.gif)

Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)

Encyclopedia

The Greco–Turkish War of 1919–1922, known as the Western Front of the Turkish War of Independence

in Turkey

and the Asia Minor Campaign or the Asia Minor Catastrophe in Greece

, was a series of military events occurring during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

after World War I

between May 1919 and October 1922. The war was fought between Greece

and the Turkish National Movement

who would later establish the Republic of Turkey.

The Greek campaign was launched because the western Allies

, particularly British Prime Minister

David Lloyd George

, had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire

. It ended with Greece giving up all territory gained during the war, returning to its pre-war borders, and engaging in a population exchange with the newly established state of Turkey under provisions in the Treaty of Lausanne

.

The collective failure of the Greek military campaign against the Turkish revolutionaries, coupled with the expulsion of the French military

from the region of Cilicia

, forced the Allies to abandon the Treaty of Sèvres

. Instead, they negotiated a new treaty at Lausanne. This new treaty recognised the independence of the Republic of Turkey and its sovereignty over East Thrace

and Anatolia

.

The geopolitical context of this conflict is linked to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

The geopolitical context of this conflict is linked to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

which was a direct consequence of World War I

and involvement of the Ottomans in the Middle Eastern theatre

. The Greeks received an order to land in Smyrna

by the Triple Entente

as part of the partition. During this war, the Ottoman government collapsed completely and the Ottoman Empire was divided amongst the victorious Entente powers with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres

on August 10, 1920.

There were a number of secret agreements regarding the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. The Triple Entente had made contradictory promises about post-war arrangements concerning Greek hopes in Asia Minor

.

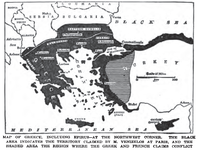

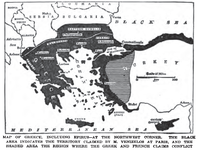

At the Paris Peace Conference, 1919

, Eleftherios Venizelos

lobbied hard for an expanded Hellas (the Megali Idea

) that would include the large Greek communities in Northern Epirus

, Thrace

and Asia Minor. The western Allies, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire if Greece entered the war on the Allied side. These included Eastern Thrace, the islands of Imbros

(İmroz, since 29 July 1979 Gökçeada) and Tenedos

(Bozcaada), and parts of western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna, which contained sizable ethnic Greek populations.

The Italian and Anglo-French repudiation of the Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne

signed on April 26, 1917, which settled the "Middle Eastern interest" of Italy, was overridden with the Greek occupation, as Smyrna (İzmir) was part of the agreements promised to Italy. Before the occupation the Italian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, angry about the possibility of the Greek occupation of Western Anatolia, left the conference and did not return to Paris until May 5. The absence of the Italian delegation from the Conference ended up facilitating Lloyd George's efforts to persuade France and the United States in Greece’s favor to prevent Italian operations in Western Anatolia.

According to some historians, it was the Greek occupation of Smyrna that created the Turkish National movement. Arnold J. Toynbee

for example argued that "The war between Turkey and Greece which burst out at this time was a defensive war for safeguarding of the Turkish homelands in Anatolia. It was a result of the Allied policy of imperialism operating in a foreign state, the military resources and powers of which were seriously under-estimated; it was provoked by the unwarranted invasion of a Greek army of occupation."

One of the reasons proposed by the Greek government for launching the Asia Minor expedition was that there was a sizeable Greek-speaking Orthodox Christian population inhabiting Anatolia that needed protection. Greeks have lived in Asia Minor since antiquity and before the outbreak of the First World War, up to 2.5 million Greeks lived in the Ottoman Empire. The suggestion that the Greeks constituted the majority of the population in the lands claimed by Greece has been contested by a number of historians. Cedric James Lowe and Michael L. Dockrill also argued that Greek claims about Smyrna were at best debatable, since Greeks constituted perhaps a bare majority, more likely a large minority in the Smyrna Vilayet,"which lay in an overwhelmingly Turkish Anatolia." Precise demographics are further obscured by the Ottoman policy of dividing the population according to religion rather than descent, language or self-identification. On the other hand contemporary British and American statistics (1919) support the point that the Greek element was the most numerous in the region of Smyrna, counting 375,000, while Muslims were 325,000.

Nevertheless, the fear for the safety of the Greek population was a well-founded one; In 1915, an extreme nationalist group called the Young Turks

enacted genocidal policies against the minorities in the Ottoman Empire, slaughtering hundreds of thousands of people. While the Armenian Genocide

is the best known of these events, there were also atrocities towards Greeks in Pontus

and western Anatolia. The Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos stated to a British newspaper that: Greece is not making war against Islam, but against the anachronistic Ottoman Government, and its corrupt, ignominious, and bloody administration, with a view to the expelling it from those territories where the majority of the population consists of Greeks.

To an extent, the above danger was overstated by Venizelos as a negotiating card on the table of Sèvres, in order to gain the support of the Allied governments. For example, the fact that the Young Turks were not in power at the time of the war makes such a justification less straightforward. Most of the leaders of that regime had fled the country at the end of World War I and the Ottoman government in Constantinople

was already under British control. Furthermore, Venizelos had already revealed his desires for annexation of territories from the Ottoman Empire in the early stages of World War I, before these massacres had taken place. In a letter sent to Greek King Constantine

in January 1915, he wrote that: "I have the impression that the concessions to Greece in Asia Minor... would be so extensive that another equally large and not less rich Greece will be added to the doubled Greece which emerged from the victorious Balkan wars"

Ironically, the Greek invasion might instead have precipitated the atrocities that it was supposed to prevent. Arnold J. Toynbee blamed the policies pursued by Great Britain and Greece, and the decisions of the Paris Peace conference as factors leading to the atrocities committed by both sides during the war: "The Greeks of 'Pontus' and the Turks of the Greek occupied territories, were in some degree victims of Mr. Venizelos's and Mr. Lloyd George's original miscalculations at Paris."

One of the main motivations for initiating the war was to realize the Megali (Great) Idea, a core concept of Greek nationalism. The Megali Idea was an irredentist vision of a restoration of a Greater Greece on both sides of the Aegean that would incorporate territories with Greek populations outside the borders of the Kingdom of Greece

One of the main motivations for initiating the war was to realize the Megali (Great) Idea, a core concept of Greek nationalism. The Megali Idea was an irredentist vision of a restoration of a Greater Greece on both sides of the Aegean that would incorporate territories with Greek populations outside the borders of the Kingdom of Greece

, which was initially very small. From the time of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, the Megali Idea had played a major role in Greek politics. Greek politicians, since the independence of the Greek state, had made several speeches on the issue of the "historic inevitability of the expansion of the Greek Kingdom." For instance, Greek politician Ioannis Kolettis voiced this conviction in the assembly in 1844: "There are two great centres of Hellenism. Athens is the capital of the Kingdom. Constantinople is the great capital, the City, the dream and hope of all Greeks."

