History of Kiev

Encyclopedia

The history of Kiev

, the largest city and the capital of Ukraine

, is documented as going back at least 1400 years. Kiev was founded by three brothers, Kyi, Scheck, and Khoryv, and their sister Lybed. Kiev is named after Kyi, the eldest brother. The exact century of city foundation has not been determined. Legend has it that the emergence of a great city on the future location of Kiev

was prophesied by St. Andrew

(d. AD 60/70) fascinated by the spectacular location on the hilly shores of the Dnieper River

. The city is thought to have existed as early as the 6th century, initially as a Slavic settlement. Gradually acquiring eminence as the center of the East Slavic civilization, Kiev reached its Golden Age

as the center Kievan Rus'

in the 10th–12th centuries.

Its political, but not cultural, importance started to decline somewhat when it was completely destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1240. In the following centuries Kiev was a provincial capital of marginal importance in the outskirts of the territories controlled by its powerful neighbors: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

and the Grand Duchy of Moscow

, later the Russian Empire

. A Christian city since 988

, it still played an important role in preserving the traditions of Orthodox Christianity

, especially at times of domination by Catholic

Poland, and later the atheist

Soviet Union

.

The city prospered again during the Russian industrial revolution

in the late 19th century. In the turbulent period following the Russian Revolution

Kiev, caught in the middle of several conflicts, quickly went through becoming the capital of several short-lived Ukrainian states

. From 1921 the city was part of the Soviet Union, since 1934 as a capital of Soviet Ukraine

. In World War II

, the city was destroyed again, almost completely, but quickly recovered in the post-war years becoming the third most important city of the Soviet Union, the capital of the second most populous Soviet republic

. It now remains the capital of Ukraine, independent since 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

.

According to a legend, Kiev was founded in the 5th century by East Slavs. The legend of Kyi, Schek and Khoryv speaks of a founder-family consisting of a Slavic tribe leader Kyi, the eldest, his brothers Schek and Khoriv, and also their sister Lybid, who founded the city. Kiev (Kyiv, Київ, in Ukrainian) is translated as "belonging to Kyi".

According to a legend, Kiev was founded in the 5th century by East Slavs. The legend of Kyi, Schek and Khoryv speaks of a founder-family consisting of a Slavic tribe leader Kyi, the eldest, his brothers Schek and Khoriv, and also their sister Lybid, who founded the city. Kiev (Kyiv, Київ, in Ukrainian) is translated as "belonging to Kyi".

The non-legendary time of the founding of the city is harder to ascertain. Scattered Slavic settlements existed in the area from the 6th century, but it is unclear whether any of them later developed into the city. Eighth century fortifications were built upon a Slavic settlement apparently abandoned some decades before. It is unclear whether these fortifications were built by the Slavs. Some western historians (i.e. Kevin Alan Brook) suppose that Kiev was founded by Khazars

or Magyars, both Turkic peoples. Kiev is a Turkic place name (Küi = riverbank + ev = settlement). However, the Primary Chronicle

(a main source of information about the early history of the area) mentions Slavic Kievans telling Askold and Dir

that they live without a local ruler and pay a tribute to Khazars in an event attributed to the 9th century. At least during the 8th and 9th centuries Kiev functioned as an outpost of the Khazar empire. A hill-fortress, called Sambat (Old Turkic for "high place") was built to defend the area.

According to the Hustyn Chronicle , Askold and Dir

(Haskuldr and Dyri) ruled Rus' Khaganate

at least in 842. They were Varangian princes, probably of Swedish origin, not the Rurikids. According to the Annals of St. Bertin (Annales Bertiniani

) for the year 839, Louis the Pious, the Frankish emperor, came to the conclusion that the people called Rhos (qui se, id est gentem suum, Rhos vocari dicebant) belong to the gens of Swedes (eos gentis esse Sueonum).

According to Primary Chronicle

, Oleg of Novgorod

(Helgi of Holmgard) conquered Kiev in 882. He was a descendant of Rurik

, a Varangian

pagan chieftain.

DNA Testing of the Rurikid and Gediminid Princes The date given for Oleg's conquest of the town in the Primary Chronicle

is uncertain, and some historians, such as Omeljan Pritsak

and Constantine Zuckerman

, dispute this and maintain that Khazar rule continued as late as the 920s (documentary evidence exists to support this assertion — see the Kievian Letter

and Schechter Letter

.)

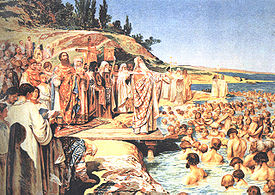

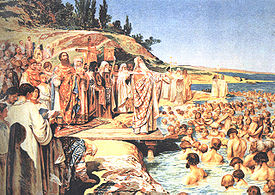

From Oleg's seizure of the city until 1169 Kiev was the capital of Kievan Rus'

which was initially ruled by the Varangian Rurikid dynasty which was gradually Slavisized. The Kievan Grand Prince

s had traditional primacy over the other rulers of the land and the Kiev princehood was a valuable prize in the intra-dynastic rivalry. In 968 the city withstood a siege

by the nomadic Pechenegs. In 988 by the order of the Grand Prince Vladimir I of Kiev

(St. Vladimir or Volodymyr), the city residents baptized en-masse in the Dnieper river, an event the symbolized the Baptism of Kievan Rus'

. Kiev reached the height of its position of political and cultural Golden Age

in the middle of the 11th century under Vladimir's son Yaroslav the Wise. In 1051, prince Yaroslav assembled the bishops at St. Sophia Cathedral and appointed Hilarion

, the first native of the Kievan Rus', as metropolitan bishop, that the decision reflects an anti-Byzantine bias. In 1054, the Kievan Church did not take note of the fact that the East–West Schism

began, maintaining very good relations with Rome (i.e. prince Iziaslav I of Kiev

's request to Pope Gregory VII

to extend to Kievan Rus' "the patronage of St. Peter", fulfilled by the pope by sending Iziaslav a crown from Rome in 1075).

The following years were marked by the rivalries of the competing princes of the dynasty and weakening of Kiev's political influence, although Kiev temporarily prevailed after the defeat of the Polotsk at the Battle on the river Nemiga

(1067) that also led to the burning of Minsk

. In 1146, the next Ruthenian bishop, Klym Smoliatych (Kliment of Smolensk), was appointed to serve as the Metropolitan of Kiev. In 1169 Andrei of Suzdal

sent an army against Mstislav Iziaslavich

and Kiev. Led by one of his sons, it consisted of the forces of eleven other princes, representing all three of the main branches of the dynasty against the fourth, Iziaslavichi of Volynia. The allies were victorious. The sack of Kiev allowed the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal

to take a leading role as the predecessor of the modern Russian state.

In 1203 Kiev was captured an burned by Prince Rurik Rostislavich

. In the 1230s the city was sieged and ravaged by different Rus' princes several times. Finally, the Mongol-Tatar forces led by Batu Khan

besieged, and then completely destroyed Kiev on December 6, 1240.

In 1245, Petro Akerovych

(of Ruthenian origin), the Metropolitan of Kiev, participated in the First Council of Lyon

, where he informed Catholic Europe of the Mongol/Tatar threat. In 1299, Maximus

(of Greek origin), the Metropolitan of Kiev, eventually moved the seat of the Metropolitanate from Kiev to Vladimir-on-Kliazma

, keeping the title. Since 1320, Kiev was the site of a new Catholic bishopric, when Henry, a Dominican friar, was appointed the first missionary Bishop of Kiev. In early 1320s, a Lithuanian army led by Gediminas defeated a Slavic army led by Stanislav of Kiev at the Battle on the Irpen' River

, and conquered the city. The Tatars, who also claimed Kiev, retaliated in 1324–1325, so while Kiev was ruled by a Lithuanian prince, it had to pay a tribute to the Golden Horde

.

