History of cryptography

Encyclopedia

The history of cryptography

begins thousands of years ago. Until recent decades, it has been the story of what might be called classic cryptography — that is, of methods of encryption

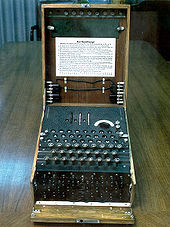

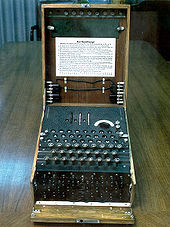

that use pen and paper, or perhaps simple mechanical aids. In the early 20th century, the invention of complex mechanical and electromechanical machines, such as the Enigma rotor machine

, provided more sophisticated and efficient means of encryption; and the subsequent introduction of electronics and computing has allowed elaborate schemes of still greater complexity, most of which are entirely unsuited to pen and paper.

The development of cryptography

has been paralleled by the development of cryptanalysis

— the "breaking" of codes and cipher

s. The discovery and application, early on, of frequency analysis

to the reading of encrypted communications has, on occasion, altered the course of history. Thus the Zimmermann Telegram

triggered the United States' entry into World War I; and Allied reading of Nazi Germany

's ciphers shortened World War II, in some evaluations by as much as two years.

Until the 1970s, secure cryptography was largely the preserve of governments. Two events have since brought it squarely into the public domain: the creation of a public encryption standard (DES

), and the invention of public-key cryptography

.

carved into monuments from the Old Kingdom of Egypt circa 1900 BC. These are not thought to be serious attempts at secret communications, however, but rather to have been attempts at mystery, intrigue, or even amusement for literate onlookers. These are examples of still other uses of cryptography, or of something that looks (impressively if misleadingly) like it. Some clay tablet

s from Mesopotamia somewhat later are clearly meant to protect information—one dated near 1500 BC was found to encrypt a craftsman's recipe for pottery glaze, presumably commercially valuable. Later still, Hebrew

scholars made use of simple monoalphabetic substitution ciphers (such as the Atbash cipher) beginning perhaps around 500 to 600 BC.

The ancient Greeks are said to have known of ciphers (e.g., the scytale

The ancient Greeks are said to have known of ciphers (e.g., the scytale

transposition cipher

claimed to have been used by the Sparta

n military). Herodotus

tells us of secret messages physically concealed beneath wax on wooden tablets or as a tattoo on a slave's head concealed by regrown hair, though these are not properly examples of cryptography per se as the message, once known, is directly readable; this is known as steganography

. Another Greek method was developed by Polybius

(now called the "Polybius Square"). The Romans

knew something of cryptography (e.g., the Caesar cipher

and its variations).

It was probably religiously motivated textual analysis of the Qur'an

It was probably religiously motivated textual analysis of the Qur'an

which led to the invention of the frequency analysis technique for breaking monoalphabetic substitution cipher

s, possibly by Al-Kindi

, an Arab mathematician, sometime around AD 800 (Ibrahim Al-Kadi −1992). It was the most fundamental cryptanalytic advance until WWII. Al-Kindi wrote a book on cryptography entitled Risalah fi Istikhraj al-Mu'amma (Manuscript for the Deciphering Cryptographic Messages), in which he described the first cryptanalysis techniques, including some for polyalphabetic cipher

s, cipher classification, Arabic phonetics and syntax, and, most importantly, gave the first descriptions on frequency analysis. He also covered methods of encipherments, cryptanalysis of certain encipherments, and statistical analysis of letters and letter combinations in Arabic.

Ahmad al-Qalqashandi

(1355–1418) wrote the Subh al-a 'sha, a 14-volume encyclopedia which included a section on cryptology. This information was attributed to Taj ad-Din Ali ibn ad-Duraihim ben Muhammad ath-Tha 'alibi al-Mausili who lived from 1312 to 1361, but whose writings on cryptography have been lost. The list of ciphers in this work included both substitution

and transposition

, and for the first time, a cipher with multiple substitutions for each plaintext

letter. Also traced to Ibn al-Duraihim is an exposition on and worked example of cryptanalysis, including the use of tables of letter frequencies

and sets of letters which can not occur together in one word.

Essentially all ciphers remained vulnerable to the cryptanalytic technique of frequency analysis until the development of the polyalphabetic cipher, and many remained so thereafter. The polyalphabetic cipher was most clearly explained by Leon Battista Alberti around the year 1467, for which he was called the "father of Western cryptology". Johannes Trithemius

, in his work Poligraphia, invented the tabula recta

, a critical component of the Vigenère cipher. The French cryptographer Blaise de Vigenere

devised a practical poly alphabetic system which bears his name, the Vigenère cipher

.

In Europe, cryptography became (secretly) more important as a consequence of political competition and religious revolution. For instance, in Europe during and after the Renaissance

, citizens of the various Italian states—the Papal States

and the Roman Catholic Church included—were responsible for rapid proliferation of cryptographic techniques, few of which reflect understanding (or even knowledge) of Alberti's polyalphabetic advance. 'Advanced ciphers', even after Alberti, weren't as advanced as their inventors / developers / users claimed (and probably even themselves believed). They were regularly broken. This over-optimism may be inherent in cryptography for it was then, and remains today, fundamentally difficult to accurately know how vulnerable your system actually is. In the absence of knowledge, guesses and hopes, as may be expected, are common.

Cryptography, cryptanalysis

, and secret agent/courier betrayal featured in the Babington plot

during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I

which led to the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. An encrypted message from the time of the Man in the Iron Mask

(decrypted just prior to 1900 by Étienne Bazeries

) has shed some, regrettably non-definitive, light on the identity of that real, if legendary and unfortunate, prisoner.

Outside of Europe, after the end of the Muslim Golden Age at the hand of the Mongols, cryptography remained comparatively undeveloped. Cryptography in Japan seems not to have been used until about 1510, and advanced techniques were not known until after the opening of the country to the West beginning in the 1860s. During the 1920s, it was Polish naval officers who assisted the Japanese military with code and cipher development.

(the science of finding weaknesses in crypto systems). Examples of the latter include Charles Babbage

's Crimean War

era work on mathematical cryptanalysis of polyalphabetic cipher

s, redeveloped and published somewhat later by the Prussian Friedrich Kasiski

. Understanding of cryptography at this time typically consisted of hard-won rules of thumb; see, for example, Auguste Kerckhoffs

' cryptographic writings in the latter 19th century. Edgar Allan Poe

used systematic methods to solve ciphers in the 1840s. In particular he placed a notice of his abilities in the Philadelphia paper Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger, inviting submissions of ciphers, of which he proceeded to solve almost all. His success created a public stir for some months. He later wrote an essay on methods of cryptography which proved useful as an introduction for novice British cryptanalysts attempting to break German codes and ciphers during World War I, and a famous story, The Gold-Bug

, in which cryptanalysis was a prominent element.

Cryptography, and its misuse, were involved in the plotting which led to the execution of Mata Hari

and in the conniving which led to the travesty of Dreyfus' conviction

and imprisonment, both in the early 20th century. Fortunately, cryptographers were also involved in exposing the machinations which had led to Dreyfus' problems; Mata Hari, in contrast, was shot.

