The Lizard

Encyclopedia

Peninsula

A peninsula is a piece of land that is bordered by water on three sides but connected to mainland. In many Germanic and Celtic languages and also in Baltic, Slavic and Hungarian, peninsulas are called "half-islands"....

in south Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

. The most southerly point

Extreme points of the United Kingdom

This is a list of the extreme points of the United Kingdom: the points that are farther north, south, east or west than any other location. Traditionally the extent of the island of Great Britain has stretched "from Land's End to John o' Groats" .This article does not include references to the...

of the British

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

mainland is near Lizard Point

Lizard Point, Cornwall

Lizard Point in Cornwall is at the southern tip of the Lizard Peninsula. It is situated half-a-mile south of Lizard village in the civil parish of Landewednack and approximately 11 miles southeast of Helston....

at .

Lizard

Lizard (village)

Lizard is a village on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately ten miles south of Helston, and is Britain's most southerly settlement....

village, the most southerly village on the British mainland, is in Landewednack

Landewednack

Landewednack is a civil parish and a hamlet in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hamlet is situated approximately ten miles south of Helston.Landewednack is the most southerly parish on the British mainland...

, the most southerly civil parish.

The peninsula measures approximately 14 miles (22.5 km) x 14 miles (22.5 km). It is situated southwest of Falmouth

Falmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth is a town, civil parish and port on the River Fal on the south coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a total resident population of 21,635.Falmouth is the terminus of the A39, which begins some 200 miles away in Bath, Somerset....

ten miles (16 km) east of Penzance

Penzance

Penzance is a town, civil parish, and port in Cornwall, England, in the United Kingdom. It is the most westerly major town in Cornwall and is approximately 75 miles west of Plymouth and 300 miles west-southwest of London...

.

The name "Lizard" is most probably a corruption of the Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

name "Lys Ardh", meaning "high court"; it is purely coincidental that much of the peninsula is composed of a rock called serpentinite

Serpentinite

Serpentinite is a rock composed of one or more serpentine group minerals. Minerals in this group are formed by serpentinization, a hydration and metamorphic transformation of ultramafic rock from the Earth's mantle...

. The Lizard peninsula's original name may have been the Celtic

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

name "Predannack" ("British one") as during the Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

(Pytheas

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia or Massilia , was a Greek geographer and explorer from the Greek colony, Massalia . He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe at about 325 BC. He travelled around and visited a considerable part of Great Britain...

c. 325 BC) and Roman period, Britain was known as Pretannike (in Greek) and as Albion

Albion

Albion is the oldest known name of the island of Great Britain. Today, it is still sometimes used poetically to refer to the island or England in particular. It is also the basis of the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland, Alba...

(and Britons the "Pretani").

The Lizard's coast is particularly hazardous to shipping and the seaways round the peninsula were historically known as the "Graveyard of Ships" (see below). The Lizard Lighthouse

Lizard Lighthouse

The Lizard Lighthouse is a lighthouse in Lizard Point in Cornwall, United Kingdom, built in 1752. A light was first exhibited from that point in 1619, but demolished in 1630. Trinity House took responsibility for the station in 1771...

was built at Lizard Point

Lizard Point, Cornwall

Lizard Point in Cornwall is at the southern tip of the Lizard Peninsula. It is situated half-a-mile south of Lizard village in the civil parish of Landewednack and approximately 11 miles southeast of Helston....

in 1752 and the RNLI

Royal National Lifeboat Institution

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution is a charity that saves lives at sea around the coasts of Great Britain, Ireland, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, as well as on selected inland waterways....

operates The Lizard lifeboat station

The Lizard lifeboat station

The Lizard Lifeboat Station is a lifeboat station operated by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution . It is located at Kilcobben Cove on The Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom...

.

General

There is evidence of early habitation with several burial mounds and stones. Part of the peninsula is known as the MeneageMeneage

The Meneage is a district in west Cornwall, United Kingdom. The nearest large towns are Falmouth and Penryn....

(land of the monks). There are several towns and villages on the peninsula, some of which are covered below.

Helston

Helston

Helston is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated at the northern end of the Lizard Peninsula approximately 12 miles east of Penzance and nine miles southwest of Falmouth. Helston is the most southerly town in the UK and is around further south than...

once headed the estuary of the River Cober

River Cober

The River Cober is a short river in west Cornwall, United Kingdom. It rises near Porkellis Moor in the former Kerrier District and runs to the west of the town of Helston before entering the largest natural lake in Cornwall – Loe Pool. The water is impounded by the natural barrier, Loe Bar, and...

