St Kilda, Scotland

Encyclopedia

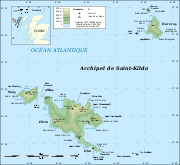

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago

64 kilometres (39.8 mi) west-northwest of North Uist

in the North Atlantic Ocean. It contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides

of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta

, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom and three other islands (Dùn

, Soay

and Boreray

), were also used for grazing and seabird hunting. The islands are administratively a part of the Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

local authority area.

St Kilda may have been permanently inhabited for at least two millennia, the population probably never exceeding 180 (and certainly no more than 100 after 1851). The entire population was evacuated

from Hirta (the only inhabited island) in 1930. Currently, the only year-round residents are defence personnel although a variety of conservation workers, volunteers and scientists spend time there in the summer months.

The origin of the name St Kilda is a matter of conjecture. The islands' human heritage includes numerous unique architectural features from the historic and prehistoric periods, although the earliest written records of island life date from the Late Middle Ages

. The medieval village on Hirta was rebuilt in the 19th century, but the influences of religious zeal, illnesses brought by increased external contacts through tourism, and the First World War

all contributed to the island's evacuation in 1930. The story of St Kilda has attracted artistic interpretations, including an opera

.

The entire archipelago is owned by the National Trust for Scotland

. It became one of Scotland's five World Heritage Site

s in 1986 and is one of the few in the world to hold joint status for its natural and cultural qualities. Two different early sheep types have survived on these remote islands, the Soay

, a Neolithic type, and the Boreray

, an Iron Age type. The islands are a breeding ground for many important seabird

species including Northern Gannet

s, Atlantic Puffin

s, and Northern Fulmar

s. The St Kilda Wren

and St Kilda Field Mouse

are endemic subspecies

. Parties of volunteers work on the islands in the summer to restore the many ruined buildings that the native St Kildans left behind. They share the island with a small military base

established in 1957.

No saint

No saint

is known by the name of Kilda, and various theories have been proposed for the word's origin, which dates from the late 16th century. Haswell-Smith (2004) notes that the full name St Kilda first appears on a Dutch map dated 1666, and that it may have been derived from Norse sunt kelda ("sweet wellwater") or from a mistaken Dutch assumption that the spring Tobar Childa was dedicated to a saint. (Tobar Childa is a tautological placename, consisting of the Gaelic

and Norse

words for well, i.e., "well well"). Martin Martin

, who visited in 1697, believed that the name "is taken from one Kilder, who lived here; and from him the large well Toubir-Kilda has also its name".

Maclean (1972) similarly suggests it may come from a corruption of the Old Norse

Maclean (1972) similarly suggests it may come from a corruption of the Old Norse

name for the spring on Hirta, Childa, and states that a 1588 map identifies the archipelago as Kilda. He also speculates that it may refer to the Culdee

s, anchorite

s who may have brought Christianity to the island, or be a corruption of the Gaelic name for the main island of the group, since the islanders tended to pronounce r as l, and thus habitually referred to the island as Hilta. Steel (1988) adds weight to the idea, noting that the islanders pronounced the H with a "somewhat guttural quality", making the sound they used for Hirta "almost" Kilta. Similary, St Kilda speakers interviewed by the School of Scottish Studies

in the 1960s show individual speakers using t-initial forms, leniting

to /h/, e.g. ann an t-Hirte (an̪ˠən̪ˠ 'tʰʲrˠt̪ə) and gu Hirte (kə 'hirˠʃt̪ə).

Maclean (1972) further suggests that the Dutch may have simply made a cartographical error, and confused Hirta with Skildar, the old name for Haskeir

island much nearer the main Outer Hebrides

archipelago. Quine (2000) hypothesises that the name is derived from a series of cartographical errors, starting with the use of the Old Iceland

ic Skildir ("shields") and appearing as Skildar on a map by Nicholas de Nicolay (1583). This, so the hypothesis goes, was transcribed in error by Lucas J. Waghenaer in his 1592 charts without the trailing r and with a period after the S, creating S.Kilda. This was in turn assumed to stand for a saint by others, creating the form that has been used for several centuries, St Kilda.

The origin of Hirta, which long pre-dates St Kilda, is similarly open to interpretation. Martin (1703) avers that "Hirta is taken from the Irish Ier, which in that language signifies west". Maclean offers several options, including an (unspecified) Celtic word meaning "gloom" or "death", or the Scots Gaelic h-Iar-Tìr ("westland"). Drawing on an Icelandic saga

describing an early 13th-century voyage to Ireland that mentions a visit to the islands of Hirtir, he speculates that the shape of Hirta resembles a stag

, Hirtir ("stags" in Norse). Steel (1998) quotes the view of Reverend Neil Mackenzie, who lived there from 1829 to 1844, that the name is derived from the Gaelic Ì Àrd ("high island"), and a further possibility that it is from the Norse Hirt ("shepherd"). In a similar vein, Murray (1966) speculates that the Norse Hirðö, pronounced 'Hirtha' ("herd island"), may be the origin. All the names of and on the islands are fully discussed by Coates (1990).

The islands are composed of Tertiary

The islands are composed of Tertiary

igneous formations of granites and gabbro

, heavily weathered by the elements. The archipelago represents the remnants of a long-extinct ring volcano rising from a seabed plateau approximately 40 metres (131.2 ft) below sea level.

At 670 hectares (1,655.6 acre) in extent, Hirta

is the largest island in the group and comprises more than 78% of the land area of the archipelago. Next in size are Soay (English: "sheep island") at 99 hectares (244.6 acre) and Boreray ('the fortified isle'), which measures 86 hectares (212.5 acre). Soay is 0.5 kilometre (0.310686368324903 mi) north-west of Hirta, Boreray 6 kilometres (4 mi) to the northeast. Smaller islet

s and stacks

in the group include Stac an Armin

('warrior's stack'), Stac Lee

('grey stack') and Stac Levenish

('stream' or 'torrent'). The island of Dùn ('fort'), which protects Village Bay from the prevailing southwesterly winds, was at one time joined to Hirta by a natural arch. MacLean (1972) suggests that the arch was broken when struck by a galleon

fleeing the defeat of the Spanish Armada

, but other sources, such as Mitchell (1992) and Fleming (2005), provide the more credible (if less romantic) explanation that the arch was simply swept away by one of the many fierce storms that batter the islands every winter.

The highest point in the archipelago, Conachair ('the beacon') at 430 metres (1,410.8 ft), is on Hirta, immediately north of the village. In the southeast is Oiseval ('east fell'), which reaches 290 metres (951.4 ft), and Mullach Mòr ('big hill summit') 361 metres (1,185 ft) is due west of Conachair. Ruival ('red fell') 137 metres (449.5 ft) and Mullach Bi ('pillar summit') 358 metres (1,174.5 ft) dominate the western cliffs. Boreray reaches 384 metres (1,259.8 ft) and Soay 378 metres (1,240.2 ft). The extraordinary Stac an Armin reaches 196 metres (643 ft), and Stac Lee, 172 metres (564.3 ft), making them the highest sea stacks in Britain.

The highest point in the archipelago, Conachair ('the beacon') at 430 metres (1,410.8 ft), is on Hirta, immediately north of the village. In the southeast is Oiseval ('east fell'), which reaches 290 metres (951.4 ft), and Mullach Mòr ('big hill summit') 361 metres (1,185 ft) is due west of Conachair. Ruival ('red fell') 137 metres (449.5 ft) and Mullach Bi ('pillar summit') 358 metres (1,174.5 ft) dominate the western cliffs. Boreray reaches 384 metres (1,259.8 ft) and Soay 378 metres (1,240.2 ft). The extraordinary Stac an Armin reaches 196 metres (643 ft), and Stac Lee, 172 metres (564.3 ft), making them the highest sea stacks in Britain.

In modern times, St Kilda's only settlement was at Village Bay ( or ) on Hirta. Gleann Mòr on the north coast of Hirta and Boreray also contain the remains of earlier habitations. The sea approach to Hirta into Village Bay suggests a small settlement flanked by high rolling hills in a semicircle behind it. This is misleading. The whole north face of Conachair is a vertical cliff up to 427 metres (1,400.9 ft) high, falling sheer into the sea and constituting the highest sea cliff in the UK.