The Great Idea was not merely the product of 19th century nationalism. It was, in one of its aspects, deeply rooted in many Greeks' religious consciousnesses. This aspect was the recovery of Constantinople for Christendom and the reestablishment of the Christian Byzantine Empire

which had fallen in 1453. "Ever since this time the recovery of St. Sophia and the City had been handed down from generation to generation as the destiny and aspiration of the Greek Orthodox." The Megali Idea, besides Constantinople, included most traditional lands of the Greeks including Crete

, Thessaly

, Epirus

, Macedonia

, Thrace

, the Aegean Islands

, Cyprus

, the coastlands of Asia Minor

and Pontus

on the Black Sea

. Asia Minor was an essential part of the Greek world and an area of enduring Greek cultural dominance. The Greek city-states and later the Byzantine Empire also exercised political control of most of the region, from the Bronze Age

to the 12th century, when the first Seljuk Turk raids reached it.

Even though the Anatolian campaign is often understood under post–World War I concepts as a war of conquest, from the point of view of 19th century Greek nationalism this was just another war of liberation, one to redeem the "enslaved brother," not different from the then recent Balkan Wars

.

The United Kingdom had hoped that strategic considerations might persuade Constantine to join the cause of the Allies of World War I, but the King and his supporters insisted on strict neutrality, especially whilst the outcome of the conflict was hard to predict. In addition, family ties and emotional attachments made it difficult for Constantine to decide which side to support during World War I. The King's dilemma was further increased when the Ottomans and the Bulgarians

, both having grievances and aspirations against the Greek Kingdom, joined the Central Powers

. According to Queen Sophia, Constantine’s dream of "marching into the great city of Hagia Sophia at the head of the Greek army

" was still "in his heart" and it appeared as if the King was ready to enter the war against the Ottoman Empire. The conditions, however, were clear: the occupation of Constantinople had to be undertaken without incurring excessive risk.

Though Constantine did remain decidedly neutral, Prime Minister of Greece Eleftherios Venizelos had from an early point decided that Greece's interests would be best served by joining the Entente and started diplomatic efforts with the Allies to prepare the ground for concessions following an eventual victory. The disagreement and the subsequent dismissal of Venizelos by the King resulted in a deep personal rift between the two, which spilled over into their followers and the wider Greek society. Greece became divided into two radically opposed political camps, as Venizelos set up a separate state in Northern Greece, and eventually, with Allied support, forced the King to abdicate. In May 1917, after the exile of Constantine, Venizélos returned to Athens

and allied with the Entente. Greek military forces (though divided between supporters of the monarchy and supporters of "Venizelism

") began to take part in military operations against the Bulgarian Army

on the border.

The act of entering the war and the preceding events resulted in a deep political and social division in post–World War I Greece. The country's foremost political formations, the Venizelist Liberals and the Royalists, already involved in a long and bitter rivalry over pre-war politics, reached a state of outright hatred towards each other. Both parties viewed the other's actions during the First World War as politically illegitimate and treasonous. This enmity inevitably spread throughout Greek society, creating a deep rift that contributed decisively to the failed Asia Minor

campaign and resulted in much social unrest in the inter war years.

The military aspect of the war begins with the Armistice of Mudros

The military aspect of the war begins with the Armistice of Mudros

. The military operations of the Greco-Turkish war can be roughly divided into three main phases: The first phase, spanning the period from May 1919 to October 1920, encompasses the Greek Landings in Asia Minor

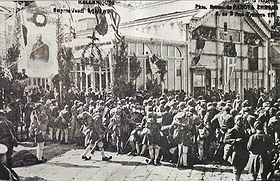

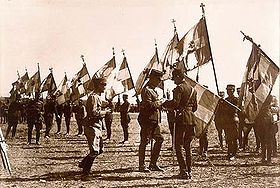

and their consolidation along the Aegean

Coast. The second phase lasted from October 1920 to August 1921, and was characterised by Greek offensive operations. The third and final phase lasted until August 1922, when the strategic initiative was held by the Turkish Army.

The Christian population of Smyrna (mainly Greeks and Armenians), according to different sources, was either forming a minority or a majority compared to Muslim

The Christian population of Smyrna (mainly Greeks and Armenians), according to different sources, was either forming a minority or a majority compared to Muslim

Turkish population of the city. Official Ottoman state census statistics of the time illustrate that the population was majorly Muslim and Turkish. The majority of the Greek population residing in the city greeted the Greek troops as liberators. By contrast, the majority of the Muslim population saw this as an invading force and some Turks resented the Greeks as a result of a long history of conflict and antagonism. Nevertheless, the Greek landings were received by and large passively, only facing sporadic resistance, mainly by small groups of irregular Turkish troops in the suburbs. The majority of the Turkish forces in the region either surrendered peacefully to the Greek Army, or fled to the countryside. .

As Greek troops advanced to the barracks, where the Ottoman commander Ali Nadir Pasha has been ordered to offer no resistance, a Turk in the crowd fired a shot, killing the Greek standard-bearer. Greek troops started firing both at the barracks and the government buildings. Between 300 to 400 Turks were killed or wounded, against 100 Greeks, two of whom were soldiers, on the first day.

(Peramos) and Alaşehir

(Philadelphia). The overall strategic objective of these operations, which were met by increasingly stiff Turkish resistance, was to provide strategic depth to the defence of Izmir (Smyrna). To that end, the Greek zone of occupation was extended over all of Western and most of North-Western Anatolia.

.png) In return for the contribution of the Greek army on the side of the Allies, the Allies supported the assignment of eastern Thrace and the millet of Smyrna to Greece. This treaty ended the First World War

In return for the contribution of the Greek army on the side of the Allies, the Allies supported the assignment of eastern Thrace and the millet of Smyrna to Greece. This treaty ended the First World War

in Asia Minor

and, at the same time, sealed the fate of the Ottoman Empire

. Henceforth, the Ottoman Empire would no longer be a European power.

On August 10, 1920, the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres ceding to Greece Thrace, up to the Chatalja lines. More importantly, Turkey renounced to Greece all rights over Imbros and Tenedos, retaining the small territories of Constantinople, the islands of Marmara, and "a tiny strip of European territory." The Straits of Bosporus were placed under an International Commission, as they were now open to all.

Turkey was furthermore forced to transfer to Greece "the exercise of her rights of sovereignty" over Smyrna in addition to "a considerable Hinterland, merely retaining a ‘flag over an outer fort’." Though Greece administered the Smyrna enclave, its sovereignty remained, nominally, with the Sultan. According to the provisions of the Treaty, Smyrna was to maintain a local parliament and, if within five years time she asked to be incorporated within the Kingdom of Greece, the provision was made that the League of Nations would hold a plebiscite to decide on such matters.

The treaty was never ratified by the Ottoman Empire or Greece.

. The strategic objective of these operations was to defeat the Turkish Nationalists and force Kemal

into peace negotiations. The advancing Greeks, still holding superiority in numbers and modern equipment at this point, had hoped for an early battle in which they were confident of breaking up ill-equipped Turkish forces. Yet they met with little resistance, as the Turks managed to retreat in an orderly fashion and avoid encirclement. Churchill said: "The Greek columns trailed along the country roads passing safely through many ugly defiles

, and at their approach the Turks, under strong and sagacious leadership, vanished into the recesses of Anatolia."

