Warren Court

Encyclopedia

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

between 1953 and 1969, when Earl Warren

Earl Warren

Earl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

served as Chief Justice

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

. Warren led a liberal majority that used judicial power in dramatic fashion, to the consternation of conservative opponents. The Warren Court expanded civil rights, civil liberties

Civil liberties

Civil liberties are rights and freedoms that provide an individual specific rights such as the freedom from slavery and forced labour, freedom from torture and death, the right to liberty and security, right to a fair trial, the right to defend one's self, the right to own and bear arms, the right...

, judicial power

Judicial activism

Judicial activism describes judicial ruling suspected of being based on personal or political considerations rather than on existing law. It is sometimes used as an antonym of judicial restraint. The definition of judicial activism, and which specific decisions are activist, is a controversial...

, and the federal power

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

in dramatic ways.

The court was both applauded and criticized for bringing an end to racial segregation in the United States

Racial segregation in the United States

Racial segregation in the United States, as a general term, included the racial segregation or hypersegregation of facilities, services, and opportunities such as housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation along racial lines...

, incorporating

Incorporation (Bill of Rights)

The incorporation of the Bill of Rights is the process by which American courts have applied portions of the U.S. Bill of Rights to the states. Prior to the 1890s, the Bill of Rights was held only to apply to the federal government...

the Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

(i.e. applying it to states

U.S. state

A U.S. state is any one of the 50 federated states of the United States of America that share sovereignty with the federal government. Because of this shared sovereignty, an American is a citizen both of the federal entity and of his or her state of domicile. Four states use the official title of...

), and ending officially sanctioned voluntary prayer in public schools. The period is recognized as a high point in judicial power that has receded ever since, but with a substantial continuing impact.

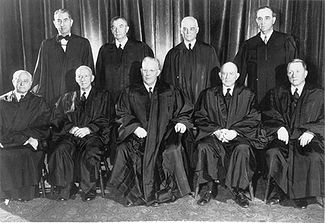

Prominent members of the Court during the Warren era besides the Chief Justice included Justices William J. Brennan, Jr.

William J. Brennan, Jr.

William Joseph Brennan, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1956 to 1990...

, William O. Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

, Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

, Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

, and John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. His namesake was his grandfather John Marshall Harlan, another associate justice who served from 1877 to 1911.Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and...

.

Warren's leadership

One of the primary factors in Warren's leadership was his political background, having served three terms as Governor of CaliforniaGovernor of California

The Governor of California is the chief executive of the California state government, whose responsibilities include making annual State of the State addresses to the California State Legislature, submitting the budget, and ensuring that state laws are enforced...

and experience as the Republican candidate for vice president in 1948. Warren brought a strong belief in the remedial power of law. According to Bernard Schwartz, Warren's view of the law was pragmatic, seeing it as an instrument for obtaining equity

Justice

Justice is a concept of moral rightness based on ethics, rationality, law, natural law, religion, or equity, along with the punishment of the breach of said ethics; justice is the act of being just and/or fair.-Concept of justice:...

and fairness. Schwartz argues that Warren's approach was most effective "when the political institutions had defaulted on their responsibility to try to address problems such as segregation and reapportionment and cases where the constitutional rights of defendants were abused."

A related component of Warren's leadership was his focus on broad ethical principles, rather than narrower interpretative structures. Describing the latter as "conventional reasoning patterns," Professor Mark Tushnet

Mark Tushnet

Mark Victor Tushnet is the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. A prominent scholar of constitutional law and legal history, he is the author of many books and articles.-Career:...

suggests Warren often disregarded these in groundbreaking cases such as Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

, Reynolds v. Sims

Reynolds v. Sims

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 was a United States Supreme Court case that ruled that state legislature districts had to be roughly equal in population.-Facts:...

and Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona, , was a landmark 5–4 decision of the United States Supreme Court. The Court held that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant...

, where such traditional sources of precedent were stacked against him. Tushnet suggests Warren's principles "were philosophical, political, and intuitive, not legal in the conventional technical sense."

Warren's leadership was characterized by remarkable consensus on the court, particularly in some of the most controversial cases. These included Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainwright

Gideon v. Wainwright

Gideon v. Wainwright, , is a landmark case in United States Supreme Court history. In the case, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who are unable to afford their own...

