Hebrides

Encyclopedia

Archipelago

An archipelago , sometimes called an island group, is a chain or cluster of islands. The word archipelago is derived from the Greek ἄρχι- – arkhi- and πέλαγος – pélagos through the Italian arcipelago...

off the west coast of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

. There are two main groups: the Inner

Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides is an archipelago off the west coast of Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which enjoy a mild oceanic climate. There are 36 inhabited islands and a further 43 uninhabited Inner Hebrides with an area greater than...

and Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

. These islands have a long history of occupation dating back to the Mesolithic

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

and the culture of the residents has been affected by the successive influences of Celtic, Norse and English-speaking peoples. This diversity is reflected in the names given to the islands, which are derived from the languages that have been spoken there in historic and perhaps prehistoric times.

A variety of artists have been inspired by their Hebridean experiences. Today the economy of the islands is dependent on crofting

Croft (land)

A croft is a fenced or enclosed area of land, usually small and arable with a crofter's dwelling thereon. A crofter is one who has tenure and use of the land, typically as a tenant farmer.- Etymology :...

, fishing, tourism, the oil industry and renewable energy

Renewable energy

Renewable energy is energy which comes from natural resources such as sunlight, wind, rain, tides, and geothermal heat, which are renewable . About 16% of global final energy consumption comes from renewables, with 10% coming from traditional biomass, which is mainly used for heating, and 3.4% from...

. The Hebrides lack biodiversity in comparison to mainland Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, but these islands have much to offer the naturalist. Seals, for example, are present around the coasts in internationally important numbers.

Geology, geography and climate

The Hebrides have a diverse geologyGeology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

ranging in age from Precambrian

Precambrian

The Precambrian is the name which describes the large span of time in Earth's history before the current Phanerozoic Eon, and is a Supereon divided into several eons of the geologic time scale...

strata that are amongst the oldest rocks in Europe to Tertiary

Tertiary

The Tertiary is a deprecated term for a geologic period 65 million to 2.6 million years ago. The Tertiary covered the time span between the superseded Secondary period and the Quaternary...

igneous

Igneous rock

Igneous rock is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic rock. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava...

intrusions.

The Hebrides can be divided into two main groups, separated from one another by The Minch

The Minch

The Minch , also called The North Minch, is a strait in north-west Scotland, separating the north-west Highlands, and the northern Inner Hebrides, from Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides...

to the north and the Sea of the Hebrides

Sea of the Hebrides

The Sea of the Hebrides is a portion of the North Atlantic Ocean, located off the coast of western Scotland, separating the mainland and the northern Inner Hebrides islands from the southern Outer Hebrides islands...

to the south. The Inner Hebrides lie closer to mainland Scotland and include Islay

Islay

-Prehistory:The earliest settlers on Islay were nomadic hunter-gatherers who arrived during the Mesolithic period after the retreat of the Pleistocene ice caps. In 1993 a flint arrowhead was found in a field near Bridgend dating from 10,800 BC, the earliest evidence of a human presence found so far...

, Jura

Jura, Scotland

Jura is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, situated adjacent and to the north-east of Islay. Part of the island is designated as a National Scenic Area. Until the twentieth century Jura was dominated - and most of it was eventually owned - by the Campbell clan of Inveraray Castle on Loch...

, Skye, Mull

Isle of Mull

The Isle of Mull or simply Mull is the second largest island of the Inner Hebrides, off the west coast of Scotland in the council area of Argyll and Bute....

, Raasay

Raasay

Raasay is an island between the Isle of Skye and the mainland of Scotland. It is separated from Skye by the Sound of Raasay and from Applecross by the Inner Sound. It is most famous for being the birthplace of the poet Sorley MacLean, an important figure in the Scottish literary renaissance...

, Staffa

Staffa

Staffa from the Old Norse for stave or pillar island, is an island of the Inner Hebrides in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. The Vikings gave it this name as its columnar basalt reminded them of their houses, which were built from vertically placed tree-logs....

and the Small Isles

Small Isles

The Small Isles are a small archipelago of islands in the Inner Hebrides, off the west coast of Scotland. They lie south of Skye and north of Mull and Ardnamurchan – the most westerly point of mainland Scotland.The four main islands are Canna, Rùm, Eigg and Muck...

. There are 36 inhabited islands in this group. The Outer Hebrides are a chain of more than 100 islands and small skerries

Skerry

A skerry is a small rocky island, usually defined to be too small for habitation. It may simply be a rocky reef. A skerry can also be called a low sea stack....

located about 70 kilometres (43.5 mi) west of mainland Scotland. There are 15 inhabited islands in this archipelago. The main islands include Barra

Barra

The island of Barra is a predominantly Gaelic-speaking island, and apart from the adjacent island of Vatersay, to which it is connected by a causeway, is the southernmost inhabited island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland.-Geography:The 2001 census showed that the resident population was 1,078...

, Benbecula

Benbecula

Benbecula is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2001 census it had a usually resident population of 1,249, with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It forms part of the area administered by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar or the Western...

, Berneray, Harris, Lewis

Lewis

Lewis is the northern part of Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Western Isles or Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The total area of Lewis is ....

, North Uist

North Uist

North Uist is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.-Geography:North Uist is the tenth largest Scottish island and the thirteenth largest island surrounding Great Britain. It has an area of , slightly smaller than South Uist. North Uist is connected by causeways to Benbecula...

, South Uist

South Uist

South Uist is an island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. In the 2001 census it had a usually resident population of 1,818. There is a nature reserve and a number of sites of archaeological interest, including the only location in Great Britain where prehistoric mummies have been found. The...

, and St Kilda

St Kilda, Scotland

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago west-northwest of North Uist in the North Atlantic Ocean. It contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom and three other islands , were also used for...

. In total, the islands have an area of approximately 7200 square kilometres (2,779.9 sq mi) and a population of 44,759.

A complication is that there are various descriptions of the scope of the Hebrides. The Collins Encyclopedia of Scotland describes the Inner Hebrides as lying "east of The Minch", which would include any and all offshore islands. There are various islands that lie in the sea lochs such as Eilean Bàn and Eilean Donan

Eilean Donan

Eilean Donan is a small island in Loch Duich in the western Highlands of Scotland. It is connected to the mainland by a footbridge and lies about half a mile from the village of Dornie. Eilean Donan is named after Donnán of Eigg, a Celtic saint martyred in 617...

that might not ordinarily be described as "Hebridean" but no formal definitions exist.

In the past the Outer Hebrides were often referred to as the Long Isle . Today, they are also known as the Western Isles although this phrase can also be used to refer to the Hebrides in general.

The Hebrides have a cool temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerly latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

, due to the influence of the Gulf Stream

Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension towards Europe, the North Atlantic Drift, is a powerful, warm, and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates at the tip of Florida, and follows the eastern coastlines of the United States and Newfoundland before crossing the Atlantic Ocean...

. In the Outer Hebrides the average temperature for the year is 6°C (44°F) in January and 14°C (57°F) in summer. The average annual rainfall in Lewis is 1100 millimetres (43.3 in) and sunshine hours range from 1,100 - 1,200 per annum. The summer days are relatively long and May to August is the driest period.