Indeed, the archipelago is the site of many of the most spectacular sea cliffs in the British Isles. Baxter and Crumley (1988) suggest that St Kilda: "...is a mad, imperfect God's hoard of all unnecessary lavish landscape luxuries he ever devised in his madness. These he has scattered at random in Atlantic isolation 100 miles (160.9 km) from the corrupting influences of the mainland, 40 miles (64.4 km) west of the westmost Western Isles. He has kept for himself only the best pieces and woven around them a plot as evidence of his madness."

Although 64 kilometres (39.8 mi) from the nearest land, St Kilda is visible from as far as the summit ridges of the Skye

Although 64 kilometres (39.8 mi) from the nearest land, St Kilda is visible from as far as the summit ridges of the Skye

Cuillin

, some 129 kilometres (80.2 mi) distant. The climate is oceanic with high rainfall, 1400 millimetres (55.1 in), and high humidity. Temperatures are generally cool, averaging 5.6 °C (42.1 °F) in January and 11.8 °C (53.2 °F) in July. The prevailing winds, especially strong in winter, are southerly and southwesterly. Wind speeds average 13 kilometres per hour (8.1 mph) approximately 85 percent of the time and more than 24 kilometres per hour (14.9 mph) more than 30 percent of the time. Gale force winds occur less than 2 percent of the time in any one year, but gusts of 185 kilometres per hour (115 mph) and more occur regularly on the high tops, and speeds of 209 kilometres per hour (129.9 mph) have occasionally been recorded near sea level. The tidal range is 2.9 metres (9.5 ft), and ocean swells of 5 metres (16 ft) frequently occur, which can make landings difficult or impossible at any time of year. However, the oceanic location protects the islands from snow, which lies for only about a dozen days per year.

The archipelago's remote location and oceanic climate are matched in the UK only by a few smaller outlying islands such as the Flannan Isles

, North Rona

, Sula Sgeir

, and the Bishop's Isles

at the southern edge of the Outer Hebrides. Administratively, St Kilda was part of the parish of Harris in the traditional county of Inverness-shire

. Today it is incorporated in the Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

(Western Isles) unitary authority

.

On the very inaccessible island of Soay there were sheep of a unique type, which lived as feral

On the very inaccessible island of Soay there were sheep of a unique type, which lived as feral

animals and belonged to the owner of the islands, not to the islanders. These Soay sheep

are believed to be remnants of the earliest sheep kept in Europe in the Neolithic

, and are small, short-tailed, usually brown with white bellies, and have naturally moulting fleeces. About 200 Soay sheep remain on Soay itself, but soon after the evacuation a second feral population of them was established on Hirta, which at that time had no sheep; these now number between 600 and 1,700. A few Soays have been exported to form breeding populations in other parts of the world, where they are valued for their hardiness, small size and unusual appearance. On Hirta and Soay, the sheep prefer the Plantago

pastures, which grow well in locations exposed to sea spray

and include red fescue (Festuca rubra

), Sea Plantain (Plantago maritima

) and Sea Pink (Armeria maritima

).

The St Kildans kept up to 2,000 of a different type of sheep on the islands of Hirta and Boreray. These were a Hebridean variety of the Scottish Dunface

, a primitive sheep probably similar to those kept throughout Britain during the Iron Age

. At the time of the evacuation all the islanders' sheep were removed from Hirta, but those on Boreray were left to become feral, and these are now regarded as a breed in their own right, the Boreray

. The Boreray is one of the rarest British sheep, and is one of the few remaining descendants of the Dunface (although some Scottish Blackface

blood was introduced in the nineteenth century).

Yet another kind of sheep has an association with St Kilda. This is a black, often four-horned breed previously known as the "St Kilda" sheep, but now known as the Hebridean

. In fact it was probably derived from Dunface sheep from elsewhere in the Hebrides, including North Uist. It was widely kept in parks in mainland Scotland and England in the 19th century; it is not known why the St Kilda name became attached to it.

St Kilda is a breeding ground for many important seabird

St Kilda is a breeding ground for many important seabird

species. The world's largest colony of Northern Gannet

s, totalling 30,000 pairs, amount to 24 percent of the global population. There are 49,000 breeding pairs of Leach's Petrels

, up to 90 percent of the European population; 136,000 pairs of Atlantic Puffin

s, about 30 percent of the UK total breeding population, and 67,000 Northern Fulmar

pairs, about 13 percent of the UK total. Dùn is home to the largest colony of Fulmars in Britain. Prior to 1828, St Kilda was their only UK breeding ground, but they have since spread and established colonies elsewhere, such as Fowlsheugh

. The last Great Auk

(Pinguinus impennis) seen in Britain was killed on Stac an Armin in July 1840. Unusual behaviour by St Kilda's Bonxies

was recorded in 2007 during research into recent falls in the Leach's Petrel population. Using night vision gear, ecologists observed the skuas hunting petrels at night, a remarkable strategy for a seabird.

Two wild animal taxa are unique to St Kilda: the St Kilda Wren

(Troglodytes troglodytes hirtensis), which is a subspecies of the Winter Wren

, and a subspecies of Wood Mouse

known as the St Kilda Field Mouse

(Apodemus sylvaticus hirtensis). A third taxon endemic to St Kilda, a subspecies of House Mouse

known as the St Kilda House Mouse

(Mus musculus muralis), vanished completely after the departure of human inhabitants, as it was strictly associated with settlements and buildings. It had a number of traits in common with a sub-species (Mus musculus mykinessiensis) found on Mykines island in the Faroe Islands

. The Grey Seal (Halichoerus grypus) now breeds on Hirta but did not do so before the 1930 evacuation.

The archipelago's isolation has resulted in a lack of biodiversity

. Only 58 species of butterfly

and moth

occur on the islands, compared to 367 recorded on the Western Isles. Plant life is heavily influenced by the salt spray, strong winds and acidic peat

y soils. No trees grow on the archipelago, although there are more than 130 different flowering plants, 162 species of fungi and 160 bryophyte

s. Several rarities exist amongst the 194 lichen

species. Kelp

thrives in the surrounding seas, which contain a diversity of unusual marine invertebrates.

The beach at Village Bay is unusual in that its short stretch of summer sand recedes in winter, exposing the large boulders on which it rests. A survey of the beach in 1953 found only a single resident species, the crustacean isopod Eurydice pulchra.

Most modern commentators feel that the predominant theme of life on St Kilda was isolation. When Martin Martin

Most modern commentators feel that the predominant theme of life on St Kilda was isolation. When Martin Martin

visited the islands in 1697, the only means of making the journey was by open boat, which could take several days and nights of rowing and sailing across the ocean and was next to impossible in autumn and winter. In all seasons, waves up to 12 metres (39.4 ft) high lash the beach of Village Bay, and even on calmer days landing on the slippery rocks can be hazardous. Separated by distance and weather, the natives knew little of mainland and international politics. After the Battle of Culloden

in 1746, it was rumoured that Prince Charles Edward Stuart and some of his senior Jacobite

aides had escaped to St Kilda. An expedition was launched, and in due course British soldiers were ferried ashore to Hirta. They found a deserted village, as the St Kildans, fearing pirates, had fled to caves to the west. When the St Kildans were persuaded to come down, the soldiers discovered that the isolated natives knew nothing of the prince and had never heard of King George II

either.

Even in the late 19th century, the islanders could communicate with the rest of the world only by lighting a bonfire on the summit of Conachair and hoping a passing ship might see it, or by using the "St Kilda mailboat". The mailboat was the invention of John Sands

, who visited in 1877. During his stay, a shipwreck left nine Austrian sailors marooned there, and by February supplies were running low. Sands attached a message to a lifebuoy salvaged from the Peti Dubrovacki and threw it into the sea. Nine days later it was picked up in Birsay

, Orkney and a rescue was arranged. The St Kildans, building on this idea, fashioned a piece of wood into the shape of a boat, attached it to a bladder made of sheepskin, and placed in it a small bottle or tin containing a message. Launched when the wind came from the north-west, two-thirds of the messages were later found on the west coast of Scotland or, less conveniently, in Norway.