, and Cooper v. Aaron

Cooper v. Aaron

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 , was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which held that the states were bound by the Court's decisions, and could not choose to ignore them.-Background of the case:...

, which were unanimously decided, as well as Abington School District v. Schempp

Abington School District v. Schempp

Abington Township School District v. Schempp , 374 U.S. 203 , was a United States Supreme Court case argued on February 27–28, 1963 and decided on June 17, 1963...

and Engel v. Vitale

Engel v. Vitale

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that determined that it is unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and require its recitation in public schools....

, each striking down religious recitations in schools with only one dissent. In an unusual action, the decision in Cooper was personally signed by all nine justices, with the three new members of the Court adding that they supported and would have joined the Court's decision in Brown v. Board.

Vision

Professor John Hart ElyJohn Hart Ely

John Hart Ely is one of the most widely-cited legal scholars in United States history, ranking just after Richard Posner, Ronald Dworkin, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., according to a 2000 study in the University of Chicago's Journal of Legal Studies.-Biography:Born in New York City, John Hart...

in his book Democracy and Distrust famously characterized the Warren Court as a "Carolene Products Court." This referred to the famous Footnote Four in United States v. Carolene Products in which the Supreme Court had suggested that heightened judicial scrutiny might be appropriate in three types of cases: those where a law was challenged as a deprivation of a specifically enumerated right (such as a challenge to a law because it denies "freedom of speech," a phrase specifically included in the Bill of Rights); those where a challenged law made it more difficult to achieve change through normal political processes; and those where a law impinged on the rights of "discrete and insular minorities." The Warren Court's doctrine may be seen as proceeding aggressively in these general areas: its aggressive reading of the first eight amendments in the Bill of Rights (as "incorporated" against the states by the Fourteenth Amendment); its commitment to unblocking the channels of political change ("one-man, one-vote"), and its vigorous protection of the rights of racial minority groups. The Warren Court, while in many cases taking a broad view of individual rights, generally declined to read the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment broadly, outside of the incorporation context (see Ferguson v. Skrupa

Ferguson v. Skrupa

Ferguson v. Skrupa was a case before the United States Supreme Court regarding the constitutionality of prohibiting debt adjustment.-Background:...

, but see also Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut, , was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. The case involved a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraceptives...

). The Warren Court's decisions were also strongly nationalist in thrust, as the Court read Congress's power under the Commerce Clause quite broadly and often expressed an unwillingness to allow constitutional rights to vary from state to state (as was explicitly manifested in Cooper v. Aaron

Cooper v. Aaron

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 , was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which held that the states were bound by the Court's decisions, and could not choose to ignore them.-Background of the case:...

).

Professor Rebecca Zietlow argues that the Warren Court brought an expansion in the "rights of belonging," which she characterizes as "rights that promote an inclusive vision of who belongs to the national community and facilitate equal membership in that community." Zietlow notes that both critics and supporters of the Warren Court attribute to it this shift, whether as a matter of imposing its countermajoritarian will or as protecting the rights of minorities. Zietlow also challenges the notion of the Warren Court as "activist," noting that even at its height the Warren Court only invalidated 17 acts of Congress between 1962 and 1969, as compared to the more "conservative" Rehnquist Court which struck down 33 acts of Congress between 1995 and 2003.

Historically significant decisions

Important decisions during the Warren Court years included decisions holding segregationRacial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

policies in public schools (Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

) and anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws, also known as miscegenation laws, were laws that enforced racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different races...

unconstitutional (Loving v. Virginia

Loving v. Virginia

Loving v. Virginia, , was a landmark civil rights case in which the United States Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, declared Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute, the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924", unconstitutional, thereby overturning Pace v...

); ruling that the Constitution protects a general right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut, , was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. The case involved a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraceptives...

); that states are bound by the decisions of the Supreme Court and cannot ignore them (Cooper v. Aaron

Cooper v. Aaron

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 , was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which held that the states were bound by the Court's decisions, and could not choose to ignore them.-Background of the case:...

); that public schools cannot have official prayer (Engel v. Vitale

Engel v. Vitale

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that determined that it is unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and require its recitation in public schools....

) or mandatory Bible readings (Abington School District v. Schempp

Abington School District v. Schempp

Abington Township School District v. Schempp , 374 U.S. 203 , was a United States Supreme Court case argued on February 27–28, 1963 and decided on June 17, 1963...