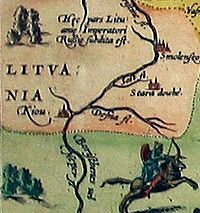

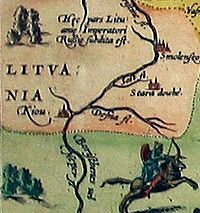

Kiev became a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Kiev became a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

after the Battle at Blue Waters in 1362, when Algirdas

, Grand Duke of Lithuania, beat a Golden Horde

army. During the period between 1262 and 1471, Kiev has been ruled by Lithuanian princes from different families. By the order of Casimir Jagiellon, the Principality of Kiev was abolished and the Kiev Voivodship was established in 1471. Lithuanian statesman Martynas Goštautas was appointed as the first voivode of Kiev the same year; his appointment was met by hostility from locals.

The city was frequently attacked by Crimean Tatars

and in 1482 was destroyed again by Crimean Khan

Meñli I Giray

. Despite its little remaining political significance, the city still played an important role as a seat of the local Orthodox metropolitan

. However, starting in 1494 the city's local autonomy (Magdeburg rights

) gradually increased in a series of acts of Lithuanian Grand Dukes and Polish Kings which was finalized by 1516 charter granted by Sigismund I the Old

.

Kiev had a Jewish community of some significance in the early sixteenth century. The tolerant Sigismund II Augustus

granted equal rights to Kiev's Jews on the grounds that they paid the same taxes as Podil's burghers. Polish sponsorship of Jewish settlement in Kiev added fuel to the conflict that already existed between the Orthodox and Catholic churches.

that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

, Kiev with other Ukrainian territories was transferred to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, and it became a capital of the Kiev Voivodeship. Its role of Orthodox center strengthened due to expansion of Roman Catholicism under Polish rule. In 1632, Peter Mogila the Orthodox Metropolitan

of Kiev and Galicia established the Kiev Mogila Academy, an educational institution aimed to preserve and develop Ukrainian culture and Orthodox faith despite Polish Catholic oppression. Although ruled by the church, the academy provided students with educational standards close to universities of Western Europe (including multilingual training) and became the foremost educational center, both religious and secular.

In 1648 Bohdan Khmelnytsky

's cossacks triumphantly entered Kiev in the course of their uprising

establishing the rule of their Cossack Hetmanate

in the city. The Zaporizhian Host had a special status within the newly formed political entity. The complete sovereignty of Hetmanate did not last long as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

refused to recognize it and resumed hostilities. In January 1654 Khmelnytsky decided to sign the Treaty of Pereyaslav

with Tsardom of Russia

to obtain a military support against the Polish Crown. However, in November 1656 the Muscovites concluded the Truce of Vilna

with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was approved by Bohdan Khmelnytsky. After his death, in the atmosphere of sharp conflicts his successor became Ivan Vyhovsky

who signed the Treaty of Hadiach

. It was ratified by the Crown in a limited version. According to Vyhovsky original intention, Kiev was to become the capital of the Duchy of Ruthenia on the limited federate rights within the Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth. However, this part of the Treaty was removed during the ratification. In the meantime, Vyhovsky's opponent Yuri Khmelnytsky signed the Second Treaty of Pereyaslav in October 1659 with a representative of Russian tsar.

ceded Smolensk, Severia and Chernigov, and, on paper only for a period of two years, the city of Kiev to the Tsardom of Russia

. Finally, the Eternal Peace of 1686 acknowledged the status quo, and put Kiev under the control of Russia for the centuries to come with the territory, slowly losing the autonomy which was finally abolished in 1775 by the Empress Catherine the Great. Noone of Polish-Russian treaties concerning Kiev has been never ratified.

In 1834, St. Vladimir University

was established in Kiev (now known as National Taras Shevchenko University of Kiev). The great Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko

cooperated with its geography department as a field researcher and editor. However, the Magdeburg Law existed in Kiev till that year, when it was abolished by the Decree of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia

on December 23, 1834.

Even after Kiev and the surrounding region ceased being a part of Poland, Poles continued to play an important role. In 1812 there were over 43,000 Polish nobelmen in Kiev province, compared to only approximately 1,000 "Russian" nobles. Typically the nobles spent their winters in the city of Kiev, where they held Polish balls and fairs. Until the mid-eighteenth century Kiev (Polish Kijow) was Polish in culture. although Poles made up no more than ten percent of Kiev's population and 25% of its voters. During the 1830s Polish was the language of Kiev's educational system, and until Polish enrollment in Kiev's university of St. Vladimir was restricted in the 1860s they made up the majority of that school's student body. The Russian government's cancellation of Kiev city's autonomy and its placement under the rule of bureaucrats appointed from St. Petersburg was largely motivated by fear of Polish insurrection in the city. Warsaw factories and fine Warsaw shops had branches in Kiev. Jozef Zawadski, founder of Kiev's stock exchange, served as the city's mayor in the 1890s. Kieven Poles tended to be friendly towards the Ukrainian national movement in the city, and some took part in Ukrainian organizations. Indeed, many of the poorer Polish nobles became Ukrainianized in language and culture and these Ukrainians of Polish descent constituted an important element of the growing Ukrainian national movement. Kiev served as a meeting point where such activists came together with the pro-Ukrainian descendents of Cossack officers from the left bank. Many of them would leave the city for the surrounding countryside in order to try to spread Ukrainian ideas among the peasants.

Even after Kiev and the surrounding region ceased being a part of Poland, Poles continued to play an important role. In 1812 there were over 43,000 Polish nobelmen in Kiev province, compared to only approximately 1,000 "Russian" nobles. Typically the nobles spent their winters in the city of Kiev, where they held Polish balls and fairs. Until the mid-eighteenth century Kiev (Polish Kijow) was Polish in culture. although Poles made up no more than ten percent of Kiev's population and 25% of its voters. During the 1830s Polish was the language of Kiev's educational system, and until Polish enrollment in Kiev's university of St. Vladimir was restricted in the 1860s they made up the majority of that school's student body. The Russian government's cancellation of Kiev city's autonomy and its placement under the rule of bureaucrats appointed from St. Petersburg was largely motivated by fear of Polish insurrection in the city. Warsaw factories and fine Warsaw shops had branches in Kiev. Jozef Zawadski, founder of Kiev's stock exchange, served as the city's mayor in the 1890s. Kieven Poles tended to be friendly towards the Ukrainian national movement in the city, and some took part in Ukrainian organizations. Indeed, many of the poorer Polish nobles became Ukrainianized in language and culture and these Ukrainians of Polish descent constituted an important element of the growing Ukrainian national movement. Kiev served as a meeting point where such activists came together with the pro-Ukrainian descendents of Cossack officers from the left bank. Many of them would leave the city for the surrounding countryside in order to try to spread Ukrainian ideas among the peasants.

According to the Russian census of 1874, of Kiev's 127,251 people 38,553 (39%) spoke "Little Russian" (the Ukrainian language), 12,917 (11 percent) spoke Yiddish, 9,736 (10 percent) spoke Great Russian, 7,863 (6 percent) spoke Polish, and 2,583 (2 percent) spoke German. 48,437 (or 49%) of Kiev's residents were listed as speaking "generally Russian speech (obshcherusskoe narechie)." Such people were typically Ukrainians and Poles who could speak aenough Russian to be counted as Russian-speaking.

