Reichstag fire

Encyclopedia

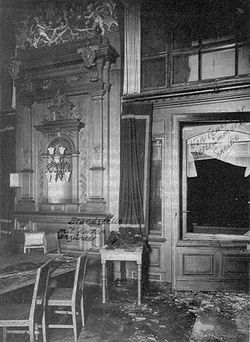

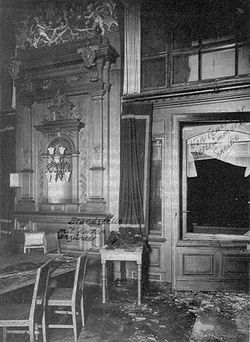

The Reichstag fire was an arson

attack on the Reichstag building

in Berlin on 27 February 1933. The event is seen as pivotal in the establishment of Nazi Germany

.

At 21:25 (UTC

+1

), a Berlin fire station received an alarm call that the Reichstag building, the assembly location of the German Parliament

, was ablaze. The fire started in the Session Chamber, and, by the time the police and firefighters had arrived, the main Chamber of Deputies

was engulfed in flames.

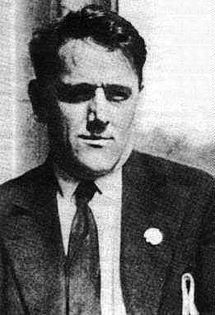

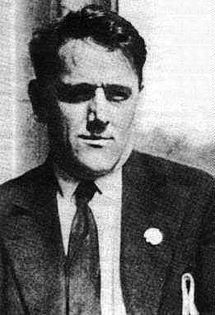

Inside the building, a thorough search conducted by the police resulted in the finding of Marinus Van der Lubbe

. Van der Lubbe, council communist and unemployed bricklayer, had recently arrived in Germany, ostensibly to carry out his political activities. The fire was used as evidence by the Nazis

that the Communists were beginning a plot against the German government. Van der Lubbe and four Communist leaders were subsequently arrested. Adolf Hitler

, who had been sworn in as Chancellor of Germany four weeks before, on 30 January, urged President Paul von Hindenburg

to pass an emergency decree to counter the "ruthless confrontation of the Communist Party of Germany

". With civil liberties suspended, the government instituted mass arrests of Communists, including all of the Communist parliamentary delegates. With them gone and their seats empty, the Nazis went from being a plurality party to the majority

; subsequent elections confirmed this position and thus allowed Hitler to consolidate his power.

Meanwhile, investigation of the Reichstag fire continued, with the Nazis eager to uncover Comintern

complicity. In early March 1933, three men were arrested who were to play pivotal roles during the Leipzig Trial

, known also as the "Reichstag Fire Trial": Bulgaria

ns Georgi Dimitrov

, Vasil Tanev and Blagoi Popov

. The Bulgarians were known to the Prussia

n police as senior Comintern operatives, but the police had no idea how senior they were; Dimitrov was head of all Comintern operations in Western Europe.

Historians disagree as to whether Van der Lubbe acted alone or whether the arson was planned and ordered by the Nazis, then dominant in the government themselves, as a false flag

operation. The responsibility for the Reichstag fire remains an ongoing topic of debate and research.

on 30 January 1933. As Chancellor, Hitler asked German President

Paul von Hindenburg

to dissolve the Reichstag

and call for a new parliamentary election

. The date set for the elections was 5 March 1933. Hitler's aim was first to acquire a National Socialist majority to secure his position and eliminate the communist opposition. If prompted or desired, the President could remove the Chancellor. Hitler hoped to abolish democracy

in a more or less legal fashion by passing the Enabling Act. The Enabling Act was a special law which gave the Chancellor the power to pass laws by decree without the involvement of the Reichstag. These special powers would remain in effect for four years, after which time they were eligible to be renewed. Under the existing Weimar constitution

, under Article 48, the President could rule by decree in times of emergency. The unprecedented element of the Enabling Act was that the Chancellor himself possessed these powers. An Enabling Act was only supposed to be passed in times of extreme emergency, and, in fact, had only been used once before, in 1923-24, when the government used an Enabling Act to rescue Germany from hyperinflation (see inflation in the Weimar Republic

). To pass an Enabling Act, a party required a vote by a two-thirds majority in the Reichstag. In January 1933, the Nazis had only 32% of the seats and thus were in no position to pass an Enabling Act.

During the election campaign, the Nazis alleged that Germany was on the verge of a Communist revolution

and that the only way to stop the Communists was to pass the Enabling Act. The message of the campaign was simple: increase the number of Nazi seats so that the Enabling Act could be passed. To decrease the number of opposition

members of parliament who could vote against the Enabling Act, Hitler had planned to ban the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands

(the Communist Party of Germany or KPD), which at the time held 17% of the parliament's seats, after the elections and before the new Reichstag convened. The Reichstag fire allowed Hitler to accelerate the banning of the Communist Party. The Nazis capitalized on the fear that the Reichstag fire was supposed to serve as a signal launching the Communist revolution in Germany and promoted this claim in the Nazi campaign.

+1

) (10:15 p.m. local time) on 27 February 1933, the Berlin Fire Department received a message that the Reichstag was on fire. Despite the best efforts of the firemen, the building was gutted by the blaze. By 11:30 p.m., the fire was put out. The firemen and policemen inspected the ruins and found twenty bundles of inflammable material (firelighters) unburned lying about. At the time the fire was reported, Adolf Hitler

was having dinner with Joseph Goebbels

at Goebbels' apartment in Berlin. When Goebbels received an urgent phone call informing him of the fire, he regarded it as a "tall tale" at first and, only after the second call, did he report the news to Hitler. Hitler, Goebbels, the Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen

and Prince Heinrich Günther von Hohenzollern were taken by car to the Reichstag, where they were met by Hermann Göring

. Göring told Hitler, "This is a Communist outrage! One of the Communist culprits has been arrested." Hitler called the fire a "sign from heaven", and claimed it was a Fanal (signal) meant to mark the beginning of a Communist Putsch (revolt). The next day, the Preussische Pressedienst (Prussian Press Service) reported that "this act of incendiarism is the most monstrous act of terrorism carried out by Bolshevism in Germany". The Vossische Zeitung

newspaper warned its readers that "the government is of the opinion that the situation is such that a danger to the state and nation existed and still exists".

