Christianity in the 17th century

Encyclopedia

The history of Christianity in the 17th century showed both deep conflict and new tolerance. The Enlightenment

grew to challenge Christianity as a whole, generally elevated human reason

above divine revelation

, and down-graded religious authorities such as the Papacy based on it. Major conflicts with strong religious elements arose, particularly in Central Europe with the Thirty Years' War

, and in North-West Europe with the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

. Partly out of weariness with conflict, greater religious tolerance developed. In the Protestant world there was persecution of Arminians and religious Independents

, such as early Unitarians

, Baptists and Quakers. In the Catholic world, Rome attempted to fend off Gallicanism

and Conciliarism

, views which threatened the Papacy and structure of the church.

Missionary activity in Asia and the Americas grew strongly, put down roots, and developed its institutions, though it met with strong resistance in Japan in particular; and at the same time Christian colonisation of some areas outside Europe succeeded, driven by economic as well as religious reasons. Christian traders were heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade

, which had the effect of transporting Africans into Christian communities. A land war between Christianity and Islam

continued, in the form of the campaigns of the Habsburg Empire and Ottoman Empire

in the Balkans, a turning point coming at Vienna

in 1683. The Tsardom of Russia

, where Orthodox Christianity

was the established religion, expanded eastwards into Siberia

and Central Asia

, regions of Islamic and shamanistic beliefs; and also south-west into the Ukraine

, where the Uniate Eastern Catholic Churches arose.

The century saw a very large volume of published Christian literature, particularly controversial and millennial

, but also historical and scholarly. Hagiography

became more critical with the Bollandists, and ecclesiastical history became thoroughly developed and debated, with Catholic scholars such as Baronius and Jean Mabillon

, and Protestants such as David Blondel

, laying down the lines of scholarship. Christian art of the Baroque

and music derived from church forms was striking, and influential on lay artists, using secular expression and themes. Poetry and drama often treated Biblical and religious matter, for example John Milton

's Paradise Lost

.

opposed the papal deposing power

in a series of controversial works, and the assassination of Henry IV of France

caused an intense focus on the theological doctrines concerned with tyrannicide

. Both Henry and James, in different ways, pursued a peaceful policy of religious conciliation, aimed at eventually healing the breach caused by the Reformation. While progress along these lines seemed more possible during the Twelve Years' Truce

, conflicts after 1620 changed the picture; and the situation of Western and Central Europe after the Peace of Westphalia

left a more stable but entrenched polarisation of Protestant and Catholic territorial states, with religious minorities.

The religious conflicts in Catholic France over Jansenism and Port-Royal produced the controversial work Lettres Provinciales

(1656-7) of Blaise Pascal

. In it he took aim at the prevailing climate of moral theology

, a speciality of the Jesuit order, and the attitude of the Collège de Sorbonne

. Pascal argued against the casuistry at that time deployed in "cases of conscience", particularly doctrines associated with probabilism

.

By the end of the century the Dictionnaire Historique et Critique

of Pierre Bayle

represented the current debates in the Republic of Letters

, a largely secular network of scholars and savants who commented in detail on religious matters as well as those of science. Proponents of wider religious toleration, and a sceptical line on many traditional beliefs, argued with increasing success for changes of attitude in many areas (including discrediting the False Decretals and the legend of Pope Joan

, magic

and witchcraft

, millennialism

and extremes of anti-Catholic propaganda, toleration of the Jews

in society). These developments ushered in the deism

of the 18th century, and signalled the beginning of the so-called Age of Reason

. They were countered by the continuing strength of the Counter-Reformation

and evangelical movements such as Pietism

.

. Contentious matters gave rise to a substantial polemical literature, written both in Latin to appeal to international opinion among the educated, and in vernacular languages. In a climate where opinion was thought open to argument, the production of polemical literature was part of the role of prelate

s and other prominent churchmen, academics (in universities) and seminarians (in religious colleges); and institutions such as Chelsea College

in London and Arras College

in Paris were set up expressly to favour such writing.

The major debates between Protestants and Catholics proving inconclusive, and theological issues within Protestantism being divisive, there was also a return to the eirenicism of Erasmus: the search for religious peace. David Pareus

was a leading Reformed theologian who favoured an approach based on reconciliation of views. Other leading figures such as Marco Antonio de Dominis

, Hugo Grotius

and John Dury

worked in this direction.

in England was Edward Wightman

in 1612. The legislation relating to this penalty was in fact only changed in 1677, after which those convicted on a heresy charge would suffer at most excommunication

. Accusations of heresy, whether the revival of Late Antique debates such as those over Pelagianism

and Arianism

, or more recent views such as Socinianism

in theology and Copernicanism in natural philosophy

, continued to play an important part in intellectual life.

At the same time as the judicial pursuit of heresy became less severe, interest in demonology

was intense in many European countries. The sceptical arguments against the existence of witchcraft

and demonic possession

were still contested into the 1680s by theologians. The Gangraena

of Thomas Edwards

used a framework equating heresy and possession to draw attention to the variety of radical Protestant views current in the 1640s.

In 1610, Galileo

In 1610, Galileo

published his Sidereus Nuncius

, describing observations that he had made with the new telescope

. These and other discoveries exposed difficulties with the understanding of the heavens current since antiquity, and raised interest in teachings such as the heliocentric

theory of Copernicus

.

In reaction, scholars such as Cosimo Boscaglia

maintained that the motion of the Earth and immobility of the Sun

were heretical

, as they contradicted some accounts given in the Bible

as understood at that time. Galileo's part in the controversies over theology

, astronomy

and philosophy

culminated in his trial and sentencing in 1633, on a grave suspicion of heresy.

The Galileo affair

—the process by which Galileo came into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church

over his support of Copernican astronomy

—has often been considered a defining moment in the history of the relationship between religion and science

.

