John of England

Encyclopedia

John also known as John Lackland (French: Sansterre), was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death. During John's reign, England lost the duchy of Normandy

to King Philip II of France

, which resulted in the collapse of most of the Angevin Empire

and contributed to the subsequent growth in power of the Capetian dynasty

during the 13th century. The baronial revolt

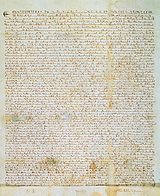

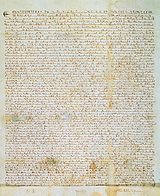

at the end of John's reign led to the signing of the Magna Carta

, a document often considered to be an early step in the evolution of the constitution of the United Kingdom

.

John, the youngest of five sons of King Henry II of England

and Eleanor of Aquitaine

, was at first not expected to inherit significant lands. Following the failed rebellion of his elder brothers between 1173 and 1174, however, John became Henry's favourite child. He was appointed the Lord of Ireland in 1177 and given lands in England and on the continent. John's elder brothers William, Henry

and Geoffrey

died young; by the time Richard I

became king in 1189, John was a potential heir to the throne. John unsuccessfully attempted a rebellion against Richard's royal administrators whilst his brother was participating in the Third Crusade

. Despite this, after Richard died in 1199, John was proclaimed king of England, and came to an agreement with Philip II of France to recognise John's possession of the continental Angevin lands at the peace treaty of Le Goulet

in 1200.

When war with France broke out again in 1202, John achieved early victories, but shortages of military resources and his treatment of Norman

, Breton

and Anjou

nobles resulted in the collapse of his empire in northern France in 1204. John spent much of the next decade attempting to regain these lands, raising huge revenues, reforming his armed forces and rebuilding continental alliances. John's judicial reforms had a lasting, positive impact on the English common law system, as well as providing an additional source of revenue. An argument with Pope Innocent III

led to John's excommunication

in 1209, a dispute finally settled by the king in 1213. John's attempt to defeat Philip in 1214 failed due to the French victory over John's allies at the battle of Bouvines

. When he returned to England, John faced a rebellion by many of his barons, who were unhappy with his fiscal policies and his treatment of many of England's most powerful nobles. Although both John and the barons agreed to the Magna Carta peace treaty in 1215, neither side complied with its conditions. Civil war

broke out shortly afterwards, with the barons aided by Louis of France

. It soon descended into a stalemate. John died of dysentery

contracted whilst on campaign in eastern England during late 1216; supporters of his son Henry III

went on to achieve victory over Louis and the rebel barons the following year.

Contemporary chroniclers were mostly critical of John's performance as king, and his reign has since been the subject of significant debate and periodic revision by historians from the 16th century onwards. Historian Jim Bradbury

has summarised the contemporary historical opinion of John's positive qualities, observing that John is today usually considered a "hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general". Nonetheless, modern historians agree that he also had many faults as king, including what historian Ralph Turner describes as "distasteful, even dangerous personality traits", such as pettiness, spitefulness and cruelty. These negative qualities provided extensive material for fiction writers in the Victorian era

, and John remains a recurring character within Western popular culture, primarily as a villain in films and stories depicting the Robin Hood

legends.

and Eleanor of Aquitaine

on 24 December 1166. Henry had inherited significant territories along the Atlantic seaboard – Anjou

, Normandy

and England

– and expanded his empire by conquering Brittany

. Henry married the powerful Eleanor of Aquitaine, who reigned over the Duchy of Aquitaine and had a tenuous claim to Toulouse and Auvergne

in southern France, in addition to being the former wife of Louis VII of France

. The result was the Angevin Empire

, named after Henry's paternal title as Count of Anjou and, more specifically, its seat in Angers

. The Empire, however, was inherently fragile: although all the lands owed allegiance to Henry, the disparate parts each had their own histories, traditions and governance structures. As one moved south through Anjou and Aquitaine, the extent of Henry's power in the provinces diminished considerably, scarcely resembling the modern concept of an empire at all. Some of the traditional ties between parts of the empire such as Normandy and England were slowly dissolving over time. It was unclear what would happen to the empire on Henry's death. Although the tradition of primogeniture

, under which an eldest son would inherit all his father's lands, was slowly becoming more widespread across Europe, it was less popular amongst the Norman kings of England. Most believed that Henry would divide the empire, giving each son a substantial portion, hoping that his children would then continue to work together as allies after his death. To complicate matters, much of the Angevin empire was owned by Henry only as a vassal of the King of France of the rival line of the House of Capet

. Henry had often allied himself with the Holy Roman Emperor

against France, making the feudal relationship even more challenging.

Shortly after his birth, John was passed from Eleanor into the care of a wet nurse

, a traditional practice for medieval noble families. Eleanor then left for Poitiers

, the capital of Aquitaine, and sent John and his sister Joan

north to Fontevrault Abbey. This may have been done with the aim of steering her youngest son, with no obvious inheritance, towards a future ecclesiastical career. Eleanor spent the next few years conspiring against her husband Henry and neither parent played a part in John's very early life. John was probably, like his brothers, assigned a magister whilst he was at Fontevrault, a teacher charged with his early education and with managing the servants of his immediate household; John was later taught by Ranulph Glanville, a leading English administrator. John spent some time as a member of the household of his eldest living brother Henry the Young King

, where he probably received instruction in hunting and military skills.

John would grow up to be around 5 ft 5 in high (1.62 m), relatively short for royalty of the day, with a "powerful, barrel-chested body" and dark red hair; he appeared to contemporaries to look like an inhabitant of Poitou

. John enjoyed reading and, unusual for the period, built up a travelling library of books. He enjoyed gambling, in particular on backgammon

, and was an enthusiastic hunter, even by medieval standards. He liked music, although not songs. John would become a "connoisseur of jewels", building up a large collection, and became famous for his opulent clothes and also, according to French chroniclers, for his fondness for bad wine. As John grew up, he became known for sometimes being "genial, witty, generous and hospitable"; at other moments, he could be jealous, over-sensitive and prone to fits of rage, "biting and gnawing his fingers" in anger.

was to be appointed the Count of Poitou and would be given control of Aquitaine, whilst Geoffrey

was to become the Duke of Brittany. At this time it seemed unlikely that John would ever inherit substantial lands, and John was jokingly nicknamed "Lackland" by his father.

Henry II wanted to secure the southern borders of Aquitaine and decided to betroth his youngest son to Alais, the daughter and heiress of Humbert III of Savoy

. As part of this agreement John was promised the future inheritance of Savoy

, Piemonte

, Maurienne

, and the other possessions of Count Humbert. For his part in the potential marriage alliance, Henry II transferred the castles of Chinon, Loudun

and Mirebeau

into John's name; as John was only five years old his father would continue to control them for practical purposes. Henry the Young King was unimpressed by this; although he had yet to be granted control of any castles in his new kingdom, these were effectively his future property and had been given away without consultation. Alais made the trip over the Alps and joined Henry II's court, but she died before marrying John, which left the prince once again without an inheritance.

In 1173 John's elder brothers, backed by Eleanor, rose in revolt against Henry in the short-lived rebellion of 1173 to 1174. Growing irritated with his subordinate position to Henry II and increasingly worried that John might be given additional lands and castles at his expense, Henry the Young King travelled to Paris

and allied himself with Louis VII

. Eleanor, irritated by her husband's persistent interference in Aquitaine, encouraged Richard and Geoffrey to join their brother Henry in Paris. Henry II triumphed over the coalition of his sons, but was generous to them in the peace settlement agreed at Montlouis

. Henry the Young King was allowed to travel widely in Europe with his own household of knights, Richard was given Aquitaine back, and Geoffrey was allowed to return to Brittany; only Eleanor was imprisoned for her role in the revolt.

