonomists. To remedy this, in 1941 a neotype of this species was designated by the American malacologists William J. Clench

William J. Clench

William James Clench was an American malacologist, professor at Harvard University and curator of the mollusk collection in the malacology department of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard.Clench was born in Brooklyn, but was largely raised in Massachusetts. In 1913 he entered the...

and R. Tucker Abbott

R. Tucker Abbott

Robert Tucker Abbott was an American conchologist and malacologist . He was the author of more than 30 books on malacology, which have been translated into many languages....

. In this case, the neotype was not an actual shell or whole specimen

Specimen

A specimen is a portion/quantity of material for use in testing, examination, or study.BiologyA laboratory specimen is an individual animal, part of an animal, a plant, part of a plant, or a microorganism, used as a representative to study the properties of the whole population of that species or...

, but a figure from a book that was published in the 17th century, 23 years before Linnaeus was even born, the 1684 by the Italian scholar Filippo Buonanni. This was the first book published that was solely about seashell

Seashell

A seashell or sea shell, also known simply as a shell, is a hard, protective outer layer created by an animal that lives in the sea. The shell is part of the body of the animal. Empty seashells are often found washed up on beaches by beachcombers...

s. In 1953 however, the Swedish malacologist Nils Hjalmar Odhner

Nils Hjalmar Odhner

Nils Hjalmar Odhner was a Swedish zoologist who studied mollusks, a malacologist. During his lifetime he was professor of invertebrate zoology at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm...

searched the Linnaean Collection at Uppsala University

Uppsala University

Uppsala University is a research university in Uppsala, Sweden, and is the oldest university in Scandinavia, founded in 1477. It consistently ranks among the best universities in Northern Europe in international rankings and is generally considered one of the most prestigious institutions of...

and discovered the original shell upon which Linnaeus had based his description, thereby invalidating Clench and Abbott's neotype designation.

The family Strombidae

Strombidae

Strombidae, commonly known as the true conchs, is a taxonomic family of medium-sized to very large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Stromboidea....

has recently undergone an extensive taxonomic revision, and a few subgenera

Subgenus

In biology, a subgenus is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.In zoology, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the generic name and the specific epithet: e.g. the Tiger Cowry of the Indo-Pacific, Cypraea tigris Linnaeus, which...

, including Eustrombus

Eustrombus

Lobatus is a genus of very large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Strombidae, the true conchs. :Some of the species within this genus were previously placed in the genus Eustrombus.-Species:...

, were elevated to genus

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

level by some authors. Petuch (2004) and Petuch and Roberts (2007) recombined this species as Eustrombus gigas, and Landau et al. (2008) recombined it as Lobatus gigas.

Common names

As well as the English names "queen conch" and "pink conch", common names for this species in the languages spoken where it occurs include and in MexicoMexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, , , and in Venezuela

Venezuela

Venezuela , officially called the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela , is a tropical country on the northern coast of South America. It borders Colombia to the west, Guyana to the east, and Brazil to the south...

, and in the Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a nation on the island of La Hispaniola, part of the Greater Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean region. The western third of the island is occupied by the nation of Haiti, making Hispaniola one of two Caribbean islands that are shared by two countries...

.

Shell description

The adult shellGastropod shell

The gastropod shell is a shell which is part of the body of a gastropod or snail, one kind of mollusc. The gastropod shell is an external skeleton or exoskeleton, which serves not only for muscle attachment, but also for protection from predators and from mechanical damage...

of this species is usually 15–31 cm (6–12 in) in length, and the maximum reported size is 35.2 cm (13.9 in). The shell is very solid and heavy, with 9 to 11 whorls

Gastropod shell

The gastropod shell is a shell which is part of the body of a gastropod or snail, one kind of mollusc. The gastropod shell is an external skeleton or exoskeleton, which serves not only for muscle attachment, but also for protection from predators and from mechanical damage...

