William Perkin

Encyclopedia

Sir William Henry Perkin, FRS (12 March 1838 14 July 1907) was an English

chemist

best known for his discovery, at the age of 18, of the first aniline

dye, mauveine

.

, the youngest of the seven children of George Perkin, a successful carpenter. His mother, Sarah, was of Scottish

descent but moved to east London as a child. He was baptised in the parish church of St Paul's, Shadwell

, which had been connected to such luminaries as James Cook

, Jane Randolph Jefferson

(mother of Thomas Jefferson

) and John Wesley

.

At the age of 14, Perkin attended the City of London School

, where he was taught by Thomas Hall, who fostered his scientific talent and encouraged him to pursue a career in chemistry.

in London (now part of Imperial College London

), where he began his studies under August Wilhelm von Hofmann

. At this time, chemistry was still in a quite primitive state: although the atomic theory was accepted, the major elements had been discovered, and techniques to analyse the proportions of the elements in many compounds were in place, it was still a difficult proposition to determine the arrangement of the elements in compounds. Hofmann had published a hypothesis on how it might be possible to synthesise quinine

, an expensive natural substance much in demand for the treatment of malaria

. Perkin, who had by then become one of Hofmann's assistants, embarked on a series of experiments to try to achieve this end. During the Easter

vacation in 1856, while Hofmann was visiting his native Germany, Perkin performed some further experiments in the crude laboratory in his apartment on the top floor of his home in Cable Street

in east London. It was here that he made his great discovery: that aniline

could be partly transformed into a crude mixture which when extracted with alcohol produced a substance with an intense purple colour. Perkin, who had an interest in painting and photography, immediately became enthusiastic about this result and carried out further trials with his friend Arthur Church and his brother Thomas. Since these experiments were not part of the work on quinine which had been assigned to Perkin, the trio carried them out in a hut in Perkin's garden, so as to keep them secret from Hofmann.

They satisfied themselves that they might be able to scale up production of the purple substance and commercialise it as a dye, which they called mauveine

. Their initial experiments indicated that it dyed silk in a way which was stable when washed or exposed to light. They sent some samples to a dye works in Perth, Scotland

, and received a very promising reply from the general manager of the company, Robert Pullar. Perkin filed for a patent

in August 1856, when he was still only 18. At the time, all dyes used for colouring cloth were natural substances, many of which were expensive and labour-intensive to extract. Furthermore, many lacked stability, or fastness. The colour purple, which had been a mark of aristocracy and prestige since ancient times, was especially expensive and difficult to produce — the dye used, known as Tyrian purple

, was made from the glandular mucus of certain molluscs. Its extraction was variable and complicated, and so Perkin and his brother realised that they had discovered a possible substitute whose production could be commercially successful.

Perkin could not have chosen a better time or place for his discovery: England was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution

, largely driven by advances in the production of textiles; the science of chemistry had advanced to the point where it could have a major impact on industrial processes; and coal tar

, the major source of his raw material, was an abundant by-product of the process for making coal gas

and coke

.

Having invented the dye, Perkin was still faced with the problems of raising the capital for producing it, manufacturing it cheaply, adapting it for use in dyeing cotton, gaining acceptance for it among commercial dyers, and creating public demand for it. However, he was active in all of these areas: he persuaded his father to put up the capital, and his brothers to partner him in the creation of a factory; he invented a mordant for cotton; he gave technical advice to the dyeing industry; and he publicised his invention of the dye. Public demand was increased when a similar colour was adopted by Queen Victoria

in England and by Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, in France, and when the crinoline

or hooped-skirt, whose manufacture used a large quantity of cloth, became fashionable. Everything seemed to fall into place by dint of hard work, with a little luck, too. Perkin became rich.

After the discovery of mauveine, many new aniline dyes appeared (some discovered by Perkin himself), and factories producing them were constructed across Europe.

