Anarchism in Germany

Encyclopedia

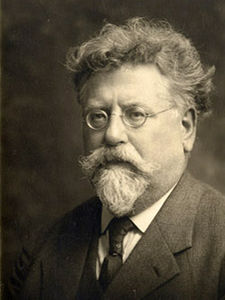

German individualist philosopher Max Stirner

became an important early influence in anarchism. Afterwards Johann Most

became an important anarchist propagandist in both Germany and in the United States. In the late 19th century and early 20th century there appeared individualist anarchists influenced by Stirner such as John Henry Mackay

, Adolf Brand

and Anselm Ruest (Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (Salomo Friedlaender).

The anarchists Gustav Landauer

, Silvio Gesell

and Erich Mühsam

had important leadership positions within the revolutionary councilist

structures. During the rise of the Nazi regime Erich Mühsam

was assassinated in a concentration camp both for his anarchist positions and for his Jewish background. The anarchosyndicalist activist and writer Rudolf Rocker

became an influential personality in the establishment of the international federation of anarchosyndicalist organizations called International Workers Association

as well as the German Free Association of German Trade Unions

.

Contemporary german anarchist organizations include the anarchosyndicalist Free Workers' Union

and the anarchist federation Federation of German speaking Anarchists (Föderation Deutschsprachiger AnarchistInnen).

(7 October 1820 – 18 August 1886) was a German political philosopher and a member of the Young Hegelians

. According to Lawrence S. Stepelevich, Edgar Bauer was the most anarchistic of the Young Hegelians, and "...it is possible to discern, in the early writings of Edgar Bauer, the theoretical justification of political terrorism." German anarchists such as Max Nettlau

and Gustav Landauer

credited Edgar Bauer with founding the anarchist tradition in Germany. In 1843 he published a book titled The Conflict of Criticism with Church and State. This caused him to be charged with sedition. He was imprisoned for four years in the fortress at Magdeburg. While he was in prison, his former associates Marx and Engels published a scathing critique of him and his brother Bruno, titled The Holy Family (1844). They resumed the attack in The German Ideology (1846), which was not published at the time.

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (October 25, 1806 – June 26, 1856), better known as Max Stirner (the nom de plume he adopted from a schoolyard nickname he had acquired as a child because of his high brow, in German

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (October 25, 1806 – June 26, 1856), better known as Max Stirner (the nom de plume he adopted from a schoolyard nickname he had acquired as a child because of his high brow, in German

'Stirn'), was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism

, existentialism

, post-modernism and anarchism

, especially of individualist anarchism. Stirner's main work is The Ego and Its Own

, also known as The Ego and His Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum in German, which translates literally as The Only One and his Property). This work was first published in 1844 in Leipzig

, and has since appeared in numerous editions and translations.

Stirner's philosophy is usually called "egoism

". He says that the egoist rejects pursuit of devotion to "a great idea, a good cause, a doctrine, a system, a lofty calling," saying that the egoist has no political calling but rather "lives themselves out" without regard to "how well or ill humanity may fare thereby." Stirner held that the only limitation on the rights of the individual is his power to obtain what he desires. He proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions—including the notion of State, property as a right, natural rights in general, and the very notion of society—were mere spooks in the mind. Stirner wanted to "abolish not only the state but also society as an institution responsible for its members."

Max Stirner

's idea of the union of Egoists , was first expounded in The Ego and Its Own

. The Union is understood as a non-systematic association, which Stirner proposed in contradistinction to the state

. The Union is understood as a relation between egoists which is continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will. The Union requires that all parties participate out of a conscious egoism

. If one party silently finds themselves to be suffering, but puts up and keeps the appearance, the union has degenerated into something else. This union is not seen as an authority

above a person's own will. This idea has received interpretations for politics, economic and sex/love.

Stirner claimed that property comes about through might: "Whoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property." "What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." "I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!". His concept of "egoistic property" not only rejects moral restraint on how own obtains and uses things, but includes other people as well..

Though Stirner's philosophy is individualist, it has influenced some libertarian communists

and anarcho-communists. "For Ourselves Council for Generalized Self-Management" discusses Stirner and speaks of a "communist egoism," which is said to be a "synthesis of individualism and collectivism," and says that "greed in its fullest sense is the only possible basis of communist society." Forms of libertarian communism

such as insurrectionary anarchism

are influenced by Stirner. Anarcho-communist Emma Goldman

was influenced by both Stirner and Peter Kropotkin

and blended their philosophies together in her own.

Johann Joseph Most (February 5, 1846 in Augsburg

Johann Joseph Most (February 5, 1846 in Augsburg

, Bavaria

- March 17, 1906 in Cincinnati

, Ohio

) was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed

".

As the 1860s drew to a close, Most was won over to the ideas of international socialism, an emerging political movement in Germany

and Austria

. Most saw in the doctrines of Karl Marx

and Ferdinand Lassalle

a blueprint for a new egalitarian

society and became a fervid supporter of the Social Democracy, as the Marxist

movement was known in the day. Most was repeatedly arrested for his attacks on patriotism

and conventional religion and ethics

, and for his gospel of terrorism

, preached in prose and in many songs such as those in his Proletarier-Liederbuch (Proletarian Songbook). Some of his experiences in prison were recounted in the 1876 work, Die Bastille am Plötzensee: Blätter aus meinem Gefängniss-Tagebuch (The Bastille on Plötzensee: Pages from my Prison Diary).

After advocating violent action, including the use of explosive bombs, as a mechanism to bring about revolutionary change, Most was forced into exile by the government. He went to France but was forced to leave at the end of 1878, settling in London

. There he founded his own newspaper, Freiheit (Freedom), with the first issue coming off the press dated January 4, 1879. Convinced by his own experience of the futility of parliamentary action, Most began to espouse the doctrine of anarchism

, which led to his expulsion from the German Social Democratic Party in 1880. Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, Most emigrated to the USA upon his release from prison in 1882. He promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés. Most resumed the publication of the Freiheit in New York. He was imprisoned in 1886, again in 1887, and in 1902, the last time for two months for publishing after the assassination of President McKinley

an editorial in which he argued that it was no crime to kill a ruler. A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman

and Alexander Berkman

. Most was in Cincinnati, Ohio

to give a speech when he fell ill. Diagnosed with erysipelas

, doctors could do little for him, and he died a few days later.

