History of perpetual motion machines

Encyclopedia

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

. For millennia, it was not clear whether perpetual motion

Perpetual motion

Perpetual motion describes hypothetical machines that operate or produce useful work indefinitely and, more generally, hypothetical machines that produce more work or energy than they consume, whether they might operate indefinitely or not....

devices were possible or not, but the development of modern theories of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a physical science that studies the effects on material bodies, and on radiation in regions of space, of transfer of heat and of work done on or by the bodies or radiation...

has indicated that they are impossible. Despite this, many attempts have been made to construct such machines, continuing into modern times. Modern designers and proponents often use other terms, such as "over-unity", to describe their inventions.

History

Kinds of perpetual motion machines |

There are two types of perpetual motion machines:

|

Pre-1800s

The "magic wheelMagic wheel

The magic wheel, or magnetic wheel is a wheel that continues to spin for a long time after being started, and is one of the earliest examples of an attempt at a perpetual motion machine. This device was invented in medieval Bavaria. It looked like a wagon wheel spinning on an axle, affixed to a base...

", a wheel spinning on its axle powered by lodestones, appeared in 8th century Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

. The wheel was supposed to rotate perpetually; in fact, it did rotate for a long time, but friction inevitably eventually stopped it. Early designs of perpetual motion machines were done by Indian mathematician

Indian mathematics

Indian mathematics emerged in the Indian subcontinent from 1200 BCE until the end of the 18th century. In the classical period of Indian mathematics , important contributions were made by scholars like Aryabhata, Brahmagupta, and Bhaskara II. The decimal number system in use today was first...

–astronomer Bhaskara II, who described a wheel (Bhāskara's wheel

Bhaskara's wheel

Bhāskara's wheel was invented in 1150 by Bhāskara II, an Indian mathematician, in an attempt to create a perpetual motion machine. The wheel consisted of curved or tilted spokes partially filled with mercury. Once in motion, the mercury would flow from one side of the spoke to another, thus forcing...

) that he claimed would run forever.

A drawing of a perpetual motion machine appeared in the sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt

Villard de Honnecourt

Villard de Honnecourt was a 13th-century artist from Picardy in northern France. He is known to history only through a surviving portfolio of 33 sheets of parchment containing about 250 drawings dating from the 1220s/1240s, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris...

, a 13th century French master mason and architect. The sketchbook was concerned with mechanics

Mechanics

Mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of physical bodies when subjected to forces or displacements, and the subsequent effects of the bodies on their environment....

and architecture

Architecture

Architecture is both the process and product of planning, designing and construction. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural and political symbols and as works of art...

. Following the example of Villard, Peter of Maricourt

Peter of Maricourt

Pierre Pelerin de Maricourt , Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt or Peter Peregrinus of Maricourt; was a 13th century French scholar who conducted experiments on magnetism and wrote the first extant treatise describing the properties of magnets...

designed a magnetic globe which, if it were mounted without friction parallel to the celestial axis, would rotate once a day. It was intended to serve as an automatic armillary sphere

Armillary sphere

An armillary sphere is a model of objects in the sky , consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centred on Earth, that represent lines of celestial longitude and latitude and other astronomically important features such as the ecliptic...

.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance...

made a number of drawings of devices he hoped would make free energy

Energy

In physics, energy is an indirectly observed quantity. It is often understood as the ability a physical system has to do work on other physical systems...

. Leonardo da Vinci was generally against such devices, but drew and examined numerous overbalanced wheels.

Mark Anthony Zimara, a 16th century Italian scholar, proposed a self-blowing windmill.