From the late 18th century until the late 19th century, city life was increasingly dominated by Russian military and ecclesiastical concerns. Russian Orthodox Church

institutions formed a significant part of Kiev's infrastructure and business activity at that time. In the winter 1845-1846, the famous historian, Mykola Kostomarov (Nikolay Kostomarov

in Russian), founded the secret political society, the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

whose members put forward the idea of federation

of free Slavic people with Ukrainians as a distinct group among them rather than a part of the Russian nation. The Brotherhood's ideology was a synthesis of programmes of three movements: Ukrainian autonomists, Polish democrats, and Russian Decembrists in Ukraine. The society was quickly suppressed by the Tsarist authorities in March–April 1847.

Following the gradual loss of Ukraine's autonomy and suppression of the local Ukrainian and Polish cultures, Kiev experienced growing Russification

in the 19th century by means of Russian

migration, administrative actions (the Valuev Circular of 1863), and social modernization

. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city was dominated by Russian

-speaking population, while the lower classes retained Ukrainian folk culture to a significant extent. According to the census of 1897, of Kiev's approximately 240,000 people approximately 56% of the population spoke the Russian language, 23% spoke the Ukrainian language, 12.5% spoke Yiddish, 7% spoke Polish and 1% spoke the Belarussian language. Despite the Russian cultural dominance in the city, enthusiasts among ethnic Ukrainian nobles, military and merchants made recurrent attempts to preserve native culture in Kiev (by clandestine book-printing, amateur theater, folk studies etc.).

During the Russian industrial revolution in the late 19th century, Kiev became an important trade and transportation center of the Russian Empire

, specializing in sugar and grain export by railroad and on the Dnieper river. As of 1900, the city also became a significant industrial center, having a population of 250,000. Landmarks of that period include the railway infrastructure, the foundation of numerous educational and cultural facilities as well as notable architectural monuments (mostly merchant-oriented, i.e. Brodsky Synagogue

).

At that time, a large Jewish community emerged in Kiev, developing its own ethnic culture and business interests. This was stimulated by the prohibition of Jewish settlement in Russia proper (Moscow

and Saint Petersburg

) — as well as further eastwards. Expelled from Kiev in 1654, Jews probably were not able to settle in the city again until the early 1790s. On December 2, 1827, Nicolas I of Russia expelled Kiev's seven hundred Jews. In 1836, the Pale of Settlement

banned Jews from Kiev as well, fencing off the city's districts from the Jewish population. Thus, at mid-century Jewish merchants who came to the fairs could stay in Kiev for up to six months. In 1881 and 1905, notorious pogroms

in the city resulted in the death of about 100 Jews.

The development of aviation (both military and amateur) became another notable mark of distinction of early 1900s Kiev. Prominent aviation figures of that period include Kievites Pyotr Nesterov

(well-known aerobatics

pioneer) and Igor Sikorsky

. The world's first helicopter

was built and tested in Kiev by Sikorsky. In 1892 the first electric tram line

of the Russian Empire was established in Kiev.

In 1917 the Central Rada (Tsentralna Rada), a Ukrainian self-governing body headed by the famous historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky

In 1917 the Central Rada (Tsentralna Rada), a Ukrainian self-governing body headed by the famous historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky

, was established in the city. Later that year, Ukrainian autonomy was declared.

On 7 November 1917 it was transformed into an independent Ukrainian People's Republic

with the capital in Kiev. During this short period of independence, Kiev experienced rapid growth of its cultural and political status. An Academy of Sciences and professional Ukrainian

-language theaters and libraries were established by the new government.

Later Kiev became a war zone in the lasting and bloody struggle between Ukrainian, Polish and Russian Bolshevik

governments in the time of Russian Revolution

, Ukrainian-Soviet War

, Polish-Ukrainian War

and Polish-Soviet War

.

The "January Uprising

The "January Uprising

" on the 29th 1918, saw Bolshevist troops enter the city and declare a Soviet Coup d'etat. The Kiev garrison joined with the Soviets and deposed the Rada. Odoevsky

attempted to form a new government but was arrested. The Bolshevik

s established Kharkov as the capital of the Soviets of the Ukraine. By March Kiev had been occupied by the Germans.

With the withdrawal of German troops, an independent Ukraine was declared in Kiev under Symon Petlyura. It was then briefly occupied by the White armies before the Soviets once more took control in 1920. In May 1920, during the Russo-Polish War Kiev was briefly captured by the Polish Army but they were driven out by the Red Army

.

After the Ukrainian SSR

was formed in 1922, Kharkiv

was declared its capital. Kiev, being an important industrial center, continued to grow. In 1925 the first public buses run on Kiev streets, and ten years latter - the first trolleybus

es. In 1927 the suburban areas of Darnytsia

, Lanky, Chokolivka, and Nikolska slobidka were included into city. In 1932 Kiev became the administrative center of newly created Kiev Oblast

.

In 1932-33, the city population, as most of the other Ukrainian territories, suffered from Holodomor

. In Kiev, bread and other food products were distributed to workers by food cards according to daily norm, but even with cards, bread was in limited supply, and citizens were standing overnight in lines to obtain it.

In 1934 the capital of Ukrainian SSR was moved from Kharkov to Kiev. The goal was to fashion a new proletariat utopia based on Stalin's blueprints. The city's architecture was made over, but a much greater impact on the population was Soviet social policy, which involved large-scale purges, coercion, and rapid movement toward totalitarianism in which dissent and non-communist organizations were not tolerated.

In the 1930s the process of destruction of churches and monuments, which started in 1920s, reached the most dramatic turn. Many hundreds year old churches, and structures, such as St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral, Fountain of Samson

, were demolished. The other, such as Saint Sophia Cathedral

were confiscated. City population continued to increase mostly by migrants. The migration changed the ethnic demographics of the city from the previous Russian-Ukrainian parity to predominantly Ukrainian, although Russian remained the dominant language.

In the 1930s, Kievans also suffered from the controversial Soviet political policy of that time. While encouraging lower-class Ukrainians to pursue careers and develop their culture (see Ukrainization

), the Communist regime soon began harsh oppression of political freedom, Ukraine's autonomy and religion. Recurring political trials were organized in the city to purge "Ukrainian nationalists", "Western spies" and opponents of Joseph Stalin

inside the Bolshevik party. As numerous historic churches were destroyed or vandalized, the clergy repressed.

In the late 1930s, clandestine mass executions began in Kiev. Thousands of Kievites (mostly intellectuals and party activists) were arrested in the night, hurriedly court-martialed, shot and buried in mass graves. The main execution sites were Babi Yar

and the Bykivnia

forest. Tens of thousands were sentenced to GULAG

camps. In the same time, the city's economy continued to grow, following Stalin's industrialization policy.

occupied Kiev on 19 September 1941 (see the Battle of Kiev

). Overall, the battle proved disastrous for the Soviet side but it significantly delayed the German advances

. The delay also allowed the evacuation of all significant industrial enterprises from Kiev to the central and eastern parts of the Soviet Union, away from the hostilities, where they played a major role in arming the Nazi

fighting Red Army

(see, for example, Kiev Arsenal

).

Before the evacuation, the Red Army planted more than ten thousand mines throughout Kiev, controlled by wireless detonators. On 24 September, when the German invaders had settled into the city, the mines were detonated, causing many of the major buildings to collapse, and setting the city ablaze for five days. More than a thousand Germans were killed.