, Switzerland and Poland also controlled by Protestants. Heavy fighting, in some cases a continuation of the religious conflicts of the previous centuries, was seen, particularly in the Low Countries and the Electoral Palatinate (which saw the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War

). In Ireland there was a concerted attempt to create "plantations" of Protestant settlers in what was a predominantly Catholic country, and fighting with a religious dimension was serious in the 1640s and 1680s. In France the settlement proposed by the Edict of Nantes

was whittled away, to the disadvantage of the Huguenot

population, and the Edit was revoked in 1685.

Protestant Europe was largely divided into Lutheran and Reformed (Calvinist) areas, with the Church of England

maintaining a separate position. Efforts to unify Lutherans and Calvinists had little success; and the ecumenical ambition to overcome the schism of the Protestant Reformation

remained almost entirely theoretical. The Church of England under William Laud

made serious approaches to figures in the Orthodox Church, looking for common ground.

Within Calvinism an important split occurred with the rise of Arminianism

; the Synod of Dort

of 1618-9 was a national gathering but with international repercussions, as the teaching of Arminius was firmly rejected at a meeting to which Protestant theologians from outside the Netherlands were invited. The Westminster Assembly

of the 1640s was another major council dealing with Reformed theology, and some of its works continue to be important to Protestant denominations.

movement, a description admitted to be unsatisfactory by many historians. In its early stages the Puritan movement (late 16th-17th centuries) stood for reform in the Church of England

, within the Calvinist tradition, aiming to make the Church of England resemble more closely the Protestant churches of Europe, especially Geneva

. The Puritans refused to endorse completely all of the ritual directions and formulas of the Book of Common Prayer

; the imposition of its liturgical order by legal force and inspection sharpened Puritanism into a definite opposition movement.

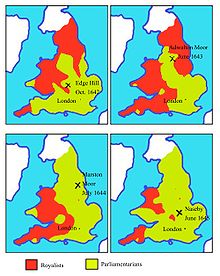

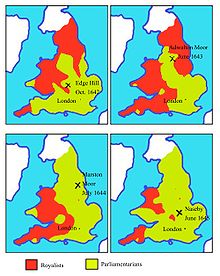

The English Civil War (1641–1651) was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians

and Royalists

. The first

(1642–46) and second

(1648–49) civil war

s pitted the supporters of King Charles I

against the supporters of the Long Parliament

, while the third war

(1649–51) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II

and supporters of the Rump Parliament

. The Civil War ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester

on 3 September 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son, Charles II, and replacement of English monarchy with first, the Commonwealth of England

(1649–53), and then with a Protectorate

(1653–59), under Oliver Cromwell

's personal rule. In Ireland military victory for the Parliamentarian forces established the Protestant Ascendancy

.

After coming to political power as a result of the First English Civil War

After coming to political power as a result of the First English Civil War

, the Puritan clergy had an opportunity to set up a national church along Presbyterian lines; for reasons that were also largely political, they failed to do so effectively. After the English Restoration

of 1660 the Church of England was purged within a few years of its Puritan elements. The successors of the Puritans, in terms of their belies, are referred to as Dissenters and Nonconformists, and included those who formed various Reformed denominations

.

, was led by a group of Puritan separatists based in the Netherlands ("the pilgrims

"). Establishing a colony at Plymouth in 1620, they received a charter from the King of England. This successful, though initially quite difficult, colony marked the beginning of the Protestant presence in America (the earlier French, Spanish and Portuguese settlements were Catholic). Unlike the Spanish or French, the English colonists made little initial effort to evangelise the native peoples.

and Gregory XV ruled in 1617 and 1622 to be inadmissible to state, that Mary was conceived non-immaculate. Alexander VII declared in 1661, that the soul of Mary was free from original sin

. Pope Clement XI

ordered the feast of the Immaculata for the whole Church in 1708. The feast of the Rosary

was introduced in 1716, the feast of the Seven Sorrows in 1727. The Angelus

prayer was strongly supported by Pope Benedict XIII

in 1724 and by Pope Benedict XIV

in 1742. Popular Marian piety was even more colourful and varied than ever before: Numerous Marian pilgrimage

s, Marian Salve devotion

s, new Marian litanies

, Marian theatre plays, Marian hymn

s, Marian procession

s. Marian fraternities

, today mostly defunct, had millions of members.

viewed the increasing Turkish attacks against Europe, which were supported by France, as the major threat for the Church. He built a Polish-Austrian coalition for the Turkish defeat at Vienna in 1683. Scholars have called him a saintly pope because he reformed abuses by the Church, including simony

, nepotism

and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a papal debt of 50,000,000 scudi

. By eliminating certain honorary posts and introducing new fiscal policies, Innocent XI was able to regain control of the church's finances. In France, the Church battled Jansenism

and Gallicanism

, which supported Councilarism, and rejected papal primacy, demanding special concessions for the Church in France.

King Louis XIV of France issued the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, ending a century of religious toleration. France forced Catholic theologians to support conciliarism

and deny Papal infallibility

. The king threatened Pope Innocent XI

with a Catholic Ecumenical Council and a military take-over of the Papal state. The absolute

French State used Gallicanism to gain control of virtually all major Church appointments as well as many of the Church's properties.

and Spanish Empire

, with a significant role played by the Roman Catholic Church

, led to a Christianization of the indigenous populations of the Americas such as the Aztec

s and Incas. Later waves of colonial expansion such as the struggle for India, by the Dutch

, England, France, Germany and Russia led to Christianization of other populations, such as groups of American Indians

and Filipinos

.

