Ulster Scots language

Encyclopedia

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots (called Ulstèr-Scotch by the Ulster-Scots Agency

and Ulster-Scots Language Society) generally refers to the dialects of Scots

spoken in parts of Ulster

in Ireland

. Some definitions of Ulster Scots may also include Standard English

spoken with an Ulster Scots accent. This is a situation like that of Lowland Scots and Scottish Standard English

– where lexical items have been re-allocated to the phoneme

classes that are nearest to the equivalent standard classes.

Ulster Scots has been influenced by Mid Ulster English

and Ulster Irish

. Ulster Scots has also influenced Mid Ulster English, which is the dialect of most people in Ulster. As a result of the competing influences of English and Scots, varieties

of Ulster Scots can be described as 'more English' or 'more Scots'.

Scots dialects were brought to Ulster during the early 17th century, when large numbers of Scots speakers arrived from Scotland

during (and following) the Ulster Plantation

. The earliest Scots writing in Ulster dates from that time, and until the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, written Scots from Ulster was almost identical with that of Scotland.

Since the 1990s, new orthographies

have been created, which seek "to be as different to English (and occasionally Scots) as possible". It has been claimed that the recent "Ulster-Scots language and heritage cause has been set rolling only out of a sense of cultural rivalry among some Protestants

and unionists

, keen to counter-balance the onward march of the Irish language

movement".

or the 'hamely tongue'. Since the 1980s Ullans, a portmanteau neologism popularized by the physician, amateur historian and politician Dr Ian Adamson

, merging Ulster and Lallans

— the Scots for Lowlands — but also an acronym for “Ulster-Scots language in literature and native speech” and Ulstèr-Scotch, the preferred revivalist parlance, have also been used. Occasionally the term Hiberno-Scots is used, although it is usually used for the ethnic group rather than the vernacular.

Ulster Scots is spoken in east Antrim

, north Down

, north-east County Londonderry

, the Laggan area of Donegal

, and also in the fishing villages of the Mourne coast.

The 1999 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey found that 2% of Northern Ireland

residents claimed to speak Ulster Scots, which would mean a total speech community of approximately 30,000 in the territory. Other estimates range from 35,000 in Northern Ireland, to an "optimistic" total of 100,000 including the Republic of Ireland. Speaking at a seminar on 9 September 2004, Ian Sloan of the Northern Ireland Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

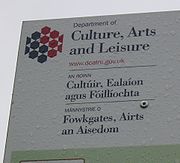

(DCAL) accepted that the 1999 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey "did not significantly indicate that unionists or nationalists were relatively any more or less likely to speak Ulster Scots, although in absolute terms there were more unionists who spoke Ulster Scots than nationalists".

, a BBC

report stating: "[The Agency] accused the academy of wrongly promoting Ulster-Scots as a language distinct from Scots." A position reflected in many of the Academic responses to the "Public Consultation on Proposals for an Ulster-Scots Academy"

of English

, for example Raymond Hickey, or by others as a variety

of the Scots language

, for example Dr. Caroline Macafee, who writes "Ulster Scots is [...] clearly a dialect of Central Scots." And "Ulster Scots is one dialect of Lowland Scots, now officially regarded as a language by the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages

." The Northern Ireland

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

considers Ulster Scots to be "the local variety of the Scots language."

Using the criteria on Ausbau languages developed by the German linguist Heinz Kloss

, Ulster Scots could qualify only as a Spielart or 'national dialect' of Scots (cf. British and American English), since it does not have the Mindestabstand, or 'minimum divergence' necessary to achieve language status through standardisation and codification.

The North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999, which gave effect to the implementation bodies incorporated the text of the agreement in its Schedule 1.

The declaration made by the United Kingdom Government regarding the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

reads as follows:

The definition from the North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999 above was used in the 1 July 2005 Second Periodical Report by the United Kingdom to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe outlining how the UK meets its obligations under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

The Good Friday Agreement (which does not refer to Ulster Scots as a "language") also recognises Ulster Scots as "part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland", and the Implementation Agreement established the cross-border Ulster-Scots Agency

(Tha Boord o Ulstèr-Scotch). The legislative remit laid down for the agency by the North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999 is: "the promotion of greater awareness and the use of Ullans and of Ulster-Scots cultural issues, both within Northern Ireland and throughout the island". The agency has adopted a mission statement: to promote the study, conservation, development and use of Ulster Scots as a living language; to encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture; and to promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots people.

The Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006 amended the Northern Ireland Act 1998

to insert a section (28D) entitled Strategies relating to Irish language and Ulster Scots language etc. which inter alia laid on the Executive Committee a duty to "adopt a strategy setting out how it proposes to enhance and develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture." This reflects the wording used in the St Andrews Agreement

to refer to the enhancement and development of "the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture".