, before it was cut off from the sea by Loe Bar in the 13th century. It was a small port which exported tin

Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

and copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

. Helston was certainly in existence in the sixth century. The name comes from the Cornish "hen lis" or "old court" and "ton" added later to denote a Saxon manor; the Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

refers to it as Henliston (which survives as the name of a road in the town). It was granted its charter by King John

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

in 1201. It was here that tin ingots were weighed to determine the duty due to the Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in the peerage of England.The present Duke of Cornwall is The Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Queen Elizabeth II, the reigning British monarch .-History:...

when a number of stannary towns were authorised by royal decree.

By the 14th century, a hamlet of fishermen's dwellings had established itself around the cove at Porthleven

Porthleven

Porthleven is a town, civil parish and fishing port in Cornwall, United Kingdom, near Helston. It is the most southerly port on the island of Great Britain and was originally developed as a harbour of refuge, when this part of the Cornish coastline was recognised as a black spot for wrecks in days...

, named from the old Cornish "porth" (harbour) and "leven" (level or smooth). It grew with miners and farmworkers; and building of a harbour began in 1811. In 1855 the harbour was deepened, and a boatbuilding industry began, lasting until recently. The port imported coal, limestone and timber, and exported tin, copper and china clay. The harbour also heralded the start of Porthleven's golden days of pilchard fishing.

Mullion

Mullion, Cornwall

Mullion is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Lizard Peninsula approximately five miles south of Helston....

has the 15th century church of St Mellanus, and the Old Inn from the 16th century. The harbour was completed in 1895 and financed by Lord Robartes of Lanhydrock as a recompense to the fishermen for several disastrous pilchard seasons.

The small church of St Peter in Coverack

Coverack

Coverack is a coastal village and fishing port in Cornwall, England, UK. It is situated on the east side of the Lizard peninsula approximately nine miles south of Falmouth....

, built in 1885 for £500, has a serpentinite pulpit.

The Great Western Railway

Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway was a British railway company that linked London with the south-west and west of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament in 1835 and ran its first trains in 1838...

operated a road motor

GWR road motor services

The Great Western Railway road motor services operated from 1903 to 1933, both as a feeder to their train services, and as a cheaper alternative to building new railways in rural areas...

service to The Lizard from Helston railway station

Helston railway station

Helston railway station was the terminus of the Helston Railway in Cornwall, in England . It was later operated by the Great Western Railway but has since been closed....

. Commencing on 17 August 1903, it was the first successful British railway-run bus service and was initially provided as a cheaper alternative to a proposed light railway

Light railway

Light railway refers to a railway built at lower costs and to lower standards than typical "heavy rail". This usually means the railway uses lighter weight track, and is more steeply graded and tightly curved to avoid civil engineering costs...

.

In 1999, the Solar eclipse of August 11, 1999 departed the UK mainland from the Lizard.

Nautical

The Lizard has been the site of many maritime disasters. It forms a natural obstacle to entry and exit of FalmouthFalmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth is a town, civil parish and port on the River Fal on the south coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a total resident population of 21,635.Falmouth is the terminus of the A39, which begins some 200 miles away in Bath, Somerset....

and its naturally deep estuary.

At Lizard Point stands the Lizard Lighthouse

Lizard Lighthouse

The Lizard Lighthouse is a lighthouse in Lizard Point in Cornwall, United Kingdom, built in 1752. A light was first exhibited from that point in 1619, but demolished in 1630. Trinity House took responsibility for the station in 1771...

. In fact, the light was erected by Sir John Killigrew by his own expense: It was built at the cost of "20 nobles a year" for 30 years, but it caused an uproar over the following years, as King James I considered charging vessels to pass. This caused so many problems that the lighthouse was demolished, but was successfully rebuilt in 1751 by order of Thomas Fonnereau

Thomas Fonnereau

Thomas Fonnereau was a British businessman and politician, the eldest son of the merchant Claude Fonnereau....

and remains almost unchanged today. Further east lie The Manacles

The Manacles

The Manacles are a set of treacherous rocks off The Lizard peninsula in Cornwall close to Porthoustock, which is a popular spot for diving due to the shipwrecks around them. The name derives from the Cornish for 'church stone', the top of St Keverne church being visible from the area.The rocks...