Babi Yar

Babi Yar

, a location in Kiev, became a site of one of the most infamous Nazi WWII war crime

s. During two days in September 1941, at least 33,771 Jews

from Kiev and its suburbs were massacred at Babi Yar by the SS Einsatzgruppen

, according to their own reports. Babi Yar was a site of additional mass murder

s of captured Soviet citizens over the following years, including Roma, POWs and anyone suspected in aiding the resistance movement

, perhaps as many as 60,000 additional people. The role of Ukrainian collaborators in this massacre of Jews, now thoroughly documented, is still a matter of painful debate in Ukraine.

In the "Hunger Plan

" prepared ahead of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, with the aim of ensuring that that Germans were given priority over food supplies at the expense of everyone else, the inhabitants of Kiev were defined as "superfluous eaters" who were to be "gotten rid of" by the cutting off of all food supplies to the city - the food to be diverted to feeding the Wehrmacht

troops and Germany's own population. Luckily for the people of Kiev, this part of the "Hunger Plan" was never fully implemented.

An underground resistance quickly established by local patriots was active until the liberation from Nazi occupation. During the war, Kiev was heavily bombarded, especially in the beginning of the war and the city was largely destroyed including many of its architectural landmarks (only one building remained standing on the Khreschatyk

, a main street of Kiev).

While the whole of Ukraine was a '[Third] Reich commissariat', under a Nazi Reichskommissar

, the region surrounding Kiew (as the Germans spell its name) was one of the six subordinate 'general districts', February 1942 - 1943 Generalbezirk Kiew, under Generalkommissar Waldemar Magunia (b. 1902 - d. 1974, also NSDAP)

The city was recaptured by the Soviet Army

advancing westward on 6 November 1943. For its role during the War, the city was later awarded the title Hero City

.

. The arms race of the Cold War

caused the establishment of a powerful technological complex in the city (both R&D and production), specializing in aerospace

, microelectronics

and precision optics

. Dozens of industrial companies were created employing highly skilled personnel. Sciences and technology became the main issues of Kiev's intellectual life. Dozens of research institutes in various fields formed the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.

Kiev also became an important military center of the Soviet Union. More than a dozen military schools and academies were established here, also specializing in high-tech warfare (see also Soviet education). This created a labor force demand which fed migration from rural areas of both Ukraine and Russia. Large suburbs and an extensive transportation infrastructure were built to accommodate the growing population. However, many rural-type buildings and groves have survived on the city's hills, creating Kiev's image as one of the world's greenest cities.

Kiev also became an important military center of the Soviet Union. More than a dozen military schools and academies were established here, also specializing in high-tech warfare (see also Soviet education). This created a labor force demand which fed migration from rural areas of both Ukraine and Russia. Large suburbs and an extensive transportation infrastructure were built to accommodate the growing population. However, many rural-type buildings and groves have survived on the city's hills, creating Kiev's image as one of the world's greenest cities.

The city grew tremendously in the 1950s through 1980s. Some significant urban achievements of this period include establishment of the Metro

, building new river bridges (connecting the old city with Left Bank suburbs), and Boryspil Airport

(the city's second, and later international airport).

Systematic oppression of pro-Ukrainian intellectuals, conveniently and uniformly dubbed as "nationalists", was carried under the propaganda campaign against Ukrainian nationalism

threatening the Soviet way of life. In cultural sense it marked a new waive of Russification

in the 1970s, when universities and research facilities were gradually and secretly discouraged from using Ukrainian

. Switching to Russian

, as well as choosing to send children to Russian schools was expedient for educational and career advancement.

Thus the city underwent another cycle of gradual Russification.

Every attempt to dispute Soviet rule was harshly oppressed, especially concerning democracy, Ukrainian SSR's self-government, and ethnic-religious problems. Campaigns against "Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism" and "Western influence" in Kiev's educational and scientific institutions were mounted repeatedly. Due to limited career prospects in Kiev, Moscow became a preferable life destination for many Kievans (and Ukrainians as a whole), especially for artists and other creative intellectuals. Dozens of show-business celebrities in modern Russia were born in Kiev.

In the 1970s and later 1980s–1990s, given special permission from the Soviet government, a significant part of the city's Jews migrated to Israel

and the West.

The Chernobyl accident of 1986 affected city life tremendously, both environmentally and socio-politically. Some areas of the city have been polluted by radioactive dust. However, Kievans were neither informed about the actual threat of the accident, nor recognized as its victims. Moreover, on May 1, 1986 (a few days after the accident), local CPSU

leaders ordered Kievans (including hundreds of children) to take part in a mass civil parade in the city's center—"to prevent panic". Later, thousands of refugees from accident zone were resettled in Kiev.

After 57 years as the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union, Kiev became the capital of independent Ukraine in 1991.

After 57 years as the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union, Kiev became the capital of independent Ukraine in 1991.

The city was the site of mass protests over the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election

by supporters of opposition candidate Viktor Yushchenko

beginning on 22 November 2004 at Independence Square. Much smaller counter-protests in favor of Viktor Yanukovych

also took place.

Kiev hosted the Eurovision Song Contest 2005

on 19 and 21 May in the Palace of Sports.

The current city mayor is Leonid Chernovetsky.

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

, the largest city and the capital of Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

, is documented as going back at least 1400 years. Kiev was founded by three brothers, Kyi, Scheck, and Khoryv, and their sister Lybed. Kiev is named after Kyi, the eldest brother. The exact century of city foundation has not been determined. Legend has it that the emergence of a great city on the future location of Kiev

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

was prophesied by St. Andrew

History of Christianity in Ukraine

The History of Christianity in Ukraine dates back to the earliest centuries of the apostolic church. It has remained the dominant religion in the country since its acceptance in 988 by Vladimir the Great , who instated it as the state religion of Kievan Rus', a medieval East Slavic state.Although...

(d. AD 60/70) fascinated by the spectacular location on the hilly shores of the Dnieper River

Dnieper River

The Dnieper River is one of the major rivers of Europe that flows from Russia, through Belarus and Ukraine, to the Black Sea.The total length is and has a drainage basin of .The river is noted for its dams and hydroelectric stations...

. The city is thought to have existed as early as the 6th century, initially as a Slavic settlement. Gradually acquiring eminence as the center of the East Slavic civilization, Kiev reached its Golden Age

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology and legend and refers to the first in a sequence of four or five Ages of Man, in which the Golden Age is first, followed in sequence, by the Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and then the present, a period of decline...

as the center Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus was a medieval polity in Eastern Europe, from the late 9th to the mid 13th century, when it disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of 1237–1240....

in the 10th–12th centuries.

Its political, but not cultural, importance started to decline somewhat when it was completely destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1240. In the following centuries Kiev was a provincial capital of marginal importance in the outskirts of the territories controlled by its powerful neighbors: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state from the 12th /13th century until 1569 and then as a constituent part of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1791 when Constitution of May 3, 1791 abolished it in favor of unitary state. It was founded by the Lithuanians, one of the polytheistic...

, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

and the Grand Duchy of Moscow

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow or Grand Principality of Moscow, also known in English simply as Muscovy , was a late medieval Rus' principality centered on Moscow, and the predecessor state of the early modern Tsardom of Russia....

, later the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. A Christian city since 988

Baptism of Kievan Rus'

The Christianization of Kievan Rus took place in several stages. In early 867, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople announced to other Orthodox patriarchs that the Rus', baptised by his bishop, took to Christianity with particular enthusiasm...