In World War I the Admiralty

's Room 40

broke German naval codes and played an important role in several naval engagements during the war, notably in detecting major German sorties into the North Sea

that led to the battles of Dogger Bank

and Jutland

as the British fleet was sent out to intercept them. However its most important contribution was probably in decrypting

the Zimmermann Telegram

, a cable from the German Foreign Office sent via Washington to its ambassador

Heinrich von Eckardt

in Mexico which played a major part in bringing the United States into the war.

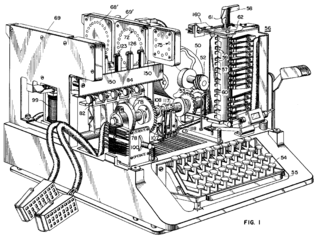

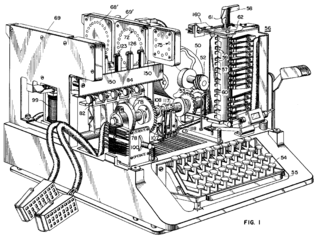

In 1917, Gilbert Vernam

proposed a teleprinter cipher in which a previously-prepared key, kept on paper tape, is combined character by character with the plaintext message to produce the cyphertext. This led to the development of electromechanical devices as cipher machines, and to the only unbreakable cypher, the one time pad.

Mathematical methods proliferated in the period prior to World War II (notably in William F. Friedman

's application of statistical techniques to cryptanalysis and cipher development and in Marian Rejewski

's initial break into the German Army's version of the Enigma system) in 1932.

By World War II, mechanical and electromechanical cipher machines

By World War II, mechanical and electromechanical cipher machines

were in wide use, although—where such machines were impractical—manual systems continued in use. Great advances were made in both cipher design and cryptanalysis

, all in secrecy. Information about this period has begun to be declassified as the official British 50-year secrecy period has come to an end, as US archives have slowly opened, and as assorted memoirs and articles have appeared.

The Germans made heavy use, in several variants, of an electromechanical rotor machine

known as Enigma

. Mathematician Marian Rejewski

, at Poland's Cipher Bureau

, in December 1932 deduced the detailed structure of the German Army Enigma, using mathematics and limited documentation supplied by Captain Gustave Bertrand

of French military intelligence

. This was the greatest breakthrough in cryptanalysis in a thousand years and more, according to historian David Kahn. Rejewski and his mathematical Cipher Bureau colleagues, Jerzy Różycki

and Henryk Zygalski

, continued reading Enigma and keeping pace with the evolution of the German Army machine's components and encipherment procedures. As the Poles' resources became strained by the changes being introduced by the Germans, and as war loomed, the Cipher Bureau

, on the Polish General Staff

's instructions, on 25 July 1939, at Warsaw

, initiated French and British intelligence representatives into the secrets of Enigma decryption.

Soon after World War II broke out on 1 September 1939, key Cipher Bureau

personnel were evacuated southeastward; on 17 September, as the Soviet Union

attacked Poland, they crossed into Romania

. From there they reached Paris, France; at PC Bruno

, near Paris, they continued breaking Enigma, collaborating with British cryptologists at Bletchley Park

as the British got up to speed on breaking Enigma. In due course, the British cryptographers - whose ranks included many chess masters and mathematics dons such as Gordon Welchman

, Max Newman

, and Alan Turing

(the conceptual founder of modern computing

) - substantially advanced the scale and technology of Enigma

decryption.

At the end of the War, on 19 April 1945, Britain's top military officers were told that they could never reveal that the German Enigma cipher had been broken because it would give the defeated enemy the chance to say they "were not well and fairly beaten".

US Navy cryptographers (with cooperation from British and Dutch cryptographers after 1940) broke into several Japanese Navy

crypto systems. The break into one of them, JN-25

, famously led to the US victory in the Battle of Midway

; and to the publication of that fact in the Chicago Tribune

shortly after the battle, though the Japanese seem not to have noticed for they kept using the JN-25 system. A US Army group, the SIS

, managed to break the highest security Japanese diplomatic cipher system (an electromechanical 'stepping switch' machine called Purple by the Americans) even before WWII began. The Americans referred to the intelligence resulting from cryptanalysis, perhaps especially that from the Purple machine, as 'Magic'. The British eventually settled on 'Ultra' for intelligence resulting from cryptanalysis, particularly that from message traffic protected by the various Enigmas. An earlier British term for Ultra had been 'Boniface' in an attempt to suggest, if betrayed, that it might have an individual agent as a source.

The German military also deployed several mechanical attempts at a one-time pad

. Bletchley Park called them the Fish cipher

s, and Max Newman

and colleagues designed and deployed the Heath Robinson

, and then the world's first programmable digital electronic computer, the Colossus

, to help with their cryptanalysis. The German Foreign Office began to use the one-time pad

in 1919; some of this traffic was read in WWII partly as the result of recovery of some key material in South America that was discarded without sufficient care by a German courier.

The Japanese Foreign Office used a locally developed electrical stepping switch based system (called Purple by the US), and also had used several similar machines for attaches in some Japanese embassies. One of these was called the 'M-machine' by the US, another was referred to as 'Red'. All were broken, to one degree or another, by the Allies.

Allied

Allied

cipher machines used in WWII included the British TypeX

and the American SIGABA

; both were electromechanical rotor designs similar in spirit to the Enigma, albeit with major improvements. Neither is known to have been broken by anyone during the War. The Poles used the Lacida

machine, but its security was found to be less than intended (by Polish Army cryptographers in the UK), and its use was discontinued. US troops in the field used the M-209

and the still less secure M-94

family machines. British SOE

agents initially used 'poem ciphers' (memorized poems were the encryption/decryption keys), but later in the War, they began to switch

to one-time pad

s.

The VIC cipher

(used at least until 1957 in connection with Rudolf Abel's NY spy ring) was a very complex hand cipher, and is claimed to be the most complicated known to have been used by the Soviets, according to David Kahn in Kahn on Codes. For the decrypting of Soviet ciphers (particularly when one-time pads were reused), see Venona project

.

in the Bell System Technical Journal

and a little later the book The Mathematical Theory of Communication (expanding on an earlier article "A Mathematical Theory of Communication

") with Warren Weaver

. Both included results from his WWII work. These, in addition to his other works on information and communication theory

, established a solid theoretical basis for cryptography and also for much of cryptanalysis. And with that, cryptography more or less disappeared into secret government communications organizations such as NSA, GCHQ, and their equivalents elsewhere. Very little work was again made public until the mid 1970s, when everything changed.

in the U.S. Federal Register on 17 March 1975. The proposed DES cipher was submitted by a research group at IBM, at the invitation of the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST), in an effort to develop secure electronic communication facilities for businesses such as banks and other large financial organizations. After 'advice' and modification by NSA, acting behind the scenes, it was adopted and published as a Federal Information Processing Standard

Publication in 1977 (currently at FIPS 46-3). DES was the first publicly accessible cipher to be 'blessed' by a national agency such as NSA. The release of its specification by NBS stimulated an explosion of public and academic interest in cryptography.