. This incident has been characterized as the "monkey bite that changed the course of Greek history". Venizelos's preference was to declare a Greek republic and thus end the monarchy. However, he was well aware that this would not be acceptable to the European powers.

After King Alexander died leaving no heirs, the general elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1920 suddenly became the focus of a new conflict between the supporters of Venizelos and the Royalists. The anti-Venizelist faction campaigned on the basis of accusations of internal mismanagement and authoritarian attitudes of the government, which, due to the war, had stayed in power without elections since 1915. At the same time they promoted the idea of disengagement in Asia Minor, without though presenting a clear plan as to how this would happen. On the contrary, Venizelos was identified with the continuation of a war that did not seem to go anywhere. The majority of the Greek people were both war-weary and tired of the almost dictatorial regime of the Venizelists, so opted for change. To the surprise of many, Venizelos won only 118 out of the total 369 seats. The crushing defeat obliged Venizelos and a number of his closest supporters to leave the country. To this day many question the rationale for his decision to call elections at that time.

The new government under Dimitrios Gounaris

prepared for a plebiscite on the return of King Constantine. Noting the King's neutrality during World War I

, the Allies warned the Greek government that if he should be returned to the throne they would cut off all financial and military aid to Greece. A month later a plebiscite called for the return of King Constantine. Soon after his return, the King replaced many of the World War I veteran officers and he appointed inexperienced monarchist officers to senior positions. The leadership of the campaign was given to Anastasios Papoulas

, while King Constantine himself assumed nominally the overall command. In addition, many of the remaining venizelist officers resigned appalled by the regime change. The Greek Army which had secured Smyrna

and the Asia Minor coast was purged of Venizelos's supporters while it marched on Ankara.

The Greek advance was halted for the first time at the First Battle of İnönü

on January 11, 1921. Even though this was a minor confrontation involving only one Greek division, it held political significance for the fledging Turkish revolutionaries. This development led to Allied proposals to amend the Treaty of Sèvres at a conference in London

where both the Turkish Revolutionary and Ottoman governments were represented.

Although some agreements were reached with Italy, France and Britain, the decisions were not agreed to by the Greek government, who believed that they still retained the strategic advantage and could yet negotiate from a stronger position. The Greeks initiated another attack on March 27, the Second Battle of İnönü

, where the Turkish troops fiercely resisted and finally defeated the Greeks on March 30. The British favoured a Greek territorial expansion but refused to offer any military assistance in order to avoid provoking the French. The Turkish forces received significant assistance from the newly formed Soviet Union

.

RSFSR and the Turkish Revolutionaries, which was solidified under Treaty of Moscow

in March 1921. The RSFSR supported Kemal with money and ammunition: in 1920 alone, the Lenin government supplied the kemalists with 6.000 rifles, over 5 million rifle cartridges, 17.600 projectiles as well as 200.6 kg of gold bullion; in the subsequent 2 years the amount of aid increased.

Between 27 June and 20 July 1921, a reinforced Greek army of nine divisions

Between 27 June and 20 July 1921, a reinforced Greek army of nine divisions

launched a major offensive, the greatest thus far, against the Turkish troops commanded by Ismet Inönü

on the line of Afyonkarahisar

-Kutahya

-Eskishehir. The plan of the Greeks was to cut Anatolia in two, as the above towns were on the main rail-lines connecting the hinterland with the coast. Eventually, after breaking the stiff Turkish defences, they occupied these strategically important centres. Instead of pursuing and decisively crippling the nationalists' military capacity, the Greek Army halted. In consequence, and despite their defeat, the Turks managed to avoid encirclement and made a strategic retreat on the east of the Sakarya River, where they organised their last line of defence.

This was the major decision that sealed the fate of the Greek campaign in Anatolia. The state and Army leadership, including King Constantine, prime minister

Gounaris

, and General Papoulas, met at Kutahya where they debated the future of the campaign. The Greeks, with their faltering morale rejuvenated, failed to appraise the strategic situation that favoured the defending side; instead, pressed for a 'final solution', the leadership was polarised into the risky decision to pursue the Turks and attack their last line of defence close to Ankara. The military leadership was cautious and requested for more reinforces and time to prepare, but did not go against the politicians. Only few voices supported a defensive stance, including Ioannis Metaxas

. Constantine by this time had little actual power and did not argue either way. After a delay of almost a month that gave time to the Turks to organise their defence, seven of the Greek divisions crossed east of the Sakarya River.

. Constantine's battle cry was "to Angora" and the British officers were invited, in anticipation, to a victory dinner in the city of Kemal. It was envisaged that the Turkish Revolutionaries, who had consistently avoided encirclement would be drawn into battle in defence of their capital and destroyed in a battle of attrition.

Despite the Soviet help, supplies were short as the Turkish army prepared to meet the Greeks. Owners of private rifles, guns and ammunition had to surrender them to the army and every household was required to provide a pair of underclothing, sandals. Meanwhile, the Turkish parliament, not happy with the performance of Ismet Inönü as the Commander of the Western Front, wanted Mustafa Kemal and Chief of General Staff Fevzi Cakmak

to take control.

The advance of the Greek Army faced fierce resistance which culminated in the 21-day Battle of Sakarya

(August 23– September 13, 1921). The Turkish defense positions were centred on series of heights, and the Greeks had to storm and occupy them. The Turks held certain hilltops and lost others, while some were lost and recaptured several times over. Yet the Turks had to conserve men, for the Greeks held the numerical advantage. The crucial moment came when the Greek army tried to take Haymana, 40 kilometers south of Ankara but the Turks held out. Greeks also had their problems, advance into Anatolia lengthened their lines of supply and communication and they were running out of ammunition. The ferocity of the battle exhausted both sides but the Greeks were the first to withdraw to their previous lines. The thunder of cannon was plainly heard in Ankara throughout the battle.

That was the furthest in Anatolia the Greeks would advance, and within few weeks they withdrew in an orderly manner back to the lines that they had held in June. The Turkish Parliament awarded both Mustafa Kemal and Fevzi Cakmak

with the title of Field Marshal

for their service in this battle. To this day no other person has received this five-star general title from the Turkish Republic.

In March 1922, the Allies proposed an armistice. Feeling that he now held the strategic advantage, Mustafa Kemal

declined any settlement while the Greeks remained in Anatolia and intensified his efforts to re-organise the Turkish military for the final offensive against the Greeks. At the same time, the Greeks strengthened their defensive positions, but were increasingly demoralised by the inactivity of remaining on the defensive and the prolongation of the war. The Greek government was desperate to get some military support by the British or at least secure a loan, so it developed an ill-thought plan to force diplomatically the British, by threatening their positions in Constantinople, but this never materialised. The occupation of Constantinople would have been an easy task at this time because the Allied troops garrisoned there were much fewer than the Greek forces in Thrace (two divisions). The end result though was instead to weaken the Greek defences in Smyrna by withrawing troops.

Voices in Greece increasingly called for withdrawal, and demoralizing propaganda spread among the troops. Some of the removed Venizelist officers organised a movement of "National Defense" and planned a coup to secede from Athens, but never gained Venizelos's endorsement and all their actions remained fruitless.