, near Porthoustock

Porthoustock

Porthoustock is a hamlet near St Keverne in Cornwall, United Kingdom, on the east coast of Lizard Peninsula. Aggregates are quarried nearby and Porthoustock beach is dominated by a large concrete stone mill. The mill was once used to crush stone but is now disused. Container ships of up to 82m can...

: 1.5 square miles (4 km²) of jagged rocks just beneath the waves.

- In 1721 the Royal Anne Galley, an oared frigate, was wrecked at Lizard Point. Of a crew of 185 only three survived; lost was Lord Belhaven who was en voyage to take up the Governorship of BarbadosBarbadosBarbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

. - A 44 gun frigate, HMS AnsonHMS Anson (1781)HMS Anson was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Plymouth on 4 September 1781 by Georgina, Duchess of Devonshire.-History:...

, was wrecked at Loe Bar in 1807. Although it wrecked close to shore, many lost their lives in the storm. This inspired Henry TrengrouseHenry TrengrouseHenry Trengrouse inventor of the ‘Rocket’ life-saving apparatus, was born at Helston, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, on 18 March 1772....

to invent the rocket fired line, later to become the Breeches buoyBreeches buoyA breeches buoy is a crude rope-based rescue device used to extract people from wrecked vessels, or to transfer people from one location to another in situations of danger. The device resembles a round emergency personal flotation device with a leg harness attached...

. - The transport ship Dispatch ran aground on the Manacles in 1809 on its return from the Peninsular WarPeninsular WarThe Peninsular War was a war between France and the allied powers of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when French and Spanish armies crossed Spain and invaded Portugal in 1807. Then, in 1808, France turned on its...

, losing 104 men from the 7th Hussars. The following day, with local villagers still attempting a rescue, the Cruizer class brig-sloopCruizer class brig-sloopThe Cruizer class was an 18-gun class of brig-sloops of the Royal Navy. Brig-sloops were the same as ship-sloops except for their rigging...

HMS PrimroseHMS Primrose (1807)HMS Primrose was a Royal Navy Cruizer class brig-sloop built by Thomas Nickells , at Fowey and launched in 1807. She was commissioned in November 1807 under Commander James Mein, who sailed her to the coast of Spain....

hit the northern end of these rocks. The only survivor of its 126 officers, men and boys was a drummer boy. - The SS MoheganSS MoheganThe SS Mohegan was a steamer which sank off the coast of the Lizard Peninsula, Cornwall. She hit The Manacles on 14 October 1898.-Design and construction:...

, a 7,000 tonne passenger liner, also hit the Manacles in 1898 with the loss of 106 lives. - The American passenger liner, the Paris, was stranded on the Manacles in 1899, with no loss of life.

The biggest rescue in the RNLI's history was 17 March 1907 when the 12,000 tonne liner SS Suevic

SS Suevic

The SS Suevic was a steamship built by Harland and Wolff in Belfast for the White Star Line. Suevic was the fifth and last of the "Jubilee Class" ocean liners, built specifically to service the Liverpool-Cape Town-Sydney route. In 1907 she was shipwrecked off the south coast of England, but in the...

hit the Maenheere Reef near Lizard Point

Lizard Point, Cornwall

Lizard Point in Cornwall is at the southern tip of the Lizard Peninsula. It is situated half-a-mile south of Lizard village in the civil parish of Landewednack and approximately 11 miles southeast of Helston....

in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

. In a strong gale and dense fog RNLI lifeboat volunteers rescued 456 passengers, including 70 babies. Crews from the Lizard, Cadgwith

Cadgwith

Cadgwith is a village and fishing port in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Lizard Peninsula between The Lizard and Coverack.-History:...

, Coverack

Coverack

Coverack is a coastal village and fishing port in Cornwall, England, UK. It is situated on the east side of the Lizard peninsula approximately nine miles south of Falmouth....

and Porthleven

Porthleven

Porthleven is a town, civil parish and fishing port in Cornwall, United Kingdom, near Helston. It is the most southerly port on the island of Great Britain and was originally developed as a harbour of refuge, when this part of the Cornish coastline was recognised as a black spot for wrecks in days...

rowed out repeatedly for 16 hours to rescue all of the people on board. Six silver RNLI medals were later awarded, two to Suevic crew members.

The Battle at the Lizard, a naval battle, took place off The Lizard on 21 October 1707.

