History of Cornell University

Encyclopedia

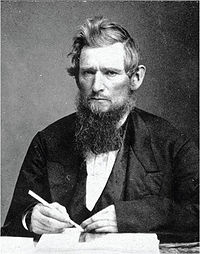

Andrew Dickson White

Andrew Dickson White was a U.S. diplomat, historian, and educator, who was the co-founder of Cornell University.-Family and personal life:...

of Syracuse

Syracuse, New York

Syracuse is a city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States, the largest U.S. city with the name "Syracuse", and the fifth most populous city in the state. At the 2010 census, the city population was 145,170, and its metropolitan area had a population of 742,603...

and Ezra Cornell

Ezra Cornell

Ezra Cornell was an American businessman and education administrator. He was a founder of Western Union and a co-founder of Cornell University...

of Ithaca

Ithaca, New York

The city of Ithaca, is a city in upstate New York and the county seat of Tompkins County, as well as the largest community in the Ithaca-Tompkins County metropolitan area...

, met in the New York State Senate

New York State Senate

The New York State Senate is one of two houses in the New York State Legislature and has members each elected to two-year terms. There are no limits on the number of terms one may serve...

in January 1864. Together, they established Cornell University

Cornell University

Cornell University is an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, United States. It is a private land-grant university, receiving annual funding from the State of New York for certain educational missions...

in Ithaca

Ithaca, New York

The city of Ithaca, is a city in upstate New York and the county seat of Tompkins County, as well as the largest community in the Ithaca-Tompkins County metropolitan area...

, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, in 1865. The university was initially funded by Ezra Cornell's $400,000 endowment and by New York's 989920 acres (4,006.1 km²) allotment of the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862

Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts are United States statutes that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges, including the Morrill Act of 1862 and the Morrill Act of 1890 -Passage of original bill:...

.

However, even before Ezra Cornell and Andrew White met in the New York Senate, each had separate plans and dreams that would draw them toward their collaboration in founding Cornell: White believed in the need for a great university for the nation that would take a radical new approach to education; and Cornell, who had great respect for education and philanthropy, desired to use his money "to do the greatest good." Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

's signing of Vermont

Vermont

Vermont is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state ranks 43rd in land area, , and 45th in total area. Its population according to the 2010 census, 630,337, is the second smallest in the country, larger only than Wyoming. It is the only New England...

Senator Justin Morrill

Justin Smith Morrill

Justin Smith Morrill was a Representative and a Senator from Vermont, most widely remembered today for the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act that established federal funding for establishing many of the United States' public colleges and universities...

's Land Grant Act into law was also critical to the formation of many universities

University

A university is an institution of higher education and research, which grants academic degrees in a variety of subjects. A university is an organisation that provides both undergraduate education and postgraduate education...

in the post-Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

era, including Cornell.

Founders

Military tactics

Military tactics, the science and art of organizing an army or an air force, are the techniques for using weapons or military units in combination for engaging and defeating an enemy in battle. Changes in philosophy and technology over time have been reflected in changes to military tactics. In...

, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

and the mechanic arts

Mechanic arts

Mechanic arts is an obsolete and archaic term. In the medieval period, the Seven Mechanical Arts were intended as a complement to the Seven Liberal Arts, and consisted of weaving, blacksmithing, war, navigation, agriculture, hunting, medicine, and the ars theatrica. In the 19th century it referred...

". Yet, their eventual partnership seemed unlikely. Although both valued egalitarianism, science, and education, they had come from two very different backgrounds.

Ezra Cornell, a self-made businessman and austere, pragmatic telegraph mogul, made his fortune on the Western Union Telegraph Company

Western Union

The Western Union Company is a financial services and communications company based in the United States. Its North American headquarters is in Englewood, Colorado. Up until 2006, Western Union was the best-known U.S...

stock he received during the consolidation that led to its formation. Cornell, who had been poor for most of his life, suddenly found himself looking for ways that he could do the greatest good for with his money — he wrote, "My greatest care now is how to spend this large income to do the greatest good to those who are properly dependent on me, to the poor and to posterity." Cornell's self education and hard work would lead him to the conclusion that the greatest end for his philanthropy was in the need of colleges for the teaching of practical pursuits such as agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

, the applied science

Applied science

Applied science is the application of scientific knowledge transferred into a physical environment. Examples include testing a theoretical model through the use of formal science or solving a practical problem through the use of natural science....

s, veterinary medicine

Veterinary medicine

Veterinary Medicine is the branch of science that deals with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease, disorder and injury in non-human animals...

and engineering

Engineering

Engineering is the discipline, art, skill and profession of acquiring and applying scientific, mathematical, economic, social, and practical knowledge, in order to design and build structures, machines, devices, systems, materials and processes that safely realize improvements to the lives of...

and in finding opportunities for the poor to attain such an education.

Geneva College

Geneva College is a Christian liberal arts college in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, United States, north of Pittsburgh. Founded in 1848, in Northwood, Ohio, the college moved to its present location in 1880, where it continues to educate a student body of about 1400 traditional undergraduates in...

(later known as Hobart

Hobart and William Smith Colleges

Hobart and William Smith Colleges, located in Geneva, New York, are together a liberal arts college offering Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science and Master of Arts in Teaching degrees. In athletics, however, the two schools compete with separate teams, known as the Hobart Statesmen and the...

), a small Episcopal college. At Geneva, White would read about the great colleges at Oxford University and at the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

; this appears to be his first inspiration for "dreaming of a university worthy of the commonwealth [New York] and of the nation"; this dream would become a lifelong goal of White's. After a year at Geneva, White convinced his father to send him to Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

. For White, Yale was a great improvement over Geneva, but he found that even at one of the country's great universities there was "too much reciting by rote and too little real intercourse".

In the late 1850s, while White served as a professor of history at the University of Michigan

University of Michigan

The University of Michigan is a public research university located in Ann Arbor, Michigan in the United States. It is the state's oldest university and the flagship campus of the University of Michigan...

, he continued to develop his thoughts on a great American university. He was influenced by both the curriculum, which was more liberal than at the Eastern universities, and by the administration of the university as a secular institution.

Conception

White had been duly impressed by a bill introduced by Cornell in one of his first actions as a state senator: the incorporation of a large public library for Ithaca for which Cornell had donated $100,000. White was struck by not only his generosity, but also "his breadth of mind". He wrote:

The most striking sign of this was his mode of forming a board of trustees; for, instead of the usual effort to tie up the organization forever in some sect, party or clique, he had named the best men of his town — his political opponents as well as his friends; and had added to them the pastors of all the principal churches, Catholic and Protestant.