, mainly Gaelic-speaking, had been settling in Ulster since the 15th century, but large numbers of Scots

-speaking Lowlanders, some 200,000, arrived during the 17th century following the 1610 Plantation

, with the peak reached during the 1690s. In the core areas of Scots settlement, Scots outnumbered English settlers by five or six to one.

Literature from shortly before the end of the unselfconscious tradition at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries is almost identical with contemporary writing from Scotland. W G Lyttle, writing in Paddy McQuillan's Trip Tae Glesco, uses the typically Scots forms kent and begood, now replaced in Ulster by the more mainstream Anglic

forms knew, knowed or knawed and begun. Many of the modest contemporary differences between Scots as spoken in Scotland and Ulster may be due to dialect levelling and influence from Mid Ulster English brought about through relatively recent demographic change rather than direct contact

with Irish, retention of older features or separate development.

The earliest identified writing in Scots in Ulster dates from 1571: a letter from Agnes Campbell of County Tyrone to Elizabeth I

on behalf of Turlough O'Neil, her husband. Although documents dating from the Plantation period show conservative Scots features, English forms started to predominate from the 1620s as Scots declined as a written medium.

In Ulster Scots-speaking areas there was traditionally a considerable demand for the work of Scottish poets, often in locally printed editions. Alexander Montgomerie

's The Cherrie and the Slae in 1700, shortly over a decade later an edition of poems by Sir David Lindsay, nine printings of Allan Ramsay's The Gentle shepherd between 1743 and 1793, and an edition of Robert Burns

' poetry in 1787, the same year as the Edinburgh edition, followed by reprints in 1789, 1793 and 1800. Among other Scottish poets published in Ulster were James Hogg

and Robert Tannahill

.

That was complemented by a poetry revival and nascent prose genre in Ulster, which started around 1720. The most prominent being the rhyming weaver

poetry, of which, some 60 to 70 volumes were published between 1750 and 1850, the peak being in the decades 1810 to 1840, although the first printed poetry (in the Habbie stanza

form) by an Ulster Scots writer was published in a broadsheet

in Strabane in 1735. These weaver poets looked to Scotland for their cultural and literary models and were not simple imitators but clearly inheritors of the same literary tradition following the same poetic and orthographic practices; it is not always immediately possible to distinguish traditional Scots writing from Scotland and Ulster. Among the rhyming weavers were James Campbell (1758–1818), James Orr

(1770–1816), Thomas Beggs (1749–1847), David Herbison (1800–1880), Hugh Porter (1780–1839) and Andrew McKenzie

(1780–1839).

Scots was also used in the narrative by Ulster novelists such as W. G. Lyttle (1844–1896) and Archibald McIlroy (1860–1915). By the middle of the 19th century the Kailyard school

of prose had become the dominant literary genre, overtaking poetry. This was a tradition shared with Scotland which continued into the early 20th century. Scots also regularly appeared in Ulster newspaper columns, especially in Antrim and Down, in the form of pseudonymous social commentary employing a folksy first-person style. The pseudonymous Bab M'Keen (probably successive members of the Weir family: John Weir, William Weir, and Jack Weir) provided comic commentaries in the Ballymena Observer and County Antrim Advertiser for over a hundred years from the 1880s.

A somewhat diminished tradition of vernacular poetry survived into the 20th century in the work of poets such as Adam Lynn, author of the 1911 collection Random Rhymes frae Cullybackey, John Stevenson (died 1932), writing as "Pat M'Carty", and John Clifford (1900–1983) from East Antrim. In the late 20th century the poetic tradition was revived, albeit often replacing the traditional Modern Scots

orthographic practice with a series of contradictory idiolect

s. Among the significant writers is James Fenton

, mostly using a blank verse form, but also occasionally the Habbie stanza. He employs an orthography that presents the reader with the difficult combination of eye dialect

, dense Scots, and a greater variety of verse forms than employed hitherto. The poet Michael Longley (born 1939) has experimented with Ulster Scots for the translation of Classical verse, as in his 1995 collection The Ghost Orchid.

Philip Robinson's (born 1946) writing has been described as verging on "post-modern

kailyard". He has produced a trilogy of novels Wake the Tribe o Dan (1998), The Back Streets o the Claw (2000) and The Man frae the Ministry (2005), as well as story books for children Esther, Quaen o tha Ulidian Pechts and Fergus an tha Stane o Destinie, and two volumes of poetry Alang the Shore (2005) and Oul Licht, New Licht (2009).

In 1992 the Ulster-Scots Language Society was formed for the protection and promotion of Ulster Scots, which some of its members viewed as a language in its own right, encouraging use in speech, writing and in all areas of life.

In 1992 the Ulster-Scots Language Society was formed for the protection and promotion of Ulster Scots, which some of its members viewed as a language in its own right, encouraging use in speech, writing and in all areas of life.

