History of medieval Tunisia

Encyclopedia

The medieval era opens with the commencement of a process that would return Ifriqiya

, i.e., Tunisia, and the entire Maghrib

to local Berber rule. The precipitating cause was the departure of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate to their newly conquered territories in Egypt. To govern Ifriqiya in their stead, the Fatimids left the Zirid

dynasty. Yet the Zirids would eventually break all ties to the Fatimids, even to the point of formally embracing Sunni

doctrines (rivals to the Shi'a).

At this period there arose in the Maghrib two strong local movements dedicated to Muslim purity and practice, one following the other. First, the Almoravids emerged in the far west, i.e., in al-Maghrib al-Aksa (Morocco); although establishing a large empire running from modern Spain to southern Mauretania, Almoravid rule did not reach to the east as far as Ifriqiya. Later another Berber religious leader Ibn Tumart

founded the Almohad

movement, which supplanted the Almoravids, and grew to unify under its rule all of the west of Islam, al-Andalus

as well as al-Maghrib. In Ifriqiya at the city of Tunis, the Hafsids became the eventual successor to Almohad rule. The Hafsids were a local Berber dynasty, whose own rule would continue for centuries with varying success, until the arrival of the Ottomans in the western Mediterranean.

enjoyed self-rule (1048-1574). The Fatimids were Shi'a, specifically of the more controversial Isma'ili branch. They originated in Islamic lands far to the east. Today, and for many centuries, the majority of Tunisians identify as Sunni (also from the east, but who oppose the Shi'a). Yet in Ifriqiyah at the time of the Fatimids, any rule from the east whether Sunni or Shi'a was generally not welcome. Hence the rise in medieval Tunisia (Ifriqiya) of regimes not beholden to the east (al-Mashriq), which marks a new and a popular era of Berber sovereignty.

Initially the local agents of the Fatimids managed to inspire the allegiance of Berber

Initially the local agents of the Fatimids managed to inspire the allegiance of Berber

elements around Ifriqiya by appealing to Berber distrust of the Islamic east, here in the form of Aghlabid rule. Thus the Fatimids were ultimately successful in acquiring local state power. Nonetheless, once installed in Ifriqiya, Fatimid rule greatly disrupted social harmony; they imposed high, unorthodox taxes, leading to a Kharijite revolt. Later, the Fatimids of Ifriqiya managed to accomplish their long-held, grand design for the conquest of Islamic Egypt; soon thereafter their leadership relocated to Cairo

. The Fatimids left the Berber Zirids as their local vassals to govern in the Maghrib. Originally only a client of the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Egypt, the Zirids eventually expelled the Shi'a Fatimids from Ifriqiya. In revenge, the Fatimids sent the disruptive Banu Hilal

against Ifriqiya, which led to a period of social chaos and economic decline.

The independent Zirid dynasty has been viewed historically as a Berber kingdom; the Zirids were essentially founded by a leader among the Sanhaja

Berbers. Concurrently, the Sunni Ummayyad Caliphate of Córdoba

were opposing and battling against the Shi'a Fatimids. Perhaps because Tunisians have long been Sunnis themselves, they may currently evidence faint pride in the Fatimid Caliphate's rôle in Islamic history. In addition to their above grievances against the Fatimids (per the Banu Hilal), during the Fatimid era the prestige of cultural leadership within al-Maghrib shifted decisively away from Ifriqiya

and instead came to be the prize of al-Andalus

.

During the interval of generally disagreeable Shi'a rule, the Berber people appear to have ideologically moved away from a popular antagonism against the Islamic east (al-Mashriq), and toward an acquiescence to its Sunni orthodoxy, though of course mediated by their own Maliki

school of law (viewed as one of the four orthodox madhhab

by the Sunni). Professor Abdallah Laroui remarks that while enjoying sovereignty the Berber Maghrib experimented with several doctrinal viewpoints during the 9th to the 13th centuries, including the Khariji, Zaydi, Shi'a, and Almohad

. Eventually they settled on an orthodoxy, on Maliki Sunni doctrines. This progression indicates a grand period of Berber self-definition.

Tunis under the Almohads would become the permanent capital of Ifriqiya. The social discord between Berber and Arab would move toward resolution. In fact it might be said that the history of the Ifriqiya prior to this period was prologue, which merely set the stage; henceforth, the memorable events acted on that stage would come to compose the History of Tunisia for its modern people. Prof. Perkins mentions the preceding history of rule from the east (al-Mashriq), and comments that following the Fatimids departure there arose in Tunisia an intent to establish a "Muslim state geared to the interests of its Berber majority." Thus commenced the medieval era of their sovereignty.

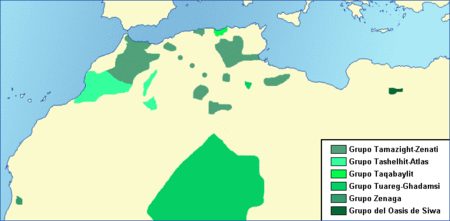

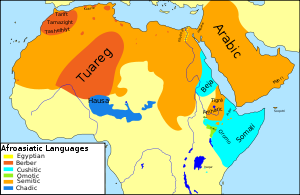

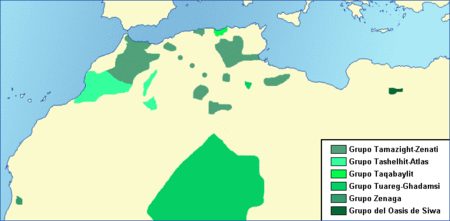

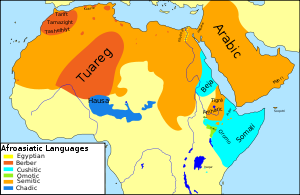

Twenty or so Berber languages

(also called Tamazight) are spoken in North Africa. Berber speakers were once predominate over all this large area, but as a result of Arabization

and later local migrations, today Berber languages are reduced to several large regions (in Morocco, Algeria, and the central Sahara) or remain as smaller language islands. Several linguists characterize the Berber spoken as one language with many dialect variations, spread out in discrete regions, without ongoing standardization. The Berber languages may be classified as follows (with some more widely known languages or language groups shown in italics). Ethnic historical correspondence is suggested by the designation |Tribe|.

Nota Bene: The classification and nomenclature of Berber languages lack complete consensus.

The Libyan

Berbers developed their own writing system, evidently derived from Phoenician, as early as the 4th century BC. It was a boustrophic script, i.e., written left to right then right to left on alternating lines, or up and down in columns. Most of these early inscriptions were funerary and short in length. Several longer texts exist, taken from Thugga, modern Dougga, Tunisia. Both are bilingual, being written in Punic with its letters and in Berber with its letters

. One throws some light on the governing institutions of the Berbers in the 2nd century BC. The other text begins: "This temple the citizens of Thugga built for King Masinissa

... ." Today the script descendent from the ancient Libyan remains in use; it is called Tifinagh

.

Berber, however, no longer is widely spoken in present day Tunisia; e.g., centuries ago many of its Zenata

Berber, however, no longer is widely spoken in present day Tunisia; e.g., centuries ago many of its Zenata

Berbers became Arabized. Today in Tunisia the small minority that speaks Berber may be heard on Jerba island, around the salt lakes

region, and near the desert

, as well as along the mountainous

border with Algeria (across this frontier to the west lies a large region where the Zenati

Berber languages and dialects predominate). In contrast, use of Berber is relatively common in Morocco, and also in Algeria, and in the remote central Sahara. Berber poetry endures, as well as a traditional Berber literature.

The grand tribal identities of Berber antiquity were said to be the Mauri

, the Numidians

, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauritania, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians were located between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both had large sedentary

populations. The Gaetulians were less settled, with large pastoral

elements, and lived in the near south on the margins of the Sahara. The medieval historian of the Maghrib, Ibn Khaldun

, is credited or blamed for theorizing a causative dynamic to the different tribal confederacies over time. Issues concerning tribal social-economies and their influence have generated a large literature, which critics say is overblown. Abdallah Laroui discounts the impact of tribes, declaring the subject a form of obfuscation which cloaks suspect colonial ideologies. While Berber tribal society has made an impact on culture and government, their continuance was chiefly due to strong foreign interference which usurped the primary domain of the government institutions, and derailed their natural political development. Rather than there being a predisposition for tribal structures, the Berber's survival strategy in the face of foreign occupation was to figuratively retreat into their own way of life through their enduring tribal networks. On the other hand, as it is accepted and understood, tribal societies in the Middle East have continued over millennia and from time to time flourish.