Historian Malcolm Yapp wrote that:

, with half of its soldiers captured or slain and its equipment entirely lost. This date is celebrated as Victory Day, a national holiday in Turkey and salvage day of Kütahya

. During the Battle of Dumlupınar

, Greek General Nikolaos Trikoupis

and General Dionis were captured by the Turkish forces. General Trikoupis only after his capture learned that he was recently appointed Commander-in-Chief

in General Hatzianestis' place. On September 1, Mustafa Kemal issued his famous order to the Turkish army: "Armies, your first goal is the Mediterranean, Forward!"

was captured and the Greek government asked Britain to arrange a truce that would at least preserve its rule in Smyrna. Balikesir

and Bilecik

were taken on September 6, and Aydin

the next day. Manisa

was taken on September 8. The government in Athens resigned. Turkish cavalry entered into Smyrna on September 9. Gemlik and Mudanya fell on September 11, with an entire Greek division surrendering. The expulsion of the Greek Army from Anatolia was completed on September 14. As historian George Lenczowski has put it: "Once started, the offensive was a dazzling success. Within two weeks the Turks drove the Greek army back to the Mediterranean Sea."

The vanguards of Turkish cavalry entered the outskirts of Smyrna on September 8. At the same day, the Greek headquarters had evacuated the town. The Turkish cavalry rode into the town around eleven o'clock on the Saturday morning of September 9. On September 10, with the possibility of social disorder, Mustafa Kemal was quick to issue a proclamation, sentencing any Turkish soldier to death who harmed non-combatants. A few days before the Turkish capture of the city, Kemal's messengers distributed leaflets with this order written in Greek

. Kemal said that Ankara government can't be held responsible in the case of an occurrence of a massacre.

During the confusion and anarchy that followed, a great portion of the city was set ablaze in the Great Fire of Smyrna

, and the properties of the Greeks were pillaged. Most of the eye-witness reports identified that troops from the Turkish army set the fire in the city. Moreover, the fact that only the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city were burned, and that the Turkish quarter stood gives credence to the theory that the Turkish troops burned the city.

, and the Dardanelles

where the Allied garrisons were reinforced by British, French and Italian troops from Constantinople. The British cabinet decided to resist the Turks if necessary at the Dardanelles and to ask for French and Italian help to enable the Greeks to remain in eastern Thrace (see Chanak Crisis

). The British government also issued a request for military support from its colonies. The response from the colonies was negative (with the exception of New Zealand). Furthermore, Italian and French forces abandoned their positions at the straits and left the British alone to face the Turks. On September 24, Kemal's troops moved into the straits zones and refused British requests to leave. The British cabinet was divided on the matter but eventually any possible armed conflict was prevented. British General Harington

, allied commander in Constantinople, kept his men from firing on Turks and warned the British cabinet against any rash adventure. The Greek fleet left Constantinople upon his request. The British finally decided to force the Greeks to withdraw behind Maritsa in Thrace. This convinced Kemal to accept the opening of armistice talks.

The Armistice of Mudanya

The Armistice of Mudanya

was concluded on October 11, 1922. The Allies (Britain

, France

, Italy

) retained control of eastern Thrace

and the Bosporus

. The Greeks were to evacuate these areas. The agreement came into force starting October 15, 1922, one day after the Greek side agreed to sign it.

The Armistice of Mudanya was followed by the Treaty of Lausanne

, a significant provision of which was an exchange of populations. Over one million Greek Orthodox Christians were displaced; most of them were resettled in Attica

and the newly-incorporated Greek territories of Macedonia

and Thrace

and were exchanged with about 500,000 Muslims displaced from the Greek territories.

, the richest and most populous part of Turkey, and the occupation of the Levant, Syria, and Cilicia by the French military in the autumn of 1919. This constituted as great a level of support as Greece could have asked for, so soon after the end of the war. The Kemalist forces scored their first significant victory when they invaded and crushed the Republic of Armenia

. The victories on these fronts allowed the Kemalists to turn their energies on the Greek intrusion in larger numbers.

The major factor contributing to the defeat of the Greeks was the withdrawal of Allied support beginning in the autumn of 1920. The reasons why the Allies shifted so drastically in their policies are complex. One often quoted reason for the apparent lack of support was that King Constantine was reviled by the Entente for his neutral policies during World War I, in contrast to former prime minister Venizelos who brought Greece in the war on their side. Most probably this just served as a pretext

. A more plausible explanation was that exhausted from 4 years of bloodshed, no Entente power had the will to engage in further fighting to enforce the Sèvres treaty. Recognising the rising power of the Turkish Republic, France and Italy preferred to settle their differences with separate agreements, abandoning their plans on the Anatolian lands. Even Lloyd George, who always had voiced support for the Greeks, following Venizelos's lobbying, could do little more than give promises, bound by the military and the Foreign Office 'real politik'. That left Greece to fight practically alone after 1921. The consequences were dire. Greece not only could not expect military help, but also all credit

was stopped immediately. In addition, the Allies did not allow the Greek Navy to effect blockade

, which could have restricted Turkish continuing imports of food and material.

Having adequate supplies

was a constant problem for the Greek Army. Although it was not lacking in men, courage or enthusiasm, it was soon lacking in nearly everything else. Due to her poor economy and lack of manpower, Greece could not sustain long-term mobilisation and had been stretched beyond its limits. Very soon, the Greek Army exceeded the limits of its logistical structure and had no way of retaining such a large territory under constant attack by regular and irregular Turkish troops fighting in and for their homeland. The idea that such large force could sustain offensive by mainly "living off the land" proved wrong.

As the supply situation worsened for the Greeks, things improved for the Turks. Initially, they enjoyed only Soviet support from abroad, in return for giving Batum to the Soviet Union. On August 4, Turkey's representative in Moscow

, Riza Nur

, sent a telegram saying that soon 60 Krupp

artillery pieces, 30,000 shells, 700,000 grenade

s, 10,000 mines, 60,000 Romanian

sword

s, 1.5 million captured Ottoman rifles from World War I, one million Russian rifles, one million Mannlicher rifles, as well as some older British Martini-Henry rifles and 25,000 bayonet

s would be delivered to the Kemalist forces. The Soviets also provided monetary aid to the Turkish national movement, not to the extent that they promised, but almost in sufficient amount to make up the large deficiencies in the promised supply of arms. The Turks in the second phase of the war also received significant military aid from Italy and France, who threw in their lot with the Kemalists against Greece which was seen as a British client. The Italians were embittered from their loss of the Smyrna mandate to the Greeks and they used their base in Antalya to arm and train Turkish troops to assist the Kemalists against the Greeks.