John had spent the conflict travelling alongside his father and was given widespread possessions across the Angevin empire as part of the Montlouis settlement; from then onwards, most observers regarded John as Henry II's favourite child, although he was the furthest removed in terms of the royal succession. Henry II began to find more lands for John, mostly at various nobles' expense. In 1175 he appropriated the estates of the late Earl of Cornwall

and gave them to John. The following year, Henry disinherited the sisters of Isabelle of Gloucester, contrary to legal custom, and betrothed John to the now extremely wealthy Isabelle. In 1177, at the Council of Oxford, Henry dismissed William FitzAldelm as the Lord of Ireland

and replaced him with the ten-year-old John.

Henry the Young King fought a short war with his brother Richard in 1183 over the status of England, Normandy and Aquitaine. Henry II moved in support of Richard, and Henry the Young King died from dysentery

at the end of the campaign. With his primary heir dead, Henry rearranged the plans for the succession: Richard was to be made King of England, albeit without any actual power until the death of his father; Geoffrey would retain Brittany; and John would now become the Duke of Aquitaine in place of Richard. Richard refused to give up Aquitaine; Henry II was furious and ordered John, with help from Geoffrey, to march south and retake the duchy by force. The two attacked the capital of Poitiers, and Richard responded by attacking Brittany. The war ended in stalemate and a tense family reconciliation in England at the end of 1184.

In 1185 John made his first visit to Ireland

, accompanied by three hundred knights and a team of administrators. Henry had tried to have John officially proclaimed King of Ireland, but Pope Lucius III would not agree. John's first period of rule in Ireland was not a success. Ireland had only recently been conquered by Anglo-Norman forces, and tensions were still rife between Henry II, the new settlers and the existing inhabitants. John infamously offended the local Irish rulers by making fun of their unfashionable long beards, failed to make allies amongst the Anglo-Norman settlers, began to lose ground militarily against the Irish and finally returned to England later in the year, blaming the viceroy, Hugh de Lacy

, for the fiasco.

The problems amongst John's wider family continued to grow. His elder brother Geoffrey died during a tournament in 1186, leaving a posthumous son, Arthur, and an elder daughter, Eleanor. The duchy of Brittany was given to Arthur rather than John, but Geoffrey's death brought John slightly closer to the throne of England. The uncertainty about what would happen after Henry's death continued to grow; Richard was keen to join a new crusade and remained concerned that whilst he was away Henry would appoint John his formal successor. Richard began discussions about a potential alliance with Philip II in Paris during 1187, and the next year Richard gave homage to Philip in exchange for support for a war against Henry. Richard and Philip fought a joint campaign against Henry, and by the summer of 1189 the king made peace, promising Richard the succession. John initially remained loyal to his father, but changed sides once it appeared that Richard would win. Henry died shortly afterwards.

When John's elder brother Richard became king in September 1189, he had already declared his intention of joining the Third Crusade

When John's elder brother Richard became king in September 1189, he had already declared his intention of joining the Third Crusade

. Richard set about raising the huge sums of money required for this expedition through the sale of lands, titles and appointments, and attempted to ensure that he would not face a revolt while away from his empire. John was made Count of Mortain, was married to the wealthy Isabel of Gloucester

, and was given valuable lands in Lancaster and the counties of Cornwall

, Derby

, Devon

, Dorset

, Nottingham

and Somerset

, all with the aim of buying his loyalty to Richard whilst the king was on crusade. Richard retained royal control of key castles in these counties, thereby preventing John from accumulating too much military and political power. In return, John promised not to visit England for the next three years, thereby in theory giving Richard adequate time to conduct a successful crusade and return from the Levant

without fear of John seizing power. Richard left political authority in England – the post of justiciar – jointly in the hands of Bishop Hugh de Puiset

and William Mandeville

, and made William Longchamp

, the Bishop of Ely

, his chancellor. Mandeville immediately died, and Longchamp took over as joint justiciar with Puiset, which would prove to be a less than satisfactory partnership. Eleanor, the queen mother, convinced Richard to allow John into England in his absence.

The political situation in England rapidly began to deteriorate. Longchamp refused to work with Puiset and became unpopular with the English nobility and clergy. John exploited this unpopularity to set himself up as an alternative ruler with his own royal court, complete with his own justiciar, chancellor and other royal posts, and was happy to be portrayed as an alternative regent, and possibly the next king. Armed conflict broke out between John and Longchamp, and by October 1191 Longchamp was isolated in the Tower of London

with John in control of the city of London, thanks to promises John had made to the citizens in return for recognition as Richard's heir presumptive. At this point Walter of Coutances, the Archbishop of Rouen

, returned to England, having been sent by Richard to restore order. John's position was undermined by Walter's relative popularity and by the news that Richard had married whilst in Cyprus, which presented the possibility that Richard would have legitimate children and heirs.

The political turmoil continued. John began to explore an alliance with the French king Philip II, freshly returned from the crusade. John hoped to acquire Normandy, Anjou and the other lands in France held by Richard in exchange for allying himself with Philip. John was persuaded not to pursue an alliance by his mother. Longchamp, who had left England after Walter's intervention, now returned, and argued that he had been wrongly removed as justiciar. John intervened, suppressing Longchamp's claims in return for promises of support from the royal administration, including a reaffirmation of his position as heir to the throne. When Richard still did not return from the crusade, John began to assert that his brother was dead or otherwise permanently lost. Richard had in fact been captured en route to England by the Duke of Austria

The political turmoil continued. John began to explore an alliance with the French king Philip II, freshly returned from the crusade. John hoped to acquire Normandy, Anjou and the other lands in France held by Richard in exchange for allying himself with Philip. John was persuaded not to pursue an alliance by his mother. Longchamp, who had left England after Walter's intervention, now returned, and argued that he had been wrongly removed as justiciar. John intervened, suppressing Longchamp's claims in return for promises of support from the royal administration, including a reaffirmation of his position as heir to the throne. When Richard still did not return from the crusade, John began to assert that his brother was dead or otherwise permanently lost. Richard had in fact been captured en route to England by the Duke of Austria

and was handed over to Emperor Henry VI

, who held him for ransom. John seized the opportunity and went to Paris, where he formed an alliance with Philip. He agreed to set aside his wife, Isabella of Gloucester, and marry Philip's sister, Alys

, in exchange for Philip's support. Fighting broke out in England between forces loyal to Richard and those being gathered by John. John's military position was weak and he agreed to a truce; in early 1194 the king finally returned to England, and John's remaining forces surrendered. John retreated to Normandy, where Richard finally found him later that year. Richard declared that his younger brother – despite being 27 years old – was merely "a child who has had evil counsellors" and forgave him, but removed his lands with the exception of Ireland.

For the remaining years of Richard's reign, John supported his brother on the continent, apparently loyally. Richard's policy on the continent was to attempt to regain the castles he had lost to Philip II whilst on crusade through steady, limited campaigns. He allied himself with the leaders of Flanders

, Boulogne and the Holy Roman Empire

to apply pressure on Philip from Germany. In 1195 John successfully conducted a sudden attack and siege of Évreux

castle, and subsequently managed the defences of Normandy against Philip. The following year, John seized the town of Gamaches

and led a raiding party within 50 miles (80.5 km) of Paris, capturing the Bishop of Beauvais

. In return for this service, Richard withdrew his malevontia (ill-will) towards John, restored him to the county of Gloucestershire and made him again the Count of Mortain.