Berber tribal identities survived undiminished during the long period of dominance by the city-state of Carthage. Under centuries of Roman rule also tribal ways were maintained. The sustaining social customs would include: communal self-defense and group liability, marriage alliances, collective religious practices, reciprocal gift-giving, family working relationships and wealth. Abdallah Laroui summarizes the abiding results under foreign rule (here, by Carthage and by Rome) as: Social (assimilated, nonassimilated

, free); Geographical (city, country, desert); Economic (commerce, agriculture, nomadism); and, Linguistic (e.g., Latin

, Punico-Berber, Berber).

During the initial centuries of the Islamic era, it was said that the Berbers tribes were divided into two blocs, the Butr (Zanata and allies) and the Baranis (Sanhaja, Masmuda, and others). The etymology

is unclear, perhaps deriving from tribal customs for clothing ("abtar" and "burnous"), or perhaps words coined to distinguish the nomad (Butr) from the farmer (Baranis). The Arabs drew most of their early recruits from the Butr. Later, legends arose which spoke of an obscure, ancient invasion of North Africa by the Himyarite Arabs of Yemen

, from which a prehistoric ancestry was evidently fabricated: Berber descent from two brothers, Burnus and Abtar, who were sons of Barr, the grandson of Canaan

(Canaan being the grandson of Noah

through his son Ham

). Both Ibn Khaldun

(1332–1406) and Ibn Hazm

(994-1064) as well as Berber genealogists

held that the Himyarite Arab ancestry was totally unacceptable. This legendary ancestry, however, played a rôle in the long Arabization

process that continued for centuries among the Berber peoples.

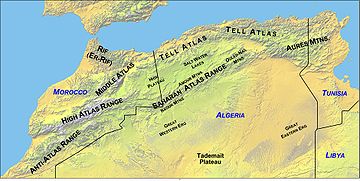

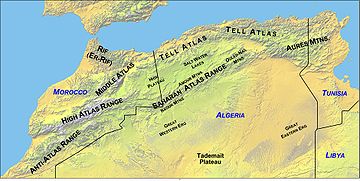

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the Sanhaja

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the Sanhaja

, and the Masmuda

. These tribal divisions are mentioned by Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406). The Zanata early on allied more closely with the Arabs and consequently became more Arabized, although Znatiya Berber is still spoken in small islands across Algeria and in northern Morocco (the Rif

and north Middle Atlas

). The Sanhaja are also widely dispersed throughout the Maghrib, among which are: the sedentary Kabyle

on the coast west of modern Algiers

, the nomadic Zanaga

of southern Morocco (the south Anti-Atlas

) and the western Sahara to Senegal

, and the Tuareg (al-Tawarik), the well-known camel breeding nomads of the central Sahara

. The descendants of the Masmuda are sedentary

Berbers of Morocco, in the High Atlas

, and from Rabat

inland to Azru and Khanifra, the most populous of the modern Berber regions.

Medieval events in Ifriqiya

and al-Maghrib

often have tribal assoiciations. Linked to the Kabyle Sanhaja were the Kutama

tribes, whose support worked to establish the Fatimid Caliphate

(909-1171, only until 1049 in Ifriqiya); their vassals and later successors in Ifriqiya the Zirids (973-1160) were also Sanhaja. The Almoravids

(1056–1147) first began far south of Morocco, among the Lamtuna

Sanhaja. From the Masmuda came Ibn Tumart

and the Almohad movement (1130–1269), later supported by the Sanhaja. Accordingly, it was from among the Masmuda that the Hafsid dynasty

(1227-1574) of Tunis

originated.

The Zirid

The Zirid

dynasty (972-1148) began their rule as agents of the Shi'a Fatimids (909-1171), who had conquered Egypt in 969. After removing their capital to Cairo

from Mahdiya in Ifriqiya, the Fatimids also withdrew from direct governance of al-Maghrib, which they delegated to a local vassal. Their Maghriban power, however, was not transferred to a loyal Kotama

Berber, which tribe had provided crucial support to the Fatimids during their rise. Instead authority was given to a chief from among the Sanhaja

Berber confederacy of the central Magrib, Buluggin ibn Ziri

(d.984). His father Ziri had been a loyal follower and soldier of the Fatimids.

For a time the region enjoyed great prosperity and the early Zirid court famously enjoyed luxury and the arts. Yet political affairs were turbulent. Bologguin's war against the Zenata

Berbers to the west was fruitless. His son al-Mansur (r. 984-996) challenged rule by the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Cairo, but without his intended effect; instead, the Kotama Berbers were inspired by the Fatimids to rebell; al-Manur did manage to subdue the Kotama. The Fatimids continued to demand tribute payments from the Zirids. After Buluggin's death, the Fatamid vassalage had eventually been split among two dynasties: for Ifriqiya the Zirid

(972-1148); and for western lands [in present day Algeria] the Hammadid

(1015–1152), named for Hammad, another descendant of Buluggin. The security of civic life declined, due largely to intermittent political quarrels between the Zirids and the Hammadids, including a civil war ending in 1016. Also armed attacks came from the Sunni Umayyads of al-Andalus

and from the other Berbers, e.g., the Zanatas of Morocco.

Even though in this period the Maghrib often fell into conflict, becoming submerged in political confusion, the Fatimid province of Ifriqiya at first managed to continue in relative prosperity under the Zirid Berbers. Agriculture thrived (grains and olives), as did the artisans of the city (weavers, metalworkers, potters), and the Saharan trade, too. The holy city of Kairouan

served also as the chief political and cultural center of the Zirid state. Soon however the Saharan trade

began to decline, caused by changing demand, and by the encroachments of rival traders: from Fatimid Egypt to the east, and from the rising power of the al-Murabit Berber movement in Morocco to the west. This decline in the Saharan trade caused a rapid deterioration in the commercial well being of Kairouan. To compensate, the Zirids encouraged the sea trade of their coastal cities, which did begin to quicken; however, they faced rigorous competition from Mediterranean

traders of the rising city-states of Genoa

and Pisa

.

. Consequently, many shia were killed during disturbances throughout Ifriqiya. The Zirid state seized Fatimid wealth and coinage. Sunni Maliki jurists were reestablished as the prevailing school of law.

In retaliation, the Fatimid political leaders sent against the Zirids an invasion of nomad

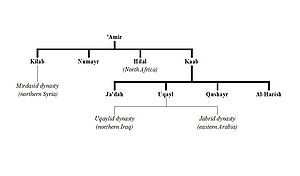

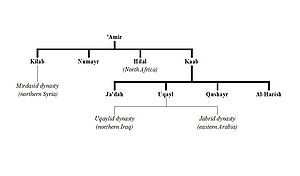

ic Arabians, the Banu Hilal, who had already migrated into upper Egypt. These warrior bedouins were induced by the Fatimids to continue westward into Ifriqiya. Ominously, westward toward Zirid Ifriqiya came the entire Banu Hilal, along with them the Banu Sulaym, both Arab tribes quitting upper Egypt where they had been pasturing their animals.

The arriving Bedouin

The arriving Bedouin

s of the Banu Hilal

defeated in battle the Zirid and Hammadid Berber armies in 1057, and sack the Zirid capital Kairouan. It has since been said that much of the Maghrib's misfortunes to follow can be traced to the chaos and regression occasioned by their arrival, although historical opinion is not unanimous. In Arab lore the Banu Hilal's leader Abu Zayd al-Hilali

is a hero; he enjoys a victory parade in Tunis where he is made lord of al-Andalus, according to the folk epic Taghribat Bani Hilal

. The Banu Hilal came from the tribal confederacy Banu 'Amir, located mostly in southwest Arabia.

In Tunisia as the Banu Halali tribes took control of the plains, the local sedentary populace were forced to take refuge in the mountains. The prosperous agriculture of central and northern Ifriqiya gave way to pastoralism

; consequently the economic well-being went into steep decline.

