Asymmetric induction

Encyclopedia

Asymmetric induction in stereochemistry

describes the preferential formation in a chemical reaction

of one enantiomer

or diastereoisomer over the other as a result of the influence of a chiral feature present in the substrate

, reagent

, catalyst or environment. Asymmetric induction is a key element in asymmetric synthesis.

Asymmetric induction was introduced by Emil Fischer

based on his work on carbohydrate

s. Several types of induction exist.

Internal asymmetric induction makes use of a chiral center bound to the reactive center through a covalent bond

and remains so during the reaction. The starting material is often derived from chiral pool synthesis

. In relayed asymmetric induction the chiral information is introduced in a separate step and removed again in a separate chemical reaction. Special synthons are called chiral auxiliaries

. In external asymmetric induction chiral information is introduced in the transition state

through a catalyst of chiral ligand

. This method of asymmetric synthesis is economically most desirable.

in 1952 is an early concept relating to the prediction of stereochemistry in certain acyclic

systems. In full the rule is:

In certain non-catalytic reactions that diastereomer will predominate, which could be formed by the approach of the entering group from the least hindered side when the rotational conformation of the C-C bond is such that the double bond is flanked by the two least bulky groups attached to the adjacent asymmetric center.

The rule indicates that the presence of an asymmetric center in a molecule induces the formation of an asymmetric center adjacent to it based on steric hindrance.

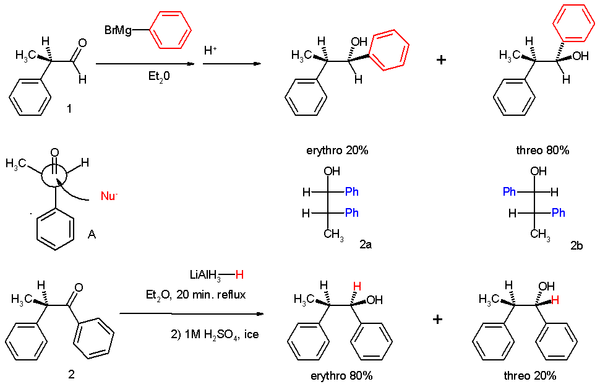

In his 1952 publication Cram presented a large number of reactions described in the literature for which the conformation of the reaction products could be explained based on this rule and he also described an elaborate experiment (scheme 1) making his case.

The experiments involved two reactions. In experiment one 2-phenylpropionaldehyde (1, racemic

but (R)-enantiomer shown) was reacted with the Grignard reagent of bromobenzene to 1,2-diphenyl-1-propanol (2) as a mixture of diastereomer

s, predominantly the threo isomer

(see for explanation the Fischer projection

).

The preference for the formation of the threo isomer can be explained by the rule stated above by having the active nucleophile

in this reaction attacking the carbonyl group from the least hindered side (see Newman projection

A) when the carbonyl is positioned in a staggered

formation with the methyl group and the hydrogen

atom, which are the two smallest substituent

s creating a minimum of steric hindrance, in a gauche orientation

and phenyl as the most bulky group in the anti conformation.

The second reaction is the organic reduction of 1,2-diphenyl-1-propanone 2 with lithium aluminium hydride

, which results in the same reaction product as above but now with preference for the erythro isomer (2a). Now a hydride

anion (H-) is the nucleophile attacking from the least hindered side (imagine hydrogen entering from the paper plane).

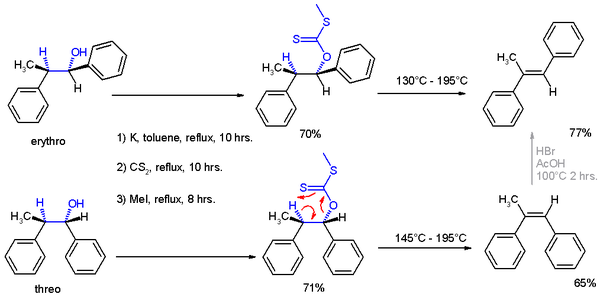

In the original 1952 publication, additional evidence was obtained for the structural assignment of the reaction products by applying them to a Chugaev elimination

, wherein the threo isomer reacts to the cis isomer of -α-methyl-stilbene

and the erythro isomer to the trans version.

also predicts the stereochemistry

of nucleophilic addition

reactions to carbonyl

groups. Felkin argued that the Cram model suffered a major drawback: an eclipsed

conformation in the transition state

between the carbonyl substituent (the hydrogen atom in aldehydes) and the largest α-carbonyl substituent. He demonstrated that by increasing the steric bulk of the carbonyl substituent from methyl to ethyl

to isopropyl

to isobutyl, the stereoselectivity

also increased, which is not predicted by Cram's rule:

The Felkin rules are:

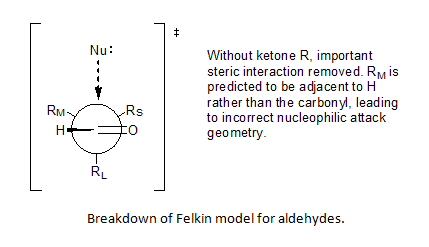

The second weakness in the Felkin Model was the assumption of substituent minimization around the carbonyl R, which cannot be applied to aldehydes.