, signed into law by Hindenburg using Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. The Reichstag Fire Decree suspended most civil liberties in Germany and was used by the Nazis to ban publications not considered "friendly" to the Nazi cause. Despite the fact that Marinus van der Lubbe claimed to have acted alone in the Reichstag fire, Hitler, after having obtained his emergency powers, announced that it was the start of a Communist plot to take over Germany. Nazi newspapers blared this "news". This sent the Germans into a panic and isolated the Communists further among the civilians; additionally, thousands of Communists were imprisoned in the days following the fire (including leaders of the Communist Party of Germany

) on the charge that the Party was preparing to stage a putsch. With Communist electoral participation also suppressed (the Communists had previously polled 17% of the vote), the Nazis were able to increase their share of the vote in the March 5, 1933, Reichstag elections from 33% to 44%. This gave the Nazis and their allies, the German National People's Party

(who won 8% of the vote), a majority of 52% in the Reichstag.

While the Nazis emerged with a majority, they had fallen short of their goal, which was to win 50%–55% of the vote that year. The Nazis thought that this would make it difficult to achieve their next goal, which was to pass the Enabling Act, a measure that required a two-thirds majority. However, there were important factors weighing in the Nazis' favor. These were: the continued suppression of the Communist Party and the Nazis' ability to capitalize on national security concerns. Moreover, some deputies of the Social Democratic Party (the only party that would vote against the Enabling Act) were prevented from taking their seats in the Reichstag, due to arrests and intimidation by the Nazi SA. As a result, the Social Democratic Party would be under-represented in the final vote tally. The Enabling Act, which gave Hitler the right to rule by decree, passed easily on March 23, 1933. It garnered the support of the right-wing German National People's Party, the Catholic Centre Party, and several fragmented middle-class parties. This measure went into force on March 27 and, in effect, made Hitler dictator of Germany.

_1982,_minr_block_068.jpg)

, Ernst Torgler

, Georgi Dimitrov

, Blagoi Popov

, and Vassil Tanev were indicted on charges of setting the Reichstag on fire. From September 21 to December 23, 1933, the Leipzig Trial

took place and was presided over by judges from the old German Imperial High Court, the Reichsgericht

. This was Germany's highest court. The presiding judge was Judge Dr. Wilhelm Bürger of the Fourth Criminal Court of the Fourth Penal Chamber of the Supreme Court. The accused were charged with arson and with attempting to overthrow the government.

The Leipzig Trial was widely publicized and was broadcast on the radio. It was expected that the court would find the Communists guilty on all counts and approve the repression and terror exercised by the Nazis against all opposition forces in the country. At the end of the trial, however, only Van der Lubbe was convicted, while his fellow defendants were found not guilty. In 1934, Van der Lubbe was beheaded in a German prison yard. In 1967, a court in West Berlin overturned the 1933 verdict, and posthumously changed Van der Lubbe's sentence to 8 years in prison. In 1980, another court overturned the verdict, but was overruled. In 1981, a West German court posthumously overturned Van der Lubbe's 1933 conviction and found him not guilty by reason of insanity. This ruling was subsequently overturned, but, in January 2008, he was finally pardoned under a 1998 law for the crime on the grounds that the laws under which Van der Lubbe was convicted were unconstitutional.

The Leipzig Trial was widely publicized and was broadcast on the radio. It was expected that the court would find the Communists guilty on all counts and approve the repression and terror exercised by the Nazis against all opposition forces in the country. At the end of the trial, however, only Van der Lubbe was convicted, while his fellow defendants were found not guilty. In 1934, Van der Lubbe was beheaded in a German prison yard. In 1967, a court in West Berlin overturned the 1933 verdict, and posthumously changed Van der Lubbe's sentence to 8 years in prison. In 1980, another court overturned the verdict, but was overruled. In 1981, a West German court posthumously overturned Van der Lubbe's 1933 conviction and found him not guilty by reason of insanity. This ruling was subsequently overturned, but, in January 2008, he was finally pardoned under a 1998 law for the crime on the grounds that the laws under which Van der Lubbe was convicted were unconstitutional.

The trial began at 8:45 on the morning of September 21, with Van der Lubbe testifying. Van der Lubbe's testimony was very hard to follow as he spoke of losing his sight in one eye and wandering around Europe as a drifter and that he had been a member of the Dutch Communist Party, which he quit in 1931, but still considered himself a communist. Georgi Dimitrov began his testimony on the third day of the trial. He gave up his right to a court-appointed lawyer and defended himself successfully. When warned by Judge Bürger to behave himself in court, Dimitrov stated: "Herr President, if you were a man as innocent as myself and you have passed seven months in prison, five of them in chains night and day, you would understand it if one perhaps becomes a little strained." During the course of his defence, Dimitrov claimed that the organizers of the fire were senior members of the Nazi Party and frequently verbally clashed with Göring at the trial. The highpoint of the trial occurred on November 4, 1933, when Göring took the stand and was cross-examined by Dimitrov. The following exchange took place:

In his verdict, Judge Bürger was careful to underline his belief that there had in fact been a Communist conspiracy to burn down the Reichstag, but declared, with the exception of Van der Lubbe, there was insufficient evidence to connect the accused to the fire or the alleged conspiracy. Only Van der Lubbe was found guilty and sentenced to death. The rest were acquitted and were expelled to the Soviet Union, where they received a heroic welcome. The one exception was Torgler, who was taken into "protective custody" by the police until 1935. After being released, he assumed a pseudonym and moved away from Berlin.

Hitler was furious with the outcome of this trial. He decreed that henceforth treason—among many other offenses—would only be tried by a newly established People's Court

(Volksgerichtshof). The People's Court later became associated with the number of death sentences it handed down, including those following the 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler

which were presided over by then Judge-President Roland Freisler

.

. He was beheaded by guillotine (the customary form of execution in Saxony

at the time; it was by axe in the rest of Germany) on January 10, 1934, three days before his 25th birthday. The Nazis alleged that Van der Lubbe was part of the Communist conspiracy

to burn down the Reichstag and seize power, while the Communists alleged that Van der Lubbe was part of the Nazi conspiracy to blame the crime on them. Van der Lubbe, for his part, maintained that he had acted alone to protest the condition of the German working class.