The aging DES was officially replaced by the Advanced Encryption Standard

(AES) in 2001 when NIST announced FIPS 197. After an open competition, NIST selected Rijndael, submitted by two Belgian cryptographers, to be the AES. DES, and more secure variants of it (such as Triple DES

), are still used today, having been incorporated into many national and organizational standards. However, its 56-bit key-size has been shown to be insufficient to guard against brute force attack

s (one such attack, undertaken by the cyber civil-rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation

in 1997, succeeded in 56 hours.) As a result, use of straight DES encryption is now without doubt insecure for use in new cryptosystem designs, and messages protected by older cryptosystems using DES, and indeed all messages sent since 1976 using DES, are also at risk. Regardless of DES' inherent quality, the DES key size (56-bits) was thought to be too small by some even in 1976, perhaps most publicly by Whitfield Diffie

. There was suspicion that government organizations even then had sufficient computing power to break DES messages; clearly others have achieved this capability.

and Martin Hellman

. It introduced a radically new method of distributing cryptographic keys, which went far toward solving one of the fundamental problems of cryptography, key distribution, and has become known as Diffie-Hellman key exchange

. The article also stimulated the almost immediate public development of a new class of enciphering algorithms, the asymmetric key algorithms.

Prior to that time, all useful modern encryption algorithms had been symmetric key algorithms, in which the same cryptographic key is used with the underlying algorithm by both the sender and the recipient, who must both keep it secret. All of the electromechanical machines used in WWII were of this logical class, as were the Caesar

and Atbash

ciphers and essentially all cipher systems throughout history. The 'key' for a code is, of course, the codebook, which must likewise be distributed and kept secret, and so shares most of the same problems in practice.

Of necessity, the key in every such system had to be exchanged between the communicating parties in some secure way prior to any use of the system (the term usually used is 'via a secure channel

') such as a trustworthy courier with a briefcase handcuffed to a wrist, or face-to-face contact, or a loyal carrier pigeon. This requirement is never trivial and very rapidly becomes unmanageable as the number of participants increases, or when secure channels aren't available for key exchange, or when, as is sensible cryptographic practice, keys are frequently changed. In particular, if messages are meant to be secure from other users, a separate key is required for each possible pair of users. A system of this kind is known as a secret key, or symmetric key cryptosystem. D-H key exchange (and succeeding improvements and variants) made operation of these systems much easier, and more secure, than had ever been possible before in all of history.

In contrast, asymmetric key encryption uses a pair of mathematically related keys, each of which decrypts the encryption performed using the other. Some, but not all, of these algorithms have the additional property that one of the paired keys cannot be deduced from the other by any known method other than trial and error. An algorithm of this kind is known as a public key or asymmetric key system. Using such an algorithm, only one key pair is needed per user. By designating one key of the pair as private (always secret), and the other as public (often widely available), no secure channel is needed for key exchange. So long as the private key stays secret, the public key can be widely known for a very long time without compromising security, making it safe to reuse the same key pair indefinitely.

For two users of an asymmetric key algorithm to communicate securely over an insecure channel, each user will need to know their own public and private keys as well as the other user's public key. Take this basic scenario: Alice and Bob

each have a pair of keys they've been using for years with many other users. At the start of their message, they exchange public keys, unencrypted over an insecure line. Alice then encrypts a message using her private key, and then re-encrypts that result using Bob's public key. The double-encrypted message is then sent as digital data over a wire from Alice to Bob. Bob receives the bit stream and decrypts it using his own private key, and then decrypts that bit stream using Alice's public key. If the final result is recognizable as a message, Bob can be confident that the message actually came from someone who knows Alice's private key (presumably actually her if she's been careful with her private key), and that anyone eavesdropping on the channel will need Bob's private key in order to understand the message.

Asymmetric algorithms rely for their effectiveness on a class of problems in mathematics called one-way functions, which require relatively little computational power to execute, but vast amounts of power to reverse, if reversal is possible at all. A classic example of a one-way function is multiplication of very large prime numbers. It's fairly quick to multiply two large primes, but very difficult to find the factors of the product of two large primes. Because of the mathematics of one-way functions, most possible keys are bad choices as cryptographic keys; only a small fraction of the possible keys of a given length are suitable, and so asymmetric algorithms require very long keys to reach the same level of security provided by relatively shorter symmetric keys. The need to both generate the key pairs, and perform the encryption/decryption operations make asymmetric algorithms computationally expensive, compared to most symmetric algorithms. Since symmetric algorithms can often use any sequence of (random, or at least unpredictable) bits as a key, a disposable session key can be quickly generated for short-term use. Consequently, it is common practice to use a long asymmetric key to exchange a disposable, much shorter (but just as strong) symmetric key. The slower asymmetric algorithm securely sends a symmetric session key, and the faster symmetric algorithm takes over for the remainder of the message.

Asymmetric key cryptography, Diffie-Hellman key exchange, and the best known of the public key / private key algorithms (i.e., what is usually called the RSA algorithm), all seem to have been independently developed at a UK intelligence agency before the public announcement by Diffie and Hellman in 1976. GCHQ has released documents claiming they had developed public key cryptography before the publication of Diffie and Hellman's paper. Various classified papers were written at GCHQ during the 1960s and 1970s which eventually led to schemes essentially identical to RSA encryption and to Diffie-Hellman key exchange in 1973 and 1974. Some of these have now been published, and the inventors (James H. Ellis

, Clifford Cocks

, and Malcolm Williamson) have made public (some of) their work.

is subject to restrictions. Until 1996 export from the U.S. of cryptography using keys longer than 40 bits (too small to be very secure against a knowledgeable attacker) was sharply limited. As recently as 2004, former FBI Director Louis Freeh

, testifying before the 9/11 Commission

, called for new laws against public use of encryption.

One of the most significant people favoring strong encryption for public use was Phil Zimmermann

. He wrote and then in 1991 released PGP

(Pretty Good Privacy), a very high quality crypto system. He distributed a freeware version of PGP when he felt threatened by legislation then under consideration by the US Government that would require backdoors to be included in all cryptographic products developed within the US. His system was released worldwide shortly after he released it in the US, and that began a long criminal investigation of him by the US Government Justice Department for the alleged violation of export restrictions. The Justice Department eventually dropped its case against Zimmermann, and the freeware distribution of PGP has continued around the world. PGP even eventually became an open Internet standard (RFC 2440 or OpenPGP).

encryption scheme WEP

, the Content Scrambling System used for encrypting and controlling DVD use, the A5/1

and A5/2

ciphers used in GSM cell phones, and the CRYPTO1 cipher used in the widely deployed MIFARE

Classic smart card

s from NXP Semiconductors, a spun off division of Philips Electronics. All of these are symmetric ciphers. Thus far, not one of the mathematical ideas underlying public key cryptography has been proven to be 'unbreakable', and so some future mathematical analysis advance might render systems relying on them insecure. While few informed observers foresee such a breakthrough, the key size recommended for security as best practice keeps increasing as increased computing power required for breaking codes becomes cheaper and more available.