Another significant feature of St Kildan life was the diet. The islanders kept sheep and a few cattle and were able to grow a limited amount of food crops such as barley

Another significant feature of St Kildan life was the diet. The islanders kept sheep and a few cattle and were able to grow a limited amount of food crops such as barley

and potatoes on the better-drained land in Village Bay, and in many ways the islands can be seen as large mixed farm. Samuel Johnson

reported that in the 18th century sheep's milk was made "into small cheeses" by the St Kildans. They generally eschewed fishing because of the heavy seas and unpredictable weather. The mainstay of their food supplies was the profusion of island birds, especially gannet and fulmar. These they harvested as eggs and young birds and ate both fresh and cured. Adult puffins were also caught by the use of fowling

rods. However, this feature of island life came at a price. When Henry Brougham

visited in 1799 he noted that "the air is infected by a stench almost insupportable – a compound of rotten fish, filth of all sorts and stinking seafowl". An excavation of the Taigh an t-Sithiche (the "house of the faeries" – see below) in 1877 by Sands unearthed the remains of gannet, sheep, cattle and limpets amidst various stone tools. The building is between 1,700 and 2,500 years old, which suggests that the St Kildan diet had changed little over the millennia. Indeed the tools were recognised by the St Kildans, who could put names to them as similar devices were still in use.

These fowling activities involved considerable skills in climbing, especially on the precipitous sea stacks. An important island tradition involved the 'Mistress Stone', a door-shaped opening in the rocks north-west of Ruival over-hanging a gully. Young men of the island had to undertake a ritual there to prove themselves on the crags and worthy of taking a wife. Martin Martin wrote:

These fowling activities involved considerable skills in climbing, especially on the precipitous sea stacks. An important island tradition involved the 'Mistress Stone', a door-shaped opening in the rocks north-west of Ruival over-hanging a gully. Young men of the island had to undertake a ritual there to prove themselves on the crags and worthy of taking a wife. Martin Martin wrote:

Another important aspect of St Kildan life was the daily 'Parliament'. This was a meeting held in the street every morning after prayers and attended by all the adult males during the course of which they would decide upon the day's activities. No one led the meeting, and all had the right to speak. According to Steel (1988), "Discussion frequently spread discord, but never in recorded history were feuds so bitter as to bring about a permanent division in the community". This notion of a free society influenced Enric Miralles'

vision for the new Scottish Parliament Building

, opened in October 2004.

Whatever the privations, the St Kildans were fortunate in some respects, for their isolation spared them some of the evils of life elsewhere. Martin noted in 1697 that the citizens seemed "happier than the generality of mankind as being almost the only people in the world who feel the sweetness of true liberty", and in the 19th century their health and well being was contrasted favourably with conditions elsewhere in the Hebrides

. Theirs was not a utopian society; the islanders had ingenious wooden locks for their property, and financial penalties were exacted for misdemeanours. Nonetheless, no resident St Kildan is known to have fought in a war, and in four centuries of history, no serious crime committed by an islander was recorded there.

settlement emerged—shards of pottery of the Hebridean ware style, found to the east of the village. The subsequent discovery of a quarry for stone tools on Mullach Sgar above Village Bay led to finds of numerous stone hoe-blades, grinders and Skaill knives in the Village Bay cleitean—unique stone storage buildings (see below). These tools are also probably of Neolithic origin.

mentioned 'the isle of Irte, which is agreed to be under the Circius and on the margins of the world'. The islands were historically part of the domain of the MacLeods

of Harris, whose steward was responsible for the collection of rents in kind and other duties. The first detailed report of a visit to the islands dates from 1549, when Donald Munro

suggested that: "The inhabitants thereof ar simple poor people, scarce learnit in aney religion, but M’Cloyd of Herray, his stewart, or he quhom he deputs in sic office, sailes anes in the zear ther at midsummer, with some chaplaine to baptize bairnes ther."

The chaplain's best efforts notwithstanding, the islanders' isolation and dependence on the bounty of the natural world meant their philosophy bore as much relationship to Druidism as it did to Christianity

until the arrival of Rev. John MacDonald in 1822. Macauley (1764) reported the existence of five druidic altars, including a large circle of stones fixed perpendicularly in the ground near the Stallir House on Boreray

.

Coll MacDonald of Colonsay

raided Hirta in 1615, removing 30 sheep and a quantity of barley. Thereafter, the islands developed a reputation for abundance. At the time of Martin's visit in 1697 the population was 180 and the steward travelled with a "company" of up to 60 persons to which he "elected the most 'meagre' among his friends in the neighbouring islands, to that number and took them periodically to St. Kilda to enjoy the nourishing and plentiful, if primitive, fare of the island, and so be restored to their wonted health and strength."

Visiting ships in the 18th century brought cholera

Visiting ships in the 18th century brought cholera

and smallpox

. In 1727, the loss of life was so high that too few residents remained to man the boats, and new families were brought in from Harris to replace them. By 1758 the population had risen to 88 and reached just under 100 by the end of the century. This figure remained fairly constant from the 18th century until 1851, when 36 islanders emigrated to Australia on board the Priscilla, a loss from which the island never fully recovered. The emigration was in part a response to the laird

's closure of the church and manse for several years during the Disruption

that created the Free Church of Scotland

.

One factor in the decline was thus the influence of religion. A missionary called Alexander Buchan came to St Kilda in 1705, but despite his long stay, the idea of organised religion did not take hold. This changed when Rev. John MacDonald, the 'Apostle of the North', arrived in 1822. He set about his mission with zeal, preaching 13 lengthy sermons during his first 11 days. He returned regularly and fundraised on behalf of the St Kildans, although privately he was appalled by their lack of religious knowledge. The islanders took to him with enthusiasm and wept when he left for the last time eight years later. His successor, who arrived on 3 July 1830, was Rev. Neil Mackenzie, a resident Church of Scotland

minister who greatly improved the conditions of the inhabitants. He reorganised island agriculture, was instrumental in the rebuilding of the village (see below) and supervised the building of a new church and manse. With help from the Gaelic School Society, MacKenzie and his wife introduced formal education to Hirta, beginning a daily school to teach reading, writing and arithmetic and a Sunday school

for religious education.

Mackenzie left in 1844, and although he had achieved a great deal, the weakness of the St Kildans' dependence on external authority was exposed in 1865 with the arrival of Rev. John Mackay. Despite their fondness for Mackenzie, who stayed in the Church of Scotland

, the St Kildans 'came out' in favour of the new Free Church during the Disruption. Mackay, the new Free Church minister, placed an uncommon emphasis on religious observance. He introduced a routine of three two-to-three-hour services on Sunday at which attendance was effectively compulsory. One visitor noted in 1875 that: "The Sabbath was a day of intolerable gloom. At the clink of the bell the whole flock hurry to Church with sorrowful looks and eyes bent upon the ground. It is considered sinful to look to the right or to the left." Time spent in religious gatherings interfered seriously with the practical routines of the island. Old ladies and children who made noise in church were lectured at length and warned of dire punishments in the afterworld. During a period of food shortages on the island, a relief vessel arrived on a Saturday, but the minister said that the islanders had to spend the day preparing for church on the Sabbath, and it was Monday before supplies were landed. Children were forbidden to play games and required to carry a Bible wherever they went. Mackay remained minister on St Kilda for 24 years.

Time spent in religious gatherings interfered seriously with the practical routines of the island. Old ladies and children who made noise in church were lectured at length and warned of dire punishments in the afterworld. During a period of food shortages on the island, a relief vessel arrived on a Saturday, but the minister said that the islanders had to spend the day preparing for church on the Sabbath, and it was Monday before supplies were landed. Children were forbidden to play games and required to carry a Bible wherever they went. Mackay remained minister on St Kilda for 24 years.