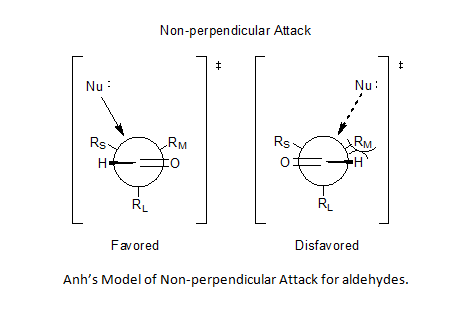

Incorporation of Bürgi–Dunitz angle ideas allowed Anh to postulate a non-perpendicular attack by the nucleophile on the carbonyl center, anywhere from 95o to 105o relative to the oxygen-carbon double bond, favoring approach closer to the smaller substituent and thereby solve the problem of predictability for aldehydes.

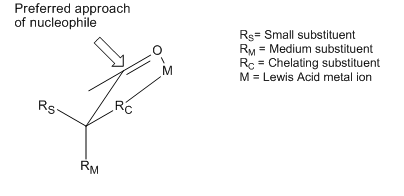

to the most sterically favored face of a carbonyl

moiety. However, many examples exist of reactions that display stereoselectivity opposite of what is predicted by the basic tenets of the Cram and Felkin–Anh models. Although both of the models include attempts to explain these reversals, the products obtained are still referred to as "anti-Felkin" products. One of the most common examples of altered asymmetric induction selectivity requires an α-carbon substituted with a component with Lewis base character (i.e. O, N, S, P substituents). In this situation, if a Lewis acid

such as Al-iPr2 or Zn2+ is introduced, a bidentate chelation

effect can be observed. This locks the carbonyl

and the Lewis base substituent in an eclipsed conformation, and the nucleophile

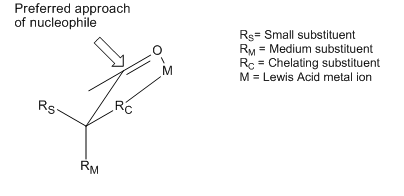

will then attack from the side with the smallest free α-carbon substituent. If the chelating R group is identified as the largest, this will result in an "anti-Felkin" product.

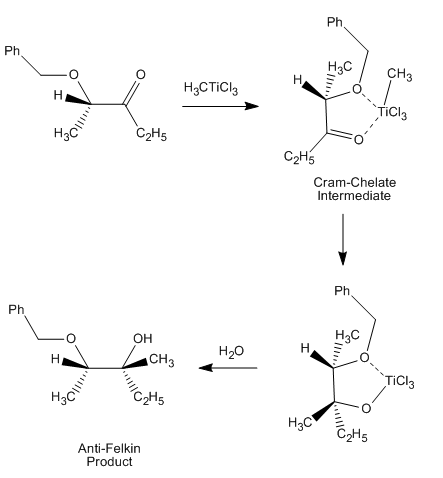

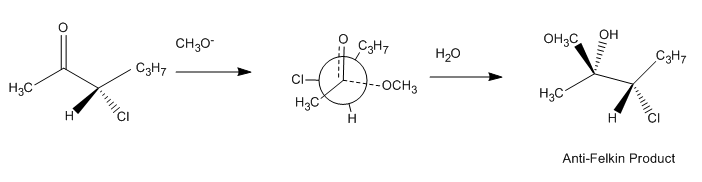

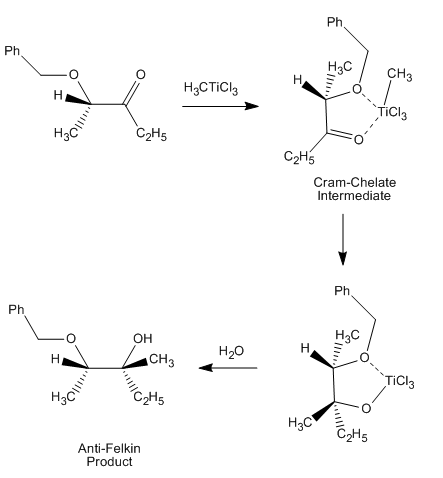

This stereoselective control was recognized and discussed in the first paper establishing the Cram model, causing Cram to assert that his model requires non-chelating conditions. An example of chelation

control of a reaction can be seen here, from a 1987 paper that was the first to directly observe such a "Cram-chelate" intermediate, vindicating the model:

Here, the methyl titanium chloride forms a Cram-chelate. The methyl group then dissociates from titanium

and attacks the carbonyl, leading to the anti-Felkin diastereomer.