Cryptography

Cryptography is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of third parties...

begins thousands of years ago. Until recent decades, it has been the story of what might be called classic cryptography — that is, of methods of encryption

Encryption

In cryptography, encryption is the process of transforming information using an algorithm to make it unreadable to anyone except those possessing special knowledge, usually referred to as a key. The result of the process is encrypted information...

that use pen and paper, or perhaps simple mechanical aids. In the early 20th century, the invention of complex mechanical and electromechanical machines, such as the Enigma rotor machine

Rotor machine

In cryptography, a rotor machine is an electro-mechanical device used for encrypting and decrypting secret messages. Rotor machines were the cryptographic state-of-the-art for a prominent period of history; they were in widespread use in the 1920s–1970s...

, provided more sophisticated and efficient means of encryption; and the subsequent introduction of electronics and computing has allowed elaborate schemes of still greater complexity, most of which are entirely unsuited to pen and paper.

The development of cryptography

Cryptography

Cryptography is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of third parties...

has been paralleled by the development of cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key...

— the "breaking" of codes and cipher

Cipher

In cryptography, a cipher is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption — a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is encipherment. In non-technical usage, a “cipher” is the same thing as a “code”; however, the concepts...

s. The discovery and application, early on, of frequency analysis

Frequency analysis

In cryptanalysis, frequency analysis is the study of the frequency of letters or groups of letters in a ciphertext. The method is used as an aid to breaking classical ciphers....

to the reading of encrypted communications has, on occasion, altered the course of history. Thus the Zimmermann Telegram

Zimmermann Telegram

The Zimmermann Telegram was a 1917 diplomatic proposal from the German Empire to Mexico to make war against the United States. The proposal was caught by the British before it could get to Mexico. The revelation angered the Americans and led in part to a U.S...

triggered the United States' entry into World War I; and Allied reading of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

's ciphers shortened World War II, in some evaluations by as much as two years.

Until the 1970s, secure cryptography was largely the preserve of governments. Two events have since brought it squarely into the public domain: the creation of a public encryption standard (DES

Data Encryption Standard

The Data Encryption Standard is a block cipher that uses shared secret encryption. It was selected by the National Bureau of Standards as an official Federal Information Processing Standard for the United States in 1976 and which has subsequently enjoyed widespread use internationally. It is...

), and the invention of public-key cryptography

Public-key cryptography

Public-key cryptography refers to a cryptographic system requiring two separate keys, one to lock or encrypt the plaintext, and one to unlock or decrypt the cyphertext. Neither key will do both functions. One of these keys is published or public and the other is kept private...

.

Classical cryptography

The earliest known use of cryptography is found in non-standard hieroglyphsEgyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs were a formal writing system used by the ancient Egyptians that combined logographic and alphabetic elements. Egyptians used cursive hieroglyphs for religious literature on papyrus and wood...

carved into monuments from the Old Kingdom of Egypt circa 1900 BC. These are not thought to be serious attempts at secret communications, however, but rather to have been attempts at mystery, intrigue, or even amusement for literate onlookers. These are examples of still other uses of cryptography, or of something that looks (impressively if misleadingly) like it. Some clay tablet

Clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age....

s from Mesopotamia somewhat later are clearly meant to protect information—one dated near 1500 BC was found to encrypt a craftsman's recipe for pottery glaze, presumably commercially valuable. Later still, Hebrew

Hebrew language

Hebrew is a Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Culturally, is it considered by Jews and other religious groups as the language of the Jewish people, though other Jewish languages had originated among diaspora Jews, and the Hebrew language is also used by non-Jewish groups, such...

scholars made use of simple monoalphabetic substitution ciphers (such as the Atbash cipher) beginning perhaps around 500 to 600 BC.

Scytale

In cryptography, a scytale is a tool used to perform a transposition cipher, consisting of a cylinder with a strip of parchment wound around it on which is written a message...

transposition cipher

Transposition cipher

In cryptography, a transposition cipher is a method of encryption by which the positions held by units of plaintext are shifted according to a regular system, so that the ciphertext constitutes a permutation of the plaintext. That is, the order of the units is changed...

claimed to have been used by the Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

n military). Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

tells us of secret messages physically concealed beneath wax on wooden tablets or as a tattoo on a slave's head concealed by regrown hair, though these are not properly examples of cryptography per se as the message, once known, is directly readable; this is known as steganography

Steganography

Steganography is the art and science of writing hidden messages in such a way that no one, apart from the sender and intended recipient, suspects the existence of the message, a form of security through obscurity...

. Another Greek method was developed by Polybius

Polybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

(now called the "Polybius Square"). The Romans

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

knew something of cryptography (e.g., the Caesar cipher

Caesar cipher

In cryptography, a Caesar cipher, also known as a Caesar's cipher, the shift cipher, Caesar's code or Caesar shift, is one of the simplest and most widely known encryption techniques. It is a type of substitution cipher in which each letter in the plaintext is replaced by a letter some fixed number...

and its variations).

Medieval cryptography

Qur'an

The Quran , also transliterated Qur'an, Koran, Alcoran, Qur’ān, Coran, Kuran, and al-Qur’ān, is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God . It is regarded widely as the finest piece of literature in the Arabic language...

which led to the invention of the frequency analysis technique for breaking monoalphabetic substitution cipher

Substitution cipher

In cryptography, a substitution cipher is a method of encryption by which units of plaintext are replaced with ciphertext according to a regular system; the "units" may be single letters , pairs of letters, triplets of letters, mixtures of the above, and so forth...

s, possibly by Al-Kindi

Al-Kindi

' , known as "the Philosopher of the Arabs", was a Muslim Arab philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician. Al-Kindi was the first of the Muslim peripatetic philosophers, and is unanimously hailed as the "father of Islamic or Arabic philosophy" for his synthesis, adaptation and promotion...

, an Arab mathematician, sometime around AD 800 (Ibrahim Al-Kadi −1992). It was the most fundamental cryptanalytic advance until WWII. Al-Kindi wrote a book on cryptography entitled Risalah fi Istikhraj al-Mu'amma (Manuscript for the Deciphering Cryptographic Messages), in which he described the first cryptanalysis techniques, including some for polyalphabetic cipher

Polyalphabetic cipher

A polyalphabetic cipher is any cipher based on substitution, using multiple substitution alphabets. The Vigenère cipher is probably the best-known example of a polyalphabetic cipher, though it is a simplified special case...

s, cipher classification, Arabic phonetics and syntax, and, most importantly, gave the first descriptions on frequency analysis. He also covered methods of encipherments, cryptanalysis of certain encipherments, and statistical analysis of letters and letter combinations in Arabic.

Ahmad al-Qalqashandi

Ahmad al-Qalqashandi

Shihab al-Din abu 'l-Abbas Ahmad ben Ali ben Ahmad Abd Allah al-Qalqashandi was a medieval Egyptian writer and mathematician born in a village in the Nile Delta. He is the author of Subh al-a 'sha, a fourteen volume encyclopedia in Arabic, which included a section on cryptology...