Various scholars in this period investigated the topic. Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal , was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, writer and Catholic philosopher. He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen...

introduced a primitive form of roulette

Roulette

Roulette is a casino game named after a French diminutive for little wheel. In the game, players may choose to place bets on either a single number or a range of numbers, the colors red or black, or whether the number is odd or even....

and the roulette wheel in the 17th century in his search for a perpetual motion machine. Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

devised the "perpetual vase" ("perpetual goblet" or "hydrostatic paradox") which was discussed by Denis Papin in the Philosophical Transactions for 1685. Johann Bernoulli

Johann Bernoulli

Johann Bernoulli was a Swiss mathematician and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family...

proposed a fluid energy machine. In 1686, Georg Andreas Böckler

Georg Andreas Böckler

Georg Andreas Böckler was a German architect and engineer who wrote Architectura Curiosa Nova and Theatrum Machinarum Novum ....

, designed a "self operating" self-powered water mill and several perpetual motion machines using balls using variants of Archimedes screws. In 1712, Johann Bessler

Johann Bessler

Johann Ernst Elias Bessler was a German entrepreneur who demonstrated a series of devices that he claimed exhibited perpetual motion.-Life and career:...

(Orffyreus), investigated 300 different perpetual motion models and claimed he had the secret of perpetual motion. Though allegation of fraud surfaced later (from a maid in his employment), investigators at the time, such as the lawyer Willem Jacob s'Gravesande, reported no such fraud.

In the 1760s, James Cox

James Cox (inventor)

James Cox was a British jeweller, goldsmith and entrepreneur best known for creating mechanical clocks, including Cox's timepiece and the Peacock Clock from the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg....

and John Joseph Merlin

John Joseph Merlin

John-Joseph Merlin was a Belgian inventor and horologist.He was born Jean-Joseph Merlin in 1735 in the city of Huy, Belgium....

developed the Cox's timepiece

Cox's timepiece

Cox's timepiece is a clock developed in the 1760s by James Cox. It was developed in collaboration with John Joseph Merlin . Cox claimed that his design was a true perpetual motion machine, but as the device is powered from changes in atmospheric pressure via a mercury barometer, this is not the case...

. Cox claimed the timepiece a true perpetual motion machine, but as the device is powered from changes in atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure is the force per unit area exerted into a surface by the weight of air above that surface in the atmosphere of Earth . In most circumstances atmospheric pressure is closely approximated by the hydrostatic pressure caused by the weight of air above the measurement point...

via a mercury barometer, this is not the case.

In 1775, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research...

, made the statement that the Academy "will no longer accept or deal with proposals concerning perpetual motion." The reasoning was that perpetual motion is impossible to achieve and that the search for it is time consuming and very expensive. According to the members of the academy, those bright minds dedicating their time and resources to this search, could be utilized much better in other, more reasonable endeavors. Nevertheless, many individuals continued to propose and build various "perpetual" machines, in a quest of attaining their end goal of free energy. An example is Doctor Conradus Schiviers (1790). Schiviers made a belt-driven wheel in which several balls powered a water wheel and a bucket-chain (again raising the balls). Others tried to adapt his designs unsuccessfully a century later.

1800s

In 1812, Charles RedhefferCharles Redheffer

Charles Redheffer was an American inventor who claimed to have invented a perpetual motion machine. First appearing in Philadelphia, Redheffer exhibited his machine to the public, charging high prices for viewing. When he applied to the government for more money, a group of inspectors were sent to...

, in Philadelphia, claimed to have developed a "generator" that could power other machines. Upon investigation, it was deduced that the power was being routed from the other connected machine. Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the first commercially successful steamboat...

exposed Redheffer's schemes during an exposition of the device in New York City (1813). Removing some concealing wooden strips, Fulton found a cat-gut belt drive went through a wall to an attic. In the attic, a man was turning a crank to power the device.

In 1827, Sir William Congreve, 2nd Baronet devised a machine running on capillary action

Capillary action

Capillary action, or capilarity, is the ability of a liquid to flow against gravity where liquid spontanously rise in a narrow space such as between the hair of a paint-brush, in a thin tube, or in porous material such as paper or in some non-porous material such as liquified carbon fiber, or in a...

that would disobey the law of never rising above their own level, so to produce a continuous ascent and overflow. The device had an inclined plane over pulleys. At the top and bottom, there travelled an endless band of sponge, a bed and, over this, again an endless band of heavy weights jointed together. The whole stood over the surface of still water. Congreve believed his system would operate continuously.