Prehistory

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

around 6500 BC or earlier, after the climatic conditions improved enough to sustain human settlement. Occupation at a site on Rùm

Rùm

Rùm , a Scottish Gaelic name often anglicised to Rum) is one of the Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides, in the district of Lochaber, Scotland...

is dated to 8590+/-95 uncorrected radiocarbon years BP

Before Present

Before Present years is a time scale used in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events in the past occurred. Because the "present" time changes, standard practice is to use AD 1950 as the origin of the age scale, reflecting the fact that radiocarbon...

, which is amongst the oldest evidence of occupation in Scotland. There are many examples of structures from the Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

period, the finest example being the standing stones at Callanish

Callanish

Callanish is a village on the West Side of the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides , Scotland. A linear settlement with a jetty, it is situated on a headland jutting into Loch Roag, a sea loch...

, dating to the 3rd millennium BC. Cladh Hallan

Cladh Hallan

Cladh Hallan is an archaeological site on the island of South Uist in the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. It is significant as the only place in Great Britain where prehistoric mummies have been found. Excavations were carried out there between 1988 and 2002....

, a Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

settlement on South Uist is the only site in the UK where prehistoric mummies

Mummy

A mummy is a body, human or animal, whose skin and organs have been preserved by either intentional or incidental exposure to chemicals, extreme coldness , very low humidity, or lack of air when bodies are submerged in bogs, so that the recovered body will not decay further if kept in cool and dry...

have been found.

Celtic era

In 55 BC the Greek historian Diodorus SiculusDiodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

wrote that there was an island called Hyperborea (which means "far to the north") where a round temple stood from which the moon appeared only a little distance above the earth every 19 years. This may have been a reference to the stone circle at Callanish. A traveller called Demetrius of Tarsus related to Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

the tale of an expedition to the west coast of Scotland in or shortly before AD 83. He stated that it was a gloomy journey amongst uninhabited islands, but that he had visited one which was the retreat of holy men. He mentioned neither the druids nor the name of the island.

The first written records of native life begin in the 6th century AD when the founding of the kingdom of Dál Riata

Dál Riata

Dál Riata was a Gaelic overkingdom on the western coast of Scotland with some territory on the northeast coast of Ireland...

took place. This encompassed roughly what is now Argyll and Bute

Argyll and Bute

Argyll and Bute is both one of 32 unitary council areas; and a Lieutenancy area in Scotland. The administrative centre for the council area is located in Lochgilphead.Argyll and Bute covers the second largest administrative area of any Scottish council...

and Lochaber

Lochaber

District of Lochaber 1975 to 1996Highland council area shown as one of the council areas of ScotlandLochaber is one of the 16 ward management areas of the Highland Council of Scotland and one of eight former local government districts of the two-tier Highland region...

in Scotland and County Antrim

County Antrim

County Antrim is one of six counties that form Northern Ireland, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,844 km², with a population of approximately 616,000...

in Ireland. The figure of Columba

Columba

Saint Columba —also known as Colum Cille , Colm Cille , Calum Cille and Kolban or Kolbjørn —was a Gaelic Irish missionary monk who propagated Christianity among the Picts during the Early Medieval Period...

looms large in any history of Dál Riata and his founding of a monastery on Iona

Iona

Iona is a small island in the Inner Hebrides off the western coast of Scotland. It was a centre of Irish monasticism for four centuries and is today renowned for its tranquility and natural beauty. It is a popular tourist destination and a place for retreats...

ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain. However, Iona was far from unique. Lismore

Lismore, Scotland

Lismore is a partially Gaelic speaking island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. This fertile, low-lying island was once a major centre of Celtic Christianity, with a monastery founded by Saint Moluag and the seat of the Bishop of Argyll.-Geography:...

in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg

Eigg

Eigg is one of the Small Isles, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is long from north to south, and east to west. With an area of , it is the second largest of the Small Isles after Rùm.-Geography:The main...

, Hinba

Hinba

Hinba is an island in Scotland of unknown location that was the site of a small monastery associated with the Columban church on Iona. Although a number of details are known about the monastery and its early abbots, and various anecdotes dating from the time of Columba of a mystical nature have...

and Tiree

Tiree

-History:Tiree is known for the 1st century BC Dùn Mòr broch, for the prehistoric carved Ringing Stone and for the birds of the Ceann a' Mhara headland....

, are known from the annals.

North of Dál Riata, the Inner and Outer Hebrides were nominally under Pictish control although the historical record is sparse. Hunter (2000) states that in relation to King Bridei I of the Picts

Bridei I of the Picts

Bridei son of Maelchon, was king of the Picts until his death around 584 to 586.Bridei is first mentioned in Irish annals for 558–560, when the Annals of Ulster report "the migration before Máelchú's son i.e. king Bruide". The Ulster annalist does not say who fled, but the later Annals of...

in the sixth century: "As for Shetland, Orkney, Skye and the Western Isles, their inhabitants, most of whom appear to have been Pictish in culture and speech at this time, are likely to have regarded Bridei as a fairly distant presence.”

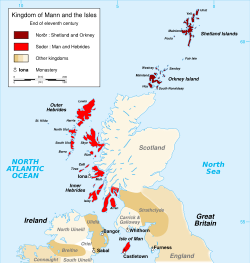

Norwegian control

Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

raids began on Scottish shores towards the end of the 8th century and the Hebrides came under Norse control and settlement during the ensuing decades, especially following the success of Harald Fairhair

Harald I of Norway

Harald Fairhair or Harald Finehair , , son of Halfdan the Black, was the first king of Norway.-Background:Little is known of the historical Harald...

at the Battle of Hafrsfjord

Battle of Hafrsfjord

The Battle of Hafrsfjord has traditionally been regarded as the battle in which western Norway for the first time was unified under one monarch.The national monument of Haraldshaugen was raised in 1872, to commemorate the Battle of Hafrsfjord...

in 872. In the Western Isles Ketill Flatnose may have been the dominant figure of the mid 9th century, by which time he had amassed a substantial island realm and made a variety of alliances with other Norse

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

leaders. These princelings nominally owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown, although in practice the latter's control was fairly limited. Norse control of the Hebrides was formalised in 1098 when Edgar of Scotland

Edgar of Scotland

Edgar or Étgar mac Maíl Choluim , nicknamed Probus, "the Valiant" , was king of Alba from 1097 to 1107...

formally signed the islands over to Magnus III of Norway

Magnus III of Norway

Magnus Barefoot or Magnus III Olafsson was King of Norway from 1093 until 1103 and King of Mann and the Isles from 1099 until 1103.-Background:...

. The Scottish acceptance of Magnus III as King of the Isles came after the Norwegian king had conquered Orkney, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man , otherwise known simply as Mann , is a self-governing British Crown Dependency, located in the Irish Sea between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, within the British Isles. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who holds the title of Lord of Mann. The Lord of Mann is...

in a swift campaign earlier the same year, directed against the local Norwegian leaders of the various island petty kingdoms. By capturing the islands Magnus imposed a more direct royal control, although at a price. His skald

Skald

The skald was a member of a group of poets, whose courtly poetry is associated with the courts of Scandinavian and Icelandic leaders during the Viking Age, who composed and performed renditions of aspects of what we now characterise as Old Norse poetry .The most prevalent metre of skaldic poetry is...

Bjorn Cripplehand recorded that in Lewis "fire played high in the heaven" as "flame spouted from the houses" and that in the Uists "the king dyed his sword red in blood".

The Hebrides were now part of the Kingdom of the Isles

Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles comprised the Hebrides, the islands of the Firth of Clyde and the Isle of Man from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the Suðreyjar, or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the Norðreyjar or Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland...