and a widely flaring and thickened outer lip. In the shells of adult snails, a structure called the stromboid notch

Stromboid notch

The stromboid notch is an anatomical feature which is found in the shell of one taxonomic family of medium sized to large sea snails, the conches....

is present on the edge of the lip. Although this notch is not as well developed in this species as it is in many other species in the same family, the shell feature is nonetheless visible in an adult dextral (normal right-handed) specimen, as a secondary anterior indentation in the lip of the shell, to the right of the siphonal canal

Siphonal canal

Some sea marine gastropods have a soft tubular anterior extension of the mantle called a siphon through which water is drawn into the mantle cavity and over the gill and which serves as a chemoreceptor to locate food. In many carnivorous snails, where the siphon is particularly long, the structure...

, assuming the shell is viewed ventrally. In life, the animal's left eyestalk protrudes through this notch.

The spire

Spire (mollusc)

A spire is a descriptive term for part of the coiled shell of mollusks. The word is a convenient aid in describing shells, but it does not refer to a very precise part of shell anatomy: the spire consists of all of the whorls except for the body whorl...

(a protruding part of the shell which includes all of the whorls with the exception of the largest and final whorl, known as the body whorl

Body whorl

Body whorl is part of the morphology of a coiled gastropod mollusk.- In gastropods :In gastropods, the body whorl, or last whorl, is the most recently-formed and largest whorl of a spiral or helical shell, terminating in the aperture...

) is usually higher (more elongated) in this species than it is in the shells of other strombid snails, such as the closely related and even larger goliath conch, Lobatus goliath, a species endemic to Brazil. In Lobatus gigas, the glossy finish or glaze around the aperture

Aperture (mollusc)

The aperture is an opening in certain kinds of mollusc shells: it is the main opening of the shell, where part of the body of the animal emerges for locomotion, feeding, etc....

of the adult shell is colored primarily in shades of pink. This pink glaze is usually pale, and may show a cream, peach or yellow coloration, but it can also sometimes be tinged with a deep magenta

Magenta

Magenta is a color evoked by light stronger in blue and red wavelengths than in yellowish-green wavelengths . In light experiments, magenta can be produced by removing the lime-green wavelengths from white light...

, shading almost to red. The periostracum

Periostracum

The periostracum is a thin organic coating or "skin" which is the outermost layer of the shell of many shelled animals, including mollusks and brachiopods. Among mollusks it is primarily seen in snails and clams, i.e. in bivalves and gastropods, but it is also found in cephalopods such as the...

, a layer of protein (conchiolin

Conchiolin

Conchiolin and perlucin are complex proteins which are secreted by a mollusc's outer epithelium ....

) which is the outermost part of the shell surface, is thin and a pale brown or tan color in this species.

Morphology (biology)

In biology, morphology is a branch of bioscience dealing with the study of the form and structure of organisms and their specific structural features....

of L. gigas is not solely determined by the animal's genes; environmental conditions such as geographic location, food supply, temperature and depth, and biological interactions such as exposure to predation, can greatly affect it. Juvenile conchs develop heavier shells when exposed to predators compared to those that are not exposed to predators. Conchs also develop wider and thicker shells with fewer but longer spines when they are living in deeper water.

The shells of very small juvenile queen conchs are strikingly different in appearance from those of the adults. Noticeable is the complete absence of a flared outer lip; juvenile shells have a simple sharp lip, which gives the shell a conical

Cone (geometry)

A cone is an n-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a base to a point called the apex or vertex. Formally, it is the solid figure formed by the locus of all straight line segments that join the apex to the base...

or biconic outline. In Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

, juvenile queen conchs are known as "rollers", because wave action very easily rolls their shells, whereas it is nearly impossible to roll the shell of an adult specimen, due to its weight and asymmetrical profile. Subadult shells have a flared lip which is however very thin; the flared outer lip of an adult shell constantly increases in thickness with age, until death.