, it still played an important role in preserving the traditions of Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

, especially at times of domination by Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

Poland, and later the atheist

State atheism

State atheism is the official "promotion of atheism" by a government, sometimes combined with active suppression of religious freedom and practice...

Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

The city prospered again during the Russian industrial revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

in the late 19th century. In the turbulent period following the Russian Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

Kiev, caught in the middle of several conflicts, quickly went through becoming the capital of several short-lived Ukrainian states

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

. From 1921 the city was part of the Soviet Union, since 1934 as a capital of Soviet Ukraine

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

. In World War II

Eastern Front (World War II)

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of World War II between the European Axis powers and co-belligerent Finland against the Soviet Union, Poland, and some other Allies which encompassed Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945...

, the city was destroyed again, almost completely, but quickly recovered in the post-war years becoming the third most important city of the Soviet Union, the capital of the second most populous Soviet republic

Republics of the Soviet Union

The Republics of the Soviet Union or the Union Republics of the Soviet Union were ethnically-based administrative units that were subordinated directly to the Government of the Soviet Union...

. It now remains the capital of Ukraine, independent since 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union was the disintegration of the federal political structures and central government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , resulting in the independence of all fifteen republics of the Soviet Union between March 11, 1990 and December 25, 1991...

.

Kievan Rus' to Mongol Invasion (ca.839-1240)

The non-legendary time of the founding of the city is harder to ascertain. Scattered Slavic settlements existed in the area from the 6th century, but it is unclear whether any of them later developed into the city. Eighth century fortifications were built upon a Slavic settlement apparently abandoned some decades before. It is unclear whether these fortifications were built by the Slavs. Some western historians (i.e. Kevin Alan Brook) suppose that Kiev was founded by Khazars

Khazars

The Khazars were semi-nomadic Turkic people who established one of the largest polities of medieval Eurasia, with the capital of Atil and territory comprising much of modern-day European Russia, western Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, large portions of the northern Caucasus , parts of...

or Magyars, both Turkic peoples. Kiev is a Turkic place name (Küi = riverbank + ev = settlement). However, the Primary Chronicle

Primary Chronicle

The Primary Chronicle , Ruthenian Primary Chronicle or Russian Primary Chronicle, is a history of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113.- Three editions :...

(a main source of information about the early history of the area) mentions Slavic Kievans telling Askold and Dir

Askold and Dir

Askold and Dir are semi-legendary rulers of Kiev who, according to the Primary Chronicle, were two of Rurik's voivodes in 870s...

that they live without a local ruler and pay a tribute to Khazars in an event attributed to the 9th century. At least during the 8th and 9th centuries Kiev functioned as an outpost of the Khazar empire. A hill-fortress, called Sambat (Old Turkic for "high place") was built to defend the area.

According to the Hustyn Chronicle , Askold and Dir

Askold and Dir

Askold and Dir are semi-legendary rulers of Kiev who, according to the Primary Chronicle, were two of Rurik's voivodes in 870s...

(Haskuldr and Dyri) ruled Rus' Khaganate

Rus' Khaganate

Rus' khaganate is a historiographical term for the formative phase of the Rus state in the 9th century AD....

at least in 842. They were Varangian princes, probably of Swedish origin, not the Rurikids. According to the Annals of St. Bertin (Annales Bertiniani

Annales Bertiniani

Annales Bertiniani, or The Annals of St. Bertin, are late Carolingian, Frankish annals that were found in the monastery of St. Bertin, after which they are named. Their account is taken to cover the period 830-82, thus continuing the Royal Frankish Annals , from which, however, it has circulated...

) for the year 839, Louis the Pious, the Frankish emperor, came to the conclusion that the people called Rhos (qui se, id est gentem suum, Rhos vocari dicebant) belong to the gens of Swedes (eos gentis esse Sueonum).

According to Primary Chronicle

Primary Chronicle

The Primary Chronicle , Ruthenian Primary Chronicle or Russian Primary Chronicle, is a history of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113.- Three editions :...

, Oleg of Novgorod

Oleg of Novgorod

Oleg of Novgorod was a Varangian prince who ruled all or part of the Rus' people during the early 10th century....

(Helgi of Holmgard) conquered Kiev in 882. He was a descendant of Rurik

Rurik

Rurik, or Riurik , was a semilegendary 9th-century Varangian who founded the Rurik dynasty which ruled Kievan Rus and later some of its successor states, most notably the Tsardom of Russia, until 1598....

, a Varangian

Varangians

The Varangians or Varyags , sometimes referred to as Variagians, were people from the Baltic region, most often associated with Vikings, who from the 9th to 11th centuries ventured eastwards and southwards along the rivers of Eastern Europe, through what is now Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.According...

pagan chieftain.

DNA Testing of the Rurikid and Gediminid Princes The date given for Oleg's conquest of the town in the Primary Chronicle

Primary Chronicle

The Primary Chronicle , Ruthenian Primary Chronicle or Russian Primary Chronicle, is a history of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113.- Three editions :...

is uncertain, and some historians, such as Omeljan Pritsak

Omeljan Pritsak

Omeljan Pritsak was the first Mykhailo Hrushevsky Professor of Ukrainian History at Harvard University and the founder and first director of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.-Career:Pritsak began his academic career at the University of Lvov in interwar Poland where he...

and Constantine Zuckerman

Constantine Zuckerman

Constantine Zuckerman is a French-Jewish historian and Professor of Byzantine studies at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris.-Biography:...

, dispute this and maintain that Khazar rule continued as late as the 920s (documentary evidence exists to support this assertion — see the Kievian Letter

Kievian Letter

The Kievian Letter is an early 10th century letter written by a Khazarian Jewish community in Kiev. The letter, a Hebrew-language recommendation written on behalf of one member of their community, was part of an enormous collection brought to Cambridge by Solomon Schechter from the Cairo Geniza...

and Schechter Letter

Schechter Letter

The "Schechter Letter" was discovered in the Cairo Geniza by Solomon Schechter.-The Letter:The Schechter Letter is a communique from an unnamed Khazar author to an unidentified Jewish dignitary...

.)

From Oleg's seizure of the city until 1169 Kiev was the capital of Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus was a medieval polity in Eastern Europe, from the late 9th to the mid 13th century, when it disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of 1237–1240....

which was initially ruled by the Varangian Rurikid dynasty which was gradually Slavisized. The Kievan Grand Prince

Grand Prince

The title grand prince or great prince ranked in honour below emperor and tsar and above a sovereign prince .Grand duke is the usual and established, though not literal, translation of these terms in English and Romance languages, which do not normally use separate words for a "prince" who reigns...

s had traditional primacy over the other rulers of the land and the Kiev princehood was a valuable prize in the intra-dynastic rivalry. In 968 the city withstood a siege

Siege of Kiev (968)

The siege of Kiev by the Pechenegs in 968 is documented in the Primary Chronicle, whose account freely mixes historical details with folklore....

by the nomadic Pechenegs. In 988 by the order of the Grand Prince Vladimir I of Kiev

Vladimir I of Kiev

Vladimir Sviatoslavich the Great Old East Slavic: Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь Old Norse as Valdamarr Sveinaldsson, , Vladimir, , Volodymyr, was a grand prince of Kiev, ruler of Kievan Rus' in .Vladimir's father was the prince Sviatoslav of the Rurik dynasty...

(St. Vladimir or Volodymyr), the city residents baptized en-masse in the Dnieper river, an event the symbolized the Baptism of Kievan Rus'

Baptism of Kievan Rus'

The Christianization of Kievan Rus took place in several stages. In early 867, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople announced to other Orthodox patriarchs that the Rus', baptised by his bishop, took to Christianity with particular enthusiasm...