Even after the fall of the Zirids, the Banu Hilal were a source of disorder, as in the 1184 insurrection of the Banu Ghaniya

. These rough Arab newcomers, however, did constitute a second large wave of Arab immigration into Ifriqiya, and thus accelerated the process of Arabization

. Use of the Berber languages

decreased in rural areas as a result of the Bedouin ascendancy. Substantially weakened, Sanhaja

Zirid rule lingered, with civil society disrupted, and the regional economy now in chaos.

Indeed the norman king Roger II of Sicily

was able to create a coastal dominion of the area between Bona

and Tripoli that lasted from 1135 to 1160 and was supported mainly by the last local christian communities.

These communities, remnants of the north African original population during the Roman empire

, still spoke the African Romance

in a few places like Gabes

and Gafsa

: the most important testimony of the existence of the African Romance comes from the 12th century Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi

, who wrote that the people of Gafsa (in central-south Tunisia) used a language that he called al-latini al-afriqi ("the Latin of Africa").

.png) In the medieval Maghrib, among the Berber tribes, two strong religious movements arose one after the other: the Almoravids

In the medieval Maghrib, among the Berber tribes, two strong religious movements arose one after the other: the Almoravids

(1056–1147), and the Almohads (1130–1269). Professor Jamil Abun-Nasr compares these movements with the 8th-and-9th-century Kharijites

in the Magrib including Ifriqiya: each a militant Berber movement of strong Muslim faith, each rebellious against a status quo of lax orthodoxy, each seeking to found a state in which "leading the Muslim good life was the professed aim of politics". These medieval Berber movements, the Almoravids and the Almohads, have been compared to the more recent Wahhabis, strict fundamentalists of Saudi Arabia

.

The Almoravids [Arabic al-Murabitum, from Ribat, e.g., "defenders"] began as an Islamic movement of the Sanhaja

Berbers, arising in the remote deserts of the southwest Maghrib

. After a century, this movement had run its course, losing its cohesion and strength, thereafter becoming decadent. From their capital Marrakech

the Almoravids had once governed a large empire stretching from Mauritania

(south of Morocco) to al-Andalus

(southern Spain), yet Almoravid rule had never reached east far enough to include Ifriqiya.

The rival Almohads were also a Berber Islamic movement, whose founder was from the Masmuda

tribe. They defeated and supplanted the Amoravids and themselves established a large empire, which embraced the region of Ifriqiya

, formerly ruled by the Zirids.

movement [Arabic al-Muwahhidun, "the Unitarians"] ruled variously in the Maghrib starting about 1130 until 1248 (locally in Morocco until 1275). This movement had been founded by Ibn Tumart

(1077–1130), a Masmuda

Berber from the Atlas mountains

of Morocco, who became the mahdi

. After a pilgrimage to Mecca followed by study, he had returned to the Maghrib about 1218 inspired by the teachings of al-Ash'ari and al-Ghazali

. A charismatic leader, he preached an interior awareness of the Unity of God. A puritan and a hard-edged reformer, he gathered a strict following among the Berbers in the Atlas, founded a radical community, and eventually began an armed challenge to the current rulers, the Almoravids

(1056–1147).

.png) Ibn Tumart

Ibn Tumart

the Almohad founder left writings in which his theological ideas mix with the political. Therein he claimed that the leader, the mahdi, is infallible. Ibn Tumart created a hierarchy from among his followers which persisted long after the Almohad era (i.e., in Tunisia under the Hafsids), based not only on a specie of ethnic loyalty, such as the "Council of Fifty" [ahl al-Khamsin], and the assembly of "Seventy" [ahl al-Saqa], but more significantly based on a formal structure for an inner circle of governance that would transcend tribal loyalties, namely, (a) his ahl al-dar or "people of the house", a sort of privy council, (b) his ahl al-'Ashra or the "Ten", originally composed of his first ten forminable followers, and (c) a variety of offices. Ibn Tumart trained his own talaba or ideologists, as well as his huffaz, who function was both religious and military. There is lack of certainty about some details, but general agreement that Ibn Tumart sought to reduce the "influence of the traditional tribal framework." Later historical developments "were greatly facilitated by his original reorganization because it made possible collaboration among tribes" not likely to otherwise coalesce. These organizing and group solidarity preparations made by Ibn Tumart were "most methodical and efficient" and a "conscious replica" of the Medina period of the prophet Muhammad.

The mahdi Ibn Tumart also had championed the idea of strict Islamic law and morals displacing unorthodox aspects of Berber custom. At his early base at Tinmal, Ibn Tumart functioned as "the custodian of the faith, the arbiter of moral questions, and the chief judge." Yet evidently because of the narrow legalism then common among Maliki

jurists and because of their influence in the rival Almoravid regime, Ibn Tumart did not favor the Maliki school of law; nor did he favor any of the four recognized madhhab

s.

Following the Mahdi Ibn Tumart's death, Abd al-Mu'min

Following the Mahdi Ibn Tumart's death, Abd al-Mu'min

al-Kumi (c.1090-1163) circa 1130 became the Almohad caliph--the first non-Arab to take such title. Abd al-Mu'min had been one of the original "Ten" followers of Ibn Tumart. He immediately launched attacks on the ruling Almoravid and had wrestled Morocco away from them by 1147, suppressing subsequent revolts there. Then he crossed the straits, occupying al-Andalus

(in southern Spain); yet Almohad rule there was uneven and divisive. Abd al-Mu'min spend many years "organizing his state internally with a view to establishing the government of the Almohad state in his family." "Abd al-Mu'min tried to create a unified Muslim community in the Maghrib on the basis of Ibn Tumart's teachings."

Meanwhile the anarchy in Zirid Ifriqiya (Tunisia) made it a target for the Norman kingdom in Sicily

, who between 1134 and 1148 had taken control of Mahdia

, Gabès

, Sfax

, and the island of Jerba, all of which served as centers for commerce and trade. The only strong Muslim power then in the Maghreb

was that of the newly emerging Almohads, led by their caliph a Berber Abd al-Mu'min

. He responded with several military campaigns into the eastern Maghrib which absorbed the Hammaid and Zirid states, and removed the Christians. Thus in 1152 he first attacked and occupied Bougie

(in eastern Algeria), ruled by the Sanhaja Hammadid

s. His armies next entered Zirid

Ifriqiya, a disorganized territory, taking Tunis. His armies also besieged Mahdia, held by Normans of Sicily

, compelling these Christians to negotiate their withdrawal in 1160. Yet Christian merchants, e.g., from Genoa

and Pisa

, had already arrived to stay in Ifriqiya, so that such a foreign merchant presence (Italian and Aragonese

) continued.

With the capture of Tunis, Mahdia, and later Tripoli, the Almohad state reached from Morocco to Libya. "This was the first time that the Maghrib became united under one local political authority." "Abd al-Mu'min briefly presided over a unified North African empire--the first and last in its history under indigenous rule". It would be the high point of Maghribi political unity. Yet twenty years later, by 1184, the revolt in the Balearic Islands

by the Banu Ghaniya

(who claimed to be heirs of the Almoravids) had spread to Ifriqiya and elsewhere, causing severe problems for the Almohad regime, on and off for the next fifty years.

of any established school of law. In practice, however, the Maliki school of law survived and by default worked at the margin. Eventually Maliki jurists came to be recognized in some official fashion, except during the reign of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub

al-Mansur (1184–1199) who was loyal to Ibn Tumart's teachings. Yet the confused status continued to exist on and off, although at the end for the most part to function poorly. After of century of such oscillation, the caliph Abu al-'Ala Idris al-Ma'mun broke with the narrow ideology of the Almohad regimes (first articulated by the mahdi Ibn Tumart); circa 1230, he affirmed the reinstitution of the then-reviving Malikite rite, perennially popular in al-Maghrib.

The Muslim philosophers Ibn Tufayl (Abubacer to the Latins) of Granada (d.1185), and Ibn Rushd (Averroës) of Córdoba (1126–1198), who was also appointed a Maliki judge, were dignitaries known to the Almohad court, whose capital became fixed at Marrakech

The Muslim philosophers Ibn Tufayl (Abubacer to the Latins) of Granada (d.1185), and Ibn Rushd (Averroës) of Córdoba (1126–1198), who was also appointed a Maliki judge, were dignitaries known to the Almohad court, whose capital became fixed at Marrakech

. The Sufi master theologian Ibn 'Arabi was born in Murcia in 1165. Under the Almohads architecture flourished, the Giralda being built in Seville and the pointed arch being introduced.