); the scope of the doctrine of incorporation (Mapp v. Ohio

Mapp v. Ohio

Mapp v. Ohio, , was a landmark case in criminal procedure, in which the United States Supreme Court decided that evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects against "unreasonable searches and seizures," may not be used in criminal prosecutions in state courts, as well as...

, Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona, , was a landmark 5–4 decision of the United States Supreme Court. The Court held that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant...

) was dramatically increased; reading an equal protection clause into the Fifth Amendment

Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights, protects against abuse of government authority in a legal procedure. Its guarantees stem from English common law which traces back to the Magna Carta in 1215...

(Bolling v. Sharpe

Bolling v. Sharpe

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court case which deals with civil rights, specifically, segregation in the District of Columbia's public schools. Originally argued on December 10–11, 1952, a year before Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S...

); holding that the states may not apportion a chamber of their legislatures in the manner in which the United States Senate is apportioned (Reynolds v. Sims

Reynolds v. Sims

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 was a United States Supreme Court case that ruled that state legislature districts had to be roughly equal in population.-Facts:...

); and holding that the Constitution requires active compliance (Gideon v. Wainwright

Gideon v. Wainwright

Gideon v. Wainwright, , is a landmark case in United States Supreme Court history. In the case, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who are unable to afford their own...

).

- Racial segregationRacial segregationRacial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

: Brown v. Board of EducationBrown v. Board of EducationBrown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

, Bolling v. SharpeBolling v. SharpeBolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court case which deals with civil rights, specifically, segregation in the District of Columbia's public schools. Originally argued on December 10–11, 1952, a year before Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S...

, Cooper v. AaronCooper v. AaronCooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 , was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which held that the states were bound by the Court's decisions, and could not choose to ignore them.-Background of the case:...

, Gomillion v. LightfootGomillion v. LightfootGomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 , was a United States Supreme Court decision that found an electoral district created to disenfranchise blacks violated the Fifteenth Amendment.- Decision :...

, Griffin v. County School BoardGriffin v. County School BoardGriffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 , is a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in which it ruled that the County School Board of Prince Edward County's decision to close all local, public schools and provide vouchers to attend private schools were...

, Green v. School Board of New Kent County, Lucy v. AdamsLucy v. AdamsLucy v. Adams, , was a U.S. Supreme Court case that successfully established the right of all citizens to be accepted as students at the University of Alabama....

, Loving v. VirginiaLoving v. VirginiaLoving v. Virginia, , was a landmark civil rights case in which the United States Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, declared Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute, the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924", unconstitutional, thereby overturning Pace v... - VotingVotingVoting is a method for a group such as a meeting or an electorate to make a decision or express an opinion—often following discussions, debates, or election campaigns. It is often found in democracies and republics.- Reasons for voting :...

, redistrictingRedistrictingRedistricting is the process of drawing United States electoral district boundaries, often in response to population changes determined by the results of the decennial census. In 36 states, the state legislature has primary responsibility for creating a redistricting plan, in many cases subject to...

, and malapportionmentApportionment (politics)Apportionment is the process of allocating political power among a set of principles . In most representative governments, political power has most recently been apportioned among constituencies based on population, but there is a long history of different approaches.The United States Constitution,...

: Baker v. CarrBaker v. CarrBaker v. Carr, , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that retreated from the Court's political question doctrine, deciding that redistricting issues present justiciable questions, thus enabling federal courts to intervene in and to decide reapportionment cases...

, Reynolds v. SimsReynolds v. SimsReynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 was a United States Supreme Court case that ruled that state legislature districts had to be roughly equal in population.-Facts:...

, Wesberry v. SandersWesberry v. SandersWesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 was a U.S. Supreme Court case involving U.S. Congressional districts in the state of Georgia. The Court issued its ruling on February 17, 1964. This decision requires each state to draw its U.S... - Criminal procedureCriminal procedureCriminal procedure refers to the legal process for adjudicating claims that someone has violated criminal law.-Basic rights:Currently, in many countries with a democratic system and the rule of law, criminal procedure puts the burden of proof on the prosecution – that is, it is up to the...