Tourism had a different but similarly destabilising impact on St Kilda. During the 19th century, steamers began to visit Hirta, enabling the islanders to earn money from the sale of tweeds

and birds' eggs but at the expense of their self-esteem as the tourists regarded them as curiosities. The boats brought other previously unknown diseases, especially tetanus infantum

, which resulted in infant mortality rates as high as 80 percent during the late 19th century. The cnatan na gall or boat-cough, an illness that struck after the arrival of a ship to Hirta, became a regular feature of life.

By the turn of the 20th century, formal schooling had again become a feature of the islands, and in 1906 the church was extended to make a schoolhouse. The children all now learned English and their native Gaelic. Improved midwifery

skills, denied to the island by Reverend Mackay, reduced the problems of childhood tetanus. From the 1880s, trawlers fishing the north Atlantic made regular visits, bringing additional trade. Talk of an evacuation occurred in 1875 during MacKay's period of tenure, but despite occasional food shortages and a flu epidemic in 1913, the population was stable at between 75 and 80, and no obvious sign existed that within a few years the millennia-old occupation of the island was to end.

Early in World War I

Early in World War I

the Royal Navy

erected a signal station on Hirta, and daily communications with the mainland were established for the first time in St Kilda's history. In a belated response, a German submarine arrived in Village Bay on the morning of 15 May 1918 and, after issuing a warning, started shelling the island. Seventy-two shells were fired, and the wireless station was destroyed. The manse, church and jetty storehouse were damaged, but no loss of life occurred. One eyewitness recalled: "It wasn't what you would call a bad submarine because it could have blowed every house down because they were all in a row there. He only wanted Admiralty property. One lamb was killed... all the cattle ran from one side of the island to the other when they heard the shots."

As a result of this attack, a 4-inch Mark III QF gun

was erected on a promontory overlooking Village Bay, but it never saw military use. Of greater long-term significance to the islanders were the introduction of regular contact with the outside world and the slow development of a money-based economy. This made life easier for the St Kildans but also made them less self-reliant. Both were factors in the evacuation of the island little more than a decade later.

Numerous factors led to the evacuation of St Kilda. The islands' inhabitants had existed for centuries in relative isolation until tourism and the presence of the military in World War I induced the islanders to seek alternatives to privations they routinely suffered. The changes made to the island by visitors in the nineteenth century disconnected the islanders from the way of life that had allowed their forebears to survive in this unique environment. Despite construction of a small jetty in 1902, the islands remained at the weather's mercy.

Numerous factors led to the evacuation of St Kilda. The islands' inhabitants had existed for centuries in relative isolation until tourism and the presence of the military in World War I induced the islanders to seek alternatives to privations they routinely suffered. The changes made to the island by visitors in the nineteenth century disconnected the islanders from the way of life that had allowed their forebears to survive in this unique environment. Despite construction of a small jetty in 1902, the islands remained at the weather's mercy.

After World War I most of the young men left the island, and the population fell from 73 in 1920 to 37 in 1928. After the death of four men from influenza

in 1926 there was a succession of crop failures in the 1920s. Investigations by Aberdeen University into the soil where crops had been grown have shown that there had been contamination by lead

and other pollutants, caused by the use of seabird carcasses and peat ash in the manure used on the village fields. This occurred over a lengthy period of time as manuring practices became more intensive and may have been a factor in the evacuation. The last straw came with the death from appendicitis

of a young woman, Mary Gillies, in January 1930. On 29 August 1930, the remaining 36 inhabitants were removed to Morvern

on the Scottish mainland at their own request.

The islands were purchased in 1931 by Lord Dumfries

(later 5th Marquess of Bute

), from Sir Reginald MacLeod. For the next 26 years the island experienced quietude, save for the occasional summer visit from tourists or a returning St Kildan family.

The islands took no active part in World War II

The islands took no active part in World War II

, during which they were completely abandoned, but three aircraft crash sites remain from that period. A Beaufighter

LX798 based at Port Ellen on Islay

crashed into Conachair within 100 metres (328 ft) of the summit on the night of 3–4 June 1943. A year later, just before midnight on 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day, a Sunderland

flying boat

ML858 was wrecked at the head of Gleann Mòr. A small plaque in the kirk is dedicated to those who died in this accident. A Wellington

bomber

crashed on the south coast of Soay in 1942 or 1943. Not until 1978 was any formal attempt made to investigate the wreck, and its identity has not been absolutely determined. Amongst the wreckage, a Royal Canadian Air Force

cap badge was discovered, which suggests it may have been HX448 of 7 OTU which went missing on a navigation exercise on 28 September 1942. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the Wellington is LA995 of 303 FTU which was lost on 23 February 1943.

In 1955 the British government decided to incorporate St Kilda into a missile tracking range based in Benbecula

, where test firings and flights are carried out. Thus in 1957 St Kilda became permanently inhabited once again. A variety of military buildings and masts have since been erected, including the island's first licensed premises, the 'Puff Inn'. The Ministry of Defence

(MOD) leases St Kilda from the National Trust for Scotland for a nominal fee. The main island of Hirta is still occupied year-round by a small number of civilians employed by defence contractor QinetiQ

working in the military base on a monthly rotation. In 2009 the MOD announced that it was considering closing down its missile testing ranges in the Western Isles, potentially leaving the Hirta base unmanned.

provided they accepted the offer within six months. After much soul-searching, the Executive Committee agreed to do so in January 1957. The slow renovation and conservation of the village began, much of it undertaken by summer volunteer work parties. In addition, scientific research began on the feral Soay sheep population and other aspects of the natural environment. In 1957 the area was designated a National Nature Reserve

.

In 1986 the islands became the first place in Scotland to be inscribed as a UNESCO

World Heritage Site

, for its terrestrial natural features. In 2004, the WHS was extended to include a large amount of the surrounding marine features as well as the islands themselves. In 2005 St Kilda became one of only two dozen global locations to be awarded mixed World Heritage Status for both 'natural' and 'cultural' significance. The islands share this honour with internationally important sites such as Machu Picchu

in Peru

, Mount Athos

in Greece and the Ukhahlamba/Drakensberg Park

in South Africa.

The St Kilda World Heritage Site covers a total area of 24201.4 hectares (59,802.9 acre) including the land and sea. The land area is 854.6 hectares (2,111.8 acre).

St Kilda is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, a National Scenic Area

, a Site of Special Scientific Interest

, and a European Union Special Protection Area

. Visiting yachts may find shelter in Village Bay, but those wishing to land are told to contact the National Trust for Scotland in advance. Concern exists about the introduction of non-native animal and plant species into such a fragile environment.

St Kilda's marine environment of underwater caves, arches and chasms offers a challenging but superlative diving experience. Such is the power of the North Atlantic swell that the effects of the waves can be detected 70 metres (230 ft) below sea level. In 2008 the National Trust for Scotland received the support of Scotland’s Minister for Environment

, Michael Russell for their plan to ensure no rats come ashore from the Spinningdale, a UK-registered/Spanish-owned fishing vessel grounded on Hirta. There was concern that bird life on the island could be seriously affected. Fortunately, potential contaminants from the vessel including fuel, oils, bait and stores were successfully removed by Dutch salvage company Mammoet

before the bird breeding season in early April.

Similar stories of a female warrior who hunted the now submerged land between the Outer Hebrides and St Kilda are reported from Harris. The structure's forecourt is akin to the other 'horned structures' in the immediate area, but like Martin's "Amazon" its original purpose is the stuff of legend rather than archaeological fact.

Much more is known of the hundreds of unique cleitean that decorate the archipelago. These dome-shaped structures are constructed of flat boulders with a cap of turf on the top. This enables the wind to pass through the cavities in the wall but keeps the rain out. They were used for storing peat, nets, grain

, preserved flesh and eggs, manure, hay and as a shelter for lambs in winter. The date of origin of this St Kildan invention is unknown, but they were in continuous use from prehistoric times until the 1930 evacuation. More than 1,200 ruined or intact cleitean remain on Hirta and a further 170 on the neighbouring islands. House no. 16 in the modern village has an early Christian stone cross built into the front wall, which may date from the 7th century.