, whose rulers were themselves vassals of the Kings of Norway. This situation lasted until the partitioning of the Western Isles in 1156, at which time the Outer Hebrides remained under Norwegian control while the Inner Hebrides broke out under Somerled

Somerled

Somerled was a military and political leader of the Scottish Isles in the 12th century who was known in Gaelic as rí Innse Gall . His father was Gillebride...

, the Norse-Celtic kinsman of the Manx royal house.

Following the ill-fated 1263 expedition of Haakon IV of Norway

Haakon IV of Norway

Haakon Haakonarson , also called Haakon the Old, was king of Norway from 1217 to 1263. Under his rule, medieval Norway reached its peak....

, the Outer Hebrides and the Isle of Man were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland as a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth

Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, 1266, ended military conflict between Norway, under King Magnus VI of Norway, and Scotland, under King Alexander III, over the sovereignty of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man....

. Although their contribution to the islands can still be found in personal and place names, the archaeological record of the Norse period is very limited. The best known find is the Lewis chessmen

Lewis chessmen

The Lewis Chessmen are a group of 78 12th-century chess pieces, most of which are carved in walrus ivory...

, which date from the mid 12th century.

Scottish control

Scottish clan

Scottish clans , give a sense of identity and shared descent to people in Scotland and to their relations throughout the world, with a formal structure of Clan Chiefs recognised by the court of the Lord Lyon, King of Arms which acts as an authority concerning matters of heraldry and Coat of Arms...

chiefs including the MacLeods

Clan MacLeod

Clan MacLeod is a Highland Scottish clan associated with the Isle of Skye. There are two main branches of the clan: the Macleods of Harris and Dunvegan, whose chief is Macleod of Macleod, are known in Gaelic as Sìol Tormoid ; the Macleods of Lewis, whose chief is Macleod of The Lewes, are known in...

of Lewis and Harris, Clan Donald

Clan Donald

Clan Donald is one of the largest Scottish clans. There are numerous branches to the clan. Several of these have chiefs recognised by the Lord Lyon King of Arms; these are: Clan Macdonald of Sleat, Clan Macdonald of Clanranald, Clan MacDonell of Glengarry, Clan MacDonald of Keppoch, and Clan...

and MacNeil of Barra

Clan MacNeil

Clan MacNeil, also known in Scotland as Clan Niall, is a highland Scottish clan, particularly associated with the Outer Hebridean island of Barra. The early history of Clan MacNeil is obscure, however despite this the clan claims to descend from the legendary Niall of the nine hostages...

. This transition did little to relieve the islands of internecine strife although by the early 14th century the MacDonald Lords of the Isles

Lord of the Isles

The designation Lord of the Isles is today a title of Scottish nobility with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It emerged from a series of hybrid Viking/Gaelic rulers of the west coast and islands of Scotland in the Middle Ages, who wielded sea-power with fleets of...

, based on Islay, were in theory these chiefs' feudal superiors and managed to exert some control.

The Lords of the Isles ruled the Inner Hebrides as well as part of the Western Highlands as subjects of the King of Scots until John MacDonald

John of Islay, Earl of Ross

John of Islay was a late medieval Scottish magnate. He was Earl of Ross and last Lord of the Isles as well as being Mac Domhnaill, chief of Clan Donald....

, fourth Lord of the Isles, squandered the family's powerful position. A rebellion by his nephew, Alexander of Lochalsh provoked an exasperated James IV

James IV of Scotland

James IV was King of Scots from 11 June 1488 to his death. He is generally regarded as the most successful of the Stewart monarchs of Scotland, but his reign ended with the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Flodden Field, where he became the last monarch from not only Scotland, but also from all...

to forfeit the family's lands in 1493.

In 1598, King James VI authorised some "Gentleman Adventurers" from Fife

Fife adventurers

The Gentleman Adventurers of Fife or Fife Adventurers were a group of 12 Scottish Lowlander colonists awarded lands on the Isle of Lewis by King James VI in 1598 following the forfeiture of all MacLeod lands in 1597 when they failed to produce the title-deeds proving their ownership which had been...

to civilise the "most barbarous Isle of Lewis". Initially successful, the colonists were driven out by local forces commanded by Murdoch and Neil MacLeod, who based their forces on Bearasaigh

Bearasaigh

Bearasaigh or Bearasay is an islet in outer Loch Ròg, Lewis, Scotland. During the late 16th and early 17th centuries it was used as a pirates' hideout and the remains of various buildings from that period still exist...

in Loch Ròg

Loch Ròg

Loch Ròg or Loch Roag is a sea loch on the west coast of Lewis, Outer Hebrides.The waters of Loch Roag are pristine and clear, and are today the source of farmed organic salmon and organic mussels...

. The colonists tried again in 1605 with the same result, but a third attempt in 1607 was more successful and in due course Stornoway

Stornoway

Stornoway is a burgh on the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.The town's population is around 9,000, making it the largest settlement in the Western Isles and the third largest town in the Scottish Highlands after Inverness and Fort William...

became a Burgh of Barony

Burgh of barony

A burgh of barony is a type of Scottish town .They were distinct from royal burghs as the title was granted to a tenant-in-chief, a landowner who held his estates directly from the crown....

. By this time, Lewis was held by the Mackenzies of Kintail

Kintail

Kintail is an area of mountains in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. It consists of the mountains to the north of Glen Shiel and the A87 road between the heads of Loch Duich and Loch Cluanie; its boundaries, other than Glen Shiel, are generally taken to be the valleys of Strath Croe and Gleann...

, (later the Earls of Seaforth

Earl of Seaforth

Earl of Seaforth was a title in the Peerage of Scotland and Peerage of Great Britain. It was held by the family of Mackenzie from 1623 to 1716, and again from 1771 to 1781....

), who pursued a more enlightened approach, investing in fishing

Fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch wild fish. Fish are normally caught in the wild. Techniques for catching fish include hand gathering, spearing, netting, angling and trapping....

in particular. The Seaforths' royalist inclinations led to Lewis becoming garrisoned during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

by Cromwell's

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

troops, who destroyed the old castle in Stornoway.

Early British era

Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name given to the agreement that led to the creation of the united kingdom of Great Britain, the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, which took effect on 1 May 1707...

in 1707, the Hebrides became part of the new Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

, but the clans' loyalties to a distant monarch were not strong. A considerable number of islesmen "came out" in support of the Jacobite Earl of Mar

Earl of Mar

The Mormaer or Earl of Mar is a title that has been created seven times, all in the Peerage of Scotland. The first creation of the earldom was originally the provincial ruler of the province of Mar in north-eastern Scotland...

in the "15"

Jacobite Rising of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715, often referred to as The 'Fifteen, was the attempt by James Francis Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for the exiled House of Stuart.-Background:...

and again in the 1745

Jacobite Rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, often referred to as "The 'Forty-Five," was the attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for the exiled House of Stuart. The rising occurred during the War of the Austrian Succession when most of the British Army was on the European continent...

rising including Macleod of Dunvegan

Dunvegan

Dunvegan is a town on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. It is famous for Dunvegan Castle, seat of the chief of Clan MacLeod...

and MacLea

Clan MacLea

The Clan MacLea is a Highland Scottish clan, which was traditionally located in the district of Lorn in Argyll, Scotland, and is seated on the Isle of Lismore. There is a tradition of some MacLeas Anglicising their names to Livingstone, thus the also refers to clan as the Highland Livingstones...

of Lismore. The aftermath of the decisive Battle of Culloden

Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden was the final confrontation of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. Taking place on 16 April 1746, the battle pitted the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart against an army commanded by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, loyal to the British government...