According to Ian Kershaw, writing in 1998, the consensus of nearly all historians is that Van der Lubbe did, in fact, set the Reichstag fire. Although Van der Lubbe was certainly an arsonist, and clearly played a role, there has been considerable popular and scientific debate over whether he acted alone. The case is still actively discussed.

According to Ian Kershaw, writing in 1998, the consensus of nearly all historians is that Van der Lubbe did, in fact, set the Reichstag fire. Although Van der Lubbe was certainly an arsonist, and clearly played a role, there has been considerable popular and scientific debate over whether he acted alone. The case is still actively discussed.

Considering the speed with which the fire engulfed the building, van der Lubbe's reputation as a mentally disturbed arsonist hungry for fame, and cryptic comments by leading Nazi officials, it was generally believed at the time that the Nazi hierarchy was involved for political gain. Kershaw, in Hitler Hubris, says it is generally believed today that van der Lubbe acted alone and the Reichstag fire was merely a stroke of good luck for the Nazis. It is alleged that the idea he was a "half-wit" or "mentally disturbed" was propaganda

spread by the Dutch Communist party to distance themselves from an insurrectionist anti-fascist who was once a member of the party and took action where they failed to do so. The historian Hans Mommsen

concluded that the Nazi leadershipwas in a state of panic the night of the Reichstag fire, and they seemed to have regarded the Reichstag fire as a confirmation that a Communist revolution was as imminent as they had said it was.

British reporter Sefton Delmer

witnessed the events of that night firsthand, and his account of the fire provides a number of details. Delmer reports Hitler arriving at the Reichstag and appearing genuinely uncertain how it had begun and concerned that a Communist coup was about to be launched. Delmer himself viewed van der Lubbe as being solely responsible, but that the Nazis sought to make it appear to be a "Communist gang" who set the fire, whereas the Communists sought to make it appear that van der Lubbe was working for the Nazis, each side constructing a plot-theory in which the other was the villain.

In 1960, Fritz Tobias, a West German left-leaning (SPD

) public servant and part-time historian published a series of articles in Der Spiegel

, later turned into a book, in which he argued that van der Lubbe had acted alone. At the time, Tobias was widely attacked for his articles, which showed that van der Lubbe was a pyromaniac with a long history of burning down buildings or attempting to burn down buildings. In particular, Tobias established that van der Lubbe had attempted to burn down a number of buildings in the days prior to February 27. In March 1973, the Swiss historian Walter Hofer organized a conference intended to rebut the claims made by Tobias. At the conference, Hofer claimed to have found evidence that some of the detectives who had investigated the fire may have been Nazis. Mommsen commented on Hofer's claims by stating, "Professor Hofer's rather helpless statement that the accomplices of van der Lubbe 'could only have been Nazis' is tacit admission that the committee did not actually obtain any positive evidence in regard to the alleged accomplices' identity." However, Mommsen also had a counter-study supporting Hofer, which was suppressed for political reasons -- an act that he himself, as of today, admits was a serious breach of ethics.

In contrast, in 1946, Hans Gisevius, a former member of the Gestapo

, indicated that the Nazis were the actual arsonists. Accordingly, Karl Ernst

by order of possibly Goebbels collected a commando of SA men headed by Heini Gewehr who set the fire. Among them was a criminal named Rall who later made a (suppressed) confession before he was murdered by the Gestapo. Almost all participants were murdered in the Night of the Long Knives

; Gewehr later died in the war. New work by two German authors, Bahar and Kugel, has revived the theory that the Nazis were behind the fire. It uses Gestapo

archives held in Moscow and only available to researchers since 1990. They argue that the fire was almost certainly started by the Nazis, based on the wealth of circumstantial evidence

provided by the archival material. They say that a commando group of at least three and at most ten SA men led by Hans Georg Gewehr set the fire using self-lighting incendiaries and that van der Lubbe was brought to the scene later. Der Spiegel published a 10-page response to the book, arguing that the thesis that van der Lubbe acted alone remains the most likely explanation.

's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

details how at Nuremberg

, General Franz Halder

stated in an affidavit that Hermann Göring

had joked about setting the fire:

Under cross-examination at Nuremberg, Göring was read Halder's affidavit and denied he had any involvement in the fire, characterizing Halder's statement as "utter nonsense". Göring stated:

During the summer of 1933, a counter-trial was organized in London by a group of lawyers, democrats and other anti-Nazi groups under the aegis of German Communist émigrés. The chairman of the counter-trial was Labour

During the summer of 1933, a counter-trial was organized in London by a group of lawyers, democrats and other anti-Nazi groups under the aegis of German Communist émigrés. The chairman of the counter-trial was Labour

barrister

D N Pritt

KC and the chief organiser was KPD's propaganda

chief Willi Münzenberg

. The other "judges" were Maître Piet Vermeylen

of Belgium, George Branting of Sweden, Maître Vincent de Moro-Giafferi

and Maître Gaston Bergery of France, Betsy Bakker-Nort of the Netherlands, Vald Hvidt of Denmark, and Arthur Garfield Hays

of the United States.

The counter-trial began on September 21, 1933. It lasted one week and ended with the conclusion that the defendants were innocent and the true initiators of the fire were to be found amid the leading Nazi Party elite. The counter-trial received much media attention, and Sir Stafford Cripps

delivered the opening speech. Göring was found guilty at the counter-trial. The counter-trial served as a workshop during which all possible scenarios were tested and all speeches of the defendants were prepared. Most of the "judges", such as Hays and Moro-Giafferi, complained that the atmosphere at the "Counter-trial" was more like a show trial

, with Münzenberg constantly applying pressure behind the scenes on the "judges" to deliver the "right" verdict without any regard for the truth. One of the "witnesses", a supposed SA man, appeared in court wearing a mask and claimed that it was the SA

that really set the fire; in fact, the "SA man" was really Albert Norden, the editor of the German Communist newspaper Rote Fahne. Another masked witness whom Hays described as "not very reliable" claimed that van der Lubbe was a drug-addicted homosexual who was the lover of Ernst Röhm

and a Nazi dupe. When the lawyer for Ernst Torgler

asked the counter-trial organisers to turn over the "evidence" exonerating his client, Münzenberg refused the request because he, in fact, lacked any "evidence" to exonerate or convict anyone of the crime. The counter-trial was an enormously successful publicity stunt for the German Communists. Münzenberg followed this triumph with another by writing under his name the best-selling The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror, an exposé of what Münzenberg alleged to be the Nazi conspiracy to burn down the Reichstag and blame the act on the Communists. (In fact, as with all of Münzenberg's books, the real author was one of his aides; in this case, a Czechoslovak Communist named Otto Katz.). The success of The Brown Book was subsequently followed by another best-seller published in 1934, again ghost-written by Katz, The Second Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and the Hitler Terror.