Within the terms of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages the British Government is obliged, among other things, to:

The Ulster-Scots Agency

, funded by DCAL in conjunction with the Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs

, is responsible for promotion of greater awareness and use of Ullans and of Ulster-Scots cultural issues, both within Northern Ireland and throughout the island. The agency was established as a result of the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

In 2001 the Institute of Ulster Scots Studies was established at the University of Ulster

An Ulster Scots Academy has been planned with the aim of conserving, developing, and teaching the language of Ulster-Scots in association with native speakers to the highest academic standards.

ist Ulster Scots has appeared, for example as "official translations", since the 1990s. However, it has little in common with traditional Scots orthography

as described in Grant and Dixon’s Manual of Modern Scots (1921). Aodán Mac Póilin

, an Irish language

activist, has described these revivalist orthographies as an attempt to make Ulster Scots an independent written language and to achieve official status. They seek "to be as different to English (and occasionally Scots) as possible". He described it as a hotchpotch of obsolete words, neologisms (example: stour-sucker for vacuum cleaner

), redundant spellings (example: qoho for who) and "erratic spelling". This spelling "sometimes reflects everyday Ulster Scots speech rather than the conventions of either modern or historic Scots, and sometimes does not". The result, Mac Póilin writes, is "often incomprehensible to the native speaker". In 2000, Dr John Kirk described the "net effect" of that "amalgam of traditional, surviving, revived, changed, and invented features" as an "artificial dialect". He added,

In 2005, Gavin Falconer questioned officialdom's complicity, writing: "The readiness of Northern Ireland officialdom to consign taxpayers’ money to a black hole of translations incomprehensible to ordinary users is worrying". Recently produced teaching materials, have, on the other hand, been evaluated more positively.

Of the four peripheral varieties of Scots – the others being Insular, Northern

and Southern Scots – Ulster Scots is the only one whose traditional written form is commonly indistinguishable from the main Central Scots variety.

From The Lammas Fair (Robert Huddleston 1814–1889)

To M.H. (Barney Maglone 1820?–1875)

Ulster-Scots Agency

The Ulster-Scots Agency is a cross-border body in Ireland which seeks "promote the study, conservation and development of Ulster-Scots as a living language; to encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture; and to promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots...

and Ulster-Scots Language Society) generally refers to the dialects of Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

spoken in parts of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

in Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

. Some definitions of Ulster Scots may also include Standard English

Standard English

Standard English refers to whatever form of the English language is accepted as a national norm in an Anglophone country...

spoken with an Ulster Scots accent. This is a situation like that of Lowland Scots and Scottish Standard English

Scottish English

Scottish English refers to the varieties of English spoken in Scotland. It may or may not be considered distinct from the Scots language. It is always considered distinct from Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language....

– where lexical items have been re-allocated to the phoneme

Phoneme

In a language or dialect, a phoneme is the smallest segmental unit of sound employed to form meaningful contrasts between utterances....

classes that are nearest to the equivalent standard classes.

Ulster Scots has been influenced by Mid Ulster English

Mid Ulster English

Mid Ulster English is the dialect of Hiberno-English spoken by most people in the province of Ulster in Ireland. The dialect has been greatly influenced by Ulster Irish, but also by the Scots language, which was brought over by Scottish settlers during the plantations.Mid Ulster English is the main...

and Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the Province of Ulster. The largest Gaeltacht region today is in County Donegal, so that the term Donegal Irish is often used synonymously. Nevertheless, records of the language as it was spoken in other counties do exist, and help provide...

. Ulster Scots has also influenced Mid Ulster English, which is the dialect of most people in Ulster. As a result of the competing influences of English and Scots, varieties

Variety (linguistics)

In sociolinguistics a variety, also called a lect, is a specific form of a language or language cluster. This may include languages, dialects, accents, registers, styles or other sociolinguistic variation, as well as the standard variety itself...

of Ulster Scots can be described as 'more English' or 'more Scots'.

Scots dialects were brought to Ulster during the early 17th century, when large numbers of Scots speakers arrived from Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

during (and following) the Ulster Plantation

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster was the organised colonisation of Ulster—a province of Ireland—by people from Great Britain. Private plantation by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while official plantation controlled by King James I of England and VI of Scotland began in 1609...

. The earliest Scots writing in Ulster dates from that time, and until the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, written Scots from Ulster was almost identical with that of Scotland.

Since the 1990s, new orthographies

Orthography

The orthography of a language specifies a standardized way of using a specific writing system to write the language. Where more than one writing system is used for a language, for example Kurdish, Uyghur, Serbian or Inuktitut, there can be more than one orthography...

have been created, which seek "to be as different to English (and occasionally Scots) as possible". It has been claimed that the recent "Ulster-Scots language and heritage cause has been set rolling only out of a sense of cultural rivalry among some Protestants

Protestantism in Ireland

Protestantism in Ireland- 20th Century decline and other developments:In 1991, the population of the Republic of Ireland was approximately 3% Protestant, but the figure was over 10% in 1891, indicating a fall of 70% in the relative Protestant population over the past century.The effect of...

and unionists

Unionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is an ideology that favours the continuation of some form of political union between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain...