"There is no better indication of the importance of the Almohad empire than the fascination it has exerted on all subsequent rulers in the Magrib." It was an empire Berber in its inspiration, and whose imperial fortunes were under the direction of Berber leaders. The unitarian Almohads had gradually modified the original ambition of strictly implementing their founder's designs; in this way the Almohads were similar to the preceding Almoravids (also Berber). Yet their movement probably worked to deepen the religious awareness of the Muslim people across the Maghrib. Nonetheless, it could not suppress other traditions and teachings, and alternative expressions of Islam, including the popular cult of saints, the sufis, as well as the Maliki jurists, survived.

The Almohad empire (like its predecessor the Almoravid) eventually weakened and dissolved. Except for the Muslim Kingdom of Granada, Spain was lost. In Morroco, the Almohads were to be followed by the Merinids; in Ifriqiya (Tunisia), by the Hafsids (who claimed to be the heirs of the unitarian Almohads).

(1230-1574) succeeded Almohad rule in Ifriqiya, with the Hafsids claiming to represent the true spiritual heritage of its founder, the Mahdi Ibn Tumart

(c.1077-1130). For a brief moment a Hafsid sovereign would be recognized as the Caliph

of Islam. Tunisia under the Hafsids would eventually regain for a time cultural primacy in the Maghrib.

as governor of Ifriqiya in 1207 and served until his death in 1221. His son, the grandson of Abu Hafs, was Abu Zakariya.

Abu Zakariya

(1203–1249) served the Almohads in Ifriqiya as governor of Gabès

, then in 1226 as governor of Tunis

. In 1229 during disturbances within the Almohad movement, Abu Zakariya declared his independence, having the Mahdi's name declared at Friday prayer, but himself taking the title of Amir: hence, the start of the Hafsid dynasty (1229-1574). In the next few years he secured his hold on the cities of Ifriqiya, then captured Tripolitania

(1234) to the east, and to the west Algiers

(1235) and later Tlemcen

(1242). He solidified his rule among the Berber confederacies. Government structure of the Hafsid state followed the Almohad model, a rather strict hierarchy and centralization. Abu Zakariya's succession to the Almohad movement was acknowledged as the only state maintaining Almohad traditions, and was recognized in Friday prayer by many states in Al-Andalus and in Morocco (including the Merinids). Diplomatic relations were opened with Frederick II

of Sicily, Venice

, Genoa

, and Aragon

. Abu Zakariya the founder of the Hafsids became the foremost ruler in the Maghrib

.

For an historic moment, the son of Abu Zakariya and self-declared caliph of the Hafsids, al-Mustansir (r.1249-1277), was recognised as Caliph

by Mecca and the Islamic world (1259–1261), following termination of the Abbasid

caliphate by the Mongols in 1258. Yet the moment passed as a rival claimant to the title advanced; the Hafsids remained a local sovereignty.

Since their origins with Abu Zakariya the Hafsids had represented their regime as heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi Ibn Tumart, whose name was invoked during Friday prayer at emirate mosques until the 15th century. Hafsid government was accordingly constituted after the Almohad model created by the Mahdi, i.e., it being rigorous hierarchy

Since their origins with Abu Zakariya the Hafsids had represented their regime as heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi Ibn Tumart, whose name was invoked during Friday prayer at emirate mosques until the 15th century. Hafsid government was accordingly constituted after the Almohad model created by the Mahdi, i.e., it being rigorous hierarchy

. The Amir held all power with a code of etiquette surrounding his person, although as sovereign he did not always hold himself aloof. The Amir's counsel was the Ten, composed of the chief Almohad shaiks

. Next in order was the Fifty assembled from petty shaiks, with ordinary shaiks thereafter. The early Hafsids had a censor, the mazwar, who supervised the ranking of the designated shaiks and assigned them to specified categories. Originally there were three ministers [wazir, plural wuzara]: of the army (commander and logistics); of finance (accounting and tax); and, of state (correspondence and police). Over the centuries the office of Hajib increased in importance, at first being major-domo of the palace, then intermdiary between the Amir and his cabinet, and finally de facto the first minister. State authority was publicly asserted by impressive processions: high officials on horseback parading to the sound of kettledrums and tambors, with colorful silk banners held high, all in order to cultivate a regal pomp. In provinces where the Amir enjoyed recognized authority, his governors were usually close family members, assisted by an experienced official. Elsewhere provincial appointees had to contend with strong local oligarchies or leading families. Regarding the rural tribes, various strategies were employed; for those on good terms their tribal shaik might work as a double agent, serving as their representative to the central government, and also as government agent to his fellow tribal members.

In 1270 King Louis IX of France

, whose brother was the king of Sicily, landed an army near Tunis; disease devastated their camp. Later, Hafsid influence was reduced by the rise of the Moroccan Marinids of Fez

, who captured and lost Tunis twice (1347, and 1357). Yet Hafsid fortunes would recover; two notabe rulers being Abu Faris (1394–1434) and his grandson Abu 'Amr 'Uthman (r. 1435-1488).

Toward the end, internal disarray within the Hafsid dynasty created vulnerabilities, while a great power struggle arose between Spaniard and Turk over control of the Mediterranean. The Hafsid dynasts became pawns, subject to the rival strategies of the combatants. By 1574 Ifriqiya had been incorporated into the Ottoman Empire

.

madhhab (school of law) resumed its full traditional jurisdiction over the Maghrib. During the 13th century, the Maliki school had undergone substantial liberalizing changes due in part to Iraqi influence. Under Hafsid jurisprudents the concept of maslahah or "public interest" developed in the operation of their madhhab

. This opened up Maliki fiqh

to considerations of necessity and circumstance with regard to the general welfare of the community. By this means, local custom was admitted in the Sharia

of Malik, to become an integral part of the legal discipline. Later, the Maliki theologian Muhammad ibn 'Arafa (1316–1401) of Tunis studied at the Zaituna library, said to contain 60,000 volumes.

Bedouin Arabs continued to arrive into the 13th century. With their tribal ability to raid and war still intact, they remained problematic and influential. The Arab language came to be predominant, except for a few Berber-speaking areas, e.g., Kharijite Djerba, and the desert south. An unfortunate divide developed between the governance of the cities and that of the countryside; at times the city-based rulers would grant rural tribes autonomy ('iqta') in exchange for their support in intra-maghribi struggles. Yet this tribal independence of the central authority meant also that when the center grew weak, the periphery might still remain strong and resilient.

From al-Andalus

Arab Muslim and Jewish migration continued to come into Ifriqiya, especially after the fall of Granada

in 1492, the last Muslim state ruling on the Iberian peninsula. These newly arriving immigrants brought infusions of their highly developed arts. The well-regarded Andalusian traditions of music

and poetry are found discussed by Ahmad al-Tifasi (1184–1253) of Tunis, in his Muta'at al-Asma' fi 'ilm al-sama [Pleasure to the Ears, on the Art of Music], in volume 41 of his encyclopedia.

As a result of the initial prosperity, Al-Mustansir (r.1249-1277) had transformed the capital city of Tunis

, constructing a palace and the Abu Fihr park; he also created an estate near Bizerte

(said by Ibn Khaldun

to be without equal in the world). Education was improved by the institution of a system of madrasah

. Sufism, e.g., Sidi Bin 'Arus (d. 1463 Tunis) founder of the Arusiyya tariqah

, became increasingly prominent, forming social links between the city and countryside. The Sufi shaikhs began to assume the religious authority once held by the unitarian Almohads, according to Abun-Nasr. Poetry blossomed, as did architecture. For the moment, Tunisia had regained cultural leadership of the Maghrib.

. Perhaps more important was the increase in Mediterranean commerce including trade with Europeans

. Across the region, the repetition of buy and sell dealings with Christians led to the eventual development of trading practices and structured shipping arrangements that were crafted to ensure mutual security, customs revenue, and commercial profit. It was possible for an arriving ship to deliver its goods and pick-up the return cargo in several days time. Christian merchants of the Mediterranean, usually organized by their city-of-origin, set up and maintained their own trading facilities (a funduq) in these North African customs ports to handle the flow of merchandise and marketing.