. Kiev reached the height of its position of political and cultural Golden Age

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology and legend and refers to the first in a sequence of four or five Ages of Man, in which the Golden Age is first, followed in sequence, by the Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and then the present, a period of decline...

in the middle of the 11th century under Vladimir's son Yaroslav the Wise. In 1051, prince Yaroslav assembled the bishops at St. Sophia Cathedral and appointed Hilarion

Hilarion of Kiev

Hilarion or Ilarion was the first non-Greek Metropolitan of Kiev. While there is not much verifiable information regarding Ilarion's biography, there are several aspects of his life which have come to be generally accepted....

, the first native of the Kievan Rus', as metropolitan bishop, that the decision reflects an anti-Byzantine bias. In 1054, the Kievan Church did not take note of the fact that the East–West Schism

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism of 1054, sometimes known as the Great Schism, formally divided the State church of the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western branches, which later became known as the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, respectively...

began, maintaining very good relations with Rome (i.e. prince Iziaslav I of Kiev

Iziaslav I of Kiev

Iziaslav Yaroslavich , Kniaz' , Veliki Kniaz of Kiev , King of Rus'...

's request to Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII

Pope St. Gregory VII , born Hildebrand of Sovana , was Pope from April 22, 1073, until his death. One of the great reforming popes, he is perhaps best known for the part he played in the Investiture Controversy, his dispute with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor affirming the primacy of the papal...

to extend to Kievan Rus' "the patronage of St. Peter", fulfilled by the pope by sending Iziaslav a crown from Rome in 1075).

The following years were marked by the rivalries of the competing princes of the dynasty and weakening of Kiev's political influence, although Kiev temporarily prevailed after the defeat of the Polotsk at the Battle on the river Nemiga

Battle on the river Nemiga

Battle on the Nemiga River was a combat of the Russian feudal period that occurred on March 3, 1067 on the Niamiha River. The description of the battle is the first reference to Minsk in the chronicles of Belarusian history.- Background:...

(1067) that also led to the burning of Minsk

Minsk

- Ecological situation :The ecological situation is monitored by Republican Center of Radioactive and Environmental Control .During 2003–2008 the overall weight of contaminants increased from 186,000 to 247,400 tons. The change of gas as industrial fuel to mazut for financial reasons has worsened...

. In 1146, the next Ruthenian bishop, Klym Smoliatych (Kliment of Smolensk), was appointed to serve as the Metropolitan of Kiev. In 1169 Andrei of Suzdal

Andrei Bogolyubsky

Prince Andrei I of Vladimir, commonly known as Andrey Bogolyubsky was a prince of Vladimir-Suzdal . He was the son of Yuri Dolgoruki, who proclaimed Andrei a prince in Vyshhorod . His mother was a Kipchak princess, khan Aepa's daughter.- Life :He left Vyshhorod in 1155 and moved to Vladimir...

sent an army against Mstislav Iziaslavich

Mstislav II of Kiev

Mstislav II Izyaslavich , Kniaz' of Pereyaslav, Volodymyr-Volynsky and Velikiy Kniaz of Kiev . Son of Izyaslav Mstislavich, Velikiy Kniaz' of Kiev....

and Kiev. Led by one of his sons, it consisted of the forces of eleven other princes, representing all three of the main branches of the dynasty against the fourth, Iziaslavichi of Volynia. The allies were victorious. The sack of Kiev allowed the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal

Vladimir-Suzdal

The Vladimir-Suzdal Principality or Vladimir-Suzdal Rus’ was one of the major principalities which succeeded Kievan Rus' in the late 12th century and lasted until the late 14th century. For a long time the Principality was a vassal of the Mongolian Golden Horde...

to take a leading role as the predecessor of the modern Russian state.

In 1203 Kiev was captured an burned by Prince Rurik Rostislavich

Rurik Rostislavich

Ruryk Rostislavich , Prince of Novgorod , Belgorod Kievsky, presently Bilohorodka , Grand Prince of Kiev , Prince of Chernigov...

. In the 1230s the city was sieged and ravaged by different Rus' princes several times. Finally, the Mongol-Tatar forces led by Batu Khan

Batu Khan

Batu Khan was a Mongol ruler and founder of the Ulus of Jochi , the sub-khanate of the Mongol Empire. Batu was a son of Jochi and grandson of Genghis Khan. His ulus was the chief state of the Golden Horde , which ruled Rus and the Caucasus for around 250 years, after also destroying the armies...

besieged, and then completely destroyed Kiev on December 6, 1240.

Golden Horde, 1241-1362

In the period between 1241 and 1362, princes of Kiev, both Rurikids and Lithuanian ones, were forced to accept Mongol/Tatar overlordship.In 1245, Petro Akerovych

Petro Akerovych

Peter Akerovych ; - was a Ukrainian Orthodox metropolitan .Metropolitan of Kiev from 1241 to 1245, descendant of a boyar family...

(of Ruthenian origin), the Metropolitan of Kiev, participated in the First Council of Lyon

First Council of Lyon

The First Council of Lyon was the thirteenth ecumenical council, as numbered by the Catholic Church, taking place in 1245.The First General Council of Lyon was presided over by Pope Innocent IV...

, where he informed Catholic Europe of the Mongol/Tatar threat. In 1299, Maximus

Maximus, Metropolitan of all Rus

Maximus was the Metropolitan of Kiev who moved the see of Russian metropolitans to Vladimir-on-Kliazma. In spite of the move, the metropolitans were officially known as "Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus'" until the establishment of autocephaly under Jonah in 1448.Maximus was of Greek origin...

(of Greek origin), the Metropolitan of Kiev, eventually moved the seat of the Metropolitanate from Kiev to Vladimir-on-Kliazma

Vladimir

Vladimir is a city and the administrative center of Vladimir Oblast, Russia, located on the Klyazma River, to the east of Moscow along the M7 motorway. Population:...

, keeping the title. Since 1320, Kiev was the site of a new Catholic bishopric, when Henry, a Dominican friar, was appointed the first missionary Bishop of Kiev. In early 1320s, a Lithuanian army led by Gediminas defeated a Slavic army led by Stanislav of Kiev at the Battle on the Irpen' River

Battle on the Irpen' River

The Battle on the Irpin River occurred in early 1320s between the armies of Gediminas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and Prince Stanislav of Kiev, allied with Oleg of Pereyaslavl' and Roman of Bryansk. On the small Irpin River about south west of Kiev, Gediminas resoundingly defeated Stanislav and...

, and conquered the city. The Tatars, who also claimed Kiev, retaliated in 1324–1325, so while Kiev was ruled by a Lithuanian prince, it had to pay a tribute to the Golden Horde

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde was a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate that formed the north-western sector of the Mongol Empire...

.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 1362-1569

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state from the 12th /13th century until 1569 and then as a constituent part of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1791 when Constitution of May 3, 1791 abolished it in favor of unitary state. It was founded by the Lithuanians, one of the polytheistic...

after the Battle at Blue Waters in 1362, when Algirdas

Algirdas

Algirdas was a monarch of medieval Lithuania. Algirdas ruled the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1345 to 1377, which chiefly meant monarch of Lithuanians and Ruthenians...