William Perkin continued active research in organic chemistry for the rest of his life: he discovered and marketed other synthetic dyes, including Britannia Violet and Perkin's Green ; he discovered ways to make coumarin

William Perkin continued active research in organic chemistry for the rest of his life: he discovered and marketed other synthetic dyes, including Britannia Violet and Perkin's Green ; he discovered ways to make coumarin

, one of the first synthetic perfume

raw materials, and cinnamic acid

. (The reaction used to make the latter became known as the Perkin reaction

.) Local lore has it that the colour of the nearby Grand Union Canal

changed from week to week depending on the activity at Perkin's Greenford

dyeworks. In 1869, Perkin found a method for the commercial production from anthracene

of the brilliant red dye alizarin

, which had been isolated and identified from madder

root some forty years earlier in 1826 by the French chemist Pierre Robiquet, simultaneously with purpurin, another red dye of lesser industrial interest, but the German chemical company BASF

patented the same process one day before he did. Over the next few years, Perkin found his research and development efforts increasingly eclipsed by the German chemical industry, and so in 1874 he sold his factory and retired from business, a very wealthy man.

Perkin died in 1907 of pneumonia

and appendicitis

. He had married twice: firstly in 1859 to Jemima Harriet, the daughter of John Lissett and secondly in 1866 to Alexandrine Caroline, daughter of Helman Mollwo. He had two sons from the first marriage (William Henry Perkin, Jr.

and Arthur George Perkin

) and one son (Frederick Mollwo Perkin) and four daughters from the second. All three sons became chemists. Perkin was a Liveryman of the Leathersellers' Company for 46 years and was elected Master of the Company for the year 1896-97; his father and grandfather had also been Liverymen of the same Company.

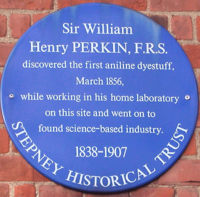

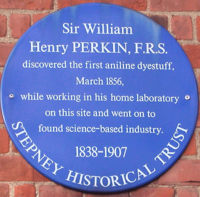

Today blue plaque

s mark the sites of Perkin's home in Cable Street

, by the junction with King David Lane, and the Perkin factory in Greenford.

and in 1889 their Davy Medal

. He was knight

ed in 1906, and in the same year was awarded the first Perkin Medal

, established to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of his discovery of mauveine

. Today the Perkin Medal is widely acknowledged as the highest honour in American industrial chemistry and has been awarded annually by the American section of the Society of Chemical Industry

to many inspiring and gifted chemists.

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

chemist

Chemist

A chemist is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties such as density and acidity. Chemists carefully describe the properties they study in terms of quantities, with detail on the level of molecules and their component atoms...

best known for his discovery, at the age of 18, of the first aniline

Aniline

Aniline, phenylamine or aminobenzene is an organic compound with the formula C6H5NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the prototypical aromatic amine. Being a precursor to many industrial chemicals, its main use is in the manufacture of precursors to polyurethane...

dye, mauveine

Mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was the first synthetic organic chemical dye.Its chemical name is3-amino-2,±9-dimethyl-5-phenyl-7-phenazinium acetate...

.

Early years

William Perkin was born in the East End of LondonEast End of London

The East End of London, also known simply as the East End, is the area of London, England, United Kingdom, east of the medieval walled City of London and north of the River Thames. Although not defined by universally accepted formal boundaries, the River Lea can be considered another boundary...

, the youngest of the seven children of George Perkin, a successful carpenter. His mother, Sarah, was of Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

descent but moved to east London as a child. He was baptised in the parish church of St Paul's, Shadwell

St. Paul's Church, Shadwell

St Paul's Church, Shadwell, is a historic church, located between The Highway and Shadwell Basin, on the edge of Wapping, in the East End of London, England...

, which had been connected to such luminaries as James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

, Jane Randolph Jefferson

Jane Randolph Jefferson

Jane Randolph Jefferson, née Jane Randolph was the wife of Peter Jefferson and the mother of president Thomas Jefferson. Born February 9, 1721 in Shadwell Parish, Tower Hamlets, London, she was the daughter of Isham Randolph and Jane Rogers, and a cousin of Peyton Randolph.There is almost no...

(mother of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

) and John Wesley

John Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

.

At the age of 14, Perkin attended the City of London School

City of London School

The City of London School is a boys' independent day school on the banks of the River Thames in the City of London, England. It is the brother school of the City of London School for Girls and the co-educational City of London Freemen's School...

, where he was taught by Thomas Hall, who fostered his scientific talent and encouraged him to pursue a career in chemistry.