: Brady v. MarylandBrady v. MarylandBrady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 , was a United States Supreme Court case in which the prosecution had withheld from the criminal defendant certain evidence. The defendant challenged his conviction, arguing it had been contrary to the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United...

, Mapp v. OhioMapp v. OhioMapp v. Ohio, , was a landmark case in criminal procedure, in which the United States Supreme Court decided that evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects against "unreasonable searches and seizures," may not be used in criminal prosecutions in state courts, as well as...

, Miranda v. ArizonaMiranda v. ArizonaMiranda v. Arizona, , was a landmark 5–4 decision of the United States Supreme Court. The Court held that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant...

, Escobedo v. IllinoisEscobedo v. IllinoisEscobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 , was a United States Supreme Court case holding that criminal suspects have a right to counsel during police interrogations under the Sixth Amendment. The case was decided a year after the court held in Gideon v...

, Gideon v. WainwrightGideon v. WainwrightGideon v. Wainwright, , is a landmark case in United States Supreme Court history. In the case, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who are unable to afford their own...

, Katz v. United StatesKatz v. United StatesKatz v. United States, , is a United States Supreme Court case discussing the nature of the "right to privacy" and the legal definition of a "search." The Court’s ruling adjusted previous interpretations of the unreasonable search and seizure clause of the Fourth Amendment to count immaterial...

, Terry v. OhioTerry v. OhioTerry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 , was a decision by the United States Supreme Court which held that the Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures is not violated when a police officer stops a suspect on the street and frisks him without probable cause to arrest, if the police...

- Free speech: New York Times Co. v. SullivanNew York Times Co. v. SullivanNew York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 , was a United States Supreme Court case which established the actual malice standard which has to be met before press reports about public officials or public figures can be considered to be defamation and libel; and hence allowed free reporting of the...

, Brandenburg v. OhioBrandenburg v. OhioBrandenburg v. Ohio, , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case based on the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It held that government cannot punish inflammatory speech unless it is directed to inciting and likely to incite imminent lawless action...

, Yates v. United StatesYates v. United StatesYates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 , was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States involving free speech and congressional power...

, Roth v. United StatesRoth v. United StatesRoth v. United States, , along with its companion case, Alberts v. California, was a landmark case before the United States Supreme Court which redefined the Constitutional test for determining what constitutes obscene material unprotected by the First Amendment.- Prior history :Under the common...

, Jacobellis v. OhioJacobellis v. OhioJacobellis v. Ohio, , was a United States Supreme Court decision handed down in 1964 involving whether the state of Ohio could, consistent with the First Amendment, ban the showing of a French film called The Lovers which the state had deemed obscene.Nico Jacobellis, manager of the Heights Art...

, Memoirs v. Massachusetts, Tinker v. Des Moines School District - Establishment Clause: Engel v. VitaleEngel v. VitaleEngel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that determined that it is unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and require its recitation in public schools....

, Abington School District v. SchemppAbington School District v. SchemppAbington Township School District v. Schempp , 374 U.S. 203 , was a United States Supreme Court case argued on February 27–28, 1963 and decided on June 17, 1963... - Free Exercise Clause: Sherbert v. VernerSherbert v. VernerSherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 , was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment required that government demonstrate a compelling government interest before denying unemployment compensation to someone who was fired because her...

- Right to privacy and reproductive rightsReproductive rightsReproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights as follows:...

: Griswold v. ConnecticutGriswold v. ConnecticutGriswold v. Connecticut, , was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. The case involved a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraceptives... - Cruel and unusual punishmentCruel and unusual punishmentCruel and unusual punishment is a phrase describing criminal punishment which is considered unacceptable due to the suffering or humiliation it inflicts on the condemned person...

: Trop v. DullesTrop v. DullesTrop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 , was a federal case in the United States in which the Supreme Court ruled, 5-4, that it was unconstitutional for the government to revoke the citizenship of a U.S...

, Robinson v. CaliforniaRobinson v. CaliforniaRobinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 , was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the use of civil imprisonment as punishment solely for the misdemeanor crime of addiction to a controlled substance was a violation of the Eighth Amendment's protection against cruel and...