In 1868, an Austrian, Alois Drasch, received a US patent for a machine that possessed a "thrust key-type gear

Gear

A gear is a rotating machine part having cut teeth, or cogs, which mesh with another toothed part in order to transmit torque. Two or more gears working in tandem are called a transmission and can produce a mechanical advantage through a gear ratio and thus may be considered a simple machine....

ing" of a rotary engine

Rotary engine

The rotary engine was an early type of internal-combustion engine, usually designed with an odd number of cylinders per row in a radial configuration, in which the crankshaft remained stationary and the entire cylinder block rotated around it...

. The vehicle driver could tilt a trough depending upon need. A heavy ball rolled in a cylindrical trough downward, and, with continuous adjustment of the device's levers and power output, Drasch believed that it would be possible to power a vehicle.

In 1870, E. P. Willis of New Haven, Connecticut made money from a "proprietary" perpetual motion machine. A story of the overly complicated device with a hidden source of energy appears in Scientific American

Scientific American

Scientific American is a popular science magazine. It is notable for its long history of presenting science monthly to an educated but not necessarily scientific public, through its careful attention to the clarity of its text as well as the quality of its specially commissioned color graphics...

article "The Greatest Discovery Ever Yet Made." Investigation into the device eventually found a source of power that drove it.

John Ernst Worrell Keely

John Ernst Worrell Keely

John Ernst Worrell Keely was a US inventor from Philadelphia who claimed to have discovered a new motive power which was originally described as "vaporic" or "etheric" force, and later as an unnamed force based on "vibratory sympathy", by which he produced "interatomic ether" from water and air...

claimed the invention of an induction resonance motion motor. He explained that he used "etheric technology". In 1872, Keely announced that he had discovered a principle for power production based on the vibrations of tuning fork

Tuning fork

A tuning fork is an acoustic resonator in the form of a two-pronged fork with the prongs formed from a U-shaped bar of elastic metal . It resonates at a specific constant pitch when set vibrating by striking it against a surface or with an object, and emits a pure musical tone after waiting a...

s. Scientists investigated his machine which appeared to run on water, though Keely endeavored to avoid this. Shortly after 1872, venture capitalists accused Keely of fraud (they lost nearly five million dollars). Keely's machine, it was discovered after his death, was based on hidden air pressure tubes.

In 1881, John Gamgee developed a liquid ammonia machine which could operate at the boiling point from vapor

Vapor

A vapor or vapour is a substance in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critical point....

ation by radiant heat. The resultant expansion would drive a piston. The vapor does not condense to liquid to start the cycle over again, however, thus making the system inoperable. The Navy approved of the device and showed it to President James Garfield.

1900 to 1950

In 1900, Nikola TeslaNikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla was a Serbian-American inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer...

claimed to have discovered an abstract principle on which to base a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. No prototype was produced. He wrote:

By 1903, 600 English perpetual motion patents had been granted. A design patented in the early years of the 20th century involved a cable

Cable

A cable is two or more wires running side by side and bonded, twisted or braided together to form a single assembly. In mechanics cables, otherwise known as wire ropes, are used for lifting, hauling and towing or conveying force through tension. In electrical engineering cables are used to carry...

projecting 150 mile

Mile

A mile is a unit of length, most commonly 5,280 feet . The mile of 5,280 feet is sometimes called the statute mile or land mile to distinguish it from the nautical mile...

s into the sky to induct

Electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic induction is the production of an electric current across a conductor moving through a magnetic field. It underlies the operation of generators, transformers, induction motors, electric motors, synchronous motors, and solenoids....

electricity (technology at the time would limit its usefulness, as it weighed

Weight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force on the object due to gravity. Its magnitude , often denoted by an italic letter W, is the product of the mass m of the object and the magnitude of the local gravitational acceleration g; thus:...