An influential form of individualist anarchism

An influential form of individualist anarchism

, called "egoism," or egoist anarchism

, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, the German Max Stirner

. Stirner's The Ego and Its Own

, published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy. According to Stirner, the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire, without regard for God, state, or morality. To Stirner, rights were spooks

in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the individuals are its reality". Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists

, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will, which Stirner proposed as a form of organization in place of the state

. Egoist anarchists claim that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals. "Egoism" has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy. It was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT

activist John Henry Mackay

.

the Scottish-born German John Henry Mackay became the most important individualist anarchist propagandist. He fused Stirnerist egoism with the positions of Benjamin Tucker and translated Tucker into German. Two semi-fictional writings of his own Die Anarchisten

and Der Freiheitsucher contributed to individualist theory, updating egoist themes with respect to the anarchist movement. His writing were translated into English as well. Mackay is also an important European early activist for LGBT

rights.

writer

, Stirnerist anarchist

and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality

and homosexuality

. Brand published the world's first ongoing homosexual publication, Der Eigene

in 1896. The name was taken from Stirner, who had greatly influenced the young Brand, and refers to Stirner's concept of "self-ownership

" of the individual. Der Eigene

concentrated on cultural and scholarly material, and may have averaged around 1500 subscribers per issue during its lifetime. Contributors included Erich Mühsam

, Kurt Hiller

, John Henry Mackay

(under the pseudonym Sagitta) and artists Wilhelm von Gloeden

, Fidus

and Sascha Schneider

. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself. Benjamin Tucker

followed this journal from the United States.

) by Max Stirner

. Another influence was the thought of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

. The publication was connected to the local expressionist

artistic current and the transition from it towards dada

.

the anarchists Gustav Landauer

, Silvio Gesell

and Erich Mühsam

had important leadership positions within the revolutionary councilist

structures. On 6 April 1919, a Soviet Republic was formally proclaimed. Initially, it was ruled by USPD members such as Ernst Toller

, and anarchists like Gustav Landauer

, Silvio Gesell

and Erich Mühsam

.

, Baden

— 2 May 1919 in Munich

, Bavaria

) was one of the leading theorists on anarchism

in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism

and an avowed pacifist

. At the "International Convention of Socialist Workers" of the II. Socialist International

in August 1893 in Zurich, Landauer, as a delegate for the Berlin anarchists, stood for an "anarchist socialism". Against an anarchist minority the convention with 411 delegates from 20 countries passed a resolution in favour of participation in elections and political action in parliaments. The anarchists were excluded from the II. Socialist International. From 1909 to 1915 Landauer published the magazine "The Socialist" (Der Sozialist) in Berlin, which was considered to be the mouthpiece of the "Socialist Federation" (Sozialistischer Bund) founded by Landauer in 1908. Among the first members were Erich Mühsam

and Martin Buber

. When the soviet republic was proclaimed on 7 April 1919 against the elected government of Johannes Hoffmann

, Landauer became Commissioner of Enlightenment and Public Instruction. After the City of Munich was reconquered by the German army and Freikorps

units, Gustav Landauer was arrested on 1 May 1919 and stoned to death by troopers one day later in Munich's Stadelheim Prison

. After the Nazis were elected in Germany in 1933 they destroyed Landauer's grave, which had been erected in 1925, sent his remains to the Jewish congregation of Munich, charging them for the costs. Landauer was later put to rest at the Munich Waldfriedhof

(Forest Cemetery)

Landauer supported anarchism already in the 90s of the 19th century. In those years he was especially enthusiastic about the individualistic approach of Max Stirner

. He didn't want to stay behind Stirner's extremely individual approach but wanted to develop a new general public, a unity and community. His "social Anarchism" was a union of individuals on a voluntary basis in small socialist communities which came together freely. Landauer's goal was always emancipation from state, church or other forms of subordination in society. The expression 'Anarchism' stems from the Greek "arche" meaning 'power', 'reign' or 'rule'. Thus 'An-archy' equals 'non-power', 'no-reign' or 'no-rule'. The rejection of the state is common to all Anarchist positions. Some also reject institutions and moral concepts, such as church, matrimony or family; the rejection is, of course, voluntary. Landauer came out against Marxists and Social Democrats, reproaching them for wanting to erect another state executing power. For him Anarchism was a spiritual movement, almost religious. In contrast to other Anarchists he did not reject matrimony; on the contrary, it was a pillar of the community in Landauer's system. True Anarchism results from the "inner segregation" of the individuals. It is exactly this from which one is to be freed. Precondition for autonomy and independence respectively is the "seclusion" which leads to a "Unity with the world". According to Landauer it is necessary to change the nature of man or at least to change his ways, so that finally the inner convictions can appear and be lived. This includes an "Anarchism of deed" that is never strictly theoretical.

.jpg) Silvio Gesell (March 17, 1862 – March 11, 1930) was a German

Silvio Gesell (March 17, 1862 – March 11, 1930) was a German

merchant

, theoretical economist

, social activist, anarchist and founder of Freiwirtschaft

. After the bloody end of the Soviet Republic, Gesell was held in detention for several months until being acquitted of treason

by a Munich

court

because of the speech he gave in his own defense. Because of his participation in the Soviet Republic, Switzerland denied him the opportunity to return to his farm in Neuchâtel. Gesell then moved first to Nuthetal

, Potsdam-Mittelmark

, then back to Oranienburg. After another short stay in Argentina in 1924, he returned to Oranienburg in 1927. Here, he died of pneumonia

on March 11, 1930.

essay

ist, poet

and playwright

. He emerged at the end of World War I

as one of the leading agitators for a federated

Bavarian Soviet Republic

. Also a cabaret

performer, he achieved international prominence during the years of the Weimar Republic

for works which, before Hitler

came to power in 1933, condemned Nazism

and satirized

the future dictator

. Mühsam died in the Oranienburg concentration camp

in 1934.

