Benjamin Thompson

Encyclopedia

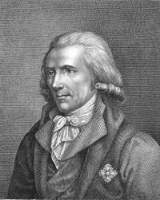

Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (in German

: ), FRS (March 26, 1753 – August 21, 1814) was an American-born British physicist

and inventor whose challenges to established physical theory were part of the 19th century revolution

in thermodynamics

. He also served as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Loyalist

forces in America during the American Revolutionary War

. After the end of the war he moved to London where his administrative talents were recognized when he was appointed a full Colonel, and in 1784 received a knighthood from King George III. A prolific designer, he also drew designs for warships. He later moved to Bavaria

and entered government service there, being appointed Bavarian Army Minister and re-organizing the army, and, in 1791, was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire

.

, on March 26, 1753; his birthplace

is preserved as a museum. He was educated mainly at the village school, although he sometimes walked to Cambridge

with the older Loammi Baldwin

to attend lectures by Professor John Winthrop

of Harvard College

. At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to John Appleton, a merchant

of nearby Salem

. Thompson excelled at his trade, and coming in contact with refined and well educated people for the first time, adopted many of their characteristics, including an interest in science

. While recuperating in Woburn in 1769 from an injury, Thompson conducted experiments concerning the nature of heat

and began to correspond with Loammi Baldwin

and others about them. Later that year, he worked for a few months for a Boston shopkeeper and then apprenticed himself briefly, and unsuccessfully, to a doctor in Woburn.

Thompson's prospects were dim in 1772 but in that year they changed abruptly. He met, charmed and married a rich and well-connected heiress named Sarah Rolfe, her father was minister and her late husband left her property at Concord, then called Rumford. They moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire

, and through his wife's influence with the governor, was appointed a major in a New Hampshire Militia

.

When the American Revolution

began, Thompson was a man of property and standing in New England, and was opposed to the rebels. He was active in recruiting loyalist

s to fight the rebel

s. This earned him the enmity of the popular party, and a mob attacked Thompson's house. He fled to the British lines, abandoning his wife, as it turned out, forever. Thompson was welcomed by the British, to whom he gave valuable information about the American forces, and became an advisor to both General Gage

and Lord George Germain

.

While working with the British armies in America, he conducted experiments concerning the force of gunpowder

, the results of which were widely acclaimed when eventually published, in 1781, in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

. Thus, when he moved to London

at the conclusion of the war, he already had a reputation as a scientist.

In 1785, he moved to Bavaria

In 1785, he moved to Bavaria

where he became an aide-de-camp

to the Prince-elector

Karl Theodor

. He spent eleven years in Bavaria, reorganizing the army and establishing workhouse

s for the poor. He also invented Rumford's Soup

, a soup for the poor, and established the cultivation of the potato

in Bavaria. He studied methods of cooking, heating, and lighting, including the relative costs and efficiencies of wax

candles, tallow

candles, and oil lamps.

He also founded the Englischer Garten in Munich

in 1789; it remains today and is known as one of the largest urban public parks in the world. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

in 1789. For his efforts, in 1791 Thompson was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, with the title of Reichsgraf von Rumford (English

: Count Rumford). He took the name "Rumford" for Rumford, New Hampshire, which was an older name for the town of Concord

, where he had been married, becoming "Count Rumford".

published his parallel discovery first.

Thompson next investigated the insulating properties of various materials

, including fur

, wool

and feather

s. He correctly appreciated that the insulating properties of these natural materials arise from the fact that they inhibit the convection

of air. He then made the somewhat reckless, and incorrect, inference that air and, in fact, all gases, were perfect non-conductor

s of heat. He further saw this as evidence of the argument from design, contending that divine providence

had arranged for fur on animals in such a way as to guarantee their comfort.

In 1797, he extended his claim about non-conductivity to liquids. The idea raised considerable objections from the scientific establishment, John Dalton

and John Leslie

making particularly forthright attacks. Instrumentation far exceeding anything available in terms of accuracy and precision would have been needed to verify Thompson's claim. Again, he seems to have been influenced by his theological beliefs and it is likely that he wished to grant water a privileged and providential status in the regulation of human life.