The principal maritime customs ports were then: Tunis

The principal maritime customs ports were then: Tunis

, Sfax

, Mahdia

, Jerba, and Gabés

(all in Tunisia); Oran

, Bougie

(Bejaia), and Bône

(Annaba) (in Algeria); and Tripoli

(in Libya). At such ports generally, the imports were off loaded and transferred to a customs area from where they were deposited in a sealed wharehouse, or funduq, until the duties and fees were paid. The amount imposed varied, usually five or ten percent. The Tunis customs service

was a stratified bureaucracy. At its head was often a member of the ruling nobility or musharif

, called al-Caid, who not only managed the staff collecting duties

but also might negotiate commercial agreements, conclude treaties, and act as judge

in legal disputes involving foreigners.

Tunis exported grain, dates, olive oil, wool and leather, wax, coral, salt fish, cloth, carpets, arms, and also perhaps black slaves. Imports included cabinet work, arms, hunting birds, wine, perfumes, spices, medical plants, hemp, linen, silk, cotton, many types of cloth, glass ware, metals, hardware, and jewels.

Islamic law

during this era had developed a specific institution to regulate community morals, or hisba

, which included the order and security of public markets, the supervision of market transactions, and related matters. The urban marketplace [Arabic souk, pl. iswak] was generally a street of shops selling the same or similar commodities (vegetables, cloth, metalware, lumber, etc.). The city official charged with these responsibilities was called the muhtasib

.

To achieve public order in the urban markets, the muhtasib would enforce fair commercial dealing (merchants truthfully quoting the local price

to rural people, honest weights and measures, but not quality of goods nor price per se), keep roadways open, regulate the safety of building construction, and monitor the metal value of existing coin

age and the minting of new coin (gold dinars and silver dirhems were minted at Tunis). The authority of the muhtasib, with his group of assistants, was somewhere between a qadi

(judge) and the police, or on other occasions perhaps between a public prosecutor (or trade commissioner) and the mayor (or a high city official). Often a leading judge or mufti

held the position. The muhtasib did not hear contested litigation, but nonetheless could prescribe the pain and humiliation of up to 40 lashes, remand to debtor's prison

, order a shop closed, or expel an offender from the city. However, the civic authority of the muhtasib did not extend into the countryside.

Beginning in the 13th century, from al-Andalus

came Muslim and Jewish immigrants with appreciated talents, e.g., trade connections, agricultural techniques, manufacture, and arts (see below, Society and culture). Yet unfortunately general prosperity was not steady over the centuries of Hafsid rule; there was a sharp economic decline starting in the mid-fourteenth century due to a variety of factors (e.g., agriculture, and the Sahara trade). Under the amir Abu al-'Abbas (1370–1394), Hafsid participation in the Mediterranean trade began to decline, while early corsair raidng activity commenced.

A major social philosopher, Ibn Khaldun

A major social philosopher, Ibn Khaldun

(1332–1406) is recognized as a pioneer in sociology, historiography, and related disciplines. Although having Yemeni ancestry, his family enjoyed centuries-long residency in al-Andalus

before leaving in the 13th century for Ifriqiyah. As a native of Tunis, he spent much of his life under the Hafsids, whose regime he served on occasion.

Ibn Khaldun entered into a political career early on, working under a succession of different rulers of small states, whose designs unfolded amid shifting rivalries and alliances. At one point he rose to vizier

; however, he also spent a year in prison. His career required several relocations, e.g., Fez

, Granada

, eventually Cairo

where he died. In order to write he retired for awhile from active political life. Later, after his pilgrimage to Mecca, he served as Grand Qadi of the Maliki

rite in Egypt (he was appointed and dismissed several times). While he was visiting Damascus

, Tamerlane

took the city; this cruel conquorer interviewed the elderly jurist and social philosopher, yet Ibn Khaldun managed to escape back to his life in Egypt.

.

His seven-volume Kitab al-'Ibar [Book of Examples] (shortened title) is a telescoped "universal" history, which concentrates on the Persian, Arab, and Berber civilizations. Its lengthy prologue, called the Muqaddimah

[Introduction], presents the development of long-term political trends and events as a field for the study, characterizing them as human phenomena, in quasi-sociological terms. It is widely considered to be a gem of sustained cultural analysis. Unfortunately Ibn Khaldun did not attract sufficient interest among local scholars, his studies being neglected in Ifriqiyah; however, in the Persian and Turkish worlds he acquired a sustained following.

In the later books of the Kitab al-'Ibar, he focuses especially on the history of the Berbers of the Maghrib. The perceptive Ibn Khaldun in his narration eventually arrives at historical events he himself witnessed or encountered. As an official of the Hafsids, Ibn Khaldun experienced first hand the effects on the social structure of troubled regimes and the long term decline in the region's fortunes.

Ifriqiya

In medieval history, Ifriqiya or Ifriqiyah was the area comprising the coastal regions of what are today western Libya, Tunisia, and eastern Algeria. This area included what had been the Roman province of Africa, whose name it inherited....

, i.e., Tunisia, and the entire Maghrib

Maghreb

The Maghreb is the region of Northwest Africa, west of Egypt. It includes five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara...

to local Berber rule. The precipitating cause was the departure of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate to their newly conquered territories in Egypt. To govern Ifriqiya in their stead, the Fatimids left the Zirid

Zirid

The Zirid dynasty were a Sanhadja Berber dynasty, originating in modern Algeria, initially on behalf of the Fatimids, for about two centuries, until weakened by the Banu Hilal and finally destroyed by the Almohads. Their capital was Kairouan...

dynasty. Yet the Zirids would eventually break all ties to the Fatimids, even to the point of formally embracing Sunni

Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam. Sunni Muslims are referred to in Arabic as ʾAhl ūs-Sunnah wa āl-Ǧamāʿah or ʾAhl ūs-Sunnah for short; in English, they are known as Sunni Muslims, Sunnis or Sunnites....

doctrines (rivals to the Shi'a).

At this period there arose in the Maghrib two strong local movements dedicated to Muslim purity and practice, one following the other. First, the Almoravids emerged in the far west, i.e., in al-Maghrib al-Aksa (Morocco); although establishing a large empire running from modern Spain to southern Mauretania, Almoravid rule did not reach to the east as far as Ifriqiya. Later another Berber religious leader Ibn Tumart

Ibn Tumart

Abu Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn Tumart was a Berber religious Muslim scholar, teacher and later a political leader from the Masmuda tribe federation. He founded the Berber Almohad dynasty. He is also known as El-Mahdi in reference to his prophesied redeeming...

founded the Almohad

Almohad

The Almohad Dynasty , was a Moroccan Berber-Muslim dynasty founded in the 12th century that established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains in roughly 1120.The movement was started by Ibn Tumart in the Masmuda tribe, followed by Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi between 1130 and his...

movement, which supplanted the Almoravids, and grew to unify under its rule all of the west of Islam, al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

as well as al-Maghrib. In Ifriqiya at the city of Tunis, the Hafsids became the eventual successor to Almohad rule. The Hafsids were a local Berber dynasty, whose own rule would continue for centuries with varying success, until the arrival of the Ottomans in the western Mediterranean.

Berber sovereignty

Following the Fatimids, for the next half millennium Berber IfriqiyaIfriqiya

In medieval history, Ifriqiya or Ifriqiyah was the area comprising the coastal regions of what are today western Libya, Tunisia, and eastern Algeria. This area included what had been the Roman province of Africa, whose name it inherited....

enjoyed self-rule (1048-1574). The Fatimids were Shi'a, specifically of the more controversial Isma'ili branch. They originated in Islamic lands far to the east. Today, and for many centuries, the majority of Tunisians identify as Sunni (also from the east, but who oppose the Shi'a). Yet in Ifriqiyah at the time of the Fatimids, any rule from the east whether Sunni or Shi'a was generally not welcome. Hence the rise in medieval Tunisia (Ifriqiya) of regimes not beholden to the east (al-Mashriq), which marks a new and a popular era of Berber sovereignty.