Yet, Cornell and White soon found themselves on opposite sides of a battle that would in the end lead to the creation of Cornell University. In 1863, the legislature had granted the proceeds of the land grant to the People's College in Havana Montour Falls, with conditions that would need to be met within a certain time frame. Because the Morrill Act set a five-year limit on each state identifying a land grant college, and it seemed unlikely that the People's College would meet its conditions, the legislature was ready to select a different school. Initially, Cornell, as a member of the Board of Trustees of the New York State Agricultural College at Ovid, wanted half the grant to go to that school. However, White "vigorously opposed this bill, on the ground that the educational resources of the state were already too much dispersed". He felt that the grant would be most effective if it were used to establish or strengthen a comprehensive university.

Still working to send part of the grant to the Agricultural College, on September 25, 1864, in Rochester, New York

Rochester, New York

Rochester is a city in Monroe County, New York, south of Lake Ontario in the United States. Known as The World's Image Centre, it was also once known as The Flour City, and more recently as The Flower City...

, Cornell announced his offer to donate $300,000 (soon thereafter increased to $500,000) if part of the land grant could be secured and the trustees moved the college to Ithaca. White did not relent; however, he said he would support a similar measure that did not split up the grant. Thus began the collaboration between Ezra Cornell and Andrew D. White that became Cornell University.

Establishment

The bill was modified at least twice in attempts to attain the votes necessary for passage. In the first change, the People's College was given three months to meet certain conditions for which it would receive the land grant under the 1863 law. The second came from a Methodist faction, which wanted a share of the grant for Genesee College

Genesee College

Genesee College was a college founded in 1832 as the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary by the Methodist Episcopal Church. It was located in Lima, NY and eventually relocated to Syracuse, NY, becoming Syracuse University.-Genesee Wesleyan Seminary:...

. They agreed to a quid-pro quo donation of $25,000 from Ezra Cornell in exchange for their support. Cornell insisted the bargain be written into the bill. The bill was signed into law by Governor Reuben E. Fenton

Reuben Fenton

Reuben Eaton Fenton was an American merchant and politician from New York.-Life:He was the son of a farmer. He was elected a colonel of the New York State Militia in 1840. He became a lumber merchant, and entered politics as a Democrat...

on April 27, 1865. On July 27, the People's College lost its claim to the land grant funds, and the building of Cornell University began.

From 1865 to 1868, the year the university opened, Ezra Cornell and Andrew D. White worked in tireless collaboration to build their university. Ezra Cornell oversaw the construction of the university's first buildings, starting with Morrill Hall, and spent time investing the federal land scrip in western lands for the university that would eventually net millions of dollars, while Andrew D. White, who was unanimously elected the first President of Cornell University by the Board of Trustees on November 21, 1866, began making plans for the administrative and educational policies of the university. To this end, he traveled to France, Germany and England "to visit model institutions, to buy books and equipment, to collect professors". White returned from Europe to be inaugurated as Cornell's president in 1868, and he remained leader of Cornell until his retirement from the presidency in 1885.

Opening

On the occasion, Ezra Cornell delivered a brief speech. He said, "I hope we have laid the foundation of an institution which shall combine practical with liberal education. ... I believe we have made the beginning of an institution which will prove highly beneficial to the poor young men and the poor young women of our country." His speech included another statement which later became the school's motto, "I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study.

Two other Ezra Cornell-founded, Ithaca institutions played a role in the rapid opening of the university. The Cornell Library, a public library in downtown Ithaca which opened in 1866, served as a classroom and library for the first students. Also Cascadilla Hall, which was constructed in 1866 as a water cure

Water cure (therapy)

A water cure in the therapeutic sense is a course of medical treatment by hydrotherapy.-Overview:In the mid-19th century there was a popular revival of the water cure in Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

sanitarium, served at the university's first dormitory.

Henry W. Sage

Henry W. Sage was a wealthy New York State businessman, philanthropist, and early benefactor and trustee of Cornell University....

to build such a dormitory. During the construction of Sage College

Sage Residential College

Sage Hall was built in 1875 at Cornell University's Ithaca, New York campus. It was originally designed to be a residential building, however, currently it houses the Johnson Graduate School of Management...

(now home to the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management

Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management

The Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management is the graduate business school of Cornell University, a private Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York. It was founded in 1946 and renamed in 1984 after Samuel Curtis Johnson, founder of S.C...

as Sage Hall) and after its opening in 1875, the admittance of women to Cornell continued to increase.

Significant departures from the standard curriculum were made at Cornell under the leadership of Andrew D. White. In 1868, Cornell introduced the elective system, under which students were free to choose their own course of study. Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

would make a similar change in 1872, soon after the inauguration of Charles W. Eliot

Charles William Eliot

Charles William Eliot was an American academic who was selected as Harvard's president in 1869. He transformed the provincial college into the preeminent American research university...

in 1869.

It was the success of the egalitarian ideals of the newly-established Cornell, a uniquely American institution, that would help drive some of the changes seen at other universities throughout the next few decades, and would lead educational historian Frederick Rudolph to write:

Andrew D. White, its first president, and Ezra Cornell, who gave it his name, turned out to be the developers of the first American university and therefore the agents of revolutionary curricular reform.

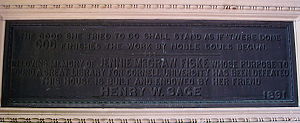

Library

In a traditional sense, a library is a large collection of books, and can refer to the place in which the collection is housed. Today, the term can refer to any collection, including digital sources, resources, and services...

was opened. Known today as Uris Library, it was the result of a gift from Henry W. Sage

Henry W. Sage

Henry W. Sage was a wealthy New York State businessman, philanthropist, and early benefactor and trustee of Cornell University....

in memory of Jennie McGraw

Jennie McGraw

Jennie McGraw was born in Dryden, NY in 1840 and died in Ithaca, New York on September 30, 1881. She was the daughter of John McGraw, millionaire philanthropist to Cornell. After her father's death in 1877, McGraw inherited his large fortune...

. In her will

Will (law)

A will or testament is a legal declaration by which a person, the testator, names one or more persons to manage his/her estate and provides for the transfer of his/her property at death...

, she left $300,000 to her husband Willard Fiske

Willard Fiske

Daniel Willard Fiske was an American librarian and scholar, born on November 11, 1831, at Ellisburg, New York.Fiske studied at Cazenovia Seminary and started his collegiate studies at Hamilton College in 1847. He joined the Psi Upsilon but was suspended for a student prank at the end of his...