Historic illustrations

(published in 1742 by the Italian physicianPhysician

A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

and malacologist Niccolò Gualtieri

Niccolò Gualtieri

Niccolò Gualtieri was an Italian doctor and malacologist. In 1742, he published Index Testarum Conchyliorum, quae adservantur in Museo Nicolai Gualtieri . Gualtieri was a professor at the University of Pisa...

) contains three illustrations showing the morphology of adult queen conch shells from different perspectives. The knobbed spire and the flaring outer lip, with its somewhat wing-like contour expanding out from the last whorl

Body whorl

Body whorl is part of the morphology of a coiled gastropod mollusk.- In gastropods :In gastropods, the body whorl, or last whorl, is the most recently-formed and largest whorl of a spiral or helical shell, terminating in the aperture...

, is a striking feature of these images. The shells are shown as if balancing on the edge of the lip and/or the apex; this was presumably done for artistic reasons as these shells cannot be balanced like this.

Considered as one of the most prized and sumptuous shell publications of the 19th century, a series of books titled (published by the French naturalist Jean-Charles Chenu

Jean-Charles Chenu

Jean-Charles Chenu was a French physician and naturalist. Chenu is the author of an Encyclopaedia of Natural History.-Bibliography:Natural history...

from 1842 to 1853), contains several illustrations of both adult and juvenile L. gigas shells, and one uncolored drawing depicting some of the animal's soft parts. Almost forty years later, a colored illustration from the Manual of Conchology (published in 1885 by the American malacologist George Washington Tryon

George Washington Tryon

George Washington Tryon, Jr. was an American malacologist who worked at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.- Biography :George Washington Tryon was the son of Edward K. Tryon and Adeline Savidt...

) shows a dorsal view of a small juvenile shell with its typical brown and white patterning.

|

|

|

|

Anatomy of the soft parts

Lobatus gigas has a long extensible snout

Snout

The snout, or muzzle, is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw.-Terminology:The term "muzzle", used as a noun, can be ambiguous...

with two eyestalks (also known as ommatophores) that originate from its base. The tip of each eyestalk contains a large, well-developed lens

Lens (anatomy)

The crystalline lens is a transparent, biconvex structure in the eye that, along with the cornea, helps to refract light to be focused on the retina. The lens, by changing shape, functions to change the focal distance of the eye so that it can focus on objects at various distances, thus allowing a...

eye, with a black pupil

Pupil

The pupil is a hole located in the center of the iris of the eye that allows light to enter the retina. It appears black because most of the light entering the pupil is absorbed by the tissues inside the eye. In humans the pupil is round, but other species, such as some cats, have slit pupils. In...

and a yellow iris

Iris (anatomy)

The iris is a thin, circular structure in the eye, responsible for controlling the diameter and size of the pupils and thus the amount of light reaching the retina. "Eye color" is the color of the iris, which can be green, blue, or brown. In some cases it can be hazel , grey, violet, or even pink...

(if amputated, the eyes can be completely regenerated

Regeneration (biology)

In biology, regeneration is the process of renewal, restoration, and growth that makes genomes, cells, organs, organisms, and ecosystems resilient to natural fluctuations or events that cause disturbance or damage. Every species is capable of regeneration, from bacteria to humans. At its most...

), and a small slightly posterior sensory tentacle. Inside the mouth of the animal is a radula

Radula

The radula is an anatomical structure that is used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared rather inaccurately to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food enters the esophagus...

(a tough ribbon covered in rows of microscopic teeth) of the taenioglossan type.

Both the snout and the eyestalks show dark spotting in the exposed areas. The mantle

Mantle (mollusc)

The mantle is a significant part of the anatomy of molluscs: it is the dorsal body wall which covers the visceral mass and usually protrudes in the form of flaps well beyond the visceral mass itself.In many, but by no means all, species of molluscs, the epidermis of the mantle secretes...

is darkly colored in the anterior region, fading to light gray at the posterior end, while the mantle collar is commonly orange, and the siphon is also orange or yellow.