The Brown Book was divided into three parts. The first part, which traced the rise of the Nazis (or "German Fascists" as Katz called them in conformity with Comintern

practice, which forbade the use of the term Nazi), portrayed the KPD as the only genuine anti-fascist force in Germany, and featured a bitter attack on the SPD

. Formed from dissidents within the SPD, the KPD had led the communist uprisings in the early Weimar period — which the SPD had crushed. The Brown Book labeled the SPD "Social Fascists" and accused the leadership of the SPD of secretly working in close collaboration with the Nazis. The second section featured numerous examples of Nazi terror directed against Communists; no mention is made of Communist violence or non-Communist Nazi victims. The impression The Brown Book gives is that Communists are victims of Nazism, and the only victims. In addition, the second section deals with the Reichstag fire, which is described as a Nazi plot to frame the Communists, who are represented as the most dedicated opponents of Nazism. The third section deals with the supposed puppet masters behind the Nazis, who Katz, quoting remarks by Vladimir Lenin

about middle-class Jews, described as a cabal of Jewish bankers. But both books are interesting to historians, because they show a rarely admitted far-left attitude towards Jewry, especially in the last chapter of the first Brown Book, where it was claimed that Hitler was merely a front-man for a group of international Jewish bankers and that Nazi antisemitism was just a ruse to disguise that it was Jewish bankers who really ruled Nazi Germany.

at Nicomedia

has been described as a "fourth-century Reichstag fire" used to justify an extensive persecution of the Christians. According to Lactantius

, "That [Galerius

] might urge [Diocletian

] to excess of cruelty in persecution, he employed private emissaries to set the palace on fire; and some part of it having been burnt, the blame was laid on the Christians as public enemies; and the very appellation of Christian grew odious on account of that fire." Tacitus' account of the burning of Rome involved similar allegations. Modern events such as the September 11th attacks have likewise been compared to the fire.

Arson

Arson is the crime of intentionally or maliciously setting fire to structures or wildland areas. It may be distinguished from other causes such as spontaneous combustion and natural wildfires...

attack on the Reichstag building

Reichstag (building)

The Reichstag building is a historical edifice in Berlin, Germany, constructed to house the Reichstag, parliament of the German Empire. It was opened in 1894 and housed the Reichstag until 1933, when it was severely damaged in a fire. During the Nazi era, the few meetings of members of the...

in Berlin on 27 February 1933. The event is seen as pivotal in the establishment of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

.

At 21:25 (UTC

Coordinated Universal Time

Coordinated Universal Time is the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. It is one of several closely related successors to Greenwich Mean Time. Computer servers, online services and other entities that rely on having a universally accepted time use UTC for that purpose...

+1

Central European Time

Central European Time , used in most parts of the European Union, is a standard time that is 1 hour ahead of Coordinated Universal Time . The time offset from UTC can be written as +01:00...

), a Berlin fire station received an alarm call that the Reichstag building, the assembly location of the German Parliament

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

, was ablaze. The fire started in the Session Chamber, and, by the time the police and firefighters had arrived, the main Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of deputies is the name given to a legislative body such as the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or can refer to a unicameral legislature.-Description:...

was engulfed in flames.

Inside the building, a thorough search conducted by the police resulted in the finding of Marinus Van der Lubbe

Marinus van der Lubbe

Marinus van der Lubbe was a Dutch council communist convicted of, and controversially executed for, setting fire to the German Reichstag building on February 27, 1933, an event known as the Reichstag fire. ....

. Van der Lubbe, council communist and unemployed bricklayer, had recently arrived in Germany, ostensibly to carry out his political activities. The fire was used as evidence by the Nazis

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

that the Communists were beginning a plot against the German government. Van der Lubbe and four Communist leaders were subsequently arrested. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

, who had been sworn in as Chancellor of Germany four weeks before, on 30 January, urged President Paul von Hindenburg

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg was a Prussian-German field marshal, statesman, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934....

to pass an emergency decree to counter the "ruthless confrontation of the Communist Party of Germany

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

". With civil liberties suspended, the government instituted mass arrests of Communists, including all of the Communist parliamentary delegates. With them gone and their seats empty, the Nazis went from being a plurality party to the majority

Majority

A majority is a subset of a group consisting of more than half of its members. This can be compared to a plurality, which is a subset larger than any other subset; i.e. a plurality is not necessarily a majority as the largest subset may consist of less than half the group's population...

; subsequent elections confirmed this position and thus allowed Hitler to consolidate his power.

Meanwhile, investigation of the Reichstag fire continued, with the Nazis eager to uncover Comintern

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

complicity. In early March 1933, three men were arrested who were to play pivotal roles during the Leipzig Trial

Leipzig Trial

The Leipzig Trial, also known as the Reichstag Fire Trial, took place from 21 September to 23 December 1933. It involved Ernst Torgler , Georgi Dimitrov, Vasil Tanev and Blagoi Popov and Marinus van der Lubbe...

, known also as the "Reichstag Fire Trial": Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

ns Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mikhaylov , also known as Georgi Mikhaylovich Dimitrov , was a Bulgarian Communist politician...

, Vasil Tanev and Blagoi Popov

Blagoi Popov

Blagoy Popov , one of the co-defendants along with Georgi Dimitrov and Vasil Tanev in the Leipzig trial. After the trial, he moved to Moscow in February 1934. Popov studied there until 1937 when he was caught up in the Stalinist purges. He would spent the next seventeen years in a Soviet Gulag...

. The Bulgarians were known to the Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n police as senior Comintern operatives, but the police had no idea how senior they were; Dimitrov was head of all Comintern operations in Western Europe.

Historians disagree as to whether Van der Lubbe acted alone or whether the arson was planned and ordered by the Nazis, then dominant in the government themselves, as a false flag

False flag

False flag operations are covert operations designed to deceive the public in such a way that the operations appear as though they are being carried out by other entities. The name is derived from the military concept of flying false colors; that is flying the flag of a country other than one's own...

operation. The responsibility for the Reichstag fire remains an ongoing topic of debate and research.