Smuggling was a regular, and often necessary, way of life in these parts, despite the efforts of coastguards or "Preventive men". In 1801, the King's Pardon was offered to any smuggler giving information on the Mullion musket men involved in a gunfight with the crew of HM Gun Vessel Hecate.

Aviation

RAF Predannack Down (see Predannack AirfieldPredannack Airfield

Predannack Airfield is situated near Mullion on Cornwall's Lizard Peninsula in the United Kingdom. The runways are operated by the Royal Navy and today it is used as a satellite airfield and relief landing ground for nearby RNAS Culdrose.-World War II:...

) was a Second World War airbase, from which Coastal Command squadrons flew anti-submarine sorties into the Bay of Biscay

Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Brest south to the Spanish border, and the northern coast of Spain west to Cape Ortegal, and is named in English after the province of Biscay, in the Spanish...

as well as convoy support in the western English Channel

English Channel

The English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

. The runways still exist and the site is used by a local gliding

Gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sport in which pilots fly unpowered aircraft known as gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to remain airborne. The word soaring is also used for the sport.Gliding as a sport began in the 1920s...

club and as an emergency/relief base for RNAS Culdrose (HMS Seahawk).

RNAS Culdrose is Europe's largest helicopter

Helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by one or more engine-driven rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forwards, backwards, and laterally...

base, and currently hosts the Training and Occupational Conversion Unit operating the EH101 "Merlin" helicopter. It is also the home base for Merlin Squadrons embarked upon Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

warships, the Westland Sea King

Westland Sea King

The Westland WS-61 Sea King is a British licence-built version of the American Sikorsky S-61 helicopter of the same name, built by Westland Helicopters. The aircraft differs considerably from the American version, with Rolls-Royce Gnome engines , British made anti-submarine warfare systems and a...

AEW variant helicopter, a Search And Rescue (Sea King, again) helicopter flight, and some BAe Hawk

BAE Hawk

The BAE Systems Hawk is a British single-engine, advanced jet trainer aircraft. It first flew in 1974 as the Hawker Siddeley Hawk. The Hawk is used by the Royal Air Force, and other air forces, as either a trainer or a low-cost combat aircraft...

T.1 trainer jets used for training purposes by the Royal Navy. The base also operates some other types of fixed wing aircraft for calibration and other training purposes. As befits the base's name, a non-flying example of a Hawker Sea Hawk

Hawker Sea Hawk

The Hawker Sea Hawk was a British single-seat jet fighter of the Fleet Air Arm , the air branch of the Royal Navy , built by Hawker Aircraft and its sister company, Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. Although its origins stemmed from earlier Hawker piston-engined fighters, the Sea Hawk became the...

forms the main gate guardian static display. RNAS Culdrose is a major contributor to the economy of The Lizard area.

Political

The Lizard peninsula is in the St Ives parliamentary constituencySt Ives (UK Parliament constituency)

St. Ives is a county constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election.-History:...

(which comprises the whole of the former district of Penwith

Penwith

Penwith was a local government district in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, whose council was based in Penzance. The district covered all of the Penwith peninsula, the toe-like promontory of land at the western end of Cornwall and which included an area of land to the east that fell outside the...

and the southern part of the former district of Kerrier

Kerrier

Kerrier was a local government district in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It was the most southerly district in the United Kingdom, other than the Isles of Scilly. Its council was based in Camborne ....

). However, the parishes northeast of the Helford River are in Camborne and Redruth parliamentary constituency

To the north, The Lizard peninsula is bordered by the civil parishes of Breage

Breage

Breage, also known as Breaca, Briac, etc., is a saint venerated in Cornwall and southwestern Britain. According to her late hagiography, she was an Irish nun of the 5th or 6th century who founded a church in Cornwall...

, Porthleven

Porthleven

Porthleven is a town, civil parish and fishing port in Cornwall, United Kingdom, near Helston. It is the most southerly port on the island of Great Britain and was originally developed as a harbour of refuge, when this part of the Cornish coastline was recognised as a black spot for wrecks in days...

, Sithney

Sithney

Sithney is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is named for Saint Sithney, the patron saint of the parish church....

, Helston

Helston

Helston is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated at the northern end of the Lizard Peninsula approximately 12 miles east of Penzance and nine miles southwest of Falmouth. Helston is the most southerly town in the UK and is around further south than...