, keen to counter-balance the onward march of the Irish language

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

movement".

Names

While once referred to as Scotch-Irish by several researchers, that has now been superseded by the term Ulster Scots. Native Speakers usually refer to their vernacular as 'braid Scots, 'Scotch’or the 'hamely tongue'. Since the 1980s Ullans, a portmanteau neologism popularized by the physician, amateur historian and politician Dr Ian Adamson

Ian Adamson

Cllr Ian Adamson OBE is a former Lord Mayor of Belfast. He is a member of the Ulster Unionist Party and is a retired medical doctor.A serving Councillor on Belfast City Council from 1989 until 2011, Adamson was Lord Mayor in 1996....

, merging Ulster and Lallans

Lallans

Lallans , a variant of the Modern Scots word lawlands meaning the lowlands of Scotland, was also traditionally used to refer to the Scots language as a whole...

— the Scots for Lowlands — but also an acronym for “Ulster-Scots language in literature and native speech” and Ulstèr-Scotch, the preferred revivalist parlance, have also been used. Occasionally the term Hiberno-Scots is used, although it is usually used for the ethnic group rather than the vernacular.

Speaker population and spread

During the middle of the 20th century, the linguist R. J. Gregg established the geographical boundaries of Ulster's Scots-speaking areas based on information gathered from native speakers.Ulster Scots is spoken in east Antrim

County Antrim

County Antrim is one of six counties that form Northern Ireland, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,844 km², with a population of approximately 616,000...

, north Down

County Down

-Cities:*Belfast *Newry -Large towns:*Dundonald*Newtownards*Bangor-Medium towns:...

, north-east County Londonderry

County Londonderry

The place name Derry is an anglicisation of the old Irish Daire meaning oak-grove or oak-wood. As with the city, its name is subject to the Derry/Londonderry name dispute, with the form Derry preferred by nationalists and Londonderry preferred by unionists...

, the Laggan area of Donegal

County Donegal

County Donegal is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Donegal. Donegal County Council is the local authority for the county...

, and also in the fishing villages of the Mourne coast.

The 1999 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey found that 2% of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

residents claimed to speak Ulster Scots, which would mean a total speech community of approximately 30,000 in the territory. Other estimates range from 35,000 in Northern Ireland, to an "optimistic" total of 100,000 including the Republic of Ireland. Speaking at a seminar on 9 September 2004, Ian Sloan of the Northern Ireland Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

The Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure is a devolved Northern Irish government department in the Northern Ireland Executive...

(DCAL) accepted that the 1999 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey "did not significantly indicate that unionists or nationalists were relatively any more or less likely to speak Ulster Scots, although in absolute terms there were more unionists who spoke Ulster Scots than nationalists".

Status

Enthusiasts such as Philip Robinson, author of "Ulster-Scots: A Grammar of the Traditional Written and Spoken Language", the Ulster-Scots Language Society and supporters of an Ulster-Scots Academy are of the opinion that Ulster Scots is a language in its own right. That position has been criticised by the Ulster-Scots AgencyUlster-Scots Agency

The Ulster-Scots Agency is a cross-border body in Ireland which seeks "promote the study, conservation and development of Ulster-Scots as a living language; to encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture; and to promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots...

, a BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

report stating: "[The Agency] accused the academy of wrongly promoting Ulster-Scots as a language distinct from Scots." A position reflected in many of the Academic responses to the "Public Consultation on Proposals for an Ulster-Scots Academy"

Linguistic status

Among academic linguists Ulster Scots, along with other varieties of Scots, is treated as a dialectDialect

The term dialect is used in two distinct ways, even by linguists. One usage refers to a variety of a language that is a characteristic of a particular group of the language's speakers. The term is applied most often to regional speech patterns, but a dialect may also be defined by other factors,...

of English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

, for example Raymond Hickey, or by others as a variety

Variety (linguistics)

In sociolinguistics a variety, also called a lect, is a specific form of a language or language cluster. This may include languages, dialects, accents, registers, styles or other sociolinguistic variation, as well as the standard variety itself...

of the Scots language

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

, for example Dr. Caroline Macafee, who writes "Ulster Scots is [...] clearly a dialect of Central Scots." And "Ulster Scots is one dialect of Lowland Scots, now officially regarded as a language by the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages

European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages

The European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages is a non-governmental organisation that was set up to promote linguistic diversity and languages. It was founded in 1982...