A medieval village lay near Tobar Childa, about 350 metres (1,148.3 ft) from the shore, at the foot of the slopes of Conachair. The oldest building is an underground passage with two small annexes called Taigh an t-Sithiche (house of the faeries) which dates to between 500 BC and 300 AD. The St Kildans believed it was a house or hiding place, although a more recent theory suggests that it was an ice house.

A medieval village lay near Tobar Childa, about 350 metres (1,148.3 ft) from the shore, at the foot of the slopes of Conachair. The oldest building is an underground passage with two small annexes called Taigh an t-Sithiche (house of the faeries) which dates to between 500 BC and 300 AD. The St Kildans believed it was a house or hiding place, although a more recent theory suggests that it was an ice house.

Extensive ruins of field walls and cleitean and the remnants of a medieval 'house' with a beehive-shaped annex remain. Nearby is the 'Bull's House', a roofless rectangular structure in which the island's bull was kept during winter. Tobar Childa itself is supplied by two springs that lie just outside the Head Wall that was constructed around the Village to prevent sheep and cattle gaining access to the cultivated areas within its boundary. There were 25 to 30 houses altogether. Most were black house

s of typical Hebridean design, but some older buildings were made of corbelled stone and turfed rather than thatched. The turf was used to prevent ingress of wind and rain, and the older "beehive" buildings resembled green hillocks rather than dwellings.

for Devon

. Appalled by the primitive conditions, he made a donation that led to the construction of a completely new settlement of 30 new black house

s. Several of the new dwellings were damaged by a severe gale in October 1860, and repairs were sufficient only to make them suitable for use as byres. According to Alasdair MacGregor

's analysis of the settlement, the sixteen modern, zinc-roofed cottages amidst the black houses and new Factor's

house seen in most photographs of the natives were constructed around 1862.

These houses were made of dry stone

, had thick walls and were roofed with turf. Each typically had only one tiny window and a small aperture for letting out smoke from the peat fire that burnt in the middle of the room. As a result, the interiors were blackened by soot. The cattle occupied one end of the house in winter, and once a year the straw from the floor was stripped out and spread on the ground.

One of the more poignant ruins on Hirta is the site of 'Lady Grange's House'. Lady Grange

One of the more poignant ruins on Hirta is the site of 'Lady Grange's House'. Lady Grange

had been married to the Jacobite

sympathiser James Erskine of Grange for 25 years when he decided that she might have overheard too many of his treasonable plottings. He had her kidnapped and secretly confined in Edinburgh

for six months. From there she was sent to the Monach Isles, where she lived in isolation for two years. She was then taken to Hirta from 1734 to 1740, which she described as "a vile neasty, stinking poor isle". After a failed rescue attempt, she was removed by Erskine to the Isle of Skye, where she died. The 'house' is a large cleit in the Village meadows.

Boswell

and Johnson

discussed the subject during their 1773 tour of the Hebrides. Boswell wrote: "After dinner to-day, we talked of the extraordinary fact of Lady Grange’s being sent to St Kilda, and confined there for several years, without any means of relief. Dr Johnson said, if M’Leod would let it be known that he had such a place for naughty ladies, he might make it a very profitable island."

In the 1860s unsuccessful attempts were made to improve the landing area by blasting rocks. A small jetty

In the 1860s unsuccessful attempts were made to improve the landing area by blasting rocks. A small jetty

was erected in 1877, but it was washed away in a storm two years later. In 1883 representations to the Napier Commission

suggested the building of a replacement, but it was 1901 before the Congested Districts Board

provided an engineer to enable one to be completed the following year. Nearby on the shore line are some huge boulders which were known throughout the Highlands and Islands

in the 19th century as Doirneagan Hirt, Hirta's pebbles.

At one time, three churches stood on Hirta. Christ Church, in the site of the graveyard at the centre of the village, was in use in 1697 and was the largest, but this thatched-roof structure was too small to hold the entire population, and most of the congregation had to gather in the churchyard during services. St Brendan's Church lay over a kilometre away on the slopes of Ruival, and St Columba's at the west end of the village street, but little is left of these buildings. A new kirk

and manse

were erected at the east end of the village in 1830 and a Factor's

house in 1860.

Dùn

Dùn

means "fort", and there is but a single ruined wall of a structure said to have been built in the far-distant past by the Fir Bolg

. The only "habitation" is Sean Taigh (old house), a natural cavern sometimes used as a shelter by the St Kildans when they were tending the sheep or catching birds.

Soay has a primitive hut known as Taigh Dugan (Dugan's house). This is little more than an excavated hole under a huge stone with two rude walls on the sides. The story of its creation relates to two sheep-stealing brothers from Lewis

who came to St Kilda only to cause further trouble. Dugan was exiled to Soay, where he died; the other, called Fearchar Mòr, was sent to Stac an Armin, where he found life so intolerable he cast himself into the sea.

Boreray boasts the Cleitean MacPhàidein, a "cleit village" of three small bothies used on a regular basis during fowling expeditions. Here too are the ruins of Taigh Stallar (the steward's house), which was similar to the Amazon's house in Gleann Mòr although somewhat larger, and which had six bed spaces. The local tradition was that it was built by the "Man of the Rocks", who led a rebellion against the landlord's steward. It may be an example of an Iron Age

wheelhouse

and the associated remains of an agricultural field system were discovered in 2011. As a result of a smallpox outbreak on Hirta in 1724, three men and eight boys were marooned on Boreray until the following May. No fewer than 78 storage cleitean exist on Stac an Armin

and a small bothy

. Incredibly, a small bothy exists on the precipitous Stac Lee

too, also used by fowlers.

The steamship company running a service between Glasgow

The steamship company running a service between Glasgow

and St Kilda commissioned a short (18 minute) silent movie, St Kilda, Britain's Loneliest Isle

. Released in 1928, it shows some scenes in the lives of the island’s inhabitants. In 1937, after reading of the St Kilda evacuation, Michael Powell

made the film The Edge of the World

about the dangers of island depopulation. It was shot, however, not on St Kilda but on Foula

, one of the Shetland Islands

. The writer Dorothy Dunnett

wrote a short story, "The Proving Climb", set on St Kilda; it was published in 1973 in the anthology Scottish Short Stories.

In 1982, the noted Scottish filmmaker and theatre director Bill Bryden

made the Channel 4

-funded film Ill Fares The Land about the last years of St Kilda. It is not currently on commercial release.

The fictional island of Laerg, which features in the 1962 novel Atlantic Fury by Hammond Innes

, is closely based on Hirta.

The Scottish folk rock

band Runrig

recorded a song called Edge Of The World on the album "The Big Wheel

", which dwells on the islanders' isolated existence and how "the man from St Kilda went over the cliff on a winter's day". The Scottish folk music

singer/song-writer Brian McNeill

wrote about one of St. Kilda's prodigal sons, a restless fellow named Ewan Gillies, who left St. Kilda to seek his fortune by prospecting for gold first in Australia and later California. The song recounts fortunes won and lost, his return to the island, concluding with his inability to stay. Entitled "Ewan and the Gold", it was published on the album Back O' The North Wind in 1991 and is the subject of McNeill's audio-visual presentation about the Scottish diaspora

.

In a 2005 poll

of Radio Times

readers, St Kilda was named as the ninth greatest natural wonder in the British Isles. In 2007 an opera

in Scots Gaelic called St Kilda: A European Opera about the story of the islands received funding from the Scottish Government. It was performed simultaneously at six venues in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Scotland over the summer solstice of 2007. As part of the lasting legacy, this production left a long-term time lapse camera on Hirta. Britain's Lost World, a three-part BBC

documentary series about St Kilda began broadcasting on 19 June 2008.

Stamps were issued by the Post Office

depicting St. Kilda in 1986 and 2004. St Kilda was also commemorated on a new series of banknotes issued by the Clydesdale Bank

in 2009; an image based on a historical photograph of residents appeared on the reverse of an issue of £5 notes.