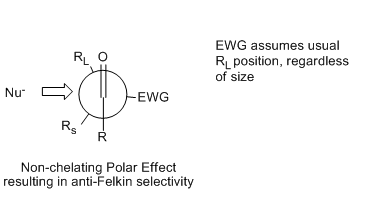

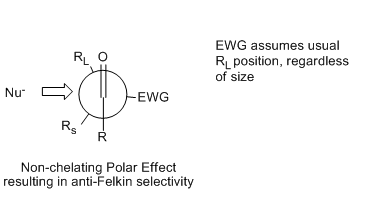

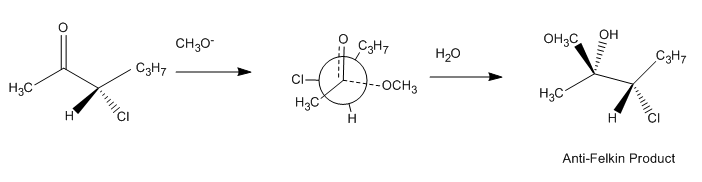

A non-chelating electron-withdrawing substituent effect can also result in anti-Felkin selectivity. If a substituent on the α-carbon is sufficiently electron withdrawing, the nucleophile

will add anti- relative to the electron withdrawing group, even if the substituent is not the largest of the 3 bonded to the α-carbon. Each model offers a slightly different explanation for this phenomenon. A polar effect was postulated by the Cornforth model and the original Felkin model, which placed the EWG substituent and incoming nucleophile

anti- to each other in order to most effectively cancel the dipole moment

of the transition structure.

This Newman projection

illustrates the Cornforth and Felkin transition state

that places the EWG anti- to the incoming nucleophile

, regardless of its steric bulk relative to RS and RL.

The improved Felkin–Anh model, as discussed above, makes a more sophisticated assessment of the polar effect by considering molecular orbital

interactions in the stabilization of the preferred transition state. A typical reaction illustrating the potential anti-Felkin selectivity of this effect, along with its proposed transition structure, is pictured below:

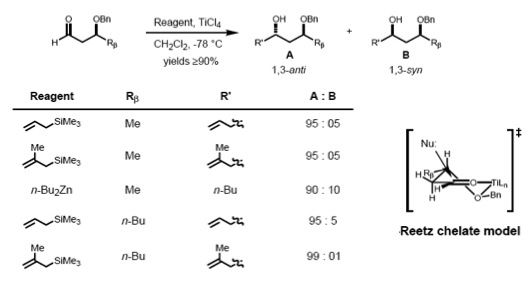

To make such chelates, the metal center must have at least two free coordination sites and the protecting ligands should form a bidentate complex with the Lewis acid.

However, in the case of the syn-substrate, the Felkin–Anh and the Evans model predict different products (non-stereoreinforcing case). It has been found that the size of the incoming nucleophile determines the type of control exerted over the stereochemistry. In the case of a large nucleophile, the interaction of the α-stereocenter with the incoming nucleophile becomes dominant; therefore, the Felkin product is major one. Smaller nucleophiles, on the other hand, result in 1,3 control determining the asymmetry.

Stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms within molecules. An important branch of stereochemistry is the study of chiral molecules....

describes the preferential formation in a chemical reaction

Chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Chemical reactions can be either spontaneous, requiring no input of energy, or non-spontaneous, typically following the input of some type of energy, such as heat, light or electricity...

of one enantiomer

Enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer is one of two stereoisomers that are mirror images of each other that are non-superposable , much as one's left and right hands are the same except for opposite orientation. It can be clearly understood if you try to place your hands one over the other without...

or diastereoisomer over the other as a result of the influence of a chiral feature present in the substrate

Substrate (chemistry)

In chemistry, a substrate is the chemical species being observed, which reacts with a reagent. This term is highly context-dependent. In particular, in biochemistry, an enzyme substrate is the material upon which an enzyme acts....

, reagent

Reagent

A reagent is a "substance or compound that is added to a system in order to bring about a chemical reaction, or added to see if a reaction occurs." Although the terms reactant and reagent are often used interchangeably, a reactant is less specifically a "substance that is consumed in the course of...

, catalyst or environment. Asymmetric induction is a key element in asymmetric synthesis.

Asymmetric induction was introduced by Emil Fischer

Emil Fischer

Emil Fischer may refer to:* Emil Fischer , German dramatic basso* Franz Joseph Emil Fischer , German chemist, worked with oil and coal* Hermann Emil Fischer , German Nobel laureate in chemistry...

based on his work on carbohydrate

Carbohydrate

A carbohydrate is an organic compound with the empirical formula ; that is, consists only of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, with a hydrogen:oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 . However, there are exceptions to this. One common example would be deoxyribose, a component of DNA, which has the empirical...

s. Several types of induction exist.