When the soft parts of the animal are removed from the shell, several organs are distinguishable externally, including the kidney, the nephiridial

Nephridium

A Nephridium is an invertebrate organ which occurs in pairs and function similar to kidneys. Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. They are present in many different invertebrate lines. There are two basic types, metanephridia and protonephridia, but there are other...

gland, the pericardium

Pericardium

The pericardium is a double-walled sac that contains the heart and the roots of the great vessels.-Layers:...

, the genital glands

Reproductive system of gastropods

The reproductive system of gastropods varies greatly from one group to another within this very large and diverse taxonomic class of animals...

, stomach, style sac, and the digestive gland. In adult males, the penis is also visible.

Suprapedal gland

The suprapedal gland or mucous pedal gland is an anatomical feature found in some snails and slugs. It is a gland located inside the front end of the foot of gastropods.The term suprapedal means "above the foot"....

. Attached to the posterior end of the foot for about one third of its length is the dark brown, corneous

Corneous

Corneous is a biological and medical term meaning horny, in other words made out of a substance similar to that of horns and hooves in some mammals....

, sickle

Sickle

A sickle is a hand-held agricultural tool with a variously curved blade typically used for harvesting grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock . Sickles have also been used as weapons, either in their original form or in various derivations.The diversity of sickles that...

-shaped operculum

Operculum (gastropod)

The operculum, meaning little lid, is a corneous or calcareous anatomical structure which exists in many groups of sea snails and freshwater snails, and also in a few groups of land snails...

, which is reinforced by a distinct central rib. The base of the posterior two-thirds of the animal's foot is rounded; only the anterior third of the foot is applied to the substrate during locomotion.

The columella, the central pillar within the shell, serves as the attachment point for the white collumellar muscle. Contraction of this large strong muscle allows all of the soft parts of the animal to withdraw into the shell in response to undesirable stimuli.

Distribution

Lobatus gigas is native to the tropical Western Atlantic coasts of North and Central America. It lives in the greater Caribbean tropical zone.Although the species undoubtedly occurs in more individual places than are listed here, the countries, regions, and islands where this species has been recorded within the scientific literature

Scientific literature

Scientific literature comprises scientific publications that report original empirical and theoretical work in the natural and social sciences, and within a scientific field is often abbreviated as the literature. Academic publishing is the process of placing the results of one's research into the...

as occurring are, in alphabetical order:

Aruba

Aruba is a 33 km-long island of the Lesser Antilles in the southern Caribbean Sea, located 27 km north of the coast of Venezuela and 130 km east of Guajira Peninsula...

, of the Netherlands Antilles

Netherlands Antilles

The Netherlands Antilles , also referred to informally as the Dutch Antilles, was an autonomous Caribbean country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, consisting of two groups of islands in the Lesser Antilles: Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao , in Leeward Antilles just off the Venezuelan coast; and Sint...

; Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

; all of the islands and cays of the Bahamas; Belize

Belize

Belize is a constitutional monarchy and the northernmost country in Central America. Belize has a diverse society, comprising many cultures and languages. Even though Kriol and Spanish are spoken among the population, Belize is the only country in Central America where English is the official...

; Bermuda

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British overseas territory in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located off the east coast of the United States, its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, about to the west-northwest. It is about south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and northeast of Miami, Florida...

; North and northeastern regions of Brazil (though this is contested by some authors); Old Providence Island in Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

; Costa Rica

Costa Rica

Costa Rica , officially the Republic of Costa Rica is a multilingual, multiethnic and multicultural country in Central America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, Panama to the southeast, the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Caribbean Sea to the east....

; the Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a nation on the island of La Hispaniola, part of the Greater Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean region. The western third of the island is occupied by the nation of Haiti, making Hispaniola one of two Caribbean islands that are shared by two countries...