(1798) was not the caloric

of then-current scientific thinking but a form of motion

. Rumford had observed the frictional heat generated by boring cannon at the arsenal in Munich. Rumford immersed a cannon barrel in water and arranged for a specially blunted boring tool. He showed that the water could be boiled within roughly two and a half hours and that the supply of frictional heat was seemingly inexhaustible. Rumford confirmed that no physical change had taken place in the material of the cannon by comparing the specific heats of the material machined away and that remaining.

Rumford argued that the seemingly indefinite generation of heat was incompatible with the caloric theory. He contended that the only thing communicated to the barrel was motion.

Rumford made no attempt to further quantify the heat generated or to measure the mechanical equivalent of heat. Though this work met with a hostile reception, it was subsequently important in establishing the laws of conservation of energy

later in the 19th century.

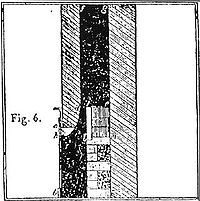

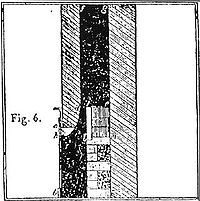

Thompson was an active and prolific inventor, developing improvements for chimneys and fireplaces and inventing the double boiler, a kitchen range, and a drip coffeepot. The Rumford fireplace

Thompson was an active and prolific inventor, developing improvements for chimneys and fireplaces and inventing the double boiler, a kitchen range, and a drip coffeepot. The Rumford fireplace

is a much more efficient way to heat a room than earlier fireplaces, and created a sensation in London when he introduced the idea of restricting the chimney opening to increase the updraught. He and his workers changed fireplaces by inserting bricks into the hearth to make the side walls angled and added a choke to the chimney to increase the speed of air going up the flue. It effectively produced a streamlined air flow, so all the smoke would go up into the chimney rather than lingering, entering the room and often choking the residents. It also had the effect of increasing the efficiency of the fire, and gave extra control of the rate of combustion of the fuel, whether wood or coal

. Many fashionable London houses were modified to his instructions, and became smoke-free. Thompson became a celebrity when news of his success became widespread.

His work was also very profitable, and much imitated when he published his analysis of the way chimneys worked. In many ways, he was similar to Benjamin Franklin

, who also invented a new kind of heating stove.

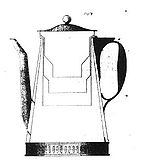

He invented a percolating coffee pot following his pioneering work with the Bavarian Army, where he improved the diet of the soldiers as well as their clothes.

The retention of heat was a recurring theme in his work, as he is also credited with the invention of thermal underwear.

, the measurement of light. He made a photometer and introduced the standard candle, the predecessor of the candela

, as a unit of luminous intensity

. His standard candle was made from the oil of a sperm whale, to rigid specifications. He also published studies of "illusory" or subjective complementary colors, induced by the shadows created by two lights, one white and one colored; these observations were cited and generalized by Michel-Eugène Chevreul as his "law of simultaneous color contrast" in 1839.

After 1799, he divided his time between France

After 1799, he divided his time between France

and England. With Sir Joseph Banks, he established the Royal Institution

of Great Britain

in 1799. The pair chose Sir Humphry Davy

as the first lecturer. The institution flourished and became world famous as a result of Davy's pioneering research. His assistant, Michael Faraday

established the Institution as a premier research laboratory, and also justly famous for its series of public lectures popularizing science. That tradition continues to the present, and the Royal Institution Christmas lectures attract large audiences through their TV broadcasts.

Thompson endowed the Rumford medal

s of the Royal Society

and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

, and endowed a professorship at Harvard University

. In 1803, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

.

In 1804, he married Marie-Anne Lavoisier

, the widow of the great French

chemist

Antoine Lavoisier

, his American wife having died since his emigration. They separated after a year, but Thompson settled in Paris

and continued his scientific work until his death on August 21, 1814. Thompson is buried in the small cemetery of Auteuil in Paris, just across from Adrien-Marie Legendre

. Upon his death, his daughter from his first marriage, Sarah Thompson

, inherited his title as Countess Rumford.