(1355–1418) wrote the Subh al-a 'sha, a 14-volume encyclopedia which included a section on cryptology. This information was attributed to Taj ad-Din Ali ibn ad-Duraihim ben Muhammad ath-Tha 'alibi al-Mausili who lived from 1312 to 1361, but whose writings on cryptography have been lost. The list of ciphers in this work included both substitution

Substitution cipher

In cryptography, a substitution cipher is a method of encryption by which units of plaintext are replaced with ciphertext according to a regular system; the "units" may be single letters , pairs of letters, triplets of letters, mixtures of the above, and so forth...

and transposition

Transposition cipher

In cryptography, a transposition cipher is a method of encryption by which the positions held by units of plaintext are shifted according to a regular system, so that the ciphertext constitutes a permutation of the plaintext. That is, the order of the units is changed...

, and for the first time, a cipher with multiple substitutions for each plaintext

Plaintext

In cryptography, plaintext is information a sender wishes to transmit to a receiver. Cleartext is often used as a synonym. Before the computer era, plaintext most commonly meant message text in the language of the communicating parties....

letter. Also traced to Ibn al-Duraihim is an exposition on and worked example of cryptanalysis, including the use of tables of letter frequencies

Letter frequencies

The frequency of letters in text has often been studied for use in cryptography, and frequency analysis in particular. No exact letter frequency distribution underlies a given language, since all writers write slightly differently. Linotype machines sorted the letters' frequencies as etaoin shrdlu...

and sets of letters which can not occur together in one word.

Essentially all ciphers remained vulnerable to the cryptanalytic technique of frequency analysis until the development of the polyalphabetic cipher, and many remained so thereafter. The polyalphabetic cipher was most clearly explained by Leon Battista Alberti around the year 1467, for which he was called the "father of Western cryptology". Johannes Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius , born Johann Heidenberg, was a German abbot, lexicographer, historian, cryptographer, polymath and occultist who had an influence on later occultism. The name by which he is more commonly known is derived from his native town of Trittenheim on the Mosel in Germany.-Life:He...

, in his work Poligraphia, invented the tabula recta

Tabula recta

In cryptography, the tabula recta is a square table of alphabets, each row of which is made by shifting the previous one to the left...

, a critical component of the Vigenère cipher. The French cryptographer Blaise de Vigenere

Blaise de Vigenère

Blaise de Vigenère was a French diplomat and cryptographer. The Vigenère cipher is so named due to the cipher being incorrectly attributed to him in the 19th century....

devised a practical poly alphabetic system which bears his name, the Vigenère cipher

Vigenère cipher

The Vigenère cipher is a method of encrypting alphabetic text by using a series of different Caesar ciphers based on the letters of a keyword. It is a simple form of polyalphabetic substitution....

.

In Europe, cryptography became (secretly) more important as a consequence of political competition and religious revolution. For instance, in Europe during and after the Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

, citizens of the various Italian states—the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

and the Roman Catholic Church included—were responsible for rapid proliferation of cryptographic techniques, few of which reflect understanding (or even knowledge) of Alberti's polyalphabetic advance. 'Advanced ciphers', even after Alberti, weren't as advanced as their inventors / developers / users claimed (and probably even themselves believed). They were regularly broken. This over-optimism may be inherent in cryptography for it was then, and remains today, fundamentally difficult to accurately know how vulnerable your system actually is. In the absence of knowledge, guesses and hopes, as may be expected, are common.

Cryptography, cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key...

, and secret agent/courier betrayal featured in the Babington plot

Babington Plot

The Babington Plot was a Catholic plot in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, a Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic, on the English throne. It led to the execution of Mary. The long-term goal was an invasion by the Spanish forces of King Philip II and the Catholic league in...

during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

which led to the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. An encrypted message from the time of the Man in the Iron Mask

Man in the Iron Mask

The Man in the Iron Mask is a name given to a prisoner arrested as Eustache Dauger in 1669 or 1670, and held in a number of jails, including the Bastille and the Fortress of Pignerol . He was held in the custody of the same jailer, Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, for a period of 34 years...

(decrypted just prior to 1900 by Étienne Bazeries

Étienne Bazeries

Étienne Bazeries was a French military cryptanalyst active between 1890 and the First World War. He is best known for developing the "Bazeries Cylinder", an improved version of Thomas Jefferson's cipher cylinder. It was later refined into the US Army M-94 cipher device. Historian David Kahn...

) has shed some, regrettably non-definitive, light on the identity of that real, if legendary and unfortunate, prisoner.

Outside of Europe, after the end of the Muslim Golden Age at the hand of the Mongols, cryptography remained comparatively undeveloped. Cryptography in Japan seems not to have been used until about 1510, and advanced techniques were not known until after the opening of the country to the West beginning in the 1860s. During the 1920s, it was Polish naval officers who assisted the Japanese military with code and cipher development.

Cryptography from 1800 to World War II

Although cryptography has a long and complex history, it wasn't until the 19th century that it developed anything more than ad hoc approaches to either encryption or cryptanalysisCryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key...

(the science of finding weaknesses in crypto systems). Examples of the latter include Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage, FRS was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who originated the concept of a programmable computer...

's Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

era work on mathematical cryptanalysis of polyalphabetic cipher

Polyalphabetic cipher

A polyalphabetic cipher is any cipher based on substitution, using multiple substitution alphabets. The Vigenère cipher is probably the best-known example of a polyalphabetic cipher, though it is a simplified special case...

s, redeveloped and published somewhat later by the Prussian Friedrich Kasiski

Friedrich Kasiski

Major Friedrich Wilhelm Kasiski was a Prussian infantry officer, cryptographer and archeologist. Kasiski was born in Schlochau, West Prussia .-Military service:...

. Understanding of cryptography at this time typically consisted of hard-won rules of thumb; see, for example, Auguste Kerckhoffs

Auguste Kerckhoffs

Auguste Kerckhoffs was a Dutch linguist and cryptographer who was professor of languages at the École des Hautes Études Commerciales in Paris in the late 19th century....

' cryptographic writings in the latter 19th century. Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective...

used systematic methods to solve ciphers in the 1840s. In particular he placed a notice of his abilities in the Philadelphia paper Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger, inviting submissions of ciphers, of which he proceeded to solve almost all. His success created a public stir for some months. He later wrote an essay on methods of cryptography which proved useful as an introduction for novice British cryptanalysts attempting to break German codes and ciphers during World War I, and a famous story, The Gold-Bug

The Gold-Bug

"The Gold-Bug" is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe. Set on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, the plot follows William Legrand, who was recently bitten by a gold-colored bug. His servant Jupiter fears him to be going insane and goes to Legrand's friend, an unnamed narrator who agrees to visit his...

, in which cryptanalysis was a prominent element.

Cryptography, and its misuse, were involved in the plotting which led to the execution of Mata Hari

Mata Hari

Mata Hari was the stage name of Margaretha Geertruida "M'greet" Zelle , a Dutch exotic dancer, courtesan, and accused spy who was executed by firing squad in France under charges of espionage for Germany during World War I.-Early life:Margaretha Geertruida Zelle was born in Leeuwarden, Friesland,...

and in the conniving which led to the travesty of Dreyfus' conviction

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

and imprisonment, both in the early 20th century. Fortunately, cryptographers were also involved in exposing the machinations which had led to Dreyfus' problems; Mata Hari, in contrast, was shot.