Warren's role

Warren took his seat January 11, 1954 on a recess appointment; the Senate confirmed him six weeks later. Despite his lack of judicial experience, his years in the Alameda County district attorney's office and as state attorney general gave him far more knowledge of the law in practice than most other members of the Court had. Warren's greatest asset, what made him in the eyes of many of his admirers "Super Chief," was his political skill in manipulating the other justices. Over the years his ability to lead the Court, to forge majorities in support of major decisions, and to inspire liberal forces around the nation, outweighed his intellectual weaknesses. Warren realized his weakness and asked the senior associate justice, Hugo L. Black, to preside over conferences until he became accustomed to the drill. A quick study, Warren soon was in fact as well as in name the Court's chief justice.All the justices had been appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

or Truman, and all were committed New Deal liberals

New Deal coalition

The New Deal Coalition was the alignment of interest groups and voting blocs that supported the New Deal and voted for Democratic presidential candidates from 1932 until the late 1960s. It made the Democratic Party the majority party during that period, losing only to Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952...

. They disagreed about the role that the courts should play in achieving liberal goals. The Court was split between two warring factions. Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

and Robert H. Jackson

Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson was United States Attorney General and an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court . He was also the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials...

led one faction, which insisted upon judicial self-restraint and insisted courts should defer to the policymaking prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

and William O. Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

led the opposing faction that agreed the court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy, but felt the judicial agenda had been transformed from questions of property rights to those of individual liberties, and in this area courts should play a more central role. Warren's belief that the judiciary must seek to do justice, placed him with the latter group, although he did not have a solid majority until after Frankfurter's retirement in 1962.

Decisions

Warren was a more liberal justice than anyone had anticipated. Warren was able to craft a long series of landmark decisions because he built a winning coalition. When Frankfurter retired in 1962 and President John F. KennedyJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

named labor union lawyer Arthur Goldberg

Arthur Goldberg

Arthur Joseph Goldberg was an American statesman and jurist who served as the U.S. Secretary of Labor, Supreme Court Justice and Ambassador to the United Nations.-Early life:...

to replace him, Warren finally had the fifth vote for his liberal majority. William J. Brennan, Jr.

William J. Brennan, Jr.

William Joseph Brennan, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1956 to 1990...

, a liberal Democrat appointed by Eisenhower in 1956, was the intellectual leader of the faction that included Black and Douglas. Brennan complemented Warren's political skills with the strong legal skills Warren lacked. Warren and Brennan met before the regular conferences to plan out their strategy.

Brown (1954)

Brown v. Board of EducationBrown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

banned the segregation of public schools.

The very first case put Warren's leadership skills to an extraordinary test. The Legal Defense Fund of the NAACP (a small legal group separate from the much better known NAACP) had been waging a systematic legal fight against the "separate but equal" doctrine enunciated in Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

(1896) and finally had challenged Plessy in a series of five related cases, which had been argued before the Court in the spring of 1953. However the justices had been unable to decide the issue and asked to rehear the case in fall 1953, with special attention to whether the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause prohibited the operation of separate public schools for whites and blacks.

While all but one justice personally rejected segregation, the self-restraint faction questioned whether the Constitution gave the Court the power to order its end. Warren's faction believed the Fourteenth Amendment did give the necessary authority and were pushing to go ahead. Warren, who held only a recess appointment, held his tongue until the Senate, dominated by southerners, confirmed his appointment. Warren told his colleagues after oral argument that he believed segregation violated the Constitution and that only if one considered African Americans inferior to whites could the practice be upheld. But he did not push for a vote. Instead, he talked with the justices and encouraged them to talk with each other as he sought a common ground on which all could stand. Finally he had eight votes, and the last holdout, Stanley Reed

Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed was a noted American attorney who served as United States Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938 and as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He was the last Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school Stanley Forman Reed (December 31,...

of Kentucky, agreed to join the rest. Warren drafted the basic opinion in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and kept circulating and revising it until he had an opinion endorsed by all the members of the Court.

The unanimity Warren achieved helped speed the drive to desegregate public schools, which came about under President Richard M. Nixon. Throughout his years as Chief, Warren succeeded in keeping all decisions concerning segregation unanimous. Brown applied to schools, but soon the Court enlarged the concept to other state actions, striking down racial classification in many areas. Congress ratified the process in the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States that outlawed major forms of discrimination against African Americans and women, including racial segregation...

and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Warren did compromise by agreeing to Frankfurter's demand that the Court go slowly in implementing desegregation; Warren used Frankfurter's suggestion that a 1955 decision (Brown II) include the phrase "all deliberate speed."