; Panama

Panama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

; Swan Islands

Swan Islands, Honduras

The Swan Islands, or Islas Santanilla, are a chain of three islands located in the northwestern Caribbean Sea, approximately ninety miles off the coastline of Honduras, with a land area of .-Detailed location and features:...

in Honduras

Honduras

Honduras is a republic in Central America. It was previously known as Spanish Honduras to differentiate it from British Honduras, which became the modern-day state of Belize...

; Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

; Martinique

Martinique

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, with a land area of . Like Guadeloupe, it is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. To the northwest lies Dominica, to the south St Lucia, and to the southeast Barbados...

; Alacran Reef, Campeche

Campeche

Campeche is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. Located in Southeast Mexico, it is bordered by the states of Yucatán to the north east, Quintana Roo to the east, and Tabasco to the south west...

, Cayos Arcas

Cayos Arcas

The Cayos Arcas is a chain of three tiny sand cays and an accompanying reef system in the Gulf of Mexico. It is located approximately 130 kilometers from the mainland, west of Campeche. Their aggregate land area is 22.8 hectares...

and Quintana Roo

Quintana Roo

Quintana Roo officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Quintana Roo is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 10 municipalities and its capital city is Chetumal....

, in Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

; Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

; Saint Barthélemy

Saint Barthélemy

Saint Barthélemy , officially the Territorial collectivity of Saint Barthélemy , is an overseas collectivity of France. Often abbreviated to Saint-Barth in French, or St. Barts in English, the indigenous people called the island Ouanalao...

; Mustique

Mustique

Mustique is a small private island in the West Indies. The island is one of a group of islands called the Grenadines, most of which form part of the country of St Vincent and the Grenadines....

and Grenada

Grenada

Grenada is an island country and Commonwealth Realm consisting of the island of Grenada and six smaller islands at the southern end of the Grenadines in the southeastern Caribbean Sea...

in the Grenadines; Pinar del Río

Pinar del Río

Pinar del Río is a city in Cuba. It is the capital of Pinar del Río Province.Inhabitants of the area are called Pinareños.Neighborhoods in the city include La Conchita, La Coloma, Briones Montoto and Las Ovas.-History:...

, North Havana Province

La Habana Province

Havana Province was one of the provinces of Cuba, prior to being divided into two new provinces of Artemisa and Mayabeque on January 1, 2011. It had 711,066 people in the 2002 census. The largest city was Artemisa .-Geography:...

, North Matanzas

Matanzas

Matanzas is the capital of the Cuban province of Matanzas. It is famed for its poets, culture, and Afro-Cuban folklore.It is located on the northern shore of the island of Cuba, on the Bay of Matanzas , east of the capital Havana and west of the resort town of Varadero.Matanzas is called the...

, Villa Clara

Villa Clara Province

Villa Clara is one of the provinces of Cuba. It is located in the central region of the island bordering with the Atlantic at north, Matanzas Province by west, Sancti Spiritus by east, and Cienfuegos on the South. Villa Clara shares with Cienfuegos and Sancti Spiritus on the south the Escambray...

, Cienfuegos

Cienfuegos

Cienfuegos is a city on the southern coast of Cuba, capital of Cienfuegos Province. It is located about from Havana, and has a population of 150,000. The city is dubbed La Perla del Sur...

, Holguín

Holguín

Holguín is a municipality and city, the capital of the Cuban Province of Holguín. It also includes a tourist area, offering beach resorts in the outskirts of the region.-History:...

, Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city of Cuba and capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province in the south-eastern area of the island, some south-east of the Cuban capital of Havana....

and Guantánamo, in the Turks and Caicos Islands and Cuba; South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

, Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

, including East Florida, West Florida, the Florida Keys and the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, in the United States; Carabobo

Carabobo

Carabobo State is one of the 23 states of Venezuela, located in the north of the country, about two hours by car from Caracas. The capital city of this state is Valencia, which is also the country's main industrial center. The state's area is 4,650 km² and had an estimated population of...