, $550,000 to her brother Joseph and his children, $200,000 to Cornell for a library, $50,000 for construction of McGraw Hall, $40,000 for a student hospital, and the remainder to the University for whatever use it saw fit. However, the University's charter limited its property holdings to $3,000,000, and Cornell could not accept the full amount of McGraw's gift. When Fiske realized that the university had failed to inform him of this restriction, he launched a legal assault to re-acquire the money, known as The Great Will Case. The United States Supreme Court eventually affirmed the judgment of the New York Court of Appeals

New York Court of Appeals

The New York Court of Appeals is the highest court in the U.S. state of New York. The Court of Appeals consists of seven judges: the Chief Judge and six associate judges who are appointed by the Governor to 14-year terms...

that Cornell could not receive the estate on May 19, 1890, with Justice Samuel Blatchford

Samuel Blatchford

Samuel Blatchford was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from April 3, 1882 until his death.-Early life:...

giving the majority opinion. However, Sage then donated $500,000 to build the library instead.

Coeducation

In 1870, Cornell admitted its first female students, making it the first coeducational school among what came to be known as the Ivy League. However, the admission of female students was limited until the construction of Sage Hall to serve as a women's dormitory in 1872. The requirement that women (at least freshman women) must live in dormitories, which started in 1884, served to constrain female student admissions until 1970, when Cornell dropped its freshman dorm residency requirement. As a result, the academic admission standards for women in each college were typically higher than the corresponding standards for men. In general, women have been over-represented in certain schools and under-represented in others. For example, the NYS College of Home Economics and the Cornell School of NursingCornell School of Nursing

The Cornell University School of Nursing was founded in 1877 as the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses, in New York, New York. As a part of New York Hospital, the school began its connection with Cornell University when Cornell's Medical College affiliated with New York Hospital in 1927...

historically drew a disproportionate number of women students, while the College of Engineering

Cornell University College of Engineering

The College of Engineering is a division of Cornell University that was founded in 1870 as the Sibley College of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanic Arts...

attracted fewer women.

Early in the history of the university, female students were separated from male students in many ways. For example, they had a separate entrance and lounges in Willard Straight Hall, a separate student government, and a separate page (edited by women) in the Cornell Daily Sun. The male students were required to take "drill" (a precursor to ROTC), but the women were exempt. One account of the history of coeducation at Cornell claims that in the very beginning, "[m]ale students were almost unanimously opposed to co-education, and vigorously protested the arrival of a group of 16 women, who promptly formed a women's club with a broom for their standard, and 'In hoc signo vinces

In hoc signo vinces

In hoc signo vinces is a Latin rendering of the Greek phrase "" en touto nika, and means "in this sign you will conquer"....

' as their motto." In the 1870s and 1880s, female Cornell students on campus were generally ignored by male students. Women did not have a formal role in the annual commencement ceremony until 1935, when the student government selected a woman to be Class Poet. In 1936, the Willard Straight Hall Board of Managers voted to allow women to eat in its cafeteria. Until the 1970s, male students resided in west campus dormitories while women were housed in the north campus. As of 2010, the only remaining women's dormitory is Balch Hall, due to a restriction in the gift that funded it. Lyon Hall (which for most of its history was a men-only dormintory), also currently disallows male residents on its lower floors. All other dormitories were converted to co-educational housing in the late 1970s.

The NYS College of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

The New York State College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University was founded in 1894. It was the first statutory college in New York. Before the creation of the college, instruction in veterinary medicine had been part of Cornell's curriculum since the university's founding...

was an early pioneer in educating women. Florence Kimball, the first woman in the United States to receive the DVM degree, graduated from Cornell in 1910. Seven of the first 11 women to become licensed veterinarians in this country were Cornell graduates. However, until the early 1980s, the Vet College limited the number of women in each entering class to four or less, regardless of female applicants' qualifications.

With the implementation of Title IX

Title IX

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 is a United States law, enacted on June 23, 1972, that amended Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 2002 it was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act, in honor of its principal author Congresswoman Mink, but is most...

in the mid-1970s, Cornell significantly expanded its athletic offerings for women. The Department of Physical Education and Athletics moved from having all women's activities housed in Helen Newman Hall to having men's and women's programs in all facilities.

Nonsectarianism and religion on campus

Up until the time of Cornell's founding, most prominent American colleges had ties to religious denominations. Cornell was founded as a non-sectarian school, but had to compete with church-sponsored institutions for gaining New York's land grant status. A.D. White noted in his inaugural address, "We will labor to make this a Christian institution, a sectarian institution may it never be." However, the university has made provision for voluntary religious observance on campus. Currently, the University Charter provides, "Persons of every religious denomination, or of no religious denomination, shall be equally eligible to all offices and appointments". Through the 20th century, the University Charter also required that a majority of trustees could not be of any single denomination. Sage ChapelSage Chapel

Sage Chapel is the non-denominational chapel on the campus of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York State and serves as the final resting place of the university's founders, Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, and their wives...

, a non-denominational house of worship opened in 1875. Since 1929, the Cornell United Religious Works (CURW) has been an umbrella organization for the campus chaplains sponsored by different denominations and faiths. Perhaps the most newsworthy of the chaplains was Daniel Berrigan

Daniel Berrigan

Daniel Berrigan, SJ is an American Catholic priest, peace activist, and poet. Daniel and his brother Philip were for a time on the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list for their involvement in antiwar protests during the Vietnam war....

who, while Assistant Director of CURW, became a national leader in protesting the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

. In 1971, the social activism aspects of CURW were spun off into a separate Center for Religion, Ethics and Social Policy (CRESP). In 2006, CRESP was reorganized as Cornell's Center for Transformative Action.

In the late 1950s, the National Council of Young Israel (NCYI) leased a house across the street from the university and established a Jewish living center and kosher dining hall. The Cornell Young Israel chapter became the Center for Jewish Living, and a new Foundation for Kosher Observance at Cornell, Inc. was established so that the university's dining department would operate both a kosher kitchen at the center as well as serving kosher food on the North Campus.

Since the 1870s, Cornell's system of fraternities and sororities grew to play a large role in student life, with many chapters becoming a part of national organizations. As of 1952, 19 fraternities had national restrictions based on race, religion or national origin, and of the 32 fraternities without such national requirements, 19 did not have "mixed" memberships. In response, the undergraduate Interfraternity Council passed a resolution condemning discrimination. In the 1960s, the Trustees established a Commission to examine the membership restrictions of those national organizations. Cornell adopted a policy that required fraternities and sororities affiliated with nationals that discriminated based on religion or race to either amend their national charters or quit the national organizations. As a result, a number of national Greek organizations dropped racial or religious barriers to their membership.