, which effectively ended Jacobite hopes of a Stuart restoration, was widely felt. The British government's strategy was to estrange the clan chiefs from their kinsmen and turn their descendants into English-speaking landlords whose main concern was the revenues their estates brought rather than the welfare of those who lived on them. This may have brought peace to the islands, but in the following century it came at a terrible price. In the wake of the rebellion, the clan system was broken up and islands of the Hebrides became a series of landed estates.

The early 19th century was a time of improvement and population growth. Roads and quays were built; the slate

Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. The result is a foliated rock in which the foliation may not correspond to the original sedimentary layering...

industry became a significant employer on Easdale

Easdale

Easdale is one of the Slate Islands, in the Firth of Lorn, Scotland. Once the centre of the British slate industry, there has been some recent island regeneration....

and surrounding islands; and the construction of the Crinan

Crinan Canal

The Crinan canal is a canal in the west of Scotland. It takes its name from the village of Crinan at its westerly end. Nine miles long, it connects the village of Ardrishaig on Loch Gilp with the Sound of Jura, providing a navigable route between the Clyde and the Inner Hebrides, without the need...

and Caledonian

Caledonian Canal

The Caledonian Canal is a canal in Scotland that connects the Scottish east coast at Inverness with the west coast at Corpach near Fort William. It was constructed in the early nineteenth century by engineer Thomas Telford, and is a sister canal of the Göta Canal in Sweden, also constructed by...

canals and other engineering works such as Telford's

Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford FRS, FRSE was a Scottish civil engineer, architect and stonemason, and a noted road, bridge and canal builder.-Early career:...

"Bridge across the Atlantic

Clachan Bridge

The Clachan Bridge is a simple, single-arched, hump-backed masonry bridge spanning the Clachan Sound, miles southwest of Oban in Argyll, Scotland....

" improved transport and access. However, in the mid-19th century, the inhabitants of many parts of the Hebrides were devastated by the clearances

Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances were forced displacements of the population of the Scottish Highlands during the 18th and 19th centuries. They led to mass emigration to the sea coast, the Scottish Lowlands, and the North American colonies...

, which destroyed communities throughout the Highlands and Islands

Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands of Scotland are broadly the Scottish Highlands plus Orkney, Shetland and the Hebrides.The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 applied...

as the human populations were evicted and replaced with sheep farms. The position was exacerbated by the failure of the islands' kelp

Kelp

Kelps are large seaweeds belonging to the brown algae in the order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genera....

industry that thrived from the 18th century until the end of the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

in 1815 and large scale emigration became endemic. The "Battle of the Braes

Camastianavaig

Camastianavaig is a crofting township on the island of Skye in Scotland. It is located on the shores of the Sound of Raasay south east of Portree. The Allt Osglan watercourse flows from Loch Fada through the township into Tianavaig Bay.The name is from both Gaelic and Norse, Camas Dìonabhaig...

" involved a demonstration against lack of access to land and the serving of eviction notices. This event was instrumental in the creation of the Napier Commission

Napier Commission

The Napier Commission, officially the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Condition of Crofters and Cottars in the Highlands and Islands was a royal commission and public inquiry into the condition of crofters and cottars in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.The commission was appointed in...

, which reported in 1884 on the situation in the Highlands and disturbances continued until the passing of the 1886 Crofters' Act

Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886

The Crofters' Holdings Act, 1886 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which created legal definitions of crofting parish and crofter, granted security of tenure to crofters and produced the first Crofters Commission, a land court which ruled on disputes between landlords and crofters...

.

Modern economy

For those who remained, new economic opportunities emerged through the export of cattle, commercial fishing and tourism. Nonetheless emigration and military service became the choice of many and the archipelago's populations continued to dwindle throughout the late 19th century and for much of the 20th century. Lengthy periods of continuous occupation notwithstanding, many of the smaller islands were abandoned.There were however continuing gradual economic improvements, among the most visible of which was the replacement of the traditional thatched black house

Black house

A blackhouse is a traditional type of house which used to be common in the Highlands of Scotland, the Hebrides, and Ireland.- Origin of the name :...

with accommodation of a more modern design and with the assistance of Highlands and Islands Enterprise

Highlands and Islands Enterprise

Highlands and Islands Enterprise is the Scottish Government's economic and community development agency for a diverse region which covers more than half of Scotland and is home to around 450,000 people....

many of the islands' populations have begun to increase after decades of decline. The discovery of substantial deposits of North Sea oil

North Sea oil

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid oil and natural gas, produced from oil reservoirs beneath the North Sea.In the oil industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian Sea and the area known as "West of Shetland", "the Atlantic Frontier" or "the...

in 1965 and the renewables sector

Renewable energy in Scotland

The production of renewable energy in Scotland is an issue that has come to the fore in technical, economic, and political terms during the opening years of the 21st century. The natural resource base for renewables is extraordinary by European, and even global standards...

have contributed to a degree of economic stability in recent decades. For example, the Arnish yard has had a chequered history but has been a significant employer in both the oil and renewables industries.

The arts

Hebrides Overture

The Hebrides Overture , Op. 26, also known as Fingal's Cave , is a concert overture composed by Felix Mendelssohn. Written in 1830, the piece was inspired by a cavern known as Fingal's Cave on Staffa, an island in the Hebrides archipelago located off the west coast of Scotland...

, also known as Fingal's Cave

Hebrides Overture

The Hebrides Overture , Op. 26, also known as Fingal's Cave , is a concert overture composed by Felix Mendelssohn. Written in 1830, the piece was inspired by a cavern known as Fingal's Cave on Staffa, an island in the Hebrides archipelago located off the west coast of Scotland...

, is a famous overture composed by Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Barthóldy , use the form 'Mendelssohn' and not 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians gives ' Felix Mendelssohn' as the entry, with 'Mendelssohn' used in the body text...

while residing on these islands, while Granville Bantock

Granville Bantock

Sir Granville Bantock was a British composer of classical music.-Biography:Granville Ransome Bantock was born in London. His father was a Scottish doctor. He was intended by his parents for the Indian Civil Service but was drawn into the musical world. His first teacher was Dr Gordon Saunders at...

composed the Hebridean Symphony. Contemporary musicians associated with the islands include Ian Anderson

Ian Anderson (musician)

Ian Scott Anderson, MBE is a Scottish singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, best known for his work as the leader and flautist of British rock band Jethro Tull.-Early life:...

, Donovan

Donovan

Donovan Donovan Donovan (born Donovan Philips Leitch (born 10 May 1946) is a Scottish singer-songwriter and guitarist. Emerging from the British folk scene, he developed an eclectic and distinctive style that blended folk, jazz, pop, psychedelia, and world music...

and Runrig

Runrig

Runrig are a Scottish Celtic rock group formed in Skye, in 1973 under the name 'The Run Rig Dance Band'. Since its inception, the band's line-up has included songwriters Rory Macdonald and Calum Macdonald. The current line-up also includes longtime members Malcolm Jones, Iain Bayne, and more...