, Falcon, Gulf of Venezuela, Los Roques archipelago

Los Roques Archipelago

The Los Roques islands are a federal dependency of Venezuela, consisting of about 350 islands, cays or islets. The archipelago is located 80 miles directly north of the port of La Guaira, and is a 40-minute flight, has a total area of 40.61 square kilometres.Being almost an untouched coral reef,...

, Los Testigos Islands

Los Testigos Islands

Los Testigos Islands are a group of islands in the southeastern Caribbean Sea. They are a part of the Dependencias Federales of Venezuela.-Geography:...

and Sucre

Sucre

Sucre, also known historically as Charcas, La Plata and Chuquisaca is the constitutional capital of Bolivia and the capital of the department of Chuquisaca. Located in the south-central part of the country, Sucre lies at an elevation of 2750m...

in Venezuela; St. Croix in the Virgin Islands

Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands are the western island group of the Leeward Islands, which are the northern part of the Lesser Antilles, which form the border between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean...

.

Behavior

Lobatus gigas has an unusual means of locomotionAnimal locomotion

Animal locomotion, which is the act of self-propulsion by an animal, has many manifestations, including running, swimming, jumping and flying. Animals move for a variety of reasons, such as to find food, a mate, or a suitable microhabitat, and to escape predators...

, which was described in 1922 by the American zoologist George Howard Parker

George Howard Parker

George Howard Parker was an American zoologist. He was Professor of Zoology at Harvard University and Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences...

(1864–1955). The animal first fixes the posterior end of the foot by thrusting the point of the sickle-shaped operculum into the substrate, then it extends the foot in a forward direction, lifting and throwing the shell forward in a so-called leaping motion. This way of moving is considered to resemble that of pole vaulting, making L. gigas a good climber even of vertical concrete surfaces. This odd leaping form of locomotion may also help prevent predators from following the snail's chemical traces, which would otherwise be a continuous trail on the substrate

Substrate (biology)

In biology a substrate is the surface a plant or animal lives upon and grows on. A substrate can include biotic or abiotic materials and animals. For example, encrusting algae that lives on a rock can be substrate for another animal that lives on top of the algae. See also substrate .-External...

.

Ecology

Habitat

Lobatus gigas lives at depths from 0.3 m to 18 m or to 25 m. It lives in seagrassSeagrass

Seagrasses are flowering plants from one of four plant families , all in the order Alismatales , which grow in marine, fully saline environments.-Ecology:...

meadows and on sandy substrate

Substrate (biology)

In biology a substrate is the surface a plant or animal lives upon and grows on. A substrate can include biotic or abiotic materials and animals. For example, encrusting algae that lives on a rock can be substrate for another animal that lives on top of the algae. See also substrate .-External...

, usually in association with turtle grass (species of the genus Thalassia

Thalassia (genus)

Thalassia is a marine seagrass genus comprising 2 species.-Species:T. testudinum Banks ex König is the type specimen. It is native to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean with specimens found as far east as Bermuda. It has a fossil record in the Gulf to the Middle Eocene.T. hemprichii ...

, namely Thalassia testudinum and also Syringodium

Syringodium

Syringodium is a genus in the family Cymodoceaceae. It includes just two species, distributed in warm oceans....

sp.) and manatee grass (Cymodocea

Cymodocea

Cymodocea is a genus in the family Cymodoceaceae. It includes four species of sea grass distributed in warm oceans....

sp.). Juvenile individuals are found in shallow, inshore seagrass meadows, which are different from the deeper algal plains and seagrass meadows where adult individuals live.

The critical nursery habitats

Nursery habitats

In marine environments, a nursery habitat is a subset of all habitats where juveniles of a species occur, having a greater level of productivity per unit area than other juvenile habitats . Mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass are typical nursery habitats for a range of marine species...

for juvenile individuals are defined by a series of combined factors, both habitat characteristics (such as tidal circulation

Tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the moon and the sun and the rotation of the Earth....