In 1873, the cornerstone of Sage Hall

Sage Residential College

Sage Hall was built in 1875 at Cornell University's Ithaca, New York campus. It was originally designed to be a residential building, however, currently it houses the Johnson Graduate School of Management...

was laid. This new hall was to house the Sage College for Women and thus to concretely establish Cornell University's coeducational status. Ezra Cornell wrote a letter for posterity—dated 15 May 1873—and sealed it into the cornerstone. No copies of the letter were made, and Cornell kept its contents a secret. However, he hinted at the theme of the letter during his speech at the dedication of Sage Hall, stating that "the letter deposited in the cornerstone addressed to the future man and woman, of which I have kept no copy, will relate to future generations the cause of the failure of this experiment, if it ever does fail, as I trust in God it never will."

Cornell historians largely assumed that the "experiment" to which Cornell referred was that of coeducation, given that Sage Hall was to be a women's dormitory and that coeducation was still a controversial issue at the time. However, when the letter was finally unearthed in 1997, its focus was revealed to be the university's nonsectarian status—a principle which had invited equal controversy in the 19th century, given that most universities of the time had specific religious affiliations. Cornell wrote:

Infrastructure innovations

Cornell was one of the first university campuses to use electricity to light the grounds from a water-powered dynamo in 1883. In 1888-89, Cornell installed a central steam distribution system encased in logs. This eventually grew to three district plants on the Engineering Quadrangle, behind the Arts College, and on the state campus (located in Beebe Hall). In 1904, the present hydroelectric plant was built in the Fall Creek gorge following the replacement in 1896 of Triphammer Dam slightly west of its original location. The plant takes water from Beebe Lake through a tunnel in the side of the gorge to power up to 1.9 megawatts of electricity. The plant continued to serve the campus's electric needs until 1970, when local utility rates placed a heavy economic penalty on independently generating electricity. The abandoned plant was vandalized in 1972, but renovated and placed back into service in 1981.In 1986-87, a cogeneration facility was added to the central heating plant to generate electricity from the plant's waste heat. A Cornell Combined Heat & Power Project, which was completed in December 2009, shifted the central heating plant from using coal to natural gas and enable the plant to generate all of the campus's non-peak electric requirements.

In the 1880s, a suspension bridge was built across Fall Creek to provide pedestrian access to the campus from the North. In 1913, Professors S.C. Hollister and William McGuire designed a new suspension bridge that is 138 ft (42.1 m), 3.5 in. above the water and 500 ft (152.4 m) downstream from the original. However, the second bridge was declared unsafe and closed August 1960 to be rebuilt with a replacement of the same design.

Cornell began operating a closed loop, central chilled water system for air conditioning and laboratory cooling in the 1963 using centralized mechanical chillers, rather than inefficient, building-specific air conditioners. In 2000, Cornell began operation of its Lake Source Cooling System

Deep lake water cooling

Deep lake water cooling uses cold water pumped from the bottom of a lake as a heat sink for climate control systems. Because heat pump efficiency improves as the heat sink gets colder, deep lake water cooling can reduce the electrical demands of large cooling systems where it is available...

which uses the cold water temperature at the bottom of Cayuga Lake

Cayuga Lake

Cayuga Lake is the longest of central New York's glacial Finger Lakes, and is the second largest in surface area and second largest in volume. It is just under 40 miles long. Its average width is 1.7 miles , and it is at its widest point near Aurora...

(approx 39 °F) to air condition the campus. The system was the first wide-scale use of lake source cooling in North America.

Giving and alumni involvement

The first endowed chair at Cornell was the Professorship of Hebrew and Oriental Literature and History donated by New York City financier Joseph SeligmanJoseph Seligman

Joseph Seligman was a prominent U.S. banker, and businessman. He has been described as a "robber baron". He was born in Baiersdorf, Germany, emigrating to the United States when he was 18. With his brothers, he started a bank, J. & W. Seligman & Co., with branches in New York, San Francisco, New...

in 1874, with the proviso that he (Seligman) would nominate the chairholder; and following his wishes, Dr. Felix Adler (Society for Ethical Culture), was appointed. After two years, Professor Adler was quietly let go. Seligman demanded an inquiry. On rebuffing Joseph Seligman in 1877, the Trustees established one of their guiding principles governing the receipt of gifts, "That in the future no Endowment of Professorships will be accepted by the (Cornell) University which deprives the Board of Trustees of the power to Select The persons who shall fill such professorships". The second was the Susan E. Linn Sage Professor of Ethics and Philosophy given in 1890 by Henry W. Sage

Henry W. Sage

Henry W. Sage was a wealthy New York State businessman, philanthropist, and early benefactor and trustee of Cornell University....

. Since then, 327 named professorships have been established, of which 43 are honorary and do not have endowments. The university's first endowed scholarship was established in 1892.

The original University charter adopted by the New York State legislature required that Cornell give scholarships from students in each legislative district to attend the University tuition-free. Although both Cornell and White believed this meant one scholarship, the legislature later argued that it meant one new freshman student per district each year, or four per district. This allowed students of diverse financial resources to attend the university from the start.

John McMullen, who was president of the Atlantic Gulf & Pacific Dredging Company, while not a Cornellian himself, bequeathed his estate to Cornell for engineering scholarships on the advice of a friend and Cornell alumnus. Instead of spending the bequest and its earnings on scholarships, Cornell's Trustees decided to invest those funds, and eventually sold the dredging company. The resulting fund is Cornell's largest single scholarship endowment. Since 1925, the fund has provided substantial assistance to more than 3,700 engineering students. (Cornell has received a number of unusual non-cash (in-kind) gifts over the years, including: Ezra Cornell's farm, the Cornell Aeronautical Laborary (see below), a copy of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, a Peruvian mummy, and the Ostrander elm trees.)

Before the university opened, the State Legislature amended Cornell's charter on April 24, 1867 to specify alumni elected trustees. However that provision did not become operative until there were at least 100 alumni in 1872. Cornell was one of the first Universities to elect trustees by direct election. (Harvard was probably the first to shift to direct election of its Board of Overseers by alumni in 1865.) Cornell's first female trustee was Martha Carey Thomas (class of 1877), who the alumni elected while she was serving as President of Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College is a women's liberal arts college located in Bryn Mawr, a community in Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania, ten miles west of Philadelphia. The name "Bryn Mawr" means "big hill" in Welsh....

.

In October 1890, Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-American industrialist, businessman, and entrepreneur who led the enormous expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century...

became a Cornell Trustee and quickly became aware of the lack of an adequate pension plans for Cornell faculty. His concern led to the formation in 1905 of what is now called Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America

TIAA-CREF

Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association – College Retirement Equities Fund is a Fortune 100 financial services organization that is the leading retirement provider for people who work in the academic, research, medical and cultural fields...

(TIAA). In October 2010, David A. Atkinson and his wife Patricia donated $80 million to fund a sustainability center, and the gift is currently the largest single gift to Cornell (ignoring inflation) and is the largest ever given to a university for sustainability

Sustainability

Sustainability is the capacity to endure. For humans, sustainability is the long-term maintenance of well being, which has environmental, economic, and social dimensions, and encompasses the concept of union, an interdependent relationship and mutual responsible position with all living and non...

research and faculty support.