80 ton

Ton

The ton is a unit of measure. It has a long history and has acquired a number of meanings and uses over the years. It is used principally as a unit of weight, and as a unit of volume. It can also be used as a measure of energy, for truck classification, or as a colloquial term.It is derived from...

s) and to be held up by the aether

Aether theories

Aether theories in early modern physics proposed the existence of a medium, the aether , a space-filling substance or field, thought to be necessary as a transmission medium for the propagation of electromagnetic waves...

.

In the 1910s and 1920s, Harry Perrigo of Kansas City, Missouri, a graduate of MIT, claimed development of a free energy device. Perrigo claimed the energy source was "from thin air" or from aether waves. Perrigo demonstrated the device before the Congress of the United States on December 15, 1917. Perrigo had a pending application for the "Improvement in Method and Apparatus for Accumulating and Transforming Ether Electric Energy". Investigators report that his device contained a hidden motor battery.

Popular Science

Popular Science

Popular Science is an American monthly magazine founded in 1872 carrying articles for the general reader on science and technology subjects. Popular Science has won over 58 awards, including the ASME awards for its journalistic excellence in both 2003 and 2004...

, in the October 1920 issue, published an article on the lure of perpetual motion.

In 1917, John Andrews, a Portuguese chemist, had a green powder which he claimed and demonstrated could transform water into gas (referred to as a "gas-water additive"). He reportedly convinced a Navy official that it worked. Andrews disappeared after negotiations began. Andrews' laboratory was rummaged through and disheveled upon a return visit by United States Navy officials. Also in 1917, Garabed T. K. Giragossian

Garabed T. K. Giragossian

Garabed T. K. Giragossian was an Armenian living in Boston who is remembered for developing a perpetual motion device shortly after the turn of the 19th century. He immigrated to America in 1891. In 1917, Giragossian claimed, reportedly fraudulently, to have developed a "free energy machine". The...

is claimed, reportedly fraud

Fraud

In criminal law, a fraud is an intentional deception made for personal gain or to damage another individual; the related adjective is fraudulent. The specific legal definition varies by legal jurisdiction. Fraud is a crime, and also a civil law violation...

ulently, to have developed a free energy machine. Supposedly involved in a conspiracy

Conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory explains an event as being the result of an alleged plot by a covert group or organization or, more broadly, the idea that important political, social or economic events are the products of secret plots that are largely unknown to the general public.-Usage:The term "conspiracy...

, Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

signed a resolution offering him protection. The device was a giant flywheel

Flywheel

A flywheel is a rotating mechanical device that is used to store rotational energy. Flywheels have a significant moment of inertia, and thus resist changes in rotational speed. The amount of energy stored in a flywheel is proportional to the square of its rotational speed...

that was charged up with energy slowly and put out a large amount of energy for just a second.

A series of designs were developed in the 1920s. During this period, Thomas Henry Moray

Thomas Henry Moray

Thomas Henry Moray was an inventor from Salt Lake City, Utah.Moray graduated from LDS Business College, he studied electrical engineering through an international correspondence school course. He later received a PhD in electrical engineering from the University of Uppsala...

demonstrated a "radiant energy device" to many people who were unable to find a hidden power source. On June 9, 1925, Hermann Plauson

Hermann Plauson

Hermann Plauson was an Estonian engineer and inventor. Plauson investigated the production of energy and power via atmospheric electricity.-Biography:...

receives which utilizes atmospheric energy. In 1928, Lester Hendershot got an Army commandant to endorse his free energy machine called the "fuelless motor". At the close of the twenties, Edgar Cayce

Edgar Cayce

Edgar Cayce was an American psychic who allegedly had the ability to give answers to questions on subjects such as healing or Atlantis while in a hypnotic trance...

in Chicago, Illinois, described "Motors with no Fuel" (Reading 4665–1; March 8, 1928).