. The poet Sorley MacLean

Sorley MacLean

Sorley MacLean was one of the most significant Scottish poets of the 20th century.-Early life:He was born at Osgaig on the island of Raasay on 26 October 1911, where Scottish Gaelic was the first language. He attended the University of Edinburgh and was an avid shinty player playing for the...

was born on Raasay, the setting for his best known poem, Hallaig

Hallaig

Hallaig is a poem by Sorley MacLean. It was originally written in Scots Gaelic and has also been translated into both English and Lowland Scots. A recent translation was made by Seamus Heaney, an Irish Nobel Prize winner....

.

The novelist Compton Mackenzie

Compton Mackenzie

Sir Compton Mackenzie, OBE was a writer and a Scottish nationalist.-Background:Compton Mackenzie was born in West Hartlepool, England, into a theatrical family of Mackenzies, but many of whose members used Compton as their stage surname, starting with his grandfather Henry Compton, a well-known...

lived on Barra and George Orwell

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair , better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English author and journalist...

wrote 1984 whilst living on Jura. J.M. Barrie's Marie Rose contains references to Harris inspired by a holiday visit to Amhuinnsuidhe Castle

Amhuinnsuidhe Castle

Amhuinnsuidhe Castle is a large private country house on the Isle of Harris, one of the Western Isles off the north-west coast of Scotland. The house was built in 1865 for the 7th Earl of Dunmore, the then owner of the island. Amhuinnsuidhe was designed in the Scottish baronial style by architect...

and he wrote a screenplay for the 1924 film adaptation

Peter Pan (1924 film)

Peter Pan is a 1924 adventure silent film released by Paramount Pictures, the first film adaptation of the play by J. M. Barrie. It was directed by Herbert Brenon and starred Betty Bronson as Peter Pan, Ernest Torrence as Captain Hook, Mary Brian as Wendy, and Virginia Browne Faire as Tinker Bell...

of Peter Pan

Peter and Wendy

Peter and Wendy, published in 1911, is the novelisation by J. M. Barrie of his most famous play Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up...

whilst on Eilean Shona

Eilean Shona

Eilean Shona is a tidal island in Loch Moidart, Scotland. The earlier Gaelic names was Arthraigh, meaning 'foreshore island', similar to the derivation of Erraid....

. Enya

Enya

Enya is an Irish singer, instrumentalist and songwriter. Enya is an approximate transliteration of how Eithne is pronounced in the Donegal dialect of the Irish language, her native tongue.She began her musical career in 1980, when she briefly joined her family band Clannad before leaving to...

's song "Ebudæ" from Shepherd Moons

Shepherd Moons

Shepherd Moons is an album by Irish musician Enya, released on November 4, 1991. It won the Grammy Award for "Best New Age Album" of 1993...

is named for the Hebrides (see below).

Language

It is assumed that Pictish

PICT

PICT is a graphics file format introduced on the original Apple Macintosh computer as its standard metafile format. It allows the interchange of graphics , and some limited text support, between Mac applications, and was the native graphics format of QuickDraw.The original version, PICT 1, was...

must once have predominated in the northern Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides. The Scottish Gaelic language arrived via Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

due to the growing influence of the kingdom of Dál Riata from the 6th century onwards and became the dominant language of the southern Hebrides at that time. For a time, the military might of the Gall-Ghàidhils

Norse-Gaels

The Norse–Gaels were a people who dominated much of the Irish Sea region, including the Isle of Man, and western Scotland for a part of the Middle Ages; they were of Gaelic and Scandinavian origin and as a whole exhibited a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism...

meant that Old Norse was prevalent in the Hebrides and, north of Ardnamurchan

Ardnamurchan

Ardnamurchan is a peninsula in Lochaber, Highland, Scotland, noted for being very unspoilt and undisturbed. Its remoteness is accentuated by the main access route being a single track road for much of its length.-Geography:...

, the place names that existed prior to the 9th century have been all but obliterated. The Old Norse name for the Hebrides during the Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

occupation was Suðreyjar, which means "Southern Isles". It was given in contrast to the Norðreyjar, or the "Northern Isles

Northern Isles

The Northern Isles is a chain of islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The climate is cool and temperate and much influenced by the surrounding seas. There are two main island groups: Shetland and Orkney...

" of Orkney and Shetland.

South of Ardnamurchan Gaelic place names are the most common and, after the 13th century, Gaelic became the main language of the entire Hebridean archipelago. The use of Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

and English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

became prominent in recent times but the Hebrides still contain the largest concentration of Scottish Gaelic speakers in Scotland. This is especially true of the Outer Hebrides, where the majority of people speak the language. The Scottish Gaelic college, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig

Sabhal Mòr Ostaig

Sabhal Mòr Ostaig is a Scottish Gaelic medium college located about north of Armadale on the Sleat peninsula of the island of Skye in northwestern Scotland. It is part of the University of the Highlands and Islands and also has a campus on Islay known as Ionad Chaluim Chille Ìle.The college was...

, is based on Skye and Islay.

Ironically, given the status of the Western Isles as the last Gàidhlig-speaking stronghold in Scotland, the Gaelic language name for the islands – Innse Gall – means "isles of the foreigners" which has roots in the time when they were under Norse colonisation.

Etymology

The earliest written references that have survived relating to the islands were made by Pliny the ElderPliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

in his Natural History, where he states that there are 30 "Hebudes", and makes a separate reference to "Dumna", which Watson (1926) concludes is unequivocally the Outer Hebrides. Writing about 80 years later, in 140-150 AD, Ptolemy

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

, drawing on the earlier naval expeditions of Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola was a Roman general responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. His biography, the De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, was the first published work of his son-in-law, the historian Tacitus, and is the source for most of what is known about him.Born to a noted...

, also distinguished between the Ebudes, of which he writes there were only five (and thus possibly meaning the Inner Hebrides) and Dumna. Later texts in classical Latin, by writers such as Solinus, use the forms Hebudes and Hæbudes.

The names of the individual islands reflect their complex linguistic history. The majority are Norse or Gaelic but the roots of several of the Hebrides may have a pre-Celtic origin and indeed the Haiboudai recorded by Ptolemy may itself be pre-Celtic. Adomnán, the 7th century abbot of Iona, records Colonsay as Colosus and Tiree as Ethica, both of which may be pre-Celtic names. Islay is Ptolemy's Epidion, the use of the "p" hinting at a Brythonic or Pictish tribal name, although the root is not Gaelic and of unknown origin. The etymology of Skye

Etymology of Skye

The etymology of Skye attempts to understand the derivation of the name of the island of Skye in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Skye's history includes the influence of Gaelic, Norse and English speaking peoples and the relationships between their names for the island are not straightforward.The...

is complex and may also include a pre-Celtic root. Lewis is Ljoðhús in Old Norse and although various suggestions have been made as to a Norse meaning (such as "song house") the name is not of Gaelic origin and the Norse credentials are questionable.

The earliest comprehensive written list of Hebridean island names was undertaken by Donald Monro

Donald Monro (Dean)

Donald Monro was a Scottish clergyman, who wrote an early and historically valuable description of the Hebrides and other Scottish islands and enjoyed the honorific title of “Dean of the Isles”.-Origins:...

in 1549, which in some cases also provides the earliest written form of the island name. The derivations of all of the inhabited islands of the Hebrides and some of the larger uninhabited ones are listed below.