Mühsam moved to Berlin in 1900, where he soon became involved in a group called Neue Gemeinschaft (New Society) under the direction of Julius and Heinrich Hart which combined socialist philosophy with theology and communal living in the hopes of becoming "a forerunner of a socially united great working commune of humanity." Within this group, Mühsam became acquainted with Gustav Landauer

who encouraged his artistic growth and compelled the young Mühsam to develop his own activism based on a combination of communist

and anarchist

political philosophy that Landauer introduced to him. Desiring more political involvement, in 1904, Mühsam withdrew from Neue Gemeinschaft and relocated temporarily to an artists commune in Ascona

, Switzerland

where vegetarianism

was mixed with communism

and socialism

.In 1911, Mühsam founded the newspaper, Kain (Cain), as a forum for communist-anarchist ideologies, stating that it would "be a personal organ for whatever the editor, as a poet, as a citizen of the world, and as a fellow man had on his mind." Mühsam used Kain to ridicule the German state and what he perceived as excesses and abuses of authority, standing out in favour of abolishing capital punishment

, and opposing the government's attempt at censoring theatre, and offering prophetic and perceptive analysis of international affairs. For the duration of World War I

, publication was suspended to avoid government-imposed censorship often enforced against private newspapers that disagreed with the imperial government and the war.

In 1926, Mühsam founded a new journal which he called Fanal (The Torch), in which he openly and precariously criticized the communists and the far Right-wing conservative

In 1926, Mühsam founded a new journal which he called Fanal (The Torch), in which he openly and precariously criticized the communists and the far Right-wing conservative

elements within the Weimar Republic. During these years, his writings and speeches took on a violent, revolutionary tone, and his active attempts to organize a united front to oppose the radical Right provoked intense hatred from conservatives and nationalists

within the Republic. Mühsam specifically targeted his writings to satirize the growing phenomenon of Nazism

, which later raised the ire of Adolf Hitler

and Joseph Goebbels

. Die Affenschande (1923), a short story, ridiculed the racial doctrines of the Nazi party, while the poem Republikanische Nationalhymne (1924) attacked the German judiciary for its disproportionate punishment of leftists while barely punishing the right wing participants in the Putsch.

Mühsam was arrested on charges unknown in the early morning hours of 28 February 1933, within a few hours after the Reichstag fire

in Berlin. Joseph Goebbels

, the Nazi propaganda minister, labelled him as one of "those Jewish subversives." It is alleged that Mühsam was planning to flee to Switzerland

within the next day. Over the next seventeen months, he would be imprisoned in the concentration camps at Sonnenburg, Brandenburg

and finally, Oranienburg

. On 2 February 1934, Mühsam was transferred to the concentration camp

at Oranienburg

. The beatings and torture continued, until finally on the night of 9 July 1934, Mühsam was tortured and murdered by the guards, his battered corpse found hanging in a latrine the next morning. An official Nazi report dated 11 July stated that Erich Mühsam committed suicide, hanging himself while in "protective custody" at Oranienburg. However, a report from Prague

on 20 July 1934 in the New York Times stated otherwise

to join him in Berlin

to re-build the Free Association of German Trade Unions

(FVdG). The FVdG was a radical labor federation that quit the SPD in 1908 and became increasingly syndicalist and anarchist. During World War I, it had been unable to continue its activities for fear of government repression, but remained in existence as an underground organization.Rocker was opposed to the FVdG's alliance with the communists during and immediately after the November Revolution, as he rejected Marxism, especially the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat

. Soon after arriving in Germany, however, he once again became seriously ill. He started giving public speeches in March 1919, including one at a congress of munitions workers in Erfurt

, where he urged them to stop producing war material. During this period the FVdG grew rapidly and the coalition with the communists soon began to crumble. Eventually all syndicalist members of the Communist Party

were expelled. From December 27 to December 30, 1919, the twelfth national congress of the FVdG was held in Berlin. The organization decided to become the Free Workers' Union of Germany

(FAUD) under a new platform, which had been written by Rocker: the Prinzipienerklärung des Syndikalismus (Declaration of Syndicalist Principles). It rejected political parties and the dictatorship of the proletariat as bourgeois concepts. The program only recognized de-centralized, purely economic organizations. Although public ownership of land, means of production, and raw materials was advocated, nationalization and the idea of a communist state were rejected. Rocker decried nationalism

as the religion of the modern state and opposed violence, championing instead direct action

and the education of the workers.

On Gustav Landauer

's death during the Munich Soviet Republic uprising, Rocker took over the work of editing the German publications of Kropotkin's writings. In 1920, the social democratic Defense Minister Gustav Noske

started the suppression of the revolutionary left, which led to the imprisonment of Rocker and Fritz Kater. During their mutual detainment, Rocker convinced Kater, who had still held some social democratic ideals, completely of anarchism.

In the following years, Rocker became one of the most regular writers in the FAUD organ Der Syndikalist. In 1920, the FAUD hosted an international syndicalist conference, which ultimately led to the founding of the International Workers Association

(IWA) in December 1922. Augustin Souchy

, Alexander Schapiro

, and Rocker became the organization's secretaries and Rocker wrote its platform. In 1921, he wrote the pamphlet Der Bankrott des russischen Staatskommunismus (The Bankruptcy of Russian State Communism) attacking the Soviet Union. He denounced what he considered a massive oppression of individual freedoms and the suppression of anarchists starting with the a purg on April 12, 1918. He supported instead the workers who took part in the Kronstadt uprising and the peasant movement led by the anarchist Nestor Makhno

, whom he would meet in Berlin in 1923. In 1924, Rocker published a biography of Johann Most

called Das Leben eines Rebellen (The Life of a Rebel). There are great similarities between the men's vitas. It was Rocker who convinced the anarchist historian Max Nettlau

to start publication of his anthology Geschichte der Anarchie (History of Anarchy) in 1925.

During the mid 1920s, the decline of Germany's syndicalist movement started. The FAUD had reached its peak of around 150,000 members in 1921, but then started losing members to both the Communist and the Social Democratic Party

. Rocker attributed this loss of membership to the mentality of German workers accustomed to military discipline, accusing the communists of using similar tactics to the Nazis and thus attracting such workers. At first only planning a short book on nationalism, he started work on Nationalism and Culture

, which would be published in 1937 and become one of Rocker's best-known works, around 1925. 1925 also saw Rocker visit North America on a lecture tour with a total of 162 appearances. He was encouraged by the anarcho-syndicalist movement he found in the US and Canada.