Internal asymmetric induction makes use of a chiral center bound to the reactive center through a covalent bond

Covalent bond

A covalent bond is a form of chemical bonding that is characterized by the sharing of pairs of electrons between atoms. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms when they share electrons is known as covalent bonding....

and remains so during the reaction. The starting material is often derived from chiral pool synthesis

Chiral pool synthesis

Chiral pool synthesis is a strategy that aims to improve the efficiency of chiral synthesis. It starts the organic synthesis of a complex enantiopure chemical compound from a stock of readily available enantiopure substances. Common chiral starting materials include monosaccharides and amino acids...

. In relayed asymmetric induction the chiral information is introduced in a separate step and removed again in a separate chemical reaction. Special synthons are called chiral auxiliaries

Chiral auxiliary

A chiral auxiliary is a chemical compound or unit that is temporarily incorporated into an organic synthesis so that it can be carried out asymmetrically with the selective formation of one of two enantiomers...

. In external asymmetric induction chiral information is introduced in the transition state

Transition state

The transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest energy along this reaction coordinate. At this point, assuming a perfectly irreversible reaction, colliding reactant molecules will always...

through a catalyst of chiral ligand

Chiral ligand

In chemistry a chiral ligand is a specially adapted ligand used for asymmetric synthesis. This ligand is an enantiopure organic compound which combines with a metal center by chelation to form an asymmetric catalyst. This catalyst engages in a chemical reaction and transfers its chirality to the...

. This method of asymmetric synthesis is economically most desirable.

Carbonyl 1,2 asymmetric induction

Several models exist to describe chiral induction at carbonyl carbons during nucleophilic additions. These models are based on a combination of steric and electronic considerations and are often in conflict with each other. Models have been devised by Cram (1952), Cornforth (1959), Felkin (1969) and others.Cram's rule

The Cram's rule of asymmetric induction developed by Donald J. CramDonald J. Cram

Donald James Cram was an American chemist who shared the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Jean-Marie Lehn and Charles J...

in 1952 is an early concept relating to the prediction of stereochemistry in certain acyclic

Acyclic

Acyclic can refer to:* In chemistry, a compound which is not cyclic, e.g. alkanes and acyclic aliphatic compounds* In mathematics:** A graph without a cycle, especially*** A directed acyclic graph...

systems. In full the rule is:

In certain non-catalytic reactions that diastereomer will predominate, which could be formed by the approach of the entering group from the least hindered side when the rotational conformation of the C-C bond is such that the double bond is flanked by the two least bulky groups attached to the adjacent asymmetric center.

The rule indicates that the presence of an asymmetric center in a molecule induces the formation of an asymmetric center adjacent to it based on steric hindrance.

In his 1952 publication Cram presented a large number of reactions described in the literature for which the conformation of the reaction products could be explained based on this rule and he also described an elaborate experiment (scheme 1) making his case.

The experiments involved two reactions. In experiment one 2-phenylpropionaldehyde (1, racemic

Racemic

In chemistry, a racemic mixture, or racemate , is one that has equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule. The first known racemic mixture was "racemic acid", which Louis Pasteur found to be a mixture of the two enantiomeric isomers of tartaric acid.- Nomenclature :A...

but (R)-enantiomer shown) was reacted with the Grignard reagent of bromobenzene to 1,2-diphenyl-1-propanol (2) as a mixture of diastereomer

Diastereomer

Diastereomers are stereoisomers that are not enantiomers.Diastereomerism occurs when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have different configurations at one or more of the equivalent stereocenters and are not mirror images of each other.When two diastereoisomers differ from each other at...

s, predominantly the threo isomer

Isomer

In chemistry, isomers are compounds with the same molecular formula but different structural formulas. Isomers do not necessarily share similar properties, unless they also have the same functional groups. There are many different classes of isomers, like stereoisomers, enantiomers, geometrical...

(see for explanation the Fischer projection

Fischer projection

The Fischer projection, devised by Hermann Emil Fischer in 1891, is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional organic molecule by projection. Fischer projections were originally proposed for the depiction of carbohydrates and used by chemists, particularly in organic chemistry and...

).

The preference for the formation of the threo isomer can be explained by the rule stated above by having the active nucleophile

Nucleophile

A nucleophile is a species that donates an electron-pair to an electrophile to form a chemical bond in a reaction. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by definition Lewis bases.Nucleophilic describes the...

in this reaction attacking the carbonyl group from the least hindered side (see Newman projection

Newman projection

A Newman projection, useful in alkane stereochemistry, visualizes chemical conformations of a carbon-carbon chemical bond from front to back, with the front carbon represented by a dot and the back carbon as a circle . The front carbon atom is called proximal, while the back atom is called distal...