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

: ), FRS (March 26, 1753 – August 21, 1814) was an American-born British physicist

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

and inventor whose challenges to established physical theory were part of the 19th century revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

in thermodynamics

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a physical science that studies the effects on material bodies, and on radiation in regions of space, of transfer of heat and of work done on or by the bodies or radiation...

. He also served as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Loyalist

Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to the Kingdom of Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. At the time they were often called Tories, Royalists, or King's Men. They were opposed by the Patriots, those who supported the revolution...

forces in America during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. After the end of the war he moved to London where his administrative talents were recognized when he was appointed a full Colonel, and in 1784 received a knighthood from King George III. A prolific designer, he also drew designs for warships. He later moved to Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

and entered government service there, being appointed Bavarian Army Minister and re-organizing the army, and, in 1791, was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

.

Early years

Thompson was born in rural Woburn, MassachusettsWoburn, Massachusetts

Woburn is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA. The population was 38,120 at the 2010 census. Woburn is located north of Boston, Massachusetts, and just south of the intersection of I-93 and I-95.- History :...

, on March 26, 1753; his birthplace

Benjamin Thompson House

Benjamin Thompson House, also known as the Count Rumford Birthplace, located at 90 Elm Street, in the North Woburn area of Woburn, Massachusetts, is the birthplace of scientist and inventor Benjamin Thompson , who became Count Rumford of the Holy Roman Empire as well as Sir Benjamin Thompson of the...

is preserved as a museum. He was educated mainly at the village school, although he sometimes walked to Cambridge

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Greater Boston area. It was named in honor of the University of Cambridge in England, an important center of the Puritan theology embraced by the town's founders. Cambridge is home to two of the world's most prominent...

with the older Loammi Baldwin

Loammi Baldwin

Colonel Loammi Baldwin was a noted American engineer, politician, and a soldier in the American Revolutionary War....

to attend lectures by Professor John Winthrop

John Winthrop (1714-1779)

John Winthrop was the 2nd Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy in Harvard College. He was a distinguished mathematician, physicist and astronomer, born in Boston, Mass. His great-great-grandfather, also named John Winthrop, was founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony...

of Harvard College

Harvard College

Harvard College, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is one of two schools within Harvard University granting undergraduate degrees...

. At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to John Appleton, a merchant

Merchant

A merchant is a businessperson who trades in commodities that were produced by others, in order to earn a profit.Merchants can be one of two types:# A wholesale merchant operates in the chain between producer and retail merchant...

of nearby Salem

Salem, Massachusetts

Salem is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 40,407 at the 2000 census. It and Lawrence are the county seats of Essex County...

. Thompson excelled at his trade, and coming in contact with refined and well educated people for the first time, adopted many of their characteristics, including an interest in science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

. While recuperating in Woburn in 1769 from an injury, Thompson conducted experiments concerning the nature of heat

Heat

In physics and thermodynamics, heat is energy transferred from one body, region, or thermodynamic system to another due to thermal contact or thermal radiation when the systems are at different temperatures. It is often described as one of the fundamental processes of energy transfer between...

and began to correspond with Loammi Baldwin

Loammi Baldwin

Colonel Loammi Baldwin was a noted American engineer, politician, and a soldier in the American Revolutionary War....

and others about them. Later that year, he worked for a few months for a Boston shopkeeper and then apprenticed himself briefly, and unsuccessfully, to a doctor in Woburn.

Thompson's prospects were dim in 1772 but in that year they changed abruptly. He met, charmed and married a rich and well-connected heiress named Sarah Rolfe, her father was minister and her late husband left her property at Concord, then called Rumford. They moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire in the United States. It is the largest city but only the fourth-largest community in the county, with a population of 21,233 at the 2010 census...

, and through his wife's influence with the governor, was appointed a major in a New Hampshire Militia

New Hampshire Militia

The New Hampshire Militia was first organized in March 1680, by New Hampshire Colonial President John Cutt. The King of England authorized the Provincial President to give commissions to persons who shall be best qualified for regulating and discipline of the militia. President Cutt placed Major...

.