Returning to Germany in May 1926, he became increasingly worried about the rise of nationalism and fascism. He wrote to Nettlau in 1927: "Every nationalism begins with a Mazzini, but in its shadow there lurks a Mussolini

Returning to Germany in May 1926, he became increasingly worried about the rise of nationalism and fascism. He wrote to Nettlau in 1927: "Every nationalism begins with a Mazzini, but in its shadow there lurks a Mussolini

". In 1929, Rocker was a co-founder of the Gilde freiheitlicher Bücherfreunde (Guild of Libertarian Bibliophiles), a publishing house which would release works by Alexander Berkman

, William Godwin

, Erich Mühsam

, and John Henry Mackay

. In the same year he went on a lecture tour in Scandinavia and was impressed by the anarcho-syndicalists there. Upon return, he wondered whether Germans were even capable of anarchist thought. In the 1930 elections

, the Nazi Party received 18.3% of all votes, a total of 6 million. Rocker was worried: "Once the Nazis get to power, we'll all go the way of Landauer

and Eisner

" (who were killed by reactionaries in the course of the Munich Soviet Republic uprising).

After the Reichstag fire

on February 27, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of Erich Mühsam

's arrest. After his death in July 1934, Rocker would write a pamphlet called Der Leidensweg Erich Mühsams (The Life and Suffering of Erich Mühsam) about the anarchist's fate. Rocker reached Basel, Switzerland on March 8 by the last train to cross the border without being searched. Two weeks later, Rocker and his wife joined Emma Goldman in St. Tropez, France. There he wrote Der Weg ins Dritte Reich (The Path to the Third Reich) about the events in Germany, but it would only be published in Spanish.

In May, Rocker and Witkop moved back to London. There Rocker was welcomed by many of the Jewish anarchists he had lived and fought alongside for many years. He held lectures all over the city. In July, he attended an extraordinary IWA meeting in Paris, which decided to smuggle its organ Die Internationale into Nazi Germany. In 1937, Nationalism and Culture

, which he had started work on around 1925, was finally published with the help of anarchists from Chicago Rocker had met in 1933. A Spanish edition was released in three volumes in Barcelona

, the stronghold of the Spanish anarchists. It would be his best-known work.In 1938, Rocker published a history of anarchist thought, which he traced all the way back to ancient times, under the name Anarcho-Syndicalism. A modified version of the essay would be published in the Philosophical Library series European Ideologies under the name Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in 1949.

After World War II, an appeal in the Fraye Arbeter Shtime detailing the plight of German anarchists and called for Americans to support them. By February 1946, the sending of aid parcels to anarchists in Germany was a large-scale operation. In 1947, Rocker published Zur Betrachting der Lage in Deutschland (Regarding the Portrayal of the Situation in Germany) about the impossibility of another anarchist movement in Germany. It became the first post-World War II anarchist writing to be distributed in Germany. Rocker thought young Germans were all either totally cynical or inclined to fascism and awaited a new generation to grow up before anarchism could bloom once again in the country. Nevertheless, the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (FFS) was founded in 1947 by former FAUD members. Rocker wrote for its organ, Die Freie Gesellschaft, which survived until 1953. In 1949, Rocker published another well-known work. On September 10, 1958, Rocker died in the Mohegan Colony.

(German

for "grassroots revolution") is an anarcho-pacifist

magazine founded in 1972 by Wolfgang Hertle in West Germany

. It focuses on social equality

, anti-militarism and ecology

. The magazine is considered the most influential and long-lived anarchist publication of the German post-war period

. The zero issue of graswurzelrevolution (GWR) [Grass Roots Revolution] was published in the summer of 1972 in Augsburg

, Bavaria

. The "monthly magazine for a non-violent, anarchist society" was inspired by "Peace News" (published since 1936 by War Resisters International (WRI) in London

), the German-speaking "Direkte Aktion" ("newspaper for anarchism and non-violence"; published from 1965 to 1966 by Wolfgang Zucht and other non-violent activists in Hanover) and the French-speaking "Anarchisme et Nonviolence" (published in Switzerland

and France

from 1964 to 1973).

The Free Workers' Union

(German

: Freie Arbeiterinnen- und Arbeiter-Union or Freie ArbeiterInnen-Union; abbreviated FAU) is a small anarcho-syndicalist union in Germany

. It is the German section of the International Workers Association

(IWA), to which the larger and better known Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

in Spain

also belongs. Because of their membership in the IWA the name is also often abbreviated as FAU-IAA or FAU/IAA. he FAU sees itself in the tradition of the Free Workers' Union of Germany

(German: Freie Arbeiter Union Deutschlands; FAUD), the largest anarcho-syndicalist union in Germany until it disbanded in 1933 in order to avoid repression by the nascent National Socialist

regime, and to illegally organize resistance against it. The FAU was then founded in 1977 and has grown consistently all through the 1990s. Now, the FAU consists of just under 40 groups, organized locally and by branch of trade. Because it rejects hierarchical organizations and political representation and believes in the concept of federalism

, most of the decisions are made by the local unions. The federalist organization exists in order to coordinate strikes, campaigns and actions and for communication purposes. There are 800-1000 members organized in the various local unions. The FAU publishes the bimonthly anarcho-syndicalist newspaper Direkte Aktion

as well as pamphlets on current and historical topics. Because it supports the classical concept of the abolition of the wage system, the FAU is observed by the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution).

The Federation of German speaking Anarchists (Föderation Deutschsprachiger AnarchistInnen) is a synthesist anarchist federation of german speaking countries which is affiliated with the International of Anarchist Federations

.

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt , better known as Max Stirner , was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism...

became an important early influence in anarchism. Afterwards Johann Most

Johann Most

Johann Joseph Most was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed". His grandson was Boston Celtics radio play-by-play man Johnny Most...

became an important anarchist propagandist in both Germany and in the United States. In the late 19th century and early 20th century there appeared individualist anarchists influenced by Stirner such as John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay was an individualist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of Die Anarchisten and Der Freiheitsucher . Mackay was published in the United States in his friend Benjamin Tucker's magazine, Liberty...

, Adolf Brand

Adolf Brand

Adolf Brand was a German writer, individualist anarchist and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality.-Biography:...

and Anselm Ruest (Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (Salomo Friedlaender).

The anarchists Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer was one of the leading theorists on anarchism in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism and an avowed pacifist. Landauer is also known for his study and translations of William Shakespeare's works into German...

