Diamond-Dybvig model

Encyclopedia

Model (economics)

In economics, a model is a theoretical construct that represents economic processes by a set of variables and a set of logical and/or quantitative relationships between them. The economic model is a simplified framework designed to illustrate complex processes, often but not always using...

of bank run

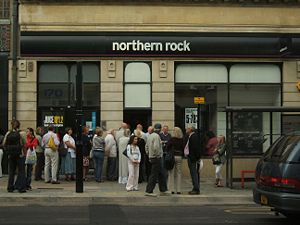

Bank run

A bank run occurs when a large number of bank customers withdraw their deposits because they believe the bank is, or might become, insolvent...

s and related financial crises

Financial crisis

The term financial crisis is applied broadly to a variety of situations in which some financial institutions or assets suddenly lose a large part of their value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and many recessions coincided with these...

. The model shows how banks' mix of illiquid assets (such as business or mortgage loans) and liquid liabilities (deposits which may be withdrawn at any time) may give rise to self-fulfilling panics among depositors.

Theory

The model, published in 1983 by Douglas W. Diamond of the University of ChicagoUniversity of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

and Philip H. Dybvig, then of Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

and now of Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis is a private research university located in suburban St. Louis, Missouri. Founded in 1853, and named for George Washington, the university has students and faculty from all fifty U.S. states and more than 110 nations...

, provides a mathematical statement of the idea that an institution with long-maturity assets and short-maturity liabilities may be unstable.

Structure of the model

Diamond and Dybvig's paper points out that business investment often requires expenditures in the present to obtain returns in the future (for example, spending on machines and buildings now for production in future years). Therefore, when businesses need to borrow to finance their investments, they wish to do so on the understanding that the lender will not demand repayment(s) until some agreed upon time in the future, in other words prefer loans with a long maturityMaturity (finance)

In finance, maturity or maturity date refers to the final payment date of a loan or other financial instrument, at which point the principal is due to be paid....

(that is, low liquidity). The same principle applies to individuals seeking financing to purchase large-ticket items such as housing

House

A house is a building or structure that has the ability to be occupied for dwelling by human beings or other creatures. The term house includes many kinds of different dwellings ranging from rudimentary huts of nomadic tribes to free standing individual structures...

or automobile

Automobile

An automobile, autocar, motor car or car is a wheeled motor vehicle used for transporting passengers, which also carries its own engine or motor...

s. On the other hand, individual savers (both households and firms) may have sudden, unpredictable needs for cash, due to unforeseen expenditures. So they demand liquid accounts which permit them immediate access to their deposits (that is, they value short maturity

Maturity (finance)

In finance, maturity or maturity date refers to the final payment date of a loan or other financial instrument, at which point the principal is due to be paid....

deposit accounts).

The paper regards banks as intermediaries between savers who prefer to deposit in liquid accounts and borrowers who prefer to take out long-maturity loans. Under ordinary circumstances, banks can provide a valuable service by channeling funds from many individual deposits into loans for borrowers. Individual depositors might not be able to make these loans themselves, since they know they may suddenly need immediate access to their funds, whereas the businesses' investments will only pay off in the future (moreover, by aggregating funds from many different depositors, banks help depositors save on the transactions costs they would have to pay in order to lend directly to businesses). Since banks provide a valuable service to both sides (providing the long-maturity loans businesses want and the liquid accounts depositors want), they can charge a higher interest rate on loans than they pay on deposits and thus profit from the difference.

Diamond and Dybvig's crucial point about how banking works is that under ordinary circumstances, savers' unpredictable needs for cash are unlikely to occur at the same time. Therefore, since depositors' needs reflect their individual circumstances, by accepting deposits from many different sources the bank expects only a small fraction of withdrawals in the short term, even though all depositors have the right to take their deposits back at any time. Thus a bank can make loans over a long horizon, while keeping only relatively small amounts of cash on hand to pay any depositors that wish to make withdrawals. (That is, because individual expenditure needs are largely uncorrelated

Correlation

In statistics, dependence refers to any statistical relationship between two random variables or two sets of data. Correlation refers to any of a broad class of statistical relationships involving dependence....

, by the law of large numbers

Law of large numbers

In probability theory, the law of large numbers is a theorem that describes the result of performing the same experiment a large number of times...

banks expect few withdrawals on any one day.)

Nash equilibria of the model

However, since banks have no way of knowing whether their depositors really need the money they withdraw, a different outcome is also possible. Since banks lend out at long maturity, they cannot quickly call in their loans. And even if they tried to call in their loans, borrowers would be unable to pay back quickly, since their loans were, by assumption, used to finance long-term investments. Therefore, if all depositors attempt to withdraw their funds simultaneously, a bank will run out of money long before it is able to pay all the depositors. The bank will be able to pay the first depositors who demand their money back, but if all others attempt to withdraw too, the bank will go bankrupt and the last depositors will be left with nothing.This means that even healthy banks are potentially vulnerable to panics, usually called bank run

Bank run

A bank run occurs when a large number of bank customers withdraw their deposits because they believe the bank is, or might become, insolvent...

s. If a depositor expects all other depositors to withdraw their funds, then it is irrelevant whether the banks' long term loans are likely to be profitable; the only rational response for the depositor is to rush to take his or her deposits out before the other depositors remove theirs. In other words, the Diamond–Dybvig model views bank runs as a type of self-fulfilling prophecy

Self-fulfilling prophecy

A self-fulfilling prophecy is a prediction that directly or indirectly causes itself to become true, by the very terms of the prophecy itself, due to positive feedback between belief and behavior. Although examples of such prophecies can be found in literature as far back as ancient Greece and...