, the Roman Catholic Church

established a number of Missions

in the Americas and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the indigenous peoples

. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier

as well as other Jesuits

, Augustinians

, Franciscans and Dominicans

were moving into Asia and the Far East. The Portuguese sent missions into Africa. The most significant failure of Roman missionary work was in Ethiopia

, where following increasing civil war in response to Emperor Susenyos's

conversion to Catholicism, his son and successor Fasilides

expelled archbishop Afonso Mendes and his Jesuit brethren in 1633, then in 1665 ordered the remaining religious writings of the Catholics burnt. On the other hand, other missions (notably Matteo Ricci

's Jesuit mission to China) were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism

.

The first Catholic Church was built in Beijing

in 1650. The emperor granted freedom of religion to Catholics. Ricci had modified the Catholic faith to Chinese thinking, permitting among other things the veneration of the dead. The Vatican disagreed and forbade any adaptation in the so-called Chinese Rites controversy

in 1692 and 1742.

in the East, 1453, led to a significant shift of gravity to the rising state of Russia, the "Third Rome". The Renaissance would also stimulate a program of reforms by patriarchs of prayer books. A movement called the "Old believers

" consequently resulted and influenced Russian Orthodox theology in the direction of conservatism

and Erastianism.

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

grew to challenge Christianity as a whole, generally elevated human reason

Reason

Reason is a term that refers to the capacity human beings have to make sense of things, to establish and verify facts, and to change or justify practices, institutions, and beliefs. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, language, ...

above divine revelation

Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing, through active or passive communication with a supernatural or a divine entity...

, and down-graded religious authorities such as the Papacy based on it. Major conflicts with strong religious elements arose, particularly in Central Europe with the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

, and in North-West Europe with the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

. Partly out of weariness with conflict, greater religious tolerance developed. In the Protestant world there was persecution of Arminians and religious Independents

Independent (religion)

In English church history, Independents advocated local congregational control of religious and church matters, without any wider geographical hierarchy, either ecclesiastical or political...

, such as early Unitarians

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

, Baptists and Quakers. In the Catholic world, Rome attempted to fend off Gallicanism

Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarchs' authority or the State's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope's...

and Conciliarism

Conciliarism

Conciliarism, or the conciliar movement, was a reform movement in the 14th, 15th and 16th century Roman Catholic Church which held that final authority in spiritual matters resided with the Roman Church as a corporation of Christians, embodied by a general church council, not with the pope...

, views which threatened the Papacy and structure of the church.

Missionary activity in Asia and the Americas grew strongly, put down roots, and developed its institutions, though it met with strong resistance in Japan in particular; and at the same time Christian colonisation of some areas outside Europe succeeded, driven by economic as well as religious reasons. Christian traders were heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, also known as the trans-atlantic slave trade, refers to the trade in slaves that took place across the Atlantic ocean from the sixteenth through to the nineteenth centuries...

, which had the effect of transporting Africans into Christian communities. A land war between Christianity and Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

continued, in the form of the campaigns of the Habsburg Empire and Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

in the Balkans, a turning point coming at Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

in 1683. The Tsardom of Russia

Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia was the name of the centralized Russian state from Ivan IV's assumption of the title of Tsar in 1547 till Peter the Great's foundation of the Russian Empire in 1721.From 1550 to 1700, Russia grew 35,000 km2 a year...

, where Orthodox Christianity

Orthodox Christianity

The term Orthodox Christianity may refer to:* the Eastern Orthodox Church and its various geographical subdivisions...

was the established religion, expanded eastwards into Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

and Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

, regions of Islamic and shamanistic beliefs; and also south-west into the Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

, where the Uniate Eastern Catholic Churches arose.

The century saw a very large volume of published Christian literature, particularly controversial and millennial

Millennialism

Millennialism , or chiliasm in Greek, is a belief held by some Christian denominations that there will be a Golden Age or Paradise on Earth in which "Christ will reign" for 1000 years prior to the final judgment and future eternal state...

, but also historical and scholarly. Hagiography

Hagiography

Hagiography is the study of saints.From the Greek and , it refers literally to writings on the subject of such holy people, and specifically to the biographies of saints and ecclesiastical leaders. The term hagiology, the study of hagiography, is also current in English, though less common...

became more critical with the Bollandists, and ecclesiastical history became thoroughly developed and debated, with Catholic scholars such as Baronius and Jean Mabillon

Jean Mabillon

Jean Mabillon was a French Benedictine monk and scholar, considered the founder of palaeography and diplomatics.-Early career:...

, and Protestants such as David Blondel

David Blondel

David Blondel was a French Protestant clergyman, historian and classical scholar.-Life:He was born at Châlons-en-Champagne. Ordained in 1614, he had positions as parish priest at Houdan and Roucy. After 1644, he was relieved of duties, and supported free to study full time.In 1650 he succeeded GJ...

, laying down the lines of scholarship. Christian art of the Baroque

Baroque

The Baroque is a period and the style that used exaggerated motion and clear, easily interpreted detail to produce drama, tension, exuberance, and grandeur in sculpture, painting, literature, dance, and music...

and music derived from church forms was striking, and influential on lay artists, using secular expression and themes. Poetry and drama often treated Biblical and religious matter, for example John Milton

John Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

's Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton. It was originally published in 1667 in ten books, with a total of over ten thousand individual lines of verse...

.

Changing attitudes, Protestant and Catholic

At the beginning of the century James I of EnglandJames I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

opposed the papal deposing power

Papal deposing power

The papal deposing power was the most powerful tool of the political authority claimed by and on behalf of the Roman Pontiff, in medieval and early modern thought, amounting to the assertion of the Pope's power to declare a Christian monarch heretical and powerless to rule.Pope Gregory VII's...

in a series of controversial works, and the assassination of Henry IV of France

Henry IV of France

Henry IV , Henri-Quatre, was King of France from 1589 to 1610 and King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France....

caused an intense focus on the theological doctrines concerned with tyrannicide

Tyrannicide

Tyrannicide literally means the killing of a tyrant, or one who has committed the act. Typically, the term is taken to mean the killing or assassination of tyrants for the common good. The term "tyrannicide" does not apply to tyrants killed in battle or killed by an enemy in an armed conflict...