After Richard's death on 6 April 1199 there were two potential claimants to the Angevin throne: John, whose claim rested on being the sole surviving son of Henry II

After Richard's death on 6 April 1199 there were two potential claimants to the Angevin throne: John, whose claim rested on being the sole surviving son of Henry II

, and young Arthur of Brittany

, who held a claim as the son of Geoffrey

, John's elder brother. Richard appears to have started to recognise John as his legitimate heir in the final years before his death, but the matter was not clear-cut and medieval law gave little guidance as to how the competing claims should be decided. With Norman law favouring John as the only surviving son of Henry II and Angevin law favouring Arthur as the heir of Henry's elder son, the matter rapidly became an open conflict. John was supported by the bulk of the English and Norman nobility and was crowned at Westminster, backed by his mother, Eleanor. Arthur was supported by the majority of the Breton, Maine and Anjou nobles and received the support of Philip II

, who remained committed to breaking up the Angevin territories on the continent. With Arthur's army pressing up the Loire valley

towards Angers

and Philip's forces moving down the valley towards Tours

, John's continental empire was in danger of being cut in two.

Warfare in Normandy at the time was shaped by the defensive potential of castles and the increasing costs of conducting campaigns. The Norman frontiers had limited natural defences but were heavily reinforced with castles, such as Château Gaillard, at strategic points, built and maintained at considerable expense. It was difficult for a commander to advance far into fresh territory without having secured his lines of communication by capturing these fortifications, which slowed the progress of any attack. Armies of the period could be formed from either feudal or mercenary forces. Feudal levies could only be raised for a fixed length of time before they returned home, forcing an end to a campaign; mercenary forces, often called Brabançon

s after the Duchy of Brabant

but actually recruited from across northern Europe, could operate all year long and provide a commander with more strategic options to pursue a campaign, but cost much more than equivalent feudal forces. As a result commanders of the period were increasingly drawing on larger numbers of mercenaries.

After his coronation, John moved south into France with military forces and adopted a defensive posture along the eastern and southern Normandy borders. Both sides paused for desultory negotiations before the war recommenced; John's position was now stronger, thanks to confirmation that Count Baldwin

of Flanders

and Renaud of Boulogne had renewed the anti-French alliances they had previously agreed to with Richard. The powerful Anjou nobleman William de Roches

was persuaded to switch sides from Arthur to John; suddenly the balance seemed to be tipping away from Philip and Arthur in favour of John. Neither side was keen to continue the conflict, and following a papal truce the two leaders met in January 1200 to negotiate possible terms for peace. From John's perspective, what then followed represented an opportunity to stabilise control over his continental possessions and produce a lasting peace with Philip in Paris. John and Philip negotiated the May 1200 Treaty of Le Goulet

; by this treaty, Philip recognised John as the rightful heir to Richard in respect to his French possessions, temporarily abandoning the wider claims of his client, Arthur. John, in turn, abandoned Richard's former policy of containing Philip through alliances with Flanders and Boulogne, and accepted Philip's right as the legitimate feudal overlord of John's lands in France. John's policy earned him the disrespectful title of "John Softsword" from some English chroniclers, who contrasted his behaviour with his more aggressive brother, Richard.

. In order to remarry, John first needed to abandon Isabel, Countess of Gloucester, his first wife; John accomplished this by arguing that he had failed to get the necessary papal permission

to marry Isabel in the first place – as a cousin, John could not have legally wed her without this. It remains unclear why John chose to marry Isabella of Angoulême. Contemporary chroniclers argued that John had fallen deeply in love with Isabella, and John may have been motivated by desire for an apparently beautiful, if rather young, girl. On the other hand, the Angoumois lands that came with Isabella were strategically vital to John: by marrying Isabella, John was acquiring a key land route between Poitou and Gascony, which significantly strengthened his grip on Aquitaine.

Unfortunately, Isabella was already engaged to Hugh de Lusignan

, an important member of a key Poitou noble family and brother of Raoul de Lusignan

, the Count of Eu, who possessed lands along the sensitive eastern Normandy border. Just as John stood to benefit strategically from marrying Isabella, so the marriage threatened the interests of the Lusignans, whose own lands currently provided the key route for royal goods and troops across Aquitaine. Rather than negotiating some form of compensation, John treated Hugh "with contempt"; this resulted in a Lusignan uprising that was promptly crushed by John, who also intervened to suppress Raoul in Normandy.

Although John was the Count of Poitou and therefore the rightful feudal lord over the Lusignans, they could legitimately appeal John's actions in France to his own feudal lord, Philip. Hugh did exactly this in 1201 and Philip summoned John to attend court in Paris in 1202, citing the Le Goulet treaty to strengthen his case. John was unwilling to weaken his authority in western France in this way. He argued that he need not attend Philip's court because of his special status as the Duke of Normandy, who was exempt by feudal tradition from being called to the French court. Philip argued that he was summoning John not as the Duke of Normandy, but as the Count of Poitou, which carried no such special status. When John still refused to come, Philip declared John in breach of his feudal responsibilities, reassigned all of John's lands that fell under the French crown to Arthur – with the exception of Normandy, which he took back for himself – and began a fresh war against John.

in Anjou, he swung his mercenary army rapidly south to protect her. His forces caught Arthur by surprise and captured the entire rebel leadership at the battle of Mirebeau

. With his southern flank weakening, Philip was forced to withdraw in the east and turn south himself to contain John's army.

John's position in France was considerably strengthened by the victory at Mirebeau, but John's treatment of his new prisoners and of his ally, William de Roches, quickly undermined these gains. De Roches was a powerful Anjou noble, but John largely ignored him, causing considerable offence, whilst the king kept the rebel leaders in such bad conditions that twenty-two of them died. At this time most of the regional nobility were closely linked through kinship, and this behaviour towards their relatives was regarded as unacceptable. William de Roches and other of John's regional allies in Anjou and Brittany deserted him in favour of Philip, and Brittany rose in fresh revolt. John's financial situation was tenuous: once factors such as the comparative military costs of materiel and soldiers were taken into account, Philip enjoyed a considerable, although not overwhelming, advantage of resources over John.

Further desertions of John's local allies at the beginning of 1203 steadily reduced John's freedom to manoeuvre in the region. He attempted to convince Pope Innocent III to intervene in the conflict, but Innocent's efforts were unsuccessful. As the situation became worse for John, he appears to have decided to have Arthur killed, with the aim of removing his potential rival and of undermining the rebel movement in Brittany. Arthur had initially been imprisoned at Falaise and was then moved to Rouen. After this, Arthur's fate remains uncertain, but modern historians believe he was murdered by John. The annals of Margam Abbey

suggest that "John had captured Arthur and kept him alive in prison for some time in the castle of Rouen... when John was drunk he slew Arthur with his own hand and tying a heavy stone to the body cast it into the Seine

." Rumours of the manner of Arthur's death further reduced support for John across the region. Arthur's sister, Eleanor

, who had also been captured at Mirebeau, was kept imprisoned by John for many years, albeit in relatively good conditions.

In late 1203, John attempted to relieve Château Gaillard, which although besieged by Philip

was guarding the eastern flank of Normandy. John attempted a synchronised operation involving land-based and water-borne forces, considered by most historians today to have been imaginative in conception, but overly complex for forces of the period to have carried out successfully. John's relief operation was blocked by Philip's forces, and John turned back to Brittany in an attempt to draw Philip away from eastern Normandy. John successfully devastated much of Brittany, but did not deflect Philip's main thrust into the east of Normandy. Opinions vary amongst historians as to the military skill shown by John during this campaign, with most recent historians arguing that his performance was passable, although not impressive.