) and ecological processes (such as macroalgal production), which together provide high rates of both recruitment

Recruitment (biology)

In biology, recruitment occurs when juvenile organisms survive to be added to a population. The term is generally used to refer to a stage whereby the organisms are settled and able to be detected by an observer....

and survival. Lobatus gigas is typically found in distinct aggregates, which may contain several thousand individuals.

Life cycle

Lobatus gigas is gonochoristicGonochorism

In biology, gonochorism or unisexualism describes sexually reproducing species in which individuals have just one of at least two distinct sexes. The term is most often used with animals . The sex of an individual may change during its lifetime, this can for example be found in parrotfish...

, which means each individual snail is either distinctly male or distinctly female. Females are usually larger than males in natural populations, with both sexes existing in similar proportion. After internal fertilization

Internal fertilization

In mammals, internal fertilization is done through copulation, which involves the insertion of the penis into the vagina. Some other higher vertebrate animals reproduce internally, but their fertilization is cloacal.The union of spermatozoa of the parent organism. At some point, the growing egg or...

, the females lay eggs in gelatinous strings, which can be as long as 75 feet (or about 23 m). These are layered on patches of bare sand or seagrass. The sticky surface of these long egg strings allows them to coil and agglutinate, mixing with the surrounding sand to form compact egg masses, the shape of which is defined by the anterior portion of the outer lip of the female's shell while they are layered. Each one of the egg masses may have been fertilized by multiple males. The number of eggs per egg mass may vary greatly depending on environmental conditions, such as food limitation and temperature. Commonly, females produce an average of 8–9 egg masses per season, each containing 180,000–460,000 eggs, but numbers can be as high as 750,000 eggs per egg mass depending upon the conditions. Lobatus gigas females may spawn multiple times during the reproductive season, which lasts from March to October, with activity peaks occurring from July to September.

After hatching, the emerging two-lobed veliger

Veliger

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of marine and freshwater gastropod molluscs, as well as most bivalve mollusks.- Description :...

(a larval form common to various marine and fresh-water gastropod and bivalve mollusks) spend several days developing in the plankton

Plankton

Plankton are any drifting organisms that inhabit the pelagic zone of oceans, seas, or bodies of fresh water. That is, plankton are defined by their ecological niche rather than phylogenetic or taxonomic classification...

, feeding primarily on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton are the autotrophic component of the plankton community. The name comes from the Greek words φυτόν , meaning "plant", and πλαγκτός , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter". Most phytoplankton are too small to be individually seen with the unaided eye...

. Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops after birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation...

occurs in about 16–40 days from the hatching, when the fully grown protoconch

Protoconch

A protoconch is an embryonic or larval shell of some classes of molluscs, e.g., the initial chamber of an ammonite or the larval shell of a gastropod...

(embryonic shell) is about 1.2 mm high. After the metamorphosis, Lobatus gigas individuals spend the rest of their lives in the benthic zone

Benthic zone

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean or a lake, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. Organisms living in this zone are called benthos. They generally live in close relationship with the substrate bottom; many such...

(on or in the sediment surface), usually remaining buried during their first year of life.

The queen conch is known to reach sexual maturity at approximately 3 to 4 years of age, reaching a shell length of nearly 180 mm and weighing up to 5 pounds. Individuals may usually live up to 7 years, though in deeper waters their lifespan may reach 20–30 years and maximum lifetime estimates reach 40 years. It is believed that the mortality rate

Mortality rate

Mortality rate is a measure of the number of deaths in a population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit time...

tends to be lower in matured conchs due to their thickened shell, but it could be substantially higher for juveniles. Estimates have demonstrated that the mortality rate of L. gigas decreases as the animal size increases, and can also vary due to habitat, season and other factors.