Regardless of other factors, the contrast between the motives and strategic positions of the two sides contributed decisively to the outcome. The Turks were defending their homeland against what they perceived as an imperialist attack. Mustafa Kemal was an intelligent politician, that could present himself as revolutionary to the communists, protector of tradition and order to the conservatives, a patriot soldier to the nationalists, and a Muslim leader for the religious, so he could recruit all Turkish elements and motivate them to fight. In his public speeches, he built up the idea of Anatolia as a "kind of fortress against all the aggressions directed to the East". The struggle was not about Turkey alone but "it is the cause of the east", he said. Turkish national movement attracted sympathizers especially from the Muslims of the far east countries, who were living under colonial regimes and who saw nationalist Turkey as the only independent Muslim nation. The Khilafet Committee in Bombay started a fund to help the Turkish National struggle and sent both financial aid and constant letters of encouragement:

Turkish troops had a determined and competent strategic and tactical command, manned by Great War veterans. They also enjoyed the advantage of being in defence, executed in the new form of 'area defence'. At the climax of the Greek offensive, Mustafa Kemal commanded his troops:

The main defense doctrine of the First World War was holding on a line, so this command was unorthodox for its time. However it proved successful.

On the other side, the Greek defeat directly derived from gradual loss of momentum, the National Schism and poor strategic planning of their ill-conceived advance in depth. The Greek Army was fighting on the background of constant political turmoil and division at the home front. Despite the majority belief into the "moral advantage" of irridentism against the "old enemies", they were not few among them that could not see the point of continuing and they would rather preferred to be back to their homes. The fact that thousands of young men from old Greece were being sacrificed for Asia Minor, while recruitment from the local population was minimal, also caused resentment. The Greeks were advancing without clear strategic targets, wearily following months of bitter fighting and long marches. The main strategy was to manage a fatal blow that would cripple the Turkish military for ever and make the Treaty of Sèvres enforceable. This strategy might have made some sense back then, but in hindsight it proved a fatal miscalculation. The Greeks were instead attacking against an enemy that could continuously retreat to renewed defensive lines, avoiding encirclement and destruction.

wrote that there were organized atrocities since the Greek occupation of Smyrna on the 15 May 1919. Toynbee also stated that he and his wife were witnesses to the atrocities perpetrated by Greeks in the Yalova, Gemlik, and Izmit areas and they not only obtained abundant material evidence in the shape of "burnt and plundred houses, recent corpses, and terror stricken survivors" but also witnessed robbery by Greek civilians and arsons by Greek soldiers in uniform in the act of perpetration. Toynbee wrote that as soon as the Greek Army landed, they started committing atrocities against the Turkish civilians, as they "laid waste the fertile Maender (Meander) Valley", and forced thousands of Turks to take refuge outside the borders of the areas controlled by the Greeks. Historian Taner Akçam

noted that a British officer reported:

James Harbord

, describing the first months of the occupation to the American Senate, wrote that: "The Greek troops and the local Greeks who had joined them in arms started a general massacre of the Mussulmen population in which the officials and Ottoman officers and soldiers as well as the peaceful inhabitants were indiscriminately put to death" Harold Armstrong, a British officer who was a member of the Inter-Allied Commission reported that as the Greeks pushed out from Smynra, they massacred and raped civilians, and burned and pillaged as they went. Marjorie Housepian wrote that 4000 Smyrna Muslims were killed by Greek forces. Johannes Kolmodin was a Swedish orientalist in Smyrna. He wrote in his letters that the Greek army had burned 250 Turkish villages. In another case of atrocity, in one village the Greek army demanded 500 gold liras in order not to pillage the village, however, after the payment of the amount the village was sacked.

The Inter-Allied commission consisted of British, French, American and Italian officers and the representative of the Geneva

International Red Cross, M. Gehri, have prepared two separate collaborating reports upon their investigations in the Yalova-Gemlik Peninsula in which they argued that Greek forces committed systematic atrocities against the Turkish inhabitants. And the commissioners mentioned about the "burning and looting of Turkish villages" and the "explosion of violence of Greeks and Armenians against the Turks", and "a systematic plan of destruction and extinction of the Moslem population". In their report of the 23rd May 1921, the Inter-Allied commission stated that:

Inter Allied commission also stated that the destruction of villages and the disappearance of the Muslim population might have at its objective to create in this region a political situation favourable to the Greek Government.

Arnold J. Toynbee wrote that they obtained convincing evidence that similar atrocities had been started in wide areas all over the remainder of the Greek occupied territories since June 1921. Toynbee argued that: " the situation of the Turks in Smyrna City had become what could be called without exaggeration a 'reign of terror', it was to be inferred that their treatment in the country districts had grown worse in proportion."

James Loder Park, the U.S. Vice-Consul in Constantinople at the time, who toured much of the devastated area immediately after the Greek evacuation, described the situation in the surrounding cities and towns of İzmir he has seen, as follows:

Consul Park concluded:

Kinross wrote, "Already most of the towns in its path were in ruins. One third of Ushak

no longer existed. Alashehir

was no more than a dark scorched cavity, defacing the hillside. Village after village had been reduced to an ash-heap. Out of the eighteen thousand buildings in the historic holy city of Manisa

, only five hundred remained."

It is estimated some 3,000 lives had been lost in the burning of Alaşehir alone. In one of the examples of the Greek atrocities during the retreat, on 14 February 1922, in the Turkish village of Karatepe in Aydin Vilayeti, after being surrounded by the Greeks, all the inhabitants were put into the mosque, then the mosque was burned. The few who escaped fire were shot. The Italian consul, M. Miazzi, reported that he had just visited a Turkish village, where Greeks had slaughtered some sixty women and children. This report was then corroborated by Captain Kocher, the French consul.

, especially of Armenians in the East and the South, and against the Greeks in the Black Sea Region. There was also significant continuity between the organizers of the massacres between 1915–1917 and 1919–1921 in Eastern Anatolia.

A Turkish governor, Ebubekir Hazim Tepeyran in the Sivas Province said in 1919 that the massacres were so horrible that he could not bear to report them. He was referring to the atrocities committed against Greeks in the Black Sea region, and according to the official tally 11,181 Greeks were murdered in 1921 by the Central Army under the command of Nurettin Pasha (who is infamous for the killing of Archbishop Chrysostomos

). Some parliamentary deputies demanded Nurettin Pasha to be sentenced to death and it was decided to put him on trial although the trial was later revoked by the intervention of Mustafa Kemal.

Taner Akcam wrote that according to one newspaper, Nurettin Pasha had suggested to kill all the remaining Greek and Armenian populations in Anatolia, a suggestion rejected by Mustafa Kemal.

There were also several contemporaneous Western newspaper articles reporting the atrocities committed by Turkish forces against Christian population living in Anatolia, mainly Greek and Armenian civilians. For instance, according to the London based Times, "The Turkish authorities frankly state it is their deliberate intention to let all the Greeks die, and their actions support their statement." An Irish paper, the Belfast News Letter wrote, "The appalling tale of barbarity and cruelty now being practiced by the Angora Turks is part of a systematic policy of extermination of Christian minorities in Asia Minor." According to the Christian Science Monitor, the Turks felt that they needed to murder their Christian minorities due to Christian superiority in terms of industriousness and the consequent Turkish feelings of jealously and inferiority, The paper wrote: "The result has been to breed feelings of alarm and jealously in the minds of the Turks which in later years have driven them to depression. They believe that they cannot compete with their Christian subjects in the arts of peace and that the Christians and Greeks especially are too industrious and too well educated as rivals. Therefore from time to time they have striven to try and redress the balance by expulsion and massacre. That has been the position generations past in Turkey again if the Great powers are callous and unwise enough to attempt to perpetuate Turkish misrule over Christians."