Prelude

Hitler had been sworn in as Chancellor and head of the coalition governmentCoalition government

A coalition government is a cabinet of a parliamentary government in which several political parties cooperate. The usual reason given for this arrangement is that no party on its own can achieve a majority in the parliament...

on 30 January 1933. As Chancellor, Hitler asked German President

Reichspräsident

The Reichspräsident was the German head of state under the Weimar constitution, which was officially in force from 1919 to 1945. In English he was usually simply referred to as the President of Germany...

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg was a Prussian-German field marshal, statesman, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934....

to dissolve the Reichstag

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

and call for a new parliamentary election

Election

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy operates since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the...

. The date set for the elections was 5 March 1933. Hitler's aim was first to acquire a National Socialist majority to secure his position and eliminate the communist opposition. If prompted or desired, the President could remove the Chancellor. Hitler hoped to abolish democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

in a more or less legal fashion by passing the Enabling Act. The Enabling Act was a special law which gave the Chancellor the power to pass laws by decree without the involvement of the Reichstag. These special powers would remain in effect for four years, after which time they were eligible to be renewed. Under the existing Weimar constitution

Weimar constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich , usually known as the Weimar Constitution was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic...

, under Article 48, the President could rule by decree in times of emergency. The unprecedented element of the Enabling Act was that the Chancellor himself possessed these powers. An Enabling Act was only supposed to be passed in times of extreme emergency, and, in fact, had only been used once before, in 1923-24, when the government used an Enabling Act to rescue Germany from hyperinflation (see inflation in the Weimar Republic

Inflation in the Weimar Republic

The hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic was a three year period of hyperinflation in Germany between June 1921 and July 1924.- Analysis :...

). To pass an Enabling Act, a party required a vote by a two-thirds majority in the Reichstag. In January 1933, the Nazis had only 32% of the seats and thus were in no position to pass an Enabling Act.

During the election campaign, the Nazis alleged that Germany was on the verge of a Communist revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

and that the only way to stop the Communists was to pass the Enabling Act. The message of the campaign was simple: increase the number of Nazi seats so that the Enabling Act could be passed. To decrease the number of opposition

Opposition (politics)

In politics, the opposition comprises one or more political parties or other organized groups that are opposed to the government , party or group in political control of a city, region, state or country...

members of parliament who could vote against the Enabling Act, Hitler had planned to ban the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

(the Communist Party of Germany or KPD), which at the time held 17% of the parliament's seats, after the elections and before the new Reichstag convened. The Reichstag fire allowed Hitler to accelerate the banning of the Communist Party. The Nazis capitalized on the fear that the Reichstag fire was supposed to serve as a signal launching the Communist revolution in Germany and promoted this claim in the Nazi campaign.

The fire

At 2:15 a.m. (UTCCoordinated Universal Time

Coordinated Universal Time is the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. It is one of several closely related successors to Greenwich Mean Time. Computer servers, online services and other entities that rely on having a universally accepted time use UTC for that purpose...

+1

Central European Time

Central European Time , used in most parts of the European Union, is a standard time that is 1 hour ahead of Coordinated Universal Time . The time offset from UTC can be written as +01:00...

) (10:15 p.m. local time) on 27 February 1933, the Berlin Fire Department received a message that the Reichstag was on fire. Despite the best efforts of the firemen, the building was gutted by the blaze. By 11:30 p.m., the fire was put out. The firemen and policemen inspected the ruins and found twenty bundles of inflammable material (firelighters) unburned lying about. At the time the fire was reported, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

was having dinner with Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

at Goebbels' apartment in Berlin. When Goebbels received an urgent phone call informing him of the fire, he regarded it as a "tall tale" at first and, only after the second call, did he report the news to Hitler. Hitler, Goebbels, the Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz von Papen

Lieutenant-Colonel Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen zu Köningen was a German nobleman, Roman Catholic monarchist politician, General Staff officer, and diplomat, who served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and as Vice-Chancellor under Adolf Hitler in 1933–1934...

and Prince Heinrich Günther von Hohenzollern were taken by car to the Reichstag, where they were met by Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

. Göring told Hitler, "This is a Communist outrage! One of the Communist culprits has been arrested." Hitler called the fire a "sign from heaven", and claimed it was a Fanal (signal) meant to mark the beginning of a Communist Putsch (revolt). The next day, the Preussische Pressedienst (Prussian Press Service) reported that "this act of incendiarism is the most monstrous act of terrorism carried out by Bolshevism in Germany". The Vossische Zeitung

Vossische Zeitung

The Vossische Zeitung was the well known liberal German newspaper that was published in Berlin . Its predecessor was founded in 1704...

newspaper warned its readers that "the government is of the opinion that the situation is such that a danger to the state and nation existed and still exists".

Political consequences

The day after the fire Hitler asked for and received from President Hindenburg the Reichstag Fire DecreeReichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State issued by German President Paul von Hindenburg in direct response to the Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933. The decree nullified many of the key civil liberties of German...

, signed into law by Hindenburg using Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. The Reichstag Fire Decree suspended most civil liberties in Germany and was used by the Nazis to ban publications not considered "friendly" to the Nazi cause. Despite the fact that Marinus van der Lubbe claimed to have acted alone in the Reichstag fire, Hitler, after having obtained his emergency powers, announced that it was the start of a Communist plot to take over Germany. Nazi newspapers blared this "news". This sent the Germans into a panic and isolated the Communists further among the civilians; additionally, thousands of Communists were imprisoned in the days following the fire (including leaders of the Communist Party of Germany

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

) on the charge that the Party was preparing to stage a putsch. With Communist electoral participation also suppressed (the Communists had previously polled 17% of the vote), the Nazis were able to increase their share of the vote in the March 5, 1933, Reichstag elections from 33% to 44%. This gave the Nazis and their allies, the German National People's Party

German National People's Party

The German National People's Party was a national conservative party in Germany during the time of the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the NSDAP it was the main nationalist party in Weimar Germany composed of nationalists, reactionary monarchists, völkisch, and antisemitic elements, and...

(who won 8% of the vote), a majority of 52% in the Reichstag.