. Both Henry and James, in different ways, pursued a peaceful policy of religious conciliation, aimed at eventually healing the breach caused by the Reformation. While progress along these lines seemed more possible during the Twelve Years' Truce

Twelve Years' Truce

The Twelve Years' Truce was the name given to the cessation of hostilities between the Habsburg rulers of Spain and the Southern Netherlands and the Dutch Republic as agreed in Antwerp on 9 April 1609. It was a watershed in the Eighty Years' War, marking the point from which the independence of the...

, conflicts after 1620 changed the picture; and the situation of Western and Central Europe after the Peace of Westphalia

Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia was a series of peace treaties signed between May and October of 1648 in Osnabrück and Münster. These treaties ended the Thirty Years' War in the Holy Roman Empire, and the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Dutch Republic, with Spain formally recognizing the...

left a more stable but entrenched polarisation of Protestant and Catholic territorial states, with religious minorities.

The religious conflicts in Catholic France over Jansenism and Port-Royal produced the controversial work Lettres Provinciales

Lettres provinciales

The Lettres provinciales are a series of eighteen letters written by French philosopher and theologian Blaise Pascal under the pseudonym Louis de Montalte...

(1656-7) of Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal , was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, writer and Catholic philosopher. He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen...

. In it he took aim at the prevailing climate of moral theology

Moral theology

Moral theology is a systematic theological treatment of Christian ethics. It is usually taught on Divinity faculties as a part of the basic curriculum.- External links :*...

, a speciality of the Jesuit order, and the attitude of the Collège de Sorbonne

Collège de Sorbonne

The Collège de Sorbonne was a theological college of the University of Paris, founded in 1257 by Robert de Sorbon, after whom it is named. With the rest of the Paris colleges, it was suppressed during the French Revolution. It was restored in 1808 but finally closed in 1882. The name Sorbonne...

. Pascal argued against the casuistry at that time deployed in "cases of conscience", particularly doctrines associated with probabilism

Probabilism

In theology and philosophy, probabilism refers to an ancient Greek doctrine of academic skepticism. It holds that in the absence of certainty, probability is the best criterion...

.

By the end of the century the Dictionnaire Historique et Critique

Dictionnaire Historique et Critique

The Dictionnaire Historique et Critique is a biographical dictionary written by Pierre Bayle , a Huguenot who lived and published in Holland after fleeing his native France due to religious persecution. The dictionary was first published in 1697, and enlarged in the second edition of 1702...

of Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle was a French philosopher and writer best known for his seminal work the Historical and Critical Dictionary, published beginning in 1695....

represented the current debates in the Republic of Letters

Republic of Letters

Republic of Letters is most commonly used to define intellectual communities in the late 17th and 18th century in Europe and America. It especially brought together the intellectuals of Age of Enlightenment, or "philosophes" as they were called in France...

, a largely secular network of scholars and savants who commented in detail on religious matters as well as those of science. Proponents of wider religious toleration, and a sceptical line on many traditional beliefs, argued with increasing success for changes of attitude in many areas (including discrediting the False Decretals and the legend of Pope Joan

Pope Joan

Pope Joan is a legendary female Pope who, it is purported, reigned for a few years some time in the Middle Ages. The story first appeared in the writings of 13th-century chroniclers, and subsequently spread through Europe...

, magic

Magic (paranormal)

Magic is the claimed art of manipulating aspects of reality either by supernatural means or through knowledge of occult laws unknown to science. It is in contrast to science, in that science does not accept anything not subject to either direct or indirect observation, and subject to logical...

and witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

, millennialism

Millennialism

Millennialism , or chiliasm in Greek, is a belief held by some Christian denominations that there will be a Golden Age or Paradise on Earth in which "Christ will reign" for 1000 years prior to the final judgment and future eternal state...

and extremes of anti-Catholic propaganda, toleration of the Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

in society). These developments ushered in the deism

Deism

Deism in religious philosophy is the belief that reason and observation of the natural world, without the need for organized religion, can determine that the universe is the product of an all-powerful creator. According to deists, the creator does not intervene in human affairs or suspend the...

of the 18th century, and signalled the beginning of the so-called Age of Reason

Age of reason

Age of reason may refer to:* 17th-century philosophy, as a successor of the Renaissance and a predecessor to the Age of Enlightenment* Age of Enlightenment in its long form of 1600-1800* The Age of Reason, a book by Thomas Paine...

. They were countered by the continuing strength of the Counter-Reformation

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation was the period of Catholic revival beginning with the Council of Trent and ending at the close of the Thirty Years' War, 1648 as a response to the Protestant Reformation.The Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive effort, composed of four major elements:#Ecclesiastical or...

and evangelical movements such as Pietism

Pietism

Pietism was a movement within Lutheranism, lasting from the late 17th century to the mid-18th century and later. It proved to be very influential throughout Protestantism and Anabaptism, inspiring not only Anglican priest John Wesley to begin the Methodist movement, but also Alexander Mack to...

.

Polemicism and eirenicism

The 17th century inherited the divisive doctrinal and political arguments within Christian thinking, set off by the Protestant Reformation, and given shape on the Catholic side by the Council of TrentCouncil of Trent

The Council of Trent was the 16th-century Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church. It is considered to be one of the Church's most important councils. It convened in Trent between December 13, 1545, and December 4, 1563 in twenty-five sessions for three periods...