The Brown decision of 1954 marked, in dramatic fashion, the radical shift in the Court's--and the nation's--priorities from issues of property rights to civil liberties. Under Warren the courts became an active partner in governing the nation, although still not coequal. Warren never saw the courts as a backward-looking branch of government.

The Brown decision was a powerful moral statement clad in a weak constitutional analysis. His biographer concludes, "If Warren had not been on the Court, the Brown decision might not have been unanimous and might not have generated a moral groundswell that was to contribute to the emergence of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Warren was never a legal scholar on a par with Frankfurter or a great advocate of particular doctrines, as were Black and Douglas. Instead, he believed that in all branches of government common sense, decency, and elemental justice were decisive, not stare decisis, tradition or the text of the Constitution. He wanted results. He never felt that doctrine alone should be allowed to deprive people of justice. He felt racial segregation was simply wrong, and Brown, whatever its doctrinal defects, remains a landmark decision primarily because of Warren's majestic interpretation of the equal protection clause to mean that children should not be shunted to a separate world reserved for minorities.

Reapportionment

The one man, one vote cases (Baker v. CarrBaker v. Carr

Baker v. Carr, , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that retreated from the Court's political question doctrine, deciding that redistricting issues present justiciable questions, thus enabling federal courts to intervene in and to decide reapportionment cases...

and Reynolds v. Sims

Reynolds v. Sims

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 was a United States Supreme Court case that ruled that state legislature districts had to be roughly equal in population.-Facts:...

) of 1962–1964, had the effect of ending the over-representation of rural areas in state legislatures, as well as the under-representation of suburbs. Central cities--which had long been underepresented--were now losing population to the suburbs and were not greatly affected.

Warren's priority on fairness shaped other major decisions. In 1962, over the strong objections of Frankfurter, the Court agreed that questions regarding malapportionment in state legislatures were not political issues, and thus were not outside the Court's purview. For years underpopulated rural areas had deprived metropolitan centers of equal representation in state legislatures. In Warren's California, Los Angeles County had only one state senator. Cities had long since passed their peak, and now it was the middle class suburbs that were underepresented. Frankfurter insisted that the Court should avoid this "political thicket" and warned that the Court would never be able to find a clear formula to guide lower courts in the rash of lawsuits sure to follow. But Douglas found such a formula: "one man, one vote."

In the key apportionment case Reynolds v. Sims (1964) Warren delivered a civics lesson: "To the extent that a citizen's right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen," Warren declared. "The weight of a citizen's vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives. This is the clear and strong command of our Constitution's Equal Protection Clause." Unlike the desegregation cases, in this instance, the Court ordered immediate action, and despite loud outcries from rural legislators, Congress failed to reach the two-thirds needed pass a constitutional amendment. The states complied, reapportioned their legislatures quickly and with minimal troubles. Numerous commentators have concluded reapportionment was the Warren Court's great "success" story.

Due process and rights of defendants (1963-66)

In Gideon v. WainwrightGideon v. Wainwright

Gideon v. Wainwright, , is a landmark case in United States Supreme Court history. In the case, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who are unable to afford their own...

, the Court held that the Sixth Amendment

Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution is the part of the United States Bill of Rights which sets forth rights related to criminal prosecutions...

required that all indigent criminal defendants receive publicly-funded counsel (Florida law at that time required the assignment of free counsel to indigent defendants only in capital cases);

Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona

Miranda v. Arizona, , was a landmark 5–4 decision of the United States Supreme Court. The Court held that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant...

, required that certain rights of a person interrogated while in police custody be clearly explained, including the right to an attorney (often called the "Miranda warning

Miranda warning

The Miranda warning is a warning given by police in the United States to criminal suspects in police custody before they are interrogated to preserve the admissibility of their statements against them in criminal proceedings. In Miranda v...

").

While most Americans eventually agreed that the Court's desegregation and apportionment decisions were fair and right, disagreement about the "due process revolution" continues into the 21st century. Warren took the lead in criminal justice; despite his years as a tough prosecutor, always insisted that the police must play fair or the accused should go free. Warren was privately outraged at what he considered police abuses that ranged from warrantless searches to forced confessions.