Discovery of mauveine

In 1853, at the precocious age of 15, Perkin entered the Royal College of ChemistryRoyal College of Chemistry

The Royal College of Chemistry was a college originally based on Oxford Street in central London, England. It operated between 1845 and 1872....

in London (now part of Imperial College London

Imperial College London

Imperial College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom, specialising in science, engineering, business and medicine...

), where he began his studies under August Wilhelm von Hofmann

August Wilhelm von Hofmann

August Wilhelm von Hofmann was a German chemist.-Biography:Hofmann was born at Gießen, Grand Duchy of Hesse. Not intending originally to devote himself to physical science, he first took up the study of law and philology at Göttingen. But he then turned to chemistry, and studied under Justus von...

. At this time, chemistry was still in a quite primitive state: although the atomic theory was accepted, the major elements had been discovered, and techniques to analyse the proportions of the elements in many compounds were in place, it was still a difficult proposition to determine the arrangement of the elements in compounds. Hofmann had published a hypothesis on how it might be possible to synthesise quinine

Quinine

Quinine is a natural white crystalline alkaloid having antipyretic , antimalarial, analgesic , anti-inflammatory properties and a bitter taste. It is a stereoisomer of quinidine which, unlike quinine, is an anti-arrhythmic...

, an expensive natural substance much in demand for the treatment of malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

. Perkin, who had by then become one of Hofmann's assistants, embarked on a series of experiments to try to achieve this end. During the Easter

Easter

Easter is the central feast in the Christian liturgical year. According to the Canonical gospels, Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion. His resurrection is celebrated on Easter Day or Easter Sunday...

vacation in 1856, while Hofmann was visiting his native Germany, Perkin performed some further experiments in the crude laboratory in his apartment on the top floor of his home in Cable Street

Cable Street

Cable Street is a mile-long road in the East End of London, with several historic landmarks nearby, made famous by "the Battle of Cable Street" of 1936.-Location:Cable Street runs between the edge of The City and Limehouse:...

in east London. It was here that he made his great discovery: that aniline

Aniline

Aniline, phenylamine or aminobenzene is an organic compound with the formula C6H5NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the prototypical aromatic amine. Being a precursor to many industrial chemicals, its main use is in the manufacture of precursors to polyurethane...

could be partly transformed into a crude mixture which when extracted with alcohol produced a substance with an intense purple colour. Perkin, who had an interest in painting and photography, immediately became enthusiastic about this result and carried out further trials with his friend Arthur Church and his brother Thomas. Since these experiments were not part of the work on quinine which had been assigned to Perkin, the trio carried them out in a hut in Perkin's garden, so as to keep them secret from Hofmann.

They satisfied themselves that they might be able to scale up production of the purple substance and commercialise it as a dye, which they called mauveine

Mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was the first synthetic organic chemical dye.Its chemical name is3-amino-2,±9-dimethyl-5-phenyl-7-phenazinium acetate...

. Their initial experiments indicated that it dyed silk in a way which was stable when washed or exposed to light. They sent some samples to a dye works in Perth, Scotland

Perth, Scotland

Perth is a town and former city and royal burgh in central Scotland. Located on the banks of the River Tay, it is the administrative centre of Perth and Kinross council area and the historic county town of Perthshire...

, and received a very promising reply from the general manager of the company, Robert Pullar. Perkin filed for a patent

Patent

A patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

in August 1856, when he was still only 18. At the time, all dyes used for colouring cloth were natural substances, many of which were expensive and labour-intensive to extract. Furthermore, many lacked stability, or fastness. The colour purple, which had been a mark of aristocracy and prestige since ancient times, was especially expensive and difficult to produce — the dye used, known as Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple , also known as royal purple, imperial purple or imperial dye, is a purple-red natural dye, which is extracted from sea snails, and which was possibly first produced by the ancient Phoenicians...

, was made from the glandular mucus of certain molluscs. Its extraction was variable and complicated, and so Perkin and his brother realised that they had discovered a possible substitute whose production could be commercially successful.

Perkin could not have chosen a better time or place for his discovery: England was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

, largely driven by advances in the production of textiles; the science of chemistry had advanced to the point where it could have a major impact on industrial processes; and coal tar

Coal tar

Coal tar is a brown or black liquid of extremely high viscosity, which smells of naphthalene and aromatic hydrocarbons. Coal tar is among the by-products when coal iscarbonized to make coke or gasified to make coal gas...