Also in 2009 Pròiseact nan Ealan

, the Gaelic Arts Agency announced plans to commemorate the evacuation on 29 August, (the 79th anniversary) including an exhibition in Kelvingrove Art Gallery. Comhairle nan Eilean Siar are also planning a feasibility study for a new visitor centre to tell the story of St Kilda, although they have specifically ruled out using Hirta as a location.

Archipelago

An archipelago , sometimes called an island group, is a chain or cluster of islands. The word archipelago is derived from the Greek ἄρχι- – arkhi- and πέλαγος – pélagos through the Italian arcipelago...

64 kilometres (39.8 mi) west-northwest of North Uist

North Uist

North Uist is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.-Geography:North Uist is the tenth largest Scottish island and the thirteenth largest island surrounding Great Britain. It has an area of , slightly smaller than South Uist. North Uist is connected by causeways to Benbecula...

in the North Atlantic Ocean. It contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta

Hirta

Hirta is the largest island in the St Kilda archipelago, on the western edge of Scotland. The name "Hiort" and "Hirta" have also been applied to the entire archipelago.-Geography:...

, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom and three other islands (Dùn

Dùn, St Kilda

Dùn is an island in the St Kilda archipelago. It is nearly a mile long. Its name simply means "fort" in Scottish Gaelic , but the fort itself has been lost - old maps show it on Gob an Dùin , which is at the seaward end.Almost joined to Hirta at Ruiaval, the two islands are separated by Caolas an...

, Soay

Soay, St Kilda

Soay is an uninhabited islet in the St Kilda archipelago, Scotland. The island is part of the St Kilda World Heritage Site and home to a primitive breed of sheep...

and Boreray

Boreray, St Kilda

Boreray is an uninhabited island in the St Kilda archipelago in the North Atlantic.-Geography:Boreray lies about 66 km west-north-west of North Uist. It covers about , and reaches a height of at Mullach an Eilein....

), were also used for grazing and seabird hunting. The islands are administratively a part of the Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar is the local government council for Na h-Eileanan Siar council area of Scotland.It is the only local council in Scotland to have a Gaelic-only name...

local authority area.

St Kilda may have been permanently inhabited for at least two millennia, the population probably never exceeding 180 (and certainly no more than 100 after 1851). The entire population was evacuated

Emergency evacuation

Emergency evacuation is the immediate and rapid movement of people away from the threat or actual occurrence of a hazard. Examples range from the small scale evacuation of a building due to a bomb threat or fire to the large scale evacuation of a district because of a flood, bombardment or...

from Hirta (the only inhabited island) in 1930. Currently, the only year-round residents are defence personnel although a variety of conservation workers, volunteers and scientists spend time there in the summer months.

The origin of the name St Kilda is a matter of conjecture. The islands' human heritage includes numerous unique architectural features from the historic and prehistoric periods, although the earliest written records of island life date from the Late Middle Ages

Scotland in the Late Middle Ages

Scotland in the late Middle Ages established its independence from England under figures including William Wallace in the late 13th century and Robert Bruce in the 14th century...

. The medieval village on Hirta was rebuilt in the 19th century, but the influences of religious zeal, illnesses brought by increased external contacts through tourism, and the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

all contributed to the island's evacuation in 1930. The story of St Kilda has attracted artistic interpretations, including an opera

Opera

Opera is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a dramatic work combining text and musical score, usually in a theatrical setting. Opera incorporates many of the elements of spoken theatre, such as acting, scenery, and costumes and sometimes includes dance...

.

The entire archipelago is owned by the National Trust for Scotland

National Trust for Scotland

The National Trust for Scotland for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, commonly known as the National Trust for Scotland describes itself as the conservation charity that protects and promotes Scotland's natural and cultural heritage for present and future generations to...

. It became one of Scotland's five World Heritage Site

World Heritage Site

A UNESCO World Heritage Site is a place that is listed by the UNESCO as of special cultural or physical significance...

s in 1986 and is one of the few in the world to hold joint status for its natural and cultural qualities. Two different early sheep types have survived on these remote islands, the Soay

Soay sheep

The Soay sheep is a primitive breed of domestic sheep descended from a population of feral sheep on the island of Soay in the St. Kilda Archipelago, about from the Western Isles of Scotland...

, a Neolithic type, and the Boreray

Boreray (sheep)

The Boreray is a breed of sheep originating on the St Kilda archipelago off the west coast of Scotland and surviving as a feral animal on one of the islands, Boreray. It is primarily a meat breed...

, an Iron Age type. The islands are a breeding ground for many important seabird

Seabird

Seabirds are birds that have adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same environmental problems and feeding niches have resulted in similar adaptations...

species including Northern Gannet

Northern Gannet

The Northern Gannet is a seabird and is the largest member of the gannet family, Sulidae.- Description :Young birds are dark brown in their first year, and gradually acquire more white in subsequent seasons until they reach maturity after five years.Adults are long, weigh and have a wingspan...

s, Atlantic Puffin

Atlantic Puffin

The Atlantic Puffin is a seabird species in the auk family. It is a pelagic bird that feeds primarily by diving for fish, but also eats other sea creatures, such as squid and crustaceans. Its most obvious characteristic during the breeding season is its brightly coloured bill...

s, and Northern Fulmar

Northern Fulmar

The Northern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis, Fulmar, or Arctic Fulmar is a highly abundant sea bird found primarily in subarctic regions of the north Atlantic and north Pacific oceans. Fulmars come in one of two color morphs: a light one which is almost entirely white, and a dark one which is...

s. The St Kilda Wren

St Kilda Wren

The St Kilda Wren, Troglodytes troglodytes hirtensis, is a small passerine bird in the wren family. It is a distinctive subspecies of the Winter Wren endemic to the islands of the isolated St Kilda archipelago, in the Atlantic Ocean 64 km west of the Outer Hebrides, Scotland...

and St Kilda Field Mouse

St Kilda Field Mouse

The St Kilda Field Mouse is a subspecies of wood mouse endemic to the Scottish isles of St Kilda. It is generally twice as heavy as mainland field mice and has longer hair and a longer tail. It is mostly grey in colour and, though hard to find, very common.It is not to be confused with the St...

are endemic subspecies

Subspecies

Subspecies in biological classification, is either a taxonomic rank subordinate to species, ora taxonomic unit in that rank . A subspecies cannot be recognized in isolation: a species will either be recognized as having no subspecies at all or two or more, never just one...

. Parties of volunteers work on the islands in the summer to restore the many ruined buildings that the native St Kildans left behind. They share the island with a small military base

Military base

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and operations. In general, a military base provides accommodations for one or more units, but it may also be used as a...

established in 1957.

Origin of names

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

is known by the name of Kilda, and various theories have been proposed for the word's origin, which dates from the late 16th century. Haswell-Smith (2004) notes that the full name St Kilda first appears on a Dutch map dated 1666, and that it may have been derived from Norse sunt kelda ("sweet wellwater") or from a mistaken Dutch assumption that the spring Tobar Childa was dedicated to a saint. (Tobar Childa is a tautological placename, consisting of the Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic language

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish, and thus descends ultimately from Primitive Irish....

and Norse

Old Norse

Old Norse is a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and inhabitants of their overseas settlements during the Viking Age, until about 1300....

words for well, i.e., "well well"). Martin Martin

Martin Martin

Martin Martin was a Scottish writer best known for his work A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland . This book is particularly noted for its information on the St Kilda archipelago...

, who visited in 1697, believed that the name "is taken from one Kilder, who lived here; and from him the large well Toubir-Kilda has also its name".