While the Nazis emerged with a majority, they had fallen short of their goal, which was to win 50%–55% of the vote that year. The Nazis thought that this would make it difficult to achieve their next goal, which was to pass the Enabling Act, a measure that required a two-thirds majority. However, there were important factors weighing in the Nazis' favor. These were: the continued suppression of the Communist Party and the Nazis' ability to capitalize on national security concerns. Moreover, some deputies of the Social Democratic Party (the only party that would vote against the Enabling Act) were prevented from taking their seats in the Reichstag, due to arrests and intimidation by the Nazi SA. As a result, the Social Democratic Party would be under-represented in the final vote tally. The Enabling Act, which gave Hitler the right to rule by decree, passed easily on March 23, 1933. It garnered the support of the right-wing German National People's Party, the Catholic Centre Party, and several fragmented middle-class parties. This measure went into force on March 27 and, in effect, made Hitler dictator of Germany.

_1982,_minr_block_068.jpg)

Reichstag fire trial

In July 1933, Marinus van der LubbeMarinus van der Lubbe

Marinus van der Lubbe was a Dutch council communist convicted of, and controversially executed for, setting fire to the German Reichstag building on February 27, 1933, an event known as the Reichstag fire. ....

, Ernst Torgler

Ernst Torgler

Ernst Torgler was a controversial member of the Communist Party of Germany prior to World War II and a defendant in the Reichstag Fire Trial.-Biography:...

, Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mikhaylov , also known as Georgi Mikhaylovich Dimitrov , was a Bulgarian Communist politician...

, Blagoi Popov

Blagoi Popov

Blagoy Popov , one of the co-defendants along with Georgi Dimitrov and Vasil Tanev in the Leipzig trial. After the trial, he moved to Moscow in February 1934. Popov studied there until 1937 when he was caught up in the Stalinist purges. He would spent the next seventeen years in a Soviet Gulag...

, and Vassil Tanev were indicted on charges of setting the Reichstag on fire. From September 21 to December 23, 1933, the Leipzig Trial

Leipzig Trial

The Leipzig Trial, also known as the Reichstag Fire Trial, took place from 21 September to 23 December 1933. It involved Ernst Torgler , Georgi Dimitrov, Vasil Tanev and Blagoi Popov and Marinus van der Lubbe...

took place and was presided over by judges from the old German Imperial High Court, the Reichsgericht

Reichsgericht

The Reichsgericht was the highest court of the Deutsches Reich. It was established on October 1, 1879 when the Reichsjustizgesetze came into effect, building a widely regarded body of jurisprudence....

. This was Germany's highest court. The presiding judge was Judge Dr. Wilhelm Bürger of the Fourth Criminal Court of the Fourth Penal Chamber of the Supreme Court. The accused were charged with arson and with attempting to overthrow the government.

The trial began at 8:45 on the morning of September 21, with Van der Lubbe testifying. Van der Lubbe's testimony was very hard to follow as he spoke of losing his sight in one eye and wandering around Europe as a drifter and that he had been a member of the Dutch Communist Party, which he quit in 1931, but still considered himself a communist. Georgi Dimitrov began his testimony on the third day of the trial. He gave up his right to a court-appointed lawyer and defended himself successfully. When warned by Judge Bürger to behave himself in court, Dimitrov stated: "Herr President, if you were a man as innocent as myself and you have passed seven months in prison, five of them in chains night and day, you would understand it if one perhaps becomes a little strained." During the course of his defence, Dimitrov claimed that the organizers of the fire were senior members of the Nazi Party and frequently verbally clashed with Göring at the trial. The highpoint of the trial occurred on November 4, 1933, when Göring took the stand and was cross-examined by Dimitrov. The following exchange took place:

In his verdict, Judge Bürger was careful to underline his belief that there had in fact been a Communist conspiracy to burn down the Reichstag, but declared, with the exception of Van der Lubbe, there was insufficient evidence to connect the accused to the fire or the alleged conspiracy. Only Van der Lubbe was found guilty and sentenced to death. The rest were acquitted and were expelled to the Soviet Union, where they received a heroic welcome. The one exception was Torgler, who was taken into "protective custody" by the police until 1935. After being released, he assumed a pseudonym and moved away from Berlin.

Hitler was furious with the outcome of this trial. He decreed that henceforth treason—among many other offenses—would only be tried by a newly established People's Court

People's Court (German)

The People's Court was a court established in 1934 by German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, who had been dissatisfied with the outcome of the Reichstag Fire Trial . The "People's Court" was set up outside the operations of the constitutional frame of law...

(Volksgerichtshof). The People's Court later became associated with the number of death sentences it handed down, including those following the 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler

July 20 Plot

On 20 July 1944, an attempt was made to assassinate Adolf Hitler, Führer of the Third Reich, inside his Wolf's Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg, East Prussia. The plot was the culmination of the efforts of several groups in the German Resistance to overthrow the Nazi-led German government...

which were presided over by then Judge-President Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler was a prominent and notorious Nazi lawyer and judge. He was State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice and President of the People's Court , which was set up outside constitutional authority...

.

Execution of Van der Lubbe

At his trial, Van der Lubbe was found guilty and sentenced to deathCapital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

. He was beheaded by guillotine (the customary form of execution in Saxony

Saxony

The Free State of Saxony is a landlocked state of Germany, contingent with Brandenburg, Saxony Anhalt, Thuringia, Bavaria, the Czech Republic and Poland. It is the tenth-largest German state in area, with of Germany's sixteen states....

at the time; it was by axe in the rest of Germany) on January 10, 1934, three days before his 25th birthday. The Nazis alleged that Van der Lubbe was part of the Communist conspiracy

Conspiracy (political)

In a political sense, conspiracy refers to a group of persons united in the goal of usurping or overthrowing an established political power. Typically, the final goal is to gain power through a revolutionary coup d'état or through assassination....

to burn down the Reichstag and seize power, while the Communists alleged that Van der Lubbe was part of the Nazi conspiracy to blame the crime on them. Van der Lubbe, for his part, maintained that he had acted alone to protest the condition of the German working class.