, the major source of his raw material, was an abundant by-product of the process for making coal gas

Coal gas

Coal gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made by the destructive distillation of coal containing a variety of calorific gases including hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane and volatile hydrocarbons together with small quantities of non-calorific gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen...

and coke

Coke (fuel)

Coke is the solid carbonaceous material derived from destructive distillation of low-ash, low-sulfur bituminous coal. Cokes from coal are grey, hard, and porous. While coke can be formed naturally, the commonly used form is man-made.- History :...

.

Having invented the dye, Perkin was still faced with the problems of raising the capital for producing it, manufacturing it cheaply, adapting it for use in dyeing cotton, gaining acceptance for it among commercial dyers, and creating public demand for it. However, he was active in all of these areas: he persuaded his father to put up the capital, and his brothers to partner him in the creation of a factory; he invented a mordant for cotton; he gave technical advice to the dyeing industry; and he publicised his invention of the dye. Public demand was increased when a similar colour was adopted by Queen Victoria

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

in England and by Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, in France, and when the crinoline

Crinoline

Crinoline was originally a stiff fabric with a weft of horse-hair and a warp of cotton or linen thread. The fabric first appeared around 1830, but by 1850 the word had come to mean a stiffened petticoat or rigid skirt-shaped structure of steel designed to support the skirts of a woman’s dress into...

or hooped-skirt, whose manufacture used a large quantity of cloth, became fashionable. Everything seemed to fall into place by dint of hard work, with a little luck, too. Perkin became rich.

After the discovery of mauveine, many new aniline dyes appeared (some discovered by Perkin himself), and factories producing them were constructed across Europe.

Later years

Coumarin

Coumarin is a fragrant chemical compound in the benzopyrone chemical class, found in many plants, notably in high concentration in the tonka bean , vanilla grass , sweet woodruff , mullein , sweet grass , cassia cinnamon and sweet clover...

, one of the first synthetic perfume

Perfume

Perfume is a mixture of fragrant essential oils and/or aroma compounds, fixatives, and solvents used to give the human body, animals, objects, and living spaces "a pleasant scent"...

raw materials, and cinnamic acid

Cinnamic acid

Cinnamic acid is a white crystalline organic acid, which is slightly soluble in water.It is obtained from oil of cinnamon, or from balsams such as storax. It is also found in shea butter and is the best indication of its environmental history and post-extraction conditions...

. (The reaction used to make the latter became known as the Perkin reaction

Perkin reaction

The Perkin reaction is an organic reaction developed by William Henry Perkin that can be used to make cinnamic acids i.e. α-β-unsaturated aromatic acid by the aldol condensation of aromatic aldehydes and acid anhydrides in the presence of an alkali salt of the acid.Several reviews have been written....

.) Local lore has it that the colour of the nearby Grand Union Canal

Grand Union Canal

The Grand Union Canal in England is part of the British canal system. Its main line connects London and Birmingham, stretching for 137 miles with 166 locks...

changed from week to week depending on the activity at Perkin's Greenford

Greenford

Greenford is a large suburb in the London Borough of Ealing in west London, UK. It was historically an ancient parish in the former county of Middlesex. The most prominent landmarks in the suburb are the A40, a major dual-carriageway; Horsenden Hill, above sea level; the small Parish Church of...

dyeworks. In 1869, Perkin found a method for the commercial production from anthracene

Anthracene

Anthracene is a solid polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon consisting of three fused benzene rings. It is a component of coal-tar. Anthracene is used in the production of the red dye alizarin and other dyes...

of the brilliant red dye alizarin

Alizarin

Alizarin or 1,2-dihydroxyanthraquinone is an organic compound with formula that has been used throughout history as a prominent dye, originally derived from the roots of plants of the madder genus.Alizarin was used as a red dye for the English parliamentary "new model" army...

, which had been isolated and identified from madder

Madder

Rubia is a genus of the madder family Rubiaceae, which contains about 60 species of perennial scrambling or climbing herbs and sub-shrubs native to the Old World, Africa, temperate Asia and America...

root some forty years earlier in 1826 by the French chemist Pierre Robiquet, simultaneously with purpurin, another red dye of lesser industrial interest, but the German chemical company BASF

BASF

BASF SE is the largest chemical company in the world and is headquartered in Germany. BASF originally stood for Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik . Today, the four letters are a registered trademark and the company is listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, London Stock Exchange, and Zurich Stock...

patented the same process one day before he did. Over the next few years, Perkin found his research and development efforts increasingly eclipsed by the German chemical industry, and so in 1874 he sold his factory and retired from business, a very wealthy man.