Many alumni classes elected secretaries to maintain correspondence with classmates. In 1905, the Class Secretaries organized to form what is now called the Cornell Association of Class Officers, which meets annually to develop alumni class programs and assist in organizing reunions. The Cornell Alumni News is an independent, alumni-owned publication founded in 1899 It is owned and controlled by the Cornell Alumni Association, a separate nonprofit corporation and is now known as Cornell Alumni Magazine.

Support from New York State

Land-grant university

Land-grant universities are institutions of higher education in the United States designated by each state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890....

. It determined to convince the state to become a benefactor of the university, instead. In 1894, the state legislature voted to give financial support for the establishment of the New York State College of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

The New York State College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University was founded in 1894. It was the first statutory college in New York. Before the creation of the college, instruction in veterinary medicine had been part of Cornell's curriculum since the university's founding...

and to make annual appropriations for the college. This set the precedents of privately-controlled, state-supported statutory college

Statutory college

In American higher education, particular to the state of New York, a statutory college or contract college is a college or school that is a component of an independent, private university that has been designated by the state legislature to receive significant, ongoing public funding from the state...

s and cooperation between Cornell and the state. The annual state appropriations were later extended to agriculture, home economics, and following World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, industrial and labor relations.

In 1882, Cornell opened the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station

Agricultural experiment station

An agricultural experiment station is a research center that conducts scientific investigations to solve problems and suggest improvements in the food and agriculture industry...

in Geneva, New York

Geneva, New York

Geneva is a city in Ontario and Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York. The population was 13,617 at the 2000 census. Some claim it is named after the city and canton of Geneva in Switzerland. Others believe the name came from confusion over the letters in the word "Seneca" written in cursive...

, the sixth oldest institution of its kind in the United States. It made significant advances in scientific agriculture and for many years played an active role in agriculture law enforcement.

In 1900, a home economics curriculum was added to Cornell's Agriculture college. This was expanded to a separate state-supported school in 1919. The Home Economics School, in turn, began to develop classes in hotel administration in 1922, which spun off into a separate, endowed college in 1950.

In 1898, the New York State College of Forestry

New York State College of Forestry at Cornell

The New York State College of Forestry at Cornell was a statutory college established in 1898 at Cornell University to teach scientific forestry. The first four-year college of forestry in the country, it was defunded by the State of New York in 1903, over controversies involving the college's...

opened at Cornell, which was the first forestry college in North America. The College undertook to establish a 30000 acres (121.4 km²) demonstration forest in the Adirondacks, funded by New York State. However, the plans of the school's director Bernhard Fernow for the land drew criticism from neighbors living on Saranac Lake, Knollwood Club

Knollwood Club

Knollwood Club is an Adirondack Great Camp on Shingle Bay, Lower Saranac Lake, near the village of Saranac Lake, New York. It was built in 1899–1900 by William L. Coulter, who had previously created a major addition to Alfred G. Vanderbilt's Sagamore Camp...

, and Governor Benjamin B. Odell vetoed the 1903 appropriation for the school. In response, Cornell closed the school. By some reports, Cornell gained annual state funding of the College of Agriculture in exchange for closing the forestry college. Subsequently, in 1911, the State Legislature established a New York State College of Forestry

State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry

The State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry is an American specialized doctoral-granting institution located in the University Hill neighborhood of Syracuse, New York, immediately adjacent to Syracuse University...

at Syracuse University

Syracuse University

Syracuse University is a private research university located in Syracuse, New York, United States. Its roots can be traced back to Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1832, which also later founded Genesee College...

, and the remains of Cornell's program became the Department of Natural Resources in its Agriculture College in 1910. However, Cornell had contracted with the Brooklyn Cooperage Company to take the logs from the forest, and the People of the State of New York, Knollwood Club

Knollwood Club

Knollwood Club is an Adirondack Great Camp on Shingle Bay, Lower Saranac Lake, near the village of Saranac Lake, New York. It was built in 1899–1900 by William L. Coulter, who had previously created a major addition to Alfred G. Vanderbilt's Sagamore Camp...

members (People vs Brooklyn Cooperage Company and Cornell) sued to stop the destructive practices of Fernow even before the closing of the school. Cornell University lost the case in 1910 and on appeal in 1912. Cornell eventually established a research forest south of Ithaca, the Arnot Woods. When New York State later funded the construction of a Forestry building for the Agriculture school, Cornell named it Fernow Hall.

In 1914, the US Department of Agriculture began to fund cooperative extension service

Cooperative extension service

The Cooperative Extension Service, also known as the Extension Service of the USDA, is a non-formal educational program implemented in the United States designed to help people use research-based knowledge to improve their lives. The service is provided by the state's designated land-grant...

s through the land grant college of each state, and Cornell expanded its impact by sending agents to spread knowledge in each county of New York State. Although Syracuse had started awarding forestry degrees at this point, Cornell's extension agents covered all of home economics and agriculture, including forestry.

In 1945, the New York State Legislature founded the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell

Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations

The New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations is an industrial relations school at Cornell University, an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, USA...

, in response to requests from organized labor and Democratic leaders. The school quickly gained national stature when U.S. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins , born Fannie Coralie Perkins, was the U.S. Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945, and the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. As a loyal supporter of her friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, she helped pull the labor movement into the New Deal coalition...

, who was the first female US Cabinet member and served longer than anyone else as Secretary of Labor (12 years), joined the ILR faculty. Since agricultural interests were mostly affiliated with the Republicans, Cornell enjoyed bi-partisan support following World War II.

In 1948, the Legislature placed all state-funded higher education into the new State University of New York (SUNY). Cornell's four statutory college

Statutory college

In American higher education, particular to the state of New York, a statutory college or contract college is a college or school that is a component of an independent, private university that has been designated by the state legislature to receive significant, ongoing public funding from the state...

s (agriculture, human ecology, labor relations and veterinary medicine) have been affiliated with SUNY since its inception, but did not have any such state affiliation prior to that time. Statutory college employees legally are employees of Cornell, not employees of SUNY. The State Education Law gives the SUNY Board of Trustees the authority to approve Cornell's appointment of the deans/unit heads of the statutory colleges, and control of the level of state funding for the statutory colleges.

Today, state support is significant. In 2007-08, Cornell received a total of $174 million of state appropriations for operations. Of the $2.5 billion in capital spending budgeted for 2007–2017, $721 million was to come from the state of New York.