John's situation began to deteriorate rapidly. The eastern border region of Normandy had been extensively cultivated by Philip and his predecessors for several years, whilst Angevin authority in the south had been undermined by Richard's giving away of various key castles some years before. His use of routier mercenaries in the central regions had rapidly eaten away his remaining support in this area too, which set the stage for a sudden collapse of Angevin power. John retreated back across the Channel in December, sending orders for the establishment of a fresh defensive line to the west of Chateau Gaillard. In March 1204, Gaillard fell. John's mother Eleanor died the following month. This was not just a personal blow for John, but threatened to unravel the widespread Angevin alliances across the far south of France. Philip moved south around the new defensive line and struck upwards at the heart of the Duchy, now facing little resistance. By August, Philip had taken Normandy and advanced south to occupy Anjou and Poitou as well. John's only remaining possession on the Continent was now the Duchy of Aquitaine.

"; John continued this trend and claimed an "almost imperial status" for himself as ruler. During the 12th century, there were contrary opinions expressed about the nature of kingship, and many contemporary writers believed that monarchs should rule in accordance with the custom and the law, and take council with the leading members of the realm. There was as yet no model for what should happen if a king refused to do so. Despite his claim to unique authority within England, John would sometimes justify his actions on the basis that he had taken council with the barons. Modern historians remain divided as to whether John suffered from a case of "royal schizophrenia" in his approach to government, or if his actions merely reflected the complex model of Angevin kingship in the early 13th century.

John inherited a sophisticated system of administration in England, with a range of royal agents answering to the Royal Household: the Chancery kept written records and communications; the Treasury and the Exchequer

dealt with income and expenditure respectively; and various judges were deployed to deliver justice around the kingdom. Thanks to the efforts of men like Hubert Walter

, this trend towards improved record keeping continued into his reign. Like previous kings, John managed a peripatetic court that travelled around the kingdom, dealing with both local and national matters as he went. John was very active in the administration of England and was involved in every aspect of government. In part he was following in the tradition of Henry I

and Henry II, but by the 13th century the volume of administrative work had greatly increased, which put much more pressure on a king who wished to rule in this style. John was in England for much longer periods than his predecessors, which made his rule more personal than that of previous kings, particularly in previously ignored areas such as the north.

The administration of justice was of particular importance to John. Several new processes had been introduced to English law under Henry II, including novel disseisin

and mort d'ancestor

. These processes meant the royal courts had a more significant role in local law cases, which had previously been dealt with only by regional or local lords. John increased the professionalism of local sergeants and bailiffs, and extended the system of coroners first introduced by Hubert Walter in 1194, creating a new class of borough coroners. John worked extremely hard to ensure that this system operated well, through judges he had appointed, by fostering legal specialists and expertise, and by intervening in cases himself. John continued to try relatively minor cases, even during military crises. Viewed positively, Lewis Warren considers that John discharged "his royal duty of providing justice ... with a zeal and a tirelessness to which the English common law is greatly endebted". Seen more critically, John may have been motivated by the potential of the royal legal process to raise fees, rather than a desire to deliver simple justice; John's legal system also only applied to free men, rather than to all of the population. Nonetheless, these changes were popular with many free tenants, who acquired a more reliable legal system that could bypass the barons, against whom such cases were often brought. John's reforms were less popular with the barons themselves, especially as they remained subject to arbitrary and frequently vindictive royal justice.

; money raised through their rights as a feudal lord; and revenue from taxation. Revenue from the royal demesne was inflexible and had been diminishing slowly since the Norman conquest

. Matters were not helped by Richard's sale of many royal properties in 1189, and taxation played a much smaller role in royal income than in later centuries. English kings had widespread feudal rights which could be used to generate income, including the scutage

system, in which feudal military service was avoided by a cash payment to the king. He derived income from fines, court fees and the sale of charter

s and other privileges. John intensified his efforts to maximise all possible sources of income, to the extent that he has been described as "avaricious, miserly, extortionate and moneyminded". John also used revenue generation as a way of exerting political control over the barons: debts owed to the crown by the king's favoured supporters might be forgiven; collection of those owed by enemies was more stringently enforced.

The result was a sequence of innovative but unpopular financial measures. John levied scutage payments eleven times in his seventeen years as king, as compared to eleven times in total during the reign of the preceding three monarchs. In many cases these were levied in the absence of any actual military campaign, which ran counter to the original idea that scutage was an alternative to actual military service. John maximised his right to demand relief payments when estates and castles were inherited, sometimes charging enormous sums, beyond barons' abilities to pay. Building on the successful sale of sheriff appointments in 1194, John initiated a new round of appointments, with the new incumbents making back their investment through increased fines and penalties, particularly in the forests. Another innovation of Richard's, increased charges levied on widows who wished to remain single, was expanded under John. John continued to sell charters for new towns, including the planned town of Liverpool

, and charters were sold for markets across the kingdom and in Gascony

. The king introduced new taxes and extended existing ones. The Jews, who held a vulnerable position in medieval England, protected only by the king, were subject to huge taxes; £44,000 was extracted from the community by the tallage

of 1210; much of it was passed on to the Christian debtors of Jewish moneylenders.Early medieval financial figures have no easy contemporary equivalent, due to the different role of money in the economy. John created a new tax on income and movable goods in 1207 – effectively a version of a modern income tax – that produced £60,000; he created a new set of import and export duties payable directly to the crown. John found that these measures enabled to him to raise further resources through the confiscation of the lands of barons who could not pay or refused to pay.

At the start of John's reign there was a sudden change in prices, as bad harvests and high demand for food resulted in much higher prices for grain and animals. This inflationary pressure was to continue for the rest of the 13th century and had long-term economic consequences for England. The resulting social pressures were complicated by bursts of deflation that resulted from John's military campaigns. It was usual at the time for the king to collect taxes in silver, which was then re-minted into new coins; these coins would then be put in barrels and sent to royal castles around the country, to be used to hire mercenaries or to meet other costs. At those times when John was preparing for campaigns in Normandy, for example, huge quantities of silver had to be withdrawn from the economy and stored for months, which unintentionally resulted in periods during which silver coins were simply hard to come by, commercial credit difficult to acquire and deflationary pressure placed on the economy. The result was political unrest across the country. John attempted to address some of the problems with the English currency in 1204 and 1205 by carrying out a radical overhaul of the coinage, improving its quality and consistency.

.jpg) John's royal household was based around several groups of followers. One group was the familiares regis, John's immediate friends and knights who travelled around the country with him. They also played an important role in organising and leading military campaigns. Another section of royal followers were the curia regis

John's royal household was based around several groups of followers. One group was the familiares regis, John's immediate friends and knights who travelled around the country with him. They also played an important role in organising and leading military campaigns. Another section of royal followers were the curia regis

; these curiales were the senior officials and agents of the king and were essential to his day-to-day rule. Being a member of these inner circles brought huge advantages, as it was easier to gain favours from the king, file lawsuits, marry a wealthy heiress or have one's debts remitted. By the time of Henry II, these posts were increasingly being filled by "new men" from outside the normal ranks of the barons. This intensified under John's rule, with many lesser nobles arriving from the continent to take up positions at court; many were mercenary leaders from Poitou. These men included soldiers who would become infamous in England for their uncivilised behaviour, including Falkes de Breauté

, Geard d'Athies, Engelard de Cigongé and Philip Marc

. Many barons perceived the king's household as what Ralph Turner has characterised as a "narrow clique enjoying royal favour at barons' expense" staffed by men of lesser status.