Perkin died in 1907 of pneumonia

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung—especially affecting the microscopic air sacs —associated with fever, chest symptoms, and a lack of air space on a chest X-ray. Pneumonia is typically caused by an infection but there are a number of other causes...

and appendicitis

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the appendix. It is classified as a medical emergency and many cases require removal of the inflamed appendix, either by laparotomy or laparoscopy. Untreated, mortality is high, mainly because of the risk of rupture leading to...

. He had married twice: firstly in 1859 to Jemima Harriet, the daughter of John Lissett and secondly in 1866 to Alexandrine Caroline, daughter of Helman Mollwo. He had two sons from the first marriage (William Henry Perkin, Jr.

William Henry Perkin, Jr.

William Henry Perkin, Jr. was an English organic chemist who was primarily known for his groundbreaking research work on the degradation of naturally occurring organic compounds.-Early life:...

and Arthur George Perkin

Arthur George Perkin

Arthur George Perkin FRS was an English chemist.He was the son of Sir William Henry Perkin who had founded the aniline dye industry, and was born at Sudbury, England, close to his father's dyeworks at Greenford. His brother was William Henry Perkin, Jr....

) and one son (Frederick Mollwo Perkin) and four daughters from the second. All three sons became chemists. Perkin was a Liveryman of the Leathersellers' Company for 46 years and was elected Master of the Company for the year 1896-97; his father and grandfather had also been Liverymen of the same Company.

Today blue plaque

Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event, serving as a historical marker....

s mark the sites of Perkin's home in Cable Street

Cable Street

Cable Street is a mile-long road in the East End of London, with several historic landmarks nearby, made famous by "the Battle of Cable Street" of 1936.-Location:Cable Street runs between the edge of The City and Limehouse:...

, by the junction with King David Lane, and the Perkin factory in Greenford.

Honours and Awards

Perkin received many honours in his lifetime. In June, 1866 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and in 1879 received their Royal MedalRoyal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal, is a silver-gilt medal awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important contributions to the advancement of natural knowledge" and one for "distinguished contributions in the applied sciences" made within the Commonwealth of...

and in 1889 their Davy Medal

Davy Medal

The Davy Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of London "for an outstandingly important recent discovery in any branch of chemistry". Named after Humphry Davy, the medal is awarded with a gift of £1000. The medal was first awarded in 1877 to Robert Wilhelm Bunsen and Gustav Robert Kirchhoff "for...

. He was knight

Knight

A knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

ed in 1906, and in the same year was awarded the first Perkin Medal

Perkin Medal

The Perkin Medal is an award given annually by the American section of the Society of Chemical Industry to a scientist residing in America for an "innovation in applied chemistry resulting in outstanding commercial development." It is considered the highest honor given in the US industrial chemical...

, established to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of his discovery of mauveine

Mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was the first synthetic organic chemical dye.Its chemical name is3-amino-2,±9-dimethyl-5-phenyl-7-phenazinium acetate...

. Today the Perkin Medal is widely acknowledged as the highest honour in American industrial chemistry and has been awarded annually by the American section of the Society of Chemical Industry

Society of Chemical Industry

The Society of Chemical Industry is a learned society set up in 1881 "to further the application of chemistry and related sciences for the public benefit". Its purpose is "Promoting the commercial application of science for the benefit of society". Its first president was Henry Enfield Roscoe and...

to many inspiring and gifted chemists.

Further reading

- Garfield, Simon Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color that Changed the World, ISBN 0-393-02005-3 (2000).

- Travis, Anthony S. "Perkin, Sir William Henry (1838–1907)" in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited C. Mathew et al. Oxford University PressOxford University PressOxford University Press is the largest university press in the world. It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the Vice-Chancellor known as the Delegates of the Press. They are headed by the Secretary to the Delegates, who serves as...

: 2004. ISBN 0-19-861411-X. - Farrell, Jerome "The Master Leatherseller who Changed the World" in The Leathersellers' Review 2005-06, pp12–14