Medical education

Starting in 1878, Cornell's Ithaca campus offered a pre-medical school curriculum, although most medical students enrolled in medical school directly after high school. In 1896, three New York City institutions, the University Medical College, the Loomis Laboratory and the Bellevue Hospital Medical College united with the goal of affiliating with New York UniversityNew York University

New York University is a private, nonsectarian research university based in New York City. NYU's main campus is situated in the Greenwich Village section of Manhattan...

(NYU). Unfortunately, NYU imposed a number of surprising new policies including limiting faculty to what they would have otherwise earned in private practice. The faculty revolted in 1897 and sought return of the property of the three former institutions, with a resulting lawsuit. On March 22, 1904 and April 5, 1904, the New York State Court of Appeals ordered NYU to return property to Loomis Laboratory because the NYU Dean had breached oral promises made to form the merger. Having won their separation from NYU, the medical faculties sought a new university affiliation, and on April 14, 1898, Cornell's Board of Trustees voted to create a medical school and elected former NYU professors as its Dean and faculty. The school opened on October 4, 1898 in the Loomis Laboratory facilities. In 1900, a new campus on First Avenue on the upper East Side of Manhattan opened which was donated by Oliver Hazard Payne

Oliver Hazard Payne

Oliver Hazard Payne was an American businessman, organizer of the American Tobacco trust, and assisted with the formation of U.S. Steel, and was affiliated with Standard Oil. He is considered one of the 100 wealthiest Americans, having left an enormous fortune. His estate at Esopus, New York,...

. Cornell also began a program in the fall of 1898 to allow students to take their first two years of medical school in Ithaca, with Stimpson Hall being constructed to house that program. The building opened in 1903. The M.D. degree program was open to both men and women, but women were required to study in Ithaca for their first two years. In 1908, Cornell was one of the early medical schools to require an undergraduate degree as a prerequisite to admission to the M.D. program. In 1913, Cornell's medical school affiliated with New York Hospital as its teaching hospital. Unlike the New York branch of the medical school which was well endowed, the Ithaca branch was subsidized by the University, and the Trustees reduced its scope to just first year students in 1910, and eventually phased it out.

Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic

At his death in 1927, Payne Whitney bestowed the funds to build and endow the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic on the Upper East Side of Manhattan...

, which became the name for Weill Cornell's large psychiatric effort. That same year, the college became affiliated with New York Hospital and the two institutions moved to their current joint campus in 1932. The hospital's Training School for Nurses became affiliated with the university in 1942, operating as the Cornell Nursing School until it closed in 1979.

In 1998, Cornell University Medical College's affiliate hospital, New York Hospital, merged with Presbyterian Hospital (the affiliate hospital for Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, often known as P&S, is a graduate school of Columbia University that is located on the health sciences campus in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan...

). The combined institution operates today as NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital

NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital

NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital is a prominent university hospital in New York City affiliated with two Ivy League medical schools: Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons and Cornell University's Weill Medical College. It is composed of two distinct medical centers, Columbia...

. Despite the clinical alliance, the faculty and instructional functions of the Cornell and Columbia units remain distinct and independent. Multiple fellowships and clinical programs have merged, however, and the institutions are continuing in their efforts to bring together departments, which could enhance academic efforts, reduce costs, and increase public recognition. All hospitals in the NewYork-Presbyterian Healthcare System

NewYork-Presbyterian Healthcare System

The NewYork-Presbyterian Healthcare System is a network of independent, cooperating, acute-care and community hospitals, continuum-of-care facilities, home-health agencies, ambulatory sites, and specialty institutes in the New York metropolitan area....

are affiliated with one of the two colleges.

Also in 1998, the medical college was renamed as Weill Medical College of Cornell University after receiving a substantial endowment from Sanford I. Weill

Sanford I. Weill

Sanford I. "Sandy" Weill is an American banker, financier and philanthropist. He is a former chief executive officer and chairman of Citigroup. He served in those positions until October 1, 2003, and April 18, 2006, respectively....

, then Chairman of Citigroup

Citigroup

Citigroup Inc. or Citi is an American multinational financial services corporation headquartered in Manhattan, New York City, New York, United States. Citigroup was formed from one of the world's largest mergers in history by combining the banking giant Citicorp and financial conglomerate...

.

Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory

Curtiss-Wright built this lab facility located in the suburbs of Buffalo, New YorkBuffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

as a part of the World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

effort. As a part of its tax planning in the wake of the war effort, Curtiss-Wright donated the facility to Cornell University

Cornell University

Cornell University is an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, United States. It is a private land-grant university, receiving annual funding from the State of New York for certain educational missions...

to operate "as a public trust" and received a charitable tax deduction. Seven other east coast aircraft companies also donated $675,000 to provide working capital for the lab. The lab operated under the name Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory from 1946 until 1972. During this same time, Cornell formed a new Graduate School of Aerospace Engineering on its Ithaca, New York

Ithaca, New York

The city of Ithaca, is a city in upstate New York and the county seat of Tompkins County, as well as the largest community in the Ithaca-Tompkins County metropolitan area...

campus.

CAL invented the first crash test dummy

Crash test dummy

Crash test dummies are full-scale anthropomorphic test devices that simulate the dimensions, weight proportions and articulation of the human body, and are usually instrumented to record data about the dynamic behavior of the ATD in simulated vehicle impacts...

in 1948, the automotive seat belt

Seat belt

A seat belt or seatbelt, sometimes called a safety belt, is a safety harness designed to secure the occupant of a vehicle against harmful movement that may result from a collision or a sudden stop...

in 1951, the first mobile field unit with Doppler

Pulse-doppler radar

Pulse-Doppler is a 4D radar system capable of detecting both target 3D location as well as measuring radial velocity . It uses the Doppler effect to avoid overloading computers and operators as well as to reduce power consumption...

weather radar

Weather radar

Weather radar, also called weather surveillance radar and Doppler weather radar, is a type of radar used to locate precipitation, calculate its motion, estimate its type . Modern weather radars are mostly pulse-Doppler radars, capable of detecting the motion of rain droplets in addition to the...

for weather-tracking

Weather forecasting

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the state of the atmosphere for a given location. Human beings have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia, and formally since the nineteenth century...

in 1956, the first accurate airborne simulation

Simulation

Simulation is the imitation of some real thing available, state of affairs, or process. The act of simulating something generally entails representing certain key characteristics or behaviours of a selected physical or abstract system....

of another aircraft

Aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air, or, in general, the atmosphere of a planet. An aircraft counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines.Although...

(the North American

North American Aviation

North American Aviation was a major US aerospace manufacturer, responsible for a number of historic aircraft, including the T-6 Texan trainer, the P-51 Mustang fighter, the B-25 Mitchell bomber, the F-86 Sabre jet fighter, the X-15 rocket plane, and the XB-70, as well as Apollo Command and Service...