, Wendron

Wendron

Wendron is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated three miles north of Helston.The Revd G. H. Doble served for almost twenty years as the Vicar of Wendron . Langdon recorded the existence of eight stone crosses in the parish, including two at Merther Uny...

, Gweek

Gweek

Gweek is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately three miles east of Helston. The civil parish was created from part of the parish of Constantine by boundary revision in 1986...

and — across the Helford River

Helford River

The Helford River is a ria located in Cornwall, England, UK, and not a true river. It is fed by a number of small streams into its numerous creeks...

— by Constantine, Kerrier

Constantine, Kerrier

Constantine is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately five miles west-southwest of Falmouth....

and Mawnan

Mawnan

Mawnan is a civil parish in south Cornwall, United Kingdom . It is situated in the former administrative district of Kerrier and is bounded to the south by the Helford River, to the east by the sea, and to the west by Constantine parish...

.

The parishes on the peninsula proper are (west to east):

- Northern parishes:

- GunwalloeGunwalloeGunwalloe is a coastal civil parish and a village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Lizard Peninsula three miles south of Helston and partly contains The Loe, the largest natural freshwater lake in Cornwall.-History:...

- CuryCuryCury is a civil parish and village in southwest Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately four miles south of Helston on The Lizard peninsula. The parish is named for St Corentin and is recorded in the Domesday Book as Chori....

- Mawgan-in-MeneageMawgan-in-MeneageMawgan-in-Meneage is a civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated in the Meneage district of The Lizard peninsula south of Helston in the former administrative district of Kerrier....

- St Martin-in-MeneageSt Martin-in-MeneageSt Martin-in-Meneage is a civil parish and village in the Meneage district of the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom.The village is five miles south-southeast of Helston....

- ManaccanManaccanManaccan is a civil parish and village on the Lizard peninsula in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is situated approximately five miles south-southwest of Falmouth....

- St Anthony-in-MeneageSt Anthony-in-MeneageSt Anthony-in-Meneage is a coastal civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The parish is in the Meneage district of The Lizard peninsula...

- Gunwalloe

- Southern parishes:

- MullionMullion, CornwallMullion is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Lizard Peninsula approximately five miles south of Helston....

- Grade-RuanGrade-RuanGrade–Ruan is a civil parish on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom approximately ten miles south of Falmouth....

- St KeverneSt KeverneSt Keverne is a civil parish and village on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom.The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 started in St Keverne. The leader of the rebellion Michael An Gof was a blacksmith from St Keverne and is commemorated by a statue in the village...

- LandewednackLandewednackLandewednack is a civil parish and a hamlet in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hamlet is situated approximately ten miles south of Helston.Landewednack is the most southerly parish on the British mainland...

- Mullion

The Lizard's political history includes the 1497 Cornish rebellion

Cornish Rebellion of 1497

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 was a popular uprising by the people of Cornwall in the far southwest of Britain. Its primary cause was a response of people to the raising of war taxes by King Henry VII on the impoverished Cornish, to raise money for a campaign against Scotland motivated by brief...

which began in St Keverne

St Keverne

St Keverne is a civil parish and village on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom.The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 started in St Keverne. The leader of the rebellion Michael An Gof was a blacksmith from St Keverne and is commemorated by a statue in the village...

. The village blacksmith Michael Joseph

Michael An Gof

Michael Joseph and Thomas Flamank were the leaders of the Cornish Rebellion of 1497....

(Michael An Gof in Cornish, meaning blacksmith) led the uprising, protesting against the punitive taxes levied by Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

to pay for the war against the Scots. The uprising was routed on its march to London and the two leaders, Michael Joseph and Thomas Flamank

Thomas Flamank

Thomas Flamank was a lawyer from Cornwall who together with Michael An Gof led the Cornish Rebellion against taxes in 1497....

, were subsequently hanged, drawn and quartered.

Technology

TitaniumTitanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ti and atomic number 22. It has a low density and is a strong, lustrous, corrosion-resistant transition metal with a silver color....

was discovered here by the Reverend William Gregor

William Gregor

William Gregor was the British clergyman and mineralogist who discovered the elemental metal titanium.-Early years:...

in 1791.