Berber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

elements around Ifriqiya by appealing to Berber distrust of the Islamic east, here in the form of Aghlabid rule. Thus the Fatimids were ultimately successful in acquiring local state power. Nonetheless, once installed in Ifriqiya, Fatimid rule greatly disrupted social harmony; they imposed high, unorthodox taxes, leading to a Kharijite revolt. Later, the Fatimids of Ifriqiya managed to accomplish their long-held, grand design for the conquest of Islamic Egypt; soon thereafter their leadership relocated to Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

. The Fatimids left the Berber Zirids as their local vassals to govern in the Maghrib. Originally only a client of the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Egypt, the Zirids eventually expelled the Shi'a Fatimids from Ifriqiya. In revenge, the Fatimids sent the disruptive Banu Hilal

Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal were a confederation of Arabian Bedouin tribes that migrated from Upper Egypt into North Africa in the 11th century, having been sent by the Fatimids to punish the Zirids for abandoning Shiism. Other authors suggest that the tribes left the grasslands on the upper Nile because of...

against Ifriqiya, which led to a period of social chaos and economic decline.

The independent Zirid dynasty has been viewed historically as a Berber kingdom; the Zirids were essentially founded by a leader among the Sanhaja

Sanhaja

The Sanhaja or Senhaja were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations of the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and Masmuda...

Berbers. Concurrently, the Sunni Ummayyad Caliphate of Córdoba

Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ruled the Iberian peninsula and part of North Africa, from the city of Córdoba, from 929 to 1031. This period was characterized by remarkable success in trade and culture; many of the masterpieces of Islamic Iberia were constructed in this period, including the famous...

were opposing and battling against the Shi'a Fatimids. Perhaps because Tunisians have long been Sunnis themselves, they may currently evidence faint pride in the Fatimid Caliphate's rôle in Islamic history. In addition to their above grievances against the Fatimids (per the Banu Hilal), during the Fatimid era the prestige of cultural leadership within al-Maghrib shifted decisively away from Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya

In medieval history, Ifriqiya or Ifriqiyah was the area comprising the coastal regions of what are today western Libya, Tunisia, and eastern Algeria. This area included what had been the Roman province of Africa, whose name it inherited....

and instead came to be the prize of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

.

During the interval of generally disagreeable Shi'a rule, the Berber people appear to have ideologically moved away from a popular antagonism against the Islamic east (al-Mashriq), and toward an acquiescence to its Sunni orthodoxy, though of course mediated by their own Maliki

Maliki

The ' madhhab is one of the schools of Fiqh or religious law within Sunni Islam. It is the second-largest of the four schools, followed by approximately 25% of Muslims, mostly in North Africa, West Africa, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and in some parts of Saudi Arabia...

school of law (viewed as one of the four orthodox madhhab

Madhhab

is a Muslim school of law or fiqh . In the first 150 years of Islam, there were many such "schools". In fact, several of the Sahābah, or contemporary "companions" of Muhammad, are credited with founding their own...

by the Sunni). Professor Abdallah Laroui remarks that while enjoying sovereignty the Berber Maghrib experimented with several doctrinal viewpoints during the 9th to the 13th centuries, including the Khariji, Zaydi, Shi'a, and Almohad

Almohad

The Almohad Dynasty , was a Moroccan Berber-Muslim dynasty founded in the 12th century that established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains in roughly 1120.The movement was started by Ibn Tumart in the Masmuda tribe, followed by Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi between 1130 and his...

. Eventually they settled on an orthodoxy, on Maliki Sunni doctrines. This progression indicates a grand period of Berber self-definition.

Tunis under the Almohads would become the permanent capital of Ifriqiya. The social discord between Berber and Arab would move toward resolution. In fact it might be said that the history of the Ifriqiya prior to this period was prologue, which merely set the stage; henceforth, the memorable events acted on that stage would come to compose the History of Tunisia for its modern people. Prof. Perkins mentions the preceding history of rule from the east (al-Mashriq), and comments that following the Fatimids departure there arose in Tunisia an intent to establish a "Muslim state geared to the interests of its Berber majority." Thus commenced the medieval era of their sovereignty.

Result of migrations

{Under construction}Twenty or so Berber languages

Berber languages

The Berber languages are a family of languages indigenous to North Africa, spoken from Siwa Oasis in Egypt to Morocco , and south to the countries of the Sahara Desert...

(also called Tamazight) are spoken in North Africa. Berber speakers were once predominate over all this large area, but as a result of Arabization

Arabized Berber

Arabized Berber is a term to denote an inhabitant of the North African Maghreb of Berber origin whose native language is a dialect of Arabic. According to these persons, the Arab identity in North Africa is a myth coming from the Arabization of the official institutions after French rule.They...

and later local migrations, today Berber languages are reduced to several large regions (in Morocco, Algeria, and the central Sahara) or remain as smaller language islands. Several linguists characterize the Berber spoken as one language with many dialect variations, spread out in discrete regions, without ongoing standardization. The Berber languages may be classified as follows (with some more widely known languages or language groups shown in italics). Ethnic historical correspondence is suggested by the designation |Tribe|.

- I. GuancheGuanche languageGuanche is an extinct language that was spoken by the Guanches of the Canary Islands until the 16th or 17th century. It is only known today through a few sentences and individual words recorded by early travellers, supplemented by several placenames, as well as some words assimilated into the...

[extinct] - (Canary IslandsCanary IslandsThe Canary Islands , also known as the Canaries , is a Spanish archipelago located just off the northwest coast of mainland Africa, 100 km west of the border between Morocco and the Western Sahara. The Canaries are a Spanish autonomous community and an outermost region of the European Union...

). - II. Old LibyanAncient LibyaThe Latin name Libya referred to the region west of the Nile Valley, generally corresponding to modern Northwest Africa. Climate changes affected the locations of the settlements....

[extinct] - (West of ancient EgyptAncient EgyptAncient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

). - III. Berber Proper.

- A. EasternEastern Berber languagesThe Eastern Berber languages belong to the Afro-Asiatic family and are spoken in Libya and Egypt. They include Awjila, Sokna and Fezzan , Siwi, and Ghadamès. Kossmann divides them into two groups:...

: Siwa, AwjilaAwjilah languageAwjila is a Berber language spoken in Cyrenaica, Libya, in the Awjila oasis. UNESCO considers Awjilah to be seriously endangered as the youngest speakers have reached or passed middle age.-References:* *...

, SoknaSawknah languageSokna or Sawknah is a Berber language spoken in the town of Sokna and the village of Fuqaha in northeastern Fezzan in Libya. The most extensive and recent materials on it are Sarnelli for Sokna and Paradisi for El-Fogaha...

- (LibyaLibyaLibya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

& EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

). - B. Tuareg - (Central SaharaSaharaThe Sahara is the world's second largest desert, after Antarctica. At over , it covers most of Northern Africa, making it almost as large as Europe or the United States. The Sahara stretches from the Red Sea, including parts of the Mediterranean coasts, to the outskirts of the Atlantic Ocean...

region). |Sanhaja| - C. Western: ZenagaZenaga languageZenaga is a Berber language spoken by some 200 people between Mederdra and the Atlantic coast in southwestern Mauritania. The language shares its basic structure with other Berber languages, but specific details are quite different; in fact, it is probably the most divergent surviving Berber...

- (MauritaniaMauritaniaMauritania is a country in the Maghreb and West Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean in the west, by Western Sahara in the north, by Algeria in the northeast, by Mali in the east and southeast, and by Senegal in the southwest...

& SenegalSenegalSenegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

). |Sanhaja| - D. Northern Berber languagesNorthern-Geography:* Northern , various regions, states, territories, etc.* Northern Range, a range of hills in Trinidad* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States-Education:* Northern University , various institutions...

- (MaghribMaghrebThe Maghreb is the region of Northwest Africa, west of Egypt. It includes five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara...

).- 1. AtlasAtlas languagesThe Atlas languages, or more exactly Moroccan Atlas, also Masmuda, are a subgroup of the Northern Berber languages spoken in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. By mutual intelligibility, they are a single language; however, they are distinct sociolinguistically and are considered separate languages by...

: Shilha, Central Morocco TamazightCentral Morocco TamazightCentral Atlas Tamazight is a Berber languageCentral Atlas Tamazight may be referred to as either a Berber language or a Berber dialect...

- (MoroccoMoroccoMorocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

& AlgeriaAlgeriaAlgeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

). |Masmuda| - 2. KabyleKabyle languageKabyle or Kabylian is a Berber language spoken by the Kabyle people north and northeast of Algeria. Estimates about the number of speakers range from 5 million to about 7 million speakers worldwide, the majority in Algeria.-Classification:The classification of Kabyle is Afro-Asiatic, Berber and...

- (East of AlgiersAlgiers' is the capital and largest city of Algeria. According to the 1998 census, the population of the city proper was 1,519,570 and that of the urban agglomeration was 2,135,630. In 2009, the population was about 3,500,000...

). |Sanhaja| - 3. ZenatiZenati languagesThe Zenati languages, named after the medieval Zenata tribe, are a subgroup of the Northern Berber language family, spoken in North Africa, proposed in Destaing They are distributed across the central Maghreb, from northeastern Morocco to just west of Algiers, and the northern Sahara, from...

- (Morocco, Algeria, & TunisiaTunisiaTunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

). |Zenata|

- 1. Atlas

- A. Eastern

Nota Bene: The classification and nomenclature of Berber languages lack complete consensus.

Script, writings

{Under construction}The Libyan

Ancient Libya

The Latin name Libya referred to the region west of the Nile Valley, generally corresponding to modern Northwest Africa. Climate changes affected the locations of the settlements....

Berbers developed their own writing system, evidently derived from Phoenician, as early as the 4th century BC. It was a boustrophic script, i.e., written left to right then right to left on alternating lines, or up and down in columns. Most of these early inscriptions were funerary and short in length. Several longer texts exist, taken from Thugga, modern Dougga, Tunisia. Both are bilingual, being written in Punic with its letters and in Berber with its letters

Tifinagh

Tifinagh is a series of abjad and alphabetic scripts used by some Berber peoples, notably the Tuareg, to write their language.A modern derivate of the traditional script, known as Neo-Tifinagh, was introduced in the 20th century...

. One throws some light on the governing institutions of the Berbers in the 2nd century BC. The other text begins: "This temple the citizens of Thugga built for King Masinissa

Masinissa

Masinissa — also spelled Massinissa and Massena — was the first King of Numidia, an ancient North African nation of ancient Libyan tribes. As a successful general, Masinissa fought in the Second Punic War , first against the Romans as an ally of Carthage an later switching sides when he saw which...

... ." Today the script descendent from the ancient Libyan remains in use; it is called Tifinagh

Tifinagh

Tifinagh is a series of abjad and alphabetic scripts used by some Berber peoples, notably the Tuareg, to write their language.A modern derivate of the traditional script, known as Neo-Tifinagh, was introduced in the 20th century...

.

Zenata

Zenata were an ethnic group of North Africa, who were technically an Eastern Berber group and who are found in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco....

Berbers became Arabized. Today in Tunisia the small minority that speaks Berber may be heard on Jerba island, around the salt lakes

Tunisian salt lakes

The Tunisian salt lakes are a series of lakes in central Tunisia, lying south of the Atlas Mountains at the northern edge of the Sahara. The lakes include, from east to west, the Chott el Fedjedji, Chott el Djerid, and Chott el Gharsa....

region, and near the desert

Grand Erg Oriental

The Grand Erg Oriental is a large erg in the Sahara desert. Situated for the most part in Saharan lowlands of northeast Algeria, the Grand Erg Oriental covers an area some 600 km wide by 200 km north to south...

, as well as along the mountainous

Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains is a mountain range across a northern stretch of Africa extending about through Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The highest peak is Toubkal, with an elevation of in southwestern Morocco. The Atlas ranges separate the Mediterranean and Atlantic coastlines from the Sahara Desert...

border with Algeria (across this frontier to the west lies a large region where the Zenati

Zenati languages

The Zenati languages, named after the medieval Zenata tribe, are a subgroup of the Northern Berber language family, spoken in North Africa, proposed in Destaing They are distributed across the central Maghreb, from northeastern Morocco to just west of Algiers, and the northern Sahara, from...

Berber languages and dialects predominate). In contrast, use of Berber is relatively common in Morocco, and also in Algeria, and in the remote central Sahara. Berber poetry endures, as well as a traditional Berber literature.

Berber tribal affiliations

{Under construction}The grand tribal identities of Berber antiquity were said to be the Mauri

Mauri

Mauri may refer to:*Mauri meaning the life force which all objects contain, in the Māori language of New Zealand and the Rotuman language of Rotuma*Mauri, or Maurya Empire, an ancient caste in India which built its greatest empire...

, the Numidians

Numidians

The Numidians were Berber tribes who lived in Numidia, in Algeria east of Constantine and in part of Tunisia. The Numidians were one of the earliest natives to trade with the settlers of Carthage. As Carthage grew, the relationship with the Numidians blossomed. Carthage's military used the Numidian...

, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauritania, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians were located between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both had large sedentary

Sedentism

In evolutionary anthropology and archaeology, sedentism , is a term applied to the transition from nomadic to permanent, year-round settlement.- Requirements for permanent settlements :...

populations. The Gaetulians were less settled, with large pastoral

Pastoral

The adjective pastoral refers to the lifestyle of pastoralists, such as shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasturage. It also refers to a genre in literature, art or music that depicts such shepherd life in an...

elements, and lived in the near south on the margins of the Sahara. The medieval historian of the Maghrib, Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldūn or Ibn Khaldoun was an Arab Tunisian historiographer and historian who is often viewed as one of the forerunners of modern historiography, sociology and economics...

, is credited or blamed for theorizing a causative dynamic to the different tribal confederacies over time. Issues concerning tribal social-economies and their influence have generated a large literature, which critics say is overblown. Abdallah Laroui discounts the impact of tribes, declaring the subject a form of obfuscation which cloaks suspect colonial ideologies. While Berber tribal society has made an impact on culture and government, their continuance was chiefly due to strong foreign interference which usurped the primary domain of the government institutions, and derailed their natural political development. Rather than there being a predisposition for tribal structures, the Berber's survival strategy in the face of foreign occupation was to figuratively retreat into their own way of life through their enduring tribal networks. On the other hand, as it is accepted and understood, tribal societies in the Middle East have continued over millennia and from time to time flourish.

Berber tribal identities survived undiminished during the long period of dominance by the city-state of Carthage. Under centuries of Roman rule also tribal ways were maintained. The sustaining social customs would include: communal self-defense and group liability, marriage alliances, collective religious practices, reciprocal gift-giving, family working relationships and wealth. Abdallah Laroui summarizes the abiding results under foreign rule (here, by Carthage and by Rome) as: Social (assimilated, nonassimilated

Cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is a socio-political response to demographic multi-ethnicity that supports or promotes the assimilation of ethnic minorities into the dominant culture. The term assimilation is often used with regard to immigrants and various ethnic groups who have settled in a new land. New...

, free); Geographical (city, country, desert); Economic (commerce, agriculture, nomadism); and, Linguistic (e.g., Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, Punico-Berber, Berber).

During the initial centuries of the Islamic era, it was said that the Berbers tribes were divided into two blocs, the Butr (Zanata and allies) and the Baranis (Sanhaja, Masmuda, and others). The etymology

Etymology

Etymology is the study of the history of words, their origins, and how their form and meaning have changed over time.For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts in these languages and texts about the languages to gather knowledge about how words were used during...

is unclear, perhaps deriving from tribal customs for clothing ("abtar" and "burnous"), or perhaps words coined to distinguish the nomad (Butr) from the farmer (Baranis). The Arabs drew most of their early recruits from the Butr. Later, legends arose which spoke of an obscure, ancient invasion of North Africa by the Himyarite Arabs of Yemen

South Arabia

South Arabia as a general term refers to several regions as currently recognized, in chief the Republic of Yemen; yet it has historically also included Najran, Jizan, and 'Asir which are presently in Saudi Arabia, and Dhofar presently in Oman...

, from which a prehistoric ancestry was evidently fabricated: Berber descent from two brothers, Burnus and Abtar, who were sons of Barr, the grandson of Canaan

Canaan

Canaan is a historical region roughly corresponding to modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and the western parts of Jordan...