A) when the carbonyl is positioned in a staggered

Staggered

In organic chemistry, a staggered conformation is a chemical conformation of an ethane-like moiety abcX-Ydef in which the substituents a,b,and c are at the maximum distance from d,e,and f...

formation with the methyl group and the hydrogen

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

atom, which are the two smallest substituent

Substituent

In organic chemistry and biochemistry, a substituent is an atom or group of atoms substituted in place of a hydrogen atom on the parent chain of a hydrocarbon...

s creating a minimum of steric hindrance, in a gauche orientation

Gauche (stereochemistry)

The term "gauche" refers to conformational isomers where two vicinal groups are separated by a 60° torsion angle. IUPAC defines groups as gauche if they have a "synclinal alignment of groups attached to adjacent atoms"....

and phenyl as the most bulky group in the anti conformation.

The second reaction is the organic reduction of 1,2-diphenyl-1-propanone 2 with lithium aluminium hydride

Lithium aluminium hydride

Lithium aluminium hydride, commonly abbreviated to LAH or known as LithAl, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula LiAlH4. It was discovered by Finholt, Bond and Schlesinger in 1947. This compound is used as a reducing agent in organic synthesis, especially for the reduction of esters,...

, which results in the same reaction product as above but now with preference for the erythro isomer (2a). Now a hydride

Hydride

In chemistry, a hydride is the anion of hydrogen, H−, or, more commonly, a compound in which one or more hydrogen centres have nucleophilic, reducing, or basic properties. In compounds that are regarded as hydrides, hydrogen is bonded to a more electropositive element or group...

anion (H-) is the nucleophile attacking from the least hindered side (imagine hydrogen entering from the paper plane).

In the original 1952 publication, additional evidence was obtained for the structural assignment of the reaction products by applying them to a Chugaev elimination

Chugaev elimination

The Chugaev elimination is a chemical reaction that involves the elimination of water from alcohols to produce alkenes. The intermediate is a xanthate. It is named for its discoverer, the Russian chemist Lev Aleksandrovich Chugaev....

, wherein the threo isomer reacts to the cis isomer of -α-methyl-stilbene

Stilbene

-Stilbene, is a diarylethene, i.e., a hydrocarbon consisting of a trans ethene double bond substituted with a phenyl group on both carbon atoms of the double bond. The name stilbene is derived from the Greek word stilbos, which means shining....

and the erythro isomer to the trans version.

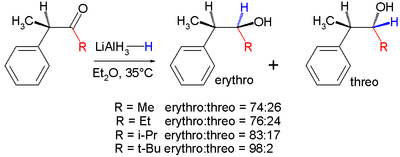

Felkin model

The Felkin model (1968) named after Hugh FelkinHugh Felkin

Hugh Felkin was a research chemist in France from 1950 to 1990 and a member of the British Royal Society for Chemistry.In 1967, he proposed a model to predict the stereochemical outcome of the addition of nucleophiles to carbonylic compounds...

also predicts the stereochemistry

Stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms within molecules. An important branch of stereochemistry is the study of chiral molecules....

of nucleophilic addition

Nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition reaction is an addition reaction where in a chemical compound a π bond is removed by the creation of two new covalent bonds by the addition of a nucleophile....

reactions to carbonyl

Carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups....

groups. Felkin argued that the Cram model suffered a major drawback: an eclipsed

Eclipsed

In chemistry an eclipsed conformation is a conformation in which two substituents X and Y on adjacent atoms A, B are in closest proximity, implying that the torsion angle X-A-B-Y is 0°. Such a conformation exists in any open chain single chemical bond connecting two sp3 hybridised atoms, and is...

conformation in the transition state

Transition state

The transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest energy along this reaction coordinate. At this point, assuming a perfectly irreversible reaction, colliding reactant molecules will always...

between the carbonyl substituent (the hydrogen atom in aldehydes) and the largest α-carbonyl substituent. He demonstrated that by increasing the steric bulk of the carbonyl substituent from methyl to ethyl

Ethyl group

In chemistry, an ethyl group is an alkyl substituent derived from ethane . It has the formula -C2H5 and is very often abbreviated -Et.Ethylation is the formation of a compound by introduction of the ethyl functional group, C2H5....

to isopropyl

Isopropyl

In organic chemistry, isopropyl is a propyl with a group attached to the secondary carbon. If viewed as a functional group an isopropyl is an organic compound with a propyl group attached at its secondary carbon.The bond is therefore on the middle carbon....

to isobutyl, the stereoselectivity

Stereoselectivity

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during the non-stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during the non-stereospecific transformation of a pre-existing one...

also increased, which is not predicted by Cram's rule:

The Felkin rules are:

- The transition stateTransition stateThe transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest energy along this reaction coordinate. At this point, assuming a perfectly irreversible reaction, colliding reactant molecules will always...

s are reactant-like. - Torsional strain (Pitzer strain) involving partial bonds (in transition states) represents a substantial fraction of the strain between fully formed bonds, even when the degree of bonding is quite low. The conformation in the TS is staggeredStaggeredIn organic chemistry, a staggered conformation is a chemical conformation of an ethane-like moiety abcX-Ydef in which the substituents a,b,and c are at the maximum distance from d,e,and f...

and not eclipsed with the substituent R skew with respect to two adjacent groups one of them the smallest in TS A.