, Silvio Gesell

Silvio Gesell

Silvio Gesell was a German merchant, theoretical economist, social activist, anarchist and founder of Freiwirtschaft.-Life:...

and Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic....

had important leadership positions within the revolutionary councilist

Council communism

Council communism is a current of libertarian Marxism that emerged out of the November Revolution in the 1920s, characterized by its opposition to state capitalism/state socialism as well as its advocacy of workers' councils as the basis for workers' democracy.Originally affiliated with the...

structures. During the rise of the Nazi regime Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic....

was assassinated in a concentration camp both for his anarchist positions and for his Jewish background. The anarchosyndicalist activist and writer Rudolf Rocker

Rudolf Rocker

Johann Rudolf Rocker was an anarcho-syndicalist writer and activist. A self-professed anarchist without adjectives, Rocker believed that anarchist schools of thought represented "only different methods of economy" and that the first objective for anarchists was "to secure the personal and social...

became an influential personality in the establishment of the international federation of anarchosyndicalist organizations called International Workers Association

International Workers Association

The International Workers' Association is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labour unions and initiatives based primarily in Europe and Latin America....

as well as the German Free Association of German Trade Unions

Free Association of German Trade Unions

The Free Association of German Trade Unions was a trade union federation in Imperial and early Weimar Germany. It was founded in 1897 in Halle under the name Representatives' Centralization of Germany as the national umbrella organization of the localist current of the German labor movement...

.

Contemporary german anarchist organizations include the anarchosyndicalist Free Workers' Union

Free Workers' Union

The Free Workers' Union is a small anarcho-syndicalist union in Germany. It is the German section of the International Workers Association , to which the larger and better known Confederación Nacional del Trabajo in Spain also belongs...

and the anarchist federation Federation of German speaking Anarchists (Föderation Deutschsprachiger AnarchistInnen).

Stirner and other pioneers

Edgar BauerEdgar Bauer

Edgar Bauer was a German political philosopher and a member of the Young Hegelians. He was the younger brother of Bruno Bauer. According to Lawrence S...

(7 October 1820 – 18 August 1886) was a German political philosopher and a member of the Young Hegelians

Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians, or Left Hegelians, were a group of Prussian intellectuals who in the decade or so after the death of Hegel in 1831, wrote and responded to his ambiguous legacy...

. According to Lawrence S. Stepelevich, Edgar Bauer was the most anarchistic of the Young Hegelians, and "...it is possible to discern, in the early writings of Edgar Bauer, the theoretical justification of political terrorism." German anarchists such as Max Nettlau

Max Nettlau

Max Heinrich Hermann Reinhardt Nettlau was a German anarchist and historian. Although born in Neuwaldegg and raised in Vienna he retained his Prussian nationality throughout his life. A student of the Welsh language he spent time in London where he joined the Socialist League where he met...

and Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer was one of the leading theorists on anarchism in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism and an avowed pacifist. Landauer is also known for his study and translations of William Shakespeare's works into German...

credited Edgar Bauer with founding the anarchist tradition in Germany. In 1843 he published a book titled The Conflict of Criticism with Church and State. This caused him to be charged with sedition. He was imprisoned for four years in the fortress at Magdeburg. While he was in prison, his former associates Marx and Engels published a scathing critique of him and his brother Bruno, titled The Holy Family (1844). They resumed the attack in The German Ideology (1846), which was not published at the time.

Max Stirner

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

'Stirn'), was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism

Nihilism

Nihilism is the philosophical doctrine suggesting the negation of one or more putatively meaningful aspects of life. Most commonly, nihilism is presented in the form of existential nihilism which argues that life is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value...

, existentialism

Existentialism

Existentialism is a term applied to a school of 19th- and 20th-century philosophers who, despite profound doctrinal differences, shared the belief that philosophical thinking begins with the human subject—not merely the thinking subject, but the acting, feeling, living human individual...

, post-modernism and anarchism

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

, especially of individualist anarchism. Stirner's main work is The Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own is a philosophical work by German philosopher Max Stirner . This work was first published in 1845, although with a stated publication date of "1844" to confuse the Prussian censors.-Content:...

, also known as The Ego and His Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum in German, which translates literally as The Only One and his Property). This work was first published in 1844 in Leipzig

Leipzig

Leipzig Leipzig has always been a trade city, situated during the time of the Holy Roman Empire at the intersection of the Via Regia and Via Imperii, two important trade routes. At one time, Leipzig was one of the major European centres of learning and culture in fields such as music and publishing...

, and has since appeared in numerous editions and translations.

Stirner's philosophy is usually called "egoism

Egoism

* Egotism, an excessive or exaggerated sense of self-importance* Ethical egoism, the doctrine that holds that individuals ought to do what is in their self-interest...

". He says that the egoist rejects pursuit of devotion to "a great idea, a good cause, a doctrine, a system, a lofty calling," saying that the egoist has no political calling but rather "lives themselves out" without regard to "how well or ill humanity may fare thereby." Stirner held that the only limitation on the rights of the individual is his power to obtain what he desires. He proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions—including the notion of State, property as a right, natural rights in general, and the very notion of society—were mere spooks in the mind. Stirner wanted to "abolish not only the state but also society as an institution responsible for its members."

Max Stirner

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt , better known as Max Stirner , was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism...

's idea of the union of Egoists , was first expounded in The Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own is a philosophical work by German philosopher Max Stirner . This work was first published in 1845, although with a stated publication date of "1844" to confuse the Prussian censors.-Content:...

. The Union is understood as a non-systematic association, which Stirner proposed in contradistinction to the state

State (polity)

A state is an organized political community, living under a government. States may be sovereign and may enjoy a monopoly on the legal initiation of force and are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union...

. The Union is understood as a relation between egoists which is continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will. The Union requires that all parties participate out of a conscious egoism

Selfishness

Selfishness denotes an excessive or exclusive concern with oneself, and as such it exceeds mere self interest or self concern. Insofar as a decision maker knowingly burdens or harms others for personal gain, the decision is selfish. In contrast, self-interest is more general...

. If one party silently finds themselves to be suffering, but puts up and keeps the appearance, the union has degenerated into something else. This union is not seen as an authority

Authority

The word Authority is derived mainly from the Latin word auctoritas, meaning invention, advice, opinion, influence, or command. In English, the word 'authority' can be used to mean power given by the state or by academic knowledge of an area .-Authority in Philosophy:In...

above a person's own will. This idea has received interpretations for politics, economic and sex/love.