In World War I the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

's Room 40

Room 40

In the history of Cryptanalysis, Room 40 was the section in the Admiralty most identified with the British cryptoanalysis effort during the First World War.Room 40 was formed in October 1914, shortly after the start of the war...

broke German naval codes and played an important role in several naval engagements during the war, notably in detecting major German sorties into the North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

that led to the battles of Dogger Bank

Battle of Dogger Bank (1915)

The Battle of Dogger Bank was a naval battle fought near the Dogger Bank in the North Sea on 24 January 1915, during the First World War, between squadrons of the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet....

and Jutland

Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland was a naval battle between the British Royal Navy's Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet during the First World War. The battle was fought on 31 May and 1 June 1916 in the North Sea near Jutland, Denmark. It was the largest naval battle and the only...

as the British fleet was sent out to intercept them. However its most important contribution was probably in decrypting

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key...

the Zimmermann Telegram

Zimmermann Telegram

The Zimmermann Telegram was a 1917 diplomatic proposal from the German Empire to Mexico to make war against the United States. The proposal was caught by the British before it could get to Mexico. The revelation angered the Americans and led in part to a U.S...

, a cable from the German Foreign Office sent via Washington to its ambassador

Ambassador

An ambassador is the highest ranking diplomat who represents a nation and is usually accredited to a foreign sovereign or government, or to an international organization....

Heinrich von Eckardt

Heinrich von Eckardt

Heinrich von Eckardt was the ambassador for the German Empire in Mexico, assuming office around 1915 and spending most of his time as ambassador during World War I...

in Mexico which played a major part in bringing the United States into the war.

In 1917, Gilbert Vernam

Gilbert Vernam

Gilbert Sandford Vernam was an AT&T Bell Labs engineer who, in 1917, invented the stream cipher and later co-invented the one-time pad cipher. Vernam proposed a teleprinter cipher in which a previously-prepared key, kept on paper tape, is combined character by character with the plaintext message...

proposed a teleprinter cipher in which a previously-prepared key, kept on paper tape, is combined character by character with the plaintext message to produce the cyphertext. This led to the development of electromechanical devices as cipher machines, and to the only unbreakable cypher, the one time pad.

Mathematical methods proliferated in the period prior to World War II (notably in William F. Friedman

William F. Friedman

William Frederick Friedman was a US Army cryptographer who ran the research division of the Army's Signals Intelligence Service in the 1930s, and parts of its follow-on services into the 1950s...

's application of statistical techniques to cryptanalysis and cipher development and in Marian Rejewski

Marian Rejewski

Marian Adam Rejewski was a Polish mathematician and cryptologist who in 1932 solved the plugboard-equipped Enigma machine, the main cipher device used by Germany...

's initial break into the German Army's version of the Enigma system) in 1932.

World War II cryptography

Cipher

In cryptography, a cipher is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption — a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is encipherment. In non-technical usage, a “cipher” is the same thing as a “code”; however, the concepts...

were in wide use, although—where such machines were impractical—manual systems continued in use. Great advances were made in both cipher design and cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key...

, all in secrecy. Information about this period has begun to be declassified as the official British 50-year secrecy period has come to an end, as US archives have slowly opened, and as assorted memoirs and articles have appeared.

The Germans made heavy use, in several variants, of an electromechanical rotor machine

Rotor machine

In cryptography, a rotor machine is an electro-mechanical device used for encrypting and decrypting secret messages. Rotor machines were the cryptographic state-of-the-art for a prominent period of history; they were in widespread use in the 1920s–1970s...

known as Enigma

Enigma machine

An Enigma machine is any of a family of related electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines used for the encryption and decryption of secret messages. Enigma was invented by German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I...

. Mathematician Marian Rejewski

Marian Rejewski

Marian Adam Rejewski was a Polish mathematician and cryptologist who in 1932 solved the plugboard-equipped Enigma machine, the main cipher device used by Germany...

, at Poland's Cipher Bureau

Biuro Szyfrów

The Biuro Szyfrów was the interwar Polish General Staff's agency charged with both cryptography and cryptology ....

, in December 1932 deduced the detailed structure of the German Army Enigma, using mathematics and limited documentation supplied by Captain Gustave Bertrand

Gustave Bertrand

Gustave Bertrand was a French military intelligence officer who made a vital contribution to the decryption, by Poland's Cipher Bureau, of German Enigma ciphers, beginning in December 1932...

of French military intelligence

Military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that exploits a number of information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to commanders in support of their decisions....

. This was the greatest breakthrough in cryptanalysis in a thousand years and more, according to historian David Kahn. Rejewski and his mathematical Cipher Bureau colleagues, Jerzy Różycki

Jerzy Rózycki

Jerzy Witold Różycki was a Polish mathematician and cryptologist who worked at breaking German Enigma-machine ciphers.-Life:Różycki was born in what is now Ukraine, the fourth and youngest child of Zygmunt Różycki, a pharmacist and graduate of Saint Petersburg University, and Wanda, née Benita. ...

and Henryk Zygalski

Henryk Zygalski

Henryk Zygalski was a Polish mathematician and cryptologist who worked at breaking German Enigma ciphers before and during World War II.-Life:...

, continued reading Enigma and keeping pace with the evolution of the German Army machine's components and encipherment procedures. As the Poles' resources became strained by the changes being introduced by the Germans, and as war loomed, the Cipher Bureau

Biuro Szyfrów

The Biuro Szyfrów was the interwar Polish General Staff's agency charged with both cryptography and cryptology ....

, on the Polish General Staff

General Staff

A military staff, often referred to as General Staff, Army Staff, Navy Staff or Air Staff within the individual services, is a group of officers and enlisted personnel that provides a bi-directional flow of information between a commanding officer and subordinate military units...

's instructions, on 25 July 1939, at Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, initiated French and British intelligence representatives into the secrets of Enigma decryption.

Soon after World War II broke out on 1 September 1939, key Cipher Bureau

Biuro Szyfrów

The Biuro Szyfrów was the interwar Polish General Staff's agency charged with both cryptography and cryptology ....

personnel were evacuated southeastward; on 17 September, as the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

attacked Poland, they crossed into Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

. From there they reached Paris, France; at PC Bruno

PC Bruno

PC Bruno was a Polish-French intelligence station that operated outside Paris during World War II, from October 1939 until June 9, 1940. It decrypted German ciphers, most notably messages enciphered on the Enigma machine.-History:...

, near Paris, they continued breaking Enigma, collaborating with British cryptologists at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an estate located in the town of Bletchley, in Buckinghamshire, England, which currently houses the National Museum of Computing...

as the British got up to speed on breaking Enigma. In due course, the British cryptographers - whose ranks included many chess masters and mathematics dons such as Gordon Welchman

Gordon Welchman

Gordon Welchman was a British-American mathematician, university professor, World War II codebreaker at Bletchley Park, and author.-Education and early career:...

, Max Newman

Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander "Max" Newman, FRS was a British mathematician and codebreaker.-Pre–World War II:Max Newman was born Maxwell Neumann in Chelsea, London, England, on 7 February 1897...

, and Alan Turing

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS , was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which played a...

(the conceptual founder of modern computing

Computer

A computer is a programmable machine designed to sequentially and automatically carry out a sequence of arithmetic or logical operations. The particular sequence of operations can be changed readily, allowing the computer to solve more than one kind of problem...