." The Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

The Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure is a devolved Northern Irish government department in the Northern Ireland Executive...

considers Ulster Scots to be "the local variety of the Scots language."

Using the criteria on Ausbau languages developed by the German linguist Heinz Kloss

Heinz Kloss

Heinz Kloss was a German linguist and internationally recognised authority on linguistic minorities....

, Ulster Scots could qualify only as a Spielart or 'national dialect' of Scots (cf. British and American English), since it does not have the Mindestabstand, or 'minimum divergence' necessary to achieve language status through standardisation and codification.

Legal status

Ulster Scots is defined in an Agreement between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of Ireland establishing implementation bodies done at Dublin on the 8th day of March 1999 in the following terms:The North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999, which gave effect to the implementation bodies incorporated the text of the agreement in its Schedule 1.

The declaration made by the United Kingdom Government regarding the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages is a European treaty adopted in 1992 under the auspices of the Council of Europe to protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe...

reads as follows:

The definition from the North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999 above was used in the 1 July 2005 Second Periodical Report by the United Kingdom to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe outlining how the UK meets its obligations under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

The Good Friday Agreement (which does not refer to Ulster Scots as a "language") also recognises Ulster Scots as "part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland", and the Implementation Agreement established the cross-border Ulster-Scots Agency

Ulster-Scots Agency

The Ulster-Scots Agency is a cross-border body in Ireland which seeks "promote the study, conservation and development of Ulster-Scots as a living language; to encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture; and to promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots...

(Tha Boord o Ulstèr-Scotch). The legislative remit laid down for the agency by the North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999 is: "the promotion of greater awareness and the use of Ullans and of Ulster-Scots cultural issues, both within Northern Ireland and throughout the island". The agency has adopted a mission statement: to promote the study, conservation, development and use of Ulster Scots as a living language; to encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture; and to promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots people.

The Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006 amended the Northern Ireland Act 1998

Northern Ireland Act 1998

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which established a devolved legislature for Northern Ireland, the Northern Ireland Assembly, after decades of direct rule from Westminster....

to insert a section (28D) entitled Strategies relating to Irish language and Ulster Scots language etc. which inter alia laid on the Executive Committee a duty to "adopt a strategy setting out how it proposes to enhance and develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture." This reflects the wording used in the St Andrews Agreement

St Andrews Agreement

The St Andrews Agreement was an agreement between the British and Irish Governments and the political parties in relation to the devolution of power to Northern Ireland...

to refer to the enhancement and development of "the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture".

History and literature

ScotsScottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

, mainly Gaelic-speaking, had been settling in Ulster since the 15th century, but large numbers of Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

-speaking Lowlanders, some 200,000, arrived during the 17th century following the 1610 Plantation

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster was the organised colonisation of Ulster—a province of Ireland—by people from Great Britain. Private plantation by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while official plantation controlled by King James I of England and VI of Scotland began in 1609...

, with the peak reached during the 1690s. In the core areas of Scots settlement, Scots outnumbered English settlers by five or six to one.

Literature from shortly before the end of the unselfconscious tradition at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries is almost identical with contemporary writing from Scotland. W G Lyttle, writing in Paddy McQuillan's Trip Tae Glesco, uses the typically Scots forms kent and begood, now replaced in Ulster by the more mainstream Anglic

Anglic

Anglic can refer to:* Old English and the languages descended from it.* A simplified system of English spelling invented by the Swedish philologist Robert Eugen Zachrisson in 1930....

forms knew, knowed or knawed and begun. Many of the modest contemporary differences between Scots as spoken in Scotland and Ulster may be due to dialect levelling and influence from Mid Ulster English brought about through relatively recent demographic change rather than direct contact

Language contact

Language contact occurs when two or more languages or varieties interact. The study of language contact is called contact linguistics.Multilingualism has likely been common throughout much of human history, and today most people in the world are multilingual...

with Irish, retention of older features or separate development.

The earliest identified writing in Scots in Ulster dates from 1571: a letter from Agnes Campbell of County Tyrone to Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

on behalf of Turlough O'Neil, her husband. Although documents dating from the Plantation period show conservative Scots features, English forms started to predominate from the 1620s as Scots declined as a written medium.

In Ulster Scots-speaking areas there was traditionally a considerable demand for the work of Scottish poets, often in locally printed editions. Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie , Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was one of the principal members of the Castalian Band, a circle of poets in the court of James VI in the 1580s which included the king himself. Montgomerie was for a time in favour as one of the king's...

's The Cherrie and the Slae in 1700, shortly over a decade later an edition of poems by Sir David Lindsay, nine printings of Allan Ramsay's The Gentle shepherd between 1743 and 1793, and an edition of Robert Burns

Robert Burns

Robert Burns was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide...