Stirner claimed that property comes about through might: "Whoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property." "What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." "I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!". His concept of "egoistic property" not only rejects moral restraint on how own obtains and uses things, but includes other people as well..

Though Stirner's philosophy is individualist, it has influenced some libertarian communists

Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic, stateless society without private property in the means of production...

and anarcho-communists. "For Ourselves Council for Generalized Self-Management" discusses Stirner and speaks of a "communist egoism," which is said to be a "synthesis of individualism and collectivism," and says that "greed in its fullest sense is the only possible basis of communist society." Forms of libertarian communism

Libertarian communism

Libertarian communism is a theory of libertarianism which advocates the abolition of the state and private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership of the means of production, a direct democracy and self-governance....

such as insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory, practice and tendency within the anarchist movement which emphasizes the theme of insurrection within anarchist practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based on a political programme and...

are influenced by Stirner. Anarcho-communist Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century....

was influenced by both Stirner and Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin

Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian zoologist, evolutionary theorist, philosopher, economist, geographer, author and one of the world's foremost anarcho-communists. Kropotkin advocated a communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations between...

and blended their philosophies together in her own.

Johann Most

Augsburg

Augsburg is a city in the south-west of Bavaria, Germany. It is a university town and home of the Regierungsbezirk Schwaben and the Bezirk Schwaben. Augsburg is an urban district and home to the institutions of the Landkreis Augsburg. It is, as of 2008, the third-largest city in Bavaria with a...

, Bavaria

Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria was a German state that existed from 1806 to 1918. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian IV Joseph of the House of Wittelsbach became the first King of Bavaria in 1806 as Maximilian I Joseph. The monarchy would remain held by the Wittelsbachs until the kingdom's dissolution in 1918...

- March 17, 1906 in Cincinnati

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

, Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

) was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed is a concept that refers to specific political actions meant to be exemplary to others...

".

As the 1860s drew to a close, Most was won over to the ideas of international socialism, an emerging political movement in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

. Most saw in the doctrines of Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

and Ferdinand Lassalle

Ferdinand Lassalle

Ferdinand Lassalle was a German-Jewish jurist and socialist political activist.-Early life:Ferdinand Lassalle was born on 11 April 1825 in Breslau , Silesia to a prosperous Jewish family descending from Upper Silesian Loslau...

a blueprint for a new egalitarian

Egalitarianism

Egalitarianism is a trend of thought that favors equality of some sort among moral agents, whether persons or animals. Emphasis is placed upon the fact that equality contains the idea of equity of quality...

society and became a fervid supporter of the Social Democracy, as the Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

movement was known in the day. Most was repeatedly arrested for his attacks on patriotism

Patriotism

Patriotism is a devotion to one's country, excluding differences caused by the dependencies of the term's meaning upon context, geography and philosophy...

and conventional religion and ethics

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions about morality—that is, concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime, etc.Major branches of ethics include:...

, and for his gospel of terrorism

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

, preached in prose and in many songs such as those in his Proletarier-Liederbuch (Proletarian Songbook). Some of his experiences in prison were recounted in the 1876 work, Die Bastille am Plötzensee: Blätter aus meinem Gefängniss-Tagebuch (The Bastille on Plötzensee: Pages from my Prison Diary).

After advocating violent action, including the use of explosive bombs, as a mechanism to bring about revolutionary change, Most was forced into exile by the government. He went to France but was forced to leave at the end of 1878, settling in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. There he founded his own newspaper, Freiheit (Freedom), with the first issue coming off the press dated January 4, 1879. Convinced by his own experience of the futility of parliamentary action, Most began to espouse the doctrine of anarchism

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

, which led to his expulsion from the German Social Democratic Party in 1880. Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, Most emigrated to the USA upon his release from prison in 1882. He promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés. Most resumed the publication of the Freiheit in New York. He was imprisoned in 1886, again in 1887, and in 1902, the last time for two months for publishing after the assassination of President McKinley

William McKinley

William McKinley, Jr. was the 25th President of the United States . He is best known for winning fiercely fought elections, while supporting the gold standard and high tariffs; he succeeded in forging a Republican coalition that for the most part dominated national politics until the 1930s...

an editorial in which he argued that it was no crime to kill a ruler. A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century....

and Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman was an anarchist known for his political activism and writing. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century....

. Most was in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

to give a speech when he fell ill. Diagnosed with erysipelas

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is an acute streptococcus bacterial infection of the deep epidermis with lymphatic spread.-Risk factors:...

, doctors could do little for him, and he died a few days later.

German individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism refers to several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and his or her will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a...

, called "egoism," or egoist anarchism

Egoist anarchism

Egoist anarchism is a school of anarchist thought that originated in the philosophy of Max Stirner, a nineteenth century Hegelian philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best-known exponents of...

, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, the German Max Stirner

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt , better known as Max Stirner , was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism...

. Stirner's The Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own is a philosophical work by German philosopher Max Stirner . This work was first published in 1845, although with a stated publication date of "1844" to confuse the Prussian censors.-Content:...

, published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy. According to Stirner, the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire, without regard for God, state, or morality. To Stirner, rights were spooks

Reification (fallacy)

Reification is a fallacy of ambiguity, when an abstraction is treated as if it were a concrete, real event, or physical entity. In other words, it is the error of treating as a "real thing" something which is not a real thing, but merely an idea...

in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the individuals are its reality". Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists

Union of egoists

Max Stirner's idea of the "Union of Egoists" , was first expounded in The Ego and Its Own. The Union is understood as a non-systematic association, which Stirner proposed in contradistinction to the state. The Union is understood as a relation between egoists which is continually renewed by all...

, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will, which Stirner proposed as a form of organization in place of the state

State (polity)

A state is an organized political community, living under a government. States may be sovereign and may enjoy a monopoly on the legal initiation of force and are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union...

. Egoist anarchists claim that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals. "Egoism" has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy. It was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT

LGBT

LGBT is an initialism that collectively refers to "lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender" people. In use since the 1990s, the term "LGBT" is an adaptation of the initialism "LGB", which itself started replacing the phrase "gay community" beginning in the mid-to-late 1980s, which many within the...

activist John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay was an individualist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of Die Anarchisten and Der Freiheitsucher . Mackay was published in the United States in his friend Benjamin Tucker's magazine, Liberty...

.