X-15) in 1960, the first successful demonstration of an automatic terrain-following radar

Terrain-following radar

Terrain-following radar is an aerospace technology that allows a very-low-flying aircraft to automatically maintain a relatively constant altitude above ground level. It is sometimes referred-to as ground hugging or terrain hugging flight...

system in 1964, the first use of a laser

Laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of photons. The term "laser" originated as an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation...

beam to successfully measure gas density

Gas constant

The gas constant is a physical constant which is featured in many fundamental equations in the physical sciences, such as the ideal gas law and the Nernst equation. It is equivalent to the Boltzmann constant, but expressed in units of energy The gas constant (also known as the molar, universal,...

in 1966, the first independent HYGE sled test facility to evaluate automotive restraint

Seat belt

A seat belt or seatbelt, sometimes called a safety belt, is a safety harness designed to secure the occupant of a vehicle against harmful movement that may result from a collision or a sudden stop...

systems in 1967, the mytron, an instrument for research on neuromuscular behavior and disorders in 1969, and the prototype for the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is an agency of the United States Department of Justice that serves as both a federal criminal investigative body and an internal intelligence agency . The FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crime...

's fingerprint

Fingerprint

A fingerprint in its narrow sense is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. In a wider use of the term, fingerprints are the traces of an impression from the friction ridges of any part of a human hand. A print from the foot can also leave an impression of friction ridges...

reading system in 1972. CAL served as an "honest broker" making objective comparisons of competing plans to build military hardware. It also conducted classified counter-insurgency research in Thailand

Thailand

Thailand , officially the Kingdom of Thailand , formerly known as Siam , is a country located at the centre of the Indochina peninsula and Southeast Asia. It is bordered to the north by Burma and Laos, to the east by Laos and Cambodia, to the south by the Gulf of Thailand and Malaysia, and to the...

for the Defense Department. By the time of its divestiture, CAL had 1,600 employees. CAL conducted wind tunnel test on models of a number of skyscraper buildings, including most notably the John Hancock Tower

John Hancock Tower

The John Hancock Tower, officially named Hancock Place and colloquially known as The Hancock, is a 60-story, 790-foot skyscraper in Boston. The tower was designed by Henry N. Cobb of the firm I. M. Pei & Partners and was completed in 1976...

in Boston, Massachusetts and the 40-story Commerce House in Seattle, Washington.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, universities came under criticism for conducting war-related research particularly as the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

became unpopular, and Cornell University

Cornell University

Cornell University is an Ivy League university located in Ithaca, New York, United States. It is a private land-grant university, receiving annual funding from the State of New York for certain educational missions...

tried to sever its ties. Cornell accepted a $25,000,000 offer from EDP Technology, Inc. to purchase the lab in 1968. However, a group of lab employees who had made a competing $15,000,000 offer organized a lawsuit to block the sale. In May 1971, New York's highest court ruled that Cornell had the right to sell the lab. At the conclusion of the suit, EDP Technology could not raise the money, and in 1972, Cornell reorganized the lab as the for-profit Calspan Corporation and then sold its stock in Calspan to the public.

Race relations

Cornell enrolled its first African-American student in 1897. On December 4, 1906, Alpha Phi AlphaAlpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha is the first Inter-Collegiate Black Greek Letter fraternity. It was founded on December 4, 1906 at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Its founders are known as the "Seven Jewels". Alpha Phi Alpha developed a model that was used by the many Black Greek Letter Organizations ...

, the first Greek letter fraternity for African-Americans was founded at Cornell. Cornell had a very low black enrollment until the 1960s, when it formed the Committee on Special Educational Projects (COSEP) to recruit and mentor minority students. In 1969, Cornell established its Africana Studies and Research Center, one of the first such black studies programs in the Ivy League. On April 1, 1970, during a period of heightened racial tension, the building that housed the Africana Studies center burned down. Since 1972, Ujamaa, a special interest program dormitory located in North Campus Low Rise #10, provides housing for many minority students. However, in 1974, the New York State Board of Regents ordered it desegregated, and its status remained controversial for years.

Willard Straight Hall Takeover

Willard Straight Hall

Willard Straight Hall is the student union building on the central campus of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. It is located on Campus Road, adjacent to the Ho Plaza and the Gannett Health Center.-History:...

. The takeover was precipitated by increasing racial tension at the university and the students' frustration with the administration's lack of support for a black studies program. The specific catalysts for the takeover were a reprimand of three black students for an incident the previous December and a cross burning in front of the black women's cooperative and other cases of alleged racism.

By the following day a deal was brokered between the students and university officials, and on April 20, the takeover ended, with the administration ceding to some of the Afro-American Society's demands. The students emerged making a black-power salute and with guns in hand (the guns had been brought into Willard Straight Hall after the initial takeover). James A. Perkins

James A. Perkins

James A. Perkins was the seventh president of Cornell University. Born in 1911 in Philadelphia, Perkins graduated with high honors in 1934 from Swarthmore College and received a doctorate in political science from Princeton University in 1937...

, president of Cornell during the events, would resign soon after the crisis.

Some of the elements of the deal required faculty approval, and the faculty voted to uphold the reprimands of the three students on April 21. The faculty was asked to reconsider, and a group of 2,000 to 10,000 gathered in Barton Hall to debate the matter as the faculty deliberated. This "Barton Hall Community" formed a representative Constituent Assembly which undertook a comprehensive review of the University. Among the changes stemming from the crisis were the founding of an Africana Studies and Research Center

Cornell Africana Studies and Research Center

The Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University is an academic unit devoted to the study of the global migrations and reconstruction of African peoples, as well as patterns of linkages to the African continent . ASRC offers around 23 graduate and undergraduate courses each semester...

, an overhaul of the campus judicial system, and the addition of students to Cornell's Board of Trustees. The crisis also prompted New York to enact the Henderson Law requiring every college in the State to adopt rules for the maintenance of public order.

Yale

YALE

RapidMiner, formerly YALE , is an environment for machine learning, data mining, text mining, predictive analytics, and business analytics. It is used for research, education, training, rapid prototyping, application development, and industrial applications...

Professor Donald Kagan

Donald Kagan

Donald Kagan is an American historian at Yale University specializing in ancient Greece, notable for his four-volume history of the Peloponnesian War. 1987-1988 Acting Director of Athletics, Yale University. He was Dean of Yale College from 1989–1992. He formerly taught in the Department of...

, at Cornell through 1969 (1958-69) was once a liberal democrat

Liberal Democrat

Liberal Democrat can refer to:* Liberal Democrats, a UK political party* Liberal Democrats , an Italian political party* Liberal Democratic Party , a Japanese political party* Liberal Democrats , a Sudanese political party...