' poetry in 1787, the same year as the Edinburgh edition, followed by reprints in 1789, 1793 and 1800. Among other Scottish poets published in Ulster were James Hogg

James Hogg

James Hogg was a Scottish poet and novelist who wrote in both Scots and English.-Early life:James Hogg was born in a small farm near Ettrick, Scotland in 1770 and was baptized there on 9 December, his actual date of birth having never been recorded...

and Robert Tannahill

Robert Tannahill

Robert Tannahill was a Scottish poet. Known as the 'Weaver Poet', his music and poetry is contemporaneous with that of Robert Burns.He was born at Castle Street in Paisley on 3 June 1774, the fourth son in a family of seven...

.

That was complemented by a poetry revival and nascent prose genre in Ulster, which started around 1720. The most prominent being the rhyming weaver

Weaver Poets

Weaver Poets, Rhyming Weaver Poets and Ulster Weaver Poets were a collective group of poets belonging to an artistic movement who were both influenced by and contemporaries of Robert Burns and the Romantic movement.-Origins:...

poetry, of which, some 60 to 70 volumes were published between 1750 and 1850, the peak being in the decades 1810 to 1840, although the first printed poetry (in the Habbie stanza

Burns stanza

The Burns stanza is a verse form named after the Scottish poet Robert Burns. It was not, however, invented by Burns, and prior to his use of it was known as the standard Habbie, after the piper Habbie Simpson...

form) by an Ulster Scots writer was published in a broadsheet

Broadsheet

Broadsheet is the largest of the various newspaper formats and is characterized by long vertical pages . The term derives from types of popular prints usually just of a single sheet, sold on the streets and containing various types of material, from ballads to political satire. The first broadsheet...

in Strabane in 1735. These weaver poets looked to Scotland for their cultural and literary models and were not simple imitators but clearly inheritors of the same literary tradition following the same poetic and orthographic practices; it is not always immediately possible to distinguish traditional Scots writing from Scotland and Ulster. Among the rhyming weavers were James Campbell (1758–1818), James Orr

James Orr (poet)

James Orr was a poet or rhyming weaver from Ulster also known as the Bard of Ballycarry, who wrote in English and Ulster Scots. He was the foremost of the Ulster Weaver Poets, and was writing contemporaneously with Robert Burns...

(1770–1816), Thomas Beggs (1749–1847), David Herbison (1800–1880), Hugh Porter (1780–1839) and Andrew McKenzie

Andrew McKenzie

Andrew B. McKenzie was an American physician. He was the first African-American to practice medicine in Tuscaloosa, Alabama....

(1780–1839).

Scots was also used in the narrative by Ulster novelists such as W. G. Lyttle (1844–1896) and Archibald McIlroy (1860–1915). By the middle of the 19th century the Kailyard school

Kailyard school

The Kailyard school of Scottish fiction was developed about the 1890s as a reaction against what was seen as increasingly coarse writing representing Scottish life complete with all its blemishes. It has been considered as being an overly sentimental representation of rural life, cleansed of real...

of prose had become the dominant literary genre, overtaking poetry. This was a tradition shared with Scotland which continued into the early 20th century. Scots also regularly appeared in Ulster newspaper columns, especially in Antrim and Down, in the form of pseudonymous social commentary employing a folksy first-person style. The pseudonymous Bab M'Keen (probably successive members of the Weir family: John Weir, William Weir, and Jack Weir) provided comic commentaries in the Ballymena Observer and County Antrim Advertiser for over a hundred years from the 1880s.

A somewhat diminished tradition of vernacular poetry survived into the 20th century in the work of poets such as Adam Lynn, author of the 1911 collection Random Rhymes frae Cullybackey, John Stevenson (died 1932), writing as "Pat M'Carty", and John Clifford (1900–1983) from East Antrim. In the late 20th century the poetic tradition was revived, albeit often replacing the traditional Modern Scots

Modern Scots

Modern Scots describes the varieties of Scots traditionally spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster from 1700.Throughout its history, Modern Scots has been undergoing a process of language attrition, whereby successive generations of speakers have adopted more and more features from...

orthographic practice with a series of contradictory idiolect

Idiolect

In linguistics, an idiolect is a variety of a language unique to an individual. It is manifested by patterns of vocabulary or idiom selection , grammar, or pronunciations that are unique to the individual. Every individual's language production is in some sense unique...

s. Among the significant writers is James Fenton

James Fenton (Ulster-Scots poet)

James Fenton is a linguist and poet who writes in Ulster Scots.He was born in 1931 and grew up in Drumdarragh and in Ballinaloob, County Antrim. His home language of childhood was Ulster Scots...

, mostly using a blank verse form, but also occasionally the Habbie stanza. He employs an orthography that presents the reader with the difficult combination of eye dialect

Eye dialect

Eye dialect is the use of non-standard spelling for speech to draw attention to pronunciation. The term was originally coined by George P. Krapp to refer to the literary technique of using non-standard spelling that implies a pronunciation of the given word that is actually standard, such as...