John Searl

John Searl

John Roy Robert Searl is the self-styled inventor of the Searle Effect Generator , a supposed open system electrical generator capable of extracting clean and sustainable electrical energy from the environment, based on "magnetic waveforms that generates a continual motion of magnetized rollers...

claims in 1946 to have invented an open system ambient energy converting device called the Searl Effect Generator (SEG), inspired by a series of recurring dreams.

1951 to 1980

During the middle of the 20th century, Viktor SchaubergerViktor Schauberger

Viktor Schauberger was an Austrian forester/forest warden, naturalist, philosopher, inventor and Biomimicry experimenter....

claimed to have discovered some special vortex energy in water. Since his death in 1958, people are still studying his works.

In 1966, Josef Papp

Josef Papp

Josef Papp was an engineer who was awarded U.S. patents related to the development of a fusion engine, and also claimed to have invented a jet submarine.-Alleged submarine journey:...

(sometimes referred to as Joseph Papp or Joseph Papf) supposedly developed an alternative car engine that used inert gases

Noble gas

The noble gases are a group of chemical elements with very similar properties: under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases, with very low chemical reactivity...

. He gained a few investors but when the engine was publicly demonstrated, an explosion killed one of the observers and injured two others. Mr. Papp blamed the accident on interference by physicist Richard Feynman

Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman was an American physicist known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics and the physics of the superfluidity of supercooled liquid helium, as well as in particle physics...

, who later shared his observations in an article in LASER, Journal of the Southern Californian Skeptics. Papp continued to accept money but never demonstrated another engine.

On December 20 of 1977, Emil T. Hartman received titled "Permanent magnet propulsion system". This device is related to the Simple Magnetic Overunity Toy

Simple Magnetic Overunity Toy

The Simple Magnetic Overunity Toy is 1985 invention by Greg Watson from Australia that claims to show "over-unity" energy — a route to purported perpetual motion.-Overview:...

(SMOT).

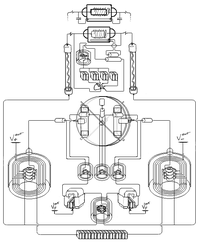

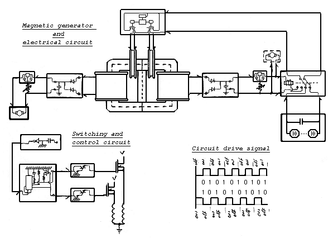

1960s

The 1960s was the decade that started on January 1, 1960, and ended on December 31, 1969. It was the seventh decade of the 20th century.The 1960s term also refers to an era more often called The Sixties, denoting the complex of inter-related cultural and political trends across the globe...

at a place called Methernitha

Methernitha

Methernitha refers to two related entities, both founded by Paul Baumann : Methernitha Christian Alliance and Methernitha Cooperative...

(near Berne

Berne

The city of Bern or Berne is the Bundesstadt of Switzerland, and, with a population of , the fourth most populous city in Switzerland. The Bern agglomeration, which includes 43 municipalities, has a population of 349,000. The metropolitan area had a population of 660,000 in 2000...

, Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

). The Testatika is an electromagnetic generator

Electrical generator

In electricity generation, an electric generator is a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy. A generator forces electric charge to flow through an external electrical circuit. It is analogous to a water pump, which causes water to flow...

based on the 1898 "Pidgeon electrostatic machine" which includes an inductance

Electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic induction is the production of an electric current across a conductor moving through a magnetic field. It underlies the operation of generators, transformers, induction motors, electric motors, synchronous motors, and solenoids....

circuit, a capacitance

Capacitance

In electromagnetism and electronics, capacitance is the ability of a capacitor to store energy in an electric field. Capacitance is also a measure of the amount of electric potential energy stored for a given electric potential. A common form of energy storage device is a parallel-plate capacitor...

circuit, and a thermionic rectification

Rectifier

A rectifier is an electrical device that converts alternating current , which periodically reverses direction, to direct current , which flows in only one direction. The process is known as rectification...

valve

Vacuum tube

In electronics, a vacuum tube, electron tube , or thermionic valve , reduced to simply "tube" or "valve" in everyday parlance, is a device that relies on the flow of electric current through a vacuum...