Old Norse

Old Norse is a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and inhabitants of their overseas settlements during the Viking Age, until about 1300....

name for the spring on Hirta, Childa, and states that a 1588 map identifies the archipelago as Kilda. He also speculates that it may refer to the Culdee

Culdee

Céli Dé or Culdees were originally members of ascetic Christian monastic and eremitical communities of Ireland, Scotland and England in the Middle Ages. The term is used of St. John the Apostle, of a missioner from abroad recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters at the year 806, and of Óengus...

s, anchorite

Anchorite

Anchorite denotes someone who, for religious reasons, withdraws from secular society so as to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, ascetic, and—circumstances permitting—Eucharist-focused life...

s who may have brought Christianity to the island, or be a corruption of the Gaelic name for the main island of the group, since the islanders tended to pronounce r as l, and thus habitually referred to the island as Hilta. Steel (1988) adds weight to the idea, noting that the islanders pronounced the H with a "somewhat guttural quality", making the sound they used for Hirta "almost" Kilta. Similary, St Kilda speakers interviewed by the School of Scottish Studies

School of Scottish Studies

The School of Scottish Studies was founded in 1951, and is affiliated to the University of Edinburgh. It holds an archive of over 9000 field recordings of traditional music, song and other lore, housed in George Square, Edinburgh...

in the 1960s show individual speakers using t-initial forms, leniting

Lenition

In linguistics, lenition is a kind of sound change that alters consonants, making them "weaker" in some way. The word lenition itself means "softening" or "weakening" . Lenition can happen both synchronically and diachronically...

to /h/, e.g. ann an t-Hirte (an̪ˠən̪ˠ 'tʰʲrˠt̪ə) and gu Hirte (kə 'hirˠʃt̪ə).

Maclean (1972) further suggests that the Dutch may have simply made a cartographical error, and confused Hirta with Skildar, the old name for Haskeir

Haskeir

Not to be confused with Hyskeir or HeskeirHaskeir , also known as Great Haskeir is a remote, exposed and uninhabited island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It lies west north west of North Uist. to the south west lie the skerries of Haskeir Eagach made up of a colonnade of five rock stacks...

island much nearer the main Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

archipelago. Quine (2000) hypothesises that the name is derived from a series of cartographical errors, starting with the use of the Old Iceland

Iceland

Iceland , described as the Republic of Iceland, is a Nordic and European island country in the North Atlantic Ocean, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Iceland also refers to the main island of the country, which contains almost all the population and almost all the land area. The country has a population...

ic Skildir ("shields") and appearing as Skildar on a map by Nicholas de Nicolay (1583). This, so the hypothesis goes, was transcribed in error by Lucas J. Waghenaer in his 1592 charts without the trailing r and with a period after the S, creating S.Kilda. This was in turn assumed to stand for a saint by others, creating the form that has been used for several centuries, St Kilda.

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | Am Baile | |

| Pronunciation: | əm ˈpalə | |

| Scots Gaelic: | An Lag bhon Tuath | |

| Pronunciation: | ə ˈlˠ̪ak vɔn̪ˠ ˈt̪ʰuə | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Bàgh a’ Bhaile | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈpaːɣ ə valə |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | cleitean | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈkʰlehtʲan |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Cleitean MacPhàidein | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈkʰlehtʲan maxkˈfaːtʲɛɲ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Cnatan nan Gall | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈkʰɾãht̪an nəŋ ˈkaulˠ̪ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Conachair | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈkʰɔnəxəɾʲ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Dòirneagan Hiort | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈt̪ɔːrˠɲakən ˈhirˠʃt̪ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Dùn | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈt̪uːn |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Gleann Mòr | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈklaun̪ˠ ˈmoːɾ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Ì Àrd | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈiː ˈaːrˠt̪ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Loch Hiort | |

| Pronunciation: | lˠ̪ɔxˈhirˠʃt̪ | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Mullach Bìgh | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈmulˠ̪əx ˈpiː |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Mullach Mòr | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈmulˠ̪əx ˈmoːɾ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Oiseabhal | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈɔʃəvəlˠ̪ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Ruadhbhal | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈrˠuəvəlˠ̪ |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Seann Taigh | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈʃaun̪ˠ ˈt̪ʰɤj |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Taigh an t-Sithiche | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈt̪ʰɤj əɲ ˈtʰʲi.ɪçə |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Taigh Dugain | |

| Pronunciation: | t̪ʰɤjˈt̪ukɛɲ | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Taigh na Banaghaisgich | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈt̪ʰɤj nə ˈpanaɣaʃkʲɪç |

||

| Scots Gaelic: | Taigh Stallair | |

| Pronunciation: |ˈt̪ʰɤj ˈs̪t̪alˠ̪əɾʲ |

||

The origin of Hirta, which long pre-dates St Kilda, is similarly open to interpretation. Martin (1703) avers that "Hirta is taken from the Irish Ier, which in that language signifies west". Maclean offers several options, including an (unspecified) Celtic word meaning "gloom" or "death", or the Scots Gaelic h-Iar-Tìr ("westland"). Drawing on an Icelandic saga

Icelanders' sagas

The Sagas of Icelanders —many of which are also known as family sagas—are prose histories mostly describing events that took place in Iceland in the 10th and early 11th centuries, during the so-called Saga Age. They are the best-known specimens of Icelandic literature.The Icelanders'...

describing an early 13th-century voyage to Ireland that mentions a visit to the islands of Hirtir, he speculates that the shape of Hirta resembles a stag

STAG

STAG: A Test of Love is a reality TV show hosted by Tommy Habeeb. Each episode profiles an engaged couple a week or two before their wedding. The cameras then follow the groom on his bachelor party...

, Hirtir ("stags" in Norse). Steel (1998) quotes the view of Reverend Neil Mackenzie, who lived there from 1829 to 1844, that the name is derived from the Gaelic Ì Àrd ("high island"), and a further possibility that it is from the Norse Hirt ("shepherd"). In a similar vein, Murray (1966) speculates that the Norse Hirðö, pronounced 'Hirtha' ("herd island"), may be the origin. All the names of and on the islands are fully discussed by Coates (1990).

Geography

Tertiary

The Tertiary is a deprecated term for a geologic period 65 million to 2.6 million years ago. The Tertiary covered the time span between the superseded Secondary period and the Quaternary...

igneous formations of granites and gabbro

Gabbro

Gabbro refers to a large group of dark, coarse-grained, intrusive mafic igneous rocks chemically equivalent to basalt. The rocks are plutonic, formed when molten magma is trapped beneath the Earth's surface and cools into a crystalline mass....

, heavily weathered by the elements. The archipelago represents the remnants of a long-extinct ring volcano rising from a seabed plateau approximately 40 metres (131.2 ft) below sea level.

At 670 hectares (1,655.6 acre) in extent, Hirta

Hirta

Hirta is the largest island in the St Kilda archipelago, on the western edge of Scotland. The name "Hiort" and "Hirta" have also been applied to the entire archipelago.-Geography:...

is the largest island in the group and comprises more than 78% of the land area of the archipelago. Next in size are Soay (English: "sheep island") at 99 hectares (244.6 acre) and Boreray ('the fortified isle'), which measures 86 hectares (212.5 acre). Soay is 0.5 kilometre (0.310686368324903 mi) north-west of Hirta, Boreray 6 kilometres (4 mi) to the northeast. Smaller islet

Islet

An islet is a very small island.- Types :As suggested by its origin as islette, an Old French diminutive of "isle", use of the term implies small size, but little attention is given to drawing an upper limit on its applicability....

s and stacks

Stack (geology)

A stack is a geological landform consisting of a steep and often vertical column or columns of rock in the sea near a coast, isolated by erosion. Stacks are formed through processes of coastal geomorphology, which are entirely natural. Time, wind and water are the only factors involved in the...

in the group include Stac an Armin

Stac an Armin

Stac an Armin , based on the proper Scottish Gaelic spelling , is a sea stack in the St Kilda archipelago. It is 196 metres tall, qualifying it as a Marilyn...

('warrior's stack'), Stac Lee

Stac Lee

Stac Lee is a sea stack in the St Kilda group, Scotland. An island Marilyn, it is home to part of the world's largest colony of Northern Gannet.-Geography and geology:Martin Martin called the island "Stac-Ly"; other sources call it "Stac Lii."...

('grey stack') and Stac Levenish

Stac Levenish

Stac Levenish or Stac Leibhinis is a sea stack in the St Kilda archipelago in Scotland. Lying 2½ km off Village Bay on Hirta, it is part of the rim of an extinct volcano that includes Dùn, Ruaival and Mullach Sgar.The stack is high...