Outer Hebrides

Lewis and HarrisLewis and Harris

Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides make up the largest island in Scotland. This is the largest single island of the British Isles after Great Britain and Ireland.-Geography:...

is the largest island in Scotland and the third largest in the British Isles

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

, after Great Britain and Ireland. It incorporates Lewis in the north and Harris in the south, both of which are frequently referred to as individual islands, although they are joined by a land border. Remarkably, the island does not have a common name in either English or Gaelic and is referred to as "Lewis and Harris", "Lewis with Harris", "Harris with Lewis" etc. For this reason it is treated as two separate islands below. The derivation of Lewis may be pre-Celtic (see above) and the origin of Harris is no less problematic. In the Ravenna Cosmography

Ravenna Cosmography

The Ravenna Cosmography was compiled by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna around AD 700. It consists of a list of place-names covering the world from India to Ireland. Textual evidence indicates that the author frequently used maps as his source....

, Erimon may refer to Harris (or possibly the Outer Hebrides as a whole). This word may derive from the Ancient Greek erimos meaning "desert". The origin of Uist

Uist

Uist or The Uists are the central group of islands in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.North Uist and South Uist are linked by causeways running via Benbecula and Grimsay, and the entire group is sometimes known as the Uists....

(Old Norse: Ívist) is similarly unclear.

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Modern Gaelic name | Alternative Derivations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baleshare Baleshare Baleshare is a flat tidal island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.Baleshare lies to the south-west of North Uist. Its economics and community were boosted by the building of a causeway in 1962. The 350m causeway was built by William Tawse Ltd. The island is extremely flat by Hebridean standards,... |

Baile Ear | Gaelic | east town | Baile Sear | ||

| Barra Barra The island of Barra is a predominantly Gaelic-speaking island, and apart from the adjacent island of Vatersay, to which it is connected by a causeway, is the southernmost inhabited island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland.-Geography:The 2001 census showed that the resident population was 1,078... |

Barrøy | Norse | Finbar's island | Barray | Barraigh | |

| Benbecula Benbecula Benbecula is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2001 census it had a usually resident population of 1,249, with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It forms part of the area administered by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar or the Western... |

Peighinn nam Fadhla | Gaelic | pennyland Pennyland A pennyland is an old Scottish land measurement. It was found in the West Highlands, and also Galloway, and believed to be of Norse origin. It is frequently found in minor placenames.Skene in Celtic Scotland says:The Rev... of the fords |

Beinn nam Fadhla | "little mountain of the ford" or "herdsman's mountain" | |

| Berneray Berneray, North Uist Berneray is an island and community in the Sound of Harris, Scotland. It is one of fifteen inhabited islands in the Outer Hebrides. It is famed for its rich and colourful history which has attracted much tourism.... |

Bjarnarøy | Norse | Bjorn's island | Beàrnaraigh | bear island | |

| Eriskay Eriskay Eriskay , from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland. It lies between South Uist and Barra and is connected to South Uist by a causeway which was opened in 2001. In the same year Eriskay became the ferry terminal for... |

Uruisg | Gaelic | goblin island | Eriskeray | Eirisgeigh | Erik's island |

| Flodaigh Flodaigh Flodaigh is a tidal island lying to the north of Benbecula and south of Grimsay in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. It is connected to Benbecula by a causeway.... |

Norse | float island | Flodaigh | |||

| Fraoch-eilean Fraoch-Eilean Fraoch-eilean is a small island north of Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It is about in extent and the highest point is . Its name derives from the Gaelic for "heather island".... |

Gaelic | heather island | Fraoch-eilean | |||

| Great Bernera Great Bernera Great Bernera , often known just as Bernera is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. With an area of just over , it is the thirty-fourth largest Scottish island.... |

Bjarnarøy | English/Norse | Bjorn's island | Berneray-Moir | Beàrnaraigh Mòr | bear island |

| Grimsay Grimsay Grimsay is a tidal island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.Grimsay is the largest of the low-lying stepping-stones which convey the Oitir Mhòr causeway, a five mile arc of single track road linking North Uist and Benbecula via the western tip of Grimsay... |

Norse | Grim's island | Griomasaigh | |||

| Grimsay Grimsay, South East Benbecula Grimsay, south east of Benbecula is a tidal island of the Outer Hebrides. It is connected to Benbecula by a causeway which carries the B891. In the 2001 census, Grimsay had a population of 19.... |

Norse | Grim's island | Griomasaigh | |||

| Harris | Erimon | Ancient Greek? | desert | Harrey | Na Hearadh | Ptolemy's Adru. In Old Norse, a Hérað was a type of administrative district. Alternatives are the Norse haerri, meaning "hills" and Gaelic na h-airdibh meaning "the heights". |

| Lewis Lewis Lewis is the northern part of Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Western Isles or Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The total area of Lewis is .... |

Limnu | Pre-Celtic? | marshy | Lewis | Leòdhas | Ptolemy's Limnu is literally "marshy". The Norse Ljoðhús may mean "song house" - see above. |

| North Uist North Uist North Uist is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.-Geography:North Uist is the tenth largest Scottish island and the thirteenth largest island surrounding Great Britain. It has an area of , slightly smaller than South Uist. North Uist is connected by causeways to Benbecula... |

English/Pre-Celtic? | Ywst | Uibhist a Tuath | "Uist" may possibly be "corn island"or "west" | ||

| Scalpay Scalpay, Outer Hebrides Scalpay to distinguish it from the other Scalpay) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.-Geography:Scalpay is around 2.5 miles long and rises to a height of 341 ft at Beinn Scorabhaig. Scalpay's nearest neighbour, Harris is just 330 yds away over narrow Caolas... |

Skalprøy | Norse | scallop island | Scalpay of Harray | Sgalpaigh na Hearadh | |

| South Uist South Uist South Uist is an island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. In the 2001 census it had a usually resident population of 1,818. There is a nature reserve and a number of sites of archaeological interest, including the only location in Great Britain where prehistoric mummies have been found. The... |

English/Pre-Celtic? | See North Uist | Uibhist a Deas | See North Uist | ||

| Vatersay Vatersay Vatersay is an inhabited island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Vatersay is also the name of the only village on the island.-Location:The westernmost permanently inhabited place in Scotland, Vatersay is linked to Barra by a causeway completed in 1991... |

Norse | water island | Wattersay | Bhatarsaigh | fathers' island, priest island, glove island, wavy island | |

Inner Hebrides

There are various examples of Inner Hebridean island names that were originally Gaelic but have become completely replaced. For example Adomnán records Sainea, Elena, Ommon and Oideacha in the Inner Hebrides, which names must have passed out of usage in the Norse era and whose locations are not clear. One of the complexities is that an island may have had a Celtic name, that was replaced by a similar sounding Norse name, but then reverted to an essentially Gaelic name with a Norse "øy" or "ey" ending. See for example RonaSouth Rona

Rona , sometimes called South Rona to distinguish it from North Rona, is a small island in the Scottish Inner Hebrides, north of Raasay and northeast of Skye. It has a total area of .-Geography and geology:...

below.