. Allegedly a perpetual motion machine, the Testatika resembles in some respects a Wimshurst machine

Wimshurst machine

The Wimshurst influence machine is an electrostatic generator, a machine for generating high voltages developed between 1880 and 1883 by British inventor James Wimshurst ....

.

Guido Franch reportedly had a process of transmuting

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

water atoms into high-octane

Octane

Octane is a hydrocarbon and an alkane with the chemical formula C8H18, and the condensed structural formula CH36CH3. Octane has many structural isomers that differ by the amount and location of branching in the carbon chain...

gasoline

Gasoline

Gasoline , or petrol , is a toxic, translucent, petroleum-derived liquid that is primarily used as a fuel in internal combustion engines. It consists mostly of organic compounds obtained by the fractional distillation of petroleum, enhanced with a variety of additives. Some gasolines also contain...

compounds (named Mota fuel) that would reduce the price of gasoline to 8 cents per gallon. This process involved a green powder

Powder (substance)

A powder is a dry,thick bulk solid composed of a large number of very fine particles that may flow freely when shaken or tilted. Powders are a special sub-class of granular materials, although the terms powder and granular are sometimes used to distinguish separate classes of material...

(this claim may be related to the similar ones of John Andrews (1917)). He was brought to court for fraud

Fraud

In criminal law, a fraud is an intentional deception made for personal gain or to damage another individual; the related adjective is fraudulent. The specific legal definition varies by legal jurisdiction. Fraud is a crime, and also a civil law violation...

in 1954 and acquitted

Acquittal

In the common law tradition, an acquittal formally certifies the accused is free from the charge of an offense, as far as the criminal law is concerned. This is so even where the prosecution is abandoned nolle prosequi...

, but in 1973 was convicted. Justice

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

William Bauer and Justice Philip Romiti both observed a demonstration in the 1954 case.

In 1958, Otis T. Carr

Otis T. Carr

Otis T. Carr first emerged into the 1950s flying saucer scene in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1955 when he founded OTC Enterprises, a company which was supposed to advance and apply technology originally suggested by Nikola Tesla...

from Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

formed a company to manufacture UFO

Unidentified flying object

A term originally coined by the military, an unidentified flying object is an unusual apparent anomaly in the sky that is not readily identifiable to the observer as any known object...

-styled spaceship

Spacecraft

A spacecraft or spaceship is a craft or machine designed for spaceflight. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, earth observation, meteorology, navigation, planetary exploration and transportation of humans and cargo....

s and hovercraft

Hovercraft

A hovercraft is a craft capable of traveling over surfaces while supported by a cushion of slow moving, high-pressure air which is ejected against the surface below and contained within a "skirt." Although supported by air, a hovercraft is not considered an aircraft.Hovercraft are used throughout...

. Carr sold stock

Stock

The capital stock of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders. It serves as a security for the creditors of a business since it cannot be withdrawn to the detriment of the creditors...

for this commercial

Commerce

While business refers to the value-creating activities of an organization for profit, commerce means the whole system of an economy that constitutes an environment for business. The system includes legal, economic, political, social, cultural, and technological systems that are in operation in any...

endeavor. He also promoted free energy

Second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is an expression of the tendency that over time, differences in temperature, pressure, and chemical potential equilibrate in an isolated physical system. From the state of thermodynamic equilibrium, the law deduced the principle of the increase of entropy and...

machine

Machine

A machine manages power to accomplish a task, examples include, a mechanical system, a computing system, an electronic system, and a molecular machine. In common usage, the meaning is that of a device having parts that perform or assist in performing any type of work...

s. He claimed inspiration from Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla was a Serbian-American inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer...