When the American Revolution

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

began, Thompson was a man of property and standing in New England, and was opposed to the rebels. He was active in recruiting loyalist

Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to the Kingdom of Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. At the time they were often called Tories, Royalists, or King's Men. They were opposed by the Patriots, those who supported the revolution...

s to fight the rebel

Patriot (American Revolution)

Patriots is a name often used to describe the colonists of the British Thirteen United Colonies who rebelled against British control during the American Revolution. It was their leading figures who, in July 1776, declared the United States of America an independent nation...

s. This earned him the enmity of the popular party, and a mob attacked Thompson's house. He fled to the British lines, abandoning his wife, as it turned out, forever. Thompson was welcomed by the British, to whom he gave valuable information about the American forces, and became an advisor to both General Gage

Thomas Gage

Thomas Gage was a British general, best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as military commander in the early days of the American War of Independence....

and Lord George Germain

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville PC , known as the Hon. George Sackville to 1720, as Lord George Sackville from 1720 to 1770, and as Lord George Germain from 1770 to 1782, was a British soldier and politician who was Secretary of State for America in Lord North's cabinet during the American...

.

While working with the British armies in America, he conducted experiments concerning the force of gunpowder

Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also known since in the late 19th century as black powder, was the first chemical explosive and the only one known until the mid 1800s. It is a mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate - with the sulfur and charcoal acting as fuels, while the saltpeter works as an oxidizer...

, the results of which were widely acclaimed when eventually published, in 1781, in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

. Thus, when he moved to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

at the conclusion of the war, he already had a reputation as a scientist.

Bavarian maturity

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

where he became an aide-de-camp

Aide-de-camp

An aide-de-camp is a personal assistant, secretary, or adjutant to a person of high rank, usually a senior military officer or a head of state...

to the Prince-elector

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

Karl Theodor

Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria

Charles Theodore, Prince-Elector, Count Palatine and Duke of Bavaria reigned as Prince-Elector and Count palatine from 1742, as Duke of Jülich and Berg from 1742 and also as Prince-Elector and Duke of Bavaria from 1777, until his death...

. He spent eleven years in Bavaria, reorganizing the army and establishing workhouse

Workhouse

In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment...

s for the poor. He also invented Rumford's Soup

Rumford's Soup

Rumford's Soup was an early effort in scientific nutrition. It was invented by Count Rumford around 1800 as a ration for the prisoners and the poor of Bavaria, where he was employed as an advisor to the Duke....

, a soup for the poor, and established the cultivation of the potato

Potato

The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum of the Solanaceae family . The word potato may refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, there are some other closely related cultivated potato species...

in Bavaria. He studied methods of cooking, heating, and lighting, including the relative costs and efficiencies of wax

Wax

thumb|right|[[Cetyl palmitate]], a typical wax ester.Wax refers to a class of chemical compounds that are plastic near ambient temperatures. Characteristically, they melt above 45 °C to give a low viscosity liquid. Waxes are insoluble in water but soluble in organic, nonpolar solvents...

candles, tallow

Tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton fat, processed from suet. It is solid at room temperature. Unlike suet, tallow can be stored for extended periods without the need for refrigeration to prevent decomposition, provided it is kept in an airtight container to prevent oxidation.In industry,...

candles, and oil lamps.

He also founded the Englischer Garten in Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

in 1789; it remains today and is known as one of the largest urban public parks in the world. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences is an independent policy research center that conducts multidisciplinary studies of complex and emerging problems. The Academy’s elected members are leaders in the academic disciplines, the arts, business, and public affairs.James Bowdoin, John Adams, and...

in 1789. For his efforts, in 1791 Thompson was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, with the title of Reichsgraf von Rumford (English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

: Count Rumford). He took the name "Rumford" for Rumford, New Hampshire, which was an older name for the town of Concord

Concord, New Hampshire

The city of Concord is the capital of the state of New Hampshire in the United States. It is also the county seat of Merrimack County. As of the 2010 census, its population was 42,695....

, where he had been married, becoming "Count Rumford".