In 1869, John Pender formed the Falmouth Gibraltar and Malta Telegraph company, intending to connect India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

with an undersea cable. Although intended to land at Falmouth, the final landing point was Porthcurno

Porthcurno

Porthcurno is a small village in the parish of St. Levan located in a valley on the south coast of the county of Cornwall, England in the United Kingdom. It is approximately to the west of the market town of Penzance and about from Land's End, the most westerly point of the English mainland...

near Land's End

Land's End

Land's End is a headland and small settlement in west Cornwall, England, within the United Kingdom. It is located on the Penwith peninsula approximately eight miles west-southwest of Penzance....

.

In 1900 Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi was an Italian inventor, known as the father of long distance radio transmission and for his development of Marconi's law and a radio telegraph system. Marconi is often credited as the inventor of radio, and indeed he shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand...

stayed the Housel Bay Hotel in his quest to locate a coastal radio station to receive signals from ships equipped with his apparatus. He leased a plot "in the wheat field adjoining the hotel" where the Lizard Wireless Telegraph Station still stands today. Recently restored by the National Trust, it looks as it did in January 1901, when Marconi received the distance record signals of 186 miles (299.3 km) from his transmitter station at Niton, Isle of Wight

Niton, Isle of Wight

Niton is a village on the Isle of Wight, near Ventnor with a thriving population of 1142, supporting two pubs, several churches,a pottery workshop/shop, a pharmacy and 3 local shops including a post office...

.

The Lizard Wireless Station is the oldest Marconi station to survive in its original state in the world and is located to the west of the Lloyds Signal Station in what appears to be a wooden hut.

In December 1901, on the cliffs above Poldhu

Poldhu

Poldhu is a small area in south Cornwall, England, UK, situated on the Lizard Peninsula; it comprises Poldhu Point and Poldhu Cove. It lies on the coast west of Goonhilly Downs, with Mullion to the south and Porthleven to the north...

, Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi was an Italian inventor, known as the father of long distance radio transmission and for his development of Marconi's law and a radio telegraph system. Marconi is often credited as the inventor of radio, and indeed he shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand...

sent a radio communication across the Atlantic to St. John's, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada. Situated in the country's Atlantic region, it incorporates the island of Newfoundland and mainland Labrador with a combined area of . As of April 2011, the province's estimated population is 508,400...

.

A radar station called RAF

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

Drytree was built during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. The site was later chosen for the Telstar project in 1962; its rocky foundations, clear atmosphere and extreme southerly location being uniquely suitable. This became the Goonhilly satellite

Satellite

In the context of spaceflight, a satellite is an object which has been placed into orbit by human endeavour. Such objects are sometimes called artificial satellites to distinguish them from natural satellites such as the Moon....

earth station, now owned by BT Group plc. Some important developments in television satellite transmission were made at Goonhilly station.

A wind farm

Wind turbine

A wind turbine is a device that converts kinetic energy from the wind into mechanical energy. If the mechanical energy is used to produce electricity, the device may be called a wind generator or wind charger. If the mechanical energy is used to drive machinery, such as for grinding grain or...

exists near to the Goonhilly station site.

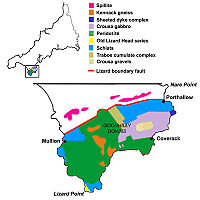

Geology

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

.

An ophiolite is a suite of geological formations which represent a slice through a section of ocean crust

Oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the part of Earth's lithosphere that surfaces in the ocean basins. Oceanic crust is primarily composed of mafic rocks, or sima, which is rich in iron and magnesium...

(including the upper level of the mantle

Mantle (geology)

The mantle is a part of a terrestrial planet or other rocky body large enough to have differentiation by density. The interior of the Earth, similar to the other terrestrial planets, is chemically divided into layers. The mantle is a highly viscous layer between the crust and the outer core....

) thrust onto the continental crust

Continental crust

The continental crust is the layer of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks which form the continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as continental shelves. This layer is sometimes called sial due to more felsic, or granitic, bulk composition, which lies in...

.

The Lizard formations comprise three main units; the serpentinite

Serpentinite

Serpentinite is a rock composed of one or more serpentine group minerals. Minerals in this group are formed by serpentinization, a hydration and metamorphic transformation of ultramafic rock from the Earth's mantle...

s, the "oceanic complex" and the metamorphic

Metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rock is the transformation of an existing rock type, the protolith, in a process called metamorphism, which means "change in form". The protolith is subjected to heat and pressure causing profound physical and/or chemical change...

basement.