- For comparison TS B is the Cram transition state.

- The main steric interactions involve those around R and the nucleophile but not the carbonyl oxygen atom.

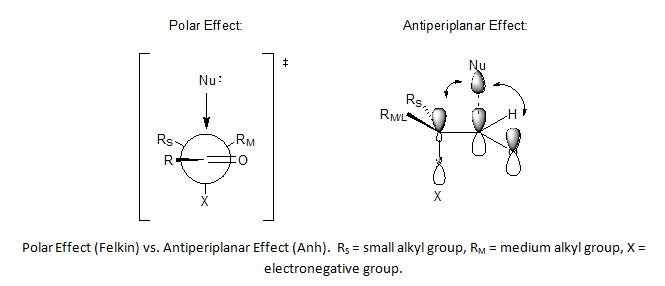

- A polar effectPolar effectThe Polar effect or electronic effect in chemistry is the effect exerted by a substituent on modifying electrostatic forces operating on a nearby reaction center...

or electronic effect stabilizes a transition state with maximum separation between the nucleophile and an electron-withdrawing group. For instance haloketoneHaloketoneA haloketone in organic chemistry is a functional group consisting of a ketone group or more general a carbonyl group with a α-halogen substituent. The general structure is RR'CCR where R is an alkyl or aryl residue and X any one of the halogens...

s do not obey Cram's rule, and, in the example above, replacing the electron-withdrawing phenyl group by a cyclohexyl group reduces stereoselectivity considerably.

Felkin-Anh model

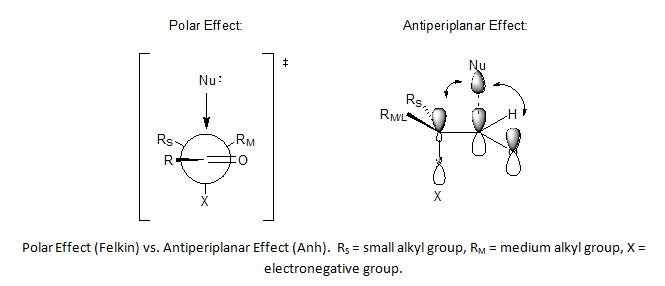

The Felkin-Anh model is an extension of the Felkin model that incorporates improvements suggested by Nguyen T. Anh and O. Eisenstein to correct for two key weaknesses in Felkin's model. The first weakness addressed was the statement by Felkin of a strong polar effect in nucleophilic addition transition states, which leads to the complete inversion of stereochemistry by SN2 reactions, without offering justifications as to why this phenomenon was observed. Anh's solution was to offer the antiperiplanar effect as a consequence of asymmetric induction being controlled by both substituent and orbital effects. In this effect, the best nucleophile acceptor σ* orbital is aligned parallel to both the π and π* orbitals of the carbonyl, which provide stabilization of the incoming anion.

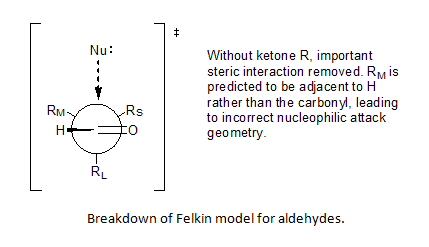

The second weakness in the Felkin Model was the assumption of substituent minimization around the carbonyl R, which cannot be applied to aldehydes.

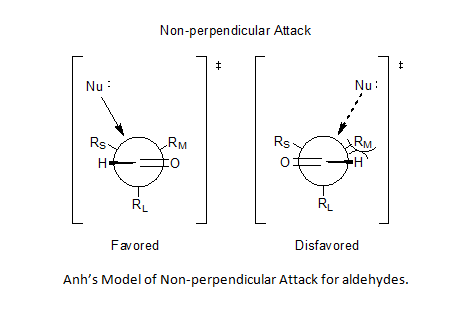

Incorporation of Bürgi–Dunitz angle ideas allowed Anh to postulate a non-perpendicular attack by the nucleophile on the carbonyl center, anywhere from 95o to 105o relative to the oxygen-carbon double bond, favoring approach closer to the smaller substituent and thereby solve the problem of predictability for aldehydes.