('stream' or 'torrent'). The island of Dùn ('fort'), which protects Village Bay from the prevailing southwesterly winds, was at one time joined to Hirta by a natural arch. MacLean (1972) suggests that the arch was broken when struck by a galleon

Galleon

A galleon was a large, multi-decked sailing ship used primarily by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries. Whether used for war or commerce, they were generally armed with the demi-culverin type of cannon.-Etymology:...

fleeing the defeat of the Spanish Armada

Spanish Armada

This article refers to the Battle of Gravelines, for the modern navy of Spain, see Spanish NavyThe Spanish Armada was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia in 1588, with the intention of overthrowing Elizabeth I of England to stop English...

, but other sources, such as Mitchell (1992) and Fleming (2005), provide the more credible (if less romantic) explanation that the arch was simply swept away by one of the many fierce storms that batter the islands every winter.

In modern times, St Kilda's only settlement was at Village Bay ( or ) on Hirta. Gleann Mòr on the north coast of Hirta and Boreray also contain the remains of earlier habitations. The sea approach to Hirta into Village Bay suggests a small settlement flanked by high rolling hills in a semicircle behind it. This is misleading. The whole north face of Conachair is a vertical cliff up to 427 metres (1,400.9 ft) high, falling sheer into the sea and constituting the highest sea cliff in the UK.

Indeed, the archipelago is the site of many of the most spectacular sea cliffs in the British Isles. Baxter and Crumley (1988) suggest that St Kilda: "...is a mad, imperfect God's hoard of all unnecessary lavish landscape luxuries he ever devised in his madness. These he has scattered at random in Atlantic isolation 100 miles (160.9 km) from the corrupting influences of the mainland, 40 miles (64.4 km) west of the westmost Western Isles. He has kept for himself only the best pieces and woven around them a plot as evidence of his madness."

Skye

Skye or the Isle of Skye is the largest and most northerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate out from a mountainous centre dominated by the Cuillin hills...

Cuillin

Cuillin

This article is about the Cuillin of Skye. See Rùm for the Cuillin of Rùm.The Cuillin are a range of rocky mountains located on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. The true Cuillin are also known as the Black Cuillin to distinguish them from the Red Hills across Glen Sligachan...

, some 129 kilometres (80.2 mi) distant. The climate is oceanic with high rainfall, 1400 millimetres (55.1 in), and high humidity. Temperatures are generally cool, averaging 5.6 °C (42.1 °F) in January and 11.8 °C (53.2 °F) in July. The prevailing winds, especially strong in winter, are southerly and southwesterly. Wind speeds average 13 kilometres per hour (8.1 mph) approximately 85 percent of the time and more than 24 kilometres per hour (14.9 mph) more than 30 percent of the time. Gale force winds occur less than 2 percent of the time in any one year, but gusts of 185 kilometres per hour (115 mph) and more occur regularly on the high tops, and speeds of 209 kilometres per hour (129.9 mph) have occasionally been recorded near sea level. The tidal range is 2.9 metres (9.5 ft), and ocean swells of 5 metres (16 ft) frequently occur, which can make landings difficult or impossible at any time of year. However, the oceanic location protects the islands from snow, which lies for only about a dozen days per year.

The archipelago's remote location and oceanic climate are matched in the UK only by a few smaller outlying islands such as the Flannan Isles

Flannan Isles

Designed by David Alan Stevenson, the tower was constructed for the Northern Lighthouse Board between 1895 and 1899 and is located near the highest point on Eilean Mòr. Construction was undertaken by George Lawson of Rutherglen at a cost of £6,914 inclusive of the building of the landing places,...

, North Rona

North Rona

Rona is a remote Scottish island in the North Atlantic. Rona is often referred to as North Rona in order to distinguish it from South Rona . It has an area of and a maximum height of...

, Sula Sgeir

Sula Sgeir

Sula Sgeir is a small, uninhabited Scottish island in the North Atlantic, west of North Rona...

, and the Bishop's Isles

Barra Isles

The Barra Isles, also known as the Bishop's Isles as they were historically owned by the Bishop of the Isles, are a small archipelago of islands in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. They lie south of the island of Barra, for which they are named. The group consists of nine islands, and numerous...

at the southern edge of the Outer Hebrides. Administratively, St Kilda was part of the parish of Harris in the traditional county of Inverness-shire

Inverness-shire

The County of Inverness or Inverness-shire was a general purpose county of Scotland, with the burgh of Inverness as the county town, until 1975, when, under the Local Government Act 1973, the county area was divided between the two-tier Highland region and the unitary Western Isles. The Highland...

. Today it is incorporated in the Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar is the local government council for Na h-Eileanan Siar council area of Scotland.It is the only local council in Scotland to have a Gaelic-only name...

(Western Isles) unitary authority

Unitary authority

A unitary authority is a type of local authority that has a single tier and is responsible for all local government functions within its area or performs additional functions which elsewhere in the relevant country are usually performed by national government or a higher level of sub-national...

.

Sheep

Feral

A feral organism is one that has changed from being domesticated to being wild or untamed. In the case of plants it is a movement from cultivated to uncultivated or controlled to volunteer. The introduction of feral animals or plants to their non-native regions, like any introduced species, may...

animals and belonged to the owner of the islands, not to the islanders. These Soay sheep

Soay sheep

The Soay sheep is a primitive breed of domestic sheep descended from a population of feral sheep on the island of Soay in the St. Kilda Archipelago, about from the Western Isles of Scotland...

are believed to be remnants of the earliest sheep kept in Europe in the Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

, and are small, short-tailed, usually brown with white bellies, and have naturally moulting fleeces. About 200 Soay sheep remain on Soay itself, but soon after the evacuation a second feral population of them was established on Hirta, which at that time had no sheep; these now number between 600 and 1,700. A few Soays have been exported to form breeding populations in other parts of the world, where they are valued for their hardiness, small size and unusual appearance. On Hirta and Soay, the sheep prefer the Plantago

Plantago

Plantago is a genus of about 200 species of small, inconspicuous plants commonly called plantains. They share this name with the very dissimilar plantain, a kind of banana. Most are herbaceous plants, though a few are subshrubs growing to 60 cm tall. The leaves are sessile, but have a narrow...

pastures, which grow well in locations exposed to sea spray

Sea spray

Sea spray is a spray of water that forms when ocean waves crash.-Make up:As a result, salt spray contains a high concentration of mineral salts, particularly chloride anions.-Effects:...

and include red fescue (Festuca rubra

Festuca rubra

Festuca rubra is a species of grass known by the common name red fescue. It is found worldwide and can tolerate many habitats and climates; it generally needs full sun to thrive...

), Sea Plantain (Plantago maritima

Plantago maritima

Plantago maritima is a species of Plantago, family Plantaginaceae. It has a subcosmopolitan distribution in temperate and Arctic regions, native to most of Europe, northwest Africa, northern and central Asia, northern North America, and southern South America...

) and Sea Pink (Armeria maritima

Armeria maritima

Armeria maritima is the botanical name for a species of flowering plant.It is a popular garden flower, known by several common names, including thrift, sea thrift, and sea pink. The plant has been distributed worldwide as a garden and cut flower...

).

The St Kildans kept up to 2,000 of a different type of sheep on the islands of Hirta and Boreray. These were a Hebridean variety of the Scottish Dunface

Scottish Dunface

The Scottish Dunface, Old Scottish Short-wool, Scottish Whiteface or Scottish Tanface was a type of sheep from Scotland. It was one of the Northern European short-tailed sheep group, and it was probably similar to the sheep kept throughout the British Isles in the Iron Age...

, a primitive sheep probably similar to those kept throughout Britain during the Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

. At the time of the evacuation all the islanders' sheep were removed from Hirta, but those on Boreray were left to become feral, and these are now regarded as a breed in their own right, the Boreray

Boreray (sheep)

The Boreray is a breed of sheep originating on the St Kilda archipelago off the west coast of Scotland and surviving as a feral animal on one of the islands, Boreray. It is primarily a meat breed...

. The Boreray is one of the rarest British sheep, and is one of the few remaining descendants of the Dunface (although some Scottish Blackface

Scottish Blackface