This trend for the king to rely on his own men at the expense of the barons was exacerbated by the tradition of Angevin royal ira et malevolentia – "anger and ill-will" – and John's own personality. From Henry II onwards, ira et malevolentia had come to describe the right of the king to express his anger and displeasure at particular barons or clergy, building on the Norman concept of malevoncia – royal ill-will. In the Norman period, suffering the king's ill-will meant difficulties in obtaining grants, honours or petitions; Henry II had infamously expressed his fury and ill-will towards Thomas Becket

; this ultimately resulted in Becket's death. John now had the additional ability to "cripple his vassals" on a significant scale using his new economic and judicial measures, which made the threat of royal anger all the more serious.

John was deeply suspicious of the barons, particularly those with sufficient power and wealth to potentially challenge the king. Numerous barons were subjected to John's malevolentia, even including William Marshal

, a famous knight and baron normally held up as a model of utter loyalty. The most infamous case, which went beyond anything considered acceptable at the time, proved to be that of William de Braose

, a powerful marcher lord

with lands in Ireland. De Braose was subjected to punitive demands for money, and when he refused to pay a huge sum of 40,000 mark

s (equivalent to £26,666 at the time),Both the mark and the pound sterling were accountancy terms in this period; a mark was worth around two-thirds of a pound. his wife and one of his sons were imprisoned by John, which resulted in their death. De Braose died in exile in 1211, and his grandsons remained in prison until 1218. John's suspicions and jealousies meant that he rarely enjoyed good relationships with even the leading loyalist barons.

. It was common for kings and nobles of the period to keep mistresses, but chroniclers complained that John's mistresses were married noblewomen, which was considered unacceptable. John had at least five children with mistresses during his first marriage to Isabelle of Gloucester, and two of those mistresses are known to have been noblewomen. John's behaviour after his second marriage to Isabella is less clear, however. None of John's known illegitimate children were born after he remarried, and there is no actual documentary proof of adultery after that point, although John certainly had female friends amongst the court throughout the period. The specific accusations made against John during the baronial revolts are now generally considered to have been invented for the purposes of justifying the revolt; nonetheless, most of John's contemporaries seem to have held a poor opinion of his sexual behaviour.

The character of John's relationship with his second wife, Isabella of Angoulême, is unclear. John married Isabella whilst she was relatively young – her exact date of birth is uncertain, and estimates place her between at most 15 and more probably towards nine years old at the time of her marriage. Even by the standards of the time, Isabella was married whilst very young. John did not provide a great deal of money for his wife's household and did not pass on much of the revenue from her lands, to the extent that historian Nicholas Vincent has described him as being "downright mean" towards Isabella. Vincent concluded that the marriage was not a particularly "amicable" one. Other aspects of their marriage suggest a closer, more positive relationship. Chroniclers recorded that John had a "mad infatuation" with Isabella, and certainly John had conjugal relationships with Isabella between at least 1207 and 1215; they had five children. In contrast to Vincent, historian William Chester Jordan concludes that the pair were a "companionable couple" who had a successful marriage by the standards of the day.

John's lack of religious conviction has been noted by contemporary chroniclers and later historians, with some suspecting that John was at best impious, or even atheistic

, a very serious issue at the time. Contemporary chroniclers catalogued his various anti-religious habits at length, including his failure to take communion, his blasphemous remarks, and his witty but scandalous jokes about church doctrine, including jokes about the implausibility of the Resurrection

. They commented on the paucity of John's charitable donations to the church. Historian Frank McLynn

argues that John's early years at Fontevrault, combined with his relatively advanced education, may have turned him against the church. Other historians have been more cautious in interpreting this material, noting that chroniclers also reported John's personal interest in the life of St Wulfstan of Worcester and his friendships with several senior clerics, most especially with Hugh of Lincoln

, who was later declared a saint. Financial records show a normal royal household engaged in the usual feasts and pious observances – albeit with many records showing John's offerings to the poor to atone for routinely breaking church rules and guidance.

to threaten Paris, pin down the French forces and break Philip's internal lines of communication before landing a maritime force in the Duchy itself. Ideally, this plan would benefit from the opening of a second front on Philip's eastern frontiers with Flanders and Boulogne – effectively a re-creation of Richard's old strategy of applying pressure from Germany. All of this would require a great deal of money and soldiers.

John spent much of 1205 securing England against a potential French invasion. As an emergency measure, John recreated a version of Henry II's Assize of Arms

, with each shire

creating a structure to mobilise local levies. When the threat of invasion faded, John formed a large military force in England intended for Poitou, and a large fleet with soldiers under his own command intended for Normandy. To achieve this, John reformed the English feudal contribution to his campaigns, creating a more flexible system under which only one knight in ten would actually be mobilised, but would be financially supported by the other nine; knights would serve for an indefinite period. John built up a strong team of engineers for siege warfare and a substantial force of professional crossbowmen. The king was supported by a team of leading barons with military expertise, including William Longespée, William the Marshal

, Roger de Lacy and, until he fell from favour, the marcher lord William de Braose

.

John had already begun to improve his Channel

forces before the loss of Normandy and he rapidly built up further maritime capabilities after its collapse. Most of these ships were placed along the Cinque Ports

, but Portsmouth was also enlarged. By the end of 1204 he had around 50 large galleys available; another 54 vessels were built between 1209 and 1212. William of Wrotham

was appointed "keeper of the galleys", effectively John's chief admiral. Wortham was responsible for fusing John's galleys, the ships of the Cinque Ports and pressed merchant vessels into a single operational fleet. John adopted recent improvements in ship design, including new large transport ships called buisses and removable forecastle

s for use in combat.

Baronial unrest in England prevented the departure of the planned 1205 expedition, and only a smaller force under William Longespée deployed to Poitou. In 1206 John departed for Poitou himself, but was forced to divert south to counter a threat to Gascony

Baronial unrest in England prevented the departure of the planned 1205 expedition, and only a smaller force under William Longespée deployed to Poitou. In 1206 John departed for Poitou himself, but was forced to divert south to counter a threat to Gascony

from Alfonso VIII of Castile

. After a successful campaign against Alfonso, John headed north again, taking the city of Angers

. Philip moved south to meet John; the year's campaigning ended in stalemate and a two-year truce was made between the two rulers.

During the truce of 1206–1208, John focused on building up his financial and military resources in preparation for another attempt to recapture Normandy. John used some of this money to pay for new alliances on Philip's eastern frontiers, where the growth in Capetian power was beginning to concern France's neighbours. By 1212 John had successfully concluded alliances with Renault of Dammartin, who controlled Boulogne, and Count Ferdinand of Flanders

, as well as Otto IV

, a contender for the crown of Holy Roman Emperor

in Germany; Otto was also John's nephew. The invasion plans for 1212 were postponed because of fresh English baronial unrest about service in Poitou. Philip seized the initiative in 1213, sending his son, Prince Louis

, to invade Flanders with the intention of next launching an invasion of England. John was forced to postpone his own invasion plans to counter this threat. He launched his new fleet to attack the French at the harbour of Damme

. The attack was a success, destroying Philip's vessels and any chances of an invasion of England that year. John hoped to exploit this advantage by invading himself late in 1213, but baronial discontent again delayed his invasion plans until early 1214, in what would prove to be his final Continental campaign.

in 1174. This had been rescinded by Richard I in exchange for financial compensation in 1189, but the relationship remained uneasy. John began his reign by reasserting his sovereignty over the disputed northern counties. He refused William's request for the earldom of Northumbria

, but did not intervene in Scotland itself and focused on his continental problems. The two kings maintained a friendly relationship, meeting in 1206 and 1207, until it was rumoured in 1209 that William was intending to ally himself with Philip II of France. John invaded Scotland and forced William to sign the Treaty of Norham, which gave John control of William's daughters and required a payment of £10,000. This effectively crippled William's power north of the border, and by 1212 John had to intervene militarily to support the Scottish king against his internal rivals. John made no efforts to reinvigorate the Treaty of Falaise, though, and both William and Alexander remained independent kings, supported by, but not owing fealty to, John.