Ecology

Several nature sites exist on the Lizard Peninsula; Predannack nature reserve, Mullion Island, Goonhilly DownsGoonhilly Downs

Goonhilly Downs is a Site of Special Scientific Interest that forms a raised plateau in the central western area of the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, England, UK. Situated just south of Helston and the Naval Air Station at Culdrose, it is famous for its Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station, the...

and the National Seal sanctuary

National Seal Sanctuary, Gweek

Gweek Seal Sanctuary is a charity funded sanctuary for injured seal pups. It is situated on the banks of the Helford River in Cornwall, England, UK and there is a road along the creek from the centre of Gweek village to the sanctuary's large car park....

at Gweek

Gweek

Gweek is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately three miles east of Helston. The civil parish was created from part of the parish of Constantine by boundary revision in 1986...

. An area of the Lizard coverning 16.62 square kilometres (6.4 sq mi) is designated a National Nature Reserve

National Nature Reserve

For details of National nature reserves in the United Kingdom see:*National Nature Reserves in England*National Nature Reserves in Northern Ireland*National Nature Reserves in Scotland*National Nature Reserves in Wales...

because of its coastal grasslands and heaths and inland heaths. The peninsula contains 3 main Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), both noted for their endangered insects and plants, as well as their geology. The first is East Lizard Heathlands SSSI, the second is Caerthillian to Kennack

Caerthillian to Kennack

Caerthillian to Kennack is a coastal Site of Special Scientific Interest on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, England, UK, noted for both its biological and geological interest...

SSSI and the third is West Lizard SSSI, of which the important wetland, Hayle Kimbro Pool

Hayle Kimbro Pool

Hayle Kimbro Pool is a wetland on The Lizard, Cornwall. It is situated two miles southeast of Mullion immediately northeast of Predannack airfield at ....

, forms a part of.

The area is also home to one of England's rarest breeding birds — the Chough

Chough

The Red-billed Chough or Chough , Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax, is a bird in the crow family; it is one of only two species in the genus Pyrrhocorax...

. This species of crow is distinctive due to its red beak and legs and haunting "chee-aw" call. Chough began breeding on Lizard in 2002 following a concerted effort by the Cornish Chough Project in conjunction with DEFRA

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs is the government department responsible for environmental protection, food production and standards, agriculture, fisheries and rural communities in the United Kingdom...

and the RSPB.

The Lizard contains some of the most specialised flora of any area in Britain, including many Red Data Book

IUCN Red List

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species , founded in 1963, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biological species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature is the world's main authority on the conservation status of species...

plant species. Of particular note is the Cornish heath

Cornish heath

The Cornish heath is a species of heath that bears pink flowers and mid-green foliage. This is a shrub, reaching 0.75 m by 0.75 m. Its English name comes from the fact that, in Great Britain, it is only found on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, where the unusual geology gives rise to the alkaline...

, Erica vagans, that occurs in abundance here, but which is found nowhere else in Britain. It is also one of the few places where the rare formicine ant

Ant

Ants are social insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from wasp-like ancestors in the mid-Cretaceous period between 110 and 130 million years ago and diversified after the rise of flowering plants. More than...

, Formica exsecta, (the narrow-headed ant), can be found.

Portrayal in literature and film

Daphne du MaurierDaphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning DBE was a British author and playwright.Many of her works have been adapted into films, including the novels Rebecca and Jamaica Inn and the short stories "The Birds" and "Don't Look Now". The first three were directed by Alfred Hitchcock.Her elder sister was...

based many novels on this part of Cornwall, including Frenchman's Creek.

The Lizard was featured on the BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

television

Television

Television is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

programme Seven Natural Wonders

Seven Natural Wonders

Seven Natural Wonders was a television series that was broadcast on BBC Two from 3 May to 20 June 2005. The programme took an area of England each week and, from votes by the people living in that area, showed the 'seven natural wonders' of that area in a programme.The programmes were:The series...

as one of the wonders of the South West.

In James Clavell

James Clavell

James Clavell, born Charles Edmund DuMaresq Clavell was an Australian-born, British novelist, screenwriter, director and World War II veteran and prisoner of war...

's novel Shogun

Shogun

A was one of the hereditary military dictators of Japan from 1192 to 1867. In this period, the shoguns, or their shikken regents , were the de facto rulers of Japan though they were nominally appointed by the emperor...

, ship's pilot Vasco Rodrigues challenges John Blackthorne to recite the latitude of the Lizard to verify that Blackthorne is a fellow seaman.