) - substantially advanced the scale and technology of Enigma

Enigma machine

An Enigma machine is any of a family of related electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines used for the encryption and decryption of secret messages. Enigma was invented by German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I...

decryption.

At the end of the War, on 19 April 1945, Britain's top military officers were told that they could never reveal that the German Enigma cipher had been broken because it would give the defeated enemy the chance to say they "were not well and fairly beaten".

US Navy cryptographers (with cooperation from British and Dutch cryptographers after 1940) broke into several Japanese Navy

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1869 until 1947, when it was dissolved following Japan's constitutional renunciation of the use of force as a means of settling international disputes...

crypto systems. The break into one of them, JN-25

JN-25

The vulnerability of Japanese naval codes and ciphers was crucial to the conduct of World War II, and had an important influence on foreign relations between Japan and the west in the years leading up to the war as well...

, famously led to the US victory in the Battle of Midway

Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway is widely regarded as the most important naval battle of the Pacific Campaign of World War II. Between 4 and 7 June 1942, approximately one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea and six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy decisively defeated...

; and to the publication of that fact in the Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune

The Chicago Tribune is a major daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, and the flagship publication of the Tribune Company. Formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" , it remains the most read daily newspaper of the Chicago metropolitan area and the Great Lakes region and is...

shortly after the battle, though the Japanese seem not to have noticed for they kept using the JN-25 system. A US Army group, the SIS

Signals Intelligence Service

The Signals Intelligence Service was the United States Army codebreaking division, headquartered at Arlington Hall. It was a part of the Signal Corps so secret that outside the office of the Chief Signal officer, it did not officially exist. William Friedman began the division with three "junior...

, managed to break the highest security Japanese diplomatic cipher system (an electromechanical 'stepping switch' machine called Purple by the Americans) even before WWII began. The Americans referred to the intelligence resulting from cryptanalysis, perhaps especially that from the Purple machine, as 'Magic'. The British eventually settled on 'Ultra' for intelligence resulting from cryptanalysis, particularly that from message traffic protected by the various Enigmas. An earlier British term for Ultra had been 'Boniface' in an attempt to suggest, if betrayed, that it might have an individual agent as a source.

The German military also deployed several mechanical attempts at a one-time pad

One-time pad

In cryptography, the one-time pad is a type of encryption, which has been proven to be impossible to crack if used correctly. Each bit or character from the plaintext is encrypted by a modular addition with a bit or character from a secret random key of the same length as the plaintext, resulting...

. Bletchley Park called them the Fish cipher

Fish (cryptography)

Fish was the Allied codename for any of several German teleprinter stream ciphers used during World War II. Enciphered teleprinter traffic was used between German High Command and Army Group commanders in the field, so its intelligence value was of the highest strategic value to the Allies...

s, and Max Newman

Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander "Max" Newman, FRS was a British mathematician and codebreaker.-Pre–World War II:Max Newman was born Maxwell Neumann in Chelsea, London, England, on 7 February 1897...

and colleagues designed and deployed the Heath Robinson

Heath Robinson (codebreaking machine)

Heath Robinson was a machine used by British codebreakers at Bletchley Park during World War II to solve messages in the German teleprinter cipher used by the Lorenz SZ40/42 cipher machine; the cipher and machine were called "Tunny" by the codebreakers, who named different German teleprinter...

, and then the world's first programmable digital electronic computer, the Colossus

Colossus computer

Not to be confused with the fictional computer of the same name in the movie Colossus: The Forbin Project.Colossus was the world's first electronic, digital, programmable computer. Colossus and its successors were used by British codebreakers to help read encrypted German messages during World War II...

, to help with their cryptanalysis. The German Foreign Office began to use the one-time pad

One-time pad

In cryptography, the one-time pad is a type of encryption, which has been proven to be impossible to crack if used correctly. Each bit or character from the plaintext is encrypted by a modular addition with a bit or character from a secret random key of the same length as the plaintext, resulting...

in 1919; some of this traffic was read in WWII partly as the result of recovery of some key material in South America that was discarded without sufficient care by a German courier.

The Japanese Foreign Office used a locally developed electrical stepping switch based system (called Purple by the US), and also had used several similar machines for attaches in some Japanese embassies. One of these was called the 'M-machine' by the US, another was referred to as 'Red'. All were broken, to one degree or another, by the Allies.

Allies

In everyday English usage, allies are people, groups, or nations that have joined together in an association for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out between them...

cipher machines used in WWII included the British TypeX

Typex

In the history of cryptography, Typex machines were British cipher machines used from 1937. It was an adaptation of the commercial German Enigma with a number of enhancements that greatly increased its security....

and the American SIGABA

SIGABA

In the history of cryptography, the ECM Mark II was a cipher machine used by the United States for message encryption from World War II until the 1950s...

; both were electromechanical rotor designs similar in spirit to the Enigma, albeit with major improvements. Neither is known to have been broken by anyone during the War. The Poles used the Lacida

Lacida

The Lacida was a Polish rotor cipher machine. It was designed and produced before World War II by Poland's Cipher Bureau for prospective wartime use by Polish military higher commands.-History:...

machine, but its security was found to be less than intended (by Polish Army cryptographers in the UK), and its use was discontinued. US troops in the field used the M-209

M-209

In cryptography, the M-209, designated CSP-1500 by the Navy is a portable, mechanical cipher machine used by the US military primarily in World War II, though it remained in active use through the Korean War...

and the still less secure M-94

M-94

The M-94 was a piece of cryptographic equipment used by the United States army, consisting of several lettered discs arranged as a cylinder. The idea for the device was conceived by Colonel Parker Hitt and then developed by Major Joseph Mauborgne in 1917...

family machines. British SOE

Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive was a World War II organisation of the United Kingdom. It was officially formed by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton on 22 July 1940, to conduct guerrilla warfare against the Axis powers and to instruct and aid local...

agents initially used 'poem ciphers' (memorized poems were the encryption/decryption keys), but later in the War, they began to switch

Leo Marks

Leopold Samuel Marks was an English cryptographer, screenwriter and playwright.-Early life:Born the son of an antiquarian bookseller in London, he was first introduced to cryptography when his father showed him a copy of Edgar Allan Poe's story, "The Gold-Bug"...

to one-time pad

One-time pad

In cryptography, the one-time pad is a type of encryption, which has been proven to be impossible to crack if used correctly. Each bit or character from the plaintext is encrypted by a modular addition with a bit or character from a secret random key of the same length as the plaintext, resulting...

s.

The VIC cipher

VIC cipher

The VIC cipher was a pencil and paper cipher used by the Soviet spy Reino Häyhänen, codenamed "VICTOR".It was arguably the most complex hand-operated cipher ever seen, when it was first discovered...

(used at least until 1957 in connection with Rudolf Abel's NY spy ring) was a very complex hand cipher, and is claimed to be the most complicated known to have been used by the Soviets, according to David Kahn in Kahn on Codes. For the decrypting of Soviet ciphers (particularly when one-time pads were reused), see Venona project

Venona project

The VENONA project was a long-running secret collaboration of the United States and United Kingdom intelligence agencies involving cryptanalysis of messages sent by intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union, the majority during World War II...

.