John remained Lord of Ireland throughout his reign. He drew on the country for resources to fight his war with Philip on the continent. Conflict continued in Ireland between the Anglo-Norman settlers and the indigenous Irish chieftains, with John manipulating both groups to expand his wealth and power in the country. During Richard's rule, John had successfully increased the size of his lands in Ireland, and he continued this policy as king. In 1210 the king crossed into Ireland with a large army to crush a rebellion by the Anglo-Norman lords; he reasserted his control of the country and used a new charter to order compliance with English laws and customs in Ireland. John stopped short of actively applying this charter to the native Irish kingdoms, but historian David Carpenter suspects that he might have done so, had the baronial conflict in England not intervened. Simmering tensions remained with the native Irish leaders even after John left for England.

Royal power in Wales was unevenly applied, with the country divided between the marcher lords

along the borders, royal territories in Pembrokeshire

and the more independent native Welsh lords of North Wales. John took a close interest in Wales and knew the country well, visiting every year between 1204 and 1211 and marrying his illegitimate daughter, Joan

, to the Welsh prince Llywelyn the Great

. The king used the marcher lords and the native Welsh to increase his own territory and power, striking a sequence of increasingly precise deals backed by royal military power with the Welsh rulers. A major royal expedition to enforce these agreements occurred in 1211, after Llywelyn attempted to exploit the instability caused by the removal of William de Braose, through the Welsh uprising of 1211

. John's invasion, striking into the Welsh heartlands, was a military success. Llywelyn came to terms that included an expansion of John's power across much of Wales, albeit only temporarily.

When the Archbishop of Canterbury

When the Archbishop of Canterbury

, Hubert Walter

, died on 13 July 1205, John became involved in a dispute with Pope Innocent III

that would lead to the king's excommunication

. The Norman and Angevin kings had traditionally exercised a great deal of power over the church within their territories. From the 1040s onwards, however, successive popes had put forward a reforming message that emphasised the importance of the church being "governed more coherently and more hierarchically from the centre" and established "its own sphere of authority and jurisdiction, separate from and independent of that of the lay ruler", in the words of historian Richard Huscroft. After the 1140s, these principles had been largely accepted within the English church, albeit with an element of concern about centralising authority in Rome. These changes

brought the customary rights of lay rulers such as John over ecclesiastical appointments into question. Pope Innocent was, according to historian Ralph Turner, an "ambitious and aggressive" religious leader, insistent on his rights and responsibilities within the church.

John wanted John de Gray

, the Bishop of Norwich

and one of his own supporters, to be appointed Archbishop of Canterbury after the death of Walter, but the cathedral chapter

for Canterbury Cathedral

claimed the exclusive right to elect Walter's successor. They favoured Reginald

, the chapter's sub-prior

. To complicate matters, the bishops of the province of Canterbury

also claimed the right to appoint the next Archbishop. The chapter secretly elected Reginald and he travelled to Rome to be confirmed; the bishops challenged the appointment and the matter was taken before Innocent. John forced the Canterbury chapter to change their support to John de Gray, and a messenger was sent to Rome to inform the papacy of the new decision. Innocent disavowed both Reginald and John de Gray, and instead appointed his own candidate, Stephen Langton

. John refused Innocent's request that he consent to Langton's appointment, but the pope consecrated Langton anyway in June 1207.

John was incensed about what he perceived as an abrogation of his customary right as monarch to influence the election. He complained both about the choice of Langton as an individual, as John felt he was overly influenced by the Capetian court in Paris, and about the process as a whole. He barred Langton from entering England and seized the lands of the archbishopric and other papal possessions. Innocent set a commission in place to try to convince John to change his mind, but to no avail. Innocent then placed an interdict

on England in March 1208, prohibiting clergy from conducting religious services, with the exception of baptisms for the young, and confessions and absolutions for the dying.

John treated the interdict as "the equivalent of a papal declaration of war". He responded by attempting to punish Innocent personally and to drive a wedge between those English clergy that might support him and those allying themselves firmly with the authorities in Rome. John seized the lands of those clergy unwilling to conduct services, as well as those estates linked to Innocent himself; he arrested the illicit concubines that many clerics kept during the period, only releasing them after the payment of fines; he seized the lands of members of the church who had fled England, and he promised protection for those clergy willing to remain loyal to him. In many cases, individual institutions were able to negotiate terms for managing their own properties and keeping the produce of their estates. By 1209 the situation showed no signs of resolution, and Innocent threatened to excommunicate

John treated the interdict as "the equivalent of a papal declaration of war". He responded by attempting to punish Innocent personally and to drive a wedge between those English clergy that might support him and those allying themselves firmly with the authorities in Rome. John seized the lands of those clergy unwilling to conduct services, as well as those estates linked to Innocent himself; he arrested the illicit concubines that many clerics kept during the period, only releasing them after the payment of fines; he seized the lands of members of the church who had fled England, and he promised protection for those clergy willing to remain loyal to him. In many cases, individual institutions were able to negotiate terms for managing their own properties and keeping the produce of their estates. By 1209 the situation showed no signs of resolution, and Innocent threatened to excommunicate

John if he did not acquiesce to Langton's appointment. When this threat failed, Innocent excommunicated the king in November 1209. Although theoretically a significant blow to John's legitimacy, this did not appear to greatly worry the king. Two of John’s close allies, Emperor Otto

and Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, had already suffered the same punishment themselves, and the significance of excommunication had been somewhat devalued. John simply tightened his existing measures and accrued significant sums from the income of vacant sees and abbeys: one 1213 estimate, for example, suggested the church had lost an estimated 100,000 marks (equivalent to £66,666 at the time) to John. Official figures suggest that around 14% of annual income from the English church was being appropriated by John each year.

Innocent gave some dispensations as the crisis progressed. Monastic communities were allowed to celebrate mass in private from 1209 onwards, and late in 1212 the viaticum

for the dying was authorised. The rules on burials and lay access to churches appear to have been steadily circumvented, at least unofficially. Although the interdict was a burden to much of the population, it did not result in rebellion against John. By 1213, though, John was increasingly worried about the threat of French invasion. Some contemporary chroniclers suggested that in January Philip II of France had been charged with deposing John on behalf of the papacy, although it appears that Innocent merely prepared secret letters in case Innocent needed to claim the credit if Philip did successfully invade England.

John finally negotiated terms for a reconciliation, and the papal terms for submission were accepted in the presence of the papal legate

Pandulph

in May 1213 at the Templar Church at Dover

. As part of the deal, John offered to surrender the Kingdom of England to the papacy for a feudal service of 1,000 marks

(equivalent to £666 at the time) annually: 700 marks (£466) for England and 300 marks (£200) for Ireland, as well as recompensing the church for revenue lost during the crisis. The agreement was formalised in the Bulla Aurea, or Golden Bull

. This resolution produced mixed responses. Although some chroniclers felt that John had been humiliated by the sequence of events, there was little public reaction. Innocent benefited from the resolution of his long-standing English problem, but John probably gained more, as Innocent became a firm supporter of John for the rest of his reign, backing him in both domestic and continental policy issues. Innocent immediately turned against Philip, calling upon him to reject plans to invade England and to sue for peace. John paid some of the compensation money he had promised the church, but he ceased making payments in late 1214, leaving two-thirds of the sum unpaid; Innocent appears to have conveniently forgotten this debt for the good of the wider relationship.

as justiciar

was an important factor, as he was considered an "abrasive foreigner" by many of the barons. The failure of John's French military campaign in 1214 was probably the final straw that precipitated the baronial uprising during John's final years as king; James Holt describes the path to civil war as "direct, short and unavoidable" following the defeat at Bouvines.