, dense Scots, and a greater variety of verse forms than employed hitherto. The poet Michael Longley (born 1939) has experimented with Ulster Scots for the translation of Classical verse, as in his 1995 collection The Ghost Orchid.

Philip Robinson's (born 1946) writing has been described as verging on "post-modern

Postmodern literature

The term Postmodern literature is used to describe certain characteristics of post–World War II literature and a reaction against Enlightenment ideas implicit in Modernist literature.Postmodern literature, like postmodernism as a whole, is hard to define and there is little agreement on the exact...

kailyard". He has produced a trilogy of novels Wake the Tribe o Dan (1998), The Back Streets o the Claw (2000) and The Man frae the Ministry (2005), as well as story books for children Esther, Quaen o tha Ulidian Pechts and Fergus an tha Stane o Destinie, and two volumes of poetry Alang the Shore (2005) and Oul Licht, New Licht (2009).

Since the 1990s

Within the terms of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages the British Government is obliged, among other things, to:

- Facilitate and/or encouragement of the use of Scots in speech and writing, in public and private life.

- Provide appropriate forms and means for the teaching and study of the language at all appropriate stages.

- Provide facilities enabling non-speakers living where the language is spoken to learn it if they so desire.

- Promote study and research of the language at universities of equivalent institutions.

The Ulster-Scots Agency

Ulster-Scots Agency

The Ulster-Scots Agency is a cross-border body in Ireland which seeks "promote the study, conservation and development of Ulster-Scots as a living language; to encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture; and to promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots...

, funded by DCAL in conjunction with the Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs

Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs

The Department of Children and Youth Affairs is a department of the Government of Ireland. It is led by the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs.-Departmental team:...

, is responsible for promotion of greater awareness and use of Ullans and of Ulster-Scots cultural issues, both within Northern Ireland and throughout the island. The agency was established as a result of the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

In 2001 the Institute of Ulster Scots Studies was established at the University of Ulster

University of Ulster

The University of Ulster is a multi-campus, co-educational university located in Northern Ireland. It is the largest single university in Ireland, discounting the federal National University of Ireland...

An Ulster Scots Academy has been planned with the aim of conserving, developing, and teaching the language of Ulster-Scots in association with native speakers to the highest academic standards.

New orthographies

By the early 20th century the literary tradition was almost extinct, though some 'dialect' poetry continued to be written. Much revivalLanguage revival

Language revitalization, language revival or reversing language shift is the attempt by interested parties, including individuals, cultural or community groups, governments, or political authorities, to reverse the decline of a language. If the decline is severe, the language may be endangered,...

ist Ulster Scots has appeared, for example as "official translations", since the 1990s. However, it has little in common with traditional Scots orthography

Orthography

The orthography of a language specifies a standardized way of using a specific writing system to write the language. Where more than one writing system is used for a language, for example Kurdish, Uyghur, Serbian or Inuktitut, there can be more than one orthography...

as described in Grant and Dixon’s Manual of Modern Scots (1921). Aodán Mac Póilin

Aodán Mac Póilin

Aodán Mac Póilin is an Irish language activist in Northern Ireland.He was born in Belfast and lives in the Shaw's Road Irish-speaking community. He graduated from the New University of Ulster with a degree and M.Phil. in Irish studies...

, an Irish language

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

activist, has described these revivalist orthographies as an attempt to make Ulster Scots an independent written language and to achieve official status. They seek "to be as different to English (and occasionally Scots) as possible". He described it as a hotchpotch of obsolete words, neologisms (example: stour-sucker for vacuum cleaner

Vacuum cleaner

A vacuum cleaner, commonly referred to as a "vacuum," is a device that uses an air pump to create a partial vacuum to suck up dust and dirt, usually from floors, and optionally from other surfaces as well. The dirt is collected by either a dustbag or a cyclone for later disposal...

), redundant spellings (example: qoho for who) and "erratic spelling". This spelling "sometimes reflects everyday Ulster Scots speech rather than the conventions of either modern or historic Scots, and sometimes does not". The result, Mac Póilin writes, is "often incomprehensible to the native speaker". In 2000, Dr John Kirk described the "net effect" of that "amalgam of traditional, surviving, revived, changed, and invented features" as an "artificial dialect". He added,

It is certainly not a written version of the vestigial spoken dialect of rural County Antrim, as its activists frequently urge, perpetrating the fallacy that it’s wor ain leid. (Besides, the dialect revivalists claim not to be native speakers of the dialect themselves!). The colloquialness of this new dialect is deceptive, for it is neither spoken nor innate. Traditional dialect speakers find it counter-intuitive and false...