, among others.

In 1962, physicist Richard Feynman

Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman was an American physicist known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics and the physics of the superfluidity of supercooled liquid helium, as well as in particle physics...

discussed a Brownian ratchet

Brownian ratchet

In the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics, the Brownian ratchet, or Feynman-Smoluchowski ratchet is a thought experiment about an apparent perpetual motion machine first analysed in 1912 by Polish physicist Marian Smoluchowski and popularised by American Nobel laureate physicist Richard...

that would supposedly extract meaningful work from Brownian motion

Brownian motion

Brownian motion or pedesis is the presumably random drifting of particles suspended in a fluid or the mathematical model used to describe such random movements, which is often called a particle theory.The mathematical model of Brownian motion has several real-world applications...

, though he went on to demonstrate how such a device would fail to work in practice.

In the 1970s David Hamel produced the Hamel generator, an "antigravity" device, supposedly after an alien abduction. The device was tested on MythBusters

MythBusters

MythBusters is a science entertainment TV program created and produced by Beyond Television Productions for the Discovery Channel. The series is screened by numerous international broadcasters, including Discovery Channel Australia, Discovery Channel Latin America, Discovery Channel Canada, Quest...

where it failed to demonstrate any lift-generating capability.

Howard Robert Johnson developed a permanent magnet motor and, on April 24, 1979, received .[The United States Patent office main classification of his 4151431 patent is as a "electrical generator or motor structure, dynamoelectric, linear" (310/12).] Johnson said that his device generates motion, either rotary or linear, from nothing but permanent magnets in rotor as well as stator, acting against each other. He estimated that permanent magnets made of proper hard materials should lose less than two percent of their magnetization in powering a device for 18 years.

1981 to 1999

John BediniJohn Bedini

John Bedini of the Bedini Electronics company is an electrical engineer. He created B.A.S.E., an audio signal processor; and he has filed patents for a number of audio technologies...

claimed development of several free energy devices. Bedini has, reportedly, refused to allow independent investigation.

Dr. Yuri S. Potapov of Moldova

Moldova

Moldova , officially the Republic of Moldova is a landlocked state in Eastern Europe, located between Romania to the West and Ukraine to the North, East and South. It declared itself an independent state with the same boundaries as the preceding Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1991, as part...

, claims development of an over-unity electrothermal water-based generator (referred to as "Yusmar 1"). He founded the YUSMAR company to promote his device. The device has failed to work under tests.

CETI claimed development of a device

CETI Patterson Power Cell

The CETI Patterson Power Cell is an electrolysis device invented by retired chemist James A. Patterson, which he said created more energy than it used. Promoted by Clean Energy Technologies, Inc...

that outputs small yet anomalous amounts of heat, perhaps due to cold fusion

Cold fusion

Cold fusion, also called low-energy nuclear reaction , refers to the hypothesis that nuclear fusion might explain the results of a group of experiments conducted at ordinary temperatures . Both the experimental results and the hypothesis are disputed...

. Skeptics state that inaccurate measurements of friction

Friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and/or material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:...

effects from the cooling flow through the pellets may be responsible for the results.

In 1999, Sanjay Amin of Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Mahoning County; it also extends into Trumbull County. The municipality is situated on the Mahoning River, approximately southeast of Cleveland and northwest of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania...

, established Entropy Systems Inc. (ESI). The company received a 3.5 million dollar investment for a device that is claimed to violate the second law of thermodynamics

Second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is an expression of the tendency that over time, differences in temperature, pressure, and chemical potential equilibrate in an isolated physical system. From the state of thermodynamic equilibrium, the law deduced the principle of the increase of entropy and...