The first part of the campaign went well, with John out-manoeuvring the forces under the command of Prince Louis

and retaking the county of Anjou by the end of June. John besieged the castle of Roche-au-Moine

, a key stronghold, forcing Louis to give battle against John's larger army. The local Angevin nobles refused to advance with the king; left at something of a disadvantage, John retreated back to La Rochelle

. Shortly afterwards, Philip won the hard-fought battle of Bouvines

in the east against Otto and John's other allies, bringing an end to John's hopes of retaking Normandy. A peace agreement was signed in which John returned Anjou to Philip and paid the French king compensation; the truce was intended to last for six years. John arrived back in England in October.

Within a few months of John's return, rebel barons in the north and east of England were organising resistance to his rule. John held a council in London in January 1215 to discuss potential reforms and sponsored discussions in Oxford between his agents and the rebels during the spring. John appears to have been playing for time until Pope Innocent III could send letters giving him explicit papal support. This was particularly important for John, as a way of pressuring the barons but also as a way of controlling Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the meantime, John began to recruit fresh mercenary forces from Poitou, although some were later sent back to avoid giving the impression that the king was escalating the conflict. John announced his intent to become a crusader

Within a few months of John's return, rebel barons in the north and east of England were organising resistance to his rule. John held a council in London in January 1215 to discuss potential reforms and sponsored discussions in Oxford between his agents and the rebels during the spring. John appears to have been playing for time until Pope Innocent III could send letters giving him explicit papal support. This was particularly important for John, as a way of pressuring the barons but also as a way of controlling Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the meantime, John began to recruit fresh mercenary forces from Poitou, although some were later sent back to avoid giving the impression that the king was escalating the conflict. John announced his intent to become a crusader

, a move which gave him additional political protection under church law.

Letters of support from the pope arrived in April but by then the rebel barons had organised. They congregated at Northampton

in May and renounced their feudal ties to John, appointing Robert fitz Walter as their military leader. This self-proclaimed "Army of God" marched on London

, taking the capital as well as Lincoln

and Exeter

. John's efforts to appear moderate and conciliatory had been largely successful, but once the rebels held London they attracted a fresh wave of defectors from John's royalist faction. John instructed Langton to organise peace talks with the rebel barons.

John met the rebel leaders at Runnymede

, near Windsor Castle

, on 15 June 1215. Langton's efforts at mediation created a charter capturing the proposed peace agreement; it was later renamed Magna Carta

, or "Great Charter". The charter went beyond simply addressing specific baronial complaints, and formed a wider proposal for political reform, albeit one focusing on the rights of free men, not serfs and unfree labour. It promised the protection of church rights, protection from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, new taxation only with baronial consent and limitations on scutage

and other feudal payments. A council of twenty-five neutral barons would be created to monitor and ensure John's future adherence to the charter, whilst the rebel army would stand down and London would be surrendered to the king.

Neither John nor the rebel barons seriously attempted to implement the peace accord. The rebel barons suspected that the proposed baronial council would be unacceptable to John and that he would challenge the legality of the charter; they packed the baronial council with their own hardliners and refused to demobilise their forces or surrender London as agreed. Despite his promises to the contrary, John appealed to Innocent for help, observing that the charter compromised the pope's rights under the 1203 agreement that had appointed him John's feudal lord. Innocent obliged; he declared the charter "not only shameful and demeaning, but illegal and unjust" and excommunicated the rebel barons. The failure of the agreement led rapidly to the First Barons' War

.

, owned by Langton but left almost unguarded by the archbishop. John was well prepared for a conflict. He had stockpiled money to pay for mercenaries and ensured the support of the powerful marcher lords

with their own feudal forces, such as William Marshal and Ranulf of Chester. The rebels lacked the engineering expertise or heavy equipment necessary to assault the network of royal castles that cut off the northern rebel barons from those in the south. John's strategy was to isolate the rebel barons in London, protect his own supply lines to his key source of mercenaries in Flanders, prevent the French from landing in the south-east, and then win the war through slow attrition. John put off dealing with the badly deteriorating situation in North Wales, where Llywelyn the Great was leading a rebellion against the 1211 settlement.

John's campaign started well. In November John retook Rochester Castle in a sophisticated assault. One chronicler had not seen "a siege so hard pressed or so strongly resisted", whilst historian Reginald Brown describes it as "one of the greatest [siege] operations in England up to that time". Having regained the south-east John split his forces, sending William Longespée to retake the north of side of London and East Anglia, whilst John himself headed north via Nottingham

to attack the estates of the northern barons. Both operations were successful and the majority of the remaining rebels were pinned down in London. In January 1216 John marched against Alexander II of Scotland

, who had allied himself with the rebel cause. John took back Alexander's possessions in northern England in a rapid campaign and pushed up towards Edinburgh

over a ten-day period.

The rebel barons responded by inviting Prince Louis of France to lead them: Louis had a claim to the English throne by virtue of his marriage to Blanche of Castile

, the granddaughter of Henry II. Philip may have provided him with private support but refused to openly support Louis, who was excommunicated by Innocent for taking part in the war against John. Louis's planned arrival in England presented a significant problem for John, as the prince would bring with him naval vessels and siege engines essential to the rebel cause. Once John contained Alexander in Scotland, he marched south to deal with the challenge of the coming invasion.

Prince Louis intended to land in the south of England in May 1216, and John assembled a naval force to intercept him. Unfortunately for John, his fleet was dispersed by bad storms and Louis landed unopposed in Kent

. John hesitated and decided not to attack Louis immediately, either due to the risks of open battle or over concerns about the loyalty of his own men. Louis and the rebel barons advanced west and John retreated, spending the summer reorganising his defences across the rest of the kingdom. John saw several of his military household desert to the rebels, including his half-brother, William Longespée. By the end of the summer the rebels had regained the south-east of England and parts of the north.

In September 1216 John began a fresh, vigorous attack. He marched from the Cotswolds

In September 1216 John began a fresh, vigorous attack. He marched from the Cotswolds

, feigned an offensive to relieve the besieged Windsor Castle

, and attacked eastwards around London to Cambridge

to separate the rebel-held areas of Lincolnshire

and East Anglia. From there he travelled north to relieve the rebel siege at Lincoln and back east to King's Lynn

, probably to order further supplies from the continent.The town of King's Lynn

was simply called Lynn in the 13th century. In King's Lynn, John contracted dysentery

, which would ultimately prove fatal. Meanwhile, Alexander II invaded northern England again, taking Carlisle in August and then marching south to give homage to Prince Louis for his English possessions; John narrowly missed intercepting Alexander along the way. Tensions between Louis and the English barons began to increase, prompting a wave of desertions, including William Marshal's son William

and William Longespée, who both returned to John's faction.

The king returned west but is said to have lost a significant part of his baggage train along the way. Roger of Wendover

provides the most graphic account of this, suggesting that the king's belongings, including the Crown Jewels

, were lost as he crossed one of the tidal estuaries which empties into the Wash

, being sucked in by quicksand

and whirlpool

s. Accounts of the incident vary considerably between the various chroniclers and the exact location of the incident has never been confirmed; the losses may have involved only a few of his pack-horses. Modern historians assert that by October 1216 John faced a "stalemate", "a military situation uncompromised by defeat".