According to the newspaper the Scotsman, on August 18 of 1920, in the Feival district of Karamusal, South-East of Ismid in Asia Minor, the Turks massacred 5,000 Christians. There were also massacres during this period against Armenians, continuing the policies of the 1915 Armenian Genocide

according to some Western newspapers. On February 25, 1922 24 Greek villages in the Pontus region were burnt to the ground. An American newspaper, the Atlanta Observer wrote: "The smell of the burning bodies of women and children in Pontus" said the message "comes as a warning of what is awaiting the Christian in Asia Minor after the withdrawal of the Hellenic army." In the first few months of 1922, 10,000 Greeks were killed by advancing Kemalist forces, according to Belfast News Letter . According to the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin the Turks continued the practice of slavery, seizing women and children for their harems and raping numerous women. The Christian Science Monitor wrote that Turkish authorities also prevented missionaries and humanitarian aid groups from assisting Greek civilians who had their homes burned, the Turkish authorities leaving these people to die despite abundant aid. The Christian Science Monitor wrote: "the Turks are trying to exterminate the Greek population with more vigor than they exercised towards the Armenians in 1915."

Atrocities against Pontic Greeks living in the Pontus

region is recognized in Greece and Cyprus as the Pontian Genocide. According to a proclamation made in 2002 by the then-governor of New York

(where a sizeable population of Greek Americans resides), George Pataki

, the Greeks of Asia Minor endured immeasurable cruelty during a Turkish government-sanctioned systematic campaign to displace them; destroying Greek towns and villages and slaughtering additional hundreds of thousands of civilians in areas where Greeks composed a majority, as on the Black Sea coast, Pontus, and areas around Smyrna; those who survived were exiled from Turkey and today they and their descendants live throughout the Greek diaspora

.

By 9 September 1922, the Turkish army had entered Smyrna, with the Greek authorities having left two days before. Large scale disorder followed, with the Christian

population suffering under attacks from soldiers and Turkish inhabitants. The Greek archbishop Chrysostomos

had been lynched by a mob which included Turkish soldiers, and on September 13, a fire from the Armenian quarter of the city had engulfed the Christian waterfront of the city, leaving the city devastated. The responsibility gor the fire is a controversial issue, some sources blame Turks, and some sources blame Greeks or Armenians. Some 50,000 to 100,000 Greeks and Armenians were killed in the fire and accompanying massacres.

According to the population exchange treaty

signed by both the Turkish and Greek governments, Greek orthodox citizens of Turkey and Muslim citizens residing in Greece were subjected to the population exchange between these two countries. Approximately 1.5 million Greeks from Turkey and about half a million Muslims from Greece were uprooted from their homelands. M. Norman Naimark claimed that this treaty was the last part of an ethnic cleansing

campaign to create an ethnically pure homeland for the Turks Historian Dinah Shelton similarly wrote that: "the Lausanne Treaty completed the forcible transfer of the country's Greeks

".

Larger part of the Greek population had been forced to leave their ancestral homelands of Ionia

, Pontus

and Eastern Thrace between 1914–22. These refugees, as well as the Greek American

s with origins in Anatolia, were not allowed to return to their homelands after the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne

.

Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence was a war of independence waged by Turkish nationalists against the Allies, after the country was partitioned by the Allies following the Ottoman Empire's defeat in World War I...

in Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

and the Asia Minor Campaign or the Asia Minor Catastrophe in Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, was a series of military events occurring during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

The Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire was a political event that occurred after World War I. The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples formerly ruled by the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new nations.The partitioning was planned from the early days of the war,...

after World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

between May 1919 and October 1922. The war was fought between Greece

Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was a state established in 1832 in the Convention of London by the Great Powers...

and the Turkish National Movement

Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries which resulted in the creation and shaping of the Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I....

who would later establish the Republic of Turkey.

The Greek campaign was launched because the western Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

, particularly British Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

, had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. It ended with Greece giving up all territory gained during the war, returning to its pre-war borders, and engaging in a population exchange with the newly established state of Turkey under provisions in the Treaty of Lausanne

Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne was a peace treaty signed in Lausanne, Switzerland on 24 July 1923, that settled the Anatolian and East Thracian parts of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The treaty of Lausanne was ratified by the Greek government on 11 February 1924, by the Turkish government on 31...

.

The collective failure of the Greek military campaign against the Turkish revolutionaries, coupled with the expulsion of the French military

Franco-Turkish War

The Franco-Turkish War or Cilicia War was a series of conflicts fought between France and Turkish National Forces directed by Turkish Grand National Assembly from May 1920-October 1921 in the aftermath of World War I...

from the region of Cilicia

Cilicia

In antiquity, Cilicia was the south coastal region of Asia Minor, south of the central Anatolian plateau. It existed as a political entity from Hittite times into the Byzantine empire...

, forced the Allies to abandon the Treaty of Sèvres

Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres was the peace treaty between the Ottoman Empire and Allies at the end of World War I. The Treaty of Versailles was signed with Germany before this treaty to annul the German concessions including the economic rights and enterprises. Also, France, Great Britain and Italy...

. Instead, they negotiated a new treaty at Lausanne. This new treaty recognised the independence of the Republic of Turkey and its sovereignty over East Thrace

East Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace , also known as Turkish Thrace, is the part of the modern republic of Turkey that is geographically part of Europe, all in the eastern part of the historical region of Thrace; most of Turkey is in Anatolia, also known as Asia Minor. Turkish Thrace is also called...

and Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

.

Geopolitical context

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

which was a direct consequence of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

and involvement of the Ottomans in the Middle Eastern theatre

Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I was the scene of action between 29 October 1914, and 30 October 1918. The combatants were the Ottoman Empire, with some assistance from the other Central Powers, and primarily the British and the Russians among the Allies of World War I...

. The Greeks received an order to land in Smyrna

Izmir

Izmir is a large metropolis in the western extremity of Anatolia. The metropolitan area in the entire Izmir Province had a population of 3.35 million as of 2010, making the city third most populous in Turkey...

by the Triple Entente

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente was the name given to the alliance among Britain, France and Russia after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907....

as part of the partition. During this war, the Ottoman government collapsed completely and the Ottoman Empire was divided amongst the victorious Entente powers with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres

Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres was the peace treaty between the Ottoman Empire and Allies at the end of World War I. The Treaty of Versailles was signed with Germany before this treaty to annul the German concessions including the economic rights and enterprises. Also, France, Great Britain and Italy...

on August 10, 1920.

There were a number of secret agreements regarding the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. The Triple Entente had made contradictory promises about post-war arrangements concerning Greek hopes in Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

.

At the Paris Peace Conference, 1919

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. It took place in Paris in 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities...

, Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Venizelos was an eminent Greek revolutionary, a prominent and illustrious statesman as well as a charismatic leader in the early 20th century. Elected several times as Prime Minister of Greece and served from 1910 to 1920 and from 1928 to 1932...

lobbied hard for an expanded Hellas (the Megali Idea

Megali Idea

The Megali Idea was an irredentist concept of Greek nationalism that expressed the goal of establishing a Greek state that would encompass all ethnic Greek-inhabited areas, since large Greek populations after the restoration of Greek independence in 1830 still lived under Ottoman rule.The term...