Feeding habits

Strombid gastropods were widely accepted as carnivoreCarnivore

A carnivore meaning 'meat eater' is an organism that derives its energy and nutrient requirements from a diet consisting mainly or exclusively of animal tissue, whether through predation or scavenging...

s by several authors in the 19th century, a conception that persisted until the first half of the 20th century. This erroneous idea probably originated in the writings of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de la Marck , often known simply as Lamarck, was a French naturalist...

, who classified strombids alongside other supposedly carnivorous snails, and this idea was subsequently repeated by other authors. The claims of these authors, however, were not supported by any in situ

In situ

In situ is a Latin phrase which translated literally as 'In position'. It is used in many different contexts.-Aerospace:In the aerospace industry, equipment on board aircraft must be tested in situ, or in place, to confirm everything functions properly as a system. Individually, each piece may...

observations. Lobatus gigas is now known to be a specialized herbivore

Herbivore

Herbivores are organisms that are anatomically and physiologically adapted to eat plant-based foods. Herbivory is a form of consumption in which an organism principally eats autotrophs such as plants, algae and photosynthesizing bacteria. More generally, organisms that feed on autotrophs in...

, as is the case in other Strombidae

Strombidae

Strombidae, commonly known as the true conchs, is a taxonomic family of medium-sized to very large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Stromboidea....

, feeding on macroalgae (including red algae, such as species of Gracilaria

Gracilaria

Gracilaria is a genus of red algae notable for its economic importance as an agarophyte, as well as its use as a food for humans and various species of shellfish...

and Hypnea), seagrass

Seagrass

Seagrasses are flowering plants from one of four plant families , all in the order Alismatales , which grow in marine, fully saline environments.-Ecology:...

and unicellular algae, intermittently also feeding on algal detritus

Detritus

Detritus is a biological term used to describe dead or waste organic material.Detritus may also refer to:* Detritus , a geological term used to describe the particles of rock produced by weathering...

. The green macroalga Batophora oerstedii is one of its preferred foods.

Interspecific relationships

A few different animals may establish a commensal interaction with L. gigas, which means both the organisms maintain a relationship where one individual benefits (the commensal) but the other obtains no advantage (in this case, the queen conch). Some commensals of this species are also mollusks, mainly slipper shellsCalyptraeidae

Calyptraeidae, common name the slipper snails or slipper limpets, cup-and-saucer snails, and Chinese hat snails are a family of small to medium-sized marine prosobranch gastropods...

(Crepidula

Crepidula

Crepidula, common name the "slipper limpets" or "slipper shells", is a genus of sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Calyptraeidae, the slipper snails and cup-and-saucer snails....

spp.). The porcelain crab

Porcelain crab

Porcelain crabs are decapod crustaceans in the widespread family Porcellanidae, which superficially resemble true crabs. They are typically less than wide, and have flattened bodies as an adaptation for living in rock crevices...

, Porcellana sayana, is also known to be a commensal, and a small cardinal fish, known as the conch fish (Astrapogon stellatus), sometimes lives in the mantle of the conch for protection, bringing L. gigas no apparent benefit.

L. gigas is very often parasitized by protist

Protist

Protists are a diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms. Historically, protists were treated as the kingdom Protista, which includes mostly unicellular organisms that do not fit into the other kingdoms, but this group is contested in modern taxonomy...

s of the phylum Apicomplexa

Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa are a large group of protists, most of which possess a unique organelle called apicoplast and an apical complex structure involved in penetrating a host's cell. They are unicellular, spore-forming, and exclusively parasites of animals. Motile structures such as flagella or...

, which are common parasites of mollusks. Those coccidian parasites, which are spore-forming, single-celled microorganism

Microorganism

A microorganism or microbe is a microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters, or no cell at all...

s, initially establish themselves in large vacuolated

Vacuole

A vacuole is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in all plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic molecules including enzymes in solution, though in certain...

cell

Cell (biology)

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all known living organisms. It is the smallest unit of life that is classified as a living thing, and is often called the building block of life. The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing embryos....

s of the hosts

Host (biology)