. Contentious matters gave rise to a substantial polemical literature, written both in Latin to appeal to international opinion among the educated, and in vernacular languages. In a climate where opinion was thought open to argument, the production of polemical literature was part of the role of prelate

Prelate

A prelate is a high-ranking member of the clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin prælatus, the past participle of præferre, which means "carry before", "be set above or over" or "prefer"; hence, a prelate is one set over others.-Related...

s and other prominent churchmen, academics (in universities) and seminarians (in religious colleges); and institutions such as Chelsea College

Chelsea College (17th century)

Chelsea College was a polemical college founded in London in 1609. This establishment was intended to centralize controversial writing against Catholicism, and was the idea of Matthew Sutcliffe, Dean of Exeter, who was the first Provost...

in London and Arras College

Arras College

Arras College was a Catholic foundation in Paris, a house of higher studies associated with the University of Paris, set up in 1611. It was intended for English priests, and had a function as a House of Writers, or apologetical college...

in Paris were set up expressly to favour such writing.

The major debates between Protestants and Catholics proving inconclusive, and theological issues within Protestantism being divisive, there was also a return to the eirenicism of Erasmus: the search for religious peace. David Pareus

David Pareus

David Pareus was a German Reformed Protestant theologian and reformer.-Life:He was born at Frankenstein December 30, 1548. He was apprenticed to an apothecary and again to a shoemaker...

was a leading Reformed theologian who favoured an approach based on reconciliation of views. Other leading figures such as Marco Antonio de Dominis

Marco Antonio de Dominis

Marco Antonio Dominis was a Dalmatian ecclesiastic, apostate, and man of science.-Early life:He was born on the island of Rab, Croatia, off the coast of Dalmatia...

, Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius , also known as Huig de Groot, Hugo Grocio or Hugo de Groot, was a jurist in the Dutch Republic. With Francisco de Vitoria and Alberico Gentili he laid the foundations for international law, based on natural law...

and John Dury

John Dury

John Dury was a Scottish Calvinist minister and a significant intellectual of the English Civil War period. He made efforts to re-unite the Calvinist and Lutheran wings of Protestantism, hoping to succeed when he moved to Kassel in 1661, but he did not accomplish this...

worked in this direction.

Heresy and demonology

The last person to be executed by fire for heresyHeresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

in England was Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman was an English radical Anabaptist, executed at Lichfield for his activities promoting himself as the divine Paraclete and Savior of the world...

in 1612. The legislation relating to this penalty was in fact only changed in 1677, after which those convicted on a heresy charge would suffer at most excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

. Accusations of heresy, whether the revival of Late Antique debates such as those over Pelagianism

Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a theological theory named after Pelagius , although he denied, at least at some point in his life, many of the doctrines associated with his name. It is the belief that original sin did not taint human nature and that mortal will is still capable of choosing good or evil without...

and Arianism

Arianism

Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius , a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of the entities of the Trinity and the precise nature of the Son of God as being a subordinate entity to God the Father...

, or more recent views such as Socinianism

Socinianism

Socinianism is a system of Christian doctrine named for Fausto Sozzini , which was developed among the Polish Brethren in the Minor Reformed Church of Poland during the 15th and 16th centuries and embraced also by the Unitarian Church of Transylvania during the same period...

in theology and Copernicanism in natural philosophy

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

, continued to play an important part in intellectual life.

At the same time as the judicial pursuit of heresy became less severe, interest in demonology

Demonology

Demonology is the systematic study of demons or beliefs about demons. It is the branch of theology relating to superhuman beings who are not gods. It deals both with benevolent beings that have no circle of worshippers or so limited a circle as to be below the rank of gods, and with malevolent...

was intense in many European countries. The sceptical arguments against the existence of witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

and demonic possession

Demonic possession

Demonic possession is held by many belief systems to be the control of an individual by a malevolent supernatural being. Descriptions of demonic possessions often include erased memories or personalities, convulsions, “fits” and fainting as if one were dying...

were still contested into the 1680s by theologians. The Gangraena

Gangraena

Gangraena is a book by Thomas Edwards, published in 1646. A notorious work of "heresiography", i.e. the description in detail of heresy, it appeared the year after Ephraim Pagitt's Heresiography. These two books attempted to catalogue the fissiparous Protestant congregations of the time, in England...

of Thomas Edwards

Thomas Edwards (Heresiographer)

Thomas Edwards was an English Puritan clergyman. He was a very influential preacher in London of the 1640s, and also one of the most ferocious polemical writers of the time, arguing from a conservative Presbyterian point of view against the Independents.-Life:He graduated M.A. from Queens'...

used a framework equating heresy and possession to draw attention to the variety of radical Protestant views current in the 1640s.

Trial of Galileo

Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei , was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations and support for Copernicanism...

published his Sidereus Nuncius

Sidereus Nuncius

Sidereus Nuncius is a short treatise published in New Latin by Galileo Galilei in March 1610. It was the first scientific treatise based on observations made through a telescope...

, describing observations that he had made with the new telescope

Telescope

A telescope is an instrument that aids in the observation of remote objects by collecting electromagnetic radiation . The first known practical telescopes were invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 1600s , using glass lenses...

. These and other discoveries exposed difficulties with the understanding of the heavens current since antiquity, and raised interest in teachings such as the heliocentric

Heliocentrism

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a stationary Sun at the center of the universe. The word comes from the Greek . Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center...

theory of Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance astronomer and the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe....

.

In reaction, scholars such as Cosimo Boscaglia

Cosimo Boscaglia

Cosimo Boscaglia was a professor of philosophy at the University of Pisa in Italy. He is the first person known to have accused Galileo of possible heresy for defending the heliocentric system of Copernicus, in 1613.-References:...

maintained that the motion of the Earth and immobility of the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

were heretical

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

, as they contradicted some accounts given in the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

as understood at that time. Galileo's part in the controversies over theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

, astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

and philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

culminated in his trial and sentencing in 1633, on a grave suspicion of heresy.