) that would include the large Greek communities in Northern Epirus

Northern Epirus

Northern Epirus is a term used to refer to those parts of the historical region of Epirus, in the western Balkans, that are part of the modern Albania. The term is used mostly by Greeks and is associated with the existence of a substantial ethnic Greek population in the region...

, Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

and Asia Minor. The western Allies, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire if Greece entered the war on the Allied side. These included Eastern Thrace, the islands of Imbros

Imbros

Imbros or Imroz, officially referred to as Gökçeada since July 29, 1970 , is an island in the Aegean Sea and the largest island of Turkey, part of Çanakkale Province. It is located at the entrance of Saros Bay and is also the westernmost point of Turkey...

(İmroz, since 29 July 1979 Gökçeada) and Tenedos

Tenedos

Tenedos or Bozcaada or Bozdja-Ada is a small island in the Aegean Sea, part of the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale province in Turkey. , Tenedos has a population of about 2,354. The main industries are tourism, wine production and fishing...

(Bozcaada), and parts of western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna, which contained sizable ethnic Greek populations.

The Italian and Anglo-French repudiation of the Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne

Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne

The Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne was an agreement between France, Italy and the United Kingdom, signed at Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne on April 26, 1917, and endorsed August 18 – September 26, 1917. It was drafted by the Italian foreign ministry as a tentative agreement to settle its Middle...

signed on April 26, 1917, which settled the "Middle Eastern interest" of Italy, was overridden with the Greek occupation, as Smyrna (İzmir) was part of the agreements promised to Italy. Before the occupation the Italian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, angry about the possibility of the Greek occupation of Western Anatolia, left the conference and did not return to Paris until May 5. The absence of the Italian delegation from the Conference ended up facilitating Lloyd George's efforts to persuade France and the United States in Greece’s favor to prevent Italian operations in Western Anatolia.

According to some historians, it was the Greek occupation of Smyrna that created the Turkish National movement. Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee CH was a British historian whose twelve-volume analysis of the rise and fall of civilizations, A Study of History, 1934–1961, was a synthesis of world history, a metahistory based on universal rhythms of rise, flowering and decline, which examined history from a global...

for example argued that "The war between Turkey and Greece which burst out at this time was a defensive war for safeguarding of the Turkish homelands in Anatolia. It was a result of the Allied policy of imperialism operating in a foreign state, the military resources and powers of which were seriously under-estimated; it was provoked by the unwarranted invasion of a Greek army of occupation."

The Greek community in Anatolia

| Distribution of Nationalities in Ottoman Empire (Anatolia), Ottoman Official Statistics, 1910 |

|||||||

| Provinces | Turks | Greeks | Armenians | Jews | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Istambul (Asiatic shore) | 135,681 | 70,906 | 30,465 | 5,120 | 16,812 | 258,984 | |

| Ismid | 184,960 | 78,564 | 50,935 | 2,180 | 1,435 | 318,074 | |

| Aidin (Izmir) | 974,225 | 629,002 | 17,247 | 24,361 | 58,076 | 1,702,911 | |

| Bursa | 1,346,387 | 274,530 | 87,932 | 2,788 | 6,125 | 1,717,762 | |

| Konya | 1,143,335 | 85,320 | 9,426 | 720 | 15,356 | 1,254,157 | |

| Ankara | 991,666 | 54,280 | 101,388 | 901 | 12,329 | 1,160,564 | |

| Trebizond | 1,047,889 | 351,104 | 45,094 | - | - | 1,444,087 | |

| Sivas | 933,572 | 98,270 | 165,741 | - | - | 1,197,583 | |

| Kastamon | 1,086,420 | 18,160 | 3,061 | - | 1,980 | 1,109,621 | |

| Adana | 212,454 | 88,010 | 81,250 | – | 107,240 | 488,954 | |

| Bigha | 136,000 | 29,000 | 2,000 | 3,300 | 98 | 170,398 | |

| Total % |

8,192,589 75,7% |

1,777,146 16,42% |

594,539 5,50% |

39,370 0,36% |

219,451 2,03% |

10,823,095 | |

| Ecumenical Patriarchate Statistics, 1912 | |||||||

| Total % |

7,048,662 72,7% |

1,788,582 18,45% |

608,707 6,28% |

37,523 0,39 |

218,102 2,25% |

9,695,506 | |

One of the reasons proposed by the Greek government for launching the Asia Minor expedition was that there was a sizeable Greek-speaking Orthodox Christian population inhabiting Anatolia that needed protection. Greeks have lived in Asia Minor since antiquity and before the outbreak of the First World War, up to 2.5 million Greeks lived in the Ottoman Empire. The suggestion that the Greeks constituted the majority of the population in the lands claimed by Greece has been contested by a number of historians. Cedric James Lowe and Michael L. Dockrill also argued that Greek claims about Smyrna were at best debatable, since Greeks constituted perhaps a bare majority, more likely a large minority in the Smyrna Vilayet,"which lay in an overwhelmingly Turkish Anatolia." Precise demographics are further obscured by the Ottoman policy of dividing the population according to religion rather than descent, language or self-identification. On the other hand contemporary British and American statistics (1919) support the point that the Greek element was the most numerous in the region of Smyrna, counting 375,000, while Muslims were 325,000.

Nevertheless, the fear for the safety of the Greek population was a well-founded one; In 1915, an extreme nationalist group called the Young Turks

Young Turks

The Young Turks , from French: Les Jeunes Turcs) were a coalition of various groups favouring reformation of the administration of the Ottoman Empire. The movement was against the absolute monarchy of the Ottoman Sultan and favoured a re-installation of the short-lived Kanûn-ı Esâsî constitution...

enacted genocidal policies against the minorities in the Ottoman Empire, slaughtering hundreds of thousands of people. While the Armenian Genocide

Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide—also known as the Armenian Holocaust, the Armenian Massacres and, by Armenians, as the Great Crime—refers to the deliberate and systematic destruction of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire during and just after World War I...

is the best known of these events, there were also atrocities towards Greeks in Pontus

Pontus

Pontus or Pontos is a historical Greek designation for a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in modern-day northeastern Turkey. The name was applied to the coastal region in antiquity by the Greeks who colonized the area, and derived from the Greek name of the Black Sea: Πόντος...

and western Anatolia. The Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos stated to a British newspaper that: Greece is not making war against Islam, but against the anachronistic Ottoman Government, and its corrupt, ignominious, and bloody administration, with a view to the expelling it from those territories where the majority of the population consists of Greeks.