Warren’s Court ordered lawyers for indigent defendants, in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), and prevented prosecutors from using evidence seized in illegal searches, in Mapp v. Ohio (1961). The famous case of Miranda v. Arizona (1966) summed up Warren's philosophy. Everyone, even one accused of crimes, still enjoyed constitutionally protected rights, and the police had to respect those rights and issue a specific warning when making an arrest. Warren did not believe in coddling criminals; thus in Terry v. Ohio (1968) he gave police officers leeway to stop and frisk those they had reason to believe held weapons.

Conservatives angrily denounced the "handcuffing of the police." Violent crime and homicide rates shot up nationwide in the following years; in New York City, for example, after steady to declining trends until the early 1960s, the homicide rate doubled in the period from 1964-74 from just under 5 per 100,000 at the beginning of that period to just under 10 per 100,000 in 1974. Controversy exists about the cause, with conservatives blaming the Court decisions, and liberals pointing to the demographic boom and increased urbanization and income inequality characteristic of that era.

After 1992 the homicide rates fell sharply.

First Amendment

The Warren Court also sought to expand the scope of application of the First Amendment. The Court's decision outlawing mandatory school prayer in Engel v. Vitale (1962) brought vehement complaints by conservatives that echoed into the 21st century.Warren worked to nationalize the Bill of Rights

Bill of rights

A bill of rights is a list of the most important rights of the citizens of a country. The purpose of these bills is to protect those rights against infringement. The term "bill of rights" originates from England, where it referred to the Bill of Rights 1689. Bills of rights may be entrenched or...

by applying it to the states. Moreover, in one of the landmark cases decided by the Court, Griswold v. Connecticut (1963), the Warren Court affirmed a constitutionally protected right of privacy, emanating from the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, also known as substantive due process.

This decision was fundamental, after Warren's retirement, for the outcome of Roe v. Wade

Roe v. Wade

Roe v. Wade, , was a controversial landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court on the issue of abortion. The Court decided that a right to privacy under the due process clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution extends to a woman's decision to have an abortion,...

and consequent legalization of abortion.

With the exception of the desegregation decisions, few decisions were unanimous. The eminent scholar Justice John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan was a Kentucky lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court. He is most notable as the lone dissenter in the Civil Rights Cases , and Plessy v...

took Frankfurter's place as the Court's self-constraint spokesman, often joined by Potter Stewart

Potter Stewart

Potter Stewart was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. During his tenure, he made, among other areas, major contributions to criminal justice reform, civil rights, access to the courts, and Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.-Education:Stewart was born in Jackson, Michigan,...

and Byron R. White. But with the appointment of Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from October 1967 until October 1991...

, the first black justice, and Abe Fortas

Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas was a U.S. Supreme Court associate justice from 1965 to 1969. Originally from Tennessee, Fortas became a law professor at Yale, and subsequently advised the Securities and Exchange Commission. He then worked at the Interior Department under Franklin D...

(replacing Goldberg), Warren could count on six votes in most cases.

Associate justices of the Warren Court

- Hugo BlackHugo BlackHugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

- Stanley Forman ReedStanley Forman ReedStanley Forman Reed was a noted American attorney who served as United States Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938 and as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He was the last Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school Stanley Forman Reed (December 31,...

- Felix FrankfurterFelix FrankfurterFelix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

- William O. DouglasWilliam O. DouglasWilliam Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

- Robert H. JacksonRobert H. JacksonRobert Houghwout Jackson was United States Attorney General and an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court . He was also the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials...

- Harold Hitz BurtonHarold Hitz BurtonHarold Hitz Burton was an American politician and lawyer.He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was known as a dispassionate jurist who prized equal justice under the law.-Biography:He...

- Tom C. ClarkTom C. ClarkThomas Campbell Clark was United States Attorney General from 1945 to 1949 and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States .- Early life and career :...

- Sherman MintonSherman MintonSherman "Shay" Minton was a Democratic United States Senator from Indiana and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was the most educated justice during his time on the Supreme Court, having attended Indiana University, Yale and the Sorbonne...

- John Marshall Harlan IIJohn Marshall Harlan IIJohn Marshall Harlan was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. His namesake was his grandfather John Marshall Harlan, another associate justice who served from 1877 to 1911.Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and...