(Canaan being the grandson of Noah

Noah

Noah was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the tenth and last of the antediluvian Patriarchs. The biblical story of Noah is contained in chapters 6–9 of the book of Genesis, where he saves his family and representatives of all animals from the flood by constructing an ark...

through his son Ham

Ham, son of Noah

Ham , according to the Table of Nations in the Book of Genesis, was a son of Noah and the father of Cush, Mizraim, Phut and Canaan.- Hebrew Bible :The story of Ham is related in , King James Version:...

). Both Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldūn or Ibn Khaldoun was an Arab Tunisian historiographer and historian who is often viewed as one of the forerunners of modern historiography, sociology and economics...

(1332–1406) and Ibn Hazm

Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ) was an Andalusian philosopher, litterateur, psychologist, historian, jurist and theologian born in Córdoba, present-day Spain...

(994-1064) as well as Berber genealogists

Genealogy

Genealogy is the study of families and the tracing of their lineages and history. Genealogists use oral traditions, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kinship and pedigrees of its members...

held that the Himyarite Arab ancestry was totally unacceptable. This legendary ancestry, however, played a rôle in the long Arabization

Arabized Berber

Arabized Berber is a term to denote an inhabitant of the North African Maghreb of Berber origin whose native language is a dialect of Arabic. According to these persons, the Arab identity in North Africa is a myth coming from the Arabization of the official institutions after French rule.They...

process that continued for centuries among the Berber peoples.

Sanhaja

The Sanhaja or Senhaja were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations of the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and Masmuda...

, and the Masmuda

Masmuda

The Masmuda were a Berber tribal confederacy of Morocco and one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and the Sanhaja. They were composed of several sub-tribes: The Berghouatas, Ghumaras , Hintatas , Tinmelel, Hergha, Genfisa, Seksiwa, Gedmiwa, Hezerdja, Urika, Guerouanes, Bni...

. These tribal divisions are mentioned by Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406). The Zanata early on allied more closely with the Arabs and consequently became more Arabized, although Znatiya Berber is still spoken in small islands across Algeria and in northern Morocco (the Rif

Rif

The Rif or Riff is a mainly mountainous region of northern Morocco, with some fertile plains, stretching from Cape Spartel and Tangier in the west to Ras Kebdana and the Melwiyya River in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the river of Wergha in the south.It is part of the...

and north Middle Atlas

Middle Atlas

The Middle Atlas is part of the Atlas mountain range lying in Morocco, a mountainous country with more than 100,000 km² or 15% of its landmass rising above 2,000 metres. The Middle Atlas is the northernmost of three Atlas Mountains chains that define a large plateaued basin extending eastward...

). The Sanhaja are also widely dispersed throughout the Maghrib, among which are: the sedentary Kabyle

Kabyle people

The Kabyle people are the largest homogeneous Algerian ethno-cultural and linguistical community and the largest nation in North Africa to be considered exclusively Berber. Their traditional homeland is Kabylie in the north of Algeria, one hundred miles east of Algiers...

on the coast west of modern Algiers

Algiers

' is the capital and largest city of Algeria. According to the 1998 census, the population of the city proper was 1,519,570 and that of the urban agglomeration was 2,135,630. In 2009, the population was about 3,500,000...

, the nomadic Zanaga

Zanaga

Zanaga is a city and capital of Zanaga District in the Lékoumou Region of northeastern Republic of the Congo.It lies on the Ogooue River which flows north-west into Gabon.- External links :*...

of southern Morocco (the south Anti-Atlas

Anti-Atlas

The Anti-Atlas or Lesser Atlas or Little Atlas, is a mountain range in Morocco, a part of the Atlas mountains in the northwest of Africa. The Anti-Atlas extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the southwest toward the northeast, to the heights of Ouarzazate and further east to the city of Tafilalt,...

) and the western Sahara to Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

, and the Tuareg (al-Tawarik), the well-known camel breeding nomads of the central Sahara

Sahara

The Sahara is the world's second largest desert, after Antarctica. At over , it covers most of Northern Africa, making it almost as large as Europe or the United States. The Sahara stretches from the Red Sea, including parts of the Mediterranean coasts, to the outskirts of the Atlantic Ocean...

. The descendants of the Masmuda are sedentary

Sedentism

In evolutionary anthropology and archaeology, sedentism , is a term applied to the transition from nomadic to permanent, year-round settlement.- Requirements for permanent settlements :...

Berbers of Morocco, in the High Atlas

High Atlas

High Atlas, also called the Grand Atlas Mountains is a mountain range in central Morocco in Northern Africa.The High Atlas rises in the west at the Atlantic Ocean and stretches in an eastern direction to the Moroccan-Algerian border. At the Atlantic and to the southwest the range drops abruptly...

, and from Rabat

Rabat

Rabat , is the capital and third largest city of the Kingdom of Morocco with a population of approximately 650,000...

inland to Azru and Khanifra, the most populous of the modern Berber regions.

Medieval events in Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya

In medieval history, Ifriqiya or Ifriqiyah was the area comprising the coastal regions of what are today western Libya, Tunisia, and eastern Algeria. This area included what had been the Roman province of Africa, whose name it inherited....

and al-Maghrib

Maghreb

The Maghreb is the region of Northwest Africa, west of Egypt. It includes five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara...

often have tribal assoiciations. Linked to the Kabyle Sanhaja were the Kutama

Kutama

The Kutama were a powerful Berber tribe, in the region of Jijel , a member of the great Sanhaja confederation of the Maghrib and the armed body of the Fatimid Caliphate.-Origins of the Kutama:...

tribes, whose support worked to establish the Fatimid Caliphate

Fatimid

The Fatimid Islamic Caliphate or al-Fāṭimiyyūn was a Berber Shia Muslim caliphate first centered in Tunisia and later in Egypt that ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Sudan, Sicily, the Levant, and Hijaz from 5 January 909 to 1171.The caliphate was ruled by the Fatimids, who established the...

(909-1171, only until 1049 in Ifriqiya); their vassals and later successors in Ifriqiya the Zirids (973-1160) were also Sanhaja. The Almoravids

Almoravids

The Almoravids were a Berber dynasty of Morocco, who formed an empire in the 11th-century that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus. Their capital was Marrakesh, a city which they founded in 1062 C.E...

(1056–1147) first began far south of Morocco, among the Lamtuna

Lamtuna

The Lamtuna were a powerful nomadic Berber tribe belonging to the Senhaja inhabiting the western Sahara.During the eighth century the Lamtuna created a kingdom out of a confederation of Berber tribes, which they dominated until the early tenth century. The Lamtuna probably did not convert to Islam...

Sanhaja. From the Masmuda came Ibn Tumart

Ibn Tumart

Abu Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn Tumart was a Berber religious Muslim scholar, teacher and later a political leader from the Masmuda tribe federation. He founded the Berber Almohad dynasty. He is also known as El-Mahdi in reference to his prophesied redeeming...

and the Almohad movement (1130–1269), later supported by the Sanhaja. Accordingly, it was from among the Masmuda that the Hafsid dynasty

Hafsid dynasty

The Hafsids were a Berber dynasty ruling Ifriqiya from 1229 to 1574. Their territories were stretched from east of modern Algeria to west of modern Libya during their zenith.-History:...

(1227-1574) of Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

originated.

Under the Fatimids

Zirid

The Zirid dynasty were a Sanhadja Berber dynasty, originating in modern Algeria, initially on behalf of the Fatimids, for about two centuries, until weakened by the Banu Hilal and finally destroyed by the Almohads. Their capital was Kairouan...

dynasty (972-1148) began their rule as agents of the Shi'a Fatimids (909-1171), who had conquered Egypt in 969. After removing their capital to Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

from Mahdiya in Ifriqiya, the Fatimids also withdrew from direct governance of al-Maghrib, which they delegated to a local vassal. Their Maghriban power, however, was not transferred to a loyal Kotama

Kutama

The Kutama were a powerful Berber tribe, in the region of Jijel , a member of the great Sanhaja confederation of the Maghrib and the armed body of the Fatimid Caliphate.-Origins of the Kutama:...

Berber, which tribe had provided crucial support to the Fatimids during their rise. Instead authority was given to a chief from among the Sanhaja

Sanhaja

The Sanhaja or Senhaja were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations of the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and Masmuda...

Berber confederacy of the central Magrib, Buluggin ibn Ziri

Buluggin ibn Ziri