Experiments on heat

His experiments on gunnery and explosives led to an interest in heat. He devised a method for measuring the specific heat of a solid substance but was disappointed when Johan WilckeJohan Wilcke

Johan Carl Wilcke was a Swedish physicist.Wilcke was born in Wismar, son of a clergyman who in 1739 was appointed second pastor of the German Church in Stockholm. He went to the German school in Stockholm and enrolled at the University of Uppsala in 1749...

published his parallel discovery first.

Thompson next investigated the insulating properties of various materials

Thermal insulation

Thermal insulation is the reduction of the effects of the various processes of heat transfer between objects in thermal contact or in range of radiative influence. Heat transfer is the transfer of thermal energy between objects of differing temperature...

, including fur

Fur

Fur is a synonym for hair, used more in reference to non-human animals, usually mammals; particularly those with extensives body hair coverage. The term is sometimes used to refer to the body hair of an animal as a complete coat, also known as the "pelage". Fur is also used to refer to animal...

, wool

Wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and certain other animals, including cashmere from goats, mohair from goats, qiviut from muskoxen, vicuña, alpaca, camel from animals in the camel family, and angora from rabbits....

and feather

Feather

Feathers are one of the epidermal growths that form the distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on birds and some non-avian theropod dinosaurs. They are considered the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates, and indeed a premier example of a complex evolutionary novelty. They...

s. He correctly appreciated that the insulating properties of these natural materials arise from the fact that they inhibit the convection

Convection

Convection is the movement of molecules within fluids and rheids. It cannot take place in solids, since neither bulk current flows nor significant diffusion can take place in solids....

of air. He then made the somewhat reckless, and incorrect, inference that air and, in fact, all gases, were perfect non-conductor

Heat conduction

In heat transfer, conduction is a mode of transfer of energy within and between bodies of matter, due to a temperature gradient. Conduction means collisional and diffusive transfer of kinetic energy of particles of ponderable matter . Conduction takes place in all forms of ponderable matter, viz....

s of heat. He further saw this as evidence of the argument from design, contending that divine providence

Divine providence

In Christian theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's activity in the world. " Providence" is also used as a title of God exercising His providence, and then the word are usually capitalized...

had arranged for fur on animals in such a way as to guarantee their comfort.

In 1797, he extended his claim about non-conductivity to liquids. The idea raised considerable objections from the scientific establishment, John Dalton

John Dalton

John Dalton FRS was an English chemist, meteorologist and physicist. He is best known for his pioneering work in the development of modern atomic theory, and his research into colour blindness .-Early life:John Dalton was born into a Quaker family at Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, Cumberland,...

and John Leslie

John Leslie (physicist)

Sir John Leslie was a Scottish mathematician and physicist best remembered for his research into heat.Leslie gave the first modern account of capillary action in 1802 and froze water using an air-pump in 1810, the first artificial production of ice.In 1804, he experimented with radiant heat using...

making particularly forthright attacks. Instrumentation far exceeding anything available in terms of accuracy and precision would have been needed to verify Thompson's claim. Again, he seems to have been influenced by his theological beliefs and it is likely that he wished to grant water a privileged and providential status in the regulation of human life.

Mechanical equivalent of heat

However, Rumford's most important scientific work took place in Munich, and centred on the nature of heat, which he contended in An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by FrictionAn Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction

An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction, , Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society p.102 is a scientific paper by Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford that provided a substantial challenge to established theories of heat and began the 19th century...

(1798) was not the caloric

Caloric theory

The caloric theory is an obsolete scientific theory that heat consists of a self-repellent fluid called caloric that flows from hotter bodies to colder bodies. Caloric was also thought of as a weightless gas that could pass in and out of pores in solids and liquids...

of then-current scientific thinking but a form of motion

Motion (physics)

In physics, motion is a change in position of an object with respect to time. Change in action is the result of an unbalanced force. Motion is typically described in terms of velocity, acceleration, displacement and time . An object's velocity cannot change unless it is acted upon by a force, as...

. Rumford had observed the frictional heat generated by boring cannon at the arsenal in Munich. Rumford immersed a cannon barrel in water and arranged for a specially blunted boring tool. He showed that the water could be boiled within roughly two and a half hours and that the supply of frictional heat was seemingly inexhaustible. Rumford confirmed that no physical change had taken place in the material of the cannon by comparing the specific heats of the material machined away and that remaining.