John Henry Mackay

In GermanyGermany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

the Scottish-born German John Henry Mackay became the most important individualist anarchist propagandist. He fused Stirnerist egoism with the positions of Benjamin Tucker and translated Tucker into German. Two semi-fictional writings of his own Die Anarchisten

Die Anarchisten

Die Anarchisten: Kulturgemälde aus dem Ende des XIX Jahrhunderts is a book by anarchist writer John Henry Mackay published in German and English in 1891. It is the best known and most widely read of Mackay's works, and made him famous overnight...

and Der Freiheitsucher contributed to individualist theory, updating egoist themes with respect to the anarchist movement. His writing were translated into English as well. Mackay is also an important European early activist for LGBT

LGBT

LGBT is an initialism that collectively refers to "lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender" people. In use since the 1990s, the term "LGBT" is an adaptation of the initialism "LGB", which itself started replacing the phrase "gay community" beginning in the mid-to-late 1980s, which many within the...

rights.

Adolf Brand

Adolf Brand (1874–1945) was a GermanGermany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

writer

Writer

A writer is a person who produces literature, such as novels, short stories, plays, screenplays, poetry, or other literary art. Skilled writers are able to use language to portray ideas and images....

, Stirnerist anarchist

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality

Bisexuality

Bisexuality is sexual behavior or an orientation involving physical or romantic attraction to both males and females, especially with regard to men and women. It is one of the three main classifications of sexual orientation, along with a heterosexual and a homosexual orientation, all a part of the...

and homosexuality

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

. Brand published the world's first ongoing homosexual publication, Der Eigene

Der Eigene

Der Eigene was the first gay journal in the world, published from 1896 to 1932 by Adolf Brand in Berlin. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself...

in 1896. The name was taken from Stirner, who had greatly influenced the young Brand, and refers to Stirner's concept of "self-ownership

Self-ownership

Self-ownership is the concept of property in one's own person, expressed as the moral or natural right of a person to be the exclusive controller of his own body and life. According to G...

" of the individual. Der Eigene

Der Eigene

Der Eigene was the first gay journal in the world, published from 1896 to 1932 by Adolf Brand in Berlin. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself...

concentrated on cultural and scholarly material, and may have averaged around 1500 subscribers per issue during its lifetime. Contributors included Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic....

, Kurt Hiller

Kurt Hiller

Kurt Hiller also known as Keith Lurr and Klirr was a German essayist of high stylistic originality and a political journalist from a Jewish family. A socialist, he was deeply influenced by Immanuel Kant and Arthur Schopenhauer, despising the philosophy of G. W. F...

, John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay was an individualist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of Die Anarchisten and Der Freiheitsucher . Mackay was published in the United States in his friend Benjamin Tucker's magazine, Liberty...

(under the pseudonym Sagitta) and artists Wilhelm von Gloeden

Wilhelm von Gloeden

Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden was a German photographer who worked mainly in Italy. He is mostly known for his pastoral nude studies of Sicilian boys, which usually featured props such as wreaths or amphoras suggesting a setting in the Greece or Italy of antiquity...

, Fidus

Fidus

Fidus was the pseudonym used by German illustrator, painter and publisher Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener . He was a symbolist artist, whose work directly influenced the psychedelic style of graphic design of the late 1960s.Born the son of a confectioner in Lübeck, Höppener demonstrated...

and Sascha Schneider

Sascha Schneider

Rudolph Karl Alexander Schneider, commonly known as Sascha Schneider , was a German painter and sculptor.-Biography :...

. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself. Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker was a proponent of American individualist anarchism in the 19th century, and editor and publisher of the individualist anarchist periodical Liberty.-Summary:Tucker says that he became an anarchist at the age of 18...

followed this journal from the United States.

Anselm Ruest (Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (Salomo Friedlaender)

Der Einzige was the title of a German individualist anarchist magazine. It appeared in 1919, as a weekly, then sporadically until 1925 and was edited by cousins Anselm Ruest (pseud. for Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (pseud. for Salomo Friedlaender). Its title was adopted from the book Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (engl. trans. The Ego and Its OwnThe Ego and Its Own

The Ego and Its Own is a philosophical work by German philosopher Max Stirner . This work was first published in 1845, although with a stated publication date of "1844" to confuse the Prussian censors.-Content:...

) by Max Stirner

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt , better known as Max Stirner , was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism...

. Another influence was the thought of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

. The publication was connected to the local expressionist

Expressionism

Expressionism was a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas...

artistic current and the transition from it towards dada

Dada

Dada or Dadaism is a cultural movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland, during World War I and peaked from 1916 to 1922. The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature—poetry, art manifestoes, art theory—theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a...

.

Anarchism in the German Revolution of 1918-1919 and under nazism

In the German uprising known as the Bavarian Soviet RepublicBavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Munich Soviet Republic was, as part of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the short-lived attempt to establish a socialist state in form of a council republic in the Free State of Bavaria. It sought independence from the also recently proclaimed...

the anarchists Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer was one of the leading theorists on anarchism in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism and an avowed pacifist. Landauer is also known for his study and translations of William Shakespeare's works into German...

, Silvio Gesell

Silvio Gesell

Silvio Gesell was a German merchant, theoretical economist, social activist, anarchist and founder of Freiwirtschaft.-Life:...

and Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic....

had important leadership positions within the revolutionary councilist

Council communism

Council communism is a current of libertarian Marxism that emerged out of the November Revolution in the 1920s, characterized by its opposition to state capitalism/state socialism as well as its advocacy of workers' councils as the basis for workers' democracy.Originally affiliated with the...

structures. On 6 April 1919, a Soviet Republic was formally proclaimed. Initially, it was ruled by USPD members such as Ernst Toller

Ernst Toller

Ernst Toller was a left-wing German playwright, best known for his Expressionist plays and serving as President of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, for six days.- Biography :...

, and anarchists like Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer was one of the leading theorists on anarchism in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism and an avowed pacifist. Landauer is also known for his study and translations of William Shakespeare's works into German...

, Silvio Gesell

Silvio Gesell

Silvio Gesell was a German merchant, theoretical economist, social activist, anarchist and founder of Freiwirtschaft.-Life:...

and Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic....

.

Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer (7 April 1870 in KarlsruheKarlsruhe

The City of Karlsruhe is a city in the southwest of Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg, located near the French-German border.Karlsruhe was founded in 1715 as Karlsruhe Palace, when Germany was a series of principalities and city states...