- William J. Brennan, Jr.William J. Brennan, Jr.William Joseph Brennan, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1956 to 1990...

- Charles Evans WhittakerCharles Evans WhittakerCharles Evans Whittaker was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1957 to 1962.-Early years:...

- Potter StewartPotter StewartPotter Stewart was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. During his tenure, he made, among other areas, major contributions to criminal justice reform, civil rights, access to the courts, and Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.-Education:Stewart was born in Jackson, Michigan,...

- Byron WhiteByron WhiteByron Raymond "Whizzer" White won fame both as a football halfback and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Appointed to the court by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, he served until his retirement in 1993...

- Arthur GoldbergArthur GoldbergArthur Joseph Goldberg was an American statesman and jurist who served as the U.S. Secretary of Labor, Supreme Court Justice and Ambassador to the United Nations.-Early life:...

- Abe FortasAbe FortasAbraham Fortas was a U.S. Supreme Court associate justice from 1965 to 1969. Originally from Tennessee, Fortas became a law professor at Yale, and subsequently advised the Securities and Exchange Commission. He then worked at the Interior Department under Franklin D...

- Thurgood MarshallThurgood MarshallThurgood Marshall was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from October 1967 until October 1991...

See also

- Earl WarrenEarl WarrenEarl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

- Supreme Court of the United StatesSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

- History of the Supreme Court of the United StatesHistory of the Supreme Court of the United StatesThe following is a history of the Supreme Court of the United States, organized by Chief Justice. The Supreme Court of the United States is the only court specifically established by the Constitution of the United States, implemented in 1789; under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Court was to be...

- Living ConstitutionLiving ConstitutionThe Living Constitution is a concept in America, also referred to as loose constructionism, constitutional interpretation which claims that the Constitution has a dynamic meaning or that it has the properties of a human in the sense that it changes...

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

Further reading

- Atkins, Burton M. and Terry Sloope. "The 'New' Hugo Black and the Warren Court," Polity, Apr 1986, Vol. 18#4 pp 621-637; argues that in the 1960s Black moved to the right on cases involving civil liberties, civil rights, and economic liberalism.

- Ball, Howard, and Phillip Cooper. "Fighting Justices: Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas and Supreme Court Conflict," American Journal of Legal History, Jan 1994, Vol. 38#1 pp 1-37

- Belknap, Michal, The Supreme Court Under Earl Warren, 1953-1969 (2005), 406pp excerpt and text search

- Eisler, Kim Isaac. The Last Liberal: Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. and the Decisions That Transformed America (2003)

- Hockett, Jeffrey D. "Justices Frankfurter and Black: Social Theory and Constitutional Interpretation," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 107#3 (1992), pp. 479-499 in JSTOR

- Horwitz, Morton J. The Warren Court and the Pursuit of Justice (1999) excerpt and text search

- Lewis, Anthony. "Earl Warren" in Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Volume: 4. (1997) pp 1373-1400; includes all members of the Warren Court. online edition

- Marion, David E. The Jurisprudence of Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. (1997)

- Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (2001) online edition

- Powe, Lucas A.. The Warren Court and American Politics (2002) excerpt and text search

- Scheiber, Harry N. Earl Warren and the Warren Court: The Legacy in American and Foreign Law (2006)

- Schwartz, Bernard. The Warren Court: A Retrospective (1996) excerpt and text search

- Schwartz, Bernard. "Chief Justice Earl Warren: Super Chief in Action." Journal of Supreme Court History 1998 (1): 112-132

- Silverstein, Mark. Constitutional Faiths: Felix Frankfurter, Hugo Black, and the Process of Judicial Decision Making (1984)

- Tushnet, Mark. The Warren Court in Historical and Political Perspective (1996) excerpt and text search

- Urofsky, Melvin I. "William O. Douglas and Felix Frankfurter: Ideology and Personality on the Supreme Court," History Teacher, Nov 1990, Vol. 24#1 pp 7-18

- Wasby, Stephen L. "Civil Rights and the Supreme Court: A Return of the Past," National Political Science Review, July 1993, Vol. 4, pp 49-60

- White, G. Edward. Earl Warren (1982), biography by a leading scholar

External links

- The Legacy of the Warren Court, Time Magazine, 4 July 1969