The Galileo affair

Galileo affair

The Galileo affair was a sequence of events, beginning around 1610, during which Galileo Galilei came into conflict with the Aristotelian scientific view of the universe , over his support of Copernican astronomy....

—the process by which Galileo came into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

over his support of Copernican astronomy

Heliocentrism

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a stationary Sun at the center of the universe. The word comes from the Greek . Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center...

—has often been considered a defining moment in the history of the relationship between religion and science

Relationship between religion and science

The relationship between religion and science has been a focus of the demarcation problem. Somewhat related is the claim that science and religion may pursue knowledge using different methodologies. Whereas the scientific method basically relies on reason and empiricism, religion also seeks to...

.

Protestantism

The Protestant lands at the beginning of the 17th century were concentrated in Northern Europe, with territories in Germany and Scandinavia, England and Scotland under Protestant rule, and areas of France, the Low CountriesLow Countries

The Low Countries are the historical lands around the low-lying delta of the Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse rivers, including the modern countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of northern France and western Germany....

, Switzerland and Poland also controlled by Protestants. Heavy fighting, in some cases a continuation of the religious conflicts of the previous centuries, was seen, particularly in the Low Countries and the Electoral Palatinate (which saw the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

). In Ireland there was a concerted attempt to create "plantations" of Protestant settlers in what was a predominantly Catholic country, and fighting with a religious dimension was serious in the 1640s and 1680s. In France the settlement proposed by the Edict of Nantes

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes, issued on 13 April 1598, by Henry IV of France, granted the Calvinist Protestants of France substantial rights in a nation still considered essentially Catholic. In the Edict, Henry aimed primarily to promote civil unity...

was whittled away, to the disadvantage of the Huguenot

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

population, and the Edit was revoked in 1685.

Protestant Europe was largely divided into Lutheran and Reformed (Calvinist) areas, with the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

maintaining a separate position. Efforts to unify Lutherans and Calvinists had little success; and the ecumenical ambition to overcome the schism of the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

remained almost entirely theoretical. The Church of England under William Laud

William Laud

William Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633 to 1645. One of the High Church Caroline divines, he opposed radical forms of Puritanism...

made serious approaches to figures in the Orthodox Church, looking for common ground.

Within Calvinism an important split occurred with the rise of Arminianism

Arminianism

Arminianism is a school of soteriological thought within Protestant Christianity based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius and his historic followers, the Remonstrants...

; the Synod of Dort

Synod of Dort

The Synod of Dort was a National Synod held in Dordrecht in 1618-1619, by the Dutch Reformed Church, to settle a divisive controversy initiated by the rise of Arminianism. The first meeting was on November 13, 1618, and the final meeting, the 154th, was on May 9, 1619...

of 1618-9 was a national gathering but with international repercussions, as the teaching of Arminius was firmly rejected at a meeting to which Protestant theologians from outside the Netherlands were invited. The Westminster Assembly

Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was appointed by the Long Parliament to restructure the Church of England. It also included representatives of religious leaders from Scotland...

of the 1640s was another major council dealing with Reformed theology, and some of its works continue to be important to Protestant denominations.

Puritan movement and English Civil War

In the 1640s England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland underwent religious strife comparable to that which its neighbours had suffered some generations before. The rancour associated with these wars is partly attributed to the nature of the PuritanPuritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

movement, a description admitted to be unsatisfactory by many historians. In its early stages the Puritan movement (late 16th-17th centuries) stood for reform in the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, within the Calvinist tradition, aiming to make the Church of England resemble more closely the Protestant churches of Europe, especially Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

. The Puritans refused to endorse completely all of the ritual directions and formulas of the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

; the imposition of its liturgical order by legal force and inspection sharpened Puritanism into a definite opposition movement.

The English Civil War (1641–1651) was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

and Royalists

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

. The first

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

(1642–46) and second

Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War was the second of three wars known as the English Civil War which refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1652 and also include the First English Civil War and the...

(1648–49) civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

s pitted the supporters of King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

against the supporters of the Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

, while the third war

Third English Civil War

The Third English Civil War was the last of the English Civil Wars , a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists....

(1649–51) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

and supporters of the Rump Parliament

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

. The Civil War ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester

Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 at Worcester, England and was the final battle of the English Civil War. Oliver Cromwell and the Parliamentarians defeated the Royalist, predominantly Scottish, forces of King Charles II...

on 3 September 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son, Charles II, and replacement of English monarchy with first, the Commonwealth of England

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the republic which ruled first England, and then Ireland and Scotland from 1649 to 1660. Between 1653–1659 it was known as the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland...

(1649–53), and then with a Protectorate

The Protectorate

In British history, the Protectorate was the period 1653–1659 during which the Commonwealth of England was governed by a Lord Protector.-Background:...

(1653–59), under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

's personal rule. In Ireland military victory for the Parliamentarian forces established the Protestant Ascendancy

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

.

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

, the Puritan clergy had an opportunity to set up a national church along Presbyterian lines; for reasons that were also largely political, they failed to do so effectively. After the English Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

of 1660 the Church of England was purged within a few years of its Puritan elements. The successors of the Puritans, in terms of their belies, are referred to as Dissenters and Nonconformists, and included those who formed various Reformed denominations

Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is an identifiable religious body under a common name, structure, and doctrine within Christianity. In the Orthodox tradition, Churches are divided often along ethnic and linguistic lines, into separate churches and traditions. Technically, divisions between one group and...

.

Puritan emigration

Emigration to North America of Protestants, in what became New EnglandNew England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

, was led by a group of Puritan separatists based in the Netherlands ("the pilgrims

Pilgrims

Pilgrims , or Pilgrim Fathers , is a name commonly applied to early settlers of the Plymouth Colony in present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, United States...