, Baden

Baden

Baden is a historical state on the east bank of the Rhine in the southwest of Germany, now the western part of the Baden-Württemberg of Germany....

— 2 May 1919 in Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

) was one of the leading theorists on anarchism

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism

Anarchist communism

Anarchist communism is a theory of anarchism which advocates the abolition of the state, markets, money, private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership of the means of production, direct democracy and a horizontal network of voluntary associations and workers' councils with...

and an avowed pacifist

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

. At the "International Convention of Socialist Workers" of the II. Socialist International

Socialist International

The Socialist International is a worldwide organization of democratic socialist, social democratic and labour political parties. It was formed in 1951.- History :...

in August 1893 in Zurich, Landauer, as a delegate for the Berlin anarchists, stood for an "anarchist socialism". Against an anarchist minority the convention with 411 delegates from 20 countries passed a resolution in favour of participation in elections and political action in parliaments. The anarchists were excluded from the II. Socialist International. From 1909 to 1915 Landauer published the magazine "The Socialist" (Der Sozialist) in Berlin, which was considered to be the mouthpiece of the "Socialist Federation" (Sozialistischer Bund) founded by Landauer in 1908. Among the first members were Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic....

and Martin Buber

Martin Buber

Martin Buber was an Austrian-born Jewish philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of religious existentialism centered on the distinction between the I-Thou relationship and the I-It relationship....

. When the soviet republic was proclaimed on 7 April 1919 against the elected government of Johannes Hoffmann

Johannes Hoffmann

Johannes Hoffmann was a Bavarian Minister-President and member of the SPD.-Life:Born in Ilbesheim, near Landau, his parents were Peter Hoffmann and Maria Eva Keller...

, Landauer became Commissioner of Enlightenment and Public Instruction. After the City of Munich was reconquered by the German army and Freikorps

Freikorps

Freikorps are German volunteer military or paramilitary units. The term was originally applied to voluntary armies formed in German lands from the middle of the 18th century onwards. Between World War I and World War II the term was also used for the paramilitary organizations that arose during...

units, Gustav Landauer was arrested on 1 May 1919 and stoned to death by troopers one day later in Munich's Stadelheim Prison

Stadelheim Prison

Stadelheim Prison, in Munich's Giesing district, is one of the largest prisons in Germany.Founded in 1894 it was the site of many executions, particularly by guillotine during the Nazi period.-Notable inmates:...

. After the Nazis were elected in Germany in 1933 they destroyed Landauer's grave, which had been erected in 1925, sent his remains to the Jewish congregation of Munich, charging them for the costs. Landauer was later put to rest at the Munich Waldfriedhof

Munich Waldfriedhof

The Munich Waldfriedhof is one of 29 cemeteries of Munich in Bavaria, Germany. It is one of the larger and more famous burial sites of the city due to its park like design and tombs of notable personalities. The Waldfriedhof is widely considered the first woodland cemetery.-Description:The Munich...

(Forest Cemetery)

Landauer supported anarchism already in the 90s of the 19th century. In those years he was especially enthusiastic about the individualistic approach of Max Stirner

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt , better known as Max Stirner , was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism...

. He didn't want to stay behind Stirner's extremely individual approach but wanted to develop a new general public, a unity and community. His "social Anarchism" was a union of individuals on a voluntary basis in small socialist communities which came together freely. Landauer's goal was always emancipation from state, church or other forms of subordination in society. The expression 'Anarchism' stems from the Greek "arche" meaning 'power', 'reign' or 'rule'. Thus 'An-archy' equals 'non-power', 'no-reign' or 'no-rule'. The rejection of the state is common to all Anarchist positions. Some also reject institutions and moral concepts, such as church, matrimony or family; the rejection is, of course, voluntary. Landauer came out against Marxists and Social Democrats, reproaching them for wanting to erect another state executing power. For him Anarchism was a spiritual movement, almost religious. In contrast to other Anarchists he did not reject matrimony; on the contrary, it was a pillar of the community in Landauer's system. True Anarchism results from the "inner segregation" of the individuals. It is exactly this from which one is to be freed. Precondition for autonomy and independence respectively is the "seclusion" which leads to a "Unity with the world". According to Landauer it is necessary to change the nature of man or at least to change his ways, so that finally the inner convictions can appear and be lived. This includes an "Anarchism of deed" that is never strictly theoretical.

Silvio Gesell

.jpg)

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

merchant

Merchant

A merchant is a businessperson who trades in commodities that were produced by others, in order to earn a profit.Merchants can be one of two types:# A wholesale merchant operates in the chain between producer and retail merchant...

, theoretical economist

Economist

An economist is a professional in the social science discipline of economics. The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy...

, social activist, anarchist and founder of Freiwirtschaft

Freiwirtschaft

is an economic idea founded by Silvio Gesell in 1916. He called it . In 1932, a group of Swiss businessmen used his ideas to found WIR....

. After the bloody end of the Soviet Republic, Gesell was held in detention for several months until being acquitted of treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

by a Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

court

Court

A court is a form of tribunal, often a governmental institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law...

because of the speech he gave in his own defense. Because of his participation in the Soviet Republic, Switzerland denied him the opportunity to return to his farm in Neuchâtel. Gesell then moved first to Nuthetal

Nuthetal

Nuthetal is a municipality in the Potsdam-Mittelmark district, in Brandenburg, Germany.-Geography:Nuthetal is situated south-west of Berlin...

, Potsdam-Mittelmark

Potsdam-Mittelmark

Potsdam-Mittelmark is a Kreis in the western part of Brandenburg, Germany. Neighboring are the district Havelland, the district free cities Brandenburg and Potsdam, the Bundesland Berlin, the district Teltow-Fläming, and the districts Wittenberg, Anhalt-Bitterfeld and Jerichower Land in...

, then back to Oranienburg. After another short stay in Argentina in 1924, he returned to Oranienburg in 1927. Here, he died of pneumonia

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung—especially affecting the microscopic air sacs —associated with fever, chest symptoms, and a lack of air space on a chest X-ray. Pneumonia is typically caused by an infection but there are a number of other causes...

on March 11, 1930.

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam (6 April 1878 – 10 July 1934) was a German-Jewish anarchistAnarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

essay

Essay

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author's personal point of view. Essays can consist of a number of elements, including: literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. The definition...

ist, poet

Poet