: each depositor's incentive to withdraw funds depends on what they expect other depositors to do. If enough depositors expect other depositors to withdraw their funds, then they all have an incentive to rush to be the first in line to withdraw their funds.

In theoretical terms, the Diamond–Dybvig model provides an example of a game

Game theory

Game theory is a mathematical method for analyzing calculated circumstances, such as in games, where a person’s success is based upon the choices of others...

with more than one Nash equilibrium

Nash equilibrium

In game theory, Nash equilibrium is a solution concept of a game involving two or more players, in which each player is assumed to know the equilibrium strategies of the other players, and no player has anything to gain by changing only his own strategy unilaterally...

. If depositors expect most other depositors to withdraw only when they have real expenditure needs, then it is rational for all depositors to withdraw only when they have real expenditure needs. But if depositors expect most other depositors to rush quickly to close their accounts, then it is rational for all depositors to rush quickly to close their accounts. Of course, the first equilibrium is better than the second (in the sense of Pareto efficiency

Pareto efficiency

Pareto efficiency, or Pareto optimality, is a concept in economics with applications in engineering and social sciences. The term is named after Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist who used the concept in his studies of economic efficiency and income distribution.Given an initial allocation of...

). If depositors withdraw only when they have real expenditure needs, they all benefit from holding their savings in a liquid, interest-bearing account. If instead everyone rushes to close their accounts, then they all lose the interest they could have earned, and some of them lose all their savings. Nonetheless, it is not obvious what any one depositor could do to prevent this mutual loss.

Policy implications

In practice, banks faced with bank runs often shut down and refuse to permit more than a few withdrawals, which is called suspension of convertibility. While this may prevent some depositors who have a real need for cash from obtaining access to their money, it also prevents immediate bankruptcy, thus allowing the bank to wait for its loans to be repaid, so that it has enough resources to pay back some or all of its deposits.However, Diamond and Dybvig argue that unless the total amount of real expenditure needs per period is known with certainty, suspension of convertibility cannot be an optimal mechanism for preventing bank runs. Instead, they argue that a better way of preventing bank runs is deposit insurance

Deposit insurance

Explicit deposit insurance is a measure implemented in many countries to protect bank depositors, in full or in part, from losses caused by a bank's inability to pay its debts when due...

backed by the government or central bank

Central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is a public institution that usually issues the currency, regulates the money supply, and controls the interest rates in a country. Central banks often also oversee the commercial banking system of their respective countries...

. Such insurance pays depositors all or part of their losses in the case of a bank run. If depositors know that they will get their money back even in case of a bank run, they have no reason to participate in a bank run.

Thus, sufficient deposit insurance can eliminate the possibility of bank runs. In principle, maintaining a deposit insurance program is unlikely to be very costly for the government: as long as bank runs are prevented, deposit insurance will never actually need to be paid out. Bank runs became much rarer in the U.S. after the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is a United States government corporation created by the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933. It provides deposit insurance, which guarantees the safety of deposits in member banks, currently up to $250,000 per depositor per bank. , the FDIC insures deposits at...

was founded in the aftermath of the bank panics of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

. On the other hand, a deposit insurance scheme is likely to lead to moral hazard

Moral hazard

In economic theory, moral hazard refers to a situation in which a party makes a decision about how much risk to take, while another party bears the costs if things go badly, and the party insulated from risk behaves differently from how it would if it were fully exposed to the risk.Moral hazard...

: by protecting depositors against bank failure, it makes depositors less careful in choosing where to deposit their money, and thus gives banks less incentive to lend carefully.

"Too big to fail"

Addressing the question of whether too big to failToo Big to Fail

Too Big to Fail is a television drama film in the United States broadcast on HBO on May 23, 2011. It is based on the non-fiction book Too Big to Fail by Andrew Ross Sorkin. The TV film was directed by Curtis Hanson...

is a useful focus for bank regulation, Nobel

Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics, but officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel , is an award for outstanding contributions to the field of economics, generally regarded as one of the...

laureate

Laureate

In English, the word laureate has come to signify eminence or association with literary or military glory. It is also used for winners of the Nobel Prize.-History:...

Paul Krugman

Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman is an American economist, professor of Economics and International Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, Centenary Professor at the London School of Economics, and an op-ed columnist for The New York Times...

wrote:

My basic view is that banking, left to its own devices, inherently poses risks of destabilizing runs; I’m a Diamond–Dybvig guy. To contain banking crises, the government ends up stepping in to protect bank creditors. This in turn means that you have to regulate banks in normal times, both to reduce the need for rescues and to limit the moral hazard posed by the rescues when they happen.

And here’s the key point: it’s not at all clear that the size of individual banks makes much difference to this argument.

See also

- Asset-liability mismatch

- Coordination gameCoordination gameIn game theory, coordination games are a class of games with multiple pure strategy Nash equilibria in which players choose the same or corresponding strategies...

- Liquidity preferenceLiquidity preferenceIn macroeconomic theory, Liquidity preference refers to the demand for money, considered as liquidity. The concept was first developed by John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money to explain determination of the interest rate by the supply and demand...

- Money demandMoney demandThe demand for money is the desired holding of financial assets in the form of money: that is, cash or bank deposits. It can refer to the demand for money narrowly defined as M1 , or for money in the broader sense of M2 or M3....

- Sunspot equilibrium