, Grand Duke of Lithuania, beat a Golden Horde

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde was a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate that formed the north-western sector of the Mongol Empire...

army. During the period between 1262 and 1471, Kiev has been ruled by Lithuanian princes from different families. By the order of Casimir Jagiellon, the Principality of Kiev was abolished and the Kiev Voivodship was established in 1471. Lithuanian statesman Martynas Goštautas was appointed as the first voivode of Kiev the same year; his appointment was met by hostility from locals.

The city was frequently attacked by Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group that originally resided in Crimea. They speak the Crimean Tatar language...

and in 1482 was destroyed again by Crimean Khan

Crimean Khanate

Crimean Khanate, or Khanate of Crimea , was a state ruled by Crimean Tatars from 1441 to 1783. Its native name was . Its khans were the patrilineal descendants of Toqa Temür, the thirteenth son of Jochi and grandson of Genghis Khan...

Meñli I Giray

Meñli I Giray

Meñli I Giray , also spelled as Mengli I Giray, was a khan of the Crimean Khanate and the sixth son of the khanate founder Haci I Giray....

. Despite its little remaining political significance, the city still played an important role as a seat of the local Orthodox metropolitan

Metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan, pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis; that is, the chief city of a historical Roman province, ecclesiastical province, or regional capital.Before the establishment of...

. However, starting in 1494 the city's local autonomy (Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg Rights or Magdeburg Law were a set of German town laws regulating the degree of internal autonomy within cities and villages granted by a local ruler. Modelled and named after the laws of the German city of Magdeburg and developed during many centuries of the Holy Roman Empire, it was...

) gradually increased in a series of acts of Lithuanian Grand Dukes and Polish Kings which was finalized by 1516 charter granted by Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I of Poland , of the Jagiellon dynasty, reigned as King of Poland and also as the Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until 1548...

.

Kiev had a Jewish community of some significance in the early sixteenth century. The tolerant Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus I was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the only son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548...

granted equal rights to Kiev's Jews on the grounds that they paid the same taxes as Podil's burghers. Polish sponsorship of Jewish settlement in Kiev added fuel to the conflict that already existed between the Orthodox and Catholic churches.

Kingdom of Poland, 1569-1667

In 1569, the Union of LublinUnion of Lublin

The Union of Lublin replaced the personal union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with a real union and an elective monarchy, since Sigismund II Augustus, the last of the Jagiellons, remained childless after three marriages. In addition, the autonomy of Royal Prussia was...

that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

, Kiev with other Ukrainian territories was transferred to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, and it became a capital of the Kiev Voivodeship. Its role of Orthodox center strengthened due to expansion of Roman Catholicism under Polish rule. In 1632, Peter Mogila the Orthodox Metropolitan

Metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan, pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis; that is, the chief city of a historical Roman province, ecclesiastical province, or regional capital.Before the establishment of...

of Kiev and Galicia established the Kiev Mogila Academy, an educational institution aimed to preserve and develop Ukrainian culture and Orthodox faith despite Polish Catholic oppression. Although ruled by the church, the academy provided students with educational standards close to universities of Western Europe (including multilingual training) and became the foremost educational center, both religious and secular.

In 1648 Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

's cossacks triumphantly entered Kiev in the course of their uprising

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, was a Cossack rebellion in the Ukraine between the years 1648–1657 which turned into a Ukrainian war of liberation from Poland...

establishing the rule of their Cossack Hetmanate

Cossack Hetmanate

The Hetmanate or Zaporizhian Host was the Ruthenian Cossack state in the Central Ukraine between 1649 and 1782.The Hetmanate was founded by first Ukrainian hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky during the Khmelnytsky Uprising . In 1654 it pledged its allegiance to Muscovy during the Council of Pereyaslav,...

in the city. The Zaporizhian Host had a special status within the newly formed political entity. The complete sovereignty of Hetmanate did not last long as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

refused to recognize it and resumed hostilities. In January 1654 Khmelnytsky decided to sign the Treaty of Pereyaslav

Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Treaty of Pereyaslav is known in history more as the Council of Pereiaslav.Council of Pereyalslav was a meeting between the representative of the Russian Tsar, Prince Vasili Baturlin who presented a royal decree, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky as the leader of Cossack Hetmanate. During the council...

with Tsardom of Russia

Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia was the name of the centralized Russian state from Ivan IV's assumption of the title of Tsar in 1547 till Peter the Great's foundation of the Russian Empire in 1721.From 1550 to 1700, Russia grew 35,000 km2 a year...

to obtain a military support against the Polish Crown. However, in November 1656 the Muscovites concluded the Truce of Vilna

Truce of Vilna

Truce/Treaty of Vilna or Truce/Treaty of Niemieża was a treaty signed at Niemieża near Vilnius on 3 November 1656 between Tsardom of Russia and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, introducing a truce during the Russo-Polish War and an anti-Swedish alliance in the contemporary Second Northern War...

with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was approved by Bohdan Khmelnytsky. After his death, in the atmosphere of sharp conflicts his successor became Ivan Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky was a hetman of the Ukrainian Cossacks during three years of the Russo-Polish War . He was the successor to the famous hetman and rebel leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky...

who signed the Treaty of Hadiach

Treaty of Hadiach

The Treaty of Hadiach was a treaty signed on 16 September 1658 in Hadiach between representatives of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Cossacks...

. It was ratified by the Crown in a limited version. According to Vyhovsky original intention, Kiev was to become the capital of the Duchy of Ruthenia on the limited federate rights within the Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth. However, this part of the Treaty was removed during the ratification. In the meantime, Vyhovsky's opponent Yuri Khmelnytsky signed the Second Treaty of Pereyaslav in October 1659 with a representative of Russian tsar.

Russian Empire, 1667 to 1917 Revolution

On January, 31, 1667, the Truce of Andrusovo was concluded, in which the Polish-Lithuanian CommonwealthPolish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

ceded Smolensk, Severia and Chernigov, and, on paper only for a period of two years, the city of Kiev to the Tsardom of Russia

Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia was the name of the centralized Russian state from Ivan IV's assumption of the title of Tsar in 1547 till Peter the Great's foundation of the Russian Empire in 1721.From 1550 to 1700, Russia grew 35,000 km2 a year...

. Finally, the Eternal Peace of 1686 acknowledged the status quo, and put Kiev under the control of Russia for the centuries to come with the territory, slowly losing the autonomy which was finally abolished in 1775 by the Empress Catherine the Great. Noone of Polish-Russian treaties concerning Kiev has been never ratified.

In 1834, St. Vladimir University

Kiev University

Taras Shevchenko University or officially the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv , colloquially known in Ukrainian as KNU is located in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine. It is the third oldest university in Ukraine after the University of Lviv and Kharkiv University. Currently, its structure...

was established in Kiev (now known as National Taras Shevchenko University of Kiev). The great Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko

Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko -Life:Born into a serf family of Hryhoriy Ivanovych Shevchenko and Kateryna Yakymivna Shevchenko in the village of Moryntsi, of Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire Shevchenko was orphaned at the age of eleven...

cooperated with its geography department as a field researcher and editor. However, the Magdeburg Law existed in Kiev till that year, when it was abolished by the Decree of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I , was the Emperor of Russia from 1825 until 1855, known as one of the most reactionary of the Russian monarchs. On the eve of his death, the Russian Empire reached its historical zenith spanning over 20 million square kilometers...

on December 23, 1834.

According to the Russian census of 1874, of Kiev's 127,251 people 38,553 (39%) spoke "Little Russian" (the Ukrainian language), 12,917 (11 percent) spoke Yiddish, 9,736 (10 percent) spoke Great Russian, 7,863 (6 percent) spoke Polish, and 2,583 (2 percent) spoke German. 48,437 (or 49%) of Kiev's residents were listed as speaking "generally Russian speech (obshcherusskoe narechie)." Such people were typically Ukrainians and Poles who could speak aenough Russian to be counted as Russian-speaking.