, but he changed his views in 1969 and became one of the original signers to the 1997 Statement of Principles by the neoconservative think tank Project for the New American Century

Project for the New American Century

The Project for the New American Century was an American think tank based in Washington, D.C. that lasted from 1997 to 2006. It was co-founded as a non-profit educational organization by neoconservatives William Kristol and Robert Kagan...

. According to Jim Lobe, cited in The Fall of the House of Bush by Craig Unger

Craig Unger

Craig Unger is an American journalist and writer. He grew up in Dallas, Texas, and attended Harvard University. His most recent book is The Fall of the House of Bush, about the internal feud in the Bush family and the rise and collusion of the neoconservative and Christian right in Republican party...

(p. 39, n.), Kagan's turn away from liberalism occurred in 1969 when Cornell University was pressured into starting a "Black Studies" program by gun-wielding students seizing Willard Straight Hall

Willard Straight Hall

Willard Straight Hall is the student union building on the central campus of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. It is located on Campus Road, adjacent to the Ho Plaza and the Gannett Health Center.-History:...

on campus: "Watching administrators demonstrate all the courage of Neville Chamberlain had a great impact on me, and I became much more conservative." On the eve of the 2000 presidential elections, Kagan and his son, Frederick Kagan

Frederick Kagan

Frederick W. Kagan is an American resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute , and a former professor of military history at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He graduated from Hamden High School before earning a B.A. in Soviet and East European studies and a Ph.D. in Russian and...

, published While America Sleeps

While America Sleeps

While America Sleeps is a book by historians Donald Kagan and Frederick Kagan, published September 2000. Their thesis was that the United States at the end of the Cold War resembled Britain following World War I. They argue for a policy of strengthening U.S. defense and a willingness to use...

, a call to increase defense spending.

Interdisciplinary studies

Historically, Cornell's colleges have operated with great autonomy, each with a separate admissions policy, separate faculty, separate fundraising staff and in many cases, separate tuition structure. However, the University has taken steps to encourage collaboration between related academic fields within the University and with outside organizations. In the 1960s, the University created a Division of Biological Sciences to unify related programs in the Art and Agriculture colleges. Although a success, the structure was ultimately dropped in 1999 due to difficulty with funding.A "Faculty of Computing and Information Science" was established in 1999 to unify computer science efforts throughout the University. This structure obviates the need for a separate school or college of computer science. For its first ten years, Robert Constable

Robert Lee Constable

Robert "Bob" Lee Constable is a professor of computer science and first and former dean of the department at Cornell University. He is known for his work on connecting computer programs and mathematical proofs, especially the NuPRL system. Constable received his PhD in 1968 under Stephen Kleene and...

served as its Dean.

Affordability and use of the endowment

Since the 1970s, tuition at Cornell and other Ivy League schools has grown much faster than inflation. This trend coincided with the creation of Federally guaranteed student loan programs. At the same time, the endowments of these schools continue to grow due to gifts and successful investments. Critics called for universities to keep their tuition at affordable levels and to not hoard endowment earnings. As a result, in 2008, Cornell and other Ivy Schools decided to increase the spending of endowment earnings in order to subsidize tuition for low and middle income families, reducing the amount of debt that Cornell students will incur. Cornell also placed a priority to soliciting endowed scholarships for undergraduates. In fall 2007, Cornell had 1,863 undergraduates (14% of all undergraduates) receiving federal Pell GrantPell Grant

A Pell Grant is money the federal government provides for students who need it to pay for college. Federal Pell Grants are limited to students with financial need, who have not earned their first bachelor's degree or who are not enrolled in certain post-baccalaureate programs, through participating...

s. Cornell's Pell Grant students roughly totals the combined Pell Grant recipients studying at Havard, Princeton and Yale.

Portrayal in fiction

Students and faculty have chronicled Cornell in works of fiction. The most notable was The Widening Stain which first appeared anonymously. It was since revealed to have been written by Morris BishopMorris Bishop

Morris Gilbert Bishop was an American scholar, historian, biographer, author, and humorist.Raised in Canada and New York, he attended Cornell from 1910–1913, earning a Bachelor's in 1913 and then a Master of Arts degree in 1914...

. Alison Lurie

Alison Lurie

Alison Lurie is an American novelist and academic. She won the Pulitzer Prize for her 1984 novel Foreign Affairs. Although better known as a novelist, she has also written numerous non-fiction books and articles, particularly on children's literature and the semiotics of dress.-Personal...

wrote a fictional account of the campus during the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

protests called The War Between the Tates

The War Between the Tates

The War Between the Tates is a campus novel by Alison Lurie that takes place an elite university during the upheavals of the late sixties and gently and deftly skewers all sides in the turmoils and conflicts of that era — opposition to the Vietnam war, the start of the feminist movement, the...

. Matt Ruff

Matt Ruff

Matthew Theron Ruff is an American author of thriller, science-fiction and comic novels.-Background and education:...

captured Cornell around 1970 in The Fool on the Hill

The Fool on the Hill

"The Fool on the Hill" is a song by The Beatles. It was written and sung by Paul McCartney and recorded in 1967...

. Richard Fariña

Richard Fariña

Richard George Fariña was an American writer and folksinger.-Early years and education:Richard Fariña was born in Brooklyn, New York, of Cuban and Irish descent. He grew up in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn and attended Brooklyn Technical High School...

wrote a novel based on a real 1958 protest led by Kirkpatrick Sale

Kirkpatrick Sale

Kirkpatrick Sale is an independent scholar and author who has written prolifically about political decentralism, environmentalism, luddism and technology...

against in loco parentis policies in Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me is a novel by Richard Fariña. First published in the United States during 1966 the novel, based largely on Fariña's college experiences and travels, is a comic picaresque story that is set in the American West, in Cuba during the Cuban Revolution, and at an...

.

See also

For the history of the Ithaca campus, see:- Cornell Central CampusCornell Central CampusCentral Campus is the primary academic and administrative section of Cornell University's Ithaca, New York campus. It is bounded by Libe Slope on the west, Fall Creek on the north, and Cascadilla Creek on the South.-History:...

- Cornell West CampusCornell West CampusWest Campus is a residential section of Cornell University's Ithaca, New York campus located west of Libe Slope and between the Fall Creek gorge and the Cascadilla gorge. It now primarily houses transfer students, second year, and upperclassmen. West Campus is currently part of a residential...

- Cornell North CampusCornell North CampusNorth Campus is a residential section of Cornell University's Ithaca, New York campus. It primarily houses freshmen. North Campus offers programs which ease the transition into college life for incoming freshman. The campus offers interactions with faculty and other programs which are designed to...