Rumford argued that the seemingly indefinite generation of heat was incompatible with the caloric theory. He contended that the only thing communicated to the barrel was motion.

Rumford made no attempt to further quantify the heat generated or to measure the mechanical equivalent of heat. Though this work met with a hostile reception, it was subsequently important in establishing the laws of conservation of energy

Conservation of energy

The nineteenth century law of conservation of energy is a law of physics. It states that the total amount of energy in an isolated system remains constant over time. The total energy is said to be conserved over time...

later in the 19th century.

Rumford's calorific and frigorific radiation

He regarded coldness to be more than just the absence of heat, but as something real and did experiments to support his theories of calorific and frigorific radiation and said the communication of heat was the net effect of caloric (hot) rays *and* frigorific (cold) rays. See note 8, "An enquiry concerning the nature of heat and the mode of its communication" Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, starting at page 112.Fireplaces and coffee pots

Rumford fireplace

The Rumford fireplace is a tall, shallow fireplace designed by Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, born 1753 in Woburn, Massachusetts, an Anglo-American physicist who was known for his investigations of heat....

is a much more efficient way to heat a room than earlier fireplaces, and created a sensation in London when he introduced the idea of restricting the chimney opening to increase the updraught. He and his workers changed fireplaces by inserting bricks into the hearth to make the side walls angled and added a choke to the chimney to increase the speed of air going up the flue. It effectively produced a streamlined air flow, so all the smoke would go up into the chimney rather than lingering, entering the room and often choking the residents. It also had the effect of increasing the efficiency of the fire, and gave extra control of the rate of combustion of the fuel, whether wood or coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

. Many fashionable London houses were modified to his instructions, and became smoke-free. Thompson became a celebrity when news of his success became widespread.

His work was also very profitable, and much imitated when he published his analysis of the way chimneys worked. In many ways, he was similar to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

, who also invented a new kind of heating stove.

He invented a percolating coffee pot following his pioneering work with the Bavarian Army, where he improved the diet of the soldiers as well as their clothes.

The retention of heat was a recurring theme in his work, as he is also credited with the invention of thermal underwear.

Light and photometry

Rumford worked in photometryPhotometry (optics)

Photometry is the science of the measurement of light, in terms of its perceived brightness to the human eye. It is distinct from radiometry, which is the science of measurement of radiant energy in terms of absolute power; rather, in photometry, the radiant power at each wavelength is weighted by...

, the measurement of light. He made a photometer and introduced the standard candle, the predecessor of the candela

Candela

The candela is the SI base unit of luminous intensity; that is, power emitted by a light source in a particular direction, weighted by the luminosity function . A common candle emits light with a luminous intensity of roughly one candela...

, as a unit of luminous intensity

Luminous intensity

In photometry, luminous intensity is a measure of the wavelength-weighted power emitted by a light source in a particular direction per unit solid angle, based on the luminosity function, a standardized model of the sensitivity of the human eye...

. His standard candle was made from the oil of a sperm whale, to rigid specifications. He also published studies of "illusory" or subjective complementary colors, induced by the shadows created by two lights, one white and one colored; these observations were cited and generalized by Michel-Eugène Chevreul as his "law of simultaneous color contrast" in 1839.

Later life

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and England. With Sir Joseph Banks, he established the Royal Institution

Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain is an organization devoted to scientific education and research, based in London.-Overview:...

of Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

in 1799. The pair chose Sir Humphry Davy

Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet FRS MRIA was a British chemist and inventor. He is probably best remembered today for his discoveries of several alkali and alkaline earth metals, as well as contributions to the discoveries of the elemental nature of chlorine and iodine...

as the first lecturer. The institution flourished and became world famous as a result of Davy's pioneering research. His assistant, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday, FRS was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the fields of electromagnetism and electrochemistry....

established the Institution as a premier research laboratory, and also justly famous for its series of public lectures popularizing science. That tradition continues to the present, and the Royal Institution Christmas lectures attract large audiences through their TV broadcasts.