Anti–Felkin selectivity

Though the Cram and Felkin–Anh models differ in the conformers considered and other assumptions, they both attempt to explain the same basic phenomenon: the preferential addition of a nucleophileNucleophile

A nucleophile is a species that donates an electron-pair to an electrophile to form a chemical bond in a reaction. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by definition Lewis bases.Nucleophilic describes the...

to the most sterically favored face of a carbonyl

Carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups....

moiety. However, many examples exist of reactions that display stereoselectivity opposite of what is predicted by the basic tenets of the Cram and Felkin–Anh models. Although both of the models include attempts to explain these reversals, the products obtained are still referred to as "anti-Felkin" products. One of the most common examples of altered asymmetric induction selectivity requires an α-carbon substituted with a component with Lewis base character (i.e. O, N, S, P substituents). In this situation, if a Lewis acid

Lewis acid

]The term Lewis acid refers to a definition of acid published by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1923, specifically: An acid substance is one which can employ a lone pair from another molecule in completing the stable group of one of its own atoms. Thus, H+ is a Lewis acid, since it can accept a lone pair,...

such as Al-iPr2 or Zn2+ is introduced, a bidentate chelation

Chelation

Chelation is the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between apolydentate ligand and a single central atom....

effect can be observed. This locks the carbonyl

Carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups....

and the Lewis base substituent in an eclipsed conformation, and the nucleophile

Nucleophile

A nucleophile is a species that donates an electron-pair to an electrophile to form a chemical bond in a reaction. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by definition Lewis bases.Nucleophilic describes the...

will then attack from the side with the smallest free α-carbon substituent. If the chelating R group is identified as the largest, this will result in an "anti-Felkin" product.

This stereoselective control was recognized and discussed in the first paper establishing the Cram model, causing Cram to assert that his model requires non-chelating conditions. An example of chelation

Chelation

Chelation is the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between apolydentate ligand and a single central atom....

control of a reaction can be seen here, from a 1987 paper that was the first to directly observe such a "Cram-chelate" intermediate, vindicating the model:

Here, the methyl titanium chloride forms a Cram-chelate. The methyl group then dissociates from titanium

Titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ti and atomic number 22. It has a low density and is a strong, lustrous, corrosion-resistant transition metal with a silver color....

and attacks the carbonyl, leading to the anti-Felkin diastereomer.

A non-chelating electron-withdrawing substituent effect can also result in anti-Felkin selectivity. If a substituent on the α-carbon is sufficiently electron withdrawing, the nucleophile

Nucleophile

A nucleophile is a species that donates an electron-pair to an electrophile to form a chemical bond in a reaction. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by definition Lewis bases.Nucleophilic describes the...

will add anti- relative to the electron withdrawing group, even if the substituent is not the largest of the 3 bonded to the α-carbon. Each model offers a slightly different explanation for this phenomenon. A polar effect was postulated by the Cornforth model and the original Felkin model, which placed the EWG substituent and incoming nucleophile

Nucleophile

A nucleophile is a species that donates an electron-pair to an electrophile to form a chemical bond in a reaction. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by definition Lewis bases.Nucleophilic describes the...

anti- to each other in order to most effectively cancel the dipole moment

Bond dipole moment

The bond dipole moment uses the idea of electric dipole moment to measure the polarity of a chemical bond within a molecule. The bond dipole μ is given by:\mu = \delta \, d....

of the transition structure.

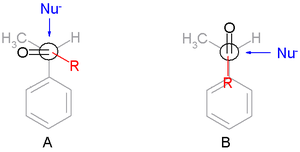

This Newman projection

Newman projection

A Newman projection, useful in alkane stereochemistry, visualizes chemical conformations of a carbon-carbon chemical bond from front to back, with the front carbon represented by a dot and the back carbon as a circle . The front carbon atom is called proximal, while the back atom is called distal...

illustrates the Cornforth and Felkin transition state

Transition state

The transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest energy along this reaction coordinate. At this point, assuming a perfectly irreversible reaction, colliding reactant molecules will always...

that places the EWG anti- to the incoming nucleophile

Nucleophile

A nucleophile is a species that donates an electron-pair to an electrophile to form a chemical bond in a reaction. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by definition Lewis bases.Nucleophilic describes the...

, regardless of its steric bulk relative to RS and RL.

The improved Felkin–Anh model, as discussed above, makes a more sophisticated assessment of the polar effect by considering molecular orbital

Molecular orbital

In chemistry, a molecular orbital is a mathematical function describing the wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of finding an electron in any specific region. The term "orbital" was first...

interactions in the stabilization of the preferred transition state. A typical reaction illustrating the potential anti-Felkin selectivity of this effect, along with its proposed transition structure, is pictured below:

Carbonyl 1,3 asymmetric induction

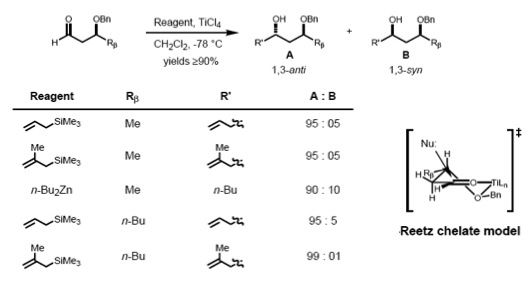

It has been observed that the stereoelectronic environment at the β-carbon of can also direct asymmetric induction. A number of predictive models have evolved over the years to define the stereoselectivity of such reactions.Chelation model

According to Reetz, the Cram-chelate model for 1,2-inductions can be extended to predict the chelated complex of a β-alkoxy aldehyde and metal. The nucleophile is seen to attack from the less sterically hindered side and anti- to the substituent Rβ, leading to the anti-adduct as the major product.