From the late 18th century until the late 19th century, city life was increasingly dominated by Russian military and ecclesiastical concerns. Russian Orthodox Church

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

institutions formed a significant part of Kiev's infrastructure and business activity at that time. In the winter 1845-1846, the famous historian, Mykola Kostomarov (Nikolay Kostomarov

Nikolay Kostomarov

Nikolay Ivanovich Kostomarov , of mixed Russian and Ukrainian origin, is one of the most distinguished Russian and Ukrainian historians, a Professor of History at the Kiev University and later at the St...

in Russian), founded the secret political society, the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

The Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius was a short-lived secret political society that existed in Kiev, Ukraine, at the time a part of the Russian Empire...

whose members put forward the idea of federation

Federation

A federation , also known as a federal state, is a type of sovereign state characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions united by a central government...

of free Slavic people with Ukrainians as a distinct group among them rather than a part of the Russian nation. The Brotherhood's ideology was a synthesis of programmes of three movements: Ukrainian autonomists, Polish democrats, and Russian Decembrists in Ukraine. The society was quickly suppressed by the Tsarist authorities in March–April 1847.

Following the gradual loss of Ukraine's autonomy and suppression of the local Ukrainian and Polish cultures, Kiev experienced growing Russification

Russification

Russification is an adoption of the Russian language or some other Russian attributes by non-Russian communities...

in the 19th century by means of Russian

Russians

The Russian people are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Russia, speaking the Russian language and primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries....

migration, administrative actions (the Valuev Circular of 1863), and social modernization

Modernization

In the social sciences, modernization or modernisation refers to a model of an evolutionary transition from a 'pre-modern' or 'traditional' to a 'modern' society. The teleology of modernization is described in social evolutionism theories, existing as a template that has been generally followed by...

. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city was dominated by Russian

Russian language

Russian is a Slavic language used primarily in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It is an unofficial but widely spoken language in Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Turkmenistan and Estonia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics...

-speaking population, while the lower classes retained Ukrainian folk culture to a significant extent. According to the census of 1897, of Kiev's approximately 240,000 people approximately 56% of the population spoke the Russian language, 23% spoke the Ukrainian language, 12.5% spoke Yiddish, 7% spoke Polish and 1% spoke the Belarussian language. Despite the Russian cultural dominance in the city, enthusiasts among ethnic Ukrainian nobles, military and merchants made recurrent attempts to preserve native culture in Kiev (by clandestine book-printing, amateur theater, folk studies etc.).

During the Russian industrial revolution in the late 19th century, Kiev became an important trade and transportation center of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, specializing in sugar and grain export by railroad and on the Dnieper river. As of 1900, the city also became a significant industrial center, having a population of 250,000. Landmarks of that period include the railway infrastructure, the foundation of numerous educational and cultural facilities as well as notable architectural monuments (mostly merchant-oriented, i.e. Brodsky Synagogue

Brodsky Synagogue

-History:The synagogue was built between 1897 and 1898. A merchant named Lazar Brodsky financed its construction. The synagogue was designed in Moorish style by Georgij Szlejfer....

).

At that time, a large Jewish community emerged in Kiev, developing its own ethnic culture and business interests. This was stimulated by the prohibition of Jewish settlement in Russia proper (Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

and Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

) — as well as further eastwards. Expelled from Kiev in 1654, Jews probably were not able to settle in the city again until the early 1790s. On December 2, 1827, Nicolas I of Russia expelled Kiev's seven hundred Jews. In 1836, the Pale of Settlement

Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement was the term given to a region of Imperial Russia, in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed, and beyond which Jewish permanent residency was generally prohibited...

banned Jews from Kiev as well, fencing off the city's districts from the Jewish population. Thus, at mid-century Jewish merchants who came to the fairs could stay in Kiev for up to six months. In 1881 and 1905, notorious pogroms

Kiev Pogrom (1905)

The Kiev pogrom of October 18-October 20 came as a result of the collapse of the city hall meeting of October 18, 1905 in Kiev in the Russian Empire. Consequently, a mob was drawn into the streets...

in the city resulted in the death of about 100 Jews.

The development of aviation (both military and amateur) became another notable mark of distinction of early 1900s Kiev. Prominent aviation figures of that period include Kievites Pyotr Nesterov

Pyotr Nesterov

Pyotr Nikolayevich Nesterov was a Russian pilot, an aircraft technical designer and an aerobatics pioneer.-Life and career:The son of a military academy teacher, Pyotr Nesterov decided to choose a military career. In August 1904 he left the military school in Nizhny Novgorod and went to the...

(well-known aerobatics

Aerobatics

Aerobatics is the practice of flying maneuvers involving aircraft attitudes that are not used in normal flight. Aerobatics are performed in airplanes and gliders for training, recreation, entertainment and sport...

pioneer) and Igor Sikorsky

Igor Sikorsky

Igor Sikorsky , born Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky was a Russian American pioneer of aviation in both helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft...

. The world's first helicopter

Helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by one or more engine-driven rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forwards, backwards, and laterally...

was built and tested in Kiev by Sikorsky. In 1892 the first electric tram line

Kiev tram

The Kiev Tramway is a tram network which serves the Ukrainian capital Kiev. The system was the first electric tramway in the former Russian Empire and the third one in Europe after the Berlin Straßenbahn and the Budapest tramway. The system currently consists of 139.9 km of track, including...

of the Russian Empire was established in Kiev.

Independence and Civil War, 1917-1921

Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiyovych Hrushevsky was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian, and statesman, one of the most important figures of the Ukrainian national revival of the early 20th century...

, was established in the city. Later that year, Ukrainian autonomy was declared.

On 7 November 1917 it was transformed into an independent Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

with the capital in Kiev. During this short period of independence, Kiev experienced rapid growth of its cultural and political status. An Academy of Sciences and professional Ukrainian

Ukrainian language

Ukrainian is a language of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is the official state language of Ukraine. Written Ukrainian uses a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet....

-language theaters and libraries were established by the new government.

Later Kiev became a war zone in the lasting and bloody struggle between Ukrainian, Polish and Russian Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

governments in the time of Russian Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

, Ukrainian-Soviet War

Ukrainian-Soviet War

The Ukrainian–Soviet War of 1917–21 was a military conflict between the Ukrainian People's Republic and pro-Bolshevik forces for the control of Ukraine after the dissolution of the Russian Empire.-Background:...

, Polish-Ukrainian War

Polish-Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918 and 1919 was a conflict between the forces of the Second Polish Republic and West Ukrainian People's Republic for the control over Eastern Galicia after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary.-Background:...

and Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic—four states in post–World War I Europe...

.

Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1918/1921-1941

Kiev Arsenal January Uprising

Kiev Arsenal January Uprising, sometimes called simply the January Uprising or the January Rebellion , was the Bolshevik organized workers' armed revolt that started on January 29, 1918 at the Kiev Arsenal factory during the Ukrainian-Soviet War....

" on the 29th 1918, saw Bolshevist troops enter the city and declare a Soviet Coup d'etat. The Kiev garrison joined with the Soviets and deposed the Rada. Odoevsky

Alexander Odoevsky

Alexander Ivanovich Odoevsky was a Russian poet and playwright, one of the leading figures of the 1825 Decembrist revolt...

attempted to form a new government but was arrested. The Bolshevik

Bolshevik