{| class="wikitable sortable"

!Island

!Derivation

!Language

!Meaning

!Munro (1549)

!width="10%"|Modern Gaelic name

!Alternative Derivations

|-

| Canna

Canna, Scotland

Canna is the westernmost of the Small Isles archipelago, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It is linked to the neighbouring island of Sanday by a road and sandbanks at low tide. The island is long and wide...

|Cana

| Gaelic

|porpoise island

|Kannay

| Eilean Chanaigh

| Possibly from Old Irish cana, meaning "wolf-whelp" or Norse kneøy - "knee island"

|-

| Coll

Coll

Coll is a small island, west of Mull in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Coll is known for its sandy beaches, which rise to form large sand dunes, for its corncrakes, and for Breachacha Castle.-Geography and geology:...

| Colosus

| Pre-Celtic

|

|

|Colla

| Possibly from Gaelic coll - a hazel

Hazel

The hazels are a genus of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate northern hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family Betulaceae, though some botanists split the hazels into a separate family Corylaceae.They have simple, rounded leaves with double-serrate margins...

|-

| Colonsay

Colonsay

Colonsay is an island in the Scottish Inner Hebrides, located north of Islay and south of Mull and has an area of . It is the ancestral home of Clan Macfie and the Colonsay branch of Clan MacNeill. Aligned on a south-west to north-east axis, it measures in length and reaches at its widest...

|

| Pre-Celtic

|

|Colnansay

| Colbhasa

| Norse for "Columba's island"

|-

| Danna

Danna, Scotland

Danna Island is a tidal island in Argyll and Bute. It is connected to the mainland by a stone causeway and is at the southern end of the narrow Tayvallich peninsula, which separates Loch Sween from the Sound of Jura. It is part of the Ulva, Danna and the MacCormaig Isles SSSI. Danna is part of the...

|

| Norse

| Unknown

|

|Danna

|

|-

| Easdale

Easdale

Easdale is one of the Slate Islands, in the Firth of Lorn, Scotland. Once the centre of the British slate industry, there has been some recent island regeneration....

|

|

|

|Eisdcalfe

| Eilean Eisdeal

| Eas is "waterfall" in Gaelic and dale is the Norse for "valley". However the combination seems inappropriate for this small island. Also known as Ellenabeich - "island of the birches"

|-

| Eigg

Eigg

Eigg is one of the Small Isles, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is long from north to south, and east to west. With an area of , it is the second largest of the Small Isles after Rùm.-Geography:The main...

| Eag

| Gaelic

| a notch

|Egga

| Eige

| Also called Eilean Nimban More - "island of the powerful women" until the 16th century.

|-

| Eilean Bàn

|

| Gaelic

| white isle

|Naban

| Eilean Bàn

|

|-

| Eilean Donan

Eilean Donan

Eilean Donan is a small island in Loch Duich in the western Highlands of Scotland. It is connected to the mainland by a footbridge and lies about half a mile from the village of Dornie. Eilean Donan is named after Donnán of Eigg, a Celtic saint martyred in 617...

|

| Gaelic

|island of Donnán

Donnán of Eigg

Saint Donnán , also known as Donan and Donnán of Eigg, was a Gaelic priest, likely from Ireland, who attempted to introduce Christianity to the Picts of north-western Scotland during the Dark Ages. Saint Donnán is the patron saint of Eigg, an island in the Inner Hebrides...

|

|Eilean Donnáin

|

|-

| Eilean Shona

Eilean Shona

Eilean Shona is a tidal island in Loch Moidart, Scotland. The earlier Gaelic names was Arthraigh, meaning 'foreshore island', similar to the derivation of Erraid....

|

| Norse

| sea island

|

| Eilean Seòna

| Adomnán records the pre-Norse Gaelic name of Airthrago - the foreshore isle".

|-

| Eriska

Eriska

Eriska is a flat, tidal island at the entrance to Loch Creran on the west coast of Scotland. Privately owned, the island is run as a hotel with wooded grounds. The island is evidently populated although no record for the total was provided by the 2001 census....

|

| Norse

| Erik's island

|

|

|

|-

| Erraid

Erraid

The Isle of Erraid is a tidal island approximately one mile square in area located in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. It lies west of Mull and southeast of Iona. The island receives about of rain and 1,350 hours of sunshine annually, making it one of the driest and sunniest places on the western...

| Possibly Arthràigh

|Gaelic

|foreshore island

|Erray

|Eilean Earraid

|

|-

| Gigha

Gigha

The Isle of Gigha is a small island off the west coast of Kintyre in Scotland. The island forms part of Argyll and Bute and has a population of about 150 people, many of whom speak Scottish Gaelic. The climate is mild with higher than average sunshine hours and the soils are fertile.Gigha has a...

| Guðey

|Norse

|"good island" or "God island"

|Gigay

| Giogha

| Various including the Norse Gjáey - "island of the geo

Geo (landscape)

A geo or gio is an inlet, a gully or a narrow and deep cleft in the face of a cliff. Geos are common on the coastline of the Shetland and Orkney islands. They are created by the wave driven erosion of cliffs along faults and bedding planes in the rock. Geos may have sea caves at their heads...

" or "cleft", or "Gydha's isle".

|-

| Gometra

Gometra

-Etymology:According to Gillies Gometra is from the Norse gottr + madr + ey and means "The good-man's island" or "God-man's island". Mac an Tàilleir offers "Godmund's island".-Geography:...

| Goðrmaðrey

| Norse

| "The good-man's island", or "God-man's island"

|

| Gòmastra

| "Godmund's island".

|-

| Isle of Ewe

Isle of Ewe

Isle of Ewe is a small Scottish island on the west coast of Ross and Cromarty.-Geography and geology:The Isle of Ewe is located in Loch Ewe, west of Aultbea in the Ross and Cromarty district of the Highland Region. The island is made up of sandstone and the shore line varies from flat pebble...

| Eubh

| Gaelic

| echo

|Ellan Ew

|Eilean Iùbh

|Old Irish: eo - "yew"

|-

| Iona

Iona

Iona is a small island in the Inner Hebrides off the western coast of Scotland. It was a centre of Irish monasticism for four centuries and is today renowned for its tranquility and natural beauty. It is a popular tourist destination and a place for retreats...

| Hí

|Gaelic

| Possibly "yew

Taxus baccata

Taxus baccata is a conifer native to western, central and southern Europe, northwest Africa, northern Iran and southwest Asia. It is the tree originally known as yew, though with other related trees becoming known, it may be now known as the English yew, or European yew.-Description:It is a small-...

-place"

|Colmkill

|

| Numerous. Adomnán uses Ioua insula which became "Iona" through misreading.

|-

| Islay

Islay

-Prehistory:The earliest settlers on Islay were nomadic hunter-gatherers who arrived during the Mesolithic period after the retreat of the Pleistocene ice caps. In 1993 a flint arrowhead was found in a field near Bridgend dating from 10,800 BC, the earliest evidence of a human presence found so far...

|

| Pre-Celtic

|

|Ila

|

| Various - see above

|-

| Jura

Jura, Scotland

Jura is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, situated adjacent and to the north-east of Islay. Part of the island is designated as a National Scenic Area. Until the twentieth century Jura was dominated - and most of it was eventually owned - by the Campbell clan of Inveraray Castle on Loch...

|Dyrøy

| Norse

|deer island

|Duray

| Diùra

| Norse: Jurøy - udder island

|-

| Kerrera

Kerrera

Kerrera is an island in the Scottish Inner Hebrides, close to the town of Oban. In 2005 it had a population of about 35 people, and it is linked to the mainland by passenger ferry on the Gallanach Road....

| Kjarbarøy

| Norse

| Kjarbar's island

|

|Cearrara

|Norse: ciarrøy' '- "brushwood island" or "copse island"

|-

| Lismore

Lismore, Scotland

Lismore is a partially Gaelic speaking island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. This fertile, low-lying island was once a major centre of Celtic Christianity, with a monastery founded by Saint Moluag and the seat of the Bishop of Argyll.-Geography:...