Thompson endowed the Rumford medal

Rumford Medal

The Rumford Medal is awarded by the Royal Society every alternating year for "an outstandingly important recent discovery in the field of thermal or optical properties of matter made by a scientist working in Europe". First awarded in 1800, it was created after a 1796 donation of $5000 by the...

s of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences is an independent policy research center that conducts multidisciplinary studies of complex and emerging problems. The Academy’s elected members are leaders in the academic disciplines, the arts, business, and public affairs.James Bowdoin, John Adams, and...

, and endowed a professorship at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

. In 1803, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

.

In 1804, he married Marie-Anne Lavoisier

Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze

Marie-Anne Pierette Paulze , was a French chemist. She was born in the town of Montbrison, Loire, in a small province in France...

, the widow of the great French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

chemist

Chemist

A chemist is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties such as density and acidity. Chemists carefully describe the properties they study in terms of quantities, with detail on the level of molecules and their component atoms...

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

, his American wife having died since his emigration. They separated after a year, but Thompson settled in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

and continued his scientific work until his death on August 21, 1814. Thompson is buried in the small cemetery of Auteuil in Paris, just across from Adrien-Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre was a French mathematician.The Moon crater Legendre is named after him.- Life :...

. Upon his death, his daughter from his first marriage, Sarah Thompson

Sarah Thompson, Countess Rumford

Sarah Thompson, Countess Rumford, was a philanthropist. She is the first American to be known as a Countess.-Early life:...

, inherited his title as Countess Rumford.

Honours

- Colonel, King's American DragoonsKing's American DragoonsThe King's American Dragoon's was a British provincial military unit raised for service during the American Revolutionary War.Founded by Benjamin Thompson in 1781, it was initially formed from the remnants of other loyalist militia groups...

- KnightKnightA knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

ed, 1784. - Count of the Holy Roman EmpireHoly Roman EmpireThe Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

1791 - The crater RumfordRumford (crater)Rumford is a lunar impact crater that lies on the far side of the Moon. It is located to the northwest of the large crater Oppenheimer, and to the east-southeast of Orlov....

on the MoonMoonThe Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

is named after him. - Rumford baking powderBaking powderBaking powder is a dry chemical leavening agent used to increase the volume and lighten the texture of baked goods such as muffins, cakes, scones and American-style biscuits. Baking powder works by releasing carbon dioxide gas into a batter or dough through an acid-base reaction, causing bubbles in...

(patented 1859) is named after him, having been invented by a former Rumford professor at Harvard University, Eben Norton HorsfordEben Norton HorsfordEben Norton Horsford was an American scientist who is best known for his reformulation of baking powder, his interest in Viking settlements in America, and the monuments he built to Leif Erikson.-Life and work:...

(1818–1893), cofounder of the Rumford Chemical Works of East Providence RI.

See also

- Benjamin Thompson HouseBenjamin Thompson HouseBenjamin Thompson House, also known as the Count Rumford Birthplace, located at 90 Elm Street, in the North Woburn area of Woburn, Massachusetts, is the birthplace of scientist and inventor Benjamin Thompson , who became Count Rumford of the Holy Roman Empire as well as Sir Benjamin Thompson of the...

- HeatHeatIn physics and thermodynamics, heat is energy transferred from one body, region, or thermodynamic system to another due to thermal contact or thermal radiation when the systems are at different temperatures. It is often described as one of the fundamental processes of energy transfer between...

- History of thermodynamicsHistory of thermodynamicsThe history of thermodynamics is a fundamental strand in the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the history of science in general...

- Royal InstitutionRoyal InstitutionThe Royal Institution of Great Britain is an organization devoted to scientific education and research, based in London.-Overview:...

External links

- Eric Weisstein's World of Science. "Rumford, Benjamin Thompson". (1753–1814)

- Dr. Hugh C. Rowlinson "The Contribution of Count Rumford to Domestic Life in Jane Austen’s Time" An article not only detailing the Rumford fireplace, but also Rumford's life and other achievements.

- A Biography of Benjamin Thompson, Jr. Written in 1868

- Escutcheons of Science

- Count Rumford's Birth Place and Museum

- Count Rumford Fireplaces website