Dispute about van der Lubbe's role in the Reichstag fire

Considering the speed with which the fire engulfed the building, van der Lubbe's reputation as a mentally disturbed arsonist hungry for fame, and cryptic comments by leading Nazi officials, it was generally believed at the time that the Nazi hierarchy was involved for political gain. Kershaw, in Hitler Hubris, says it is generally believed today that van der Lubbe acted alone and the Reichstag fire was merely a stroke of good luck for the Nazis. It is alleged that the idea he was a "half-wit" or "mentally disturbed" was propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

spread by the Dutch Communist party to distance themselves from an insurrectionist anti-fascist who was once a member of the party and took action where they failed to do so. The historian Hans Mommsen

Hans Mommsen

Hans Mommsen is a left-wing German historian. He is the twin brother of the late Wolfgang Mommsen.-Biography:He was born in Marburg, the son of the historian Wilhelm Mommsen and great-grandson of the Roman historian Theodor Mommsen. He studied German, history and philosophy at the University of...

concluded that the Nazi leadershipwas in a state of panic the night of the Reichstag fire, and they seemed to have regarded the Reichstag fire as a confirmation that a Communist revolution was as imminent as they had said it was.

British reporter Sefton Delmer

Sefton Delmer

Denis Sefton Delmer was a British journalist and propagandist for the British government. Fluent in German, he became friendly with Ernst Röhm who arranged for him to interview Adolf Hitler in the 1930s...

witnessed the events of that night firsthand, and his account of the fire provides a number of details. Delmer reports Hitler arriving at the Reichstag and appearing genuinely uncertain how it had begun and concerned that a Communist coup was about to be launched. Delmer himself viewed van der Lubbe as being solely responsible, but that the Nazis sought to make it appear to be a "Communist gang" who set the fire, whereas the Communists sought to make it appear that van der Lubbe was working for the Nazis, each side constructing a plot-theory in which the other was the villain.

In 1960, Fritz Tobias, a West German left-leaning (SPD

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

) public servant and part-time historian published a series of articles in Der Spiegel

Der Spiegel

Der Spiegel is a German weekly news magazine published in Hamburg. It is one of Europe's largest publications of its kind, with a weekly circulation of more than one million.-Overview:...

, later turned into a book, in which he argued that van der Lubbe had acted alone. At the time, Tobias was widely attacked for his articles, which showed that van der Lubbe was a pyromaniac with a long history of burning down buildings or attempting to burn down buildings. In particular, Tobias established that van der Lubbe had attempted to burn down a number of buildings in the days prior to February 27. In March 1973, the Swiss historian Walter Hofer organized a conference intended to rebut the claims made by Tobias. At the conference, Hofer claimed to have found evidence that some of the detectives who had investigated the fire may have been Nazis. Mommsen commented on Hofer's claims by stating, "Professor Hofer's rather helpless statement that the accomplices of van der Lubbe 'could only have been Nazis' is tacit admission that the committee did not actually obtain any positive evidence in regard to the alleged accomplices' identity." However, Mommsen also had a counter-study supporting Hofer, which was suppressed for political reasons -- an act that he himself, as of today, admits was a serious breach of ethics.

In contrast, in 1946, Hans Gisevius, a former member of the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

, indicated that the Nazis were the actual arsonists. Accordingly, Karl Ernst

Karl Ernst

Karl Ernst was an SA Gruppenführer who, in early 1933, was the SA leader in Berlin. Before joining the NSDAP he had been a hotel bell-boy and a bouncer at a gay nightclub....

by order of possibly Goebbels collected a commando of SA men headed by Heini Gewehr who set the fire. Among them was a criminal named Rall who later made a (suppressed) confession before he was murdered by the Gestapo. Almost all participants were murdered in the Night of the Long Knives

Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives , sometimes called "Operation Hummingbird " or in Germany the "Röhm-Putsch," was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany between June 30 and July 2, 1934, when the Nazi regime carried out a series of political murders...

; Gewehr later died in the war. New work by two German authors, Bahar and Kugel, has revived the theory that the Nazis were behind the fire. It uses Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

archives held in Moscow and only available to researchers since 1990. They argue that the fire was almost certainly started by the Nazis, based on the wealth of circumstantial evidence

Circumstantial evidence

Circumstantial evidence is evidence in which an inference is required to connect it to a conclusion of fact, like a fingerprint at the scene of a crime...

provided by the archival material. They say that a commando group of at least three and at most ten SA men led by Hans Georg Gewehr set the fire using self-lighting incendiaries and that van der Lubbe was brought to the scene later. Der Spiegel published a 10-page response to the book, arguing that the thesis that van der Lubbe acted alone remains the most likely explanation.

Göring's commentary

William L. ShirerWilliam L. Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer was an American journalist, war correspondent, and historian, who wrote The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, a history of Nazi Germany read and cited in scholarly works for more than 50 years...

's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich is a 1960 non-fiction book by William L. Shirer chronicling the general history of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945...

details how at Nuremberg

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

, General Franz Halder

Franz Halder

Franz Halder was a German General and the head of the Army General Staff from 1938 until September, 1942, when he was dismissed after frequent disagreements with Adolf Hitler.-Early life:...

stated in an affidavit that Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

had joked about setting the fire:

On the occasion of a lunch on the Führer's birthday in 1943, the people around the Führer turned the conversation to the Reichstag building and its artistic value. I heard with my own ears how Göring broke into the conversation and shouted: 'The only one who really knows about the Reichstag building is I, for I set fire to it.' And saying this he slapped his thigh.

Under cross-examination at Nuremberg, Göring was read Halder's affidavit and denied he had any involvement in the fire, characterizing Halder's statement as "utter nonsense". Göring stated:

I had no reason or motive for setting fire to the Reichstag. From the artistic point of view I did not at all regret that the assembly chamber was burned; I hoped to build a better one. But I did regret very much that I was forced to find a new meeting place for the Reichstag and, not being able to find one, I had to give up my Kroll Opera HouseKrolloperThe Kroll Opera House was an opera building in Berlin, Germany, located in the central Tiergarten district on the western edge of the Königsplatz square , facing the Reichstag building. It was built in 1844 as an entertainment venue for the restaurant owner Joseph Kroll...

… for that purpose. The opera seemed to me much more important than the Reichstag.

Counter-trial organized by the German Communist Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

D N Pritt

Denis Nowell Pritt

Denis Nowell Pritt , usually known as D.N. Pritt, was a British barrister and Labour Party politician. Born in Harlesden, Middlesex, he was educated at Winchester College and London University....