Modern cryptography

Both cryptography and cryptanalysis have become far more mathematical since World War II. Even so, it has taken the wide availability of computers, and the Internet as a communications medium, to bring effective cryptography into common use by anyone other than national governments or similarly large enterprises.Shannon

The era of modern cryptography really begins with Claude Shannon, arguably the father of mathematical cryptography, with the work he did during WWII on communications security. In 1949 he published Communication Theory of Secrecy SystemsCommunication Theory of Secrecy Systems

Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems is a paper published in 1949 by Claude Shannon discussing cryptography from the viewpoint of information theory. It is one of the foundational treatments of modern cryptography...

in the Bell System Technical Journal

Bell System Technical Journal

The Bell System Technical Journal was the in-house scientific journal of Bell Labs that was published from 1922 to 1983.- Notable papers :...

and a little later the book The Mathematical Theory of Communication (expanding on an earlier article "A Mathematical Theory of Communication

A Mathematical Theory of Communication

"A Mathematical Theory of Communication" is an influential 1948 article by mathematician Claude E. Shannon. As of November 2011, Google Scholar has listed more than 48,000 unique citations of the article and the later-published book version...

") with Warren Weaver

Warren Weaver

Warren Weaver was an American scientist, mathematician, and science administrator...

. Both included results from his WWII work. These, in addition to his other works on information and communication theory

Information theory

Information theory is a branch of applied mathematics and electrical engineering involving the quantification of information. Information theory was developed by Claude E. Shannon to find fundamental limits on signal processing operations such as compressing data and on reliably storing and...

, established a solid theoretical basis for cryptography and also for much of cryptanalysis. And with that, cryptography more or less disappeared into secret government communications organizations such as NSA, GCHQ, and their equivalents elsewhere. Very little work was again made public until the mid 1970s, when everything changed.

An encryption standard

The mid-1970s saw two major public (i.e., non-secret) advances. First was the publication of the draft Data Encryption StandardData Encryption Standard

The Data Encryption Standard is a block cipher that uses shared secret encryption. It was selected by the National Bureau of Standards as an official Federal Information Processing Standard for the United States in 1976 and which has subsequently enjoyed widespread use internationally. It is...

in the U.S. Federal Register on 17 March 1975. The proposed DES cipher was submitted by a research group at IBM, at the invitation of the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST), in an effort to develop secure electronic communication facilities for businesses such as banks and other large financial organizations. After 'advice' and modification by NSA, acting behind the scenes, it was adopted and published as a Federal Information Processing Standard

Federal Information Processing Standard

A Federal Information Processing Standard is a publicly announced standardization developed by the United States federal government for use in computer systems by all non-military government agencies and by government contractors, when properly invoked and tailored on a contract...

Publication in 1977 (currently at FIPS 46-3). DES was the first publicly accessible cipher to be 'blessed' by a national agency such as NSA. The release of its specification by NBS stimulated an explosion of public and academic interest in cryptography.

The aging DES was officially replaced by the Advanced Encryption Standard

Advanced Encryption Standard

Advanced Encryption Standard is a specification for the encryption of electronic data. It has been adopted by the U.S. government and is now used worldwide. It supersedes DES...

(AES) in 2001 when NIST announced FIPS 197. After an open competition, NIST selected Rijndael, submitted by two Belgian cryptographers, to be the AES. DES, and more secure variants of it (such as Triple DES

Triple DES

In cryptography, Triple DES is the common name for the Triple Data Encryption Algorithm block cipher, which applies the Data Encryption Standard cipher algorithm three times to each data block....

), are still used today, having been incorporated into many national and organizational standards. However, its 56-bit key-size has been shown to be insufficient to guard against brute force attack

Brute force attack

In cryptography, a brute-force attack, or exhaustive key search, is a strategy that can, in theory, be used against any encrypted data. Such an attack might be utilized when it is not possible to take advantage of other weaknesses in an encryption system that would make the task easier...

s (one such attack, undertaken by the cyber civil-rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation

Electronic Frontier Foundation

The Electronic Frontier Foundation is an international non-profit digital rights advocacy and legal organization based in the United States...

in 1997, succeeded in 56 hours.) As a result, use of straight DES encryption is now without doubt insecure for use in new cryptosystem designs, and messages protected by older cryptosystems using DES, and indeed all messages sent since 1976 using DES, are also at risk. Regardless of DES' inherent quality, the DES key size (56-bits) was thought to be too small by some even in 1976, perhaps most publicly by Whitfield Diffie

Whitfield Diffie

Bailey Whitfield 'Whit' Diffie is an American cryptographer and one of the pioneers of public-key cryptography.Diffie and Martin Hellman's paper New Directions in Cryptography was published in 1976...

. There was suspicion that government organizations even then had sufficient computing power to break DES messages; clearly others have achieved this capability.

Public key

The second development, in 1976, was perhaps even more important, for it fundamentally changed the way cryptosystems might work. This was the publication of the paper New Directions in Cryptography by Whitfield DiffieWhitfield Diffie

Bailey Whitfield 'Whit' Diffie is an American cryptographer and one of the pioneers of public-key cryptography.Diffie and Martin Hellman's paper New Directions in Cryptography was published in 1976...

and Martin Hellman

Martin Hellman

Martin Edward Hellman is an American cryptologist, and is best known for his invention of public key cryptography in cooperation with Whitfield Diffie and Ralph Merkle...

. It introduced a radically new method of distributing cryptographic keys, which went far toward solving one of the fundamental problems of cryptography, key distribution, and has become known as Diffie-Hellman key exchange

Diffie-Hellman key exchange

Diffie–Hellman key exchange Synonyms of Diffie–Hellman key exchange include:*Diffie–Hellman key agreement*Diffie–Hellman key establishment*Diffie–Hellman key negotiation...

. The article also stimulated the almost immediate public development of a new class of enciphering algorithms, the asymmetric key algorithms.

Prior to that time, all useful modern encryption algorithms had been symmetric key algorithms, in which the same cryptographic key is used with the underlying algorithm by both the sender and the recipient, who must both keep it secret. All of the electromechanical machines used in WWII were of this logical class, as were the Caesar

Caesar cipher

In cryptography, a Caesar cipher, also known as a Caesar's cipher, the shift cipher, Caesar's code or Caesar shift, is one of the simplest and most widely known encryption techniques. It is a type of substitution cipher in which each letter in the plaintext is replaced by a letter some fixed number...

and Atbash

Atbash

Atbash is a simple substitution cipher for the Hebrew alphabet. It consists in substituting aleph for tav , beth for shin , and so on, reversing the alphabet. In the Book of Jeremiah, Lev Kamai is Atbash for Kasdim , and Sheshakh is Atbash for Bavel...

ciphers and essentially all cipher systems throughout history. The 'key' for a code is, of course, the codebook, which must likewise be distributed and kept secret, and so shares most of the same problems in practice.

Of necessity, the key in every such system had to be exchanged between the communicating parties in some secure way prior to any use of the system (the term usually used is 'via a secure channel

Secure channel

In cryptography, a secure channel is a way of transferring data that is resistant to interception and tampering.A confidential channel is a way of transferring data that is resistant to interception, but not necessarily resistant to tampering....