To make such chelates, the metal center must have at least two free coordination sites and the protecting ligands should form a bidentate complex with the Lewis acid.

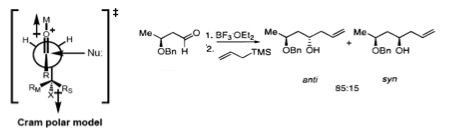

Cram–Reetz model

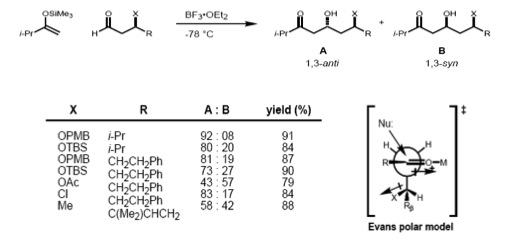

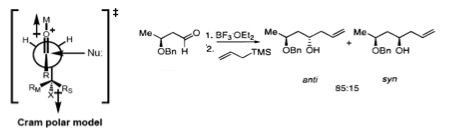

Cram and Reetz demonstrated that 1,3-stereocontrol is possible if the reaction proceeds through an acyclic transition state. The reaction of β-alkoxy aldehyde with allyltrimethylsilane showed good selectivity for the anti-1,3-diol, which was explained by the Cram polar model. The polar benzyloxy group is oriented anti to the carbonyl to minimize dipole interactions and the nucleophile attacks anti- to the bulkier (RM) of the remaining two substituents.

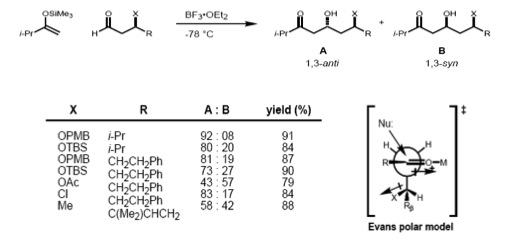

Evans model

More recently, Evans presented a different model for nonchelate 1,3-inductions. In the proposed transition state, the β-stereocenter is oriented anti- to the incoming nucleophile, as seen in the Felkin–Anh model. The polar X group at the β-stereocenter is placed anti- to the carbonyl to reduce dipole interactions, and Rβ is placed anti- to the aldehyde group to minimize the steric hindrance. Consequently, the 1,3-anti-diol would be predicted as the major product.

Carbonyl 1,2 and 1,3 asymmetric induction

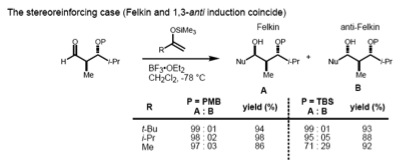

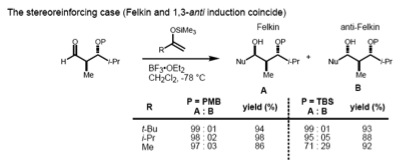

If the substrate has both an α- and β-stereocenter, the Felkin–Anh rule (1,2-induction) and the Evans model (1,3-induction) should considered at the same time. If these two stereocenters have an anti- relationship, both models predict the same diastereomer (the stereoreinforcing case).

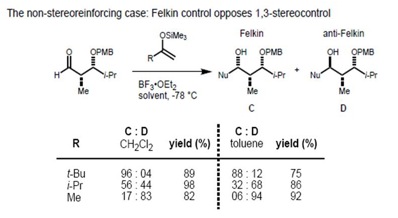

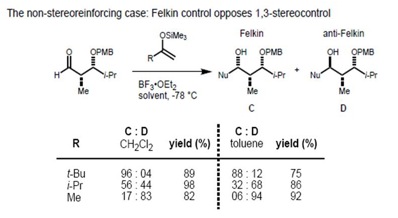

However, in the case of the syn-substrate, the Felkin–Anh and the Evans model predict different products (non-stereoreinforcing case). It has been found that the size of the incoming nucleophile determines the type of control exerted over the stereochemistry. In the case of a large nucleophile, the interaction of the α-stereocenter with the incoming nucleophile becomes dominant; therefore, the Felkin product is major one. Smaller nucleophiles, on the other hand, result in 1,3 control determining the asymmetry.

External links

- The Evolution of Models for Carbonyl Addition Evans Group Afternoon Seminar Sarah Siska February 9, 2001