, producing power by absorbing heat from atmospheric

Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is a layer of gases surrounding the planet Earth that is retained by Earth's gravity. The atmosphere protects life on Earth by absorbing ultraviolet solar radiation, warming the surface through heat retention , and reducing temperature extremes between day and night...

air (and that external reservoir can be at any temperature

Temperature

Temperature is a physical property of matter that quantitatively expresses the common notions of hot and cold. Objects of low temperature are cold, while various degrees of higher temperatures are referred to as warm or hot...

, even sub-zero). The technology

Technology

Technology is the making, usage, and knowledge of tools, machines, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or perform a specific function. It can also refer to the collection of such tools, machinery, and procedures. The word technology comes ;...

had been patent

Patent

A patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

ed in the United States, Europe, and Australia. The claims have subsequently been shown to be false and no product was ever released.

2000s

In 2002, the GWE (Genesis World Energy) group claimed to have 400 people developing a device that supposedly separated water into H2 and O2 using less energy than conventionally thought possible. No independent confirmation was ever made of their claims, and in 2006, company founder Patrick Kelly was sentenced to five years in prison for stealing funds from investors.

In 2006, Steorn

Steorn

Steorn Ltd is a small, private technology development company in Dublin, Ireland. It announced in August 2006 it had developed a technology which provides "free, clean, and constant energy" in violation of the law of conservation of energy, a fundamental principle of physics.Steorn challenged the...

Ltd. claimed to have built an over-unity device based on rotating magnets, and took out an advertisement soliciting scientists to test their claims. The selection process for twelve began in September 2006 and concluded in December 2006. The selected jury started investigating Steorn's claims. A public demonstration scheduled for July 4, 2007 was canceled due to "technical difficulties." In June 2009, the selected jury said the technology does not work.

Further reading

- Childress, D. H. (1994). The free-energy device handbook: A compilation of patents & reports. Stelle, Ill: Adventures Unlimited Press.

- Dircks, H. (1968). Perpetuum mobile: Or, A history of the search for self-motive power, from the 13th to the 19th century. With an introductory essay. Amsterdam: B.M. Israël

- Verance, P., & Dircks, H. (1916). Perpetual motion: Comprising a history of the efforts to attain self-motive mechanism, with a classified, illustrated, collection and explanation of the devices whereby it has been sought and why they failed, and comprising also a revision and re-arrangement of the information afforded by "Search for self-motive power during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries," London, 1861, and "A history of the search for self-motive power from the 13th to the 19th century," London, 1870, by Henry Dircks. Chicago: Printed by Rogers & Hall co.

General sources

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. (1977). Perpetual Motion: The History of an Obsession. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-60131-X.

- Angrist, Stanley W., "Perpetual Motion Machines". Scientific American. January, 1968.

- Hans-Peter, "Perpetual Motion Chronology". HP's Perpetuum Mobile.

- MacMillan, David M., et al., "The Rolling Ball Web, An Online Compendium of Rolling Ball Sculptures, Clocks, Etc".

- Lienhard, John H., "Perpetual motion". The Engines of Our Ingenuity, 1997.

- "Patents for Unworkable Devices". The Museum of Unworkable Devices.

- "Perpetual Motion Pioneers (The Movers and Shakers)". The Museum of Unworkable Devices.

- Boes, Alex, "Museum of Hoaxes".

- Kilty, Kevin T., "Perpetual Motion". 1999.

- The Basement Mechanic's Guide to Testing Perpetual Motion Machines

- 1911 Encyclopedia, "perpetual motion". LoveToKnow, Corp.

External links

- Allan, Sterling D., "Free Energy Inventors". December 11, 2003.

- Gousseva, Maria, "Alleged Creation of Perpetual Energy Source Splits Scientific Community". Pravda.ru.

- Bearden, Tom, "Perpetual motion vs. "working machines creating energy from nothing"". 2003, Revised 2004.

- Perpetuum mobile page by Veljko Milković.

- Bessler's Wheel