|

| Gaelic

| big garden

|Lismoir

| Lios Mòr

|

|-

| Luing

Luing

Luing is one of the Slate Islands, Firth of Lorn, in the west of Argyll in Scotland, about 16 miles south of Oban. It has a population of around 200 people, mostly living in Cullipool, Toberonochy , and Blackmillbay...

|

| Gaelic

|ship island

|Lunge

| An t-Eilean Luinn

| Norse: lyng - heather island or pre-Celtic

|-

| Lunga

Lunga, Firth of Lorn

Lunga is one of the Slate Islands in the Firth of Lorn, Scotland. The "Grey Dog" tidal race, which runs in the sea channel to the south, reaches 8 knots in full flood. The name 'Lunga' is derived from the Old Norse for 'isle of the longships', but almost all other place names are Gaelic in origin...

|Langrøy

| Norse

| longship isle

|Lungay

| Lunga

| Gaelic long is also "ship"

|-

| Muck

Muck, Scotland

Muck is the smallest of four main islands in the Small Isles, part of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. It measures roughly 2.5 miles east to west and has a population of around 30, mostly living near the harbour at Port Mòr. The other settlement on the island is the farm at Gallanach...

| Eilean nam Muc

| Gaelic

| isle of pigs

|Swynes Ile

| Eilean nam Muc

|Eilean nam Muc-mhara- "whale island". John of Fordun recorded it as Helantmok - "isle of swine".

|-

| Mull

Isle of Mull

The Isle of Mull or simply Mull is the second largest island of the Inner Hebrides, off the west coast of Scotland in the council area of Argyll and Bute....

| Malaios

| Pre-Celtic

|

|Mull

| Muile

| Recorded by Ptolemy as Malaios possibly meaning "lofty isle". In Norse times it became Mýl.

|-

| Oronsay

Oronsay, Inner Hebrides

Oronsay , also sometimes spelt and pronounced Oransay by the local community, is a small tidal island south of Colonsay in the Scottish Inner Hebrides with an area of just over two square miles....

|

| Norse

| ebb island

|Ornansay

| Orasaigh

| Norse: "Oran's island"

|-

| Raasay

Raasay

Raasay is an island between the Isle of Skye and the mainland of Scotland. It is separated from Skye by the Sound of Raasay and from Applecross by the Inner Sound. It is most famous for being the birthplace of the poet Sorley MacLean, an important figure in the Scottish literary renaissance...

| Raasøy

|Norse

| roe deer island

|Raarsay

| Ratharsair

|Rossøy - "horse island"

|-

| Rona

South Rona

Rona , sometimes called South Rona to distinguish it from North Rona, is a small island in the Scottish Inner Hebrides, north of Raasay and northeast of Skye. It has a total area of .-Geography and geology:...

| Hraunøy or Rònøy

|Norse or Gaelic/Norse

| "rough island" or "seal island"

|Ronay

| Rònaigh

|

|-

| Rùm

Rùm

Rùm , a Scottish Gaelic name often anglicised to Rum) is one of the Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides, in the district of Lochaber, Scotland...

|

|Pre-Celtic

|

|Ronin

| Rùm

| Various including Norse rõm-øy for "wide island" or Gaelic ì-dhruim - "isle of the ridge"

|-

| Sanday

Sanday, Inner Hebrides

Sanday is one of the Small Isles, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It is a tidal island linked to its larger neighbor, Canna, via sandbanks at low tide, and also connected to the larger island by a bridge...

|sandøy

|Norse

|sandy island

|

| Sandaigh

|

|-

| Scalpay

Scalpay, Inner Hebrides

Scalpay is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland.Separated from the east coast of Skye by Loch na Cairidh, Scalpay rises to at Mullach na Càrn. It has an area of almost ten sq. miles....

| Skalprøy

| Norse

| scallop island

|Scalpay

|Sgalpaigh

| Norse: "ship island"

|-

| Seil

Seil

One of the Slate Islands, Seil is a small island on the east side of the Firth of Lorn, southwest of Oban, in Scotland.Seil has been linked to the Scottish mainland since 1792 when the Clachan Bridge was built by engineer Robert Mylne...

|Possibly Sal

| Probably pre-Celtic

|"stream"

|Seill

| Saoil

|Gaelic: sealg - "hunting island"

|-

| Shuna

Shuna, Slate Islands

Shuna is one of the Slate Islands lying east of Luing on the west coast of Scotland.-History:Shuna Castle was built as recently as 1911 for a rumoured cost of £300,000...

| Unknown

|Norse

|Possibly "sea island"

|Seunay

| Siuna

| Gaelic sidhean - "fairy"

|-

| Skye

Skye

Skye or the Isle of Skye is the largest and most northerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate out from a mountainous centre dominated by the Cuillin hills...

| Scitis

|Pre-Celtic?

|Possibly "winged isle"

|Skye

|An t-Eilean Sgitheanach

|Numerous - see above

|-

| Soay

|So-øy

| Norse

| sheep island

| Soa Urettil

| Sòdhaigh

|

|-

| Tanera Mòr

Tanera Mòr

Tanera Mòr is an inhabited island in Loch Broom in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. It is the largest of the Summer Isles and the only inhabited island in that group...

| Hawnarøy

| Norse

|island of the haven

|Hawrarymoir(?)

| Tannara Mòr

|Brythonic: Thanaros, the thunder god

|-

| Tiree

Tiree

-History:Tiree is known for the 1st century BC Dùn Mòr broch, for the prehistoric carved Ringing Stone and for the birds of the Ceann a' Mhara headland....

| Eth, Ethica

|Possibly pre-Celtic

|Unknown

|

| Tioridh

| Norse: Tirvist of unknown meaning and numerous Gaelic versions, some with a possible meaning of "land of corn"

|-

| Ulva

Ulva

Ulva is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, off the west coast of Mull. It is separated from Mull by a narrow strait, and connected to the neighbouring island of Gometra by a bridge. Much of the island is formed from Tertiary basalt rocks, which is formed into columns in places.Ulva has...

| Ulvøy

| Norse

| wolf island

|

| Ulbha

|Ulfr's island

|-

|}

Uninhabited islands

The etymology of St Kilda, a small archipelago west of the Outer Hebrides, and its main island Hirta

Hirta

Hirta is the largest island in the St Kilda archipelago, on the western edge of Scotland. The name "Hiort" and "Hirta" have also been applied to the entire archipelago.-Geography:...

is very complex. No saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

is known by the name of Kilda and various theories have been proposed for the word's origin, which dates from the late 16th century. Haswell-Smith (2004) notes that the full name "St Kilda" first appears on a Dutch map dated 1666, and that it may have been derived from Norse sunt kelda ("sweet wellwater") or from a mistaken Dutch assumption that the spring Tobar Childa was dedicated to a saint. (Tobar Childa is a tautological placename, consisting of the Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic language

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish, and thus descends ultimately from Primitive Irish....

and Norse

Old Norse

Old Norse is a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and inhabitants of their overseas settlements during the Viking Age, until about 1300....

words for well, i.e. "well well"). The origin of the Gaelic for "Hirta", Hiort or Hirt, which long pre-dates the use of "St Kilda", is similarly open to interpretation. Watson (1926) offers the Old Irish hirt, a word meaning "death", possibly relating to the dangerous seas. Maclean (1977), drawing on an Icelandic saga