KC and the chief organiser was KPD's propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

chief Willi Münzenberg

Willi Münzenberg

Willi Münzenberg was a communist political activist. Münzenberg was the first head of the Young Communist International in 1919-20 and established the famine-relief and propaganda organization Workers International Relief in 1921...

. The other "judges" were Maître Piet Vermeylen

Piet Vermeylen

Piet Vermeylen , was a Belgian lawyer, and Belgian Socialist politician and minister. He was the son of the Flemish politician August Vermeylen.-Early life:...

of Belgium, George Branting of Sweden, Maître Vincent de Moro-Giafferi

Vincent de Moro-Giafferi

Vincent de Moro-Giafferi was a French criminal attorney.Moro-Giafferi was the youngest person ever appointed to the Paris bar at the age of 24. Also active in politics, he was made a Deputy to the French National Assembly from Corsica at the age of 31 in 1919...

and Maître Gaston Bergery of France, Betsy Bakker-Nort of the Netherlands, Vald Hvidt of Denmark, and Arthur Garfield Hays

Arthur Garfield Hays

Arthur Garfield Hays was a lawyer born in Rochester, New York. His father and mother, both of German descent, belonged to prospering families in the clothing manufacturing industry...

of the United States.

The counter-trial began on September 21, 1933. It lasted one week and ended with the conclusion that the defendants were innocent and the true initiators of the fire were to be found amid the leading Nazi Party elite. The counter-trial received much media attention, and Sir Stafford Cripps

Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour politician of the first half of the 20th century. During World War II he served in a number of positions in the wartime coalition, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union and Minister of Aircraft Production...

delivered the opening speech. Göring was found guilty at the counter-trial. The counter-trial served as a workshop during which all possible scenarios were tested and all speeches of the defendants were prepared. Most of the "judges", such as Hays and Moro-Giafferi, complained that the atmosphere at the "Counter-trial" was more like a show trial

Show trial

The term show trial is a pejorative description of a type of highly public trial in which there is a strong connotation that the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal to present the accusation and the verdict to the public as...

, with Münzenberg constantly applying pressure behind the scenes on the "judges" to deliver the "right" verdict without any regard for the truth. One of the "witnesses", a supposed SA man, appeared in court wearing a mask and claimed that it was the SA

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

that really set the fire; in fact, the "SA man" was really Albert Norden, the editor of the German Communist newspaper Rote Fahne. Another masked witness whom Hays described as "not very reliable" claimed that van der Lubbe was a drug-addicted homosexual who was the lover of Ernst Röhm

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Röhm, was a German officer in the Bavarian Army and later an early Nazi leader. He was a co-founder of the Sturmabteilung , the Nazi Party militia, and later was its commander...

and a Nazi dupe. When the lawyer for Ernst Torgler

Ernst Torgler

Ernst Torgler was a controversial member of the Communist Party of Germany prior to World War II and a defendant in the Reichstag Fire Trial.-Biography:...

asked the counter-trial organisers to turn over the "evidence" exonerating his client, Münzenberg refused the request because he, in fact, lacked any "evidence" to exonerate or convict anyone of the crime. The counter-trial was an enormously successful publicity stunt for the German Communists. Münzenberg followed this triumph with another by writing under his name the best-selling The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror, an exposé of what Münzenberg alleged to be the Nazi conspiracy to burn down the Reichstag and blame the act on the Communists. (In fact, as with all of Münzenberg's books, the real author was one of his aides; in this case, a Czechoslovak Communist named Otto Katz.). The success of The Brown Book was subsequently followed by another best-seller published in 1934, again ghost-written by Katz, The Second Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and the Hitler Terror.

The Brown Book was divided into three parts. The first part, which traced the rise of the Nazis (or "German Fascists" as Katz called them in conformity with Comintern

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

practice, which forbade the use of the term Nazi), portrayed the KPD as the only genuine anti-fascist force in Germany, and featured a bitter attack on the SPD

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

. Formed from dissidents within the SPD, the KPD had led the communist uprisings in the early Weimar period — which the SPD had crushed. The Brown Book labeled the SPD "Social Fascists" and accused the leadership of the SPD of secretly working in close collaboration with the Nazis. The second section featured numerous examples of Nazi terror directed against Communists; no mention is made of Communist violence or non-Communist Nazi victims. The impression The Brown Book gives is that Communists are victims of Nazism, and the only victims. In addition, the second section deals with the Reichstag fire, which is described as a Nazi plot to frame the Communists, who are represented as the most dedicated opponents of Nazism. The third section deals with the supposed puppet masters behind the Nazis, who Katz, quoting remarks by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

about middle-class Jews, described as a cabal of Jewish bankers. But both books are interesting to historians, because they show a rarely admitted far-left attitude towards Jewry, especially in the last chapter of the first Brown Book, where it was claimed that Hitler was merely a front-man for a group of international Jewish bankers and that Nazi antisemitism was just a ruse to disguise that it was Jewish bankers who really ruled Nazi Germany.

As archetype

In modern histories the destruction of the palace of DiocletianDiocletian

Diocletian |latinized]] upon his accession to Diocletian . c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a Roman Emperor from 284 to 305....

at Nicomedia

Nicomedia

Nicomedia was an ancient city in what is now Turkey, founded in 712/11 BC as a Megarian colony and was originally known as Astacus . After being destroyed by Lysimachus, it was rebuilt by Nicomedes I of Bithynia in 264 BC under the name of Nicomedia, and has ever since been one of the most...

has been described as a "fourth-century Reichstag fire" used to justify an extensive persecution of the Christians. According to Lactantius

Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius was an early Christian author who became an advisor to the first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his religious policy as it developed, and tutor to his son.-Biography:...

, "That [Galerius

Galerius

Galerius , was Roman Emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sassanid Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the Danube against the Carpi, defeating them in 297 and 300...

] might urge [Diocletian

Diocletian

Diocletian |latinized]] upon his accession to Diocletian . c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a Roman Emperor from 284 to 305....

] to excess of cruelty in persecution, he employed private emissaries to set the palace on fire; and some part of it having been burnt, the blame was laid on the Christians as public enemies; and the very appellation of Christian grew odious on account of that fire." Tacitus' account of the burning of Rome involved similar allegations. Modern events such as the September 11th attacks have likewise been compared to the fire.