"). Establishing a colony at Plymouth in 1620, they received a charter from the King of England. This successful, though initially quite difficult, colony marked the beginning of the Protestant presence in America (the earlier French, Spanish and Portuguese settlements were Catholic). Unlike the Spanish or French, the English colonists made little initial effort to evangelise the native peoples.

Devotions to Mary

Pope Paul VPope Paul V

-Theology:Paul met with Galileo Galilei in 1616 after Cardinal Bellarmine had, on his orders, warned Galileo not to hold or defend the heliocentric ideas of Copernicus. Whether there was also an order not to teach those ideas in any way has been a matter for controversy...

and Gregory XV ruled in 1617 and 1622 to be inadmissible to state, that Mary was conceived non-immaculate. Alexander VII declared in 1661, that the soul of Mary was free from original sin

Original sin

Original sin is, according to a Christian theological doctrine, humanity's state of sin resulting from the Fall of Man. This condition has been characterized in many ways, ranging from something as insignificant as a slight deficiency, or a tendency toward sin yet without collective guilt, referred...

. Pope Clement XI

Pope Clement XI

Pope Clement XI , born Giovanni Francesco Albani, was Pope from 1700 until his death in 1721.-Early life:...

ordered the feast of the Immaculata for the whole Church in 1708. The feast of the Rosary

Rosary

The rosary or "garland of roses" is a traditional Catholic devotion. The term denotes the prayer beads used to count the series of prayers that make up the rosary...

was introduced in 1716, the feast of the Seven Sorrows in 1727. The Angelus

Angelus

The Angelus is a Christian devotion in memory of the Incarnation. The name Angelus is derived from the opening words: Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariæ The Angelus (Latin for "angel") is a Christian devotion in memory of the Incarnation. The name Angelus is derived from the opening words: Angelus...

prayer was strongly supported by Pope Benedict XIII

Pope Benedict XIII

-Footnotes:...

in 1724 and by Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV , born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was Pope from 17 August 1740 to 3 May 1758.-Life:...

in 1742. Popular Marian piety was even more colourful and varied than ever before: Numerous Marian pilgrimage

Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey or search of great moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith...

s, Marian Salve devotion

Devotional song

A devotional song is a hymn which accompanies religious observances and rituals.Each major religion has its own tradition with devotional hymns. In the West, the devotional has been a part of the liturgy in Roman Catholicism, the Greek Orthodox Church, the Russian Orthodox Church, and others, since...

s, new Marian litanies

Litany

A litany, in Christian worship and some forms of Jewish worship, is a form of prayer used in services and processions, and consisting of a number of petitions...

, Marian theatre plays, Marian hymn

Hymn

A hymn is a type of song, usually religious, specifically written for the purpose of praise, adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification...

s, Marian procession

Procession

A procession is an organized body of people advancing in a formal or ceremonial manner.-Procession elements:...

s. Marian fraternities

Fraternal and service organizations

A "fraternal organization" or "fraternity" is a brotherhood, though the term usually connotes a distinct or formal organization. Please list college fraternities and sororities at List of social fraternities and sororities.-International:...

, today mostly defunct, had millions of members.

Pope Innocent XI

Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XIPope Innocent XI

Blessed Pope Innocent XI , born Benedetto Odescalchi, was Pope from 1676 to 1689.-Early life:Benedetto Odescalchi was born at Como in 1611 , the son of a Como nobleman, Livio Odescalchi, and Paola Castelli Giovanelli from Gandino...

viewed the increasing Turkish attacks against Europe, which were supported by France, as the major threat for the Church. He built a Polish-Austrian coalition for the Turkish defeat at Vienna in 1683. Scholars have called him a saintly pope because he reformed abuses by the Church, including simony

Simony

Simony is the act of paying for sacraments and consequently for holy offices or for positions in the hierarchy of a church, named after Simon Magus , who appears in the Acts of the Apostles 8:9-24...

, nepotism

Nepotism

Nepotism is favoritism granted to relatives regardless of merit. The word nepotism is from the Latin word nepos, nepotis , from which modern Romanian nepot and Italian nipote, "nephew" or "grandchild" are also descended....

and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a papal debt of 50,000,000 scudi

Italian scudo

The scudo was the name for a number of coins used in Italy until the 19th century. The name, like that of the French écu and the Spanish and Portuguese escudo, was derived from the Latin scutum . From the 16th century, the name was used in Italy for large silver coins...

. By eliminating certain honorary posts and introducing new fiscal policies, Innocent XI was able to regain control of the church's finances. In France, the Church battled Jansenism

Jansenism

Jansenism was a Christian theological movement, primarily in France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. The movement originated from the posthumously published work of the Dutch theologian Cornelius Otto Jansen, who died in 1638...

and Gallicanism

Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarchs' authority or the State's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope's...

, which supported Councilarism, and rejected papal primacy, demanding special concessions for the Church in France.

France and Gallicanism

In 1685 gallicanistGallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarchs' authority or the State's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope's...

King Louis XIV of France issued the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, ending a century of religious toleration. France forced Catholic theologians to support conciliarism

Conciliarism

Conciliarism, or the conciliar movement, was a reform movement in the 14th, 15th and 16th century Roman Catholic Church which held that final authority in spiritual matters resided with the Roman Church as a corporation of Christians, embodied by a general church council, not with the pope...

and deny Papal infallibility

Papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, by action of the Holy Spirit, the Pope is preserved from even the possibility of error when in his official capacity he solemnly declares or promulgates to the universal Church a dogmatic teaching on faith or morals...

. The king threatened Pope Innocent XI

Pope Innocent XI

Blessed Pope Innocent XI , born Benedetto Odescalchi, was Pope from 1676 to 1689.-Early life:Benedetto Odescalchi was born at Como in 1611 , the son of a Como nobleman, Livio Odescalchi, and Paola Castelli Giovanelli from Gandino...

with a Catholic Ecumenical Council and a military take-over of the Papal state. The absolute

Absolutism (European history)

Absolutism or The Age of Absolutism is a historiographical term used to describe a form of monarchical power that is unrestrained by all other institutions, such as churches, legislatures, or social elites...