John's illness grew worse and by the time he reached Newark Castle

he was unable to travel any further; John died on the night of 18 October. Numerous – probably fictitious – accounts circulated soon after his death that he had been killed by poisoned ale, poisoned plums or a "surfeit of peaches". His body was escorted south by a company of mercenaries and he was buried in Worcester Cathedral

in front of the altar of St Wulfstan. A new sarcophagus

with an effigy

was made for him in 1232, in which his remains now rest.

. The civil war continued until royalist victories at the battles of Lincoln

and Dover

in 1217. Louis gave up his claim to the English throne and signed the Treaty of Lambeth

. The failed Magna Carta agreement was resuscitated by Marshal's protectorate and reissued in an edited form in 1217 as a basis for future government. Henry III continued his attempts to reclaim Normandy and Anjou until 1259, but John's continental losses and the consequent growth of Capetian power in the 13th century proved to mark a "turning point in European history".

John's first wife, Isabel, Countess of Gloucester, was released from imprisonment in 1214; she remarried twice, and died in 1217. John's second wife, Isabella of Angoulême

, left England for Angoulême

soon after the king's death; she became a powerful regional leader, but largely abandoned the children she had had by John. John had five legitimate children, all by Isabella. His eldest son, Henry III, ruled as king for the majority of the 13th century. Richard

became a noted European leader and ultimately the King of the Romans

in the Holy Roman Empire

. Joan

married Alexander II of Scotland

to become his queen consort. Isabella

married the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II

. His youngest daughter, Eleanor, married William Marshal's son, also called William

, and later the famous English rebel Simon de Montfort

. John had a number of illegitimate children by various mistresses, including nine sons – Richard, Oliver, John, Geoffrey, Henry, Osbert Gifford, Eudes, Bartholomew and probably Philip – and three daughters – Joan

, Maud and probably Isabel. Of these, Joan became the most famous, marrying Prince Llywelyn the Great

of Wales.

Historical interpretations of John have been subject to considerable change over the years. Medieval chronicle

Historical interpretations of John have been subject to considerable change over the years. Medieval chronicle

rs provided the first contemporary, or near contemporary, histories of John's reign. One group of chroniclers wrote early in John's life, or around the time of his accession, including Richard of Devizes

, William of Newburgh

, Roger of Hoveden

and Ralph de Diceto

. These historians were generally unsympathetic to John's behaviour under Richard's rule, but slightly more positive towards the very earliest years of John's reign. Reliable accounts of the middle and later parts of John's reign are more limited, with Gervase of Canterbury

and Ralph of Coggeshall

writing the main accounts; neither of them were positive about John's performance as king. Much of John's later, negative reputation was established by two chroniclers writing after the king's death, Roger of Wendover

and Matthew Paris

.

In the 16th century political and religious changes altered the attitude of historians towards John. Tudor

historians were generally favourably inclined towards the king, focusing on John's opposition to the Papacy and his promotion of the special rights and prerogatives of a king. Revisionist histories written by John Foxe

, William Tyndale

and Robert Barnes portrayed John as an early Protestant hero, and John Foxe

included the king in his Book of Martyrs

. John Speed

's Historie of Great Britaine in 1632 praised John's "great renown" as a king; he blamed the bias of medieval chroniclers for the king's poor reputation.

By the Victorian period in the 19th century historians were more inclined to draw on the judgements of the chroniclers and to focus on John's moral personality. Kate Norgate

, for example, argued that John's downfall had been due not to his failure in war or strategy, but due to his "almost superhuman wickedness", whilst James Ramsay blamed John's family background and his cruel personality for his downfall. Historians in the "Whiggish

" tradition, focusing on documents such as the Domesday Book

and Magna Carta

, trace a progressive and universalist

course of political and economic development in England over the medieval period. These historians were often inclined to see John's reign, and his signing of Magna Carta in particular, as a positive step in the constitutional development of England, despite the flaws of the king himself. Winston Churchill

, for example, argued that "[w]hen the long tally is added, it will be seen that the British nation and the English-speaking world owe far more to the vices of John than to the labours of virtuous sovereigns".

In the 1940s, new interpretations of John's reign began to emerge, based on research into the record evidence of his reign, such as pipe rolls, charters, court documents and similar primary records. Notably, an essay by Vivian Galbraith

in 1945 proposed a "new approach" to understanding the ruler. The use of recorded evidence was combined with an increased scepticism about two of the most colourful chroniclers of John's reign, Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris. In many cases the detail provided by these chroniclers, both writing after John's death, was challenged by modern historians. Interpretations of Magna Carta and the role of the rebel barons in 1215 have been significantly revised: although the charter's symbolic, constitutional value for later generations is unquestionable, in the context of John's reign most historians now consider it a failed peace agreement between "partisan" factions. There has been increasing debate about the nature of John's Irish policies. Specialists in Irish medieval history, such as Sean Duffy, have challenged the conventional narrative established by Lewis Warren

, suggesting that Ireland was less stable by 1216 than was previously supposed.

Most historians today, including John's recent biographers Ralph Turner and Lewis Warren, argue that John was an unsuccessful monarch, but note that his failings were exaggerated by 12th- and 13th-century chroniclers. Jim Bradbury

notes the consensus of contemporary historians that John was a "hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general", albeit, as Turner suggests, with "distasteful, even dangerous personality traits", including pettiness, spitefulness and cruelty. John Gillingham

, author of a major biography of Richard I, follows this line too, although he considers John a less effective general than do Turner or Warren; Bradbury takes a moderate line, but suggests that in recent years modern historians have been overly lenient towards John's numerous faults. Popular historian Frank McLynn

maintains a counter-revisionist perspective on John, arguing that the king's modern reputation amongst historians is "bizarre", and that as a monarch John "fails almost all those [tests] that can be legitimately set".

Popular representations of John first began to emerge during the Tudor period, mirroring the revisionist histories of the time. The anonymous play The Troublesome Reign of King John

Popular representations of John first began to emerge during the Tudor period, mirroring the revisionist histories of the time. The anonymous play The Troublesome Reign of King John

portrayed the king as a "proto-Protestant martyr", similar to that shown in John Bale

's morality play Kynge Johan, in which John attempts to save England from the "evil agents of the Roman Church". By contrast, Shakespeare's King John, a relatively anti-Catholic play that draws on The Troublesome Reign for its source material, offers a more "balanced, dual view of a complex monarch as both a proto-Protestant victim of Rome's machinations and as a weak, selfishly motivated ruler". Anthony Munday

's play The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington

portrays many of John's negative traits, but adopts a positive interpretation of the king's stand against the Roman Catholic Church, in line with the contemporary views of the Tudor monarchs. By the middle of the 17th century, plays such as Robert Davenport

's King John and Matilda

, although based largely on the earlier Elizabethan works, were transferring the role of Protestant champion to the barons and focusing more on the tyrannical aspects of John's behaviour.

Nineteenth-century fictional depictions of John were heavily influenced by Sir Walter Scott

's historical romance, Ivanhoe

, which presented "an almost totally unfavourable picture" of the king; the work drew on Victorian histories of the period and on Shakespeare's play. Scott's work influenced the late 19th-century children's writer Howard Pyle

's book The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood

, which in turn established John as the principal villain within the traditional Robin Hood

narrative. During the 20th century, John was normally depicted in fictional books and films alongside Robin Hood. Sam De Grasse

's role as John in the black-and-white 1922 film version

shows John committing numerous atrocities and acts of torture. Claude Rains

played John in the 1938 colour version

alongside Errol Flynn

, starting a trend for films to depict John as an "effeminate ... arrogant and cowardly stay-at-home". The character of John acts either to highlight the virtues of King Richard, or contrasts with the Sheriff of Nottingham