In 2005, Gavin Falconer questioned officialdom's complicity, writing: "The readiness of Northern Ireland officialdom to consign taxpayers’ money to a black hole of translations incomprehensible to ordinary users is worrying". Recently produced teaching materials, have, on the other hand, been evaluated more positively.

Of the four peripheral varieties of Scots – the others being Insular, Northern

Doric dialect

Doric dialect can refer to:*The Doric dialect of Greek*The Doric dialect of Scots...

and Southern Scots – Ulster Scots is the only one whose traditional written form is commonly indistinguishable from the main Central Scots variety.

Sample texts

The Muse Dismissed (Hugh Porter 1780–1839)- Be hush'd my Muse, ye ken the morn

- Begins the shearing o' the corn,

- Whar knuckles monie a risk maun run,

- An' monie a trophy's lost an' won,

- Whar sturdy boys wi' might and main

- Shall camp, till wrists an' thumbs they strain,

- While pithless, pantin' wi' the heat,

- They bathe their weazen'd pelts in sweat

- To gain a sprig o' fading fame,

- Before they taste the dear-bought cream—

- But bide ye there, my pens an' papers,

- For I maun up, an' to my scrapers—

- Yet, min', my lass— ye maun return

- This very night we cut the churn.

From The Lammas Fair (Robert Huddleston 1814–1889)

- Tae sing the day, tae sing the fair,

- That birkies ca' the lammas;

- In aul' Belfast, that toun sae rare,

- Fu' fain wad try't a gomas.

- Tae think tae please a', it were vain,

- And for a country plain boy;

- Therefore, tae please mysel' alane,

- Thus I began my ain way,

-

-

- Tae sing that day.

-

-

- Thus I began my ain way,

- Ae Monday morn on Autumn's verge

- To view a scene so gay,

- I took my seat beside a hedge,

- To loiter by the way.

- Lost Phoebus frae the clouds o' night,

- Ance mair did show his face—

- Ance mair the Emerald Isle got light,

- Wi' beauty, joy, an' grace;

-

- Fu' nice that day.

-

- Wi' beauty, joy, an' grace;

To M.H. (Barney Maglone 1820?–1875)

- This wee thing's o' little value,

- But for a' that it may be

- Guid eneuch to gar you, lassie,

- When you read it, think o' me.

- Think o' whan we met and parted,

- And o' a' we felt atween—

- Whiles sae gleesome, whiles doon-hearted—

- In yon cosy neuk at e'en.

- Think o' when we dander't

- Doon by Bangor and the sea;

- How yon simmer day, we wander't

- 'Mang the fields o' Isle Magee.

- Think o' yon day's gleefu' daffin'

- (Weel I wot ye mind it still)

- Whan we had sic slips and lauchin',

- Spielin' daftly up Cave Hill.

- Dinna let your e'en be greetin'

- Lassie, whan ye think o' me,

- Think upo' anither meetin',

- Aiblins by a lanward sea.

See also

- Scots languageScots languageScots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

- UlsterUlsterUlster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

- Ulster Scots people

- Ulster IrishUlster IrishUlster Irish is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the Province of Ulster. The largest Gaeltacht region today is in County Donegal, so that the term Donegal Irish is often used synonymously. Nevertheless, records of the language as it was spoken in other counties do exist, and help provide...

- Dictionary of the Scots LanguageDictionary of the Scots LanguageThe Dictionary of the Scots Language is an online Scots-English dictionary, now run by Scottish Language Dictionaries Ltd, a charity and limited company...

- History of the Scots languageHistory of the Scots languageThe history of the Scots language refers to how Anglic varieties spoken in parts of Scotland developed into modern Scots.-Origins:Speakers of Northumbrian Old English settled in south eastern Scotland in the 7th century, at which time Celtic Brythonic was spoken in the south of Scotland to a little...

- Languages of Ireland

- Languages in the United KingdomLanguages in the United KingdomThe de facto official language of the United Kingdom is English, which is spoken as the primary language of 95% of the UK population. Welsh is the second most spoken language in the United Kingdom.-Living:...

- W.F. Marshall

- Mid-Ulster English

External links

- BBC Ulster-Scots

- BBC A Kist o Wurds

- BBC Robin's Readings

- The Ulster-Scots Language Society.

- Pronunciation of Ulster Scots.

- Aw Ae Oo (Scots in Scotland and Ulster) and Aw Ae Wey (Written Scots in Scotland and Ulster)

- Listen to an Ulster Scots accent.

- 'Hover & Hear' Ulster Scots pronunciations, and compare with other accents from the UK and around the World.

- Language, Identity and Politics in Northern Ireland.

- Public policy and Scots in Northern Ireland.

- Ulster Scots voices (BBC site)

- Ulster-Scots Online.

- Website promoting Ullans to the Gaelic community of Ireland.