French State used Gallicanism to gain control of virtually all major Church appointments as well as many of the Church's properties.

Spread of Christianity

The expansion of the Catholic Portuguese EmpirePortuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire , also known as the Portuguese Overseas Empire or the Portuguese Colonial Empire , was the first global empire in history...

and Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

, with a significant role played by the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

, led to a Christianization of the indigenous populations of the Americas such as the Aztec

Aztec

The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the...

s and Incas. Later waves of colonial expansion such as the struggle for India, by the Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, England, France, Germany and Russia led to Christianization of other populations, such as groups of American Indians

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

and Filipinos

Filipino people

The Filipino people or Filipinos are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the islands of the Philippines. There are about 92 million Filipinos in the Philippines, and about 11 million living outside the Philippines ....

.

Roman Catholic missions

During the Age of DiscoveryAge of Discovery

The Age of Discovery, also known as the Age of Exploration and the Great Navigations , was a period in history starting in the early 15th century and continuing into the early 17th century during which Europeans engaged in intensive exploration of the world, establishing direct contacts with...

, the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

established a number of Missions

Mission (Christian)

Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups , to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not only evangelization , but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged...

in the Americas and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier, born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta was a pioneering Roman Catholic missionary born in the Kingdom of Navarre and co-founder of the Society of Jesus. He was a student of Saint Ignatius of Loyola and one of the first seven Jesuits, dedicated at Montmartre in 1534...

as well as other Jesuits

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

, Augustinians

Augustinians

The term Augustinians, named after Saint Augustine of Hippo , applies to two separate and unrelated types of Catholic religious orders:...

, Franciscans and Dominicans

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

were moving into Asia and the Far East. The Portuguese sent missions into Africa. The most significant failure of Roman missionary work was in Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

, where following increasing civil war in response to Emperor Susenyos's

Susenyos of Ethiopia

Susenyos was of Ethiopia...

conversion to Catholicism, his son and successor Fasilides

Fasilides of Ethiopia

Fasilides was of Ethiopia, and a member of the Solomonic dynasty...

expelled archbishop Afonso Mendes and his Jesuit brethren in 1633, then in 1665 ordered the remaining religious writings of the Catholics burnt. On the other hand, other missions (notably Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ was an Italian Jesuit priest, and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China Mission, as it existed in the 17th-18th centuries. His current title is Servant of God....

's Jesuit mission to China) were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism is the domination of one culture over another. Cultural imperialism can take the form of a general attitude or an active, formal and deliberate policy, including military action. Economic or technological factors may also play a role...

.

The first Catholic Church was built in Beijing

Beijing

Beijing , also known as Peking , is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world, with a population of 19,612,368 as of 2010. The city is the country's political, cultural, and educational center, and home to the headquarters for most of China's...

in 1650. The emperor granted freedom of religion to Catholics. Ricci had modified the Catholic faith to Chinese thinking, permitting among other things the veneration of the dead. The Vatican disagreed and forbade any adaptation in the so-called Chinese Rites controversy

Chinese Rites controversy

The Chinese Rites controversy was a dispute within the Catholic Church from the 1630s to the early 18th century about whether Chinese folk religion rites and offerings to the emperor constituted idolatry...

in 1692 and 1742.

Orthodox Reformation

The fall of ConstantinopleConstantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

in the East, 1453, led to a significant shift of gravity to the rising state of Russia, the "Third Rome". The Renaissance would also stimulate a program of reforms by patriarchs of prayer books. A movement called the "Old believers

Old Believers

In the context of Russian Orthodox church history, the Old Believers separated after 1666 from the official Russian Orthodox Church as a protest against church reforms introduced by Patriarch Nikon between 1652–66...

" consequently resulted and influenced Russian Orthodox theology in the direction of conservatism

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

and Erastianism.

Further reading

- Esler, Phillip F. The Early Christian World. Routledge (2004). ISBN 0415333121.

- White, L. Michael. From Jesus to Christianity. HarperCollins (2004). ISBN 0060526556.

- Freedman, David Noel (Ed). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (2000). ISBN 0802824005.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. The Christian Tradition: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). University of Chicago Press (1975). ISBN 0226653714.

External links

See also

- History of ChristianityHistory of ChristianityThe history of Christianity concerns the Christian religion, its followers and the Church with its various denominations, from the first century to the present. Christianity was founded in the 1st century by the followers of Jesus of Nazareth who they believed to be the Christ or chosen one of God...

- History of ProtestantismHistory of ProtestantismThe Protestant Reformation of the early 16th century was an attempt to reform the Catholic Church.German theologian Martin Luther wrote his Ninety-Five Theses on the sale of indulgences in 1517. Parallel to events in Germany, a movement began in Switzerland under the leadership of Ulrich Zwingli...

- History of the Roman Catholic Church#Baroque, Enlightenment and revolutions

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church#Ottoman Empire

- History of Christian theology#Renaissance and Reformation

- History of Oriental OrthodoxyHistory of Oriental OrthodoxyOriental Orthodoxy is the communion of Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils — the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus. They reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon...

- Timeline of the English Reformation

- Timeline of Christianity#17th century

- Timeline of Christian missions#1600 to 1699

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church#1600–1800

- Chronological list of saints and blesseds in the 17th century

- Timeline of 17th century Muslim historyTimeline of 17th century Muslim history-17th century :* 1601: Khandesh annexed by the Mughals.* 1603: Battle of Urmiyah. The Ottoman Empire suffers defeat. Persia occupies Tabriz, Mesopotamia. Mosul and Diyarbekr...