To an extent, the above danger was overstated by Venizelos as a negotiating card on the table of Sèvres, in order to gain the support of the Allied governments. For example, the fact that the Young Turks were not in power at the time of the war makes such a justification less straightforward. Most of the leaders of that regime had fled the country at the end of World War I and the Ottoman government in Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

was already under British control. Furthermore, Venizelos had already revealed his desires for annexation of territories from the Ottoman Empire in the early stages of World War I, before these massacres had taken place. In a letter sent to Greek King Constantine

Constantine I of Greece

Constantine I was King of Greece from 1913 to 1917 and from 1920 to 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Army during the unsuccessful Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and led the Greek forces during the successful Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, in which Greece won Thessaloniki and doubled in...

in January 1915, he wrote that: "I have the impression that the concessions to Greece in Asia Minor... would be so extensive that another equally large and not less rich Greece will be added to the doubled Greece which emerged from the victorious Balkan wars"

Ironically, the Greek invasion might instead have precipitated the atrocities that it was supposed to prevent. Arnold J. Toynbee blamed the policies pursued by Great Britain and Greece, and the decisions of the Paris Peace conference as factors leading to the atrocities committed by both sides during the war: "The Greeks of 'Pontus' and the Turks of the Greek occupied territories, were in some degree victims of Mr. Venizelos's and Mr. Lloyd George's original miscalculations at Paris."

Greek nationalism

Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was a state established in 1832 in the Convention of London by the Great Powers...

, which was initially very small. From the time of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, the Megali Idea had played a major role in Greek politics. Greek politicians, since the independence of the Greek state, had made several speeches on the issue of the "historic inevitability of the expansion of the Greek Kingdom." For instance, Greek politician Ioannis Kolettis voiced this conviction in the assembly in 1844: "There are two great centres of Hellenism. Athens is the capital of the Kingdom. Constantinople is the great capital, the City, the dream and hope of all Greeks."

The Great Idea was not merely the product of 19th century nationalism. It was, in one of its aspects, deeply rooted in many Greeks' religious consciousnesses. This aspect was the recovery of Constantinople for Christendom and the reestablishment of the Christian Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

which had fallen in 1453. "Ever since this time the recovery of St. Sophia and the City had been handed down from generation to generation as the destiny and aspiration of the Greek Orthodox." The Megali Idea, besides Constantinople, included most traditional lands of the Greeks including Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

, Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

, Epirus

Epirus

The name Epirus, from the Greek "Ήπειρος" meaning continent may refer to:-Geographical:* Epirus - a historical and geographical region of the southwestern Balkans, straddling modern Greece and Albania...

, Macedonia

Macedonia (region)

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan peninsula in southeastern Europe. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time, but nowadays the region is considered to include parts of five Balkan countries: Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, Serbia, as...

, Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

, the Aegean Islands

Aegean Islands

The Aegean Islands are the group of islands in the Aegean Sea, with mainland Greece to the west and north and Turkey to the east; the island of Crete delimits the sea to the south, those of Rhodes, Karpathos and Kasos to the southeast...

, Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

, the coastlands of Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

and Pontus

Pontus

Pontus or Pontos is a historical Greek designation for a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in modern-day northeastern Turkey. The name was applied to the coastal region in antiquity by the Greeks who colonized the area, and derived from the Greek name of the Black Sea: Πόντος...

on the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

. Asia Minor was an essential part of the Greek world and an area of enduring Greek cultural dominance. The Greek city-states and later the Byzantine Empire also exercised political control of most of the region, from the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

to the 12th century, when the first Seljuk Turk raids reached it.

Even though the Anatolian campaign is often understood under post–World War I concepts as a war of conquest, from the point of view of 19th century Greek nationalism this was just another war of liberation, one to redeem the "enslaved brother," not different from the then recent Balkan Wars

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans in south-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913.By the early 20th century, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia, the countries of the Balkan League, had achieved their independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large parts of their ethnic...

.

The National Schism in Greece

The National Schism in Greece was the deep split of Greek politics and society between two factions, the one led by Eleftherios Venizelos and the other by King Constantine, that predated World War I but escalated significantly over the decision on which side Greece should support during the war.The United Kingdom had hoped that strategic considerations might persuade Constantine to join the cause of the Allies of World War I, but the King and his supporters insisted on strict neutrality, especially whilst the outcome of the conflict was hard to predict. In addition, family ties and emotional attachments made it difficult for Constantine to decide which side to support during World War I. The King's dilemma was further increased when the Ottomans and the Bulgarians

Bulgarians

The Bulgarians are a South Slavic nation and ethnic group native to Bulgaria and neighbouring regions. Emigration has resulted in immigrant communities in a number of other countries.-History and ethnogenesis:...

, both having grievances and aspirations against the Greek Kingdom, joined the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

. According to Queen Sophia, Constantine’s dream of "marching into the great city of Hagia Sophia at the head of the Greek army

Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army , formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece.The motto of the Hellenic Army is , "Freedom Stems from Valor", from Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War...

" was still "in his heart" and it appeared as if the King was ready to enter the war against the Ottoman Empire. The conditions, however, were clear: the occupation of Constantinople had to be undertaken without incurring excessive risk.

Though Constantine did remain decidedly neutral, Prime Minister of Greece Eleftherios Venizelos had from an early point decided that Greece's interests would be best served by joining the Entente and started diplomatic efforts with the Allies to prepare the ground for concessions following an eventual victory. The disagreement and the subsequent dismissal of Venizelos by the King resulted in a deep personal rift between the two, which spilled over into their followers and the wider Greek society. Greece became divided into two radically opposed political camps, as Venizelos set up a separate state in Northern Greece, and eventually, with Allied support, forced the King to abdicate. In May 1917, after the exile of Constantine, Venizélos returned to Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

and allied with the Entente. Greek military forces (though divided between supporters of the monarchy and supporters of "Venizelism

Venizelism

Venizelism was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid 1970s.- Ideology :Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:*Opposition to Monarchy...

") began to take part in military operations against the Bulgarian Army

Military of Bulgaria

The Military of Bulgaria, officially the Bulgarian Army represents the Armed Forces of the Republic of Bulgaria. The Commander-in-Chief is the President of Bulgaria . The Ministry of Defence is in charge of political leadership while military command remains in the hands of the General Staff,...

on the border.

The act of entering the war and the preceding events resulted in a deep political and social division in post–World War I Greece. The country's foremost political formations, the Venizelist Liberals and the Royalists, already involved in a long and bitter rivalry over pre-war politics, reached a state of outright hatred towards each other. Both parties viewed the other's actions during the First World War as politically illegitimate and treasonous. This enmity inevitably spread throughout Greek society, creating a deep rift that contributed decisively to the failed Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

campaign and resulted in much social unrest in the inter war years.

Greek expansion

Armistice of Mudros

The Armistice of Moudros , concluded on 30 October 1918, ended the hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I...

. The military operations of the Greco-Turkish war can be roughly divided into three main phases: The first phase, spanning the period from May 1919 to October 1920, encompasses the Greek Landings in Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

and their consolidation along the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

Coast. The second phase lasted from October 1920 to August 1921, and was characterised by Greek offensive operations. The third and final phase lasted until August 1922, when the strategic initiative was held by the Turkish Army.

Occupation of Smyrna (May 1919)

On May 15, 1919, twenty thousand Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna and took control of the city and its surroundings under cover of the Greek, French, and British navies. Legal justifications for the landings was found in the article 7 of the Armistice of Mudros, which allowed the Allies "to occupy any strategic points in the event of any situation arising which threatens the security of Allies." The Greeks had already brought their forces into Eastern Thrace (apart from Constantinople and its region).

Muslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...